Archive for June 2021

What you see is what you guess

The Castle Island Case (1937).

DB here:

In the 1920s and 1930s, stories of mystery and detection became hugely popular in Anglophone countries. Britain’s “Golden Age” of whodunits, launched by Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers, was rivaled by the emergence of American hardboiled detection, personified by Dashiell Hammett and other writers for the pulp Black Mask. Some of the detectives, such as Philo Vance and (alas) Ellery Queen, are largely forgotten today, but others remain towering figures of popular culture. Surprisingly, new Sherlock Holmes stories were still appearing in the 1920s. In addition, there emerged Hercule Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey, Charlie Chan, Sam Spade, Nick and Nora Charles, Nero Wolfe, Philip Marlowe, and Perry Mason (recently revised in a noir version for streaming). Fiction, film, comic strips, and radio all disseminated their adventures. Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys were aimed at the kids.

Amid this vast 0utput, writers needed to differentiate their work. The search for gimmicks was on, and a few were, as we’d say now, a little interactive. Since the classic detective plots centered on puzzles, publishers added games and playful ancillaries to their books.

Some novels were published with the last chapters sealed, daring buyers to resist curiosity and return the book for a refund. A novel (The Long Green Gaze, 1925) might tuck clues into crossword puzzles (another 1920s fad) that the reader had to solve. Books came packaged with jigsaw puzzles (The Jig-Saw Puzzle Murder, 1933; Murder of the Only Witness, 1934). “Murder dossiers” like File on Bolitho Blane (aka Murder in Miami, 1936) assembled facsimile documents accompanied by matchsticks, strands of hair, bloodstained scraps of fabric, and other physical clues. The party game of Murder, in which guests were assigned roles of victim, culprit, witnesses, and detectives, became a craze and was, naturally, incorporated into novels (Hide in the Dark, 1929).

Some novels were published with the last chapters sealed, daring buyers to resist curiosity and return the book for a refund. A novel (The Long Green Gaze, 1925) might tuck clues into crossword puzzles (another 1920s fad) that the reader had to solve. Books came packaged with jigsaw puzzles (The Jig-Saw Puzzle Murder, 1933; Murder of the Only Witness, 1934). “Murder dossiers” like File on Bolitho Blane (aka Murder in Miami, 1936) assembled facsimile documents accompanied by matchsticks, strands of hair, bloodstained scraps of fabric, and other physical clues. The party game of Murder, in which guests were assigned roles of victim, culprit, witnesses, and detectives, became a craze and was, naturally, incorporated into novels (Hide in the Dark, 1929).

The most outrageous of these extramural activities was Cain’s Jawbone (1934). The 100-page story purports to be a mystery novel whose whose pages were accidentally printed and bound out of order. There is, the reader is assured, only one correct sequence, although “the narrator’s mind may flit occasionally backwards and forwards in the modern manner.” The publisher offered a prize to the first reader who could submit the correct ordering–and, not incidentally, name both the murderer(s) and the victim(s). Only two people hit on the answer, which still remains unknown to the public.

Even quite well-known writers joined in. The original editions of Sayers’ Five Red Herrings (1931) left a page blank so that the reader could jot down a guess at what Lord Peter asked the police to find at the murder scene. Sayers was quite proud of “this little stunt,” and floated the possibility of printing the missing passage in a sealed page at the end of the book. She also wrote a Lord Peter story that invited the reader to solve a rather recondite crossword. Q. Patrick composed a murder dossier, The File on Claudia Cragge (1938).

Less immersive but still pretty interesting was my topic of today. I think it coaxes us to think about how pictures and text can interact, and how a book can borrow film techniques. In addition, it has enough weird touches to make it a remnant of a period in desperate search of storytelling novelty. You know, like ours.

More highly seasoned than most

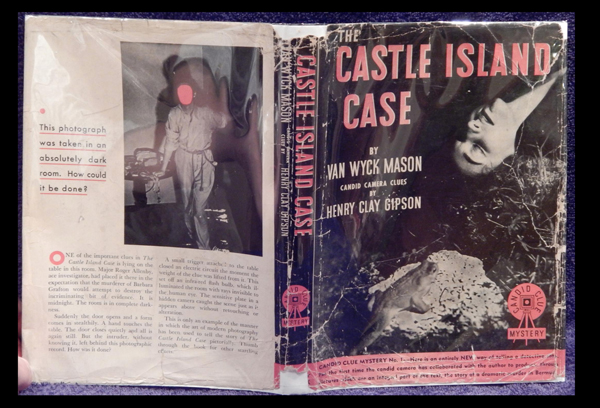

With The Castle Island Case (published September 1937) a fairly famous author, Van Wyck Mason, introduced what he considered “a brand-new method of telling a mystery story.” That method involved accompanying the novel with staged photographs of the characters, clues, and crime scenes. Mason insisted that he and photographer Henry Clay Gipson came up with the idea before the first murder dossier (1936) and before Look magazine’s “Photocrime” series, which began running in June of 1937.

Novels had long been illustrated; our undying conception of Holmes owes a good deal to Sidney Paget’s vivid drawings in the original stories. And comic books, which had begun telling long-form stories in the 1930s, showed that pictures (helped out by verbiage) could sustain plots. But photography changes the status of the image. Mason believed that photos could be not “mere illustrations but an essential, integral part” of the novel.

Interestingly, he doesn’t rest his case on realism, the idea that the story would seem more plausible if it contained documentary images. But surely the appearance of a photographic record gives a forensic quality to the shots of clues and corpses. At the period, tabloids and even “family” magazines like Life and Look were incorporating gory crime-scene images.

