Archive for August 2014

Zip, zero, Zeitgeist

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014).

DB here:

The silly season always seems to catch me off guard. This time I got the word in a New York Times feature, “The Moviegoers.”

Here two writers, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, conduct an email conversation about recent films. You may have thought that the Times already has a large stable of movie reviewers, headlined by Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott. But mainstream movies are very accessible (as opposed to, say, serial music or Baroque architecture), so nearly everybody has something to say. And because nobody knows what counts as expertise in movie reviewing, why not bring on two of the commentariat? Once you become a public intellectual, what you say about anything is interesting.

Granted, both participants in the dialogue, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, have been movie reviewers. Mr. Bruni wrote for the Detroit Free Press, and Mr. Douthat currently covers film for the National Review. Through some process yet unexplained, these movie reviewers became second-string social and political pundits for the Times. That would seem a step up, so why put them back in the reviewing game?

The rationale is supplied in the series introduction, which talks of the plan to discuss “movies, pop culture, television, and other real-world distractions.” The Times style guardian might want to pause on the last phrase: Are these phenomena distractions in the real world (as in “real-world opportunities”)? Or are they distractions from the real world? I think the writer means the latter, which translates into this: Politics is the important stuff, mass art is a lightweight diversion. And we all need diversion, especially a newspaper aiming to attract readers under fifty.

So we have two Op-Ed columnists taking a break from serious matters in order to shoot the breeze about summer releases. In “Two Thumbs Up…Yer Arse.” Charlie Pierce, our fouler-mouthed Mencken, has exposed some curious assumptions about poverty displayed in the Moviegoers’ first round of chitchat. What interests me here is another aspect of the column, which showcases one standard move that many reviewers make.

The problem for serious people like Mr. Douthat and Mr. Bruni is this. If movies are “real-world distractions,” why spend any time talking about them? More specifically, why should political pundits talk about them? The obvious answer: Somehow these products of popular culture open a window into what’s really going on. Mr. Douthat:

In this sense I do think moviemakers are tapping into the American psyche, but I also think they’re replicating a flaw of the American political debate. I’m not sure we’ll get very far by painting the rich as morally hopeless people who must be subverted, vanquished, overtaken.

And when Mr. Bruni asks, “Tell me about the trend that made you happy, and (speaking of political allegories) whether you like ‘Apes’ as much as everyone else,” Mr. Douthat replies:

There was something poignant about watching “Apes” against the backdrop of the mess in the Middle East and of the war in Israel and Gaza, because it’s a disturbingly good allegory of reciprocal mistrust, asking the right questions about how peace ever reigns when combatants can’t bring themselves to forgive error, to take the first step, to turn from the past and focus on the future, to start afresh. It’s a disturbingly good allegory about corrupt leaders, too: how they whip up fervor in the service of their own ambition; how we rise and fall based on the clarity and wisdom with which we choose them.

You may want to reply that if this is what the Times wants, you will undertake to supply them with 3000 words of it every day at reasonable rates. But put aside the banalities about politics. I’m interested in the suggestion that movies can bear traces of the national psyche, or reflect national debates we’re having right now, or provide inadvertent “allegories” of contemporary history.

These ideas enjoy an astonishing popularity. They are staples of movie journalism. The trouble is that they don’t hold up.

Reflections on reflectionism

That mass entertainment somehow reflects its society is, I believe, the One Big Idea that every intellectual has about popular culture. The notion shapes the Sunday Times think piece about how the movies of the last few months capture the current Zeitgeist (or one a while back). It informs the belief that we can define periods in American popular art by presidential eras–Leave It to Beaver as cozy Eisenhower suburban fantasy, Forrest Gump as an expression of Clinton-era post-Cold-War isolationism. Reflectionism may be the last refuge of journalists writing to deadline, but it’s also found in the industry’s talk about itself. “Oscar Best Pic Contenders Reflect America’s Anxieties,” Variety announced last winter.

