Archive for the 'Directors: Oliveira' Category

Il Cinema Ritrovato: More and more

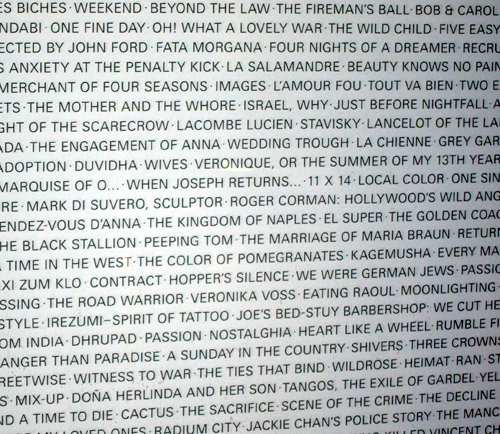

Il Cinema Ritrovato Book Fair (photograph Margherita Caprilli).

Kristin here:

I mentioned in my entry on the African thread at this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato that I filled in blank spaces in my program with a miscellany of intriguing films. Here are some of those films I saw, and others that David saw.

O Pão (1959)

Manoel de Oliveira’s first film, the gorgeous black-and-white documentary short, Douro, Faina Fluvial, was released in 1931. His last, Um Século de Energia, another documentary short, came out in 2015, the year of his death aged 106 (as did Visita ou Memórias e Confissões, a deliberately posthumous legacy film shot in 1982). That’s an 84-year career. I doubt any other filmmaker can claim as much.

Initially that career proceeded in fits and starts. He made more documentary shorts in the 1930s and then a black-and-white feature, Aniki-Boko (1942), during the war under an authoritarian regime. After the war he could not find funding and decided to study color filmmaking in Germany. During the 1950s he applied his resulting expertise to two documentaries: O Pintor e a Cidad (“The Painter and the City,” 1956) and O Pão (Bread). A beautiful print of the latter was shown in this year’s Ritrovati e Restaurati thread. It was to be his last film before he turned to feature filmmaking, though he never entirely gave up documentaries, particularly near the end of his life.

This hour-long film slowly follows the entire progress of bread, from wheat-fields to milling to baking to consumption. The images, whether in field or factory, are lovely, showing that Oliveira had indeed learned a great deal about color.

There is no voice-over narration, even during a lengthy scene in a large mill where technicians perform mysterious tests on samples of flour. The slow progression creates a soothing, almost mesmeric tone. Only toward the end does some social criticism emerge. A hungry urchin stealthily retrieves a roll dropped by a shopper, only to have it snatched away by a little street thug. Clearly bread, despite the lyricism of its production, is not for everyone.

Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Avval, Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Duvvum (1979)

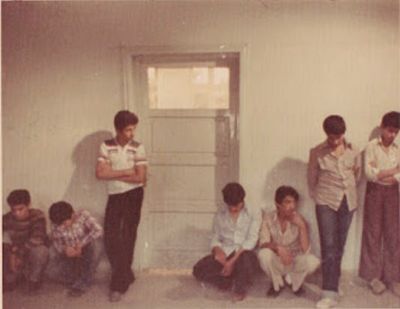

Another must-see was Abbas Kiarostami’s early film, First Case, Second Case, also presented in the rediscovered-and-restored thread. Like Oliveira, Kiarostami began in documentary work. This remarkable film was started before the 1979 Iranian Revolution and finished after it–and then banned.

The film’s beginning rather resembles other Kiarostami openings, with a simple scene in a classroom. A teacher drawing the anatomy of an ear on a blackboard is interrupted by a knocking noise caused by one of his students. No one confesses or reveals who caused the noise, and the teacher suspends seven of the boys, who spend the next days in the hall outside the classroom.

This scene is revealed to be a 16mm film being shown to a succession of teachers, government officials, religious leaders, and the fathers of some of the boys. In the latter cases, some variant of the framing above is shown, with an arrow pointing to the son of the father being interviewed. Unseen, Kiarostami asks them the same question: did the boys do right in refusing to reveal who disrupted the class? Some of these interviewees became key figure in the Islamic Revolution. (Jason Sanders’ program notes for a screening of the film provide some information about this historical context.)

This “documentary” has of course been carefully staged. A page from Kiarostami’s script reveals how he designed the passing days of the boys’ suspension, with different ones standing or sitting each time. The illustration is from Ritrovato programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht’s blog entry on the film, where he credits First Case, Second Case with introducing the interview technique into the director’s work.

This first case shows the boys maintaining their refusal to identify the culprit. In a new scene, the second case, an alternative outcome shows one of the boys naming the guilty classmate to his teacher. Again, Kiarostami interviews many of the same people as to whether they believe the boy’s decision can be morally justified.

If not as charming as some of Kiarostami’s later work, First Case, Second Case contains a familiar combination of complexity and simplicity, as well as a fascination with people telling their own versions of events.

The film has been picked up by Janus in the USA, which should mean that it becomes available from Criterion on Blu-ray and/or its streaming service, The Criterion Channel.

Twelve O’Clock High (1949)

In recent years, Il Cinema Ritrovato has featured the films of a major Hollywood director as one of its main threads. This year it was Henry King. I managed to miss nearly all of his films. In part I feared that, since the auteur du jour is always one of the the more popular items in the program, the screenings would be crowded. Word of mouth suggested that they were.

Still, I had an afternoon free, and I wanted to guarantee myself a good seat for Varda par Agnès, showing later in the day. I went to an earlier screening in the same theater, and I was glad I did. Twelve O’Clock High is an impressive and entertaining film, if not an outright masterpiece.

Fitting into David’s set of innovations typical of the 1940s, the action is enclosed by a framing situation. A man we eventually discover was an American officer posted in England during World War II bicycles out into the countryside and visits the derelict remains of the military airport where he served. (Above, played by Dean Jagger in a role that won him a best-supporting-actor Oscar).

For a long time the story concentrates on General Frank Savage (Gregory Peck), who takes over command of an underperforming bomber unit in the same air station we saw at the beginning. He proves an absolute stickler for discipline, initially alienating the pilots he commands. Eventually he wins their respect, of course, and he learns to unbend a bit.

Eventually a series of air battles occur, with some very impressive and genuine combat footage, including aerial views of bombs exploding on their German targets. The film was presented in a nearly pristine 35mm print, which certainly contributed to my pleasure at having ended up at that screening somewhat by chance.

Faubourg Montmartre (1931)

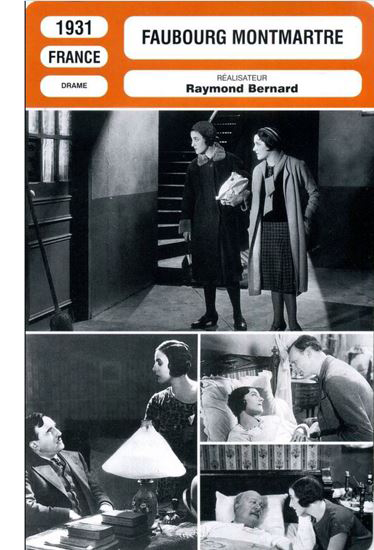

I definitely planned from the start to see this film. I very much admire director Raymond Bernard’s 1932 World War I drama Wooden Crosses, his next feature after Faubourg Montmartre. Indeed, I had done a video on it for The Criterion Channel (“Observations on Film Art” #16 “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses“)

While a slighter film than Wooden Crosses, Faubourg Montmartre is quite stylish and technically impressive, considering that it was Bernard’s first sound film. In it he abandons his concentration during the silent era on historical epics (his best-known being The Miracle of the Wolves, from 1924).

