FILM ART: The eleventh edition arrives!

Tuesday | February 2, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

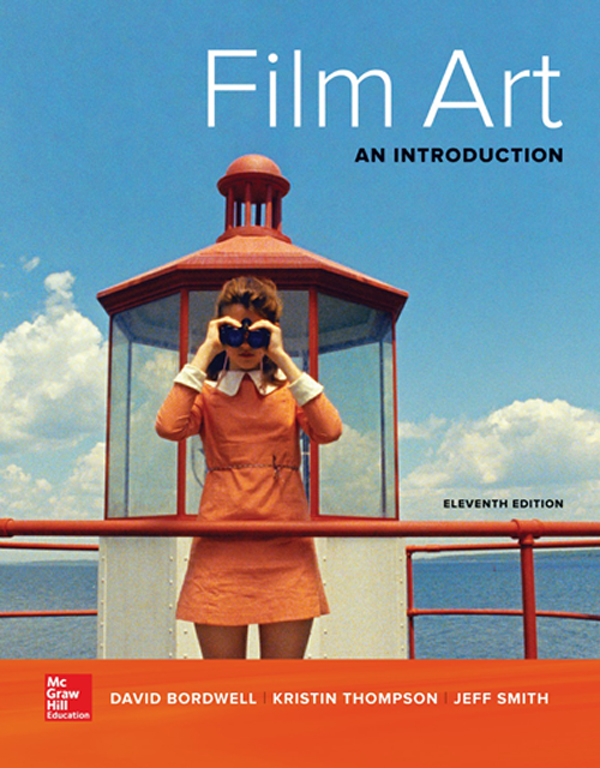

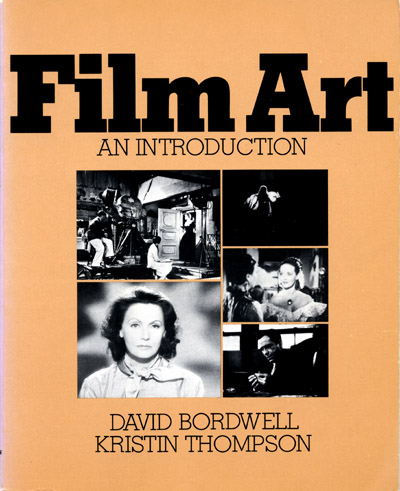

Forty years ago, Kristin and I signed a contract with Addison-Wesley publishers to write Film Art: An Introduction. The first edition, a squarish item with a butterscotch-brown cover, was published in 1979. Like most textbook authors, we had to assign all rights to the publisher. Addison-Wesley sold our book to Knopf, which produced a second edition in 1985. Then the book was acquired by McGraw-Hill. McGraw-Hill published the subsequent nine editions, from 1990 onward.

Last week, Kristin and I and our new collaborator Jeff Smith received our copies of the eleventh edition. It looks very good and we think it’s our best effort yet. By chance, we learned at the same time that Film Art, in all its editions, currently ranks as 153 in books assigned in American college courses (based on a sample of nearly a million syllabi). No other film textbook appears in the top 400 titles. Back in the 1970s we never imagined such success.

FA 11e contains many new features, which I’ll talk about shortly. But I’d also like to say some things about the book’s perspective on cinema. I’ve discussed the conceptual side of our approach in an entry devoted to the previous edition.

But since concepts don’t arise from nothing, I thought I’d wax a little personal and talk about how Film Art has reflected my developing ideas about movies. Readers wanting the meat-and-potato information about the new edition can skip down to the section, “Humblebragging, minus the humble part.”

A bookish movie wonk

I came to movies through books. I must have been fourteen or fifteen when I read Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957). It was the first grown-up book that I thought I completely understood. Soon after I read Rudolf Arnheim’s Film As Art (1957), which I knew I did not completely understand. But those two books became my guides to what films to see and what ideas to think about.

I came to movies through books. I must have been fourteen or fifteen when I read Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957). It was the first grown-up book that I thought I completely understood. Soon after I read Rudolf Arnheim’s Film As Art (1957), which I knew I did not completely understand. But those two books became my guides to what films to see and what ideas to think about.

