Archive for the 'Festivals: Ebertfest' Category

Unveiling Ebertfest 2014

Kristin here:

In the early days of Ebertfest, Roger personally introduced every film at this five-day event, which took place this year from April 23 to 27. He would be onstage for the discussions and question sessions after each screening, often joined by directors, actors, or friends in the industry.

In the summer of 2006, there began the long battle with cancer that Roger fought so determinedly. He withdrew gradually from full participation in the festival that he had founded in his hometown of Champaign-Urbana sixteen years ago. He struggled to immerse himself in the festival, even though repeated surgeries had robbed him of his voice. He introduced fewer films, doing so with his computer’s artificial voice, and when even that became too taxing, he sat in his lounge chair at the back of the Virginia Theater, enjoying the event and occasionally appearing onstage with a cheery thumbs-up. Finally, last year on April 4, less than three weeks before the fifteenth Ebertfest, he passed away. That year’s festival became a celebration of his life.

The celebration continued this year, though on a more upbeat note. Some films were chosen from a list that Roger had left to his wife Chaz and festival organizer Nate Kohn, and they selected others in the same indie spirit. The tradition of showing a silent film with musical accompaniment was maintained. As always, the festival passes sold out, and the crowd, including many long-time regulars, enthusiastically cheered both films and filmmakers.

The tributes

Roger did not live to see the documentary devoted to his life and based on his popular memoir of the same name, Life Itself. It premiered in January at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. He participated in its making, however, encouraging director Steve James (whose 1994 documentary Hoop Dreams Roger had championed) to film him during the final four months of his life. Some of this candid footage reveals the painful and exhausting treatments Roger underwent, but much of it stresses his resilience and the support of Chaz and the rest of his family.

Life Itself was the opening night film. James has done a wonderful job of capturing the spirit of the book and in assembling archival footage and photographs, interspersed with new interviews. The result is anything but maudlin, with a candid treatment of Roger’s early struggles with alcoholism and an amusing summary of Roger’s prickly but affectionate relationship with his TV partner Gene Siskel.

Life Itself was picked up for theatrical distribution by Magnolia Pictures and will receive a summer release, followed by a showing on CNN. (Scott Foundas reviewed the film favorably for Variety, as did Todd McCarthy for The Hollywood Reporter.)

Another tribute followed the next day, when a life-size bronze statue of Roger by sculptor Rick Harney was unveiled outside the Virginia Theater (above). Harney portrays Roger in his most famous pose, sitting in a movie-theater seat and giving a thumbs-up gesture. There is an empty seat on either side of him, so that people can sit beside the statue and have their photos taken. (See the image of Barry C. Allen in the section “Of Paramount importance,” below.)

Far from silent

Roger was a big fan of the Alloy Orchestra, consisting of (L to R above) Terry Donahue, Ken Winokur, and Roger Miller, who specialize in accompanying silent films. They have appeared several times at Ebertfest, playing original music for such films as Metropolis and Underworld. Rather than taking a traditional approach to silent-film music, using piano, organ, or small chamber ensemble, they compose modern scores, played on electronic keyboard combined with their well-known “rack of junk” percussion section, including a variety of found objects, supplemented with musical saw, banjo, accordion, clarinet, and other instruments. The result is surprisingly unified and provides a rousingly appropriate accompaniment to the silents shown at Ebertfest over the years.

I have had the privilege of introducing the film and leading the post-film Q&A on some of these occasions, including for this year’s feature, Victor Seastrom’s 1924 classic, He Who Gets Slapped. (Swedish director Victor Sjöström used the Americanized version during his career in Hollywood.) I put the film in context by pointing out three important historical aspects of the film. First, it was the first film made from script to screen by the newly formed MGM studio, formed in 1924 from the merger of Goldwyn Productions, Metro, and Louis B. Mayer Pictures. (Two earlier releases by MGM were Norma Shearer vehicles which originated at Mayer.) Second, it was probably the film that cemented Lon Chaney’s stardom, after his breakthrough role as Quasimodo in the 1922 Hunchback of Notre Dame. Starting in 1912, Chaney had been in well over 100 films before Hunchback, many of them shorts and nearly all of them supporting roles. Third, He Who Gets Slapped was Seastrom’s second American film after Name the Man in 1923, and a distinct improvement on that first effort.

Naturally MGM wanted a big, prestigious hit for its first production, and He Who Gets Slapped came through, being both a critical and popular success–and also boosted Norma Shearer to major stardom. Seastrom and Chaney both stayed on at MGM, though the former returned to European filmmaking after the coming of sound and Chaney died in 1930.

I was joined for the post-film discussion by Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune, and we talked with Donahue and Winokur while Miller sold the group’s CDs and DVDs in the festival shop. They revealed that this new score had been commissioned by the Telluride Film Festival and that it was a project that appealed to their taste for off-beat films. There were many questions from the audience, and we suspect that the Alloy Orchestra will continue to be a regular feature of the festival.

A cornerstone of indie cinema

Although Roger was occasionally criticized for supposedly lowering the tone of film reviewing by participating in a television series, he and partner Gene Siskel regularly tried to promote indie and foreign films that didn’t get wide attention. Roger did the same in his written reviews, and Ebertfest was originally known as the “Overlooked Film Festival.” Inevitably it was shortened by many attendees to “Ebertfest,” and eventually that name became official. It reflects the wider range of films that came to be included, with the silent-film screening and frequent showings of 70mm prints of films like My Fair Lady that were hardly overlooked.

Among Roger’s friends was Michael Barker, co-founder and co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, one of the most important of the small number of American companies still specializing in independent and foreign releases. A long-time Ebertfest regular, Barker usually brings a current or recent release to show, along with filmmakers or actors. This year he was doubly generous, bringing Capote (2005, above), to which Roger had given a four-star review, and the current release Wadjda (2012).

Roger never reviewed the latter, but it is certainly the sort of film that he loved: a glimpse into a little-known culture by a first-time filmmaker with a progressive viewpoint. Wadjda is remarkable as the first feature film made in Saudi Arabia, where there are no movie theaters. Moreover, it was made by a woman, Haifaa Al-Monsour, and tells the story of a little girl who defies tradition by aspiring to buy and ride a bicycle in a country where this, like women driving cars, was illegal. (Below, Wadjda learns to ride a bicycle on a rooftop, hidden from public view.)

Both the film and Al-Monsour thoroughly charmed the audience. Barker interviewed her afterward, and she revealed that, not surprisingly, the making of the film was touched by the same sort of repression that it portrays. Women are not allowed to work alongside men in Saudi Arabia, so Al-Monsour had to hide in a van while shooting on location. Given that there is no cinema infrastructure in the country, the film was a Saudi Arabian-German co-production, with Arabic and German names mingling in the credits. We also learned that it has since become legal for Saudi girls to ride bicycles. Perhaps someday filmmaking will become more common there, and male and female crew members can work openly together.

Naturally Wadjda was made with a digital camera, since this new technology is crucial to the spread of filmmaking in places like the Middle East where there is little money or equipment for production. In contrast, Capote was shown in a beautiful widescreen 35mm print that looked great spread across the entire width of the Virginia’s huge screen. Naturally the screening became a tribute to the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, giving his only Oscar-winning performance (out of four nominations) in the lead role.

Barker had brought with him a surprise guest, Capote‘s director, Bennett Miller, whose appearance had not been announced in advance. He discussed how he and scriptwriter Dan Futterman learned that there was a second, rival Capote film in the works, Infamous (2006), which also dealt with the period when the author was researching In Cold Blood. Miller and Futterman decided to press ahead, a wise move in that their film drew more attention than did Infamous. Much of the discussion was devoted to Hoffman’s performance and his acting style in general.