Here he tackles a melodrama in a contemporary setting, centering around Ginette, a somewhat naive young working-class woman, played by popular star Gaby Morlay. She and her older sister Céline live and work in the titular district of Paris, the disreputable area of cheap entertainment and brothels. Céline works as a prostitute but tries to protect Ginette from such a life. Becoming more dependent on drugs, however, she nearly dupes Ginette into following her into prostitution.

Despite its grim setting, the film has many light moments, mostly provided by the amiable Morlay. It also contains some impressive musical numbers, one a variety number by Florelle and a café song about prostitution by Odette Barencey.

The film was yet another in the festival’s Ritrovati and Restaurati thread.

Georges Franju

There was an unaccustomed focus on documentaries this year, which presumably was the occasion for devoting a small thread to Franju. Of the thirteen shorts which he made or at least is tentatively credited with (most of them commissioned documentaries), eleven were shown. Judex, his fiction feature paying homage to the serial of the same name by Louis Feuillade, was also on the program.

I tried to see all the Franju shorts, since only Le Sang des bêtes (above) and Hôtel des Invalides are well-known in the US. The prints shown ranged widely in quality, some being in 35mm and some 16mm. En passant par la Lorraine was almost unwatchable, though most of the rest were in varying degrees acceptable.

The most interesting revelations were perhaps Mon chien (1955), a melancholy narrative based on the common habit of people abandoning their pets in the countryside. The amazingly callous parents of the little heroine dump her beloved German shepherd in the woods on their way to a vacation spot. The film follows the faithful animal’s trek home, only to find a locked house and a dog-catcher waiting. An empty cage signals that the animal was euthanized, with the voiceover of the girl calling forlornly for her pet. The other was Les poussières (1954), a lyrical survey of many kinds of dust generated in the world, ending in a strong anti-pollution message.

It was a pleasure to see this body of work brought together, but the screenings also demonstrate the pressing need to restore many of these films.

A Gabin tribute

DB here (with films I saw in boldface):

Jean Gabin has become emblematic of French cinema from the 1930s and after, so the several films devoted to him were welcome. Programmer Edward Waintrop included the classic Pépé le Moko (1936) but correctly assumed he didn’t have to show this crowd La Grande Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), and Le Jour se Lève (1939). Edward’s catalog entry wisely emphasized how much Gabin owed to Julien Duvivier, an underrated director who helped the young actor find starring roles.

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

In her book on popular song in French cinema, our colleague Kelley Conway has written a superb analysis of Cœur de Lilas, and you can find a clip of Gabin’s big musical number here. Director Anatole Litvak handles his performance in a long tracking shot that keeps our attention fastened on Gabin’s half-scornful, half-boastful mug as he spits out lines about his girlfriend’s bedroom calisthenics (“The rubber kid. . . She dislocates you”).

Gabin plays the third point of a love triangle in Cœur de Lilas, but he’s somewhat more central to the lesser-known Du Haut en Bas (1933), a sort of network narrative that reminds us that The Crime of M. Lange (1936) isn’t the only film tracing the tangled passions in a courtyard community. More easygoing here but still a force to be reckoned with, Gabin plays a footballer with his eye on an aspiring teacher forced to work as a maid. Other plotlines, including Michel Simon’s raffish wooing of his landlady, intermingle in this thoroughly agreeable movie by the great G. W. Pabst.

A generous sampling of Gabin’s later career included La Marie du Port (1949), Le Plaisir (1951), Maigret tend un piège (1957), and the brutal Simenon adaptation Le Chat (1970), the first film I saw on my first visit to Paris. En Cas de Malheur (1957), an efficient plunge into sex and crime by Autant-Lara, features Gabin as a prestigious but dodgy lawyer drawn to the pouting self-regard of Brigitte Bardot. In youth and age, as a sort of French Spencer Tracy, Gabin could exude both relaxed joie de vivre and stolid menace. An icon, as we say.

Americana, urban and rural

State Fair (1933).

Speaking of Spencer Tracy, it was a pleasure to see this Milwaukee native in a long-neglected racketeer drama. Quick Millions (released May 1931) arrived in the middle of the first big gangster cycle and was overshadowed by two Warners hits, Little Caesar (January 1931) and The Public Enemy (May 1931). As part of Dave Kehr’s welcome second Fox cycle, Quick Millions had its own pungent force.

It traces the familiar trajectory of a working stiff, trucker “Bugs” Raymond, who claws his way to the top of the mob. Thanks to blackmail and crooked labor maneuvers (“The brain is a muscle,” he tells his moll), he winds up triggering a spate of gangland killings that eventually swallows him up.

Quick Millions was noticed as one of the earliest films to find a smart tempo for talkies, one that relies less on long speeches than snappy scenes delivering one point apiece. The passage of time is signaled by changing license plates, and the ending is a shrug, shoving Bugs’ death offscreen and giving him none of the tragic flourishes of Little Rico or Tom Powers. For almost every scene, the little-known director Roland Brown finds an unexpected twist in visuals or performance . Who else would film a sidling George Raft jazz dance from a high angle and then supply inserts of his legs, from behind no less?

Fox found more success with a folksy Grand Hotel variant based on the popular novel State Fair (1932). Henry King’s 1933 film was planned as an “all-star” vehicle, and it did boast Will Rogers, Janet Gaynor, and Lew Ayres. An Iowa family heads to the fair, aiming for blue ribbons in pickle preserving and hog-fattening. The son has a surprisingly carnal affair with a trapeze artist, while the daughter meets a roguish reporter who makes her rethink her engagement to a hick back home. State Fair‘s script gives the plot a happier ending than the book did, but that’s not necessarily a problem; we want these kind souls to enjoy a bit of glory.

Henry King became famous for rustic realism with Tol’able David (1921), a model for Soviet filmmakers, and Ehsan Khoshbakht’s King retrospective reminded us that he worked this vein a long time. From 1915 Twin Kiddies (a Marie Osborne vehicle) to Wait ‘Till the Sun Shines, Nellie (1952), this loyal Fox craftsman showed himself, like Clarence Brown at MGM, an adaptable director with an unpretentious gift for celebrating small-town life.

Still more, more…

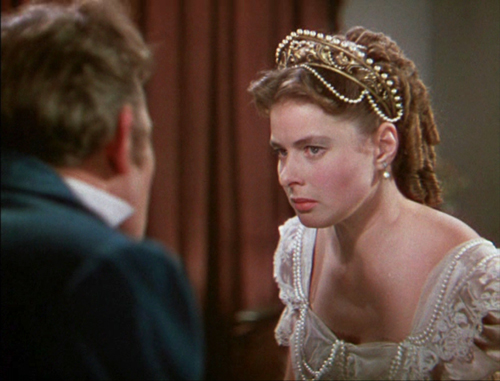

Under Capricorn (1949).

I could go on about other films, such as Zigomar: Peau d’Anguille (“Zigomar, the Eelskin,” 1912), Victorin Jasset’s forerunner of Feuillade’s delirious master-criminal sagas. (In one episode, an elephant’s trunk fastidiously picks the lock on a circus wagon and drags away a strongbox.) Our next entry will spend a little time looking at a neat Genina film from 1919. In the meantime, I’ll sign off by mentioning two other high points.

The pretty Academy IB-Tech print of Under Capricorn (1949) made me like the film quite a bit better than previous viewings. As ever, one high point was La Bergman’s virtuoso soliloquy admitting her guilt. Any other director of the time would have reenacted the crime in a flashback, but, in the shadow of Rope (1948), Hitchcock makes her squeeze out her confession in a ravishing single-take monologue running almost eight minutes.

