Archive for the 'National cinemas: UK' Category

Vancouver 2019: Tales of oppression and resistance

Bacurau (2019).

Kristin here:

Examinations of social problems and portrayals of downtrodden people are fertile ground for makers of art cinema. This year’s festival saw many films from around the world tackling such subjects in original ways. Here are four impressive instances.

Castle of Dreams (2019)

Reza Mirkarimi is one of Iran’s top filmmakers, with three of his films having been put forward as Iran’s nominee for an Academy Award. In Castle of Dreams he has created a sort of nightmare version of the traditional child-quest tale so popular when Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf were at the heights of their careers. The protagonist, Jalal, has recently been in jail. The film opens as he is making some sort of a deal by telephone. His wife has just died after a protracted illness, and his sister-in-law, who had been taking care of Jalal’s two young children, is forced by her husband to turn them over to Jalal. But he clearly wants nothing to do with them.

Jalal sets out with them in his late wife’s car, picking up his Azeri fiancée on the way to Azerbaijan. He continuously snaps at the small children, Sara and Ali, and at his fiancée. It eventually comes out that he had taken his wife off life support and sold her heart for transplant, all without telling her brothers. Despite his occasional clumsy attempts to be kind to the children, any expectations that the audience may have that he will be charmed by them and transform into a responsible father are far too optimistic.

If this were a traditional child-quest plot, Sara and Ali might struggle to get back to their kindly aunt. Here, despite becoming increasingly miserable as Jalal’s full villainy is revealed, they are essentially prisoners in the back seat of the car (above). Ultimately the film takes a clear-eyed, realistic view of the future for this little family.

The acting carries much of the film. Hamed Behdad won a best-actor award at the Shanghai International Film Festival (where the film also won the best-picture prize). The child actors are charming and elicit considerable sympathy for their plight.

Song without a Name (2019)

Inspired by a real-life case that her journalist father investigated, Melina León’s first feature successfully generates sympathy for her two main characters and recalls the horrors of the past. Set in 1988, it follows Georgia, a pregnant indigenous woman living in a shack near the sea and scraping by as a street-seller of potatoes (above). Lured in by a radio ad, she visits a free clinic with a reassuring name, the “Saint Benedict.” The organization is anything but benevolent, however, spiriting her newborn daughter away for “check-ups.” Desperate to find the baby, she and her partner Leo encounter only indifferent police and other other government officials.

Eventually she finds a sympathetic helper in Pedro, a reporter who confidently promises that they will recover her baby, despite the fact that it has most likely been spirited out of the country for adoption. While Pedro pursues his investigation, Georgina finds her ability to purchase wholesale potatoes shrink in the face of rampant inflation, on top of which she discovers that Leo is apparently a member of the Shining Path terrorist group. Pedro meanwhile starts an affair with a gay actor in his apartment block, only to be threatened with exposure and death, presumably by the gang that runs the baby-stealing operation.

The film will inevitably be compared to Roma, even thought the films have nothing substantive in common. Both are black-and-white, Latin American films, and both heroines are pregnant; that’s the extent of the resemblance. León’s film has nothing of the nostalgia that permeates Roma, and Georgina is far more marginalized and downtrodden than Cuarón’s heroine.

León also is working with a far smaller budget and yet with the help of cinematographer Inti Briones she has fashioned a sophisticated and lovely film. One lengthy shot is particularly impressive. In it Pedro meets with a potential witness in a small motor boat. The camera, in another boat, catches it as a pulls away from the dock and glides around it as it turns,

The camera moves rightward with the boat but also moves in to show the woman sitting, apparently alone, in the boat.

A move further away establishes that Pedro is present, and we watch as the woman walks forward to sit beside him.

As she warns him of the danger of pursuing the kidnapping gang, the camera moves slowly in to emphasize her revelation that years before she had sold her baby to them

All the while the huge shantytown glides past in the background, emphasizes the extent of the poverty in the outskirts of Lima. The choreography of camera and action in this two-minutes-plus shot could hardly be bettered in a production with many times the budget. (A clip of this long take is currently posted on Youtube.)

The title seems to refer to the lullaby that Georgina sings, just calling her lost child “baby” because she never was given a name.

The film played in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, where it received positive reviews in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. It deserves further festival play, and we can hope that León can follow up with other films.

Sorry We Missed You (2019)

Then there is, Ken Loach, the veteran English filmmaker who continues to deal movingly with the plight of working-class people. In Sorry We Missed You–which deceptively sounds like a title for a comedy–tackles the gig economy and its grinding effect on one industrious couple and their children.

The inevitability of bad consequences seems obvious as the husband of the family, Ricky, agrees to become a driver for an express delivery service which transports packages for the likes of Amazon and other online sellers. He is not an employee but an independent agent, the supervisor emphasizes. Buying his own van supposedly will cost less than leasing, so he sells the family car for a down payment. His wife Debbie, a caregiver for home-bound elderly and handicapped people, is forced to take the bus to her widely scattered clients.

The couple’s long hours begin to tell on their teen-age son, who is turning into a school-skipping, graffiti-spraying delinquent, and their younger daughter, who is crushed by the stress of watching her family falling apart.

