Archive for the 'Directors: Weerasethakul' Category

ADD = Analog, digital, dreaming

Luther Price, Sorry Horns (handmade glass slide, 2012).

DB here, just back from the Toronto International Film Festival:

It’s commonly said that any substantial-sized film festival is really many festivals. Each viewer carves her way through a large mass of movies, and often no two viewers see any of the same films. But things scale up dramatically when you get to the big boys: Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and Toronto. I’ve never been to the first three, but my first visit to TIFF was like wading into pounding surf and letting the current carry me off.

This is the combinatorial explosion of film festivals: A hefty 450-page catalog listing over 300 films from 60 countries. Moreover, because it’s both an audience festival and an industry festival where movies are bought, sold, and launched, you observe a range of viewing strategies. Although I sit too close to be much bothered, my friends tell me of mavens darting in and out of shows or checking their cellphones during slow stretches of what’s onscreen. The crowds add to the air of electric excitement, as of course do the visits of glamorous celebs.

So I was inundated. How to choose what to see in 3 ½ days for viewing? (I reserved time for industry panels.) I knew that some of the prime titles, such as Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love or the remarkable-looking Leviathan, would be available for Kristin and me at Vancouver later in the month. And I saw no reason to stand in queues for Looper, Argo, and other movies that I could see in empty Madison, Wisconsin multiplexes during off-peak hours.

I still missed many, many things I wanted to catch. For much wider assessment of major movies, you should go to the coverage offered by the tireless scouts of Cinema Scope and the no less tireless scouts of MUBI. Here I’ll talk just about a few films that made me think about—no surprise—digital vs. analog moviemaking.

Fragments and figments

Mekong Hotel.

Stephen Tung Wai’s Tai Chi 0 (0 as in zero) represents everything we think of when we say that digital production and postproduction have transformed cinema. This kung-fu fantasy from the Chinese mainland (but using Hong Kong talent, including the director) retrofits the genre for the video-game generation. CGI rules. The result is, predictably, monstrous fantasy—a globular iron behemoth, a sort of Steampunk locomotive version of the Death Star—but also screens within screens, GPS swoops, tagged images, Pop-Up bubbles identifying the cast, and other scribbling that turns the movie screen into a multi-windowed computer monitor. One more thing Scott Pilgrim must answer for.

Jang Sun-woo played with similar possibilities in his 2002 Resurrection of the Little Match Girl, inserting character dossiers and creating digital effects mimicking gamescapes. But he sometimes paused to give these images a dreamlike langor. Tai Chi 0 never lingers on anything and instead carries the level of busyness to crazier heights. In a panel at the Asian Film Summit, Fung explained that one scene of the film was inspired by a particular online game. Sammo Hung was playing Fruit Ninja or something similar and Fung decided to include a scene of villagers turning away invading soldiers with a barrage of produce.

Fung said as well that fantasy martial arts remains a blockbuster genre in the PRC (viz. the success of Painted Skin: The Resurrection). Tai Chi 0 ends on a cliff-hanger, the end titles (rolled too fast to read) provide a trailer for part 2, and apparently a third part is in the works. Now China has franchise fever.

The stop-and-start plot is familiar from Hong Kong films of the 70s onward (including over-made-up gwailo villains), but its execution wrecks nearly everything I like about classic kung-fu movies. Clearly though, I’m not in the audience the movie is aimed at. My friend Li Cheuk-to, artistic director of the Hong Kong International Festival, opined that this digital froth could be very appealing to China’s online generation.

Tai Chi 0 exemplifies what academics writing on digital have talked about as the “loss of the real.” As Tom Gunning pointed out back in 2004, though, things aren’t so simple. Digital photography, after all, remains photography. The lens intercepts a sheaf of light rays and fastens their array on a medium. The fact that a shot can be reworked in postproduction doesn’t mean that every digital image must surrender the tangible things of this world.

At TIFF, the power of digital cinema to bear witness was on display in Sion Sono’s Land of Hope. Sono has already documented Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Himizu, which I haven’t seen, but in that and Land of Hope, he abandons the wacko bad taste that made Love Exposure and Cold Fish so memorable. This is a sober, traditional drama presented with straightforward economy. It takes place in a fictitious district, Nagashima, but the fact that the name combines “Nagasaki” and “Hiroshima” suggests the gravity of Sono’s approach.

Three couples’ lives are torn apart by the quake, the tsunami, and the collapse of the nearby nuclear power plant. (All of these catastrophes are kept offscreen, glimpsed in TV reportage.) The oldest couple refuses to evacuate, clinging to their farm. Their son and his wife move to a nearby city where they succumb to the fear of radiation affecting their unborn child. And an unmarried couple wander the ruins looking for the girl’s father.

