Archive for November 2010

Trade secrets

DB here:

Over the last couple of months, some strange things have been happening to America’s most venerable show-business trade papers. In the case of Variety, the strange thing is very important and yields almost unalloyed good news. In the case of The Hollywood Reporter, the strange thing is, at least for the moment, a step backward.

Kristin and I have subscribed to weekly editions of both newspapers since the mid-1990s. With the advent of Web 2.0, each paper created an online archive, more or less searchable, stretching back into the 1990s. Not everything you would wish for, since Variety started publishing in 1905 and The Hollywood Reporter began in 1930. But film historians are grateful for anything. I found both papers’ archives very helpful in reworking Planet Hong Kong over the last year. Now, however, some of the recent happenings affect our ability to do research.

Issues about issues

First the bad strange new thing. In a collapsing advertising market, The Hollywood Reporter has done a makeover. From being a daily and weekly trade paper it turned into an upscale lifestyle weekly, sort of an industry-slanted version of Vanity Fair‘s movie issue, with a soupçon of airline magazine. Among the recycled press releases, superficial interviews, soft-focus profiles, and awards-season handicapping, you find fashion tips like “Into the Blue: Punch up your executive look—top to toe—with the season’s blockbuster hue.” There’s also the sort of feature that movers and shakers can use to promote themselves: “Hollywood’s Young Guns ….Where they work, why they matter, how they’re changing the game.”

True, Variety sometimes resorted to such frippery in these desperate years. V-Life was in some ways a forerunner of the new HR, but V-Life was a supplement. In the main paper you could still find reportage, analysis, overviews, and opinion. There’s relatively few of these ingredients in the new Hollywood Reporter.

If this is the strategy for fighting Movie City News and Deadline Hollywood and IFC, I’m betting on the webroots.

Anyhow, forget the daily THR ephemera. I want to go into the past, as I did until October, scrambling through elusive coverage of Hong Kong stuff. Problem is: I can’t do that any more.

THR not only remade its magazine; it remade its website, radically. So radically that when I go there via Safari or Chrome I get this welcome.

Well, you say, skip your bookmarks and go through Google. But then:

Only Firefox does the trick.

Anyhow, at last I’m on. Breaking News today starts with “Jennifer Grey Wins ‘Dancing with the Stars’; Bristol Palin Comes in Third.” Skip that. As a subscriber, I ought to be able to log in to the proprietary content, right?

Here is the routine. Using my old password, I have no luck. When I call the 800 number, an ominous recording tells me that they are aware of the “issues” (what we used to call “problems”) with the website and subscriber logins. After half an hour, a hard-working person answers and with a few magic passes of her mouse she gets me into the subscriber areas.

Yet the next time I try, I’m refused again. So I write to the email service they announce, and immediately get a form reply saying that my problem will be addressed in 1-2 business days. The next communiqué, from some days later, begins: “We apologize for the delayed response.” They give me a password which is suspiciously generic.

This has been going on for nearly three weeks. But I can live with it because I’m not so concerned with Jennifer Grey or Bristol Palin. I’m there for the archive.

Problem is, the Archive isn’t there for me. Once I’m inside as a subscriber, I find no way to get into the two decades of stories and stats I could reach under the earlier incarnation of the website.

Another call, another recording apologizing for the “issues,” another half-hour of wait, and now a very puzzled answerperson. Where’s the Archive? Nobody ever asked him that before. He’s no better than I am at finding a button for it. He consults his supervisor. The supervisor doesn’t know where the Archive went either.

You can search the site, he points out. True, but the search takes me only to items posted since the makeover began.

Hmmm. The best they can do is suggest I call the Editorial Offices. When I do, the recording instructs me to leave my story tip and someone will get back to me. I might say, “Psst, I have it on good authority that the next big color will be vermillion,” but instead I hang up.

Trying tonight, I find that the search function now turns up articles published throughout calendar 2010, but no earlier. So maybe THR will gradually expand its backfile. It would be too bad if the dolled-up version of the print mag drained resources from maintaining a stable and deep website. I worry that THR intends to dump the old (already very partial) online archive altogether, resetting the clock at the year of the makeover. If so, they send a signal that the past—theirs, that of the industry they cover—doesn’t matter. They wouldn’t even agree with Jack Valenti, who supposedly did say, “It’s only history,” and then opened the MPPDA papers for research.

Infinite Variety

13 September 2010 was the date of the good thing that happened to the trade papers. At that point, Variety went the opposite direction of The Hollywood Reporter. It opened up its vault completely.

For many years film historians have relied on Variety for detailed information about how Hollywood and other national industries have worked. Most of these historians have scanned the paper on microfilm, cranking through reel after reel, getting dizzy from the whizzing lines your eyes try to fasten on. But these scholars managed to do real research. You couldn’t believe everything you read in the paper, of course; you had to be skeptical. Still, getting something was always better than getting nothing.

More recently, Variety has kept an online archive of its materials since the early 1990s. These stories were in html-friendly format, not in the form of published pages, and some stories that appeared in the paper never made it online or were revised for the net. Older stories, mostly film reviews, were summarized and undated. So as records, they were only partly reliable. Still, even this iceberg-tip was well worth surveying.

In September, though, Variety put online its back file from 1906 to the present. Every page of the weekly and daily paper has been digitized. You can access it for a year for a $600 subscription fee, probably what many people pay for designer coffee over the same period. If you want shorter-term access, $60 gets you into up to 50 issues per month.

Reader, I signed up.

There were teething pains for a few weeks. Some pages failed to load, and often you had to scroll through an entire issue to find the page you wanted. But those “issues” are mostly in the past. Now you can plunge into an ocean of well-mapped movie coverage.

As usual with people of my generation, I’m shaken by the abrupt transition from a research economy of scarcity to one of overabundance. Had this bounty existed when Kristin and Janet Staiger and I wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, we might still be writing it. Type in “John Ford” or “Meet Me in St. Louis” and you’re led into the labyrinth, with one item teasing you to search others, forever.

Some things, for instance, seem never to change. “CINEMAS TO SURVIVE HI-TECH ERA,” wrote A. D. Murphy in the 4 August 1982 issue’s top story. People were claiming that the theatre experience would soon vanish (presumably because of home video, although that’s barely mentioned). No way, says Murphy, citing several reasons, including the plausible assumption that “Nothing yet has managed to keep young people confined to their homes.” He adds that going out to the movies is the most robust form of “pay per view….free of all that bother of billing, dunning, disconnects and such.”

