Archive for the 'Directors: Wyler' Category

Problems, problems: Wyler’s workaround

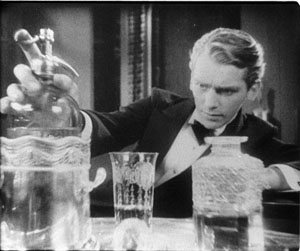

The Little Foxes (1941).

DB here:

For me, shooting is a struggle where you only get to be happy for five minutes before you start thinking about the next problem to solve.

Ruben Ostlund, on Force Majeure

One of the most famous shots in American cinema occurs at a climactic moment in The Little Foxes (1941). Regina Giddens has just learned that her sickly husband Horace has let her brothers get away with a business deal that double-crosses her. They will reap all the rewards of bringing a factory to town, while she, who engineered the deal and expected Horace to fall in line, will get nothing. Horace is already not far from death, and their quarrel in the parlor precipitates a heart attack. He spills his bottle of medicine and needs some from his upstairs supply.

Regina refuses to go fetch it, and instead Horace must stagger up and out. While she sits, fiercely waiting, on the sofa, he tries to pull himself upstairs, but he collapses on the steps. Once he has fallen, and perhaps died, she stirs to action and rouses the household.

Lillian Hellman’s original play had been a Broadway success, and this was one of the most notable scenes. How did Wyler stage it? Very oddly, as the frame up top suggests. We can’t really see Horace’s struggle on the stair. Not only does the camera put Regina in the foreground, but Horace is out of focus in the rear, at least until she rises whirling and runs to the background, the damage done.

Why did Wyler stage it this way? It depends, as Bill Clinton might say, on what your definition of why is.

Deeper, closer

1941 was the breakout year of deep-focus filmmaking in Hollywood. Citizen Kane, The Maltese Falcon, Kings Row, Ball of Fire, I Wake Up Screaming, How Green Was My Valley, and several other films set the pace for a new stylistic option. In this style, the action is staged in depth rather than perpendicular to the camera, as most scenes in Hollywood cinema were. And the camera lens creates depth of field, in which even fairly close foreground planes are just as sharp as the action in the rear. Such images weren’t unknown before; we can find them in silent cinema. But from 1941 on, depth staging accompanied by depth of focus would be increasingly common in Hollywood dramas, from thrillers and melodramas to film-noir exercises. Not all shots would be designed for maximal depth; continuity editing and closer views would still be used. But we do find such imagery becoming more common, particularly at moments of tension.

Cinematographer Gregg Toland is usually cited as a main source of this trend, and his work on Kane and Ball of Fire, as well as Ford’s Grapes of Wrath (1940) and The Long Voyage Home (1940), became models of the new look. Toland also worked with Wyler on several films, including The Little Foxes. But even without Toland, Wyler had in some films cultivated a deep-focus look (as had Ford). Coming when it did, The Little Foxes proved a powerful demonstration of the deep-focus style.

Three aspects stand out. First, there’s a certain economy of presentation. As Wyler and others pointed out, depth imagery permits directors to minimize editing. Instead of cutting from action to reaction, we see both at the same time.

Wyler suggested in publicity of the period that this gave the viewer more freedom of where to look, and André Bazin seized upon this rationale as part of his aesthetic of realism. Just as in the real world, in some films we must choose what to pay attention to.

But The Little Foxes went beyond the moderate deep focus of Stagecoach and other films to create very aggressive images. This is the film’s second novelty. Several shots place the foreground very close to the camera. As a result, we get looming faces or objects in the front plane, and we still see well-focused dramatic elements behind.

A third source of power is less noted. In The Little Foxes, Wyler found ways to make deep shots comment upon the plot. For instance, the action offers Regina’s daughter Alexandra, usually called Zan, a choice of being more like her mother (tough and vicious) or her father (tolerant and gentle). At other points Zan is paralleled to her ineffectual, alcoholic aunt Birdie. At one point, Birdie has predicted that Zan may wind up like her.

In a theatre production, there would be many staging strategies that would create these parallels, but Wyler uses a particularly striking one. One evening, while Regina and her brothers plot their scheme, Birdie has been relegated to a chair far from the discussion.

The composition diagrams Birdie’s situation in the scene and her place in the family. Then Wyler cuts in to her.

This might be seen as a bit of heavy-handed emphasis, but actually he’s doing two things. He’s making manifest her reaction, a numb resignation to being excluded. He’s also setting up, thanks to another depth composition, the chair in the hallway by the staircase. At the climax, it’s Zan, as beaten down as Birdie, who slumps in that chair.

Thanks to depth staging and deep-focus cinematography, the second image emphasizes Birdie’s solitude and prophesies Zan’s.

Which only makes my first question more pressing. Some shots of the quarrel leading up to Horace’s collapse on the stair exhibit flagrant deep focus.

We know from other shots in the film, like the Birdie/Zan comparison, that Wyler could have simply shown us Regina on the sofa in the foreground, in long shot or medium shot, while keeping Horace in focus in the background. In fact, Wyler tells us that Toland said, “I can have him sharp, or both of them sharp.” Why opt for shallow focus that makes Horace’s staircase seizure blurry and hard to see?

Fun with functions

Asking why? about something in an artwork actually veils two different questions.

The first is: How did it get there? The answer is a causal story about how the element came to be included.

The second sense of why is: What’s it doing there? That’s not a question of causes but of functions. How does the element contribute to the other parts and the artwork as a whole?

Take the second question first. You can imagine many functional reasons for Wyler’s choice. Exactly because the rest of the film keeps image planes sharp, this moment gains a unique emphasis. Horace’s collapse is marked as a major turning point in the plot. In an ordinary film, we wouldn’t notice an out-of-focus background. Here, by reverting to the more traditional choice, Wyler makes shallow focus stylistically prominent. For once in a film, a dramatic high point isn’t given to us with maximum visibility.

