Archive for July 2020

One thousand entries and still hanging on

Venice International Film Festival screening 2017 of Rosita, in the Sala Darsena. Pre-coronovirus, no social distancing.

Both of us here:

Kristin:

This, our 1000th entry in this blog, comes at a strange point in our lives, and everyone else’s. Films, all facets of which are our main subject, are nearly gone from the big screens upon which we prefer to view them. Normally at this time we would be anticipating another trip to the Venice International Film Festival, which shows films in venues with very big screens and superb sound systems. Now we’re streaming and watching discs on a medium-size TV.

Back when our first entry appeared, on September 26, 2006, we weren’t thinking about whether we would ever get this far. We didn’t really know what the blog would contain. We hadn’t even come up on our own with the idea of starting it. One of the users of our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction, suggested it.

Back in those days, textbooks were simple things. They were physical, without digital iterations. They might have a handful of online resources, and perhaps teachers could assemble their own custom text from parts of the book. As each revision rolled around, McGraw-Hill invited around a dozen users of the book to fill out a detailed questionnaire, picking out its most useful parts and making suggestions for changes.

We occasionally found these comments helpful, but most of them involved adding more material. We weren’t allowed any additional pages for new editions, so those suggestions, often reasonable, had to be ignored.

I remember vividly, however, one unique comment that ran something like this: “Why don’t the authors start a blog?” (The questionnaires were anonymous, but if you recognize yourself as the culprit, let us know and we’ll all share a virtual laugh.)

Naïve souls as we were, we thought this suggestion might be a good idea. We could provide little essays that complemented the textbook, expanding it, as it were, without extra pages. Of course, it would also publicize Film Art and its companion, Film History: An Introduction.

Starting the blog was relatively easy. David had already created a website (thanks to Jonathan Frome and Vera Crowell) that could host it. Later our long-time web tsarina Meg Hamel set up the blog, to which we could add posts and photos ourselves.

Widened horizons

In the first brief entry, of 26 September 2006, David wrote about Christine Vachon’s recently released book, A Killer Life: How an Independent Film Producer Survives Deals and Disasters in Hollywood and Beyond. The idea was that Vachon touched upon aspects of film form and style that were relevant to ideas we discussed in Chapters 1 t0 3 of our textbook. Soon, though, we departed from the idea of tailoring our content strictly to Film Art.

The next two entries (here and here), again by David, reported from the Vancouver International Film Festival. The timing was purely coincidental. Tony Rayns had invited him to be a judge for the Dragons and Tigers competition for young Asian filmmakers, and it was his first visit. So he was officially there as a guest, not a blogger, but those two entries were already more substantial than the opening one. And of course he was happy to see two old Madison friends, film programmer Alissa Simon and filmmaker, and former DB teaching assistant, James (Jim) Benning.

He followed those immediately with two reports (here and here) from the American Society for Aesthetics conference, which happened to take place in Milwaukee that year. And I followed that by tearing apart disagreeing with an article in the Wall Street Journal. Its author predicted the end of logical Hollywood plotting because one interactive movie had been released. Its title, “The end of cinema as we know it–yet again,” could have been used for quite a few pieces we have written over the years. These early entries, modest though they were, set a pattern for some of the motifs that have run through the blog ever since (at least, until the present crisis).

In short, we branched out in any direction that events or our fancies took us. David even did some non-film pieces, mostly about related arts and about current politics.

Some of our entries could be of use to teachers and students. Each year in advance of the start of the school year, I post an entry called “Is there a blog in this class?” (This year’s is coming up soon.) There I suggest, chapter by chapter, which entries are relevant to each. We also started putting call-outs to selected entries in the textbooks themselves. In the e-editions these are live links. We hope these are of use to the people who were the original putative targets of the blog.

After sixteen years, we have noticed how the blog has changed us as scholars and cinephiles. Mostly this has been for the better.

For one thing, publishing outside academic, peer-reviewed contexts has given us the freedom to write in a bit less formal prose. I had already adopted this approach for The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood, in which I tried to balance research with a more casual style that could appeal to fans of Peter Jackson’s adaptation. (That book had recently gone to into press when we started the blog.) David’s two most recent books and the one he is working on now reflect this change, and that has been commented on–mostly favorably.

Perhaps more importantly, the blog made us more visible in film circles outside of academia. After all, blogs are part of social media, albeit by now a rather old-fashioned element in that vast internet swirl. By flinging our stuff out into the ether, we had unwittingly ventured into journalism of a sort. We found ourselves able to get press accreditation to actual events out in the real world.

David’s visit to Vancouver in 2006 was not as a blogger, but over the years that followed, we remained welcome guests in part because we reported regularly on the films we saw. In advance of David’s retirement from university teaching in 2004, we had envisioned ourselves, among other things, having more time to attend festivals. This turned out to be feasible, as we added reports on Hong Kong (which David had already started attending), Il Cinema Ritrovato (Bologna), Cinédécouvertes (Brussels, sadly no longer held), Ebertfest, Palm Springs, Torino, and for the past three years, Venice, as well as our own Wisconsin Film Festival. On the right, you see Med Hondo, who visited Bologna in 2017.

The blog also led us in a modest way into the world of streaming. We have long had a friendly relationship with the dedicated team at The Criterion Collection. We’ve done supplements for them and with their cooperation used clips from their classic films in online educational materials for our textbooks. (The folks there view us as educating their future customers, and we hope that has been the case.) Whether they would have asked us and our collaborator Jeff Smith to contribute a series of video essays on the films streaming on The Criterion Channel is unclear, but we, and possibly they, thought of such a series as a sort of extension to the blog. Indeed, we gave it the same name, “Observations on Film Art.”