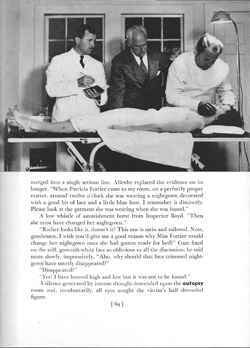

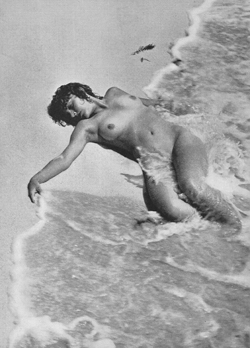

In The Castle Island Case, as befits fiction, these are more artfully composed. The shots of Allenby at an autopsy and of a topless woman washed onto the beach, we’re told, “were a very definite part of the story and were not included merely for effect.”

Still, they are a bit startling in their prim sensationalism. (One reviewer: “A thriller more highly seasoned than most.”) The book’s up-and-coming publisher, Reynald & Hitchcock, had developed a reputation for daring: it published Hitler’s Mein Kampf in a complete translation the same year as Mason’s novel. Later the firm would issue policy books from a liberal standpoint and, in 1944, the controversial Lillian Smith novel Strange Fruit.

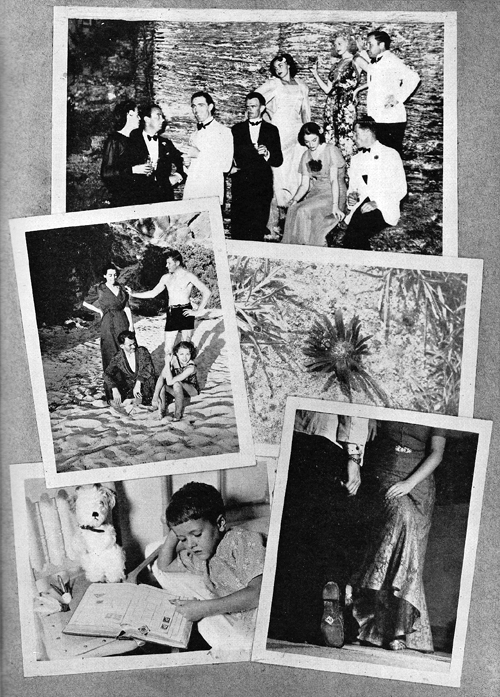

For the shoot Reynald & Hitchcock flew the cast to Bermuda, where Mason lived. The story incorporated the exotic scenery and local life, notably a Gombey performance. Mason and Gipson accumulated about 600 stills in ten days, and they checked their results immediately, processing films far into the night. The finished book includes 180 or so shots, printed alongside text on glossy paper and bound in a large 7½ x 10-inch trim size that make them easy to study. An essential hook, trumpeted on the dust jacket, is that you can examine the pictures to find evidence that the text doesn’t mention. This was to be the first in a series of “Candid Clue Mysteries”–crime traces captured by the candid camera.

Picture this

Major Roger Allenby has flown to Bermuda to help an old friend whose daughter Judy has gone missing. She was serving as secretary to millionaire Barnard Grafton. Allenby arrives under the pretext of joining Grafton’s shady business deal with the president of Ecuador. Grafton is hosting other potential investors and several female guests. The set-up is a classic mystery situation: an isolated setting and a small group of wealthy people, some of whom will die or disappear, leaving the others as suspects. Soon Judy’s sister Patricia, who has replaced her on Grafton’s staff, is murdered.

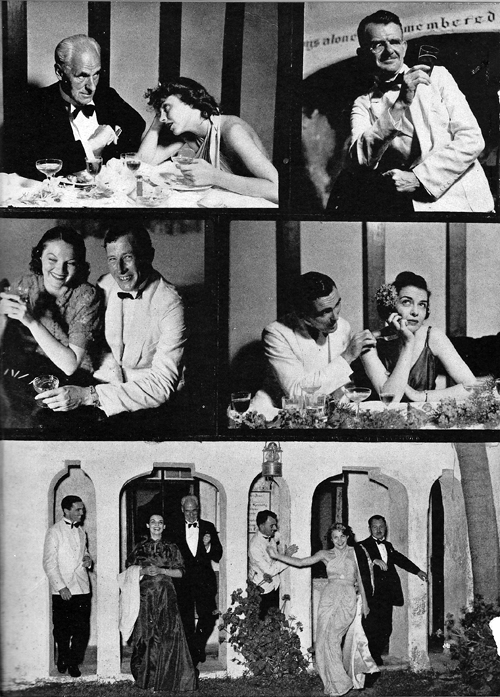

The photos are of three types. One operates as classic illustrations, showing all the characters from an impersonal perspective. So Allenby can be seen among others, as in the rather Straub/Huilletian autopsy image above. A second type of images is more “omniscient” and free-ranging, filling us in on background information.