Capote was Miller’s first fiction feature. He had come to public attention with his documentary The Cruise (1998), which Roger had given a brief three-star review. Roger continued his support for Miller with a four-star review for Moneyball (2011). It’s a pity he did not live to see Miller’s latest, Foxcatcher, which will be playing in competition at Cannes in May.

Overlooked no longer

Perhaps no young filmmaker better demonstrates the impact that Roger’s support can have on a career than Ramin Bahrani. Roger saw his first feature, Man Push Cart, at Sundance in 2006 and invited it and the filmmaker to the  “Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

“Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

His second film, Chop Shop, brought him to Ebertfest a second time, in 2009. (Roger’s program notes are here, and his four-star review here.) At about that time, Bahrani’s third film, Goodbye Solo, was released. Given its modest budget, it did reasonably well at the box office, grossing nearly a million dollars worldwide (in contrast to Man Push Cart‘s roughly $56 thousand). Bahrani inched toward mainstream filmmaking with At Any Price (2012), starring Dennis Quaid and Zac Efron, and he is currently in post-production on 99 Homes, with Andrew Garfield, Michael Shannon, and Laura Dern. During the onstage discussion, he spoke of struggling to maintain a balance between the indie spirit of his earlier films and the more popularly oriented films he has recently made.

Bahrani visited Ebertfest for a third time this year, belatedly showing Goodbye Solo. We had enjoyed this film when it came out, and it holds up very well on a second viewing. It’s a simple story of opposites coming together by chance. An irrepressibly talkative, friendly immigrant cab driver, Solo (a nickname for Souléymane), becomes concerned when a dour elderly man engages him for a one-way trip to a regional park whose main feature is a windy cliff. He fears that William is planning suicide. Solo arranges to drive William whenever he calls for a cab and even becomes his roommate in a cheap hotel. Gradually, with the help of his young stepdaughter Alex, he seems to draw William out of his defensive shell.

As in Bahrani’s earlier films the main character is an immigrant and played by one, using his own first name (Souléymane Sy Savané). He’s the main character in that we are with him almost constantly, seeing William only as he does. William is a vital counterpart to him, however. He is perfectly embodied by Red West, an actor who worked for Elvis Presley and did stunt work and bit parts in films and television since the late 1950s. He may look vaguely familiar to some viewers, but he’s not really recognizable as a star and comes across convincingly as an aging man buffeted by life’s misfortunes.

Most of the film takes place in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Bahrani’s hometown, with many moody, atmospheric shots of the cityscape at night. One crucial scene involves a drive into the woods and mountains, however, and much of it is filmed in a dense fog. One questioner from the audience asked if Bahrani had planned to shoot in such weather or if, given his short shooting schedule, the fog turned out to be a hindrance to him. He responded that he had dreamed of being able to shoot in fog and that the weather cooperated on the three days planned for that locale. In fact, he re-shot some images as the fog became denser, to keep the scene fairly consistent.

Bahrani’s presence at Ebertfest spans half its existence, from 2006 to 2014. As the festival becomes more diverse in its offerings, it is good to have him back as a reminder of the Ebertfest’s early emphasis on the “overlooked.”

Of Paramount importance

Logo for National Telefilm Associates, TV syndication arm of Republic Pictures.

DB here:

Among the guests at this year’s E-fest was Barry C. Allen. For over a decade Barry was Executive Director of Film Preservation and Archival Resources for Paramount. That meant that he had to find, protect, and preserve the film and television assets of the company—including not just the Paramount-labeled product but libraries that Paramount acquired. Most notable among the latter was the Republic Pictures collection.

We may think of Republic as primarily a B studio, but it produced several significant films in the 1940s and 1950s—The Red Pony, The Great Flammarion, Macbeth, Moonrise, and Johnny Guitar. John Wayne became the most famous Republic star in films like Dark Command, Angel and the Badman, and Sands of Iwo Jima. John Ford’s The Quiet Man was Wayne’s last for the studio, which folded in 1959. Next time you see one of the gorgeous prints or digital copies of that classic, thank Barry for his deep background work that underlies the ongoing work of his dedicated colleagues.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Hard as it may seem for young people today to believe, in the 1950s TV stations routinely cut the films they showed. Packages of 16mm prints circulated to local stations, and these showings were sponsored by local businesses. Commercials had to be inserted (usually eight per show), and the films had to be fitted to specific lengths.

WISH-TV ran three movies a day, and two of those would be trimmed to 90-minute air slots. That meant reducing the film, regardless of length, to 67-68 minutes. Barry’s job was to look for scenes to omit—usually the opening portions—and smoothly remove them. Fortunately for purists, the late movie, running at 11:30, was usually shown uncut, and then the station would sign off.

By coincidence I recently saw a TV print of Union Depot (Warners, 1932) that had several minutes of the opening exposition lopped off. We who have Turner Classic Movies don’t realize how lucky we are. Fortunately for film collectors, some stations, like Barry’s, retained the trims and put them back into the prints.

While working at WISH-TV, Barry began booking films part-time. He programmed some art cinemas in the Indianapolis area during the early 1970s, mixing classic fare (Marx Brothers), current cult movies (Night of the Living Dead), and arthouse releases like Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie—a bigger hit than anyone had anticipated. He also helped arrange a visit of Gloria Swanson with Queen Kelly; she carried the nitrate reels in her baggage.

At the same time, Barry was learning the new world of video editing, with ¾” tape and telecine. Because of his experience in television, Barry was contacted by Paramount to become Director of Domestic Syndication Operations. His chief duty was to deliver films to TV stations via tape, satellite, and prints. From that position, he moved to the preservation role he held until 2010, when he retired.

Barry is a true film fan. He has reread Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By many times and retains his love for classic cinema. The film that converted him to foreign-language cinema was, as for many of his generation, Children of Paradise, but he retains a fondness for Juliet of the Spirits, The Lady Killers, and other mainstays of the arthouse circuit of his (and my) day. He’s proudest of his work preserving John Wayne’s pre-Stagecoach films.

It was a great pleasure to hang out with Barry at Ebertfest. Talking with him reminded me that The Industry has long housed many sophisticated intellectuals and cinephiles. Not every suit is a crass bureaucrat.

Young-ish adult

Patton Oswalt had planned to come to Ebertfest in an earlier year, to accompany Big Fan and to show Kind Hearts and Coronets to an undergrad audience. He had to withdraw, but he showed up this year. On Wednesday night he screened The Taking of Pelham 123 to an enthusiastic campus crowd, and the following night, after getting his Golden Thumb, he talked about Young Adult. (Roger’s review is here.)

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

It’s common for viewers to notice that Mavis Gary, the malevolent, disturbed main character of Young Adult, doesn’t change or learn. “Anti-arc and anti-growth,” Oswalt called the movie. I found the film intriguing because structurally, it seems to be that rare romantic comedy centered on the antagonist.

Mavis returns to her home town to seduce her old boyfriend, who’s now a happy husband and father. A more conventional plot would be organized around Buddy and his family. In that version we’d share their perspective on the action and we’d see Mavis as a disruptive force menacing their happiness.

What screenwriter Diablo Cody has done, I think, is built the film around what most plots would consider the villain. So it’s not surprising that there’s no change; villains often persist in their wickedness to the point of death. Attaching our viewpoint to the traditional antagonist not only creates new comic possibilities, mostly based on Mavis’s growing desperation and her obliviousness to her social gaffes. The movie comes off as more sour and outrageous than it would if Buddy and Beth had been the center of the plot.

