Archive for March 2012

Pandora’s digital box: Harmony

DB here:

I had thought I was finished with my series on digital projection that started back in December. That was before a late-night trawl of the Internets brought the JEM Theatre to my attention. Sometimes reality has a taste for a dramatic story, and this was one I couldn’t resist.

So I went to Harmony.

All in the families

A birthday party at the JEM Theatre.

For decades exhibiting movies has been a family business. Many regional chains were founded by fathers and brothers and staffed by sons, daughters, and in-laws. The Midwest’s Marcus chain of 700 screens originated in 1935 with grandfather Ben and is run by son Stephen and grandson Gregory. More modestly, Smitty’s Cinema, a nine-screen movies-and-eats circuit in Maine and New Hampshire, was the brainchild of three brothers.

The smaller the venue, the more likely you’ll find a family in charge. The Goetz Theatre of Monroe, Wisconsin, which I profiled earlier, has been in the family from the start. The single-screen Cozy in Wadena, Minnesota, has been run by the Quincers since 1923, with the founder’s great-grandson in charge today. Dirk and Jeri Reinauer have the Sunset Theatre in Connell, Washington. Tom and Barbara Budjanek, who bought Pennsylvania’s Ambridge Family theatre in 1967, are still running it in 2012.

Families pass theatres to each other. The venerable Roxy in Forsyth, Montana, was bought by a couple in 1967. They sold it to their projectionists, one of whom kept it going with his wife. (The theatre went digital in 2010, just in time for its eightieth birthday.) From 1947 to 1959 the Wayne Theatre in Bicknell, Utah, was operated by a husband and wife. Another couple bought it and ran it until 1994, when they sold it to a third husband and wife. A fourth family acquired it in 2008.

The record for husbands and wives running a single-screener might be held by the little town of Harmony, Minnesota. The JEM Theatre on the main street, closed in 1947, was reopened by Bob and Hazel Johnson in 1961. They ran it for twenty-five years. It passed through the hands of five more couples before Michelle and Paul Haugerud acquired it in 2002.

Paul and Michelle met in San Francisco, where Michelle was working for Bear Stearns and Paul had served in the Navy. In 1994 they moved to Harmony to be near Paul’s family. There they raised six children while Paul started a paint and drywall business and Michelle began a career in Web design. “When we bought the theatre,” Paul explained, “we knew it was gonna make no money. We knew it was gonna be basically like doing community service.”

To an extent that people living in cities and suburbs may not appreciate, the JEM has held a central place in the life of the town. By 2011, digital conversion threatened to end that.

Harmony, not far from Prosper

With a population of about a thousand, Harmony sits in farm country close to the Iowa border. As Prairie Home Companion reminds us every week, people of Norwegian descent are found all over Minnesota. What you may not know is that certain areas are also home to Amish communities. Waves of migration made Harmony a center of Minnesota’s Amish culture. Local businesses serve the five hundred households in the town, and tourism brings in some income too. One of the big attractions is Niagara cave, containing fossils pre-dating the dinosaurs. There’s also a major biking trail and a fall foliage tour.

The JEM was named, supposedly, for the first letter in the names of the original owner’s three children (but see the PS below). It helped knit the town together, and under the Haugeruds it became a unique institution.

They made a solid team, with Paul’s expertise in carpentry and engine repair matched by Michelle’s money-management skills. Paul, with no previous theatre experience, learned to thread up the platter projector. “The first few weeks, I would literally sit there with sweat rolling down my face as I pushed the start button. I’d be so nervous I did something wrong.” Paul introduced screenings with announcements and jokes. The Haugeruds knew most of their patrons, but at every screening there were fresh faces from nearby towns in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin.

The JEM screened only on weekends, once each day at 7:30. Paul’s and Michelle’s day jobs made any other schedule impossible. During football season, Fridays brought in few teenagers, but Saturdays were better and Sundays were quite good. Overall, the 200-seat house averaged around 55 each night. On snowy nights, a few souls still braved the Minnesota winter to come see a movie.

The Haugeruds ran the JEM as a family business. There was no paid staff. The Haugerud kids sold tickets and snacks and helped with cleanup. Friends and volunteers came out as well. Michelle made the pre-show video slides of ads for local businesses. Even with low overhead, the theatre barely broke even. All tickets were $3. “We’ve always kept prices low,” Michelle explained, “so families that are financially hardshipped can still get their kids out of the house.”

Most of the JEM’s programs were subruns—movies that had opened nationally two or three weeks before. To avoid courier service costs, Michelle and Paul would make midnight drives to pick up prints from other towns. “I’d call and they’d just be breaking down their print from their last show on Thursday,” she says. “I’d say, ‘I’ll be there in fifteen minutes,’ and at midnight I’d go get the print for Paul to make up on Friday.”

Snack concessions are the core of every theatre’s income, but even here Paul and Michelle offered deals. They priced their candy at a dollar and a big tub of popcorn at four bucks. Soda was sold in plastic bottles, to allow for recycling and to keep costs down. Instead of getting concession items from theatre suppliers, Michelle bought them in bulk at Sam’s Club.

The JEM popcorn developed a following. High schoolers came to pop and bag it for football games. Paul and Michelle encouraged people to bring their own buckets to be filled with corn at a fixed price; some people showed up with shopping bags. The Amish didn’t come to the films, of course, but on some days you could see a horse and carriage lingering outside while the driver was buying a supply of popcorn.

The Haugeruds were generous with free passes as well. Over the years, they have donated hundreds of free passes to help local organizations raise money. At other times, Michelle realized, passes are a good form of marketing. “Give out one, and three more people will come along to pay.”

The JEM wasn’t just for movies. Youth groups held meetings there. Many local kids had their birthday parties there, accompanied by a movie or a videogame. The Haugerud daughters had slumber parties in the auditorium; after a movie, they settled down, if that’s the right word for a slumber party, in sleeping bags down front and in the aisles.

Many in Harmony believed that the JEM brought business to town. Julie Barrett, owner of the Village Square Restaurant across the street (and famous for her daily pies) said, “When people go to the movie, they stop at the Kwik Trip, our hardware store is open until 6:30, so you know they might try to kill two birds with one stone when they come to town.”

Over the situation hovered the fate facing every small town—the hollowing out of the center by the big-box stores down the road. Pull off any interstate highway, and you’ll see that the main streets of small towns have turned into empty storefronts, municipal offices, or struggling boutiques. When the JEM faced the need to go digital, Paul was concerned. “If we take one more thing away it’s going to hurt the community. I’m scared to death that main street is going to look like Harmony in the 1980’s when I was growing up. It was pretty bare.”

Single-screeners

Tonja Lawler selling tickets, Michelle Haugerud selling concessions.

The major distributors and the National Association of Theatre Owners now seem to take for granted that thousands of screens will close over the next few years. Some will fail to convert; others will struggle to pay for the conversion but still fold up. What are the likeliest victims? Those at the bottom of the food chain, the single screens and the “miniplexes” holding between two and seven screens.

