Archive for October 2011

Play it again, Joan

“The happy heart loves the cliché.”

–Myra Hudson (Joan Crawford) in Sudden Fear.

Sometimes your audience gets what you’re saying faster than you do. Years ago, after I gave a lecture in a class at Columbia University, a grad student came up and said: “What you’re doing is looking for the conventional side of unconventional films and the unconventional side of conventional films.” I’d say it’s not all I try to do, but the student’s chiasmus does capture a lot of what interests me.

It’s especially on target for Hollywood cinema. I don’t understand criticisms of Hollywood for not being realistic. It’s a highly stylized, artificial cinema, only a few notches above ballet or commedia dell’arte. Some of our best critics, like Parker Tyler and Manny Farber and Geoffrey O’Brien, have understood this. All the artifice will demand plenty of conventions, yes, but there are always filmmakers ready to treat them in fresh ways. And the churn is swift. American studio cinema is constantly finding new variations on its traditional forms, formats, and formulas.

Do-overs are allowed

Sleep, My Love

Take replays. The repeated sequence has become so common in our movies that nobody much notices it any more. We’re quite used to seeing an earlier action revisited. Often the replay simply serves to remind you of what happened, as when clues to a mystery are given in fragmentary flashbacks. The replay may also aim to get you absorbed in a character’s mental life. John, the hitman in John Woo’s The Killer, is traumatized by the fact that he blinded an innocent woman during a contract hit, and the moment of her wounding haunts him.

Sometimes, however, we get multiple-draft replays, in which the second version significantly alters the first. A common gambit is to have the second version show more of what happened, as in the money drop in Jackie Brown. Other cases show contradictions, as when conflicting testimony is dramatized in flashbacks. The most recent version I’ve seen occurs in The Debt, when the central 1966 section of the film concludes by showing what really happened when Dr. Vogel slashed Rachel and fled. In such cases the replay becomes less a true repetition and more of a revision, a new version questioning or canceling what we’ve seen before.

The idea isn’t new. You can find the replay in various forms in trial films of the 1930s, as I’ve discussed here. But the replay really came into its own during the 1940s. Directors and screenwriters experimented with the device as part of a broader initiative, burrowing into new niches in the ecosystem of classical narrative.

In those films, it’s common for replayed scenes to show an incident haunting the protagonist, as when the tormented bride of The Locket is assailed by memories as she walks down the aisle. Sometimes a flashback fills in information that was cunningly omitted from the earlier version, as in Mildred Pierce. And we also have competing accounts of what happened, as variant replays furnish multiple drafts. The most famous example is probably Crossfire.

By 1950, Joseph Mankiewicz could dream up one of the most daring experiments of the period, one that anticipated the repeated scene in Persona. For All about Eve, Mankiewicz planned to present Eve’s memorable monologue about the power of theatre twice: first through the sympathetic eyes of Karen (Celeste Holm), then from the perspective of the bitter Margo Channing (Bette Davis). What would viewers and other filmmakers have made of it? But Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck ordered the replay dropped, for reasons I speculate about in this entry’s codicil.

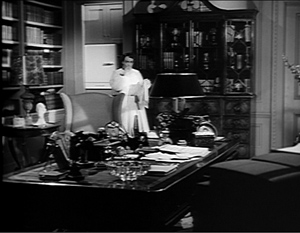

Mankiewicz’s unseen experiment with Eve’s “Audience Aria” reminds us that replays affect the soundtrack too. The most common use of replays is probably auditory, that line of dialogue that flits through a character’s consciousness—an auditory flashback, in effect. “Who knows what you may do the next time?” asks the sinister voice of the psychiatrist as Alison (Claudette Colbert) totters up the stairs in Sleep, My Love (1949). Several snatches of dialogue can flow together to recall a host of earlier scenes. In The Hard Way (1943), on another staircase, Katie (Joan Leslie) becomes distraught as bits of dialogue spoken by several characters flash through her mind.

More unusual is the audio replay in Duvivier’s wonderfully stylized Lydia (1941). A flashback to a ball is introduced by Lydia’s voice-over, recalling the splendid ballroom with its mirrorlike floors and the “divine aggregation of musicians, hundred of them, I think.”

But then her old lover corrects her memory and we get a flashback showing a more modest ballroom with a small ensemble.

Over these later shots, however, we hear bits of Lydia’s earlier description of the big ballroom and troops of musicians, in contrast to what we see. The sound flashback functions as a wry narrational commentary on Lydia’s stubborn romanticism.

Purely auditory replays tend to be subjective, but could we have an objective one? And can it promote surprise and suspense? As we say in Wisconsin, you bet. (Not you betcha.)

The replay machine

A lighthearted instance appears in The Pajama Game (1957). Sid Sorokin (John Raitt) , the new superintendant at the Sleeptite Pajama Factory, is falling in love with Babe Williams (Doris Day), the no-nonsense head of the labor union’s Grievance Committee. He sings into his Dictaphone about her in the song, “Hey, There (You with the Stars in Your Eyes).”

At the end of the song’s first section, he plays it back and then comments sourly on the lines he’s just sung. By the end, he’s joining himself in a duet, harmonizing nicely.

This instant playback wasn’t a cinematic invention, though. The same number, including the Dictaphone gimmick, was employed in the original Broadway production.

