Archive for the 'Directors: Sjöström' Category

Time-shifting: THE PHANTOM CARRIAGE on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

Today our comrades at the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck have posted Kristin’s new installment of our series, “Observations on Film Art.” It’s devoted to one of the most complex and intriguing of all silent films, Victor Sjöström’s Phantom Carriage (1921).

Sjöström was one of the greatest directors of the silent cinema. Although many of his films haven’t survived, we’re lucky to have several of his masterpieces, including Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (A Man There Was, 1917), The Girl from Marshy Croft (1917), The Outlaw and His Wife (1918), The Sons of Ingmar (1919), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). He mastered tableau staging in the early 1910s, then quickly learned the nuances of continuity editing, all the while drawing splendid, subtle performances from his actors.

The Phantom Carriage is a sort of horror fantasy. The premise is that the last person to die in a year becomes the escort for the dead of the following year. To this striking idea, taken from a novel by Selma Lagerlöf, the film adds an exceptionally intricate flashback structure.

Silent films made frequent use of flashbacks, usually brief ones to remind the audience of things seen earlier in the film, or longer ones that supplied backstory for the current situation. (In this respect, our films today are rather similar to silent movies.) The Phantom Carriage pushes farther, building its plot out of blocks of flashbacks that are presented out of chronological order, and not all representing memories. It was as daring in its time as The Power and the Glory (1933) and Citizen Kane (1941) were in theirs.

Because of its complexity, The Phantom Carriage long circulated in versions that were cut and rearranged. Once it was restored, we could appreciate just how ambitious a movie it was. Kristin traces the film’s various time schemes and shows that the shifts of chronology and point of view powerfully enrich a story of a man’s hard-won redemption. Her comments are enhanced by some excellent graphics from the keyboard wizards at Criterion.

As ever, we thank our Criterion collaborators: Kim Hendrickson, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, and their team.

A complete listing of our thirteen “Observations” entries is here. For more on Sjöström’s films, see our director tag.

Unveiling Ebertfest 2014

Kristin here:

In the early days of Ebertfest, Roger personally introduced every film at this five-day event, which took place this year from April 23 to 27. He would be onstage for the discussions and question sessions after each screening, often joined by directors, actors, or friends in the industry.

In the summer of 2006, there began the long battle with cancer that Roger fought so determinedly. He withdrew gradually from full participation in the festival that he had founded in his hometown of Champaign-Urbana sixteen years ago. He struggled to immerse himself in the festival, even though repeated surgeries had robbed him of his voice. He introduced fewer films, doing so with his computer’s artificial voice, and when even that became too taxing, he sat in his lounge chair at the back of the Virginia Theater, enjoying the event and occasionally appearing onstage with a cheery thumbs-up. Finally, last year on April 4, less than three weeks before the fifteenth Ebertfest, he passed away. That year’s festival became a celebration of his life.

The celebration continued this year, though on a more upbeat note. Some films were chosen from a list that Roger had left to his wife Chaz and festival organizer Nate Kohn, and they selected others in the same indie spirit. The tradition of showing a silent film with musical accompaniment was maintained. As always, the festival passes sold out, and the crowd, including many long-time regulars, enthusiastically cheered both films and filmmakers.

The tributes

Roger did not live to see the documentary devoted to his life and based on his popular memoir of the same name, Life Itself. It premiered in January at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. He participated in its making, however, encouraging director Steve James (whose 1994 documentary Hoop Dreams Roger had championed) to film him during the final four months of his life. Some of this candid footage reveals the painful and exhausting treatments Roger underwent, but much of it stresses his resilience and the support of Chaz and the rest of his family.

Life Itself was the opening night film. James has done a wonderful job of capturing the spirit of the book and in assembling archival footage and photographs, interspersed with new interviews. The result is anything but maudlin, with a candid treatment of Roger’s early struggles with alcoholism and an amusing summary of Roger’s prickly but affectionate relationship with his TV partner Gene Siskel.

Life Itself was picked up for theatrical distribution by Magnolia Pictures and will receive a summer release, followed by a showing on CNN. (Scott Foundas reviewed the film favorably for Variety, as did Todd McCarthy for The Hollywood Reporter.)

Another tribute followed the next day, when a life-size bronze statue of Roger by sculptor Rick Harney was unveiled outside the Virginia Theater (above). Harney portrays Roger in his most famous pose, sitting in a movie-theater seat and giving a thumbs-up gesture. There is an empty seat on either side of him, so that people can sit beside the statue and have their photos taken. (See the image of Barry C. Allen in the section “Of Paramount importance,” below.)

Far from silent

Roger was a big fan of the Alloy Orchestra, consisting of (L to R above) Terry Donahue, Ken Winokur, and Roger Miller, who specialize in accompanying silent films. They have appeared several times at Ebertfest, playing original music for such films as Metropolis and Underworld. Rather than taking a traditional approach to silent-film music, using piano, organ, or small chamber ensemble, they compose modern scores, played on electronic keyboard combined with their well-known “rack of junk” percussion section, including a variety of found objects, supplemented with musical saw, banjo, accordion, clarinet, and other instruments. The result is surprisingly unified and provides a rousingly appropriate accompaniment to the silents shown at Ebertfest over the years.

I have had the privilege of introducing the film and leading the post-film Q&A on some of these occasions, including for this year’s feature, Victor Seastrom’s 1924 classic, He Who Gets Slapped. (Swedish director Victor Sjöström used the Americanized version during his career in Hollywood.) I put the film in context by pointing out three important historical aspects of the film. First, it was the first film made from script to screen by the newly formed MGM studio, formed in 1924 from the merger of Goldwyn Productions, Metro, and Louis B. Mayer Pictures. (Two earlier releases by MGM were Norma Shearer vehicles which originated at Mayer.) Second, it was probably the film that cemented Lon Chaney’s stardom, after his breakthrough role as Quasimodo in the 1922 Hunchback of Notre Dame. Starting in 1912, Chaney had been in well over 100 films before Hunchback, many of them shorts and nearly all of them supporting roles. Third, He Who Gets Slapped was Seastrom’s second American film after Name the Man in 1923, and a distinct improvement on that first effort.

Naturally MGM wanted a big, prestigious hit for its first production, and He Who Gets Slapped came through, being both a critical and popular success–and also boosted Norma Shearer to major stardom. Seastrom and Chaney both stayed on at MGM, though the former returned to European filmmaking after the coming of sound and Chaney died in 1930.

I was joined for the post-film discussion by Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune, and we talked with Donahue and Winokur while Miller sold the group’s CDs and DVDs in the festival shop. They revealed that this new score had been commissioned by the Telluride Film Festival and that it was a project that appealed to their taste for off-beat films. There were many questions from the audience, and we suspect that the Alloy Orchestra will continue to be a regular feature of the festival.