Loach is expert in depicting the challenges of such a job, from the pressure for drivers to load packages onto the van rapidly (bottom) to Ricky’s indecision over whether to risk a fine for illegal parking or deliver a package late (above). As he misses deadlines and skips work over family crises, the company’s sanctions and fines begin to accumulate. Ricky spirals into debt. Debbie, torn between duty to her family and the people who depend on her, faces similar problems in dealing with her helpless clients.

There is no happy ending here, though there is some suggestion that the dire situation of the family at least forces them to try and help each other out. Loach has created a plausible, gradual descent into near despair. He portrays the pressures of large companies and organizations that expect much of their “independent contractors” but offer little support in return.

Bacurau (2019)

At first glance, Bacurau represents a considerable departure from Kleber Mendoça Filho’s two previous films, both of which we saw at VIFF, Neighboring Sounds and Aquarius. Both dealt with unscrupulous methods used by real estate dealers to push people out of older neighborhoods to make way for gentrification. Now, co-directing with Juliano Dornelles (the production designer on the two previous films), Filho departs from the big city for a small village in the wilds of northern Brazil. The village, by the way, is imaginary, a fact that provides a running joke about the characters’ inability to find it on maps.

Someone in power wants the villagers to leave, again to make way for the exploitation of the land for undisclosed purposes. In a way, it’s not such a departure from the previous films as it seems. Blocked water sources and inadequate food deliveries have failed to budge the villagers, who make do on their own. The film opens with two villagers in a tanker truck full of water bound for Bacurau (above).

Having failed to uproot these determined peasants, the unseen power has brought in a group of wealthy hunters who are keen to gun down human beings and have been given carte blanche to exterminate the entire village. Delivery trucks appear with cargoes not of food but of dozens of empty coffins, a few of which are soon used for the first victims of the hunters (see top).

Despite the suspenseful and sometimes gory action, the film has considerable humor. It soon turns into a modern version of the politically charged Cinema Novo films of Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s. The peasants prove less helpless than they initially appear, and soon the hunted are hunting their hunters.

By this point members of the audience with whom we saw the film were cheering, and obviously there was a contingent of Brazilian speakers who got some jokes that we didn’t.

All in all, it’s a wild, entertaining film, though not for the faint of heart.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

Sorry We Missed You (2019).

Vancouver 2019: Happy endings, art-film style

Tehran: City of Love (2018).

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has several strong threads running through it: world art cinema, documentaries, Canadian cinema, and films about art and artists. Sticking to any one or two of these would make for a rich viewing experience. I gravitate toward the “Panorama” program of mostly fiction films from around the world.

At one of these films, Tehran: City of Love, the Iranian director, Ali Jaberansari, and scriptwriter, Maryam Najafi, were present for a Q&A session. Clearly the audience has been charmed by their tale of three remotely connected characters all seeking love. One questioner asked what the pair’s next project was, which must always be cheering to the filmmakers. Another audience member simply thanked them for the film, saying that after seeing several grim movies, it was a pleasant experience to find one so funny and entertaining.

[Spoilers to come]

Certainly Tehran: City of Love is an entertaining film, but its ending is bittersweet at best. All three protagonists, after brushes with romance, end up alone. All may have learned something along the way, but they are all saddened by their failures. This year I have seen a couple of other films where the happy ending consists mainly of the central character letting go of bitterness and becoming reconciled to his fate. It seems as though grim storylines with unhappy endings are a staple of the festival film, and even comedies often avoid sending their audiences out on an entirely cheery note. Perhaps there is an assumption that an art film that is too entertaining risks not being taken seriously by festival programmers. Luckily, these three were included in the VIFF program.

Tehran: City of Love (2018)

Tehran: City of Love presents three central characters who are looking for love. Each has a problem to overcome. Mina is an overweight receptionist who, apparently resigned to her single status, targets attractive men who visit the cosmetic surgeon. She calls each, speaking seductively and arranging a date. She shows up for the date but does not identify herself, instead watching the man from a nearby restaurant table until he gives up in annoyance and leaves. At a class on the “geometry” of love, she meets a pudgy man who begins a courtship

Hessam is a body-builder with three championship titles in his past, now working as a trainer. He receives a part in a dubious film project and at the same time begins training an attractive young man who aspires to a championship. Hessam’s attraction to his trainee is subtly conveyed (above), and the young man seems friendly and seems possibly to reciprocate Hessam’s feelings.

Vahid, a talented mosque singer specializing in funerals, is dumped by his fiancée. A friend counsels him to become more lively and cheerful by singing at weddings. Vahid quickly makes the transition, which seems to improve his mood. He becomes friends with Niloufar, a female wedding photographer, who likes him but–as we know and Vahid doesn’t–she is awaiting a visa to allow her to emigrate to Australia.

Disappointments result. Mina’s beau is a married man in the lengthy process of divorcing his wife. The young man notices Hessam’s interest in him and switches to a new trainer. Niloufar reveals her imminent departure from Iran.

