Archive for the 'PLANET HONG KONG: backstories and sidestories' Category

David Bordwell’s Hong Kong Connection: A Guest Post by Li Cheuk-to

David shopping during his first trip to Hong Kong, 1995

Kristin here:

By now many of you have watched the recording of David’s May 18th memorial service, linked in the previous entry. Some have written to tell me how moving it was and how many aspects of David’s personal life and career the speakers covered. Absent, however, was one of the greatest loves of his professional life: his many visits to Hong Kong and his book on that city’s cinema were represented only by a video recording of his acceptance of an Asian Film Award in 2007. It was a lovely moment, but no one who could present personal recollections of David’s Hong Kong connection was among the speakers.

Now, however, Li Cheuk-to, David’s close friend throughout his days in Hong Kong and our visits to Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, has written a piece that paints a vivid picture of David’s visits to Hong Kong. It conveys his deep enthusiasm for a national cinema that had largely been dismissed by critics and scholars in the West. The piece was posted online in Chinese on March 28, and Ah To, as we knew him, has kindly agreed to having the English version posted here.

Going back through the blog, I have found and linked entries written by David and describing some of the events that Ah To mentions below.

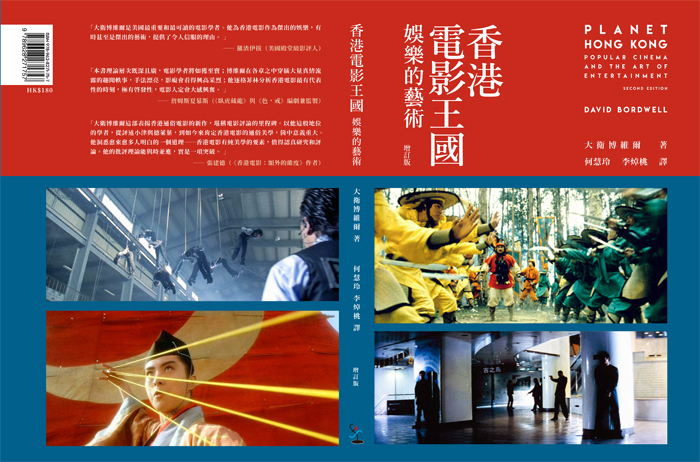

Planet Hong Kong

David in his element, 2000

David Bordwell passed away at the end of February, and the global mourning voices far exceeded the reaction to the death of any other film scholar. This proves that his wide circle of friends and profound influence go beyond the identity of a university professor. Apart from colleagues and students in academia, more responses came from friends he met at film festivals around the world, filmmakers, and fans who interacted with him through the blog “Observations on Film Art.” But what we feel most intimately connected to is his book Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, in which he celebrated Hong Kong cinema as a self-sufficient industrial system outside Hollywood, possessing its own unique aesthetics. While he also introduced films from many countries around the world in Film History: An Introduction, the only national cinemas he wrote individual books on were American and Hong Kong cinema.

Bordwell’s works are generally more enjoyable than most academic writings. They are remarkably well-written, free of pedantry, and often sprinkled with witty humor. What’s rare is that he isn’t deliberately trying to be accessible; rather, he enthusiastically shares his insights with readers with an open mind, without any hint of the condescending attitude that many scholars inevitably adopt. In this respect, he is as easy-going as his writings; we all enjoy conversing with him because he never makes you feel inferior. He is also a willing listener who is open to different opinions, making it easy to achieve fruitful two-way communication. Expert on Chinese cinema Shelly Kraicer believes that he perfectly embodies the democratic spirit of American scholars and the tradition of trusting students’ intelligence, in contrast to the elitism of the European academia. I can’t agree more.

A fanboy’s first trip to Hong Kong

Planet Hong Kong as one of Bordwell’s most popular works stands out in these aspects, but it is by no means a coincidence. Because he openly admits that he has been an otaku (geek, nerd, or enthusiast) since childhood, discovering Hong Kong cinema through the kung fu films of the 1970s (Five Fingers of Death, Jeong Chang-hwa, 1972, and Fist of Fury, Lo Wei, 1972), just like many Western fans of Hong Kong movies. He even screened some of them in his classes. Unsatisfied with the usual channels like cinemas and film journals, he subscribed to fan magazines and collected videotapes and laserdiscs to update his knowledge of Hong Kong films. Therefore, he embodies a dual identity of a small fan and a distinguished professor, yet he neither falls into the fanaticism of a fanboy nor keeps a distance with the subject of study like most scholars. Instead, he maintains a clear-headed, heartfelt love for these films.

In 1995, his first visit to Hong Kong to attend the Hong Kong International Film Festival became a pivotal turning point. It was not only the centenary of cinema, but more importantly, the festival’s programme that year broadened his horizons. The new friends he made there made him feel at home, and he fell deeply in love with the city of Hong Kong: This will always be the place!

He wrote about the awe he felt sitting in the front row of the Hong Kong Cultural Centre’s Grand Theatre watching Abbas Kiarostami’s Under the Olive Trees. He also had the chance to see the newly unearthed Love and Duty with Ruan Lingyu (Bu Wancang, 1931), as well as new prints of The Orphan, starring the young Bruce Lee (Lee Sun-fung, 1960) and The Eight Hundred Heroes (Ying Yunwei, 1938). The festival that year opened with In the Heat of the Sun (Jiang Wen, 1994) and Summer Snow (Ann Hui, 1995). He could rewatch his beloved Chungking Express (Wong Kar Wai, 1994) and catch up on Hong Kong gems from the same year like He’s a Woman, She’s a Man (Peter Ho-Sun Chan, 1994), The Private Eye Blues (Eddie Fong, 1994), The Final Option (Gordon Chan, 1994), and The New Legend of Shaolin (Wong Jing and Corey Yuen, 1994). (Below, David and Peter Ho-Sun Chan.)