Yet a stroll through the vault can also remind you of how strange things were back then. How’d you like to sit through a live opening act before Citizen Kane? Variety tells us that in San Francisco’s Golden Gate theatre in early September 1941, Kane did brisk business at popular prices. It was accompanied by the vaudeville act of one Prof. Lamberti. The local Hearst newspapers, while refusing to advertise Kane for the unsurprising reason that Hearst thought the movie was about him, did advertise Prof. Lamberti’s act at the house. He was worth paying attention to. He never made snide fun of Marion Davies.

Yet a stroll through the vault can also remind you of how strange things were back then. How’d you like to sit through a live opening act before Citizen Kane? Variety tells us that in San Francisco’s Golden Gate theatre in early September 1941, Kane did brisk business at popular prices. It was accompanied by the vaudeville act of one Prof. Lamberti. The local Hearst newspapers, while refusing to advertise Kane for the unsurprising reason that Hearst thought the movie was about him, did advertise Prof. Lamberti’s act at the house. He was worth paying attention to. He never made snide fun of Marion Davies.

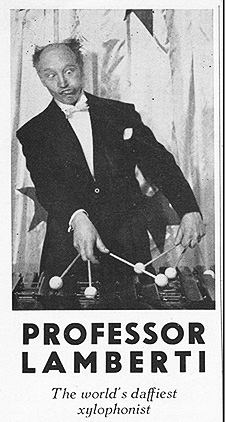

But who was Prof. Lamberti? A magician, a musician, a real prof? We check Variety for 22 March 1950 and learn from his obituary that “Professor” Lamberti was a comedian who played on stage and in nightclubs. According to the obit:

Lamberti’s best known act was playing the xylophone, while shapely gal did a striptease back of him and he was apparently unaware of the goings on. This provided the delusion that successive encores on the semi-classic tunes such as “Listen to the Mocking Bird” were prompted by the audience’s music appreciation, rather than the bumps and grinds of the peeler. Howl finish had the comic get hep and seltzer squirt the gal off stage.

I ask you: How could a red-blooded American male viewer concentrate on the ambiguities of Thompson’s quest after an opening act like that? And as a mood-setter for the opening sequence at Xanadu, the World’s Daffiest Xylophonist might not be ideal. Even more striking, we learn from the same obit that Prof. Lamberti did his signature bit in the film Tonight and Every Night (1945) with Rita Hayworth “as the strip-gal”—the same Rita Hayworth who was then married to Citizen Kane’s director.

Aha, you say, but Wikipedia has an article on Prof. Lamberti too, and with more details than the Variety obit. (Please visit this orphan entry; it needs hits.) I would never badmouth Wikipedia, that wonder of our young century, but it’s not yet the poor man’s Variety vault. For one thing, it doesn’t use the phrase “bumps and grinds of the peeler.” Further, I can find no help on Wikipedia on a looming question that has vexed some of our best minds: At what aspect ratio should Lang’s While the City Sleeps (1956) be shown?

A lack of ‘Scope

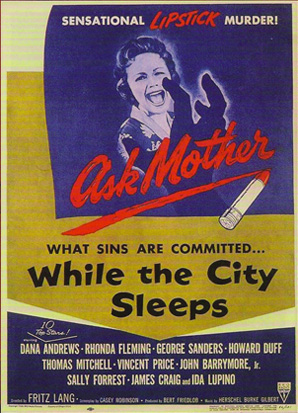

There is a full-frame version occasionally broadcast on Turner Classic Movies and now available on Region 2 DVD. There’s also a 1.66 crop that was released on laserdisc many years ago. Some older cinephiles recall seeing a widescreen anamorphic version circulating on 16mm. Yet Lang apparently claimed he did not shoot the film in anamorphic widescreen.

When While the City Sleeps was made, the releasing studio RKO was supporting a widescreen system called SuperScope. That’s what Variety called it, anyhow, though sometimes you’ll see the name with a small middle s, or with “Super” italicized.

Invented by the brothers Joseph and Irving Tushinsky, SuperScope was a progenitor of the Super-35mm system of today. A film shot in standard full-frame 35mm would be turned into an anamorphic one. A portion of the frame was extracted, optically squeezed, and printed as an anamorphic image, which would then be unsqueezed in projection. The aspect ratio was 2.0:1. The reasoning was that it was easier to shoot a movie in the standard way and then “SuperScope” it than it was to shoot a CinemaScope film. Some projectionists called this process BogusScope, not just because it was fake but because Benedict Bogeaus was then a producer feeding projects to RKO, and some of his titles used the format.

Slightly Scarlet and Invasion of the Body Snatchers, both released in 1956, were designed to be given the SuperScope treatment. The films carry the logo in their credits, and contemporary Variety reviews mention the process by name (15 February 1956 and 29 February 1956). The accompanying Italian poster for While the City Sleeps also makes reference to the SuperScope process. But there is no mention of SuperScope on the release print, or in the Variety review (2 May 1956), or in the US release poster, or in the pressbook kindly posted online by TCM.

Lang is on record, in Peter Bogdanovich’s Who the Devil Made It, as saying that he disliked CinemaScope. He told Bogdanovich that he agreed with his famous claim in Godard’s Contempt that “CinemaScope is only good for snakes and funerals” (p. 224). But SuperScope is not CinemaScope (which is 2.35:1 or sometimes even wider), and moreover Lang made one of the better CinemaScope films in Moonfleet (1955). So the question can’t immediately be resolved on auteur grounds.

Moreover, SuperScope prints of While the City Sleeps do exist. I found one in a European archive some years ago. It was pretty fuzzy (a chronic problem with SuperScope prints, because of the rephotography involved), but I took some frames from it. Here are some comparisons with the 1.37 DVD.

For my purposes here, I could have simply cropped and blown up the full-aperture frame grabs, but I’d rather preserve the slightly bulgier quality that seems to have come with the anamorphic optics. Also, because the wider versions are from 35mm frames, they include a little more area on the sides, which is lost in video versions like my DVD grabs on the left.

Actually, the widescreen version isn’t terribly offensive to me. For one thing, it slices off that slab running across the top of the bar set in the first image above. But in some cases the change in shot scale and internal relations make for mild differences in emphasis. The SuperScope version brings characters quite a bit nearer to us. Do they also seem seem closer together? There’s also the matter of taste. Some will dislike the headroom in the left shot below, while noting that the right one looks like a classic early ‘Scope composition.

