Archive for August 2013

Is there a blog in this class? 2013

Rebel without a Cause (1955).

KT here:

It’s time for our annual scan of the past year’s entries, pointing particularly to ones that might be useful to teachers and students using Film Art: An Introduction. For occasional readers of the blog, this post might be useful in catching up on items you might have missed.

This year we’ve added four video essays and lectures to our site. These have entailed a lot of effort, but David has enjoyed making them as free complements to the briefer, walled-garden video essays accompanying our latest edition of Film Art.

We’re also delighted to include some entries based around encounters we have had with filmmakers (some of whom we met as a result of our blog) and two contributions from guest experts. Looking back, we are as usual surprised at how much material has accumulated in one year. The summer’s new movies may on the whole have disappointed, but obviously there are a lot of other interesting topics to explore outside the multiplex.

For earlier blog-roundups, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012.

I’ll go through Film Art chapter by chapter, suggesting relevant entries for each, and end with a couple of entries on new DVDs that teachers might want to add to their personal or departmental libraries.

Chapter 1 Film Art and Filmmaking

Last year, David’s “Pandora’s Digital Box” series dealt with the transition from film-based to digital-based production and distribution. (That series was revised and expanded into a book.) The original series is updated in “Pandora’s Digital Box: End times.”

This year, David looked back on some historical formats. In “The wayward charms of Cinerama,” he reviewed Flicker Alley’s DVD release of This is Cinerama and took the occasion to analyze the peculiar perspective relations created by the triple-camera system. How the West Was Won and The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm receive some stylistic scrutiny.

Super 16mm is still a significant gauge for independent filmmaking, but regular 16mm as has largely been replaced by DVD and Blu-ray for classroom and film-buff viewing. David waxes nostalgic concerning the charms of 16mm and its importance in our own film-watching careers in “Sweet 16” and “16, still super.” For those too young to have seen 16mm on a screen, these recollections might make it a bit more vivid.

Nothing conveys the tangible work of film production like a visit to a working set. Our colleague James Udden, expert on Taiwanese cinema, had an opportunity to watch a major contemporary director in action and reports for us in “Master shots: On the set of Hou Hsiaeo-hsien’s THE ASSASSIN.”

Publicity is a big part of the distribution of a modern blockbuster. In “Jack and the Bean-counters,” I examine the missteps in the campaign for Jack the Giant-Slayer and talk about how the studios avoid cooperating with fans eager to provide valuable free online publicity for their favorite films.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

Films often use repetition in an obvious way to help us easily follow a story. But what about filmmakers who introduce more subtle similarities that challenge our memories? We examine two such films made in South Korea, In Another Country and Romance Joe, in “Memories are unmade by this.”

Repetition is also central to Mildred Pierce, where a murder that happens at the beginning of the film is seen again, with different shots and timings, near the end. We look at how the film fools us without our noticing it. The sequences are here:

“Twice-told tales: MILDRED PIERCE” analyzes the different functions and effects of the two sequences.

Art films and classics are not the only films with intriguing storytelling. “Clocked doing 50 in the Dead Zone” is an analysis of David Koepp’s Premium Rush as a short film that packs a lot of action and clever narrative tactics into its running time. That entry led to a meeting with Koepp and a follow-up entry on his approach as screenwriter and director. See the Chapter 8 section.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

Seeing some recent Asian films at the 2012 Vancouver International Film Festival led to “Stretching the shot,” some thoughts on functions for the long take.

A lot of the films we see in theaters today are made in anamorphic widescreen processes, and by now letterboxing for home-video is familiar to all. David has often lectured on the history and aesthetics of the first successful anamorphic process, CinemaScope. Now that PowerPoint lecture is available on his Vimeo site. See “Scoping things out: A new video lecture” for an introduction and link. (It’s about 53 minutes long, so perhaps something to assign your students to watch on their own.)

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to shot: Editing

“News! A video essay on constructive editing” introduces the additionof an analysis of editing in Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket to Vimeo. It’s about 12 minutes long, suitable for classroom use or assignment for students to watch outside of class. Our thanks to our friends at the Criterion Collection for their permission to use the excerpts from Pickpocket.

How much can a single cut reveal about the power of editing? “Sometimes two shots …” takes a close look at a brief passage from August Blom’s The Mormon’s Victim, a 1911 Danish one-reel film and finds a lot going on in it.

Some students might have trouble recognizing jump cuts. “Sometimes a jump cut …” looks at some examples from the martial-arts action scenes from two of King Hu’s masterpieces, A Touch of Zen and Dragon Gate Inn. These are quite different in look and function from the Breathless examples given in Film Art–and you can clearly see the splices.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

Faced with innovations in sound technology, we turned to our friend and colleague Jeff Smith. His “Atmos all around” is an excellent introduction to the new system. Unlike most surveys of technology, his piece analyzes in considerable detail how artists use it–here, in Pixar’s Brave.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Alfred Hitchcock is undoubtedly one of the most frequently taught filmmakers, since his work is not only stylistically elegant, but it’s easy for students to pick up on. One reason for this is that he is fond of flashy set pieces, scenes that are skillfully composed to be the high points of a film. We examine his skill in this regard in “Sir Alfred simply must have his set pieces: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH.”