A cornerstone of indie cinema

Although Roger was occasionally criticized for supposedly lowering the tone of film reviewing by participating in a television series, he and partner Gene Siskel regularly tried to promote indie and foreign films that didn’t get wide attention. Roger did the same in his written reviews, and Ebertfest was originally known as the “Overlooked Film Festival.” Inevitably it was shortened by many attendees to “Ebertfest,” and eventually that name became official. It reflects the wider range of films that came to be included, with the silent-film screening and frequent showings of 70mm prints of films like My Fair Lady that were hardly overlooked.

Among Roger’s friends was Michael Barker, co-founder and co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, one of the most important of the small number of American companies still specializing in independent and foreign releases. A long-time Ebertfest regular, Barker usually brings a current or recent release to show, along with filmmakers or actors. This year he was doubly generous, bringing Capote (2005, above), to which Roger had given a four-star review, and the current release Wadjda (2012).

Roger never reviewed the latter, but it is certainly the sort of film that he loved: a glimpse into a little-known culture by a first-time filmmaker with a progressive viewpoint. Wadjda is remarkable as the first feature film made in Saudi Arabia, where there are no movie theaters. Moreover, it was made by a woman, Haifaa Al-Monsour, and tells the story of a little girl who defies tradition by aspiring to buy and ride a bicycle in a country where this, like women driving cars, was illegal. (Below, Wadjda learns to ride a bicycle on a rooftop, hidden from public view.)

Both the film and Al-Monsour thoroughly charmed the audience. Barker interviewed her afterward, and she revealed that, not surprisingly, the making of the film was touched by the same sort of repression that it portrays. Women are not allowed to work alongside men in Saudi Arabia, so Al-Monsour had to hide in a van while shooting on location. Given that there is no cinema infrastructure in the country, the film was a Saudi Arabian-German co-production, with Arabic and German names mingling in the credits. We also learned that it has since become legal for Saudi girls to ride bicycles. Perhaps someday filmmaking will become more common there, and male and female crew members can work openly together.

Naturally Wadjda was made with a digital camera, since this new technology is crucial to the spread of filmmaking in places like the Middle East where there is little money or equipment for production. In contrast, Capote was shown in a beautiful widescreen 35mm print that looked great spread across the entire width of the Virginia’s huge screen. Naturally the screening became a tribute to the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, giving his only Oscar-winning performance (out of four nominations) in the lead role.

Barker had brought with him a surprise guest, Capote‘s director, Bennett Miller, whose appearance had not been announced in advance. He discussed how he and scriptwriter Dan Futterman learned that there was a second, rival Capote film in the works, Infamous (2006), which also dealt with the period when the author was researching In Cold Blood. Miller and Futterman decided to press ahead, a wise move in that their film drew more attention than did Infamous. Much of the discussion was devoted to Hoffman’s performance and his acting style in general.

Capote was Miller’s first fiction feature. He had come to public attention with his documentary The Cruise (1998), which Roger had given a brief three-star review. Roger continued his support for Miller with a four-star review for Moneyball (2011). It’s a pity he did not live to see Miller’s latest, Foxcatcher, which will be playing in competition at Cannes in May.

Overlooked no longer

Perhaps no young filmmaker better demonstrates the impact that Roger’s support can have on a career than Ramin Bahrani. Roger saw his first feature, Man Push Cart, at Sundance in 2006 and invited it and the filmmaker to the  “Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

“Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

His second film, Chop Shop, brought him to Ebertfest a second time, in 2009. (Roger’s program notes are here, and his four-star review here.) At about that time, Bahrani’s third film, Goodbye Solo, was released. Given its modest budget, it did reasonably well at the box office, grossing nearly a million dollars worldwide (in contrast to Man Push Cart‘s roughly $56 thousand). Bahrani inched toward mainstream filmmaking with At Any Price (2012), starring Dennis Quaid and Zac Efron, and he is currently in post-production on 99 Homes, with Andrew Garfield, Michael Shannon, and Laura Dern. During the onstage discussion, he spoke of struggling to maintain a balance between the indie spirit of his earlier films and the more popularly oriented films he has recently made.

Bahrani visited Ebertfest for a third time this year, belatedly showing Goodbye Solo. We had enjoyed this film when it came out, and it holds up very well on a second viewing. It’s a simple story of opposites coming together by chance. An irrepressibly talkative, friendly immigrant cab driver, Solo (a nickname for Souléymane), becomes concerned when a dour elderly man engages him for a one-way trip to a regional park whose main feature is a windy cliff. He fears that William is planning suicide. Solo arranges to drive William whenever he calls for a cab and even becomes his roommate in a cheap hotel. Gradually, with the help of his young stepdaughter Alex, he seems to draw William out of his defensive shell.

As in Bahrani’s earlier films the main character is an immigrant and played by one, using his own first name (Souléymane Sy Savané). He’s the main character in that we are with him almost constantly, seeing William only as he does. William is a vital counterpart to him, however. He is perfectly embodied by Red West, an actor who worked for Elvis Presley and did stunt work and bit parts in films and television since the late 1950s. He may look vaguely familiar to some viewers, but he’s not really recognizable as a star and comes across convincingly as an aging man buffeted by life’s misfortunes.

Most of the film takes place in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Bahrani’s hometown, with many moody, atmospheric shots of the cityscape at night. One crucial scene involves a drive into the woods and mountains, however, and much of it is filmed in a dense fog. One questioner from the audience asked if Bahrani had planned to shoot in such weather or if, given his short shooting schedule, the fog turned out to be a hindrance to him. He responded that he had dreamed of being able to shoot in fog and that the weather cooperated on the three days planned for that locale. In fact, he re-shot some images as the fog became denser, to keep the scene fairly consistent.

Bahrani’s presence at Ebertfest spans half its existence, from 2006 to 2014. As the festival becomes more diverse in its offerings, it is good to have him back as a reminder of the Ebertfest’s early emphasis on the “overlooked.”

Of Paramount importance

Logo for National Telefilm Associates, TV syndication arm of Republic Pictures.

DB here:

Among the guests at this year’s E-fest was Barry C. Allen. For over a decade Barry was Executive Director of Film Preservation and Archival Resources for Paramount. That meant that he had to find, protect, and preserve the film and television assets of the company—including not just the Paramount-labeled product but libraries that Paramount acquired. Most notable among the latter was the Republic Pictures collection.

We may think of Republic as primarily a B studio, but it produced several significant films in the 1940s and 1950s—The Red Pony, The Great Flammarion, Macbeth, Moonrise, and Johnny Guitar. John Wayne became the most famous Republic star in films like Dark Command, Angel and the Badman, and Sands of Iwo Jima. John Ford’s The Quiet Man was Wayne’s last for the studio, which folded in 1959. Next time you see one of the gorgeous prints or digital copies of that classic, thank Barry for his deep background work that underlies the ongoing work of his dedicated colleagues.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Hard as it may seem for young people today to believe, in the 1950s TV stations routinely cut the films they showed. Packages of 16mm prints circulated to local stations, and these showings were sponsored by local businesses. Commercials had to be inserted (usually eight per show), and the films had to be fitted to specific lengths.