Making us side with the villain also allows Oswalt, as Matt Freehauf, to play a more active role as Mavis’s counselor. In a more traditional film, he’d probably be rewritten to be a friend of Buddy’s. Here he’s the wisecracking voice of sanity, reminding Mavis of her selfishness while still being enough in thrall to high-school values to find her fascinating. As in Shakespearean comedy, though, the spoiler is expelled from the green world that she threatens. It’s just that here, we go in and out of it with her and see that her illusions remain intact. Maybe we also share her sense that the good people can be fairly boring.

All you can eat

There aren’t any villains in Ann Hui’s A Simple Life, a film we first saw in Vancouver back in 2011. Roger had hoped to bring it last year, but Ann couldn’t come, as she was working on her upcoming release, The Golden Era. This year she was free to accompany the film that had a special meaning for Roger at that point in his life.

The quietness of the film is exemplary. It’s an effort to make a drama out of everyday happenings—people working, eating, sharing a home, getting sick, worrying about money, helping friends, and all the other stuff that fills most of our time. The two central characters are, as Roger’s review puts it, “two inward people” who are simple and decent. Yet Ann’s script and direction, and the playing of Deanie Yip Tak-han and Andy Lau Tak-wah, give us a full-length portrait of a relationship in which each depends on the other.

Roger Leung takes Ah-Tao, his amah, or all-purpose servant, pretty much for granted. She feeds him, watches out for his health, cleans the apartment, even packs for his business trips. When he’s not loping to and from his film shoot, he’s impassively chowing down her cooking and staring at the TV. A sudden stroke incapacitates her, and now comes the first surprise. A conventional plot would show her resisting being sent to a nursing home, but she insists on going. Having worked for Roger’s family for sixty years, Ah-Tao can’t accept being waited upon in the apartment. So she moves to a home, where most of the film takes place.

A Simple Life resists the chance to play up dramas in the facility. Thanks to a mixture of amateur actors and non-actors, the film has a documentary quality. It captures in a matter-of-fact way the grim side of the place—slack jaws, staring eyes, pervasive smells. (A small touch: Ah-Tao stuffs tissue into her nostrils when she heads to the toilet.) Mostly, however, we get a sense of the facility’s everyday routines as the seasons change. The dramas are minuscule. Occasionally the old folks snap at one another, and one visitor gets testy with her mother-in-law. One woman dies (in a bit of cinematic trickery, Ann suggests that it’s Ah-Tao), and an old man who keeps borrowing money is revealed to have a bit of a secret. It’s suggested that a pleasant young woman working at the care facility will become Roger’s new amah, but that seems not to happen. The prospect of a romance with her is evoked only to be dispelled.

Ah-Tao’s health crisis has made Roger more self-reliant, but his life has become much emptier. He seems to realize this in a late scene, when he stands in the hospital deciding how to handle Ah-Tao’s final illness. Throughout the film, food has been a multifaceted image of caring, community, friendship, childhood (Roger’s friends recall Ah-Tao cooking for them), and even the afterlife. Ah-Tao and Roger rewrite the Ecclesiastes line about what’s proper to every season by filling in favorite dishes. As he mulls over Ah-Tao’s fate, Roger is, of course, eating. But it’s cheap takeaway noodles and soda pop. This silent scene measures his, and her, loss better than any dialogue could.

The art of American agitprop

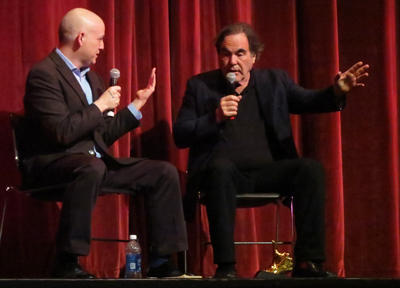

Matt Zoller Seitz and Oliver Stone on stage at the Virginia Theatre.

A Simple Life is a very quiet film. Ebertfest’s highest-profile visitors brought along two of the noisiest movies of 1989. It’s the twenty-fifth anniversary of Do The Right Thing (Roger’s review) and Born on the Fourth of July (Roger’s review), and seen in successive nights they seemed to me to put the “agitation” into agitprop.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

The ending has become the most controversial part of the film. It’s here that Lee was, I think, especially forceful. The crowd in the street is aghast at the killing of Radio Raheem by a ferocious cop, but what really triggers the riot is Mookie’s act of smashing the pizzeria window. I’ve always taken this as Mookie finally choosing sides. He has sat the fence throughout–befriending one of Sal’s sons and quarreling with the other, supporting Sal in some moments but ragging him in others. Now he focuses the issue: Are property rights (Sal’s sovereignty over his business) more important than human life? Moreover, in a crisis, Mookie must ally himself with the people he lives with, not the Italian-Americans who drive in every day. It’s a courageous scene because it risks making viewers, especially white viewers, turn against that charming character, but I can’t imagine the action concluding any other way. Lee had to move the project to Universal from Paramount, where the suits wanted Mookie and Sal to hug at the end.

Staking so much on social allegory, the film sacrifices characterization. Characters tend to stand for social roles and attitudes rather than stand on their own as individuals. The actors’ performances, especially their line readings, keep the roles fresh, though, and the film still looks magnificent. I was struck this time by the extravagance of its visual style. In almost every scene Lee tweaks things pictorially through angles, color saturation, slow-motion, short and long lenses, and the like–extravagant noodlings that may be the filmic equivalent of street graffiti.

By the end, in order to underscore the confrontation of Radio Raheem and Sal, Lee and DP Ernest Dickerson go all out with clashing, steeply canted wide-angle shots. (We’ve seen a few before, but not so many together and usually not so close.) Having dialed things up pretty far, the movie has to go to 10.

In Born on the Fourth of July, Stone more or less starts at 11 and dials up from there. Beginning with boys playing soldier and shifting to an Independence Day parade that for scale and pomp would do justice to V-J Day, the movie announces itself as larger than life. The storyline is pretty straightforward, much simpler than that of Do The Right Thing. A keen young patriot fired up with JFK’s anti-Communist fervor plunges into the savage inferno of Viet Nam. Coming back haunted and paralyzed, Ron Kovic is still a fervent America-firster until he sees college kids pounded by cops during a demonstration. This sets him thinking, and eventually, after finding no solace in the fleshpots of Mexico, he returns to join the anti-war movement.

Even more than Lee, Stone sacrifices characterization and plot density to a larger message. The Kovic character arc suits Cruise, who built his early career on playing overconfident striplings who get whacked by reality. But again characterization is played down in favor of symbolic typicality. While there’s a suggestion that Ron Kovic joins the Marines partly to prove his manhood after losing a crucial wrestling match, the plot also insists that his hectoring mother and community pressure force him to live up to the model of patriotic young America. He becomes an emblem of every young man who went to prove his loyalty to Mom and apple pie.

Likewise, Ron’s almost-girlfriend in high school becomes a college activist and so their reunion–and her indifference to his concern for her–is subsumed to a larger political point. (The hippies forget the vets.) We learn almost nothing about the friend who also goes into service; when they reunite back home, their exchanges consist mostly of more reflections on the awfulness of the war. Later Cruise is betrayed, almost casually, by an activist who turns out to be a narc. But this man is scarcely identified, let alone given motives: he’s there to remind us that the cops planted moles among the movement.

What fills in for characterization is spectacle. I don’t mean vast action; Stone explained that he had quite a limited budget, and crowds were at a premium. Instead, what’s showcased, as in Do The Right Thing, is a dazzling cinematic technique.