These two categories account for over half of all exhibition sites in the US. But they amount to only a small slice of the total number of screens, which is what matters. And the number of small houses is shrinking. During the bankruptcy convulsions of the 1999-2001 period, circuits shed hundreds of screens. Since 2007, the total number of U. S. screens has remained fairly constant, but multiplex and megaplex installations have swollen by 2000 screens. Smaller facilities have lost about the same number—by going out of business.

Hollywood, people like to say, doesn’t want to leave money on the table. But more and more the long tail is a waste of resources. Why bother to prepare and ship a DCP to a theatre that yields a box-office take of less than $300 per day? Many decision-makers among the major distributors would be just as happy to let people in small towns wait a couple of months and catch the film on VOD or disc (rented from a gas station, since the video stores are gone too). As long as the megaplexes publicize the must-see movies, people will know what to buy or rent or stream. If you live in the countryside and you really feel the urge to catch the latest hit, get in your car or pickup and drive an hour to a ‘plex. No vehicle? Too young to drive? Wait for the video.

While digital projection allowed the major distributors to consolidate their power, it also offered a way to streamline and downsize exhibition. The 1600 American single-screen venues are especially vulnerable. For the industry, it seems, any part of film culture that preserves some history or takes root in a community is simply a nuisance. Michelle Haugerud puts it simply. “They don’t care if we go out of business.”

A digital jug

In late spring of 2011 Paul and Michelle decided to try to go digital. A new projection system and sound processor would cost $75,000. “We’ve tried to run it by ourselves and keep it independently owned, but it’s gotten to the point now where we’re looking for some help,” Paul said in July. “It was a difficult decision to ask for the community’s help,” Michelle wrote on her website. “We never wanted to ask for support, but we knew the public deserved to know why we may have to go out of business.”

In late spring of 2011 Paul and Michelle decided to try to go digital. A new projection system and sound processor would cost $75,000. “We’ve tried to run it by ourselves and keep it independently owned, but it’s gotten to the point now where we’re looking for some help,” Paul said in July. “It was a difficult decision to ask for the community’s help,” Michelle wrote on her website. “We never wanted to ask for support, but we knew the public deserved to know why we may have to go out of business.”

They began a fundraising drive. A young patron named Kirsten Mock decorated an old red juice jug for donations and put it on the candy counter. Paul and Michelle set up a designated savings account with a local lawyer’s name attached to make sure people understood that any donations would go only to the projector. A list was kept of all who put their names on donations, and the money would be refunded if the target sum weren’t reached.

The problem was that the JEM, privately owned and operated, wasn’t a nonprofit. Donations were not tax-deductible, and local government agencies couldn’t normally supply grants or other aid. During 4 July celebrations, however, a “Harmony Goes Hollywood” event featured a room in the Historical Society set up with an old projector and theatre seats, with clippings and photos showing the JEM over the years.

A local woman tipped Twin Cities media to the campaign. It was good timing: The US press was starting to notice the nationwide digital conversion. News outlets and TV stations covered the JEM’s crisis. Minnesota Public Radio picked up the story.

By fall, when the campaign had raised about $7200 locally, Paul and Michelle found a nearly new projector for $55,000. They managed to borrow the $48,000 they needed from a local bank. By shouldering the loan themselves, they showed the public that they were committed, and this gesture boosted donations.

As a result, on 11 November, the JEM screened its first movie on the Digital Cinema Package format, Dolphin Tale. On that weekend Paul thanked Kirsten for kicking off the fundraising and gave her a lifetime pass to the JEM. For the older crowd there was Football Monday, when Paul and Michelle projected a Vikings-Packers game. They couldn’t charge admission, but they sold tickets for drawings of prizes donated by local businesses.

Even though they had the equipment, Paul and Michelle still needed to pay for it. Later in November, the Trust for a Better Harmony stepped in to help. Enabled by a generous gift from Ms. Gladys Evenrud, the Trust and a Minnesota agency for community development arranged for a flexible loan package. As a result, the JEM now needed only $28,000, to be paid from community donation. The loan sparked still more offerings to the projection bank account.

New decisions

Paul Haugerud, son Peter (in overalls), and local boys tour the JEM booth.

On 13 January of this year, Paul died.

Commander of the local American Legion, he was cremated with military honors. He left behind Michelle, his six children, his parents, four brothers, and two grandchildren. The town grieved. “There’s nothing he wouldn’t do to help someone else,” a friend said.

Michelle remembers weeks going by in a blur. Friends brought over way too much food. “I had to freeze a lot of it.” She decided she simply had to move forward. She had a full-time job and had Peter, Julia, and Sierra at home, but she would keep running the JEM.

In February, a fundraiser was held at Wheelers Bar & Grill. The event had been planned before Paul’s death, but now it gained a new urgency and poignancy. Wheelers is named for its big roller rink, where Paul had helped out often. Across the day Wheelers held a silent auction and some bean-bag and darts tournaments. Those, along with food, drink, and music, raised an astonishing $16,000. That, plus the balance in the digital account, yielded enough to pay off the bank note for the projector. There have been more fundraising events, including a pancake breakfast. Michelle will soon pay the rest of the money owed. Any funds left over will be used for upgrades. Michelle is considering 3D conversion in a year or two.

Saturday night at the movies

Things have happened so quickly that Michelle hasn’t had time to thank everyone fully on her website, but she adds in a note to me:

It is so overwhelming to think of how the entire community and beyond has come together to make this all happen. I know that even though I am now the owner/ operator of the JEM, this theatre will be here for generations to come. I have had so many thanking me for staying in business. I know this is part due to the conversion and part due to Paul’s passing. I am very grateful for Paul’s family and my friends for being there helping me through all this.

Last Saturday, The Hunger Games drew a robust crowd, mostly groups of boys, groups of girls, and families, with a few elders sprinkled in. Nearly everybody bought concessions. Many carried in buckets for popcorn. The ticket booth was decorated with Easter rabbits and a Darth Vader helmet.

Upstairs, I saw a little room off the projection booth with a porthole. It was Michelle’s and Paul’s “private screening room,” she explained. They would watch the show from an old car seat there.

On the sidewalk outside, Girl Scouts were selling cookies. In the tiny lobby, dozens of construction-paper stars were pinned up, each bearing the name of someone who donated money. Above the booth was hung a framed lobby card for It’s a Wonderful Life.

Thanks to Michelle Haugerud for all her cooperation and enthusiasm. Her informative JEM website starts here. The page devoted to the digital upgrade traces the fundraising process and records her gratitude to the community. , On the same page, scroll down to see a video of Paul running the last 35mm show. Michelle supplied the photo of Paul and Peter above. Many of my quotations come from news stories that are linked on the JEM site.

Statistics on the number of theatres and screens in the US come from the annual reports of the Motion Picture Association of America and from The NATO Encyclopedia of Exhibition. Patrick Corcoran of NATO kindly supplied me with further information.