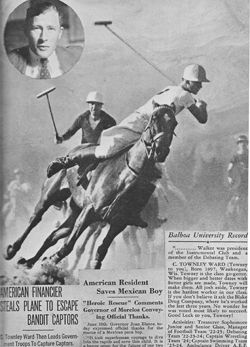

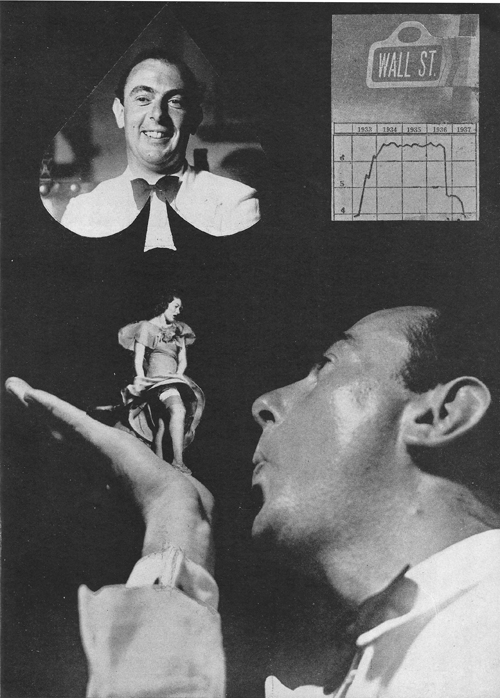

Mason declared that the photos could save time on exposition. Instead of describing the characters and settings, he could just show them. But he didn’t mention that, apart from Allenby, most major characters are introduced in abstract photomontages, not candid snapshots. The first one we see is devoted to wastrel C. Townley Ward. He’s presented in a collage of pictures and news clippings.

The page devoted to Ward could have been replaced with paragraphs of backstory. But the layout coaxes the reader into a process of scrutiny that’s probably more intense than scanning prose. Are there clues in the images or the clippings? This crammed page, coming early in the book, encourages the reader to look carefully at the pictures that follow. This attention wouldn’t necessarily be aroused by traditional drawn or painted illustrations.

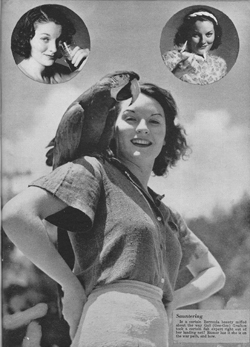

Sometimes, as in the page devoted to jaunty Kathleen Manship, the layout recalls comic-book splash pages.

A second sort of photos accords with Allenby’s restricted viewpoint. He has brought his camera along, so some images, like the nude shot on the beach, are represented as his recording of a crime scene.

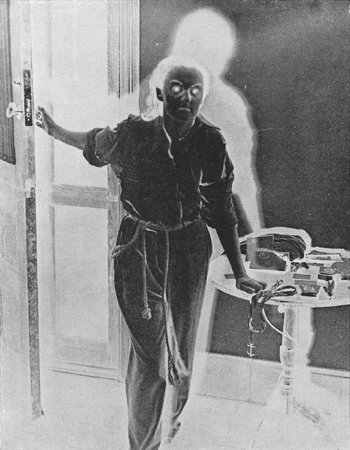

Naturally Allenby films letters and other obvious clues, and he sets traps to gain evidence. He rigs up an automatic camera device to capture an intruder, but to sustain suspense Mason shows us the negative first, then postpones revealing the person exposed (as above).

Sometimes, though, it’s Allenby’s casual snapshots that accidentally capture items whose significance is apparent later. In all, Mason tries to play fair with the reader. If you page back after the solution is revealed, you can find that indeed the clue was there (however tiny). In good mystery-mongering fashion, however, some pages are red herrings. They contain no clues, but you’re likely to study them anyhow.

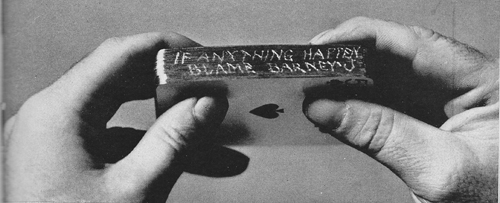

Photography also helps us grasp clues that are more vivid than a prose description could provide. My favorite is the telltale pack of playing cards left behind by Patricia after her death. Trying them out in different sequences, Allenby notices that they contain tiny nicks on their edges. Odd phrases in Judy’s purported suicide note suggest a code the sisters shared, so after cracking that and arranging the cards accordingly, Allenby finds that the nicks yield a message.

I think that the picture makes the discovery livelier than an account in the text would be.

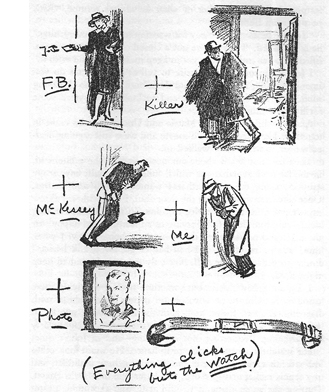

As in many detective stories, the clues are summed up before the detective reveals the solution. Here, Mason gathers up the most relevant photos Allenby has taken, challenging the reader to draw the right conclusions.

Another plot convention: the final assembly of the suspects for a public revelation of guilt. In this book, it’s done through Allenby’s setting a trap. He will take an infrared picture that will, during a crucial moment of darkness, expose the killer. The exercise neatly brings together the objective, omniscient type of photo and Allenby’s eyewitness shots. First we see the entire scene, including Allenby. Then his camera’s record is presented in radically washed-out tones, suggesting a different film stock. (The second frame below is a detail from the climactic two-page spread, to avoid a spoiler.)