WISH-TV ran three movies a day, and two of those would be trimmed to 90-minute air slots. That meant reducing the film, regardless of length, to 67-68 minutes. Barry’s job was to look for scenes to omit—usually the opening portions—and smoothly remove them. Fortunately for purists, the late movie, running at 11:30, was usually shown uncut, and then the station would sign off.

By coincidence I recently saw a TV print of Union Depot (Warners, 1932) that had several minutes of the opening exposition lopped off. We who have Turner Classic Movies don’t realize how lucky we are. Fortunately for film collectors, some stations, like Barry’s, retained the trims and put them back into the prints.

While working at WISH-TV, Barry began booking films part-time. He programmed some art cinemas in the Indianapolis area during the early 1970s, mixing classic fare (Marx Brothers), current cult movies (Night of the Living Dead), and arthouse releases like Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie—a bigger hit than anyone had anticipated. He also helped arrange a visit of Gloria Swanson with Queen Kelly; she carried the nitrate reels in her baggage.

At the same time, Barry was learning the new world of video editing, with ¾” tape and telecine. Because of his experience in television, Barry was contacted by Paramount to become Director of Domestic Syndication Operations. His chief duty was to deliver films to TV stations via tape, satellite, and prints. From that position, he moved to the preservation role he held until 2010, when he retired.

Barry is a true film fan. He has reread Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By many times and retains his love for classic cinema. The film that converted him to foreign-language cinema was, as for many of his generation, Children of Paradise, but he retains a fondness for Juliet of the Spirits, The Lady Killers, and other mainstays of the arthouse circuit of his (and my) day. He’s proudest of his work preserving John Wayne’s pre-Stagecoach films.

It was a great pleasure to hang out with Barry at Ebertfest. Talking with him reminded me that The Industry has long housed many sophisticated intellectuals and cinephiles. Not every suit is a crass bureaucrat.

Young-ish adult

Patton Oswalt had planned to come to Ebertfest in an earlier year, to accompany Big Fan and to show Kind Hearts and Coronets to an undergrad audience. He had to withdraw, but he showed up this year. On Wednesday night he screened The Taking of Pelham 123 to an enthusiastic campus crowd, and the following night, after getting his Golden Thumb, he talked about Young Adult. (Roger’s review is here.)

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

It’s common for viewers to notice that Mavis Gary, the malevolent, disturbed main character of Young Adult, doesn’t change or learn. “Anti-arc and anti-growth,” Oswalt called the movie. I found the film intriguing because structurally, it seems to be that rare romantic comedy centered on the antagonist.

Mavis returns to her home town to seduce her old boyfriend, who’s now a happy husband and father. A more conventional plot would be organized around Buddy and his family. In that version we’d share their perspective on the action and we’d see Mavis as a disruptive force menacing their happiness.

What screenwriter Diablo Cody has done, I think, is built the film around what most plots would consider the villain. So it’s not surprising that there’s no change; villains often persist in their wickedness to the point of death. Attaching our viewpoint to the traditional antagonist not only creates new comic possibilities, mostly based on Mavis’s growing desperation and her obliviousness to her social gaffes. The movie comes off as more sour and outrageous than it would if Buddy and Beth had been the center of the plot.

Making us side with the villain also allows Oswalt, as Matt Freehauf, to play a more active role as Mavis’s counselor. In a more traditional film, he’d probably be rewritten to be a friend of Buddy’s. Here he’s the wisecracking voice of sanity, reminding Mavis of her selfishness while still being enough in thrall to high-school values to find her fascinating. As in Shakespearean comedy, though, the spoiler is expelled from the green world that she threatens. It’s just that here, we go in and out of it with her and see that her illusions remain intact. Maybe we also share her sense that the good people can be fairly boring.

All you can eat

There aren’t any villains in Ann Hui’s A Simple Life, a film we first saw in Vancouver back in 2011. Roger had hoped to bring it last year, but Ann couldn’t come, as she was working on her upcoming release, The Golden Era. This year she was free to accompany the film that had a special meaning for Roger at that point in his life.

The quietness of the film is exemplary. It’s an effort to make a drama out of everyday happenings—people working, eating, sharing a home, getting sick, worrying about money, helping friends, and all the other stuff that fills most of our time. The two central characters are, as Roger’s review puts it, “two inward people” who are simple and decent. Yet Ann’s script and direction, and the playing of Deanie Yip Tak-han and Andy Lau Tak-wah, give us a full-length portrait of a relationship in which each depends on the other.

Roger Leung takes Ah-Tao, his amah, or all-purpose servant, pretty much for granted. She feeds him, watches out for his health, cleans the apartment, even packs for his business trips. When he’s not loping to and from his film shoot, he’s impassively chowing down her cooking and staring at the TV. A sudden stroke incapacitates her, and now comes the first surprise. A conventional plot would show her resisting being sent to a nursing home, but she insists on going. Having worked for Roger’s family for sixty years, Ah-Tao can’t accept being waited upon in the apartment. So she moves to a home, where most of the film takes place.

A Simple Life resists the chance to play up dramas in the facility. Thanks to a mixture of amateur actors and non-actors, the film has a documentary quality. It captures in a matter-of-fact way the grim side of the place—slack jaws, staring eyes, pervasive smells. (A small touch: Ah-Tao stuffs tissue into her nostrils when she heads to the toilet.) Mostly, however, we get a sense of the facility’s everyday routines as the seasons change. The dramas are minuscule. Occasionally the old folks snap at one another, and one visitor gets testy with her mother-in-law. One woman dies (in a bit of cinematic trickery, Ann suggests that it’s Ah-Tao), and an old man who keeps borrowing money is revealed to have a bit of a secret. It’s suggested that a pleasant young woman working at the care facility will become Roger’s new amah, but that seems not to happen. The prospect of a romance with her is evoked only to be dispelled.

Ah-Tao’s health crisis has made Roger more self-reliant, but his life has become much emptier. He seems to realize this in a late scene, when he stands in the hospital deciding how to handle Ah-Tao’s final illness. Throughout the film, food has been a multifaceted image of caring, community, friendship, childhood (Roger’s friends recall Ah-Tao cooking for them), and even the afterlife. Ah-Tao and Roger rewrite the Ecclesiastes line about what’s proper to every season by filling in favorite dishes. As he mulls over Ah-Tao’s fate, Roger is, of course, eating. But it’s cheap takeaway noodles and soda pop. This silent scene measures his, and her, loss better than any dialogue could.

The art of American agitprop

Matt Zoller Seitz and Oliver Stone on stage at the Virginia Theatre.