During my time in Harmony, I couldn’t get access to much material about the JEM in the old days. According to The Film Daily Year Book, the original JEM Theatre (sometimes called the Gem) opened in the mid-1930s. It burned down in 1940. The building next door was renovated as the New JEM, which opened in September of that year. A plain-spoken house of 325 seats, it had fluorescent lighting, satin curtains, three layers of acoustic tile, and a big furnace for the cold months. Its estimated cost was $18,000. For the premiere, a four-page color brochure was printed and sent to 3000 homes in the area. The publication was “made possible thru the whole-hearted cooperation of the businessmen of Harmony who fully realize the value and convenience of this modern, good-looking theatre.” This information comes from “Harmony, Minnesota, Salutes New Jem Theatre, S. E. Minnesota’s Finest Showplace!” The Harmony News, flyer dated September 1940.

Three years later the JEM closed and became a bowling alley. It sat vacant from 1947 to 1961, when Bob and Hazel Johnson reopened it. For a fuller chronology, go to Michelle’s page on JEM history.

Michelle Haugerud and daughter Julia, 24 March 2012.

PS 1 April 2012 Marilyn Bratager writes with this correction about the source of the JEM’s name.

Relatives of mine were the original owners: Joseph Milford Rostvold and his wife, Emma. The J was for Joseph Sr. and Jr., the E for Emma and their daughter Elizabeth, and the M for the senior Joseph’s middle name, Milford, which was the name he was known by. There was a third child, Richard, but they didn’t use his initial as they didn’t want the theatre to be called JERM. 🙂

Thanks to Marilyn for the information!

One summer does not a slump make

Kristin here:

Nor does an entire year. Yet at the end of 2011, the press was trumpeting the fact that the film industry was suffering a slump that might become permanent. After all, “the movies are in a slump!” makes for more catchy copy than “the movies have sunk back to normal” or “the movies are in a downturn from which they will probably recover.” The Hollywood Reporter went for a particularly dramatic approach to year-end coverage of the slump, as evidenced by the title/illustration (see above) of Pamela McClintock’s analysis, appearing in the January 13, 2012 print issue and online.

McClintock cited a number of factors. Young people are no longer going to the movie theaters. The studios are too dependent on big, familiar franchise pictures: “But exhibitors worry that moviegoers are growing impatient with Hollywood’s love affair with the familiar and shortage of original ideas (hello, Avatar!). In 2011, for the first time ever, all of the 10 top-grossing films domestically were franchise titles and spinoffs.” (But wouldn’t that mean that moviegoers are more than ever thrilled with Hollywood’s franchises?) She cites also the rise in admission costs, with ticket prices going up by 5% from 2009 to 2010.

That reason seems the most plausible. People really are tired of ticket prices that have risen faster than inflation. The industry may have pushed the cost up past a point that makes an evening at the movies seem attractive. If, as seems likely, the industry will raise the cost of 2D tickets rather than dropping the cost of 3D ones, we may see a real slump.

The 800-pound thanator in the room

Hollywood box office has its ups and downs, which is only to be expected. One year the successful releases cluster together; another year, they spread out or drop off a little. Any decline will be seized upon by many reporters as a slump, a sign that people are souring on the movies and turning to the many other forms of pop-culture entertainment available in the digital age.

Careful commentators have pointed out that naturally 2011 would be lower than 2010. As the AP’s film reporter, David Germain put it at the end of 2011, “An ‘Avatar’ hangover accounted for Hollywood’s dismal showing early this year, when revenues lagged far behind 2010 receipts that had been inflated by the huge success of James Cameron’s sci-fi sensation.”

Just how much did Avatar affect 2010’s box-office total? The film achieved a worldwide total gross of $2,782,275,172. Of that $1,786,146,809 came in during 2010. That’s comparable to, say, two Harry Potter films.

Predictably, Avatar ran for a long time. It was released on December 18, 2009 and ran for 238 days (34 weeks), closing on August 12, 2010. Naturally its most intense box-office period in 2010 would have been in the early months. Alice in Wonderland opened on March 5, on its way to crossing a billion dollars in international gross. This was a highly unusual synchronization of steamroller films. Still, in early 2011, the fact that the box office was off 20% from 2010 was immediately proclaimed as a signal of doom and gloom to come. Richard Verrier and Ben Fritz suggested that, putting aside some under-performing films, “even hits like Justin Bieber’s ‘Never Say Never,’ ‘The King’s Speech’ and ‘Battle: Los Angeles’ pale in comparison with the early 2010 blockbusters ‘Avatar’ and ‘Alice in Wonderland.’” Given that the first few months of the year are typically the dumping ground for films deemed unlikely to set the box-office on fire, early 2011 was a return to business as usual. Avatar and Alice in Wonderland hardly made for a realistic comparison.

The tentpole effect

We’ve seen that Avatar’s 2010 box office was comparable to two major blockbusters. Now consider the fact that two films released in 2010 grossed over a billion dollars each: Toy Story 3 ($1,063,171,189) and Alice in Wonderland ($1,024,299.904). (Here and throughout this entry, the amounts are given in unadjusted dollars.)

That’s the equivalent of having four very high-grossing films in one year. The only other time a similar pattern emerged was in 2002, when four of the top franchises brought forth a film: Spider-Man ($821,708,551), Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets ($878,979,634), The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers ($926,047,111), and Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones ($649,398,328). It was a perfect storm that has so far not been repeated.

These are exceptional years, so one would expect the box-office to sink afterward. Yet somehow the industry and the world of entertainment journalism see years with such big box-office spikes as forming the new norms against which all other years should be judged. Studio executives seem to think that 2002 or 2010 indicate a realistic goal that they could achieve all the time, if only they could put out the right films. Almost inevitably, articles on declines in box office end with the notion that the films released in that particular year or quarter were just not appealing enough. But of course, there’s no way to deliberately achieve such a combination of blockbusters. Many blockbusters fail, and the big special-effects-laden ones take years to lumber through production. By sheer coincidence, some blockbusters converge.

The lesson to be learned here is that the really big films make so much money that just a few of them–or one James Cameron epic–can by themselves create the sense of the entire Hollywood output going way up or way down. They average out. If Hollywood attendance is dropping, it’s happening very slowly. Other factors are making up for that gradual attrition, as we’ll see below.

2002 was 2002

Journalists in particular have long been using 2002 as a benchmark to measure how badly Hollywood has been doing since. Ben Fritz and Amy Kaufman, in an otherwise good analysis written for the Los Angeles Times, resort to this comparison: “The box-office figure known in the industry as the ‘multiple’—the final box-office take compared to a movie’s opening weekend ticket sales—has dropped 25% since 2002.” The 2002 figure might have been skewed slightly by the fact that the three parts of The Lord of the Rings had an extraordinarily high incidence of repeat viewings and hence were in first run far longer than most films. For The Two Towers, the opening weekend was 18.2% of its total domestic gross (up from 15.1% for the previous part, The Fellowship of the Ring, which was in first run from mid-December, 2001 to August, 2002, half a week longer than Avatar). Spider-Man’s opening was a more typical 28.4% of the total; Attack of the Clones was 26.5%, and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, 33.7%. A more recent film with above average repeat business, Inception (2010), drew only 21.5% in its opening weekend. With Iron Man 2 (2010), the opening was 41.0% of the total gross. Good word of mouth is another possible explanation for some films’ steady or even growing performances after their opening weekends. By the way, the fact that Fellowship of the Ring was in theaters for seven months in 2002 boosted the total box-office beyond the rise created by the four franchise films that premiered within that calendar year.

