Archive for the 'Television' Category

POKER FACE: Detective off the grid

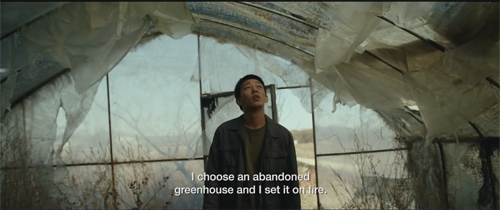

Poker Face, Ep. 10 (“The Hook”).

DB here:

Charlie Cale, an easygoing but tough young woman from New Jersey, has a unique gift. She can detect when someone is lying. She has exploited this in a career as an itinerant poker player, but after the word gets out about her ability, she winds up working as a waitress in a Las Vegas casino. A free spirit, she enjoys living from paycheck to paycheck, sharing beers and smokes with other staff. But the casino boss Stirling Ford Sr. learns of her gift and recruits her for a scheme targeting a rich patron.

That scheme collapses, and Charlie winds up having to flee across the United States. Driving the backroads, trying to stay off the grid, she keeps running into crimes in a wide range of settings. She stops at a Nevada Subway shop, a Texas barbecue joint, a stock-car race, a dinner theatre, a special-effects movie company, the venues of a touring heavy-metal band, a care facility for the elderly, and a remote mountain motel. We come to know each of these with remarkable specificity, noting details like lottery tickets and music amplifiers and Steenbeck flatbeds.

Charlie has the common touch. When she spots a lie, she’s likely to blurt out, “Bullshit!” She can freely talk and eat with working stiffs and is naturally suspicious of the plutocrats she keeps running into. She’s ready to deploy her ability to expose the less wealthy who want to exploit others. Eventually we come to learn that her sympathy for virtuous innocents may be compensation for her frosty relations with her family.

Charlie is the protagonist of Poker Face, a ten-episode series designed by Rian Johnson. Johnson is an admirer of classic mysteries. Earlier I’ve tried to chart his debt to Golden Age whodunits, as seen in Knives Out and Glass Onion. Unsurprisingly, he planned Poker Face as an homage and an updating of the TV show Columbo.

Charlie is the protagonist of Poker Face, a ten-episode series designed by Rian Johnson. Johnson is an admirer of classic mysteries. Earlier I’ve tried to chart his debt to Golden Age whodunits, as seen in Knives Out and Glass Onion. Unsurprisingly, he planned Poker Face as an homage and an updating of the TV show Columbo.

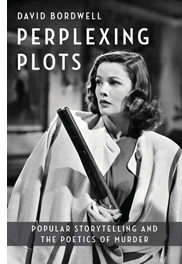

Apart from enjoying Poker Face on its own terms, I’ve admired its efforts to innovate. In my book Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder I argue that we have three useful tools for understanding plots. We can ask about the sequence of events in time; the way point of view structures our access to those events; and the way the events are broken into distinct parts. Noting how the plot handles time, viewpoint, and segmentation can help us grasp the ways Johnson has revivified the classic mystery–in ways that shape our experience.

I’ve had to indulge in spoilers, but I decided to confine those wholly to the first episode. Later episodes would justify a similar depth of analysis. And even in the first episode, I’ve tried to conceal major plot points when I could. In any event, I hope that people who haven’t yet seen the show (streaming on Peacock) might be intrigued enough to try it. It’s free although interrupted by commercials, but in a nifty use of segmentation Johnson manages to turn their timing to his advantage.

The inverted plot

Columbo, Ep. 1 (“Murder by the Book,” 1971).

The typical investigation plot begins with the crime already committed. The detective proceeds to unearth earlier events that led up to it. The alternative is, unreasonably, called the “inverted” plot. Here we witness the crime committed and perhaps are shown the motives involved. Then the detective arrives on the scene and we watch the investigator try to discover what we already know. We watch for slip-ups in what initially seems a foolproof scheme.

The inverted schema was developed most vividly in the Golden Age by F. Austin Freeman in a series of short stories. His sleuth, Dr. Thorndyke, arrives on the scene only after we have watched the culprit do the deed. The puzzle comes in trying to grasp how Thorndyke, using reasoning and scientific analysis, solves the mystery. In the process, he sometimes calls our attention to betraying details that we didn’t notice on the first pass.

This pattern of action comes off well in the short-story format, but it can be difficult to sustain in a longer tale. So the author may have the culprit resort to trying to impede or confuse the ongoing investigation, or to committing other crimes that need solution as well. These techniques come into play in Freeman’s novel Mr. Pottermack’s Oversight, which devolves into a battle of wits between Thorndyke and Pottermack.

A similar sort of stretching was common in Columbo, whose reliance on inverted plots inspired Johnson for Poker Face. The first episode broadcast, “Murder by the Book” (directed by Steven Spielberg), starts with disgruntled author Ken Franklin shooting his collaborator. Columbo, in his rumpled raincoat, doesn’t show up for the first eighteen minutes, and even after that he’s offstage during Franklin’s further schemings. These include creating a false trail for the crime and killing a witness who threatens him with blackmail.

We get some access to Columbo’s investigation behind the scenes, but the high points are his visits to Franklin. We enjoy the clash of slob versus snob when this obtuse flatfoot peppers the wealthy author with maddening questions–and always seems to accept a lie in reply. Eventually, when Franklin is trapped, Columbo reveals that he suspected him from the start; he just needed more evidence.

Despite its name, the inverted plot is usually linear. It traces events chronologically from crime to punishment, though flashbacks may provide chunks of backstory. This is where Johnson saw an opportunity to try something new. Assuming that viewers are familiar with the inverted plot schema, he juggles the sequence of events in unusual ways–exploring a different time layout in each episode.

A matter of timing

Poker Face, Ep. 1 (“Dead Man’s Hand,” 2023).

Except for the final installment, Poker Face follows the inverted schema: crime first, then investigation. But after we see the crime committed, the episode’s narration typically skips back and even “sideways” to show us circumstances leading up to the deed. Eventually the crime will be take its place in the chronological sequence–perhaps through a brief replay, or at least by reference in dialogue. Put another way, the crime segment is a kind of flashforward.

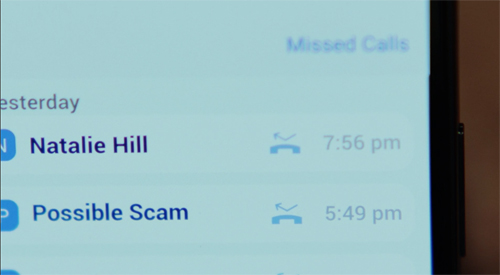

The first episode, “Dead Man’s Hand,” provides a tutorial in method. In a Las Vegas casino, the housekeeper Natalie finds horrific pornography on the open laptop of Kasimir Caine, a millionaire guest. She reports it to the boss, Sterling Frost Junior, and his fixer Cliff. They send her home. Cliff follows and shoots Natalie in her living room. He’s already shot her husband Jerry and he arranges the scene to look like a murder-suicide.

This block of brief scenes is followed by a linear story starting a few days earlier. Charlie works at the casino as a waitress, and she offers Natalie a place to stay after her drunken husband Jerry has raised a ruckus in the gaming room. In the meantime, Frost Jr. has learned of Charlie’s lie-detection talent and recruited her to watch Caine’s clandestine poker game by remote transmission. Frost will use her information about who’s bluffing in order to fleece Caine, while proving to his father that he’s a good manager.

Frost’s scheming with Charlie is interrupted by Natalie’s visit to report Caine’s pornography, so now the lead-in sequence falls into place. While Charlie is briefed further by Frost, Cliff is offstage killing Natalie and Jerry. The pivot is signaled by repeated dialogue: Cliff phones Frost (“It’s done”) and Frost resumes his explanation (“Where were we?”). The sequence of events is firmed up the next morning, when Charlie sees an online report of Natalie’s death.

The rest follows chronologically. Charlie feels guilty for not returning Natalie’s call, made shortly before her death.

Her phone record leads her to notice disparities in the timeline and investigate, while she and Frost Jr. are preparing for the Caine scam. A slip of the tongue allows her to spot Frost’s lie about Cliff’s call, and he realizes she’s on to him. The result is Frost’s death and his father’s demand that Cliff capture Charlie. She flees and begins her backroads odyssey across America.