Visiting the UW-Madison campus just before coming to Urbana for Ebertfest, Stone offered some filmmaking advice: “Tell it fast, tell it excitingly.” The excitement here comes from slamming whip pans, thunderous sound, various degrees of slow-motion, silhouettes, jerky cuts, Steadicam trailing, handheld shots, all jammed into the wide, wide frame. Every crack is filled with icons and noises–flags, whirring choppers, kids with toy guns, prancing blondes, commentative music. “Soldier Boy” plays on the supermarket Muzak when Ron is telling Donna about his plans.

By the time Ron visits the family of the comrade he accidentally killed, Stone finds another method of visual italicization: the split-focus diopter that creates slightly surreal depth.

Since so many scenes have consisted of a flurry of intensified techniques, simple over-the-shoulder reverse shots might let the excitement level drop. So a new optical device aims to deliver fresh impact in one of the film’s quietest moments.

Like Lee, Stone took the Virginia Theatre audience behind the scenes. He agreed with William Friedkin, who was originally slated to do the film: “This is as close as you’ll every come to Frank Capra.” Instead of using the shuffled time scheme of Kovic’s autobiography, Friedkin advised that “This is good corn. Write it straight through.” Hence the film breaks into distinct chapters, each about half an hour long and sometimes tagged with dates. They operate as blocks measuring phases of Ron’s conversion. Like many filmmakers of his period, Stone deliberately made each chapter pictorially distinct–the low-contrast Life-magazine colors of the opening parade versus the lava-like orange of the beachfront battle.

Stone pointed out that this film marked the beginning of his career as a figure of public controversy. Like Lee, he was attacked from many sides, and from then on he was a lightning rod. Matt Zoller Seitz (who’s preparing a book on Stone) pointed out that at the period, he was astonishingly prolific. From 1986 (Salvador, Platoon) to 1999 (Any Given Sunday), he directed twelve features, about one a year.

Lee was hyperactive as well over the same years, releasing fourteen films. And neither has stopped. Lee’s new film is the Kickstarter-funded Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, while Stone is touring to support the DVD release of his 2012 documentary series, The Untold History of the United States. Both men like to work, and more important, they’re driven by their ideas as well as their feelings. By seeking new ways to agitate us, they impart an inflammatory energy to everything they try. And in giving them a chance to share their insights and intelligence with audiences outside the Cannes-Berlin-Venice circuit, Ebertfest once again demonstrates its uniqueness. Roger would be proud.

The introductions and Q&A sessions for most of the films, as well as the morning panel discussions, have been posted on Ebertfest’s YouTube page. Program notes for each film are online; see this schedule and click on the title.

For historical background on Barry Allen’s work as an editor of syndicated TV prints, see Eric Hoyt’s new book Hollywood Vault: Film Libraries Before Home Video.

P. S. 1 May 2014: Thanks to Ramin S. Khanjani for pointing out that Ramin Bahrani had worked on other films before Man Push Cart. These included one feature he made in Iran, Biganegan (Strangers, 2000); it got only limited play in festivals and apparently a few theaters. I can’t find information about the others online, and presumably they were shorts and/or did not receive distribution. (K.T.)

Ann Hui, with Kristin, gets into the spirit of Ebertfest. David is represented in absentia by the Dots.

Cheers, R.

We owe Roger an enormous debt. Since we met in 1999 at the Arts Club of Chicago, Roger has been the most generous and eloquent supporter our work has had. In our visits to their festival, Roger and Chaz welcomed us into their community and introduced us to people who have become good friends. Roger came to our Wisconsin Film Festival twice, and his presence gave it a burst of energy. In Roger and Chaz we found a couple engaged passionately in the act of living in, and for, each other.

Our larger debt is to the lessons Roger taught us, and thousands of others: Writing about film can exemplify writing about life. Friendship and good humor must inform everything you do. Punishing health problems need not kill your appetite for experience, for fellowship, and for the life of the mind.

In Roger’s memory, each of us offers some personal reflections.

Kristin here:

As with so many other people, my first acquaintance with Roger was through his and partner Gene Siskel’s television review shows. I’m not sure when David and I started watching. At first we were partly attracted by the fact that each review included a clip from the movie. TV reviewing was such a new form that the studios didn’t put together montages of shots to provide the reviewers. You got to see an actual scene as it appeared in the film, something that could give you a sense of whether or not you wanted to see the film. Later the edited-together shots from various parts of the film came to be more like a trailer than a sample. They don’t tell you much about the film. But Gene and Roger did, so we kept watching.

We noticed the fact that Gene and especially Roger would often promote films that were in release but not likely to be known to most of the show’s viewers. Small independent films and foreign films, which the pair urged people to try and see in theaters or, increasingly, on video. These were the same sorts of films that became the core of Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival. Few reviewers writing for a mass audience have bothered regularly to call attention to worthy independent and art-cinema fare.

When we met Roger in the late 1990s, the first thing that struck me was that in person he seemed exactly the same as on TV. On the air he didn’t put on a public persona or try to entertain us at the expense of giving us less information about the film in question. Those were the early days of the infotainment boom. As its name suggests, infotainment coverage means that the reporters and reviewers feel obliged to be as entertaining as the news (or pseudo-news) they present. I think of another reviewer in the early days, Gene Shalit, who started out presenting reasonably informative review segments on the Today Show. Increasingly, however, his eccentric appearance, with large, frizzy hair and an oversize mustache, combined with his breezy, pun-filled delivery made his segment into a sort of comic interlude that barely qualified as a film review. In other words, the opposite of Roger.

Over the next several years, David got to know Roger better than I did. He helped squire Roger around during his 2003 visit to the Wisconsin Film Festival and wrote introductions to his books. I was in the early years of working on an Egyptian archaeological expedition, and in 2003 I was struggling to get my big project on the Lord of the Rings franchise (published as The Frodo Franchise in 2007) off the ground.

During that time I managed to go with David to the Overlooked Film Festival and enjoyed it very much. There Roger’s zeal for introducing general audiences to relatively obscure films was boiled down to its essence. The enthusiasm of the loyal attendees was contagious, as was Roger’s joy in sharing his love for the films and giving the audience access to the stars and filmmakers who were his friends.

From 2003 to 2006, I was dashing around the world, interviewing people in New Zealand, Los Angeles, Silicon Valley, London, Copenhagen, and elsewhere for my book. By the spring of 2006 I had talked with 75 people and acquired the knowledge I need to write most of my chapters. Game producers and designers filled me in on the video-game aspect of the franchise; festival-heads and distributors enlightened me on the impact of the trilogy on the international independent film market.

But there was a crucial piece of the puzzle missing. My fourth chapter was to be on the rise of modern infotainment journalism, covering such topics as press junkets, the replacement of paper press kits replaced with EPKs (electronic press kits), and the rise of making-of promo films on cable. I knew how press junkets work, with their endless strings of short interviews where the reporters ask the same questions over and over–and the fact that studio employees did the filming and editing of the interviews. I had talked to cast and crew members about the Lord of the Rings junkets. (Ian McKellen: “Someone will come forward and say, ‘I know you get asked all sorts of questions. I’m not going to ask you the questions everybody else asks you, so I’m going to say, “What is the question that you’re most asked?”‘”) But I didn’t know much about how such things got established historically or how they looked from the viewpoint of the journalist interviewer. Unfortunately, nobody had written a history of press junkets.

It occurred to me that Roger was an expert on such subjects. His career as a reviewer got going in the mid- to late 1960s, when the studios were increasingly using press junkets, and he had not only witnessed but participated in the expansion of film coverage from print into television. Roger happened to be slated to visit the Wisconsin Film Festival in the spring of 2006. I asked him if he would be willing to let me interview him on such topics. Despite a heavy schedule, he agreed. The only time he could fit me in was over breakfast on April 2. I went to his hotel and talked with him for about half an hour. (David came to pick us up and snapped the photo above; my recorder is under the list of questions I had concocted. Roger has toast and coffee, back in those happy days when he could still eat.)