It’s not clear that the growth in the proportion of the box-office take represented by the opening weekend is directly related to the drop in attendance, as Fritz and Kaufman suggest. One might instead point to the growth in the number of screens, with new megaplexes opening and existing ones adding screens. In 2002 there were 35,500 US screens, but by 2011 there were over 39,300–an increase of nearly four thousand screens. They provide more exposure to the title on opening weekend.

Further evidence is the expansion of opening weekend releases. It was unheard of in the early 2000s to have even a major blockbuster open on 4000 screens. Now it’s not uncommon. At its widest release, The Two Towers was in 3622 theatres, while Iron Man 2 was in 4390. With that many theaters, the number of people able to get tickets for the opening weekend grows, which means that, unless a film generates significant repeat attendance or excellent word of mouth, the box-office take will fall off more rapidly than it used to. But the fall-off doesn’t necessarily mean that fewer people have bought tickets.

Oops! Never mind

The story of the slump suddenly began to look very different as soon as the new year began. At the end of February 2012, Variety reported that domestic box office for the first two months was up 21% over the same months of 2011. It so happens that in the same period of 2011, box office was down 20% against the early months of 2010. And the early months of 2010 saw Avatar going very strongly after its mid-December debut.

The Variety article’s author, Andrew Stewart, pointed out the fact that Avatar had unbalanced the 2010 results. He also pointed out that the fast start out of the 2012 box-office gate resulted from a larger number of films making less on average. But this year’s likeliest high-grossers are yet to come: The Hunger Games, The Dark Knight Rises, and the first part of The Hobbit, with The Bourne Legacy and The Amazing Spider-Man possible mega-hits as well. There are also new films in the Madagascar, Ice Age, and Men in Black franchises coming out. Ann Thompson weighed in a few days after Stewart, pointing out that the increased number of films was not necessarily a problem, since more theaters are being built at a fast clip around the world. More theaters theoretically need more product. (More on that below.)

But an important point about the early hits of 2012 is that they were relatively modest films. They could have been expected to earn far less than blockbusters but still perform well in relation to their production and distribution costs. The Vow, the first film of the year to cross $100 million, is a romance; Safe House a Denzel Washington thriller; and Journey 2: The Mysterious Island a mid-budget family adventure film. This is pretty much what a normal, non-Avatar year looks like early on. (In 2008, David wrote about one early-in-the-year release that was a modest hit, Cloverfield.)

Soon thereafter Chronicle, made on an announced $12 million budget, had pulled in about ten times that internationally and proven that young men, contrary to industry fears, were still willing to go to see movies in theaters. Then The Lorax became the first iron-clad blockbuster. Neither of these is part of a franchise. Talk of a 2011 slump has disappeared. I suspect it may resurface a year from now as a benchmark showing how extraordinarily well Hollywood films did at the box office in 2012.

The 3D effect

2009 and 2010 were the best years for 3D, with Avatar not only dominating world film screens but also luring producers to imitate its success. But in 2011, the advantage provided by the higher ticket prices that 3D permitted began to fade. Last summer I discussed the decline at some length, here and here. I won’t rehash that here. In 2009, 3D films made on average 71% of their box-office grosses from 3D screens, and in 2010 the figure was 67%. In 2011, 56% of business for 3D films came from 3D screens.

The decline may represent the end of the novelty appeal of 3D, as well as the increasing number of 3D films competing in the market. Anecdotal evidence suggests that moviegoers are tired of paying premium prices. The fact that 3D animated features took in a slim one-third of their grosses from 3D screens in 2011 suggests that the cost of a whole family attending together, especially if the younger children can’t keep the glasses on, has begun to hamper the format.

Thus 3D may have contributed to an artificial, temporary rise in total box-office figures in 2010. This would inevitably be reflected as a decline in 2011, as more people opted for 2D screenings of popular films.

(Figures from Screen Digest, February, 2012, p. 37.)

It’s a big, wide, ticket-buying world out there

All the box-office reports and prognostications discussed above are based on domestic box-office grosses, which in practice means the USA and Canada. But in parallel to the reports of a slump in 2011 BO figures, there were reports of impressive growth in foreign film markets.

Take the United Kingdom, traditionally a top consumer of Hollywood films. 2011 saw the total box-office gross surpass £1.5 billion for the third straight year. That total grew by 5% over 2010. Films from Hollywood’s Big Six studios took 74% of the market. Local productions had a particularly good year, with three in the top ten: The King’s Speech, The Inbetweeners Movie, and Arthur Christmas. Even if that success continues, however, Hollywood will have a healthy share of the market.

More generally, Variety announced in mid-January, “It was business as usual at the 2011 international box office. And business is booming.” (“International” refers to all markets apart from the USA and Canada.) The Russian market is growing quickly, with its total gross of $1.16 billion in 2011 representing a rise of 20% from 2010. Russian films make up only 14.7% of the market, with the rest mostly coming from Hollywood.

The Chinese market is huge, passing $2 billion for the first time in 2011, up 29% over the previous year. (See below.) There is a Chinese quota of 20 foreign films per year, but a recent decision to allow more 3D and Imax films in may herald a gradual opening of the market. Certainly the blockbusters that make their way into China are popular. According to Hollywood Reporter, for the first time, China was Paramount’s highest grossing foreign territory, with $303 million at the box office, largely thanks to Transformers: Dark of the Moon. Still, China yields only about 15 cents on the dollar back to the distributor, a situation likely to change only slowly.

Brazil, India, and Eastern Europe have seen healthy expansion as well.

Even Hollywood comedies, notoriously hard to sell abroad, are becoming more popular. In 2011, Bad Teacher, Just Go With It, and Friends With Benefits all made around $100 million outside North America. Very unusually for comedies, they also grossed more money abroad than domestically.

The major studios’ box-office grosses abroad were: Paramount, $3.19 billion; Warner Bros., $2.86 billion; Disney, $2.2 billion; Fox, $2.15 billion; Sony, $1.83 billion; and Universal, $1.3. (These figures represent the total amount paid for tickets; only a portion returns to the studio.) I take this information from Hollywood Reporter, which notes that the big studios are increasingly buying local, foreign-language films to distribute within those domestic or regional markets.

There’s more to Hollywood than tickets

One might conclude from all the stories about the box-office slump of 2011 that the big studios’ profits would be down, at least a little. Actually, a studio had to work hard not to see profits rise last year. That’s partly because they make things other than movies and partly because movies make a lot of money that has no direct connection with theatrical distribution.

