Archive for September 2013

THE GRANDMASTER: Moving forward, turning back

DB here:

The summer has brought us two major films by the two leading Hong Kong directors. I’ve discussed Johnnie To’s fine Drug War earlier. Now it’s time for some ideas about The Grandmaster. Wong Kar-wai’s film displays, in fairly straightforward ways, some of his typical artistic and commercial strategies. Here he adapts his characteristic approach to style and form to a classic genre—and to the demands of the marketplace.

On kung-fu considered as one of the fine arts

Wing Chun is the best-known and most influential Chinese martial art in the world. It owes its renown to two women and two men. In the 1700s the Buddhist nun Ng Mui developed a style called Plum Flower Fist, and a young woman named Yim Wing Chun adapted it into something requiring less strength. Bruce Lee trained in the style, revised it according to his interests, and popularized it in films that reached millions of viewers. Lee’s teacher was Ip Man, a master who settled in Hong Kong after World War II and set up a school. Ip made public a Southern fighting technique that had previously been shared among families and friends.

As both a mainlander and a Hong Konger, Ip is a good symbol of the union of two Chinas. Given the stunning rise of China’s economic and cultural power since the 1980s, it’s not surprising that someone would come up with the idea of a film about him.

Wong Kar-wai claims to have had that idea in the late 1990s. In 2002, he announced that a film about Ip was on his agenda. After finishing 2046 (2004) and an episode for the portmanteau film Eros (2004), he seemed to move forward, slating Tony Leung Chiu-wai as the star and bringing Ip’s family aboard as consultants. But other activities intervened, notably an ill-fated three-picture deal with Fox Searchlight. Wong continued to occupy himself with his other businesses, including his lucrative talent-management firm and his advertising unit, which made commercials for Dior, Lacoste, Motorola, and other companies. He also directed My Blueberry Nights (2007) and recast Ashes of Time (1994) as Ashes of Time Redux (2008).

In 2009 he got to work on the Ip Man film, eventually bringing in funding from many sources, including mainland Chinese companies, Fortissimo, The Weinstein Company, and Annapurna Pictures. Scheduled for a premiere in late 2010, then late 2012, it didn’t appear until January of 2013. It seems that he was still doing postproduction in Thailand hours before its first press screening in Beijing.

During the ten years that The Grandmaster took to reach the screen, other filmmakers had seized on the great man’s life. Two popular Donnie Yen vehicles, Ip Man (2008) and Ip Man 2 (2010), were followed by a prequel The Legend Is Born: Ip Man (2010), and this year, after Wong’s film was released, Ip Man: The Final Fight.

However much Wong fiddles with his movies, in this case he kept the title fixed: Yi Dai Zong Shi. It literally means “The Grandmaster of That Era,” or—since Chinese doesn’t mark plurals in the noun—“The Grandmasters of That Era.” It’s significant that in early publicity, the project was known as The Grandmasters. Wong says his son talked him out of that title. Now, in non-Chinese-speaking countries, it’s The Grandmaster.

The ambiguity about the title takes on special relevance because we have several Grandmasters. After the Beijing premiere, The Grandmaster was released throughout China and in Hong Kong. It did good business, earning over US $47 million in those territories. Wong made a shorter version for the European market, and that was apparently the one premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in February. A still shorter version was prepared for the U.S., with The Weinstein Company as distributor. It opened in August, to mostly good reviews, and it has currently reaped about $6 million at the American box office. So far, the film’s worldwide gross is nearly $63 million, making it by far Wong’s most commercially successful theatrical release.

Will the real Grandmaster please…?

The three versions tell variants of a core story that starts in southern China in the 1930s. A curtain-raiser shows Ip defeating a rambunctious gang who attack him in a downpour. Although the scene’s place in the plot seems not to be specified, in part it serves as a flamboyant demonstration of Wing Chun’s ability to defeat the powerful leg-fighting techniques characteristic of Northern styles. We then get a prologue in which Ip, the son of a wealthy family, recounts his lifelong dedication to kung-fu. Comfortable with his wife and children in Foshan, he says that he lives in an eternal spring, harking back to the meaning of the name Wing Chun (“celebrate springtime in song and poetry”).

A Northeastern master, Gong Yutian, comes to Foshan looking for a major bout with a talented newcomer before he retires. Ip is picked to fight him, and after some testing by local experts who practice Gong’s signature styles, the match takes place. It’s a waltzing, sidling encounter that Ip wins through nuance, not brute force. Gong retires gracefully, but his daughter Gong Er considers her father disgraced and demands a match with Ip. She applies her father’s tough Bagua technique, with its dazzling handwork and spinning evasions, and defeats Ip. In the course of the match, he becomes fascinated with her. When Japan takes over China in 1937, their rematch is postponed, and they pursue their lives separately for several years.

Ip struggles to survive. He refuses to collaborate with the occupiers and feeds his family on what he can scrounge. Gong Er’s problem revolves around the renegade disciple Ma San, who kills her father in a duel and takes over the school and compound. Ip’s two daughters die, and after the war he migrates to Hong Kong, hoping his wife can join him. But after the Chinese revolution, the border is sealed and he never sees his wife again. Gong Er also winds up in Hong Kong; she managed to reclaim her father’s estate by defeating Ma San, but she has vowed never to marry or to teach kung-fu. She has become a doctor instead. When Ip meets her again, she is already in poor health, partly because of the fight with Ma, but also because of her opium addiction.

Other characters wind their way through the story, most notably Gong Yutian’s brother and Razor, a partisan during the Japanese occupation who quits the Kuomintang to become a barber in Hong Kong. By the end, Ip is the last of the era. As Gong passed the torch of martial arts to him, so he will pass it to many others. Apparently a passive character, especially compared with Gong Er, Ip illustrates the “horizontal/vertical” maxim he starts with: “Stay standing and you win.”

Without counting the credit sequences, the three versions have running times as follows: 124:26 for the China/Hong Kong release; 114:24 for the European release; and 100:52 for the U.S. release. Some American critics have objected to the third version’s radical compression, and indeed much of interest has been lost. Yet many of the changes we encounter in the U. S. version were already present in the European one. To complicate matters, versions two and three aren’t simple cutdowns of the long one. Some shots and sequences are rearranged, and both the second and third versions contain footage, indeed entire scenes, not present in the “original.”

In other words, the usual Wong drill. He is famous for showing up at a film festival just in time, the print moist from the lab, and then recutting it after its premiere. Sometimes the changes result from external pressures: the international cut of Ashes of Time begins and ends with staggering fight scenes added at the behest of its Taiwanese producers. But often Wong tinkers with his footage on his own. He trimmed 2046 by fifteen minutes after its Cannes bow. There are at least two versions of Chungking Express, and at least three of My Blueberry Nights. There are two versions of Days of Being Wild, one with a game-changing prologue. (I talk about that here.) And of course Wong redid Ashes of Time fourteen years after its initial appearance. (I consider the results here.) At one point he talked about issuing a vast DVD set including all the variants of all his films. The constant fiddling that drives him to make his films in postproduction doesn’t end with the premiere.

So I think we ought not to assume without more evidence that Wong was forced to change what was a definitive version. For him, I think, a film may never assume a final shape. This is the man who considered putting all the footage shot for Happy Together on the Internet for fans to cut together however they liked. It may have been a publicity ploy or a passing fancy, but the very fact he voiced it suggests an openness to endless revision.

According to a valuable piece by Justin Chang in Variety, Wong worked with Harvey Weinstein on both the European and the American versions. I don’t know the full story of this collaboration. But if Weinstein insisted on a still shorter version for America, Wong’s simplest course would have been to take the European cut and pare it down, adding even more expository titles to plug the gaps. The fact that he rearranged footage and added new material suggests that he took the new constraints as something of a challenge. He once suggested:

Why does Godard come up with the jump cut? He made the films too long, so he had to take out some of the shots randomly. So you have to be flexible. And sometimes those restrictions become your source of inspiration.

Told to make a movie shorter, Wong seems to seize the excuse to rework his footage one more time—to create reorderings, connections, and emphases that bring out different facets of the material. “Instead of doing a short version,” Wong has claimed. “I wanted to do a new version. I wanted to tell the story in a different way.”