The threat of circularity. Behind this Big Idea is an assumption that cinema, being a “popular art,” tends to embody some state of mind common to the millions of people living in a society. The very idea of a massive mind-meld like this seems implausible. America’s anxieties and our national psyche? The anxieties of the 1% are not yours and mine, and I doubt that even you and I share a psyche.

The argument easily becomes circular. All popular films reflect society’s attitudes. How do we know what the attitudes are? Just look at the films! We need independent and pretty broadly based evidence to show that the attitudes exist, are very widespread, and have been incorporated in films. And it won’t do to simply point to the same attitudes surfacing in TV, pop songs, mass-market fiction as well, because that just postpones the problem of correlating the attitudes with groups of living and breathing people.

Critics seem to assume that if a film is successful at the box office, it must reflect the audience’s inner life. Yet the sheer fact of a movie’s popularity doesn’t prove that these attitudes are out there. Just because Spider-Man (2002) was a huge success doesn’t mean that it offers us access to America’s national mood or hidden anxieties. People spend time with a piece of mass art for many reasons: to kill an idle hour, to meet with friends, to find out what all the fuss is about. After the encounter, consumers often dislike the art work to some degree, or they remain indifferent to it. Since people must buy the movie ticket before they experience the movie, there can’t be a simple correlation between mass sales and mass mood. You and lots of others may be suckered into going to a film you dislike, but just by going you’ve already been counted as among those who support it. Doubtless many people enjoyed Spider-Man. But it’s very difficult to say how many.

And did all of the patrons who enjoyed it do so for the same reasons? That remains to be shown, and it’s hard. We know that a movie may appeal to several audiences at once, packaging a range of appeals. In fact, it’s a strategy of the film industry to produce movies that contain fuzzy messages, contrary attitudes, and something for nearly everybody. Must we find reflections of cultural needs in every aspect of a movie that might appeal to somebody?

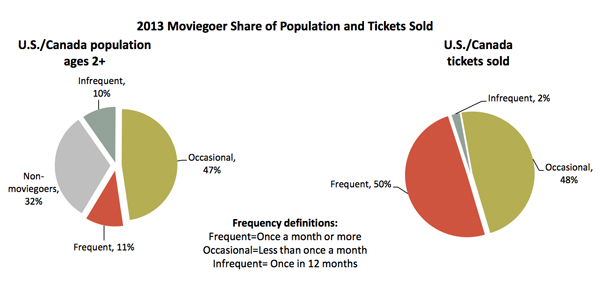

Movies are narrowcasting. The film audience is a skewed sampling of the population. According to industry statistics, about one-third of Americans over the age of two never go to the movies, and another ten percent go once a year.

Another 40% go “occasionally”–less than once a month. It turns out that the heavy moviegoers, those going once a month or more, are currently just 11% of the population. Take Dawn of Planet of the Apes. Assuming an average ticket price of $8 and no repeat viewings, at most about 25.5 million Americans and Canadians have seen the movie. That’s about 7% of the countries’ total population. We would need to tell a pretty full story about how the mental life of 350 or so million people gets into movies seen by a thin, self-selected slice of the population.

Moviegoers are atypical of the population in other respects. Since the beginning, Hollywood cinema has catered to the middle class. Moviegoers have been younger, better educated, and better-off economically than non-moviegoers.

The real mass medium of our time is network television (as radio was before). On one night, a single episode of The Big Bang Theory can attract 19 million viewers. A film that had that viewership across an opening weekend would take in over $150 million. That is $50 million more than the latest Transformers movie garnered at its debut. If Messrs. Douthat and Bruni want to take the national temperature, they should watch TV–ideally, the ads on the Super Bowl (shown to 112 million viewers).

Actually, you can argue that television really is a more reliable barometer of mass tastes, not just because of its prevalence but because TV viewing depends on recidivism. People may not know they’ll like a movie before they attend, but they tune in to shows that have proven to satisfy them. Still and all, mass taste is not the national psyche.

The long road from the White House. A primary prop for reflectionists is politics. Talk about an American film of the 1950s and sooner or later someone will invoke the reign of blandness that was (purportedly) the Eisenhower administration. But why do we assume that the population’s mind set switches its course whenever a new President is elected? Many voters stubbornly adhere to the same values election after election; others vote in order to throw out a rascal and aren’t at all satisfied with the newcomer.