The February 24, 2012 issue of The Hollywood Reporter published a helpful summary, “2011 Profitability: Studio vs. Studio.” (The online version is behind a paywall.) As the authors point out, the studios calculated their profitability on different criteria, so direct comparisons among them are difficult. Nevertheless, the article shows that most studios were profitable and suggests why.

Time Warner’s filmed entertainment wing had a 15% rise in profits from 2010 to 2011. That resulted in part from the release of the final Harry Potter film. Beyond that, however, there was the fact that WB now manufactures video games and shipped 6 million copies of Batman: Arkham City. (That game wouldn’t exist without the film series, so we see synergy at work here.) It also produces over 30 TV programs, including The Big Bang Theory and Two and a Half Men.

News Corps.’s film studio, Twentieth Century Fox, saw profits rise 9%. Rise of the Planet of the Apes boosted the bottom line, but so did strong home-entertainment sales. The TV wing produced Glee and Modern Family. “Films licensed to pay TV and free TV helped, as did digital content-licensing deals. The TV licenses are estimated to have been worth about $200 million in the second half of the year.” Thus quite apart from their box-office takings, films made a lot of money for the studio.

The profit from Sony’s film unit jumped an impressive 95%. $278 million of that was a one-time sale of merchandising rights for the new Spider-Man movie. The Smurfs was the studio’s top earner at the box-office, and according to The Hollywood Reporter, “The division also benefited from stronger-than-expected DVD sales of The Green Hornet and Battle: Los Angeles.”

Disney was the only studio to face a decline in profitability. Its profits slipped 20.5%, though they were hardly meager at $656 million. The disappointments of Mars Needs Moms and Cars 2 are largely to blame. Disney’s current attempt to create a new blockbuster franchise in John Carter clearly won’t reverse the trend.

Paramount’s profits were the lowest but improved the most in 2011: 128%. The growth seems due largely to the Transformers franchise and high income from a 2010 deal between Epix (Paramount’s 51%-owned VOD channel) and Netflix.

The Hollywood Reporter was unable to obtain figures for Universal.

This overview hints at the underlying factors that make assessing the health of the film industry through box-office figures alone a shaky process. Ideally we would have figures on DVD and Blu-ray sales, as well as on licensing deals for streaming and other digital distribution systems. But this information isn’t made public by the studios.

The uncertainties and appeal of post-theatrical markets

This is a pity, since the real crisis facing the film industry today is not fluctuations in box-office income. It’s how to deal with the rapidly changing post-theatrical revenue stream: the sudden proliferation of other ways to sell or rent films for viewing on the tablets, game consoles, cell phones, computers, and other devices now driving the death of tape- or disc-based home entertainment. Studios see new ways to make money and are at war with exhibitors about how short a window there would be between theatrical release and the various forms of video release.

Early in this proliferation of online-based distribution, studios continued to concentrate on selling DVDs and later Blu-rays. They licensed the rights to rent films on DVD or via streaming to Netflix and other companies. Now they’re beginning to realize that they don’t need the middleman, but they haven’t found models for handling all forms of post-theatrical distribution themselves. In the meantime, Redbox kiosks rent DVDs for a pittance and make the home-video experience seem like something that barely needs to be paid for–and certainly isn’t an Event.

The decisions the studios make about post-theatrical are crucial to the health of the film industry. Movie City News publisher David Poland recently summed up the situation, pointing out that the theatrical release is still far and away the biggest single generator of income per viewer for the industry. His essay is worth reading in full, but here is the gist in terms of how home-entertainment revenues relate to theatrical income:

1. Post-theatrical is already a blur for consumers and it will only get more so. People will expect access at all times on any device for a low, low price… either in a subscription model or a per-use price point of $2 or less.

2. Theatrical will soon be the ONLY revenue opportunity that stands apart from that post-theatrical blur. No other revenue stream will ever again generate as much as $10 a person… or even $5.50 per person.

3. Consumers adjust to whatever window you offer. But history tells us, the shorter the theatrical-to-post-theatrical window for wide-release movies, the more cannibalism of the theatrical.

4. Just as the DVD bubble could not be pumped back up after it was deflated by pricing aggression, theatrical will not survive a significantly shorter window to post-theatrical as we now know it… and once it is broken, it will not be able to be fixed. And that revenue stream will NOT be replaced by what is now post-theatrical. It is simply money that will be lost, never to be recovered.

Theatrical will never be The Drink again. You’re looking at a 2 month window for most studio films vs decades of post-theatrical revenue opportunities. It’s not an even fight. But take a deep breath and look at the obvious… for theatrical to still be as much as 40% of the revenue of a studio film is bloody amazing. It’s not the past. It’s not ’39 or ’69 or even ’89. But it’s a LOT of money. And it is insane to take it for granted or to dismiss it, because there is no proof out there that I have ever heard that suggests that theatrical revenues gets in the way of post-theatrical revenues… only the other way around. Why? Because theatrical is the unique proposition. It’s post-theatrical that really has to compete with EVERYTHING the world has to offer.

(David’s post came in response to one by Mike Fleming on Deadline.)

If the studios start selling their films in various digital forms for a dollar or two, and do so in ways that cannibalize the theatrical market, there will come a point where many people stop going to theaters and stay home to do their movie viewing. So there will need to be many more purchasers of that film than there currently are to make up the difference between that cheap sale and the price of a movie ticket. Without a boost in consumers, post-theatrical income would fall, and the studios wouldn’t be able to afford to make the sorts of films that currently generate the most money.

Whether David’s analysis is too pessimistic remains to be seen. But he points to a far bigger problem than a largely illusory drop in box-office figures.

Jumping to conclusions

The notion that 2011 saw a serious slump results from comparisons that make for catchy headlines. But sometimes a situation can prove misleading. Consider the title of a Variety article from February 23 of this year: “Imax profit plunges to $6.3 million.” Can this be the end of Imax? Yet read on:

Imax profit fell last quarter to $6.3 million from $54 million, mostly on a major tax benefit the year before. Revenue eased by $2 million to $67 million.

Without the tax and other items, income fell to $9 million from $14 million, in line with expectations given a soft box office.

The company said 2011 was a year of record signings and installations, with 497 Imax theaters installed in commercial multiplexes, up 33%, led by China, Russia and North America. CEO Rich Gelfond said the company will add focus on South America, including four new theaters in Brazil, Western Europe and India, where a recent deal will bring Bollywood titles to Imax. It will expand local film production from China into Russia and France.

(Note: The title of this story was subsequently changed to “Imax, Dish, Liberty stocks rise” when it was revised to add the fact that Imax’s stock rose 4.5% on the above news.)

The moral is, the obvious interpretation is not always the correct one. The implication of box-office fluctuations needs analysis beyond a simple comparison of ups and downs from one year to the next.

