Archive for September 2015

NIGHTMARE ALLEY: Do we hear what he hears?

DB here:

In the 1940s, American cinema turned wildly subjective. Visions, daydreams, nightmares, optical and auditory POV, inner monologues, flashbacks, and stream-of-consciousness montages were popping up everywhere. Sometimes these techniques rendered what it felt like to be the character at that moment. At other times, they were occasions for gags, or padding, or spikes of emotion, or flamboyant spectacle.

Sometimes they were just weird.

Siren song

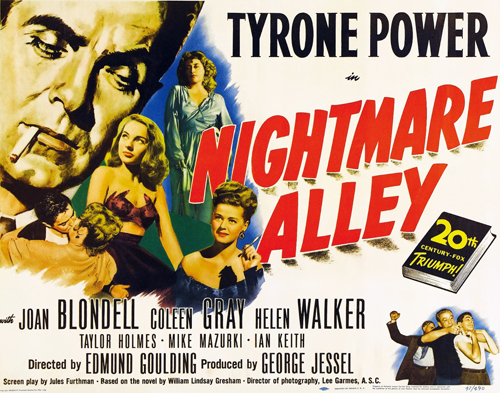

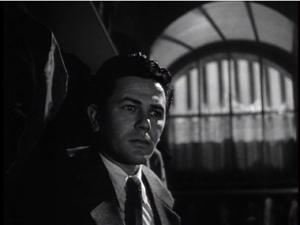

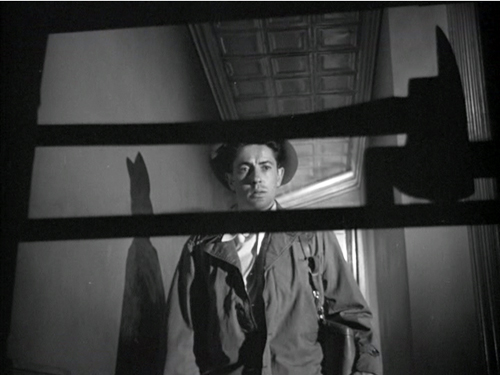

One of the most intriguing passages in Forties films comes at a climactic moment in Nightmare Alley (1947, the year I was born). Spoilers ahead.

Stan Carlisle has been involved in a complicated swindle with the help of psychologist Lilith Ritter. He has entrusted her with $150,000 in cash extracted from their mark. When the plan goes wrong, he reclaims the money and heads for the railroad station to meet his girlfriend Molly.

In the cab en route to the station, Stan discovers that the wad of cash Lilith has given him consists of 150 singles. He returns to her apartment to confront her. There Lilith suddenly goes coldly clinical, declaring that Stan is deluded. Just as he thinks he killed a man in Texas, and he has imagined that she’s involved in his swindle. She denies any collusion with him, but does hint that she could get him indicted for the killing.

Since he has been growing more anxious, her calm stream of lies unnerves him. And since she records all her sessions with her patients, she has his first visit as a confession to the Texas killing. She has been careful to never record their swindle plot.

As Stan gets more panicky, we hear a police siren. He reacts, but Lilith does not. She claims not to hear it; she says he’s just imagining it, like everything else. When she offers to take him to a hospital, he pulls away and flees, without his money.

Here’s the scene.

Is the siren objectively in the scene, or is it in Stan’s head?

Lilith says she doesn’t hear the siren, so it might be subjective, manifesting Stan’s guilty conscience. And all the psychologist’s talk about hallucinations may have induced one in him. But the siren isn’t distorted in the way most auditory imaginings are; it seems plausibly part of the story world. And many viewers (including me, on my first viewing) assume that Lilith or her servant Jane has called the police, and the cops are now arriving. Lilith could be pretending not to hear the siren in order to convince Stan he’s loco. She does tell him to stay for a sedative.

There are several oddities here besides the siren. For one thing, Jane has made her entrance keeping Stan covered with her pistol. When Stan and Jane leave the bedroom, we see Jane hovering in the background.

As Lilith comes out she cocks her head screen left, signaling to Jane, and swivels the pistol firmly toward Stan.

Once Stan and Lilith get into their argument, though, Jane is no longer seen or heard. She’s last glimpsed as a sleeve on its way offscreen.

We never see Jane definitely exit the room. Is she there or not? Did Lilith’s head gesture mean “Stand over there to keep him covered” or “Go off and call the police”? The film’s continuity script (typically a transcript of the editor’s version with dialogue and effects but without music) says only “Jane crosses and exits scene.” That could mean she leaves the room or merely leaves the frame.

Moreover, we learn from cinematographer Lee Garmes, who shot Nightmare Alley, that Goulding preferred clearly signaled entrances and exits.

He had no idea of camera; he concentrated on the actors. He had the camera follow the action all the time. He was the only director I’ve known whose actors never came in and out of the sideline of a frame. They either came in a door or down a flight of stairs or from behind a piece of furniture. He liked their entrances and exits to be photographed. I like that; they didn’t just disappear somewhere out of the frame-line as they so often do.

“Disappear somewhere out of the frame-line” is just what Jane does.

Jane’s presence or absence matters because of the quarrel that ensues. When Lilith announces her betrayal of Sam, we might expect the muscular Stan to attack her, slapping her around like the good noir sucker he is. But he meekly takes her assault. True, he’s coming apart, but maybe he’s holding back partly because Jane still has him covered from offscreen. That assumption seems validated at one point, when Stan’s nervous glance sharply off right suggests that she’s still there with her pistol. It’s after that glance that he warns Lilith not to call the cops.

Of course he could be imagining Jane in another room calling the police. On the other hand, if we assume that Jane remains offscreen, Lilith’s cool story about Stan’s breakdown becomes motivated as a performance in front of a witness who can back her up.