Movies on the page

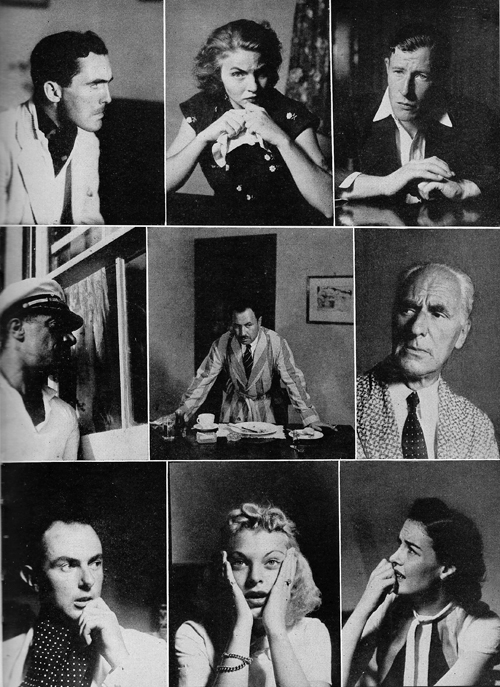

The gimmickry of The Castle Island Case is enlivened by some features that go beyond puzzle and fair play. The book breaks its own rules, sometimes in ways that recall films. For example, we get a cluster of reaction shots of the characters responding to news of Patricia’s death.

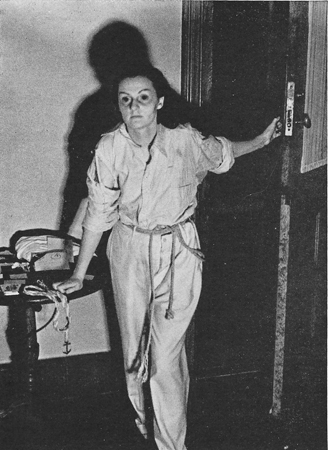

The pictorial narration running alongside the text sometimes breaks from our restriction to Allenby’s viewpoint for the sake of a cinematic effect. As he broods on the danger Patricia is in, the book “cuts away” to her in her bedroom. Four images show her sorting the playing cards, slipping the suicide note into a picture frame displaying her sister’s photo, tucking the pack of cards under her pillow, and–ultimate movie touch–sleeping while a clutching shadow hovers over her.

Still later, the book will present a pictorial flashback, complete with angle changes, to show what led to Judy’s disappearance. There’s also a photomontage illustrating Terry James’ freewheeling lifestyle that calls to mind the turbulent montage sequences of Slavko Vorkapich.

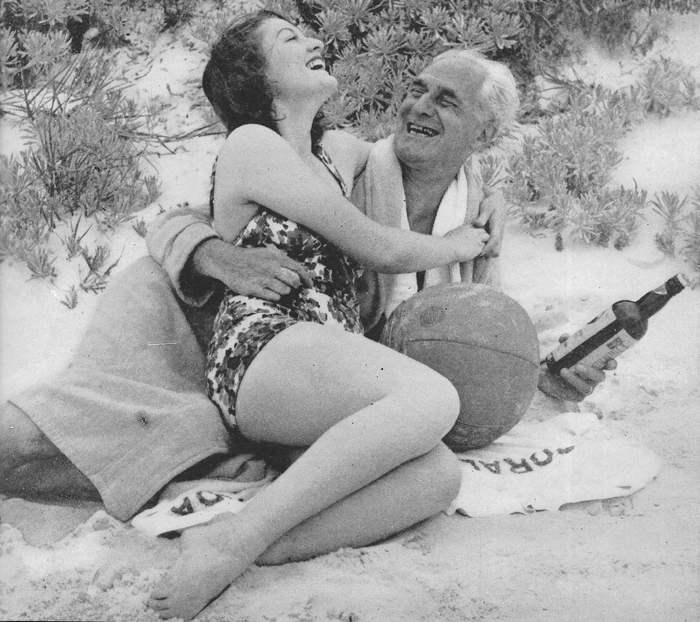

The book’s debt to cinema is perhaps most obvious in its last image, a clinch that traditionally closes a Hollywood movie. (See below.) Far stranger is the sequence devoted to the drinks-and-swims party.

One page presents the guests hanging out, with the bottom one suggesting a party snapshot not taken by Allenby, although he’s in it.

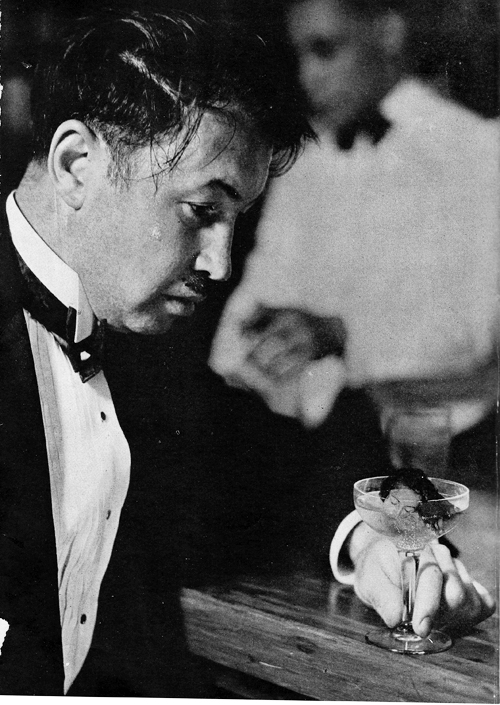

Facing this page is a curious portrait, evidently not taken by Allenby, showing a morose Grafton staring into his drink.

What’s he looking at? Inside the champagne glass is the head of an apparently drowning woman.