The Dictaphone, which used both wax cylinders and plastic belts for recording, was a popular device for businesses. Erle Stanley Gardner employed it for dictating many of his novels. A competitor to the Dictaphone was the SoundScriber, a late 1940s device using vinyl phonographic discs. The SoundScriber figures in a more sustained and suspenseful replay scene a few years before The Pajama Game.

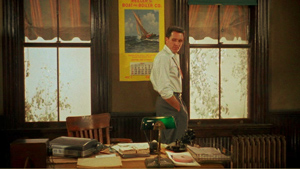

In Sudden Fear (1952), Myra Hudson (Joan Crawford) is a prosperous playwright who has outfitted her office with a SoundScriber. She uses it for dictating plays and correspondence. One evening before a party, euphoric after her new marriage to the handsome actor Lester Blaine, she meets with her attorney to prepare a new will. He proffers a draft that assigns a modest sum to Lester, but she considers it insulting. She switches on the SoundScriber and dictates a new will, one leaving all her estate to Lester.

But we’ve had our suspicions about Lester, since he’s played by Jack Palance, an actor with more juts to his facial planes than a Giacometti bust. Our fears are confirmed after Lester hooks up with his old girlfriend Irene (Gloria Grahame). When they learn that Myra is making a new will, they believe she’s going to give the bulk of her estate to a foundation.

On the evening of the party, as she starts dictating her new will, the guests arrive and she descends to meet them. Irene and Lester slip away and meet in Myra’s study. Fade out on Lester closing the door.

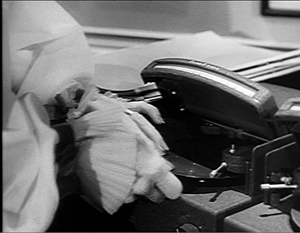

Next morning, Myra return to her study and discovers she left her SoundScriber on all night. She hits replay and listens to herself bequeathing all her money to Lester. This is the replay that launches the big action. As she’s about to switch off the machine, she hears the conversation starting between Lester and Irene. The microphone, left on accidentally, has picked up their plotting.

The couple is still under the false impression that the new will leaves Lester penniless. We hear him declare his contempt for Myra while caressing and embracing Irene. They start planning to kill her before she can sign the new will.

The SoundScriber scene gives us two plot developments, past and present, simultaneously. The recording fills in the gap left by the fade-out: Now we know what happened behind those closed doors. On the visual track, we can watch Myra’s developing anxiety about the couple’s murder plot but, more piercingly, we register her realization that Lester has never loved her.

Across seven minutes, Joan Crawford executes a carefully modulated solo performance, for the most part with no accompanying score. Meanwhile, Palance and Grahame get to act viva voce. And David Miller’s direction scales and times things nicely. I won’t try to analyze the very end of the scene, let alone its frenzied aftermath. I just want to trace the dynamics of the double-layered time scheme the replay machine gives us.

Joanie, more than shoulders

The recorded scene develops from the lovers’ frustration with keeping up a false front, then to their suspicion that Irene will cut Lester out of her will, then to the mistaken belief that she’s just done so, and finally to their decision to kill her. Myra’s playback scene proceeds, I think, in four stages as well. Myra starts out placid and almost giddy in her love for Lester. She’s abruptly shocked and disenchanted when she learns he doesn’t love her; her stomach churns. A third phase consists of her discovery that Lester and Irene intend to kill her, and she devolves into sheer panic. The last phase, of which I’ll show only a bit, initiates a search for a way to defend herself.

Myra comes in euphoric. As she replays her dictation of the night before, she strolls around her study, going far back to the distant refrigerator for a glass of milk and then coming forward. She seems to savor hearing again her own declaration of her devotion to Lester.

Myra’s circuit around her study isn’t just filler: it etablishes the rear area for use later. But now, as she’s about to turn off the recording, she hears Lester’s voice: “What’s up?” She backs up a little, bumping the desk as she realizes that there’s more on the disc. This recoil, as a performance decision, will get magnified in the course of the scene. Then Miller cuts to a reaction shot.

The first of several optical point-of-view shots gives us a close view of the twin SoundScriber units (good for product placement too). Myra has set the milk down on the console.

As we hear Lester venting his contempt for her, Myra’s eyes fill with tears. Worse, he adds that he’d like to tell her he never loved her for a moment. “I’d like to see her face.” He can’t, but we can; in the closest shot yet, she looks right at us. Hollywood can be brutal.

She turns away and, seen from a new angle by the desk, she advances toward us. On the track, Lester is pitching woo to Irene. Myra realizes that he lusts for this other woman. She sighs. Listen closely and you can hear her emit a soft whimper as well.

Another cut to the SoundScriber as Lester says he dreams of holding Irene: “I don’t know how I stand it, not being with you.” On these last few words, cut to Irene, turning away in shame.

She rushes back, having heard enough. A low angle shows her about to switch off the horrible recording when Irene is heard noticing the attorney’s draft of the will on the desk. “It’s the will!” Myra freezes, accentuating the line, and then starts to turn when Lester begins to read the draft.

Having hidden her face from us for a little while, Miller’s direction makes the next close view all the more powerful. (Note the eyebrow work.) Lester’s reaction to the will proves it’s been about the money all along. As he curses Myra, she doubles over grabbing her stomach. This, I take it, is the high point of the scene’s second phase–a sheerly physical reaction to Lester’s cynical betrayal of her love.