Tehran: City of Love is an impressive film for a second feature. The script by Jaberansari and Najafi weave the three stories together skillfully, keeping each story and the thematic connections among them perfectly clear. One might expect the three protagonists’ plotlines to come together. Hessam does at once point come to Mina’s office to get Botox treatments (presumably motivated by the film he is supposed to act in or to make himself more attractive to the young trainee), but nothing comes of that. Mina is close friends with Niloufar, but although the two talk about Vahid casually, Mina never meets him. The three characters are by chance in the same space by the final shot, but they remain unaware of each other. The title, unless we take it to be ironic, suggests that each may try again to find a partner, but the ending only hints that each has at least gained something from his or her brush with love.

It is also beautifully shot in widescreen, often employing what David has termed the planimetric shot, with the camera axis perpendicular to the background (see above and top). During the Q&A Jaberansari mentioned some of his film influences. (He was trained abroad in Vancouver and in London, where he now lives.) These included Roy Andersson, Elia Sulieman, Jim Jarmusch, Aki Kaurismäki, Jacques Tati, Fassbender, and Buster Keaton. Although Tehran: City of Love does not resemble any of these directors’ films closely–there are few long-take scenes or physical comedy played out in long shots–the list makes sense, mostly in the tone of the film.

Jaberansari and Najafi provided some helpful cultural context. They shot the film with official permission and also have permission to release the film in Iran, though no date for that has yet been determined. Despite the implied homosexuality of one character, only two minutes of cuts were required for the domestic distribution permit.

The emphasis on body-building, both in the gym and the scenes of men exercising in a mosque, reflects the fact that without bars, night-clubs, and other forbidden gathering-places, gyms and body-building are one milieu in which men can come together, including gay men.

At one point Vahid is arrested while singing at a “private” wedding. The phrase seems harmless enough, but private weddings often include men and women mixing in ways forbidden in the public weddings at which Vahid had previously performed.

Australia, they note, is the new destination of choice for Iranians seeking to move abroad, replacing Canada to some extent.

Sometimes Always Never (2018)

This film is largely a vehicle for Bill Nighy, contributing a mix of comically self-centeredness and pathos as Alan, a retired tailor. Years before his elder son Michael walked out of the house during a game of Scrabble and has never been heard from again. Alan has since been looking for him, neglecting his younger son, Peter, as well as his daughter-in-law and grandson.

Scrabble looms large in the plot. In one extended series of scenes, Alan and Peter show up in a small town to view the body of a young man who might be the missing son. During an evening in a bed-and-breakfast, Alan hustles the husband of a couple staying there, pretending to be an ordinary Scrabble player and winning £200 off the henpecked husband (above). Only later is it revealed that they, too, are there to examine the same corpse. Alan goes first emerges tactlessly and cheerily saying that the body is not Michael, despite the fact that the couple is about to perform the same grim task.

First-time feature director Carl Hunter adopts a playful style which at times resembles that of Wes Anderson. As with Tehran: City of Love, there are the planimetric shots(on a beach in Crosby otherwise populated by Anthony Gomley’s life-size statues, at bottom, and above, in the bed-and-breakfast Scrabble game). The characters drive in cars with blatantly obvious back-projected motion, and there are black-and-white inserts and brief animations. All these stylistic touches help lighten the tone of the underlying misery of the characters, though they also stand apart from the fairly straightforward presentation of most of the scenes.

The growing closeness between Alan and his shy grandson helps add a positive side to Alan and prepares the way for the inevitable outcome, as he learns to value the son he has over the one who clearly will never return.

A White, White Day (2019)

Most small producing countries have managed throughout the history of cinema to make films, and Iceland has been no exception. It was not until the 1990s that its films started attracting attention on the festival and awards circuit, but only now and then. Even today the local feature production hovers around only four a year. Still, we have learned to consider Icelandic films must-sees when they show up on festival programs.

Benedikt Erlingsson’s films have shown here in Vancouver, and we reported on Of Horses and Men in 2014 and Woman at War last year.

This year the contribution from Iceland is Hlynur Pálmason’s A White, White Day, his second feature. (His previous feature, Winter Brothers, played at our 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival, but we were in the process of buying a new house and missed it.)

“A white, white day” is a local phrase describing weather conditions that cause land and sky to become indistinguishable. It’s a perfect metaphor for confusion, for loss of bearings. We see it both literally and figuratively in the film. The protagonist, Igimundur, is a middle-aged policeman on leave for depression following a car accident that killed his wife. The film opens with the accident, although we don’t yet know who the driver is, occurring on a white, white day.

There follows a mesmerizing series of shots from the same vantagepoint, showing a lengthy series of shots of a pair of small buildings in a rural landscape, including these two.

All atmospheres and times of day area shown, from the light fog of the top shot to the heavier fog of the lower one, from bright sunny days to dark nights. Horses wander through in some, cars drive up in others, and gradually the ramshackle yard and structures become a home. We first glimpse Igimundur in the lower shot, though we don’t yet know who he is. The renovation of the buildings to make a home for his daughter and son-in-law, along with his beloved granddaughter Salka. Where Igimundur will go once they move in is never mentioned. Clearly the project is his way of coping with his grief, while he increasingly scorns the lack of help he receives from his psychologist.

Soon, however, he comes to believe that his wife had been having an affair, and he becomes increasingly abusive and violent, even toward his police colleagues and in front of Salka. The happy ending, which seems a trifle abrupt, sees him finally reconciling himself to the past and regaining his loving memories of his wife.

