Archive for the 'Film technique: Music' Category

Oscar’s siren song: The revenge

King Richard

The Oscars are upon us again. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences may have decided that “Music (Original Score)” is one of the categories not important enough to show live along with the rest of the awarding of the golden statuettes. We, of course, think this is absurd. (Will the Oscar ceremony gain a single extra TV viewer through this tactic?)

We welcome back our friend and colleague Jeff Smith to continue his annual comments and predictions concerning the nominees in both musical categories: song and original score. This year he has, if anything, outdone himself in providing insights into the historical contexts and the formal qualities of the ten nominees.

‘Tis the season to pass out little gold men to people in gowns and tuxedos. This year’s Oscar ceremony is scheduled to take place on Sunday night, March 27th. And this is about the time when I offer my annual assessment of the nominees in the music categories.

The title I’ve given this blog post might appear to represent a failure of imagination. After posting the first of these surveys, I opted for a sequelitis motif by using Roman numerals and corny words like “Return.” Yet this year’s sequel title seems all too apt. The producers of the Academy Awards have been winnowing away the amount of airtime given to the music awards in the past two years. They no longer present all five of the Best Original Song nominees as part of the broadcast. This year the award for Original Score will be prerecorded before the broadcast and the winner announced in between other, presumably more important awards.

If the Academy Awards doesn’t seem to care about these categories, then why should I? Well, because as a scholar and educator, this is what I do. Consider this blog post the petty revenge of someone who believes these categories still matter, even if the organization sponsoring the awards doesn’t seem to think so.

In the case of the award for Best Original Score, there will be some bitter irony in the fact that we’ll never see the faces of the composers on the big five-way split screen used to show nominees. But we’ll hear their scores played as walk-up music if Penelope Cruz wins for Best Actress. Or if Greig Fraser wins for Best Cinematography. Or Encanto wins for Best Animated Film. Or Jane Campion wins for Best Director. Or Adam McKay wins for Best Original Screenplay.

At the end of each award preview, I’ll make an educated guess as to who the winner of the category will be. All the usual caveats apply. These predictions are not intended for wagering purposes, I offer the usual disclosure that my predictions over the years typically yield one right and one wrong. (It’s up to you to figure out which is which.)

Lastly, a warning of some spoilers. I do my best to try to avoid giving away too much information about a film. But sometimes it is unavoidable if you want to get into the nitty gritty of the choices composers make in how they score their films.

The Susan Lucci of songwriting

Last month, Diane Warren earned her 13th Oscar nomination for Best Original Song, the most by a woman in any category without a win. This isn’t the most, though, in the music categories as composers Thomas Newman and Alex North both earned 15 nominations for Best Score without ever taking home Oscar. Last April, Warren told Billboard that she the old saw about it being “nice to be nominated” was true, but that she really would like to finally win an Oscar. Said Warren, “I’m like a sports team that has lost the World Series for decades. This is 33 years since my first nomination.” Warren’s record begs comparison with soap opera star Susan Lucci, who earned 18 Daytime Emmy nominations for her role as Erica Kane on All My Children before finally winning the award in 1999.

Warren’s current nomination is for her song, “Somehow You Do,” which is featured in Rodrigo Garcia’s drama about opioid addiction, Four Good Days. Sung by Reba McEntire, Warren’s number is a countrified version of the sort of power ballad that the tunesmith has specialized in for decades. The first verse is modestly arranged for two guitars, one an acoustic and the other pedal steel. The song gradually adds more texture as it nears the chorus, with the bass adding some bottom end and a chorus punching up McEntire’s lead vocal.

The second verse continues to build with the addition of a drum kit that firmly establishes the song’s 6/8 meter and slow tempo. The song’s bridge introduces a contrasting melody and roughens up the sweetness of McEntire’s voice with some pulsating power chords played by an electric guitar. This prepares for the requisite key change as the song shifts to the final verse and chorus. The tune reaches its emotional peak here and then gradually tapers down. A brief coda returns us to the spare sound of McEntire’s voice accompanied by an acoustic guitar.

The song is very well-crafted if a bit by the numbers. It is a testament to Warren’s mastery of her craft that she finds new ways to enliven the venerable AABA structure of classic songs and fit them to the dramatic needs of the films she works on.

Yet Warren’s chances of winning seem to be hampered by a couple of factors. If you asked yourself, “What is Four Good Days?”, you are not alone. The film garnered little attention from critics and fans, earning less than $900,000 during its theatrical release. Moreover, although McEntire is a huge star in the world of country music, that probably won’t cut much ice for voters in the Academy music branch who represent a different industry demographic.

There seems little doubt that Warren has a dedicated following within the music branch. However, although it is big enough to consistently yield nominations, it isn’t large enough to deliver the big prize. Warren likely will have to content herself with “It’s nice to be nominated.” If she starts to feel too downhearted, Warren can console herself by looking at her royalty statements for “Rhythm of the Night.” Or “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing.” Or “How Do I Live.” (You get the idea…)

The Legends (and I don’t mean John, Chrissy, Luna, and Miles)

The next two nominees are among pop music’s biggest icons, representing more than ninety years of combined experience in the biz. A bit surprisingly, though, both artists also are first-time Oscar nominees.

First up is the man who epitomizes Northern Soul: Irish singer and songwriter Van Morrison. Morrison is nominated for “Down to Joy” from Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast. Like Branagh, Morrison was born and raised in Belfast. He also has been closely associated with the city throughout his career, receiving the monikers of “the Belfast Cowboy” and “the Belfast Lion.” The early peak of Morrison’s career also coincides with the onset in 1969 of “the Troubles” depicted in Belfast. Besides “Down to Joy,” Branagh selected eight other Morrison tracks for the film’s soundtrack, many of them lesser-known tracks like “Caledonia Swing” and “Carrickfergus.” By digging deep into Morrison’s catalog, Branagh is not only able to provide a musical biography of his childhood, but also indicates how deeply Van the Man’s music was woven into the fabric of everyday life in Belfast.

Morrison’s “Down to Joy” also shows the durability of AABA form, albeit in this case channeling the sound of his early mid-tempo rockers like “Caravan” and “Domino.” The latter recordings are among the songs that would cement Morrison’s status as a Celtic interpreter of the revue style of sixties soul music, especially the Stax sound epitomized by singers such as Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave, and Otis Redding. Morrison based his entire career on melding those influences with more native elements of Irish folk music. For nearly sixty years, Morrison has demonstrated that the idiom of sixties soul seems almost timeless, an impression confirmed by even more modern practitioners, like Sharon Jones & the Dap Kings or Nathaniel Rateliff & the Night Sweats.

Appearing over the end credits, “Down to Joy” neatly encapsulates the overall tone of Belfast and its mix of nostalgia, melancholy, and hope. At the end of Belfast, young Buddy and his family have been displaced by “the Troubles,” forced to relocate by threats of IRA retaliation. Their journey to England is colored by the pain of family separation. Yet it also represents a horizon of new possibilities. “Down to Joy” reflects that latter sentiment with lyrics describing a new morning after a dark night, and the glory and gratitude expressed through Buddy’s child-like naivete.

So, what are the chances that Van the Man wraps his hands around a small golden dude? Not very good, if you ask me.

Don’t get me wrong! Morrison albums of the late sixties and seventies – Astral Weeks, Moondance, Tupelo Honey, Saint Dominic’s Preview – are stone cold classics. It’s Too Late to Stop Now is among the finest live albums ever recorded. Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl” is my wife’s very favorite song ever!

I’m a Van fan, but his public statements about the United Kingdom’s Coronavirus restrictions have probably killed his chances of winning an Oscar. If younger members of the Academy know Morrison at all, it is likely as a conspiracy crank who is now recording with equally obnoxious anti-vaxxer Eric Clapton. I just can’t see Academy voters giving Morrison a platform to air his views on social distancing and lockdowns. If they did, it would produce the kinds of news clips and headlines that the Academy would like to avoid. Just imagine the public response to an acceptance speech in which the boos from the crowd rain down on the winner. I imagine that a lot of folks in the music branch just can’t bring themselves to vote for Morrison in the current political landscape. And, even as a lifelong fan, I can’t really blame them.