Maybe the handling of Jane is just clumsy direction on Goulding’s part? Or just conciseness? Still, there’s that siren. If Jane is in the room all the while, and we don’t hear her telephone the cops offscreen, the siren can’t be the result of a call for help. And it’s not clear that Lilith had the time to phone the police after Stan left the bedroom.

So maybe the siren is indeed in Stan’s head. Or if it’s objectively in the story world, then maybe it’s just a coincidence. (Chicago has plenty of sirens.) In this case, Lilith takes advantage of the siren to weaken Stan’s grip even more. A further complication: The siren cuts off as Stan flees, but there’s no indication that the cops have arrived outside. And in another oddity, we see Lilith turn slightly toward the camera when she denies hearing the sound. Is this a mark of evasion, like blinking?

In sum: The siren is either subjective or it’s objective. If it’s subjective, it’s at variance with most subjective sound of the period in not being signaled clearly as such. If it’s objective, it’s either the result of somebody calling the cops from offscreen, or it’s just coincidental.

Which is it? Usually a Forties film is pretty explicit when we’re in a character’s head, if only in retrospect (e.g., the staircase “death” in Possessed, 1947). Nightmare Alley seems to fudge things here.

When being a geek isn’t chic

Am I over-thinking this? The commentators on the Eureka! DVD, noir experts Alain Silver and James Ursini, puzzle over the siren too. I think that when Lilith denies hearing it, most viewers feel a bump: after all, we hear it too. But soon, I think, most of us take it as a real siren and assume that Lilith seizes on it as another way to convince Stan he’s breaking down. As for Jane, we just forget about her.

Look at the overall film, though, and the subjectivity possibility gains a curious strength. The siren can be taken as part of a peculiar pattern running through the film. To show you what I mean, I need to rehash a fairly complicated plot. Bear with me.

Stan Carlisle, an ambitious carnival worker, is conducting an affair with Zeena, the fortune-teller, while her partner Pete sinks into alcoholism. Stan accidentally kills Pete by giving him a bottle of wood alcohol instead of moonshine. Partnering with Zeena, Stan masters a code system for a mind-reading act. Soon he has left Zeena behind and married the carnival entertainer Molly, who becomes his confederate in a ritzier nightclub mentalist act. But Stan is plagued by memories of Pete’s death. He visits a psychologist, Lilith, to whom he tells his guilt feelings.

Stan conceives a grand scheme to turn faith healer, using his skills at illusion and fake spiritualism. (“The spook racket: I was made for it.”) He manages to deceive the rich Ezra Grindle, who asks to see his deceased lover. The scheme, in which Molly impersonates a spirit, fails and Stan has to flee, hoping to take with him the money he’s already wormed out of Grindle. Lilith blocks that in the scene I’ve excerpted.

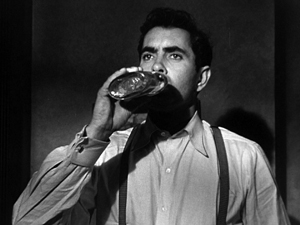

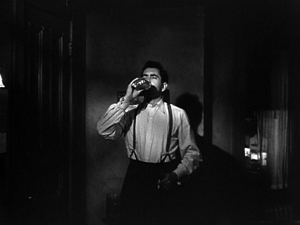

Stan leaves Molly and begins to spiral downward into drunkenness. By the film’s end he’s ready to take on the job of the geek, the subhuman carnival freak who bites heads off chickens. Originally Stan had despised the geek, but now, in order to be guaranteed a bottle a day, he declares: “I was made for it.” Only Molly’s tender concern holds out hope Stan might claw his way back.

I said the plot was complicated, but it rests on a set of fairly simple substitutions. The opening situation gives us two couples, Zeena and Pete, Molly and the strong man Bruno. Initially Stan was odd man out, paralleled by the geek (also on the fringes of the action). Stan replaces Pete as first Zeena’s lover and then her stage partner. But once Stan knows the mentalist codes, he can replace Zeena with Molly, whom Bruno surrenders. Later Zeena and Bruno will form a couple. In Stan’s rise, Molly gets replaced by Lilith, his partner in crime, if not in romance. When Stan’s swindle fails, he goes on the run, alone again. Pete was established as one step up from geekdom; without Molly, he said, he’d be a geek. Now Stan becomes the new Pete. Drinking around a campfire with bums, he even repeats Pete’s cold-reading spiel word for word and gesture for gesture, with a bottle of booze as the crystal ball.

Stan finally sinks to the bottom, willing to serve as a carnival geek for the standard bottle a day. Molly now plays Zeena to the new Pete.

The pattern of sound leading up to the siren scene centers on the geek. In the crucial scene in which Stan gives Pete the rubbing alcohol, the geek’s cries punctuate the action as he dashes around in the distance; like Pete, he needs his daily bottle. But we hear those cries three more times later, when the action has left the carnival. The cries are displaced from their original source, and more insistent on each appearance.

The first time, they’re very faint. Zeena and Bruno have called on Stan and Molly in their nightclub dressing room. Zeena has brought out her Tarot deck and seeing Stan’s future she warns him not to try the big thing he’s contemplating. (It’s the fleecing of the grieving Grindle.) Worse, her cards bring up the Hanged Man, the same card that Zeena turned up for Pete. Once the association with Pete has returned, it’s hard to exorcise.

Angry, Stan forces Zeena and Bruno out, and as he stands at the door, with the music rising, we can hear the distant cries of the geek. In the next scene, the association with Pete is strengthened. Stan is getting a massage and the smell of the rubbing alcohol reminds him of the night of Pete’s death. Now, more strongly, we hear the geek.