So which one is the original? You can sample the online cinephile discussions from 2003 onward here and here and here. The ever-diligent folks at DVD Beaver have much to add as well.

Fortunately, about five minutes of snooping in the Variety vault reveals the answer.

Joseph and Irving Tushinsky yesterday concluded a contract with RKO for conversion of “While the City Sleeps” into the SuperScope process for foreign release (“SuperScoping ‘City,’” Variety, 12 April 1956, p. 3).

According to other stories in Variety, several films were given the SuperScope treatment ex post facto, including a re-release of Olivier’s Henry V (1945).

So we can confirm the hunch expressed by some of the cinephiles above that the SuperScoped copies were destined for overseas screenings. The Variety vault proves useful for things both great and small. Okay, mostly small, but you get my point.

Scoping things out: An epilogue for ratio fetishists

SuperScope logo for Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

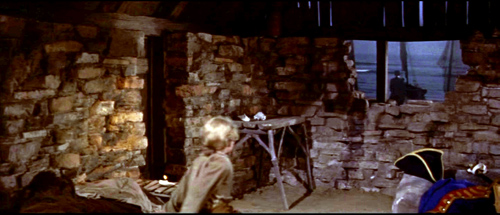

There’s still all that headroom in the full-frame images. That roominess is fairly uncharacteristic of Lang. In his pre-widescreen films, he used the whole frame, even the corners. Try SuperScoping this tightly-packed shot from Kriemhilde’s Revenge.

In Cloak and Dagger, Cooper’s character uses the apple on the workbench to explain the power locked up in the atom, and apples will become thematically significant in a later Adam-and-Eve scene.

Moonfleet also takes advantage of the lower right corner (see the image at the very end of today’s entry). But Lang’s last two American films, While the City Sleeps and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), seem to me to have more open and less compact compositions. There’s quite a bit of unused furniture in City‘s mise-en-scene, even though it adds a Vidor-Fountainhead air of vastness.

At this point we should recall that by 1956, most U. S. theatrical releases were shown in something wider than 1.33. There was a lot of variability, but films were commonly cropped in printing or projection to 1.66 or 1.75 or 1.85. Even if Lang did not shoot City with an anamorphic ratio in mind, he might well have assumed there would be cropping to some wide ratio. The approximately 1.75 ratio seen on the laserdisc version looks like a reasonable compromise between the extremes.

I’m inclined to say that Lang expected the film to be cropped somewhat in projection, but probably not to the full 2.0 proportions. He could no longer count on projectionists’ framing a single ratio, so he doesn’t tuck details along the edges or into the corners.

Unfortunately, I can’t find confirmation of Lang’s wide-frame choices in the fabled Variety vault. But I’m still looking, there and elsewhere. And maybe some researcher reading this entry can clarify things further. In any case, Variety has given a magnificent gift to those of us interested in film history–who ought to be everybody.

The standard source on widescreen systems of the postwar era is Robert E. Carr and R. M. Hayes, Wide Screen Movies: A History and Filmography of Wide Gauge Filmmaking (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1988). Carr and Hayes discuss SuperScope, or as they call it SuperScope (the credit logo is actually in caps, as in SUPERSCOPE) on pp. 67-72 and list the films in that format on p. 104. They don’t include While the City Sleeps. See also Daniel Sherlock’s comments on the book at Film-Tech.

Writing this has led me to wonder whether the admiration of European, especially French, critics for While the City Sleeps is based on their seeing the anamorphic version. In their writings I haven’t found specific reference to SuperScope. Raymond Bellour’s probing 1966 essay “On Fritz Lang” is one of the few I know from that period to scrutinize the patterns of composition and framing in While the City Sleeps, but I can’t tell whether he’s referring to the widescreen version. An English translation is in Fritz Lang: The Image and the Look, ed. Stephen Jenkins; see pp. 31-35.

Although Turner Classic Movies has run While the City Sleeps in 1.37, the TCM website recommends that it play at 1.66. Interestingly, the illustrations in Tom Gunning’s Films of Fritz Lang are in about 1.75:1 ratio. Another SuperScope production, Jacques Tourneur’s Great Day in the Morning (1956), runs on TCM in this ratio. Since projectionists of the period, and still today, are fairly flexible about ratios, it’s possible that even anamorphic 2.0 SuperScope was projected with a little trimmed from the sides.

A DVD release of Invasion of the Body Snatchers includes both a SuperScope 2.0 version and a 1.37 one. But the 1.37 one is a pan-and-scan version of the SuperScope one, not the integral frame that SuperScope worked from. The DVD version of Slightly Scarlet from VCI International is framed at 1.78, and the transfer (of poor optical quality) has been bungled so that everything is slightly stretched left to right. Both Arlene Dahl and Rhonda Fleming are more zaftig than they should be.

For more on aspect ratios, you can go here and here on this site. I experiment with extracting ‘Scope proportions from a 1930s movie in a general essay on widescreen aesthetics, “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses,” in Poetics of Cinema, p. 323.

Correction (28 November 2010): The original version of the piece claimed that the Search function of the Hollywood Reporter website found only pieces published since the recent makeover. That was the case when I used it two weeks ago. A more recent search I conducted this evening turned up articles from throughout 2010. I have recast the entry to reflect this change.

PS (17 December 2010): More developments on the Hollywood Reporter backfile, and more on the uses of the Variety Vault are discussed in this later entry.

Moonfleet.

Time out for thanks

KT (working away on Amarna artifacts in London) + DB (working away finishing Planet Hong Kong 2.0):

Here in the US it’s the Thanksgiving holiday, so we’re taking off this week. In the meantime, we want to thank all the readers who visit our site. Next week we’ll return with more bloggy thoughts.

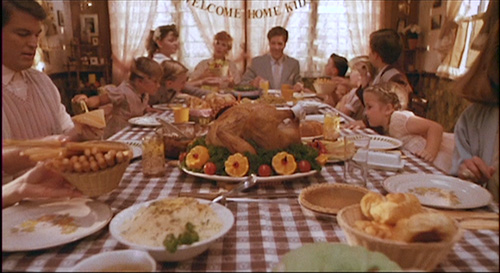

Raising Arizona.