Moviegoers at the Super Cinema World in the Metro City shopping mall, Shanghai, China

FILM ART: AN INTRODUCTION reaches a milestone, with help from the Criterion Collection

[UPDATE, March 8, 2016: Film Art has now appeared in its eleventh edition, which, among other things, includes additional online Connect Film examples based on the partnership with the Criterion Collection mentioned below. For more information, see here.]

Somehow round numbers seem significant. This summer, Film Art: An Introduction is due to be published in its tenth edition.

We first set out to write the book in 1977, and it appeared in 1979. We’ve been gratified that it has retained an audience of teachers, students, and general readers over the ensuing decades. During that period, we’ve revised it to keep up with changes in filmmaking, in film studies, and in our own sense of what makes cinema a distinct artistic medium. At the outset we wanted to represent many eras of film history, a wide range of international films, and such important categories as documentary, experimental, and animated films. Our revisions over the years have tried to keep these goals in mind. At the same time, we realize that one way to engage students with ideas about film is to pay some attention to films they know, to enable them to look and listen to familiar movies in new ways.

We think we’ve stayed loyal to these purposes across nine editions. But with the fateful number ten we think we’ve stepped up to a new level. We’ve made many changes to the book that we find exciting; more about these below. The most dramatic development, however, comes through our new online partnership with The Criterion Collection.

Most teachers are familiar with Criterion and its high-end series of DVD and Blu-ray releases of classic and important contemporary films. In 1984, Criterion pioneered the genre of supplements, working at the time with laserdiscs. The team are 100% cinephiles, and they continue to set the standard for a rich array of bonus materials, all the making-of films, interviews, and documents that are of such interest to fans, scholars, students, and aspiring filmmakers. Now, with Criterion’s kind cooperation, we have produced a series of online examples tied to Film Art that will use scenes from several of their classics.

Film Art was the first introductory film textbook to use frame enlargements rather than publicity photographs as illustrations. Other textbooks have since imitated this approach, since it’s a vital tool when teaching students to analyze films. Nevertheless, even whole pages full of frames can’t fully convey the effects of techniques such as camera movement, graphic matches, staging in depth, and sound. The next logical step would be to use examples with scenes from movies, adding graphics and voiceover commentaries to clarify the points being made.

Problems of clearing rights and questions concerning the limits of fair use have made it difficult for textbook authors to supply adequate, high-quality moving-image examples on DVDs or online. The Criterion Collection has allowed us to make this big next step. We’re extremely proud of this new partnership, and we’re grateful to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrikson, Tyson Kubota, Giles Sherwood, and the rest of the Criterion Collection team for their generosity and help. Peter has written a blog about the new arrangement.

Online examples using clips from Criterion Collection films

The result is an hour-long set of twenty examples called Connect Film. Seventeen of these center around excerpts from film classics from the 1930s to the 1980s. David and I wrote the scripts and recorded the commentary tracks. The production, direction, editing, and special graphics were done professionally by Erik Gunneson, a filmmaker and Faculty Associate here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.The Criterion scenes are presented as moving images rather than still frames; it’s as if the sort of examples we use in Film Art have sprung to life. Erik has also produced three original demonstration videos laying out basics of lighting, camera lens length and movement, and continuity editing.

So why not check out one of our examples? Criterion has posted “”Elliptical Editing in Vagabond (1985),” in its entirety, on its YouTube page. Go here or watch it at the bottom of this post.

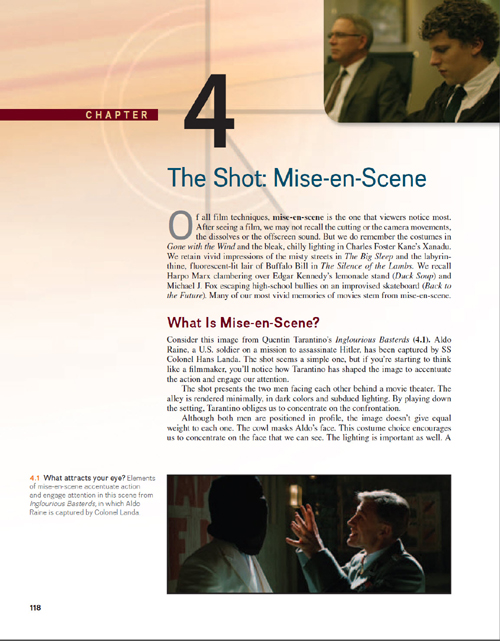

Chapter 4 Mise-en-scene

Film Lighting Demonstration This video clearly contrasts the results of side-, back-, and other types of light, as well as the principles of the three-point lighting system.

Light sources in Ashes and Diamonds (1958) The three sources of the light in the opening of the famous church scene are described and also indicated by colored arrows.

Available Lighting in Breathless (1960) This example starts with an extract from an interview with cinematographer Raoul Coutard, produced by the Criterion Collection. Coutard describes shooting without supplemental light in the lengthy bedroom scene, followed by an illustrative clip.

Staging in Depth in M. Hulot’s Holiday (1953; above) A scene of M. Hulot nervously watching a descending lump of saltwater taffy. The clip is run, then repeated with commentary discussing the comic possibilities of deep-space staging.

Color Motifs in The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) Yellow is associated with the bees in this film, but also with the malaise of Spain in the wake of its Civil War. The scene in which the color comes to be associated with the bees is shown, with still frames and commentary discussing other shots where yellow is prominent.

Chapter 5 Cinematography

Lens Length and Camera Movement Demonstration video contrasting the effects of long, medium, and short lenses. Erik also illustrates different types of camera movement.

Tracking Shots Structure a Scene in Ugetsu (1953; above) A wife and son bid farewell to a departing boat. Using a split-screen technique, we lay out the shots and show how camera movements are used to add to the ominous, poignant effect of the scene.

Tracking Shot to Reveal in The 400 Blows (1959) While the tracking shots in the Ugetsu example follow the characters’ movements, a scene from The 400 Blows shows how the camera can create other effects by moving on its own.

Style Creates Parallelism in Day of Wrath (1943) Similar camera movements prompt us to compare two scenes.

Staging and Camera Movement in a Long Take from The Rules of the Game (1939) In a scene that is rarely examined in this much-analyzed film, we trace out how a busy scene in a hallway, as guests head for their bedrooms, lays out the setting and highlights minor characters.

Chapter 6 Editing

Editing with Graphic Matches in Seven Samurai (1954) We use this example in discussing graphic matches in Film Art, but it’s hard to get a sense of the patterning from stills, So this clip shows the scene in its context and then replays the series of matches, freezing and laying them out across the screen.

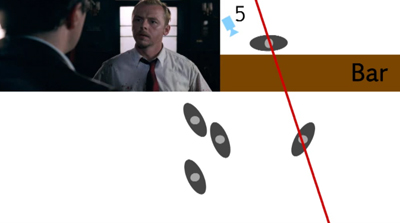

Shifting the Axis of Action in Shaun of the Dead (2004; above) Erik uses stills and overhead diagrams to show how the axis of action can be shifted when characters turn their heads and when new characters join the conversation.