The result was everything I could have hoped. With his razor-sharp memory, Roger gave me invaluable historical information and insights. For example, I asked why reporters ask questions to which they already know the answers:

Because the sessions are so short, and because the nature of television is that you have to get them to say it. They get pretty stupid questions. For example, I may well know who Hilary Swank plays in Million Dollar Baby, but it doesn’t work on television unless she says, “I play a woman who wants to be a boxer.” You have to have her saying it. So you say, “Well, tell me about this character you play.”

It was a delightful and fruitful interview, supplying that last piece of the puzzle. It also happened to be the last interview I did before finishing the book a few months later and sending the manuscript to the press.

That June, Roger had his disastrous health crisis, ending up in a coma until August. Of course, he lived on to give us a tremendous amount of insightful writing on film and his own life and his view of the world in general. But I was very grateful to have had that interview with him while he could still speak. As anyone who has done much live interviewing knows, it’s very different from interviewing by email. The conversation takes unexpected turns and generates questions that weren’t on the original list. I’m still thankful for that interview, not just for the selfish reason that it enhanced my book. I’m also glad that I got some of the valuable information that Roger had in his memory but had never included in his voluminous writings. He was a living document of modern film history, and inevitably much of what he knew never got written down. At least I captured a bit of it.

I think that interview gave Roger a better sense of me as a film scholar. We also happened to start this blog later that year, in late September. I doubt that Roger had time to read every entry, but he read many of them and helped get the blog established by linking to it. We didn’t like to pester such a busy man, but we notified him when we posted something that we thought related to his interests. (My skepticism about 3D matched his, for example.) Here’s the last time he linked to one of my entries, with his characteristic generosity and the occasional typos that resulted from the speed with which he poured out his thoughts on FaceBook and twitter:

I think he must also have realized that, despite the fact that our interview was on a recent blockbuster franchise, one of my specialties is silent cinema. I got invited to the 2007 Overlooked Film Festival to be one of the “expert group of colleagues” who were to help fill in for Roger during his recuperation. I introduced Raoul Walsh’s Sadie Thompson and after the screening was on the panel that chatted with the three members of the Alloy Orchestra.

In 2008 the event changed its name to what most of us called it already, Ebertfest. I was now sort of the unofficial silent-film expert. I got to introduce a luminous print of von Sternberg’s Underworld, which I had never seen in 35mm, and to lead the post-screening discussion with the Alloy members. (My program notes for the event are here.) The same thing happened the following year with The Last Command. It’s a pity that the Alloy team never accompanied Docks of New York at Ebertfest, completing the survey of von Sternberg’s trio of silent masterpieces.

I missed the 2010 festival, needing to be at the site of Tell el-Amarna for my Egyptology work. But I returned in 2011 to introduce and discuss a screening of the nearly complete version of Metropolis, recently restored.

In 2012 I again needed to be in Egypt during Ebertfest, so the 2011 festival was the last time I saw Roger in person. But we kept in contact by email. That could be a delightful process, as David shows in the second half of this entry.

DB here:

Werner Herzog, Roger Ebert, and Paul Cox, Ebertfest 2007.

From different perspectives, I’ve set forth my sense of Roger’s contribution to film culture. On this site we’ve covered Ebertfest over the years, and I reviewed Life Itself. In addition, the University of Chicago Press has generously made my introductions to Awake in the Dark and The Great Movies III available online (here and here). After Roger’s death last week, I wrote a brief tribute for the UW Antenna site. Still to come is a valedictory piece for Film Comment, to be available in print and online.

So today, when Roger is ceaselessly on our minds, I thought: Why would anyone want to listen to me when they could listen to him? You can hear (and watch) him in the vast video archive of Siskel & Ebert. But maybe I can bring you his voice in another way.

Combing through a decade’s worth of emails, I found some bits that seem worth sharing. A subject line “From Roger” always marked an email worth reading, and the inevitable sign-off, “Cheers, R.,” left you wanting more. I can hear him speaking these words, even in the years when he had no voice. Maybe you will too.

Apparently almost all G-rated animation will now be in 3-D! I hear IMAX will show nothing but 3-D (via digital). No more celluloid! Traditional IMAX process is dead. The vulgarians are at the gates. (2008)

Have you seen Chop Shop? I’m showing it at Ebertfest. Sort of an American indie neorealist picture. And in 70mm, a new print, Baraka. Best Blu-ray I’ve ever seen. Most critics liked Coraline even more than I did. (2009)

Just saw Ponyo. The opening undersea sequence is miraculous. Manohla Dargis was right about Perfect Getaway: A good B movie. (2009)

I hated Les Miz, of course. Falling dirges, rising dirges, ditties, boilerplate. (2013)

I am often guilty of getting carried away by films that will not stand the test of time, although I do think that The Dark Knight will continue to be interesting. (2009)

I always said I would not retire until I had a book about Scorsese. Now I do, and I can’t retire until I have one about Herzog! (2008)

I remember Scorsese saying he watched Black Narcissus at least once a day for a week. (2012)

[I wrote that Donald Richie was recovering his health:] So I hear! Walking around the room, likes the new place with English-speaking help, health on the mend. What a dear man. His film of The Inland Sea is wonderful but the book and his Journals are really special. So honest and matter of fact. (2010)

[On images in a blog entry on Andrew Sarris:] How moving it was to see the photos of old friends like Arthur Knight and Hollis Alpert. Remember when the Saturday Review was eagerly awaited? I met Arthur and Marianne in 1968, on the notorious Warner/Seven Arts week-long junket which flew planeloads of critics to the Bahamas. I was a kid. They immediately invited me to their home and through them I met many Hollywood figures.

God, Arthur loved his pipe, and his sacramental martini formula. I never drank a martini except at his house, and there nothing else. The way he made one approached the psychedelic. Marianne was a costume designer. . . . They bought a house on the beach at Malibu when such things could be had for less than millions. Their Saturday open houses were gatherings of interesting people, including some (like Blake Edwards’ doctor) later immortalized in films. (2012)

[In the midst of Ebertfest, Roger took time to write:] I’ll write more later….but be sure to buy the News-Gazette before you leave town. There’s a wonderful photo of Kristin, Richard [Leskovsky], and Nina [Paley] (2009).

[When I posted this entry about the Jem movie theatre in Harmony, Minnesota, Roger commented on this picture.]

That photograph, seemingly so artless and matter-of-fact, speaks deeply to me. The color, the shadows, the girls in conversation. (2012)

Chaz and I are at Cannes, I having survived the trip in surprisingly good shape. Lots of big names, but as Frémaux says, “They have to prove themselves every time.” (2009)

In high school, I went to popular movies with dates and attended the Art Theater mostly alone. In college there was a period when I sort of stopped going to popular movies—more art films and film societies. (2011)

I have a lifelong policy of never making lists of anything except my annual Best 10. Can’t tell you how much time I saved by not compiling Halloween movie lists. (2011)

I am so happy the festival is approaching and Kristin and you and I can sit again in the same room with good movies. (2010)

[When I replied that Kristin couldn’t attend that year because she was needed for her archaeological dig in Egypt: ] And my Egyptian correspondent Wael Khairy will be in Urbana! So the balance of the earth won’t be altered. He is a very gifted film critic. . . . He has two more weeks to wait until the ban on his writing is lifted. It was imposed after he led a (successful) effort against the censors to remove the Arabic subtitles from the CENTER of the screen on Avatar. (2010)

[On the musicians in Woodstock:] I, like you, was not focused on rock in the 1960s. I had to ask Chaz who some of the performers were. These days, I know nobody. (2009)