Another function is character revelation. In the film as a whole, we haven’t been consistently restricted to any one character. Here, Wyler could have concentrated on either Horace or Regina, or he could have given them equal treatment. An obvious choice would have been intercutting shots of Horace crawling up the steps with shots of Regina, impassively turned from him. Probably most directors would have done it that way.

Alternatively, we might have been attached to Horace, letting us see Regina in the distance. That would have diminished her reaction and played up Horace’s suffering.

Wyler’s choice puts the emphasis not on the action—thanks to the distant framing, Horace’s collapse can almost be taken for granted—but Regina’s reactions, or rather non-reactions, moment by moment. We’re made to see her turning slightly to listen to his struggles, while her staring eyes suggest that she’s visualizing the action with a horrified fascination. It’s as if her denying him the medicine was an experiment in seeing how far she could go. Now she knows. Her straining face is virtually willing her husband to die.

Keeping both this monstrous woman and her victim in focus would have divided our attention, then, and Wyler wants it squarely on Regina. He seems to have said as much in interviews.

We said we’ve got to stay on Bette all the time and just see this thing in the background, see him going in the background, but never lose her.

I wanted audiences to feel they were seeing something they were not supposed to see. Seeing the husband in the background made you squint, but what you were seeing was her face.

The second remark suggests another functional result of Wyler’s choice. By making the collapse almost indiscernible, we become very aware of what we can’t see. Thanks to selective focus, Bazin remarked, “The viewer feels an extra anxiety and almost wants to push the immobile Bette Davis aside to get a better look.” The dramatic tension of the scene finds its counterpart in our frustration to see what any other film would show us.

Finally, we should note that the staircase is an essential element in the film’s drama. Horace’s collapse is only one major incident taking place around and on it. Significantly, when Zan finally breaks free of Regina and the rest of the family, the matriarch learns of it standing on the stairs. Having all but murdered her husband there, now she sees her daughter abandon her.

Shoot my good side

The Bishop’s Wife (1948).

There are other functions we, as good critics, might seek out. For all of them, there is probably a loose causal story we’re relying on: Wyler and his colleagues made some choices that bore fruit. Some of those choices may have aimed at fulfilling the functions we notice. Other functions we notice may come along as bonuses—unintended but still benefiting the scene. Unintended consequences, good or bad, come up in art as elsewhere.

There remains the other implication of why-did-they-do-it questions: the one that seeks out quite specific causes that govern the scene. How do we tackle that?

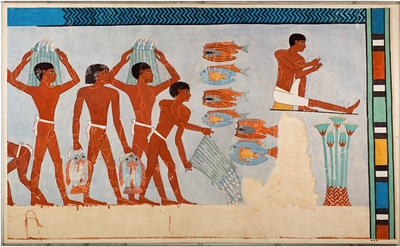

In my book On the History of Film Style, from which some of these Little Foxes observations are drawn, I argued that we can make stretches of stylistic history intelligible by thinking in terms of problems and solutions. Art historians have done this for a long while. Assuming that you want to suggest that something in the picture is farther away than something else, how do you do it? One way is through overlap, as in Egyptian art. Here the fishermen overlap the background, their legs overlap each other’s, and the strings of fish that one is carrying overlap some legs.

Later image-makers suggest variable distances through size variations, placement in the format (a little bit of that here, with the river above/behind the men), tonal contrast, atmospheric perspective, linear perspective, and other techniques. These can be considered solutions, available to artists of different times and places, to the problem of suggesting three dimensions on a flat surface.

A problem/solution way of thinking can clarify some developments in the history of filmmaking too. If you have to represent two actions taking place simultaneously, how can you do it? Crosscutting, as Griffith and others showed in the 1910s, solves that problem. It offers spillover benefits too, such as controlling pace. Similarly, there’s the problem of representing spoken dialogue. Silent films solved this in various ways—through a commenter in the theatre (the benshi in Japan), through actors voicing the roles behind the screen, and most commonly through intertitles. Later, synchronized sound solved the problem in a more thoroughgoing way.

These are very general answers to the how-did-it-get-there question. Occasionally we get more concrete information about problems and solution. For example, some Hollywood stars believed that one side of their faces was more appealing than the other. The stars with the most power could insist on being filmed on their good side, which led directors to make particular staging choices. (Claudette Colbert insisted her left side was her good side, so she’s usually positioned on screen right, with her face turned toward screen left.) David Butler knew that Edward G. Robinson likewise favored his left side, so Butler needed to stage Robinson’s one appearance in It’s a Great Feeling (1949) with him entering a scene from right to left and playing in that position.

One vain star is problem enough, but what happens when you have two who prefer being shot from the same side? According to Henry Koster, the demands of Cary Grant and Loretta Young led to the staging of the scene shown at the top of this section. (For my reservations, see the codicil to this entry.)

The Little Foxes production provides evidence of another very specific problem. In staging the staircase collapse, Wyler faced an unusual difficulty. The actor playing Horace, Herbert Marshall, had a prosthetic leg.

Marshall lost his right leg, from the hip down, in World War I. Through practice he managed to stroll quite smoothly nonetheless, and he became a significant star and featured player in theatre and films. He doesn’t need to walk much in The Little Foxes because his character is rolled around in a wheelchair. But the parlor-and-staircase scene was very demanding. As Wyler explains:

Now there was another problem involved with that, and that was the fact that Herbert Marshall has a wooden leg and couldn’t make the stairs, you see. This is a trade secret. I had him stagger in the background, get behind her and just for a moment when he gets to the stairs he had to go to a landing over there, and just for a moment went out of the picture. And a double came in and went up the stairs, staggered way behind out of focus.