Entries in that series are more elaborate than blog entries, of course, and we feel it is something of an accomplishment to have reached thirty-seven to date, with more unedited material already “in the can.” It is a privilege to be involved, even in a small way, with what has quickly become the leading art-house/indie/classic film streaming service, and we suspect we owe that in part to the blog.

Film history passing before our eyes

Werner Herzog, Roger Ebert, and Paul Cox at Ebertfest 2007.

Our regular attendance at the festivals has been a huge boon in allowing us to keep up with many of the year’s new films on the big screen rather that waiting for the home-video release or, more recently, streaming availability. Lately we have been revising Film History for its fifth edition, and I found myself going back to our festival reports for succinct descriptions of films we considered important enough to figure in our updates of the late chapters.

Festivals also provide a delightful way to follow the careers of young filmmakers without realizing until later that one was doing so. For example, on July 15 the Venice festival announced that the head of the jury for the Giornate degli Autori program for promising filmmakers would be Israeli director Navad Lapid, whose Synonymes (2019) won the Golden Bear at Berlin last year. I wrote about it when we saw it at the Torino festival in November. The press release mentioned that Lapid had previously directed two other features, as well as many shorts. I had seen both of the features at Vancouver and blogged about them: Policeman (2011) and The Kindergarten Teacher (2014). So I had seen all of Lapid’s feature films without planning it that way. It is impressive to see the leap in complexity with Synonymes after two good films that I might never have seen had I not regularly visited that and other festivals.

Similarly, our long relationship with Ebertfest has given us a chance to meet both established and upcoming film artists. Thanks to Roger’s support, and the continuing efforts of Chaz Ebert and Nate Kohn, that remarkable event in Champaign-Urbana has become central to US film culture. Through Ebertfest we forged tight friendships with Jim Emerson, Matt Zoller Seitz, and other people working to broaden audiences and deepen appreciation of life-changing movies.

Apart from attending film festivals, getting press accreditation has benefited me in another situation. As part of my involvement in researching the Jackson Lord of the Rings films, I participated in a panel put on by TheOneRing.net at Comic-Con 2008. (I blogged about that banquet of popular culture here, here, and here.) Years later, I wanted to attend Comic-Con 2014 to witness the last of the big Hall H promotional events for a Jackson Tolkien adaptation, the third film of the Hobbit series. That time I wasn’t a guest, but I applied for a press pass based on being a blogger and got one.

I haven’t gone back, and I think my accreditation has lapsed, but as long as we keep the blog going, I probably have the option.

For us personally, the blog has played a role that a plain old-fashioned log of events would. (It’s worth remembering that “blog” comes from “weblog.”) We haven’t keep lists of the films we see, but sometimes I wish I had. Going back through the blog, though, is a great way of waxing nostalgic over the wonderful travels we have enjoyed and the friends in so many parts of the world that we have visited and shared meals with in happier circumstances–opportunities which we hope will come again.

We are reminded of films we saw, as well. Every now and then we have occasion to look back over older entries, seeking to create a link in a new blog. We often run across entries we don’t recall writing and titles we don’t remember seeing until the blog posts jog our memories. After a certain point we vowed to include illustrations in every entry, and that makes these visits to our past all the more vivid and enjoyable.

DB here:

I second everything KT has said. And more! See below.

Expanding the conversation and rapid response

Bologna, Piazza Maggiore screening of A Hard Day’s Night, 2014: Richard Koszarski, Diane Koszarski, and Lee Tsiantis.

Living online has given my retirement years a new dimension–of thinking, of access to art and ideas and new friends. I sometimes say that our blog is Internet 1.5–a publishing platform without the bombardment of instant comments. We’d get more traffic if we allowed comments, but (a) so many comments columns are insults to the human spirit and (b) we don’t want to spend time monitoring them. (But you can send an email.) The result is something like a more-or-less weekly magazine column, except that we can say what we want, write as long as we want, and include stills and clips. And there’s no editor saying we can’t use “diegetic.”

From another angle, the blog has been a substitute for my teaching. It allows me to develop ideas in ways that are informal, less precisely chiseled than they would be in a book or article. Call it “para-academic,” or “informal scholarship.” The blog has also let me send out communiqués about research findings around movies I was studying in Brussels (say, here or here) or at the Library of Congress (here and here). And, as Kristin mentioned I think the blog has encouraged me to write more conversationally than an academic publication would.

Retirement has encouraged me to think through recent events in film culture more fully than I could when I was teaching, and so some blog entries have become more topical. The big example is my decision to write about the digital conversion of exhibition back in 2011. I thought that somebody could record things as they were happening on the ground, and I tried to do that in a series of entries. One looked at how a small theatre in Harmony, Minnesota, confronted the crisis.

That series in turn became a little digital book that has generated a surprising amount of interest and remains, I think, a useful thumbnail history of a transitional period. From another angle, our interest in Christopher Nolan’s films allowed us to write about them as they came out, and then to revisit them in a broader perspective in another digital book, now in its second edition. It ruffled some feathers, leading me to speculations about blunt-force cinephilia. As ever, the blog proved a good forum for developing further ideas.

Speaking of new editions, having a web presence has enabled us to make available out-of-print versions of our work. Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment was put up on the main website in its original 1985 form, but I revamped both Planet Hong Kong and On the History of Film Style for digital editions when my publisher put them out of print. For both, I was able to use blog entries (here and here) to introduce them to a wider range of readers than would probably learn of them otherwise. It’s been gratifying to see both used as textbooks in courses as well.