During that year, he also attended the presentation ceremonies of the Hong Kong Film Critics Society Awards and the Hong Kong Film Awards, where he met his admired stars and directors such as Wong Kar Wai, Ann Hui, and Tsui Hark, feeling ecstatic like a fanboy. (Above, David presents the Best Director award from the Hong Kong Film Critics Society for Ashes of Time.) However, more importantly, through the friends he made at the film festival and his experiences walking the streets and marveling at the architecture of Hong Kong, he truly felt the vibrant energy, fast pace, and visual stimulation of Hong Kong cinema, realizing its inseparable connection to the place and its people.

He admitted to becoming addicted to visiting Hong Kong from that point on, continuously attending the film festival in March and April for seventeen years without interruption. In 1997, he wrote an article titled “Aesthetics in Action: Kung Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expressivity” for the Hong Kong cinema retrospective catalogue Fifty Years of Electric Shadows. The following year, he wrote “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” for the retrospective catalogue Transcending the Times: King Hu and Eileen Chang. In retrospect, these two articles were early drafts of what would later become Planet Hong Kong. The former used Lethal Weapon and A Hearty Response (Norman Law Man, 1986) as examples to illustrate the stylistic differences in handling action scenes between Hong Kong films and Hollywood, which he also presented during a three-day symposium at the film festival, where the audience erupted into thunderous applause after the screening of the car chase scenes from the two films – what a memorable moment!

In fact, in the two to three years around the time of the handover in 1997, every time he visited Hong Kong, he met with many Hong Kong filmmakers in preparation for his book Planet Hong Kong. One unforgettable memory was a late-night gathering at the end of 1997 with members of the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, where they talked until the early morning and even went karaoke together! Keeto Lam and Bryan Chang still remember that he sang “All Kinds of Everything” and “Losing My Religion.” During that time, we agreed to have the translated version of the book edited by me on behalf of the HK Film Critics Society. After he completed the first draft the following year, he sent me a copy for review. The scene of staying late at the office and discussing the content with him over a two-hour long-distance call is still vivid in my memory today.

A fixture in Hong Kong film culture

Seated, left to right, Shelley Kraicer, Athena Tsui, David, Erika Young, Nat Olson,

and standing, Ann Gavaghan, Tim Youngs, and Li Cheuk-to

Planet Hong Kong was published in 2000 (and in translation by Ho Wai-leng, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Critics Society, 2001) , and there was not enough time to write about Johnnie To in his Milkyway Image period in the book. However, when he was invited to be a visiting professor at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts in 2001, he visited the set of Running Out of Time 2 (2001) and the two hit it off immediately. Since then, every time David visited Hong Kong, Director To extended his hospitality, and in the second edition of the book in 2010, David filled this gap and resolved any regrets. (Below, from the left, standing Lau Ching-wan, Shan Ding, and Johnnie To; sitting, Ekin Cheng Yee-kin, David, and Kristin)

During this decade, the most special moment was in 2007 when he was awarded for “Excellence in Scholarship in Asian Cinema” at the inaugural Asian Film Awards, with Johnnie To as the presenter. Just like when he first visited Hong Kong, he took photos of and collected autographs from the surrounding stars and directors. Before the awards ceremony, in addition to discussing the content of the citation with Grady Hendrix, I also had Bryan Chang create a short complementary video featuring a stack of a dozen books that David had given me.

[Note: The online recording of David’s memorial service includes the presentation of the award, including Bryan Chang’s brief film. KT]

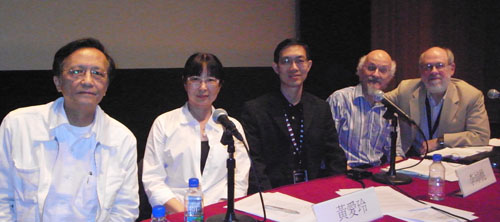

Two years later, he was invited to speak at a panel discussion on “The Controversial Centenary of Hong Kong Cinema” at the film festival, along with Law Kar, Frank Bren, and Wong Ain-ling, where they weighed the evidence for and against Stealing the Roast Duck (Leung Siu-po, 1909) and Zhuang Zi Tests His Wife (Lai Park-Hoi and Lai Man-Wai, 1914) as the first film made in Hong Kong.

Law Kar, Wong Ain-ling, Li Cheuk-to, Frank Bren, and David

However, what excited him the most at that edition of the film festival was probably the “A Tribute to Romantic Visions” retrospective celebrating the 25th anniversary of Film Workshop (co-founded by Tsui Hark and Nansun Shi), featuring screenings, exhibition, publication, lectures, and parties, creating a star-studded and bustling atmosphere. Additionally, the successful restoration and resurfacing of Fei Mu’s lost work Confucius (1940) was also a great pleasant surprise for him.

A fanboy’s last trip to Hong Kong

Unfortunately, around the same period, when he came to Hong Kong to attend the film festival, he experienced respiratory issues perhaps due to the air pollution in Hong Kong, often coughing uncontrollably. Athena Tsui remembers accompanying him to a private hospital for a late-night visit (to avoid disrupting the next day’s work), where they even summoned a radiographer in the middle of the night to take X-rays for him, and he quickly received the results, indicating no immediate danger. After returning to his home country, he showed the report to his own doctor, who greatly praised the professionalism, efficiency, and expertise of the Hong Kong medical staff, once again leaving him in awe.