Phase three starts, I think, when Irene is heard purring, “Suppose she isn’t able to sign it on Monday.” The line is heard over a shot of the machine, and not a POV at that. The visual narration cunningly delays, by just a few seconds, Myra’s reaction to Irene’s hint. The cut shows her listening, stunned. Lester agrees with Irene. “I’d get it all! Why not?”

Myra turns, as if in disbelief, and a closer view of SoundScriber underscores Irene’s response: “Lester, I have a gun.”

This triggers the scene’s big movement: Myra’s retreat from the recording. Back to the extreme long shot, low angle, as she hurls herself toward the rear wall and sidles along toward the refrigerator, taking refuge behind the chair. The lovers discuss how to arrange an apparent accident, all the while kissing and declaring their love. Lester exclaims, “I’m crazy about you! I could break your bones!” as only Jack Palance could say it.

Again we get an optical POV shot, but now from Myra’s position across the room as Lester muses on “a nice little accident.” And in the cut back to Myra, we hear Irene say, “We’ll work something out. I know a way.” The recording needle is stuck in a groove, and we hear her say it again: “I know a way.” Music comes up for the first time, shifting the action to a new pitch.

I know a way. This mechanical glitch, I think, pushes fear into panic. The tightest close-up yet of the spinning disc is a sort of mental subjectivity: It’s not what Myra sees exactly, but an expression of her being riveted by insistent, maniacal repetition of Irene’s assurance: I know a way. Myra rushes out of the shot and hurls herself into the bathroom to vomit. All the while we hear, again and again: I know a way.

The couple’s plotting has driven Myra out of the room, as the music rises and nearly suppresses Irene’s “I know a way.” In a closer view of the bathroom, Myra staggers to the sink and splashes water on her face, while the record still spins and Irene’s voice taunts her.

But now we get the start of a new phase, with Myra trying to seize the initiative. In a burst of anger she rushes back to the machine, switches it off, and fumblingly takes out the disc. By the time she does so, we’ve heard Irene’s “I know a way” thirty-one times. Talk about hammering the audience.

Myra grips the disc, proof of the criminal conversation, and….

…But my analysis has gone on too long. It’s reasonable, although mean, to stop with the end of the replay. The rest of the sequence builds on what we’ve heard and seen, developing Myra’s efforts to defend herself.

I should note, though, that there follows a hallucinatory sequence in which we get not only perceptual subjectivity, like the POV shots, but also mental imagery and sounds as well. That sequence also includes auditory flashbacks of the usual sort, Myra’s anxious memories of things that Lester and Irene said on the SoundScriber recording. They’re replays of a replay, if you want to get fancy about it.

Conventioneering

In a way this scene is just a variant of a common storytelling convention: Someone accidentally overhears a key piece of information, in an adjacent room or over the phone. But the sequence shrewdly recasts this convention in ways that pay off on many dimensions. We get the suspense attached to the lovers’ mistaken belief that Myra will cut Lester out, and we get Myra’s reaction to it. That reaction is compounded of her sense of betrayal, her disillusion, and her realization that she’s in danger. Had she been eavesdropping on their conversation, she could have burst in on them and denounced their misreading of her will. As it is, she must helplessly listen to them unfold their plans.

After more than a decade of female Gothics–aka”woman in peril” movies, aka I-think-my-husband’s-trying-to-kill-me movies–from Suspicion and Gaslight to Woman in Hiding, Miller and his colleagues found a fresh way to put a lady in a cage. Schema and revision, a key process in the history of any art form, allows ingenious artists to remake what tradition hands them. Twenty years later, Francis Ford Coppola and Walter Murch would build an entire movie, The Conversation, around the audio replay and its possibilities for objectivity and subjectivity. Over and over, the unconventional burrows inside the conventional.

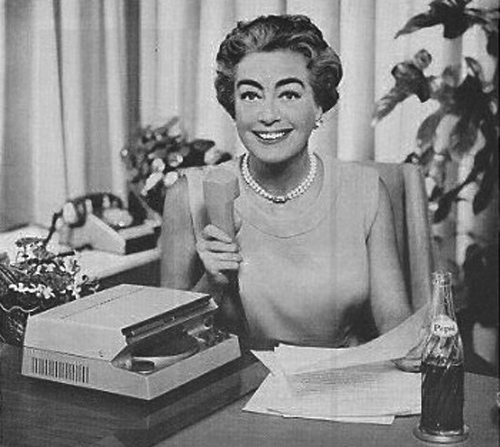

After this film, Joan Crawford became a spokesperson for SoundScriber. (See below.) Who would know better than she the advantages of the gadget? Perhaps Joan even had a stake in the firm. Such fruitful synergy wouldn’t be unknown in Hollywood. Jack Webb found the Teleprompter so useful in shooting Dragnet episodes that he invested in the company.

On All About Eve and Zanuck’s purging of the replay of Eve’s monologue: I suspect that it was a forced byproduct of another decision Zanuck had taken. The film consists largely of flashbacks, and Mankiewicz had intended to move through them by shifting from one character to another. At the awards dinner the flashbacks begin with Karen, and then another block of them, grounded in Margo’s memories, was to take up later episodes in Eve’s ascent to stardom.

