Archive for the 'People we like' Category

Movies by the numbers

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022). Publicity still.

DB here:

Cinema, Truffaut pointed out, shows us beautiful people who always find the perfect parking space. Mainstream movies cater to us through their stories and subjects, protagonists and plots. But they have also been engineered for smooth pickup. Their use of film technique is calculated to guide us through the action and shape our emotional response to it.

How this engineering works has fascinated film psychologists for decades. Over a century ago, Hugo Münsterberg proposed that the emerging techniques of the 1915 feature film made manifest the workings of the human mind. In ordinary life, we make sense of our surroundings by voluntarily shifting our attention, often in scattershot ways. But the filmmaker, through movement, editing, and close framings, creates a concentrated flow of information designed precisely for our pickup. Even memory and imagination, Münsterberg argued, find their cinematic correlatives in flashbacks and dream sequences. In cinema, the outer world has lost its weight and “has been clothed in the forms of our own consciousness.”

Over the decades, many psychologists have considered how the film medium has fitted itself to our perceptual and cognitive capacities. Julian Hochberg studied how the flow of shots creates expectations that guide our understanding of cinematic space. Under the influence of J. J. Gibson’s ecological theory of perception, Joseph Anderson reviewed the research that supported the idea that films feed on both strengths and shortcomings of the sensory systems we’ve evolved to act in the environment. In more recent years, Jeff Zacks, Joe Magliano, and other visual researchers, have gone on to show how particular techniques exploit perceptual shortcuts (as in Dan Levin’s work on change blindness and continuity editing errors https://vimeo.com/81039224). Outside the psychologists’ community, writers on film aesthetics have fielded similar arguments. An influential example is Noël Carroll’s essay “The Power of Movies.”

Over the decades, many psychologists have considered how the film medium has fitted itself to our perceptual and cognitive capacities. Julian Hochberg studied how the flow of shots creates expectations that guide our understanding of cinematic space. Under the influence of J. J. Gibson’s ecological theory of perception, Joseph Anderson reviewed the research that supported the idea that films feed on both strengths and shortcomings of the sensory systems we’ve evolved to act in the environment. In more recent years, Jeff Zacks, Joe Magliano, and other visual researchers, have gone on to show how particular techniques exploit perceptual shortcuts (as in Dan Levin’s work on change blindness and continuity editing errors https://vimeo.com/81039224). Outside the psychologists’ community, writers on film aesthetics have fielded similar arguments. An influential example is Noël Carroll’s essay “The Power of Movies.”

James Cutting’s Movies on Our Minds: The Evolution of Cinematic Engagement, itself the fruit of many years of intensive studies, builds on these achievements while taking wholly original perspectives as well. Comprehensive and detailed, it is simply the most complete and challenging psychological account of film art yet offered. I can’t do justice to its range and nuance here. Consider what follows as an invitation to you to read this bold book.

Laws of large numbers

The Martian (2015). Publicity still.

Cutting’s initial question is “Why are popular movies so engaging?” He characterizes this engagement—a more gripping sort than we experience with encountering plays or novels—as involving four conditions: sustained attention, narrative understanding, emotional commitment, and “presence,” a sense that we are on the scene in the story’s realm. Different areas of psychology can offer descriptions and explanations of what’s going on in each of these dimensions of engagement.

His prototype of popular cinema is the Hollywood feature film—a reasonable choice, given its massive success around the world. The period he considers runs chiefly from 1920 to 2020. He has run experimental studies with viewers, but the bulk of his work consists of scrutinizing a large body of films. Depending on the question he’s posing, he employs samples of various sizes, the largest including up to 295 movies, the smallest about two dozen. Although he insists he’s not concerned with artistic value, most are films that achieved some recognition as worthwhile. He and his research team have coded the films in their sample according to the categories he’s constructed, and sometimes that process has entailed coding every frame of a movie.

Like most researchers in this tradition, Cutting picks out devices of style and narrative and seeks to show how each one works in relation to our mind. His list is far broader than that offered by most of his predecessors; he considers virtually every film technique noted by critics. (I think he pins down most of those we survey in Film Art.) In some cases he has refined standard categories, such as suggesting varieties of reaction shot.

Starting with properties of the image (tonality, lens adjustments, mise-en-scene, framing, and scale of projection), he moves to editing strategies, the soundtrack, and then to matters of narrative construction. For each one he marshals statistical evidence of the dominant usage we find in popular films. For example, contemporary films average about 1.3 people onscreen at all times, while in the 1940s and 1950s, that average was about 2.5. Across his entire sample, almost two-thirds of all shots show conversations—the backbone of cinematic narrative. (So much for critics who complain that modern movies are overbusy with physical action.) And people are central: 90% of all shots show the head of one or more character.

Some of these findings might appear to be simply confirming what we know intuitively. But Big Data reveal patterns that neither filmmakers nor audiences have acknowledged. Granted, we’ve all assumed that reaction shots are important in cueing the audience how to respond. Cutting argues that despite their comparative rarity (about 15% of a film’s total) they are central to our overall experience: they are “popular movies’ most important narrational device.” They invite the audience to engage with the character’s emotions, and they encourage us to predict what will happen next.