Not incidentally, coming of age as a director in the era of home video, Wong is also aware of some commercial benefits. There are plenty of people who will happily buy all three cuts of The Grandmaster on disc. They’ll enjoy picking out different scenes and juxtapositions while still hoping for a full cut in the years to come. A part of Wong’s fanbase has come to expect, and enjoy, his makeovers.

A Chinese kaleidoscope

Wong doesn’t finalize a script, overshoots vastly, and may return for more footage years after the crew and cast thought the scene was done. Once he gets a new idea he can scrap months of expensive work. A big set built for the future world of 2046 went unused. “Thank God,” sighs his former DP Christopher Doyle, “there is no one else in the world who works this way.”

All these tactics give him great flexibility in creating different versions, and so does his characteristic style. Wong’s techniques and his stories facilitate fleshing out parts, snipping out other parts, and recombining still others. This sort of reworking can’t be done so freely when narratives are more linear and the visuals and sounds are more tightly tied to the action. Since Wong makes his movies out of pieces that can be recombined in many ways, each film is like a kaleidoscope. Shake it, and the pieces reconfigure.

At the level of the action, he can achieve this fluency through flashbacks and, in particular, his strategy of multiple-protagonist plots. Most filmmakers are content to focus on one central character, or possibly two, such as a romantic couple or a pair of police investigators. Other characters are definitely subsidiary, and they get identified in relation to the causal actions driving our prime movers.

As Tears Go By, Wong’s first film, centers on one protagonist, while Happy Together concentrates on a couple. Other Wong films, though, exhibit more complicated narrative maneuvers. In the Mood for Love takes the familiar form of two romantic triangles (as in Lubitsch’s The Marriage Circle). The husband of one couple is having an affair with the wife of the other. The innovation is that we almost never see their liaisons; in fact, we don’t see either of the adulterous spouses directly. The plot’s focus is entirely on the two wronged partners, who fall in love with each other. This is a good example of how restricted narration can reshape our sense of plot structure.

Sometimes we have parallel protagonists: two characters who aren’t embarked on the same enterprise (they may not even know each other) but who claim our interest equally. In Chungking Express, each of two policemen has broken up with one girlfriend and is in the process, vaguely, of finding a new one. Here Wong’s bold stroke is to avoid interweaving the two men’s stories. Instead, he simply spliced the end of one cop’s story to the beginning of the next, with a shared space, the Midnight Express fast-food joint, linking the two. Something similar happens in 2046, in which one protagonist is a novelist and the other dwells inside the writer’s fiction.

More drastic is the strategy of creating a central character as a point of intersection of other fates. Days of Being Wild puts the pouting, selfish Yuddy at its center, and other characters are his friends, relatives, and lovers. But Wong goes on to create significant plots around those characters too, giving us a sort of network narrative. The policeman Tide, for instance, is pulled into the action by meeting Li-Zhen, after she has been discarded by Yuddy. Tide will, by coincidence, eventually meet Yuddy in the Philippines. Even further away is the mysterious man played by Tony Leung Chiu-wai, who appears in an epilogue grooming himself to go out. This last-minute walk-on of a character with no apparent connection to the action remains a daring innovation. But one version of the film sets up a prologue in which the man is seen starting to dress up while his voice-over reflects on a man he knew—presumably Yuddy.

In similar fashion, the bounty-hunter agent Ouyang Feng in Ashes of Time is at the center of a web of relationships. His friend Huang Yaoshi not only courts the woman Ouyang yearns for but also tries to seduce Peach Blossom, the wife of a blind swordsman who comes to Ouyang looking for work. A brother and sister, named Yin and Yang and played by the same actress, complicate the plot still further. Like Yuddy in Days of Being Wild, Ouyang Feng connects several characters and becomes for the most part the central consciousness of the film—the first among equals, we might say.

These patterns are, famously, not scripted in detail. They emerge from Wong carving into masses of footage and building his plots in postproduction. But this can lead to brutal surgery. An entire plotline involving pop diva Shirley Kwan was cut from Happy Together, and Maggie Cheung was startled to discover she barely appeared in 2046.

There’s some evidence that The Grandmaster was once planned to be something of a multiple-protagonist film, with Ip Man serving as the point of intersection in the manner of Yuddy and Ouyang Feng. Part of that evidence is internal to the film, chiefly involving the brusque introduction and departure of Razor in all versions. In addition, Wong has talked in an interview about modeling the four-hour version of his film on a traditional Chinese novel format, the zhanghui xiaoshuo.

What appeals to Wong in this “chaptered novel” genre is that it offers a set of linked, fairly developed stories concentrating first on one character, then on another. Major characters in one section could reappear as minor ones later.

A novel like this never follows any particular character. A main character in one chapter may just hurry away in another chapter. The author will continue by telling another story. I think that this structure is unique to the Chinese novel. Such is life. Suppose you meet a very good friend. Next time you meet him, he has moved to Chengdu. And five years later you meet him again. That’s the structure of the four-hour version.

However, this structure is too free for contemporary audiences to follow. Therefore, in the two-hour version, I chose to tell the story in a chronological way, from 1936 to the end of the story.

We have to remember that in interviews, Wong often tries to tie his films to the traditions of the culture he’s addressing. In the west he called his films with Chris Doyle “jam sessions,” and he compares their structure to the novels of Puig and Garcia Marquez. This isn’t bad faith, I think; it’s just that Wong is looking everywhere for analogies to the sort of decentered organization he favors. And his evocation of traditional novels like The Water Margin (ca. 1368) does capture some of the centrifugal organization of Days and Ashes.

In any case, it seems likely that that what was once called The Grandmasters might have become a panoramic survey in the manner Wong indicates, with Ip Man as a connecting thread. In the course of filming he doubtless expanded the roles of figures who became marginal. Perhaps the 130-minute version was already something of a compromise with this more sprawling structure.

Splits and mergers

Wong has carved somewhat different films out of his mass of material. For one thing, he has shifted some big blocks.

The Chinese and European versions of The Grandmaster follow Ip Man’s life up through the Japanese invasion. Then the plot follows Gong Er for about twenty minutes. On a train, she helps the wounded Razor (our first sight of him) as he avoids the Japanese. After the collaborator Ma kills her father, he installs himself in the household and blocks Gong Er from her rightful place. She consults with her father’s disciples and confronts Ma in the compound. There she warns him that she will take back the Gong legacy. She slips off her engagement ring and returns it to her fiancé. In a temple, where she seeks out permission from her father’s spirit, she vows chastity. She snips off a strand of hair, burns it in a candle flame, and encloses the ashes in a box. (In the European version, we see her cut it; in the Hong Kong version, we simply see her close the box, while a late flashback shows her cutting the hair.) At that point we leave Gong Er’s storyline unfinished. We move to 1950 Hong Kong, where Ip starts to establish himself as a teacher.

Only after we have followed Ip’s Hong Kong stay for some time do we learn the outcome of Gong Er’s struggle with Ma San. In a flashback apparently prompted by her encounter with Ip, we see her climactic meeting with Ma at the railway terminal in 1940. In that duel, she defeats him and takes back the Gong school, at the cost of serious injuries. Somewhat later we have Ip’s reflection that in Hong Kong Gong Er stopped seeing her patients and started smoking opium. Their final meeting takes place in a teahouse, followed by her drugged reverie recalling her happiest days, training in the snowy north. After their last encounter, a servant brings Ip the box bearing the ashes of her hair.

In these two versions Wong has followed the idea of chopping up his tale novelistically. Gong Er’s wartime experiences are split into two parts, creating some suspense through the middle portion of the film: Will she reclaim her legacy, and what made her come to Hong Kong? Moreover, the Chinese and European versions don’t give us a smooth pairing-up of Ip and Gong Er. Their meetings are broken up by other pieces of action. After Ip visits her, but before her flashback, we get a scene of Ip meeting Master Gong’s brother reminiscing about their lost world and the dark side of the kung-fu tradition. “Forget 64 Hands,” he warns Ip. Then, without any lead-in, we get Gong Er’s flashback to the fight with Ma. After that, instead of moving directly back to Ip’s story, we get a 1952 scene showing Razor in his barbershop thrashing a man seeking money for his mother’s funeral.

He’s so impressive that the victim wants to be his disciple, and Ip’s voice-over tells us that Razor founded his own school, bringing Baji boxing to Hong Kong. Only then do we return to Ip’s report on Gong Er’s decline.

