Archive for the 'Directors: Méliès' Category

Beyond praise 5: Still more supplements that really tell you something

Real-time performance-capture images for The Adventures of Tintin.

Kristin here:

The Extraordinary Voyage (2011, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange)

I had expected to follow up my entry on Hugo when the DVD was released. I anticipated that its supplements would explore the flashy technical and artistic aspects in detail. But the lengthy first chapter proved to be largely the cast and crew presenting variations on how lucky they were to have worked with Martin Scorsese (and each other) and how much they learned from him.

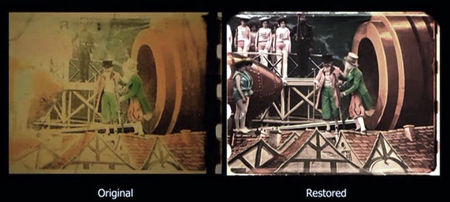

That wasn’t promising, and I turned instead to Georges Méliès himself. Flicker Alley, which has served the filmmaker so well in the past (see here), has recently released the restored color version of A Trip to the Moon in a Blu-ray/DVD combination set. It is accompanied by a 65-minute documentary on the Méliès, the film, and the restoration. It’s odd to call a 65-minute film that accompanies a fifteen-minute “feature” a supplement, but I recommend it anyway.

I suspect that The Extraordinary Voyage would be quite effective in easing students into very early silent cinema and intriguing them about an era that must seem hopelessly remote to them. It begins with a charming introduction to the context of the turn of the previous century and then moves quickly into the director’s young-adult life. When it comes to the famous incident in which Méliès’ camera jammed while he was filming, creating an inadvertent magical transformation, the filmmakers have an actual 1937 recording of Méliès himself describing the event. Presumably this was the original source of this oft-repeated anecdote. He specifies that it happened on the Place de l’Opéra and involved a bus turning into a hearse. I still wonder if it all happened so neatly, but hearing it directly from Méliès makes it a little more plausible. If it wasn’t true, it should have been.

The film includes as talking heads several filmmakers who admire Méliès’ work: Costa-Gavras, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Michael Gondry, Tom Hanks, and Michel Hazanavicius. There is a good summary of the fascination with the moon in popular culture of the day,  including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

The documentary touches on issues relevant to early silent cinema in general. One of these is the frequent pirating of films, with Méliès starting an American branch of his Star Films in New York, under the direction of his brother Gaston, to help protect his intellectual property. A clip from the Segundo de Chomon version of the film, An Excursion to the Moon, is included.

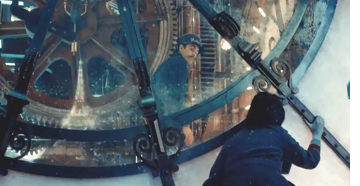

At about 23 minutes in, a short overview of early movie music is given, followed by a helpful explanation of how the hand-coloring of Méliès’ films was handled by a local workshop run by women. At 30 minutes in there are several dazzling examples of hand-colored scenes (right).

After a quick summary of Méliès’ decline and death, the film moves to the restoration of the only known hand-colored copy of A Trip to the Moon, found in the film archive in Barcelona. Here the hero is Tom Burton, the Director of Technicolor Creative Services, who gives a brief indication of how computers have transformed restoration:

We have a palette of digital tools to work from that are a collection of maybe five or six of the main commercially available restoration platforms, but then we also bring into the mix all of the approaches that you would use if you were doing visual effects for a modern movie.

The comparison of visual effects with restoration is in some ways an apt one and might lead students to look upon early films in a new light.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Blu-ray/DVD/Ultraviolet set, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

It’s probably a good idea to supply both Blu-ray and DVD discs in one package, but including the supplements only in Blu-ray is annoying and increasingly common. That’s the way the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo discs have been handled. Teachers without access to a Blu-ray player have fewer options when trying to use supplements in teaching. It also makes it much more difficult to make frame grabs from the supplements to, say, illustrate a blog entry on useful supplements.

I decided to check out the supplements for this film because the ones for Zodiac and The Social Network were so good. I figured David Fincher was particularly concerned about his films’ bonus materials. Unfortunately this set of supplements is quite uneven. The cast and crew seem to be obsessed with the character of the heroine and with the delights of shooting in Sweden. I confess that I stopped watching some of the chapters as the talking heads went on and on about these subjects. Some of the tracks also consisted of a lot of candid behind-the-scenes footage, which is all very well, but there was little structure to this and only occasional comments to explain what was going on.

Fortunately the “Post-Production” section is very informative and interesting. “In the Cutting Room” is fairly technical but makes some fascinating points. I particularly liked the description of how Fincher eliminates reframings and unsteady shots by using the extra image space allowed by newer capture media. (Earlier digital film frames allowed no extra image area outside what would show up on the screen; as the image below indicates, the final frame can be selected from a larger picture.) This desire for a stable image in an era where the “queasi-cam” so often rules points to one distinctive trait in Fincher’s style. It indicates a willingness to actually think through the framing of each individual shot and the purpose for choosing that framing. Steven Spielberg does the same thing. Many don’t.

Editor Angus Wall talks about this advantage of the extra size of the image and how Fincher uses it to stabilize unsteady images. It’s worth quoting at length, and it demonstrates the thoughtful commentary in this particular supplement:

I’ve never seen a movie that was sort of “re-operated” to the extent that this one was. Which I think has an effect on the viewing of the movie. David is really type-A in terms of making the shots very specific. They start in a certain way, they end in a certain way. And the framing, he’s very precise in terms of his composition. He doesn’t like a lot of what you see in 99% of movies, which is very subtle moves where the operator will actually reframe according to how the actor’s moving. David doesn’t like that. Even if there were a lot of those in this film, and before, some of those takes we would have thrown out, because we just wouldn’t have been able to stabilize them to the degree that he likes it. With this, because you have this full raster, this big area around the image, you can take those images and stabilize them, really lock them down. So the movie is really locked down in terms of camera operating. More than any other movie that I can think of.

The smooth glide as the car initially approaches the country house is one example of that utter stability, used to ominous effect in that particular scene.

There’s also some interesting discussion about how the two main characters don’t meet each other until well into the film and how that affected decisions about editing. Rather than frequently intercutting between Mikael Blomkvist and Lisbeth Salander, the filmmakers decided to create longer self-contained scenes involving each, thus switching back and forth less frequently. The idea was that the exposition set forth in each scene would be too difficult to absorb if it was chopped into smaller segments. Form, style, and function, neatly explained.

Fincher also points to an interesting underlying anxiety the spectator might feel because the narrative progress gives little sense of how much action is still to come:

You don’t know where you are in the narrative. You don’t know if you’re at the beginning of the third act or … I don’t think it’s bad, because we have a five-act movie. I think that’s what’s causing everybody’s anxieties, that it doesn’t feel like, OK, here’s where we are, we’re entering the third act now. Now it feels like, fuck, this movie could go on … indefinitely. That’s the part that’s bothering me. If we told them it was going on for another forty-five minutes, they wouldn’t have a problem. It’s the indefinite part.

Since I’ve written a book claiming that classical films usually don’t have three acts, I was intrigued by this statement. (See also my earlier blog entry here and David’s essay here.) I posit instead that classical films typically create acts that run about 25 to 30 minutes, and that the film’s length determines how many acts it has. Four acts is the most common throughout Hollywood’s history, but a 158-minute film would be likely to have five acts. (Has David Fincher read my book?!) His point about the audience feeling a bit lost in an unconventional narrative structure is a rare instance of a director talking about form in such an abstract way, and it seems quite valid for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

It’s also rare to get a supplement on ADR (automated [or additional] dialogue replacement), but there’s a six-minute one in the “Post-Production” section. This consists of a behind-the-scenes session with Rooney Mara supplying not just dialogue but breathing, grunts, and other noises. It’s clearly a real session, not a staged one, though the actress does seem a bit self-conscious with the documentarian’s camera turned on her. Fincher’s and Mara’s banter between takes gives a sense of what I suspect really goes on during this phase of production.

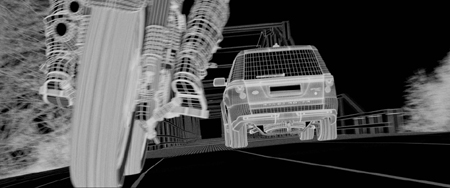

There’s a brief supplement called “Main Titles,” which deals with the form and inspiration for the CGI under the titles. Fincher wanted to tell the story of the whole trilogy in two and a half minutes, “and it has to be spectacular.” Apart from the discussion of form, there’s a good look at unrendered CGI footage compared to the finished images.