The motif-cluster is Pete’s death/Hanged Man/rubbing alcohol/the geek. This is brought back again, most obviously, when on his downward path Stan is holed up in a hotel room and instead of eating starts to guzzle a bottle of gin.

The compulsive drinking, along with Stan’s disheveled life, marks another stage in his conversion into Pete, and the geek’s cries are heard most plaintively now.

So what do we make of the geek’s cries in these scenes? If we take them as subjective, as Stan’s auditory flashbacks or imaginings, then the siren moment gathers a new force. If we’ve had access to Stan’s mental soundscape earlier, maybe we have it again when he “hears” the police coming. After several instances of subjective sound, we’re more prepared to take the siren as subjective too—and to wonder a bit about it even after we’ve concluded that it’s probably objectively in the scene.

That feint would be an interesting storytelling maneuver in itself. Yet other factors complicate things.

The geek goes Greek

In 1940s movies, there’s plenty of subjective sound. Often we understand that a sound is subjective by virtue of its acoustic quality; it may be given extra reverb or distorted in other ways. We also take it as subjective because the sound clearly isn’t coming from the scene. We often remember it from prior scenes and so treat it as an auditory flashback. But there are visual cues for subjective sound too. The two primary ones are a close view of the character whose mind we’re in, and an expression on the character’s face that indicates some intense feeling.

In The Fallen Sparrow (1943), Kit recalls his months in a Spanish prison chiefly through the scraping limp of one of his captors passing in the hall. When we’re given access to that acoustic memory, we get fairly close shots of Kit’s agitation.

In an interesting parallel to Nightmare Alley, when Kit is with Whitney, he thinks he hears the scraping footbeat again.

It might be a genuine offscreen sound, since we have reason to believe that his torturer has followed him to New York. (In the climax, the sound will be actual, not imaginary.) But at this point Whitney says she doesn’t hear the noise, and neither do we. This indicates that Kit is imagining it. The filmmakers faced a problem comparable to that in the Nightmare Alley scene. If the sound had played for us as well as for Kit, and Whitney said she didn’t hear it, the options are three: we’re in Kit’s head, though she isn’t; it’s real and she truly didn’t hear it; or it’s real and she’s lying (as Lilith may be). We couldn’t be absolutely sure we were in Kit’s head if the sound had been included, but when it’s not on the track, we know he’s hallucinating.

There are several norms to consider here. First, typically the close shot is timed to coincide with the subjective sound, indicating that the character registers the sound when we do. That happens in The Fallen Sparrow, but not in Nightmare Alley. We notice the siren before Stan does, which suggests that it’s objective.

Second, the shot isolating the character favors our taking a sound as subjective. But when another character is in the shot, it’s harder to construe as subjective. Accordingly, in The Fallen Sparrow, the shot that includes both Kit and Whitney inclines the filmmakers to treat the shot as objective and the sound as purely private, as inaudible to us as it is to her. In Nightmare Alley, the siren does indeed start over a close-up of Stan, but it continues over a reverse-shot of Lilith and soon enough, over a shot of the two of them.

Finally, our sense of subjectivity depends partly on the intrinsic norm each movie sets up. In The Fallen Sparrow the scraping footstep takes its place in long stretches of inner monologue which vocalize Kit’s thoughts. Because we’ve had intimate access to his mind, we’re likely to accept the footstep we hear as subjective as well. But Nightmare Alley doesn’t include inner monologues. We never access Stan’s stream of thought, so the geek cries are the only moments we might be plunging into his mind–at least, until (perhaps) the siren scene.

The siren scene hangs uncertainly between subjectivity and objectivity, tilting toward objectivity but also casting some doubts on it. What about the geek sounds? They’re even more complicated. They seem to hang between subjectivity and–well, something else.

Take the first instance. Stan is at the doorway and the camera tracks in to him as the musical score emerges. The geek noises slip in, and Stan pauses, as if reflecting.

That seems like a fairly standard cue for subjectivity: Stan has associated the Tarot cards and Pete’s death with the geek’s cries. Because of the faintness of the noise (some people seem not to notice it, as if the score nearly drowns it out), the narration might even be hinting that Stan’s memory of the night of Pete’s death is barely conscious.

In the light of the later occurrences, I’d propose another possibility. Given that we’ve never been in Stan’s head before, the sound might be more addressed to us than to him, reminding us of an association he doesn’t sense at all. This moment might almost be the film’s way of taking us aside and flagging a motif that will develop later–and in ambiguous ways.

In the rubdown scene, we see Stan, anxiously reacting to the smell of alcohol, in a fairly close view as the geek’s cries are heard.

In great anxiety, he leaps off the rubbing table. But perhaps he’s reacting just to the smell of alcohol, not to his memory of the geek. Again, the geek sounds are smoothly merged with a burst in the musical score.

Most characters who hear imaginary sounds report them to the people around them. But Stan hasn’t said anything, as far as we know, to Molly about twice hearing the geek. When Stan tells Lilith of the two earlier scenes during his therapy session, he mentions only being disturbed by Zeena and the cards, and the way the alcohol reminded him of Pete.

He doesn’t mention hearing the geek’s cries. So again we might ask if these cries aren’t subjective but rather something like a nondiegetic score–the soundtrack reminding us of something Stan isn’t remembering.

The last recall of the geek’s cries is presented while Stan is gulping gin. The noise starts in a medium shot before the camera retreats to a distant view.

If the cries make him feel tormented, he doesn’t give much sign of it. And if we were supposed to penetrate his mind, where the geek noises might reside, the camera would typically track in more tightly (as it does in The Fallen Sparrow). Instead, it withdraws, again raising the possibility that the geek’s shrieks are a commentary, not a recollection. Perhaps the cries are more like the Greek chorus warning us of an outcome to which the protagonist is oblivious.