A cynic would argue that some of these comparatively unrelated sequences had to be retained because Razor, played by Chang Chen, is a significant Taiwanese star and cutting him out would be bad for business. But we know from the U. S. version that Wong did have footage bringing Razor more firmly into Ip’s line of action. So Wong has kept to his model of digressive interruptions, wedging these “chapters” in among larger story arcs.

For the American version, Wong has ironed out some of the bumps. In that cut, we are with Ip Man from the start and mostly throughout. After the confrontation in the Gold Pavilion brothel and the exchange of letters, the narration doesn’t adhere to Gong Er until Ip meets her again in Hong Kong. In a longer version of their encounter, after he leaves her apartment she drifts onto the roof, musing in voice-over, “Mr. Ip, it was ten years ago….” Then we get in one long chunk Ma San’s takeover of the household and her eventual victory over him. The scene of Er’s meeting Razor on the train is gone, as is his barbershop fight in Hong Kong. Overall, the scenes bearing on the Ip/Gong Er phantom romance are joined in a smooth flow that ends with a version of her opium reverie. It’s as if Wong thinks that Americans want a more continuous plot than the zhanghui form provides.

Before we condemn this as dumbing down, we should consider that Wong has done something like it before. The embedded stories of Ashes of Time are treated as lengthy, mostly uninterrupted blocks centered on this or that character, flashbacks included. In several of his films, Wong follows a Hong Kong industry practice of organizing the overall plot reel by reel, with one or two reels devoted to each character’s embedded story. The effect of gathering the Hong Kong kung-fu scenes in one batch and the romance scenes in another keeps the focus on Ip. Even when Gong Er’s voice-over introduces the flashback his voice-over takes over after the end. Did she tell him this tale that we overhear as an inner monologue, or did he know by lovers’ telepathy?

In all, the U.S. version keeps the focus firmly on Ip, while building the film toward revelation of the love he might have shared with Gong Er. Here we get a line that comes at the start of the Chinese and European version:

I lived through dynastic times, the early republic, warlords, Japanese invasion, and civil war. Finally I came to Hong Kong. What kept me going was the martial arts code of honor.

Arriving at the end of the film, the line takes on a summarizing resonance. It places the episodes we’ve seen in that larger view Ip urges others to take. It comes as a lesson learned rather than a given truth that the film will illustrate.

A martial arts mosaic

Here’s another analogy. At the level of style, Wong is assembling each film out of bits that can be reconfigured on another occasion. Looked at shot by shot, The Grandmaster becomes a sort of mosaic.

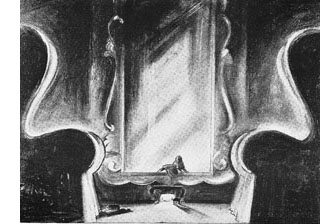

By now everyone is familiar with Wong’s late decorative look: out-of-focus foregrounds partially blocking the action, trembling reflections in mirrors and water, wisps and curls of smoke, luxuriant costumes and sets, ripe chiaroscuro lighting. After experimenting with casual handheld shooting in Chungking Express and grotesque wide angles in Fallen Angels, he settled on something more traditionally sumptuous in Happy Together and subsequent films.

He could be our von Sternberg, were it not for his nervous pace, his habit of teasingly chopping off his pretty shots. Despite his mood-drenched frames, he betrays almost no interest in staging conversations in complex ways. Wong is, in sum, a very cutting-centered director.

The Grandmaster is virtually a textbook in constructive editing. Many scenes simply omit establishing shots and give us a volley of close-ups of characters speaking or looking from fixed positions.

The Golden Pavilion brothel is a warren of windows, which lets various characters peer out at the action from undefined areas. In the Hong Kong version, after Ip has defeated Master Gong, he looks to frame right. Cut to Gong Er, who has been watching the match from some unspecified point. She bolts out frame right, and then we cut to Jiang, her guardian. Initially he seems to be watching Ip, but he seems then to see Er leave, because he turns right to rush out. Then we cut back to Ip, who apparently follows their progression by shifting his glance.

At no point do we get shots that include all these characters, or even two of them, in the same frame.

Not only do we get lots of close-ups, but they’re frequently filmed from a slightly high angle. This gives the style a consistency across scenes; the fragmentation might be more jarring if people were shot from many different angles.

The intimate high-angle is given special poignancy when we see Gong Er upside down, drifting in her opium reverie and gradually covered by a dissolve to the snowy Northeast country of her childhood.

When we do get establishing shots, they are few and not always consistent, as in the scenes taking place in the Golden Pavilion brothel. Here scenes melt into one another, with little demarcation of separate points of time and often little sense that the fights are taking place in front of witnesses. Longer shots are so rare that Wong can save their impact for frozen tableaux, as in the ceremonial moments when Ip faces Master Gong (below) and, as a parallel, Gong Er (at top). And even these aren’t really establishing the place of all the onlookers.

Sometimes the establishing shots don’t establish. You have to look quick to see the “master” framing below as telling us much about the confrontation of Jiang and Gong Er after she has fled from her father’s bout with Ip.

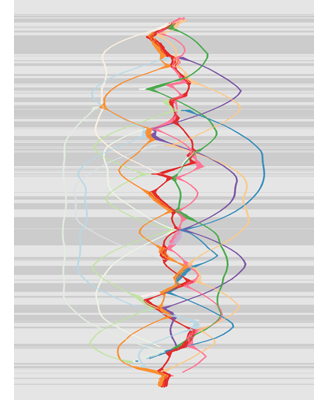

Wong’s cutting pace has picked up as well. In the Mood for Love has fewer than 500 shots, but 2046 has nearly 900 and the U.S. theatrical cut of My Blueberry Nights has over 1200. The Grandmaster goes far beyond its predecessors, offering over 2500 shots in the long version and about 2000 in the U.S. release. This puts his average shot length into the 3-4 second range. Lest we think that the speedup is due to the action sequences, the swordplay-filled Ashes of Time Redux contains only about 850 shots.

The fragmentation of Wong’s visual style partly reflects his production methods. Complicated camera movements and ensemble staging would demand that he prepare scenes in detail and work out the staging. But the actors never see a script and don’t rehearse. Better, Wong evidently thinks, to position actors standing or sitting, grab lots of shots, and fit it all together after you’ve figured out a story line.

Given this approach, the transition between one shot and another doesn’t have to be very precise. Instead of “continuity” between shots, many Wong scenes have what you might call concealed discontinuity. He will cut from a momentarily blocked image (as the camera coasts around the set) to another part of the scene. He will insert a prop, or a shot that tilts up from an actor’s waist or hips. Snippets of shots can be dropped into a scene, and even if their exact story position is uncertain, we get the point on the fly. We become used to laconic storytelling: little scene-setting, brief sequences, and ellipses within the scenes.

Once scenes feature many skipped-over actions, Wong doesn’t need to shoot linking shots. To put it in fancy terms, we come to accept elliptical cutting as an intrinsic norm, not just between scenes but within them. It would be hard to tell if something is missing—especially if the soundtrack creates some cohesion. You can always use voice-over or music to stitch together a fairly disjointed stretch of shots.

More weirdly, a cutaway that is used in one scene can be recycled in a later one in the same set. For example, the old master Rui who tests Ip’s ability to handle Xangyi technique is seen peering through a window in the brothel when Ip confronts Master Gong. A very similar shot, though with different lighting, appears when he watches the revenge match between Ip and Gong Er.

The effect isn’t unlike that in some Soviet silent films, in which shots seen earlier are recruited for fresh duties in a new scene.

Again, an intrinsic norm kicks in, and we take pretty much what we’re given. For the same reason, I think, Wong doesn’t give us many over-the-shoulder shots, as they specify spatial relations a little more than he wants. Likewise, his decentered close-ups, which don’t let an actor’s glance fill the empty area of the frame, may enhance our sense of a loosely defined story space. Wong had experimented with this in his earlier films, but the wider anamorphic ratio of 2046 and My Blueberry Nights (below) seems to have made it more attractive to him. I think that the absence of master shots makes this off-balance framing especially prominent in The Grandmaster.

This mosaic patterning gives Wong’s films a distinctive texture, and it provides storytelling advantages. The laconic cutting can permit crisp, rapid narration; no need to waste time with establishing shots and images of people entering or leaving buildings. Scenes can be astonishingly short. Even in the “full” version of The Grandmaster, many scenes last less than a minute. At the same time, the fragmentation leads naturally to the lyrical music montages that Wong is fond of. A moment can be expanded through a string of shots, enhanced by slow motion or ramping.