Here you can see Marshall leave the foreground.

An axial cut in to Regina shows him stumbling behind her and going out of shot in the distance. This much Marshall could manage.

At that point the double stumbles into the frame and starts to crawl up the staircase.

Regina leaps up and runs to the rear, and the camera racks focus to the stair, but by now the double’s face is out of frame.

So the director solved the problem of the actor’s disability by a combination of deep staging, the use of a double, and shallow focus. This “trade secret” yielded a range of effects that, I think most viewers would agree, were vivid and exciting.

But there’s always more than one way to do anything. Given the constraint of Marshall’s artificial leg, or a player’s insistence on being shot from one side, or the leading lady’s overnight pimple, a director can work around it in several ways. One of the few critics to notice the implications of Wyler’s choice was Raymond Durgnat, a critic very sensitive to style.

Given a “pimple” or a “wooden leg,” different stylists will find different solutions. One changes the camera-angle; another introduces a last-minute panning shot; another will retain the original set-up, but throw heavy shadows to conceal the offending detail; another will interpose a pot of flowers or a table-cloth to conceal the trouble spot from the camera. The director has ample opportunity to maintain his style in the face of “accident.” And it’s no exaggeration to say that such stylists as Dreyer and Bresson would imperturbably maintain their characteristic style even if the entire cast suddenly turned up with pimples and wooden legs.

I’d add only that the director’s choices are further constrained. Beyond the immediate problem, the broader pressure of norms will kick in. The norms of classical studio lighting, cutting, and performance limit the ways Toland and Wyler can cover up Marshall’s infirmity. The norms of quality A-picture American filmmaking of the period militate against, say, editing the scene so that a dummy is substituted for Marshall on the stair. (We might get that in a serial, though.)

There are also the intrinsic norms set up in The Little Foxes as a formal whole. These favor handling the scene in depth in some way. Wyler reports the decision: “We said we’ve got to stay on Bette all the time and just see this thing in the background, see him going in the background, but never lose her.” Wyler’s earlier choices in the film created a kind of path-dependence for this critical moment. Deep-space staging could stay in tune with the rest of the film; but because of his actor’s infirmity, he could give up deep-focus cinematography. This solution created a vivid variant on the film’s intrinsic norm.

You can also argue that by deciding to call our attention to a distant plane in soft focus, Wyler fell back on something he had tried before. In the extraordinary late silent The Shakedown (1929), he showed a pie being stolen in a diner. First, there’s a close-up, then a shot of the main couple looking to the background. In the center, out of focus underneath the coffee urn, the pie is slipping away.

The action isn’t very discernible in my image, which is from a 35mm print; but the scene is shot quite soft anyway. I think audiences notice the gesture, slight as it is, because it’s centered and nothing else is moving in the frame. More visible is the background action in a shot Wyler and Toland used in Dead End (1937). Two gangsters are sitting in a bar debating kidnapping a child. In the out-of-focus background,we can discern a woman wheeling a baby carriage along the sidewalk. She isn’t the target, just a sort of reminder of children’s vulnerability. As in The Little Foxes, a centered background action attracts our attention and makes us strain to identify it.

Faced with a similar problem in The Little Foxes, Wyler had the chance to dramatize a soft-focus background to a much greater extent than in these films.

One more causal factor might have shaped Wyler’s decision. Lillian Hellman’s original play takes place wholly in the Giddens’ parlor and the hallway behind. The play text indicates that the staircase is in the rear of the set, with a landing offstage. The furniture sits downstage, closer to the audience. The foreground/background interaction in Wyler’s staging is already there, in a rougher form, in the play’s set arrangement.

And how does the play handle the moment of Horace’s collapse? When Horace’s medicine bottle breaks, Regina doesn’t move. Calling for Addie the maid, Horace leaves and staggers to the rear playing area.

He makes a sudden, furious spring from the chair to the stairs, taking the first few steps as if he were a desperate runner. Then he slips, gasps, grasps the rail, makes a great effort to reach the landing. When he reaches the landing, he is on his knees. His knees give way, he falls on the landing, out of view. Regina has not turned during his climb up the stairs. Now she waits a second. Then she goes below the landing, speaks up.

REGINA: Horace, Horace.

The foreground/background dynamic, as well as the frozen indifference in Regina’s performance, are written into the scene’s stage directions. Hellman’s instructions yield a further hint: Horace “falls on the landing, out of view.” Within the norms of the deep-focus aesthetic, Wyler and Toland found a cinematic equivalent for this barely-offstage action–one appropriate for their film’s particular style. They make Horace present, but he’s “out of view.”

Somebody may say: “See? You don’t need all this fancy analysis. At bottom, Wyler was forced to shoot the scene this way because of Marshall’s bum leg.” This retort assumes that causal factors always trump functional ones. Instead, I think that by considering causal factors, insofar as we can know them, alongside functional ones, we can better understand filmic creativity in history.

Durgnat’s point shows us how. Even when contingent circumstances “force” a filmmaker to change course, there are always several ways to do that. Picking any option brings in a cascade of other constraints and opportunities. Once Wyler has decided to double Marshall and sustain the take on Davis, soft focus is more or less necessary so we don’t spot the stand-in. But the soft-focus provides a nifty opportunity to create the sorts of functions and effects we’ve already noticed.

Like everybody else, filmmakers choose within constraints—some apparent, some less visible, many just taken for granted. Those constraints limit what can be done, but they also enable other things to happen, perhaps things that the filmmaker couldn’t have planned in advance. Once other filmmakers realize the results, they can plan in advance. A moviemaker today can try out Wyler’s solution, free of the pressures that drove him to it. A significant part of filmmaking’s traditions may consist of workarounds.