But the film ran very long, so Zanuck cut the framing portion at the dinner that would have introduced Margo’s flashbacks. The result is that in Karen’s flashback, we occasionally hear Margo’s narration of certain episodes Karen didn’t witness. But once we’ve lost Margo’s narrating frame, then it becomes quite difficult to justify re-hearing Eve’s ruminations on theatre from anything approximating her point of view. I suspect that consistency of this sort played a role in Zanuck’s cutting Eve’s monologue. Plus it was a pretty daring move on Mankiewicz’s part. And the film is already pretty long. The fullest account of the changes, though still not as specific as I’d like, is in Sam Staggs’ All About All About Eve (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2001), 170-172. As Staggs points out, Mankiewicz did work differential-viewpoint flashbacks into The Barefoot Contessa (1954).

Sudden Fear is available on a so-so DVD transfer from Kino Lorber.

The interplay between film and fiction in the 1940s is fascinating, and we can sometimes find rough equivalents between techniques. Here is a stream of auditory flashbacks in Steve Fisher’s novel I Wake Up Screaming (1941), ending with the protagonist’s inner monologue.

I’d remember Lanny Craig saying: “They crucified me . . . it was because of Vicky Lynn!” And the night Robin Ray said: “She’d laugh, see, and it was like Guy Lombardo’s band playing.” And Hurd Evans: “I only get two hundred and fifty a week.” Tick-tock, the faceless clock on Sunset. “It’s possible to build a case out of nothing,” the assistant district attorney said. Where was Harry Williams? If he’d been murdered, where was his body?

By the end of the thirties, of course, such montages were already heard in radio programs as well.

Joan Crawford was also a spokeswoman for Pepsi-Cola, having married the man who became the company’s CEO. This image comes from a nifty survey of her endorsements available here.

VIFFpix

The big three-oh for VIFF.

DB here:

After several entries (they start here), time for a wrapup.

It was a record-breaking year for the Vancouver International Film Festival: over 150,000 admissions, 386 films, and many awards. Go here for the stats. But linger here for glimpses of friends old and new.

Every night there’s a little, sometimes not so little, reception for filmmakers, guests, the press, et al. in the Hospitality Suite. Sort of like a college mixer, except with better food and everybody talking about movies. On the left we find critic/professor/festival scout Bérénice Reynaud and PoChu AuYeung, VIFF Program Manager and Senior Programmer. On the right, Jack Vermee, Eurocinema expert and Programming Consultant.

More VIFFers at work: Below left, Alan Franey, dynamic Festival Director, with Programming Associate Mark Peranson in the background. With his colleague Jessica Bradford, Justin Mah curates the all-important VIFF videothèque. Below right, Justin (also on the Programming Committee) gets in the holiday mood.

One of the wondrous things about the festival is the access you have to filmmakers. Here’s Kristin with Ann Hui, director of A Simple Life, and Ben Rivers, director of Two Years at Sea.

More fun with filmmakers: Raymond Phatanavirangoon, producer of Headshot, and Charliebebs Gohetia (The Natural Phenomenon of Madness); and Saul Landau (Will the Real Terrorist Please Stand Up?).

Programmers powwow over waffles: Shelly Kraicer, Dragons & Tigers Programmer, and Alissa Simon, Program Consultant for VIFF and Programmer for the Palm Springs Film Festival.

It’s not just for my camera; everybody here grins all the time. On left, Oz festival consultant Geoff Gardner poses with Bruce, while Bruce’s owner Eunhee Cha Brown, Hospitality Suite Manager and all-round organizer, looks on. On right, Tony Rayns, Dragons & Tigers Programmer, reflects on a figure in world film culture who, he reports, “insinuated himself ferretlike into the anus of every major world dictator.”

Other critics get jolly too, not to mention hungry. On the left, Sean Axmaker, proprietor of the excellent Parallax View website (which houses VIFF reports from him and his colleagues Kathleen Murphy and Richard Jameson). On the right, Peter Rist, professor at Montreal’s Concordia University and critic for another fine site, Offscreen. Although my pictures of long-time critical comrade Jim Emerson turned out lousy, you should imagine one embedded here and proceed to his magisterial Scanners site for more VIFF coverage.

Loyal readers of our VIFF missives over the years know that JPG does not stand for Jpeg but rather Japadog. (2009 and 2010 pix here and here). This enterprise is as important as any festival sidebar. Below, a nighttime glimpse of the Japadog wagon conveniently planted outside our hotel. On the right, Professor Jim Udden of Gettysburg College and author of a superlative book on Hou Hsiao-hsien, seated at Japadog Command and Control Center on Robson Street, contemplates the luscious deliciousness that awaits him.

Director Ho Yuhang, critics Chuck Stephens and Robert Koehler, after a JPG feast: From the cut of their strut you know they’re auditioning for Reservoir Japadogs. (Thanks, Chuck.)

Too many more pictures (over 450), lots more to say, many new ideas; but not enough time. (See? Not even time for subjects and verbs.) Suffice it that once more we had a splendid time at this friendly, low-pressure but high-quality festival. You should come next year.

A packed house at The Vogue, a 1941 theatre that had become a music venue in recent years. It was brought into festival service after some years off-duty. Prettier interior shots are here. To see another Granville Street mainstay in its heyday, go here.