What gives Wong flexibility in assembly also permits him to build different versions for different markets. Because every shot can be connected to others in a variety of ways, he has plenty of leeway for trimming or adding, throwing shots out or adding some in. This is indeed what we find in the various versions, where some scenes are reduced in their duration and others are extended. For example, in the U. S. version, Gong Er’s recollection of her challenge to Ma is introduced with several shots of her drifting across her apartment and onto the building’s flat rooftop. These aren’t in the other versions, but they are easy to add to a scene that already contains fairly vague spatial continuity. In all, Wong’s patchwork coverage of scenes gives him more freedom in reworking the film than conventional continuity would.

Those who can, teach

I argue in Planet Hong Kong that despite his references to intellectual topics, Wong is a filmmaker rooted in popular culture. He exploits star images, pop songs, and especially Hong Kong movie genres. He has appropriated the romantic comedy, the crime movie, the tragic-Triad gangster saga, the swordplay film, and above all the melodrama. Of course he revises the conventions he seizes upon, but his crossover inclinations make his films enjoyable to people who wouldn’t sit through Antonioni or Tarr. This is no less true of The Grandmaster, at once kung-fu movie, historical biopic, and muted love triangle.

Wong eagerly embraces the staples of the martial arts picture. The variations of speed, from slow-motion to ramping and jittery movement, were there in his earlier work, but now they join the great tradition of kinetic action. The variety of angles, the dust billowing when someone is whacked, the rapid track-ins to poised combat stances, the magnified whooshes and smacks, the fighters hurled through windows, the kicks that bash brick walls and loosen iron bolts, the fights in rain and snow recalling Kurosawa—we’ve been here before.

Admittedly, Wong rubs his characteristic gloss into the visuals. Classic kung-fu films of the 1970s were fast-cut, but they usually featured long shots from many angles, with occasional cut-ins to close views to accentuate certain moments. 1980s directors like Yuen Kwai broke down the action still further, but the inserts of hands, faces, feet, and props were instantly legible and spatially continuous. These fast shots disassembled the fight into crisp details. (Examples are here and here.)

In The Grandmaster, Wong steers a course between precise articulation of certain moments and a loose, sketchy piling up of gestures. Shallow-focus close-ups of hammering fists and pivoting bodies offer a fusillade of sensuous appeals. Some passages have a nearly abstract flow, but impressionistic blurs and smears are halted with a snap by a highly readable establishing shot, abrupt moments of stasis, or hypersharp slowed motion. To scrutinize the film’s distinctive style properly, we’d have to work with a 35mm print (the gauge in which most of it was shot) and go frame by frame.

Despite the polished surface, Wong’s core drama respects basic conventions. The plot rests upon the rivalry among schools, the demand to synthesize and reconcile warring combat styles, the calmness of true masters versus the heedless arrogance of street fighters, and the secret techniques that settle a fight. In the moment that Master Wong throws out Ma San as a renegade, his use of his supreme move, “The Old Monkey Hangs Up His Badge,” is barely glimpsed in the film’s most impressionistic fight. The power of this family legacy is reaffirmed when Gong Er applies it to win the fight with Ma San at the railway station.

As in classic kung-fu movies, combats are characterizing. The crushing-fist technique of Xingyi deployed by Ma San fits his personality, while Gong Er employs the graceful but deadly Bagua (usually transliterated as Pa Kua). Their styles encapsulate the two sides of old Gong’s legacy, for he was able to merge the two styles (as indeed they were merged by many practitioners). Wing Chun, by contrast, is chiefly a self-defense school. It favors deflecting an onslaught of blows with palm, fist, leg, and forearm movements that are also attacks; the fighter keeps blocking until a space opens up for a decisive punch or kick. The simplicity, resourcefulness, and modesty of Wing Chun defines Ip as a man.

More broadly, the combats contrast the sadistic fury of Ma San and Razor with the relaxed confidence of old Gong and Ip. The first two grandmasters are arrogant bullies, while Gong and Ip maintain the tradition of kung-fu as a repository of decency, dignity, and wisdom.

Gong Er is caught in the middle. She is from the start characterized as willful (part of Zhang Ziyi’s star persona since Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) and too conscious of the martial-arts hierarchy. Old Gong considers Ip’s victory over him an inevitable passing of authority to the young, but Gong Er is bent on regaining the clan’s status. Defeating Ip with the 64 Hands technique of Bagua confirms her in her narrow sense of tradition and honor. But when a skirmish with Ma San kills her father and he usurps her place in the household, she refuses to follow the path old Gong marked out for her: marriage, children, and medical career.

The drive for revenge and justice fueling many classic martial arts films is here focused around Gong Er’s tragic dilemma. To uphold the family’s repute, she must destroy the tradition that her father created. Her plot line, unusually for a Wong film, actually thrusts forward dynamically. Her desires and goals sharpen into a conflict between two forms of duty: to her father’s wishes and to his historic legacy. Had she been born a boy, she reflects, all would have been easier, presumably because she would have inherited the tradition that Ma seizes by force. As it is, they split the heritage: Ma San knows Xingyi, she knows Bagua. The battle on the train platform presents a clash of the two techniques that Master Gong so proudly synthesized. They will never be reunited.

There’s a satisfaction in seeing Gong Er use her father’s decisive strike to vanquish Ma San, and she keeps part of her pledge by fulfilling his request that she become a doctor. Yet it’s a hollow victory. Her decision to disobey her father in the name of righteousness eventually comes to nothing. History intervenes and she winds up fleeing to Hong Kong as Ip has. Sworn never to marry or teach kung-fu, Gong Er dies, and her father’s beautiful variant of the 64 Hands technique dies with her.

But not the tradition of honor and teaching her father represented. In a crucial passage early on, old Gong announces his pride in uniting Bagua and Xinyi, and he wishes he were able to bring Southern martial arts to China. Ip, however, reminds him that the world is bigger; why stop with China? When Gong Er’s Bagua defeats Ip’s Wing Chun, she upbraids him in similar terms: he needs to widen his vision to encompass what the 64 Hands can do.

Fleeing the civil war, Ip carries his experience to a martial arts culture quite different from Foshan’s. From the luxurious brothel where martial artists gather to spar and honor their elders, Ip is brought to Tai Nan Street in Hong Kong. There rows of schools beg for customers, lion dancers brawl, and ruffians splash out money for some quick lessons. Ip’s resolute purity of spirit sets him apart from this shabby milieu. By the end of the film, having encountered other schools and styles and incorporating some into his repertoire, Ip carries the entire tradition of Chinese kung-fu to the world. His grinning young pupil would be known as Bruce Lee.

The button and the box

“I was lucky to meet you in my prime,” Gong Er tells Ip during their last meeting in Hong Kong. Her remark points two ways, toward their trials in combat but also toward the love that might have been. To the kung-fu genre Wong brings his characteristic register of languorous melodrama with its missed opportunities and lingering reflection on what might have been.

As sometimes happens in Wong’s films, love tokens are on display. When the Japanese invasion prevents Ip from visiting Gong Er, he sells his heavy coat to get money to feed his family, but he tears off one button to keep as a reminder. In Hong Kong he obliges Er to take it. At their last meeting, she returns the button to him, but after her death she reciprocates his gift by giving him the gilded box that holds the ashes of her hair.

Significantly, the Chinese version ends not with Ip’s success as a teacher but with images of the Buddhist temple where Gong Er made her pledge. This epilogue is at once a recollection of her tragic choice and an echo of her father. Throughout the film, the martial arts tradition is identified with fire: Gong’s brother’s cookstove, his balletic offering of a match for Ip’s cigarette, Gong Er’s burning of her lock of hair (above). The motif becomes crucial when Gong Er takes the lamp flickering beneath the Buddha to be a sign of her father’s permission to pursue Ma San. Now, in the shots that conclude the film, many lamps and candles burn under many Buddhas. We’re reminded of the monastic source of Shaolin kung-fu and the fact that Ip is the man who, as old Gong urged, will “keep the light burning.”