Its power comes partly from the fact that the framing withholds the facial response of the man who loves her. He’s slowly understanding the depth of her devotion to her husband during penal servitude. “How did you live all those years?” he murmurs. How’d you think? Her glance flicks over him, in both guilt and defiance (above).

Finally, no film gave me more pure pleasure than the restoration of Boetticher’s Ride Lonesome (1959). Sony archivist Grover Crisp explained that the original prints had all been made from the camera negative (!) and so he had no internegatives or fine-grain masters to work from. Nevertheless, this digital version, made in 4K with wetgate scanning, looked superb.

I tend to judge Boetticher westerns by the strength of the villains, meaning that Seven Men from Now (Lee Marvin) and The Tall T (Richard Boone) sit at the top of my heap, but it’s hard to resist the laconic dialogue Burt Kennedy supplied everybody in Ride Lonesome. And the antagonists facing Randolph Scott here–Lee Van Cleef (brief but unforgettable), Pernell Roberts (the good-bad rascal), and sweet-natured dimwit James Coburn (on his way to rangy knife-wielding in The Magnificent Seven)–add up pretty powerfully. Against them stands Scott as vengeance-driven Brigade, an unyielding chunk of sweating mahogany.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator. Thanks also to Dave Kehr, Grover Crisp, Mike Pogorzelski, and Geoffrey O’Brien for talk about many of the classics on display.

The entire Ritrovato ’19 catalogue, with full credits and essays, is online here. There are also videos of many events, including master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Quick Millions was remembered several years after its release for “the rapid rhythm of its continuity.” See Janet Graves, “Joining Sight and Sound,” The New York Times (29 November 1936), X4.

John Bailey’s introduction to Under Capricorn included a revealing short explaining the Technicolor dye-transfer process. For further information there’s the remarkable George Eastman House Technicolor research site and of course James Layton and David Pierce’s superb book The Dawn of Technicolor.

Kristin discusses Kiarostami’s landscape techniques in a Criterion Channel Observations entry. In American Dharma, discussed by David here, Errol Morris reveals that Twelve O’Clock High was an inspiration for Steve Bannon’s political career.

The Ritrovato program notes credit Fréhal as the working-class singer in Faubourg Monmartre, but Kelley Conway’s Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in French Film (linked above) identifies her as Odette Barencey, a lesser-known chanteuse of the period who resembled Fréhal.

Opening shot of Ride Lonesome (1959).

Il Cinema Ritrovato: A final entry

The courtyard outside the Cineteca di Bologna, during Il Cinema Ritrovato.

DB here:

Some initial figures are in, and they’re fairly stupendous.

There were about 85,000 admissions to all screenings of this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, which ended ten days ago. That figure includes the big public shows on the Piazza Maggiore, but the day-in, day-out screenings were heavily attended as well. There were 2500 or so festival passes sold. Assuming that those people stayed for four of the festival’s eight days and attended four shows a day, we can surmise that at a minimum 40,000 of overall admissions came from dedicated cinephiles surging from venue to venue. And of course many passholders stayed seven or eight days and squeezed in more than four viewings on each one.

Broiling heat—one day approached 100 degrees Fahrenheit—didn’t seem to keep many away from the films, panels, book talks, and other events that crowded the schedule. Between 9 AM and 1 PM, each two-hour block offered six to eight choices, and the afternoon blocks, running from 2:30 to about 8 PM offered even more. Now that the festival has another space, a nearby university auditorium fitted for DCP projection, a whole new column of events was slotted in. Below, a bit of the queue for the Isabella Rossellini interview in the auditorium.

Next year, planners are hoping to add screenings at a renovated 100-year-old theatre on the Maggiore. There seems no doubt that the Cannes of Classic Cinema will get even bigger.

For the first time, I felt the pace was a bit rushed. Getting together with old friends was somewhat harder than before, unless you came a day or so early. (Even then, there were tempting Maggiore evening shows.) But the atmosphere was still easygoing. The courtyard of the Cineteca was an island of steamy relaxation, boasting more tables than in past years. The tent cafe provided snacks and drinks for those who simply decided not to be obsessive. Even I stopped and sat down, twice.

Word is out. A new wave of young film lovers has discovered Ritrovato. What had been dominated by hip (or hip-replaced) baby boomers was now teeming with students. The festival has added a Kids section and another devoted to older teens, and it was a pleasure to see them winding through the corridors of the Cineteca. The World Press has finally woken up too. The Guardian ran a rapturous encomium. Loyal blog sites such as Photogénie provided extensive coverage.

Just speaking for us, this was the first year Kristin and I had almost no time to blog during the event. Hence this, the last of our catch-up entries. (Click back for the earlier ones.) And I will leave out a lot.

All in favor of film, raise your hands

Has everything been said about digital cinema and its differences from photochemical cinema? Maybe so. Nonetheless, the two panels I visited on the subject raised a lot of intriguing points, in quite different formats.

The first session compared 35mm prints with digital restorations. Through clever maneuvering, the Ritrovato boffins were able to switch back and forth between versions as both were running, and the results were pretty compelling. Schawn Belston of Twentieth Century Fox provided a sample of Warlock, a twenty-year old print. It was contrasty but had saturated color; this was the sort of image I remember seeing in theatres. The digital restoration, a work in progress, was paler, with sharper edges, more solid-black shadows, and a more pastel color design. Pretty Poison was a much newer print, on Vision stock, and looked fine, as did the DCP.

Grover Crisp of Sony brought a Kubrick-approved print of Dr. Strangelove, considered best-quality in 1990s. He ran it in tandem with the recent 4K restoration managed by Cineric. The difference was very striking. For black-and-white, at least, the DCP seemed to me to have all the better of it. Kubrick, a major otaku on matters photographic, would I think have approved.

Further proof of the Crisp-Sony finesse was available in the utterly dazzling DCP we saw of Cover Girl (1944) on the big Arlecchino screen. I was surprised to find some of my circle disdaining this movie, but I think it’s wonderful. It seems to me a rough draft for many of Gene Kelly’s MGM pictures, from the trio boy-girl-stooge we get in Singin’ in the Rain (with Phil Silvers as Donald O’Connor) to the mind-bending doppelganger dance that looks forward to Anchors Aweigh and Jerry the Mouse. I also like the clever motifs of feet and faces, and the flashbacks, and …well, I must stop, because I expect to use Cover Girl as a major example in my still-unfinished book on Hollywood in the 1940s. Suffice it to say that I have never seen a better DCP rendering of Technicolor than was on display in Grover’s new edition.

Davide Pozzi rounded out the session with a pairwise comparison of different versions of Rocco and His Brothers. A vintage print from the camera negative had been vinegared, so the shots had rippling focus; the DCP restoration was fairly sharp and bright. This was a real work of reclamation.

The panelists agreed on a lot. Don’t try to banish grain; film is grainy. Don’t expect to match everything. No two prints ever looked alike anyhow, and variations among screens, lamps, and other exhibition factors don’t let us capture a pristine original experience. Because of the advances of digital restoration, there are new frustrations. Archivists are aware that older restorations may not look good today, while cinephiles who forgive scratches on “vintage” 35mm copies howl if a restoration doesn’t look smooth as silk.

Film has many futures. Pick one.

Serge Bromberg introducing the Lobster Films anniversary program, which included several “faux Lumières.”

Another panel, “The Future of Film” (let’s ban this as a title, shall we?), was less focused but more provocative. No fewer than fifteen critics, archivists, manufacturers, and filmmakers gathered before a standing-room crowd to discuss the prospects for the photochemical medium formerly known as film.