A Simple Life is a very quiet film. Ebertfest’s highest-profile visitors brought along two of the noisiest movies of 1989. It’s the twenty-fifth anniversary of Do The Right Thing (Roger’s review) and Born on the Fourth of July (Roger’s review), and seen in successive nights they seemed to me to put the “agitation” into agitprop.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

The ending has become the most controversial part of the film. It’s here that Lee was, I think, especially forceful. The crowd in the street is aghast at the killing of Radio Raheem by a ferocious cop, but what really triggers the riot is Mookie’s act of smashing the pizzeria window. I’ve always taken this as Mookie finally choosing sides. He has sat the fence throughout–befriending one of Sal’s sons and quarreling with the other, supporting Sal in some moments but ragging him in others. Now he focuses the issue: Are property rights (Sal’s sovereignty over his business) more important than human life? Moreover, in a crisis, Mookie must ally himself with the people he lives with, not the Italian-Americans who drive in every day. It’s a courageous scene because it risks making viewers, especially white viewers, turn against that charming character, but I can’t imagine the action concluding any other way. Lee had to move the project to Universal from Paramount, where the suits wanted Mookie and Sal to hug at the end.

Staking so much on social allegory, the film sacrifices characterization. Characters tend to stand for social roles and attitudes rather than stand on their own as individuals. The actors’ performances, especially their line readings, keep the roles fresh, though, and the film still looks magnificent. I was struck this time by the extravagance of its visual style. In almost every scene Lee tweaks things pictorially through angles, color saturation, slow-motion, short and long lenses, and the like–extravagant noodlings that may be the filmic equivalent of street graffiti.

By the end, in order to underscore the confrontation of Radio Raheem and Sal, Lee and DP Ernest Dickerson go all out with clashing, steeply canted wide-angle shots. (We’ve seen a few before, but not so many together and usually not so close.) Having dialed things up pretty far, the movie has to go to 10.

In Born on the Fourth of July, Stone more or less starts at 11 and dials up from there. Beginning with boys playing soldier and shifting to an Independence Day parade that for scale and pomp would do justice to V-J Day, the movie announces itself as larger than life. The storyline is pretty straightforward, much simpler than that of Do The Right Thing. A keen young patriot fired up with JFK’s anti-Communist fervor plunges into the savage inferno of Viet Nam. Coming back haunted and paralyzed, Ron Kovic is still a fervent America-firster until he sees college kids pounded by cops during a demonstration. This sets him thinking, and eventually, after finding no solace in the fleshpots of Mexico, he returns to join the anti-war movement.

Even more than Lee, Stone sacrifices characterization and plot density to a larger message. The Kovic character arc suits Cruise, who built his early career on playing overconfident striplings who get whacked by reality. But again characterization is played down in favor of symbolic typicality. While there’s a suggestion that Ron Kovic joins the Marines partly to prove his manhood after losing a crucial wrestling match, the plot also insists that his hectoring mother and community pressure force him to live up to the model of patriotic young America. He becomes an emblem of every young man who went to prove his loyalty to Mom and apple pie.

Likewise, Ron’s almost-girlfriend in high school becomes a college activist and so their reunion–and her indifference to his concern for her–is subsumed to a larger political point. (The hippies forget the vets.) We learn almost nothing about the friend who also goes into service; when they reunite back home, their exchanges consist mostly of more reflections on the awfulness of the war. Later Cruise is betrayed, almost casually, by an activist who turns out to be a narc. But this man is scarcely identified, let alone given motives: he’s there to remind us that the cops planted moles among the movement.

What fills in for characterization is spectacle. I don’t mean vast action; Stone explained that he had quite a limited budget, and crowds were at a premium. Instead, what’s showcased, as in Do The Right Thing, is a dazzling cinematic technique.

Visiting the UW-Madison campus just before coming to Urbana for Ebertfest, Stone offered some filmmaking advice: “Tell it fast, tell it excitingly.” The excitement here comes from slamming whip pans, thunderous sound, various degrees of slow-motion, silhouettes, jerky cuts, Steadicam trailing, handheld shots, all jammed into the wide, wide frame. Every crack is filled with icons and noises–flags, whirring choppers, kids with toy guns, prancing blondes, commentative music. “Soldier Boy” plays on the supermarket Muzak when Ron is telling Donna about his plans.

By the time Ron visits the family of the comrade he accidentally killed, Stone finds another method of visual italicization: the split-focus diopter that creates slightly surreal depth.

Since so many scenes have consisted of a flurry of intensified techniques, simple over-the-shoulder reverse shots might let the excitement level drop. So a new optical device aims to deliver fresh impact in one of the film’s quietest moments.

Like Lee, Stone took the Virginia Theatre audience behind the scenes. He agreed with William Friedkin, who was originally slated to do the film: “This is as close as you’ll every come to Frank Capra.” Instead of using the shuffled time scheme of Kovic’s autobiography, Friedkin advised that “This is good corn. Write it straight through.” Hence the film breaks into distinct chapters, each about half an hour long and sometimes tagged with dates. They operate as blocks measuring phases of Ron’s conversion. Like many filmmakers of his period, Stone deliberately made each chapter pictorially distinct–the low-contrast Life-magazine colors of the opening parade versus the lava-like orange of the beachfront battle.

Stone pointed out that this film marked the beginning of his career as a figure of public controversy. Like Lee, he was attacked from many sides, and from then on he was a lightning rod. Matt Zoller Seitz (who’s preparing a book on Stone) pointed out that at the period, he was astonishingly prolific. From 1986 (Salvador, Platoon) to 1999 (Any Given Sunday), he directed twelve features, about one a year.

Lee was hyperactive as well over the same years, releasing fourteen films. And neither has stopped. Lee’s new film is the Kickstarter-funded Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, while Stone is touring to support the DVD release of his 2012 documentary series, The Untold History of the United States. Both men like to work, and more important, they’re driven by their ideas as well as their feelings. By seeking new ways to agitate us, they impart an inflammatory energy to everything they try. And in giving them a chance to share their insights and intelligence with audiences outside the Cannes-Berlin-Venice circuit, Ebertfest once again demonstrates its uniqueness. Roger would be proud.

The introductions and Q&A sessions for most of the films, as well as the morning panel discussions, have been posted on Ebertfest’s YouTube page. Program notes for each film are online; see this schedule and click on the title.

For historical background on Barry Allen’s work as an editor of syndicated TV prints, see Eric Hoyt’s new book Hollywood Vault: Film Libraries Before Home Video.

P. S. 1 May 2014: Thanks to Ramin S. Khanjani for pointing out that Ramin Bahrani had worked on other films before Man Push Cart. These included one feature he made in Iran, Biganegan (Strangers, 2000); it got only limited play in festivals and apparently a few theaters. I can’t find information about the others online, and presumably they were shorts and/or did not receive distribution. (K.T.)

Ann Hui, with Kristin, gets into the spirit of Ebertfest. David is represented in absentia by the Dots.