A White, White Day depends less on humor than the other two films, despite its occasional comic touches. Instead it is an absorbing family melodrama that most audiences would find entertaining.

For a useful brief history of Icelandic cinema, see here. So far it doesn’t include Palmason, but I expect he will soon be added.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

Sometimes Always Never (2018).

Balancing three protagonists in THE FAVOURITE

Kristin here:

Given the current year-round feverish speculation about the Oscars, it was perhaps inevitable that the campaign for performer-awards nominees for the three leading ladies of The Favourite was what drew attention to their relative prominence in the film. As Gold Derby (the website subtitled “Predict Hollywood Races”) said during the lead-up to the announcement of the nominees, “The film inspired a lot of debate in the early days of the Oscar derby as to what categories the film would campaign its three actresses [for].” Ultimately it was decided to place Olivia Colman in Best Actress and Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz in Best Supporting Actress. (For those who are interested, this story gives a detailed run-down of those occasions on which two or even three performers from the same film were nominated opposite each other in the same category.)

Esquire was one among many media outlets stating the same opinion: “Yes, Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz are both leading players in The Favourite, and yes, it’s probably category fraud that they were submitted in the supporting category to bolster Olivia Colman’s chances to win Best Actress. It is what is, and we must live with the fact that these two will get the nomination.” Indeed, that was what happened.

Stone and Weisz showed good grace in reacting to the studio’s decision–wise even without the benefit of hindsight–to campaign for Colman as the sole best-actress nominee. They did not, however, suggest that she was the sole protagonist of the film. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Weisz remarked, “I think Fox Searchlight was quite brave to make a film with three really complicated female protagonists. It’s doesn’t happen every day, sadly.” Every year The Hollywood Reporter interviews prominent but anonymous Academy members about their opinions and preferences in the main categories. This year an unknown director complained of the best-actress race, “I don’t understand what [Olivia Colman’s] doing in this category, or what the other two [Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz] are doing in supporting–all three should be the same.” The notion that the three roles were roughly equal in importance was expressed widely during awards season. Google “The Favourite” and “three protagonists,” and many hits will show up in the trade and popular-press coverage.

This notion of three protagonists intrigued me. I believe that the structures of many classical narrative films depend to a considerable extent on how many protagonists they have, what those protagonists’ goals are, and what sorts of obstacles they encounter along the way–often obstacles that lead or force them to change their goals. I based my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999), partly on that idea. For close analysis I chose four exemplary films with single protagonists (Tootsie, Back to the Future,, The Silence of the Lambs, and Groundhog Day), three with parallel protagonists (Desperately Seeking Susan, Amadeus, and The Hunt for Red October), and three with multiple protagonists (Parenthood, Alien, and Hannah and Her Sisters).

Single protagonists are the commonest, and their obstacles are typically generated by single antagonists. Multiple protagonists are somewhat less so. They tend to break into at least two types. There are shooting-gallery plots like Alien, in which the protagonist is the one who, predictably or not, survives the gradual killing-off of the other main characters. Then there’s the network-of-relations plot, like Parenthood and Hannah, in which separate plotlines are acted out, with the protagonist of each related by blood or friendship to the protagonists of the others. More difficult to pull off is the multiple-protagonist plot where the characters are linked by an abstract idea and have minimal or tenuous relationships to each other–Love Actually being a masterfully woven example. (Would that it had existed when I wrote my book!)

The parallel-protagonist plot is relatively rare. I’m not talking about a film with two main characters who are closely linked and sharing the same goal. The buddy-film, most obviously two partner cops as in the Lethal Weapon films, is a common embodiment of this goal, as is the romance where the couple are in love from early on but face obstacles posed by others, as in You Only Live Once.

Parallel protagonists are not initially linked but pursue separate goals that usually bring them together. This might involve a romance conducted from afar, as in Sleepless in Seattle. One character may know the other and seek to be more like him or her, as in Desperately Seeking Susan and The Hunt for Red October. In those two cases, the main characters end by succeeding as they come together and become friends. (Hair would be another example I could have used.) In Amadeus, on the other hand, Salieri fails in his desperate attempt to replace Mozart in public favor and to essentially become him by stealing his Requiem and passing it off as his own.

The triple-protagonist plot

I never considered the category of triple protagonists, simply assuming they would belong within the multiple-protagonist films. Perhaps they do, but The Favourite raises the possibility that such films have a distinctive dynamic, somewhat akin to the parallel-protagonist plot but more complex, or at least more complicated.

Balancing two protagonists who have more-or-less equal stature in the plot is probably not much more difficult than the other types of classical plots. I think that’s largely because these two main characters can come together by the end and become the romantic couple or the buddies who could easily have been the main figures in a dual-protagonist film. Three protagonists, however, are very difficult to balance without one or two of them becoming mere supporting players by the end.