The final temple shots aren’t in the later versions, and the U. S. cut drastically compresses the scene of her first visit to the temple, omitting the crucial details of the lamp as a sign. Other differences play up the romance element more strongly. In the Chinese version, Ip’s childhood is covered in the summary montage at the start, and Gong Er’s isn’t shown at all. The European and American versions build a stronger link between the two through parallels. In her opium flashback, Gong Er is shown learning the Bagua technique by spying on her father; soon he is training her. These glimpses of girlhood are intercut with her doing sets in the snow. Soon afterward, we get Ip’s flashback to his boyhood when he was accepted as a student by Master Chan Wah-shun. The two sequences create a sort of secret bond between the quasi-lovers.

More generally, the American version highlights the muffled romance between Ip and Gong Er. Their exchange of letters now includes fantasy inserts of him visiting her father’s compound and the two practicing in a parlor. It’s suggested that his wife is aware of his attraction to Er and gives him permission to embark on the visit that is blocked by the war. After the war and a string of scenes showing Ip and other martial artists marooned in Hong Kong, the romance returns. Ip visits Gong Er and catches up on her doings during last decade.

A new romance seems even likelier because of the way Wong has repositioned Ip’s realization that he and his wife won’t be reunited. In the Chinese and European releases, this comes very late, after Gong Er’s death. It marks his admission that he has no chance to return home, that he can only press forward. But the U.S. version slots in this sequence earlier, holding out the possibility of a romantic liaison between Ip and Er. This prospect is consonant with the version’s more prolonged lead-in to her flashback to 1940, which includes her bodyguard Jiang telling her that her father would approve of her marriage to Ip. She then goes out onto the terrace, clasping the button, and, as we see shots of Ip intercut with shots of her, we hear her narration: “Mr. Ip, it was ten years ago….” Is it a displaced passage of dialogue, shifted from her telling him the story earlier? Or is it an internal monologue addressed to him, as if by telepathy? This poetic ambivalence isn’t there in the earlier versions.

What is there in all versions is the reiterated parallel between martial artistry and affairs of the heart. After their bout in the brothel, seeing the 64 Hands again becomes Ip’s shorthand for seeing Gong Er again. Their quietly flirtatious exchange of letters sets up a rematch that’s also a rendezvous. Another link between love and kung-fu comes with Master Gong’s advice. “Better to go forward than stay in place” becomes Gong Er’s watchword in fighting for her patrimony and vowing to stay celibate. But she also recalls the admonition her father addressed to Ma San: “Kung fu isn’t just charging forward. Look behind you as well.” Ma San, who says he collaborated with the Japanese because good warriors adjust to the moment, failed to look back to Master Gong’s precepts of modesty and upright conduct. In Hong Kong, Gong Er discovers the emotional dimension of her father’s lesson. Having gone on as far as she can (“a road I won’t see to the end”), she can only look back at what might have been—her love for Ip Man.

In a fulfillment of her father’s advice to look beyond the mountains, she has “seen the world. Sadly, I can’t pass on what I know.” Ip can. As a teacher like old Gong, he advances resolutely into the future. Yet he still longs to see the 64 Hands technique one more time. The Old Monkey move, Master Gong says, involves “looking back in reflection.” Only Wong Kar-wai would turn advice about combat tactics into an admonition to preserve the memory of unconsummated love.

Thanks to Li Cheuk-to, Tony Rayns, Ben Brewster, Lea Jacobs, and Kristin for information and ideas about The Grandmaster. A special thanks to Zhang Junyi for his enthusiastic help with Chinese-language sources.

Both the European and American versions of The Grandmaster feature a credit cookie lasting about a minute in which Ip, on a stylized staircase, leads us through a flurry of fights and then cocks an eye at the camera: “What’s your style?” It’s probably too knowing a parallel between style-conscious Wong and Ip, but its break with the noble and poignant tone of the main ending is pretty typical of Hong Kong cinema’s insouciant storytelling.

A revealing glimpse into Wong’s working methods is provided by his cinematographer. Justin Chang’s Variety interview with Wong is likewise informative. Wong talks about shooting on film here, remarking that he knew it was time to wrap when Fuji couldn’t supply any more 35mm stock. There are many sharp reviews of the film, but the one by Kozo here is one of the most nuanced. He sees the film as opening up new paths in Wong’s development.

Arguing that the U. S. cut ruins the film, David Ehrlich provides a very helpful and detailed list of the differences between the Hong Kong Grandmaster and the U. S. release. The Chinese version (all-region, with good English subtitles) may be ordered from yesasia in either Blu-ray or standard DVD. The European version I worked from is the French one, available here as a typically flashy Wong package.

The other Ip Man films are quite different and heavily fictionalized, but at least the first three are worth watching as updates of long-standing martial-arts genre conventions. They include stirring sequences of GOFRBSKF (Good Old-Fashioned Righteous Butt-Stomping Kung-Fu). Herman Yau’s Ip Man: The Legend Is Born (2010) has a nifty secene in which an old man instructively thrashes the young Ip in a cramped pharmacy. The pharmacist is played by Ip Chun, son of the real Ip Man and president of the Hong Kong Wing Chun association. Yau’s film also contains a brief passage of sparring between legends Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao. According to this story, the Ip Man cycle has led to booming enrollment in Wing Chun schools.

Back to Wong Kar-wai: The Hong Kong International Film Festival always runs a retrospective on one director or star, and this year the attention fell on Andrew Lau Wai-Kung. Known principally as the director of the Infernal Affairs trilogy, he began his career as a cinematographer. The long interview in the program’s book, Filmmaker in Focus: Andrew Lau, reveals a lot of material about Hong Kong industry practices from the 1980s onward. Wong fans will be especially interested in what he has to say about filming As Tears Go By. (It’s not usually mentioned that Lau also shot a great deal of Chungking Express before Chris Doyle replaced him.) Filmmaker in Focus: Andrew Lau is available from the publications page of HKIFF. Thanks to Li Cheuk-to for his assistance–and for his correction of a translation!

Some of the ideas I float in this entry are developed at greater length in the revised edition of Planet Hong Kong.

P.S. 23 September 2013, later: Today it was announced that The Grandmaster will be Hong Kong’s submission for the Academy Award for Foreign-Language Film. But which version?

P.P.S. 23 September 2013, still later: Li Cheuk-to writes to tell me that the version submitted for the Oscars is the U.S. version, which has played seven times in Hong Kong in order to qualify.

P.P.P.S 18 October: Harvey Weinstein talks about the changes in the US version. “At the end of the day, who gives a shit?”

Harry Potter treated with gravity

Kristin here:

Going into the summer movie season this year, I wasn’t particularly excited about most of the upcoming films. I was looking forward to Monsters University, which I thoroughly enjoyed, though it didn’t return to the dazzling levels of Pixar’s films before Cars 2. Right now I’m assembling my viewing list from the impressive array of offerings at the Vancouver International Film Festival. (The new Oliveira! Godard in 3D! Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s long-awaited return to filmmaking!)

But I’m also aware that during the festival, another film that I’m really excited to see will be released in North America: Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity. I didn’t see the 17-minute opening shot shown at Comic-Con, but I watched one of the trailers, and it was the most exciting new piece of filmmaking I’ve seen this year. If you haven’t seen one of the four trailers, you can watch them on Warner Bros.’s site, or on any number of video and infotainment sites. The one called “Drifting” reminded me of Michael Snow’s brilliant Central Region, but with narrative, with the earth and stars spinning past a close-up of Sandra Bullock as the marooned, panicky astronaut protagonist.

Unfortunately a still frame conveys almost nothing of the dazzling effect of this image. You’ll just have to follow the link above and look for yourself.

Judging by the ecstatic reviews and descriptions of audience responses that came out after Gravity was screened as the opening-night gala at the Venice Film Festival, the movie lives up to the expectations generated by the clip and trailers. One of the most insightful reviews is by Todd McCarthy, who combines giddy enthusiasm (mentioning twice that people will want to see the film repeatedly) with some solid analytical comments on the soundtrack, camerawork, and special effects. After Cuarón screened the film for James Cameron, the latter enthused: “I was stunned, absolutely floored. I think it’s the best space photography ever done, I think it’s the best space film ever done, and it’s the movie I’ve been hungry to see for an awful long time.” Indiewire’s Steve Greene has compiled a selections of excerpts from reviews from the Venice opening.

Cuarón’s previous film had been Children of Men, released way back in 2006. After such a gap, authors of articles and reviews have felt the need to summarize his career briefly. Most frequently they mention Children of Men and the 2001 Mexican comedy Y tu mamá también, which was a breakthrough film for the director. Less frequently there is a reference to Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) and A Little Princess (1995).