Is this a tipoff to the reader that Grafton killed Patricia? At the end we’ll realize what it means, but here it seems to offer a peculiar access to his mind, certainly beyond Allenby’s range of knowledge. In a film, the image might be an abrupt, enigmatic flashback to be explained later. Frozen on the page, and looking so different from the other photos we’ve seen, this hallucination turns into kitsch surrealism.

Nothing ever really goes away. Perhaps the murder dossiers transmogrified during the 1940s into the board game Clue (aka Cluedo). The Wheatley ones were reprinted in the 1980s and apparently caught on for a new generation. The Choose Your Own Adventure children’s books included mysteries that allowed some interactivity, anticipating the branching options of our investigation-driven videogames. And today’s jigsaw puzzle called Alfred Hitchcock is explained:

Alfred Hitchcock isn’t just another jigsaw puzzle – it’s a mystery waiting to be solved. First, read about a psychotic fan who’s obsessed with Hitchcock’s classic films. Next, assemble the puzzle and uncover hidden clues to solve the mystery.

Mason’s “Candid Clue Mystery No. 1” had no successors, but writers didn’t give up on trying to integrate images into mystery plots. Rex Stout tried it, with awkward results, in two Nero Wolfe stories. (One, naturally enough, appeared in Look magazine.) In Murder Draws a Line (1940), Willetta Ann Barber and R. F. Schabelitz divide the labor between a Nick-and-Nora couple. The wife writes the text and the husband, a professional artist, illustrates it with sketches and diagrams of their efforts to solve the crime.

Mason’s “Candid Clue Mystery No. 1” had no successors, but writers didn’t give up on trying to integrate images into mystery plots. Rex Stout tried it, with awkward results, in two Nero Wolfe stories. (One, naturally enough, appeared in Look magazine.) In Murder Draws a Line (1940), Willetta Ann Barber and R. F. Schabelitz divide the labor between a Nick-and-Nora couple. The wife writes the text and the husband, a professional artist, illustrates it with sketches and diagrams of their efforts to solve the crime.

The text-plus-photos books aren’t truly interactive. Nothing we do can adjust the text or create feedback. But they extend the possibilities of a narrative attitude encouraged by the mystery genre.

Classic detective novels and short stories rely on a type of close reading. We’re expected to scrutinize descriptions of locales and behavior for cleverly planted traces of what’s really going on. Agatha Christie has a genius for mentioning items that we read over, thanks to misdirection and the blandness of her prose, but even hardboiled novels bury verbal clues so as to play fair. A slip of the tongue that we probably miss leads Sam Spade to Bridgid O’Shaughnessy’s guilt.

Knowing that authors aim to mislead us through language, we read with a greater degree of suspicion than we bring to other genres. By extending this attitude to images as well as words, gimmicks like The Castle Island Case encourage us to consider how the pictures may tell the story, or sabotage our understanding of it. That’s what movies have done as well. We shouldn’t be surprised that these oddball efforts call on familiar storytelling schemas of classical cinema.

Chapter 17 of Martin Edwards’ splendid The Life of Crime: Unravelling the History of Fiction’s Favorite Genre, reviews many more of these Golden Age games. It’s due out from Collins in May of next year, but in the meantime visit Martin’s bountiful website and proceed to sample any of his vast output of novels, anthologies, and histories of detective fiction.

For background on Cain’s Jawbone, go to this account in The Guardian. It was reissued in 2019, as both a book and a set of cards (now very scarce). The publisher, appropriately called Unbound, offered a prize of £1000 for the first solution. The prize was won by a comedy writer who cracked the puzzle while housebound during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dorothy Sayers’ remark on her Five Red Herrings ploy comes from Janet Hitchman, Such a Strange Lady: A Biography of Dorothy L. Sayers (New York: Avon, 1976), 88-89. The Sayers story using a (very tough) crossword puzzle is “The Fascinating Problem of Uncle Meleager’s Will” (1925).

My quotations from Van Wyck Mason come from “The Camera as a Literary Element,” The Writer 51, 11 (November 1938), 325-326. The review I quoted, unsigned, appeared in “The Criminal Record,” The Saturday Review (9 October 1957), 28.

The Rex Stout Nero Wolfe stories inserting photographs are Where There’s a Will (1940) and “Easter Parade” (1957), reprinted in And Four to Go (1958). I don’t talk about them here.

Thanks to Peter McDonald for introducing me to Virginia, The Shivah, Blackwell Unbound, and other mystery-driven videogames.

P.S. 25 June 2021: Alert reader and old friend Jonathan Kuntz reminded me of other interactive mystery platforms, including the Secret Cinema screenings. He also mentions non-mystery boardgames that let you replay films, as in The Thing and The Lord of the Rings.

P.P.S. 28 June: Alert reader and mystery maestro Mike Grost traces a chain of association to the champagne-glass image. Van Wyck Mason published a story called “The Enemy’s Goal” in Argosy (18 May, 1935). That story was adapted by Joseph H. Lewis for a film, The Spy Ring, released in 1938, and there a character summons up a mental image in a champagne glass. I haven’t seen the film, but Mike suggests that such subjective shots are fairly rare in Lewis films. He thanks Francis M. Nevins for finding the link, and I thank both.

The Castle Island Case (detail).

A tantalizingly anonymous Josef von Sternberg film

Children of Divorce (1927)

Kristin here:

In 2008, David and I attended Il Cinema Ritrovato for the sixth time. The Hollywood director being featured that year was Josef von Sternberg. We saw some of the gorgeous prints on show, most notably (for me), a chance to re-watch the underrated Thunderbolt (1929), his first sound feature. To us the big auteur of the year, however, was Lev Kuleshov. Astonishingly, we only blogged from the festival once that year. It was a busy summer.