This last role emerges in what Cutting calls the “cryptic reaction shot,” in which the response is ambivalent. Such shots show a moment when a character doesn’t speak in a conversation (for example, Jim’s reactions in my Mission: Impossible sequence). Filmmakers seem to have learned that

these shots are an excellent way to hook the viewer into guessing what the character is thinking—what the character might have said and didn’t. They also serve as fodder for predicting what the character will do next (174-175).

Cryptic reactions gather special power at the scene’s end. Whereas films from the 1940s and 1950s ended their scenes with such shots about 20% of the time, today’s films tend to end conversations with them almost two-thirds of the time. Since reading Cutting’s book I’ve noticed how common this scene-ending reaction shot is in movies (TV shows too). It’s a storytelling tactic that nobody, as far as I know, had previously spotted.

Similarly, Cutting tests Kristin’s model of feature films’ prototypical four-part structure. He finds it mostly valid, both in terms of data clustering (movement, shot lengths, etc.) and viewers’ intuitions about segmentation. But who would have expected what he found about what screenwriters call the “darkest moment”? Using measures of luminance, he finds that “this point literally is, on average, the darkest part of a movie segment” (285).

Cutting has found resourceful ways to turn factors we might think of as purely qualitative into parameters that can be counted and compared. To gauge narrative complexity, he enumerates the number of flashbacks, the amount of embedding (stories within stories), and particularly the number of “narrational shifts” in films. Again, there is a change across history.

Movies jump around among locations, characters, and time frames considerably more often than they used to. . . . Scenes and subscenes have gotten shorter. In 1940, they averaged about a minute and a half in duration, but by 2010 they were only about 30 seconds long (271-272).

His illustrative example is the climax of The Martian, where in four minutes and 35 shifts, the narration cuts together seven locations, all with different characters. Something similar goes on in the motorcycle chase of Mission: Impossible II and the final seventy minutes of Inception.

These examples show that Cutting is going far beyond simply tagging regularities in an atomistic fashion. Throughout, he is proposing that these patterns perform functions. For the filmmakers, they are efforts to achieve immediate and particular story effects, highlighting this or that piece of information. Showing few people in a shot help us concentrate on the most important ones. Conversations are the most efficient way to present goals, conflicts, and character relationships. Editing among several lines of action at a climax builds suspense. He suggests that because viewer mood is correlated with luminance, the darkest moment is triggering stronger emotional commitment.

But Cutting sees broader functions at work underneath filmmakers’ local intentions. Movies’ preferred techniques, the most common items on the menu, smoothly fit our predispositions—our tendencies to look at certain things and not others, to respond empathically to human action, to fit plots together coherently. Filmmakers have intuitively converged on powerful ways to make mainstream movies fit humans’ “ecological niche.”

And those movies have, across a century, found ways to snuggle into that niche ever more firmly. As we have learned the skills of following movie stories, filmmakers have pressed us to go further, stretching our sensory capacities, demanding faster and subtler pickup of information. Cutting’s numbers lead us to a conception of film history, the “evolution of cinematic engagement” promised in his subtitle.

Film history without names

Suspense (Weber and Smalley, 1913).

Central to Cutting’s psychological tradition is the idea that engagement depends minimally on controlling and sustaining attention. The techniques itemized almost invariably function to guide the viewer to see (or hear) the most important information. Filmmakers discovered that you can intensify attention by cooperation among the cues. Given that humans, especially faces, carry high information in a scene, you can use lighting, centered position, frontal views, close framings, figure movement, and other features of a shot to reinforce the central role of the humans that propel the narrative. When the key information doesn’t involve faces or gestures, you can give objects the same starring role.

Movies on Our Minds is very thorough in showing through statistical evidence that all these techniques and more combine to facilitate our attention. As an effort of will you can focus your attention on a lampshade, but it won’t yield much. The line of least resistance is to go with what all the cues are driving you to. But the statistical evidence also points to changes across history. What’s going on here?

Most basically, speedup. Cutting asked undergraduate students to go through films twice, once for basic enjoyment and then frame by frame, recording the frame number at the beginning and ending of each shot. He found that by and large the students enjoyed the older films, but some complained that these older movies were slower than what they ordinarily watched.

This impression accords with both folk wisdom and film research. Most viewers today note that movies feel very fast-moving, compared with older films. There’s also a considerable body of research indicating that cutting rates have accelerated since at least the 1960s. More loosely, I think most people think that story information is given more swiftly in modern movies; our films feel less redundant than older ones. Exposition can be very clipped. Abrupt changes from scene to scene are accentuated by the absence of “lingering” punctuation by fade-outs or dissolves. Indeed, one scene is scarcely over before we hear dialogue or sound effects from the next one. Characters’ motives aren’t always spelled out in dialogue but are evoked by enigmatic images or evocative sound. The Bourne Identity attracted notice not just for its fragmentary editing but also for its blink-and-you’ll-miss-them “threats on the horizon”—virtually glimpses of what earlier films would have dwelled on more. From this angle, Everything Everywhere All at Once represents a kind of cinema that grandpa, and maybe dad, would find hard to follow. (Actually, I’m told that some audiences today have trouble too.)

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I suggested some causal factors shaping speedup, including various effects of television. Cutting grants that these may be in play, but just as he looks for an underlying pattern of functional factors in his ecology of the spectator, he posits a broad process of cinematic evolution similar to that in biology.