What are we left with? Mixed signals, I think. The geek’s cries and the police siren hover in a space that many films worked within but seldom treated so freely. The cries can be taken as subjective, but they lack robust cues for that function. In other respects, they suggest expressive commentary. As the alcohol reminds Stan of Pete’s death, the cries do the same for us, while prophesying Stan’s fate. And the siren, while probably objective, makes us hesitate partly because we’re not sure the police have been called and partly because we’ve had ambivalent sound cues earlier. For a moment it might seem to be, as Lilith says, Stan’s first full-blown hallucination.

The continuity script for Nightmare Alley duly notes the siren’s sound, and the geek’s cries are noted in the scene of Pete’s death. But there’s no mention of geek cries in any of the three scenes I’ve considered. Perhaps director Edmund Goulding shot the film without planning to include the geek sounds at all. Perhaps they were added in postproduction. Someone late in the production process may have decided to anticipate Stan’s final degradation through ever more vivid echoes of the poisoning scene. Nightmare Alley would become an example of innovation by last-minute intervention.

Usually a 1940s film respects the distinctions, the either/or options, that are offered by the era’s stylistic menu. Accordingly, a sound is clearly objective or clearly subjective. But sometimes a film oscillates between the choices, or blurs the distinctions among them. We’re most familiar with this slipperiness when music shifts between being diegetic (sourced in the story space) and being nondiegetic (added to the story world “from outside”). This sort of looseness can be found elsewhere in 1940s storytelling. A film may start with one narrator and end with another, or none, or an uncertainly identified one. A flashback may never close, or loop back to its beginning without returning to the frame story. The outliers coax us to study how the ordinary cases work and note how much we take their conventions for granted.

We can learn as much about storytelling strategies from the ambivalent films as from the trim and polished ones. And in a movie called Nightmare Alley, we can’t regret that the haunting wail of the geek wafts through it as both a reminder of death and an anticipation of destiny. Its shape-shifting sound fits a movie that wants to unsettle us.

Fussbudget film analysis: I was made for it.

The continuity script for Nightmare Alley is available as a pdf file on the Eureka! DVD of the film.

Lee Garmes’ remark about explicit entrances and exits is quoted in Charles Higham, Hollywood Cameramen (Thames & Hudson, 70), 49-50. For background on the making of the film see Matthew Kennedy, Edmund Goulding’s Dark Victory: Hollywood’s Genius Bad Boy (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 241-252. There’s a detailed and intriguing psychoanalytic interpretation of the film at Randomaniac.

Actually, the scene in The Fallen Sparrow is a little more complicated than I indicate here, but I didn’t want to get into the weeds. The essential point holds, though: when one character thinks that a sound is veridical, and another character is present but doesn’t hear it, the filmic narration can confirm or disconfirm or ambiguate the source of the sound.

Thanks to conversations with Kristin, Jeff Smith, and Jim Healy about the film. Woody Haut’s lengthy discussion of the film for the Eureka! disc is reprinted on his website.

I discuss extrinsic and intrinsic norms of narration in Chapters 4 and 8 of Narration in the Fiction Film.

For other example of fruitful anomalies in the period, see “Innovation by accident,” “Twice-Told Tales: Mildred Pierce,” and the Laura discussion in “Dead Man Talking.”

You and me and every frog we know

Frog TV (2014, N. Joe Myers).

DB here:

Be patient, the frogs are coming. But first, a bit of film theory.

Movies in code

Once many film scholars were captivated by the idea that our responses to a movie were coded, we might say, all the way down.

Here, code means something like a way of assigning meaning that is both arbitrary and relative to time and place. The code is arbitrary in that it might just as easily have been otherwise. A code is relative because in different circumstances it might vary.

One prototype for the early semiologists was the code regulating traffic. In a traffic light, there is no natural or necessary connection between green and “Go!” or red and “Stop!” We’ve just agreed on these meanings. We could have assigned red to “Go!” and green to “Stop!” And indeed other cultures might do just that. A gesture may mean something friendly in one culture and something naughty in another.

The presumption is that because a code is both arbitrary and relative, it has to be learned. You need to live in a culture to understand the traffic code and the code of gestures. Through either observation or training (such as learning the codes of written language) you master the codes of your culture.

Clearly, movies include many codes. A film can show us traffic lights or hand gestures. Films include language as well, which is coded to a high degree. The crucial question is: How much in our responses to film is coded?

Almost everything, some said. There was a wing of semiology ca. 1970 that suggested that both what’s represented in film and the ways things are represented are arbitrary and culturally variable in the extreme. Some theorists suggested that just recognizing an object in a shot relies not on natural perception but rather on a code. Indeed, the argument was made that “natural” perception is itself coded. A favorite corollary of this was that language was such a powerful code that it reshaped perception. Put bluntly, if your culture’s language doesn’t distinguish red from green, you won’t see the traffic light’s top and bottom lamps as different colors.

I resemble that remark; or do I?

Surely, somebody will say, many film images resemble the things they portray. A shot of a man and a woman looks, in certain relevant respects, like a man and a woman. We’re able to recognize them as such. Yet 70s semiology held that there was nothing natural about this. The image-object resemblance, often called “analogy,” and “iconicity,” was considered to be coded.

Here, for instance, is Umberto Eco in 1967:

We know that it is necessary to be trained to recognize the photographic image. . . . Even if there is a causal link with the real phenomena, the graphic images formed can be considered as wholly arbitrary.

Christian Metz brings out the cultural variability of recognition in a 1970 essay:

The apprehension of a resemblance implies an entire construction whose modalities vary notably down through history, or from one society to another. In this sense the analogy is, itself, codified.