Crossing the Axis of Action in Early Summer (1951) A friendly argument between Noriko and two of her friends employs cuts that consistently move back and forth across the axis of action. An overhead diagram marks the camera positions shot by shot.

Crosscutting in M (1930) Through a first run-through and then a replay with freeze-frames, we study how editing compares gangsters meeting and police meeting.

Elliptical Editing in Vagabond (1985) The enigmatic heroine lives her nomadic life, moving from place to place and meeting a variety of people, rich and poor. In a scene depicting her hitchhiking from near a convent to arrive in a barn, we show how the editing propels our interest but leaves out items of narrative information that increases the mystery of her character.

Jump Cuts in Breathless (1960) Some of the most familiar jump cuts from Breathless are illustrated in Film Art. This example uses a later scene in a cab which uses an unusually large number of such cuts. How many? Let’s count and see.

Chapter 7 Sound

Sound Mixing in Seven Samurai (1954) Our text describes the rich sound mix of the final battle of Seven Samurai, with rain, horses’ hoof-beats, men’s shouts, and other sound effects–all without music. Description, though, goes only so far. Now we can let readers listen for themselves.

Contrasting Rhythms of Sound and Image in M. Hulot’s Holiday (1953) Jacques Tati manages to create a double joke when musical tempo clashes with figure movement.

Offscreen Sound in M (1931; above) Even at the dawn of sound, Fritz Lang found inventive ways to avoid static dialogue scenes. Police raid a basement tavern, and even when there’s little movement onscreen we hear bustling activity outside the frame. Some shots, like this one, recall camera angles from earlier scenes.

Chapter 10 Animation

What Comes Out Must Go in: 2D Computer Animation Most of us are curious about computer animation, not least because it offers tools that amateurs and would-be filmmakers can learn to use. We show how independent filmmakers can get high-quality results in My Dog Tulip (Paul and Sandra Fierlinger, 2010) and Sita Sings the Blues (Nina Paley, 2008; above).

Instructors can stream any of these items in their classes, or students can watch them on their own.

Decisions, decisions

Chungking Express: To hear the voice on the line, or not?

Central as the Criterion extracts are, we’ve made other changes. We’ve done a top-to-bottom rewrite of the text, trying to make it more conversational, more like our blogging. We’ve updated our account of digital filmmaking and we’ve incorporated new information on digital distribution and exhibition–the sort of matters you can find in more detail in David’s Pandora series (which started here).

We’ve tried to make film art tangible for students by asking them to imagine alternative approaches to storytelling and technique. In keeping with this angle of approach, we’ve highlighted decision-making processes: the concrete choices faced by directors, cinematographers, editors, and other creative workers. One of the salient features of Film Art since the beginning has been its effort to blend the point of view of the critic or analyst with the point of view of the filmmaker. Here’s a passage from the first chapter.

Films are designed to create experiences for viewers. To gain an understanding of film as an art, we should ask why a film is designed the way it is. When a scene frightens or excites us, when an ending makes us laugh or cry, we can ask how the filmmakers have achieved those effects.

It helps to imagine that we’re filmmakers too. Throughout this book, we’ll be asking you to put yourself in the filmmaker’s shoes. This shouldn’t be a great stretch. You’ve taken still photos with a camera or a mobile phone. Very likely you’ve made some videos, perhaps just to record a moment in your life—a party, a wedding, your cat creeping into a paper bag. And central to filmmaking is the act of choice. You may not have realized it at the moment, but every time you framed a shot, shifted your position, told people not to blink, or tried to keep up with a dog chasing a Frisbee, you were making choices.

If you take the next step and make a more ambitious, more controlled film, you’re doing the same thing. You might compile clips into a YouTube video, or document your friend’s musical performance. Again, at every stage you make design decisions, based on how you think this image or that sound will affect your viewers’ experience. What if you start your music video with a black screen that gradually brightens as the music fades in? That will have a different effect than starting it with a sudden cut to a bright screen and a blast of music.

At each instant, the filmmaker can’t avoid making creative decisions about how viewers will respond. Every moviemaker is also a movie viewer, and the choices are considered from the standpoint of the end user. Filmmakers constantly ask themselves: If I do this, as opposed to that, how will viewers react?

Even if the reader never makes a movie, we think that getting comfortable with this framework can sensitize us to the power of cinema as an art form.

Of course, we also want to understand the finished film. We need to look at how the choices coalesce into patterns of meaning and effect. This is the holistic bent that the book has always had: we try to understand the choices in the context of the whole film and its purposes. To a large extent film form and film style are the terms we as analysts apply to the patterns of choices that shape our experience.

That emphasis on pattern is something that carries through all of our Film Art editions. It’s valuable to notice techniques or story twists in isolation, but we gain as well from seeing them as parts of larger patterns of organization. Such patterns and processes are highlighted in the case-study analyses in each chapter, as well as in the collection of analyses in Chapter 11. Likewise, Chapter 12 tries to trace some major strategies of form and style across history. The variety of films we consider allows us to spotlight some traditions that are less widely known than the Hollywood one–from France, Italy, Germany, Japan, Hong Kong, and other territories. Cinema is a global art, and we try to recognize that.

Over forty years we’ve learned a great deal about cinema from films and the people who make them. For this reason it’s been stirring to meet many filmmakers from North America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East who tell us that they have learned something from Film Art. We offer the new edition in that spirit of common learning: to better understand a medium that we all love.

Talks, pictures, and more

Hard though it is to believe, our dear friend and colleague Janet Staiger is retiring this year from her post as the William P. Hobby Centennial Professor of Communication at the University of Texas. About a year and a half ago, Janet joined us in writing an essay celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of our collaborative volume, The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Several of our other books have gone out of print, but that one remains available. We’re convinced that its success rests on the fact that the three of us were able to contribute different areas of expertise that meshed seamlessly to cover what turned out to be a far more ambitious topic than we initially envisioned.

We’re delighted to help celebrate Janet’s retirement, since the Department of Radio-Television-Film has invited both of us to lecture at an event to pay tribute to Janet. We’d love to see any of you in the Austin area on March 19. We chose our topics without planning it that way, but they end up book-ending the classical era. David will be speaking on the 1910s, when the early cinema was coalescing into the art of “the movies,” and Kristin deals with the question of how one can deal with a contemporary event that has not yet run its course. (KT)

Short film

The American release of Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film, as well as the first Best Foreign Film Oscar for an Iranian film, A Separation (Asgar Farhadi), have kindled a new interest in Iranian cinema just as some of its most prominent practitioners are dealing with exile, house arrest, and censorship. The International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran has recently posted a short film, Iranian Cinema Under Siege, which lays out the issues succinctly.

Earlier many cinephile sites, including ours, called attention to Panahi’s plight. Anthony Kaufman updates us on his still-undetermined fate. (KT)

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun (cont’d)

Lynda Barry, Ivan Brunetti, and Chris Ware share a mic.