The panel’s speakers worked in shifts, three at a time. Everybody was lucid and brief. Some general points:

On the manufacturing front, Kodak and Orwo are committed to producing motion-picture stock. Christian Richter of Kodak noted that in 2006 his firm produced 11.8 billion feet of motion-picture film, while last year it produced only 450 million feet. The demand may be plateauing, but it’s too soon to be sure. The crucial problem may be the absence of labs, although boutique labs are starting to appear.

Some filmmakers, such as Gabe Klinger, consider film an essential part of their aesthetic. Alexander Payne prefers to shoot on film, but more important is film projection. He restated his view that “flicker will always be superior to glow.” By contrast, archivist Grover Crisp proposed that the standard of film projection had sunk so low that he prefers to see digital presentations, although those too can be substandard.

Some archives are preserving on film recent movies, including those shot digitally. Sony does, as does the CNC. Eric Le Roy reported that all French films receiving subsidy must deposit a print and the negative there, even if the project originated digitally. Mike Pogorzelski of the Academy archive spoke of the ongoing “Film to Film” effort, begun in 2012.

More generally, two archivists argued that the future of film lay in museums. José Manuel Costa of the Portuguese film archive argued that the basic principle had to be a respect for the nature of the medium. Cinema has changed, but it has existed in a specific technological environment since the nineteenth century, and it’s the mission of a film museum to retain that technology as long as possible. Accordingly, a film should be shown in the format in which it was made.

Belgian film archivist Nicola Mazzanti (on left above, with Pietro Marcello and Alexander Payne) seemed in accord. He remarked, in the wake of the earlier session, that digital treatment, or film restoration generally, can’t duplicate tinting, toning, stencil color, Technicolor, and other older processes. The originals are what they are—imperfect—but that imperfection is inherent in their material history. More acutely, the world outside the archive is entirely digital, so it will be a big task to keep analog alive. It will take money. And no European archive’s budget equals the cost of a single season of La Scala.

Scott Foundas, who chaired the sessions with easy good humor, indicated that perhaps the state of play was this. Digital capture and storage would not wholly replace film. By now film is recognized as distinct and worth its own attention. It’s going to exist alongside digital media for some time to come, although in niches and in more rarefied forms than before; like vinyl records.

Bologna, it became clear, is one of those places where film will continue to flourish. Fifty percent of screenings this year were analog, and the programmers included showings of Vertigo, The Heroes of Telemark, All That Heaven Allows, and other titles on “vintage” prints from earlier eras. Audiences packed in to see them and cheered.

What they saw, we must see

With all the talk of film’s enduring powers, two screenings reminded me of the power of photochemical recording as a record of history, both en masse and individual.

German Concentration Camps Factual Survey was overseen by Sidney Bernstein and involved several skilled filmmakers, including Hitchcock. It was designed to be shown to the German people as a record of what they had ignored over the last dozen years. But it remained unfinished when it was shelved in 1945.

In recent years the surviving reels have been shown occasionally under the title Memory of the Camps. In 2008 several staff at London’s Imperial War Museum began to restore the original and fill out the final reel. The filmmakers added a new recording of the original commentary, previously not attached to the footage.

Friends of Andy Warhol often commented that he used his ever-present Polaroid to keep his distance from his surroundings. You wonder if a similar strategy didn’t insulate, to some minimal degree, the American, British, and Russian cameramen who filmed the liberation of the camps. Their images show shriveled corpses covering the ground, flung into pits, shoveled into heaps. Spindly survivors move like ghostly marionettes. When I saw the first images of the bland camp officials smoking and chatting under guard, I immediately wondered: What self-control it must have taken not to have killed these men on sight.

The film is structured as a sort of anti-Grand Tour, starting in Bergen-Belsen, where SS officers seem genuinely annoyed at being forced to clear out the dead. The film moves eastward, guiding us by maps, to end in the abandoned Nazi extermination camps built in German-occupied Poland. Here shoe brushes, spectacles, and children’s toys fill warehouses. The names of German companies proudly adorn ovens.

One of the film’s main points, apparently suggested by Hitchcock, is the fact that the camps existed very close to population centers. Did the people celebrating Oktoberfest in Munich ever think of Dachau, half an hour away by train? Did the people breathing the mountain air of Ebensee spare a thought for the camp nearby? Arriving Allies insisted that people from surrounding towns be brought to witness what they had ignored. In the footage, men, women, and children file by the carnage.

Some seem moved, but eerie shots show town elders standing stiff and impassive before heaps of bodies.

Toby Haggith, one of the film’s restorers, was on hand for a follow-up session, something really demanded by the intensity of the experience. He answered questions with great seriousness and eloquence. He explained that the restoration team had decided to leave in the film’s original errors, based on contemporary reports of the size or uses of certain camps, as well as the film’s avoidance of focusing on Jewish victims. The film stresses the Nazis’ crimes against humanity at large, an emphasis, as Haggith pointed out, in tune with the United Nations initiative of the moment. “The very historicity of the film is what seizes us.”

Godard has suggested that there must be footage of the day-to-day running of the camps. Would the society that devised Agfa film and Arriflex cameras have failed to document the industrial-scale slaughter of which the Reich was so proud? Were there no amateur cineastes among the SS-men leading comfortable lives in their cottages? Was there no Leni Riefenstahl to cheerfully lend credibility to these charnel houses? Even if such footage exists, German Concentration Camps Factual Survey will serve as an unforgettable reminder that humans have a terrifying gift for brutality, and for ignoring horrors enacted right beside them.

Many doubts, much faith

Visita ou Memórias e Confissões.

In 1982, financial setbacks forced the Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira to sell the house he had lived in for forty years. Before leaving, he decided to record his affection for the place. The result, Visita ou Memórias e Confissões was the quietest film I saw at Ritrovato. It was also one of the best.

We start at the gateway, coming in as if guests. But who owns the voices we hear? The murmuring man and woman who seem to be our surrogates passing along the path? We never see them as they enter the magnificently curvilinear house. But is it right to say they? Although we hear two voices, we hear only one person’s footsteps. The somewhat whimsical uncertainty that haunts so many Oliveira films is summoned up here by the simplest of means.

Eventually Oliveira greets us, standing in his study before his typewriter, and he explains some of the house’s history. He also runs some footage on a 16mm projector that coaxes him into discussing death, women, virginity, and sanctity. “I’m a man of many doubts and much faith.” Occasionally we hear the couple whispering as we coast past art objects and family pictures.

Oliveira tells us of his 1963 arrest while making Rite of Spring and his 1974 conflict with workers in his family’s factory—a tumultuous event that, we learn rather late, is the cause of his financial distress. These revelations come in the midst of a fascinating account of his family, accompanied by a tribute to his wife, to whom the film is dedicated. Individual history and social history blend in his recollections and the flow of visual memorabilia.

The spectral visitors glide out with us, and the film that Oliveira has been showing halts, leaving us a blaring white frame. According to his wishes, Visita wasn’t shown until after his death. Perhaps in 1982 he expected that event to come rather soon; he was seventy-three, after all.

He couldn’t have known, surely, that he would live another thirty-three years and make twenty-four more films. As José Manuel Costa pointed out, the great director wanted the film to be shown posthumously not as a final boast, but rather a wry, modest memoir of an exceptionally full life. By turns ironic and confessional, Oliveira’s testament demonstrates that we can be moved by a soft-spoken, patient peeling back of layers of the past.

Of course it was shown on film.

Kristin and I thank the many staff members who make Ritrovato such a wonderful experience. Special thanks to Gian Luca Farinelli, Guy Borlée, and Cecilia Cenciarelli. We are particularly grateful to Marcella Natale for her many moments of assistance, including giving us preliminary attendance figures.