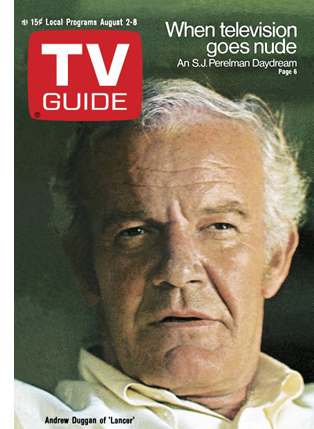

The third nominee for Best Original Song is “Be Alive” by DIXSON and Beyoncé Knowles Carter. The song appears in the end credits of King Richard, the biopic about Richard Williams, the father of tennis phenoms Serena and Venus. The tone of the music and lyrics succeed in doing something the film itself struggles to do, namely give voice to the two women who end up rewriting the record books of professional tennis.

In contrast, King Richard casts Williams the elder as a Svengali figure shepherding his young prodigies into the world of big-time sports. He acts as the girls’ agent, manager, coach, and protector, shielding Serena and Venus from the sorts of predations that characterize an industry with a bad reputation for chewing up and spitting out young talent. The lyrics of “Be Alive” speak to the family’s sense of fierce independence and Williams’ own “bootstrap” mentality. This is evident in couplets like:

Couldn’t wipe this black off if I tried

That’s why I lift my head with pride

Later, Beyoncé sings the praises of sisterhood, a theme that can be heard in some of her biggest hits, such as “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)” or “Independent Women Part I,” the latter recorded as a member of Destiny’s Child.

With its steady marching tempo borrowed from the Doors’ “Five to One” and Beyoncé’s soaring vocals, “Be Alive” bespeaks a mood of strength and defiance. Yet, it isn’t as well placed as some of the other songs in the category and, unlike many of Beyoncé’s popular records, it also isn’t the kind of earworm that lights up record charts. “Be Alive” peaked at #40 in Billboard’s Hot 100, likely a disappointment considering how well King Richard has performed in other audience metrics.

Come Sunday, I suspect that Beyoncé will likely go home empty handed. Like Diane Warren, she’ll need to console herself with the mantra “It’s nice to be nominated” and the many other Grammys, ASCAP, Billboard, BET, MTV, and American Music Awards that line her trophy case.

The Young Bloods

The final two nominees had big years in the world of entertainment in 2021. An Oscar would put a capper on a period of creative ferment that’s the envy of most singers and songwriters. Yet, for these two performers, it just seems like another day at the office.

Lin-Manuel Miranda received his second Oscar nomination for “Dos Oruguitas,” one of several songs he wrote for the Disney animated musical Encanto. The song is performed by Columbian singer Sebastián Yatra and appears in a flashback that dramatizes Abuela Alma’s tragic backstory. As a young woman, Alma, her husband Pedro, and their triplets attempt to escape their village after war breaks out. During their journey, they are beset by armed horsemen. The refugees scatter, but Pedro is killed when he halts the charging caballeros, presumably to ask for mercy for himself and his family. A candle Alma is holding protects the rest of the group, and its magical properties transform their future home into the “Casita,” a fantastic space where its denizens are revealed to have supernatural abilities and the house has a mind of its own.

The sequence itself is reminiscent of similar moments from films made by Disney’s friendly rival, Pixar. The montage that encapsulates an entire life in a couple of minutes of screen time recalls the opening of Up (2008) which depicts the long, happy marriage of Carl and Ellie until her illness and untimely death. The song that accompanies a flashback explaining the source of a character’s trauma and grief is also seen in Toy Story 2. Cowgirl Jessie relates how she once was her owner Emily’s favorite doll, but ends up forgotten and left behind when Emily grows up. This is all set to the strains of Sarah McLachlan’s “When She Loved Me.” The montage from Encanto nicely fuses together both these narrative devices but gives them a Latin pop spin.

Like “Somehow You Do,” “Dos Oruguitas” begins quietly with a brief introduction played on an acoustic guitar. The slight syncopation of the guitar figure, though, gives it a bit of Hispanic flair. As Yatra’s voice enters, the song’s chord structure follows a chromatically descending bass line, a device that heightens the harmonic tension until it circles back to the tonic. The tune pauses briefly as Abuela confesses her guilt for forgetting what the purpose of the magic was for. Mirabel reassures her that the Madrigal family’s entire livelihood is due to the earlier sacrifices the Abuela made and the suffering she endured. When they embrace, “Dos Oruguitas” kicks back in with a slightly faster tempo and with fuller orchestration that includes strings, percussion, a chorus, and a harp. With the rift between Alma and Mirabel healed, the Madrigals band together to rebuild the “Casita.” The harmony created by the restored family bonds allows it to regain its sentient properties.

As an Oscar nominee, “Dos Oruguitas” has a lot going for it. It accompanies a very emotional scene of intergenerational reconciliation. It is a featured track on the Encanto soundtrack, which has spent the past nine weeks atop Billboard’s Top 200 album chart. And Lin-Manuel Miranda is on a roll having served as the director of Tick, Tick…Boom!, the musical biopic of Rent composer Jonathan Larson, and as the producer of In the Heights, the screen adaptation of Miranda’s own hit Broadway play.

Perhaps the only thing working against it is the fact that it’s been overshadowed by another song from Encanto. “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” is a certified pop culture sensation, spending five weeks as the #1 song on Billboard’s Hot 100, accumulating more than 300 million views on Vevo, and featured in 21 different languages on Instagram. Did Disney submit the wrong song for nomination? Maybe, but “Dos Oruguitas” still might been benefit from the reflected glory of its more popular sibling. This and the fact that Encanto is up for some other major awards have kept Miranda among the frontrunners.

The last nominee is the title song from the most recent entry in the venerable James Bond series, No Time to Die. The tune is performed by Billie Eilish and written by Eilish and her frequent songwriting partner, brother Finneas. Like Miranda, 2021 has been a good year for Eilish. Her new album Happier Than Ever topped the charts in 26 countries across the globe, including the US. It also earned two Grammy awards and landed on several year-end “best of” lists. In addition to her music, Eilish also appeared in two films: a concert film featuring songs from Happier Than Ever and a “behind the scenes” documentary distributed by Neon and Apple TV+ called Billie Eilish: The World’s a Little Blurry.

In some respects, Eilish seems like an exemplary contributor to the amazing catalog of songs written for the Bond canon. She is an immensely popular artist. She is also someone who could update the template for the series by adding emo, dream-pop, and electro-pop touches to the usual Bond formula.

In other respects, though, Eilish represents something of a departure from previous Bond songstresses. When one thinks of iconic Bond songs, one thinks of tunes like “Goldfinger,” “Diamonds Are Forever,” “Licence to Kill,” “Goldeneye,” “The World is Not Enough,” “Skyfall,” and “Another Way to Die.” What do these songs all have in common? They are all sung by women with big voices, belters like Gladys Knight, Tina Turner, Adele, Alicia Keys, and the two Shirleys: Bassey and Manson. In contrast, Eilish is known for a much softer style of singing: hushed, sensitive, and intimate. That seems fitting for a performer whose best-known album was inspired by lucid dreaming and night terrors. Yet it seems less well-suited for an almost mythic film character defined by his swagger, toughness, and even a streak of cruelty.

Yet, if there was moment to rethink the traits of the typical Bond song, this was certainly it. In retrospect, the selection of Eilish was a masterstroke by the Bond brain trust led by Barbara Broccoli, the current head of Eon Productions. As the last film to feature Daniel Craig as James Bond, No Time to Die not only caps off his five-film arc, but also serves as a reflexive meditation on the series as a whole. At one level, the explicit meaning of No Time to Die is both simple and banal: everyone dies. Yet, by making references to several earlier films in the series, the accumulated weight of intertextual resonances invests the many deaths that occur in No Time to Die with an unusual sense of depth and gravity.

No Time to Die begins with a scene where Bond visits the tomb of Vesper Lynd, the fellow agent featured in Casino Royale who helps Bond defeat the evil Le Chiffre. Lynd and Bond fall in love, but she proves to be a double agent working for a rival operative. At film’s end, Lynd sacrifices herself when she drowns in a locked elevator car that has submerged.

M then reveals that she was an unwilling accomplice, a victim of blackmail after her previous boyfriend was abducted and threatened.

Bond’s pilgrimage to Lynd’s grave presages several additional deaths in the film. Bond’s best friend, CIA Agent Felix Leiter, and his mortal enemy, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, are killed in separate incidents. Even Bond himself perishes in the climax of No Time to Die. He sacrifices himself to foil a scheme by Lyutsifer Safin to unleash a bioweapon upon the world that is transmitted by touch and kills its victims based upon their DNA. After a missile strike is launched against Safin’s compound, Bond stays behind to assure that the silo’s blast-proof doors stay open. Bond’s gesture that not only saves the world but allows his current paramour, Madeleine Swann, and the young daughter he never knew he had, to safely escape the island.

