Archive for the 'Directors: Benning' Category

Catching up with the past: Recent DVD and Blu-ray releases

Behind the Door (1919).

Kristin here:

David and I have moved house recently, which has caused a long lag in my getting around to doing a DVD/Blu-ray roundup of recent releases. Some are not so recent anymore, but I shall call attention to them nonetheless.

Behind the Door (1919)

Our friends at Flicker Alley have been busy, as usual.

Way back in February of last year, they released Behind the Door, a notoriously grim and brutal drama of World War I that long survived only in incomplete form. Using tinting rolls from the Library of Congress, some scenes from star Hobart Bosworth’s collection, and a re-edited Russian distribution print, as well as a copy of the continuity script, the restoration by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, the Library of Congress, and Gosfilmofond approximates the original American release version fairly closely. (Two brief missing sections are filled in by photos and the texts of the original titles.) The tinting and toning, based on the Library of Congress material, is authentic and effective (see top), as is the new score by Stephen Horne.

The Russian version is included in the two-disc set, so we have one of those rare cases where it is possible to compare the foreign and domestic versions–to a degree. Most of the shots, of course, were made with a second camera, and there are inevitably differences of framings and even takes between those versions. Given that the new restoration depends heavily on the Russian print, the comparison must be made primarily on the basis of the differences in the order of the scenes and the other narrative changes made by the Russian editors.

Behind the Door tied for Best Single Release in Il Cinema Ritrovato’s DVD Awards, announced just last month. Congratulations to Flicker Alley and to other organizations we have ties to, which also won awards. The Criterion Collection tied for Best Box Set for its 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912-2012. This massive set (32 discs on Blu-ray, 43 on DVD) contains 53 films, including those by Leni Riefenstahl, Kon Ichikawa, Claude Lelouch, Carlos Saura, and Miloš Forman. Belgium’s Cinematek won Best Discovery of a Forgotten Film for its Marquis de Wavrin (1924-1937), actually a series of films shot in South America by this major anthropologist and filmmaker. German Concentration Camps Factual Survey (from the BFI and the Imperial War Museum), which David commented on last year, won Best Special Features.

Das alte Gesetz (1923)

I have a particular interest in German silent cinema of the post-World War I era, so I was happy to see Flicker Alley’s release of Ewald André Dupont’s Das alte Gesetz (“The Ancient Law”). Most people know Dupont only from his most famous and successful film, Variety (1925), known for its spectacular camera movements taken from trapezes.

Dupont had a long career, however, starting as a scriptwriter in the 1910s and becoming a director as well in 1918. Das alte Gesetz is mainly known as one of a small group of Jewish-themed films made in Germany in the period 1919-1924. More familiar to most would be Der Golem:Wie er in der Welt kam, co-directed by Paul Wegener and Carl Boese (1920) and to some, Die Gezeichneten, Carl Dreyer’s first German film (aka Love One Another, 1922). A helpful essay in the accompanying booklet by Cynthia Walk gives the political context of die Judenfrage (“the Jewish question) as it was being debated in Europe at the time.

Set in the 1860s, the film concerns Barush, the son of a rabbi in a shtetl in western Russia. He suddenly and somewhat implausibly conceives a desire to leave home and become a famous actor. Naturally his father disowns him. Joining a small traveling troupe, Barush ends up in Vienna, where an archduchess, played by Henny Porten, is impressed by his performance as Romeo and attracted to him as well. She arranges for him to join her court-theatre troupe, where he becomes a star as a classical actor.

The scenes in the shtetl (above) are done with considerable attention to authenticity and without the sort of ethnic humor that one might expect. Although Barush encounters prejudice in Europe, he does not evenually learn a lesson about assimilation and go back to his home with his tail between his legs. Far from it; his father is induced to read Shakespeare and suddenly realizes that there are indeed more things in heaven and earth than he had dreamed of in his philosophy. A happy reunion results, and Barush continues his career.

Das alte Gesetz was clearly a big-budget period piece, with several large sets. Moreover, the influence of classical Hollywood films, which began to be shown in Germany in 1921, is quite apparent. Dupont has mastered three-point lighting and analytical editing, including shot/reverse shot, as this scene between Barush and his father demonstrates.