The Ostlund epigraph, apparently not available online, is taken from Hollywood Reporter’s December awards issue, p. 13. My Egyptian picture comes from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s called Fish Preparation and Net Making, from the Tomb of Amenhotep (1479-1458 BCE), as rendered by Nina de Garis Davies. I draw the stage directions in The Little Foxes from Lillian Hellman, The Collected Plays (Little, Brown, 1971), 195.

My quotations about It’s a Great Feeling and The Bishop’s Wife come, respectively from two books by Irene Kahn Atkins, David Butler (Scarecrow, 1993), 227; and Henry Koster (Scarecrow, 1987), 87. Koster’s memory fails him in his account of the Bishop’s Wife window scene. It seems likely that Loretta Young favored her left side, which is her dominant orientation throughout the film. But there’s no evidence in the film that Cary Grant favored that side of his face too. The scene at the window is too brief to count as an instance of much of anything.

When I wrote On the History of Film Style in the mid-1990s, I had the nagging memory that Marshall’s artificial leg played a role in Wyler’s staging, but I put it down as legend. (It’s a pity I didn’t pursue it, because the information would have fitted snugly into my sixth chapter.) Only when I discovered a 1972 interview with Wyler, with the “trade secret” mentioned above, did I realize there was something to the story. That interview was once online, but seems to have vanished. It’s available at Columbia University. Durgnat’s discussion is in Films and Feelings (MIT Press, 1967), 41. My other quotations from Wyler come from Axel Madsen, William Wyler (Crowell, 1973), 209.

Otis Ferguson reported on the filming of a different scene in The Little Foxes; I discuss that here. More generally, on the Bazin-Wyler connection, see this entry. Other Wyler-related entries can be canvassed here. For more on Hollywood’s development of deep staging and deep focus, see not only On the History of Film Style but also Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. As for Bette Davis’s eyelids, much in evidence here, there’s this entry.

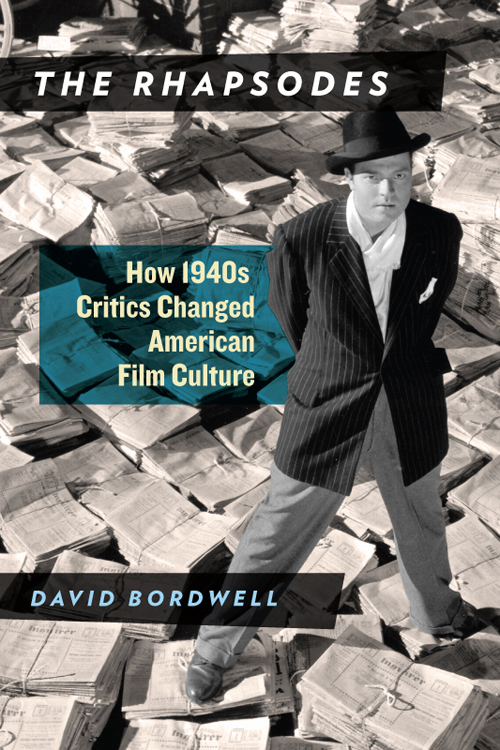

Otis Ferguson and the Way of the Camera

The original entry at this URL, published 20 November 2013, has been removed. Revised and expanded, it forms a chapter in the book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in spring 2016.

I discuss the development of the book in this entry.

You can find more information on the book here and here.

Thank you for your interest!

Foreground, background, playground

The Devil and Miss Jones (1941); The Hudsucker Proxy (1994)

DB here:

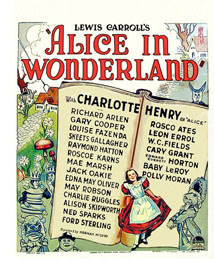

I’ve been waiting for thirty years for Alice in Wonderland. No, not the theatrical release of Tim Burton’s version. That interests me only mildly. I’m referring to the DVD release of the 1933 Paramount picture. I saw it on TV as a kid, and remembered it only dimly. But it bobbed up on my horizon in the summer of 1981 when I was doing research on our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was reluctant to attribute pioneering spirit to director Norman Z. McLeod. Instead, I realized that these images’ somewhat freaky look owed more to one of the strangest talents in Hollywood history.

I tried to see Alice in Wonderland, but I couldn’t track down a print. So for years I’ve been waiting to find if it confirmed what I saw on those typescript pages. In the meantime, for the CHC book and thereafter, I’ve bided my time, sporadically looking in on the career of one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. He’s the subject of a new web essay I’ve just posted here (or click on the top item under “Essays” on the left sidebar). Today’s blog entry is a teaser trailer for that.

Deep thinkers

It’s commonplace now to say that Citizen Kane (1941) pioneered vigorous depth imagery, both through staging and cinematography. Many of the film’s shots set a big head or object in the foreground against a dramatically important element in the distance, both kept in fairly good focus. But where did this image schema come from?

The standard answer used to be: The genius of Gregg Toland and Orson Welles. In the 1980s, however, I wanted to explore the possibility that something like the deep-focus look had been a minor option on the Hollywood menu for some time. Once you look, it’s not hard to find Kane-ish images in 1920s studio films, from Greed (1924) to A Woman of Affairs (1929).

During the 1930s, William Wyler cultivated such imagery in some films shot with Toland, such as Dead End (1937), and some films shot by other DPs, such as Jezebel (1938). In turn, Toland had undertaken comparable depth experiments in films with other directors. Moreover, yet other directors, notably John Ford, had used this sort of imagery in films shot by Toland and others, such as George Barnes, Toland’s mentor. There are plenty of non-auteur instances too. (See my post on 1933 Columbia films.) We also find similar imagery in films from outside America. Here’s a stunner from Eisenstein’s Bezhin Meadow (banned 1937).