Sono intercuts the three lines of action. The old farmer adroitly manages his wife’s dementia and lets her indulge her fantasy of dancing in a village festival. In a critique of Japanese conformity, the young couple is shown being mocked for their worries about radiation poisoning. (The wife seals their apartment and, in a touch recalling the grotesque side of Sono, takes to wearing a Hazmat suit.) Less sharply developed are the fairly aimless ramblings of the youngest couple, though Sono injects some suspense when they dodge police blockades. At intervals, plaintive Mahler (a Sono weakness) surges up to underscore the futility of their search.

Throughout, government reassurances and the media’s insistence on putting on a happy face are treated with robust skepticism. Instead, Sono celebrates a dogged persistence to get through each day. The young couple’s mantra of “one step, one step” supplies the upbeat tone of the last scenes. As affecting as you’d expect is the footage of areas around the plant, seen as a wintry wasteland. Like Rossellini filming in bombed Berlin in Germany Year Zero, Sono has shot precious footage of ruins that testify to a calamity in which nature conspired with human blunders. And he did it digitally.

You can’t expect something so conventionally dramatic from Apichatpang Weerasethakul, and Mekong Hotel doesn’t supply it. It’s as relaxed as Tai Chi 0 is frenetic, and its central conceit makes it another pendant to Uncle Boonmee. The boy Tong and the girl Phon meet from time to time on the terrace of the hotel overlooking the river. They talk about folk traditions and the flood then besieging Thailand. They also encounter spirits that are as tangible, even mundane as they are; Phon’s dead mother appears in her room occasionally knitting. More shocking are the ghosts called Pobs who seem to possess the characters and make them hunch over and gobble intestines, sometimes in situations that suggest the organs have been torn from another character. All these scenes are handled with the usual Weerasethakul tact: long-take long shots, usually one per scene, that push the everyday and the extraordinary to the same unruffled level.

Mekong Hotel seems to operate on two planes of time. On the image track and in the dialogue, we witness Tong and Phon on the terrace or walking along the river. But the music, snatches of repetitive guitar tunes, seems to come from another time frame. At the start we see a guitarist practicing, and his noodlings run almost constantly under the drama we see. Another motif, fixed and lustrous shots of the Mekong River, yields a visual if not dramatic climax: a slowly paced choreography of Jet-skis crisscrossing the water. Here the digital medium may work to Weerasethakul’s advantage, with the clouds and landscape hanging unmoving over the racing watercraft, as a single, slow ship wades into the middle of their oscillating geometry.

The analog alternative

I suspect that Olivier Assayas filmed Something in the Air (originally Après Mai) on film, but even if he didn’t, the movie is a tribute to analog reproduction–mimeograph machines, LPs and turntables, and cinema in its different guises, from exploitation films to agitprop and experimental lyrics. We all know that the 1960s continued well into the 1970s, and here Assayas shows the uneasy carryover with a mixture of sympathy and critical detachment. The film starts with our high-school protagonist Gilles carving a peace symbol into his desk, flagrantly ignoring the teacher’s lecture. The shot encapsulates the film’s tension between political activism and image-making, and Gilles will oscillate between them in the course of the plot.

The poles come to be represented by two young women—the wealthy and ethereal Laure for whom he makes his paintings and the more hardheaded leftist rebel Christine, who goes out with him and others on nightly graffiti raids. When Laure leaves for London, Gilles continues his painting while leafleting and splashing slogans on walls, with the occasional Molotov cocktail to spice things up. The copains’ rebellion leads to some harm, but they cling to their ideals.

The poles come to be represented by two young women—the wealthy and ethereal Laure for whom he makes his paintings and the more hardheaded leftist rebel Christine, who goes out with him and others on nightly graffiti raids. When Laure leaves for London, Gilles continues his painting while leafleting and splashing slogans on walls, with the occasional Molotov cocktail to spice things up. The copains’ rebellion leads to some harm, but they cling to their ideals.

When summer comes, Gilles joins a film collective headed to document workers’ struggles in Italy. He encounters the arguments that made me smile in nostalgia: Shouldn’t revolutionary content have a revolutionary form? But how shall we reach the working class if our films are opaque? Assayas, who grew in this period and was repelled by the Maoist dogmatism of Cahiers du cinéma and Cinéthique, evokes these debates to remind us that the counterculture was about art and political change at one and the same time. Something in the Air chronicles a few years when imagination mattered.

After an early, shocking clash of students pounded down in a police riot, the film adopts a more circumspect rhythm, salting its scenes with books, magazines, record albums, and songs of the time. The plot keeps our interest by delaying exposition about the characters’ family lives until rather late. When we learn that Gilles’ father writes scripts for the celebrated Maigret TV series, we’re invited to see his forays into abstract painting as his form of teen rebellion. The plot doesn’t mind straying a bit from Gilles, as when his friend Alain, another aspiring artist, gets caught up in the fervor and pursues a wispy red-haired American dancer.