On the other hand, Hitchcock is equally good at subtle touches. Some might consider his 3-D film, Dial M for Murder, to be a bit theatrical, since much of its action is confined to a single set. Yet as we argue in “DIAL M FOR MURDER: Hitchcock frets not at his narrow room,” the director finds many small, creative ways to frame and edit his shots in ways that are purely cinematic.

As we emphasize in Film Art, filmmaking is based on a huge number of creative decisions. During this past year, encounters with two practitioners gave us a chance to learn how they went about making some of these choices. Tim Hunter, director of River’s Edge (1987) and numerous episodes of television series like Twin Peaks and Breaking Bad, visited Madison. “Auteurist on the sound stage” discusses how Hunter plans ahead where he will place his camera, since the fast pace of television production allows little time for such decisions on the set. He also talks about tailoring his style to that of the specific television series he is working on.

In June David visited screenwriter and director David Koepp in his New York office. Koepp is best known for his work with Steven Spielberg, including the scripts for Jurassic Park and War of the Worlds, but he has also directed films. “David Koepp: Making the world movie-sized” discusses how Koepp finds the “Gizmo,” or basic premise, for big blockbusters and how he compresses the plots of best-sellers for the screen. He also talks about narrowing down the many choices available to a filmmaker, creating constraints that will allow him to find the best choices for a given situation–with camera placement again being a basic consideration.

This past year two major contemporary directors died: Tony Scott, director of flashy, violent Hollywood action films, and Theo Angelopoulos, maker of austere, stately dramas about Greek history and politics. We find some surprising stylistic parallels between their work, despite their obvious differences, in “Tony and Theo.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

Since The Blair Witch Project appeared in 1999, there has developed a sub-genre of horror films masquerading as found-footage documentaries. “Return to Paranormalcy” focuses on the successful series of films that began in 2007 with Paranormal Activity and explores how each successive film has managed to vary the point-of-view conventions in order to maintain audience interest.

This chapter of Film Art contains a “Closer Look” box examining “Creative Decisions in a Contemporary Genre: The Crime Thriller as Subgenre.” Our entry “SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past” looks at two more recent examples of this genre, focusing on how their conventions revive and vary conventions that had been introduced in 1940s Hollywood films in this same genre. Here’s a good example of genre conventions coming and going in cycles.

For most people, the name “Kurosawa” conjures up only the venerated Akira Kurosawa, director of classics like Seven Samurai and Red Beard. But there is a younger Kurosawa, Kiyoshi, a contemporary filmmaker. While in Brussels in July, David had a chance to attend a screening of his Shokuzai. In “The other Kurosawa: SHOKUZAI,” David puts Kiyoshi Kurosawa in his historical context and analyzes the film as a combination horror film and crime thriller, as well as including some stylistic analysis.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

Shirley Clarke was a major director of experimental and documentary films. Portrait of Jason, her feature-length recording of the recollections and comments of a gay black man was re-released in a restored version last year. “I’ll never tell: JASON reborn” discusses its avant-garde approach to recording its subject’s account of what may or may not be the truth. The entry also details the restoration process, which involved material Clarke deposited at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s archive, the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research.

Of the five animated features from 2012 nominated for Oscars this year, three were made using the traditional stop-motion technique with puppets: Frankenweenie, The Pirates! Band of Misfits, and Paranorman. “Annies to Oscars: this year’s animated features” discusses them, as well as the computer-generated features, Brave and Wreck-It Ralph.

Chapter 11 Critical Analysis of Films

During the past year we’ve written quite a lot about film analysis. These entries might give some encouragement and suggestions to students embarking on their own critical studies of films.

In June the new online film journal, The Cine-Files, interviewed Kristin about her approach to film analysis. The editors kindly allowed us to post the interview, “Good, old-fashioned love (i.e., close analysis” of film” on our site as well. The interview includes discussions as such topics as, “Please tell us about something that couldn’t be understood without a frame-by-frame attention to detail.” It also discusses our recent forays into online video and PowerPoint analysis.

A lot of interpretation of films gets done, by professional critics and students, by fans, and by anyone who gets an idea about a film and offers it to the world. In Film Art, we suggest that valid interpretations of films tend to be based on close analysis of all aspects of the film. Needless to say, not every interpreter does the work of analysis before expounding their ideas. The feature documentary about amateur interpretations of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining gave us an opportunity to discuss this tendency in “All play and no work? ROOM 237.” Surprisingly, some ideas offered by the subjects of the documentary aren’t necessarily that different from those propounded by professionals.