Finally, an eight-minute “Visual Effects Montage” displays a variety of special effects in a clever way. There is a section at the beginning where we are shown the image without added effects, then the same image with the areas to be altered highlighted in various superimposed colors, and finally the finished images with the effects added. This is particularly good for showing the sorts of mundane effects that are used to enhance shots unnoticeably, adding cars’ headlight beams, reflections in glass, falling snow, and the like. There is a shot with a section of a building on location blotted out with a greenscreen and the final shot showing the use of alterations in the building:

Obviously here the fog was also added with CGI.

This montage goes very quickly. If you’re using it in a class, best to prepare ahead and be ready to pause and point out what’s going on in the many short shots used in the demonstrations.

The second half of the effects montage moves to splashier scenes of the type the public associates with “special effects”: wire-frame vehicles for a chase (see image at the top of this section), head-replacement to add Mara’s head to her stunt-double’s body, and explosions.

Don’t bother with the “Stockholm Syndrome” section. Basically all we learn is that when a scene is shot on location, sheep can unexpectedly wander in and interfere.

The Adventures of Tintin (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital Copy combo, Paramount Pictures)

Again, the supplements for this release are available only in Blu-ray.

Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson decided some years ago to collaborate on what was announced to be a three-film series adapted from Hergé’s Tintin comic books. The notion was that each of them would direct one film, with an as-yet-unspecified director doing the third. Spielberg’s initiatory film did not do as well at the domestic box-office as had been hoped, though it fared better in Europe and other non-North American markets, where the comics are highly popular. Jackson has announced that after he finishes both parts of The Hobbit, he will launch into the next Tintin film. (At least, that’s what he said originally. After yesterday’s announcement that there will be three Hobbit films, his start on the Tintin film will presumably be delayed.)

The supplements form a narrative of the film’s making, bookended by “Toasting Tintin” and “Toasting Tintin Part 2,” brief episodes set at the launch and wrap parties. The tale is pleasant and generally worth watching, though they are far from as entertaining and informative as the supplements that Michael Pellerin produced and directed for Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings and King Kong DVD sets. But this is Spielberg’s show, since he did the first film and indeed originated the project. At first he envisioned the film as live-action, with the dog Snowy the only major CGI character. Spielberg asked Jackson’s effects house Weta Digital to do some tests animating Snowy. To his (apparent) surprise, Jackson himself, as a fan of the comics since childhood, played Captain Haddock in the test. That fact was well known to fans, and the inclusion of the test footage (above) is no doubt a crowd-pleaser.

The decision to use cutting-edge performance-capture techniques led to the film being entirely animated.

“The World of Tintin” gives background on Hergé and deals briefly with the screenwriting process. This leads into “The Who’s Who of Tintin,” dealing with characters and acting, with some good material on performance capture near the end. The next section, “Tintin: Conceptual Design” has good material on the visual style of the characters and near the end includes some pre-viz material.

The outstanding supplement, however, is “Tintin: In the Volume,” nearly 18 minutes of footage concerning performance capture. Spielberg’s role as director was primarily concentrated into a remarkably short 31-day shoot with the actors. This was done in a state-of-the-art performance-capture facility called “The Volume” and located at Giant Studios. The Volume is a large space with about 160 cameras built into the ceiling and pointing down into the performance space. These capture the space from multiple angles. Additional cameras on the stage level follow the actors’ movements, which are inserted into the space. Moreover, hand-held monitors similar to portable gaming devices allow the filmmakers to see simple versions of the settings and the partially rendered characters while pointing the device at the actors in their performance-capture rigs.

There are also larger monitors that show the actors their own performances translated into the characters (top of entry). Whatever one thinks of the look of contemporary animation of this type, the technology has evolved to a remarkable level, and this supplement provides an excellent explanation of the practicalities of performance capture. We see the motion-capture suits being put on and the dots painted onto the actors’ skin. There is also information on how the set elements and props need to be transparent so that the cameras can capture the dots on the actors’ faces and costumes through them. The image at the bottom shows Jamie Bell as Tintin looking at a mock-up of the model ship. It’s made of little metal rods and rendered into a ship on the monitors.

“Snowy: From Beginning to End” is less cutesy than it sounds. It discussed the digital tool developed for modeling the dog’s fur. There’s also good stuff on how several dogs were recorded to provide different-sounding barks depending on the type of action in a scene.

The biggest tasks on the film came after the performance capture and editing. Weta Digital spent two years creating the final images. “Animating Tintin” is an excellent eleven-minute account of that process.

The sections “Tintin: The Score” and “Collecting Tintin” (on Weta Workshop’s designs for the collectible figures) are rather thin and could be skipped unless a teacher wants to show the whole set of supplements as a single “making-of” documentary.

It’s become apparent that many of the best supplements on Blu-ray and/or DVD releases are devoted to special effects, especially performance capture. The Adventures of Tintin does genuinely involve innovations in this technology, and the “In the Volume” chapter is very informative. Supplements are getting repetitive, though, and I would like to see the producers of such documentaries pay more attention to techniques and choices in other areas. Comparing final cuts of scenes with earlier cuts, or showing story conferences where real debates about scripts occur (as was done in the first Pirates of the Caribbean film’s supplements), or displaying how decisions about digital-intermediate grading are made–a bit of imagination could spice up the offerings. That and a realization that film fans are interested in just about any aspect of production (or distribution, for that matter). Supplements risk falling into conventional patterns, and that won’t make them the appealing bonus material that they used to be.

While I was gearing up to write this entry, we received Mark Parker and Deborah Parker’s book, The DVD and the Study of Film: The Attainable Text (Palgrave, 2011). Based on a great deal of research, including many interviews, the authors include a summary history of DVDs and supplements; there is a detailed chapter on The Criterion Collection, interviews with directors and scholars who have recorded commentary tracks, and a case study of Atom Egoyan.

HUGO: Scorsese’s birthday present to Georges Méliès

Kristin here:

This is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Georges Méliès (1861-1938). I doubt that the release of Hugo was timed to coincide with the occasion. If it were, no doubt the press kits issued by Paramount would have stressed the fact. Still, it’s a happy coincidence.

Hugo is receiving a lot of press attention, not surprisingly. If you’ve read more than one or two of the reviews and articles about Martin Scorsese and his film, you already know the two main hooks that journalists have hung them on. (Whether these originate from the pressbook or are just so darned obvious that everyone can figure them out, I don’t know.)

One, Scorsese is passionate about film history and preservation, so Brian Selznick’s best-seller quasi-graphic novel for children, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, based on the old age of early director George Méliès, would be a natural source for him to adapt. Especially so, since Selznick designed the illustration-heavy book to imitate a film, with series of drawings suggesting camera movements.

Two, the subject of Méliès’ pioneering special effects in the service of fantasy would be the perfect vehicle for Scorsese’s first venture into 3D.

True, no doubt, both of those points, and necessary to ease viewers with no knowledge of film history into this fairly sophisticated film. Not that the critics provide much help with the film’s many allusions to Parisian culture of the first decades of the twentieth century. There are real popular songs and posters for many silent films. I didn’t see any reviews pointing out that James Joyce and Salvador Dalí can be glimpsed fleetingly in Madame Emile’s café. (I spotted Joyce but not Dalí, only learning of the latter’s presence from the credits.)

Apart from signalling such references, however, there is a great deal more that one can say about the film. Some aspects of it are obvious, as befits a movie made in part for children. Others are more subtle, as befits a movie made in part for adults. I’ll offer a few observations here.

By the way, reviewers have made much of the idea that Hugo is not really for children, who would be bored and perhaps frightened by it. I suspect that children under about the age of 10 would be, but older children and teenagers, especially those who read books, should be intrigued by and enjoy it. Like Pixar films or The Simpsons, it’s the sort of thing that can be enjoyed by adults as well as children.

Movies within movies

Hugo is centered around Méliès’ work and tries to recreate something of the magic of the making and viewing of these films. Yet beyond this, it is steeped in the forms and subjects of pre-World War I cinema in general, to the point where the plotlines of Hugo subtly imitate early films.