Characters meet, work or play together, drift apart, re-converge, and eventually settle into something like grown-up life. But at the end, when Gilles has apparently been absorbed into commercial filmmaking in London, he is granted one last vision of one of his Muses, who reaches out for him from the screen of the Electric Cinema.

Analog triumphs as well in The Master. Sitting in the front row of Screen 1 at the TIFF Lightbox (see below), I was astonished at the 70mm image before me. Not a scratch, not a speck of dust, not a streak of chemicals, and no grain. So did it have that cold, gleaming purity that digital is supposed to buy us? Not to my eye. The opening shot of a boat’s wake, which will pop up elsewhere in the movie, was of a sonorous blue and creamy white that seemed utterly filmic. Now we know the way to make movies look fabulous: Shoot them on 65.

The Master, as everybody now knows, centers on Freddie Quell, an explosive WWII vet, and his absoption into a spiritual cult run by the flamboyant Lancaster Dodd. Followers of The Cause are encouraged, through gentle but mind-numbingly repetitious exercises, to probe their minds and reveal their pasts. With the air of a charming rogue in the young Orson Welles mold, Dodd seems the soul of sympathy. But like Freddie he’s capable of bursts of rage, especially when his methods are questioned. Freddie becomes a sidekick because of Dodd’s fondness for his moonshine, while he also serves as a test case for the efficacity of The Cause’s “processing” therapies. If you can get this hard-bitten, borderline-sociopath in touch with his spiritual side, you can help, or fleece, anybody.

Like There Will Be Blood, this movie is primarily a character study. That film gained plot propulsion from Daniel Plainview’s oil projects, but many situations worked primarily to reveal facets of his dazzling self-presentation, his repertoire of strategies for dominating others. Something similar happens with Dodd and the ways he charms his congregation. But here the action is more episodic and the point-of-view attachment is dispersed across two characters. Dodd’s counterbalancing figure, the clenched Freddie, is so difficult to grasp psychologically (at least for me) that the film didn’t seem to build to the sort of dramatic, even grotesque peaks we find in other Anderson projects.

This is also a story about an institution, a quasi-church with a pecking order, rules, and roles. I wanted to know more about how The Cause worked, how it recruited people, and how it garnered money. Laura Dern plays a wealthy patron who lets the group stay in her home, and at one point Dodd is arrested for embezzling from the foundation, but the details of his crime aren’t explained. I also wanted to know more about the group’s doctrine, which seems so vague that Scientology need not worry about being targeted. The rapid-fire catechisms between Dodd and his acolytes are gripping enough, as Q & A dialogue usually is, but what system of beliefs lies behind them? The film seems to fall back on the familiar surrogate father/son dynamics at the center of most Anderson movies, but here filled in less concretely.

In short, after one screening I was left thinking the film was somewhat diffuse and flat. But I need to see it again. I thought better of Boogie Nights and Punch-Drunk Love after re-viewing them, so I look forward to trying to sync up with The Master on another occasion. Alas, in Madison, Wisconsin, I won’t have a 70mm image to entice me.

A bit of each, and both

Luther Price, No. 9 (handmade glass slide, 2012).

Analog imagery came into its own on other occasions, notably during the two programs of experimental films gathered under the heading “Wavelengths.” (At one I spotted Michael Snow in the audience.) Expertly curated by Andréa Picard, these programs assembled some strong, provocative films by several young filmmakers. I won’t review each one here–Michael Sicinski provides very useful commentary on nearly all those I saw—but I must mention the striking slide show that served as an overture one evening. The images didn’t move, exactly, but they might as well have.

Luther Price has been making remarkable films on 8mm and 16mm for several years, and one Wavelength program featured his Sorry Horns, a three-minute mix of abstraction and found footage. The same mix was evident in the procession of stunning handmade glass slides. Many, like the one surmounting today’s entry, evoke early cinema, decay, and clichéd Christian imagery: the wounds of film deterioration become cinema’s stigmata. Even the sprocket holes and soundtracks are invaded by festering particles. Arp-like blobs, pockmarked faces, and spliced and sliced movie frames lie under grids as irregular as medieval leaded windows. This is all gloriously analog.

No less captivating is the new, 100% digital work of an even older master of American avant-garde cinema. In one Wavelengths program Ernie Gehr offered us Departure (2012), a train trip playing on optical illusions in the spirit of Structural Film. We all know what it’s like to sit on a stationary train but then feel, when another train passes, as if we’ve started to move. Gehr translates this kinesthetic illusion into optical terms by filming, first upside down and then in judicious framings, several railbeds rushing by, faster and faster.

These layered ribbons sometimes unfurl right, sometimes left, and sometimes simply hover there as fixed, pulsating strips, all but losing the details of rail and tie and spike. Sometimes the one on top moves right, the grass verge beside it moves left, and the bottom track moves right (or left). This creation of flip-flop movement harks back to Side/Walk/Shuttle (1991) and to Gehr’s 1974 exercise in traffic abstraction Shift, which filmed patterns of commuter traffic from a very high angle.