Christopher Nolan is one of the most admired filmmakers in contemporary Hollywood. What sets him apart? We discuss some of his innovatory tactics in “Nolan vs. Nolan.” The focus is on Insomnia, but with mentions of Magic Mike, Memento, Inception, and The Prestige. The latter is our primary example in Film Art‘s chapter on sound, and this entry might offer useful background material for teachers who show The Prestige to their classes.

For many students, non-Hollywood films can be intimidating to watch and even more so to analyze. “How to watch an art movie, reel 1” offers hints for understanding and discussing art films. The film in question is Jaime Rosales’ Spanish film Sueño y silencio (2013). It hasn’t been widely seen, but one need not have seen the film to understand the analysis of its first twenty minutes. This entry discusses conventions of the art film that might help students in writing their own essays.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

One section of this chapter deals with “The Development of the Classical Hollywood Cinema (1908-1927).” In another new video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies 1908-1920,” we deal with the same period on an international level. The lecture traces many of the basic techniques of cinematic storytelling in use in modern cinema back to their origins in this crucial early period. For an introduction to the video, see “What next? A video lecture, I suppose. Well, actually, yeah …”

Of the three major European stylistic movements of the 1920s discussed in Chapter 12, French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage, Impressionism has traditionally been the most difficult to teach, due largely to a scarcity of prints of films from the movement. Now a group of major Impressionist films have become available on DVD, those made by the Soviet-emigré Albatros production company. In “Albatros soars,” we describe the films and their release in a prize-winning box set from Flicker Alley. We think students would find La brasier ardent intriguing, if puzzling.

David is at work on a book on 1940s Hollywood cinema. Left-over ideas from that project end up as blog entries now and then. These could fit in with the section, “The Classical Hollywood Cinema after the Coming of Sound, 1930s -1940s.” One such entry, “A dose of DOS: Trade secrets from Selznick,” looks at the hands-on approach of David O. Selznick, arguably the most important independent producer of the era. His guidance affected the style of Gone with the Wind, Rebecca, Spellbound, Duel in the Sun, and other classics of the Hollywood system. Another entry considers in-jokes planted in 1940s films.

David has also posted a related essay in the main section of his website, “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense,” dealing with the influence of mystery and detective fiction on films of the 1940s. For an introduction and link to this essay and to several other blog entries on filmmaking of the decade, see “The 1940s, mon amour.”

The final section of Chapter 12 deals with “Hong Kong Cinema, 1980s-1990s.” The recent death of Lau Kar-leung, one of the major martial-arts choreographers and directors of the 1970s and 1980s, led us to post an appreciation of his style and films in “Lion, dancing: Lau Kar-leung.” The final section provides many bibliographical sources and other information on Hong Kong cinema, as well as links to earlier entries on the subject.

Johnnie To is one of the few directors still successfully maintaining the tradition of Hong Kong action films. The latest of our entries on him deals with a recent release: “Mixing business with pleasure: Johnnie To’s DRUG WAR.”

DVDs to consider

At intervals we post round-ups of recent DVD and Blu-ray releases. The titles usually aren’t the big, recent, popular films, but more specialized items put out by companies like Flicker Alley, Eureka!, and Kino that specialize in issuing classic films, often in beautifully restored versions. A lot of these films have never been available on home video before, and they open up new possibilities for teachers who want to broaden their students’ viewing experiences. They’re also titles to recommend to those enthusiastic students who want recommendations for films they can view on their own.

“Classics on DVD and Blu-ray, for a fröliche Weihnachten!” deals mostly with German silent films, including a set of four starring the early superstar Asta Nielsen, and two films by G. W. Pabst: the first release of his debut film, an Expressionist-style work called Der Schatz, and the most complete restoration so far available of The Joyless Street. A new and longer version of Ernst Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao is included, as is a charming Technicolor version of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado from 1939.

Regular readers are familiar with our annual tradition of naming the ten-best films of the current year but of 90 years ago. For once all the films on our list of “The ten best films of … 1922” are all available on DVD, including a stunning print of Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse der Spieler and the Criterion Collection’s release of the Svenska Filminstitutet’s restoration of Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (better known in the USA as Witchcraft through the Ages).

As of September 28, Observations on Film Art will be seven years old.

Fantomas (1913).

Magic, this Lantern

Home page of Lantern (top half).