Given how much of No Time to Die is pervaded by a sense of grief and sorrow, the decision to include a title song reflective of the film’s solemnity and melancholy makes perfect sense. Like some of the other nominees, Eilish’s tune begins slowly and quietly with a piano plunking out a repeated four note motif accompanied by strings and low brass. Eilish intones the first lyric, “I should have known” in a sung whisper. The serpentine melody unwinds through the verse and chorus, eventually taking Eilish into the upper range of her soprano on the lines:

Fool me once, fool me twice

Are you death or paradise?

You’ll never see me cry

There’s just no time to die

Just as the chorus ends, a thunderous bass chord enters, and the opening four note motif returns. The song continues to build, and more instruments are added as the song reaches its second chorus. Our four-note motif returns once more, but this time played in full orchestral splendor by the strings and the full brass section. The musical bombast ultimately fulfills the remit of other classic Bond songs. Eilish even follows suit by loudly belting out the chorus, revealing a power and huskiness to her voice that most of her fans probably hadn’t heard before.

“No Time to Die” finishes with a coda that returns to the sparse arrangement of the tune heard at the start. Eilish also goes back to the shivery murmur that is her stock in trade for one last iteration of the chorus’ last two lines.

No Time to Die larger themes of love, death, grief, and martyrdom presented a special challenge. Billie and Finneas rise to it beautifully. Moreover, the Eilishes also cleverly incorporate musical elements that evoke the harmonies and tonalities of John Barry’s best-known scores in the series. The four-note motif that serves as a spine for the song sounds like it could have easily been drawn from From Russia with Love, Goldfinger, or Thunderball. They also conclude the song with an electric guitar strumming an EmMaj9 chord, the so-called spy chord that Vic Flick plays at the end of the famous James Bond theme that started it all.

Does this mean that “No Time to Die” is the odds-on favorite to win? Perhaps, but it also seems to be overshadowed by another song, much as “Dos Oruguitas” was. In this case, the song was written for a completely different Bond film and mostly functions as an Easter Egg for die-hard fans of the series. It is “We Have All the Time in the World,” which was written by John Barry and Hal David and performed by Louis Armstrong over the end credits of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1968). Notably, the song appears just after Bond’s new bride, Tracy, has been killed in a drive-by shooting by Blofeld and his assistant, Irma Bunt. It is yet another evocation of death in No Time to Die with Tracy, like Vesper Lynd, implicitly included in the film’s mounting body count. Notably Hans Zimmer’s score for No Time to Die incorporates the melody to “We Have All the Time in the World” in three of the cues he wrote for the film. Indeed, long-time fans like me might well recognize the older Bond song in Zimmer’s score much more readily than the new one specifically written for it.

Prediction for Best Original Song

An Oscar would confer EGOT status on Lin-Manuel Miranda, a distinction held by just a handful of other entertainment luminaries. In fact, because Miranda also won a Pulitzer Prize for Hamilton and a MacArthur Genius Award, an Oscar would place him in entirely unique category. Say hello to the MacPEGOT.

Yet, although an award for “Dos Oruguitas” would make history, recent Oscar ceremonies have favored Bond songs. Adele won for “Skyfall” in 2013. Sam Smith repeated the feat with “Writing’s on the Wall” in 2016. “No Time to Die” also has already won a Grammy, a Golden Globe, and more than a dozen awards from prominent critics’ societies. Eilish is also a newly minted pop star, whose personal story is the kind of underdog narrative that Oscar voters seem to like.

If you are looking for a dark horse in the field, you might consider “Be Alive.” (Although when would you ever consider Beyoncé a dark horse for anything?) But I am sticking with the favorite. On Sunday, I expect Eilish to win. It is the clubhouse leader in terms of the betting markets and also my personal favorite among the field.

An ode to the new cleffer

One of the first things you might notice about this year’s slate of nominees for Best Original Score is the relative absence of the “usual suspects” in the music branch, such as Thomas Newman, Alexandre Desplat, or John Williams. Between them, these three composers have received a total of 78 nominations. Admittedly, only one of the five nominees this year – Germaine Franco – is a first timer. However, aside from Hans Zimmer’s twelve previous nominations, none of the other composers has received more than four.

Franco’s nomination is significant for other reasons. In February, she became the sixth woman nominated for Best Original Score and the first Latina. The field has a decided international flair with nominees from Britain, Germany, and Spain joining two Americans.

Of the five nominees, Alberto Iglesias’ music for Parallel Mothers (above and at bottom) comes closest to the style of a classical score. Yet it also presents a slight departure from those norms in its use of a chamber orchestra with most cues arranged for strings, piano, and the occasional wind instrument. Some feature the strident bowing style associated with Bernard Herrmann’s famous score for Psycho (1960). Others create lush combinations of strings and solo piano, an approach reminiscent of Frank Skinner’s music for older Universal melodramas like All That Heaven Allows (1956).

If that sounds a bit odd, it shouldn’t. Alfred Hitchcock and Douglas Sirk have been prominent influences on Pedro Almodovar’s cinema over the years. Parallel Mothers is the thirteenth film that Iglesias has scored for the great Spanish auteur. The composer admits that Almodovar’s films are always rooted in melodrama. But Parallel Mothers also had the generic trappings of a thriller, and his music strived to infuse scenes of psychological intimacy such that they crackled “with energy and light.” Iglesias also sought to accentuate the protagonists’ intertwined lives at a macro-level, using parallel musical structures to underscore how Ana enters and exits Janis’ life at several points in the film.

Iglesias is a four-time nominee and his score for Parallel Mothers is among his best. But I fear this is not his year. Parallel Mothers is among the biggest longshots in the Oscar betting markets not only for Iglesias in the Best Score category but also for Penelope Cruz as Best Actress. Moreover, the fact that Spain snubbed Parallel Mothers when submitting its nominee for Best International Feature Film also doesn’t bode well. Iglesias is once again a very deserving nominee whose work is likely to be overlooked in a highly competitive field.

Stretching the classical style: Incorporating novel idioms

Nicholas Britell earned his third Oscar nomination for Don’t Look Up, Adam McKay’s acrid satire of contemporary politics and media. The film’s dark humor and its apocalyptic conclusion undoubtedly posed a conceptual challenge for Britell. How do you preserve the comedic qualities of the story while still respecting the existential crisis that hints at larger issues around climate change, COVID, and the increasing distrust of science and medicine? As Britell acknowledges, he was “unprepared for the wild ride” that viewers experience over the course of the film. Britell’s solution? A hyperbolic paean to science, a smattering of wacky electronic sounds, some rollicking big band jazz, and garage-band style Farfisa organ.

In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Britell notes that two cues were especially important in articulating the overall concept for the score. Even before production had wrapped, Britell created a demo cue entitled “Overture to Logic and Knowledge” that McKay played on set to enable the cast to get in the right frame of mind.

The piece unfolds as a canon performed on a piano that’s been recorded with heavy reverb. After the statement of the initial theme, Britell interweaves additional voices in contrapuntal harmony, approximating the sort of mathematical precision one associates with Bach fugues. Afterward, Britell then tried to suss out what the opposite of that compositional style might be, eventually landing on big band jazz. The idiom is evident in the film’s main title, which features walking bass, a simple brass and bass saxophone riff, and a soaring trumpet obligato. Another cue – “It’s a Strange Glorious World” – reprises that big band style, yet further estranges the viewer from the serious global crisis dramatized in Don’t Look Up with the use of banjo and toy piano for instrumental color.

Britell saves his most savage musical satire for a theme written for Peter Isherwell, the billionaire tech genius played by Mark Rylance.

The composer arranges the theme for celestas, toy pianos, Farfisa organ, and bass synthesizers. These instrumental colors suggest Isherwell’s childlike faith that new technology can solve all of humankind’s biggest problems. Of course, Isherwell exudes this relentless optimism to mask his real intentions. Isherwell proposes a foolhardy mission to try and capture the streaking comet rather than deflecting or destroying it. He does so to feed his corporate greed as the comet possesses rare minerals that Isherwell hopes to harvest for use in his production of microchips.

Britell’s score displays incredible musical sophistication even as it is asked to underscore scenes that occasionally seem silly or in which the satire seems all too crude. That being said, I have some doubts that it will win for Best Original Score. This is not to gainsay Britell’s extraordinary ingenuity in devising his music. Rather, it is just the brute reality that other films have better odds in what seems to be a close race.