Once upon some times in Hong Kong

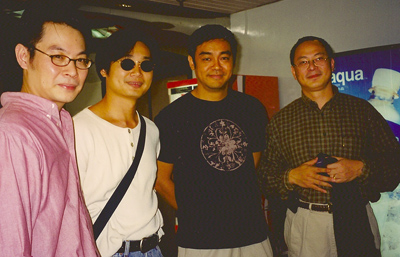

Johnnie To Kei-fung on the set of Running out of Time 2.

DB here:

Exactly nine years ago, Kristin and I were in Hong Kong. Lau Shing-hon, head of the film division of the Academy for Performing Arts, had arranged for me to be Sir Edwin Youde Memorial Fund Visiting Professor. It was a great honor, and Kristin and I enjoyed many happy sessions with Shing-hon, his colleagues, and his students. On this trip, though, something else happened. That lucky encounter has had consequences for my thinking about cinema throughout all the years since.

The encounter was the result of unintended networking. Jeff Smith, now a professor here at Madison, had been my TA in the early 1990s, when I was starting to include Hong Kong films in my courses. He caught the bug. While Jeff was teaching at NYU, a young Taiwanese man, Shan Ding, took some of his courses. Shan, who was naturally as keen on Hong Kong cinema as we were, wound up going to Hong Kong and eventually getting a job with Johnnie To Kei-fung.

So it was during our November 2001 stay that I got a call from a friend, who said that Shan was trying to reach me. Shan wanted to get together, but not in the customary coffee shop or noodle restaurant. He invited Kristin and me to come to a set.

Local heroes

Lifeline.

While doing research for my book Planet Hong Kong in 1996 and 1997, I managed to interview several directors, screenwriters, cinematographers, and action choreographers. Johnnie To was on my list of people to meet because of the cult classics The Big Heat (1988), Heroic Trio (1993), The Executioners (1993), and Loving You (1995). There was also his prestige picture, All about Ah-Long (1989) and an extraordinary movie I saw during one trip to Hong Kong, the firefighter drama Lifeline (1997). At about this time Mr. To was launching his own production company, Milkyway Image.

I keenly wanted to talk with Mr. To, but for various reasons it didn’t prove possible. I submitted my manuscript to the publisher in mid-1998, so I couldn’t incorporate discussion of the three Milkyway masterpieces of that year: Expect the Unexpected, The Longest Nite, and A Hero Never Dies. By the time the book came out in early 2000, there had been three more: Where a Good Man Goes (1999), Running Out of Time (1999), and possibly To’s finest work, The Mission (1999). There I was: the most important director of the late 1990s and early 2000s was largely left out of my book.

Ironically, soon after PHK came out, Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love and Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon triumphed at Cannes. Westerners’ perception of Chinese film changed forever. But in all this fuss, where was Johnnie To?

Making movies, that’s where. He emerged as a heroic figure of local film of the 2000s. True, Infernal Affairs (2002) and Stephen Chow Sing-chi and Wong Kar-wai sustained interest in Hong Kong movies on the international market. But Wong and Chow made films at long intervals, while IA was that rarity in Hong Kong, a “must-see” movie not starring Chow, Jet Li, or Jackie Chan. Johnnie To was just moving ahead, creating romantic comedies, cop dramas, and unclassifiable items like Running on Karma (2003) and Throw Down (2004). Election (2005) and Election 2 (2006) showed, in unprecedented detail, how triad societies governed themselves, and more daringly how they were still connected to mainland China. With his longtime collaborator Wai Ka-fai he went out on a limb with Mad Detective (2007), but on his own he gave us satisfying polars like Exiled (2006) and Triangle (2007) as well as lighter exercises like Sparrow (2008).

Unlike the reclusive Wong Kar-wai and Stephen Chow, To stepped into the public eye. He tried to sustain the local industry by hectoring the government, throwing his weight behind new awards, supporting student film contests. He worried, he has explained, that filmmaking in Hong Kong could collapse the way it did in Taiwan. And he kept surprising us—not least by signing arthouse demigod Jia Zhang-ke to make, of all things, a martial arts movie.

Most of those developments were in the future when we got the call from Shan.

One rainy street

Johnnie To and Shan Ding, Milkyway Image office, 2005.

A van picked us up on a rainy night and we drove far into the New Territories. Along the way Shan was explaining that he was a sort of man-of-all-work for Mr. To. I would see over the years that Shan would assist in scripting and shooting, he might step in front of the camera, and he would help execute ad campaigns. He was sometimes billed as a film’s “Production Supervisor,” which is probably as good a description as any. Because he has fluent English, he was the ideal liaison between Milkyway and the west. Shan played a central role in helping critics and festival programmers learn about Milkyway’s projects.

We arrived at a big abandoned storage facility in a grove of trees. A street set about a block long had been built, bathed in artificial rain and mist. Mr. To was presiding over things.

He greeted us warmly. I had met him briefly at a 1999 Hong Kong film festival event arranged by Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to. The festival’s Panorama section paid tribute to Milkyway’s big films of the previous year, and a seminar was held with Wai Ka-fai, Patrick Yau Tat-chi, Lau Ching-wan, and Mr. To.

But by then Planet Hong Kong was in press. Nonetheless, I came to the seminar and took notes. I hoped that some day I would write about this team’s remarkable movies.

That November night Mr. To graciously said he remembered me from the seminar. But he soon went back to work as the crew prepared for what would be a bicycle race. A bicycle race? Who’d be racing? Kristin and I turned, and I gaped. There was Lau Ching-wan.

What Chow Yun-fat was to John Woo, Lau was to To: his exemplary protagonist. Chow was virtually born in a tuxedo, but onscreen Lau projects the image of an ordinary working stiff. In To’s films he usually plays the profane, irritable, unheroic hero; or if the film has no hero, as in The Longest Nite, he becomes a glowering, implacable force.

Not tonight, though. He was as friendly as Mr. To. His English was fine and we chatted a little. For the life of me I can’t recall what we said; I was too, as the Brits say, gobsmacked. I have long known I was a fanboy at heart, but here was the embarrassing proof.

Standing next to him was Ekin Cheng Yee-kin–at that point, one of the leading jeunes premiers of Hong Kong film. He had made his career as a teen idol, particularly in the young-triads cycle known in English as the Young and Dangerous series. He was also extremely cordial.