DB here:

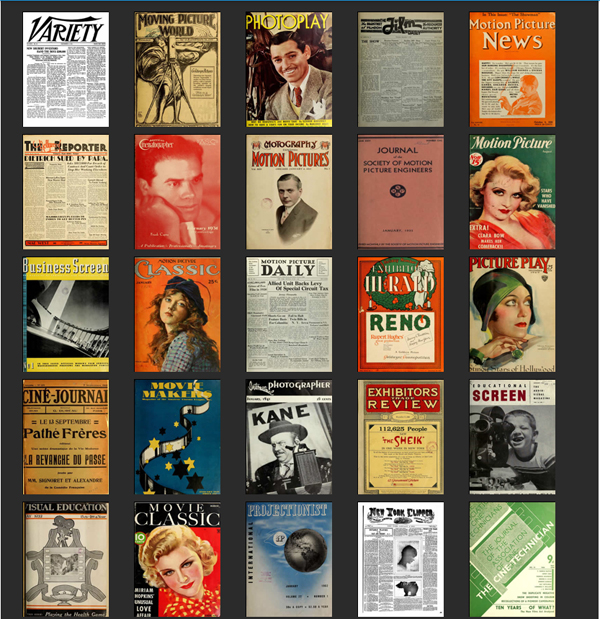

In earlier entries (here and here) we’ve reminded you of the immense and growing resource that is the Media History Digital Library. It was founded and is directed by David Pierce, world-renowned moving-image archivist, and it’s co-directed by UW-Madison Communication Arts professor Eric Hoyt. If you haven’t wandered, or rushed, or hop-skipped, through this wondrous library devoted to images and sounds, you owe it to yourself to start.

Of course it’s a remarkable resource for historians of film, television, and radio. It gathers a huge number of periodicals that can be searched, read, and downloaded–gratis. Thanks to its hookup with the Internet Archive, you can access and own entire books. The tireless Catherine Grant gives us Film Studies for Free. David and Eric give us Film History for Free.

But it isn’t just professional and amateur researchers who benefit. Anyone even mildly curious about media in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries should take the time to browse through the fan’s paradise that is Photoplay, the show-biz churn of Variety, the techie wonderland that is Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers and International Projectionist and many other publications. I guarantee you will be surprised and delighted by what you find: Big pages, beautifully displayed, that can hold you, we might say, spellbound; or at least make you girl crazy.

Why have you held back? Perhaps the sheer number of collections was daunting. And previously you had to search each journal separately, year by year.

Now Eric and his team, many here at UW, have made things even easier for historians and civilians alike. Today the MHDL crew have unveiled their new super-search engine, Lantern. Lantern allows you to search all of the MHDL publications at one go. Apart from the massive efficiency, you discover sources you wouldn’t have thought to check.

If you’re bold and type in Chaplin, for instance, you get 1446 hits. Many of them are from books, thanks to the generosity of Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, Jeff Joseph, and many contributors to the Internet Archive. I struck minor gold with my first hit, a page from Charlie’s 1922 travel memoir My Visit:

Dear Mr. Chaplin: You are a leader in your line and I am a leader in mine. Your specialty is moving pictures and custard pies. My specialty is windmills. I know more about windmills than any man in the world. . . . You have only to furnish the money. I have the brains, and in a few years I will make you rich and famous.

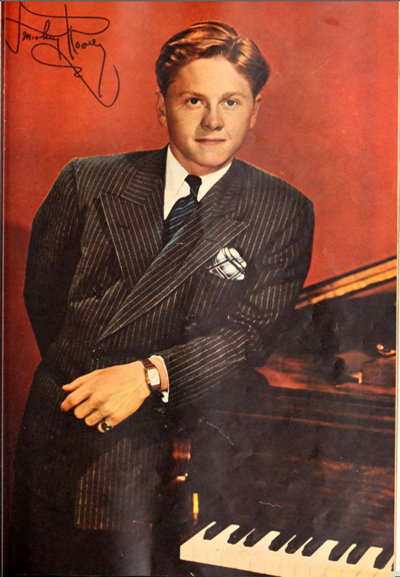

A search for Gregg Toland brings you not only his much-reprinted 1941 American Cinematographer article, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” but also many AC articles featuring professional discussion of his contributions–not all of them complimentary. “Pan-focus…,” notes one, “may be a flash in the pan.” An anonymous review of The Little Foxes complains that in some shots “The eye hardly knows where to look.” But go beyond AC and you find lesser-known treasures: articles by Kane’s on-set still photographer, a different piece by Toland (opposite a full-page topless young lady), and 52 more. That’s just in 1941.

A search for Gregg Toland brings you not only his much-reprinted 1941 American Cinematographer article, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” but also many AC articles featuring professional discussion of his contributions–not all of them complimentary. “Pan-focus…,” notes one, “may be a flash in the pan.” An anonymous review of The Little Foxes complains that in some shots “The eye hardly knows where to look.” But go beyond AC and you find lesser-known treasures: articles by Kane’s on-set still photographer, a different piece by Toland (opposite a full-page topless young lady), and 52 more. That’s just in 1941.