Living on a farm, I was somewhat isolated, but I did see Hollywood classics on television, and I could occasionally catch current releases at theatres in nearby towns, notably Rochester, NY. With the aid of Andrew Sarris’s “American Directors” issue of Film Culture and some issues of Movie (UK), my high-school years became devoted, in part, to film.

During the 1960s, interest in film exploded. Europe’s “young cinemas” like the French New Wave came to prominence. Hollywood films became edgier. High-tone magazines began to pay attention. This was the era in which James Agee, Parker Tyler, and Manny Farber gained somewhat delayed fame as critics. (I talk about this development in my Rhapsodes book.) Cahiers du cinema became known outside France, and American critics like Sarris and Pauline Kael became artworld celebrities.

In the same era there came a burst of film-appreciation books. They weren’t textbooks per se, but they were often used in the film courses that were springing up across the country. Among those books were Ernest Lindgren’s The Art of the Film (rev. ed., 1963), Ivor Montagu’s Film World (1964), and Ralph Stephenson and J. R. Debrix’s The Cinema as Art (1965). I was drawn to the idea of a general account of the possibilities of film as an art form, so these books, followed by V. F. Perkins’ contrarian Film as Film (1972), appealed to me. I later realized that they belonged to a genre that stretched back to the 1920s and included extraordinary contributions like Renato May’s Linguaggio del Film (1947). Still further back, they, like all texts, owe a debt to Aristotle’s Poetics and Renaissance treatises on the visual arts.

Throughout my college years, I thought that the core activity of film culture was criticism: the effort to know a movie as intimately as possible. That’s still a widely-held view. In graduate school at the University of Iowa, my horizons expanded, as I was exposed to film history, though not through much primary research, and film theory, which was just starting to be a major wing of academic cinema studies. My dissertation was on French Impressionist silent cinema, what’s come to be called the “commercial avant-garde.” I wrote it because I wanted, ultimately, to understand the context around Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, but for the project I concentrated on directors like Gance, L’Herbier, Epstein, Dulac, and Delluc. The thesis had three parts: one on the historical context, one on Impressionist theory, and one analyzing the films. This mixed approach has become a common one for me. I still think that a movie will sit at the center of my interest, but I’m attracted to questions that cut across criticism/history/theory boundaries.

Throughout my college years, I thought that the core activity of film culture was criticism: the effort to know a movie as intimately as possible. That’s still a widely-held view. In graduate school at the University of Iowa, my horizons expanded, as I was exposed to film history, though not through much primary research, and film theory, which was just starting to be a major wing of academic cinema studies. My dissertation was on French Impressionist silent cinema, what’s come to be called the “commercial avant-garde.” I wrote it because I wanted, ultimately, to understand the context around Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, but for the project I concentrated on directors like Gance, L’Herbier, Epstein, Dulac, and Delluc. The thesis had three parts: one on the historical context, one on Impressionist theory, and one analyzing the films. This mixed approach has become a common one for me. I still think that a movie will sit at the center of my interest, but I’m attracted to questions that cut across criticism/history/theory boundaries.

Before the 1970s, most college film courses were organized historically, running from Lumière/Méliès/Porter to Neorealism. (Arthur Knight again.) But there was emerging a different sort of course, one that surveyed “the language of film” conceptually. Just as an introduction to music would lay out basic categories like melody, harmony, rhythm, and form, so film courses—in the manner of the aesthetics surveys I mentioned—would try to isolate the basic elements of cinema. This new orientation was probably also inflected by semiotics, then becoming a hot topic in grad-school circles.