Our Arts Institute has brought Lynda Barry to campus as an artist in residence this spring, and it’s been a breath of fresh air—actually, make that “blast.” Kristin and I have loved Barry’s work since the 1970s, but only recently did we learn that she was born in Wisconsin and still lives here.

Barry’s UW webpage is a captivating foray into Barryland, and her course, “What It Is: Manually Shifting the Image,” has been open to anyone interested in exploring drawing and/or writing. Convinced that art is a biological phenomenon (“Anybody can make comics,” she says), she encourages people to expand their creative powers without fear of being considered unskillful.

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk on with guest Matt Groening, and will interview Dan Chaon (3 May). Her first pair of invitees, on 15 February, was Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti.

You know I was there.

In fact, I came ninety minutes early to get my front row seat, alongside comics guru Jim Danky. Good thing too; by the time the session started, the big lecture hall was packed.

The first part of the session was a brief panel discussion among Barry, Brunetti, and Ware. As if by design, the table mike didn’t work, so Barry’s lavaliere, threaded up through her pants and blouse, had to be yanked out and stretched across the table when her guests wanted to talk. Result shown above.

Barry called Brunetti a master of balancing the verbal and the visual aspects of comics, and she introduced Ware as “the Wright Brothers” of the graphic novel, with Lint as his Kitty Hawk. Then the two guests, who live in Chicago and get together for Mexican lunch once a week, talked about their influence on one another. Brunetti says that seeing Ware’s work in Raw made him rethink comics altogether. Ware finds in Brunetti “an honest critic.”

Then Ware left the stage to Brunetti, who took us through his career in PowerPoint. He traced the influence of comics like Nancy and Peanuts on his pretty but edgy big-head style, and he talked about the autobiographical impulse behind much of his work. (“I draw these things to make fun of myself.”) Like many comics artists, he’s fascinated by cinema—be sure to check his “Produced by Val Lewton” page—and some of his New Yorker ensemble panels have the fluid connections we find in network narratives.

In all, it was a lively session that reminded me, among other things, how comic-crazy our town is. Not to mention our state: don’t forget Paul Buhle’s Comics in Wisconsin. That book is filled with work by Crumb, the Sheltons, Spiegelman, etc. It’s as well a tribute to enterprising publisher Denis Kitchen and the now-departed Capital City comics distribution firm. (DB)

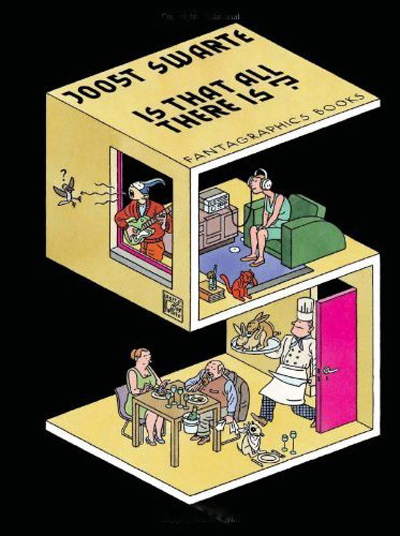

Le mot Joost

I got a little chance to talk to Ware, and we shared our admiration of Joost Swarte, one of the greats of cartooning. Readers of this blog may recall my shameless promotion of Swarte’s work (here and here and here); one of the big events of my fall was getting to meet him in a Brussels gallery. As chance would have it, a couple of days after Barry’s event, I got my copy of the new Swarte collection Is That All There Is?

The book is a fine introduction to work that has for too long been restricted to French and Dutch publications. You get to meet the infinitely knowledgable Dr. Anton Makassar, the lumpish Pierre van Genderen, and the hip but mysteriously ethnic Jopo de Pojo. You also get the first statement of Swarte’s idea of the “Atom Style” of postwar design, connected to the “clear line” school of cartoon art. The book, done up in gorgeous graphics, is graced by an introduction by none other than Chris Ware.

It’s sort of hard to write an introduction for a cartoonist you can’t completely read. . . . I’ve read plenty of his drawings, however. Studied, copied, and plagiarized them, actually; the precise visual democracy of his approach compelled me as a young cartoonist to consider the meaning of clear and readable or messy and expressive, and it was the former which won out.

Now that he mentions it, there is a line running from Ware’s obsessive schematics of narrative space (and time, as Barry says) straight back to the fluent precision of Swarte’s design. Both artists invite your eye to discover things at all level of scale and visibility, while leading you, in Hogarth’s phrase, “on a wanton kind of chase.” (DB)

Derange your day with Feuillade

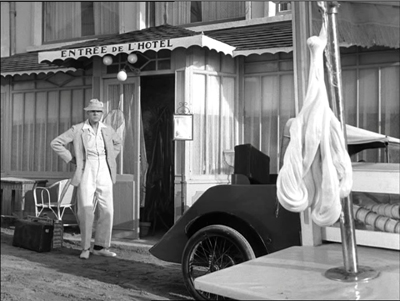

Two patient, ambitious researchers have contributed to our knowledge of Louis Feuillade’s work, a central concern of DB’s writing and this blog (here and here, in particular). They also teach us intriguing things about cinematic space.

First, Roland-François Lack of University College, London hosts The Cine-Tourist, a site that traces the use of Paris locations in films. His devotion to Paris equals that of the city’s filmmakers, so he provides a thorough canvassing of areas seen in Les Vampires, Fantômas, and Judex. Beyond Feuillade, you can find the places featured in other movies, including L’Enfant de Paris and Le Samourai. Roland-François has even solved the riddle of what movie house Nana visits in Vivre sa vie.

Hector Rodriguez of the City University of Hong Kong has set up a site devoted to Gestus. It’s a program that tracks vectors of movement in a shot and generates abstract versions of them that can be compared with action in other sequences. Gestus can whiz through an entire film–in this case, Judex–and come up with an anatomy of its movement patterns. Hector sees the enterprise as sensitizing us to movement patterns that we don’t normally notice. It also provides a dazzling installation.

Gestus’ ability to generate a matrix of comparable frames recalls Aitor Gametxo’s Sunbeam exploration. But Aitor was interested in how Griffith maps adjacent three-dimensional spaces. Hector’s project focuses on two-dimensional patterning, specifically the deep kinship between different shots when rendered as abstract masses of movement. And while the Sunbeam experiment lays out how spectators mentally construct a locale, Hector is just as interested in friction. “The system invites, confuses, and sometimes frustrates the viewer’s cognitive-perceptual skills.”

That, of course, is part of what cinema is all about. Visit Roland-François’ and Hector’s sites and have a little derangement today. (DB)

If you’re unfamiliar with Chris Ware’s work, a good overview/interview can be found here. Swarte’s stupendously beautiful site is here.

PS 12 March: Because I’ve been immersed in other stuff, I didn’t realize that Matt Groening actually showed up for Barry’s session! And I missed it! Hence the strikeout correction above, initiated by Jim Danky. More on Groening’s visit here.

Echoic patterns of stooping in Judex, as revealed by Gestus.