Yes, while the default search digs for everything, you can limit your search by year and along other parameters.

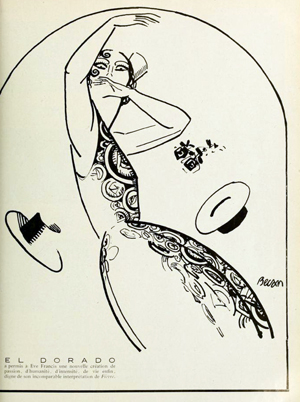

Lest you think that this bounty is of interest only for followers of Hollywood, please note that the Global Cinema collection (1904-1957) includes books and periodicals from France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Spain, and the United Kingdom. In 1921, for instance, Louis Delluc’s magazine Cinéa, while badmouthing Feuillade fairly constantly, gives unflagging support to L’Herbier’s El Dorado and adds in this sprightly caricature of Eve Francis.

Not all the collections are complete. There are of course copyright constraints on recent publications, and some journals are so rare that the runs must be filled in as copies are found. But the MHDL, like the universe, is constantly expanding, and possibly faster. Soon to be added are Quigley’s Exhibitors Herald, Cine-mundial, and more years of Variety. This spectacular enterprise is in the hands of people who are utter and dedicated completists.

I hate to pull a Grandpa Simpson, but when I think of all the time and money and gasoline and air tickets I ran through over several decades to visit libraries holding a few issues of this or that journal . . . and then think about the hours I spent paging through them looking for certain names, terms, film titles . . . and then think about how I painstakingly copied what I wanted onto 3 x 5 cards (photocopy not permitted) . . . I think–Well, what do you think I think?! I think how damn lucky you (and I) are to have all this material so accessible now. For work and play.

Same thing, come to think of it.

Thanks to Eric Hoyt for giving me a quick preview of Lantern, and to all my colleagues at UW-Madison who are supporting this remarkable undertaking. You can too: donations gratefully accepted.

P. S. 15 August 2013: Eric provides some helpful tips for using Lantern at the UW-Communication Arts blogsite Antenna.

Home page of Lantern (bottom half).

The enemy next door

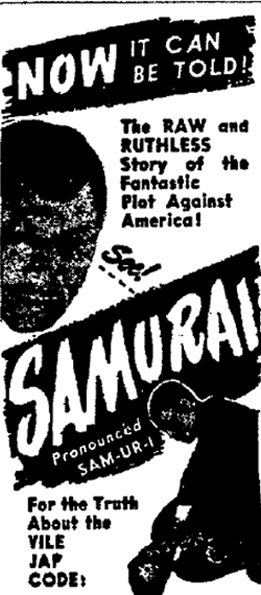

Left: Original caption: “Enforced farewell–These Japs wave farewell to relatives as they leave for Manzanar reception camp” (Los Angeles Times, 24 March 1942, p. B). Right: Advertisement for Samurai (Fitchburg [MA] Sentinel, 23 January 1946, p. 5).

DB here:

World War II never goes away, as the current attention given to Hollywood’s relation to Nazi Germany indicates. Thomas Doherty’s Hollywood and Hitler and Ben Urwand’s The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler trace how the American studios responded to the rise of Nazism and the launching of hostilities. While working on 1940s Hollywood, I ran across two films that deal with another member of the Axis. They remind us of some painful incidents in our history, and they show how inflamed patriotism can burst into racial panic and oppressive public policy.

Call it a mass migration

Soon after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, there arose a fear that saboteurs were at work in America. No solid evidence of this was demonstrated, but the most powerful decision-makers were not in a mood to be tentative. In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed an executive order that authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders to demarcate areas from which anyone could be excluded. The Pacific coast was declared such a zone.

In early 1942, the US Army rounded up 110,000 California residents of Japanese ancestry and sent them to what were called concentration camps. (At that point the term simply meant a camp in which enemy populations were “concentrated.”) The evacuees were dispersed to makeshift camps throughout California, as well as in Wyoming, Arizona, Oregon, and Washington state.

Some of the internees were first-generation immigrants, but about 90,000, were citizens. A 1942 government documentary film presents the “relocation” process as necessary for national security, and it shows the evacuees accepting, in a spirit of patriotic submission, the need for such measures. In the film the evacuees effortlessly re-create their communities in their new locations.

Bizarre as it sounds today, the film takes pride in showing that a democracy can create humane concentration camps. But a reading of Richard Lingeman’s Don’t You Know There’s a War On? points up some things the film doesn’t say. The film doesn’t mention that the people rounded up were forced to abandon their homes, businesses, and farms and were permitted to take only what they could carry. (Newspapers often described the relocation as “voluntary.”) The film doesn’t show that the relocation centers were jerry-built, some by the inmates themselves, and were often located in harsh climates. The camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, was subject to sandstorms, blizzards, and subzero temperatures. Nor does the documentary note that the camps were enclosed in barbed wire and watched over by armed guards in security towers. Nor does the documentary show that, because Japanese-American farms produced 40 percent of the California vegetable crop, rival growers pressed for the internment and then snapped up the displaced farmers’ lands at what Lingeman calls “eviction–sale prices.”