Do you remember that nice Indian kid sitting next to you at Ebertfest? I met him through my blog when he was 15. He had been making films since he was 6. His father was going to accompany him…but unexpectedly died shortly before. His dad approved of the visit, so Krishna came with his lovely mother and sister. I love this kid. (2012)

You know where the Westerns have gone for an audience? Video games, that’s where…as long as you look for the right type of western. John Wayne. John Wayne. I think it was Montaigne who said: “Everyone needs a name like that.” (2009)

[I wrote him that watching movies is good, but maybe reading is better:] You know, I think I agree with you. I doubled my “reading” by adding audiotapes of books that don’t call out to be intensely read. I’ve listened to about 100. The single most spellbinding performance I’ve heard is Sean Barrett doing Perfume. (2008)

[I sent him a link in which David Brooks returns from an expedition into the Midwest, recalls his admiration for White Castle, and declares his new preference for Steak ‘n Shake]: Yeah, but he strays off the point pretty quickly. And I don’t know anyone who prefers White Castle to S ‘n S….although late boozy nights in my 20s often called for a bag of sliders. Californians are passionate that In ‘n Out makes better burgers than Steak ‘n Shake. I contend that the very names of the two chains dramatically contrast the styles of sexual intercourse in the two regions. (2012)

I have been honored out! Above all I need to focus on writing. Sounds harsh, but everything’s an effort these days…. (January 2013)

[The University of Chicago Press sent him my Foreword to Awake in the Dark and he replied]: I felt as if, after 38 years of plugging away, someone had understood just what I have been trying to do. I work for a newspaper, I get categorized as a newspaper reviewer. I am proud to be one. But I have also tried to stretch the limits of the form. I think of myself as being a teacher as much as a writer, and I like my forum because it gives me a lot of readers. . . .

That you mentioned Shaw took my breath away. I have been reading Shaw for 40 years, starting by reading every one of his Prefaces, from which I learned that it is quite all right to stray entirely from the subject, or approach it from an unexpected angle. In the last few months I’ve been reading his collected music criticism. I don’t know a thing about music, but that was an advantage, because I was able to focus on his language and strategy. His use of paradox and under- and overstatement is audacious, and I like the way he states even his most extreme positions as if they are simple common sense. (2005)

The last message I got, on 15 March 2013, referred to the 2013 Ebertfest schedule. It contained only one word.

Hooray!

Cheers, R.

On the block adjacent to the Virginia Theatre, off South State Street, Champaign, Illinois.

An all-too-short visit to Ebertfest 13

Tulip’s unique way of expressing delight at the prospect of walkies.

Kristin here–

With David still recovering from pneumonia, I drove down to Champaign-Urbana by myself for a truncated Ebertfest visit. As always,  the event began with a reception at the president’s home, where Roger delivered a speech via his talking computer (left).

the event began with a reception at the president’s home, where Roger delivered a speech via his talking computer (left).

This year, rather than kicking off the festival with a Wednesday-night screening of a 70mm print, the opening program was a screening of the restored version of Metropolis, incorporating footage found in Argentina. (David has already blogged about the new version, having seen it last year at the Hong Kong Film Festival.) I had the privilege of introducing the screening.

Roger’s program notes gave a good summary of the film and its latest restoration, so I talked a little about why it’s not all the odd that a nearly complete print should be found in Argentina. First there’s the matter of what happened to prints at the end of their theatrical circulation in the silent era. Films didn’t open around the world day and date the way they do now. Prints might be exhibited in one country, then move onto another with new intertitles in a different language cut in. They might be shown for years, until their useful life was over. By that point they might have reached places far away from their place of origin. They were also usually covered with scratches and lines, and they weren’t worth the cost of shipping them back to their makers. They might be buried, as was the case with the 1978 Dawson City find in Alaska, or stored in the attic of a theater, or rescued by a projectionist who tucked them away in a garage. In some cases, collectors acquired them, as happened with the Argentinian Metropolis print. Occasionally these treasures come to light, as recently happened when the Film Archive of New Zealand located several American titles, such as John Ford’s lost silent film Upstream. So far-flung places that long ago were the end of the line for prints are where we might expect them to resurface. Indeed, New Zealand’s archive also held a print of Metropolis that contained some shots not found in earlier restorations or in the Argentinian print, and these appear in this latest version.

A second reason why Argentina is not a surprising place to find a long print of Metropolis has to do with the German film industry’s strength after World War I. Despite having been defeated, the country built up its production until it was second only to Hollywood. European companies found it difficult to sell their films in the U.S.; then, as now, American films dominated their domestic market. German companies sought other areas where they could compete on a more equal footing. They were quite successful in South America, and Fritz Lang’s films were among the most popular there. Small wonder, than, that a well-worn, largely complete print should survive there.

The original score has been reconstructed, but as has become customary at Ebertfest, the Alloy Orchestra supplied their own original accompaniment. (See below.)

Dog-lovers’ delight

The thing that sets Ebertfest apart from other festivals is that it reflects the taste of one person. Roger chooses the films, and his reviews are reprinted in the program as notes. When Roger saw the acclaimed animated film My Dog Tulip, based on J. R. Ackerley’s memoir about life with his Alsatian, he was reminded of another man whose only love was his dog, Umberto D. So, having the ability to program of double feature of the two films, Roger did. Apart from the annual silent film, Ebertfest seldom shows older classics, so this was something of a departure. I had only seen a 16mm copy of Umberto D, way back in my graduate-school days, so it was great to see a 35mm print on the big Virginia Theater screen.

The juxtaposition of the two films worked well, with the grim image of old age and despair of Umberto D followed by the nostalgic but fairly upbeat My Dog Tulip. Judging by the questions and comments afterward, the latter struck a particular chord with dog lovers in the audience, and during the remainder of my stay I heard many pet anecdotes exchanged among people around me.

The film was created by a husband-wife team, with Paul Fierlinger drawing on a digital tablet and Sandra Fierlinger painting in the colors with a computer program. As I pointed out during the panel discussion after Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues was shown at Ebertfest in 2009, computer animation doesn’t mean that the computer does all the work. Far from it. A computer has to have a lot of material fed into it before it can aid in the filmmaking process. Each frame of My Dog Tulip was done by hand, and it has the look of traditional cel animation. (As with traditional cel animation, the Fierlingers use each image twice in a row, so that only twelve drawings suffice for a second of film.) There’s a deliberately rough, slightly jittery look to the outlines of the figures in the shots, helping give that impression of drawn animation.

Ordinarily I would have preferred to see the film in 35mm, but Paul and Sandra told me that the 35mm prints actually washed out some of the vibrancy of the intended colors. The digital print projected at Ebertfest definitely did the colors justice.

Matt Soller Zeitz with Paul and Sandra Fierlinger onstage after the screening

Filling the big screen

On Friday, two very well-known directors presented beautiful, color, widescreen 35mm prints that looked terrific–and huge–on the big screen. (I was sitting in the second row for one, the first row for the other, so the effect was particularly overwhelming.) I had missed Richard Linklater’s most recent release, Me and Orson Welles, in first run, so it was a pleasure to catch up with it. As all the reviewers remarked, Christian McKay uncannily impersonates the real Orson Welles. As Linklater pointed out, McKay was in his  mid-30s at the time of filming, while Welles was a mere 22 during the time depicted–and yet the portrayal works, since Welles didn’t really look young, even at the beginning of his career.

mid-30s at the time of filming, while Welles was a mere 22 during the time depicted–and yet the portrayal works, since Welles didn’t really look young, even at the beginning of his career.