Due to this chronic lung condition, he heeded the doctor’s advice not to come to Hong Kong for two years. In 2014, he accepted an invitation to join the jury for Young Cinema Competition at the film festival (other jury members included Bong Joon-ho, Karena Lam, and Christopher Lambert, above), marking his final visit to Hong Kong. Nevertheless, being able to see the director’s black-and-white version of Mother and engage in deep discussions with Bong Joon-ho could be considered as leaving a good memory, right? In the following years, the only occasion where he would meet with me annually was at the Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna, Italy at the end of June, where he always appeared alongside his wife, Kristin Thompson.

Kristin is also a renowned film scholar who co-authored two classic film textbooks with David, and their blog was co-written, as we all know. However, she is also an Egyptologist who conducts research in Egypt once a year, like David’s annual visits to Hong Kong. Over the years, she accompanied her husband to the film festival in Hong Kong once in 2000. Athena Tsui remembers their fondness for desserts from The Sweet Dynasty, such as walnut and almond soup.

David particularly enjoyed mango pudding and was a regular customer at Hui Lau Shan. Before the closure of KPS Video Express, he would always buy many Hong Kong movie laserdiscs whenever he visited Hong Kong.

[Note: Many of these laserdiscs are now in David’s and my collection in the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. KT]

In recent years, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we naturally missed the chance to meet again. Last September, I had planned to visit him in Wisconsin, Madison after attending the Toronto International Film Festival. Unfortunately, his health deteriorated, requiring hospitalization, and we missed seeing each other once again. Occasionally, we would receive emails from Kristin updating us on his condition. Eventually, we received the sad news of his passing. It was reassuring to know that in his final days, they would watch a movie together every night, and on the last night, they rewatched two episodes of The West Wing. For those who truly care, this was a comforting end.

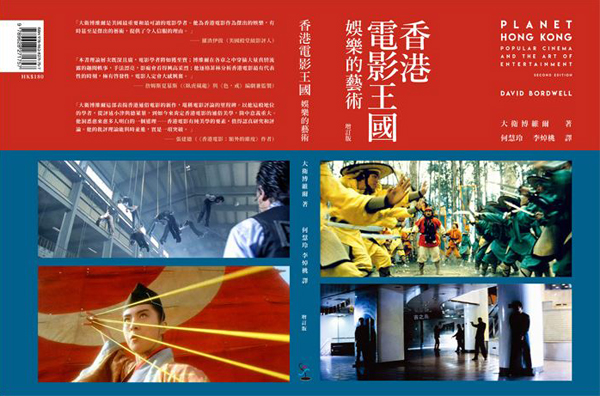

Lastly, it must be noted that six years ago when we decided to publish the translated version of the second edition of Planet Hong Kong (with the new material translated by Li Cheuk-to, aided by a few friends), he promptly wrote a new postscript for it without hesitation, for which we are truly grateful. Looking back today, when we sent him the printed translated version four years ago, he was still well amid the pandemic. Undoubtedly he was delighted to see that he finally completed a full circle with his connection to Hong Kong cinema. At the time, this Chinese version was meant to commemorate Wai-leng. Today, as David has passed away, I realize that this can also be seen as showing our utmost gratitude and respect to him.

The second edition of Planet Hong Kong is available for free here. There is still a notice about not copying the book for others, but that is left over from the days when David was selling his digital books online. The page where the book is available also has David’s description of how he came to love Hong Kong cinema, visited Hong Kong for the festival, and wrote the book.

The blog entries on Hong Kong that I have linked here are only a few of the many he posted. The rest can be found by clicking on the “National Cinemas: Hong Kong” link in the menu at the right.

Li Cheuk-to, photographed by David in 2000

RAINING IN THE MOUNTAIN at UW Cinematheque!

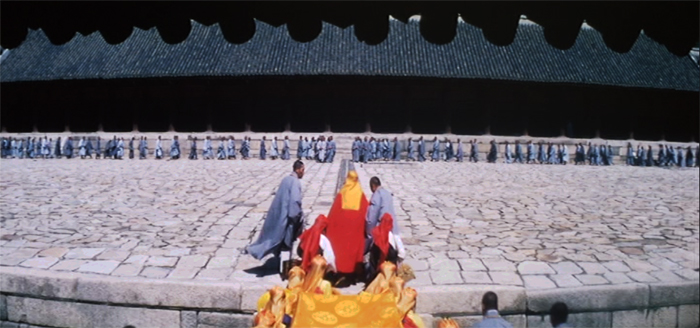

Raining in the Mountain (Hu Jinquan/King Hu, 1979).

DB here:

Thanks to friendly distributors, our University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque has sustained itself with virtual screenings every week. Coming up is one of King Hu’s most marvelous movies, Raining in the Mountain. In tribute, I joined Mike King to talk about it in the Cinematheque’s ongoing podcast series.

Best of all, thanks to Film Movement, you can watch the film through our Cinematheque’s virtual cinema!

For a limited time, the Cinematheque offers a limited number of opportunities to view Raining in the Mountain at home for free. To receive instructions, send an email to info@cinema.wisc.edu and simply include the word RAINING in the subject line. No further message is necessary.

Now, why should you watch it?