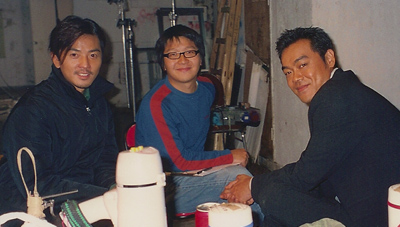

Both actors had to do a lot of waiting around between shots, of course. While we snacked on food from Styrofoam containers, there was time for pictures. Here’s one of Lau and Cheng flanking Yau Nai-hoi, Mr. To’s prolific screenwriter and later director of Eye in the Sky (2007).

We couldn’t get too close to the main set, but I did get some general shots of the crew at work. The crew filmed take after take of Lau and Cheng pedaling along the same short strip, over and over. I also got some shots of the stunt men, who were trying again and again to knock off some cars’ side mirrors. These guys take some serious spills.

Only when I saw Running Out of Time 2 was it clear that our night’s shoot, and others before and after, yielded a charming scene in which Ekin, the unnamed magician figure, taunts and exasperates Lau as detective Ho. It’s crucial because the race teaches Ho that Ekin’s mysterious cat-and-mouse game is essentially benevolent, even joyful. Staring at the set, I was impressed by how fake it looked. But on film, swathed in darkness, rain, and mist, it looks fine.

Yesterday, re-watching the movie, I enjoyed spotting the moment when we pass from the location to the set. From a shot taken on location, To cuts to a tighter shot of Lau, on the set.

Track in to Lau’s face as we hear a bike bell and Ekin whizzes by.

At Ekin’s urging, Lau grabs a bike and pursues him.

Once you see the film, you can notice how most of the shots are framed to conceal the fact that Lau and Ekin are pedaling down the same stretch over and over, sometimes in reverse directions on the set. Occasionally a changed background sign gives away the repeated takes.

Elaborate as this is set was, it’s still more economical in Hong Kong to mount such a thing than to spend nights on location to get dozens of shots. The magic of the movies, after all. And the signs enable product placement to help cover costs.

Never a man to waste a chance, Mr. To re-dresses the set a bit for Running Out of Time 2‘s cheery epilogue, when Christmas breaks out.

Just as in classical Hollywood cinema, scenes echo one another partly because it’s economical to re-use sets at different points in the movie.

This wasn’t my last encounter with Johnnie To. Shan kept in touch, and my spring visits to Hong Kong included a stopover at Milkyway headquarters. There I would run into Lorenzo Codelli, Shelly Kraicer, Todd Brown of Twitchfilm, Sabrina Baracetti of Udine’s Far East Film Fest, Grady Hendix of the New York Asian Film Festival, and other movers and shakers in film culture. Partly because of To’s promotional outreach to these tastemakers, he is much better known worldwide than he was in 2001. I managed to visit shoots for Throw Down, Exiled, and Triangle. He showed me work-in-progress versions of several films. Mr. To also sat down for interviews with me; my favorite is the one in which he went shot by shot through the “Sukiyaki” scene in A Hero Never Dies. Needless to say, I learned a lot from all these encounters.

These days I’m refurbishing my book for web publication, writing frantically while listening to Cantopop (Sammi and Faye and Gor Gor, mostly). Now I can give Milkyway its due. I’ve spent the last couple of weeks reviewing To’s oeuvre, and I’m more convinced than ever that he is one of the finest directors of the last fifteen years. Planet Hong Kong Redux will contain two lengthy sections on his films. Like all the illustrations in the new version, the stills (many from 35mm prints, not DVDs) will be in color.

As PHK Redux moves closer to online publication in mid-December, I’m mounting other items for the delectation of those discerning souls who know that Hong Kong has created one of the great traditions of film history. This week the site adds my DVD booklet essay on Mad Detective, courtesy Nick Wrigley and Masters of Cinema. And in a couple of weeks, as a run-up to PHK Redux, we’ll be putting up a gallery of celebrity snapshots I’ve taken since my first visit to Hong Kong in 1995.

Secrets

Oh, yes, what were the consequences of this evening in November 2001? Well, one was meeting a new batch of interesting people, Shan and Mr. To and Mrs. To and Martin Chappell and others. Their warm, informal hospitality constitutes one reason I come to Hong Kong every spring.

Another consequence: the conviction that I would have to write more about Hong Kong film. Having followed it since the 1970s, I thought I detected a dropoff in quality and energy in the late 90s. I wasn’t alone. The revised version of my book details how the industry went into a slump then. But the movies from Milkyway showed that you could still flourish in hard times. Seeing Mr. To’s movies made me want to stick with this tradition a little longer. So I continued to write, mostly short pieces about him, until PHK’s going out of print pushed me to update my thinking.

A third consequence of that set visit was broader and deeper. Getting to know filmmakers confirmed that I was a fanboy through and through, but I also felt it shifted me in new directions as a researcher. I’m fascinated by the practice of making movies. I still want to know, within my limited technical expertise, the tangible stuff that people do to build the images and sounds that captivate us. What tools do they use? What work routines have become standardized? What happens when technology or craft practices change?

As a graduate student, I thought that in order to understand movies we just needed to look at the screen. Although I had made some amateur films (bad ones), I failed to see that the fine grain of craft is exactly where artistry begins. By the time I started to write academic essays and books, especially The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I realized that knowing what goes on behind the screen sensitizes you to what’s there. You literally see more.

Most film academics aren’t interested in how craft can nourish artistry. In their eagerness to avoid “formalism,” they tend to neglect artistic traditions, trends, and choices. Movies are made, and the making—poeisis, as the old Greeks called it—demands concrete decisions about form and style. Filmmakers make different choices in different times and places, and we can try to analyze and explain some of those choices. As E. H. Gombrich once suggested, very simply, the artist’s key question is often: “What is there for me to do?” We need not stop there, but considering creative options and decisions is a good place to start if you want to do justice to the films, the filmmakers’ hard work, and the experiences we have as viewers.

I want to know directors’ secrets, especially the ones they don’t know they know. Planet Hong Kong was an effort to bring some of those secrets to light. I think I’ve found some more since then. Thanks to the courtesy of filmmakers like Mr. To, I’m compelled to try sharing them with you.

A fairly recent interview with Johnnie To is here. Especially interesting are his memories of growing up in Kowloon Walled City, a sort of criminal jungle. Corpses on the playground, that sort of thing.