Germaine Franco’s music for Encanto also pushes the bounds of the classical score. In this case, though, it does so by incorporating various styles of Latin pop music rather than using big band jazz. To be sure, there was a strain of this type of composition in earlier eras, Think, for example, of the music written by Henry Mancini, Nelson Riddle, and Quincy Jones for films of the 1960s. That music, though, reflected the predominant Latin pop styles of the period, which included congas, rhumbas, cha-chas, sambas, and bossa novas.

In contrast, Franco drew upon a different repertoire of Latin rhythms to fashion her score for Encanto, including some folk music styles specific to the film’s Colombian setting. These not only include more familiar idioms like salsa, but also more modern developments like reggaeton. The latter is a style that originated in Panama in the 1990s and mixes hip-hop beats with Jamaican riddims. It rapidly spread through Spanish-speaking countries in the Caribbean.

In Encanto, reggaeton can be heard in Luisa Madrigal’s big number, “Surface Pressure.” The song, of course, was written by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Franco then incorporated the style into certain cues to ensure a strong sense of unity between the mood and vibe of the songs and those of the score.

Other cues, however, are written in folk styles native to Colombia with Franco once again taking her cues from the rhythms of Miranda’s songs. Encanto’s opener, “The Family Madrigal,” is an up-tempo vallenato song played in standard 2/4 meter. It features marimba, three-button accordion, and guachara, a Colombian percussion instrument played by rubbing a fork over a wooden, ribbed stick. Mirabel’s “I want” song, “Waiting on a Miracle,” uses bambuco rhythms. It unfolds in a fast triple meter characteristic of the idiom. As the only song featuring this rhythm, Miranda used it to further underline how Mirabel feels separated from her family due to her lack of a special gift for magic.

Perhaps Franco’s most important gesture, though, was using cumbia rhythms to underscore Mirabel’s movement. Cumbia is popular style throughout South America but has its origins among enslaved African populations on the coasts of Colombia and different Caribbean nations. It uses a clave rhythm common in Afro-Cuban music. As the style spread throughout Colombia in the early 1900s, musicians incorporated indigenous drums and wind instruments, including tambora, llamador, and gaitas. As Franco has noted in interviews, she uses the cumbia to accompany Mirabel’s first entrance into the “Casita.” From that point on, according to Franco, “The rhythm of the cumbia becomes the forward motion of her trying to find a solution to the problem.”

I suspect Franco’s fellow composers in the music branch are as impressed as I am by her attention to details of rhythm and orchestration. To get the precise tone color needed for some of these Latin pop and folk styles, Franco had a special marimba native to the Choco rainforest region of Colombia disassembled and shipped to her in parts. After it was put back together, Franco played the marimba herself, two mallets in each hand.

Encanto isn’t the favorite to take home the prize for Original Score. But if you’re looking for a potential surprise on Sunday night, Franco seems to be in the best position to pull an upset.

Rock of the Westies

Many pop music fans know Jonny Greenwood from his work as a songwriter and lead guitarist in the British rock band, Radiohead. Greenwood, though, has also established a considerable reputation as a film composer. He is perhaps best known for his work with director Paul Thomas Anderson, who has collaborated with Greenwood on his past five projects. Beginning with There Will Be Blood (2007), Greenwood went on to score The Master (2012), Inherent Vice (2014), Phantom Thread (2018), and Licorice Pizza (2021).

In February, Greenwood earned his second Oscar nomination for Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog. Much like the rest of the film, Greenwood’s score works against many of the conventions of the classic Hollywood Western. Many studio-era oaters developed their scores around orchestrated versions of tunes in the cowboy songbook or around Coplandesque rhythms and harmonies. Both these approaches strived to evoke the majesty of the films’ visuals, which often featured mountain vistas, endless prairies, and sunlit horizons.

Instead of looking to the “sweeping strings” style used in older Westerns, Greenwood was inspired by the atonal brass music that was used in old Star Trek episodes to underscore the exploration of unknown planets. When Peter ventures into the mountains and discovers a dead cow, Greenwood accompanies these scenes with a dissonant French horn duet to highlight the strange and forbidding quality this has on the impressionable teenager.

Similarly, instead of a big string sound, Greenwood opted for smaller ensembles, occasionally writing things for six cellos or four violas. Greenwood also plucked strings of a cello as a correlate for Phil’s onscreen banjo playing. Here again, the goal was to create a tone color that seemed just slightly off, emphasizing microtonal inflections to create a sound that was somber yet sinister.

Phil’s banjo playing also furnishes one of the most memorable scenes in The Power of the Dog. Peter’s mother, Rose, initially seems ill at ease after coming to live with George and Phil on the brothers’ ranch. At one point, she seats herself at the piano and proceeds to struggle through a piano reduction of Johann Strauss Sr.’s “Radetzky March.” Campion then cuts to Phil sitting in his bedroom offscreen. Phil then picks up the melody of the Strauss piece on his banjo, playing it almost effortlessly and improvising his own coda. In a test of wills, Phil’s virtuosity humiliates Rose, who increasingly turns to alcohol to soothe her emotional wounds.

Because of this scene, Greenwood used a detuned mechanical piano as a musical timbre associated with Rose.

To produce this effect, Greenwood used computer software to create the sound of a piano roll for his pianola. Then, as the music was played back, Greenwood used a tuning wrench to slightly alter the pitches to create a sound akin to the honkytonk pianos scene in the saloons of older Westerns. For Greenwood, the sound proved perfect for Rose’s character arc. As he states in an interview for Variety, “Not only is her story wrapped up in the instrument, but it was also a good texture for her gradual mental unraveling. I recorded hours of this stuff – poor Jane (Campion) had to hear quite a lot of it.”

Greenwood’s modernist take on the typical Western score makes him one of the top contenders in this year’s Oscars. Of course, it doesn’t hurt that Greenwood wrote music for two other nominated films: Licorice Pizza and Pablo Larraín’s Princess Diana biopic, Spencer. The betting markets have Greenwood as a longshot. However, since The Power of the Dog leads the field with a dozen nominations in all, Greenwood could prevail in the event of a Dog sweep.

Today’s sounds for tomorrow’s people

The last nominee for Original Score is the current favorite. Hans Zimmer earned his thirteenth Oscar nomination for Dune, Denis Villeneuve’s big budget adaptation of Frank Herbert’s classic science-fiction novel. As Zimmer notes in a New York Times profile, he self-consciously rejected the musical style associated with the Star Wars series and its many imitators. Those scores looked to the past for inspiration, finding it in Gustav Holst, Igor Stravinsky, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and even Benny Goodman. Instead, Zimmer set himself an almost impossible task, trying to create sounds that no one had ever heard before.

The result is a score that Darryn King calls “one of Zimmer’s most unorthodox and most provocative.” The composer reports that he spent days contriving new sounds, sometimes commissioning the construction of new instruments or using conventional instruments in extremely unusual ways to get the effect he desired. Although synthesizers keep the score rooted in Zimmer’s pop music past, he combines these with several unusual sonorities that include Irish whistles, Indian bamboo flutes, and metallic scraping noises.

Many of these instrumental choices are keyed to aspects of Dune’s intergalactic setting. The rumble of distorted electric guitars evokes the seismic shifts occurring beneath the desert sands on the planet’s surface. Zimmer even used some of the environmental details to communicate what he wanted from the musicians performing on the soundtrack. Slide guitarist David Fleming reports that Zimmer told him for one cue, “This needs to sound like sand.”

Zimmer performed similar wonders in his use of other instruments. For the scene where the House of Atreides arrives on Arrakis, Zimmer recorded thirty bagpipes playing in a Scottish church. The added reverberance raised the volume of the ensemble to ear-splitting levels of 130 decibels. The highland players needed to wear earplugs to avoiding damaging their hearing. But Zimmer got the sound he wanted, the musical equivalent of a blaring air raid siren.

Zimmer’s desire to find new sounds not only altered the usual timbres of instruments but also of the voice as well. For Dune, Zimmer engaged the services of music therapist and singer Loire Cotler. To create the qualities Zimmer was seeking, Cotler drew on several non-Western singing styles. Her syncretic method combined Jewish niggun, South Indian vocal percussion, Celtic lamentation, and Tuvan throat-singing. The end result was a hybridized style that sounded wholly unique: a war cry expressed as though it were an ancient antecedent of Esperanto. Cotler tried to find a name for the new vocal technique, ultimately settling for the person responsible; she called it the “Hans Zimmer.”