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in Cuarón’s career

Living paintings in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azakaban

As that line-up of titles suggests, Cuarón has had a career that makes him difficult to characterize. Although he is perceived as a Mexican director, he has done relatively little work there. Apart from shorts and TV projects, his Mexican features consist only of Love in the Time of Hysteria (Sólo con tu pareja, 1991) and Y tu mamá también. He’s also perceived as an art-film director. Variety′s cover story on Gravity was entitled “An Auteur’s Re-entry” in the September 3 print edition (though it was “Alfonso Cuaron Returns to the Bigscreen after Seven Years with ‘Gravity’ online). This impression obviously arose from the success of Y tu mamá también (distributed in the USA by Good Machine, now Focus Features) but also from the fact that the grim Children of Men was a financial flop and succès d’estime. Yet Children was produced and distributed within the Hollywood mainstream by Universal.

Instead of pursuing his career in Mexico, Cuarón headed for Hollywood immediately after his first feature. He described this career move in a 2006 interview:

After coming up the ranks as a cable operator on a movie set and an assistant director, he made his first feature, “Sólo con tu pareja,” in 1991, and it won several awards at the Toronto Film Festival. However, the Mexican Film Commission, which had subsidized it, wasn’t happy with the movie.

“I basically burned my bridges with the commission,” says Cuarón, who moved to Los Angeles with no contract to do another film. Director-producer Sydney Pollack gave him a chance to shoot an episode on the cable TV series, “Fallen Angels.”

“Tom Cruise had directed one episode and Tom Hanks another. But mine was the one that won a cable award,” Cuarón says. “It was one of those things that led to the next.”

That turned out to be the sublime children’s movie “A Little Princess.”

“I never watch my movies after I’m done with them, but in my memory that’s the one I love the most,” he says.

Cuarón’s next experience directing a modern-day version of “Great Expectations” [1998] starring Gwyneth Paltrow and Ethan Hawke, wasn’t so great.

“My instinct always told me not to do it, and I ended up doing it anyway,” he says. “So I learned to trust my instinct.”

Also in this interview, Cuarón describes himself as lucky in his Hollywood work:

That a major studio (Universal) was willing to underwrite such a downbeat story [as Children of Men] is a credit to Cuarón’s reputation. Unlike many foreign directors used to having enormous latitude in their native countries, Cuarón has learned to work within the Hollywood system.

“There is a tendency to see Hollywood like Darth Vader trying to destroy filmmakers,” he says. “And I’m sure that’s sometimes true. I have been very lucky to be able to create my own stuff without studio interference.”

The perception of Cuarón as an art-film director has perhaps led to a tendency to dismiss his one venture into the Harry Potter series as an aberration. In his excellent analysis of the long takes in Children of Men (which focuses on the fact that they were created by digitally blending multiple takes), James Udden remarks on how, after first using long takes in Y tu mamá también, “Next, Cuaron takes a ‘step back’ in a sense with Prisoner of Azkaban, paying yet more ‘dues’ to the system.” Justin Chang’s brief but informative survey of long takes in Cuarón’s work does mention that the technique “even reared its head in 2004’s ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban,’ in which the director boldly imprinted his personality onto one of Hollywood’s most successfull–and most risk-averse–franchises,” though he does not mention how the technique “reared its head.”

Yet Cuarón evidently loved his experience working on Prisoner of Azkaban. The interview just quoted was one of several in 2006 where he expressed keen interest in making another film in the series: “If I’m invited, I would be very tempted to direct it. The idea of revisiting that beautiful universe is irresistible [….] Everything that happens around a J. K. Rowling creation is enveloped in this beautiful, beneficial energy.” Maybe he will have a chance to work on a Rowling film again, given the recent announcement that she will write the script for a franchise-starter for a new film series based in her wizarding world.

Setting aside Cuarón’s feelings about his experience making the film, we should not dismiss it as a minor part of his career, something he supposedly made so that he would be able to make other, more personal projects. For a start, it does have a style distinctly different from the other Harry Potter films. It’s not always recognizable as a Cuarón style, but then, Cuarón’s films are so different from each other that that is hardly surprising. Udden points out that while Children of Men has an average shot length of slightly over sixteen seconds, Prisoner of Azkaban′s ASL is about 5.5 seconds. Still, it contains three long takes, each of considerable interest. Moreover, the introduction to cutting-edge CGI would leave Cuarón with valuable experience that he could apply to his two subsequent features.

Prisoner of Azkaban has a reputation as one of the best, if not the best, of the Harry Potter films. Its quality is not solely due to Cuarón’s direction. The book is arguably also the best of Rowling’s series. While the first two books (Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets) are pleasant, entertaining children’s stories, Prisoner of Azkaban marks a leap in the complexity and depth of the plotting. It adds two major new characters, the sympathetic professor (and werewolf) Remius Lupin and the apparently threatening Sirius Black, who turns out to be Harry’s parents’ best friend and his godfather. It also adds a third character, the dotty Prof. Trelawney, who seems just to offer a source of comedy but will eventually prove to have affected Harry’s life in unsuspected ways.

New villains also appear, notably the soul-sucking Dementors and the literal and figurative rat, Peter Pettigrew, another old friend turned traitor who has become Voldemort’s main helper. Lupin introduces the technique of casting a “patronus,” a protective figure of light that repels the Dementors–something that will continue to be crucial for the rest of the series. Finally, there is the ingenious episode of the time-turner, a device Hermione has been employing to take multiple classes at once but which she ultimately uses to allow her and Harry to go back in time and manipulate a series of tragic events and make them end happily. This lengthy scene, one of the high points of Rowling’s series, is even better in the film, where we can see the doubled characters on the screen.

Apart from drawing on the book’s strengths, the film also has the advantage of being the one that replaced Richard Harris with Michael Gambon as Dumbledore. Apparently some viewers were fond of Harris’ portrayal, but the casting seems to me a real mistake and no kindness to an actor clearly in failing health. I found him disturbingly feeble, stiff in his movements and expressions, and barely able to get a whole line out without gasping for breath. How the producers thought he could last through the series is a mystery, and Gambon’s livelier and funnier performance came as a relief.

Prisoner of Azkaban also quickly gained a reputation as being much darker in tone than the two films that preceded it. I doubt there was a single reviewer who failed to make this claim. The Washington Post’s critic called it “everything the first two films were not: complex, frightening, nuanced.” For Roger Ebert, “Harry’s world has grown a little darker and more menacing.” In a later survey of the first four Harry Potter directors, Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott wrote of Prisoner of Azkaban, “the tone and color palette have shifted, the bright, flat lighting giving way to a somber and dangerous feel, evocative of horror films.”

Perhaps such comments had something to do with the fact that Prisoner of Azkaban earned less at the box office than any other film in the series: a mere $797 million. (The second lowest earner, Chamber of Secrets, made $879 million; the highest, Death Hallows Part 2, $1.3 billion.) It’s hard to believe that fewer people would go to the film based on a change of directors. How many, after all, would be likely to know who Cuarón was? More likely parents kept younger children away for fear that the action would be too intense.

The book version of Prisoner of Azkaban also takes a much darker turn. If that was the reason for the downturn, it didn’t last long. The trend toward darker, scarier content continued through the later books, with the return of Voldemort in the fourth and the deaths of major characters in each subsequent book. Similarly, the later films are distinctly more grisly and frightening than Prisoner of Azkaban. None of this kept people from buying books and movie tickets.

One might assume that studio executives decided on Cuarón as an appropriate director for a darker entry in the series, but he had not yet gained a reputation for grim subject matter. That came with Children of Men. In fact, Cuarón was not the first or even second choice as the film’s director. A retrospective article on Den of Geek! gives this account:

The studio’s choices included Guillermo del Toro, who baulked at how the film was “so bright and happy and full of light”, and Marc Forster, who didn’t want to direct children again so soon after making Finding Neverland.

It came down to a final short-list of Kenneth Branagh (who had co-starred in the previous instalment as Gilderoy Lockhart), Alfonso Cuarón (A Little Princess) and Callie Khouri (Divine Secrets Of The Ya-Ya Sisterhood and screenwriter of Thelma And Louise). Eventually, Cuarón was appointed, and the director is largely credited with energising the series.