Although the book will pay tribute to them, let me here signal two excellent online resources, now far more elaborated than when I wrote the first version of the book. Ryan Law’s Hong Kong Movie Database is indispensible for investigating people, companies, and films (detailed lists of cast and crew members). HKMDB also has a lively news section. Ross Chen’s vast and entertaining LoveHKFilm lives up to its name, with meaty reviews and news updates. There are many other fine sites, but these are the ones I’ve relied on most often. In addition, I must signal a book that came out too late for me to use; John Charles’ remarkable Hong Kong Filmography 1977-1997.

The friend whom Shan contacted was Li Cheuk-to. Since 1995 Ah-to has been my advisor, translator, editor, and host. I owe him more than I can say.

I have many other people to thank for my times in Hong Kong, and the revised PHK will do so. In the meantime, if you’re interested in Johnnie To and Milkyway, you can check my other blog entries here.

P.S. After I finished this entry there came the sad news of the death of Mr. Wong Tin-lam, a director from the classic era of Cantonese cinema. His Wild, Wild Rose (1960) is still remembered as a trail-blazer. The father of director Wong Jing, he brought a grassroots gravitas to some of the best Milkyway films, in which he was likely to play a Triad elder. Go here for more pictures and background information.

Wong Tin-lam in A Hero Never Dies.

P.P.S., 20 November: Thanks to Yvonne Teh for correcting my spelling! Check her enjoyable Hong Kong site Webs of Significance.

How to watch FANTÔMAS, and why

DB here:

He is, we’re told in the opening of the first volume, “The Genius of Crime.” Not a genius, the genius. And he doesn’t play nice.

“Fantômas.”

“What did you say?”

“I said: Fantômas.”

“And what does that mean?”

“Nothing. . . . Everything!”

“But what is it?”

“Nobody. . . . And yet it is somebody!”

“And what does the somebody do?”

“Spread terror!”

In the standard English translation, the last line sounds exceptionally scary, especially today. The original French, “Il fait peur,” is closer to “He creates fear,” but that sounds tamer in English than in French.

In whatever language, for a hundred years this catechism has proven bone-chilling. Cinephiles, crime fans, avant-garde artists, and mass audiences have found the tales anxiety-provoking, even hallucinatory. The delirious imagery and plot twists are felt to harbor a demented poetry. So the first reason to celebrate the arrival of a U. S. DVD version of Louis Feuillade’s great installment-film Fantômas (1913-1914) is that we can all have a look at what made Apollinaire and Magritte and Resnais and Robert Desnos tremble.

I confess myself of the other party. I enjoy tales of Fantômas and Dr. Gar-el-Hama (the Danish equivalent in movies of the era) and Dr. Mabuse and Haghi (of Lang’s magnificent Spione, 1928) but they don’t give me an existential frisson, or unmoor me from rationality, or make me feel the secret currents swirling through the modern city. Call me cold-blooded.

On second thought, don’t. The best-made efforts in the master-mind genre do heat my blood—but because they arouse my love of narrative invention and dazzle me with flourishes of cinematic style. The conventions of the genre, all the disguises and elaborate schemes and surprising revelations engineered by the Genius behind the scenes, the cascades of coincidence and the hairbreadth escapes, aren’t merely enjoyable in themselves. They show how little plausibility matters to storytelling. (People may say they like realism, but they’re suckers for far-fetched stories.) And in order to make the whole farrago of traps and conspiracies flow along, you need filmmakers who can hold our interest with swift pacing and ingenious narration. On many occasions, depicting virtuosity of crime has called forth virtuoso cinematic technique.

So let Fantômas make your flesh creep, if your flesh is creepward inclined. But even if it’s not, we should celebrate Louis Feuillade’s triumph in creating, in the first great era of filmmaking 1908-1918, a fine piece of cinematic storytelling. To appreciate it, we need to watch—really watch—what he’s doing.

So let Fantômas make your flesh creep, if your flesh is creepward inclined. But even if it’s not, we should celebrate Louis Feuillade’s triumph in creating, in the first great era of filmmaking 1908-1918, a fine piece of cinematic storytelling. To appreciate it, we need to watch—really watch—what he’s doing.

Thirty-two Fantômas novels by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre were published from 1911 through 1913. By the time Feuillade launched the film version in May of 1913, the book cycle was winding down; in La Fin du Fantômas (1913), the master criminal dies, at least for a while. Souvestre died in 1914, but the prodigious Allain revived the series and the villain during the 1920s.

When the films were made, Feuillade was working for Gaumont, one of the two most powerful French studios. He was head of production, overseeing other directors while turning out his own movies at a rapid clip. He signed over fifty films, mostly one-reel shorts, in 1913 alone. The Fantômas films are often thought of as a serial, but they are really long installments in a series, somewhat like our Bond and Bourne franchises. A “feature” film at the period might run fifty to seventy-five minutes. As with our franchises, there are recurring characters. The films pit police inspector Juve and the journalist Fandor against Fantômas and his accomplices, notably the treacherous but passionate Lady Beltham.

Feuillade was one of the great directors. He had a fine comic touch, not only in the shorts featuring child players like Bébé and Bout de Zan but also in farcical two-reelers like Les Millions de la bonne (The Maid’s Millions, 1913). His dramas could be powerful too, epitomized for me in the two-part feature Vendemiaire (1919) and sentimental melodramas like Les Deux Gamines (1921) and Parisette (1922). Still, he’ll probably always be most famous for his crime films like Les Vampires (1915-1916), Judex (1917), Tih Minh (1919), and of course the first of them, Fantômas.

The new video edition, which comes to us from Kino, is the third DVD release I’ve seen. The first was a French set from Gaumont in 1998, the first full year of the DVD format. The box contains a handsome booklet with background material, pictures, and an interview with Feuillade, but the intertitles aren’t translated. All subsequent releases seem to be based on the Gaumont copy used in this collection. That results in so-so picture quality, a rather haphazard score pasted together from classical pieces, and occasional distracting sounds, like birds tweeting in outdoor scenes. The UK Artificial Eye PAL release of 2006 includes a brief introduction by Kim Newman but no booklet. The original Gaumont titles are preserved, with English subtitles added.

Kino’s version unfortunately eliminates the French titles altogether, substituting English translations. Visually, however, I prefer the Kino version to the others, which on my monitors is less contrasty and heavily saturated in its tinting. Still, the Gaumont master was made in the early days of DVD authoring and could stand a complete redo. In fact, Gaumont should release many more Feuillade titles, starting of course with Tih Minh.