Barush is played by Ernst Deutsch, a major actor of the day, including in Expressionist films. He’s the rabbi’s son in Der Golem as well, and he plays the bank-cashier protagonist in Karl-Heinz Martin’s From Morn to Midnight.

MOD

Flicker Alley has also developed a healthy list of manufactured-on-demand titles. Many of these are out-of-print films from the Blackhawk Collection. The 51 titles currently on the list include many silent classics, some of them difficult to see on disc otherwise, such as Lubitsch’s The Marriage Circle and Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa.

The new offerings lately have branched out somewhat to include more recent films. On September 3 of last year, the company released Alex Barrett’s London Symphony (2017) for its home-video debut. In the press release for the disc, the director describes it as “a love letter to a city, but it is also a film about life in the modern era.” As the title indicates, Barrett places his film in the city symphony genre, and its release was timed to coincide with the 90th anniversary of the premiere of Berlin: Symphony of a City. City symphonies tend to be associated with the 1920s, when the genre originated and its most famous exemplars, Berlin and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, were made. The genre has never disappeared, but Barrett has written that he chose “to make the film in a style associated with the filmmakers of the 1920s.”

For me, it captures well the style of the 1920s, and particularly Berlin. Shot in black-and-white, London Symphony falls into four movements, following a day in the life of the city–with, as in Berlin, pauses for lunch and dinner particularly dwelt upon. The opening section concentrates on buildings, and there are the inevitable juxtapositions of old and new (see bottom). Multiple cinematographers filmed the footage, but their work blends into a unified visual whole with many striking compositions.

Ruttmann injects occasional implicit political commentary, as when he juxtaposes shots of beggars in the streets with the well-fed Berliners in restaurants. Barratt concentrates on the beautiful and peaceful side of London–historic buildings, quiet parks, pleasant markets, and river scenes. The rather grubby and crowded atmosphere of, say, the West End of London is nowhere to be seen, which befits “a love letter.”

In January The Indomitable Teddy Roosevelt joined the MOD catalog. This is a reissue of a 1983 television documentary that mixes documentary footage (Roosevelt was the first president to be filmed) and staged scenes.

Edition Filmmuseum

This series continues its steady release of experimental filmmaker James Benning’s works with a sixth two-disc set (DVD only) that goes back to his earliest features, films that solidified his international reputation. The new two-disc set contains two films from the late 1970s, 11 x 14 (1977) and One Way Boogie Woogie (1978). Jim followed up the latter, a series of sixty shots of Milwaukee cityscapes, with 27 Years Later (2005), which presents the same series of locations, and One Way Boogie Woogie 2012, which further documents the changes in the filmmaker’s hometown. All three films are included in this set.

11 x 14 flirts with presenting a narrative without ever really concentrating on it. We see some of the same people at intervals, but no causal events link them, and their actions create situations rather than developing stories. Instead, the film’s shots, some quite lengthy, others brief, explore the urban and rural landscapes of Chicago and Milwaukee, as well as rural roads and fields in the surrounding area. (A familiar highway sign pointing the way to Madison is glimpsed at one point.)

For the most part the urban images concentrate on run-down areas, with motifs of travel (billboards, airplanes) and drinking (bars and more billboards) hinting at contrasting modes of escape. The shot above captures both motifs at once.

Given that Jim’s films seldom play outside festivals and museum venues, the Filmmuseum series is vital–though many of the images in these films are long or even extreme long-shots and benefit from being seen on a big screen. The last time we had a chance to do so was when RR (2007) was shown at the 2008 Vancouver International Film Festival. The Austrian Filmmuseum also published a book on Jim’s work, which David discusses here.

London Symphony (2017)

Got those death-of-film/movies/cinema blues?

Night Across the Street (2011).

DB here:

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

These squibs seemed especially damp this time around because while these guys were knocking Hollywood and/or art movies I was enjoying the Vancouver International Film Festival. If you’re willing to watch mainstream entertainments from outside Hollywood, or films that aren’t the bland arthouse fare full of stately homes and British accents, or even films that don’t chop every scene to splintery images, Dr. Bordwell has a cure in mind for you.