The ten best films of … 1921

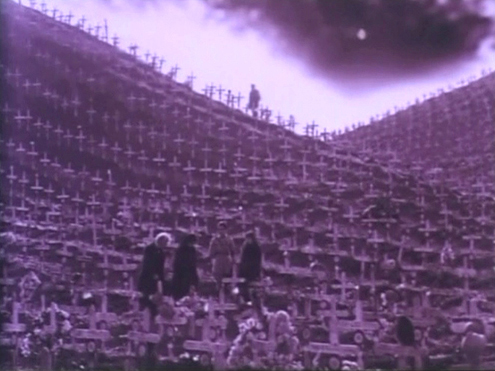

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Kristin here:

To end the year, we’re continuing our tradition of picking the ten best films not of the current year but of ninety years ago. Our purpose is twofold. We want to provide guidance for those who may not be particularly familiar with silent cinema but who want to do a bit of exploring. We also want to throw in occasional unfamiliar films to shake up the canon of classics a bit.

Like last year, it was strangely difficult to come up with ten equally great films. There were some obvious choices, but beyond them there were a lot of slightly less wonderful items jostling for the other places on the list. The problem had several causes. Some master directors who routinely figure in our year-end ten choices had off-years. In 1921 D. W. Griffith released only one film, Dream Street, a notably weak item. (What I have to say about it can be found on pp. 108-113 of the British Film Institute’s The Griffith Project, Vol. 10.) Ernst Lubitsch released two films that seem like less interesting attempts to repeat earlier successes: Anna Boleyn (a pale imitation of Madame Dubarry) and Die Bergkatze (nice, and I was tempted to include it, but it’s less amusing than the Ossi Oswalda comedies, here and here). Cecil B. DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol is not nearly as well structured as his earlier sophisticated rom-coms.

In other cases, films simply don’t survive. John Ford released seven films in 1921, all of which are lost.

Death comes calling, twice

Probably the easiest decision was to include The Phantom Carriage (also known as The Phantom Chariot), by Victor Sjöström. As I noted recently, the Criterion Collection has recently issued a beautiful restoration of it (DVD and Blu-ray).

When I first saw The Phantom Carriage, I was probably still an undergraduate. Given its reputation as a great classic, I was somewhat disappointed. No doubt it was partly the battered 16mm copy I watched, but the film is a bit formidable for someone not accustomed to the aesthetic of silent cinema–and especially of the great Swedish directors of the era. Its protagonist, played by Sjöström himself, is a thoroughly, determinedly unlikeable fellow, and the complex flashback structure can be a bit disconcerting on first viewing. But the effort to watch until one “gets” Sjöström is well worth it, since he’s undoubtedly one of the half dozen greatest silent directors.

The story opens on New Year’s Eve with Edit, a young Salvation Army volunteer, on her deathbed. She unexpectedly begs her colleague and mother to fetch the town drunk, David Holm, to her bedside. At the same time, Holm sits drinking in a graveyard as midnight approache. He tells two fellow inebriates the legend of the phantom carriage, the vehicle that picks up the souls of the  newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

It’s a deeply affecting story, wonderfully acted and staged. In most scenes the lighting and staging are impeccable, and the famous superimpositions that portray the carriage and the dead are highly ambitious for the period and impressively executed. The filmmakers have managed to make the carriage, superimposed on real landscapes, appear to pass behind rocks and other large objects. In short, a film that has everything going for it.

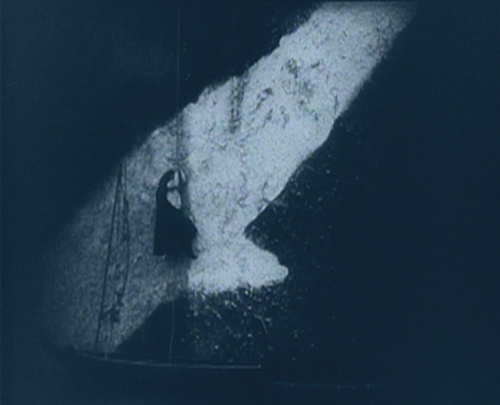

Death himself appears in Der müde Tod (literally “The Tired Death,” often called Destiny, or occasionally in the old days, The Three Candles). Here the great German director Fritz Lang hits his stride, and you can expect him to figure on most of our lists from now on.

In Destiny (available on DVD from Image Entertainment) a young woman’s fiancé is killed early on. Death, a sympathetic figure who regrets what he must do, gives her three chances to find another person whose demise can substitute for her lover’s. The three episodes in which she tries take place in Arabian-Nights Baghdad, Renaissance Venice, and ancient China; each story casts her as the heroine and her lover as the hero.Things don’t go well, and Death actually gives her a fourth chance when she returns to the present.

This was Lang’s first venture into the young German Expressionist movement, which had been launched the year before with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. The style shows up only intermittently, perhaps most dramatically in the Venetian episode when the lover shinnies up a rope along a wall painted with a gigantic splash of light. (See bottom.)

Each film has a “happy ending.” I leave it to you to determine which is grimmer.

I’m turning over the keyboard to David now, to describe a film he knows better than I do.

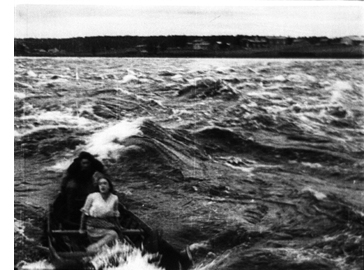

More Northern European drama

Mauritz Stiller alternated urban comedies (Thomas Graal’s Best Film, 1917; Thomas Graal’s Best Child, 1918; Erotikon, 1920) with more lyrical dramas and romances set in the countryside (Song of the Red Flower, 1919; Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919). Johan (1921) is in the pastoral vein. Its integration of landscape into the drama suggests it was an effort to recapture the production values that overseas critics had praised in Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917) and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Like the Sjöström films, however, Johan offers more than splendid spectacle; it’s the study of the undercurrents of a marriage.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

We’re introduced to the couple by following the rogue Vallavan’s entry into the town; Johan seems almost a secondary character until Vallavan leaves. When Johan breaks his leg, Merit agrees to be his wife. Now we’re attached to her standoint and see her life of drudgery under the petty tyranny of Johan’s mother. Vallavan returns, and Merit falls under his spell. Taking her hand, he says, “I want to rescue you.” After she has fled with him, Johan clumsily wanders the rocky shore. “Will I ever see Merit again in this life?” The narrational weight passes to him as he decides to pursue the runaways.

Like Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919), Johan presents marriage as a trap for unwary women. Our shifting attachment, from Vallavan to Merit and eventually to Johan, allows us to see the situation in many dimensions. As a sort of parallel, Stiller makes fluid use of the now solidly-established conventions of continuity editing. Vallavan’s seduction of Merit is played out in tense shot/ reverse-shot, and there’s an engrossing moment involving delicate shifts in point of view. When the bedridden Johan sees Merit leaving, after his mother has cast her out of the house, he must smash a window pane with his elbow in order to call to her. Stiller’s dynamic eyelines, direction of movement, and precise changes of camera setup here show that he had mastered the American style.