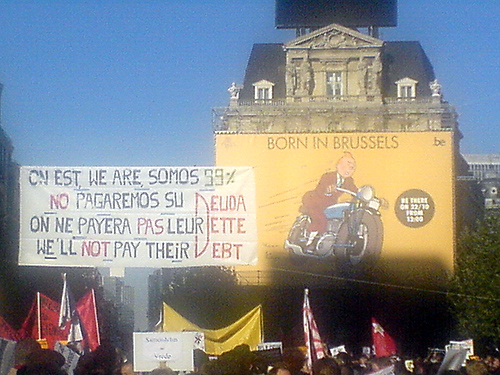

Catching up 99%

Clash by Night.

DB here:

Amplifications, corrections, and updates have been piling up over the last couple of months, and we began to realize that simply appending postscripts to older entries probably didn’t register with many readers. Judging by our stats, revisiting older entries isn’t a priority for most of the souls whom fate throws our way. So here’s some new information about older posts.

*I wrote about Jafar Panahi‘s This Is Not a Film at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Today Variety reported that an appeals court has upheld Panahi’s sentence of six years in prison and a twenty-year ban on travel and filmmaking. His colleague Mohammad Rasoulof’s jail sentence was reduced to a year. Panahi’s attorney says that she will appeal the decision to Iran’s Supreme Court. Be sure to read the Variety story for some background on the despicable treatment of other filmmakers, notably a performer who, merely for acting in a movie, was sentenced to a year in jail and ninety lashes.

*My trip to the Hong Kong festival last spring was to have included a visit to Japan. But the earthquake and the tsunami decided otherwise. Here are two remarkable items about the country’s catastrophe and the people’s resilience. First, a camera captures what it’s like to be in a car that’s swept away. Then we have photographs of the remarkable recovery that some areas have made–a real tribute to Japanese resilience. (For the links, thanks to Darlene Bordwell and Shu Kei.)

*My trip to the Hong Kong festival last spring was to have included a visit to Japan. But the earthquake and the tsunami decided otherwise. Here are two remarkable items about the country’s catastrophe and the people’s resilience. First, a camera captures what it’s like to be in a car that’s swept away. Then we have photographs of the remarkable recovery that some areas have made–a real tribute to Japanese resilience. (For the links, thanks to Darlene Bordwell and Shu Kei.)

*At Fandor, in response to Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, Ali Arikan wrote a penetrating and personal essay that I wish I’d had available when I wrote my review at VIFF.

*Tim Smith‘s guest entry for us, “Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD,” was a huge hit and went madly viral. At his site, Continuity Boy, he has posted a new, no less stimulating entry on eye-scanning. It shows that we can track motion even when the moving object isn’t visible!

*During my trip to Brussels in early September for the conference of the Screenplay Research Network, I stole time to visit the superb Galerie Champaka for the opening of its show dedicated to Joost Swarte (above). Longtime readers of this blog know our admiration for this brilliant artist, so you won’t be surprised to learn that I had to get his autograph. The show, consisting of work both old and new, was also quite fine; it’s worth your time to explore the pictures, such as the one revealing how Disney was inspired to create Mickey (above). Thanks to Kelley Conway for taking the shot, and to Yves for taking this one. And special thanks to Nick Nguyen (co-translator of two fine books, here and here) for alerting me to the show.

*An update for all researchers: Now that we have online versions of the Variety Archives and the Box Office Vault, we’re happy as clams. (But what makes clams happy? They don’t show it in their expressions, and their destiny shouldn’t make them smile.) Anyway, to add to our leering delight, we now have the splendidly altruistic Media History Digital Library, which makes a host of American journals, magazines, yearbooks, and other sources available in page-by-page format, ads and all. You’ll find International Photographer (too often overshadowed by American Cinematographer), The Film Daily, Photoplay, and many more. Get going on that project!

*This just in, for silent-cinema mavens: The Davide Turconi Project is now online, thanks to a decade of work by the Cineteca di Friuli. Turconi was a much-loved Italian film historian who, among other accomplishments, collected clips of frames from little-known or lost films. The archive of 23,491 clips, usually consisting of two frames, is free and searchable. On the left we see a snip from Louis Feuillade’s Pâques florentines (Gaumont, 1910). Paolo Cherchi Usai and Joshua Yumibe coordinated this project, with support from Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto, George Eastman House, and the Selznick School of Film Preservation. (Thanks to Lea Jacobs for supplying the link.) For more on Josh’s research, see our entry here.

*This just in, for silent-cinema mavens: The Davide Turconi Project is now online, thanks to a decade of work by the Cineteca di Friuli. Turconi was a much-loved Italian film historian who, among other accomplishments, collected clips of frames from little-known or lost films. The archive of 23,491 clips, usually consisting of two frames, is free and searchable. On the left we see a snip from Louis Feuillade’s Pâques florentines (Gaumont, 1910). Paolo Cherchi Usai and Joshua Yumibe coordinated this project, with support from Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto, George Eastman House, and the Selznick School of Film Preservation. (Thanks to Lea Jacobs for supplying the link.) For more on Josh’s research, see our entry here.

And while we’re on silent cinema, Albert Capellani is in the news again. Kristin wrote about this newly discovered early master after Il Cinema Ritrovato in July. A recent Variety story discusses some recent restorations and gives credit to the Cineteca di Bologna and Mariann Lewinsky.