Go back to the “para-academic” idea. I’ve been surprised to see that while academics have been supportive of our online efforts, they seem still to treat them as secondary to our print publications. By contrast, I’ve learned that there are a great many people who love films but who have found a lot of academic talk about cinema intimidating, dense, or dull. Some of these cinephiles are interested in ideas, if those ideas are presented in concrete and vivid ways. Our blog entries try to bring our notions about film form and style, about film history and film experience, to those readers.

An example is my never-ending crusade against reflectionist interpretation, the idea that a movie coming out today (well, maybe no movie is coming out tomorrow) reflects the Zeitgeist or national character or current events in a straightforward way. I won’t bore you with my arguments against this idea (see here and here and here), but without a blog I don’t think I’d be able to ride this hobby horse so intently. Thanks to the rapid-response capability of blogging, I can draw on current releases from The Dark Knight to The Hunt. I don’t know if I’ve convinced anybody that we can talk about film and culture more subtly if we take into account form, style, and genre. But the opportunity to use recent releases as AV demos has helped me refine my case.

This isn’t “popularizing” our research, I think. It’s an effort to see how research can stimulate people. Many readers, I think, know us only through the blog, and that’s fine. I like reader-friendly texts. I like to read in art history, cognitive psychology, music history, philosophy, and the like, but I’m not equipped to grasp the most technical literature in those fields. I need the “outreach” publications of Gombrich, Barzun, Baxandall, Sontag, Pinker, Taruskin, Hogan, Alex Ross, Mary Beard, Noël Carroll, and the many more academics and intellectuals who are not only researchers but, in the strongest sense, writers.

People

Hong Kong International Film Festival 2011: Joanna Lee, Michael Campi, and Ken Smith.

The blog has given us a chance to call attention to institutions we think deserve wider recognition. Those include the Arthouse Convergence, the Danish Film Institute and its archive, the Konrad Wolf Film School at Babelsberg, the Fox archive, the AMPAS archive, the Munich Film Archive, the Austrian Film Archive, George Eastman House (and its magnificent Nitrate Fest), and of course our stalwart rock through the years, the Royal Film Archive of Belgium (now called Cinematek). There’s our own Cinematheque too, as well as little theatres we come across in our travels (here and there). We even find a “lost” film on home turf. There’s the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp, which has proven endlessly stimulating to my thinking (and viewing). And of course there’s the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image; we try to cover its annual get-together.

We also like supporting hard-working distributors like Milestone (and here), Flicker Alley, Editions Filmmuseum, and again of course Criterion, who devote great energy to opening up unknown byways of cinema. The Criterion team–Peter Becker, Kim Hendricksen, Grant Delin, Curtis Tsui, Elizabeth Pauker, Abbey Lustgarten, Susan Arosteguy, and many others–have made our lives continually exhilarating.

The blog has brought us closer to film artists too. At Ebertfest Kristin interviewed Nina Paley, and I got to talk to Doc Erickson about his long career working at Paramount and with Hitchcock. We’ve done a couple of interviews with director/screenwriter David Koepp (here and here), and Kristin questioned archival honchos Mike Pogorzelski and Schawn Belston about the prospect for a celestial multiplex–which even streaming is unlikely to deliver. We got to meet Bill Forsyth, Terence Davies, James Mangold, and Damien Chazelle, and because we try to understand the creative choices filmmakers face, we got to ask them about their craft.

As for critics–well, there are too many to mention here. Online and at festivals, we’ve come closer to a great many smart, dedicated critics and reviewers I have to mention at least Manohla Dargis, Kent Jones, Dave Kehr (now a sterling archivist), Justin Chang, Chuck Stephens, Bérénice Reynaud, and the Venice College team (Glenn Kenny, Stephanie Zacharek, Mick LaSalle, Michael Phillips, Chris Vognar, Ty Burr, all under the avuncular guidance of Peter Cowie).

The rapid-response advantage has also given us the opportunity to celebrate colleagues, particularly when they’ve written books we think cinephiles would enjoy. Then there are the colleagues we mourn. In the last year, the deaths have come quickly. I haven’t fully come to terms with the loss of Peter Wollen, Paul Spehr, Thomas Elsaesser, and Sally Banes. But we have acknowledged the importance of others who touched our lives, from Andrew Sarris and Edward Yang to Richard Corliss and Edward Branigan and of course Donald Richie and Roger Ebert. Necrology, the blog has taught me, is a heavy obligation.

On a less somber chord, the blog has given us the happy chance to host many excellent guest bloggers. We tapped them because their research is first-rate, and they widen out our explorations of film art within film history. So feel free to visit the contributions of:

Matthew Bernstein on Preston Sturges’ cleverness.

Kelley Conway on three women of Cannes, on French Films at Vancouver, and on La La Land.

Leslie Midkiff DeBauche on silent-era fangirls.

Eric Dienstfrey on recording and mixing in La La Land.

Rory Kelly on the character arc in Hollywood screenwriting.

Charles Maland on James Agee.

Nicola Mazzanti on silent frame rates.

Amanda McQueen on La La Land as a modern musical.

Tim Smith on eye-scanning and watching There Will Be Blood.

Malcolm Turvey on mirror neurons.

Jim Udden on visiting the set of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin and the film that resulted.

David Vanden Bossche on 3D in Europe.