Look at film history simply as succession of movies. From a welter of competing alternatives, some techniques are selected and prove robust. They are replicated, modified in relation to the changing milieu. Others fail. For instance, the split-screen telephone shot of early cinema, as in the above frame from Suspense, became “a failed mutation” when shot/ reverse-shot editing for phone calls became dominant. As the main line of descent has strengthened, variation has come down to “selected tweaks” like eyelights and Steadicam movement.

Within this framework, filmmakers and audiences participate in a give-and-take.Through trial and error, early filmmakers collectively found ways to make films mesh with our perceptual proclivities. As viewers became more skilled in following a movie’s lead, there was pressure on filmmakers to go further and make more demands. If attention could be maintained, then shots could be shorter, scenes could move faster, redundancy could be cut back, complexity could be increased.

Viewers responded positively, embracing the new challenges of quicker pickup. As viewers became more adept, filmmakers could push ahead boldly, toward films like Memento and Primer. The most successful films, often financially rewarding ones like The Martian and Inception, suggest that filmmakers have continued to fit their boundary-pushing impulses to popular abilities.

Which means that audiences have adapted to these demands. But this isn’t adaptation in the strong Darwinian sense. With respect to his students’ reactions, Cutting writes:

I think . . . that the eye of a 20-year-old in the 2010s was faster at picking up visual information than the eye of a 20-year-old in the 1940s. This is not biological evolution. This is cultural education, however incidental it might be.

This process of cultural education, he suggests can be understood using Michael Baxandall’s concept of the “period eye.” Baxandall studied Italian fifteenth-century painting and posited that an adult in that era saw (in some sense) differently than we do today. Granted, people have a common set of perceptual mechanisms, but cultural differences intervene. Baxandall traced some socially-grounded skills that spectators could apply to paintings. In parallel fashion, given the rapidity of cultural change in the twentieth century, young people now may have gained an informal visual education, a training of the modern eye in the conventions of media.

Cutting insists that he isn’t suggesting that our attention spans have recently decreased, as many maintain. Instead, the idea of a period eye centers on

the growth and improvement of visual strategies as shaped by culture. If this idea is correct, then contemporary undergraduates have reason to complain about movies from the 1940s and 1950s that I asked them to watch.

By this account, film teachers have to recognize that their students, for whom any film before 2000 is an old movie, are possessed of a constantly changing “period eye.”

Failed mutations, or revision and revival?

City of Sadness (Hou, 1989).

I do have some minor reservations, which I’ll introduce briefly.

First, I don’t think that Baxandall’s idea of a period eye is a good fit for the dynamic that Cutting has identified. Baxandall’s concern is with a narrow sector of the fifteenth-century public: “the cultivated beholder” whom “the painter catered for.”

One is talking not about all fifteenth-century people, but about those whose response to works of art was important to the artist—the patronizing class, one might say. In effect this means a rather small proportion of the population: mercantile and professional men, members of confraternities or as individuals, princes and their courtiers, the senior members of religious houses. The peasants and the urban poor play a very small part in the Renaissance culture that most interests us now.

Ordinary viewers could recognize Jesus and Mary, the Annunciation or the Crucifixion, but for Baxandall the “period eye” involved a specific skill set. This was derived from such domains as business, surveying, ready reckoning, and a widespread artistic concepts like “foreshortening” or “stylistic ease.” The study of geometry prepared the perceiver to appreciate the virtuosity of perspective or proportion, but the untutored viewer could only marvel at the naturalness of the illusion.

It seems to me that Cutting’s 20-year-olds are not prepared perceivers in Baxandall’s sense. True, they may be alert to faulty CGI or a lame joke, but the whole point of focusing on mass-entertainment movies is that they engage multitudes, not coteries. The techniques Cutting explores are immediately grasped by nearly everybody, and no esoteric skills are necessary to feel their impact. Baxandall’s viewer is able to appreciate a painter’s rendition of bulk because he’s used to estimating a barrel’s capacity, but all Cutting’s viewer needs to get everything is just to pay attention.

Because the skills of following modern movies are so widespread, I wonder if Cutting’s case better fits the explorations of Heinrich Wöfflin, who flirted with the idea that “seeing as such has its own history, and uncovering these ‘optical strata’ has to be considered the most elementary task of art history.” Throughout his late career Wöfflin struggled to make the “history of vision” thesis intelligible. At times he implied that everyone in a given era “saw” in a way different from people in other eras. At other times he proposed that of course everyone sees the same thing but “imagination” or “the spirit” of the period and place shape how we understand what we see. This is murky water, and you can sense my skepticism about it. I don’t see how we could give the “period eye” for cinema much oomph on this front, but I think we might salvage Cutting’s central point. See below.

Secondly, by concentrating on mass-market cinema, “the movies,” and suggesting they fit our evolved capacities, we can easily overlook the alternatives. Obvious examples are the earliest cinema, which did involve some precise perceptual appeals (centering, frontality, selective lighting, emphasis through foreground/background relations) but not all the ones associated with editing. Given that tableau cinema had a longish ride (1895-1920 or so), it’s not inconceivable that, had circumstances been different, we would still have a cinema of distant framings and static long takes.