Accompanying Departure was one of nineteen pieces in Gehr’s Auto-Collider series. Most of them contain some recognizable imagery, Gehr explains, but not number XV, the one we saw. In a sense the distilled essence of Departure, that film’s whooshing planes become vibrant, and vibrating, stacks of bold color, a bit like Daniel Buren in a joyous mood.

How did Gehr create the gorgeous Auto-Collider images? He declined to explain. Kristin suggested a plausible means to me, but I’m keeping quiet. In the analog age, when new methods of abstraction required a lot of sweat equity, filmmakers freely explained their painstaking work with lenses, light, and optical printers. But digital video practice flattens the learning curve. Powerful discoveries like Gehr’s or Phil Solomon’s are very easily replicated without much time, toil, or talent. Hell, somebody would make an app for them.

These artists are right to have trade secrets, just as magicians do. We should be satisfied merely to look. What we see reminds us that both analog and digital media harbor possibilities that go beyond the ability to replicate phenomenal reality. Both media can also dazzle us with things we’ve never seen, or imagined.

Digital projection seems to be taking over the festival scene, if TIFF is any indication. Cameron Bailey reports in a tweet that of the 362 films screened, 232 (64%) were in the Digital Cinema Package format and another 79 (21%) were in HDCam. The remainining 51 (15%) were in 16mm, 35mm, and 70mm.

Are the digital items still films? Robert Koehler suggested that maybe we will start calling everything movies. Interestingly, at the Wavelengths screenings, the artists called their artworks (whether on film or on digital video) “pieces.” Me, I still vote for calling films films, even if they’re on video, just as we have books in digital formats (such as, oh, I don’t know, this one). For me, at least these days, a film is a moving-image display big or small, whether it’s on film or some other medium. For some purposes we may want to specify further: Just as e-book and graphic novel indicate a platform or a publishing format, TV movie or video clip tells us more about what kind of film we have.

See also my January entry on festival problems with digital projection.

Thanks to Cameron Bailey, Andréa Picard, and their colleagues for enabling my visit to TIFF.

The industry screening of The Master at TIFF. Photo by M. Dargis.

Books, an essential part of any stimulus plan

The Pathé Palace theatre, Brussels, designed by Paul Hamesse.

DB here:

Some shamefully brief notes on new publications. Disclaimer: All are by friends. Modified disclaimer: I have excellent taste in friends.

You call me reductive like that’s a bad thing

It’s easy to see why we might tell each other factual stories. We have an appetite for information, and knowing more stuff helps us cope with the social and natural world. We can also imagine why people tell fictitious stories that we think are true. Liars want to gain power by creating false beliefs in others. But now comes the puzzle. Why do we spend so much of our time telling one another stories that neither side believes?

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

The standard objection to an evolutionary approach to art is that it’s reductive. It supposedly robs an individual artwork of its unique flavor, or it boils art-making down to something it isn’t, something blindly biological. Art is supposed to be really, really special. We want it to be far removed from primate hierarchies, mating behavior, or gossip. For a typical criticism along these lines, see this review of Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct. Brian has already adroitly responded to this sort of complaint here. See also Joseph Carroll’s examination of reductivism on his site.

It seems to me that all worthwhile explanations are reductive in some way. They simplify and idealize the phenomenon (usually known as “messy reality”) by highlighting certain causes and functions. This doesn’t make such explanations inherently wrong, since some questions can be plausibly answered in such terms. For example, often the literary theorist is asking questions about regularities, those patterns that emerge across a variety of texts. That question already indicates that the researcher isn’t trying to capture reality in all its cacophony. (For me, it’s all about the questions.)

Literary humanists sometimes talk as if they want explanations to be as complex as the thing being explained. But that would be like asking for the map to be as detailed as the territory. In fact, however, humanists tacitly recognize that explanations can’t capture every twitch and bump of the phenomenon. Consider some types of explanations that are common in the humanities: Culture made this happen. Race/ class/ gender / all the above caused that. Whatever the usefulness of these constructs, it’s hard to claim that they’re not “reductive”—that is to say, selective, idealized, and more abstract than the movie or novel being examined. Likewise, when people decry evolutionary aesthetics for its “universalist” impulse, I want to ask: Don’t many academics take culture or the social construction of gender to be universals?

I want to write more about Brian’s remarkable book when I talk about our annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. For now, I’ll just quote Steven Pinker’s praise for On the Origin of Stories: “This is an insightful, erudite, and thoroughly original work. Aside from illuminating the human love of fiction, it proves that consilience between the humanities and sciences can enrich both fields of knowledge.”