You see how complicated it gets.

What I concluded in Chapter 27 of CHC was that Toland and Welles didn’t invent the depth technique. They fine-tuned it and popularized it. Their predecessors, in the US and elsewhere, had staged the action in aggressive depth and used many of the same compositional layouts. But the wide-angle lenses then in use couldn’t always maintain crisp focus in both planes (below, American Madness, 1932).

Welles and Toland found ways to keep both close and far-off planes in sharp focus. They deployed arc lamps, coated lenses, and faster film stock. Although it wasn’t publicized at the time, we now know that some of the most famous “deep-focus” shots were also accomplished through back-projection, matte work, double exposure, and other special effects, not through straight photography. Again, though, this tactic was anticipated in earlier films. One of my favorite examples comes from a matte shot in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935).

Menzies seems to have planned for similar fakery. In the script for Alice in Wonderland we find: “CLOSE UP, leg of mutton. The room and characters in the background are on a transparency.”

The flashy depth compositions of the 1920s and 1930s were typically one-off effects, used to heighten a particular moment. Welles and Toland pushed further by making the depth look central to Kane’s overall design and by featuring such imagery in fixed long takes. The prominence of Kane may have encouraged several 1940s filmmakers, such as Anthony Mann, to make the depth schema part of their repertoire. But as the style was diffused across the industry, the hard-edged foregrounds became absorbed into dominant patterns of cutting and spatial breakdown. The static long takes of Kane remained a rare option, perhaps because they dwelt on their own virtuosity.

Digging up films made around the time of Kane, I found many filmmakers experimenting with the look that Toland and Welles highlighted. You can see touches of it in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and All That Money Can Buy (1941). Above all, there are two remarkable movies directed by, of all people, Sam Wood. Our Town (1940) turns Wilder’s play (itself surprisingly melancholy) into a Caligariesque exercise.

Several shots anticipate the low-slung depth, bulging foregrounds and all, that became the hallmark of Citizen Kane a year later.

Our Town also uses postproduction techniques that yield depth-of-field effects you couldn’t get in camera.

Perhaps even more startling is Wood’s Kings Row (1942), with deep-focus imagery that occasionally rivals Kane‘s.

From the evidence I was encountering, it seemed that Welles and Toland’s accomplishment was to synthesize and push further some deep-space schemas that were already circulating in ambitious Hollywood circles. Connecting some dots, I realized that one of the earliest champions of aggressive imagery in general, not just big foregrounds and deep backgrounds, was William Cameron Menzies.

Menzies frenzies

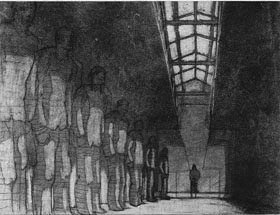

Menzies started out as an art director, most famously for United Artists. He designed sets for Mary Pickford’s Rosita (1923, directed by Lubitsch) and several Fairbanks films, notably The Thief of Bagdad (1924). He won the first Academy Award for set design and went on to a noteworthy career—most famously as production designer for Gone with the Wind (1939). He also directed films, such as Things to Come (1936) and Invaders from Mars (1953). Most significant for my purposes, he was production designer for Our Town, Kings Row, and three other films of the early 1940s directed by Sam Wood. And he designed the 1933 Alice in Wonderland. The drawings I saw in Edouart’s script were by Menzies or his assistants.

Menzies was one of the chief importers of German Expressionist visuals to the US. Although his early efforts leaned toward Art Nouveau effects, by the end of the 1920s he was cultivating a dark, contorted look keyed to the harsh geometry of city landscapes.

Since the late 1920s, Menzies had explored the possibility of steep depth compositions. He didn’t usually employ a big foreground, but he did favor overwhelming perspective–either abnormally centered or abnormally decentered. Here is his sketch for Roland West’s Alibi (1929) and the shot from the finished film.

Menzies loved slashing diagonals created by architectural edges and worm’s-eye viewpoints. The harrowing opening of Things to Come is full of such flashy imagery.

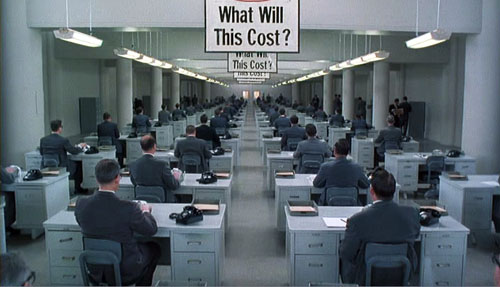

Menzies calmed his style down for GWTW, although the sequences he directed bear traces of his inclinations. And in his work for other directors he managed to slip in a few odd shots. Here, for instance, is a typically maniacal central perspective view from H. C. Potter’s Mr. Lucky (1943). Squint at this image and you’ll see that it’s weirdly symmetrical across both horizontal and vertical axes.

When he met Sam Wood, it seems, Menzies found a director ready to let his imagination roam further. In these collaborations, we get depth shots à la Welles and Toland, but also skewed perspectives. Pride of the Yankees (1943/44) searches for ways to make a baseball stadium look like a Lissitzky abstraction.

Menzies subjects the partisans of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1944) to his sharp diagonals as well.

Alice, we hardly knew ye

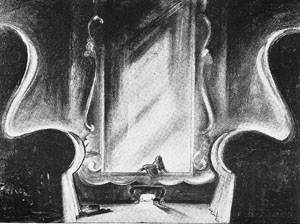

What then of Alice in Wonderland? Back in the early 1980s, I wasn’t permitted to photocopy or photograph script pages. Here is one of the few sketches I later found for the film. Alice crawls into the mirror with looming armchairs in the foreground.