The Japanese weren’t unique in undergoing internment; other ethnic groups were subject to investigation, confinement, and relocation. But no other minority was subjected to such a comprehensive roundup. It’s estimated, for example, that about 11,000 German-Americans, innocent or suspected, were interned–a significant violation of their rights, but nothing on the scale of Japanese internment. White people of European extraction, German-Americans had become pillars of American society, and were very numerous. (They were and remain the largest U. S. minority self-identified by descent.) Japanese-Americans, a much tinier and more vulnerable minority, were more easily marked as potentially alien to American values.

Late in 1942, the government began resettling Japanese-American internees outside the camps, spreading them to several states. In December of 1944, partly as a result of a Supreme Court decision the government could not consign “concededly loyal” citizens to camps, authorities declared that the west coast was no longer a war zone. But fears of Japanese espionage didn’t subside, as we can see from a 1945 independent film called Samurai.

Pledged to the God of War

Samurai shows an adopted Japanese boy growing into a traitor and spy. In September 1923, Mr. and Mrs. Morrey rescue Kenkichi from the ruins of the Tokyo earthquake and bring him home to San Francisco. While attending school and assimilating into American society, Kenkichi secretly visits a Buddhist temple where the priest inculcates him in the martial tradition of Bushido, the way of the samurai. Studying to be a doctor, Kenkichi becomes a proficient painter. At the same time, he swears to live and die by the sword, repeating the priest’s pledge that “The God of War presents the key to eternal life!”

The unsuspecting Morreys send Kenkichi to Italy and Germany for his studies, and the priest exhorts him make contacts that will train him as a secret agent. Back in America he begins painting abstract landscapes that conceal military information in coded form–a strange version of that motif of paintings and portraits that winds through 1940s American cinema (The Two Mrs. Carrolls, Suspicion, The Ministry of Fear). When the painting is abstract and nonrepresentational, it usually suggests that the painter may be mad.

Telling his parents that he will be a curator of Asian art, Ken goes to Tokyo and there, at the Black Dragon Society, he decodes his paintings. The Dragon Society’s leader suspects that his visitor is an American spy, but the doubts are dispelled when Kenkichi alters photos from Shanghai to appear that the Japanese are aiding the Chinese. Ken further proves his loyalty by murdering a journalist. He is assigned to the unit of General Sujiyama as a full-fledged spy.

Back at home, Kenkichi tells his priest of his mission, and shows what his reward will be: When the Japanese take over the west coast, he will become governor of California. Explosives are smuggled in, and Japanese farmers (“another link in the chain,” the voice-over narrator tells us) are coordinating domestic spies and saboteurs. The Morreys’ younger son Frank discovers Ken’s plot and tips off the police, while Kenkichi tries to convince the parents that he’s a double agent—before stabbing his father to death. Meanwhile, the invasion has been synchronized with the Pearl Harbor attack. At the climax, the temple priest realizes that his spy network has been arrested and his plan has failed. He commits ritual suicide, but Kenkichi, after brandishing the long samurai sword boldly, doesn’t follow the warrior’s way and instead flees to the beach. There he’s shot down by the police.

Premiered in New York in August 1945, after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Samurai seems to have gotten a very limited release. It’s a cheap production, filled out with montages of newsreel footage, feeble special effects (the back-projection of the Kanto earthquake is especially jarring), and minimalist studio sets. Chinese actors, some with prior Hollywood experience, played the Japanese characters. The device of Kenkichi’s coded paintings seems to be borrowed from illustrative examples of espionage techniques filed as evidence in the 1942-1943 Dies Committee investigation. The We-want-your-white-women motif is made salient in a scene in which Ken and General Sujiyama disport with women captives. Ken toys with a blonde before tripping her.

During the same scene, a Chinese woman fights off the General’s advances before tearing up the Japanese flag. As was typical of the period, the Chinese were presented as courageous and defiant in the face of the Japanese invasion.

Samurai was planned in 1943 under the title “Confessions of a Japanese Spy,” an echo of Warners’ Confessions of a Nazi Spy of 1940. According to the AFI entry, another working title was Orders from Tokyo. Producer Ben Mindenburg supplied the story, and the director Raymond Cannon (who worked intermittently at Fox, Monogram, and elsewhere) is credited with the screenplay. Scenes suggesting rape of the General’s captive women displeased the Production Code Administration. The picture was awarded a PCA seal eventually, so perhaps some portions were omitted.