Faded beauties of Belgium

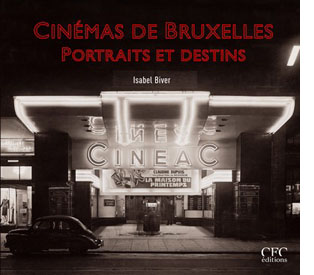

In its day, Brussels played host to some fabulous picture palaces. Now after years of research Isabel Biver has given us a deluxe book, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins. It’s the most comprehensive volume I know on any city’s cinemas.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Then there was the Pathé Palace, shown at the top of this entry. Dating back to 1913, it boasted 2500 places and included cafes and even a garden. This imposing Art Nouveau building was designed by Paul Hamesse, probably the city’s most inspired theatre architect. Hamesse also created the Agora Palace, which opened in 1922. Huge (nearly 3000 seats), the Agora was one of the most luxurious film theatres in Europe.

And we can’t forget the Métropole, the very incarnation of the modern style. Sinuous in its Art Deco lines, it packed in 3000 viewers. When it opened in 1932, it attracted nearly 53,000 spectators during its first week. The neon on the Métropole’s façade lit up the night, and its two-tiered glassed-in mezzanine became as much a spectacle as the films inside. See the still at the bottom of this earlier entry of mine. A ghost of its former self still sits on the Rue Neuve. Local historians consider the failure to preserve the Métropole a scandal in the city’s architectural history.

Cinémas de Bruxelles is a model presentation of local theatres. Not only does it trace the history of the major houses, but it includes a glossary of terms, a large bibliography, and an index of all theatres, both central and suburban. Needless to say, it is gorgeously illustrated. Whether or not you read French, I think you would enjoy this book, for it evokes an age we’re all nostalgic for, even if we didn’t live through it.

A TV interview with Isabel in French is here, with glimpses of what remains of the Métropole. She also gives guided tours of the remaining cinemas in the city center and in the neighborhoods. More information here.

A guy named Joe

Tropical Malady.

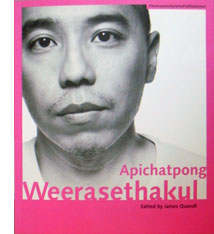

It’s seldom that a young filmmaker gets a hefty book devoted to him. Apichatpong Weerasethakul (aka Joe) will turn forty next year. He comes from Thailand, not a country adept at negotiating world film culture, and he is known chiefly for only four features. Yet he has become one of the most admired filmmakers on the festival circuit. His films are apparently very simple, usually built on parallel narratives. They have a relaxed tempo, exploiting long takes, often shot from a fixed vantage point, and scenes whose story points emerge very gradually. Joe’s movies tease your imagination while captivating your eyes. Each one could earn the title of his first feature: Mysterious Object at Noon.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

James’ introductory essay, as evocative and eloquent as usual, is virtually a monograph, discussing all the features in depth. Alongside it are discerning essays by other old hands. Tony Rayns offers his usual incisive observations, focusing largely on Joe’s short films and the recurring imagery of hospitals, while Benedict Anderson surveys the Thai reception of Tropical Malady. Karen Newman offers precious information and judgments about Joe’s installations. The director himself signs several essays and participates in interviews and exchanges. Even Tilda Swinton has something to say.

I remember when Mysterious Object at Noon played the Brussels festival Cinédécouvertes in 2000. I was baffled. Joe’s movies taught me to watch them, and finally with Syndromes and a Century I got in sync. Its austere lyricism, off-center humor, and patiently unfolding echoes win me over every time I see it. (You can search this blogsite for several mentions, but JJ Murphy has a fuller appreciation of Syndromes here.) Thanks to Alexander Horwath and his colleagues for making this wonderful anthology, decked out with color stills and rich bibliography and filmography, available to us—and in English.

Zap goes the Chazen

Zap, Snarf, Subvert, Young Lust, Tits & Clits, Air Pirates Funnies, Slow Death Funnies, Feds ‘n’ Heads, Corn Fed Comics, Dope Comix, Cocaine Comix, Corporate Crime Comics: The names define the era. The sixties didn’t end until the mid-1970s, and these outrageous cartoon books really came into their own after the election of Nixon in 1968.

On 2 May, the Chazen Museum on our campus launches its exhibition, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix, 1963-1990. A whirlwind of events, including films and lectures, will revolve around galleries full of imagery from the demented pens of Kim Deitch, Aline Kominsky Crumb, Trina Robbins, Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, and many other cartoonists.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

For some years Jim has been telling me about his efforts to mount the comix show. It’s no small matter to collect this elusive material and then persuade a museum to show it. Not too many galleries feature talking penises, Jesus visiting a faculty party, or Mickey and Minnie robbed at gunpoint by a dope dealer. Maybe we forget, in the age of the Web and The Onion, just how scabrous these things looked forty years ago. Actually, they still look scabrous. They also look pretty funny, and they’re often well-drawn. As a historical codicil, the exhibition includes 1980s images from artists extending the tradition, such as Drew Friedman and Charles Burns.