Cutting is aware of this. Rewind the tape of history, he says, and eliminate factors like World War I, and things could have turned out differently. But where would a long-running tableau cinema leave the story of cinema’s dynamic of natural selection? Would we have simply a steady state, without the acceleration of the last sixty years? Or would we look within the long history of tableau cinema for mutations and failed adaptations?

We have contemporary examples, in what has come to be called “slow cinema.” Hou Hsiao-hsien, Theo Angelopoulos, and other modern filmmakers have exploited the static long take for particular aesthetic effects. In another universe, they are the “movies” that hordes flock to see. Tableau cinema seems to me not a failed mutation, replaced by a style that more tightly meshed with spectators’ proclivities; it was an aesthetic resource that could be revived for new purposes. On a smaller scale, something like this happened with split-screen phone calls (as in Down with Love and The Shallows).

As the other arts show us, the past is available for re-use in fresh ways. Maybe nothing really goes away.

Which brings me to my last point. Baxandall’s emphasis on skills reminds us that we can acquire a new “eye” for appreciating films outside the mainstream. Cutting’s 20-somethings can learn to appreciate and even enjoy films that might strike them as slow. We call this the education of taste.

My inclination is to see the contemporary embrace of speedup as based in filmmakers’ and viewers’ more or less unthinking choices about taste. Indeed, Baxandall suggests that the period eye is a matter of “cognitive style,” a set of skills one person may have and another may lack.

There is a distinction to be made between the general run of visual skills and a preferred class of skills specially relevant to the perception of works of art. The skills we are most aware of are not the ones we have absorbed like everyone else in infancy, but those we have learned formally, with conscious effort: those which we have been taught.

Once the skills have been taught, we can exercise them for pleasure.

If a painting gives us opportunity for exercising a valued skill and rewards our virtuosity with a sense of worthwhile insight about that painting’s organization, we tend to enjoy it: it is to our taste.

I’d suggest that we have “overlearned” the skills solicited by mainstream movies and made them the automatic default for our taste. But we can also learn the skills for appreciating 1910s tableau cinema or City of Sadness. As we do so, we find we have cultivated a new dimension of our tastes. From this standpoint, the sensitive appreciators of slow cinema are far more like Baxandall’s educated Renaissance beholders than are the Hollywood mass audience. Perhaps to enjoy Feuillade or Hou today is to possess a genuine “period eye.”

None of this undercuts Cutting’s findings. But given the variety of options available, I’d argue that what the history of cinema reveals, among many other things, is a history of styles—some of which are facile to pick up, for reasons Cutting and his tradition indicate, and others which require effort and training and an open mind. Not clear-cut evolution, then, but just the blooming plurality we find in all the arts, with some styles becoming dominant and normative and others becoming rarefied . . . until artists start to make them mainstream. And the whole ensemble can be mixed and remixed in unpredictable ways.

There’s far too much in Movies on Our Minds to summarize here. It’s a feast of ideas and information, presented in lively prose. (The studies that the book rests upon are far more dependent upon statistics and graphs.) I should disclose that I read the book in manuscript and wrote a blurb for it. Consider this entry, then, as born of a strong admiration for James’s project.

Cutting’s book rests on years of intensive studies. Go to his website for a complete list. Most recently, he has traced a rich array of phone-call regularities across a hundred years. He has been a recurring player on this blog, notably here and here. James and I spent a lively week watching 1910s films at the Library of Congress, with results recorded here and here. The last link also provides more examples of revived “defunct” devices.

The tradition of film-psychological research I rehearse includes Hugo Münsterberg, The Film: A Psychological Study in Hugo Munsterberg on Film: The Photoplay: A Psychological Study and Other Writings, ed. Allan Langdale (Routledge, 2001; orig. 1916); In the Mind’s Eye: Julian Hochberg on the Perception of Pictures, Films, and the World, ed. Mary A. Peterson, Barbara Gillam, H. A. Sedgwick (New York: Oxford, 2007); Joseph D. Anderson, The Reality of Illusion: An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Film Theory (Southern Illinois University Press, 1996); Jeffrey Zacks, Flicker: Your Brain on Movies (Oxford, 2014). Noël Carroll’s essay “The Power of Movies” is included in his collection Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge, 1996).

Michael Baxandall’s most celebrated work is Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (Oxford, 1972); citations come from pages 29-29. My mention of Wölfflin relies on Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Early Development of Style in Early Modern Art, trans. Jonathan Blower (Getty Research Institute, 2015). My citation comes from p. 93.

One reference point for Cutting’s work is a book Kristin and I wrote with Janet Staiger, The Classical Hollywood Cinema, discussed here. See also Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood, which elaborates the argument for the four-part model, and my books On the History of Film Style and The Way Hollywood Tells It, along with the web video “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

Bye Bye Birdie (1963).