A turning point in Hugo‘s story comes when Hugo and Isabelle invite fictitious film historian René Tabard (whose name is borrowed from the popular, Chaplin-impersonating teacher young student in Zero for  Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

In the book, the station’s Inspector, played by Sacha Baron Cohen, is a minor figure, glimpsed once from a distance by Hugo and finally coming to threaten him with arrest on page 412. His war wound and early life as an orphan are not part of his character. The Inspector is abetted by the café owner Madame Emile and the newsstand proprietor Monsieur Frick, sinister figures who appear only in this single late scene. They exist primarily to reveal the news of the discovery of the corpse of Hugo’s drunken uncle and to bear witness to Hugo’s thefts of croissants and milk from the café. The flower-shop girl, Lisette, whom the Inspector clumsily courts in the film, is not in the book at all.

What Scorsese very cleverly does is to expand these characters and have them play out what are in effect two brief narratives that could easily be imagined as early silent shorts. Madame Emile (Frances de la Tour) and Monsieur Frick (Richard Griffiths) are transformed from nasty busybodies into a charmingly comic elderly couple whose tentative flirtation is thwarted by Emile’s aggressive dachshund. In two scenes, the dog bites Frick, once on the finger and once on the ankle. In the third scene, Frick solves the problem by providing a lady dachshund to divert the pesky pooch’s attention. One could easily imagine this as a short film from around 1906, making these two the leads and concentrating on their courtship. The dog could thwart the news-vendor’s approaches a few times before the happy ending is achieved with the introduction of the second dog.

The overbearing Inspector’s romance with Lisette is developed at greater length, and one could imagine it as a one- or even a two-reeler of the early 1910s. The Inspector’s attempts to court the young lady could be contrasted with his chivvying of the pathetic young orphan, actions that make her reject his advances. At the end, she might witness him relenting and treating the boy kindly, as indeed happens in Hugo, leading to another happy romantic conclusion.

In general, the situations and characters that we encounter in Hugo are common in early cinema. How many films, especially French ones, involve gendarmerie with their round, flat-topped caps, chasing mischievous little boys? How many melodramas revolve around poor children made homeless by their parents’ or guardians’ drunkenness? How many gags involve men stepping on musical instruments and smashing them? While the most explicit cinematic reference is to the Harold Lloyd feature Safety  Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

In a sense there are little topical and instructional films as well, with the reference to the dramatic historic accident at the Gare du Montparnasse on October 22, 1895, when a train crashed through its buffers and out the front wall of the station. (In reality, one death occurred: the wife of a news vendor who was minding the shop for her husband. Perhaps the Emile-Frick romance creates a happy ending of the cinematic variety to make up for that tragedy.) We also have the lesson in cinema history provided by Tabard. At one point in the flashback narrated by Méliès, apparent newsreel footage of World War I troops, touched up with hand-coloring, appears.

The film-like subplots all end happily, yet they are represented as being reality within Hugo. Perhaps for that reason, none of these brief narratives is the sort that Méliès would have used in his own films. They’re more like the non-fantastical comedies and chases made by Louis Feuillade and other directors.

The happy ending for Méliès occurs in Scorsese’s film, and yet it also happened in reality, if not quite the way it is shown here.

Cruelty, kindness, and the shape of the story

The structure of the narrative reflects the simplicity of each short film. It conforms well to the four-part narrative structure that I have claimed to be conventional practice in classical storytelling. Yet it also breaks neatly into two halves, the first about cruelty and the second about the sort of kindness that makes possible the happy endings. One can picture it as a V shape, with Hugo descending into greater loneliness and danger up to the mid-point and then climbing back toward happiness with the help of others.

Early on, both fate and other people are cruel. A museum fire has killed Hugo’s father, and his mother had earlier died of unspecified causes. Hugo’s drunken uncle wrests him from his home and school to live a fugitive life in the station. “Papa Georges,” whose full identity we do not learn until well into the film, seems unnecessarily harsh with the young Hugo. The Inspector obsessively hunts down stray children to send off to the orphanage. The bookseller Labisse, though generous in loaning books to Hugo’s friend Isabelle, looks upon Hugo with disdain. Even the two dogs, Madame Emile’s comic dachshund and the Inspector’s doberman are growling, threatening beasts.

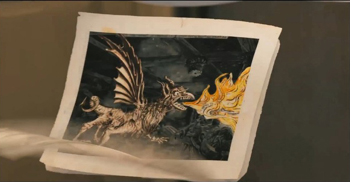

The automaton, of course, is the key to all. Once it provides the necessary clue by drawing the  famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

Ordinarily at this point in a Hollywood film, there would come a section where the protagonist struggles against obstacles to achieve his goal. In Hugo, however, the crisis at the center leads immediately to a series of kind actions. Upon returning to the station after the drawings discovery, Hugo runs into M. Labisse, who unexpectedly gives him a book that the boy and his father had read together. Then Madame Emile urges the Inspector to speak to Lisette, whom he has admired from afar, and coaches him in how to smile pleasantly. His smile, plus his halting success in his first conversation with Lisette, motivate his eventual ability to take pity on Hugo.

This scene leads directly to the scene at the “Film Academy Library” (a giant fictitious room full, apparently, of books on cinema) where the film historian and Méliès fan, René Tabard, appears. He will provide the screening of A Trip to the Moon which finally draws Méliès out of his depression to some degree. Yet the filmmaker still despairs as he thinks of the disappearance of his studio, the rest of his prints, and his beloved automaton. Hugo rushes off to fetch the latter, and after an extended chase sequence returns it to Méliès with the help of the Inspector, who saves the machine and the boy from an oncoming train. Recognizing something of his own youth in the distraught boy, the Inspector turns him over to Méliès for the happy ending.

The exception to the cruelty/kindess division of the film is Isabelle. In the original book she is not such a pleasant character, often arguing with Hugo. She does not have the joyous desire for adventure that the Isabelle of the film displays. The change is an improvement. In part this is because Hugo is such a very grim and forlorn character through much of the book. Portraying him that way in the visual medium of film might make his plight too pathetic to be entertaining. Isabelle’s early sympathy for him and fascination with the mystery of the automaton carries a strong thread of hope across both halves of the narrative.

In the lengthy epilogue there is a gala screening of some recovered Méliès prints, and a party is held. All the significant characters are present, with their satisfactory futures assured. Hugo will seemingly become a magician (as he does in the book). Isabelle has apparently found her hoped-for purpose in life, for she starts writing down the story that we have just witnessed. (In the novel, Hugo himself writes The Invention of Hugo Cabret, though he attributes it to the automaton.)

A machine-made ending

The film ends with a tracking shot, independent of the characters’ points-of-view, into a nearby room where the automaton sits, still and alone. As we approach its enigmatic face, the image fades out. The moment ends the imagery that has continued through the film, of humans as machines and  machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

The machine imagery goes further. The opening of the film dissolves from a set of moving clock gears to merge them graphically into a high view of the boulevards of Paris, which momentarily appears as a giant glowing, whirling machine with the Eifel Tower, symbol of the modern machine aesthetic, at its center. The repair of a wind-up mouse becomes the first small point of emotional contact between Méliès and Hugo. The Cinématographe camera/projector that fascinates Méliès even more than the moving images on the screen becomes the central machine, one which produces what one normally thinks of as the most private and mental of events, dreams.

All this machine imagery is fairly obvious, but it seems completely appropriate if we remember that this is, after all, a film partly for children. What I’ve been describing are things that a smart child could grasp, but the imagery and story aren’t done in anything like a condescending way.

The automaton, by the way, really did the drawing in the film itself, without CGI or other sorts of animation being used. For a three-minute film that ends with a fast-motion demonstration of its drawing capabilities, see here. For a demonstration of the restored Maillardet automaton in the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, which Selznick used as his inspiration, see here, where it creates a drawing as complex as the one in the film. This automaton also revealed its origins when, after being restored, it signed its maker’s name.

[Dec 9: My claim that the automaton did the drawing without special effects was based on some statements by the company that made it (or more specifically, 15 versions of it). A recent article here interviews the film’s visual-effects supervisor Rob Legato reveals that the drawing scene was accomplished using magnets below the table: “The robot or automaton was not CG, although there were some CG doubles for some complex shots such as the train line fall. Prop builder Dick George constructed 15 automaton versions and some that actually could draw on paper. The VFX and special effects team solved the complex task by using magnets. Below the paper was a motion controlled magnetic system that traced the hand encoded drawing. The arm then moved to match the magnets and draw the famous picture. In a couple of shots if you could pause and really study the frame you might see that the pen nib, at those points, ‘is a ball point and not an ink well pen,’ comments Legato.” So the automaton did do the drawings, but not based on its complex system of gears and other clockwork visible inside it.]