Surely, I thought, the film would be an early example of the depth aesthetic that would be developed by Welles, Wyler, and Wood/ Menzies. Alas, the film has nothing like those imperious armchairs.

In fact, Alice proves a huge disappointment on the pictorial front. Menzies expended all his ingenuity on the special effects, coordinated by Paramount master Farciot Edouart. Although the spfx are not in the league of that other big 1933 effects-film King Kong, they are pretty solid for the time. It’s just that this remains a painfully arch, flatly filmed exercise.

But I look on the bright side. Menzies created some memorable movies, both on his own and with other directors. (Of his directed films, not only Things to Come but Address Unknown, 1944, remain of interest today.) Perhaps most important, his stylistic boldness may have encouraged other filmmakers to try something fresh. Most immediately there is Since You Went Away (1944), a big Selznick production that bears traces of the Menzies touch.

More broadly, Menzies represents a strand in American cinema that never really disappeared. His frantic Piranesian perspectives, canting the camera and filling the frame with grids, whorls, and cylinders, are still in use. And his head-on, wide-angle grotesquerie looks ahead to the Coen brothers. This shot of a department-store manager in The Devil and Miss Jones (1941) could come from any of their films.

Menzies’ films, though mostly not celebrated as classics, gave American cinema the permission to be peculiar. Meet me in the sidebar for a closer look at one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. Special thanks to Meg Hamel for going beyond the call of duty in posting that essay.

Invaders from Mars (1953); Shutter Island (2010).

Sleeves

DB here:

Earlier this month, when I was giving a lecture on Mizoguchi Kenji at our university museum, I showed two images from A Woman of Rumor (Uwasa no onna, 1954). It’s a little-known film of his, and it’s probably not up to his finest, but seeing the stills again on the big screen made me want to write about one scene. That scene displays aspects of Mizoguchi’s artistry that I touch on in one chapter of Figures Traced in Light and in the website supplement here.

This blog entry constitutes, I suppose, another supplement. After all, I couldn’t include in the book all the moments in Mizoguchi’s work that I find fascinating. But since comparison is a good way to get under a movie’s skin, my examination of a parallel scene from another movie may have more general interest. Even though Woman of Rumor doesn’t seem to be available on video, maybe looking at this pair of examples would inspire some readers to take an interest in one of the two or three greatest filmmakers who ever lived.

In the court of Regina

William Wyler and John Barrymore.

What a year 1941 was in the American cinema! We remember it for Citizen Kane but it also brought us How Green Was My Valley (a better film than Kane, I think), and items like Sergeant York (the biggest box-office hit), Dumbo, The Philadelphia Story, Suspicion, Ball of Fire, High Sierra, The Lady Eve, Meet John Doe, The Maltese Falcon, They Died with Their Boots On, and one of the most daring movies ever made in America, The Little Foxes.

An adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s play, The Little Foxes offers a study in unbridled capitalism. It shows how economic interests pit the South against the North and white against black. Psychologically, it analyzes a household gripped by the ruthless domination of the matriarch Regina (Bette Davis), the wiliest member of a family of grasping entrepreneurs. Regina has all but flattened her husband and is trying to make her daughter Alexandra oblivious to the family’s corruption.

The Little Foxes was also bold in its style—in its own way, as venturesome as Citizen Kane. It hasn’t been fully appreciated because Wyler is still thought of as a rather middlebrow talent, an overcautious director who toned down the flamboyance of Gregg Toland’s deep-space and deep-focus compositions.

Some day I hope to blog in defense of Wyler, middlebrow movies, and Midcult art in general. That would involve a detailed analysis of Little Foxes. (1) For now let’s just say that Wyler’s direction of the film won the admiration of no less than André Bazin. Bazin taught us to appreciate Wyler’s work, though with some prompting from Wyler and Toland (as I suggest here). Wyler was also appreciated by Mizoguchi, who, apparently grudgingly, told his screenwriter Yoda that he admired Wyler’s use of the “vertical frame.” (2) Later I’ll suggest one way of understanding that phrase. Mizoguchi met Wyler at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, when Ugetsu Monogatari was up against Wyler’s Roman Holiday for the Silver Lion.

One scene not discussed by Bazin or Mizoguchi, as far as I’m aware, has always gripped me. Regina’s brother Oscar has a wife, Birdie, who has turned into a passive alcoholic. Birdie has learned of plans to marry Xan off to Leo, her shallow son. Her will has been broken by Regina and Oscar, but she summons up the courage to blurt out to Xan that she mustn’t marry Leo, no matter how strongly the family insists. Xan, who has no inkling of how her family twists people to suit their ends, protests that no such thing could happen. But Oscar overhears Birdie warning Xan off.

Birdie and Oscar are about to leave at the end of the evening. Wyler begins with a standard two-shot, very slightly off-center. But as Birdie frantically warns Xan, Oscar’s sleeve and pant leg appear in the lower left of the frame, with the swagged curtain at the doorway hiding his face.

For us, this creates suspense. Only after Birdie has babbled out her warning do the two women notice he’s there. Xan, not knowing how Oscar abuses Birdie, heads off to bed.

As she climbs the staircase (very important in the film and the original play, this staircase) and heads off to her bedroom, Wyler’s camera arcs to reveal Oscar. Wyler now cuts to show, more or less from Birdie’s point of view, Xan going into her room.

Birdie watches anxiously, then turns to face Oscar, with a look of resigned apprehension.