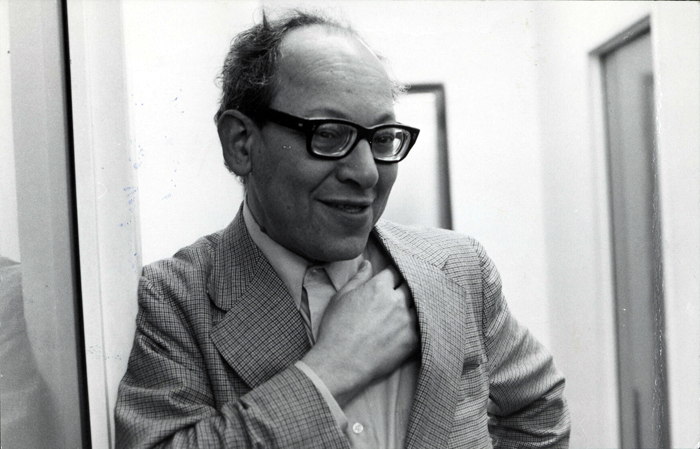

Jacques Ledoux, man of the cinema

Jacques Ledoux.

DB here:

Jacques Ledoux, one of the world’s premiere film archivists, died in 1988, but his example and influence live on. An insatiable cinéphile, a friend to filmmakers around the world, and a tireless collector of films for the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, Ledoux did not have the celebrity status of Henri Langlois. Quietly and modestly, he went about the task of building one of the great film libraries and launching traditions that outlived him. He was at the center of Belgian film culture, which was as cosmopolitan as any you would find in bigger European or American cities.

Central examples of his enterprise: EXPRMNTL, the Knokke-le-Zout experimental film festival; the annual Cinédécouvertes summer festival showcasing films of exceptional ambition that had not yet found a local distributor; and the L’Age d’or prize for films challenging “cinematic conformism.” Martin Scorsese’s The Big Shave (1967) had its premiere at Knokke, where it won the Prix L’Âge d’or. The first winner, in 1955, was Agnès Varda for La Pointe Courte; later winners read like a roster of great directors. The impulse continues to this day. In addition, Ledoux established a distribution branch that allowed student groups and film clubs to borrow prints for their screenings.

There were always obscure legends about his past. “Jacques Ledoux”–“Jacques the Gentle”–was a name he took late in life. Eventually we learned that as a boy he survived the Holocaust by jumping off a train shipping him to Auschwitz. By the end of the 1940s he was participating in the Archive’s activities and he eventually became the director.

Ledoux set about creating a vast showcase of world cinema. Five screenings, two of them silent films, ran every day of the year. Admission prices were low, to permit students to come. At the same time, Ledoux oversaw collections of film technology that formed the basis of educational exhibits. The Archive became the center of the city’s film activities.

Ledoux was a passionate collector, amassing films from far outside Belgium. He was curious about all types of cinema, mass-market and esoteric. When the Nouvelle Vague directors wanted to see a film banned in France, they took the train to Brussels and Ledoux’s domain. The same urge for comprehensiveness informed his efforts to document film history, with filmographies and background information in books published by the Archive. He became a moving spirit of FIAF, the International Association of Film Archives; here you can read about his many accomplishments in that area, as well as his eventual friction with the organization.

His generosity extended to young researchers like Kristin and me, who were welcomed to study films at the Archive. That became the basis of our lifelong friendships with Archive staff and many Belgian cinéphiles, as sometimes chronicled in our blog entries. So grateful was I for Ledoux’s assistance that when I was offered a professorship at my university, I gave it his name. He had just died, and he probably would have protested that he wasn’t worthy; but he has remained an inspiration to us for over forty years.

His generosity extended to young researchers like Kristin and me, who were welcomed to study films at the Archive. That became the basis of our lifelong friendships with Archive staff and many Belgian cinéphiles, as sometimes chronicled in our blog entries. So grateful was I for Ledoux’s assistance that when I was offered a professorship at my university, I gave it his name. He had just died, and he probably would have protested that he wasn’t worthy; but he has remained an inspiration to us for over forty years.

The Archive, now calling itself the Cinematek, has just finished a centenary exhibition devoted to Ledoux. Christophe Piette, organizer of the event, has memorialized it in a lovely multilingual book that gathers reminiscences by Ledoux’s colleagues. There are memoirs by Noël Desmet, Clementine Deblieck, Jean-Paul Dorchain, Hilde Delabie, and Gabrielle Claes, Ledoux’s successor as director. Bernard Eisenschitz, Eric De Kuyper, and P. Adams Sitney offer illuminating appreciations of Ledoux’s contributions. (Sitney’s very full account of Knokke doings is a crucial document in the history of the American avant-garde.) Ledoux’s own voice is represented by a program note for a 1968 science-fiction series. There are many wonderful illustrations–photos, posters, correspondence (Cocteau, Lenica, Akerman). Kristin and I have provided recollections of a man we immensely admired. When you read one of our blog entries on older films, classic or little-known, chances are good that we first saw the film at the Cinematek.

The book is published in a limited edition but is available for purchase at https://cinematek.myshopify.com/en/collections/boeken/products/jacques-ledoux. Every university library with a substantial collection of film literature should acquire a copy!

Anke Brouwers has written a vivid overview of Ledoux’s career for the exposition. Many nifty documents are illustrated.

There are too many citations of Ledoux and the Archive on our site for me to list them. Two extensive ones are “Ledoux’s Legacy” and “Watching movies very, very slowly.” For others, you could try the Search function (using “Brussels”) to find accounts of our many visits.