How accurate is it?

Naturally the events of history are messier than the neat scenario of a mainstream film could encapsulate. Still, given the constraints involved, Hugo‘s modifications of the facts seem quite reasonable, and on the whole the general public will exit the theatre with a decent impression of Méliès’ career.

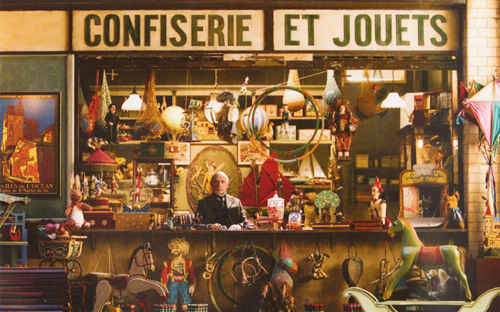

In fact he was married twice. Jehanne d’Alcy had been Méliès’ mistress well before they married in late 1925. They had both worked at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin before the cinema was invented, and d’Alcy appeared in many of Méliès’ films. (His first wife, Eugénie, died in 1913.) D’Alcy brought with her the ownership of a little candy-and-toy shop outside the Gare Montparnasse, which the couple transferred inside the station and ran together (see bottom). World War I did not cause the demise of Star Films. Méliès had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

As biographer Paul Hammond describes his decline, “Georges Méliès had become an anachronism, an artist left behind by economic and aesthetic developments.” In looking at Méliès’ late films, we might keep in mind that 1912 was the year of Albert Capellani’s remarkable serial adaptation of Les misérables. Max Linder was at the height of his popularity, and D. W. Griffith was making some of his finest one-reelers. The three great Swedish silent-era directors, Mauritz Stiller, Viktor Sjöström, and Georg af Klercker, all made their first films in 1912. The year 1913 would see a burst of cinematic inventiveness around the world, and Méliès would have seemed all the more old-fashioned by comparison had he continued to make movies. Nevertheless, he remains perhaps the only one of the very earliest generation of filmmakers whose work we return to not simply out of historical interest but for the fun and wonder of the films.

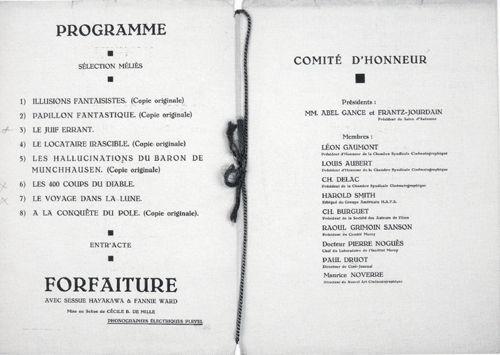

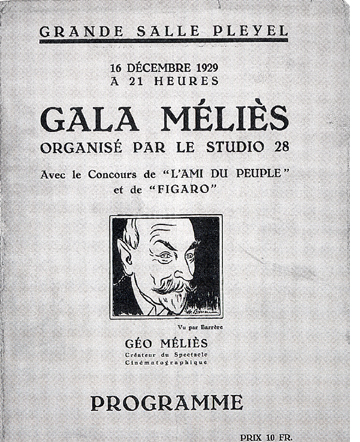

The rediscovery of Méliès began earlier than it does in Hugo, and it was more gradual. The mid-1920s were the nadir of his career. He and d’Alcy were living in a tiny flat in impoverished circumstances. In 1926, Méliès was notified that he had been made the first honorary member of the Chambre Syndicale Française de la Cinématographie–a trade organization, not an academic one like the fictitious “Film Academy” in Hugo. In 1929, J.-P. Mauclaire, director of the early art cinema Studio 28, found a batch of twelve tinted copies of Méliès films. New prints of the most damaged ones were made, and a screening of eight of them was held in a “Gala Méliès” that also included a revival of Cecil B. De Mille’s The Cheat:

In 1930 another program of Méliès films was shown, and in 1931 he received the Cross of the Legion of Honor. A benefactor provided Méliès and his wife with a larger apartment, and in 1934 he was made the honorary president of the Chambre Syndicale de la Prestidigitation. Ill health prevented him from pursuing some tentative filmmaking projects originated by admirers within the film industry, and he died of cancer in 1938. His granddaughter Madeleine ultimately became a champion in the revival of his memory. (For more on Méliès’ later life, see Paul Hammond’s Marvellous Méliès, pp. 80-85.)

Given all this, I think Scorsese and scriptwriter John Logan have done a reasonable job of condensing and tweaking the facts of Méliès’ story. The filmmakers also deserve considerable credit for showing the filmmaker cutting and splicing a strip of film involving a stop-motion effect. Méliès was long dismissed as not being much of an editor, having supposedly just stopped his camera and started it again to allow for the substitution of different items of mise-en-scene. We now know, however, that his amazingly well-matched transformations depended on eliminating just the right number of frames to create the magical illusion. He was a skillful editor indeed, and the filmmakers display that fact.

3D and Autochrome

Commentators naturally have stressed the fact that Scorsese has made his first 3D film. Up to now major filmmakers have embraced the technology, but most, like James Cameron, have worked in action genres. Could one of the “movie brat” generation redeem what has come to be seen as a technology that is rapidly losing its novelty value and perhaps its economic viability? The BBC even ran a story bluntly entitled “Can Martin Scorsese’s Hugo save 3D?” It and Steven Spielberg’s first 3D film, The Adventures of Tintin, have widely been seen as the crucial test of whether the use of 3D will continue to expand.

No doubt Hugo represents the best that can be done with current 3D technology. For once, every shot was filmed in 3D. Most 3D films, even Avatar, have at least a few images done with  post-production conversion. (See the December, 2011 American Cinematographer article on Hugo, p. 56.) The filmmaking team went to extraordinary lengths to shoot as they wished to. They settled on using Arri’s new digital camera, the Alexa. The production required four cameras at a point when Arri was just beginning production, but the company managed to provide all four.

post-production conversion. (See the December, 2011 American Cinematographer article on Hugo, p. 56.) The filmmaking team went to extraordinary lengths to shoot as they wished to. They settled on using Arri’s new digital camera, the Alexa. The production required four cameras at a point when Arri was just beginning production, but the company managed to provide all four.

Cinematographer Robert Richardson has remarked on the idea of avoiding conversion: “If, as a film team, you’re not all working to best enhance in-camera the three dimensions then I would ask why have you committed to constructing a labour of love that someone else will eventually deliver to you via post conversion and say, ‘Here is your film.’ That might work for some projects and directors … but for me that choice felt insanely wrong. Commitment is required.”

Editor Thelma Schoonmaker has said of the 3D style “It’s not so much about stuff in your face—though there are a few wonderful shots like that. But more it’s about pulling the characters forward and feeling you’re in the room with them.” (Both quotations from Screen International [25 November 2011], p. 19.)

David and I went to see Hugo in 3D last week. Recently I have only seen a few 3D films: Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Wenders’ Pina, and Miike Takeshi’s Harakiri. Art-house films all, and apart from the Herzog film, where 3D serves educational rather than aesthetic functions, I didn’t think the 3D added much. James Cameron has said that Hugo is the best use of 3D he’s seen, and he should know.

I’ll admit that there are some terrific effects. The decision to have the Inspector’s doberman’s pointed muzzle coming out at us as it chases Hugo is clever and funny. But there’s still the blur and juddering of objects in the foreground, something that isn’t helped by the breakneck pace at which Scorsese “tracks the camera” through huge spaces or long tunnels. (Most of these shots involved as many special effects as actual camera movements.) I frequently wished in the course of the screening that I was seeing the film in 2D.

Apart from everything else, 3D pretty much necessitated that David and I move out of our habitual and preferred “front zone” of the theatre. Not only do 3D effects not work as well if you’re up close, but the edges of the screen are outside the frames of the glasses’ lenses. Turning your head when you’re sitting close and watching a 2D film is one thing; it’s quite another with those glasses on. So we sat further back. We also raised and lowered our glasses at intervals, checking out the amount of light being filtered out by those RealD glasses. It was quite a lot.

A few days later I went to see Hugo again, this time in 2D. The movie looked beautiful, with brighter images and more vivid colors. There was less blur in the fast camera movements. The depth cues in the images were strong enough to make such shots as the high-angle views down the vast clock tower impressive. And I was able to sit closer.