There couldn’t be a direct tie between elections and moviegoers’ attitudes. About thirty percent of today’s audience consists of people too young to vote. The most reliable voter turnout is among the over-forty-five set, which until recently constituted only about twenty percent of moviegoers. Of course, maybe movies reflect the attitudes of non-voters, or people who are indifferent to politics. But then why identify periods of political history with periods of movie history?

Reflectionists have always been reluctant to offer a concrete causal account of how widely-held attitudes or anxieties within an audience could find their way into art works. What precise story could we tell to explain how changing the occupant of the White House can affect popular culture? How exactly does a party platform or a candidate’s charisma or the new administration’s policies seep into Hollywood movies for the multitudes?

Movies’ crystal ball. If there ever were a dominant mood at large in the land, it would be very difficult for that mood to find its way into a current movie. There’s often a lag of several years before a script gets to the screen. Many of the films released in 1997, though read as responding to current crises, were bought as projects in 1993 and 1994. Dawn of Planet of the Apes was begun in 2011, written through 2011-2012, and began shooting in April of 2013–all before the current standoff between Israel and Hamas.

Maybe the moviemakers are somehow in touch with political forces before they crystallize? One critic has proposed that films can have this prophetic power. Puzzled that no Obama-era movies had emerged by 2012, J. Hoberman suggests that the most “Obama-ite” ones came out before Obama was elected:

The longing for Obama (or an Obama) can be found in two prescient 2008 movies—WALL-E (the world saved by an endearing little dingbot, community organizer for an extinct community) and Milk (portrait of another creative community organizer—not to mention a precedent-shattering politician who, it’s very often reiterated, presented himself as a Messenger of Hope).

This is nearly a miracle. Somehow these filmmakers sensed that Americans (well, 53% of the people voting) were yearning to be led by a community organizer. But how specifically could the filmmakers have arrived at that prescience? In fact, they would have had to be long-range prophets. Milk began as a 1992 project, and the final version of the script was prepared in 2007. The Pixar adepts started talking about WALL-E in 1994 and began drafting scripts in 2002. Why don’t we ask filmmakers to predict our next president right now?

Pick and choose. Of all the films of the summer, Bruni and Douthat settle on a few. Of all the hundreds of 2008 films, two presage Obama. This selectivity is typical of the reflectionist approach, which typically ignores the range of incompatible material on offer.

If 1940s film noir reflects some angst in the American psyche, how to explain the audience’s embrace of sunny MGM musicals and lightweight comedies in the same years? The year 1956 saw the release of The Ten Commandments, Around the World in 80 Days, Giant, The King and I, Guys and Dolls, Picnic, War and Peace, Moby Dick, The Searchers, and The Lieutenant Wore Skirts. Pick one, find some thematic concerns there that resonate with social life of the time, and you have a case for any state you wish to ascribe to the collective psyche. But take any other movie, or indeed the industry’s entire output, and you have a problem. One alternative is for us to find that the films share common themes, but these are likely to be of an insipid generality. Or we could float the rather uncompelling claim that several hundred films reflect hundreds of different, and contradictory, facets of the audience’s inner life.

Consider the source. Of course filmmakers sometimes deliberately include political comment. But then the film is “reflecting” the purposes of its particular makers, not the mass public. The filmmaker may claim to be tapping the Zeitgeist, but it’s really the Zeitgeist as she or he understands it. It’s not the public expressing itself spontaneously and unselfconsiously through the movie.

Movies use a lot of collaborators, and they may have varying agendas. The most powerful players are inevitably going to shape the initial project in specific, often personal ways. The preoccupations of the screenwriter, the producer, the director, and the stars necessarily transform the given idea. And these workers, living hermetic lives in Beverly Hills and jetting off to Majorca, are far from typical. How can the fears and yearnings of the masses be adequately “reflected” once these elites have finished with the product? Maybe some violence in American films gets there not because the crowd secretly wants it but because Hollywood creators compete in pushing the envelope. Once more we need a story about how widespread opinions get incarnated in the work of an unrepresentative group.