Here is Dudley Andrew commenting on this line of thought in 1984:

The discovery that resemblance is coded and therefore learned was a tremendous and hard-won victory for semiotics over those upholding a notion of naive perception in cinema.

The semiological tradition pointed out, correctly I believe, that the parallel between the image and the thing it represents lies not in some relation between the two but in the comparable ways in which we understand each one. But can this process be considered both arbitrary and relative?

Can we, for instance, imagine a culture in which recognition was fundamentally arbitrary—where a picture of a bunch of bananas depicts, by cultural fiat, a clutch of cherries? More exactly, where a picture of a bunch of bananas is seen as a clutch of cherries?

We can imagine a very capricious filmmaker who set up a code with an introductory credit:

Every time I show you a shot of bananas, see cherries.

But you couldn’t see cherries. At best, the result would involve imagination, not perception. Even cooperative spectators would recognize the bananas as bananas, though they would go on to think of cherries.

The distinction between perception and thought seems to have been blurred in semiological theory. Perhaps the 70s arguments traded on the various meanings of “perception”, such as “I perceive that he’s unhappy today” or “I want to change your perception of Rosicrucianism.” The same would go for various senses of “recognition”: “I recognize the father’s face in the son,” “He had aged so much I didn’t recognize him.” These senses of the word bring in matters of conception and attitude, not just visual input.

Perception and evolution

Not that perception is easy to define. When the semiologists were writing, they may have been influenced by psychological theories that assigned a big role to concepts in perception—“top-down” models that claimed perception to be “cognitively penetrable.” It’s fair to say that there’s now good evidence that the perceptual activities involved in visual recognition are largely fast, automatic, fairly dumb, and cognitively impenetrable.

Another error, it seems to me, was also the product of the period: the ignoral of evolution. The 1970s advocates of sociobiology seem to have been simply ignored, perhaps because they seemed to be naïvely attempting to see culture as nature. Yet I think that J. J. Gibson was right (also in the 1970s) in proposing that evolutionary theories could help explain why perceptual recognition is so swift and efficient.

Creatures evolved in an environment that selected for accurate perception, including very very very fast recognition of predators, prey, and mates. Evolution, we might say, provided long-term survival training in recognition, weeding out any creatures who didn’t register salient features of their world. A hominid who needed explicit teaching to recognize a tiger wouldn’t last as long as one who came to the task with senses pre-tuned. As with learning spoken language, all that would be needed is some exposure to the regularities of the ancestral environment. The baby born into our world is bombarded with redundant information that is non-arbitrary and non-relative; she quickly grasps that a face is more informative than a knee. It will take her quite a bit more time, along with some tutelage, to learn traffic signals and even more to learn to read.

Cinema taps some of our most fundamental capacities. Film images aren’t reality, but they present certain salient triggers for us to recognize what they represent. Indeed, the very perception of motion in movies is an illusion—a glitch in our visual system that cannot be arbitrary or culturally relative. Nobody in any time or place sees movies for what they are, a succession of still images. There are enough cues for movement to fool everybody’s visual system. And films preserve enough other features of the world to trigger automatic recognition processes. Perceptual recognition of something in the image is on the whole neither arbitrary nor culturally variable.

The likeliest conclusion is that we share with other creatures some native propensities which, given the right early exposure to the physical and social world, will be exercised in comparable ways. Of course there are differences. Minnows can’t enjoy Matisse, and we can’t smell as well as dogs can. Still, sensory systems overlap among many species.

So consider the frogs of the field: they toil not, neither do they spin.

Frogs like the front row too

We know quite a bit about how frogs see the world. A classic paper in animal neurology, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” was crucial in suggesting the highly specialized nature of nerve fibers feeding information to the visual system. Those data streams—about edges, movement, and variable illumination—get reintegrated, but not necessarily thanks to high-level mental activity. “Early vision,” in frogs and in us, involves not some some brainy entity interpreting the image on the retina but rather several specialized, quite stupid systems that pool information before thought ever enters the picture. No codes necessary. What came to be called “distributed processing” does a large share of the job.

Though untrained in the codes of our culture, these frogs appear to recognize what matters to them, even on the mini-movie screen. (Sorry the video embed no longer works.)

If pigeons can quickly learn to interpret human faces in pictures, and female jumping spiders react to video images of males as if they were real, we shouldn’t be surprised that frogs can respond very—ah—actively on first exposure to movies showing things they really care about.

Of course a lot of our activity isn’t as data-driven and mandatory as recognition. Higher-level concepts do all sorts of work when we watch movies, from understanding who the protagonist is to grasping a film’s theme or point. And of course all manner of conventions in films require sophisticated cultural knowledge. My point is just that some aspects of our response are very basic. I hazard that our responses to cinema mix together all kinds of skills, abilities, biases, and proclivities. A movie is a package of appeals, a buffet with something for all our visual and auditory appetites.

First, thanks must go to N. Joe Myers, who posted this neat experiment in natural perception a year ago. (Has the filmmaker tried it with an iPad or a computer monitor that would make the worms look huge? Would that induce large-scale frog panic?) For vastly more frog-related information, go to N. Joe’s page here.

Thanks also to Darlene Bordwell, who called the piece to my attention, and Barb Anderson who pointed me to the spider studies. The illustrations are of course from Chuck Jones’ Warner Bros. cartoon One Froggy Evening (1955).

My quotations are from Umberto Eco, “Articulations of the Cinematic Code,” and Christian Metz, “On the Notion of Cinematographic Language,” both in in Movies and Methods, ed. Bill Nichols (University of California Press, 1976), 594 and 584; and Dudley Andrew, Concepts in Film Theory (Oxford University Press, 1984), 25. See also Metz, “Au-delà de l’analogie, l’image (1969),” Essais sur la signification au cinéma, vol. II (Klincksieck, 1972): “Resemblance itself is codified, because it makes appeal to a judgment of resemblance: the judgment of an image’s degree of resemblance will vary according to the time and place” (154).