German Concentration Camps Factual Survey will play several film festivals and public venues during the rest of the year and will eventually be distributed on DVD. Night Will Fall (2014), André Singer’s documentary on the making and restoration of the original film, is already available.

P.S. 31 July: Danny Kasman has an illuminating interview with Toby Haggith on the Factual Survey, along with important background information, at Cineaste.

VIFF 2013 finale: The Bold and the Beautiful, sometimes together

Gebo and the Shadow (2012).

DB here:

I’m a little late catching up with our viewings at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year (it ended on the 11th), but I did want to signal some of the best things we didn’t squeeze into earlier entries. Kristin and I also want to pay tribute to one of the biggest moving forces behind the event.

Safe but not sorry

Like Father, Like Son (2013).

Among other goals, film festivals aim to provide a safe space for nonconformist filmmaking. Programmers need to find the next new thing—art cinema is as driven by novelty as Hollywood is—and they encourage films that push boundaries. What isn’t so often recognized is that sometimes festivals show filmmakers who were once quite artistically daring backing off a bit from their more radical impulses. Part of this is probably age and maturity; part of it reflects the fact that apart from daring novelties, festivals also showcase works that might cross over to wider audiences. And of course festivals will present recent works by the most distinguished filmmakers, almost regardless of the programmers’ hunches about their quality. Some sectors of the audience want to see the latest Hou or Kiarostami or Assayas.

Koreeda Hirokazu was thirty-three when Mabarosi (1995) won a prize at Venice. It’s an austerely beautiful work, presenting a disquieting family drama in very long, static takes. Once the action shifts to a seacoast village, distant shots render slowly-changing illumination playing over landscapes, while the tension between husband and wife is built out of small gestures. For example, we learn that the forlorn wife is waiting in the bus stop only when a little bit of her comes to light.

Lest this seem just fancy playing around, Koreeda occasionally used his long takes to build suspense. Yumiko’s new husband has been drinking. While he’s out of the room, she opens a drawer to retrieve the bike bell she keeps in memory of her first husband, killed in a traffic accident. The second husband returns unexpectedly, and drunkenly collapses on the table beside her. But when she lifts her hands out of her lap, she inadvertently lets the bell tinkle a little.

The sound rouses him and he asks what she’s holding. She raises her head at last and they begin a quarrel about each one’s motives in marrying the other.

Eventually he will shift woozily to the other side of the table and notice what has been sitting quietly in the frame all along: the still-open drawer on the far right.

In later films, from After Life (1998) to I Wish (2011), Koreeda’s visual design became less reliant on just-noticeable changes within a placid shot. The images have become less demanding, and more extroverted narrative lines carry stronger sentiment. The films remain admirable in their ingenious plotting and mixture of humor and pathos—which is to say, they are committed to that “cinema of quality” that makes movies exportable.

That commitment is firmly in place in Like Father, Like Son. Koreeda, now fifty-one, dares almost nothing stylistically or narratively. Yet every scene leaves a discernible tang of emotion, and his light touch assures that things never lapse into histrionics. If Nobody Knows (2004) and I Wish (2011) are his “children films,” this is, like Still Walking (2008), a movie about being a parent.

The plot has a fairy-tale premise: Babies switched at birth. Our viewpoint is aligned with the well-to-do parents and particularly the ambitious executive Ryota. When he finds that six-year-old Keita isn’t his birth son, he insists on swapping the boy into the household of the happy-go-lucky working-class Saiki family. In exchange, Ryota and his wife take in the boy that Saikis have raised as their own.

As the film proceeds, our view widens to create a welter of comparisons—two ways of being six years old, tough discipline versus easygoing parenting, what rich people take for granted and what poor people can’t, a solicitous mother versus one who can’t spare time for coddling. Koreeda is faultless in measuring the reactions of all involved. Ryota’s wife slips into quiet depression. Saiki is an affable father with a childish streak, but he also looks forward to suing the hospital. Saiki’s wife, a no-nonsense woman with two other kids to care for, is a mixture of toughness and maternal affection. As in a Renoir film, everyone has his reasons, and the drama depends on a process of adjustment stretching across many months. Climaxes become muted, though no less powerful for that.

A smile and a tear: the Shochiku studio formula, enunciated by Kido Shiro back in the 1920s, remains in force here. Simple motifs, such as images stored on a camera’s photo card, hark back to all those affectionate picture-taking scenes in Ozu’s classics. The whole is shot with a conventional polish—coverage through long lenses, straightforward scene dissection—that’s far from the strict, slightly chilly look of Maborosi.

It’s impossible to dislike this warm, meticulously carpentered film. Koreeda has proven himself a master of humanistic filmmaking, and I admire what he’s done (as these entries indicate). Those of us who’ve been following his career for nearly twenty years, however, may feel a little disappointed that he hasn’t tried to stretch his horizons a bit more.

Like Father, Like Son was rewarded with the Jury Prize at this year’s Cannes festival. Steven Spielberg, jury president, has acquired remake rights for DreamWorks.

Action, blunt or besotted

A Touch of Sin (2013).

Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin offers a comparable adjustment to broader tastes. It’s far less forbidding than his early features Platform (2000), Unknown Pleasures (2002), and The World (2004). Somewhat like Koreeda, Jia’s earliest fiction films embraced a long-take aesthetic that tended to keep the characters’ situations framed in a broad context. (His documentaries, like the remarkable 2001 In Public, were somewhat different.) Jia proceeded to breach the boundary between documentary and fiction in Still Life (2007), Useless (2007), and 24 City (2008). With A Touch of Sin, Jia takes on a twisting, violent network narrative that is as shocking as Koreeda’s duplex story is ingratiating.

We start with a villager who fumes at the corruption in his town and carries out a vendetta against its rulers. Another story centers on a receptionist who is taken for a prostitute and abused by massage-parlor customers. A third protagonist is an uneducated young man floating among factory jobs who turns his frustration inward. Threading through these is a drifter who shoots muggers from his motorcycle and later takes up purse-snatching.

The sense of inequity and exploitation that ripples through Still Life and 24 City now explodes into rage. Rich men (one played by Jia) puff cigars while strutting through a brothel, businessmen casually exploit their mistresses and buy off politicians, and injustices are settled with fists, knives, pistols and shotguns. “I was motivated by anger,” Jia says. “These are people who feel they have no other option but violence.”

Like Koreeda, Jia has had recourse to some of the casual long-lens coverage we find in many contemporary movies, but certain shots gather weight through his signature long takes–especially shots holding on brooding characters. In all, we get a dread-filled panorama, with bursts of violence staged and filmed with an impact that reminds you how sanitized contemporary action scenes are.

For more, see Manohla Dargis’ rich Times review of the film.

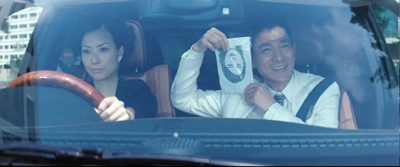

After the painstaking (and pain-giving) dynamics of Drug War (our entry is here), one of Johnnie To Kei-fung’s best recent films, it’s wholly typical that he does something outrageous. His work with Wai Ka-fai at their Milkyway company has always alternated unforgiving crime films of rarefied tenor with sweet and wacko romantic comedies that assure solid returns. But seldom have they combined the two tendencies into something as screechingly peculiar as The Blind Detective.

Initially the investigator, inexplicably named Johnston, seems to be a brother to Bun, the mad detective of To and Wai’s 2007 film. He insists on having the crime reenacted so as to intuit the perp’s identity. But since Johnston is blind, somebody else must tumble down stairs, get whacked on the head, and generally suffer severe pain in the name of the law. Ready to sacrifice herself to Johnston’s mission is officer Ho, a spry and game young woman with a crush on him.