In sum, reflectionist criticism throws out loose and intuitive connections between film and society without offering concrete explanations that can be argued explicitly. It relies on spurious and far-fetched correlations between films and social or political events. It neglects damaging counterexamples. It assumes that popular culture is the audience talking to itself, without interference or distortion from the makers and the social institutions they inhabit. And the causal forces invoked–a spirit of the time, a national mood, collective anxieties–may exist only as abstractions that the commentator, pressed to fill column inches, invokes in the manner of calling spirits from the deep.

Primate see, primate do

This isn’t to say that society has no impact on films. Of course it does. But we understand that process best by taking film as film.

Film critics serve us best when they explore how a film uses the medium to yield its effects. Critics can enlighten us about how filmmakers work with their givens (subjects, themes, genres, artistic traditions, star personas) and generate an experience shot through with meanings, feelings, and ideas. We should recognize that a large part of any movie is the result of will and skill, not the passive reflection of vague social turmoil. There will be some unintended effects too, of course, but we can try to understand those as coming from specific conditions of production practices, traditions, and creative options.

One first step, for example, would be to consider Dawn of the Planet of the Apes as following the plot pattern of the revisionist Western.(Spoilers follow.) The humans, like settlers in the west, need resources held by the apes, who live in self-sufficient harmony with nature. They wish others no harm. A well-meaning emissary from the humans, Malcolm, leads a team into ape territory to tap an energy source. Thanks to Malcolm’s promises of peaceful coexistence, humans and apes become friendly. But other members of Malcolm’s team don’t trust the apes and provoke violence. There is also the brooding ape Koba, who wants revenge for his mistreatment in experiments. The peace treaty is broken by both sides.

Koba, Caesar’s friend and rival, escalates the war with the humans when he discovers the cache of weapons. While Caesar tries to keep Koba from fomenting rebellion, Malcolm must try to restrain the humans’ leader, Dreyfuss. This is a familiar duality: the unruly tribal brave hot for vengeance who must be disciplined by the wise chief, and the sensible lieutenant who tries to restrain his rapacious superior.

The science-fiction premise has been shaped to fit the familiar pattern of liberal Westerns, in which blame can be placed on weak, cowardly, vengeful, or power-hungry individuals who block well-meaning leaders from finding peace. The classic equivocation of Hollywood film (there’s always an element that says, “Yes, but then there’s…”) is well summed up by the ambivalent to-camera glare of Caesar that begins and ends the movie: Angry? Sorrowful? Defiant? Implacable? Your mileage may vary.

The political themes are sculpted in another way, through family parallels. Caesar has a wife, Cornelia, and a son, Blue Eyes. Malcolm has a wife, Ellie, and a son, Alexander. The prospect of peaceful coexistence between human and ape is encapsulated in the two families’ growing fondness for each other. The parallels are sharpened by contrasts. Alexander comes to accept the apes, while his more rebellious adolescent counterpart Blue Eyes temporarily aligns himself with the false father Koba—only to prove himself loyal to Caesar at the climax.

By contrast, Dreyfus and Koba are lone males, without women or offspring. Granted, we are allowed some sympathy for both: Koba has been mistreated by humans, and Dreyfus has lost his family in the collapse of civilization. Still, Caesar is morally superior to both because he has lived in each world harmoniously. Before the final battle, the wounded Caesar gets to recall his first human family, typified by his father figure, on video.

Onto the settlers vs. Indians plot, then, is grafted what film scholars have called a “family adventure” pattern, one that became prominent in the 1980s and 1990s with E. T.: The Extraterrestrial, Jurassic Park and other films seeking “four-quadrant” success. The result is more made-in-Hollywood archetype than grassroots allegory.