And of course the many guest entries by our collaborator on our Criterion Channel series Jeff Smith, who has written about Foreign Correspondent, Trumbo, The Player, The Devil and Daniel Webster, the Atmos sound system, Memories of Underdevelopment, Three Colors: Red, Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (here and here), True Stories, Breaking the Waves, and Oscar song nominations (here and here and here and here). Watch for Jeff’s upcoming entry on Ennio Morricone.

Back in 2011, we put together a collection of blog entries as a book: Minding Movies: Observations on the Art, Craft, and Business of Filmmaking (University of Chicago Press). It consisted of 31 entries, grouped in rough thematic sections. This leads us to muse on how many books one thousand entries equates to. That’s roughly 32, though far from all of our entries are worth anthologizing. (The entire blog, however, is being archived by the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research here on campus.) Could we have used our time better in writing actual books? We think not. There is a pleasure in writing on minor subjects occasionally and in getting our thoughts to the reading public immediately. Books, after all, require more research than we put into most of our entries, and there is the editorial and publishing process to go through. And we are past the points in our career where we need to expand our CVs.

In short, although we occasionally feel uninspired, especially in these days of no travel, limited socializing, and practically no theatrical film exhibition, we are glad that we started the blog nearly fourteen years ago. Once those activities resume, we’ll have the places we go, the friends we pal around with, and the movies we see to write about. We seriously doubt that we will ever make it to 2000 entries, but who knows?

Venice International Film Festival, 2019. Photo by Gerwin Tamsma.

Little stabs at happiness 4: Hitmen, with a side of sukiyaki

A Hero Never Dies (1998).

DB here:

Again, with apologies to Ken Jacobs, I offer another clip that pleases me in this long, hot summer. For earlier installments, go here, here, and here.

Johnnie To Kei-fung has been one of the leading Hong Kong directors since the 1990s. The first edition of my Planet Hong Kong (2000) wasn’t able to incorporate many mentions of his work, but that failing was remedied in my second edition, where he got several pages. Kristin and I first met him in fall of 2001, when Yuin Shan Ding arranged for us to visit the set of Running Out of Time 2. That was a memorable night, with the bike race shot in an elaborate false street wreathed in noirish city vapor.

We spent down time with the stars Ekin Cheng Yee-kin and Lau Ching-wan. It was the beginning of a long friendship with Shan, Mr. and Mrs. To, and the Milkway team.

Well before this, though, I had been teaching Mr. To’s films in my courses, and I much enjoyed showing–on 35mm, no less–A Hero Never Dies (1998). This flamboyant film, about two rival hitmen who unite against the gang bosses who have betrayed them, is a sort of post-John-Woo meditation on the costs of loyalty.

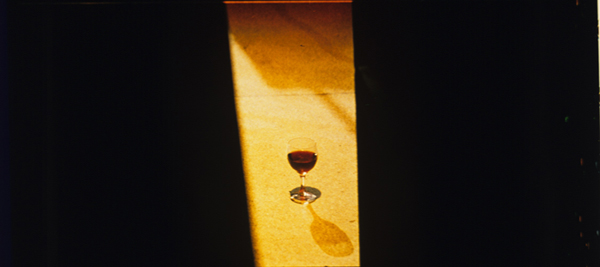

One sequence that usually got the students going was the men’s first up-close confrontation in a bar. Having struck out at each other long-distance, they rendezvous for a face-off–not over guns but over glasses of wine. The clip lacks subtitles, so I should explain that each man instructs the bartender to pour for the other one. Then, after Lau deploys his portion tactically, he refers to Lai’s wrecking his apartment: “This is for destroying my home.” There follows a tabletop action scene.

Shot and cut with great precision, timed to an infectious tune, it’s a model of mock-heroic filmmaking. Its brashness suits its swaggering protagonists, but it has a playground absurdity that evokes Leone. (Think of the hat-blasting gun duel in For a Few Dollars More.) The comedy is enhanced by Lau’s reaction shots and, as Kristin likes to point out, the heaviest coin in Hong Kong. One student told me: “When you’ve got a sequence like this, you’ve got a great national cinema.”

The result yields a pure kinetic pleasure, due partly to the coiling camera movements and the echoing rhythm of the cuts and gestures (ducking out of frame/rising into frame, finger flips/snorting smoke). Mr. To kindly took me through the sequence in an interview, and I learned that it was all shot in one night, after the bar had closed. It wasn’t storyboarded, but by this point Mr. To had all his shots and cuts in his head, and he and the actors developed the sequence as they filmed it.

It takes real pictorial intelligence, I think, to glide between concreteness and abstraction, onscreen and offscreen space, and each man’s optical viewpoint so suavely and zestfully. The camera plays peekaboo with the action.

As for the performances, Mr. To explained that Lau Ching-wan is such an extroverted actor that Leon Lai-ming could counter that bravado best by impassivity, returning his look at key moments. It’s an echo of what Howard Hawks told Montgomery Clift in facing off against John Wayne in Red River. Eventually it all settles into a calm, integrating long shot that declares a truce. What a pleasure to see a scene that actually buttons itself up visually.

And the song? Mr. To told me that the pop version of “Sukiyaki” (on the ambient soundtrack of my own teen years) was often played in theatres as pre-show music. “It always reminds me of movies.”

Thanks to Shan, Mr. and Mrs. To, To Kei-chi, and many other members of the Milkyway team. And to Li Cheuk-to, Athena Tsui, Jacob Wong, Sam Ho, and all the other HKIFF allies over the years. And continued hope for a strong Hong Kong!