Johnston and Ho are trying to find what happened to a schoolgirl who went missing ten years before. But this account makes the movie seem more linear than it is. Johnston makes his living from reward money, and he’s also dedicated to finding a dancing teacher he fell in love with when he had sight. So the search for Minnie is constantly deflected. Yet the digressions end up, mostly through Johnston’s inexplicable flashes of imagination, carrying them back to their main quest.

This episodic plot, or rather two plots, stretched to 130 minutes (making this the longest Milkyway release, I believe), yields something like a Hong Kong comedy of the 1980s, where slapstick, gore, and non-sequitur scenes are stitched together by the flimsiest of pretexts. The tone careens from farce (not often very funny to Westerners) to grim salaciousness. Johnston’s intuitive leaps are represented by blue-tinted fantasies that show him gliding through a scene at the moment of the murder, or assembling a gaggle of victims to declaim their stories. Characters are ever on the verge of exploding in anger or aggression, and between the big scenes Ho and Johnston dance tangos and gnaw their way through steaks, fish, and other delicacies.

Once more, the congenitally fabulous Andy Lau Tak-wah is accompanied by Sammi Cheng as his love interest, and the two ham it up as gleefully as in Love on a Diet (2001). (They were more subdued in my favorite of the cycle, Needing You…, 1999.) This is, in short, a real Hong Kong popular movie. It brought in US $2.0 million in the territory, and $33 million on the Mainland, about the same as Monsters University. If it keeps Milkyway in business, how can I object?

For a discerning take on The Blind Detective, see Kozo’s review at LoveHKFilm.

JLG in your lap

Kristin and I were keenly looking forward to 3 x 3D, the portmanteau film collecting stereoscopic shorts by Peter Greenaway, Edgar Pêra, and Jean-Luc Godard. Kristin found the Greenaway episode–sort of his version of Russian Ark, taking the camera through the labyrinth of a ducal palace and showing off elaborate digital effects–fairly appealing. But for us the Godard was the main attraction, and he didn’t disappoint.

At one level, The Three Disasters reverts to his characteristic collage of found footage, film stills, scrawled overwriting, and insistent voice-over. (Is it my imagination or does the the 83-year-old filmmaker’s croak sound increasingly like that of Alpha 60?) The montage is sometimes over-explicit, as when Charlie Chaplin is juxtaposed with Hitler. There’s a funny passage of portraits of one-eyed directors (Lang, Ford, Ray), as if to reassert the primacy of classical monocular cinema. At other points, things get obscure, as when Eisenstein’s plea for Jewish causes during World War II is followed by shots from The Lady from Shanghai. But this is the Godard of Histoire(s) du cinema, piling up impressions that beg for acolytes to identify the images and find associations among them.

Frankly, this side of Godard doesn’t grab me as much as his pseudo-, quasi-, more-or-less-narrative features. But in 3D his dispersive poetic musings take on a new vitality. He doesn’t retrofit old movie clips and still photos for 3D. Instead he superimposes them, making one cloudy plane drift over another. He can also, more forcefully, present his signature numerals and intertitles in a new way–by having them pound out of the screen and hang rigidly in front of the image.

There are also some 3D shots made specifically for the film, most consisting of handheld shots that shift around a park, a medical complex, and, of course, a media studio. The very title of Godard’s film, punning on 3D as a technical disaster, as well as a throw of the dice (dés), suggests his ambivalence toward the technology. “The digital,” his voice declares, “will be a dictatorship,” but perhaps it will never abolish chance.

As usual, Godard has fun with simple equipment. He frankly shows us his camera rig, two Canon DSLRs lashed together side by side, one upside down. By shooting them in a mirror and shifting focus, he manages to make each lens pop and recede disconcertingly, as if Escher had gone 3D. This shot alone should inspire DIY filmmakers everywhere. So too should the one-slate credits. Whereas Greenaway’s segment lists scores of names in its credit roll, Godard’s lists only four, alphabetically. I can’t wait for the feature, Farewell to Language. (Trailer here.)

Brian Clark has an informative review of The Three Disasters at twitchfilm.

Looking at the fourth wall

In nineteenth-century Portugal, the elderly Gebo ekes out a living as a company accountant. His wife Doroteia and his daughter-in-law Sofia wait with him for the return of João, a rebellious ne’er-do-well. Gebo feeds Doroteia’s illusions about their son, who has likely become an outlaw. When João returns after eight years away, he throws the family into turmoil and becomes fixated on the cash that his father safeguards for the firm.

After World War II, André Bazin noticed that many filmmakers were starting to take a creative approach to adapting plays. Olivier’s Henry IV, Welles’ Macbeth and Othello, Dreyer’s Day of Wrath, Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles, Melville’s Les Enfants terribles, Hitchcock’s Rope, and Wyler’s Little Foxes and Detective Story, are far from the “photographed theatre” that some critics feared would dominate talking pictures. For decades Manoel de Oliveira has explored avenues of theatrical adaptation that have led us to some daring destinations. Gebo and the Shadow, drawn from a 1923 play by the Portuguese Raúl Brandão, is a powerful recent example, and possibly the best film I saw at VIFF this year.

After the credits show João loitering on the docks, the film confines the action almost wholly to the parlor of Gebo’s family home. Early on we see the street outside through a window, but most of the film concentrates on the characters gathered around the room’s central table. On stage, we can imagine the table at the center and the major characters assembling around it but leaving one side clear, facing the audience–in effect, accepting the convention of the invisible fourth wall that gives us access to the space.

As the still above suggests, it seems initially that Oliveira is playing up this convention, putting us into the stage space and setting the fourth wall behind us. Very soon, though, we’re inserted between the players, so that we see the other side of this lantern-lit playing space.

For the most part, the first stretch of conversations and soliloquys among Gebo, Doroteia, and Sofia are played out in this planimetric, clothesline layout. So is the late-night arrival of the vagrant João, coming to sit opposite his father and laughing wildly. This shot corresponds to the end of the play’s first act.

On the next day, when Gebo and his family receive some friends, the table is sliced in half.

The effect is to redouble the sense of proscenium space, presenting two planimetric arrays that always keep one “behind” us.

Like other chamber-plays-on-film (Dreyer’s Master of the House, Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder), Gebo varies its spatial premises slightly to incorporate other possibilities. In the stretch corresponding to the second act of the play, the angle on the table changes twice, once to present the split table-scene above, and later, to the climactic moment when João joins Sofia and contemplates breaking open the strongbox.

Sometimes we’re shown the window and other walls, usually presented when characters leave one shot and enter another. The constructive editing helps us tie together zones of the room that aren’t ever given in an all-encompassing master shot. And the camera never moves, not even to reframe characters’ gestures.

In previous films, Oliveira has played with the ambiguities of who’s looking where. (See, for instance, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Hair Girl and The Strange Case of Angelica.) After a mysterious prologue involving João, a ravishing image presents Sofia watching at the window, then moving aside to reveal Doroteia behind her (and behind us).

As often happens, the start of a film sets up an internal norm; it teaches us how to watch it. This movie starts with a lesson in optical geometry. Sofia watches the street, goes out to scan for Gebo’s arrival, then watches Doroteia from outside the window before coming back in and resuming her position at the window. As the shot develops, we can see Doroteia lighting a lamp and reflected in the window against the distant doorway.

When Sofia walks out of the shot, Oliveira’s camera lingers on the window, in which we can still see Doroteia turning her head to watch Sofia’s coming to her. This is the shot, imperfectly reproduced, that’s at the top of today’s entry. The image isn’t far from the gently insistent changes of Koreeda’s Maborosi. This film about a shadow starts with an image of a spectre.