J. J. Gibson’s writings mounted a strong case for what he called “direct perception” in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Houghton Mifflin, 1979). His ideas were developed by Claire F. Michaels and Claudia Carello in Direct Perception (Prentice-Hall, 1981) and, more critically, by James Cutting in Perception with an Eye for Motion (MIT Press, 1986); pdf. Joseph Anderson’s The Reality of Illusion: An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Film Theory (University of Southern Illinois Press, 1998) is the trailblazing application of Gibson’s ideas to cinema. More generally, Paul Messaris’ Visual Literacy: Image, Mind and Reality (Westview, 1994) reviews the empirical findings that show virtually no cultural variability in perceiving line drawings and photographic images as depictions of recognizable persons, places, and things.

At some point in discussions of the cultural variability of perception, someone is likely to mention Eskimo cultures’ purported range of words for snow. But this is a long-standing error. See Geoffrey K. Pullum’s The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax and Other Irreverent Essays on the Study of Language (University of Chicago Press, 1991) and John H. McWhorter’s The Language Hoax: Why the World Looks the Same in Any Language (Oxford, 2014).

What happened to these 1970s beliefs about the film image’s coded nature? It seems to me that when semiology as a research perspective waned, academics mostly stopped talking about the issue of resemblance and recognition. Researchers retained a general sense that films are coded, but they concentrated on less controversial conventions, like social stereotyping, representations of power, and so on. I’ve been told that the level of perception is merely a matter of “physiology” (wrong word) and thus of no consequence for the important issues that scholars should be studying. But of course filmmakers shape our response chiefly by controlling our perception, and if we want a comprehensive account of how films work and work on us, we can’t ignore this level of the viewer’s activity. I consider this problem in the title essay of Poetics of Cinema.

For a more developed argument about how films bundle a range of appeals, from sensory triggors to high-level concepts, see my essay, “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision” in Poetics of Cinema. Online, I discuss these matters here and here and here (under “Representational Relativism,” which involves not frogs but our ancient ancestors).

P.S. 21 September 2015: Apes appear to remember episodes after watching movies. Thanks to Bill Evans.

One Froggy Evening.

Vertov, sound technology, and 3D: Recent Blu-ray releases

The Man with a Movie Camera.

Kristin here:

Every now and then we accumulate a few new DVDs and Blu-ray discs and write up a summary of each. This entry is the first time when all the discs discussed are Blu-ray. In fact, none of these releases is available in the DVD format.

Vertov and more Vertov

Soviet director Dziga Vertov is known primarily for The Man with a Movie Camera (1929), one of the most revered silent films. It is a documentary, an experimental film, a city symphony, and a witness to Soviet society in the late 1920s, all in one. Flicker Alley has done great service to silent Soviet cinema with its Landmarks of Early Soviet Cinema and the serial Miss Mend by Boris Barnet and Fedor Ozep. Now it has brought out a Blu-ray disc of a remarkable 2014 restoration of The Man with the Movie Camera.

This version is based largely on a print struck from the original negative and left by Vertov with the Filmliga of Amsterdam, an early cine-club. It subsequently passed to the Nederlands Filmmuseum. The restoration added clips culled from other archival prints to fill in gaps in this copy, producing an edition that will be a revelation to many who are used to the scratchy, contrasty, and cropped prints that have circulated for decades.

For one thing, seeing that missing left side of the frame makes a big difference. A booklet included with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

Yet Flicker Alley has been too modest in emphasizing this as a release simply of The Man with a Movie Camera. The full title of the release is “Dziga Vertov: The Man with the Movie Camera and other Newly-Restored Works.” Yet the “Other Newly-Restored Works,” featured in very small print on the cover, are hardly incidental. They include features that many researchers and cinephiles have long wished that they could view in good prints–or any prints at all.

These other works include most of Vertov’s famous features of the 1920s and early 1930s: Kino-Eye (1924), his first feature; Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1931), his first sound feature; and Three Songs about Lenin (1934), a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the death of Lenin.

I don’t think any of these films is as important as The Man with the Movie Camera. For me, Kino-Eye is the most charming, with candid depictions of peasant festivals and the like. It was Vertov’s first opportunity to stretch his ambitions after years of work in newsreels and documentaries. It has a spontaneity that perhaps disappeared in the later features.

The disc includes an informative booklet that discusses both the films and their restorations. As an extra, there is the 1925 Kino-Pravda newsreel episode that Vertov made to commemorate the first anniversary of Lenin’s death. It incorporates rare newsreel footage of Lenin, cutting it together in ways that look like modern gifs.

The visual quality is inevitably variable, with the earlier films looking contrasty, but these are no doubt the best versions that we are likely ever to have. This Man with a Movie Camera supersedes the one from the BFI (in the UK) and from Kino (in the USA), though many will want to have the latter for its lovely score by Michael Nyman. The Flicker Alley version has a very different, but highly appropriate, score by the Alloy Orchestra.

Not all of Vertov’s early features are included. For those who want more, Edition Filmmuseum’s release of A Sixth Part of the World (1926), The Eleventh Year (1928), both with a Michael Nyman score, and one shorter film plus a documentary on Vertov, remains a necessity.