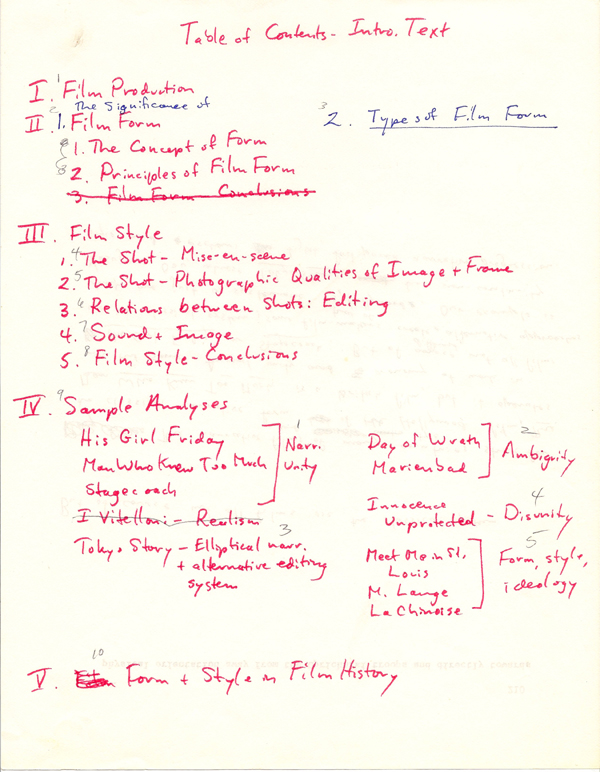

When I came to UW—Madison in 1973, ABD and eager to work, I was given the basic survey course, Introduction to Film. It enrolled about 400 students a semester and was held in a gigantic classroom; from the stage I could barely see the students in the back. (There were a lot of them back there, for reasons we now understand.) I had four stalwart teaching assistants: James Benning, Douglas Gomery, Brian Rose, and Frank Scheide, all of whom have gone on to fame. Learning as much from them as they did from me, I organized the course as a survey of film form and style. That overall structure was the first rough cast of Film Art.

By this time there were several books designed as textbooks for such an appreciation course. After reading a few I decided not to use any. I relied on Perkins’ Film as Film, Noël Burch’s Theory of Film Practice, Jim Naremore’s excellent monograph on Psycho, and photocopies of essays by Bazin and others. After teaching the course for three years, I decided, at the suggestion of the Addison-Wesley editor Pokey Gardner, to propose it as a textbook. Kristin had by then taught the Intro course with me, had published some articles, and was working on stylistic analysis for her dissertation on Ivan the Terrible. She became my coauthor, beginning what some have called America’s longest study date.

From treatise to textbook—and back again?

Although we wrote it for the textbook market, I didn’t think of it as a textbook. With the hubris of a twentysomething, I thought of it as my treatise on film aesthetics. I wanted it to be as comprehensive as I could make it.

As Perkins pointed out, most books on film aesthetics were tied to the idea of the silent film as the pinnacle of film art. Editing was conceived as the supreme film technique, and Griffith and Eisenstein were presented as paragons. Admiring both of them and silent film as a whole, Kristin and I wanted nonetheless to give decent weight to “the Bazinian alternative”: long takes, camera movements, staging, and cinematography in depth were no less significant artistic resources. Color, sound, widescreen, and other resources were often ignored by the older tradition, but they had to be given their due. (At this point Play Time became a touchstone for us. It still is.) Burch’s book was particularly important as a quasi-structuralist revision of Bazinian ideas; I found, and still find, this book inspiring.

Just as important, I thought, was a need to situate techniques of the medium in a holistic context. While I was pursuing DIY film studies down on the farm, I was also reading modern literature and the New Criticism that then dominated literary life. For me, The Context Of The Work was everything. The whole would always nourish whatever technical tactic or local effect we might pick out.

Many textbooks still insist that techniques have localized meanings: a high angle means that the subject is diminished and powerless. Yeah, except when it doesn’t, as we insisted about this shot from North by Northwest in the first edition and since. (“I think that this is a matter best disposed of from a great height.”)

Because I was interested in the whole film, I was attracted to philosophers of art who balanced a recognition of style with a recognition of overall form. Thomas H. Munro’s Form and Style in the Arts (1970) helped me with this, but the major influence was Monroe Beardsley’s Aesthetics (1958), with its distinction between texture and structure. That distinction meant realizing that films displayed large-scale formal principles, like sonata form in music. What were those principles?

Hence a chapter on narrative and non-narrative forms. We developed ideas of narrative out of formalist and structuralist theories. In the first edition, there was a lot more on narrative than on other sorts. In later editions, we tried to flesh out some genuine non-narrative options: abstract form (Ballet Mécanique and many experimental films); categorical form (e.g., Gap-Toothed Women, The Falls); rhetorical form (e.g., The River, Why We Fight); and associational form (e.g., A Movie, Koyaanisqatsi, and many “film lyrics”).