Perhaps Zimmer’s most audacious gesture involved hiring winds player Pedro Eustache to build new instruments from scratch. Eustache created a 21-foot horn, a sort of modern version of the old animal horns fashioned into shofars and zinks during the Middle Ages. He also produced a contrabass version of the duduk, which King described as a “supersize version of the ancient Armenian woodwind instrument.”

What does it all add up to? A score that hits all the right notes in transposing Herbert’s imposing epic to the big screen. Zimmer’s music is at times quietly menacing, somber and pensive at other moments, and brooding but anthemic for Dune’s big action scenes. Zimmer’s score for Dune does not depict the kind of triumphalism found in Star Wars or other space operas. Rather, it opts to capture the elements of dark mysticism and doleful psychedelia that made Herbert’s novel a literary head trip in the 1960s. To be sure, Zimmer’s music doesn’t concoct earworms to evoke the sandworms. Yet it succeeds admirably where others have failed nobly. (If you think this is easy, just watch and listen to David Lynch’s misbegotten adaptation from 1984.)

Prediction

One could easily make the case for Germaine Franco to win for Encanto. The score and the album have dominated the popular music scene ever since the film was released in late November. Yet Dune stands a good chance at claiming several other craft awards, such as those for Sound and Production Design, which bodes well for Zimmer’s chances on Sunday.

In the world of film music today, the Burgomeister of Bleeding Fingers Music casts a shadow over the field as large as any of the luminaries who preceded him like Ennio Morricone, Jerry Goldsmith, or Dimitri Tiomkin. When I contemplate the sheer number of innovations Zimmer made in the music he composed for Dune, I can’t bring myself to bet against him. I think Hans takes home the Oscar on Sunday. He’ll walk away with another hunk of metal to scrape for the Dune sequel.

Once again, I want to give a shout-out to Jon Burlingame for his excellent coverage of Hollywood and international film music for Variety. As a subscriber, I always enjoy reading his work for the venerable trade journal, not just during awards season but year-round.

The Diane Warren interview with USA Today that I referenced can be found here. Additional interviews with Deadline and Gold Derby are found here and here.

Interviews with Lin-Manuel Miranda discussing the songs he wrote for Encanto can be found here , here, and here.

Vulture published a nice piece on the process of writing the title song for No Time to Die, which can be found here.

Alberto Iglesias discusses with work with director Pedro Almodovar here .

Nicholas Britell talks about his work Don’t Look Up with Indiewire and Variety here and here . One can find several interviews with Germaine Franco about her process on creating the score for Encanto. A sample can be found here, here, here, and here. A movie score suite featuring Franco’s themes for Encanto can be found here.

Jonny Greenwood talks with Variety about his collaboration with Jane Campion here and here.

The indie-music website provides an interesting review of Greenwood’s soundtrack for The Power of the Dog here.

Finally, Darryn King’s superb overview of Hans Zimmer’s score for Dune can be found here.

Parallel Mothers

Oscar’s Siren Song (A Slight Return): Best Original Song

One Night in Miami (2020).

Jeff Smith here:

On Monday, I offered an overview of the five nominees for Best Original Score as well as a prediction regarding the winner. Today, I do the same for the Best Original Song nominees.

The usual caveats apply for those readers interested in the online betting markets. My picks are for “entertainment purposes only.”

As we’ll see, the race in the Best Original Song category is extremely competitive. Indeed, I almost flipped a coin to make my final decision. I didn’t. But the very fact that I thought about it indicates the low level of certainty I have about my prediction.

I should add that there are a few SPOILERS AHEAD. If you don’t want to know some of the key plot twists in Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga or a small but important plot point of The Life Ahead, you can skip to the last section.

Best Original Song: The Underdog

One striking detail about this year’s nominees is the fact that four of the five function as “needle drops” introduced as the film’s closing credits start to roll. Perhaps a steady diet of television episodes streamed during the pandemic has accustomed viewers to expect that this is the way songs now function in movies. Several shows, both old and new, have used these needle drops quite creatively. (I’m thinking here of Mad Men, The Marvelous Mrs. Maysles, and WandaVision. I’m sure you all have your own favorites.)

Set off from the narrative flow of the episode, music supervisors found they could use a song as a curtain closer to highlight elements of theme, tone, or mood without worrying about things like time period or the musical tastes of the show’s characters. Such transmedial influences eventually might establish this as the primary function of popular songs in films. If this year’s nominees are any indication, the trend is already well on its way.

The one exception is “Husavik (My Hometown)” from Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga. The film, of course, is a vehicle for star Will Ferrell. He plays an Icelandic version of his usual man-child persona. It adds, though, a musical competition element borrowed from other comedies, like Pitch Perfect, and from popular music shows, like American Idol.

Ferrell plays Lars Ericksong, a humble “meter maid” whose lifelong dream is to compete in the Eurovision Song Contest. Eurovision, of course, is an annual event in real-life. It remains the longest running internationally televised music competition. The contest played an instrumental role in launching the careers of artists like ABBA, Céline Dion, and Julio Iglesias.

Lars hopes to follow in their footsteps, but his ambitions are mocked by the other residents in his small town.

Lars’ only defender is Sigrit, his childhood friend and his partner in the musical duo Fire Saga. Fire Saga plays a vital role in the town’s musical culture, performing regularly at a local bar. Yet their audience mostly rejects their musical offerings. Instead, they prefer “Ja Ja Ding Dong,” a sexually suggestive nonsense song that is the antithesis of past Eurovision winners.

Sigrit, played winningly by Rachel McAdams, is steeped in Icelandic folklore. She makes offerings to a small den of elves that she hopes will prompt Lars to return her considerable affections for him. She also believes in the “speorg note,” a mystic tone that Sigrit’s mother tells her represents the truest expression of the self.

Fire Saga enters the national competition hoping to earn the honor of representing Iceland. During an Icelandic Public Television meeting, their song is picked at random simply to meet Eurovision’s requirements for a country’s eligibility. At Reykjavik, Lars and Sigrit nervously wait backstage for their performance. Sigrit wishes that she could sing in their native language since it would calm her down. Lars, though, warns against it noting that a song in Icelandic would never win Eurovision.

Fire Saga loses to a talented competitor named Katiana, played by Demi Lovato in a nice cameo. Embittered, Lars refuses to attend a party celebrating the winner and Sigrit joins him in solidarity. When the boat hosting the party explodes, killing everyone aboard, Fire Saga becomes the Icelandic entry as the only surviving runner-up.

Once in Edinburgh, the site of the 2020 competition, Lars and Sigrit clash regarding the best way to present their music. (In reality, the 2020 Eurovision contest was to be held in Rotterdam but was cancelled due to the pandemic.) Lars wants to wow the audience with elaborate costumes and stagecraft. He also hires a K-Pop producer to remix their recording, giving it a hip new arrangement. Sigrit would rather just let the music speak for itself.

During the semi-finals, Fire Saga’s performance of “Double Trouble” seems to be going well. But Lars’ desire for showmanship backfires when the absurdly long scarf he has given Sigrit gets caught in the gears of his giant hamster wheel.

Sigrit is able to free herself before she suffers the fate of Isadora Duncan. But the hamster wheel breaks free and crashes into the audience. Although Lars and Sigrit recover just in time to finish the song, they are initially met with stunned silence. This is followed by some snickers scattered amongst the crowd. Lars and Sigrit leave the stage dejected, smarting from their humiliation.

Crestfallen, Lars returns to Húsavik, reconciled to life as a fisherman rather than a musician. Sigrit stays behind to continue her dalliance with Alexander Lemtov, a rival contestant from Russia. Sigrit is gobsmacked when she learns that Fire Saga has been voted through to the finals, a plot twist perhaps inspired by the real-life hate-watching that produced surprisingly long runs by American Idol contestants like Sanjaya Malakar.

Lars makes a mad dash back to Edinburgh, both to participate in the finals and to declare his love for Sigrit. Looking like the Gorton Fish guy, Lars sneaks onstage just as Sigrit has begun “Double Trouble.” He stops her mid-phrase and persuades her to sing a new song even though he knows the change will result in Fire Saga’s disqualification. Sigrit begins tentatively but soon grows in confidence as she reaches the chorus, sung in Icelandic much to the delight of those watching in Húsavik. The song builds to its climactic final note, a high C# that is held for several seconds, leaving both the audience and Lars rapt in awe. This time Fire Saga’s performance is met with thunderous applause. In an aside just for the viewer, Lars exclaims, “The speorg note!”