3D curiosities

Flicker Alley has also developed a specialty in releasing DVDs and Blu-rays exploring film formats. The company has paid particular attention to Cinerama (This Is Cinerama, Cinerama Holiday, South Seas Adventure, Windjammer, Seven Wonders of the World, and Search for Paradise). Now, in celebration of the centennial of 3D exhibition , it branches out into 3D with 3-D Rarities, described as “A Collection of 22  Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

This BD brings together a thoroughly heterogeneous collection of short items, assembled into two programs. The first, “The Dawn of Stereoscopic Cinematography,” covers the years from 1922 to 1952, with short films made outside mainstream Hollywood. Some test footage by Edwin S. Porter and William E. Waddell shown in 1915 no longer survives, so the earliest films on the program are “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” (1922-23), including Thru’ the Trees, a travelogue of Washington, D. C. featuring shots of famous buildings framed primarily by foreground tree branches to create planes in depth.

The items that follow range from promotional films to animated shorts to a burlesque comedy featuring two fairly tame striptease segments and two fairly unfunny comedians. A  promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

For many the highlights of this first program will be four shorts from the National Film Board of Canada, two of them by Norman McLaren. The first, Now Is the Time (1951), uses the filmmaker’s familiar drawn-on-film style (right), while the second, Around Is Around (1951), employs an oscilloscope to create more abstract patterns.

Films by two of McLaren’s colleagues are also included: O Canada (1952) by Evelyn Lambart and Twirligig (1952) by Gretta Ekman. These films are among the only ones on the whole program where objects are not thrust or thrown “out” at the audience.

The first program ends with an advertisement, Bolex Stereo (1952), a camera which supposedly was going to bring 16mm 3D home-movies into people’s living rooms. The complicated technology demonstrated shows why the idea did not catch on.

The second program, “Hollywood Enters the Third-Dimension,” consists mainly of trailers interspersed with a few shorts. The trailers include It Came from Outer Space and Miss Sadie Thompson (both 1953). One fascinating film is Rocky Marciano vs. Jersey Joe Walcott (1953), and I say this as one who has no interest in boxing. This 16-minute black-and-white film starts at the training camps of the two opponents and moves on to the match itself, in which Marciano famously knocked out Walcott in less than two minutes. The in-ring controversy over the call occupies the last part of the film, giving the whole thing a distinct dramatic shape. Multiple-camera filming and 3D add visual interest.

Stardust in Your Eyes (1953), a comedy short starring comic and impersonator Slick Slavin (aka Slaven in the credits), is said in the program notes to have been “a big hit at 3-D festivals. Judge for yourselves, but I advise keeping a finger on the next-chapter button for this one.

Few of these shorts can be said to be important classics of the 3D repertoire, but overall one gains a sense of the surprising range of films made with the process. One also learns that thrusting guns, spears, swords, and even sling-shots toward the audience, as well as throwing stones and other missiles at them, never grow old as far as the makers of these films are concerned. We have a pistol aimed at us in one of the “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” from 1922 (below left) and a rifle in the trailer for Hannah Lee (1953, right).

At least we now have the 3D version of Mad Max: Fury Road to recharge this particular visual trope in highly original ways.

Sound marches on

Way back in 2008, when this blog was a mere two years old, I reported on the first volume of a two-disc set of DVDs inaugurating the highly ambitious project, A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures. That first volume covered the period to 1932. This one is entitled “The Sound of Movies: 1933-1975.” There was of course a lot more recorded sound in that period, and the new set stretches to four Blu-ray discs, for a total of over twelve hours of running time.

I can’t claim to have watched all those hours, but every section I sampled boasted extraordinary amounts of information. Robert Gitt, who originated the project with a 1992 lecture, again narrates. The coverage includes a huge number of rare diagrams, photographs, documents, and demo reels. In addition, many of the chapters add clips from films that contained the most innovative sound techniques of their day. The Garden of Allah, Okhlahoma!, Medium Cool, and many other titles are excerpted in superb copies.

The set as a whole is a gold mine for specialist researchers and technology buffs. The discs include long and detailed passages on such topics as push-pull recording and noise reduction, the latter a crucial challenge to the sound-recording industry for decades. Teachers who searched assiduously could find many clips suitable for classroom use.

A fair amount of the material ought to be interesting to nonspecialists too. For example, the third disc includes a history of early multi-channel and directional sound. The section on early stereophonic systems is fascinating, with its coverage of Leopold Stokowski’s participation in the two most important early films to introduce this new technology to a popular audience: 100 Men and a Girl (1937) and Fantasia (1940). We get generous clips from each. From 100 Men and a Girl, we see most of the famous scene in which an orchestra plays on different levels of Stokowski’s house and multiple channels allow sonic “close-ups” of each type of instrument over close views of that section of the orchestra:

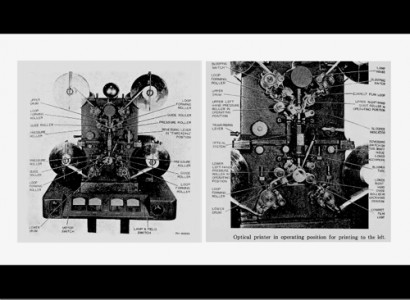

A thorough history of Fantasia includes the image below, typical of the sorts of material The Century of Sound presents: the Fantasound optical printer invented in order to print the multiple optical tracks used for the film’s stereo.

And someone obviously could not resist including a goodly dose of the short dances from the Nutcracker Suite section of the film (see bottom).

The Century of Sound is not for sale commercially. It “is available free of charge to educational, archival and research institutions and to qualified individual educators, researchers and scholars as a not-for-profit educational resource.” There is a modest fee for shipping. For information on ordering, write to CenturyofSound@cinema.ucla.edu.

Flicker Alley’s release of This Is Cinerama provoked David to a survey of Cinerama aesthetics in an earlier entry.

Fantasia.

Sometimes a reframing…

Side Street (1949).

DB here:

…just knocks you out.

“It can only be fully recommended to those who have a deep and morbid interest in crime.” Snooty judgments like this made Bosley Crowther the critical joke of generations. Today film lovers wear their deep and morbid interest in crime as a badge of honor. Especially when the crime is covered by Anthony Mann.