Later Poker Face episodes elaborate this template. Sometimes the crime is embedded in a large block of consecutive scenes, with all the backstory shown (ep. 2, “The Night Shift”). After that we skip back to still earlier events centering on Charlie’s travels leading up to the night of the murder, which takes place while she is next door in a tavern. That’s why I said that some of the scenes move sideways, showing incidents near her. This “proximity principle” is pushed further in ep. 3, “The Stall,” when Charlie is hovering just offscreen in the opening scene, as the murder conditions are laid out; the replay will reveal that.

Another variant: The leadup to the crime is extended for much longer than in the earlier episodes, with the murder coming a third of the way through the show’s running time (ep. 4, “Rest in Metal”) and the replay witnessed by Charlie over halfway through. Later episodes adopt mixed strategies. They still start with the crime, or at least the planning, and skip back in time, but they seed the later blocks with ellipses, brief flashbacks, and replays. It’s as if the series were teaching us week by week to accept an increasing flexibility in moving forward and backward and sideways, while still adhering to the basic convention of the inverted plot. We’re also helped, of course, by dialogue and intertitles telling us where we are in the timeline.

The exception to these pyrotechnics is the last episode, “The Hook.” It’s stubbornly linear in tracing Cliff’s pursuit of Charlie. It starts ab initio, with Frost Sr. ordering him to find her, and following that with scenes from earlier episodes in which Cliff misses her. In a way, this entire prologue is a kind of flashback that ends with him seizing her as she leaves a Colorado hospital. The final episode is the most conventionally readable because it isn’t an inverted plot. The crime is missing from the opening but is saved, as is common, for a climactic revelation.

What makes all this variation possible is a coordination of segmentation, viewpoint, and causal-chronological order. The blocks of time are dictated by attachment to the killer (s) or to Charlie. Typically the lead-up to the crime keeps us with the culprits. The flashbacks following the first statement of the crime are motivated because they’re attached to Charlie, who is just getting involved with the situation. The later segments are either purely tied to her, or (as in the Columbo episode) devoted to the culprit’s efforts to thwart her inquiry. In “Dead Man’s Hand,” for instance, scenes of her investigation are garnished with moments in which Frost Jr. and Cliff plan ways to circumvent her. In all, these maneuvers create pretty clever plots, their segments accented by the way that the end of a block tends to initiate a commercial break . . . just as in old network TV.

Charlie’s little gray cells

Poker Face, Ep. 8 (“The Orpheus Syndrome, 2022).

How good a detective is Charlie? Given her gift, shouldn’t sleuthing be utterly easy? Johnson has engineered his series to give her several handicaps that require her to sweat as much as any hardboiled dick.

For one thing, as a working-class woman of fairly slight stature, she starts by facing a bias in favor of the bulky, wealthy men (mostly) whom she challenges. In addition, after the first episode, she’s on the run and has to be discreet. Going to the police about anything would inevitably reveal her whereabouts to Frost Sr. Moreover, during her flight she’s deprived of what helped her crack the first case: her cellphone access to the internet. After Frost Sr. threatens that he will find her, she destroys her phone so she can’t be tracked. But now she’s got to rely on other sources of information.

Even her gift proves problematic. Unless a suspect explicitly denies committing the crim, her bullshit detector can’t know the person is guilty. Not incidentally, this condition puts a fruitful constraint on the screenwriters. They have to make sure the culprit’s dialogue circumvents the sort of declaration that Charlie would see through.

Confronted by all these obstacles, Charlie is obliged to act like a classic detective. Let’s count the ways.

For all the pledges to strict reasoning, the traditional sleuth is often triggered by intuition, the sense that something is just not right here. (The prototype is Chesterton’s Father Brown, but even logicians like Ellery Queen and Hercule Poirot are sensitive to “atmosphere.”) Charlie’s gift is an extravagant form of intuition, since it’s both illogical and impossible to explain scientifically, so even when it doesn’t expose the killer it can set off a minor alarm. In the season’s first episode, her suspicion is aroused when Frost Jr. lies about his phone conversation with Cliff.

The classic detective spots or unearths clues, traces of the criminal’s action and pointers to identity. Charlie’s case against Frost Jr. and Cliff in “Dead Man’s Hand” is built out of such traditional clues as a problematic timetable, uncharacteristic behavior (Natalie didn’t sign out when she left work), and hand dominance (would a leftie wield a pistol with his right?). Later episodes of Poker Face are packed with physical clues, from wood splinters to discarded candy wrappers. As Jacques Barzun puts it, in the classic detective story “bits of matter matter.”

Charlie is especially good at spotting the absent clue, the dog that didn’t bark in the night-time. In the first episode, she notices that video footage of Jerry hustled out of the casino shows him passing through Security unscathed.

But if he had his pistol with him, that would have been detected–which implies that Cliff kept it. Yet Golden Age conventions demand fair play: we must have access to all the clues the detective has. In his films Johnson has adhered to this, and he has in Poker Face. So we are shown the Security station in the casino twice earlier. Early on, Cliff breezes through, counting on the staff’s recognizing him and letting him pass.

Later, Charlie is stopped because her phone sets off the scanner.

Consequently, when Jerry doesn’t set off the alarm as Charlie had, he can’t be packing the gun.

Reasoning puts the clues together, but sheer reasoning isn’t enough to justify arresting somebody. There must be evidence. Charlie often finds herself convinced of the killer’s guilt but lacking something that would stand up in court. And without a cellphone she can’t resort to tricking the killer into confessing on a hot mic. Yet some solid evidence is needed to clinch the case. The screenwriters have been ingenious in finding other damning records. Episodes recruit heart-monitor charts, 16mm film, CCTV footage, and digital audio and video captured by Charlie’s helpers or the culprits themselves.

In a classic whodunit, as we approach the climax, the detective is often blessed with a stroke of good luck that advances the solution of the puzzle. It’s often something apparently trivial–an overheard conversation or a slip of the tongue, or an irrelevant detail that inspires the detective to reinterpret a clue. In “Dead Man’s Hand,” Charlie spots the TV report of Jerry passing through Security not by diligent research but by sheer accident. She’s just dropped by the bar when the broadcast appears.

One more convention, one that the series adopts gradually: an alliance between detective and law enforcement. The classic detective cooperates to some extent with the police, either wholeheartedly (Queen, Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey) or grudgingly (Nero Wolfe). Even tough guys like Sam Spade, Nick Charles, and Philip Marlowe may exchange information with their friends on the force. At the start of Poker Face Charlie is a loner, but as the series proceeds, she gain an ally in the FBI, and because she helps him crack cases he comes to her aid on occasion. “At this rate, if I stick with you I’ll be head of the Bureau in a year.”

In all, Poker Face has engagingly modernized the inverted plot schema while benefiting from classic principles. Those permit the detective to show off powerful intuition, systematic reasoning, and Machiavellian cleverness in trapping the prey. In addition, the series has added to the gallery of admirable sleuths a hard-boiled but compassionate wise-guy woman. And it’s done with a strong dose of social criticism. This have-not from Jersey wreaks vengeance on those who victimize innocents.

Poker Face is scheduled for a second season, with Charlie once more on the run across America. We may expect that it will continue to show how ingenious play with time, viewpoint, and segmentation can revivify conventions of the whodunit. Keen fans learned to ask not only How will Charlie discover the crime we’ve seen committed? but also ask, with a teasing meta-curiosity: What ellipses and time jumps and hidden clues will we get this episode? Johnson seems unlikely to give up the game any time soon.

In Deadline, Antonia Blyth provides a very informative interview with Rian Johnson and Natasha Lyonne about Poker Face.

Martin Edwards discusses the inverted plot schema as part of a broader trend toward empirical, scientific investigation techniques in The Life of Crime (2022), Chapter 10. For a thorough survey of Freeman’s work, see Mike Grost’s discussion. Jacques Barzun emphasizes the role of physical clues in his superb essay, “Detection and Literature,” The Energies of Art: Studies of Authors Classic and Modern (1956), 313.

I discuss the inverted plot in more detail in Chapter 5 of Perplexing Plots, considering it as a hybrid of the pure investigation plot and the psychological thriller.

Poker Face, Ep. 3 (“The Stall,” 2023).

Calm that camera!

Succession (2023).

DB here:

Thanks to our Wisconsin Film Festival, Ken Kwapis paid us a visit. Director of The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and many other features, Ken also has experience directing TV, notably The Office. He’s a generous filmmaker, and he radiates enthusiasm for his vocation. I took the opportunity to talk with him about camera movement in contemporary media. He taught me a lot, and what I’ve come away with I share with you.

Camera ubiquity, with a vengeance

In the early silent era, fiction filmmakers around the world discovered what we might call camera ubiquity—the possibility that the camera could film its subject from any point in space. This resource was more evident in exterior filming than in a studio set, so early films often display a greater freedom of camera placement when the scene is shot on location.