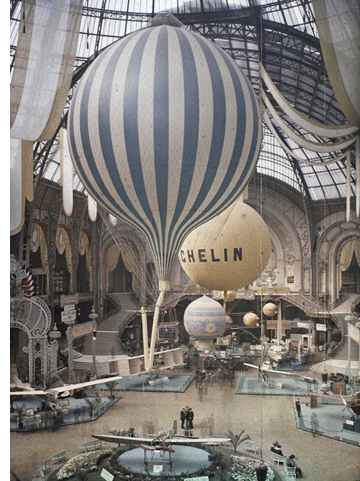

The brighter colors were important, since the filmmakers made an attempt to imitate a  photographic color system of the early-cinema era. Specifically, Scorsese and Richardson aimed for the look of the Lumière brothers’ Autochrome system; this was the principal color system used in still photography until the 1930s. The digital grading used for Hugo played a big role in the attempt to achieve this look of early color. The American Cinematographer article mentioned above contains three sets of images demonstrating the stages of achieving the final look of Autochrome. A scan of one such set of images is available online. Just how authentic-looking the results are, I can’t say. (At right, a 1909 photo of an air show in the Grand Palais, Paris, by Léon Gimpel; for an extensive set of Autochrome photographs, see here.) Still, it’s a more interesting technique to those of us who aren’t fond of 3D, and I found that it gave the movie a color scheme that’s much more interesting than the standard look of films these days.

photographic color system of the early-cinema era. Specifically, Scorsese and Richardson aimed for the look of the Lumière brothers’ Autochrome system; this was the principal color system used in still photography until the 1930s. The digital grading used for Hugo played a big role in the attempt to achieve this look of early color. The American Cinematographer article mentioned above contains three sets of images demonstrating the stages of achieving the final look of Autochrome. A scan of one such set of images is available online. Just how authentic-looking the results are, I can’t say. (At right, a 1909 photo of an air show in the Grand Palais, Paris, by Léon Gimpel; for an extensive set of Autochrome photographs, see here.) Still, it’s a more interesting technique to those of us who aren’t fond of 3D, and I found that it gave the movie a color scheme that’s much more interesting than the standard look of films these days.

[Dec 9: A new interview with Robert Richardson by Bill Desowitz has just been posted here. It deals with 3D and Autochrome.]

Scorsese, journalists, and the legacy of Méliès

The reviews and coverage of Hugo in the trade and popular press have rightly emphasized Scorsese’s love of cinema history and his devotion to film preservation. He has collected high-quality 35mm prints of classic films, many of which are on deposit at the George Eastman House archive. Scorsese also helped found the Film Foundation in 1990 and the World Cinema Foundation in 2007. The latter organization has provided preservation work for films made in countries where either there is no national archive or where the archive lacks the funds and facilities for major restoration/preservation projects. Having first seen the Egyptian film The Night of Counting the Years (Al-mummia, 1969) in a battered 16mm copy, I was delighted to watch a beautifully restored 35mm widescreen copy at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in 2009. There is no doubt that Scorsese’s contribution to the film-restoration effort has been immense.

That said, I think some of the press coverage of Hugo has pushed Scorsese’s interest in preservation a bit too far in the case of Méliès, giving the impression that somehow the director has led a rediscovery of the early film pioneer as thorough as the one accomplished by Hugo and his friends in the fictional account. In The Hollywood Reporter’s story, “The Dreams of Martin Scorsese,” Jay A. Fernandez writes, “Over the years, Méliès has become a mystery himself, and even film buffs often don’t have a grasp of just how profound his contributions to cinema were, despite their efforts to piece together the scraps of his legacy. In this, he could not have better cultural archaeologists than Selznick and Scorsese.”

One might overlook a journalist (albeit one who specializes in entertainment news) believing that Méliès really was virtually forgotten among all but a few film historians before Hugo came along. But he goes on to quote Selznick, whose words might carry more weight, as saying of Scorsese, “Of course, Scorsese has been responsible for restoring the lost legacies of groundbreaking filmmakers. He is in the position of pointing the way for the public, showing us who has been forgotten and overlooked.”

That’s going a bit far. Admirable and important though Scorsese’s preservation efforts have been, and valuable as his video histories of topics like Italian cinema have been in bringing film history to a broader public, he cannot be said to have been responsible for rediscovering major filmmakers who have been forgotten. I doubt he would claim to have done so.

The work of Méliès has been covered in the basic histories of world cinema for at least the past fifty or sixty years. Indeed, the rediscovery of Méliès that began in the 1920s has continued ever since. Unfortunately, most of the coverage of Hugo passes over the diligent and successful work of archivists who have been the mainstay of that rediscovery.

The friends of Méliès

Méliès played a small but important role in my own early discovery of cinema history. During the spring of 1970, I was taking my first film course, a one-semester survey history, at the University of Iowa. As I recall, it was during that time that a representative of the Library of Congress came to campus and gave a talk on film preservation. He showed two hand-painted shorts, one of which was Méliès ’ Le Raid Paris-Monte Carlo en deux heures. The color was crude, to say the least. In 1905, without the benefit of a stencil, someone had daubed a dot of red paint onto the race-car in each frame, leaving the rest of the image in black and white. The result looked like a flickering, burning car was driving through magical landscapes. I found it quite fascinating, and that, along with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari, were the films that really lured me into film studies and a career. I regret that the prints of Le Raid used for the DVD releases of Méliès ’ work have not included this clumsy but charming hand-coloring.

During my years in graduate school, the general claim was that something like a hundred of Méliès ’ output of around 500 shorts survived. By now, the number is more like slightly over two hundred. Occasional discoveries continue to be made.

In 2008, when Flicker Alley put out its monumental five-disc set, “Georges Méliès : First Wizard of Cinema (1896-1913),” it contained 173 films—not quite all of those that were known at the time to survive. In 2010, the same company released “Georges Méliès : Encore” appeared, a single disc with 26 newly discovered prints. (I note that both are temporarily out of stock at Amazon, suggesting that Hugo has generated new interest in Méliès.) For our comments on the “Encore” disc, see here.

This flow of rediscoveries has been due to archivists like Paolo Cherchi Usai at Eastman House and Serge Bromberg at Lobster Films (two of the many archives contributing to the set released by Flicker Alley in the U.S.). David and I played a modest role in one such discovery. We spotted an ad in a film-collectors’ publication, offering for sale a nitrate original of a hand-colored Méliès film. We alerted our friend Paolo, who obtained the film; it turned out to be a lost Méliès title from 1899, in excellent condition.

Lobster Films appears in Hugo’s credits as the supplier of many of its clips from Méliès films. I wish more journalists would have made mention of Lobster. So far the only reference I have found is in Susan King’s story for the Los Angeles Times, “‛Hugo’ revives interest in Georges Méliès.” She includes a brief overview of Lobster, as well as a list of Serge’s suggestions of six Méliès films “that are must-sees.” (For our coverage of an encounter with Serge in Paris last year, including a 3D projection of part of a Méliès film, see here.) This article also contains the happy news that next year will see the release of a DVD containing the recently restored hand-colored version of A Trip to the Moon (bits of which are glimpsed in Hugo) and a documentary concerning the restoration, The Extraordinary Voyage.

Méliès has also been known to the public, at least in France and the U.S., though some lavish exhibitions and publications. Fortunately many of his designs and drawings have survived. Copies of them are tucked away in the armoire in Hugo. There are also numerous photographs and objects from the era. A 1991 exhibition at George Eastman House, “A Trip to the Movies: Georges Méliès Filmmaker and Magician (1861-1938),” was accompanied by an anthology of essays of the same name. In 2002, the Parisian show “Méliès, magie et cinema” resulted in a coffee-table book of the same title. In 2003, the Cinémathèque français held another exhibition, “Georges Méliès, magicien du cinéma”; it occasioned the publication of a large volume, L’oeuvre de Georges Méliès, which catalogued the archive’s holdings in gorgeous reproductions.

Historical reference books have not been lacking. In 1975, Paul Hammond published his Marvellous Méliès, a thorough and still useful book. It was followed by John Frazer’s excellent Artifically Arranged Scenes: The Films of George Méliès. There are other books on Méliès, too numerous to list in full here.

Since 1961, “Les amis de Georges Méliès,” a group founded by the filmmakers’ descendents (who are acknowledged in Hugo’s credits), have fostered the rediscovery and preservation of his legacy.

Now, go and watch Le Déshabillage impossible (1900, disc 1 of the Flicker Alley set), a two-minute film that remains as astonishing as it is hilarious. If you’re not a friend of Méliès now, you will be after seeing it.