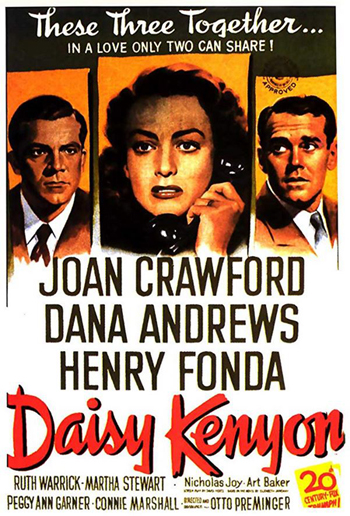

Across the history of classical filmmaking, there are probably a fair number of examples of such a balance being achieved. It’s not easy to think of more than a few, though. The first one that came to my mind is Otto Preminger’s underappreciated Daisy Kenyon (1947). In it Daisy is the mistress of a prosperous married lawyer, Dan, who refuses to divorce his wife and marry her. She meets a genial but traumatized war veteran, Peter, and marries him, but when her initial lover finally files for divorce, she is torn between the two. More about Daisy Kenyon later, the point here being that a triple-protagonist plot is not out-of-bounds for Hollywood and that two people struggling to win a third’s favors is an obvious situation to use in such a film.

The first half of The Favourite displays the long-established relationships between Queen Anne and Sarah. Sarah is stern and commanding with Anne, even cruel at times, and she runs political affairs in the Queen’s place. It is also clear, however, that the two love each other and that Anne, with her various physical and mental frailties, heavily depends on her friend. This half also traces the rise of unfairly impoverished Abigail, Sarah’s cousin. She ingratiates herself with Anne by helping nurse her gout and providing sympathy and deference; she even induces the semi-invalid Anne to dance.

Up to this point we are cued to sympathize with Abigail. She has been the innocent victim of misfortune and is treated cruelly once she arrives at court and Sarah hires her as a scullery maid. The midway turning point, as I take it, happens in the scene where Abigail shoots a pigeon and the blood spurts onto Sarah’s face. Immediately after this a servant arrives to say that the Queen is calling for Abigail rather than Sarah. Abigail is implied to have tipped the balance toward her being accepted as Anne’s favorite.

After this point, we suddenly start to see Abigail’s conniving side, and the pendulum swings as we grasp that Sarah has been displaced in the Queen’s affections through Abigail’s lies about her. In this second half, we are led to recall that Sarah, dominating though she is with Anne, truly loves her and is far more qualified to help run the state than frivolous Abigail is. By the end, all three have managed to make each other and themselves miserable, though Sarah still has her husband and manages to take exile abroad in her stride. None of them emerges as the most important character.

One might argue that Abigail functions as a conventional antagonist. After all, she drugs Sarah’s tea, nearly causing her death–and showing no compunction about it. Yet she, too, is pitiable. Her father gambled her away into marriage with a stranger, and early in the film she is bullied by the other servants. Sarah has her unlikable side and at one point attempts to blackmail Anne by threatening to make public the Queen’s love letters to her–an act that finally drives Anne to reject her. Before that rejection, however, Sarah burn the letters instead, confirming her inability to betray queen and country.

In a review on tello Films Karen Frost writes,“While Stone may receive a modicum more screen time than the other two, this movie really has three protagonists, all of whom are compelling in their own way.” I suspect a lot of spectators, including me, share this impression that Abigail is onscreen or heard from offscreen marginally more than Anne or Sarah. That said, it’s very difficult to measure the presence of each character, given how short the scenes are and how often the women come and go from the rooms where the main action is occurring. And does a scene like the one at the top of this section, where Anne and Sarah converse while Abigail stands mutely in the distance, give equal weight to all three? Perhaps, in that we are here conscious of the latter’s simmering resentment.

In a comparable scene, Abigail is pushing the Queen in a wheelchair. Anne becomes upset and tries to stagger back to her room. We follow her and concentrate on her struggle and emotions for some time before Abigail appears again with the chair. Should we consider this one scene between the two, or actually three scenes, with the two together, then Anne alone, and then the two together again? Even within scenes where two or three of the women are present, weighing their relative prominence in the scene presents difficulties.

The casting is crucial in such a film, since the relative prominence of the actors tends to affect our judgment of their characters’ importance. Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone were both Oscar-winning stars before The Favourite‘s release. Olivia Colman was not well-known in the US, but she had had a long and prominent career on television and occasional films in the UK, The Favourite‘s country of origin. Certainly as Anne she gains the audience’s sympathy early on and becomes plausible as a protagonist alongside the other two.

Scenes and twists

I decided that rather than attempt to clock screen time, I would count how many scenes each character had alone, how many involved two of them, and how many showed all three together. When I say “alone,” I mean only one of the three women is present, though often she is interacting with the main male characters, Lord Treasurer James Godolphin, Leader of the Opposition Robert Harley, and Baron Masham. Given the many very short scenes, the intercutting, the presence of the characters in the backgrounds when the others are emphasized, and the brief intrusion of a character into a scene that overall emphasizes one or two of the other women, my breakdown into segments can’t be precise.

I’ve compared the numbers of scenes devoted to the various combinations of characters in the first and second halves of the film, given the reversed situations of Sarah and Abigail in those large-scale sections.

First, the characters alone:

Anne has only 1 solo scene in the first half/3 in the second. (Total 4)

Sarah is alone 2 times in the first half/8 in the second. (Total 10)

Abigail is alone 7 times in the first half/9 in the second (Total 16)

Abigail’s larger number of scenes apart from the other two women occur largely because she is duplicitous and her situation changes drastically. Anne and Sarah behave straightforwardly, the former because she is too addled to be capable of deception and the latter because she is fundamentally honest, if sometimes brutally so.