The film pulls a great deal of humor out of rehearsals for Welles’s famous 1937 staging of Julius Caesar, with the director’s whims and ego dominating the proceedings, and Zac Efron’s stagestruck high-school kid providing a naive point of view of the backstage politicking. Given all the antics in the lead-up to the premiere, it’s impressive that Linklater manages to switch gears abruptly and present snippets from the production itself that genuinely suggest the impact of Welles’s revolutionary staging. It wowed New York and pioneered the way for modern-dress versions of the Bard’s works.

The on-stage discussion after the film revealed that the production, which manages to convey 1930s New York so convincingly, was mostly shot on the Isle of Man. The British island not only offered favorable production incentives, but it boasted a well-preserved local playhouse that could double for the long-since-destroyed Mercury Theater.

That evening veteran director Norman Jewison presented one of his less well-known films, Only You (1994). It’s a screwball, absurdly romantic comedy starring Marisa Tomei and Robert Downey Jr., both looking very young and very gorgeous.

After Jewison moved from television into feature films in the 1960s, his early projects included two Doris Day and Rock Hudson comedies (The Thrill of It All and Send Me No Flowers), and he returned to the genre with Moonstruck.

Only You has a slender plot in which the heroine, convinced that a Ouija board has given her the name of the man she will marry, abandons her fiancé to follow a man she thinks is her destined true love across Italy. Cinematography by Sven Nykvist and location shooting in Venice, Rome, and Positano give the film considerable charm.

David has been recovering well, but I didn’t want to leave him alone too long. I returned home today rather than staying through the entire festival. But it was a wonderful few days, and I enjoyed talking with Michael Barker, Paul and Sandra Fierlinger, Kevin Lee, Michael Phillips, David Poland (when he wasn’t busy chasing his lively 15-month-old son), some of Roger’s “Far-flung Correspondents,” and many of the devoted audience members who return year after year to this unique event. With luck, both David and I will be there for the whole event next year.

(From the Ebertfest website)

Note: For a second year, the introductions, post-film discussions, and morning panels were streamed live, and they’re also archived online.

Festival as repertory

DB here:

This picture points backward and forward. It looks back to the days when movies were shown on a big screen to hundreds of people in real time. No pausing or fast forwarding; you take what you get. Some viewers are settled in pretty close to the screen, and a few dare to sit in the front row. (Save me the center seat, fortunately still vacant.) The critic sits slumped far back, implying coolly distant appraisal. The pen is poised to note down moments of power, beauty, or stupidity.

But the big auditorium is nearly empty, and this makes the drawing foreshadow the approaching end of moviegoing. The warning signs are emerging: Visit any movie, even an Imax spectacular, in the off-hours (Monday through Wednesday, especially matinees) and you’re likely to find the house as empty as it is here. As for the critic, ready to jot down notes for a review: An anachronism these days, as many will tell you.

But wait. Isn’t the theatrical business booming? We’re told that 2009 was a banner year, and 2010 will be even better. True, worldwide admissions for 2009 totaled $29.9 billion, a new high. But the increase, according to the MPAA, is mostly due to 3D. In the US, the format accounted for 11 % of the country’s $10.6 billion box-office income, a sum about equal to the gain over last year’s take. Moreover, the number of domestic tickets sold increased only a little from recent years, to 1.4 billion. Overall, the years 2005-2009 have fallen off from the high points of 2002-2004, when attendance was 1.5 billion or more.

Nor is the international film industry expanding its audience. For the last five years or so, worldwide attendance has been remarkably flat, with only the Asia-Pacific region seeing signs of growth. Overall, it seems, 3D serves to let Hollywood hang on to its audience, and charge more.

The spurt in theatrical income helps offset the decline of packaged media. The DVD sell-through boom lasted from 1998 to about 2008, when subscription rental companies (Netflix, Lovefilm) and kiosks (Redbox et al) pushed down retail sales. The slump was accelerated by a glut of DVD releases, big-box stores offering discs at rock-bottom prices, the rise of downloading and video on demand, and, not least, a massive recession that made consumers cost-conscious. Today, many industry observers think that young people are more inclined to graze in the luxuriance of YouTube than visit the multiplex. At best, the Millennials might watch a current hit streaming on their cellphones or laptops or TV monitor. An admittedly small-scale inquiry in the recent Screen Digest (April, p. 100; here, but proprietary) suggests that most young entertainment fans don’t feel a need to rent a disc, let alone buy one. Moreover, all those sampled saw far more movies on monitors, often through shady downloads, than on theatre screens.

It’s not hard to imagine a near future when a movie opens simultaneously on the global market to satisfy its most devoted public before moving in a very few weeks to DVD, VOD, iTunes, and other digital platforms. It then snuggles into hundreds of thousands of hard drives around the world, ready to be awakened when somebody feels the urge to watch. These seem to be the two poles we’re moving toward: the brief big-screen shotgun blast, and the limbo of everlasting virtual access. You can argue that the very success of home video, cable, and the internet have cheapened our sense of a movie’s identity.

Which is one reason why film festivals are very, very important.

Apocalypse then and now

I’ve spent most of the last several weeks at festivals. The Hong Kong International Film Festival is a 2 1/2 week showcase of global cinema, attached to a major regional market assembly and spiced with local attractions and international retrospectives. The Wisconsin Film Festival is a 4 1/2 day local event highlighting US independent cinema but with a leavening of recent arthouse titles and restored classics. Ebertfest, formerly Roger Ebert’s Festival of Overlooked Films, is a topical festival held in a single venue, featuring a wide array of guests, and reflecting its founder’s eclectic tastes.

Each offers unique pleasures, and each reaffirms the value of the theatrical motion-picture experience. I’ve already written a bit about Hong Kong here and here and here, and I hope to write more about the Wisconsin event soon. For now I’ll concentrate on a few high points of Ebertfest, which took Roger’s cartoon above as its emblem. Kristin and I have been guests for many years (our posts are in the Festivals: Ebertfest category on the right), but this time she was in Egypt scouring the sands for pieces of statues. So I’ve had to blog solo.

Fortunately, we now have a vast archive of what happened in Urbana. With the generosity typical of Roger’s event, all the Q & A sessions and panel discussions were recorded and streamed. They’re available here. And for an appreciative account of what it all means, see Jim Emerson’s piece on Roger’s site.

Start with the obvious. Apocalypse Now Redux was shown in a Technicolor restoration in the Virginia Theatre, a picture palace built in 1926. The image loomed, the sound engulfed you. Several people, most of them young, told me that they felt privileged to have seen the film, for once in their lives, as it must be seen. As soon as you get a home theatre that matches this presentation in sheer primal impact, call me. I’m coming over.

Editor and sound designer Walter Murch, one of my heroes, was prevented from coming by the European volcano ash. So I tried in my introduction to pay homage to what is surely one of the most complex soundtracks of any film of the period—a mixture of synthesizer, rock and roll, and layer upon layer of subtly enhanced noises. During the screening I was able to appreciate some of the daring soundfields Murch created. When Willard gets up to look out the blinds of his Saigon hotel, the sound in the left and right and surround channels narrows abruptly to the central speaker, bringing him back to mundane R & R reality. Later, most ordinary dialogue comes from the central speaker, but when Willard voices his commentary, we hear him from all three front speakers; the soft tone creates an intimacy, while the auditory spread gives it weight and authority.