My sketch is Film Studies 101 and needs plenty of nuancing. To go further we should consider how this movie, or any movie, puts flesh on its plot bones. How does the film handle point-of-view and exposition? How does it generate sympathy or antipathy? How does it create character conflicts both external and internal? Does it accord with the sharply contoured plot architecture characteristic of US studio filmmaking (and maybe popular literature too)? If I were trying to do a finer-grained analysis of Dawn, I’d try to understand how the Western and family-adventure templates intertwine with these factors and gain force as the film unfolds.

The point would be not to suggest that these plot patterns reflect the attitudes or anxieties of the audience, let alone a national psyche. Rather, the patterns are chosen by the filmmakers because they have proven emotionally appealing to at least some viewers (and apparently in cultures outside the US). And they can be fashioned to accord with contemporary norms of moviemaking. Instead of passive reflection, we have active creation.

It isn’t all controlled by the filmmakers. Like all actions, filmmaking can have unintended consequences. If some members of the audience respond in the way the filmmakers wanted, so far, so good. If the results are grasped in ways that the makers didn’t expect or prefer, that comes with the territory too. Mass-market filmmakers take inherited forms and tweak them in new ways. The audience, in its turn, appropriates what it’s given, sometimes in predictable ways, sometimes in unpredictable ones. No national psyche is needed for this process to keep rolling.

Instead of reflection, better to think of refraction, the bending and reconfiguring of social themes under the pressure of filmmaking traditions. We understand mass-market films better when we see them as, sometimes opportunistically, grabbing material from the wider culture (whether that material reflects mass sentiment or not) and transforming it through narrative and stylistic conventions. That transformation, or rather transmutation, is central to the artistry of popular entertainment.

Movies are worth studying for themselves, not just as channels for Op-Ed memes. Critics who are sensitive to the art, craft, history, and business of cinema will be able to enlighten us about all aspects of a film, including its political ones.

Jeff Smith’s new book, Film Criticism, The Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds examines how critics of the 1950s found allegories of resistance to HUAC in movies made at the time. It’s a good reminder that this sort of reflectionist criticism goes back pretty far.

In tune with Jeff’s argument, in an earlier entry I argued that reflectionist readings of popular cinema intensified during the 1940s. But our best critics pushed back. Parker Tyler proposed that movies don’t so much reflect social myths as they invent their own, and he suggested that the process follows the zany logic of dreams. Otis Ferguson, James Agee, and Manny Farber mostly avoided Zeitgeist explanations and talked about films’ implications in relationship to art, craft, and other media and artforms. I survey their work in a series of recent entries: on Ferguson, on Agee, on Farber (here and here), on Tyler, and on their originality, their cultural context, and their legacy.

The pie chart come from the MPAA report on 2013 moviegoing, p. 11.

For a wide-ranging and skeptical examination of one aspect of this topic, there’s Alan Hunt’s article, “Anxiety and social explanation: Some anxieties about anxiety,” Journal of Social History 32, 3 (Spring 1999), 509-528.

Peter Krämer developed the concept of the family adventure film in contemporary Hollywood. See his “Would You Take Your Child to See This Film? The Cultural and Social Work of the Family Adventure Movie,” in Steve Neale, ed. Contemporary Hollywood Cinema (Routlege, 1998), 294-311.

If there’s an allegory in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, perhaps it’s a Bolshevik one. Josef Stalin was known as Koba, which would make Caesar a Lenin figure and Rocket a stand-in for Trotsky. (I doubt that the conservative Mr. Douthat would welcome this reading.) If the reference is intentional, it provides a good example of how a Hollywood film simply seizes cultural flotsam willy-nilly, perhaps to give intellectuals something to ponder. As Christopher Nolan explains of his Batman trilogy: “We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks.”

Parts of today’s sermonette are pulled from an essay published in Poetics of Cinema in 2008. That essay also charts areas of control that filmmakers and audiences enjoy. Another entry on this site dealt with these questions in relation to The Dark Knight and, again, the good, grey Times.

Daumier: Types Parisiens (1840-1843): “Ah, I can see my street, there’s my house, there’s my garden and my wife, I can see Laurent – Oh, I have seen too much.”