Alongside this finesse, there is still plenty of outdoor action, highlighted when Vallavan rows Merit away in the tumultuous river. Filmed from another boat, the actors are all but engulfed by the waves. It was presumably scenes like this that the parent company, Svensk Filmindustri, hoped would attract international attention. At this period Svensk, dominant in the local industry, was hoping to sell its films on a global scale. That ambitious plan failed, but it left us with many outstanding movies and soon brought Stiller, along with Sjöström, to Hollywood.

Johan is available on a Region 2 PAL DVD, coupled with Kaurismaki’s Juha, another adaptation of the Juhani Aho story.

The joys of small-town life

Last year I included two films by William C. deMille, the considerably less famous brother of Cecil B. The year 1921 saw the release of what is today his best-known film, Miss Lulu Bett. It was based  on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

The return of the husband’s globetrotting younger brother Ninian after a twenty-year absence injects some life into the situation. Taking the family out to dinner, he realizes just how boring the family is (right), and to liven things up, suggests that he and Lulu perform mock marriage vows. Dwight realizes that the ceremony is legally binding, and, already attracted to Lulu, Ninian suggests that they treat it as a real marriage. Desperate to escape her dreary situation, Lulu agrees. The relationship proves agreeable, and Lulu declares that she will learn to love Ninian–when he reveals that he had previously been married, though he doesn’t know whether his first wife is dead (in which case he and Lulu are married) or alive (in which case they aren’t). Unwilling to take a chance, Lulu returns to the Deacons, who consider her disgraced and treat her even worse.

The film avoids melodrama. Ninian is not a villain; he’s kind to Lulu and sorry for the position he’s placed her in. It remains to Lulu to summon the gumption to leave the family and find her own happiness.The whole thing is told with restraint and little touches of humor that draw the viewer into a deep sympathy with Lulu’s plight.

Lois Wilson’s performance as Lulu is crucial in this. She is at once plain enough that we can believe she is in danger of becoming an old maid and pretty enough to plausibly attract the attention of the handsome local schoolteacher. Wilson’s most prominent role came two years later, when she starred as the heroine in James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon.

Miss Lulu Bett is the only one of William’s films available on DVD, paired with Cecil’s Why Change Your Wife? As so often happened, William seems to take a back seat to his famous brother, but the pairing is a logical one, in that William wrote the script for Why Change Your Wife?

Another small-town drama of the same year is Lois Weber’s The Blot. In 1981, when I was teaching a course on American silent film at the University of Iowa, I wanted to quickly demonstrate to the students that the silent period was not an era of exaggerated acting and naively melodramatic plots. I showed a double feature of The Blot and King Vidor’s Wine of Youth (1924). The latter portrays changing sexual mores through the story of three generations of the same family, with a young woman of the Roaring Twenties questions the necessity of marriage when she discovers that her mother is contemplating divorce. I think Wine of Youth (unfortunately not available on video) and The Blot convinced my class that silent films could be both sophisticated and subtly acted.

The “blot” of Weber’s title refers to the notion that people in professions depending on intelligence and education are poorly paid, while tradespeople and children from rich families are well off. The representatives of the underpaid are a college teacher, Prof. Griggs, and a young, idealistic minister. The parallels to recent events are striking. College professors may not be so badly paid as in the 1920s, but the move toward institutions of higher learning depending on adjunct lecturers has created a similar issue. In general, the income gap is familiar: the rich young wastrels taking Prof. Griggs’s course represent what we now call the one percent, while the professor and minister live on a much lower plane.

Weber’s drama is not quite this bald, however. Various levels of prosperity are represented. The professor’s family lives in shabby gentility, his wife grimly struggling to keep food on the table and his daughter Amelia, in delicate health due to a lack of nourishing food, working in the local library. Their neighbors are the family of a successful shoemaker, who live well but lack education. The shoemaker’s wife in particular resents what she perceives as intellectual snobbishness in the professor’s family and takes every opportunity she can to flaunt her comparative wealth.

Her son, however, has a crush on Amelia, as does the poor minister. Into this situation comes Phil West, the professor’s rich but indolent and mischievous student. Also attracted to Amelia, Phil for the first time encounters real poverty and is  shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

The plot is remarkably dense and unpredictable. Every scene involves glances that lead to new knowledge or serious misunderstanding, deflecting the plot into new directions. Early on it is impossible to say which of the three young men Amelia will end up with, and even by the late scenes, when only two plausible romantic candidates remain, we have no idea which she will pick. As in many of Weber’s films, she does a bit of preaching about the social problem involved, but in The Blot she leaves this until near the end and gets it over quickly and fairly believably. The considerable but gradual change in Phil’s attitude toward education and the problems of poverty is also made believable. The prosperous neighbor’s change of attitude may seem a bit sudden, though it is somewhat motivated by a line early on.

But on the whole, even more than with Miss Lulu Bett, this is an absorbing story with characters for whom we care. Weber uses motifs as skillfully as any director in the early phase of the classical Hollywood cinema. Watch in particular how many different ways she uses the Griggs family’s cat and her two kittens: to demonstrate the family’s poverty, to be the main means of the neighbor lady’s spite, to introduce some comedy, and so on. Even more pervasive is the way that shoes become tokens of characters’ various social positions.

The Blot is available on DVD from Image. Those interested in Weber as a director should note that next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna plans a retrospective of her work.

Which is best? Damfino.

In past year-end lists, we’ve watched Harold Lloyd, Charles Chaplin, and Buster Keaton creeping toward their great features of the 1920s. This year two of them move cautiously into longer films, and the other releases two more terrific one-reelers.

The Boat is one of Keaton’s most admired shorts. In it, he, his wife, and their two young sons build a boat, the Damfino, and unwisely launch it on the open ocean. Everything that can go wrong does: the life-preserver sinks, the anchor floats, and naturally a storm hits. The wife’s pancakes aren’t edible, but one temporarily patches a leak. Throughout the intrepid band carries on against all obstacles.

Less perfect but more dazzling and (perhaps) funnier is The Playhouse. The premise of a small variety theater creates an episodic, messy narrative, but it allows Keaton to play out a series of four “acts.” Initially we see Keaton buy a ticket and enter an auditorium where the audience, the orchestra, and all the performers are played by “Buster Keaton.” As one of the audience members remarks, “This fellow Keaton seems to be the whole show,” which is true in more way than one. The multiple images of Keaton were accomplished entirely in the camera, by cranking back the film with precise timing and uncovering a different part of the lens at each pass. The precision when one Keaton figure talks to or dances with another is amazing.