There’s a lot wrong with Eurovision. Some of the film’s gags misfire badly. The race to get Lars from the airport to the auditorium features the kind of crazy stunt work that’s grown stale from overuse. (Think spinning car and reaction shots of screaming passengers!) And at 126 minutes, Eurovision has two or even three subplots too many.

Yet the filmmakers definitely stick the landing with Fire Saga’s triumphant performance of “Husavik (My Hometown).” Seeing Lars cede the spotlight to Sigrit and her rise to the moment brings a lump to the throat, just as it does in other show-biz success stories like 42nd Street (1932) and A Star is Born (2017). (It’s an old formula but a potent one.)

Moreover, the sequence pays off several dangling causes (the reference to Icelandic lyrics in the scene backstage, the rekindled romance of Lars’ father and Sigrit’s mother, the speorg note). Even Fire Saga’s disqualification strikes the right tone by making the duo the musical equivalent of Rocky. They win by losing, content in the knowledge they were worthy contenders and in the realization of what they truly value. Watching the folks back in Húsavik swell with community and nationalist pride is just the cherry on top of a very satisfying sundae.

Any one of Eurovision’s Europop pastiches would have been worthy of nomination. For example, the faintly ridiculous quality of Lemtov’s “Lion of Love” makes it a perfect surrogate for the character’s ostentation and vanity. But only “Husavik (My Hometown)” both tickles the fancy and tugs the heartstrings.

Still, despite its appositeness for Eurovision’s story, I think it is a long shot when it comes to claiming the trophy. You have to go back to The Muppets in 2011 to find an Oscar-winning song in a live action comedy. And that was a strange year in which there were only two nominees. Before that, you have to reach all the way back to 1984’s The Woman in Red. That year, the winner was “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” written and performed by the great Stevie Wonder. Despite its considerable craft, “Husavik (My Hometown)” seems unlikely to alter a trend that rewards songs in dramas rather than comedies.

The Bridesmaid (as in “Always the…”)

This past February, Diane Warren received her twelfth Academy Award nomination for “Io Sì (Seen),” featured in the Italian film, La Vita davanti a sé. Warren has won an Emmy, a Grammy, and two Golden Globe awards, but has yet to claim an Oscar. This puts Warren in some pretty good company. Her colleague, composer Thomas Newman, has been nominated fifteen times without winning. Composer Victor Young received 21 nominations before finally breaking through with Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Sadly, Victor Young didn’t live long enough to actually receive the award. He died at age 57 just months before the ceremony.

Warren’s latest effort, “Io Sì (Seen),” is the type of soaring power ballad she has spent much of her professional life perfecting. The song starts with a modest piano figure that accompanies Laura Pausini’s indomitable voice at a moderate tempo. The lyrics offer a simple but powerful declaration of emotional support regarding the need to be “seen.” Pausini’s voice rises in the chorus as she vows in Italian, “But if you want, if you want me, I’m here.” The addition of a string orchestra and tasteful percussion accents provides additional emotional heft.

The modest arrangement allows the song’s simple beauty to shine through. Its mood and Pausini’s vocal delivery seem miles away from the bombast that made Aerosmith’s “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing,” one of Warren’s earlier nominees, a chart-topping single.

For me, though, that is all to the good. La Vita davanti a sé is itself an unassuming coming-of-age tale that depicts the unlikely friendship that develops between Madam Rosa, an elderly Holocaust survivor, and Momo, a 12-year-old orphan from Senegal.

Buoyed by Sophia Loren’s valedictory performance, the song reflects the strong filial bonds that form when Momo becomes Rosa’s ward. The lyrics’ reassurance that “I’m here” capture the ways in which Momo and Rosa have learned to care for one another. Placed just after the funeral ceremony that closes the film, “Io Sì (Seen)” sustains the scene’s bittersweet, melancholy tone and carries it into the credits. The song also reiterates the story’s central themes regarding the need for unconditional acceptance and love’s ability to overcome differences in gender, race, and age.

La Vita davanti a sé has become an unlikely hit for Netflix. At the peak of its popularity, it reached the streaming service giant’s top ten in 37 different countries. Perhaps that sleeper success will bolster Warren’s chances among Academy voters. She is eminently deserving of the award as a sort of career honor.

Could this be Warren’s year? Perhaps. Still, the fact that more famous songs by Warren, like “Because You Loved Me” and “How Do I Live,” also suffered defeat raises some doubts.

Panthers and Boxers and Yippies (Oh My!)

The three remaining nominees are all songs featured in films that look back at the legacy of sixties political activism. Unlike Eurovision Song Contest and La Vita davanti a sé, Judas and the Black Messiah, One Night in Miami, and The Trial of the Chicago 7 all received multiple nominations. Often the halo effect created by that reflected glow can make a difference in very competitive races. Moreover, the two titles receiving Best Picture nominations – Judas and Chicago – also benefit from the massive “For Your Consideration” ad campaigns that appear in trade publications like Variety. All of this suggests that, if you are looking for this year’s winner, you might look here.

Let’s start with “Fight for You,” the groovin’ track by H.E.R. that closes Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah. The song self-consciously evokes music from the period depicted in the film. As H.E.R. told Variety, she wanted the music to have a hopeful vibe, but lyrics that connected to the Black Panthers’ historic fight against injustice. She drew upon the classic soul music of Marvin Gaye, Nina Simone, and Sly and the Family Stone, artists who made records that were both popular and politically astute.

The final product is a remarkable synthesis of these different elements. The syncopated brass and organ chords recall vintage Sly and the Family Stone tunes like “Stand.” The spare but funky bass line and the supple guitar melody wouldn’t be out of place on Gaye’s classic, “Let’s Get it On” while the doubling of H.E.R.’s voice, sometimes in octaves and sometimes in thirds, conjures up his masterful What’s Going On album. The string arrangements and choral melody also bring to mind Curtis Mayfield’s classic score for Superfly (1972) for good measure. Only one of the five nominees will make you want to get up dance, and this is it. With its Funk Brothers arrangement and uplifting social message, “Fight for You” educes a bit of folk wisdom from P-Funk guru George Clinton: “free your mind… and your ass will follow.”

Celeste and Daniel Pemberton’s “Hear My Voice” from The Trial of the Chicago 7 also evokes sixties soul, albeit with more of pop flavor and even a dash of Northern soul. Celeste grew up around Brighton on England’s southern coast. Her interest in music was nurtured by her early exposure to American jazz vocalists like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. Those influences can be heard in Celeste’s elegant phrasing on “Hear My Voice.” (Beware ads.) But her vocal style has also drawn comparisons to more contemporary British soul singers like Amy Winehouse and Adele.

The end result doesn’t slavishly duplicate any of those other singers, emerging as something else entirely. In fact, although Celeste’s voice has a timbre all her own, to my ears, the slightly retro vibe of “Hear My Voice” evokes sixties pop and blue-eyed soul artists like Dionne Warwick and Dusty Springfield. The song itself is a mid-tempo ballad with a loping, syncopated beat and an arching upward melody furnishing the tune’s main hook. Pemberton’s arrangement heightens the pop elements in the recording by emphasizing the piano and strings climbing steadily upward.

The Trial of the Chicago 7’s title is fairly self-explanatory, dramatizing the prosecution of activists from the Black Panthers, the Yippies, and Students for a Democratic Society after protesters violently clashed with police at the 1968 Democratic Convention. David’s blog on Aaron Sorkin shows, among other things, how the screenwriter/director drew upon the “drama of ideas,” a tradition associated with “turn of the century” playwrights like Henrik Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw. In a slight break from that tradition, though, Sorkin sought to end the film on a note of optimism and hope that would yield a sense of empowerment.

According to Pemberton, the director’s first choice for an end-title song to reflect that tone was the Beatles’ classic from Abbey Road, “Here Comes the Sun.” The composer, though, gently persuaded Sorkin to try something fresh, a new song unburdened by the enormity of the Beatles’ legacy. He also reminded Sorkin of the huge licensing fees that any Beatles song would inevitably command. Pemberton and Celeste’s much-deserved Oscar nomination vindicates the composer’s instincts. Had Sorkin used “Here Comes the Sun,” viewers would have soaked in its upbeat vibe. But The Trial of the Chicago 7 would have gotten only five nominations rather than the six it ultimately received.