At the same time, filmmakers began realizing the power of editing. This technique offered the possibility of cutting together two shots taken from radically different points in space. Yet an infinity of choices is threatening, and some filmmakers, mostly in the US, constrained their choices by confining the camera to only one side of the “axis of action,” the line connecting the major figures in the scene. Different shots could cut together smoothly if they were all taken from the same side of the 180-degree line. The result was the development of classical continuity editing. The director was expected to provide “coverage” of the basic story action from a variety of angles, but all from the same side of the line. Classical continuity was in force for American films by 1920 and was quickly adopted in other national cinemas.

The one-side-of-the-action constraint was encouraged by the fact that much filming of staged action took place on a set, designed according to the theatrical model. The camera side of the space was behind an invisible fourth wall, like that in proscenium theatre. To some extent directors compensated for the limitation on camera position by fluidly moving actors around the frame, from side to side and into depth or toward the viewer. Still, the “bias” in choosing setups was reinforced by the increasing weight of the camera in the sound era, which made it hard to maneuver within both interior and exterior settings. Camera movement in a more or less wraparound space was possible, but it was usually very difficult. It commonly required a dolly or crane on tracks to prevent bumps.

Technicolor filming, with its monstrously big camera units, reinforced the bias toward proscenium sets, 180-degree space, and a rigid camera. So did the postwar vogue for widescreen cinema. But in the 1950s filmmakers were also exploring the possibility of lighter, more flexible cameras. The body-braced cameras often produced bumpy, slightly disorienting images but yielded a more “immersive” space that gave the story action immediacy and spontaneity. By the early 1960s, handheld camerawork was being seen in both documentaries and fiction films. At the same time, fiction filmmakers were gravitating toward more location filming. In addition shooting on location with portable cameras promised greater savings on budgets, an attractive option for both independent and mainstream directors.

Handheld shooting was becoming more common in the 1970s, when its problems were overcome by the invention of the Steadicam, first displayed to audiences in Bound for Glory (1976). This stabilizer permits the operator to move smoothly through a space.

The new device was more than simply a substitute for a camera on a dolly and tracks. Ken pointed out to me that the Steadicam encouraged the increasing use of the walk-and-talk shot showing two or more characters striding toward a constantly retreating camera. This proved to be an efficient way of covering pages of dialogue. Beyond that, the Steadicam became an all-purpose camera for filming any sort of scene.

Over the same years, directors embraced multiple-camera shooting—originally aimed at handling complex stunts—for every scene, and they recruited A and B cameras, often mounted on Steadicams, for ordinary dialogue scenes. In most cases, the B camera was mounted alongside the A, but with the B camera in other spots there was a certain erosion of the axis of action. Now a conversation may be captured from a greater variety of angles than classical coverage would favor. Filmmakers have replaced 180-degree staging and shooting with what’s called 250-degree coverage. In The Way Hollywood Tells It I drew an example from Homicide: Life on the Streets. A free approach to the axis of action is common today, as in this example from Succession (2023).

A rough sense of the axis of action is maintained, and there are matches on action, but our vantage “jumps the line” as well. Moreover, the camera is constantly moving within the shots. It’s panning to follow or reframe the characters, sometimes circling them or abruptly zooming, and always wavering a bit, as if trembling. What some Europeans call the “free camera” is very common nowadays, and Ken and I talked mostly about this creative option.

Eye candy

By now, many filmmakers have chosen to make nearly every shot display some camera movement independent of following moving characters. This tactic was noted and recommended in a manual by Gil Bettman (First Time Director, 2003). (Readers of The Blog know of my fondness for manuals.) “To make it as a director in today’s film business, you must move your camera” (p. 54). The risk is making the audience more aware of the camerawork than of the story, so Bettman adds:

A good objective for any first time director would be to move his camera as much as possible to look as hip and MTV-wise as he can, right up to the point where the audience would actually take notice and say, ‘Look at that cool camera move.”

Like cinematographers in the classical tradition, Bettman declares that the camerawork should be “invisible” (p. 55). By now, you could argue, the predominance of camera movement has made it somewhat unnoticeable. Ordinary viewers have probably adapted to it.

One factor that aids the “invisibility” of camera moves is the speed of cutting. If the shots are short, the viewer registers the camera movement but probably doesn’t have time to notice whether it’s distracting or not. The effect of this isn’t restricted to action scenes. Even dialogue scenes may catch conversations up in a paroxysm of character reactions, camera movement, and swift editing. Creating these rapid-fire impressions, it seems to me, is what a lot of modern filmmaking seeks to do, at least since the early 2000s. It’s sometimes called “run and gun” shooting. Here’s an instance from The Shield (2003), with sixteen shots in less than a minute.

Arguably, Hill Street Blues (1981-1987) popularized this look for the police procedural genre, when DP Robert Butler urged his team to “Make it look messy.”

This sequence and the Succession passage points up another factor. Knowing that their films would ultimately be displayed on TV, some directors began “shooting for the box” by using tighter shots and closer views. TV directors such as Jack Webb were already working in this vein of “intensified continuity,” and many others had started their careers in broadcast drama and accepted the impulse toward forceful technique. Television has long demanded that the image seize and hold viewers, likely sitting in living rooms and prey to many distractions. Fast cutting and constant camera movements keep the viewer’s eye engaged. No surprise, then, that our TV programs present a fusillade of images that make it hard to look away.

Constant camera movement has another benefit. Many camera movements tease us. The start of a shot suggests that the camera will bring us new information, so we must wait for the end. Filmmakers love a “reveal,” and even a small reframing can suggest the camera is probing for something new to see. By now, however, filmmakers can play with us and use camera movement to flirt with our attention: the shot can begin with a clear image but drift away to conceal the main subject. I first noticed this almost maddening stylistic tic in The Bourne Ultimatum (2007), but it crops up occasionally elsewhere. In one scene of The Shield (2006), the camera slides behind a character, finds nothing to see, and slides back.

The peekaboo reframing would seem to throw the viewer out of the story in just the way that worries Bettman. I’m inclined, though, to think that it is part of a general, and fairly recent, expansion of viewers’ tastes. Self-conscious technical virtuosity has long been an attraction of mainstream filmmaking, and audiences have responded with appreciation. Think of Busby Berkeley or Fred Astaire dance numbers, or the railroad junction scene in Gone with the Wind. I suspect that many members of today’s audiences now happily say, “Look at that cool camera move” and don’t mind being pulled out of the story. (I’d say, though, that they aren’t being pulled out of the film, but that’s matter for another blog entry.)

This tendency would accord with what Bettman calls the taste for eye candy. For him, this seems to consist of bursts of light or color, usually produced by camera movement. More generally, I think audiences would consider impressive sets, striking costumes, and good-looking people to be eye candy. And now, I suspect, flashy camera work counts as eye candy too. The case is obvious with the showboating following shots in Scorsese and De Palma, but I think it applies to the jagged, in-your-face techniques seen in run-and-gun sequences. Advocates of the silent film as a distinct art never tired of insisting that cinema was above all pictorial. “The time of the image has come!” thundered Abel Gance. It took a while, but now that people compete for bigger home screens we have to admit, for better or worse, that everybody acknowledges that film is a visual art.

Many flies on many walls

Most moving shots today don’t utilize the Steadicam, whose usage needs to be budgeted and scheduled separately. The run-and-gun look is well served by modern cameras designed to be handheld. DPs and operators know that a wavering, even rough shot is acceptable to most modern audiences, and filmmakers seem to assume that handheld images lend a documentary “fly-on-the-wall” immediacy to the scene. In addition, wayward pans, swish pans, and abrupt zooms are felt to enhance that sense that we’re seeing something immediate and authentic. (Flies are easily distracted.)

Problem is, this approach is far from what a real documentary film looks like. True, the individual images might be rough, but their relation to one another is quite different from those in a documentary. For one thing, they occupy positions that documentary shots can’t achieve. Shot B may be taken from a spot we’ve just seen to be empty in shot A, as in the sequence from Succession. As Ken put it, “There’s no such thing as a reverse angle in a documentary.” Or shot B may be taken from a very high or low angle, where a camera is unlikely to perch, as in this passage of The Shield (2007) which hangs the camera in space peering through a railing.

Sometimes shot B will represent the optical viewpoint of a character, which is unlikely in an unstaged documentary. Putting it awkwardly, the free-camera style achieves a greater degree of camera ubiquity than we can find in a standard documentary. (Years ago, I made this point in relation to The Office.)