We and a great many other festival-goers lined up to see one of the rarer items on the program: Children of Divorce, credited to Frank Lloyd but with reportedly about half the footage re-shot anonymously by von Sternberg. We and a considerable number of those festival-goers did not get into the auditorium. For some reason this rare, legendary film was shown in the smallest venue, the Mastroianni, which was packed, with the two side aisles full of standees. (See the bottom image of our blog from the festival, as we caught a glimpse of those lucky enough to get in before retreating to find something else to watch or perhaps to wander around the always enticing Film Book Fair.)

Eight years later, in 2016, Flicker Alley released a Blu-ray/DVD combo of the Library of Congress’ 4K restoration of Children of Divorce. That two-disc set is out of print, but last month a MOD (manufacture-on-demand) version was made available. It is a single disc, Blu-ray only, and its main supplement is a pretty good one-hour documentary on Clara Bow produced in 1999 for TCM. (The original booklet is not included.) Somehow we missed the original release, but now I have a chance to catch up with this elusive film.

Naturally I wanted to find out if any information on which scenes of the film von Sternberg re-shot were available, I looked at various internet sources, including books in our library the reviews of the original 2016 Flicker Alley release and books. I found nothing on the subject, not even from film buffs speculating on the basis of style which scenes were his. I suppose one reason why so little discussion of von Sternberg’s contribution is that for many viewers and purchasers of the Flicker Alley discs, this a Clara Bow and Gary Cooper film. Those online reviews from 2016 focus on them rather than on the two very different directors of Children of Divorce. The third star, Esther Ralston is excellent as Jean, and in 1929 she would go on to play the title character in The Case of Lena Smith, Sternberg’s last silent film, which survives only in a fragment. Still, she doesn’t have the lingering reputation and devoted following that her co-stars still enjoy.

Spoilers ahead, including a revelation of the ending.

Von Sternberg’s account

In trying to discover von Sternberg’s contribution, we seem to be entirely dependent on von Sternberg’s sketchy recollections of his work on the film in his memoir, Fun in a Chinese Laundry (1965). Needless to say, one cannot take his account as the unvarnished truth, but it may contain some elements of that commodity.

According to von Sternberg, B. P. Schulberg, head of Paramount, asked him to watch a film that the studio considered unreleasable. Could von Sternberg could improve it by adding the sort of clever intertitles that he was then known for?

I looked at the film as he requested. Its title was Children of Divorce, and it had been made by a prominent director, Frank Lloyd, normally an effective director of commercial films. This one was a sad affair, containing theatricals by Gary Cooper and Clara Bow, the “It” girl of her day. I reported back to the executive who had backed this venture with a million dollars, and told him that no skill of mine could restore life to the film by injecting text into the mouths of the players. I suggested that half the film be remade.

That Lloyd should fall down so badly seems odd, given that he had been cranking out films at a rapid pace since 1915. These included films that would be considered star vehicles and adaptations of popular literature, such as the first version of The Sea Hawk in 1924. He would soon go on to win two early best-director Oscars, one for the Greta Garbo vehicle The Divine Woman (1928) and one for Cavalcade (1933), as well as being nominated for what is probably his best-known film, Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)–which won Best Picture despite not winning any other of its seven other nominated categories. Cavalcade often shows up on lists of the worst films ever to won the highest prize, but nevertheless, it seems odd that a director so respected within the industry that he won an Oscar for a film made the year following Children of Divorce‘s release should fall down so badly in creating the latter. We shall probably never know what cause this strange failure.

I must admit to never having seen a Frank Lloyd film, but von Sternberg’s assessment of him as an “effective director” seems lukewarm. It suggests that although Lloyd was a good, solid Hollywood practitioner, he had created an unwonted lemon.

In assessing the verity of von Sternberg’s account, we should pause over von Sternberg’s claim that Children of Divorce had had a million-dollar budget. That was well above the average cost of a film in those days. (Von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives, with its giant Monte-Carlo set, had gone over budget to become the first million-dollar film in 1922, and Universal head Carl Laemmle made the best of the situation by blazoning the extravagant budget in publicity for the film.) The original costs estimate sheet on Flicker Alley’s site, along with other documents from the film’s production, puts the total budget at $334,000–pre-re-shoots–a far more plausible sum. Possibly, writing in the wake of the scandal over the cost overruns leading to an estimated $44 million budge for Cleopatra (1963), he had to boost the paltry-sounding budget of a late-1920s feature at least to seven figures to show that he was doing an important favor for Schulberg.

In response to von Sternberg’s suggestion that half the film be remade, Schulberg (according to von Sternberg) said that he could not allot another five weeks to making changes in a project that still might flop. Von Sternberg writes, “I carelessly replied that I could remake half the film in three days and turn over a successful version to him.”

Schulberg asked, “What can I do about the sets? They’ve been torn down and the stages are full.”

Again according to von Sternberg, “I told him to have a tent erected for use as a stage and to dig out the sets from storage, and not to bother about anything else.” Schulberg agreed.

Von Sternberg’s entire account of the process of re-shooting the scenes runs as follows:

The tent went up and the transfusion began. A rainstorm came and lasted three days and three nights. We waded through the new scenes, now and then dodging a heavy burst of water that penetrated the canvas overhead. The crew that helped me and the poor actors that I mercilessly put through their new paces had to take a prolonged rest cure when I had finished with them. To match the scenes I wished to retain I had to use the style of the replaced director. The assignment was completed on time and, after removing the old scenes and replacing them with the new material, I showed the film to the flabbergasted executives.