Constructive editing often relies on a glance offscreen, so here he can play with minute differences of eye direction. Occasionally the actors look directly out at us. But when the table is halved, as above, the eyelines get very oblique, with opposite characters looking in the same direction.

In the third act, the frontal and planimetric grouping around the table returns. Gebo has searched fruitlessly for João and has returned to take the consequences of his son’s theft.

Oliveira’s adaptation omits the play’s fourth act, when the family is reunited three years later. His version leaves the family suspended in a freeze-frame, haunted by the ghostly son who has betrayed their trust. This dramatic climax is also a visual one, with sunlight for the first time spilling into the chilly, lamplit parlor and its inhabitants startled, as if they shared João’s guilt.

Perhaps more than the other films in this entry, Jebo and the Shadow shows why we need film festivals. Oliveira’s purified experiment demands a lot from the audience, but it repays our efforts. It’s at once an engrossing story and an exciting exercise in what cinema can still do. Note as well that I have managed to get through a discussion of Oliveira’s film without mentioning his age.

For more on the film, see Francisco Ferreira’s very helpful essay in Cinema Scope.

Finally, Alan Franey has announced his departure from the job of Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival. He’s going out on a high note. This year’s edition was a solid success, and its spread to venues around town seems to have brought a wider audience. For twenty-six years Alan has led the process of making the festival one of the best in North America. He has helped give it a unique identity as home to Canadian cinema, documentaries on the arts and the environment, and outstanding current Asian cinema.

Finally, Alan Franey has announced his departure from the job of Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival. He’s going out on a high note. This year’s edition was a solid success, and its spread to venues around town seems to have brought a wider audience. For twenty-six years Alan has led the process of making the festival one of the best in North America. He has helped give it a unique identity as home to Canadian cinema, documentaries on the arts and the environment, and outstanding current Asian cinema.

For Kristin and me, he has been a wonderful friend and good-humored company. Alan’s deep commitment to great cinema has shown in his recruitment of colleagues, his skilful defusing of potential crises (most recently the shift to digital projection), and his genial, almost Zen, good nature. Fortunately for the festival, he will remain as a programmer. He deserves our lasting thanks.

Good news for US audiences on some of these titles: Sundance Selects will distribute Like Father, Like Son, while Kino Lorber has wisely acquired rights for A Touch of Sin. Gebo and the Shadow is available on an English-subtitled DVD from Fnac and Amazon.fr. It’s a very dark movie, and in order to make the frames readable here, I’ve had to brighten them a bit. These images don’t do justice to what I saw in the VIFF screening, or even to what the fairly decent DVD looks like.

For more on planimetric staging of the sort we find in Gebo and Maborosi, see entries here and here and here. It’s a common resource of modern cinema, and directors utilize it in a variety of ways.

Les trois désastres (2013).

Venues and visions

Vitrine outside future quarters of the Film Society of Lincoln Center (detail).

DB here:

During our month in NYC, we didn’t visit only art museums (although KT was at the Met a great deal). We also, no surprise, hit some of the city’s premiere movie spots. The places were often as impressive as the films, and all deserve the support of cinephiles both local and visiting. Herewith, a recap of our visits.

Fun things happen on your way through the Forum

Mike Maggiore, in the lobby of Film Forum.

Film Forum, running since 1970, has established itself as an outstanding venue for new releases and classics. It has done heroic work over the years. I stopped by to see my old Wisconsin friend Mike Maggiore, one of FF’s programmers, and met his colleagues, including Karen Cooper, a legend in US film culture. They had just recently had a remarkable triple-night string of visitors: Scorsese introducing his new documentary Public Speaking, Jerry Schatzberg with Scarecrow, and Paul Schrader with a fresh print of Diary of a Country Priest. The current FF program, running on three screens, is here and it’s very rich.

Uncle Boonmee will have hit FF by the time you read this. Chris Ware’s gorgeous poster decorates the Forum lobby.

The gem of Astoria

Under MoMI projection, Rachael Rakes (Assistant Film Curator), David Schwartz (Chief Curator), KT, Ethan de Seife (Professor, Hofstra).

The refurbished Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria is a thing of great beauty. Family-friendly, with lots of hands-on kid activities, it also offers a bounty to the cinephile.

For one thing, it has a superb screening theatre. We sampled it when MoMI screened a pretty print of King Hu’s The Valiant Ones (1975). Kristin and I were happy to see our old favorite again.

The same hall gave us a restoration of Manoel de Oliveira’s Doomed Love (1978). The movie, 4 ½ hours long, was shot in 16mm for television. It frankly acknowledges its novelistic source by including stretches of letters and florid declamation (“I will be dead to all men, except you, Father!”), as well as a plot turning on forbidden love and oppressive social relations. This is a world of parlors, convents, trusty servants, candlelit rooms, barred windows, and lovers who actually waste away. The title could apply to virtually every character, down to the maidservant who adores our protagonist and vows, “When I see I am not needed, I will end my life.” The affair draws others into its downward spiral, leaving the hero plenty of time to reflect on his misery and the pain he has inflicted on others.

The plot is quite engrossing in the manner of a triple-decker novel. That makes it all the more surprising that we get no Viscontian spectacle or even the plush upholstery of a Masterpiece Theatre episode. The presentation is rather dry and detached. I wondered if Ruiz’s recent Mysteries of Lisbon, drawn from another novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, was in effect a reply to Oliveira’s film. By comparison with Ruiz’s sparkling compositions and glissando flashbacks, Doomed Love looks reticent and austere.

The austerity is heightened by a self-conscious stylization. The music is aggressively modern, and the lengthy takes (the average shot runs about a minute) are often shot with the low, straight-on camera reminiscent of early cinema.The film begins with a partial view of a door opening, inviting us into the story world, but obliquely. The film closes with a hand lifting a bundle of love letters from the sea and a voice-over (Oliveira’s) explaining how the novel came to be written. The images provide as overt a marking of a narrative’s beginning and its end as you could ask for, and one completely in keeping with the film’s balance between respect for artifice and its concern to let compromised passions leak through.

MoMI also hosts a splendid exhibition of media technology. One floor is a wonderland of cameras, sound rigs, printers, and projectors of all sorts, from film to TV and beyond. One favorite among many: A Mitchell VistaVision camera from 1954. It’s a funny-looking thing, but it took very crisp pictures. The horizontal film transport allowed larger and sharper images than the vertically-run formats that were normal for 35mm.

There are also displays devoted to screenplays, make-up, hairdressing, and special effects. I was especially taken with the finely detailed miniature for the Tyrell corporation building in Blade Runner.

In all, MoMI deserves all the praise it has gotten after its reopening. Rochelle Slovin, the founding director of the museum, started in 1981 and is retiring this week. She can be proud of what she and her colleagues have accomplished.

Jaywalking down Broadway

Wundkanal (Thomas Harlan, 1984).

Then there’s Lincoln Center, another long-time shrine of cinephilia. Like MoMI, the Film Society is in the process of building. The new complex will house theatres, a café, and a flexible lobby space. It’s scheduled to open in late spring.

The Film Society’s František Vlácil retrospective early in our stay brought this little-known filmmaker to my attention. I had seen only his best-known item, Marketa Lazarova (1967), and that quite a while back. So I was happy to catch his charming early short, Glass Skies (1958), and three features.