[Dec 7: Thanks to Mark McElhatten for pointing out the mistake concerning the character Tabard in Zero for Conduct, a mistake which has apparently appeared in some reviews of Hugo.]

[Dec 8: Thanks to Paolo Polesello for reminding me that the rediscovery of Méliès included Georges Franju’s short film, Le Grand Méliès, 1952; it’s included in the five-disc Flicker Alley set.]

[Dec. 12: Today Variety posted a story about modern designers and special-effects experts who have been inspired by Méliès, in particular those who have eschewed CGI and opted for prosthetics, animatronics, and miniatures.]

DVDs for these long winter evenings

Kristin here:

Coming back from a trip has pleasant and unpleasant consequences. Bills piled up, but so did stacks of packages, books and DVDs we forgot we had ordered or ones sent to us out of the blue.

The intrepid companies that rescue and issue silent films on DVD have been busy. All are past winners of awards in the Cinema Ritrovato festival’s annual ceremony, and obviously they are working hard to keep their standards up. (For a pdf listing all the winners since the awards began in 2004, click here.) Two of my favorite directors are represented.

Much More Méliès!

In 2008, Flicker Alley won “Best Box-Set” for its monumental collection “Georges Méliès: First Wizard of Cinema” (five DVDs with 173 films). Amazingly, 26 more films (or fragments, in one case very short) have been discovered since its issue. These will be released in the U.S. on February 16 on a single disc titled “Georges Méliès Encore.”

One of these, Le Manoir du Diables/The Haunted Castle, from 1896, contains something like 26 cuts, all stop-motion effects. I wouldn’t have thought such an elaborate production would have been possible so early in the history of cinema, but here it is. It’s also interesting for having been shot outdoors, with what looks like a flat gravel “floor.” The lighting changes dramatically at one point, with the sun in a different position after an obvious pause in filming, and for a time the shadow of a tree is visible in the right foreground. The set is also quite elaborate for such an early production. Watch for a moment when the actors bump into the set and cause it to wobble alarmingly.

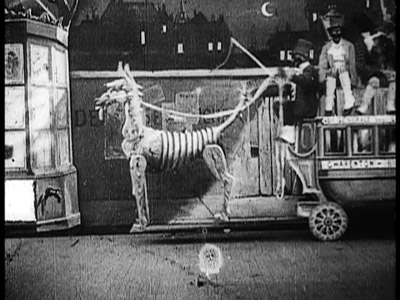

I had long been intrigued by production photos and sketches from a lost Méliès film, L’omnibus des toqués ou Blances et Noirs/Off to Bloomingdale Asylum. (I have no idea why this English title was chosen, since it has nothing to do with the action. “Toqués” would translate roughly as “crazies.”) The thing that intrigued me was a strange, mechanical-looking horse that draws the omnibus of the title. Finally I got to see it, and it was worth the wait. The horse is good, to be sure. It pulls a small coach with five black-face minstrels sitting atop it.

It’s not terribly apparent from the film, but a surviving Méliès sketch makes it obvious that the horse farts, driving the minstrels to jump off. The horse and coach depart, and the four minstrels begin an elaborate game of slapping and kicking each other in rhythm, each blow turning one into a white-clad pierrot figure and then back into a minstrel. It’s another of Méliès’ rapid-fire set of stop-motion substitutions, with the positions of the figures matched with astonishing precision. A tiny masterpiece in one minute and four seconds, counting the title card.

There’s a wide range of genres represented on the disc, including staging of news events, as in Éruption volcanique à la Martinique/ Eruption of Mount Pele (1902); chase films, like Le mariage de Victoire/ How Bridget’s Lover Escaped (1907); and even tear-jerking melodrama, like Détresse et charité/ The Christmas Angel (1904). The latter has an interesting stop-motion effect to add a white-painted stream of light as a rag-picker turns on his lantern to see the little beggar-girl asleep in the snow.

An otherwise surprisingly pedestrian 1905 film, L’ile de Calypso/ The Mysterious Island has one impressive moment, when a giant hand (Polyphemus having been transferred to Calypso’s island) emerges from the dark of a cave to threaten Ulysses (who is a bit hard to see, standing against the rocks at the right of the cave).

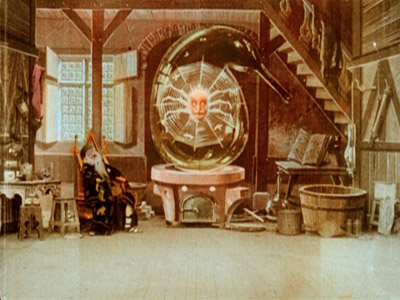

Was Méliès the first filmmaker to realize that leaving a large dark patch in part of set allowed things to be superimposed in that area without looking translucent? The best-known film to use the device is L’Homme à la tête en caoutchouc/ The Man with the Rubber Head (1902), but many other films use it, including some on this disc. A few of the films have hand-coloring, including the early L’hallucination de l’alchimiste/An Hallucinated Alchemist, where the alchemist of the title dreams of a giant spider.

The state of preservation naturally varies enormously. One nearly pristine print is the amusing Satan en prison/Satan in Prison (1907). The title is vital, since the bulk of the action consists of a well-dressed man magically producing a series of items to furnish a bare room, culminating in his summoning up a charming lady to share his meal. Hearing the guards approaching, the man reverses the process, ending with a bare room when the two men enter. Finally he is revealed as one of Méliès’ favorite characters, Satan! (See frame surmounting this entry.)

I suppose we shall never have all of Méliès’ films, but there are now more than twice as many known to survive as when I was in graduate school. I look forward to a second encore.

Lubitsch, Lubitsch, Lubitsch

Another pleasant surprise among the heap of packages was Eureka!’s new boxed set of Ernst Lubitsch films from the years 1918-1921. If that sounds a bit familiar, that’s because this is the third such set to appear in just over three years. I’m not going to make a point-by-point comparison, but I’ll sketch some basic differences.

The German set, confusingly titled in English the “Ernst Lubitsch Collection,” came out in November, 2006 and is PAL, region-2 encoded. It contains five Lubitsch silents: Ich mochte kein Mann sein (1918), Die Austernprinzessin (1919), Sumurun (1920), Anna Boleyn (1921), and Die Bergkatze (1921). Its main bonus is a feature-length documentary, Ernst Lubitsch in Berlin—Von der Schönhauser Allee nach Hollywood. None is subtitled. The set won the Cinema Ritrovato’s prize as Best DVD of 2008.

The set was issued by the Munich company Transit Film, a government-owned 35mm distributor with a library of about 600 titles, drawn from across the history of German cinema. We’ve brought some of their prints to Madison for Cinematheque screenings. The sources of the films are primarily the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Foundation and the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv. It also produces documentaries like the one on Lubitsch. (The website offers German, English, and French language options.) It has also put out several DVDs under the name “Transit Classics.”

In the U.S., from late 2006 into 2007, Kino Video brought these five titles out as four individual DVDs (pairing Die Austernprinzessin and Ich mochte kein Mann sein on one disc). Apparently, although Transit’s set didn’t include the 1919 comedy Die Puppe, it made it available, and in December 2007, Kino brought it out on a disc with the Ernst Lubitsch in Berlin documentary—and at the same time issued a boxed set of all six features plus the documentary on five DVDs, called “Lubitsch in Berlin.” (All Kino discs are NTSC region 1; given that they were transferred from PAL versions, they probably run about 4% faster than the Transit versions.)

Eureka!’s set is also entitled “Lubitsch in Berlin.” It contains the same set of films, including the documentary, all also licensed from Transit. These are here arranged over six DVDs. Its unique material is relatively slight, consisting mainly of short original sets of liner notes and an original score for Die Puppe. One advantage is that Eureka!, as usual, has retained the German intertitles and added subtitles to them. (The Kino versions, in contrast, replace the original intertitles with English ones, which has been their practice on some, if not all, of their other DVDs.) Some or all of these intertitles may have been replaced, perhaps reconstructed on the basis of censorship records, as is often the case with restorations. Still, many viewers would want access to the German text as well as the English versions. The Eureka! set is PAL, and it doesn’t seem to have region coding.

For those unfamiliar with Lubitsch’s German films, these are a good introduction. The four comedies all hold up well today. The first three are built around Ossi Oswalda, a boisterous blonde comic who seems to have inspired Lubitsch to move away from broad slapstick to a more stylized, eccentric approach. Pola Negri, after acting such roles as Carmen and Madame Dubarry in the director’s costume pictures, revealed her comic talents in Die Bergkatze, his last German comedy.