Well, it’s one of the most visually splendid Chinese films ever made. The Buddhist monastery that serves as the setting was actually assembled by editing together several South Korean locations, all majestic. Add in the brilliant color design and costumes of vibrant splendor, and you get a spectacle that David Lean would kill for.

Among this pageantry we find a cast of rogues, supple-spined thieves, selfish and lustful monks, and a couple of wise elders who see through the vanities of this world. A splashy finish is provided by a bevy of cascading courtesans wielding dazzling crimson and gold sashes–handy for trussing up a thief who has anger issues.

Key scenes take place in the monastery library, but the filmmakers were forbidden to shoot there. In a weird echo of the movie’s plot, the monk in charge was bribed and the crew stole the shots they needed. The footage was whisked off to Seoul, but the stratagem cost the producers a few days in custody.

The plot, as Mike and I discuss, is really three stories in one. There’s a heist scheme, in which a plutocrat and a general compete to steal a rare scroll. There’s a political intrigue, as monks jockey to succeed the retiring abbot of the monastery. And there’s a redemption arc, centering on an unjustly convicted prisoner who struggles to get on the path of righteousness. Much of the film is an attack on worldly selfishness. Even in the monastery, the monks are obsessed with money and have to be forced to do honest work. It’s a film about who deserves power, and right now, in our America, it’s welcome to see pragmatic humility rewarded.

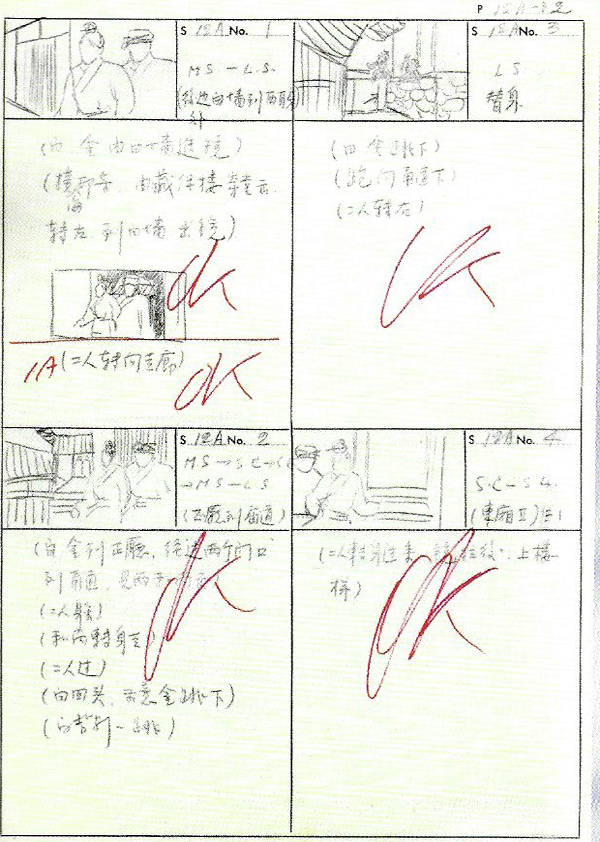

King Hu didn’t finish that many films. He took months to research his projects, and his meticulous planning of costumes and sets made him a slow worker. Unlike many Hong Kong directors, he prepared storyboards and worked out his compositions carefully. As he completed his shots, he checked them off with an “OK,” like the American filmmakers of the silent era.

The connection isn’t accidental. Like a silent filmmaker, Hu had a pictorial intelligence that conceived scenes shot by shot, without the pointless flourishes (arcing camera, slow track-ins) that today’s filmmakers are addicted to. He’s a fast cutter, but his locked-down compositions give you time to see everything.

As a result, Raining in the Mountain is not your typical martial-arts movie. For one thing, what usually counts as action–an aggressive fight, involving punches and kicks–doesn’t come along for an hour. In our conversation, I argue that King Hu replaces fights with zigzag chases, evasions, and hide-and-seek maneuvers. The geography of the monastery gave him vast opportunities for booby-trapped compositions. Figures and faces pop in and out of doorways, corridors, and windows.

The film is designed for the big screen, where details can blossom in distant crannies. So on a monitor (forget the tablet, the laptop, and the phone), you have keep your eyes peeled. While the two thieves drop into a passageway and race into the distance. . .

…a peekaboo framing gradually reveals why they’re hiding: a monk in blue emerges (tiny) in the ledge above them,

The spaciousness of the setting seems to have nudged Hu to try leading our attention to tiny bits of action in the anamorphic frame. Watch how he stages Chang’s preparation for a knife attack in a long shot. Gold Lock is crouching on the left, watching, like us, for the glint of Chang’s blade.

No close-ups are necessary. Hu trusts that we’ll keep up.

As usual in King Hu, there’s a quiet jubilation in watching the calm confidence of fighters leaping from room to room, hopping into a niche, or backflipping under a porch. Hu favors a slow buildup, capped by percussive bursts of action in rhythms recalling Beijing Opera. He cares less about traditional martial arts than about finding ways to create uniquely kinetic dramas of honor, heroism, and protection of the innocent. For him, combat is a staccato dance, and conflict is a test of moral rectitude.

As Mike points out in our conversation, King Hu looms ever larger in film history. A firm line runs from A Touch of Zen to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Hero (2002), and on to Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003). Tsui Hark’s swordplay films, especially The Blade (1995), owe a great deal to King Hu. (Not to mention John Zorn’s ear-bleeding album dedicated to the director and his incandescent female star Xu Feng.) King Hu remains one of the most original and engaging filmmakers in world cinema.