Again suspense: Oscar won’t punish Birdie with Xan watching, but the girl’s departure puts Birdie in jeopardy. In addition, Wyler’s shot of her reaction anticipates the wrath she’ll face. (Patricia Collinge’s fluent performance is equal to the dynamics of Wyler’s visuals.) These cuts anchor our empathy; Wyler has been saving the close-up of Birdie for this moment.

We return to the master framing as Birdie heads toward Oscar, passing into a patch of shadow. As she does so, he raises his hand abruptly.

Wyler cuts to a two-shot. Oscar slaps Birdie so hard she seems to bounce against the left frame edge. She cries out and then tries to stifle her voice—a psychologically apt gesture for this woman who muffles her sorrows throughout the film.

Again, Wyler daringly sets a key action off-center. The brutal discontinuity of the cut, which crosses the axis of action and sharply changes shot scale, accentuates Oscar’s violence. It’s also rather elliptical; run the cut slowly, and you never see his hand strike her.

Xan hurries out of her room and comes to the banister, her face on the upper right balancing the placement of Birdie’s in the prior shot. In the next shot, we see, over her shoulder, Oscar stride out. Birdie follows meekly, assuring Xan that nothing’s wrong. The coda of the scene will emphasize Xan’s puzzled anxiety, a phase in her process of coming to understand the domineering fury that rules her family.

Low- and high-angle shots like this last pair recur throughout The Little Foxes, and I suspect that these are the sorts of thing Mizoguchi was invoking in mentioning Wyler’s “vertical” space. Wyler’s steep angles activate upper areas of the frame that many American directors hadn’t explored.

The act of overhearing a revealing conversation is a standard dramatic convention, but Wyler has refreshed and nuanced it. We know how it would be normally handled. We’d see either a shot showing Oscar stepping fully into the background, or a series of cuts showing first Birdie and Xan and then Oscar listening and watching. Wyler revises the standard schema, taking it for granted that we can pick up on a subtler cue than usual: just a bit of Oscar’s body intrudes.

As a result we have to be more alert. The information isn’t centered, but rather tucked into the lower left. And this option conceals Oscar’s face. Not that we’re doubting he’s angry, but delaying showing his anger builds up greater tension. Wyler, unlike today’s directors, knows when to build up to revealing things that we anticipate, making the final outburst more forceful when it comes. Further, the rest of the scene continues to deny us a clear view of Oscar’s anger, all of which gets squeezed into his gesture of slapping Birdie. It’s Birdie’s reaction that Wyler stresses, and Oscar’s contempt for her is conveyed simply by his bearing, his gesture, and his manner of stalking out of the foyer.

It’s not too much to talk about rigor here. The schemas dominating today’s filmmaking, the stylistic paradigm I call intensified continuity, would demand tight close-ups of everybody from the start. But providing them would make it harder for Wyler to raise the emotion when the startling slap comes. Maybe a contemporary director would render this spike in slo-mo, or with a wobbly handheld camera, but that tends to seem overbearing and pumped-up—as a lot of current stylistic pyrotechnics do. In any case, I’m betting that no American director today would use Oscar’s sleeve in the quietly ominous way Wyler does.

Mizoguchi’s game of vision

Mizoguchi Kenji, in glasses, during the making of Ugetsu.

Mizoguchi is renowned for his long takes, which are often sustained in distant views featuring considerable camera movement. In the Mizo chapter in Figures Traced in Light, I suggest that these stylistic choices spring from his effort to engage the viewer mesmerically—as he put it, “to work the viewer’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.” He asks us to downshift our attention to the finest details of the action, which he then modulates for expressive effect. I draw examples from various films across his career to show how he creates drama out of remarkably slight differences in character position, lighting, and other factors.

But what happens when he foreswears virtuoso camera movements and single-take scenes and breaks the drama up into several shots? Today, many ambitious directors seem to take pride in stretching out their takes, so cinephiles are sometimes inclined to see a cut as a loss of nerve and a concession to the audience. But I try to show in Figures that Mizoguchi sustains his concern for nuance when he creates an edited sequence. The modulation of fleeting details is to be found in his closer shots too.

In A Woman of Rumor, Hatsuko runs a teahouse that funnels customers to the geisha establishment behind it. She has tried to protect her daughter Yukiko from the shame of her profession. Hatsuko has also been cultivating a young doctor she hopes to marry, giving him money to set up a clinic. Now the doctor, Matoba, has become attracted to Yukiko. The scene I’m examining takes place during the performance of a noh drama. Hatsuko leaves the auditorium and finds Yukiko talking with Dr. Matoba.

As she passes around a screen, she hears Yukiko saying she wants to learn piano in Tokyo. Hatsuko looks left, and Mizoguchi cuts to an approximation of her optical point of view on the couple in the lounge.

So far, so conventional. Mizoguchi seems to follow the intercutting option for treating a scene of overheard conversation. But he goes further. Having laid out the action, Mizoguchi starts the lesson in just-noticeable-details . . . with a sleeve. He cuts to a reverse shot putting Matoba and Yukiko in the foreground. Hatsuko is still back there, though. We can see her kimono sleeve on the left, poking out from behind the screen.

A sharp-eyed viewer might also spot Hatsuko’s shadow on a wall, in the center of the shot, over Matoba’s shoulder. This blow-up shows both the sleeve and her silhouette.

Here, friends, is one reason we want to watch films in 35mm, and projected really big.

It’s now that Yukiko says that she may leave her mother, and Matoba replies, “Maybe I’ll go too.” This is devastating to Hatsuko. The two people whom she loves most seem to care nothing for her. Her shocked reaction is given in a medium-shot showing her shifting out from behind the screen, her face partially hidden.