Overall my favorite of the group is Die Puppe, so I’m very glad it’s been added. Some might prefer Die Austernprinzessin, which is indeed hilarious. But it mainly has the wealthy heroine’s home as its comic milieu. Die Puppe seems denser, with more characters and three comedy-generating settings: the rich uncle’s home, the art-nouveau cartoon doll shop, and the monastery where the hero takes refuge. Plus there’s the famous prologue, where Lubitsch himself sets up the premise that the characters themselves are simply dolls brought to life. (See below.)

I chose Ich möchte kein Mann sein as one of the best films of 1918. See here for a brief description and a frame at the bottom of the entry.

The conspicuous absence from this set is Madame Dubarry, the 1919 historical epic that made Lubitsch famous worldwide. Perhaps it’s not an ingratiating film at first viewing, but I found that it grew on me in repeated screenings. (I talk about some of its best scenes including one impressive long-take scene, in my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood.) Anna Boleyn took on British history in an attempt to replicate the success of Madame Dubarry, but I have never been able to warm up to it. That’s probably partly because Henny Porten simply did not bring the vibrancy to the title role that Negri had in Madame Dubarry and perhaps partly because the increased budget let to an overemphasis on huge sets and crowds of extras (above). The characters in Madame Dubarry seem comfortable in their period costumes; the ones in Anna Boleyn don’t.

I chose Die Puppe as one of the best films of 1919. See here for a frame from it, and one that demonstrates why I admire Madame Dubarry. Perhaps restoration work on the latter is going on at this moment, so that another DVD will someday join these on the shelf.

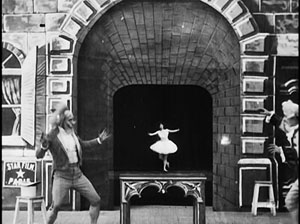

The other film in the collection, Sumurun, is a quasi-Arabian-Nights tale, starring Pola Negri as a seductive member of a traveling troupe of entertainers. Lubitsch plays his last film role as the hunchback clown who dotes hopelessly on her. The performance isn’t all that different from some of his earlier ones, but perhaps seeing his rather exaggerated acting style in the context of a non-comic film led Lubitsch to doubt his own abilities. Given that he was far better as a director than as an actor, his decision to stay behind the camera was a boon to future generations. To me, Sumurun is fascinating because it shows the first real signs of Lubitsch’s awareness of Hollywood continuity editing, a set of techniques he would thoroughly master over the course of his next half-dozen films.

It can’t have been easy to put together a 109-minute documentary on Lubitsch’s life before his move to Hollywood. In working on my book, I discovered how surprisingly few photographs of him at work onset survive. The studios where he worked don’t survive, though there are shots of the giant Ufa Tempelhof sound stages that now stand where those studios were.

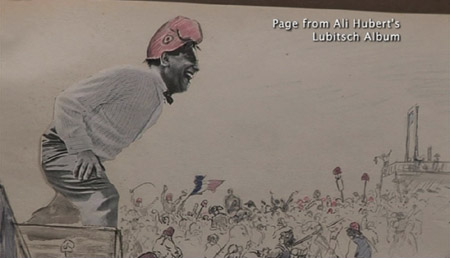

Several prominent historians are interviewed, including archivist Enno Patalas and historian Hans Helmut Prinzler, co-editors of Lubitsch (an extremely useful book, published by the Verlag C. J. Bucher i 1984) and archivist Jan-Christopher Horak (whose master’s thesis was on Lubitsch’s relation to Ufa). Lubitsch’s surviving family members, seen above at the unveiling of a “Lubitsch lived here” plaque, were interviewed: his niece Evy Bettelheim-Bentley (left), granddaughter Amanda Goodpaster (center), and daughter Nicola (right). Lubitsch’s theatrical career is well covered, and generous clips from the pre-1918 era demonstrate his move into comic acting for films. Audio interviews with Henny Porten and Emil Jannings include a charming anecdote she tells about how apologetic Jannings was after the scene in Kohlhiesels Töchter in which his character jerks a bench out from under her–an incident that left her with a bruised rump. In between scenes, directors who have been awarded the Ernst Lubitsch prize, such as Tom Tykwer, discuss the master. Perhaps the most interesting artifact shown is an album Lubitsch’s regular costume designer and friend Ali Hubert made for him, combining drawings with photos of Lubitsch and little poems; below he depicts Lubitsch directing Madame Dubarry. Ultimately Hubert gave it to the director as a gift.

The documentary feels a trifle thin at times, and it makes no real attempt to cover Lubitsch’s Hollywood career, presumably because of the difficulty of getting permission to use clips. But it certainly would be a useful teaching tool for introducing students to Lubitsch’s life before Hollywood.

(Thanks to Ben Brewster for helping determine some of the differences among these three Lubitsch boxes.)

The Man with a Movie Camera before The Man with a Movie Camera

In 2007, the Cinema Ritrovato awarded the “Edition Filmmuseum” series from the Filmmuseum Munchen its DVD award for “Best Series.” We’ve mentioned this series before, in relation to its Walter Ruttmann disc and its DVD of Robert Reinhert’s Nerven.

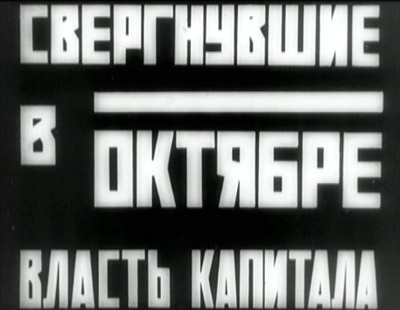

Now the Filmmuseum has issued a two-disc set offering two of Dziga Vertov’s silent feature documentaries, A Sixth Part of the World (1926) and The Eleventh Year (1928). The former is a poetic look at the various and farflung ethnic groups within the U.S.S.R., the population of which made up one sixth of the world. It was the first of Vertov’s films to be strongly praised, seeming to justify his theory of the Kino-Eye.

Those expecting anything as experimental as Man with a Movie Camera might be disappointed. There are some of the familiar camera tricks, such as split-screen effects:

The typography of the intertitles reflects the constructivist style of the 1920s:

The discs have optional English subtitles.

Having seen these films during my research, I haven’t watched the discs in their entirety. The quality looks as good as can be expected. Michael Nyman’s music is certainly not authentic to the period, but what I heard of it sounded strangely appropriate to the images and effective as accompaniment.

The discs also include an interesting bonus, a German propaganda short, Im Schatten der Maschine, by Albrecht Viktor Blum, which used footage from The Eleventh Year to make a film critical of the technical progress which Vertov was praising in his own movie. (Since The Eleventh Year had not yet appeared in Germany, Vertov was actually accused of plagiarizing from Blum rather than the other way round.)

Another bonus is a 14-minute documentary, Vertov in Blum: An Investigation (optional German or English narration). This fascinating short begins by demonstrating that Vertov himself and possibly others almost certainly cannibalized footage from The Eleventh Year for Man with a Movie Camera and other films. It goes on to hypothesize that the final montage in Im Schatten der Maschine may consist of footage that Vertov later removed from The Eleventh Year‘s negative. Side by side comparison of prints using Final Cut Pro revealed matching shots between the two films, highlighted in yellow here:

Blum’s film culls shots and even edited passages primarily from late in Vertov’s film, but it continues beyond the end of the surviving version of The Eleventh Year. Some of those shots have been traced to other, later Vertov films, and the archival sleuths are still comparing prints and looking for the rest. They may have found the missing ending from The Eleventh Year; at least, the evidence makes that idea very plausible. Whether they are right or not, though, the short demonstrates the painstaking work often necessary in the restoration of films.

These companies and archives have certainly not been resting on their laurels. It will be exciting to see what the upcoming Cinema Ritrovato’s awards will highlight.

Bugs: The secret history

DB here:

One of the many penalties of watching movies on TV is the prevalence of bugs.

This is the nickname adopted by media makers for those little channel logos and watermarks that hop onto your screen. Sometimes these translucent signatures surface at intervals, to minimally satisfy FCC channel identification demands. Others let you know the movie you’re watching, or will be later.

But just as often the bugs just squat in a corner forever, teasing your eye away from the movie. Bugs are to the 2000s what editing and time-compressing were to earlier eras. “Movies, uncut,” boasts the IFC bug. But not unspoiled.