Abigail’s duplicity must be revealed gradually. This is done to a considerable extent through two important relationships that help reveal that she is not the sweet young thing that we may have initially taken her to be. In the first half, Harley tries to bully her into acting as a spy in Anne’s bedchamber, passing on to him the political tactics and decisions of the Queen and Sarah. At first it is not clear that Abigail will comply. She also has aggressively flirtatious scenes with Masham. Initially she seems to be Harley’s victim and genuinely attracted to Masham, if in a rather eccentric fashion. Almost immediately after the midway turning point, however, Abigail passes secret information to Harley for the first time. Later, after Anne permits her to marry Masham, it is revealed that Abigail’s primary motive was to restore her lost social standing.

Scenes with Queen Anne with one or the other or both other women:

Anne with Sarah: 6 times in the first half/7 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with Abigail: 3 times in the first half/10 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with both: 6 times in the first half/5 in the second (Total 11)

Here the balance among the three protagonists becomes apparent. Whether intentionally or not, the scriptwriters gave Sarah and Abigail the same number of scenes alone with the queen. Abigail’s access to the Queen is naturally considerably greater in the second half of the film, as she gains her status as the favorite. Surprisingly, though, Sarah’s scenes with Anne are balanced between the two halves. I take this to reflect the Sarah’s determination not to be defeated and also the lingering friendship and genuine love that the two have shared since childhood. If we are to realize by the end that Anne has made a dreadful mistake by rejecting Sarah and sending her into exile, we must be reminded at intervals of how vital Sarah had been in helping Anne run the affairs of state.

The fact that Anne’s scenes with both other women are balanced between the two halves functions to allow us to continue comparing the behavior of both women toward the Queen. We slowly grasp Abigail’s perfidy and Sarah’s prickly steadfastness. The latter is made particularly poignant in Anne’s and Sarah’s final conversation, which takes place through the closed doorway of Anne’s room and ends with Anne rejecting her old friend, despite apologies and pleading.

Queen Anne is in a total of 41 scenes, Sarah in 44, and Abigail in 50, which does suggest that the latter has more screen time overall. The reason for this is probably not that she is more important, but that Sarah and Anne have an established, loving relationship at the beginning, which is easy to set up. Abigail must claw her way up from the scullery to the Queen’s bedroom, which takes more time to accomplish.

The screen time, however, is not the key factor. The film’s impact on the spectator depends to a considerable degree on our struggle to figure out which, if any, if these characters we might identify or sympathize with. There are such frequent shifts of tone and of what we know about each of them that our expectations are systematically undermined in the course of the plot.

In an interview on Deadline Hollywood, Tony McNamara, one of the scriptwriters, describes the effects of having three protagonists:

I thought it would be hard, but it was actually kind of liberating to have three, because it just gave you more options and places to go. Often, an action in a script has a reaction, but just one antagonist and protagonist. But because it’s three protagonists, there was always this cascading effect, and there were more twists. It was fun to have options, [though] there was work to do, making sure that the three were in balance, throughout.

Twists the film has in abundance. Our attitudes toward the characters change time and again. The scene in which Sarah starts letter after letter to Anne, trying to regain her favor, encapsulates all three women’s mercurial behavior. Her openings range from violent resentment (“I dreamt I stabbed you in the eye”) to fondness (“My dearest Mrs Morley”–her pet name for the Queen). The latter is the one she sends, but Abigail consigns it to the fire, finally making any reconciliation between her rival and the Queen impossible.

The ending, with its superimpositions of Anne’s rabbits over the faces of her and Abigail has been criticized as a failure to provide a satisfactory conclusion to the tale of the three protagonists. I’m not sure it is a failure of invention. Abigail’s insinuation of herself into the Queen’s favor began when she noticed the rabbits in the royal bedroom and elicited Anne’s tale of the loss of all seventeen babies she had had, with the rabbits acting as substitutes for them. Abigail had expressed an apparently deep sympathy, but in the final scene Anne sees Abigail capriciously and cruelly press her foot down on one of the rabbits. All illusions that her new favorite has loved her better than Sarah had vanish at this point, if they had not already. The two are portrayed as trapped in a relationship based on grief over unthinkable loss on the part of one and hypocritical manipulation by the other.

Preminger’s balancing act

Daisy Kenyon differs vastly from The Favourite, to be sure. Still, it’s a romantic triangle situation, and the woman who must decide between her two suitors is indecisive up until just before the ending. Dan and Peter are equally plausible as a final choice. Both have faults. Dan is content to carry on his adulterous affair with Daisy indefinitely, and Peter spies rather creepily on her after meeting her, secretly following her to a movie theater so that he can “accidentally” meet her when she comes out. Both clearly are in love with her.

Preminger also managed to cast three stars of more-or-less equal stature. Andrews had gone from supporting roles to the lead in Laura (1944) and was just coming off the success of The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Fonda had had both leading and supporting roles since the mid-1930s and starred in such films as Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Lady Eve (1941), and My Darling Clementine (1946). There is no Ralph Bellamy, the obvious Other Man, here.