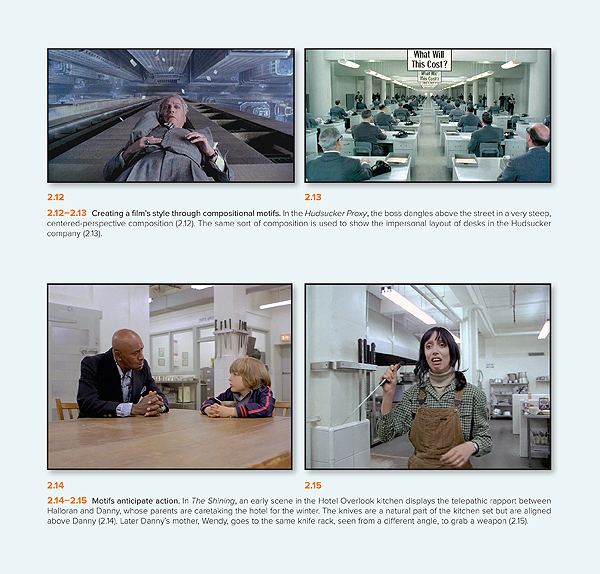

In teaching Introduction to Film, I noticed that many students hadn’t been exposed to basic aesthetic concepts like form, style, theme, subject matter, motifs, parallels, and the like. The old New Critic in me rose up. I thought these ideas and terms, being central to the aesthetics of any medium, needed to be in the book too. Hence a chapter “The Significance of Film Form.” (Above is a page illustrating visual motifs: perspective design, props set up to be used later.) Some have taken this chapter as a manifesto of a “formalist” perspective, but actually the ideas in the chapter are ingredient to any aesthetic position whatsoever. Every analyst will trace patterns of development in a film, or weight the opening strongly, or notice thematic parallels. These are basic tools for thinking and talking about any art.

But I wasn’t a New Critic 100%. I’ve always been interested in going beyond the artwork itself to look at the artistic traditions and institutions behind it. Because a film results from a concrete process of production, I thought it important to include a chapter on how a movie gets made. That topic was the first one in our introductory course; the reading was Truffaut’s “Journal of Fahrenheit 451.” Starting Film Art with a chapter on production served to introduce film techniques in a concrete context, and it showed how what appeared on the screen was the result of choices among alternatives. We thought, and still think, that this chapter might engage students who want to pursue filmmaking themselves. It’s been gratifying to learn that some production courses use the book.

The concern for practice led us to specify, for the first time in an introductory studies text, the 180-degree system of editing, the four basic dimensions of film editing, a layout of what you can do with sound in relation to space and time, and other practice-based concepts. We tried to systematize what filmmakers do, however intuitively. Sometimes we popularized terms that were already specialized (e.g., “diegesis” for the world of a story). Sometimes we had to invent terms for things that didn’t have names (e.g., the graphic match in editing). Sometimes we had to pick one usage of a term that was used in several ways (e.g., jump cut). Sometimes we had to make distinctions that weren’t explicit in the literature, such as the difference between story and plot, or deep-space staging and deep-focus cinematography.

Creating such labels may seem pedantic, but once we have a name for something we can notice it. Kristin and I believed that a study of film aesthetics has to be alive to all creative possibilities we can imagine. For example, in probably the toughest part of the book, we sought to account for all the possible creative choices involved in relating sound to narrative time. Maybe some options are rare, but they do exist as part of cinema, and they may yield powerful effects.

Aesthetics in history

Beetlejuice.

Other features of the book flowed from these central ideas. Because of the emphasis on holism, we added sample analyses as well—studies of single films that showed how the various techniques worked together with overall form. The urge to be comprehensive led us to devote more space to experimental, documentary, and animated film than was common in introductory textbooks. And, since this was a period in which academic film studies was making important discoveries, Kristin and I thought it important to discuss the concept of the “classical Hollywood cinema,” a powerful tradition of story and style that students would have often encountered. By the time Film Art 1e was published, we were planning what would become The Classical Hollywood Cinema, written with Janet Staiger.