This tells us discouragingly little. The weather and the cast’s exhaustion make for a dramatic tale but tell us nothing about the film itself. The only statement of interest is “To match the scenes I wished to retain I had to use the style of the replaced director.” Von Sternberg certainly knew the well-established norms of Hollywood filmmaking and if he deliberately set to blend his work into an existing film, his style could be difficult to detect. After all, we don’t know exactly what was wrong with the original version. Bad performances? Von Sternberg’s reference to “theatricals by Gary Cooper and Clara Bow” suggests that this may have been the case. Bad storytelling? Von Sternberg doesn’t mention whether he re-wrote any of the scenes he revised.

The new version premiered on April 2, 1927. Von Sternberg was not paid for his labors (he says), but he did prove himself as a director. Schulberg allowed him to direct an entire feature himself. Later that year, on August 20, his first silent masterpiece, Underworld, came out. This item in Variety of March, 1927, seems to confirm the basic claim of von Sternberg’s account. Several trade papers mentioned that Sternberg had re-shot some scenes, but none specifies which ones.

Briefly, Children of Divorce concerns two girls whose recently divorced parents have dumped them in a convenient French convent to be cared for. The parents return to the free life of single people, visiting their daughters infrequently. Kitty, a frightened, lonely girl, befriends the kindly Jean. Kitty introduces Jean to Teddy, an old neighbor of Kitty’s. Teddy and Jean hit it off and promise to marry as adults.

Kitty grows up and becomes Clara Bow. She is poor and must give up her love for the noble but impoverished Prince Ludovico (Einar Hansen) to pursue Teddy, now grown up to be Gary Cooper and very rich. His meeting with the grown-up Jean (Esther Ralston), herself now described as the richest woman in the USA, rekindles their love. Despite knowing this, Kitty uses the occasion of a drunken party to trick Teddy into marrying her, and they have a daughter.

Teddy wants to divorce Kitty and marry Jean, but insists that the daughter must not be as they were, a child of divorce. Kitty thinks this would free her to marry Ludo, but he informs her that his religion would not permit him to marry a divorced woman. She determines to hold onto Teddy. Jean decides to marry Ludo, thus quashing Teddy’s hopes of marrying her. Pure misery abounds–all the result, one way or another, of divorce.

What did von Sternberg do?

Naturally one would wish to know which scenes are Lloyd’s and which Sternberg’s. In her brief program notes for the film in the Bologna catalogue, Janet Bergstrom confidently comments, “You can’t miss the shadow language of his scenes.” Perhaps not, but there are actually very few Sternbergian shadowy shots in the film, and those are often brief touches. Here are the main examples. The second scene of the film shows the young Kitty (later to grow into Clara Bow) during her first night in the French convent where her newly divorced mother has dumped her (bottom). In another such atmospheric shot, Teddy reads Jean’s letter refusing to marry him if he divorces Kitty (top).

Other such shots occur occasionally. When Teddy and Kitty’s daughter totters winsomely down the stairs during a party, the elaborate railing casts a shadow over her. Jean’s first sight of her fixes her determination that for the sake of the child she will not agree to marry Teddy if he divorces Kitty.

These are the only shots that one could argue contained strongly Sternbergian shadows. The opening scene in the convent as Kitty’s mother leaves her has a shadow of an offscreen window on the wall at the center of the shot, but surely one could not be certain that an image directed by Lloyd could not have such a modest shadow simply to create the atmosphere of the setting.

Indeed, it seems like a typical shot from an A picture of the mid-1920s.

I do not think that one can determine which shots and scenes were redone by von Sternberg just by the lighting. “To match the scenes I wished to retain,” von Sternberg must have used the three-point lighting system that had been established as the norm during the second half of the 1910s. He did a very good job, and there are many scenes that look like they could have been shot by Lloyd or Sternberg, adhering to that same norm and of course using the same sets and costumes. Which of the two directors made this image, with its exemplary use of the three-point lighting system devised by Hollywood practitioners in the second half of the 1910s?

Von Sternberg’s reference to Lloyd as an “effective” director may sound like diplomatic, lukewarm praise, but he might have meant that any good Hollywood director with an experienced cinematographer could have produced such an image, with its perfect blend of key, fill, and back lighting.

Similarly, we might be tempted to identify this glamor shot of Ralston as directed by von Sternberg, but it seems a fairly conventional approach to filming a beautiful star in the late 1920s.

And here’s an impressive depth staging in the scene where Luco tells Kitty that he could never marry a divorced woman for religious reasons.

It is tempting to think that the stark juxtaposition of a sharply in-focus foreground cut off from the soft-focus background by the edge-lit fringes on the curtains is a von Sternbergian touch, but we cannot be certain that Lloyd and a good cinematographer could not create the same effect.

A possible, probable von Sternberg scene

The big climactic scene sure looks like a very skillful director made it. One is tempted to say that that director was von Sternberg.