For another thing, the flow of run-and-gun shots always captures the salient story points. A documentarist, with one or two cameras following an action, is still likely to miss something significant (and to cover the omission with elliptical editing and continuous sound). But the modern method offers its own rough-edged equivalent of classical coverage. The action remains comprehensible. Sometimes the camera will even wander off on its own to frame something the characters aren’t aware of, providing a modern equivalent of classical “omniscient” narration.

What we have, I think, is a modern variant of the one-point-per-shot mandate of traditional editing, but featuring shots of that evoke greater “rawness” than studio filming did. And maybe it’s not as modern as we think. Here’s a sequence from Faces (1968), complete with walk-and-talk, or rather stagger-and-talk, as well as camera ubiquity and matches on action that would be difficult in a documentary.

I’d argue that John Cassavetes, much admired by filmmakers who followed, supplied the prototype for today’s run-and-gun look. Admittedly, it’s been stepped up; I suggested in The Way Hollywood Tells It that intensified continuity has been further intensified.

Nervous energy

Intensified how? Apart from all the swishes and zooms and focus changes, some bells and whistles aim to enhance the sense of “energy” attributed to the style. The peekaboo framings I mentioned would be one instance. Here are some others.

The shot, distant or close, which simply trembles. Let’s call it the wobblecam. It suggests the handheld shot, but it’s brief and seems shaky just to evoke a sort of vague tension. Wobblecam shots are so common now that entire scenes are built out of them, as in the Succession clip.

The arc: In filming TV talk shows, how do you keep viewers glued to the screen? One option is what a 1970 manual calls the arc. Here the camera travels in a slow partial circle that refreshes the image gradually. The framing reveals constantly changing aspects of the panelists and is a nice change from master shot/ insert editing. I remember this as common in 1950s programs.

The “roundy-round” (thanks, Ken): This extends the arc to 360 degrees, circling around one or more characters, urging us to watch for bits of action or dialogue—usually timed for maximum visibility. It’s also used to convey a character at a loss, say mystified by which way to turn, or characters embracing (whoopee). The technique can be found sporadically before the 1990s, when it becomes quite common. Ken pointed out that the roundy-round was extensively used on E. R. to underscore time slipping away during life-and-death surgery.

The “roundy-round” (thanks, Ken): This extends the arc to 360 degrees, circling around one or more characters, urging us to watch for bits of action or dialogue—usually timed for maximum visibility. It’s also used to convey a character at a loss, say mystified by which way to turn, or characters embracing (whoopee). The technique can be found sporadically before the 1990s, when it becomes quite common. Ken pointed out that the roundy-round was extensively used on E. R. to underscore time slipping away during life-and-death surgery.

The slider: The enhancement I find most distracting is the camera’s slow leftward or rightward drift while filming static action. Usually it’s a master shot, but it doesn’t have to be, and it can sometimes interrupt a series of close views. Unlike the wobblecam, this is more teasing because we’re used to such a shot revealing something. It doesn’t, but I think it holds out the promise and keeps us watching.

Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema I came to realize that supply companies created lighting and camera devices designed to meet the developing needs of filmmakers. Thanks to Ken, I learn that this tradition continues. You can buy or rent gear that will enable arcs, roundy-rounds, and the slider (right). Both in technique and technology today’s Hollywood is a continuation of yesterday’s.

If a director constantly relies on camera movement, there’s no reason to object. The elegant moves of Ophuls or Mizoguchi or of McTiernan in Die Hard provide the sort of continuous engagement and ultimate pictorial payoffs that justify the technique. My examples illustrate more gratuitous camera moves, choices that “add energy” but once they’ve become conventional, seem wasteful. Usually, they reveal nothing and end up minimizing the power of a gradual reveal when it comes along.

But who am I to complain? Film styles change under production pressures and artistic inclinations. As a student of film history, I have to study what’s out there. Still, run-and-gun remains only one option. There are still lots of films and shows, like Tär and The Woman King and Barry, that rely on rigid camera setups and discreetly motivated movements. (Ken’s Dunston Checks In (1996), shown to an appreciative crowd at the festival, is a good example.) Another alternative is providing precise shot breakdowns that feature unusual “eye-candy” angles, as in Better Call Saul’s views from inside mailboxes and gas tanks. That trend constitutes another way to expand options within camera ubiquity. There are also the long-take films in which complicated camera moves preserve the patterns and emphases of classic continuity. (See the discussion of Birdman.) And then there’s the effort by Wes Anderson to go in the other direction, to submit to constraints far more severe than classical shooting—an austere refusal of camera ubiquity.

I must ask Ken about all these options too. Next time, I hope.

Thanks to Ken Kwapis, who enormously expanded my sense of the practical choices available to the filmmaker.

The TV production manual discussing the arcing shot is Colby Lewis, The TV Director/Interpreter (New York: Hastings, 1970), 131-132. Other mobile framings are reviewed in the same chapter.

For examples of filmmakers believing that the rough-edged style is like documentary shooting, see remarks on Succession in Zoe Mutter, “Fury in the Family,” British Cinematographer and Jason Hellerman, “How Does the ‘Succession’ Cinematography Accentuate the Story?” at No Film School. Butler’s comments on Hill Street Blues are quoted in Todd Gitlin, “’Make It Look Messy,’” American Film (September 1981) available here.

You can feel the thrill of silent-era creators and critics in realizing the possibility of camera ubiquity. Dziga-Vertov celebrated the power of the Kino-Eye to go anywhere, while Rudolf Arnheim saluted cinema’s ability to provide unusual angles that bring out expressive qualities of the world. What would they make of a shot like this below?

Better Call Saul (2015): Extremes of camera ubiquity.

When worlds collide: Mixing the show-biz tale with true crime in ONCE UPON A TIME . . . IN HOLLYWOOD

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

Jeff Smith here:

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood might turn out to be the buzziest film of 2019. Some of this water-cooler talk is due to its unusual status within an ever-enlarging field of true crime stories. (Call it a “not quite true” crime story.) Indeed, the genre is hotter than ever thanks to a bevy of new podcasts, telefilms, and miniseries.

Industry analysts, though, are also keen to interpret Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office fortunes. As that rare big summer release that is neither a sequel nor a franchise title, it can be seen as a test of whether original content can survive amidst heavily marketed, presold tentpoles.

The lesson so far? To quote William Goldman, “Nobody knows anything.” In The Washington Post, one unnamed studio executive warned, “I don’t see any blue-sky meaning here.” The executive added, “This movie has assets that almost no other film has. That’s what drove it.” At least one of those assets is Tarantino himself, who is a brand, if not a franchise. Fans know what to expect in a Tarantino film, which is why the film is sui generis when it comes to this summer’s slate. Due to its unique IP, it can’t really be compared with films like Men in Black International or Spider-man: Far from Home. Yet thanks to Tarantino’s larger than life presence, it also isn’t Long Shot or Booksmart or Stuber.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is catnip to Tarantino nerds like me. It has the usual surfeit of references to obscure films and television shows. Some of these are deftly interwoven into the story itself. It boasts a carefully curated soundtrack that unearths “some-hits” wonders. It also contains scenes depicting nasty yet comical violence, a hallmark of Tarantino’s work ever since Reservoir Dogs.

At first blush, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would seem to be Tarantino’s most linear film. Yet it still displays certain continuities with his oeuvre in terms of story structure and technique. Although the film eschews the chapters and title cards found in Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill, it still contains elements of what David calls “block construction.” In the case of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, it is all about threes. The plot is structured around three days in the winter and summer of 1969: February 8th, February 9th, and August 9th. Each “chapter” is introduced showing the date via superimposed text. And all three chunks of narrative crosscut among the activities of three actors – Sharon Tate, Rick Dalton, and Cliff Booth – as they try to adapt to changes in the film and television industries.

If all of this assures that you’d never mistake Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as the work of another director, other elements show Tarantino striking out in new directions. Chief among these is his mash-up of two normally distinct story types: the show-biz tale and the true crime yarn. Think of it as Singin’ in the Rain meets In Cold Blood. In what follows I outline some of the ways that Tarantino adapts his signature style to two well-established storytelling options: the multiple draft narrative and the network narrative. I also consider the effects Tarantino’s counterfactual history has on the conventions of the show-biz tale and the celebrity biopic.

My analysis contains major spoilers. If you haven’t seen Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, stop reading now!