Last, but certainly not least, we have Leslie Odom Jr. and Sam Ashworth’s “Speak Now,” featured in Regina King’s directorial debut, One Night in Miami. The film offers a fictionalized account of a fabled meeting of four icons of the 1960s: Malcolm X, Jim Brown, Muhammad Ali, and Sam Cooke.

The group assembles in a room at the Hampton Hotel to celebrate Ali’s victory over then heavyweight champion Sonny Liston. Yet, with only some vanilla ice cream and a flask of booze as party favors, the good-natured banter soon devolves into a debate about the best ways to achieve social change on the path toward racial equality.

Both musically and lyrically, “Speak Now” seems keyed to an important scene in the film where Malcolm chides Cooke for recording trifling love songs rather than music that speaks to the ongoing struggle for civil rights. He pulls out a copy of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and plays “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Malcolm then asks Sam why it is that a white boy from Minnesota makes music that seems so perfectly attuned to the historical moment. Isn’t “Blowin’ in the Wind” the type of song Cooke should write? Malcolm’s criticism becomes a dangling cause that is picked up in the film’s epilogue. As a guest on The Tonight Show, Sam performs “A Change is Gonna Come” for the first time, showing how he embraced Malcolm’s challenge to him.

Beginning with a syncopated acoustic guitar riff, “Speak Now” not only recalls several moments of the film where Cooke pulls out his own guitar, but also evokes the type of folk music that was Dylan’s stock in trade during the early sixties. The guitar is soon joined by a swirling Hammond B-3 organ. The instrument’s timbre evokes both the gospel music that inspired Cooke throughout his career and Al Kooper’s distinctive organ stylings on two Dylan masterpieces recorded after he went electric: Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. Floating above both is Odom’s plaintive voice, urging the film’s viewer to “Listen, listen, listen.” Providing the link between past and present, the lyrics entreat the audience hear to the “echoes of martyrs” and the “whispers of ghosts.” Odom’s soaring falsetto suggests both vulnerability and hope. The song gradually builds, adding strings and percussion, until it reaches a rousing climax.

With its simple arrangement and its mixture of styles, “Speak Now” sounds like the musical child that Bob Dylan and Sam Cooke never had the opportunity to conceive. It provides a fitting end to One Night in Miami by reminding us that the struggle for civil rights continues, especially at a historic juncture where America is challenged to confront the structural and institutional foundations of white privilege and white supremacy.

Prediction

On Oscar night, I will be watching with bated breath to see if…..

…singer Molly Sandén hits the “speorg note” during the performance of “Husavik.” If she does, it will bring down the house (or at least break a few champagne glasses).

But the winner? Your guess is as good as mine. This is among this year’s most competitive races. In Variety, Jon Burlingame notes that Diane Warren’s past nominations made her the early favorite, but adds, “You can’t count out anyone, however, in this year’s level playing field.”

If the vote reflects the song that is most clearly integrated into the film’s story, it’s “Husavik.” It is also rumored to be making a late charge, aided by late campaigns by Netflix and the tiny town of the title.

If, on the other hand, the vote reflects the song that I’d want next in my iTunes queue, it’s “Fight For You.” It’s got a funky groove that just keeps on keepin’ on.

That being said, I don’t think either of those two songs will carry the day. Ever since the nominations were announced, it’s generally felt like a two-horse race: Diane Warren vs. Leslie Odom Jr. The voting could split between those who desire to finally recognize Warren after so many nominations and those who find Odom deserving of the award for Best Supporting Actor but who still voted for Daniel Kaluuya instead.

The fact that Odom is a double nominee would seem to help his chances. But his song’s social significance also gives it a slight edge. In 2015, Common and John Legend took home the prize for “Glory,” their inspirational song from Selma. Like “Speak Now,” the lyrics of “Glory” captured the zeitgeist surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement, particularly the protests in Ferguson, Missouri. The message of “Speak Now” is just as relevant and just as timely. It is possible that voters will want to acknowledge it for that very reason.

Still my gut tells me this is Diane Warren’s year. Thirty-three years ago, Warren sat in the venerable Shrine Auditorium as a first-time nominee. She came in with a fighter’s chance. Her song, Starship’s “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now,” had a fighter’s chance having hit the top of the charts in five different countries, eventually earning gold or platinum record status in four of them. But it was aced out by an even more popular song, “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life” from Dirty Dancing. It had gone to #1 in six countries and earned gold or platinum status in seven different markets.

Warren’s been waiting ever since for a chance to pop the cork in a champagne bottle at an Oscars afterparty. I think the bubbly finally flows for her this Sunday.

Once again, a shoutout to Jon Burlingame for his coverage in Variety of the Academy Awards’ music categories. His analysis of the Best Original Song nominees can be found here, here, and here.

To find short interviews with all of the songwriting teams, check out these items from The Hollywood Reporter and Billboard.

A podcast with H.E.R. discussing her collaboration with Tiara Thomas and D’Mile on “Fight For You” can be heard here.

A very long interview with Daniel Pemberton describing his work on The Trial of the Chicago 7 can be found here.

Leslie Odom Jr. talks about writing “Speak Now” here and here.

Finally, Diane Warren performs a medley of all twelve of her Oscar-nominated songs here.

Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga (2020).

Oscar’s Siren Song (A Slight Return): Original Score

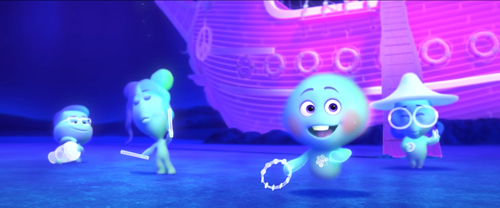

Soul (2020).

Jeff Smith here:

After a short hiatus, I’m back with a preview of this year’s Oscar nominees for Best Achievement in Music Written for Motion Pictures. As with everything else in the COVID pandemic, this year’s nominees represent a slight departure from previous years. With the massive shuffling of release schedules, some films like No Time to Die, Dune, and In the Heights that would have been strong contenders in these categories will have to wait until next year. At the same time, the closure of theaters, and the attendant changes regarding Oscar eligibility, meant that some smaller films’ fortunes were boosted by their availability on top streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime.

Here I survey the five scores that received nominations and offer a prediction regarding the eventual winner. Later this week, I’ll do the same for the Best Original Song nominees.

The usual caveats apply for those readers interested in the online betting markets. My picks are for “entertainment purposes only.”

Moreover, I admit that my track record hasn’t exactly been stellar. If memory serves, I’ve gone five for eight in my previous predictions. That’s about a 62% accuracy rate. Better than chance but hardly anything to brag about.

Consequently, I advise readers to treat both predictions as the equivalent of a handicapper’s pick for a daily double. It feels really good if you are right. But truth be told, odds are against it.

Let’s turn now to the nominees for Best Original Score. At first blush, it would be hard to imagine a more disparate group of nominated films. It includes a Western, an adventure film, a family drama, a retro-styled biopic, and a metaphysical comedy in cartoon form.

Composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross are heavy favorites going into Sunday as double nominees. They were recognized both for their jazz-flavored orchestral score for Mank and, along with fellow nominee Jon Batiste, for their electronic atmospherics in Soul. As previous winners for The Social Network (2010), they stand a good chance of adding more little gold men to their mantles.

The long shot

The Oscar betting markets have Terence Blanchard’s score Da 5 Bloods as the nominee with the longest odds. That is a shame insofar as Blanchard remains one of the most underrated composers writing for films. Using a 90-piece orchestra, Blanchard provides an epic sound for Spike Lee’s clever take on The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. I wouldn’t say Blanchard and Lee’s collaboration on Da 5 Bloods is a career best. For me, their peak is represented by the magisterial score in 25th Hour (2003), one of the best films of the 2000s. Still, Blanchard’s music for Da 5 Bloods is awfully, awfully good.

Besides the resources of a conventional orchestra, Blanchard also engaged the services of Pedro Eustache to play the duduk, an Armenian double reed instrument that adds an unusual tone color to some of the score’s melodies. The duduk adds a touch of exoticism as a reminder that the protagonist Paul and his crew of Vietnam vets are strangers in a strange land. Yet the score wisely avoids the kinds of Orientalizing musical gestures that are common in many Hollywood films with South Asian settings. The duduk is heard in a handful of cues that underscore Otis’ relationship with Tien, his old Vietnamese girlfriend.

In contrast, strings and brass are key to several cues pitched in an elegiac register. As Todd Decker notes in his book, Hymns for the Fallen: Combat Movie Music and Sound after Vietnam, this style of music became especially common in Hollywood war films after Samuel Barber’s famous Adagio for Strings was used so memorably in Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986). A good example is “MLK Assassinated” where the squad reacts to Hanoi Hannah’s announcement of the civil rights leader’s death.