How best to persuade you that these movies are worth watching? I decided to concentrate on just the first episode, Fantômas (aka The Shadow of the Guillotine) as a sample of Feuillade’s artistry. Everything I analyze here is on display in later installments, sometimes more flamboyantly. The creative principles at work are explored in greater detail in my books On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light (which has a long chapter on Feuillade), as well as in several items on this site.

1. Get ready for preposterousness. The film, based on the first book in the series, rearranges the novel’s plot order considerably and simply excises the first half’s major line of action, a hideous murder. Even with cuts, though, the film asks us to believe that after Fantômas, disguised as one Gurn, is put into prison, he can get his wealthy mistress to bribe a guard to let him out for a while. And that during their rendezvous, the couple can replace the murderer with an actor who happens to be playing Gurn in a stage show based on the case. And that the actor, having been drugged, can’t recall his identity.

There’s at least one glaring plot gap in the film. Juve solves the mystery of the disappearance of Lord Beltham when he discovers his body in a steamer trunk about to be sent overseas. The novel explains his rather tenuous line of reasoning (Chapter 11), but the film simply shows him arriving at Gurn’s apartment and examining the fatal trunk. Presumably, though, Feuillade could afford to be elliptical. Some of the audience would have known the novels and could fill in bits that seem enigmatic to us.

The film’s climax is in fact less implausible than the novel’s, perhaps out of considerations of good taste. In the novel, the actor substituted for Gurn actually dies at the guillotine; the authorities realize their mistake only when they see the head smeared with greasepaint. In the film, Juve interrogates the dazed Valgrand and astounds other officials by revealing that he isn’t the prisoner they had locked up. Even then, it seems unlikely that nobody but Juve would have noticed the prisoner’s wig and false mustache.

Far-fetchedness is built into the genre, so the problem is handling. Craziness must be treated matter-of-factly, and Feuillade’s sober technique takes all the wild developments in its stride. Nothing fazes Fantômas, or our director.

2. Accept the conventions of “pre-classical” cinema. Film historians often consider the years from 1907 to 1917 as leading up to the sort of cinematic storytelling we know, replete with lots of cutting, close-ups, and camera movements. A film like Fantômas exemplifies some tendencies of French cinema in this period. There is relatively little crosscutting among lines of action. The film uses no shot/ reverse-shot or extended passages of close-ups. Typically a cut is used to enlarge printed matter, like a news story or a business card, or to emphasize crucial details. Here is Juve discovering a clue, Gurn’s hat, in Lady Beltham’s parlor.

Interior sets were usually designed to be seen from only one camera orientation. In exteriors, we get somewhat freer cutting, presumably because real surroundings don’t confine the camera as much as a fake set does.

In this transitional era, some habits of earlier years hang on: the fairly distant framings, the fairly obvious sets, and the occasional glances at the audience.

You can almost sense stylistic change happening during such moments. In earlier films, characters constantly looked at the audience, but in Fantômas a character’s eyes pause fractionally on us before drifting away, as if the look to the camera simply signified thinking, not an effort to share a response.

Similarly, Feuillade seems to be sensing the need for varying his camera positions in a way that we’d find in later cinema. Consider his handling of the Royal-Palace Hotel.

To show the elevator entry on different floors he reuses the same set. This is motivated realistically, since hotels look more or less the same on different floors. But if the camera were framing every elevator shot exactly the same way, we would have weird jump cuts when cutting from floor to floor, and the use of the same set would be more apparent. So Feuillade not only re-labels each landing at the top of the frame, but he shifts his camera position slightly, moving the framing rightward in the string of shots showing the elevator descending to the ground floor.

The slight shifts in framing reinforce the sense that we’re on different floors.

3. Watch the back door. Deep space is common in exteriors from the beginning of cinema, even in Lumière shorts, but by the early 1910s filmmakers were starting to replace relatively flat interior sets with ones that give their actors more playing space in depth. Here, for example, is a Bohemian party from Feuillade’s Une Nuit agitée of 1908. The parlor and the action are shot in a flat, lateral way, and people enter the room from the right or left.

Compare the depth in the interiors of many scenes in Fantômas of five years later.

Once sets become deeper, the rear door becomes very handy for entrances and exits, and Feuillade is a master of using it. It’s usually fairly close to the center, but in the actor Valgrand’s dressing room, it’s off to the side.

The rear door prepares us for upcoming action and provides another center of compositional interest—advantages that don’t come up when actors enter from the sides of the frame. The door also allows people to be shown overhearing what is going on in the foreground.

4. It isn’t theatre! There’s a common belief that the cinema of this period simply records performances as if on a stage. But that’s not true. As most of these shots show, the camera is usually closer than any spectator would be to a stage play. Feuillade reminds us of what a real stage performance would look like when Lady Beltham sees the actor Valgrand in the dramatization of Gurn’s capture. (It’s reminiscent of the stage-like set in Une Nuit agitée above.)

Valgrand’s gestures are broad ones, suitable to being seen from a great distance. But in the surrounding story, the performances are much more subdued. Feuillade demanded dry, quick acting from his players, and their gestures aren’t extravagant. (Juve usually jams his hands in his overcoat pockets.) Instead, Feuillade keeps his actors busy with small props. Here, as Fandor writes a story, Juve is brooding on his failure to capture his adversary. Before he’s finished one cigarette he’s already rolling another, and he lights up the new one end to end.

Crucially, theatrical space is geometrically very different from cinematic space, as I’ve argued in several other entries. A shot like this wouldn’t work onstage because spectators sitting to the right or the left would have their sightlines blocked by furniture.

Because the camera slices out a wedge of space in depth, actors can be carefully arranged in dynamically developing compositions that would not be visible on the stage. When the doped-up Valgrand is brought to be questioned by the police officials, we first see him through the rear doorway–a view that wouldn’t be shared by many spectators in a theatre performance.

The dazed actor is questioned, with Juve emerging slowly out of the welter of authorities behind him.

Needless to say, the earliest phases of this shot would be unintelligible on a stage; for most members of the audience, the other actors would block Juve. Recall as well that this was accomplished in an era when directors and cinematographers could not look through the lens to see exactly how the configuration would appear onscreen.