My world and welcome to it

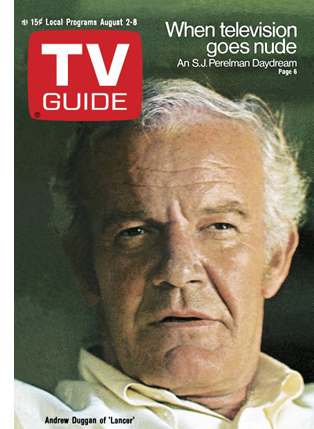

Quick trivia question: what actor was on the cover of TV Guide during the week that Sharon Tate was murdered by the Manson family? Sharp viewers of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood should know the answer. We see Tate’s housemate, Woychiech Frykowski, reading that issue of the magazine as he watches Teenage Monster on late night television.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Tarantino’s film treats this little bit of pop culture ephemera as an uncanny coincidence. It simply becomes yet another way that he can intertwine the destinies of his three protagonists. But that brief shot got me thinking: did Tarantino start with the idea that he’d recreate whatever series was featured on TV Guide the week Tate was killed?

If so, Rick might have appeared just as easily as an aspiring cartoonist next to William Windom on the NBC sitcom, My World and Welcome to It. The show debuted just six weeks after Tate’s death. It is not unthinkable that NBC would have pushed for a cover on TV Guide in an effort to promote the premiere. Yet Tarantino’s counterfactual history in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would have been vastly different if that had been the case.

Did Tarantino really base his screenplay on this conceit? I doubt it. Lancer fits so snugly into the world that the director captures onscreen that it is not be so easily replaced. Tarantino seems to have a nostalgic fondness for the show, much as I did in my wasted youth. (I recall having a Lancer lunchbox at age six.) Production designer Barbara Ling describes the steps she took to recreate Lancer’s mix of Spanish/Western design. This involved adding adobe storefronts to the wooden ones, and substituting iron coils for wooden pegs on the saloon’s staircase. Ling added, “This was a [rich] cattle town and the buildings are two and three stories. It’s not Deadwood.”

Many critics have characterized Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as another hangout movie. This is Tarantino’s designation for a film that is leisurely paced, fairly light on plot, and mostly gives the audience a chance to spend time with the characters. Indeed, because of these qualities, reviewers often compare Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood to Jackie Brown, a film that Tarantino himself compared to Rio Bravo, which was Howard Hawks’ hangout movie.

The resemblances don’t stop there. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s three-headed protagonist bears certain similarities to Jackie Brown’s Jackie, Ordell, and Max.

Yet while watching Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I felt this film, more than any of Tarantino’s others, was an exercise in world-building. Normally we associate that term with sci-fi, fantasy, and comic book movies. It is especially important for transmedia properties where the fictional universe depicted exceeds the bounds of any individual film, television series, book, or video game.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is also an alternate history, a type of speculative fiction also common in sci-fi and comic book stories. The Avengers: End Game and Spider-man: Into the Spiderverse are both relatively recent examples. This suggests a loose affiliation between Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood and other blockbusters even as Tarantino tweaks that formula by situating his speculative fiction within the generic framework of true crime.

Tarantino largely avoids the industrial motivations behind these two narrative techniques commonly seen in tentpoles. Instead, he simply recreates the pop culture world of his youth. In doing so, the director’s real world, his “realer than real” universe, and his “movie movie” universe all collide.

Keepin’ it real (and realer)

As Tarantino has explained in interviews, the “realer than real” universe is an alternate reality close to our own where his fictional characters can intermingle with real people. The “movie movie” universe, on the other hand, is a more overtly fantastic world closer in spirit to comic books or exploitation films. The characters have unusual abilities or even supernatural powers. The “movie movie” thus downplays the realistic motivations usually found in the “realer than real.” In Tarantino’s oeuvre, Reservoir Dogs and True Romance exemplify the “realer than real.” Kill Bill and From Dusk to Dawn are instances of the “movie movie.”

Each universe features a web of connections that can link particular tales together. For example, Kill Bill’s Sheriff Earl McGraw and his son Edgar pop up in Death Proof. Similarly, Lee Donowitz, the cocaine-sniffing movie producer in True Romance, is purportedly the son of Sgt. Donny Donowitz, the “bear Jew” in Inglourious Basterds.

In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, the most obvious references to these two Tarantino universes are the fictional brands he has created. During the end credits, we see Rick in a TV ad for Red Apple cigarettes. According to a Tarantino wiki, “ads or packs of these flavorful smokes” can be seen in The Hateful Eight, Inglourious Basterds, Planet Terror, Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction, From Dusk till Dawn, Four Rooms and Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion. (The latter is an obvious outlier. Yet the Red Apple nod was likely an in-joke related to Tarantino’s offscreen romance with Mira Sorvino, who played Romy.)

Similarly, Tarantino’s fictional fast food chain, Big Kahuna Burger, appears on a bus billboard in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. It previously was featured in a memorable scene in Pulp Fiction. (“That’s a tasty burger!”) But it had already debuted as a delicious snack devoured by Mr. Blonde in Reservoir Dogs. Big Kahuna later comes back in two other Tarantino films, From Dusk Till Dawn and Four Rooms, as well as Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion.

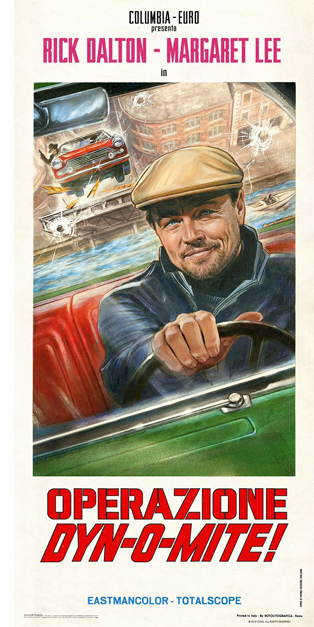

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Much of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes from the way Tarantino overlays these three universes to create a singular fictional world. For example, at one point we learn that Rick was considered for the role of Captain Virgil Hilts, the part played by Steve McQueen in John Sturges’ The Great Escape. Tarantino even inserts digitally altered footage of The Great Escape to show us a scene of Rick as Hilts. Since Rick claims he never met Sturges, this moment appears to represent an imagined version of the film that could exist in some type of alternate history. It invites us to consider how different Rick’s career might have been had fortune smiled upon him instead of McQueen.

To disentangle this knot, one must surmise that The Great Escape and Steve McQueen belong to both the real world and the “realer than real” world. Yet the scene of McQueen at the Playboy mansion and Rick describing his missed opportunity can only belong to the “realer than real.” And the character of Hilts himself exists only in the “movie movie” world. Hilts shares this status along with other characters Rick plays onscreen, such as Bounty Law’s Jake Cahill and The FBI’s Michael Murtaugh. After all, movie magic enables Cliff Booth to stand-in for Rick for scenes involving physical action. That two actors can play the same character within the same scene suggests that fictional personae in cinema have a unique ontological status quite different from the real world.

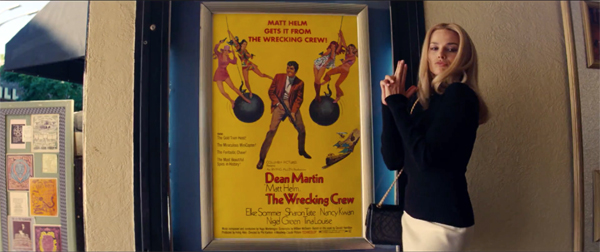

Arguably, the scene where Sharon Tate watches herself in The Wrecking Crew raises even more vexing issues about what is real and what is fictional. Unlike the clip from The Great Escape, the theatre screening shows the real Sharon Tate playing the character Freya in The Wrecking Crew. The fictional Sharon Tate watches the real Sharon Tate, along with the rest of the Bruin Theater’s audience. Yet, because Margot Robbie only pretends to be Sharon Tate for Tarantino’s camera, she doesn’t really watch herself playing the role. Obviously, Robbie belongs only to the real world. Yet Sharon Tate, as both an actual person and a fictional character, inhabits both the real world and the “realer than real world.”

Here the film indulges the Bazinian conceit that cinema has indexical properties. While making The Wrecking Crew, the film camera captured an imprint of the real Sharon Tate that preserved her being beyond the reaches of time and even death. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, this moment is both joyful and sad. The viewer imagines the thrill that Tate feels in watching herself on the big screen, basking in the glow of incipient stardom. Yet the delight we experience is colored by our knowledge of what happened to the Sharon Tate seen falling on Dean Martin’s camera case. Unlike Robbie’s character, that Tate is doomed to a grisly death at the hands of psychopaths.