KIMI: She’s here

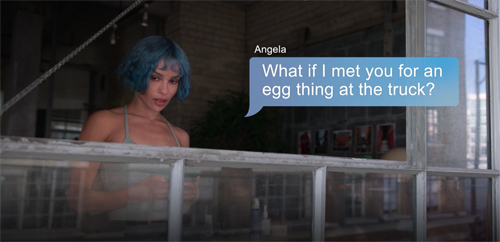

Kimi (2022).

DB here:

Just when I worried that the solitary-woman-in-peril cycle had ended, along comes Steven Soderbergh’s Kimi on HBO Plus. Following on the fine No Sudden Move from last year, his latest effort shows how an imaginative script (from Friend of the Blog David Koepp), elegant direction, an unpredictable score, and an engagingly eccentric central performance (from Zoë Kravitz) can revivify some classic conventions.

Some critics think that when parodies show up, the genre is on the downturn. The streaming release of The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window (2022) might suggest that the cycle based on The Girl on the Train (2016) and The Woman in the Window (2021) had run its course. But actually, parodies can show up at any point in the life cycle of a genre. The Great K & A Train Robbery (1925) didn’t kill off the western, and Spaceballs (1987) didn’t wipe out space opera. So it’s good to know that the presence of Woman in the House Across the Street etc. doesn’t make a straightforward but sophisticated entry like Kimi any the less sparkling.

It depends on what I’ve called the Eyewitness Plot, and I’ve tried in Revisiting Hollywood to show how that emerged from the flurry of creative activity we find in 1940s studio cinema. Here the protagonist sees what may be a crime and asks the authorities to intervene. There’s enough uncertainty about the incident itself, and about the reliability of the witness, to make the police doubt that there’s been a crime. So the protagonist has to investigate–while becoming a target of violence in turn. Rear Window (1954) is the standard example, but it has many predecessors in fiction, film, and radio, notably The Window (1949). A variant relies not on sight but sound: the protagonist hears something of criminal consequence. That alternative is played out in Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) and, later, The Conversation (1974) and Blow-Out (1981).

Koepp and Soderbergh, both connoisseurs of classic Hollywood, understand the power of locking us into the perceptions of the witness while at the same time keeping us aware of the larger context of the action. Rear Window is exceptionally strict in limiting us to what Jeff sees and hears, but even then there is a telltale moment when we’re given information that would seem to contradict his belief that his neighbor has murdered his wife. More common is a balanced narrration that ties us to what the protagonist knows but occasionally strays away to supply backstory and ancillary information–usually, just enough to foster suspense.

That’s enough setup. Major spoilers follow! If you haven’t seen Kimi yet, visit and return.

She looks and listens

Angela Childs lives in lockdown. Not just the pandemic but a traumatic sexual assault has made her afraid to leave her Seattle loft, and more basically resistant to emotional contact. She works from home for Amygdala, a company promoting an Alexa/Siri gadget called Kimi. Unlike the competitors, which rely on machine learning, Amygdala has an army of monitors that track actual user dialogues with Kimi in order to correct its errors. Angela is a monitor, and on one recording she hears, muffled by music and noise, what seems to be a murder. After cleaning up a dense recording and inducing a more experienced hacker to find the user’s entire log of Kimi conversations, Angela discovers a crucial one that seems to lead up to the crime.

Here the official reluctance to believe the witness takes the form of an Amygdala executive’s demand to listen to the recording. When Angela insists that the FBI be present for the playback, the corporation takes steps to silence her. The second large section of the film consists of a prolonged chase and, back in her loft, a final confrontation with the men who committed the crime.

The film’s opening establishes, as a sort of intrinsic norm, the alternation between the wider view of the crime’s circumstances and Angela’s limited perspective. The first scene sets up Bradley Hasling awaiting Amygdala’s IPO, but worried because he’s paying off someone for suppressing information about an unnamed woman.

With our curiosity aroused, the plot can afford to introduce us to Angela and her routines in a more leisurely way. Without the Hasling scene, this stretch would be mostly character portrayal, but it gains keener interest as we must wonder how Angela’s fate will intersect with his. Glimpses of Angela fussily making her bed, brushing her teeth, and exercising on her bike also serve to illustrate how she activates Kimi for music and for computer access.

Just as important are the passages of optical POV that show her at her window scanning her street. She looks across at a family in the building opposite, and then looks up and to her left, where she sees the bearded man we’ll learn is called Kevin. He looks back at her.

She swivels her gaze to another window opposite and sees a closed curtain.

Later on the balcony she looks at the window and this time sees Terry, her casual lover, getting ready for work.

She texts him, and after an external, objective pan shot links the two buildings, she asks Terry if he wants to join her for a breakfast at the food truck down below.

However, she’s afraid to leave the apartment, and her fractured activity is rendered in discordant POV angles. After a shot of her in the shower, we see Terry at the truck, from her usual station point. There’s no lead-in shot of her looking; is she watching from offscreen after the shower, or has the narration worked behind her back, while reminding us of her usual position?

Finally, when she collapses on the floor, unable to leave, we get the same high angle on Terry at the truck, texting her and looking up.

Cut back to her still on the floor. The narration is now operating independent of her vision, but with traces of her viewpoint lingering.

The passage is capped by a shot of her at the window looking down, followed by an optical POV of the food truck, sans Terry.

Another shot of her seals the sequence, but when she pulls away from the window, we get an extra, new angle on her: from outside and above. It’s a fair approximation of what Kevin’s viewpoint on her might be. Yet there’s no shot showing him watching.