There’s another resemblance to The Favourite, in that the man Daisy ultimately chooses then says something that creates a final twist–indeed, it’s the last line of the film. He reveals that not all is as we assumed, and we may be left wondering if, like Queen Anne, Daisy may regret her choice.

Another obvious triple-protagonist film is Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living (1933), which once again presents a romantic triangle centering on a heroine who is understandably indecisive in choosing between Gary Cooper (George) and Fredric March (Tom). She moves in with both with an agreement that they will avoid sex. She succumbs to George’s charms when Tom is away and to Tom’s when George is away, and when jealousy between the two men breaks out, marries her rich but boring boss (Edward Everett Horton). The pre-Code ending sees Gilda back with Tom and George in an arrangement that seems no more likely to remain sexless than the first one had.

Again the casting makes the two male protagonists seem equal. March and Cooper were both rising stars at the time, with March fresh off an Oscar win for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932). Cooper had achieved prominence with The Virginian (1929) and followed up with Morocco (1930) and A Farewell to Arms (1932).

This is not to say that all three-protagonist films have this triangle plot with an indecisive woman as the pivot. No doubt there are all sorts of other ways to balance three lead roles. Nor is it to say that three-protagonist films are so common and distinctive as to make me go back and revise Storytelling in the New Hollywood. Still, it’s interesting to see this kind of variant played on more familiar plot structures and to study how filmmakers can go about maintaining the necessary delicate balance.

David has an analysis of Daisy Kenyon‘s narrative maneuvers in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

Venice 2018: Big films on the big screen

Roma (2018)

Kristin here:

The Venice International Film Festival has a way of making the time fly–despite the occasional feeling when standing in line for a film that the doors will never open. It seems ages ago that we saw the early-morning press screening of First Man, and yet a mere three days have passed.

So far we’ve had the rare experience of each morning seeing another exciting, excellent, thoroughly satisfying film: First Man (which David has already written about), Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, and the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Can this last? Probably not, but the rest of the program offers rewarding films and so far seems to justify journalists’ claims that this year’s festival is boosting its already growing reputation.

A new (and laudable) tradition?

Last year we reported on the restored print of Lubitsch’s 1923 Rosita, which played on the evening before the official start of the festival, accompanied by an orchestra playing a restoration of the original score, edited and conducted by Gillian Anderson. This year the festival organizers followed up on that success by premiering the restored Der Golem (Carl Boese and Paul Wegener).

The large and enthusiastic crowd showed that, given the right presentation, this old film can attract those who think of the festival primarily as a place to see brand-new films before the rest of the world does. In fact, there’s also a healthy restoration thread running through the festival, though silent films tend not to figure in it.

Der Golem is noteworthy as one of a small number of relatively sympathetic Jewish-themed films that came out in the early to mid-1920s in Germany. (I recently wrote about this trend and the newly restored Der alte Gesetz.) It does not manage entirely to avoid stereotypes, but it should be pointed out that the Christian characters come across far worse.

Der Golem is an early entry in the German Expressionist film movement of the 1920s, having come out in 1920, the same year as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. Rather than using painted flats to create a stark, graphic look, as Caligari did, Boese and Wegener’s film features the droopy-clay look employed by Hans Poelzig, perhaps the finest of the Expressionist architects of the day. The result is that the clay buildings of the ghetto and the clay Golem seem at times to merge into each other.

The print looks much better than previous copies available. The Belgian Cinematek held an original negative, thought to be the one for German distribution, rather than the second negative shot for foreign distribution. Prints held in other archives supplied missing footage, as well as tinting and toning information and the graphics for some of the intertitles. The drop in clarity is apparent in the replaced passages, which, interestingly, include the sequence in which Rabbi Löw summons a demon to give him the magical name that will bring the Golem to life. Why this key moment was removed from the negative will probably remain a mystery.

The musical accompaniment was a modern composition by the six members of the Mesimér Ensemble. It fits the current fashion for highly dissonant scores, including the seemingly de rigueur vocal passages. It went well with the film.

I hope the festival organizers will continue this tradition of presenting restored silent films with musical accompaniment as a prelude to the festival. It makes for a relaxing transition into the more film-filled days to come.

Worth waiting for

After the critical and commercial success of Gravity (2013), which I wrote about here and here, there has been much curiosity about Alfonso Cuarón’s long-anticipated next film, Roma. Advance word had it that the film was to be shot in Mexico and in Spanish.

As I’ve already suggested, the film is splendid, and its black-and-white, widescreen images looked great on the huge Salla Darsena screen (from front row, center, of course). As with Zama last year, at the end David asked if we had just seen a masterpiece. Again neither of us had any doubt that we had.

The film may be based on Cuarón’s childhood memories, but it is hardly autobiographical. Instead the protagonist is Cleo, one of the indigenous maids who work for the upper-middle-class family whose dramatic arc parallels her own. Conventionally the maids Cleo and Adela would be present in the backgrounds of scenes or at best be supporting characters. Instead Cleo is our identification figure. Indeed, of the four children of the family, three of them boys, we never have a clue as to which one might represent the director.