In Side Street (1949), Joe Norson has lost his business and works part-time as a postman while he and his wife await their first child. Having come back from war and wanting to give Ellen a good life, Joe is tempted to steal money he’s seen lying around the office of a crooked attorney. He grabs a folder containing what he thinks is a couple of hundred dollars; instead, it holds $30,000 of blackmail money. The woman who chiseled the money out of a businessman turns up dead, and the police are investigating. When Joe naively loses the money and sets out to recover it, he’s drawn into the murder, tracked by the gang, and targeted as a prime suspect by the police.

Variety and Crowther chided the screenwriters for a sketchy plot, and the complaint is somewhat fair. Joe is an unusually weak protagonist. He botches both his theft and his cover-up, leaving a trail that’s easy for the killer and the cops to trace. Because Joe is fairly passive and on the run, and he has to follow his clues in a fairly linear manner, and his schemes to fight back come to almost nothing, the action is filled out by scenes of the gang and the police tracking him.

What partly compensates for the plot’s problems is the bold location shooting. As part of the semi-documentary trend of the period (the film opens and closes with worldly-wise voice-over narration from the Homicide Captain), Side Street presents itself as a story rooted in urban reality. And indeed it is a triumph of location shooting. The characters visit a bank, Greenwich Village, Bellevue Hospital, and many neighborhoods. The final chase, with Joe trapped in a taxi with the killer and pursued by three cop cars, is a tour de force of geometrical shot designs that make city canyons part of the drama.

Mann has long been praised for integrating the forces of nature into the action of his Westerns, but this film shows his flair for cityscapes too.

Given the constraints of location filming, the freedom of Mann’s camera is all the more arresting. This time he’s not working with John Alton, the cinematographer most in tune with his baroque sense of light and framing. But Mann still gets punchy results from ace DP Joseph Ruttenberg. There is nothing quite so staggering as Alton’s framing of Claire Trevor and the cabin clock in Raw Deal, let alone the Grand Guignol imagery of Reign of Terror, but Ruttenberg does give us plenty of nicely dense compositions, exploiting the verticals and apertures available on location. There’s also a neatly discreet shot of a revolver peeking out from behind a door in distant long-shot; the shadow supplies the telltale shape.

Mann is a post-Kane filmmaker. Like nearly every Forties director of dramas, he learned from Toland and Welles that it’s fun to shove the action into the viewer’s face. The high angles of the city are counterbalanced by steep, low setups both inside and outside. Mann never met a “Russian angle,” or a ceiling, he didn’t like.

When the lens is more or less straight on, the frame can be tight and actors’ heads are packed into the frame like cantaloupes in a supermarket display.

In motion, the camera isn’t safe. Actors rush past the lens or thrust themselves straight at it.

When Joe flings himself out of a car, prepare to find yourself in the middle of traffic, with a truck rushing at you (a stunt done in real space, not against a back-projection).

Yet even studio-shot back-projections retain vigorous, immersive depth.

Mann’s visual dynamism, complete with aggressive foreground and distant depth, hits a high point in the dialogue-free scene that’s the topic of today’s sermonette. Joe hasn’t planned to steal the money, but circumstances lure him on. The lawyer’s out of his office, and the door has been left ajar. Joe earlier saw the money put into a file drawer, and as Joe prepares to slide the mail under the door, the cabinet stands temptingly in the foreground.

He impulsively heads for the cabinet, pauses before it, and then—thanks to an abrasive cut—grabs the handle violently. The drawer is locked. He recovers himself, almost grateful that he’s blocked, and he lurches out the door. No theft today, apparently.

Outside, Joe seems to be going on his way, but the long shot shows a barrier, like a railing in the foreground. It seems about as innocuous as the car hood we saw when Joe went in the building.

As Joe approaches, the camera tilts up to follow him and he stops, staring. He’s framed before what’s now revealed as a fire axe.

Another director—Hitchcock, perhaps—would have handled this with a medium-shot of Joe leaving and looking off, followed by an optical POV shot of the axe. Or you could show him leaving in the foreground, with the axe mounted in the distance; he glances back, sees it, and decides to go fetch it.

By contrast, Mann’s approach yields a sharp one-two snap: Joe approaches/ he stops. We see the axe, but almost by accident; the reframing is just following Joe’s movement. And we don’t need to see any more of the thing but its distinctive shape—its pure axe-ness given in silhouette. Rudolf Arnheim, who always advocated pictorial simplicity, would be pleased.

After a beat, in an abrupt cut, Joe grabs the thing.

He lunges down the corridor back to the office and starts to break into the cabinet. Now his violent adventure begins.

Crime I’m not so sure of, but with bodacious filmmaking like this, who wouldn’t acquire a deep and morbid interest in cinema?

It’s been too long since our last “Sometimes…” entry. For the others see: “Sometimes a shot . . .” and “Sometimes two shots . . .” and “Sometimes a jump cut…”

Bosley Crowther’s review of Side Street is “The Screen: New Crime Story,” New York Times (24 March 1950), p. 29.The Variety reviews, more or less identical, are in Daily Variety (22 December 1949), p. 3, and Variety (28 December 1949), p. 6. The Times covers the shooting of the climactic chase in “Taxi Acrobatics in Wall Street” (8 May 1949), X5.

For more on the postwar cinema’s love affair with vigorous depth staging and depth of field, see this entry on Bergman and Antonioni, this entry on Toland and depth of field, this entry on Manny Farber’s objections to Huston, this entry on dense staging, and this entry on Wyler’s staging in The Little Foxes. For much more see Parts Three and Four of our Film History: An Introduction, Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style.

Side Street.