110,000 people inconvenienced

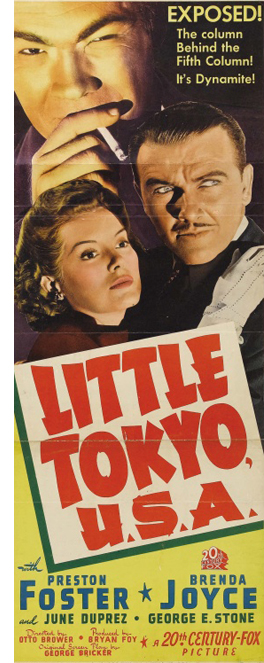

As a minor independent production with small circulation, Samurai can be dismissed as an outlier. It apparently wasn’t reviewed in Variety, but the New York Times called it “an example of opportunistic filmmaking . . . lurid and sensational. At this late hour, a motion picture should do something more than just shout, ‘The Japanese are brutal, scheming beasts.’” Yet three years before, in summer of 1942, Twentieth Century-Fox released a B-film that is hardly less virulent, and the Times, though finding it a “mediocre melodrama,” paid homage to its authenticity in pinpointing “details about incidents of espionage plotted in Los Angeles’s Japanese colony.”

Little Tokyo, U.S.A. (1942) centers on plainclothes detective Michael Steele, who suspects a Japanese family of receiving radio messages from Tokyo. After Steele’s friend Oshima agrees to check around, his corpse is found decapitated. Pursuing the case, Steele is brought up against a gang led by Takimura, an obsequious importer, and a German-American called Hendricks. As head of the local radio station, Hendricks allows the Japanese agents to use the transmitter to send messages to Tokyo. Hendricks also happens to be the boss of Steele’s girlfriend Mavis, a radio commentator.

Little Tokyo, U.S.A. (1942) centers on plainclothes detective Michael Steele, who suspects a Japanese family of receiving radio messages from Tokyo. After Steele’s friend Oshima agrees to check around, his corpse is found decapitated. Pursuing the case, Steele is brought up against a gang led by Takimura, an obsequious importer, and a German-American called Hendricks. As head of the local radio station, Hendricks allows the Japanese agents to use the transmitter to send messages to Tokyo. Hendricks also happens to be the boss of Steele’s girlfriend Mavis, a radio commentator.

Steele’s investigation is blocked when he can’t find the radio used by one of the gang to receive instructions from Tokyo. Takimura murders Teru, Hendricks’ Japanese mistress, and Steele is framed for the crime. Steele is in prison when Pearl Harbor is attacked. As “dangerous aliens” are rounded up, he escapes and finds Takimura’s hideout. Mavis, who has been skeptical of Steele’s suspicions, is taken captive by the gang. Takimura finds Steele hiding out in the city morgue. But when they confront Steele he springs a trap of his own: cops burst in and seize the conspirators. The film concludes with Mavis broadcasting the need to stay vigilant.

If Samurai crudely employs techniques of current semidocumentary (voice-over narrator, newsreel footage, some location shooting), Little Tokyo, USA remakes the G-man film into an affair of domestic espionage. We get the familiar frame-ups, the silhouettes and night streets, and the montages of headlines and police dispatches. Given how supple Fox’s B-pictures often were in the 1930s, with the Moto and Chan films and the Sherlock Holmes series, this is a very routine affair. The major Japanese villains are played by Caucasians in Yellowface; even the ubiquitous Abner Biberman (in the poster at right) is recruited to look Japanese.

Unlike Samurai, Little Tokyo, USA indicates that there are loyal Japanese-Americans like Steele’s friend Oshima. Nonetheless, the film buys wholly into the notion of a pervasive Japanese menace. A voice-over prologue presents this as a “film document,” and provides a montage of Japanese men photographing industrial and military sites much like those Kenkichi scouted in Samurai. More subtly, after Pearl Harbor, members of Takimura’s gang are shown putting up signs in their shops claiming to be patriotic citizens—something that many innocent Japanese-Americans did to forestall reprisals. Takimura even establishes a charity that purportedly finances the building of bomber planes.

Beyond spreading a general mistrust, the film aims to justify Japanese-American internment. To do this, it has to show that, as the prologue’s voice-over puts it, before Pearl Harbor Americans had been lulled into a false sense of security by “the mouthing of self-styled patriots.” So we meet several characters who exhibit fatal naivete. Early in the film, Mavis’ broadcast voices her hopes for peaceful negotiation with the Japanese. After Japanese-Americans protest Steele’s investigation, his superior claims:

The Japanese are peaceful, harmless, industrious citizens. They’re loyal too—most of ‘em. ‘Course there may be some rats in the bunch, but that’s nothing to get excited about. I was reading only this morning that 93 percent of the vegetable crop of California is in the control of the Japanese.