Film Movement’s site provides a trailer for Raining in the Mountain.

Thanks to Mike King and Ben Reiser for arranging the podcast, and Jim Healy and Pauline Lampert for coordinating so many superb programs under difficult conditions.

A Touch of Zen (1971-1972), which took three years to make, is King Hu’s official classic, and it displays many of his virtues. It’s now easy to see. (There’s a splendid Criterion disc, and it streams on Criterion and on Amazon Prime.) But don’t neglect his breakthrough Come Drink with Me (1966) and his other “inn films,” Dragon Inn (1968; also Criterion Channel ) and The Fate of Lee Khan (1973; streaming here). Perhaps his most dazzling experiment in action cinema is The Valiant Ones (1975), but I don’t know of any good copies on disc or elsewhere. I’m less enamored of Legend of the Mountain (1975), a ghost story, and All the King’s Men (1982), a tale of court intrigue, but it’s possible I’d like them more if I saw them now.

For more on King Hu, precious documents, essays, and recollections are available in Transcending the Times: King Hu and Eileen Chang (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 1998) and King Hu: The Renaissance Man (Taipei: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012). The storyboards above come from the Hong Kong volume. I recommend Steven Teo’s deeply informed books on Chinese film, particularly Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions, Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition, and his monograph King Hu’s A Touch of Zen. Hubert Niogret’s fine biographical study of King Hu is on the Criterion Channel.

I discuss King Hu’s work in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, in the essay “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” in Poetics of Cinema, and in other entries on this site. In the podcast with Mike, I mention Hu’s ingenious method of making swordfighters disappear and reappear; this entry explains how he does it and includes a clip.

Raining in the Mountain (1979).

Little stabs at happiness 5: How to have fun with simple equipment

Tiger on Beat (1988).

DB here:

Simple equipment includes, but is not limited to, knives, pistols, shotguns, ropes tied to shotguns, surfboards, chainsaws, etc.

Herewith another attempt to brighten your days with a choice film sequence that never fails to bring a foolish grin to my face. Apologies as ever to Ken Jacobs for my swiping his title.

Tiger on Beat (aka, but less pungently, Tiger on the Beat, 1988) is prime Hong Kong showboating. This final scene assembles some of the greats—Chow Yun-Fat, Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, Chu Siu-Tung (too little to do)–and near-greats like Conan Lee Yuen-Ba, who gets points for heedlessly executing the stunts Chow and Chow’s doubles can’t. Lau Kar-Leung (aka Liu Chia-Liang), one of Hong Kong’s finest directors, imbues both the staging and the editing with the crisp, staccato rhythm that this tradition made its own, and that few American directors have ever figured out. (It’s a long clip, so it may take a little time to load. In addition, our Kaltura operation is having problems, so you may want to try different browsers.)

Come to think of it, this little-stabs entry contains some fairly big stabs of its own.

The whole film is worth a look. Opening scenes feature Chow in outrageous threads, the very opposite of a cop in plainclothes, and there’s a fine car chase in which many risk life and limb. But this sequence, lit high-key so that every splash of saturated color pops, is for me the highlight, a tour de force of action cinema. Probably not for the kids, but what do I know about kids?

Sequences like this were what drove me to teach Hong Kong film and write Planet Hong Kong. They also impelled Stefan Hammond and Mike Wilkins to write Sex and Zen and a Bullet in the Head (1996), the most deeply knowledgeable fanguide to this glorious cinema. Stefan followed it up with Hollywood East: Hong Kong Movies and the People Who Made Them (2000). Now Stefan and Mike have effected a merger of these and updated and expanded them. They’ve also recruited a band of other Guardians of the Shaolin Temple: Wade Major, Michael Bliss, Jeremy Hansen, Jude Poyer, David Chute, Dave Kehr, Andy Klein, Adam Knee, Jim Morton, and Karen Tarapata.

The result is another indispensable volume, More Sex, Better Zen, Faster Bullets: The Encyclopedia of Hong Kong Film. The recommendations are sound, the plot synopses are nearly as much fun as the movies, and the authors have wisely retained chapter titles like “So. You think your kung fu’s. . . pretty good. But still. You’re going to die today. Ah ha ha ha. Ah ha ha ha ha ha.”

They weigh in on today’s sequence: “This gory Armageddon-duet consistently scores on Top Ten End-Battle Lists among HK film aficionados.” Makes me even more confident to recommend it to you. They add that the credits music is “a hard-rocking theme song by HK power diva Maria Cordero.” So I let it run.

I analyze this and other action sequences in this blog entry. An appreciation of Lau Kar-Leung is here.

For more little stabs, check out earlier entries in this series.

Chow Yun-Fat gets his daily dose of egg yolks (Tiger on Beat).

PLANET HONG KONG comes to . . . Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Film Critics Society has just published a Chinese long-form translation of the second edition of my Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. It can be ordered from the HKFCS bookshop. Sample pages and further information can be found here. I’m grateful to Li Cheuk To, Alvin Tse, and their colleagues for preparing and checking the text and finding nice pictures.

That second English-language edition dates back to 2011–a distant past in terms of the rapid changes in world cinema. So for this translation, I wrote a postscript last year, and at the suggestion of Cheuk To I’m posting it here. The book is dedicated to Ho Waileng.