The show runs until 12 July 2009. If you can’t get to town, there’s the splendid catalogue. It includes essays by Jim and Denis, Jay Lynch, Patrick Rosenkranz, Trina Robbins, and Paul Buhle. There are free screenings of Fritz the Cat and Crumb at our Cinematheque. And you can read an interview with Jim about the show here.

Remember our motto: Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun.

Up next: Days and nights at Ebertfest.

The Eldorado Cinema, Brussels, designed by Marcel Chabot.

Tintin in movieland

For the number of films you can see on any given day, Brussels gives Paris a run for its money. It also has the advantage of efficiency. Several multiscreen repertory cinemas are within easy walking distance of one another, and normally the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique programs five different movies per day, plus a rotating program of another ten or so in another venue. For details on these venues, go here.

I’ve heard tales of Parisian cinephiles making the pilgrimage here to see films that their country had banned (e.g., Paths of Glory) or had not released in subtitled versions. I make my own pilgrimage every year, to watch films in the archive and to attend Cinédécouvertes, the annual festival that selects noteworthy items that don’t yet have a local distributor. For fifteen days, three titles are shown each night; you have two chances to see each one. It’s a great way to keep up with films that might not make it to the US or show up only on DVD.

The Cinémathèque, which runs the festival, provides prizes. A jury selects one or two best films, and a cash prize is awarded to a local distributor who agrees to acquire it. There’s also the Prix de l’Age d’or. Named in honor of Buñuel’s scandalous movie, this prize goes to a film that breaks with “cinematic conformism.” Past winners include Carlos Reygadas’ sober and disturbing Japon, Kornel Mundruczo’s frenzied hospital opera Johanna, and Paz Encina’s maximally minimalist Paraguayan Hammock.

The Palais des Beaux Arts is undergoing a huge renovation, and so the original venue, which I’ve visited almost every year for twenty-three years, is shut down.

The screenings have moved from this shell of a building to the Shell Building down the street. That location boasts a large foyer done in Postwar Euro Harmless Abstraction.

A much bigger venue than the old place, this is a fine auditorium, and attendance has been brisk.

Alas, using only one screen has cut the number of Cinémathèque programs considerably, but next year the renovated Musée will resume its two-screen, heavy-duty schedule. In the meantime, there are always Styx, Nova, Actors Studio, Movy Club, and Cinema Arenberg–with its admirable summer blitz Ecran Total.

A late arrival from Bologna, a heavy archive schedule, and persistent jet lag kept me from several films in the festival, most unhappily Harmony Korine’s Mr. Lonely. Of those I did see….

Shotgun Stories (Jeff Nichols, 2007) A man has two sets of sons by different wives, and the boys start to feud. A laconic US indie, apparently laid back but ready to spring into violence. I liked the unpretentiousness of it; quiet presentation of harsh conflict is often welcome.

The Optimists (Goran Paskaljevic, 2006) Five episodes set in today’s Serbia, with a popular comedian playing a different role in each one. It had that mixture of humor, melancholy, and fatalism that one finds in Eastern European films of the 1960s. A couple of the episodes seemed merely anecdotes, but one, about a crazed little boy taught by his parents to eat anything that appeals to him, is good dirty fun. Some lovely long takes, shot in digital video.

Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Thailand, 2006) I saw it in Vancouver last fall and couldn’t wait to see it again. Lyrical, finely paced, and unremittingly mysterious. A female doctor works in one clinic, a male one in another (now I get it); beyond that, the connections are teasingly obscure. A parallel-universe movie? A time-travel movie? Two halves of two uncompleted films? Political comment, though oblique, is there as well, most evident in a stockpile of artificial limbs in a hospital basement, adjacent to the military wing.

Mogari Forest (Kawase Naomi, Japan, 2007) Speaking of mystery, it’s ladled on pretty heavily in this Cannes Grand Prize winner. A woman working with the elderly in a care facility follows an old man into the forest; epiphany occurs. I have liked, mildly, Kawase’s earlier films Suzaku and Shara, but this one felt a little heavy-handed in its appeal to elemental forces. Still, the rhythm is engrossing, and it’s remarkably tactile, making you feel the dampness of loam and ferns.

Blue Eyelids (Ernesto Contreras, Mexico, 2007) At first I thought I was seeing a likable but unambitious commercial film about two lonely souls brought together. Then things slip sideways. A shy working woman wins a vacation trip for two, but she doesn’t really know anybody to ask along. She meets a former schoolmate and invites him. As they prepare for their holiday, their relationship becomes freighted with emotional investments. Nicely managed shifts in point of view both reveal and hide key information, and we get fine performances. But was the bird symbolism really necessary?