Let’s examine some of what Cuarón brought to Harry Potter by looking at his signature device, long takes.

Three long takes and some flashy effects

Unlike in Children of Men, the long takes in Prisoner of Azkaban are not used primarily for action scenes. Unlike in more conventional Hollywood films, they are not used at the opening as a flashy way of presenting exposition. Rather, they function to emphasize transitional points in the plot and to create motivic parallels. Not surprisingly for Cuarón, all involve camera movements. Two of the three involve conversations, one with an impressive but not flashy tracking movement to follow the characters, the other with a more subtle, slow push-in and out.

The first and lengthiest of the long takes comes in the Leaky Cauldron inn when Harry encounters the Weasley family and Mr. Weasley takes him aside to warn him about Sirius Black’s escape from Azkaban prison. It lasts for one minute and 53 seconds.

The setting is bustling, and the camera movement serves in part to gradually pull attention away from the crowded dining room and to focus on the conversation. The shot opens on the busy table, with a large tea kettle floating on its own through the air. (In Prisoner of Azkaban, Cuarón frequently uses this tactic of having objects floating in the foreground to suggest a magical environment; he will repeat the device in Gravity to depict weightlessness in space). Mrs. Weasley effusively greets Harry:

Mr. Weasley asks to have a word with the boy, and they move toward a squared-off opening near the back of the set. A wanted poster for Black, visible to the right of center from the opening of the shot, becomes more prominent at the frame edge. Since photographs in this magical world move, we cannot help but notice it:

The camera tracks past the poster through a second opening closer to the camera and stops once the characters are centered. Mr. Weasley tells Harry about Black, and the camera moves back to accommodate them when they come forward to look at the poster:

As they continue to talk, the camera again moves backward as Mr. Weasley steers Harry to a third opening into the main dining room. They pause beside a second poster of Black, and Mr. Weasley explains that Black had betrayed Harry’s parents to Voldemort, who had killed them and tried to kill him. As a man in a bowler sits at the table near them, Mr. Weasley again guides Harry into a more private area:

He says Black is going to try and kill Harry and urges Harry not to go looking for him. The shot ends on a push in toward Harry, who replies, “Mr. Weasley, why would I go looking for someone who wants to kill me?” and the scene ends.

This moment marks a crucial change in the narrative tone. The film started with two comic scenes: Harry’s use of magic to inflate his obnoxious Aunt Marge into a human blimp and then the antics of the fantastical Knight Bus that rescues Harry and transports him to the Leaky Cauldron. Now for the first time the theme of grave danger is introduced, with the insane-looking Black screaming silently in the wanted poster. A darker storyline takes over, though there are many moments of humor to come. This conversation leads into the scene on the train to Hogwarts, which, for the first time in the series, has a heavy rainfall occurring throughout. During this scene the first Dementor appears, and Lupin explains what Dementors are.

The second long take (one minute and thirty seconds) comes in a much quieter scene at Hogwarts. Harry has been unable to accompany the other students on a day’s outing to Hogsmeade, the local village, and he is depressed and lonely. He has a conversation with Lupin, set on a long elevated bridge that was added to the Hogwarts setting for this film. The scene begins with an extreme long shot tracking slowly toward the bridge as Harry discusses his fear of Dementors with Lupin, followed by a cut-in to them:

The camera moves in slowly as Lupin turns away and recalls his friendship with Harry’s mother. As he says, “Well, your father James, on the other hand, he … he had a certain, shall we say, talent for trouble,” Harry smiles:

Lupin walks back to Harry, concluding, “A talent, rumor has it, he passed on to you. You’re more like them than you know, Harry. In time you’ll come to see just how much”:

The scene ends with a cut to a shot of the bridge from the original distant framing:

The two scenes are parallel but contrasting, as Harry receives information from two father figures. Initially he speaks to Mr. Weasley, the head of a large, boisterous family that has semi-adopted Harry; we are reminded of them (including Ginny, whom Harry will eventually marry) at intervals in the background of the Leaky Cauldron long take. The two rooms are divided by a series of square openings in a thick wall, which the pair move through as Mr. Weasley prepares to deliver threatening news. The melancholy Lupin, on the other hand, has no family, and here he comforts Harry in a setting with airy, intricate archways framing a vast, empty mountain vista beyond. The quiet atmosphere is appropriate, since Lupin is the first of three classmates and close friends of his dead parents that Harry meets in this film.

The film’s third long take is the only one that could be said to involve an action scene, though it is really just the prelude to a lengthy segment of the film stringing together several brief action scenes. (It is the shortest of the three long takes, at one minute and eight seconds.) This shot marks another transition, introducing the film’s climax. Everything has just gone wrong. Gamekeeper Hagrid’s pet hippogriff Buckbeak has been executed as too dangerous to be around the students. Sirius, whom the children now know to be innocent of the crime for which he was imprisoned, has been captured and is about to be turned over to the Dementors. Pettigrew, having been revealed as the true traitor to Harry’s parents, has escaped in rat form. In the hospital dormitory where Ron has ended up, Dumbledore hints that Hermione should use the time-turner so that she and Harry can return to the beginning of these events and try to reverse them.

The camera circles around Hermione as she turns away from Ron’s bed and pulls the time-turner on its chain from inside her jacket. She lifts it and places the chain around Harry’s neck, so that they are both wearing it:

He looks on uncomprehendingly as she twirls the time-turner to send them back to a point shortly before the scheduled execution of Buckbeak:

Startled, Harry watches rapid changes in lighting and blurred figures moving backward in fast motion as Hermione keeps track of how far they have traveled. During all this, Ron disappears from the bed at the right rear:

The camera moves in as she hides the time-turner and circles as they run out of the room:

They run along a corridor, the camera following until they turn and exit left:

The camera continues straight ahead, through the large clock wheels, and reveals the school grounds far below:

The camera moves through the glass of the clock window and tilts down to the courtyard, where Hermione and Harry emerge and run out through the doorway at the top of the screen:

Later, after the pair has accomplished their goals, a somewhat similar shot moves with them through this same courtyard and cranes up and through the clock again, joining them at the same point as they run in and away down the corridor to the hospital wing.

On a more modest scale, there is a somewhat similar technique used in Y tu mamá también. The heroine, Luisa, waits in her apartment for Tenoch and Julio to pick her up for a trip to the beach. Once they call to let her know they have arrived, she exits through the front door; the camera tracks rightward to a window and tilts down to reveal the car waiting below and pulling away from the curb as the three depart. Although not a particularly lengthy shot, it functions, as in the third one from Prisoner of Azkaban, to mark a narrative transition, in this case the end of the film’s first portion and move into the long car trip that will occupy most of the rest of the film:

This is a far simpler shot and was accomplished by moving the handheld camera through the room to an open window, sticking it through, and tilting down. The Prisoner of Azkaban “shot” was in fact an elaborate manipulation of images, with the segment where time runs in reverse around Harry and Hermione shot against a green screen; the portion going through the clock’s works and its window was done with CGI elements. (See American Cinematographer‘s article on the film for an explication of the technology involved.)

Admirers of the elaborate “camera movements” in Children of Men and Gravity, some of which were done by stitching together several elements into apparently continuous shots, might take note that Cuarón’s experiences on Prisoner of Azkaban made them possible. A 2006 interview on SFGate describes the director’s progress:

One benefit was a crash course in computer-generated visual effects. Cuarón used “maybe a shot or two in “Y Tu Mamá También”–the 2001 Mexican indie that got him an Oscar nomination for best original screenplay–and in his earlier Hollywood movies, “A Little Princess” and “Great Expectations.”

On the Harry Potter sequel, working with computer effects was “like speaking Russian,” he says. The hardest part was figuring out how to shoot an object such as a plate, knowing that later it would be substituted by some wild effect.

“The important thing was not to be shackled by these effects, to shoot as you would your normal scene. There’s a tendency I witness in movies and completely dislike in which the narrative is kind of forced because of the visual effects. You have to try to keep your character and the visual-effect character as separate as possible.”

By the time he started “Children of Men,” all of this was “like second nature.”

In a more recent (undated) interview given at the time when Gravity‘s principal photography was beginning, Cuarón stressed its connection to the things he had learned about special effects on Prisoner of Azkaban: “Well, Potter was my kindergarten and grammar school and high school and college education of visual effects. It is coming in handy with Gravity which is so, so visual-effects savvy [that] we’re inventing new technologies. Now it’s just second nature.” He also mentions that his work with David Heyman, who produced all the Harry Potter films, was what led him to invite Heyman to produce Gravity.