By film’s end, however, we are forced to reevaluate where Sharon Tate fits into Tarantino’s universe. When Cliff and Rick thwart the attack of Tex Watson, Susan “Sadie” Atkins, and Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkel, both Sharon Tates appear to move solely to the realm of the “realer than real.” Like the fictional Sharon Tate played by Robbie, the actress who appeared in The Wrecking Crew also lives on in a parallel universe created by the forking of time. And the fate of that character remains completely undetermined. Now fully a part of the “realer than real,” Tarantino’s Sharon Tate might eventually snort cocaine with movie producer Lee Donowitz or bum a Red Apple cigarette from Pulp Fiction’s Mia Wallace.

Once she joins the “realer than real,” almost any fate you could imagine for Sharon Tate seems possible. And it is that sense of the actress’ unlimited horizons that gives the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its resonance. Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time films always situated viewers in the realm of myth. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, on the other hand, evokes the fairy tale.

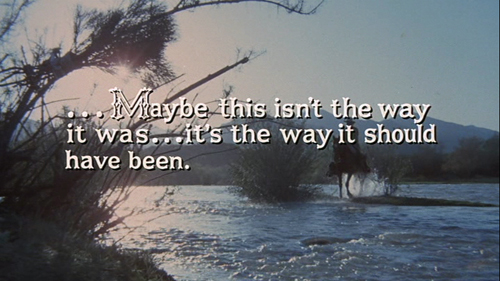

Tarantino is known for his experimentation with narrative, and the simplicity of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s “what-if” scenario could seem like a retreat from the formal play seen in his earlier films. Yet I’d argue that Tarantino’s merging of fact and fiction is even more audacious in certain respects. It strikes me as an unconventional example of what David calls “multiple draft narratives,” like Krzystof Kieslowski’s Blind Chance or Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gives us a second draft of history, albeit one where the key decision point is saved almost until the end of the film. And unlike Blind Chance or Sliding Doors, Tarantino doesn’t need to tell us what the different outcomes are for each of these tales. The first draft of history is one we already know.

In fact, the notion of multiple drafts offers a useful lens for all three films in Tarantino’s “counterfactual” trilogy. (The other two are Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained.) In Groundhog Day, Source Code, and Edge of Tomorrow, each iteration of the basic situation shows the protagonist inching toward his goals. They gradually progress to the point where they are able to alter destiny, either theirs or the world’s or both.

Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood all present images of history not as it was, but as it should have been. Such counterfactual histories run counter to the norms of speculative fictions that often present us with dystopian worlds we were lucky to avoid. (Think Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, Robert Harris’ Fatherland, or Kevin Willmott’s “mockumentary” C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America.) All of these stories depend upon our knowledge of the first draft of history. Yet Tarantino gives us second drafts that right particular historical wrongs in either small or large measure. In doing so, Tarantino gives us versions of history that are closer in spirit to his favorite movies. All three films in the “counterfactual” trilogy feature tidy resolutions. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, however, is even more self-conscious about the way Tarantino’s second draft of history takes the form of a “movie movie” climax. The realer-than-real version is the one we ought to prefer.

Paging Mr. Melcher, Mr. Terry Melcher…

If Tarantino’s conflation of fact and fiction evokes certain traits of the multiple-draft narrative, his vivid recreation of Hollywood circa 1969 illustrates another type of story popularized in American independent films and various art cinemas: the network narrative.

Tarantino has broached this form before in Inglourious Basterds. There he moves back and forth between three mostly independent storylines: 1) the Basterds’ guerrilla campaign against German soldiers, 2) Archie Hicox and Bridget von Hammersmarck’s initiation of Operation Kino, and 3) Shosanna’s plan to avenge her family’s deaths during the premiere of Nation’s Pride. SS officer Colonel Hans Landa threads through all three storylines. He orders the killing of Shosanna’s family in the opening scene. Later he shares apple streudel with Shosanna in a Paris café. Landa also investigates the scene where Hicox has been killed. In the climax, he interrogates Bridget in a scene that contains a grim allusion to Cinderella’s lost slipper.

Finally, Landa negotiates a deal with Aldo Raine’s superiors that guarantees his immunity from prosecution for war crimes.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is obviously much less plot-driven than Inglourious Basterds. Yet, as noted above, it shares a similarity in the way it interweaves the stories of three characters: Rick, Cliff, and Sharon.

It’s frequently said that Hollywood is a company town. By situating all three characters within the film and television industries, Tarantino tacitly stays faithful to that truism. The protagonists’ shared profession also facilitates the kinds of attenuated links between stories commonly found in network narratives.

Part of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes in recognizing the “six degrees of separation” that join all of these people, both real and fictional, in the same entertainment ecosphere. Take, for instance, one decidedly minor character: actress and singer Connie Stevens, played by Dreama Walker. At the Playboy Mansion party, Stevens listens to Steve McQueen explain the romantic triangle that has Sharon living with her current husband, Roman Polanski, and her ex-boyfriend, Jay Sebring. Stevens, though, is the ex-wife of actor James Stacy, who played Johnny Madrid in Lancer. Stacy (played in our film by Timothy Olyphant) is Rick Dalton’s scene partner for the episode of Lancer that Dalton hopes can spur his comeback. Dalton is Sharon Tate’s neighbor on Cielo Drive, the same house that Charles Manson targets as the site of the “family’s” first murder. This circuit even loops back on itself. When Stacy and Dalton first meet on set, Stacy asks Rick whether it was true that he almost got a part in The Great Escape, the same part played by McQueen.

Two characters in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood serve as nodes that connect all three storylines together. The first is Cliff, Rick’s stunt man and gofer. Although not a resident at Cielo Drive, he spends a lot of time in Rick’s home and thus is privy to what happens in Sharon’s abode. This is especially evident when Cliff repairs Rick’s fallen TV antenna. The camera is aligned with him as he overhears Sharon playing a Paul Revere and the Raiders album. He also notices Charles Manson approaching the Polanski residence. Tarantino’s casting of Damon Herriman as Manson is likely an allusion to the television show, Justified. Herriman played Dewey Crowe alongside Olyphant.

Justified was also an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s “Raylan Givens” books. Tarantino has long admired Leonard’s work as a writer of both westerns and crime novels.

Employing a redundancy that befits Hollywood storytelling, Cliff gets linked to Sharon’s storyline in other ways. While working as Rick’s stunt man for an episode of The Green Hornet, he gets involved in a dust-up with Bruce Lee. Lee gave Sharon Tate some pointers on fighting as she prepared for her role in The Wrecking Crew. And in real life, the martial arts legend was recommended for the role of Kato on television’s The Green Hornet by Sebring, Tate’s former boyfriend.

Perhaps Cliff’s most important role in the film’s network involves his dalliance with Pussycat, one of the many young women who viewed Manson as a kind of guru. Cliff picks up Pussycat as a hitchhiker and gives her a ride back to the Spahn ranch. Having worked on the ranch back when it was an active production site, Cliff grows concerned for the safety of its owner, George Spahn. Cliff notices how the Manson clan has taken over and is troubled by its weird vibe. Determined to see George for himself, Cliff forces his way into George’s house over the objections of the Manson girls, especially Squeaky. George seems careworn, but Cliff finds that there is little he can do for him.

When Cliff sees a pocketknife sticking out of his front tire, he confronts Clem, one of Manson’s followers. The conflict becomes physical. Cliff breaks Clem’s nose with one punch and then proceeds to beat him to a bloody pulp.

This proves to be a dangling cause that gets resolved in the film’s climax when Cliff recognizes Tex, Sadie, and Katie as people he met at the Spahn ranch.

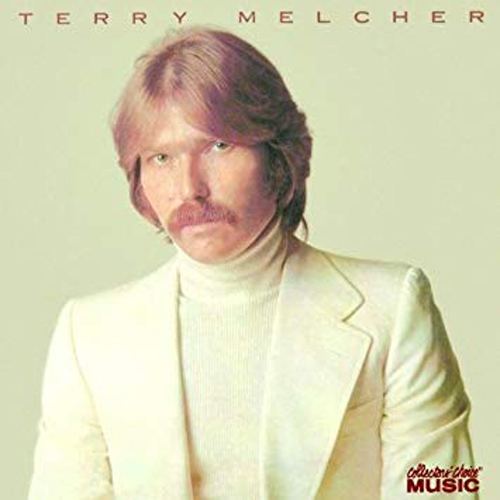

The other character who links the storylines together is one we never see: record producer Terry Melcher. Melcher is the “Terry” that Manson mentions when he visits Cielo Drive in the scene described above. Later, Tex reminds Sadie, Katie, and Linda that Charlie directed them to go to the place where Terry Melcher lived and kill everyone inside.