Bugs are bad enough when they are hovering in a black vacuum, made forlorn by letterboxing.

But they really jump into competition when they take up part of the image. How can you watch what actors are doing when there’s something faintly readable floating up from below?

I find it impossible not to look at a bug occasionally. In dark shots, sometimes it’s the most visible thing on the screen. Even in bright shots I stare at it. Maybe I’m hoping that it will be different this time. Yet when it changes, as it does on the Lifetime channel, I watch it more attentively, which only makes me more annoyed.

It’s like the mesmeric spell of Time Code, ticking away the movie’s life, and yours.

I’m not the first to complain. An eloquent manifesto, originally called Squash the Bugs, dates back to 2000, when the infestation was starting. Several other souls participated in the movement.

We know why bugs are swarming all over TV. Somebody better dressed than you or me is worried that we will be recording A Christmas Story or Smokey and the Bandit or Stranger in My Bed. We might even try to sell copies, or post a clip online. In principle, the bug is a badge of ownership, warning that we could be prosecuted. In practice, nobody expects to sue every user, so bugs help spread the brand. It’s like putting a designer logo on a shirt, making you a walking ad. Who wouldn’t want their bug, microscopic as it is, all over YouTube (which of course tacks on its own bug)?

But like everything else that we take for granted, bugs aren’t new. In their earlier form, they’re rather likable.

Silent but deadly

Movie bugs go back to the first years of cinema, when producers were no less worried about media piracy than they are today. Between 1895 and 1915, films circulated very freely around the world, and enterprising crooks happily duped originals and passed them off as their own productions. To block this, filmmakers tried to find ways to keep their trademarks on the film.

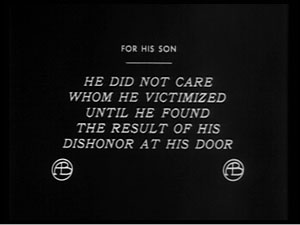

The obvious step was to put the trademark in the intertitles, and many companies did. Here is one for For His Son, a 1912 Griffith film from American Biograph. (What did the protagonist do for his son? He created a soft drink called Dopocoke, which turns the college boy into a hopeless addict.) Note the handsome AB insignia.

But of course a pirate could simply replace such original titles with ones of his own. The next logical step was to incorporate the trademark into the images, which couldn’t be replaced. Without the technology to create near-invisible superimpositions, the filmmakers took the obvious course.

They put the company logo into the set.

The AB circle typically appeared as a wall decoration. Biograph characters loved to furnish their surroundings to highlight this motif, preferring to put it at eye level and frame center. The logo could be found in unexpected places, like movie theatres (Those Awful Hats, 1908), and it could brighten the dreariest hovel (What Shall We Do with Our Old?, 1911).

The plaque’s popularity stretched back to Civil War days (In the Border States, 1910), and even in medieval times a king might mount the stylish AB on a brick wall (The Sealed Room, 1909).

Not to be outdone, Biograph’s competitor, the Vitagraph company, had a beautiful soaring eagle logo, which conveniently furnished a striking V graphic.

Judging from the evidence of this 1908 film, however, Vitagraph had a sideline in manufacturing safes.

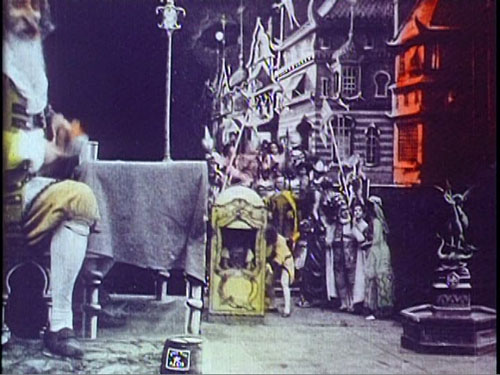

The practice of building the trademark into the mise-en-scene seems to have begun in France. Georges Méliès, whose fantasy films were popular around the world, took measures to counter piracy early. You can see his Star-Film logo on the building stone in the left corner of this frame from La Danseuse microscopique (1902). Shift it to the right corner and we’d have a modern-day bug.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

But Méliès didn’t always shove his imprimatur to the edge of the frame. In Le Tonnerre de Jupiter (1903) it sits just below the eagle that Zeus bestrides.

In the earlier Diable au convent (1899), Méliès exercised another option, simply signing his image as if it were a painting. To a large extent, it was.

Léon Gaumont had two marques, each enclosed in a chrysanthemum ring. The most famous one is a majestic Gaumont, but an alternative, ELGE (that is, LG), haunts Alice Guy’s Billet de banque (1907). First, in a café, the logo is attached to a table, and later it’s a decorative baseboard in a police station.

In Guy’s Le Frotteur (1907), Gaumont simiply stuck its logo to a chair leg.

Then there’s the Pathé Frères rooster.

Easy enough to embed that, you’d think. Just have a rooster stroll through a shot now and then—not only barnyard scenes, but ones set in a courtroom or a factory. Still, roosters are pretty accessible to any film pirate, so Pathé went the more ordinary route of weaving its logo into the set.

An insistent example comes in The Physician of the Castle (1907), possibly the source for Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1908) and Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s Suspense (1913). The plot is sort of a 1907 Panic Room. The logo is initially a plaque in the parlor of the castle, visible just behind the kneeling doctor.

An identical plaque is perched in nearly the same spot on the wall of the doctor’s own parlor, as we can tell when his family is besieged by the invading tramps.

The tramps pass through another room, where the trademark stands proudly on another wall, on screen right.

And when the wife tries to phone the husband for help, we get an insert that shows the Pathé cock nearly perched on her shoulder.

Why do I find the old bugs charming and the new ones annoying? I suppose it’s partly because the old ones were hand-crafted, not the result of keyboard twiddling. They are tangible. They are part of the scene’s space. Hard to see on DVD, the embedded marques are striking in 35mm projection, and spotting them is part of the pleasure of early film. Moreover, the filmmakers intended them to be there, or at least they accepted the need for them. But what director today is happy when the Sundance bug creeps into her compositions?

The old bugs seem to have gone extinct around 1912, but they will cling to their films. They bear witness to filmmaking of a specific time, and they anticipate problems that persist today. In tackling the threat of piracy, the old bugs seem at once naïve and intelligent. I see them as a rational solution to a hard problem, narrative consistency be damned. Today’s bugs, floating on top of the story world, seem more like corporate tattoos or graffiti. They don’t exist within the action, so you could argue that they are less disruptive. But they become a different sort of distraction, hovering halfway between the story world and the space of viewing. Bugs are spectres haunting the film.

On rare occasions, a modern add-on can be appropriate. In a Méliès film on the recent Flicker Alley set, L’Oracle de Delphes (1903), some TV agency has clapped its own digital bug into the lower right corner. It really is about beetle-size, and it dares to be a single eye looking back at you. That icon adds a touch of peculiarity not out of keeping with the Méliès aesthetic.

You can argue that this smirch on the image is a minor sacrilege. But I suspect that the Master of Montreuil would have grinned in approval.

For more on bugs, aka DOGS (Digital Onscreen Graphics), see Wikipedia. Thanks to Jason Mittell for helping me name these pests. And all hail Turner Classic Movies for keeping its bugs to a minimum.

The Sunbeam (Griffith, American Biograph, 1912).

PS 19 January 2009: “Subliminal” bugs: I had hoped to include a frame illustrating the anti-piracy stamp used on current 35mm releases, but couldn’t find one quickly. This mark consists of a tight pattern of dots resembling a character in Braille. The stamp would presumably be copied if someone shot off the screen or ran the film through a telecine. How effective these bugs are at tracing pirate copies I can’t say, but you can detect them, especially in bright scenes; I usually notice one every third reel or so, just left of the center of the frame. I’ll keep looking for a frame and try to add one to this entry.

John Powers alerted me to the fact that even Michael Snow’s Région Centrale got the bug treatment when it was telecast on Italy’s RAI 3 TV. Thanks to John for this scary example.

P.P.S. 24 January 2009: On the Internets, ask and ye shall receive. Olli Sulopuisto wrote to link me to the Wikipedia entry explaining the domino dots, known as CAPs. The entry includes an illustration. Olli also contributed to Jim Emerson‘s scanners blog, which contains good commentary on CAPs from Jim and his readers.

P.P.P.S. 29 May 2013: Can anti-piracy bugs be integrated into the movie or TV show? Yes!