5. Develop an appreciation of complex staging. In a cinema relying on analytical editing, our attention is driven to one item or another through cutting and closer views. By contrast, the director of “tableau cinema,” as this 1910s style is sometimes called, must shift the actors around the sets in ways that call our attention to what’s important at each moment. In the course of the scene, the director must also try to maintain some pictorial harmony on the two-dimensional plane of the screen. Shots are subtly balanced, then unbalanced, then rebalanced, all in the service of story intelligibility.

As we’d expect, depth can play a key role here. Take the simple moment when Lady Beltham’s butler announces the arrival of Nibet, the prison guard whom she bribes. Lady Beltham turns at the sound, rises, and moves to the settee.

As Nibet enters, Lady Beltham returns to her writing desk. This is our old friend the Cross, refreshing the image by having the actors trade placement in the frame.

The same choreography of balancing, unbalancing, and rebalancing can be found when the characters aren’t arranged in depth. The scene of Lady Beltham and Gurn drugging Valgrand plays out laterally. Gurn hides behind a curtain, and our awareness of his presence there colors the whole scene. But because Valgrand will be on the settee, for some while Lady Beltham’s position at her tea table would make an appearance by Gurn compositionally clumsy.

As the drug takes effect, Lady Beltham moves to Valgrand’s side. This gesture of concern unbalances the composition–until Gurn peeps out to rebalance it.

Lady Beltham’s stare at him makes sure we notice his presence. Soon the police arrive to return “Gurn” to his cell.

Again Lady Beltham moves to the right, and again it’s motivated: She wants to make sure the cops have gone. But that movement clears a space for Gurn, i.e. Fantômas, to reveal himself in triumph just as Lady Beltham relaxes in relief.

The synchronization demanded of the actors, in pacing and placement, is considerable, and of course the director has to coordinate everything. Feuillade, directing with shouts and a drillmaster’s whistle, drove his actors through each long-take scene. Turn off the music occasionally and imagine him calling out instructions to them.

These examples, and many others, gainsay David Kalat’s curious claim in the Kino commentary that Feuillade’s work exhibits an “anti-style” that doesn’t present stories “cinematically”–because he doesn’t exploit cutting and changes of camera position.

The camera has been plopped down perfunctorily in front of a set in which the actors meander around within the frame without any sense of composition. In several scenes the actors nonchalantly turn their backs on the audience completely. Only rarely does a shot appear in which the actors seem positioned in front of the camera for any specific pictorial effect. The shots ramble on with hardly any change of point of view until the scene ends and a new one takes its place (Disc 1, 11:54-12:20).

Actually, here and in other works, Feuillade’s staging is quite precise. I doubt that many directors today could block fixed shots as fluidly as he does; sustained, intricate staging in this sense is an almost lost art. Hou Hsiao-hsien, in his films up through Flowers of Shanghai, might be the last great exponent of this technique.

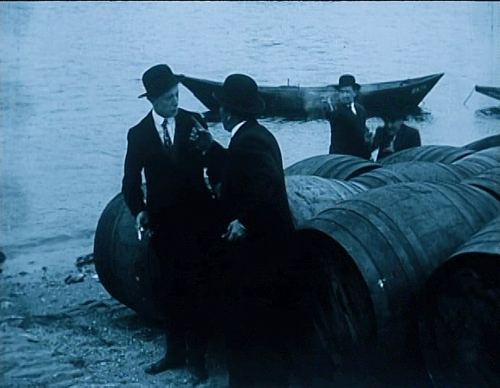

We find the same principles at work in later Fantômas episodes. Some scenes have greater pictorial splendor than the ones I’ve considered; many aficionados believe that the essence of the series is on display in the second installment, Juve contre Fantômas. Certainly it has crazier plot twists. (I got through a whole blog without mentioning Juve’s python-repelling suit, below.)

Granted, it’s hard to study the films as they’re unfolding. That’s partly because Feuillade guides our eye so subtly that we get caught up in the plot. Still, re-viewing can help us spot the fine points. With this DVD set, you have at least five and a half hours of fun before you.

In the lurid tales of Allain and Souvestre, Feuillade found sensational material. He had fine actors. He had luminous prewar Paris as a backdrop. And he had at his fingertips all the resources of tableau cinema. The whole mixture creates a lively cinematic experience. Watching films like Fantômas and Ingeborg Holm and The Mysterious X and many others from 1913, we can still be bowled over by their exquisitely modulated storytelling. If Feuillade is less baroque than Bauer and less poignant than Sjöström, he’s also more brisk, laconic, and playful. Call him the Hawks of the tableau tradition. Thanks to this new release, more Americans will have a chance to enjoy his exuberant creativity.

And they can have all the frissons they want.

Searching “tableau” in our blog entries will offer many further examples of what I’m discussing here. Our 1913 entryoffers an overview of what Feuillade’s contemporaries were up to.

The Kino set includes two other Feuillade films, The Nativity (1910) and The Dwarf (1912). These are better transfers than the main attractions, and make for some interesting comparisons with his artistic strategies in Fantômas. There’s also a short documentary on Feuillade’s career, adapted from the Gaumont box set Le Cinéma premier, which contains many Feuillade titles. Other Feuillade films are available on US DVD: Les Vampires, in an out-of-print Image set; Judex, from Flicker Alley; and various items in the Kino package Gaumont Treasures, 1897-1913. That set, a selection from the Gaumont box, includes The Agonie of Byzance, made the same year as the first installments of Fantômas.

As times changed, Feuillade adopted editing, sometimes in rather flashy forms. For examples, go to my chapter on Feuillade in Figures and here. Essays by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs show how performance style adjusted to the tableau tradition. Charlie Keil’s Early American Cinema in Transition traces the somewhat differing developments in U. S. cinema of the period.

For all things Fantômas, visit the Fantômas Lives website. There’s also the very helpful Encyclopédie de Fantômas (1981), self-published by the mysterious ALFU. If you want to know the percentage of deaths by defenestration in the oeuvre (6.8 %), this is the book for you. David Kalat offers a wide-ranging survey of Fantômas’ influence on modern art and popular culture in “The Long Arm of Fantômas,” in Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives, ed. Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin (MIT Press, 2009), 211-224.

Francis Lacassin has written prolifically on both Fantômas and Feuillade. The arch criminal earns a chapter in Lacassin’s À la recherche de l’empire caché (Julliard, 1991), while his Louis Feuillade: Maître des lions et des vampires (Bordas, 1995) remains the essential work on the director.

Juve contre Fantômas.