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

Raymond Chow Man-Wai and Louis Cha Jin Yong both died in 2018. Journalists seeking a strong hook might take these unhappy departures as emblematic of changes in Hong Kong film culture—marking the “end of an era,” as we say. But Chow retired from the scene in 2007, and Cha finished revising his classics at about the same time. They stand, of course, as towering figures in Chinese cinema, but from my perspective today’s Hong Kong film is for the most part continuing processes that started quite far back. In other words, and much to my regret, the golden era ended some time ago.

I wrote the first edition of Planet Hong Kong in the late 1990s. As I explain in the book, I had been watching some Hong Kong films since the 1970s and got interested in the 1980s creative developments. By 1995, when I first visited the territory, those developments were already fading, though that wasn’t obvious to me. The local market was becoming unstable, regional tastes and investment sources were shifting, and the mainland economy was expanding. That age, undeniably golden, was ending.

When I interviewed local executives for the book, some said that they thought Hong Kong could become the “Hollywood of China.” Perhaps, they thought, all the experienced talents and financial and technical resources of the territory would be much sought after as China opened up its market.

By the time I came to revise the book in the early 2000s, such idealism had waned. As you’ll see in the pages that follow, it became obvious that Chinese authorities had shrewdly manipulated the market and the infrastructure to build up a powerful domestic industry. The rise of that industry, along with the waning of Hong Kong film, led to the biggest growth of a national film business ever seen in history. And those processes would assimilate Hong Kong creative talent on the mainland’s terms.

Now, as the 2010s come to an end, it seems that all the trends that I traced in the 2011 edition have continued, even accelerated. From 263.8 million viewers in 2010, mainland attendance has risen to over 1.6 billion in 2017. In 2010, the mainland claimed theatrical revenue of US$1.5 billion; in 2017 those were $8.27 billion. According to official figures, 970 feature films were produced in 2017. Although most of those were not released theatrically, it still remains a colossal achievement.

Over the same period, Hong Kong cinema continued in stasis. Production hovered between 42 and 64 annual releases. Theatrical admissions were likewise fairly flat, at an average of 25 million a year. Box-office revenues in 2010 came to US$179.4 million, and moved to $237.9 million in 2017. This is a substantial increase, but rising ticket prices (seen in every film culture) is likely one cause. Part of the rise, which occurred in the mid-2000s, is probably due to the emergence of 3D exhibition, which yields premium ticket pricing. And the greater part of that box office did not accrue to local films.

Certainly Hong Kong professionals at all levels were important resources for the growing mainland industry. Stars were and still are sought for major roles, and figures from decades ago, such as Chow Yun-fat, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Shu Qi, and Andy Lau Tak-wah, can still draw audiences. Directors Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, Stephen Chow Sing-chee, Peter Chan Ho-sun, Chang Pou-soi, Wong Jing, Johnnie To Kei-fung, and Stanley Tong Gwai-Lai found success in China, mostly with coproductions. The biggest coup of the era, Wolf Warrior 2 (2017; above) with its 154 million admissions, came from Wu Jing, a veteran actor and martial artist in Hong Kong films. Just as important, Edko, Emperor Motion Picture Group, and other local companies gained from producing movies for the mainland audience.

More broadly, the mainland box office was keeping Hong Kong film alive. A “local” film was likely to have mainland investment, and when it played there it had a good chance of making much more money than at home. SPL 2: A Time for Consequences (2015) took in less than US$2 million in Hong Kong but won over $90 million in China. Wong Jing’s From Vegas to Macau 2 of the same year captured $154 million there, as opposed to $3.6 million in Hong Kong. Through the 2010s, even a moderate success on the mainland could recoup far more money than it could in the tiny local market. To some extent the growing market to the north replaced the regional South Asian market that had sustained Hong Kong film in earlier decades. (How that market was lost is traced in Chapter 3.)

China cultivated homegrown directors as well, especially those who adapted conventions of Hong Kong and South Korean romantic drama and comedy to the local milieu. For any year, then, the top twenty films at the Chinese box office typically consisted of a mix. There would be imports (nearly all from Hollywood), domestic films by prestige directors (Zhang Yimou, Feng Xiaogang et al.), local genre films by younger hands, and two or three big box-office attractions steered by Hong Kong directors.

Coproductions that found mega-success in China didn’t register as strongly in Hong Kong. Tsui’s Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (2011), Jackie Chan’s CZ12 (2012), Peter Chan’s American Dreams in China (2013), Raman Hui’s Monster Hunt (2015), and Tsui’s Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back (2017) all failed to crack the local top ten. Stephen Chow seems to have lost his hometown following: Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons (2013) failed to score big there, while The Mermaid (2016) did, but in seventh place, below Marvel superheroes and the local thriller Cold War 2.

Not that the territory’s audience was particularly loyal to locally-sourced product either. The waning attendance I noted in Chapter 10 persisted. For the period 2010 to 2018, no more than two local films won a place in any year’s top ten. For three of those years, none did. In 2018, Project Gutenberg ranked number 12, the only local film to appear among the top thirty contenders.

Granted, in most countries, especially small ones, domestic films don’t get big box-office returns. Hollywood films dominate, with only one or two local productions finding a place on the year’s top ten. Still, those of us who remember when Hong Kong films ruled the local market have to see the stagnation as saddening. Nonetheless, with China offering many more opportunities for investment and rewards, it’s remarkable that there remains a local industry at all—and one turning out four or five dozen features a year.