Had you been looking for breezy or outlandish entertainment, for example, the Dragons and Tigers wing didn’t disappoint. Helpless, from South Korea, is a thriller built around identity theft. I thought it was clumsily plotted, but it sustains curiousity through the apparently bottomless series of discoveries a man makes about his missing fiancée. Jeff Lau’s East Meets West is a Hong Kong farrago of rapid-fire gags, weird haircuts, references to old Cantopop, and nonchalantly wacko storytelling. Granted, the central idea of making the Eight Immortals of legend into modern superheroes (and one supervillain) is smothered by Scott Pilgrim-style SPFX. Still, I will watch Karen Mok Man-wai and Kenny Bee in anything, albeit for different reasons. Closer to mainstream Hollywood tastes was Nameless Gangster, in which a restless flashback structure traces the rise of a flabby brute from customs agent to top drug smuggler. Yoon Jongbin’s slickly-made film ends with an abruptness that recalls the conclusion of The Sopranos.

Of all the pop-entertainment movies I saw at VIFF, the audience favorite was doubtless Key of Life, a nifty Japanese crime comedy. An amnesiac hitman and a shambolic slacker swap identities in a cunning series of coincidences that brings on some satisfyingly menacing underworld types. Intersecting the men’s misadventures is a hyperorganized OL, or office lady, who determines to find herself a husband within a month. Everything sorts itself out, of course, with one nice wrapup saved for the middle of the closing credits. This is the kind of Japanese diversion I’ve recorded a liking for earlier (Uchoten Hotel and Happy Flight). Hampered by a wretched title, Key of Life probably won’t get US theatrical distribution, although it may make some headway on VOD. Aussie movie maven Geoff Gardner and I agreed that if we had the money, we’d buy the remake rights.

Everything new is old (again)

Tabu (2012).

Form is the new content, they say. (Too simple, but some do say it.) No surprise, then, that part of what appeals in contemporary cinema is its overt reworking of previous styles. Neo-noir is perhaps the most common current example, but ingratiating retro-stylings were on display in more rarefied forms at VIFF.

Part of the appeal is the rediscovery of the glory of the 4:3 aspect ratio. Kristin has already talked about how Pablo Larrain’s No appropriates a seedy U-matic look to tell its tale of 1970s Chilean politics. A similar pastiche effect emerged from Mine Goichi’s All Day, a short that used even grubbier video to parody Japanese family dramas. May we expect to see more VHS-looking movies? I wouldn’t mind.

Silent cinema pastiches are usually lame, as witness The Artist, which scrambles history and treats old films as oddly soft-minded. (No Hollywood drama of the late 1920s would have been built around a protagonist so feeble he tries to commit suicide twice.) Jean Dujardin, and contemporary audiences that adore his film, should catch up with Hayashi Kaizo’s To Sleep As If to Dream (1986), in which the contemporary story is played as a silent film and the rediscovered (fake) old film is accompanied by benshi commentary and music. The “forged” footage in Forgotten Silver also shows how good filmmakers can create convincing, pleasantly anachronistic imagery.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

More celebrated since its Berlin triumph (two awards) is another 4:3 exercise, Miguel Gomes’ Tabu. A vaguely 1920s prologue shows a brooding tropical explorer who has seen his ex-wife as a ghost. Then Part 1 (“Lost Paradise”) takes us to stately black and white imagery of contemporary Lisbon. It’s late in December, and Pilar is concerned about her elderly neighbor Aurora. The old woman is taken to a hospital and asks Pilar to find Aurora’s old lover, Ventura. By the time Pilar discovers him, it’s too late. After Aurora’s funeral, Ventura starts to explain how they met in Africa. Here starts Part II (“Paradise”).