Vlácil mastered both filmic poetry and prose. The White Dove (1960) is a simple, lyrical story of two young people who never meet: a girl living in a beachside town and a wheelchair-bound boy in the city. Alternating sequences show them brought together by the homing pigeon that the girl sends out. The boy in a moment of thoughtless cruelty shoots the pigeon with his air rifle. Soon, with the help of an artist living in the same apartment house, he nurses the bird back to health. The film is richly shot in crisp, wide-angle black-and-white, and Vlácil exploits eyeballish imagery to create links between the girl’s seaside milieu and the artist’s Chagall-like paintings.

Like most filmmakers moving from the 1960s to the 1970s and from black and white to color, Vlácil recalibrated his visual design. Smoke in the Potato Fields (1976) gets your attention from the start with its disconcerting cutting during an airport departure. Laconic and elliptical, shot with long lenses and long takes, it tells an understated story of a middle-aged doctor moving to a small-town clinic. We get a cross-section of the townsfolk, from ambulance driver and gravedigger to censorious nurse and an unhappy married couple. The central drama concerns the doctor’s care for a tomboyish girl who gets pregnant and considers an abortion.

Shadows of a Hot Summer (1977), set in 1947 and shortly before the Communist takeover of the Ukraine, is more conventionally gripping. A farm family is held prisoner by rapacious resistance fighters. The taciturn father has no allies among the locals, who seem to resent his prosperity, and he dares not call attention to his plight. As in a Boetticher film, the hero plays his hand judiciously, mostly passive but carefully picking the battles he can win. The final sequence, precipitated when the marauders find him hoarding shotgun shells, is a taut, suspenseful exercise in action cinema. Shadows of a Hot Summer has daring stretches of silence and an unsettling score, along with discreet zoom shots typical of the period worldwide. These installments in the Vlácil retrospective show that we nonspecialists still probably underestimate the range of artistry that could be achieved in the apparently inhospitable atmosphere of Communist Eastern Europe.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

I’m a big fan (at a distance) of the Chauvet caves and their Ice Age imagery, so Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), a 3D tour of the site, was right up my alley. The film turned out to be a strong argument for 3D (as Kristin anticipated), since it lacked that sense of cardboard-cutout planes you usually get and really brought out volumes. The tigers, bison, and other wondrous creatures seemed to bulge and ripple across the walls.

The biggest revelation the Film Comment program held for me was the double bill of Thomas Harlan’s Wundkanal (Gunwound, 1984) and Robert Kramer’s Notre Nazii (Our Nazi, 1984). Wundkanal was made by Thomas Harlan as part of his crusade to expose the bad faith of postwar Germany, where many former Nazis held positions of power. Harlan’s father was the Nazi filmmaker Veit Harlan, and as Kent Jones pointed out in his illuminating introduction, the son seems to have taken upon himself the burden of guilt that his father should have felt.

Wundkanal proposes that a terrorist gang has kidnapped the respectable citizen Dr. Seibert, interrogated him about his murderous past, recorded the sessions on videotape, and eventually staged some of their own suicides as part of the exercise. Dr. S. is played by Alfred Filbert–himself a Nazi let out of prison for medical reasons. The whole production, then, becomes both a vision of Germany’s blindness to history and a trap for a man whom Thomas Harlan suggests has gotten off far too easily. “A new idea: to use the real criminal, to deceive him and convince him it was a film about him.”

Filmed by the great Henri Alekan, it is a phantasmagoria. We are in a sunless bunker jammed with old photos, thermos jugs, automatic pistols, video clips from a Harlan film, and other detritus: a sort of chamber-play version of a Syberberg no-man’s land. Questioned by offscreen interrogators, Dr. S. admits to his crimes plaintively. The hallucinatory quality of the exercise is enhanced by sound cuts that split a sentence into bits (sometimes clear and close, sometimes filtered through speakers) and a drifting camera that may start on Dr. S. but then wanders across the litter to end on a video image of Dr. S. testifying in another session, at which point the sound of that session may take over. In one passage, the camera tours the room and picks up several bits of Dr. S.’s testimony, in the real space and in several video monitors crowding the area.

Kramer’s Our Nazi is in a way a making-of for Wundkanal, but it’s also a powerful film in its own right. Acting as his own cameraman for the first time, Kramer (director of the classic militant films The Edge, Ice, and Milestones) takes us behind the scenes to show Thomas Harlan’s obsessions and to expose Filbert more directly than Wundkanal does. Harlan talks of the fatal love he had for his father, reflecting that the old man’s charm finally withered in the face of his inhuman complicity with the Reich. Intercut with this soliloquy are shots of Filbert being made up for his video scenes, as he talks of his dueling scars and his youth: “All the ambitious men became Nazis.”

Our Nazi gives us two disturbing confrontations, one with Kramer sitting Filbert down and charging him with crimes against humanity, the other more prolonged and painful. Harlan and the crew encircle their star and hurl accusations at him. This scene, glimpsed and abstracted in Wundkanal, pulls the viewer in different directions as the feeble old man tries to escape Harlan’s relentless recitation of Filbert’s war crimes. In the discussion with Kent Jones after the screenings, Paul McIsaac rightly called the Kramer film a demonstration of the concreteness that direct cinema can yield. Shot in Hi-8, Our Nazi counterbalances the abstract, somewhat detached artifice on display in Wundkanal. Kramer dwells on unexpected details, such as Alekan hesitating to autograph a souvenir production photo for old Filbert. The two movies need to be seen together because they engage in a crosstalk that yields provocatively different information, emotions, and cinematic resources.

Our month in New York went by all too fast. We seldom visit the city these days; I’m in Hong Kong more often than Manhattan. Our trip brought back memories of my undergrad visits from Albany in the 1960s (packing four films into a day-trip) and, during the 1970s, doing dissertation research and visiting friends and teaching for a semester at NYU. It also allowed me to get back in touch with some of my oldest friends, like Rich Acceta-Evans from junior-high days. And the trip reminded me of what a cosmopolitan film culture is like, with institutions like these and still others (Anthology Film Archives, MoMA, etc.) braving tough times to bring the right movies to lucky audiences.

Apart from those named above, I want to thank the friends we met with during our stay. Scott Foundas was particularly helpful on this entry. I gave talks at various venues, so I’m grateful to Malcolm Turvey of Sarah Lawrence College, to the NYU Film Studies faculty, and to Patrick Hogan at the University of Connecticut–Storrs. Special thanks to Ken Smith and Joanna Lee for arranging a visit to the Museum of Chinese in America for a discussion of Planet Hong Kong.

Speaking of Planet Hong Kong, I discuss The Valiant Ones in Chapter 8 there, as well as in the essay “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” in Poetics of Cinema. For a sensitive examination of Doomed Love, go to Tativille.

Some films in the Film Society’s Vlácil retrospective are available on DVD from Facets Multimedia. Wundkanal and Our Nazi have been issued on a single DVD edition with English subtitles, and it can be found on the Edition Filmmuseum site. Every film studies and filmmaking department should order it, I believe. See also “Truth or Consequences,” Kent Jones’ essay in Film Comment 46, 2 (May/ June 2010), 48-53, from which I’ve taken the Harlan quotation. Jones discusses other films, including Christoph Hübner’s 2007 study of Thomas Harlan, Wandersplitter, which is also available on a Filmmuseum disc. Thomas Harlan is one of the main interviewees in the documentary Kristin recently wrote about, Harlan: Im Schatten von Jud Süss.

For more coverage of the “Film Comment Selects” series, see R. Emmett Sweeney’s review on the Movie Morlocks site, with particularly discerning remarks on I Wish I Knew. Jesse Cataldo provides sharp commentary on Wundkanal at The House Next Door.

Alfred Filbert, confronted with the tattooed arm of an Auschwitz survivor (Our Nazi).