Those films have tended to follow the templates established decades ago: romantic comedies, domestic dramas, films of social comment, and urban action pictures. Filmmakers have updated those genres with digital production and mostly skillful use of modern technologies of color control, computer effects, and elaborate camera movements, including the use of drones for aerial shots. But anyone familiar with classic Hong Kong film will recognize the persistence of traditional plots and story premises. Golden Job (2018) brings back the rascals from the Young and Dangerous series to execute a heist, under circumstances that strain their brotherhood. Project Gutenberg (2018) revisits the Chow Yun-fat mythos with a counterfeiting story (shades of A Better Tomorrow) that allows him to wear white suits, brandish guns in both fists, and participate in a twisty plot that owes something to the 1990s narrative stratagems I discuss in Chapter 9.

The continuity should hardly be surprising, because a great many veteran creators are still active. Producer Raymond Wong Pak-ming, who co-founded Cinema City and went on to create Mandarin Films and Pegasus Motion Pictures, continues to release films. Yuen Woo-ping was a choreographer and director in the 1970s and achieved worldwide fame with The Matrix (1999) and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000); he recently directed Master Z: The Ip Man Legacy (2018). Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, and many other directors from the 1970s remain top figures in a film culture that offers many opportunities to venerated talents.

Although I’ve long admired Hong Kong films in many genres, readers of of Planet Hong Kong know that I believe that the action film—as wuxia pian, kung-fu movie, or cops-and-robbers thriller—was the area of its most long-lasting contribution. The tradition of powerful physical action, gracefully executed and forcefully staged and cut, was a genuine contribution to the history of film as an art form.

For that reason it’s a pleasure to report that the “ordinary” action pictures of the last decade have by and large maintained that tradition. Donnie Yen Ji-dan, an actor who chooses intelligent projects, endowed films like Kung Fu Jungle (2014), the Ip Man vehicles (2008-2019), and Chasing the Dragon (2017) with vivid, exciting sequences. He and other filmmakers seem to have abandoned the looser camerawork of the early 2000s and returned to precision shooting: fixed camera, instantly legible compositions, and a flow of movement across shots that can accelerate, slow, or halt, all in the service of impact on the viewer.

Still, in the hands of a skillful craftsman any technique can work. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s White Storm (2013), a full-bore male melodrama in the John Woo manner, mixes run-and-gun handheld style with a revival of the forceful compositions and crisp editing of the heroic-bloodshed days. Cheang Pou-soi’s Motorway (2012) invests a simple plot with excitement through nearly abstract shots of cars gliding through streets and alleys, augmented by stretches of ominous silence.

Similarly, I see the positive legacy of the Infernal Affairs series (2002-2003) in franchises like Overheard (2009-2014) and Cold War (2012, 2016). While not as tightly contained as the trilogy, these films benefit from plotting that is less episodic and more finely woven than we find in the policiers of the 1980s. They also judiciously insert florid action sequences, creating a sort of middle ground between the bureaucratic intrigue of Infernal Affairs and the more extroverted spectacle of something like Police Story (1985)—or, come to think of it, any of Jackie Chan’s Police Story titles.

There’s much to be said about Tsui Hark’s PRC adventure sagas as well, particularly in their use of 3D. (The Taking of Tiger Mountain, 2014 above, is a mind-bending use of that technology.) But for my purposes here I’d like to focus on two other major talents that I analyzed in the second edition. Both made outstanding contributions to the action picture in the years since the second edition was published.

Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster (2013), despite being circulated in varying versions, remains for me a powerful achievement. It carries on Wong’s persistent experimentation with decentered narrative, following not only Master Ip Man but also his chief rival Razor and Gong Er, daughter of Ip’s one-time adversary. As I suggest in a blog entry this diffuse treatment of the major characters may bear the traces of a multiple-protagonist plot reminiscent of Days of Being Wild. In addition, through strategic flashbacks and shifts from character to character, this “chaptered” film evokes the interrupted and embedded story lines of other Wong films.

Stylistically, The Grandmaster makes fresh use of distended time and slow-motion imagery; these are conventions of the kung-fu genre as well as a signature of Wong’s work. More unusual is what I call in the blog entry the “mosaic” texture he builds up through close-ups that can be put in various places in one scene or another, or even one version or another. In general, I think that Wong alters the thematics of the martial-arts film by emphasizing Gong Er’s tragic dilemma: defeating the man who killed her father both sustains and erases her family’s legacy. And, as we might expect with Wong, the film strikingly parallels martial-arts prowess with impulses toward romantic love.

Another major film of 2013, Johnnie To Kei-Fung’s Drug War, is no less characteristic of its creator. (I analyze it in another blog entry.) A cat-and-mouse intrigue between crooks and cops, it depends heavily on our filling in gaps and reading characters’ minds. Police officer Zhang tries to penetrate a drug-smuggling outfit, and he devises a perfect To/Wai Ka-fai strategy: He sets up two meetings with two kingpins who don’t know each other. At each meeting Zhang impersonates the other guy. This game of shifting identities, of symmetry and doubling among roles, is a common narrative device of the Milkyway films, but in Drug War it’s given new urgency and a great deal of suspense. One economical shot brings the two unsuspecting gangsters together in the same frame as they leave and enter elevators.

At the same time, the informant Timmy is playing his own game—one that it may take a couple of viewings to decipher. As in The Mission (1999), many scenes of Drug War consist of men looking at each other, trying to divine hidden intentions—here, framed in the simplest possible shots, mere faces seen inside adjacent cars. Timmy’s eventual double-cross culminates in one of the cruelest shootouts to be found anywhere in To’s work; its bleakness recalls the end of Expect the Unexpected (1998). Throughout his career, To’s originality and craftsmanship in this rich genre have made him one of the great contemporary directors.