A panel of commentators including Ali Arikan, Michael Phillips, and Janet Pierson did a fine job of probing various aspects of the film. Ali considers it Coppola’s crowning achievement and one of the great American films. Michael, by contrast, thought that what he aptly called the “terror and grandeur” of its opening half gives way to off-kilter and pretentious scenes in Kurtz’s compound. Janet, who had seen the film on the big screen more often than any of us, found it an enduringly impressive accomplishment in both sound and image. With the audience we had a lively exchange about the role of women in the film and the inclusion of the notorious French plantation sequence. Matt Zoller Seitz made a shrewd point about how the film shows Americans bringing along homegrown entertainments (Playmate performances, rock music, surfing) to redefine the war in familiar terms.

Despite all the shock and awe, I like the film only moderately. It’s a stunning logistical accomplishment, and it has some brilliant moments; but I think it has problems almost as soon as Willard moves upriver. I might be the only person who finds the Kilgore scenes overdrawn, almost Dr. Strangeloveish. When Kurtz bends down to give water to the wounded Vietnamese, he’s interrupted by news of surfing, and he yanks his canteen away as the VC scrabbles for it.

Heavy, heavy—as is the repeated motif of Americans strafing civilians and then tending to their wounds. Willard spells it out: “We cut them in half and then give them a Band-Aid.” Yet I still admire the utterly disorienting opening, which mixes thrumming choppers with ceiling fans and justifies what Michael Herr called it: the rock-and-roll war. Later we’ll see battles wreathed in psychedelic haze, and a hallucinatory assault on the bridge, with Willard stumbling through the dark and watching battle-fried infantrymen hurl ordnance into a void. It’s like a light show at the climax of a rock concert.

One of my favorite comments about the movie came during Dick Cavett’s television show circa 1980. Dick asked Jean-Luc Godard what he thought of Apocalypse Now. This was a period in which most of the press coverage obsessed about the film’s soaring budget. Godard remarked that Coppola had not spent enough. Cavett asked for an explanation. Godard: “Well, he spent only fifty million dollars and the war cost fifty billion. You cannot film this war on such a small budget.” That’s the way I remember it, anyhow.

From Rwanda to LA

Quick notes on two other E’fest titles. (I’ve already discussed Departures here.)

“I wanted to make a film for a Rwandan audience.” Not what you might expect to hear from an American director of Korean descent. Accordingly, Lee Isaac Chung gave Munyurangabo a leisurely pace and structure. The plot centers on two young men, Sangwa and Munyurangabo (aka Ngabo), taking what seems to be an enigmatic journey. One is Hutu, the other Tutsi. Longish takes and fairly distant framings follow them hitchhiking and stopping over at Sangwa’s home. Gradually, hints such as Ngabo’s carefully wrapped machete suggest that they are heading toward a confrontation. When the revelation comes, our attachment shifts from Sangwa and his family conflicts to Ngabo’s mission of vengeance. Chung explained that the soundtrack develops accordingly, moving from objectivity to subjectivity as we start to hear what his two protagonists hear.

The production background, explained by Chung and his colleagues Sam Anderson (co-writer and producer) and Jenny Lund (co-producer and sound recordist), was fascinating. The script consisted largely of a scene outline, and the dialogue was developed with the actors. The Americans worked with translators in guiding the performances. In some cases they drew on their own experiences. Perhaps partly because of its respect for everyday life, the film has been shown on local television and in the Parliament. It has become a Rwandan film.

My colleague J. J. Murphy has written an acute analysis of Munyurangabo. He rightly praises the sudden entrance of a bardic young man who recites a six-minute poem celebrating liberation and reconciliation. The performance wasn’t planned, Chung said, but it has become a high point of the film. J. J. also links to other enlightening interviews given by Chung, Anderson, and Lund.

If Munyurangabo’s loose structure evokes the Dardennes brothers, Michael Tolkin’s The New Age has the coiled-serpent dramaturgy of a classic psychodrama-comedy. It’s 1994, and a prosperous LA couple is suddenly without income. Facing bankruptcy, Katherine and Peter auction off their paintings, try to borrow from Peter’s father, and eventually open a boutique catering to the tastes of their friends. At the same time they slide into casual affairs and ceremonies of New Age spirituality. Ebert’s review captures the movie’s range of reference:

Tolkin gives us one richly detailed set piece after another, involving luncheons, openings, massages, telephone tag, psychic consultations, sex, heartfelt conversation, and pagan rituals led by a bald-headed woman who sees what others cannot see. Meanwhile, the material universe remains the one thing Peter and Katherine can really count on.

Few American films examine money and class, but this one is actually about needing a paycheck. By the end, when each of our protagonists becomes a seller rather than a buyer, we have seen a remarkably sharp dissection of a lifestyle.

In the Q & A afterward, Tolkin said that the genesis of the film came from watching a Melrose shop sink into failure. When I saw the film on its initial release, lines like “It’s not an insult, it’s an intervention” and “We need space” (psychological, but also retail) leaned me toward taking the film as satire. I still do. But Tolkin insists that it’s not. The plot dares to have two truly repellant protagonists, but Tolkin doesn’t find them nasty. “I like them.” He majored in religion in college and he takes his characters’ beliefs, no matter how shallow, seriously—not a big surprise from the creator of The Rapture.

He elaborated on some differences between novels and films. When he rereads one of his novels, he thinks, “How was I ever that smart?” but when he rewatches a film it’s the imperfections that jump out. A movie has to be more compressed and rhythmically varied than a novel—something The New Age demonstrates in its brisk montages alternating with slowly unfolding scenes. In the discussion Jim Emerson praised the film’s density of detail, Tolkin elaborated by invoking William Carlos Williams’ belief in compact expression.

The next two paragraphs include plot details you may prefer to pass over.

Tolkin’s script is indeed firmly contoured. The couple’s crucial quarrel takes place at the thirty-minute mark and launches the two major plot lines. They decide to try a separation (while sharing the house), and they launch their boutique. The development section begins about halfway through, as they conduct their love affairs and watch the shop founder. The last act presents their options: bankruptcy, suicide, low-end work.

Arguably the climax is Peter’s desperate effort to make his first telemarketing sale. Here, I think, Tolkin’s ambivalent sympathies come out. Early in the film Peter had asked a cold-caller whether he ever thought he’d be doing this as a career; it’s less a moral condemnation than glib snobbery. But when Peter has to close the sale, his self-loathing is mixed with a certain pride. The cashiered ad exec finds that he can do this. He’s on the road back.

The gorgeously designed movie, with hard blacks and saturated primaries, has a developing palette (“swatches for each act,” Tolkin says). Unhappily, I can’t study the design arc here because The New Age seems never to have had a DVD release. So much for the Celestial Multiplex. Good old 35mm pulled us through, in a radiant print.

Scholars seem now to agree that film festivals serve as an alternative international distribution system. Like Hollywood’s more formal and routinized machine, festivals bring movies to audiences. Usually the movies are current ones, and a festival is offering local viewers their only chance to see such pictures before video release.

Ebertfest shows that there’s an essential place for what we might call the repertory festival. That’s one that revives and reappraises films from earlier periods—and “earlier” may mean only a few years ago. Jumping from 1929 (Man with a Movie Camera, accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra) to the 1980s (Apocalypse Now, Barfly) and the 1990s (The New Age) and then right up to 2008 (Vincent, Trucker, Departures, Synecdoche, New York, Song Sung Blue), this year’s edition reminds us that every film, old or new, is a part of history.

To come fully into history, I’m convinced, a film needs scale. Even intimate dramas attain their true gravity when spread out like a gigantic picnic on a pale blanket. It’s not the only way to enjoy cinema, certainly; but it’s one that we must never abandon. Like the note-taker in the back row and the geeks up front, everyone needs a full view.

Apocalypse Now Redux.

PS 28 April: I just discovered this piece by Steven Zeitchik, who argues that reviving classics in a big-screen event format could also be good business.