Mizoguchi has picked one variant of the overheard-conversation schema: shot of speakers/ reaction shot of eavesdropper. But he’s done so in his own way, using the barely discernible kimono sleeve to signal Hatsuko’s presence in the full shot of the couple. Likewise, the shot of Hatsuko listening is far from the usual close-up. Like other Japanese directors, Mizoguchi was fond of this arresting single-eye image. He used it earlier in his career, as shown in the first frame at the top of this entry, from Hometown (Furusato, 1930). The second frame is the last shot of his last film, Street of Shame (Akasen chitai, 1956). Quite a shot to end your career on, I’d say.

Most Japanese directors use this single-eye framing as a one-off flourish, but not Mizoguchi. The device epitomizes his demand that we concentrate on a detail. Isolating half a face gives impact to the slightest shift in the eye and eyebrow. Moreover, the split face reappears as a pictorial motif later in the scene.

As Matoba says he’ll go back to Tokyo for his doctorate, Mizoguchi cuts back to the setup for the second shot. Hatsuko moves left to sit on a chair around the corner from the sofa. This prepares for another, more prolonged game of visibility.

Now we get a thirty-second take of the couple on the sofa. As the scene develops, it becomes evident that Matoba is seducing Yukiko. Hatsuko slips in and out of visibility, her actions responding to and even echoing Matoba’s pressure on the girl. First, as he talks with Yukiko, we see Hatsuko’s sleeve and shoulder, between the vase and his shoulder. But as he slips his arm around Yukiko, her elbow moves aside, in an echo of his gesture.

Then, when Matoba presses his attention (“We’ll help each other . . . Depend on me”), Hatsuko’s face pops into view as her fingers emerge to grip the edge of her chair. Mizoguchi then lets her face subside, again slicing it in half.

In effect, this shot replays and expands upon the tactic governing the earlier two shots. Again we get the just-noticeable presence of the sleeve, but now rhyming with the action in the foreground. And again we get the facial reaction, impeded by a vertical cutoff, but this time in the distant shot rather than in a closer view. It turns out that those first four shots were training us for this more intricate game of vision.

At the moment Hatsuko’s face is sliced in half, Mizoguchi cuts. Now he prolongs the close view as he had extended the full shot of the couple. In this thirty-second shot, we watch her reaction, played out in slight modulations—changes in her facial expression, changes in the aspect of her face that we see, and changing relations to the curling palm plant in the vase before her.

We get a new angle on Hatsuko, slightly high, as Matoba says, “I’ll tell her.” Hatsuko stands up abruptly and the camera tilts to follow her.

With the simple action of her rising up, Mizoguchi changes his composition sharply. Hatsuko’s position in the frame changes only a little bit, but the massive vase on the left gives way to the curling stalks on the right. Radically refreshing a shot through minimal means is one felicity of Mizoguchi’s art.

Then, as if the full import of Matoba’s betrayal dawns on her, Hatsuko lowers her head sadly. Again her eyes are split up, this time thanks to the twisting stalk. In a characteristic Mizoguchi gesture, she turns from the camera, as if ashamed to face us, but also summoning up reserves for the next emotional shift.

When she turns back, her face burns.

I take this to be the scene’s emotional climax. Mizoguchi could have given it to us much sooner, by having Hatsuko turn angry as she peeped out from behind the screen. Instead, his game of vision allowed him to build patiently toward this unimpeded shot of her reaction. It prepares us for the next stages of the drama, later scenes in which she will confront her patron and launch jealous accusations at Yukiko.

Now we hear the performance ending, and Hatsuko lifts her head. This phase of the scene ends when Mizoguchi cuts to audience members coming into the lounge and greeting her.

By 1954 Mizoguchi had surely seen The Little Foxes. Had he decided to redo Wyler’s virtuoso staging in his own manner?

Both directors work with similar ingredients: overheard conversation, depth shots, judicious close-ups, and partial views. But the narrational weightings differ. Wyler’s film aligns and allies us with the people talking, whereas A Woman of Rumor ties us to the listener. (3) Wyler’s eight shots take eighty-one seconds; Mizoguchi’s eight shots take about two minutes.

Wyler’s handling is brisk, tense, and remarkably nuanced within the Hollywood tradition. Mizoguchi gives us his scene more sedately, wringing just-noticeable differences out of unassertive performances and simple elements of setting. No slap here, just a drama of wounded pride, lost love, and jealousy played out in the face, back, and sleeve of Tanaka Kinuyo, shifting behind a floral arrangement. What Wyler gives us as one sharp effect, Mizoguchi turns into a delicate, prolonged game of vision.

Am I fussing over minutiae? No; Wyler and Mizoguchi did. We just have to follow where they lead. As I try to show in my essay on blinking in cinema (4), directors attend closely to things that might seem trivial. Our analysis needs to be as fine-grained as their craft and artistry.

Oh, yes: at Venice Ugetsu won the Silver Lion. Wyler had to be content with Roman Holiday’s three Academy Awards.

(1) I sketch some of the possibilities in On the History of Film Style (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 225-227.

(2) For more on Mizoguchi’s competition with Wyler, see Figures Traced in Light (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 134.

(3) I’m referring to Murray Smith’s deft analysis of what he calls alignment and allegiance in our relation to film characters. See Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), Chapters 5 and 6.

(4) “Who Blinked First?” in Poetics of Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2007), 327-335.

PS 3 December: Thanks to Michael Kerpan for a name correction, and for the information that Woman of Rumor was once available on a French DVD.

PPS 27 February 2008: Good news. Now Woman of Rumor is available on the wonderful Eureka! Masters of Cinema series, along with the superb Chikamatsu Monogatari. The discs come with voice-over commentary by Tony Rayns and essays by Keiko McDonald and Mark LeFanu.