This all turns out to be a stagehand’s dream. (Keaton being the stagehand.) The multiplication motif returns as an act involving two pretty girls who happen to be twins–something Buster  doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

The Boat is included on Kino’s disc of The Navigator and The Playhouse with their out-of-print DVD of The General. Still in print, however, is Kino’s eleven-disc set of the features and shorts. For those in the UK and other region-2 countries, Eureka! has a “Masters of Cinema” three-disc set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films 1917-1923,” which includes many of his earlier films with Fatty Arbuckle.

The year saw Lloyd and Chaplin make their first feature films, though both releases were still fairly short. I’m not really counting A Sailor-Made Man as one of the top ten of the year, since it’s a delightful but decidedly light item. Just another reminder that Lloyd is inching toward greatness.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

The shipboard scenes allow Harold to get in some funny bits, mainly involving him trying to be tough and succeeding at first by sheer accident. Later, however, he is inspired by the heroine’s danger to become a real rescuer. It’s a sign of bigger things to come.

New Line’s Harold Lloyd boxed set is out of print, but you can still get the volumes separately. A Sailor-Made Man is in Volume 3, along with such delights as Hot Water and For Heaven’s Sake.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

In the meantime, the mother has become a rich singer, and coincidentally she comes to the slums doing charitable work. The authorities eventually try to remove the Kid to an orphanage, and later a flop-house proprietor turns him in to receive a reward. Still, Chaplin doesn’t milk the pathos, and a happy ending duly arrives.

The Kid is available in a decent print along with A Day’s Pleasure and Sunnyside on the “Charlie Chaplin Special” DVD. Our recording off Turner Classic Movies strikes me as being slightly better quality, so you might keep an open to see if they reshow it. It was also announced this week that The Kid has been added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.

Fuzzy movies, big and small

Soft-style cinematography had been tried in some films of the late 1910s, most notably in Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. But in the 1920s it spread. In Hollywood, it was mainly a technique for making beautiful images and especially for creating glamorous close-ups of actresses. In France, it was a way of tracking a character’s inner life.

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 novel, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was a huge bestseller, and the first film adaptation in 1921, directed by Rex Ingram, was equally successful. To many, it is remembered for having made a super-star of its main actor, Rudolph Valentino. Anyone who has seen him as the caricatured Latin Lover of his later films will be pleasantly surprised to discover that the man could act, as could his leading lady, the lovely Alice Terry.

Ingram was the quintessential middlebrow director of the 1920s, doing big-budget, respectable adaptations of popular literature (e.g., Scaramouche, The Prisoner of Zenda). To me, Four Horsemen escapes the stodginess of the later films, at least to some extent (as does his other 1921 film, The Conquering Power). It and the other film in this section were borderline cases, chosen as much for their historical importance as their quality, perhaps, but definitely worth watching.

One of Four Horsemen‘s greatest strengths is its photography. Ingram worked consistently with one of the greatest cinematographers of the 1920s, John F. Seitz, who created glowing images of  sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

Four Horsemen was also an early entry in the anti-World War I genre of the 1920s and 1930s. Its final scene in a vast military cemetery of identical white crosses remains a powerful one. (See above.) Here, however, the Germans are still stereotypes, militaristic puppets with no redeeming features. Even that notion would gradually change, however, until nine years later All Quiet on the Western Front could recount the war from the German point of view.

Four Horsemen is available on DVD on demand from Amazon, supplied on DVD-R. In the same format, one can order it on a set with a documentary on Valentino. The reviews of the latter suggest that the visual quality is good.

(For more on this photographic style, see my “The soft style of cinematography,” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, pp. 287-293.)

I’m not a huge fan of Marcel L’Herbier, and I’m not entirely sure that El Dorado is a full-fledged  masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

In a way this is a somewhat silly, literal notion, and yet it’s exciting to see filmmakers exploring new devices relatively early in film history. Gauzy filters, distorting mirrors, slow-motion superimpositions, rhythmic cutting, and subjective moving camera were soon to be in common use by a small group of French directors. El Dorado was also the first film to be filmed within the Alhambra, which lends it considerable visual interest.

If we’re still writing this blog in 2019, our list will probably include the culminating film of the movement, and arguably L’Herbier’s best silent film, L’Argent.

Not many French Impressionist films are available in the U.S. If you have a multi-region player, El Dorado is paired with L’Herbier’s earlier L’homme du large (1920) on a French DVD.

Tigers and lepers and a mysterious yogi

We tend to think of serials as having many episodes and being low-budget additions to programs. That’s the American model, but in Europe things were different. Louis Feuillade’s serials are among the gems of the 1910s. In Germany, serials tended to have fewer episodes but bigger budgets–much bigger. Many were only two parts, most famously Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (coming next year to our top-ten list) and Die Nibelungen (coming in 2014). Lang had launched into serials with Die Spinnen (1919 and 1920). The two parts have terrific things in them, but Lang never went on to finish it.

He was, however, still collaborating on screenplays for director Joe May, who specialized in epic serials set in exotic countries and starring his wife, Mia May. Highly entertaining though these films are, they are largely forgotten, even by most lovers of silent cinema. Das indische Grabmal is the exception, though even now few have had a chance to see it. In 1996 it was shown at “Il Gionate del Cinema Muto” festival in Pordenone and was all too briefly available on an Image DVD (as The Indian Tomb) now out of print. Track it down if you can.

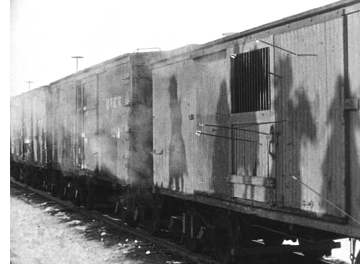

Full of the stars of its day, Das indische Grabmal is set largely in India, and its plot was inspired by the Taj Mahal. A ruthless maharajah (played with relish by Conrad Veidt) cloaks his cruelty under a veneer of European courtesy. He plots to shut his unfaithful princess (Erna Morena) in a beautiful tomb along with her lover (Paul Richter, better known to modern audiences as Siegfried). He calls in a famous European architect (Danish star Olaf Fønss) to build it, and the architect’s fiancée (Mia May), rightly fearing dirty work afoot, follows. One pit full of tigers and one of lepers lie waiting to endanger the visitors. The sets are beautiful. The Germans by this point could do them at full scale (above left) and as marvelously deceptive miniatures (above right). Das indische Grabmal is constantly entertaining and perhaps the best of its type, at least of the films we have access to.

Lang directed a two-part remake of this film in 1959. Both are good, but I prefer the silent one.

Some runners-up

As I mentioned, we had trouble narrowing down our list this year. Here are some others that could have replaced some of our prime choices. The German stage director Leopold Jessner adapted the play Hintertreppe (Backstairs). It’s a Kammerspiel, set in two apartments and the courtyard between them, and concerns a simple love triangle among a maid, her absent lover, and the postman who loves the maid so much that he forges letters from her sweetheart to keep her happy. Antti Alanen kindly reprinted my notes on the film here.