*My entry on continuous showings in the 1930s and 1940s attracted an email from Andrea Comiskey, who points out that when Barbara Stanwyck and Paul Douglas go to the movies in Clash by Night (above), she prods him to leave by pointing out, “This is where we came in.” Thanks to Andrea for this, since it counterbalances my example from Daisy Kenyon, which shows Daisy about to call the theatre for showtimes. And since posting that entry, I rewatched Manhandled (1949). There insurance investigator Sterling Hayden hurries Dorothy Lamour through their meal so that they’ll catch the show. He apparently knows when the movie starts. So again we have evidence that people could have seen a film straight through if they wanted to. It’s just that many, like channel-surfers today, didn’t care.

*Finally, way back in July, expressing my usual skepticism about Zeitgeist explanations, I wrote:

I’m still working on the talks [for the Summer Movie College], but what’s emerging is one unorthodox premise. As an experiment in counterfactual history, let’s pretend that World War II hadn’t happened. Would the storytelling choices (as opposed to the subjects, themes, and iconography) be that much different? In other words, if Pearl Harbor hadn’t been attacked, would we not have Double Indemnity (1944) or The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945)? Only after playing with this outrageous possibility do I find that, as often happens, Sarris got there first: “The most interesting films of the forties were completely unrelated to the War and the Peace that followed.” Sheer overstatement, but back-pedal a little, and I think you find something intriguing.

David Cairns, whose excellent and gorgeously designed Shadowplay site is currently rehabbing Fred Zinnemann, responded by email:

Firstly, I find the start of WWII being equated with Pearl Harbor a little American-centric. Much of the world was already at war when that happened. Secondly, it could certainly be suggested that the two films you cite WOULD have been different without a world war. Billy Wilder and Robert Siodmak were comfortably making films in France before Hitler’s invasion drove them to a new adopted homeland. Those movies might well have happened without WWII, but they would probably have had different directors.

Thanks for this. Your points are well-taken. Not only was I America-centric, but I neglected to point out that before Pearl Harbor America was more or less directly involved in the war. Even though America wasn’t yet in the war in late 1941, a lot of the economy was on a war footing and the industry was already benefiting from the rise in affluence among audiences.

Your point about the particular directors is reasonable too. I think I chose bad examples. All I wanted to indicate was that the Hollywood system continued to function as usual, particularly with respect to narrative strategies. For instance, Chandler wrote the screenplay for DOUBLE INDEMNITY (and apparently was responsible for the flashback construction), and as you say, had another director handled it, at the level of narration it might well have been the same. UNCLE HARRY is a harder case for me, I admit! Maybe I should have chosen THE BIG SLEEP and MURDER, MY SWEET!

David replied with his usual generosity:

That’s OK! BIG SLEEP and MURDER MY SWEET definitely work! Plus any number of non-flag-waving musicals, westerns, swashbucklers (though there’s a little propaganda message in THE SEA WOLF at the end) and certainly comedies and horror. . . .

And then there’s KANE and AMBERSONS.

Better late than never–something you can say about all these updates.

More VIFF vitality, fancy and plain

I Wish.

DB here:

Back from Vancouver Internatonal Film Festival, we’re still assimilating. We just learned of the winners, but here are some more movies that won my admiration.

Three lives, four-plus hours

Art cinema has been attracted to mystery and intrigue plots since at least The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Antonioni needed an enigmatic disappearance to get L’Avventura going. Before and after there were Cronaca di un amore, La Commare Secca, Blow-Up, La Guerre est finie, and the works of Robbe-Grillet. Not to mention Vagabond and Toto les héros and, venturing to Asia, Chungking Express and Fallen Angels.

True to this tradition, in Dreileben (Three Lives, 2011), conventions of festival cinema—elliptical transitions, ambiguous dream sequences, retrospectively identified point-of-view shots, anecdotal realism, de-dramatization, open endings—punctuate, and puncture, a killer-on-the-loose scenario. The genre is respected to the extent of supplying teasing clues, some conveniently recorded on video and in an old photograph. (Shades of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.)

The murder-mystery element is, I think, part of the reason that this TV installment-story has been making the festival rounds. Yes, there’s also its pedigree (three accomplished directors) and its use of the now-common strategy of network narrative. Each of the three episodes focuses on different characters whose paths cross. We get pieces of the whole story; scenes glimpsed in one episode are fleshed out in another.

The tryptych format recalls the Belgian Trilogy (Lucas Belvaux, 2002). But that exercise retold its story by centering on a core of characters, replaying events and switching point of view (and genre) from film to film. Dreileben’s first two episodes focus on characters at some remove from the crime and the criminal, a strategy that redefines what counts as the central situation. Moreover, and unlike most network narratives, these plots show few points of contact. Characters connect very rarely across episodes, so that each tale gains a weight of its own. The mad-killer element comes to seem secondary for quite a while.

The first episode, Beats Being Dead, directed by Christian Petzold, is largely organized around the perspective of Johannes, a young medical student about to embark on a prestigious fellowship. He becomes attached to a moody immigrant woman working in a nearby hotel. Over the romance hovers not only a brutish biker club but also a mental patient, accused of murdering a girl, who escapes from Johannes’ hospital and lurks around the forest. This episode is presented in a clean, almost enameled visual style sharpened by the abrupt scene shifts characteristic of modern cinema.