The AMBERSONS Poster Mystery: The clincher

DB here:

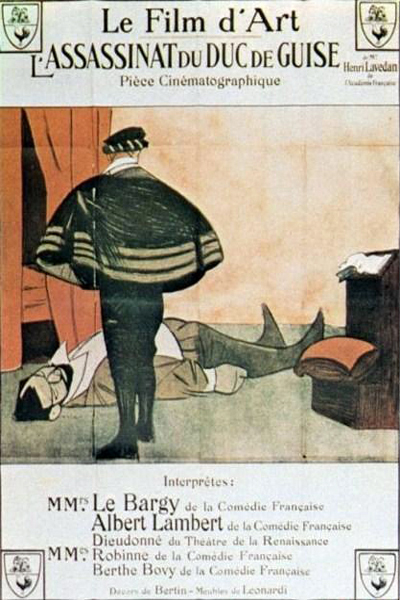

Bingo! Crowdsourcing pays off. Alert blogger Ivan Paio found the original poster that’s tucked into the Magnificent Ambersons frame! It confirms that Welles used not a film poster but one advertising a stage show…that could have played the Bijou in 1912.

If you’re not familiar with our quest, you can go here and here and here. Be sure to visit Ivan’s site for details, and give him a big hand.

Breaking AMBERSONS news: Did you say Buried?

DB here, again and still:

Still, until somebody comes along with a better account, I’m ready to believe that we’ve found the film.

That’s me, just two days ago. I suggested that the mystery poster tucked into the corner of one shot in The Magnificent Ambersons is the Pathé release of 1912, The Cow-Boy Girls. Readers with long memories and no life of their own will recall that this question has bugged me since my earlier post in May. Last week my colleague Eric Hoyt suggested what the title might be, and some rummaging in various sources, particularly the invaluable Lantern database, seemed to confirm it.

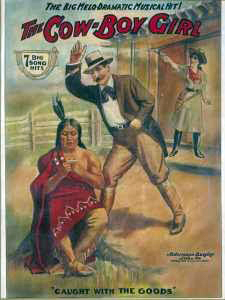

To recap: Here are two blow-ups from a 35mm print, showing the two angles from which Welles’ camera captures the poster. The text is clearer in the half-size one, but the more distant one yields a fuller view. The poster seems to depict a man thrashing an American Indian, with a young woman, arm outstretched, in the rear. Note also the shield-like triangular shape underneath the title on the first image.

Last night came word from two more vigilant correspondents, each with new evidence–again, unearthed by the light of Lantern.

My first correspondent was Luke McKernan, early film specialist and master builder of the vastly informative website The Bioscope. Luke has stopped posting there, but he continues to write keenly on cinema at lukemckernan.com. His message to me runs as follows:

Dear David,

I have struggled and struggled with this one til I’m at the point of worrying about my eyesight. I don’t think it can be The Cowboy Girls, but searching for the keyword Cowgirl might be productive. I found this in the Lantern site, searching for ‘cowgirl’ and 1912:

http://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/movingpicturenew05unse_0122

It’s not the right film, but the still is quite close to that in the Ambersons poster, which at least gives encouragement.

Luke

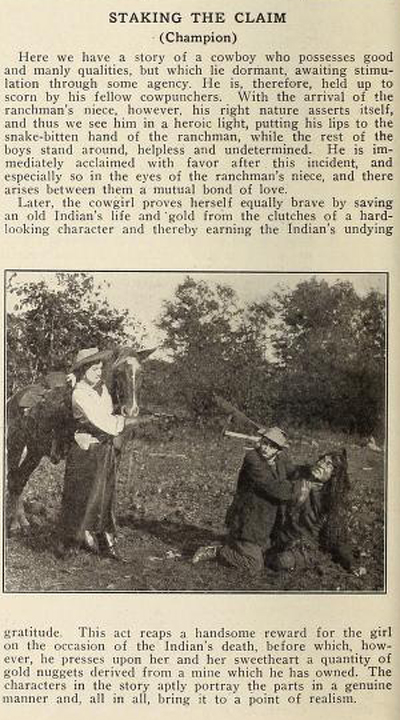

The entry Luke refers to is this one, from The Moving Picture News of 1912.