Steele replies:

Yeah, I know. They’ve got farms right next to all the airplane factories, and the dams, and the oil-storage concentrations.

He goes on to claim that the farmers lose money, but they’re subsidized by funding from a Tokyo bank.

On the other side, Takimura warns his gang that internment is what he fears most. “Mass evacuation will defeat our operation here.” Fortunately, he remarks confidently, evacuation will be blocked by Japanese civic groups and “certain sympathetic American interests.” This phrase casts anyone who might object as an unwitting tool of the Axis.

A new problem arises when the film must admit that not all 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry on the coast could be Fifth Columnists. So, like the government documentary, and like the LA Times news photo of grinning men bound for a resettlement camp, Little Tokyo, USA treats the innocent evacuees as accepting internment in a cheerful spirit. It’s proof of their patriotism and their contribution to the war effort. Here are the film’s final scenes, including some documentary footage of relocation and the empty streets of Little Tokyo.

At the denouement Steele punches Takimura (“That’s for Pearl Harbor, you slant-eyed–“) and Steele’s captain abandons his misplaced sympathy by clobbering the “squarehead” Hendricks. In the final scene, Mavis, her eyes now open, uses her broadcast to explain the need for some to sacrifice.

And so in the interests of national safety, all Japanese, whether citizens or not, are being evacuated from strategic military zones on the Pacific Coast. Unfortunately, in time of war the loyal must suffer inconvenience for the disloyal.

As happens today, those calling for sacrifice from others usually give up nothing themselves.

I offer no fancy analysis of these humdrum films. It simply seemed to me that, on the eve of the anniversary of the US bombing of Nagasaki, it would be worth remembering how quickly Americans in a state of war could find enemies among civilians overseas and in our cities here. Among us today there are many who would happily call for some American minority to be rounded up, locked up, sent away, put out of sight somehow. Look around you, as Resnais and Cayrol remind us in Night and Fog, and you will see the eager faces of future jailers.

Thanks to the staff of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium for permitting me to view Samurai. On the role of race in the Pacific War, see John Dower’s War without Mercy. The Dies Committee, later known as the House Un-American Activities Committee, produced a report on Japanese espionage that makes astonishing reading. Here is one passage:

California, with its mild climate and extraordinary agricultural resources, delighted the industrious Japanese. In fact, some of their vernacular newspapers went so far as to call California ”the New Japan.” They were not content to remain day laborers, as had the Chinese, but rapidly acquired their own land, or leased farm land which they frequently worked to depletion. Their women worked alongside the men in the fields for long hours, often with their babies strapped to their backs. Whole towns became Japanese, the native white population gradually leaving areas where the Japanese settled, since competition with them was so difficult if not impossible. They were assertive and aggressive, and did not achieve the reputation for honesty and faithfulness that was enjoyed by the Chinese. California fearfully envisioned the complete control of her agricultural land by the acquisitive Japanese, and became thoroughly aroused. Feeling ran high, but there was little of the violence against the Japanese which had unfortunately marked the agitation for exclusion of the Chinese.

The New York Times review of Samurai appeared on 24 August 1945, p. 7. Variety‘s review of Little Tokyo, U.S.A. appeared in the issue of 8 July 1942, p. 8, and the Times review was published on 7 August 1942, p. 13.

Interestingly, the documentary Japanese Relocation appropriates portions of Virgil Thomson’s scores for Pare Lorentz’s documentary The River (1938), and I think I heard a bit from The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) as well. Presumably the government owned the rights.

Every day brings a fresh example of highly-placed and lunatic bigotry against immigrants to the US. Consider this. Or this.

The photograph below of a Nagasaki in 1946 is from the National Archives; I have taken it from the site About Japan. The quotation at bottom is from Life magazine, 20 August 1945, 27.

Seventy-five hours after the world’s first atomic bombing, an interval marked by President Truman’s demand for unconditional surrender, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, shipbuilding port and industrial center. This bomb was described as an “improved type,” easier to construct and productive of a greater blast. It landed in the middle of Nagasaki’s industries and disemboweled the crowded city. Unlike the Hiroshima bomb, it dug a huge crater, destroying a square mile–30% of the city.

When the bomb went off, a flier on another mission 250 miles away saw a huge ball of fiery yellow erupt. Others, nearer at hand, saw a big mushroom of smoke and dust billow darkly up to 20,000 feet and then the same detached floating head observed at Hiroshima. Twelve hours later Nagasaki was a mass of flame, palled by acrid smoke, its pyre still visible to pilots 200 miles away.

The bombers reported that black smoke had shot up like a tremendous, ugly waterspout. Physicists at the bomber base theorized that this smoke was the pulverized fragments of the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works. With grim satisfaction they declared that the “improved” second atomic bomb had already made the first one obsolete.