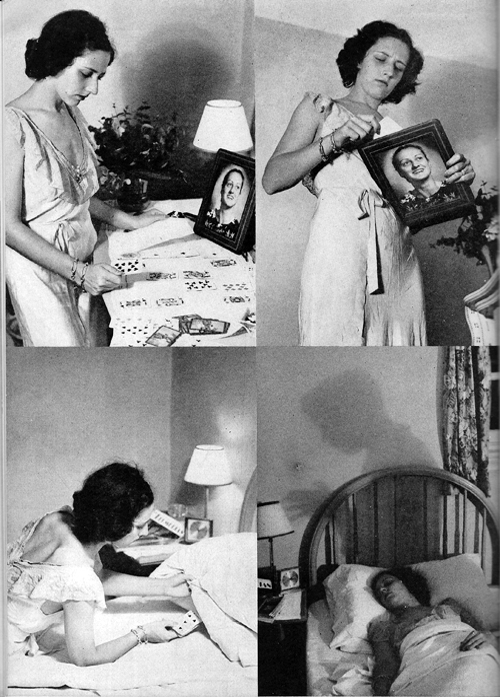

The action brings to a head Kitty’s machinations. Having been rejected by Luco, she realizes that her refusal to let Teddy and Jean be together is making them miserable and is not the best thing for her daughter, either. She writes a suicide note addressed to Jean, hugs her daughter for the last time, and heads into her bedroom clutching a bottle of poison.

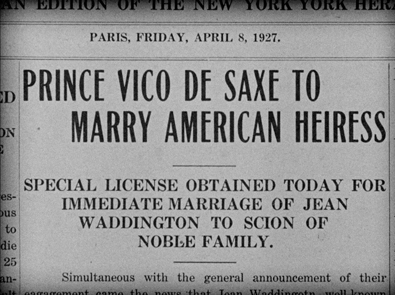

Here is a breakdown of the scene. It begins with Kitty reading a newspaper. We see her point-of-view, revealing that Luco is going to marry Jean. Luco has already rejected her, but this scene is the moment when she learns that he is to marry her friend. The newspaper shot is followed by a closer view of Kitty.

She looks up and to her right, her face grim. It is notable that Bow has been de-glamorized for this scene, with her eyebrows minimized and her hair swept back from her face in a matronly style quite different from her usual bouncy curls. The camera pulls in toward her until it is in extreme close-up.

The pull-in reveals a tear that has slid down from her right eye. It is worth pointing out that this is Clara Bow, noted for her flapper image, always lively and carefree. Clearly she could play drama and even melodrama. Perhaps this is an instance of von Sternberg’s famous ability to direct female performances.

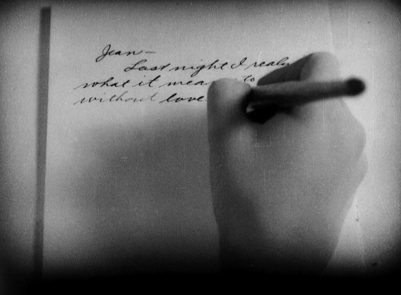

The intense close view is interrupted by a cut to Kitty dropping the newspaper. A long shot follows as she stands and moves to sit down at the desk. A cut-in to a medium shot shows her thinking and beginning to write.

This leads to her point-of-view on what she writes. We learn only that it is a letter to Jean and that Kitty has had a realization. A return to the medium-shot framing shows her reacting to a knock at the offscreen door and saying, “Come in” as she hides the letter under the desk-blotter. An eyeline-match cut shows her daughter entering. A pan follows as she crosses to the desk and Kitty kneels to embrace her.

A cut-in shows Kitty emotionally embracing the girl. During the course of this, the girl’s hat falls off. In a return to the medium-long shot, Kitty carries the girl to her nurse. Another shot shows her returning to fetch the fallen hat and hugging it while displaying despair.

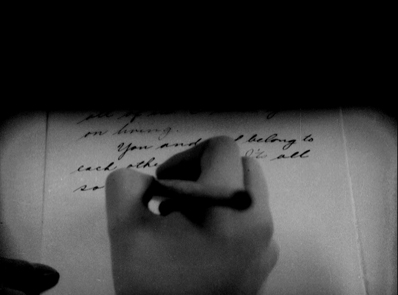

A more distant framing shows her putting the hat back on the child. The nurse’s cheery expression as she helps put the hat on contrasts greatly with Kitty’s unnoticed emotion. Once the others leave, Kitty returns to sit at the desk and pulls out the unfinished letter. Again we see her point-of-view as she completes the letter and we realize that it is an apology and suicide note, telling Jean to marry Teddy and raise the daughter that should have been hers. A return to the medium shot shows her putting the letter into an envelope.

A rather clumsy and unnecessary cut-in to a tighter shot of Kitty might suggest a blend of Lloyd and von Sternberg footage is occurring, but the lighting on the set, Kitty’s hair-do and costume are identical, so the footage is probably all from the same director. A return to the previous medium shot shows Kitty hesitating as she finishes addressing the envelope and presses a button to summon a servant. A cut back to a more distant shot shows her rising and starting rightward toward the door.

A cut to the doorway shows Kitty handing the envelope to a maid, who leaves. Kitty than moves away from the camera to reach for a small cabinet on a table. A cut-in with match-on-action shows her unlocking the cabinet and taking out an object barely recognizable as a small bottle.

A cut to the mirror above the cabinet shows Kitty looking at herself, with the image of her face going out of focus. A cut to a medium-long shot leads to the camera panning with Kitty as she moves to a door at the rear.

She opens the door and walks into the distance as the camera tracks slowly back.

That’s a pretty flashy scene, and it certainly seems more likely than not that von Sternberg directed it.

Once again Flicker Alley deserves credit for bringing us another important film from the silent era.

Thanks to our friends at Flicker Alley for facilitating this entry.