The second part, Don’t Follow Me Around (Dominik Graf), seemed to me the strongest. Johanna, a female police psychologist, is brought to the town, apparently to profile the criminal, but actually to conduct a rather different investigation. She stays with an old friend and her husband, and Johanna’s visit opens up a new psychodrama all its own. The rather narrow focus of the first, on a romantic triangle, here widens to consider frayed friendships, marital suspicions, and old passions. The character relationships get more complicated as things move along. The somewhat informal framings and jerky cutting (nearly three times as many shots as in the Petzold, in about the same running time) accentuate Johanna’s discomfort and her eventual moments of confronting her past.

After two films hovering around the fringes of the crime, the third installment, One Minute of Darkness, signed by Christoph Hochhausler, seems to go to the heart of things. Now we follow the escaped lunatic Molesch pursued by Markus, a cop so flagrantly unhealthy that he seems to risk a coronary every time he rises from his sagging armchair. Yet this detective story turns out to be not quite as cut-and-dried as we expect. That’s partly because of Molesch’s encounter with a little girl and partly because the first episode is revealed in retrospect to unfold in a more indeterminate time frame than we might have thought. The film doesn’t plug every gap, I think; I left thinking we needed a fourth or fifth installment. But that’s probably part of the point.

Genre conventions permeate all three episodes, which seriatim present twentysomething romance, simmering melodrama, and classic sleuthing and pursuit, all spiced by stalker-in-the-shadows atmospherics. Dennis Lim’s illuminating essay indicates that this trio of films is the product of a German debate about how filmmakers committed to “auteur cinema” can deal with matters of genre.

More broadly, works like Dreileben characterize much of today’s festival moviemaking: an effort to graft modernist narrative strategies onto a genre-driven plot premise. (We see it in The Skin I Live in too.) A cynic could argue that a serial-killer investigation serves to attract audiences who might be put off by purely formal gymnastics. But actually mystery plots, based on hiding information and misdirecting our attention, mesh well with the narrational maneuvers of international art cinema. If crossover films like this bring in more viewers, that’s a side benefit of merging two robust traditions—a storytelling mode that hides and then reveals secrets, and one that believes that even when revealed, secrets remain secretive.

POV = Perplexities of Vision

Headshot.

The barely-converging fates of Dreileben reminded me of the network knitting of Johnnie To’s Life without Principle. In a similar way, two exercises in optical point-of-view echoed the last sequence of Panahi’s This is Not a Film. In that non-film, the camera abandoned by a cameraman seems to be picked up by Panahi himself and carried beyond what we normally think of as “house arrest.” But one of the resources of the POV shot is that it can coax us to ask who’s seeing what we see. If we aren’t given an identifying shot of the looker, we can start to wonder. Played upon in countless horror movies to hint at the eyes of the stalking monster/ killer, the unspecified POV in Panahi’s hands (or perhaps not in his hands) becomes charged with political consequence.

Optical POV isn’t as fully exploited as you might expect in Pan-ek Ratanaruang’s Headshot. One of its premises is that Tul, a contract killer, is wounded in the cranium and as a result sees the world upside down. But the trauma takes place in the first few scenes, and what follows until the midpoint is a set of flashbacks explaining how he became a gun for hire. Present-time episodes showing him getting adjusted to his affliction alternate with past-tense scenes that supply him with motives for revenge.

So far, so noirish. Indeed, the iconography (crooked lawyers, not one but two femmes fatales, chiaroscuro scenes) and the plot (flashbacks, voice-overs, double- and triple-crosses) put us in familiar, quite enjoyable territory. Needless to say, like nearly all film noir heroes Tul has never seen a film noir, so he can’t sense the walls closing in as quickly as we can. He remains idealistic—“I may kill people, but I’m not a crook”—and trusting to a fault.

The upside-down POV works okay as a general pointer to the film’s Buddhist thematics, but the inverted shots are fairly few, introduced to defamiliarize a bit of action. They aren’t exploited as a thoroughgoing formal device. For a while vision scientists believed, mistakenly, that when people wore inverting spectacles, they eventually learned to see the world rightside up. Is Ratanaruang suggesting that Tul adapted in this way?Early in the film the hero pins pictures on his wall upside down, but near the film’s end I thought I saw a shot ostensibly through Tul’s eyes showing us the inverted pictures on the wall, rather than the way they’d look if he saw upside down. In real life, as if it were relevant, it seems that wearing inverted spectacles doesn’t make you see things right way round eventually. The world always looks flipped. But you can adapt to this upside-down array fairly quickly and execute normal activities like riding a bicycle and even reading. Presumably this explains why Tul’s marksmanship remains lethally good in the gunplay finale.

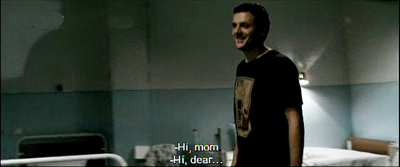

Far more consistent–obsessive, actually–is the play with optical POV in the Romanian film Best Intentions by Adrian Sitaru. When Alex’s mother has a stroke, he leaves Bucharest to visit her. She’s recovering reasonably well, but Alex becomes so anxious about her care that he makes life miserable for her, his father, his girlfriend Lia, and the doctor, an old family friend. After the first scene, when Alex gets the call about her stroke, a drastically totalizing POV system kicks in. Whenever Alex is in the presence of anyone else—major character, minor character, onlooker—we see him through that person’s eyes. If he’s alone, usually on the phone, the shots of him are unassigned and objective, but when he’s in public, he’s only shown subjectively. Moreover, we never get a POV shot from his perspective.