Although these are the only explicit references to Melcher, he is indirectly represented in several other aspects of the film. Here it helps to know a little about Melcher’s career and Manson lore. Even if Melcher’s name draws a blank, you likely know many of the bands he worked with: the Byrds, the Mamas and the Papas, and Paul Revere and the Raiders.

All these musicians crop up in one way or another in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. Melcher’s last major credit of the 1960s was as producer of the Byrds’ Ballad of Easy Rider. When Rick berates Tex for parking his car on Cielo Drive, he yells, “Hey, Dennis Hopper! Move this fucking piece of shit!” Rick’s insult fits with his general disdain for hippies. But it also alludes to Easy Rider by comparing Tex’s look to that of Hopper’s character, Billy.

Two of the Mamas and the Papas – Michelle Phillips and Cass Elliot – both appear in the party scene at the Playboy mansion.

We also hear the Mama and the Papas’ big hit, “California Dreaming” in a cover version by Puerto Rican singer José Feliciano. And when the car driven by Tex crawls up Cielo Drive, the music issuing from the Polanski residence is the Mamas and the Papas’ “12:30: Young Girls are Coming to the Canyon.” Even before Tex’s directive to the Manson girls, Tarantino has given us a subtle reminder that Melcher was Charlie’s intended, if indirect, target.

Finally, Sharon plays Paul Revere and the Raiders’ “Good Thing” and “Hungry” on a hi-fi in her bedroom.

The choice of music is especially fitting since the band’s lead singer, Mark Lindsay, lived in the same house on Cielo Drive with Melcher and his then girlfriend, Candice Bergen.

Beyond these musical references, Melcher’s history with Manson informs Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in another way. Melcher recorded some demos of Manson’s songs, and even discussed making a documentary about Manson’s commune at the Spahn Ranch. In testimony at trial, Melcher said that any possibility of a record contract with Manson was sundered when Charlie asserted that he’d never join a musicians’ union. Manson’s staunch refusal was rooted in his desire to avoid entanglements with the establishment. Yet union membership was a condition for any contract with Melcher’s label, Columbia records. Another factor in Melcher’s decision was his assessment of Manson’s talent. Charlie couldn’t sing.

Although Melcher publicly stated that he only considered Manson’s musicianship, he privately expressed concerns about Charlie’s mental stability. These were heightened when he visited the Spahn Ranch and witnessed Manson in a physical altercation with a drunken stunt man. Tarantino more or less recreates this episode in his film, substituting Cliff for the unnamed stunt man and the hapless Clem for Charles Manson.

More importantly, Melcher is the son of screen legend Doris Day and stepson of agent/manager/producer Martin Melcher. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, he becomes the ideal, if absent, symbol of the combined worlds of music, television, and film that Tarantino so lovingly details.

How the West was lost

Los Angeles circa 1969 is presented as the epicenter of the American entertainment industries. It’s a place where a hairdresser like Jay Sebring rubs shoulders with action stars, TV cowboys, ingénues, film directors, and pop stars –and make $1000 a day to boot! The constant stream of hits from KHJ radio is as ubiquitous as the many movie posters, billboards, and theater marquees that feature Hollywood’s latest and greatest.

Tarantino’s press kit for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood makes reference to Joan Didion’s famous observation in “The White Album” that “the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community.” Most critics take Didion’s reference to the Sixties as shorthand for the end of the “peace and love generation.” Yet Tarantino’s slightly revisionist take suggests it’s not only the youthquake that died, but also a certain strain of Hollywood filmmaking that passed with it.

Although I don’t doubt their historical accuracy, the litany of titles that appear throughout Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels as curated as any of Tarantino’s music soundtracks. Some, like 2001: A Space Odyssey, are films that entered the canon of great sixties cinema. Others, like The Night They Raided Minsky’s, are early films by directors who’d later achieve greatness. (In this case, William Friedkin, who won an Oscar in 1972 for The French Connection.)

But many, like Lady in Cement, Tora, Tora, Tora!, Krakatoa: East of Java, Mackenna’s Gold, C.C.& Company, and even The Wrecking Crew, are largely forgettable movies.

Tarantino clearly has affection for all of the drive-in theaters and Hollywood picture palaces where these titles played. But the titles themselves are evidence of the industry’s struggle to adapt to new tastes and a rapidly changing media landscape. Old-school show biz types, like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra, continued their success as singers and television personalities. But their careers as actors had functionally ended by 1969. And the efforts to keep them relevant often seemed either strikingly anachronistic or just plain weird.

In the opening scene of Lady in Cement, Frank Sinatra fights off a small school of sharks while he is examining the body of a nude woman who, like Luca Brazzi, sleeps with the fishes. And yes, the scene is as ludicrous as it sounds. If this is what became of Hollywood’s once great tradition, it is hard not to think we should just let it pass.

Yet, the fear of obsolescence also explains the oversize role that Tarantino gives to the Western as part of this changing landscape. True Grit and The Wild Bunch were among the summer of 1969’s biggest hits. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would eventually become the year’s top-grossing film. All three Westerns feature cowboy heroes that are either aging, outmoded, or both. They reminded contemporary viewers that horse riders would soon yield to horseless carriages, the lone bounty hunter would soon be supplanted by paramilitary detective agencies, and the humble six-shooter can’t match the lethal power of a Mexican army machine gun.

In retrospect, though, the popularity of the Western in 1969 represents the genre’s last gasp. Studios continued to make Westerns during the 1970s, but only three – Jeremiah Johnson, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and The Electric Horseman – would surpass $10 million in rentals in the entire decade.

On television, such long-running series as Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Virginian had their last round-ups. The networks tried their hands at new Westerns, like Alias Smith and Jones (below), Hec Ramsey, Dirty Sally, and Lancer, but they were all short-lived. At the start of the 1980s, the genre was completely moribund. Subsequent efforts to recapture the Western’s former glory were mostly the equivalent of flogging a dead pony.

As a total cinephile, Tarantino is entirely aware of this aspect of the genre’s history. This is signaled quite explicitly in the decrepit condition of the Spahn Movie Ranch. Yet Tarantino also uses Rick’s career arc to signify its downward trajectory.

No character in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is as strongly associated with the Western as Rick. His home is filled with collectibles like his Hopalong Cassidy coffee mugs. His walls are decorated with posters for The Golden Stallion and A Time for Killing. On set, he reads pulp oaters like Ride a Wild Bronc to relax between takes.

By using Rick to dramatize the twin declines of both Old Hollywood and its “bread and butter” genre, the narrative arc of Tarantino’s drugstore cowboy is one suffused with nostalgic melancholy. The key moment in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood occurs when Rick breaks down telling the story of Easy Breezy to Trudi Fraser, his Lancer co-star. He describes Easy “coming to terms with what it’s like to feel slightly more useless each day.”

The various threads of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s network finally knot together in the Manson family’s attack on Cielo Drive. At the moment of truth, it is telling that Rick reaches not for a firearm, but for the prop flamethrower he wielded in The 14 Fists of McCluskey. By recalling the moment when Rick shouts, “Anyone here order fried sauerkraut?”, Tarantino reminds us that violent spectacle and snappy quips will eventually replace the Western’s ritualistic showdowns.

Still, it is a musical allusion to the Western that gives Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its final grace note. Cliff and Rick have thwarted the Manson family’s attack. The ambulance takes Cliff to the hospital. Rick offers an explanation of what just happened to his neighbors. Jay recognizes Rick as television’s Jake Cahill. Via the intercom, Sharon invites him to come up for a drink. As Rick walks to the house, we hear the start of Maurice Jarre’s “Lily Langtry” [sic] from his score for The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean.

John Huston’s film begins with an expository title shown below that highlights the western’s tendency toward self-mythology. It is especially apt for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s counterfactual history.

Jarre’s cue, though, appears in a scene where the renowned actress Lillie Langtry finally visits Judge Bean’s Texas town. Langtry is given a tour of the Bean’s house, now converted into a museum that also acts as a shrine to her. Bean worshipped Langtry, but tragically dies before he gets to meet her. Tarantino inverts both Huston’s sad ending and its dramatization of missed opportunity. By altering the course of history, the cowboy in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gets to be the real-life hero rather than the TV heavy. Rick also gets to meet the actress he’s admired from afar. Rick and Sharon are still both married to other people. But their chance meeting in the film’s epilogue feels more than anything like a dream fulfilled.