Blanchard, too, mines this vein in cues accompanying scenes where the crew recalls the death of their squad commander Stormin’ Norman Earl Holloway.

Da 5 Bloods is a film of greed and grief, rage and remorse. Blanchard’s score not only captures the frustrations occasioned by America’s racial reckoning, but also reveals the deep sadness beneath, paying tribute to the sacrifices Black soldiers made while serving in Vietnam.

The Newbie

Our second nominee is Minari, which features the music of composer Emile Mosseri. Mosseri studied film scoring at the prestigious Berklee College of Music in Boston. But he also is a member of an indie rock band, The Dig, which has released three albums and four EPs since their debut in 2010. Mosseri got his first major film assignment in 2019 when he wrote the score for Joe Talbot’s acclaimed debut, The Last Black Man in San Francisco. Mosseri soon established himself as an up-and-comer in the world of American Indie cinema. In 2020, Mosseri not only wrote the music for Minari, but also scored Miranda July’s Kajillionaire.

Minari tells the autobiographical story of a Korean-American family’s move to Arkansas in the 1980s. When Mosseri offered to help with the film’s music, director Lee Isaac Chung gave the composer only one directive. He told him not to do something Korean. Instead, Chung and Mosseri discussed the work of Maurice Ravel and Erik Satie, seeing their impressionistic, delicate tone as an idiom more fitting for the story. Mosseri took the unusual step of writing some sketches before production began. This assured that the tone of the score was “baked in” to the film throughout post-production. It also allowed Chung and his film editor to adjust the duration of shots and select takes to better fit Mosseri’s already existing music.

Given Ravel’s and Satie’s influence on the score, it is not surprising that Mosseri’s melodies and orchestrations emphasize piano and strings. Mosseri, though, varies the tonal palette by occasionally adding voices, winds, and vintage LFO synthesizers, instruments whose timbre helps to suggest the feeling of a “dream-memory” soundscape. Many of the cues unfold as patterns of slowly shifting harmonies. This is evident in “Outro” which can be heard below.

Mosseri notes that the real challenge in the film was to communicate Minari’s warm and gentle tone without being saccharine. The score’s modesty makes it appear to be the polar opposite of Blanchard’s epic style in Da 5 Bloods. Whereas Blanchard goes for emotional sweep and impassioned sorrow, Mosseri strives for reserve and subtlety. Moreover, although Blanchard writes for a 90-piece orchestra, Mosseri’s ensemble is less than half that size. Lastly, whereas Da 5 Bloods contains a lot of music — not just Blanchard’s score, but also another ten period-appropriate songs — Minari has a little over thirty minutes of underscore, heard for less than a third of the film’s 115-minute running time.

Still, Minari and Da 5 Bloods have one thing in common. A film composer’s first job is to serve the story, tailoring their music to the specific needs of each scene. Blanchard and Mosseri have done that as well as anyone this past year. I would be happy to hear either one of their names called out as the winner come Sunday night.

The Oater

The third film nominated for Best Original Score is the Paul Greengrass Western, News of the World. Unlike Mosseri, who is a first-time nominee, this is composer James Newton Howard’s ninth nomination. During a career in Hollywood that spans more than 35 years, Howard has enjoyed close collaborations with directors like M. Night Shyamalan and Francis Lawrence. His music has also been a vital component of popular franchises like The Hunger Games and the Harry Potter spinoff, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.

On a personal note, Howard played a key role in my own musical biography. Earlier in his career, Howard did string arrangements and played keyboards on Elton John’s Blue Moves (1976), an album that was among the first dozen or so I bought as a teenager. I also listened repeatedly to its biggest hit, “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word,” trying to slavishly duplicate both Elton’s piano part and Howard’s nifty keyboard solo. Elton won last year for Rocketman in the category of Best Original Song. It somehow seems fitting that Howard could take home an Oscar this year for Best Original Score.

News of the World tells the story of Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd, a Civil War veteran who travels across Texas, reading news stories aloud in frontier towns for both entertainment and edification. Early on, Kidd comes across an overturned wagon and discovers a lost child. Abducted by the Kiowa, Johanna was being escorted back to her family by a federal officer when their party was bushwhacked. Kidd learns that Johanna will have to wait several months for the return of the Bureau of Indian Affairs representative. So the Captain decides to deliver Johanna to her surviving family. The rest of the film dramatizes their growing bond as Kidd and Johanna make the 400-mile trek through hostile territory to her aunt and uncle’s homestead.

Adapted from Paulette Jiles’ 2016 novel, News of the World feels a bit like a mashup of The Searchers (1956) and the Coen Brothers’ remake of True Grit (2010). Its kidnapped-child premise seems inspired by the former while the picaresque journey structure and “father-daughter” emotional dynamic derive from the latter.

Several of the film’s plot elements, though, offer comment on contemporary politics. The brusque handling of Johanna by Union Army officials in Texas can’t help but remind us of the Trump administration’s family separation policies. Similarly, when Kidd and Johanna are stopped by brigands from a radical militia, they are taken to a town governed under White Supremacist principles, an episode that serves as a grim reminder of contemporary threats of domestic terrorism.

Like Mosseri’s score for Minari, much of Howard’s music in News of the World strives to capture the intimacy and deepening trust that develops between the central characters. That relationship is reflected in one of Howard’s main musical themes heard here in a cue entitled “Kidd Visits Maria.”

Howard’s cues often feature long languid melodies in the strings, but he also nominally adheres to genre convention by incorporating harmonica, mandolin, banjo, guitar, and scratchy fiddle airs to flavor the score with a folksy, period sound. For a handful of scenes involving shootouts, hazardous travel, and hair’s breadth escapes, Howard furnishes the rhythmic drive and dynamics that give them their emotional punch. But the score is most effective in its quiet and reflective moments. Kidd and Johanna both suffer from a sense of loss and loneliness. As they gradually come to realize how much they need each other, Howard’s music communicates that well of feeling, expressing what the characters themselves are too reticent to admit.

Souls and the Soulless

This brings us to the final two nominees: Mank and Soul. For Mank, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross sought to create a score that would seem experimental if it were featured in a film made in 1940. To some extent, they succeed. By opting for an orchestral jazz sound, they evoke a style that did not become common until the 1950s when it was popularized by later Hollywood composers like Alex North, Elmer Bernstein, and Henry Mancini. Still, despite that disjuncture, Reznor and Ross’ score still seems period appropriate insofar as it recalls much of the popular music recorded during the 1930s.

In preparing Mank’s score, Reznor and Ross decided to write cues in two different, but related styles. One set of cues involved big-band and foxtrot arrangements that would underscore scenes involving studio politics. An example is the cue “Fool’s Paradise” heard below.

The other set of cues deployed an orchestral palette and speak more to Mank’s emotional journey over the course of the film.

Notably, Reznor also admits that they often referred back to Citizen Kane during the writing process. Not surprisingly, some cues, like “Welcome to Victorville” and “Absolution,” sound a bit “Herrmannesque” in their evocation of Kane’s famous score.

A few, such as “San Simeon Waltz,” are even in the lyric mode Bernard Herrmann used in scores like The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947). The latter, not coincidentally, was directed by Herman Mankiewicz’s younger brother, Joseph.

For the most part, Mank’s music hits all the right notes, as bracing as a warm breeze on a summer day. The score is aptly sweet and tender for the heart-to-heart talks between Mank and Marion Davies, arch and mischievous for moments that display Mank’s acrid wit. In fact, Mank’s score seems most period-appropriate on the rare occasions when it indulges a bit of “Mickey-mousing.” An example of this occurs in the scene where Mank drunkenly stumbles as he exits a car in front of Glendale Station. As Ross notes, the music “gets drunk” as well with muted horn figures that could easily have been pulled from an MGM or Warner Bros. cartoon. All that’s missing is the sound of Mank’s hiccup.

And then there’s Soul. Reznor and Ross’ collaboration with New Orleans musician Jon Batiste is a favorite with good reason. The film’s protagonist is a jazz pianist, an element of the story that makes music integral to the viewer’s experience. Such narrative motivation has certainly helped several previous winners, like La La Land, The Red Violin, and Round Midnight. It also helps that Soul has swept almost all of the year-end critics’ awards for Best Score as well as winning a Golden Globe, a BAFTA, and a Society for Composers and Lyricists Award.