Wong completed only The Grandmaster in the years I’m considering, but To remained quite productive. Romancing in Thin Air (2011) and Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 2 (2013) returned to the mode of white-collar romance that Milkyway had made its own, while The Blind Detective (2013) combined that eccentric tone with an off-center cop premise recalling Mad Detective (2007). Life without Principle (2011; discussed in this entry) was a striking use of multiple-character plotting to make incisive points about the financial crisis.

Office (2015), an adaptation of Sylvia Chang’s popular play, was at once a flamboyant musical and an experiment in 3D. In Three (2016) To took up the challenge of a tightly circumscribed time and space, tracing the raid on a hospital ordered by a triad who’s there in police custody. Milkyway produced films by others, notably Motorway and Trivisa (2016), an opportunity for three first-time filmmakers to collaborate on a feature with three intersecting story lines. This last effort was in keeping with To’s dedication to creating programs and award competitions for newcomers to the industry. He remained one of Hong Kong’s most imaginative and tireless creators.

I should mention one more tendency, and it’s an encouraging one. Both editions of Planet Hong Kong pointed out that the Hong Kong people, contrary to the stereotype, actually cared a great deal about politics, especially after 1989. Recent years have seen a resurgence in films explicitly about activism in the territory. An early example is Matthew Tome’s documentary Lessons in Dissent (2014), a stirring account of struggles over educational policy and voting rights, featuring the most heroic 15-year-old I’ve ever seen. The 2014 Umbrella Revolution brought forth Evans Chan’s Raise the Umbrellas (2016) and Yellowing (2016; below) by Chan Tse Woon of Ying e chi There was also the ambitious speculative fiction Ten Years (2015), an ensemble of stories forecasting political repression in 2025. It’s very encouraging to see these efforts to insist on free speech and social criticism.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out how much classic Hong Kong film anticipated developments in Hollywood. The comic-book franchises that found new popularity with X-Men (2000) and Spider-Man (2002) and the Dark Knight trilogy (2005-2012) feature chivalric warriors with extraordinary fighting skills and weaponry. Like the knights-errant of wuxia fiction and film, these superheroes can leap high in the air and subdue villains with secret fighting techniques. Some, like Iron Man, have an equivalent of “palm power.”

Sometimes the American films have acknowledged their sources in Asian martial arts traditions, as when Batman trains as a ninja (Batman Begins, 2005) and Doctor Strange studies under a sifu in his 2016 film. The combat scenes, full of flips and somersaults, owe a great deal to the acrobatic traditions on display in Hong Kong cinema. If the result lacks the precision and visceral punch we find in classic Hong Kong films, it’s still worth noting that Westerners have learned that kung-fu, fights in mid-air, and elegant swordplay look cool on the screen. Hollywood should thank Hong Kong for helping invigorate the American action film.

A few words about what the original book tried to accomplish. At the most basic level, I wanted to understand Hong Kong cinema as an industry, an artistic tradition, and a cultural force. At the same time, I wanted to study it as an example of a popular cinema, one that developed strategies of storytelling and style and emotional appeal that were accessible to millions of people around the world. I wanted to analyze its unique contributions to the development of film art, so that meant I had to do some comparative work, situating Hong Kong film in relation to other traditions—most notably, that of Hollywood. At another level, I was interested in particular genres, especially the action film, and directors. As a result, parts of the book—mostly the “interludes”—are devoted to a particular filmmaker or group of filmmakers. And while I expected that many readers would already be Hong Kong film fans, I wanted to persuade skeptical readers that this national cinema was worth respect. This overall project I tried to amplify in the second edition you’re now reading.

Since the last edition, I have not followed Hong Kong cinema as intensively as I would have liked. Other projects have diverted me. But I have never lost my admiration for this cinema, this culture, and this citizenry. Watching Hong Kong films and visiting the territory have added a new dimension to my life.

From my first stay in 1995, when Li Cheuk-to introduced himself to me during the festival, through many visits over the decades, I have always treasured my friends there. So many people helped me in my research—people attached to the festival, to the archive, to the industry—that to list them all would add too much to this already overlong postscript. But they are mentioned throughout the book, and I hope they know how much I appreciate their generosity over the years. I’ll be happy if anything I’ve done here and elsewhere, in other writing and teaching, have helped film lovers better appreciate the astonishing contributions of Hong Kong film to world cinema artistry.

Among those valued friends was the kind and dedicated Ho Waileng. A tireless worker for the festival, she also translated the first version of Planet Hong Kong into Chinese. She remains in the hearts of everyone who knew her.

P.S. 10 August 2020: We in the US are now accustomed to being shocked but not surprised. I woke up to learn that Jimmy Lai, maverick mogul and publisher of Apple Daily, and many of his colleagues were arrested under the new “national security” law. It’s ironic that President Trump, who has reportedly sought to jail our journalists, moved quickly to place sanctions on Hong Kong earlier this year. The latest crackdown may be a response to the U.S. condemnation of the bill’s restrictions on free speech. (I discussed them here.) An arrest warrant is out for an American citizen living in the U.S. because he advocates democracy for Hong Kong. A coalition of Democratic and Republican senators and representatives have sponsored legislation to widen refugee status for Hong Kongers. Another irony: It’s called the Hong Kong Safe Harbor Act.

Ho Waileng at Angkor Wat, 2006. Photo by Li Cheuk To.