We have many blog entries on Johnnie To and Milkyway.

Upper row, left to right: Lau Ching-wan, Yau Na-hoi, Johnnie To Kei-fung; bottom row, Ekin Cheng Yee-kin, DB, KT. Hong Kong, November 2001. Photo: Yuin shan Ding.

The Shock Troops: Never Trumpers and right-wing agitprop

DB here:

To my usual morning news mix, I’ve lately added Twitter feeds. I don’t like Twitter and don’t participate myself, but I enjoy checking the streams issuing from Never Trumpers, particularly those allied with the Lincoln Project. Should I join Twitter? Nah. That would take away the small pleasure of typing into Google: Rick Wilson twit, George Conway twit, David Frum twit…

These streams have many virtues. For one thing, they often tip me to scandalous stories before the august papers have caught on. For another, the Never Trumpers attract the sort of disrespectful exchanges that represent the spontaneous genius of the American people. Viz:

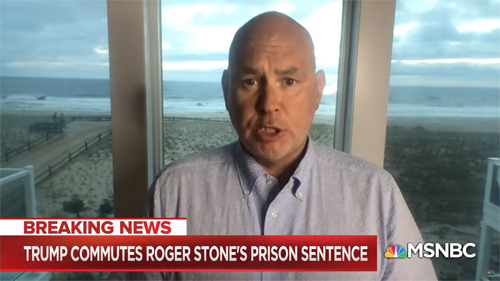

Just as attractive to me is the cast of characters. Rick Wilson, striving to become the Dr. Hunter S. Thompson of the 2010s, can write good polemic. His most scabrous stuff is reserved for his Daily Beast column but can be glimpsed in tweet-size doses and heard on the New Abnormal podcast (liberally salted with the f-word, so you know he’s damn sincere). George Conway, mysteriously still cohabiting with the Kraken Queen of the Trump regime, strives for a modicum of dignity. He pursued, with a fervor that he never lets you forget, the startling thesis that Trump is deeply nuts. Steve Schmidt, he of the orotund tones and rolling parallel syntax, wants to come off as a Roman senator daring the barbarians to fling a spear his way.

They all like dogs.

David Frum, who accurately predicted the Trump coronavirus policy (“Take the punch”), has written A Very Serious Book and when not pushing his latest podcast appearance, offers free autographed bookplates. The very conceit that people want books, let alone want sticky paper to paste in them, carries a certain charm. But then Frum comes from Canada.

Wisconsin’s Rush Limbaugh Charlie Sykes, waking up to realize that his listeners were just waiting for him to go full Trump, has left our verdant COVID landscape to run The Bulwark, the newest outpost of desperate neocon hopes. Jennifer Rubin has been a traveler on the anti-Trump train ever since Mitt (Quiet Rooms) Romney fizzled out. Her current WaPo columns make her sound like a 60s protest marcher. A “small-l liberal party” must

defend democratic institutions, address yawning gaps in wealth and opportunity, integrate into a global economy, tackle systemic problems such as climate change and racism, root out corruption and cronyism, and exercise leadership in a world in which illiberal regimes are increasingly aggressive and confident.

No mention of women, LBGQT, or global warming, but give her time. Those columns don’t write themselves. Actually, come to think of it, they do.

Another WaPo fixture, fedora-wearing Max Boot, has seen the light too, and of course produced a book about it. Bringing up the rear is the smirking, reliably ineffectual William Kristol, whose latest hand-wringing column ponders whether the Republican Party should be crushed to powder. Result: Maybe? Maybe not! Who knows?

Many of these Never Trumpers have gained media purchase through the green rooms (now green screens) of CNN and MSNBC. In this last venue, perpetually pert Nicolle Wallace, former fixture of the Bush White House and now surrogate for COVID Moms, blasts fire at the GOP.

Those of us who think that the biggest threats to civilization are guns, religion, and Republicans might believe that we have true allies in this swaggering brigade of old GOP buccaneers. Seeing them Zooming in from luxurious quarters (check Schmidt’s ocean view) paid for in the blood of losing Democratic candidates might be unsettling, but perhaps they deserve the benefit of the doubt. Have they not put their very particular set of skills to the task of unseating Trump? Haven’t they reconciled themselves to installing Biden? Have not some committed their energies to wiping the current version of the Republican Party from the public sphere altogether?

Non-Soviet montage

When not writing columns and filling podcast hours, some are becoming media renegades, launching guerrilla raids through video broadsides. They have joined progressive groups like VoteVets in assailing Trump’s failure. Here the Lincoln Project is the leader, although it’s joined by initiatives from less self-publicizing cadres: Republican Voters Against Trump, The Meidas Touch, and other groups.

I suspect that what has rallied Never Trumpers to Black Lives Matter and the turmoil in the streets are the waves of irrefutable evidence of systematic police brutality. Spinmeisters trying to be public intellectuals, they are supersensitive to the power of images and sounds. They have created viral ads for decades, and now history is giving them a mountain of material to play with. Even if they’re genuinely revulsed by what their former party has done to our society, there’s the itch of tradecraft: time to try out new blades for shiv-in-the-ribs politics.

What’s fascinating to me as a film researcher is how those efforts exploit the conventions of left-wing agitprop from the silent era onward. True, sometimes they resort to classic documentary techniques, such as the hammering voice-over that instructs you what to think. Here’s one of the most spine-tingling, a Lincoln Project spot going after Trump’s legislative bootlickers.

And here’s the Lincoln Project’s “Mourning in America.”