So Film Art became a treatise. Was it a textbook? I wasn’t sure. I thought the publisher might turn it down. Even though it incorporated examples that were student-friendly, it had a daunting infrastructure. I thought faculty might find it too complex for most classes. Had it been rejected, I would probably have tried to publish it as a free-standing book like those 1960s treatises.

Surprisingly, all these features of the book were acceptable to the readers to whom Addison-Wesley sent the manuscript. Still, many had a big objection: There was no chapter on film history, and that would kill it for them.

I hadn’t included a historical unit in my introductory course because there wasn’t time. Besides, our department had a parallel course surveying film history. But Kristin and I were happy to accede to the readers’ request. We took as the chapter’s motto a line from art historian Heinrich Wölfflin: “Not everything is possible at all times.” (You see what I mean about complexity; what film textbook quotes Wölfflin?) The sentence simply means that the artist, in this case the filmmaker, inherits a limited set of possibilities of form and style, to which she can respond in a wide but not infinite variety of ways. We (mostly Kristin) used the concepts we’d developed in the book to trace a series of major traditions and schools, from early cinema through to the French New Wave. We’ve since enhanced that account, bringing it up to date with the New Hollywood and Hong Kong film, and accentuating the continuing importance of older trends–signalling, for instance, German Expressionism’s legacy in horror comedies like Beetlejuice, above.

We know that we owe a lot to luck of timing—to being at the start of academic film studies—and to the many, many teachers who have offered us suggestions for improving the book. One advantage of doing a textbook is that you can improve it incrementally, something not possible with a scholarly book that will probably see only one edition.

We’re gratified that the result has continued to be useful. We continue to meet teachers and students who tell us they’ve benefited from it. Filmmakers, too, from Pixar artists to experimentalists. The book has been given a couple of dozen translations. Other textbook writers have found our concepts, organization, terms, and examples persuasive. (When I see how closely some hew to our book, I don’t know whether to feel gratified or depressed.) We take this wide acceptance as a sign that we contributed something fresh and valid to our understanding of cinema. Maybe we did write a general aesthetic treatise after all—not the first, not the last, but one that remains illuminating and in some respects foundational.

Humblebragging, minus the humble part

From edition to edition our basic framework has been retained, but it’s flexible enough to be revised and fleshed out. Changes in film technology (digital cinema, prosthetic makeup, performance capture, 3-D) have prompted us to trace their effects on style. New developments demanded new concepts and names (“network narratives,” “intensified continuity”). Our research for other writing projects gave us deeper awareness of Asian film, early cinema, ensemble staging, and other subjects we’ve incorporated into our general perspective. Tough subjects to talk about, like acting, have challenged us to come up with some new ways of thinking about them. We’ve found old films that we want people to see; we think that we should also be educating taste and getting students acquainted with things beyond recent releases and cult classics. And of course new films have been made that demand attention—not only because students are aware of them but because the art of cinema continues to grow before our eyes.

The eleventh edition has changes small and big. Of course we’ve rewritten stretches to make them clearer or sharper. We’ve added new examples from about fifty films, from Nightcrawler and Brave to Zorns Lemma, Searching for Sugarman, The Act of Killing, and Beasts of the Southern Wild. The biggest changes involve a recast section on 3D, with discussion of House of Wax and The Life of Pi; a new section, “Film Style in the Digital Age,” with concentration on Gravity; a new section on genre devoted to the sports film (with Offside as a key example); and, as the cover tips you off, an extended analysis of Moonrise Kingdom, a favorite on the blog as well (here and here).

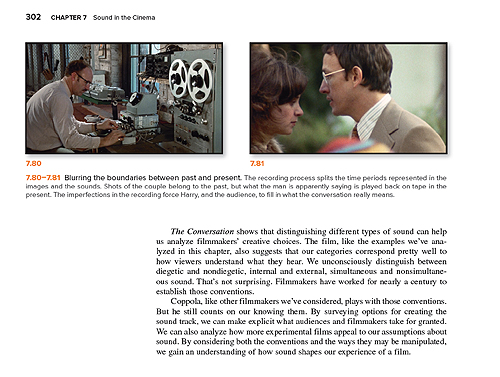

Jeff Smith (right, grinning) is responsible for many of these new attractions, and he has overhauled the entire sound chapter, with examples and analyses of Blow-Out, Norma Rae, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Nutty Professor (Jerry Lewis version), and The Conversation. In addition, Jeff has written a whole new chapter, number 13, on Film Adaptation. It is brilliant. It’s available as an add-on to the print edition for faculty who want to include it, and it comes along free on the electronic edition.