The picture shows the situation we find in the Ambersons poster. But as Luke says, our poster’s title clearly is not Staking the Claim. More research, as we academics say, is needed.

Just a few hours later came this from another colleague here at Madison, Ph.D. candidate Eric Dienstfrey.

Hi David,

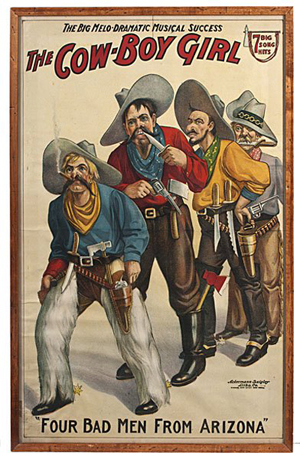

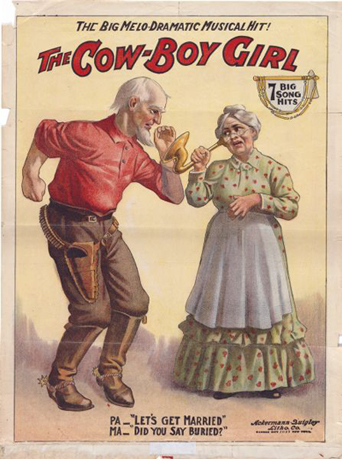

Reading your post on Ambersons now, I remember coming across the title The Cow-Boy Girl while researching stage musicals that were contemporary to Gottschalk’s The Tik-Tok Man From Oz and The Patchwork Girl of Oz. You are absolutely correct, the poster does say “The Cow-Boy Girl” but it was for a theatrical musical, not a film… at least I don’t think so. (But many films were probably called Cowboy Girl too.) I’ve attached two different posters from the musical that I found online. The triangle shield is not the Pathé rooster after all!

I hope you find this interesting/useful… or better yet, I hope this brings you a little closure.

Cheers,

Eric

I had mentioned on Saturday that there was a stage show called The Cow-Boy Girl, and I wondered whether the poster was promoting not a film but the theatre piece. In the end, I went with a film title. But Eric D’s visual evidence of the title font and the triangular motif (not a shield but a swag curtain, I think) strongly suggests that we’re dealing with a play. It would be characteristic of a theatre in 1912 to include vaudeville, stage shows, and other live entertainment alongside movies.

The Cow Boy Girl (no hyphen), a thirty-minute playlet including songs, was reviewed, unfavorably, by Variety (29 October 1910). The review doesn’t mention a scene like that depicted on the poster.

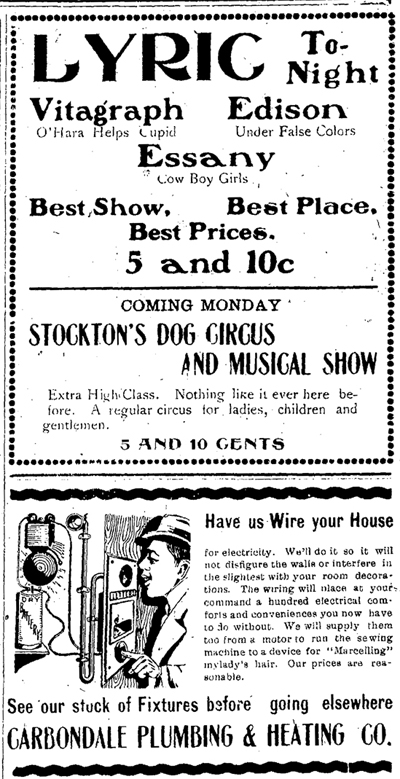

Other sources lists touring shows of The Cow-Boy Girl (with and without hyphen) from 1910 onward, so it might well have been playing the Bijou in the Ambersons’ town in 1912. Actually, Eric D. has found that it did play another Bijou. The Billboard of 18 February 1911 lists the following:

How can you argue with something that played the home of thrillers?