At the visual level, the slamming cuts and pounding titles recall Soviet Montage techniques. Thanks to these devices, often there’s no need for voice-over at all. The image/ sound juxtapositions do the work, in the manner displayed in Emile de Antonio’s In the Year of the Pig. An instance is the way the Meidas Touch wields the First Daughter’s voice-over against her.

Sometimes just parallel editing does the trick. In Kino-Eye (1924), Dziga Vertov juxtaposed a sequence showing mental patients with one showing petty criminals working outside the interests of the state. The same tactic of side-by-side comparison can be repurposed for Internet skirmishes.

Nice to see people who hate Leninism using dialectical montage.

I’d be lying if I didn’t say I enjoy this spray of media shrapnel. Democrats have not understood the nature of the threat posed by Republicans, going way back. The 1964 “daisy ad” was the last time I remember them playing hardball. (Was Hillary, then a Goldwater Girl, traumatized by it?) Michelle Obama said, “When they go low, we go high.” The Never Trumper agitki reply: When they go low, we press their cheek into the pavement, jam our knee on their throat, and glare at the camera, as if to say, “You’re next.”

But let’s remember some things. The Never Trumpers were loyal Republicans through the years of Agnew, Haldeman, Erlichman, Mitchell, Atwater, Luntz, Rove, Ailes, Buchanan, Gingrich, the two Bushes, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Boehner, Graham, the “Young Guns,” the Tea Party, and early McConnell. They ceaselessly upbraided Obama for golfing and wearing a tan suit, while introducing the public to a word seldom used before.

Wilson worked on the detestable campaign against Max Cleland. While writing hilariously mistaken columns for the Times, Kristol was key in giving us Sarah Palin, the proto-Trump. Another Palin fan, Steve Schmidt was a close ally of Cheney’s and helped install Alito and Roberts on the Supreme Court. Frum’s stint in the Bush White House included vigorous commitment to the Iraq war.

Conway, a Federalist Society stalwart, lived in Trump Tower and with Ann Coulter scrutinized Bill Clinton’s groin anatomy. Choking up in the forthcoming A Duty to Warn documentary Unfit, he says that only recently did he realize that Trump is a racist. Cheerleading Republicans from the ramparts of WaPo in 2015, Jennifer Rubin suspended her support for Mitt (Binders Full of Women) Romney long enough to praise Wisconsin’s own Scott Walker as presidential timber:

Whether he’s successful or not, the potential addition of Walker to the race is a plus for the GOP and a sign that the party has a new generation of stars ready for the national stage.

True, Max Boot was among the first to use the F-word (no, not that one) in describing candidate Trump.

Trump is a fascist. And that’s not a term I use loosely or often. But he’s earned it.

Yet this assessment didn’t stop Boot from hoping that Trump would correct the Middle East errors of the Obama years. Praising Trump’s choice of “the thoughtful new secretary of defense, General Jim Mattis”–now long gone–Boot has his fingers crossed:

Let’s hope that the Trump team carefully studies—and with an open mind—what went wrong under Obama.

It’s those open-minded fascists we need.

Coming off the bench

©Steve Sack, at The Week (2017).

A large part of what irks the Never Trumpers is the career criminal’s bodacious bad manners, what the base loves and what the more discreet call his “character.” Run the tape of history backward, though, and delete Trump. If we had President Kasich or President Rubio or President Haley or even President Cruz, we would have the same rollback of regulations, the same planting of incompetent judges, the same tax windfalls for the wealthiest, the same efforts to wipe out DACA and Obamacare, and the same rise in inequality. How many Never Trumpers would object? Trump just brought a machete and noise to the amputations the GOP would have preferred to conduct more surgically in quiet rooms.

Proof of their intransigence is the ceaseless veneration of Reagan. I have yet to find among the Never Trumpers’ voluminous output a single repudiation of this disastrous president. If he came back from the grave, they would be right alongside him, castigating “welfare queens” and declaring, in the midst of tens of thousands of deaths, that “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government and I’m here to help.” Cute enough to recruit college Republicans, but not a motto for managing a pandemic and a depression.

As for Trump’s criminal conduct, do we need to be reminded of Iran-Contra, or the S & L fiasco, or the 2008 economic collapse? Trump is a gangster, but the GOP has never shied away from the grift. As Brecht puts it: What is robbing a bank compared to founding a bank? And yes, Trump commuted the sentence of Roger Stone–in the grand tradition of Gerald Ford pardoning Nixon and George W. Bush commuting the sentence of Scooter Libby.

I suggest that the Never Trumpers hose themselves down and stop using the “pure conservative” excuse. They should stop bemoaning the loss of the sort of civil debate they never fostered. They should admit that for sixty years the Republican party has been a home to reaction and repression.

In defending their support of conservative “principles,” the Never Trumpers want us to forget that they ignored the practical consequences of putting the GOP in power: the ransacking of civil society undertaken by corporations, lobbyists, and enterprising bandits. The party’s assault on Obama made little sense in terms of principle; he was practically the last Rockefeller Republican left in DC. Moreover, the GOP attacks displayed flagrant racism long before Trump came on the scene.

In the light of this, it’s implausible to think that all those Representatives and Senators suddenly turned pusillanimous on 6 November 2016. Trump’s dialing of everything up to 11 forced his acolytes in the House and Senate to reveal what they have always been, and what they managed to coat with bland politesse for decades.