Carl Dreyer’s third feature, Leaves from Satan’s Book, remains one of the most widely-admired variants on the Intolerance formula of presenting thematically linked historical episodes. The dynamic final last-minute non-rescue shows that Dreyer learned a good deal from Griffith’s crosscutting too. Leaves is available on a Danish DVD with English subtitles and an alternate ending. Murata Minoru’s Japanese feature Souls on the Road, another exercise in complex crosscutting, and Feuillade’s polished L’Orphéline are solid runners-up as well. Neither is available on commercial DVD, as far as we know.

Destiny.

Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts

Kristin here:

The year 2011 has been a good year for silent cinema on DVD. In time for the holiday shopping season, here’s an overview of some of the highlights.

One-stop shopping for the latest restorations

In the past we have recommended films released on DVD through the Munich Film Museum’s Edition Filmmuseum. We haven’t really emphasized enough, however, what a major resource this site is for film enthusiasts interested in restorations of older films and new editions of hard-to-see modern films (like the work of James Benning). Edition Filmmuseum sells not only its own impressive series of releases but also DVD editions of restorations by other major national European archives. Its website is available in German and English versions, and it is as easy to sign up and order DVDs there as it is through Amazon. The DVDs on offer can be browsed via a number of different categories, such as “Silent films,” “German movies,” and “Danish classics.” Releases from Lobster Films and Flicker Alley are also available through Edition Filmmuseum. Have a look at its forthcoming releases here. North American educational institutions seeking public performance rights for many of these and other titles should contact Gartenberg Media Entertainment.

Scandinavia comes on strong

Danish and Swedish films show up fairly regularly on DVD these days, but Norwegian films are rarities. This year, though, there are two of them.

The Danish Film Institute continues to release the films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. This time it’s a pairing of Elsker Hverandre (Love One Another, 1922) and Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1926), also available in Blu-ray. (See below.) I have to admit that these are not among my favorite Dreyer films, and I don’t think many would put them alongside his best works. Still, Dreyer is one of the great masters of world cinema, and anyone seriously interested in film history will want to see these. Back when David was working on his book on Dreyer, we went to Copenhagen and saw these at the Film Institute. They were incredibly rare, and it was a privilege to see them. Now, they’re available to all. Check out the Institute’s entire list of restored Danish classics on DVD here.

[Dec. 16: Archivist Jan-Christopher Horak has recently blogged about Elsker Hverandre.]

The Bride of Glomdal is the first of our two Norwegian features. Dreyer worked outside Denmark a number of times. In the summer of 1925 he shot this film in Norway. His next film was to be La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

The second is Laila, a 1929 Norwegian feature, also with a Dreyer connection. Its director, George Schéevoigt, had been Dreyer’s  cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

Like many features made in countries with no real established film industry (Laila’s footage had to be processed and edited in Copenhagen), Laila exploits both national literature and landscapes to distinguish itself from the Hollywood films that dominated European theaters. It was based on an 1881 novel by J. A Friis, Fra Minmarken, Skildringer. Friis strove to promote the rights of the indigenous Sami people (sometimes known as Lapps). The story follows the heroine, Laila, from infancy to adulthood. The first half of the film succeeds in giving a distinctly non-classical feel to the story. Laila is lost in the snowy wastes when wolves attack her family as they travel on sleds. She is found and nurtured by a childless Sami couple who come to love her but return her to her parents when they learn her background. The scene of the return is handled in a subtle and moving fashion. As the grieving parents console each other on Christmas Eve, Aslag, the baby’s foster father, enters at the left, with the tree blocking the door. He crosses to appear at the center and puts the child beside the presents under the tree:

A cut-in to Aslag shows him struggling with his emotions before turning to the parents and declaring, “Tonight all should be happy.” The mystified parents stare at him uncomprehendingly before he explains that he had found their daughter:

Once Laila grows up, the film turns into the more typical romantic triangle. Still, its epic landscapes and focus on a little-known ethnic group make it quite appealing, and the print itself is gorgeous. Flicker Alley has provided a rare opportunity to step outside the more familiar filmmaking countries and explore a bit. Our friend, the fine Danish film historian Casper Tyberg, has provided a helpful text in the accompanying booklet.

Casper also provides a commentary for The Criterion Collection’s release of the restored version of Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Chariot. (It’s number 579 for you Criterion completists–but you already know about this disc anyway.) I won’t say much about it, since it will inevitably show up in our year-end list of the ten best films of 1921. Here I’ll just note that it’s also a beautiful print, with impeccable tinting and toning that don’t darken the images to the point where the composition is obscured–something I’ve seen too often in recent DVD releases of silent films. The frame above shows the opening scene, with its masterful control of lighting. I was disappointed that the supplements stress Sjöström’s influence on Ingmar Bergman. It may sound heretical, but Sjöström seems to me the better director, and I wish there had been more on his career.

One of the most obscure of German Expressionist films

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (“From Morning to Midnight”) is an early Expressionist film. It came out the same year as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. It’s based on a play by one of the major Expressionist dramatists, Georg Kaiser, and directed by one of the major Expressionist stage directors, Karlheinz Martin. The problem is, it never got released in Germany.

Most of the classic Expressionist films are, like Caligari, horror films that motivate their stylization through genre. Von Morgens bis Mitternachts adheres to the subject matter of Expressionist theater, which was vehemently critical of modern society. It centers around a downtrodden bank clerk who suddenly rebels against his apparently happy family life and good job, stealing a huge sum from the bank and trying to run off with a glamorous rich woman who visits the bank. Rejected by her, he wanders away to spend the money in frivolous pursuits.

It’s no wonder that German distribution companies shied away from releasing the film. Its only known theatrical screenings were in Japan, where one nitrate positive print survived. I saw an archival copy years ago. It was an impressive film, more extreme in its stylization than Caligari or even Robert Wiene’s second Expressionist film, Genuine. (All three films were released in 1920.) Unfortunately it had no intertitles, which made it seem all the more radical.

In 1987 censorship records were discovered that allowed the Munich Filmmuseum to reconstruct the intertitles and create the restored version that now has been released on DVD. It’s a significant film, not only as an artistic achievement but as a record of stage  Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts has some of the most avant-garde set designs of the era. Jagged white sets are smeared across back voids, as in the scene at the top where the protagonist flees down an endlessly winding road after being rebuffed by the woman for whom he impetuously stole money. It records another performance by one of the leading Expressionist actors of the era, Ernst Deutsch, whom I mentioned in my entry on Der Golem. Apart from its jagged sets, the film features a remarkable scene at a bicycle race, with the contestants being filmed in a distorting mirror. It was a technique that the French Impressionists would soon popularize, but Martin may have used it first (see left).

Despite the film’s lack of impact at the time it was made, it belongs squarely within the German Expressionist movement. This release at last allows it to take its place. (The forthcoming issue of the restored Expressionist science-fiction film Algol, also from 1920, will give an even broader picture of the movement.)

Eureka! Ford is found