A star is unborn

In the previous section, I dwelt on the role of the Western in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood because of its symbolic significance in capturing a particular historical moment. But Tarantino borrows quite freely from another narrative prototype: the show-biz tale. In fact, while walking out of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I wondered aloud if it was Tarantino’s twisted take on A Star is Born.

Like A Star is Born, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood centers on a male performer whose career has started to decline and a female newcomer whose star is on the rise. Moreover, Rick’s drinking problems create an obstacle to his comeback in much the same way that alcohol contributes to the downfall of the male protagonists in all four versions of A Star is Born.

Tarantino, though, subtly alters this template in two ways. First, he depicts his two stars as neighbors rather than as a romantic couple. Secondly, he cleverly depicts Rick’s career arc as an inverse mirror of Sharon’s.

Tate was an Army brat who grew up in Europe. Her earliest work was as an extra in Italian films. She moved to Hollywood in 1962 and got her break playing Jethro Bodine’s girlfriend on The Beverly Hillbillies. In the mid-sixties, Tate made the move to films, appearing in Eye of the Devil and The Fearless Vampire Killers.

It was during production of the latter that Tate met her future husband, Roman Polanski. Tate’s role in Valley of the Dolls further enhanced her status as an “up and comer.” In 1968, Tate earned a Golden Globe nomination in the category of “Most Promising Newcomer — Female.”

In direct contrast, Rick’s career begins in Hollywood and ends in Italy. Rick enjoys early success with Bounty Law and The 14 Fists of McCluskey. But soon finds himself reduced to guest star roles on television. Against his better judgment, Rick agrees to star in four Italian quickies. Two of these are spaghetti westerns directed by Sergio Corbucci, a Tarantino fave who created the popular “Django” character. Rick returns to Hollywood but his future is uncertain. He could be the next Clint Eastwood, star of A Fistful of Dollars and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Or he could be the next Richard Harrison, star of $100,000 Dollars for Ringo and Secret Agent Fireball.

If this were all there was to the comparison, it would hardly be worth mentioning. But Tarantino hints at other parallels through a much more obscure and convoluted cinematic reference. An auteur as shrewd as Tarantino would undoubtedly remember that the Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time” –used in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood under shots of Rick’s return from Rome – was previously featured in the opening sequence of Hal Ashby’s Coming Home.

The connection to Ashby’s film is strengthened by the casting of Bruce Dern as George Spahn, a role originally intended for Burt Reynolds. Early in his career Dern played Jane Fonda’s uptight, martinet husband in Coming Home. More importantly, during Coming Home’s climax, Dern’s character commits suicide by wading into the ocean to drown himself, just as James Mason does at the conclusion of George Cukor’s version of A Star is Born.

Which brings us back to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s controversial ending. Earlier I discussed the resemblance between its counterfactual history and multiple draft narratives. Here I want to discuss it as an illustration of the caprice of fame.

Much more than the endings of Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained, the climax of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels both resolved and unresolved. Hitler’s violent death in Inglourious Basterds surprised audiences who first saw it in theaters. Yet the historical record indicates that the Basterds simply saved Hitler the trouble of later killing himself and his wife, Eva Braun. At the conclusion of Django Unchained, the protagonist’s revolt clearly hasn’t ended slavery as a “peculiar institution.” But its story of personal revenge remains deeply satisfying.

The ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood left me with more questions than answers. I get it. Sharon Tate lives instead dying at the hands of the Manson family. Tarantino gives us the Hollywood happy ending that this story lacked in reality. But what’s next?

Do the deaths of Tex, Sadie, and Katie mean that Leno and Rosemary LaBianca also survive? Maybe. Perhaps the loss of three members of the cult might cause the others to reevaluate their loyalty to Manson. Perhaps Manson himself would reevaluate his plan to trigger a race war.

But maybe not. If Manson were the hero of Tarantino’s grindhouse climax rather than its villain, one could easily imagine the film running another twenty minutes with Manson vowing to get even. You might imagine it as something like the surprising “second climax” of Django Unchained. After mourning the loss of his compatriots, Charlie would proclaim. “The fires of Hell will descend upon the Hollywood hills. This time it’s personal.”

Perhaps the bigger question is whether Sharon continues to be the “It” girl during the next phase of her career. The allusions to A Star is Born suggest a steady upward trajectory. But the reality is that success depends upon a certain amount of luck. It is never assured. A few box office bombs and Sharon Tate might be reduced to the same sort of TV guest spots that Rick is doing.

In this way, the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood asks us to consider a potential paradox. Did Sharon Tate become more famous in death than she ever would have been in life?

The theme of talent tragically cut down in the prime of life is a hoary cliché of the celebrity biopic. Tarantino is smart to steer clear of it. Yet whenever we watch a film like Prefontaine, Beyond the Sea, or Lenny, one starts to wonder, “Would anyone bother to make this film if its subject had lived?”

To be sure, the totality of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood shuns any pat answer. Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas died at age 32. Initial reports said she choked on a ham sandwich in the midst of having a heart attack. I remember the media reports when Mama Cass passed in 1974. But does anyone who didn’t live through that moment?

James Stacy, star of Lancer, nearly died in a deadly motorcycle accident. (Tarantino hints at this fate by showing Stacy, sans helmet, riding his steel horse away from his trailer.) Stacy survived, but lost an arm and a leg as a result of his near fatal injuries. He eventually made a comeback in 1977 and even earned an Emmy nomination for his work on Cagney and Lacey.

Yet, if you mention James Stacy during dinner conversation tonight, I suspect your companion will ask, “Who?”

And then there is the scene where Pussycat and the other Manson girls walk past a large mural of James Dean in his iconic pose from Giant. Dean was certainly famous during his lifetime. But he became a legend at age 24 after his Porsche Spyder collided with another car, snapping his neck.

Would Sharon Tate have achieved stardom had she lived? God only knows. I certainly don’t. I do know one thing, though. Being a victim of the “crime of the century” preserved Tate’s image in popular memory with a vividness that very few human beings on this earth ever achieve.

Margot Robbie’s performance as Tate is extraordinary. She reminds modern viewers of the verve, spirit, and sensuality that Sharon brought to the screen. Yet it is the image of Tate as a tragically murdered heroine that Tarantino, like Mark Macpherson in Laura, appears to have fallen in love with. And it is this image that continues to haunt me some fifty years after Tate’s death.

Thank you to David and Kristin for their comments onf an earlier draft of this post. Thanks also to JJ Bersch and Maureen Rogers for letting me bounce some of ideas off them.

Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders remains the most comprehensive account of the Tate-LaBianca murders. Tom O’Neill, though, has spent the last 20 years investigating Manson’s crimes. His new book, Chaos: Charles Manson, the C.I.A., and the Secret History of the Sixties, claims that Bugliosi’s investigation was deeply flawed. Instead, his research suggests that Manson was a drug trafficker and C.I.A. operative. For O’Neill, the notion that Bugiliosi saved Los Angeles from a hippie death cult is wrong. The motive for the crimes was both simpler and more quotidian. All of Manson’s murders were the result of drug deals gone wrong. An interview with O’Neill can be found here.

The story that Terry Melcher witnessed a fight at the Span Movie Ranch between Charles Manson and a drunken stunt man sounds apocryphal. Yet it appeared in The Telegraph’s obituary for Melcher, which was first published in 2004. I haven’t been able to independently corroborate that story with another source. However, even if it isn’t true, it is part of Manson lore. I saw the same story repeated on at least three other websites. Doris Day’s death in May spawned the publication of a handful of articles about her relationship with Terry. They can be found here, here, and here. An brief overview of Melcher’s career as a record producer can be found in Rolling Stone’s obituary.

For those interested in learning more about Sharon Tate’s life, I recommend Sharon Tate: Recollection. It was written by Tate’s mother Debra. It also features a foreword by her husband, Roman Polanski.

Mark Harris’s Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood and Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls survey the momentous changes taking place in the film industry during the late 1960s.

Bruce Fretts provides a fairly thorough overview of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s voluminous pop culture references.

Several articles have also appeared that address different aspects of the film’s production. An interview with choreographer can be found here. Cinematographer Robert Richardson and production designer Barbara Ling detail their efforts to recreate the sets of the TV show Lancer here. Richardson also discussed Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s visual influences in a Hollywood Reporter podcast.

An interview with Mary Ramos, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s music coordinator, can be found here. Guides to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s music soundtrack can be found here, here, and here.

An analysis of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office implications is found here.