Apart from the CG-compiled long takes, there were effects like the hundreds of candles floating in the air above the great dining hall of Hogwarts (see top) and the living paintings crowding the walls (above left). It seems remarkable that Cuarón’s third film after his modest Mexican sex comedy could draw such high praise from James Cameron, one of the top directors of effects-heavy films, but working on a Harry Potter movie for a couple of years made that possible. And, as the frame below demonstrates, directing Quidditch matches is a good preparation for showing people drifting weightlessly in space.

The quotation from James Udden comes from his article, “Child of the Long Take: Alfonso Cuaron’s film Aesthetics in the Shadow of Globilization,” Style 43, 1 [Spring 2009]: 40. For those with access to a research library, this issue is available on ProQuest and other online archives.

Innovation by accident

DB here:

The old drama is being reenacted before our eyes, and as often happens, Harvey Weinstein plays the villain. The American release version of Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, which has cut and changed the original, is being decried as a travesty, the dilution of an artist’s original conception in the name of what somebody thinks will sell.

I take up The Grandmaster in another entry. For now, I just want to point out the archetype goes back long before Harvey came on the scene. A screenwriter or director comes up with a fresh approach to telling the story. But a producer rules it out as something the audience won’t buy, or even understand. Moral: In Hollywood, the creative force is stifled by a money person who insists on doing things as usual.

The 1940s in Hollywood was an era of narrative innovation. It gave us weird dream sequences and insane protagonists and subjective point of view and byzantine flashbacks and talking houses and complicated replays of action we thought we understood. While working on a book on this era, I’ve begun to wonder what the limits of innovation might be. What could make the boss tell the filmmaker that a particular narrative choice just went too far?

Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a bumpy production

A Letter to Three Wives (1949).

One example I found was purely anecdotal, but nifty nonetheless. In preparing the screenplay for Out of the Past (1947; aka Build My Gallows High), screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring wanted to have the story told by a deaf-mute boy. Apart from the fact that the boy plays a minor role in the opening of the film as it was finished, the idea of someone who cannot hear or speak serving as narrator proved to be something of a stretch for the time. Mainwaring reports that the idea was rejected.

That’s the kind of thing I wanted to find. Yet my searches sometimes came up with cases where the producer’s notes actually resulted in improvements. Take A Letter to Three Wives (1949), justly praised as one of the best films of the 1940s.

John Klempner’s original novella (published in 1945) and novel (1946), both titled A Letter to Five Wives, obviously involved two more couples. After some other writers had drafted versions, Vera Caspary was assigned to prepare a treatment. Probably with the input of producer Sol Siegel, she eliminated one couple. Her adaptation already contains much of what is distinctive about the movie as we have it. Instead of the many distributed flashbacks in the originals, the treatment consolidated them into three lengthy ones. At Siegel’s suggestion, Caspary brought the three women together on the boat. To Fox studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck we apparently owe the idea that one woman, Deborah, would be the primary vehicle of our sympathy and would initiate and resolve the mystery of whose husband has defected. Above all, Caspary’s treatment includes the unforgettable voice-over of the never-seen Addie Ross.

When director Joseph L. Mankiewicz saw Caspary’s final adaptation, in effect “A Letter to Four Wives,” he declared he “looked upon the Promised Land” and quickly turned it into a screenplay. After reading Mankiewicz’s screenplay, Zanuck intervened again , demanding that another wife be lopped off. Mankieiwicz called this “an almost bloodless operation.”

It’s probably irrelevant that A Letter to Three Wives won that year’s Academy Awards for best screenplay and best direction. Even if it hadn’t been honored, after reading the original tales and Caspary’s adaptation, I have to conclude that the film is the best version of the lot. I suppose it partly goes to show the old rule that bad or so-so books can make very good movies. (Exibit A: The Birth of a Nation; Exhibit B: The Magnificent Ambersons; Exhibit C: The Godfather. Defense rests.) But clearly, the cuts and changes demanded by Siegel and Zanuck improved the property. The “creatives”–Klempner, Caspary, Mankiewicz–were by force majeure steered toward good results.

You can argue, though, that no written version of the film tried to be innovative, except perhaps for the device of Addie’s spectral presence. And Mankiewicz declared himself happy to make the adjustments. What about cases in which genuinely bold ideas were curtailed by the powers above? So I looked into two titles that, when released in the producers’ cuts, were denounced by their writer-directors.

Two years after Preston Sturges finished and cut his film about the discovery of ether anesthesia, Paramount producer B. G. “Buddy” DeSylva supervised and released a reedited version called The Great Moment (1944). Sturges noted of the film:

It is coming out in its present form over my dead body. The decision to cut this picture for comedy and leave out the bitter side was the beginning of my rupture with Paramount. . . The dignity, the mood, the important parts of the picture are in the ash can.

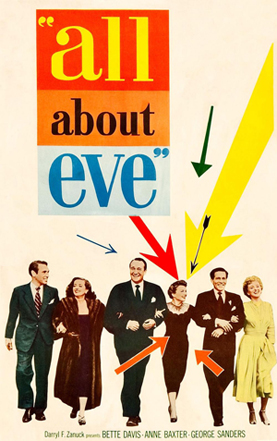

A second example is a more famous release, Twentieth Century-Fox’s All About Eve (1950). After the success of A Letter to Three Wives, Zanuck allowed Joseph L. Mankiewicz to film his three-hour screenplay as a “shooting draft.” When Zanuck saw the result, he insisted on cutting it to 138 minutes.

Throughout his life Mankiewicz was an angry man. His interviews and writings excoriate mothers, film festivals, doctors and nurses, Michelangelo Antonioni, television, the American male, theatre operators, Graham Greene, the AFI, PBS, Richard Nixon, Dennis Hopper, The Untouchables (film version), British craft unions, and other malefactors. High on the list was Darryl F. Zanuck. Long before the Cleopatra debacle, Mankiewicz was already carrying a grudge because Zanuck removed a replayed scene from All About Eve. He definitely didn’t consider that a bloodless operation.

Zanuck had final cut and he got bored with the same scene shot from different points of view.

Here, I thought, were sterling examples of creators bumping up against what was impermissible. Yet the more I looked, the more I found that the situation couldn’t be reduced to the daring director versus the philistine producer. I was forced to consider the possibility that the producers’ changes yielded not timid conformity but instead some unpredictable results–things that were themselves novel, in intriguing ways. The suits hadn’t intended to do something bold, yet in revising and patching up the films shot by two venturesome directors, they actually found themselves pulled in new directions.

Call it inadvertent innovation. Not surprisingly (this is the 1940s), it involved flashbacks.

Which great moment?

Kitty Foyle (1940).

By the early 1940s, movie flashbacks adhered to several conventions that we still recognize. Typically, we’re given a situation, the narrative Now, in which a character is recounting or simply remembering past events. We then move to those events, a shift often signaled by a track-in, a musical cue, a dissolve or other optical effect, and/or sounds from the next sequence mingling with the spoken transition. We may hear the voice-over remarks of the lead-in character at times during the action we see. Once the flashback action is complete, we return to the present, with the character who launched the flashback finishing the testimony or closing off the memory. And if the film includes several flashbacks, they are typically presented chronologically, so that the earliest events from the past are shown before later ones.

Kitty Foyle (1940) offers a clear example. In the present, Kitty recalls her romances. As they develop, we return to the present at key moments to gauge her reactions. For the sake of clarity, the romances themselves are shown to us in 1-2-3 order, tracing the events that lead up to the crisis that launched her memory journey.

Not all flashbacks respect chronology, though. Citizen Kane’s first flashback traces Kane’s career as the banker Thatcher knew it. His recollections show us Kane as a child, a young man, and then a much older man forced to sell his newspaper empire. The next flashback, as recounted by Kane’s business manager Bernstein, takes us back to show Kane as a young man assuming control of his first newspaper. Several years before Kane, Sturges had composed a script based on similarly shuffled chronology. The Power and the Glory (1933), directed by William K. Howard, presents an old man recalling episodes in the life of tycoon Thomas Garner, and those are presented out of 1-2-3 order. (I analyze that film here.)