This year’s winners were Mogari Forest and Hotel Very Welcome (Sonja Heiss, Germany) for best films (10,000 euros each) and La influencia (Pedro Aguilera, Spain/ Mexico) for the L’age d’or prize (5,000 euros). Above, Cinémathèque director Gabrielle Claes introduces the jury.

Next time: Visiting the archive and checking out local cinemas (at last I catch Inland Empire). Maybe some beer as well.

Angles and perceptions; with a note on Thai censorship

Hide your face

“Angles alter perceptions,” notes a recent Newsweek story. You bet, as we say in Wisconsin. But intriguing evidence emerges from new research into videotaped confessions.

Over 500 jurisdictions now record confessions on video, we’re told. In virtually all instances, there’s only one camera, and it shows only the accused. That means, in movie terms, there are no reverse shots of the questioner.

What difference does it make? Quite a lot, it seems.

In Newsweek‘s words, “When a camera shows only a suspect’s face, studies show, potential jurors are more likely to believe the confession was voluntary and the suspect guilty than when it shows the faces of both suspect and interrogator.” The problem may also infect judges. Experiments conducted by G. Daniel Lassiter at Ohio University found that a sample of 21 judges appraised the confessions as more voluntary when the camera framed only the confessor and didn’t show the police officer.

The obvious worry is that we can’t be sure that the confession is voluntary if we don’t get any sight of the questioner. To take an extreme, but not fanciful, possibility, maybe the person offscreen is holding a weapon. But even if the questioner isn’t threatening the confessor, his or her facial expression will help us appraise the whole situation more fully. Is s/he reacting with sympathy, anger, or neutrality? Do the questioner’s facial expressions set a context for the questions asked? We can’t know, and this absence of knowledge may encourage us, by default, to side with authority and presume that the confession is genuine.

In fiction films, sometimes the camera doesn’t give us the reverse angle. It may simply dwell on one character, often when she or he is delivering a monologue. A close analog to the videotaped confession occurs in Truffaut’s 400 Blows when an offscreen therapist questions the boy Antoine about his life.

Several effects flow from Truffaut’s choice of this technique. The handling suggests a quasi-documentary objectivity in recording Antoine’s replies. Making the questioner unseen suggests that she won’t become a significant character, rather a voice that typifies the impersonal authority of the detention facility. The fact that the questioner is a woman reminds us of Antoine’s relation to his mother, an important topic in the interview. In all, this strategy concentrates on Antoine, letting us see new sides of his past and his mind.

In other scenes, I’ve noticed that suppressing the reverse angle not only showcased the character we see but also rendered the scene’s action more suspenseful or ambiguous. Recall the famous first shot of The Godfather, which concentrates on the mortician and refuses to supply the reactions of Don Vito.

The shot gives full sway to Bonasera’s monologue. At the same time, by slowly zooming back, the shot creates a growing suspense. To whom is he speaking? What is the listener’s reaction? Only at the end of Bonasera’s plea, when he rises to whisper in Vito’s ear, does Coppola supply the view of Don Vito—a big theatrical entrance for this character and the actor playing him.

Less operatic is an early scene in Sauvage Innocence (2001), by Philippe Garrel. The filmmaker François is going over his dead wife’s belongings, which his friend has preserved. Garrel gives us an establishing shot of the action, then, as the friend continues to talk, the camera concentrates on Francois’s reaction to the letters, poems, and photographs. Although his expressions are somewhat ambivalent, at least we can see them.

But in the next scene, a single shot lasting about seventy-five seconds, Garrel withholds the reverse angles that we’d normally get when his protagonist speaks. The camera favors the friend, a minor character, who asks questions about François’s new film while feeding a baby. François replies that he’s having trouble finding a producer, and if this last opportunity fails, the project will be over.

Garrel doesn’t choose to reveal François’s expression as he reports this critical state of affairs: no reverse shots. We must infer his emotional state from his voice, his pauses and sighs, and his postures as he replies, rises, and sits down.

At most we can assume that he’s dispirited, perhaps because of his film’s slim prospects and the reminder of his dead wife.

In the scene, there’s one glimpse of his face, as he turns slightly, and—Tim Smith might be able to confirm this—I’d bet that most viewers zero in on him at that moment. (The movement is centered in the frame as well.) But that view is pretty brief and uninformative.

Overall, we have to infer François’s attitude from other cues than his expressions, and the results aren’t clear-cut. It seems to me that Garrel’s choices here are typical of one strain of “art cinema.” This storytelling tradition aims to make scenes somewhat indefinite in their meaning and to leave considerable room for spectators to play with various implications of the action.