The “unclaimed” POV shots that close this scene acknowledge that however much we’re tied to the protagonist’s perceptions, the narration won’t limit us to them–that there is wiggle room to supply extra information, and to imply that our heroine is watched by others. This fluctuating access will become important in the crosscutting that provides the film’s climax.

She flees and fights

The fusion of external viewpoints and subjective ones continues in different ways later. When Angela plays the recordings of the attack, Soderbergh gives us her mental imagery–first as blurred cutaways, then as superimpositions. She’s imagining the assault. Later we’ll learn she has been a rape victim herself.

We’ll later discover that the faces of the murderers are those of the thugs who will pursue her. Yet she hasn’t seen them yet, so she can’t plausibly be visualizing them in the scene.

This is an innovation, I think. In the Forties and since, if these visualized images were to accompany the playback, the faces of the killers would have been indiscernible. Soderbergh is willing to violate plausibility in order to gain economy (introducing us to the thugs) and to continue his initial strategy of rendering subjective experience while also adding information for us.

A milder version of the tactic will be used in the climax, after Angela is captured and lying semi-unconscious in the van. We see her awake and apparently listening to the thugs’ dialogue, while superimpositions suggest the passage of the van through the neighborhood.

Incidentally, these are good examples of the persistence of “Impressionist” cinema techniques from the silent era. Soderbergh had made use of them in Unsane (2018), another film about a woman in peril.

Apart from the prologue showing Hasling’s phone call, the film’s first stretch is confined to Angela’s loft. It’s a classic “bottle” situation, a premise that Koepp is fond of. (Cf. his script for Panic Room, 2002.) It’s Angela’s sympathy for the victim of the crime that propels her out of her bubble into the wider world. Here Zoë Kravitz’s performance takes on a new dimension.

In her loft she’s clipped and brusque, dominating everyone she talks to. Her vulnerability, though, is suggested by her obsessive hand sanitizing. Emphasized by her waving her hands to dry them, it becomes practically a nervous tic.

Once outside, she scoots along, arms jammed to her side, head buried in her hoodie, and body as stiff as Max Schreck’s. She tries to be as locked-in outdoors as she is indoors.

Soderberg compensates for her rigidity with camera technique that’s liberated from the confines of her loft. As Manohla Dargis points out in her review, now the film becomes a procession of canted angles and hurtling camera moves, swooping around her and trying to keep up.

Once back in the loft, however, the framing gets poised again and we’re subjected to a precise exercise in suspense. Close-ups and abrupt changes of angle provide exactly what we need to see at each instant.

And things planted quietly in the opening, particularly Angela’s knowledge of building construction, become crucial to her survival. Kimi proves to be a lifesaving sidekick, proving Hitchcock’s dictum concerning Jeff’s use of flashbulbs to save himself in Rear Window: you should use everything you’ve put into your scene.

One nice felicity: You might expect that Terry would turn out to be the “helper male” of so many women-in-peril plots (e.g., the Joseph Cotten character in Gaslight, 1944). Prototypically, this character rescues the protagonist and provides romantic interest for the future. Koepp’s screenplay shrewdly sets Terry up for this role when Angela looks outside during the gang’s siege and sees Terry’s apartment empty.

Later Terry is shown in a street-level, objective shot, walking to Angela’s building. This violation of the intrinsic POV norm suggests an impending rescue. But that prospect is canceled when he stops as if remembering something and turns back.

He does arrive, but too late to help. Terry’s expression as Angela calls 911 is a perfect capstone for the scene. The same wit flashes out of the epilogue, which suggests she’s broken out of her shell, but she still prudently uses sanitizer.

The domestic suspense thriller focused on a female protagonist remains a popular genre of novels. I devoted a chapter to it in my forthcoming book Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. There haven’t been many film adaptations of them since The Woman in the Window, but maybe the neo-Gothic The Girl Before (2021) will unleash more. In the meantime, I’m glad that Koepp and Soderbergh have found ways to give the conventions brisk new life.

David Koepp remarks: “You’re right about the lingering effect of 40s cinema, as you and I have discussed many times. I’d say Sorry, Wrong Number was the direct antecedent here. . . I mean, the party line in Sorry, Wrong Number is basically the Alexa of its time, no?” Interesting in this connection is that the lengthy survey of Angela’s loft in the epilogue shows Kimi no longer there.

Another grace note: KT wondered if the precariously balanced kombucha bottle is psychologically revealing. It turns out to be the consummation of a moment from an earlier Koepp film.

The bottle on the edge of the counter — that was me making good on a setup I did in Secret Window, fifteen years ago. Seriously. There’s a shot in there where Johnny’s character, in a state of high anxiety and agitation, sets a glass down on his kitchen counter hastily, and doesn’t notice it’s only half on the counter. We did seventeen or twenty takes to get exactly the right gravity-defying balance on the edge. It was a pretty literal visual metaphor — you know, he’s on edge.

Thing was, in post-production I realized I had put in a perfect setup, but never paid it off. Why not have the glass fall and smash twenty minutes later, when we’re least expecting it?? Wished I had, never did.