The double plot revolves around two desertions. First the husband and father of the family departs on an ostensible trip to a conference in Canada, which is soon revealed as a cover for his leaving his wife for another woman. AT the same time, Cleo is dating a man who professes to love her but who deserts her the moment she reveals she is pregnant.

One might expect this sympathetic tale centered largely around Cleo to center on the family’s harsh treatment of her. Instead, the cruelty is muted and casual. The children clearly adore her, and she them, and the wife says at one point that she loves Cleo as well. Far from firing Cleo upon learning of the pregnancy, the wife comforts her, pays for medical treatment at the family’s hospital, and buys her supplies that she will need. Yet the unkindness is apparent as well. The wife curtly tells Cleo to clean up the dog turds in the courtyard–the accumulation of which provides a running gag. She also carelessly leaves Cleo, who cannot swim, to watch the unruly children at a beach with dangerous waves. This unreasonable demand precipitates one of the film’s most dramatic scenes, shot in an excrutiatingly suspenseful long take.

Cuarón directs with his usual utter control and flair. The film is set in 1971 (when the director would have been ten years old), and the period details are impeccable–especially the family’s Ford Galaxie, which provides a running gag whenf characters try to maneuver it into a narrow garage.

There are the expected long takes and camera movement. One fast tracking shot races along the middle of a busy street, keeping up with Cleo and Adela as they run joyously along block after block to enjoy their time off (top). In another scene, the camera wanders around the upper floor of a furniture store as Cleo shops for a crib, only to end with a pan to the windows and the revelation of the street below full of rioters.

In the ongoing controversy over Netflix’s reluctance to release its productions in theaters, it is particularly ironic that it should be the studio to produce Cuarón’s big-scale film. The promise is that it will be released “in select theaters.” If you live near one of those, don’t miss it.

Socialist Realism lives on

I had hopes of medium height that Mike Leigh’s Peterloo would live up to his previous historical films, Topsy-Turvy (1999) and Mr. Turner (2014). It turned out that Leigh had taken on a project with nearly insuperable obstacles.

While Topsy-Turvy had Gilbert and Sullivan, with its musical numbers and the innate drama of the pair’s occasionally testy relations, and Mr. Turner had painting and a single eccentric personality to focus on, Peterloo is about radical politics. The Peterloo massacre of 1819, which perforce occurs only in the climax of the two-and-a-half-hour film, is a major incident in the history of British radicalism and reform, and it is relatively well-known to the citizens of Great Britain. Elsewhere audiences are likely to be unaware of it.

As a result, Leigh must present a great deal of exposition about the issues and the lead-up to the peaceful protest march at St. Peter’s Field in the Manchester area. The exposition takes the form of a long series of speeches and conversations about those issues. The speeches are largely taken from the historical record, and they impart a great deal of authentic historical information, but they frequently overwhelm the drama.

Many of the speakers are historical characters, about whom we learn relatively little. Leigh humanizes the situation by focusing at intervals on a single poverty-stricken family whose adult men work at the local weaving mills and face dwindling wages from the mill-owners.The opening is clearly intended both to provide a bit of violent action as a hint of things to come, much later, and to introduce us to a young bugler who belongs that poverty-stricken family. We follow his trek home, his arrival there, and, briefly, his fruitless search for work.

If we expect him to become an active protagonist, however, we are disappointed, for he recurs only occasionally and passively thereafter. Instead we move around the various occasions on which speeches are given to rouse the downtrodden population to action. It must, after all, be plausible that roughly 70,000 people from the area would assemble in Manchester for a peaceable demonstration for the vote and representation in Parliament.

The local politicians who attempt to thwart the protest and possible resulting violence are portrayed as old, ugly, and nearly hysterical in their mingled fear of and contempt for the working classes. Their fears aren’t entirely unreasonable, given that the Luddite movement of 1812 led workers to destroy the labor-saving automatic looms and occasionally the factories that held them. Violence had killed people on both sides of the struggle. Leigh perhaps hints at the “machine-breakers” in his shots of the vast mill interior (above) and some of the dialogue, but only someone familiar with British history of the era would link the Peterlook protestors to the Luddites.

The result somewhat resembles the Soviet Socialist Realist films of the 1930s and 1940s, with their noble peasants and caricatured bourgeoisie and government officials. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, exactly, but the Soviet films seldom tried for actual realism, and Leigh cannot entirely give up his passion for naturalism. The result is an uneasy mixture in Peterloo‘s tone.

Despite its faults, the film is impressive. Produced, again ironically, by Amazon, the film has what must have been Leigh’s biggest budget to date. Authentic costumes have been created for actors and extras enough to at least suggest the tens of thousands present that day (below). The mill and the surrounding slum are convincing, and Leigh has managed to find some unspoiled landscapes to provide a relief from the grimness of working-class life in the era. Amazon will release it in the US on November 9, as part of the film’s slightly premature celebration of the 200th anniversary of the event.

Check out our Instagram page for ongoing photos from the festival.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome of us to this year’s Biennale.

October 31, 2018: Netflix has announced that it will give Roma a theatrical release, starting on November 21 in New York and Los Angeles; it will be in more theaters starting December 7 and open wider on December 14. It will been seen theatrically in 20 countries. There will be several theaters showing it in 70mm.

Peterloo (2018)