So the Never Trumpers should stop chattering about rebuilding that infested party or creating something fresh and pure, and admit that all the diversity they claim to prize can be found within the Democratic party and outside it in a range of liberal, radical, and centrist organizations. Right now, in the world we inhabit, the US Republican party is simply an indulgence that no civilization can afford.

More broadly, since they claim to be interested in Big Ideas, the Never Trumpers should admit that conservatism is at bottom simply a defensive reaction to dispossessed and exploited people coming forward to demand equality and a measure of humanity. Blather about “limited government” and “sane fiscal policy” has always been simply cover for the exercise of power–and now everybody but The Bulwark admits it. Trump is not a betrayal of neoconservatism. He came to fulfill it. He embodies the Reagan mandate: “Government doesn’t work. Elect us and we’ll prove it.”

So, yes, savor along with me powerful videos eviscerating Trump and his sycophants. Hope, as I do, that mockery and indignation and sheer fatigue will sway some of those voters who might admit that they were abysmally stupid in 2016. (Those of us who despise the Clintons still saw the difference between herpes and cancer.) And continue to work, however we can, to keep our society from spiraling into despair.

Just don’t treat the Never Trumpers as anything but what they are. They are our Hessians, our Blackwater special ops, our Shock Troops of Death. Eager to crawl to the front lines and slit throats at nightfall, to become relevant once more, they should be praised for coming to our aid. But when we really needed their particular skills was in the decades leading up to our current catastrophe. Then they failed us.

They’re willing to be cannon fodder, and I’m glad. But assuming we come through this, they should be sent back to their beachfronts. The dogs are waiting.

This blog entry was written early in the day of President™ Trump’s 14 July News conference. After that gibbering display, which ought to provide enough lunacy for a dozen opposition ads, I have to say that he may self-destruct before the Never Trumper brigades get the final boot in.

The one Never Trumper I know who has shrieved himself properly appears to be another cashiered GOP hack, Stuart Stevens. He has a forthcoming book (of course) with the intriguingly frank title It Was All a Lie: How the Republican Party Became Donald Trump. I reserve judgment until I’ve read it, but it could point the way toward some truth-and-reconciliation confessionals to come.

Other comments related to the Trump regime are here, here, and here.

P.s. 17 July 2020: In a similar, but nastier vein, there’s this interview with Rick Wilson and some cartoon characters. Thanks to Diane Verma for the link.

P.P.S. 21 July 2020: In the same spirit, from the never-surrendering Elie Mystal.

P.P.P.P.S 22 July: A WaPo interview with a Lincoln project leader in which he “concedes complicity” in bringing us to this state of affairs.

P.P.P.P.P.S 29 July: Stuart Stevens tells all in NYT, as teaser for the book mentioned above.

P.P.P.P.P.P.S. 11 February 2021: Lincoln Project news: $$$, sexual harassment, beachfront home prices. No dog coverage.

P.P.P.P.P.P.P.S. 8 March 2021: I told you they were mercenaries. Dogs not mentioned.

The Lincoln Project National Virtual Town Hall, 9 July 2020.

Ozu’s silent talkie: PASSING FANCY on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

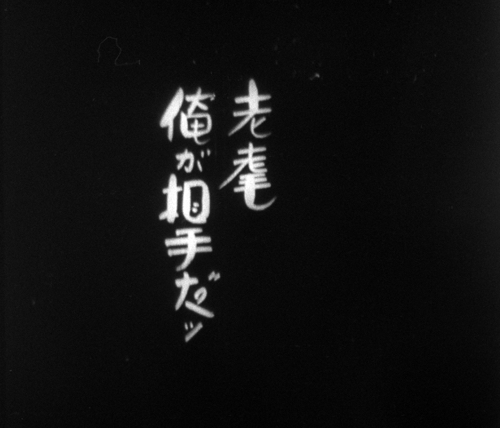

Our newest installment of Observations is now up on The Criterion Channel. In it I consider how Ozu’s Passing Fancy (1933) exhibits his distinctive methods for treating a scene’s space. Now, here’s a preview for a little bonus that will show up there next week. It’s a short on how Ozu sometimes relied on sound in a silent film.

You probably know about Japan’s katsuben, or benshi. He or she stood alongside the screen and accompanied the film–explaining the action, commenting on it, and imitating the characters’ voices while reciting the intertitles. The benshi were usually given scripts for the titles’ texts, but they were also expected to expand on them.

Benshi became celebrities, as strong an attraction as the movies, and they wielded power over some production companies. Benshi might reedit films to suit the performance they wanted to give. One reason that talking pictures came only gradually to Japan was the resistance of the benshi associations to being put out of work.

Filmmakers who resented the benshi’s power seemed to have sought to make the films as free-standing as possible. One strategy was to have many intertitles, which served to anchor the meaning of a scene. More positively, in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema I argue that the presence of a benshi gave filmmakers new storytelling opportunities.

Knowing that the benshi would be speaking the lines in the intertitles, filmmakers could make those titles quite short, creating a swift rhythm. (Contrary to some impressions, Japanese silent movies aren’t slow; even dialogue scenes are likely to be cut fast.) Moreover, the benshi could make conversations more compact than what we find in American films. Instead of a pattern of speaker/title/speaker/listener, your shots could run: speaker/title/listener.

Just as important, filmmakers could count on the benshi to fill in things not shown onscreen. That could allow for some unusual interaction between images and speech.