Jeff Smith (right, grinning) is responsible for many of these new attractions, and he has overhauled the entire sound chapter, with examples and analyses of Blow-Out, Norma Rae, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Nutty Professor (Jerry Lewis version), and The Conversation. In addition, Jeff has written a whole new chapter, number 13, on Film Adaptation. It is brilliant. It’s available as an add-on to the print edition for faculty who want to include it, and it comes along free on the electronic edition.

Under Kristin’s direction, with the kind cooperation of Criterion, we have added new video examples to the Connect online platform. Those include sequences from L’Avventura, Ivan the Terrible, I Vitelloni, and other major films, with voice-over commentary by one of us. In addition, our production guru Erik Gunneson has made a marvelous demo explaining sound mixing techniques.

In all, we’re very happy with the way the book has turned out. The pictures are vibrant, the design is crisp, and there are new marginal quotes and links to blog entries. As ever, the blog offers annual suggestions for integrating it with courses. We’ve also put up some video lectures on this site, listed on the left of this page, and of course people are free to use them in classes. A couple weeks ago we gathered some key blog entries around a central topic in Film Art, the nature of classical film narrative. Finally, as we’ve proceeded through many editions, we’ve had to cut several analyses of particular films. But those are still available as pdfs online; most recently,we posted our in-depth study of sound and narrative in The Prestige.

All these supplementary materials are attempts to illustrate and develop the ideas we’re proposing in Film Art–and to do so in a clear, concrete way. As we say in our introduction to the edition:

In surveying film art through such concepts as form, style, and genre, we aren’t trying to wrap movies in abstractions. We’re trying to show that there are principles that can shed light on a variety of films. We’d be happy if our ideas can help you understand the films that you enjoy. And we hope that you’ll seek out films that stimulate your mind, your feelings, and your intelligence in unpredictable ways. For us, this is what education is all about.

We remain grateful to the colleagues, instructors, students, and general readers who have supported what we’ve tried to do.

As part of McGraw-Hill Education’s multimedia publishing program, Film Art 11e is available in many formats, including a print edition and digital editions that meet the needs of entire film courses or independent readers.

*As always, instructors, students, and general readers can get a print copy of the new Film Art. It is available in bound or binder-ready form. Instructors who wish to order a custom print edition may include the bonus chapter on film adaptation.

*If you teach a course using Film Art, you can choose the digital option: Connect. Connect is a course-oranization tool that enables faculty to assign reading, submit writing, take assessments, and more. Connect gives students access to a subscription-based digital version of the book called SmartBook. SmartBook has the Criterion video tutorials embedded, plus the ability to assign all of the pre-built quizzes, practice activities, and other features. SmartBook includes the new chapter on film adaptation, along with additional material including our suggestions on writing a critical analysis of a film, and additional bibliographic and online resources.

Connect can integrate with your school’s learning management system, making it easy to assign and manage grades throughout the semester. Students will get access to SmartBook for 6 months; an instructor account does not expire, so you can reuse your Connect course semester-after-semester. Instructors may contact their local McGraw-Hill Higher Education representative for more information at http://shop.mheducation.com/store/paris/user/findltr.html. (Enter your state and school to find your rep’s name and email address.)

*If you want to read the book independently in digital form, you may choose standalone SmartBook. This version does not contain Connect’s course-administration supplements. The Criterion Collection video examples are embedded in the SmartBook for you to access any time throughout the subscription period. Students can opt for the SmartBook in place of a printed text, even if their instructor is not requiring Connect.

For more information: The buying options are explained here in general and the choices pertaining to Film Art are listed here.

We’re grateful to our editor Sarah Remington, as well as to Susan Messer, Sandy Wille, Dawn Groundwater, and Christina Grimm, for all their help on this edition!

Kristin’s 1977 chapter outline for the first edition of Film Art.