Are we there yet? Until we find a copy of the poster itself, I’m inclined to think so. But as Luke’s discovery indicates, we’re dealing with a period in which imagery, titles, and situations were copied and circulated in great profusion. In 1912 plenty of cowgirls and cowboys and cowboy girls and cow-boy girls were swarming over American entertainment. More or less like superheroes today.

No research project is finished, only abandoned. Thanks to the Fussbudget Team for playing!

The Fussbudget Report: An AMBERSONS solution

DB here:

Some readers may recall my post on The Magnificent Ambersons back in May. I argued that Welles built a sense of the irretrievable past into many aspects of the film’s narration. He used the voice-over commentary to evoke times gone by, but also ellipsis, offscreen action, constant recitation of memories, and other strategies. In addition, there were moments of cinephile nostalgia, including the iris shot at the end of the snow scene and the concluding credits of the actors slowly turning to face the audience, as in the manner of films of the 1910s.

Then there were the movie posters. George and Lucy are walking through the town. He’s about to leave for Europe, and she feigns a polite lack of concern. They pass the Bijou movie house, which flaunts several posters. I managed to identify all but one, the one tucked in the lower right of the frame above. I just couldn’t properly read the title, even on a good 35mm print.

Blown up from 35, the clearest view we get of it looks like this.

I thought it might be The Coin-Box Girl, but no such film title existed. Some readers– Jacopo Pes, Ivo Blom, and Paolo Cherchi Usai (thanks to all)–proposed some possibilities. Alas, none of their suggestions seemed to fit. Even running through the Library of Congress copyright listings for films didn’t yield a plausible candidate.

Over a lunch with colleague Eric Hoyt last week (Eric is one of the geniuses behind Lantern), we talked about this. Eric had access to a bigger list of titles than that of the LoC, and he suggested that the first words might be cow-boy. Checking his list, we find that there was indeed a May 1912 Pathé release called The Cowboy Girls. It’s also listed in Lauritzen and Lundquist’s American Film-Index 1908-1915 under that name. It might well have been postered as The Cow-Boy Girls. (We now assume that the squiggly line after “Cow” is a hyphen. It might be just a really curly w.) An April 1913 ad from the Carbondale Daily Free Press lists a film called The Cow Boy Girls, so if it’s the same movie, there was some freedom of punctuation around it.

I left the second ad underneath so you can appreciate having electricity.

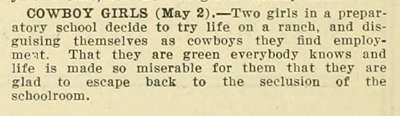

It would be very nice to check a poster of the film, but I haven’t found one. Here, though, is a synopsis from Moving Picture World of 1912. (Again, thanks to Lantern.)

This doesn’t quite match the image on the poster, which shows a man apparently about to strike a Native American kneeling before him. But in the background, more visible in the half-framed poster, there seems to be a young woman coming out of a cabin protesting, and perhaps brandishing a pistol. (Open Carry applies here.)

There are other anomalies. If this is indeed The Cowboy Girls from Pathé, does the triangular shield logo in the northwest corner boast a rooster? Some Pathé titles did, as for this 1908 French release (one of the most important films ever made). On the four shields, the rooster (also to be seen as decor in Pathé interiors) is joined by the eternal symbol of the theatre, the comic and tragic masks.

And if The Cowboy Girls is a Pathé title, did the Carbondale ad list it as “Essany” (Essanay) by mistake? Or is that a different cowgirls movie? It may be relevant that there was a vaudeville play called The Cow Boy Girl, which was touring at the same period. Filmmakers may have tried to cash in on that. Or maybe the Ambersons Bijou was presenting that stage show rather than a film?

Still, until somebody comes along with a better account, I’m ready to believe that we’ve found the film. The clincher for me is the Cowboy Girls’ date: 1912. Except for the fake lobby card promoting a nonexistent Jack Holt movie, all the discernible film posters in the Ambersons scene are from 1912 releases.

This obsessive synchronization is surely the work of a film nerd, either Welles or a staff member. Geek calls out to geek, from 1912 to 1942 to 2014. See? I’m not the only fussbudget here.

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).