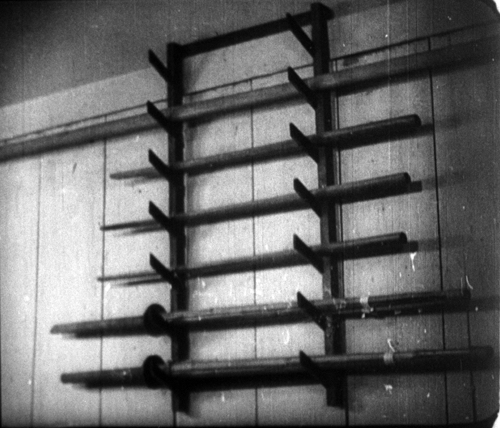

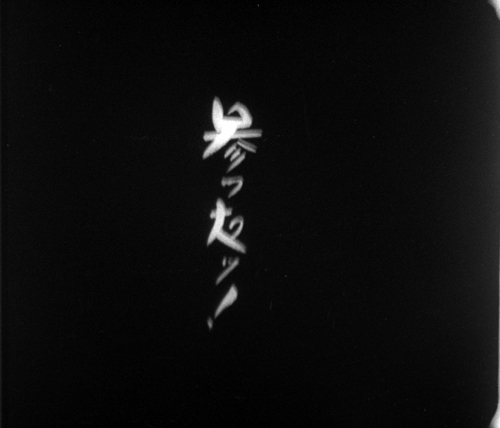

For example, Iwami Jutaro (1937), a swordplay comedy, treats one scene with “offscreen” sound. A bully is watching a kendo match. Cut to the rack of kendo swords, followed by a cry from one fighter, given in an intertitle: “Fool, you’ll be fighting me!”

Cut back to the rack collapsing, as if shaken by the fight. Another title: “I give up!” is followed by a shot of a fallen fighter, beaten.

The shot of the fallen bully anchors the title, but in the flurry of shots we’re invited to imagine the skirmish. Very likely the benshi was shouting the lines while the accompanying music whipped up a burst of excitement. This elliptical treatment of the match suggests that Kurosawa’s Sugata Sanshiro, made only a few years later, was heir to a tradition of off-center rendering of martial-arts combat.

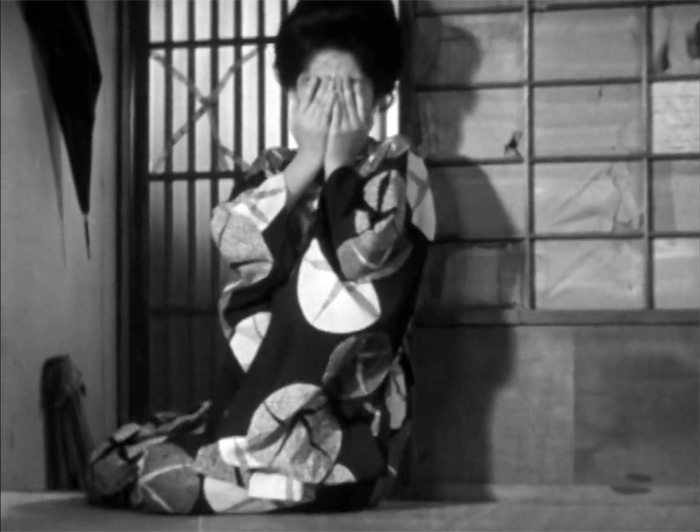

Ozu recruits the benshi for something more ambitious, as I try to show in this bonus. Regrettably, we couldn’t find usable stills of benshi performances from the period, so the stills illustrate modern revivals. Also, I still haven’t seen Suo Masyuki‘s recent Talking the Pictures (Katusben!, 2019), a comedy about benshi culture.

Anyhow, a little analysis of what we have enables us to appreciate how Ozu uses the benshi to emphasize character reactions. The highlight comes in an emotional climax, when the benshi’s sobs would have filled in offscreen action.

Ozu, a fan of Western cinema, would have seen talkies and realized the power of offscreen sound. But I suspect he didn’t need external influences to understand that the benshi’s patter gave directors great freedom in visual narration.

Passing Fancy is one of three masterpieces Ozu released in 1933. (The other two, Dragnet Girl and Woman of Tokyo, are also on the Channel.) The Japanese cinema of this period was one of the glories of world filmmaking, with talent at all levels. Still, very few directors anywhere matched Ozu’s quietly outrageous innovations in form and style, his urge to show us cinema, and so the world, in a poignant, exhilarating way.

Thanks to Kim Hendricksen, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, Erik Gunneson, and the team at Criterion for enabling me to include this clip on our site. Thanks also to Komatsu Hiroshi for information on Iwami Jutaro and Steve Ridgely for correction of one of the intertitles.

For more on the benshi, see the comprehensive study Benshi, Japanese Silent Film Narration, and the Forgotten Narrative Art of Setsumei: A History of Japanese Silent Film Narration, by Jeffrey A. Dym (Edwin Mellon Press, 2003). Fascinating background on the struggles between the benshi and other sectors of Japanese film culture can be found in Joanne Bernardi, Writing in Light: The Silent Scenario and the Japanese Pure Film Movement (Wayne State University Press, 2001) and Aaron Gerow, Visions of Japanese Modernity: Articulations of Cinema, Nation, and Spectatorship, 1895-1925 (University of California Press, 2010).

Another intriguing review of Talking the Pictures is Jessica Klang’s in Variety.

Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema is available for free download here. (Be patient; the file is big.) An earlier Observations segment considered Kurosawa’s cutting of martial-arts action, and a blog entry developed that a bit more.

Another way to make a silent talkie is discussed in this entry on The Donovan Affair.

Passing Fancy (1933).