Cutting and Social Intelligence

Some years ago I developed some ideas about the importance of shot/ reverse shot cutting in an essay called “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision.” (1)

One school of thought in film studies holds that cinematic conventions are wholly arbitrary social constructions. This implies that we have to learn to watch movies, just as we have to learn any arbitrary sign system, like Morse code or written languages. My essay argued that cinema, like painting, offers a continuum of conventions: some require a lot of exposure to learn, while others require much less. The easiest ones rely on regularities of everyday experience. I tried to show that shot/ reverse shot is a fairly easy convention to learn because it mimics the alternation between speaker and listener that we find in the turn-taking of ordinary conversation.

As my examples suggest, even if person A is doing all the talking, we don’t fully understand the scene if we can’t also monitor the reactions of B. By contrast, the shot/ reverse-shot patern keeps a running tab of the dynamics of the conversation. When a director wants to suppress information about B’s response, deleting the reaction shot can create uncertainty or suspense.

Confessions aren’t fictional films; we don’t assume that they use much staging. I’d argue that in videotaped interrogations any uncertainty about the listener’s reactions is quelled by our assumption that the officer is neutral or that any emotion she expresses has no effect on the confession. In other words, during a videotaped confession, any reaction on the part of B is presumed, perhaps wrongly, to be irrelevant. But in watching a fiction film, we tacitly assume that the director has suppressed B’s reaction in order to shape our experience in a particular way. The use of shot/ reverse shot, then, has a narrational function, governing the flow of story information.

We might posit this maxim of social intelligence: We understand an interchange more fully when we can see both participants’ responses to it, moment by moment. This notion underpins our old friend shot/ reverse shot, a convention that requires no specialized learning beyond watching and participating in conversations in real life. The absence of the reverse shot in videotaped confessions forces us to fill in one side of the conversation, and what we fill in may not be warranted.

Lassiter suggests a subtler effect of single-shot confessions. He has specialized in what psychologists call “illusory causation,” as explained in a 2002 press piece.

Criminal interrogations are customarily videotaped with the camera lens zeroed in on the suspect. Psychological research has shown that objects that are the focus of attention, are “more likely than less conspicuous objects to be judged the originators of a physical event, even when there is no objective basis for such a conclusion,” said G. Daniel Lassiter, author of the study. This phenomenon is referred to as “illusory causation.”

So by concentrating wholly on the suspect, the framing attributes a greater causal power to him or her than would a shot/ reverse-shot sequence.

I can’t at the moment see how this might come into play in a fiction film. In both of my major examples here, Bonasera and the baby-feeding friend have less causal power than the character whose response is suppressed. I suspect that the story context of film scenes provides our main sense of who has the causal power, which film style can reiterate or undercut.

Censoring Syndromes

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Syndromes and a Century was one of the best new films I saw last year. It has played at Venice, Vancouver (my quick remarks are here), Hong Kong, and other major festivals. It also won the best editing award at the Asian Film Awards. You can read the Variety review here. Jeff Reichert’s exhilarating appreciation appears, in keeping with the theme of the above entry, at Reverse Shot.

But now Apichatpong has withdrawn the film from theatres because local censors have demanded cuts. The objectionable portions include shots of monks playing with toys and a doctor kissing his girlfriend in a hospital. Details are available at Variety and Limitless Cinema. According to Screen Daily (not available free online):

Apichatpong questions why many other Thai and foreign films which contain excessive violence, nudity, coarse language, crude jokes on other ethnic groups, and monks doing stupid things did not suffer the same fate.

Below I reprint Apichatpong’s most recent statement and information about a petition that’s available online.

Free Thai Cinema Movement Petition

Statement by Apichatpong Weerasethakul with Bioscope, the Thai Film Foundation, Thai Film Director’s

Association, and Alliances.

I am saddened by what has happened to my film. However, this is not the venue to try to make SYNDROMES AND A CENTURY shown in Thai theaters. It is not my intention to use this opportunity to promote my work.

But, it is time to seriously think about what is going on with our censorship laws, so that the next generation of filmmakers will not face the same problems as us, and so that the Thai audiences can truly achieve a freedom of choice.

It is time we discuss whether all films, before being released, should be seen by the Buddhist council, doctors council, teachers council, labor council, the army, pet lovers group, taxi union, representatives from other foreign countries etc? Or, is it easier to turn our nation into a Fascist state so that we can live in harmony and don¹t have to waste time talking about democracy?

The system of the Thai Board of Censors needs to be evaluated. Their members’ relevancy and efficiency needs to be questioned, and we should decide whether the laws should be changed.

I would like to ask you to reflect on the censorship practices in our country and to provide us with advice at

http://www.petitiononline.com/nocut/petition.html

Later on, this Petition will be submitted to the Thai government. Your support will be a great contribution to our fight for one of our most basic rights – that of freedom.

I am grateful for your time and your participation. Thank you very much.

Warmest Regards,

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

KICK THE MACHINE FILMS Co., Ltd.

(1) It’s not available online; it was published in Post-Theory and will be reprinted in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema collection.