So I used it again in Kimi, but with the (to my mind) required payoff, and at a moment of high tension. So, Angela, in her argument with Terry, is highly agitated, and smacks the bottle down on the counter carelessly, not realizing how close it is to the edge. (The KT hypothesis proves correct!) Angela forgets about it. So do we. Ten minutes later, when we’re all keyed up about something else, SMASH!

Thanks to David for corresponding.

The Hitchcock remark is this: “Here we have a photographer who uses his camera equipment to pry into the back yard, and when he defends himself he also uses his professional equipment, the flashbulbs. I make it a rule to exploit elements that are connected with a character or location. I would feel that I’d been remiss if I hadn’t made maximum use of those elements” (Truffaut/Hitchcock, rev. ed. 1983, 219).

Kimi (2022).

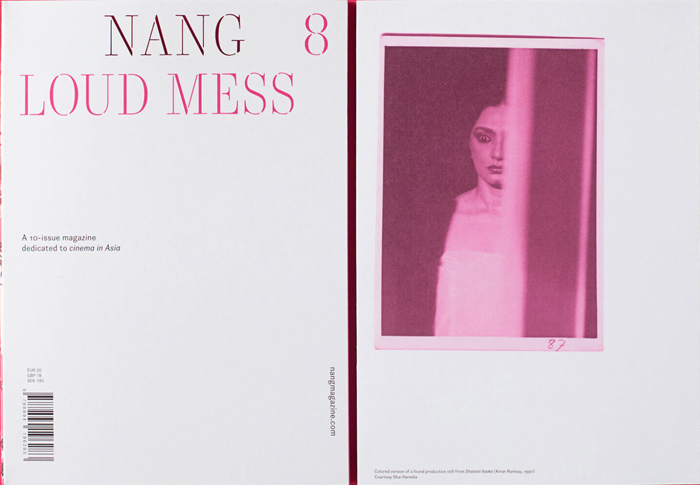

An elegant path into modern Asian cinema

DB here:

Nang is an anomaly in today’s film culture. A limited-edition magazine published only in hard copy, it carries no advertising, film reviews, or festival reports. It’s printed on exquisite, environmentally-sensitive paper, with binding that allows it to open and stay flat. It radiates casual elegance, and it’s devoted to modern Asian filmmaking. A preface explains:

Thanks to a unique group of guest editors and contributors, Nang broadens the horizons of what the moving image is in Asia, engaging its readers with a wide range of stories, contexts, subjects and works connected by the cinema.

This sounds fairly conventional, but Nang’s mission is also “to expand (the idea of) what a cinema magazine can be today.” This ambitious goal comes from this remarkable declaration of principles by Publisher and Editor-in-Chief Davide Cazzaro. He reveals Nang’s deep commitment to analog publishing and to quality, highly diversified content.

Cazzaro’s statement only hints at the riches within every issue.There are historical studies, such as Debrashree Mukherjee’s article on female barristers in Mumbai cinema and Chew Tee Pao’s account of archiving the Singapore feature Medium Rare. Experts such as Aaron Gerow, Jasper Sharp, Sam Ho, Victor Fan, Noel Vera, Darcy Paquet, Mark Schilling, and Goran Topalovic offer incisive, in-depth pieces. But this is no musty academic journal. There are cartoons, paintings, collages, and other forms of graphic art. There are poems and short stories as well: issue no. 3 is devoted to fiction.

Nang is passionately dedicated to honoring and understanding the creative process of filmmakers. Given my proclivities, I remain in awe of issue no. 5,”Inspiration,” which includes writings by and interviews with Mira Nair, John Woo, Jia Zhangke, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tsui Hark, and many other directors. Me being me, I was especially keen to find out the Nair planned Monsoon Wedding by laying out “a sea of index cards” on her bed to keep the plot lines balanced.

No less revelatory is no. 6, “Manifestos,” which include previously untranslated manifestos from modern Asian film movements. There are documents from Taiwan, Indonesia, South Korea, India (Satayajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak), the Philippines, and many other locales. There’s even serious consideration given to Kim Jong Il II’s 1973 On the Art of the Cinema, an effort by the North Korean dictator to specify the demands of a communist cinema. Each entry is graced by photos of hands cradling rocks.

Other issue topics are less clear-cut. “The Scent of Boys” is largely devoted to same-sex cinemas, but through an unusual route: writers were asked to reflect the sensory and sensual aspects of bodies and their interactions on the screen. Critics, historians, and filmmakers reflect on figures and films that have shaped their sensibilities. Issue no. 8, “Loud Mess,” is about “the power of transgression” in many dimensions–horror, eroticism, sound.

I really can’t do justice to the splendors on display in Nang. Go to the Blog page for a potpourri of articles and background on the editors. One concession to the digital realm: A ten-year look back at Nang. Most back issues are still available; go here to see the possibilities and browse some pages. Bargain-priced too, considering that these are in effect art books. But hurry: issue no. 9 is already out, and the next one is said to be the last.

Nang is an energetic, imaginative effort to open up new aspects of Asian filmmaking. Davide Cazzaro and his guest editors have given us a true labor of love–obviously, their love of Asian cinema, but also an acknowledgment of what many of us feel: This is one of the world’s greatest film traditions.

Thanks to Goran Topalovic for calling my attention to Nang and Davide Cazzaro for providing me sample issues!