A narrational game emerges. When Alex is interacting with only one other person, we quickly grasp who the Unseen Seer is. For instance, we understand that he’s met at the train by his father, identified by his offscreen voice.

When Alex first visits his mother in the hospital, however, the POV floats momentarily. At first it might seem we’re seeing Alex’s entry through his mother’s eyes,when he briefly acknowledges the camera’s field of view.

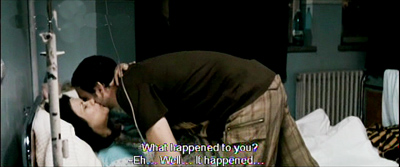

But when he moves past, we realize we’re seeing him from the viewpoint of the woman in the bed beside his mother’s.

When he’s with only one other character, the scene plays out without cuts. When cuts come within a scene, they’re motivated as shifts from one character’s POV to another’s. Here we first see Alex and his mother through the eyes of the patient across the room, whom we glimpse in the background during his entrance above. When the mother’s neighbor looks at them, that motivates a closer view of them.

This tag-team POV becomes quite engaging when several characters are present. In a dazzling scene of three couples drinking around a tavern table, the dialogue is fast-moving and the cuts come quickly. I found myself trying to chart exactly whose view we’re getting. Sometimes the POV gets anchored retroactively: one of several characters we see in shot A becomes the POV vessel in shot B. For more fun, the system develops in unexpected ways as the movie proceeds.

The experiment is worthwhile, and not just as a formal game. Recall Erving Goffman’s notion that social life is a stage in which we enact the roles that put us in a good light. Best Intentions shows Alex as not only a caring son but a guy earnestly playing a caring son. In the Theatre of Everyday Life, he’s something of a drama queen. Of course he’s partly right to be concerned about the health-care system (he’s probably seen The Death of Mr. Lazarescu), but that concern also handily motivates his incessant performance of his part.

As a result of Sitaru’s rigorous formal constraints, Alex is onscreen for nearly every instant of this 101-minute movie. (The very brief exception is itself of interest.) His narcissism, his urge to control others, and his inability to really listen to his family and friends—all are perfectly captured by a stylistic strategy that constantly gives him center stage. I haven’t seen Sitaru’s previous film Hooked (2007), but that too used an enveloping POV strategy. Interestingly, there he assigned all three major characters optical POV shots. In Best Intentions, denying Alex his own POV underscores his fretful obliviousness to what anyone else thinks. He makes a scene in every scene, becoming an object of fascination and frustration, for others and for us.

Calming down

All these films, as well as others we’ve discussed in this year’s VIFF, might seem to support the idea that Form Is the New Content. It takes a film like Hirokazu Kore-eda’s I Wish to remind you of the power of less convoluted storytelling. Like Still Walking, it’s a family drama-comedy, but a little more somber and a little more comic. Devastatingly simple, too.

A family has split up. One brother, Koichi, stays with his mother and grandparents in Kagoshima, where the volcano splutters ashes into the air. The younger brother, toothily grinning Ryu, has gone off to Fukuoka with father, a scruffy rock guitarist. The boys communicate by phone, hoping to reunite the family.

They hatch a plan. They’ve convinced themselves that if they make a wish at the precise moment that two bullet trains pass one another, that wish will be granted. So Koichi and Ryu plan a pilgrimage that eventually encompasses their pals and that becomes a confrontation with the mundane realities of death and solitude, mitigated by comradeship and the hospitality of strangers.

The boys’ situation ripples outward to encompass the grandparents’ friends and the sons’ schoolmates and their parents, all of whom earn quietly incisive vignettes. Routines—classroom encounters, swimming sessions, Koichi’s run-ins with teachers, Ryu’s nights out with dad’s band—are recycled without fuss, building up a textured sense of each boy’s world. Kore-eda presents everything so unemphatically that he makes film direction look very easy.

Despite lacking the fanciness of the modern network narrative and its disjunctive time schemes and viewpoint switches, Kore-eda’s plot, like that of Ozu’s Early Summer, effortlessly creates a ramifying world in which our boys feel at once comfortable and apprehensive. Come to think of it, some of the kid comedy recalls the two brothers’ antics of I Was Born But, and the surprisingly sympathetic young teachers, reminiscent of the adults in Ohayo, become co-conspirators and, a little bit, surrogate parents. I Wish is a modest movie; it almost lowers its eyes in front of you. It’s also the closest thing to perfection that I saw in Vancouver.

For a lively roundup of ideas on Dreileben, see David Hudson’s Daily MUBI entry. An informative presskit is here. Headshot has been bought for US release by Kino Lorber. An informative interview with Adrian Sitaru is here. I discuss arthouse genre crossovers in an earlier year’s entry from VIFF. For a more thorough study of network narratives, see “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance” in my Poetics of Cinema.

23 October 2011: Thanks to Christoph Huber for correcting an error in the initial post. Although there is a town called Dreileben, the film doesn’t take place there, as I had said.

I Wish.