Now the film becomes hypnotic. In Africa, Aurora is married to a sturdy, good-natured colonist, and she can hunt and shoot with the best of them. Ventura and his friend Mario, who’s becoming a pop crooner, are taken into the household. He and Aurora begin a torrid affair. Part II is rendered without onscreen dialogue, but not in exact mimicry of silent cinema. There is piano music, it’s true, and much of the action is carried by letters, as in a lot of silent movies. But there are no intertitles; instead, all the action is played out with the support of Ventura’s voice-over, occasionally supplemented by the young Aurora reciting letters she wrote. Moreover, Mario’s band and his singing are rendered in full lip-synch. More eerily, as Ventura explains the rise and collapse of the love affair, we get highly selective bits of noise—not everything audible in a scene, but perhaps the tinkle of glasses or a faint wind. These become the aural equivalent of glimpses.

“Paradise” gives us silent cinema not replicated, but refracted through memory and romantic longing. In a film paying homage to Murnau (a forbidden romance as in Tabu, the name Aurora recalling Sunrise), Gomes has apparently also sought to give us something like the “part-talkies” of 1928-1929. Those films had full-blown dialogue scenes (as in Part I) and other scenes containing only music and effects (Part II), relieved by synchronized musical numbers (a sequence showing Mario’s band performing by the pool). Tabu recovers something of the strangeness of those transitional films, notably Sunrise itself, while remaining highly contemporary. It knows that we can turn to tradition when we want to rekindle a romanticism that would look high-flown today.

Long live the long take

Beyond the Hills (2012).

At about 16 seconds per shot, Tabu has the same cutting rhythm as some early talkies, like The Black Watch and Hearts in Dixie. Today, as we’ve seen, the long take is increasingly the province of movies that play chiefly at festivals. All other things being equal, a movie with around 1200 shots, like the very popular Danish import The Hunt, will be an easier sell on the arthouse circuit than, say, Beyond the Hills, with only about 110 shots in 148 minutes. It’s a pity. Although The Hunt is a solidly crafted drama in the Nordic enemy-of-the-people tradition, it moves rather predictably across the combustible subject of false accusations of child molestation. Beyond the Hills, by Cristian Mungiu, director of Four Months, Three Weeks, and Two Days, is more enigmatic and demanding.

Voichita is a nun in a rural Orthodox enclave in Romania. She’s visited by her friend Alina. The two grew up as best friends in an orphanage, but Alina went to Germany to work, and now she insists that they must run off together. Voichita resists. Alina claims that Voichita once agreed to this plan. Has the young nun changed her mind and committed to the church? Or is Alina’s plan an idée fixe that Voichita has simply humored, without ever intending to join her? Were they perhaps lovers? Alina’s endless staring at Voichita and her lunges at suicide suggest deep passions at stake.

The refusal to supply full exposition makes characterization enticingly uncertain. Voichita’s wide-eyed sympathy for her friend can be seen as both pliable and stubborn, while Alina’s nearly wordless reprimands imply that Voichita has betrayed her. But perhaps Alina is just asking too much, or Voichita is being too unbending. The couple’s drama is played out against the stringent background of a female community ruled by a priest. Alina is incorrigible, not responding to the gestures of salvation extended to her, and agreeing, stone-faced, that she has committed every sin on a list of over 400. Eventually the pious souls decide that Alina is possessed, and her demons must be exorcised. In a simple gesture of solidarity, Voichita declares something like love for Alina, but too late.

Alternating discreet handheld takes with fixed shots staged in depth, making no concessions to impatience or easy responses, Beyond the Hills recalls the sobriety of Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Bresson’s Les anges du péché. It plays out in a rougher-textured, muddier world, but it’s no less concerned with the dynamics of compassion and cruelty, dogmatism and eroticism. In each, a woman is ready to sacrifice herself for love. As Romania’s Oscar submission, Mungiu’s film deserves to find an audience in the US.

Long takes were also a specialty of the late Raúl Ruiz, whose penultimate film, Mysteries of Lisbon, won him probably the widest audience of his career. That film displayed his fascination with proliferating stories, but its adherence to a single plane of reality was exceptional in the career of a fabulist who enjoyed confounding all types of realism. In that regard, Night across the Street, his last fully completed work, is more characteristic.

An old office worker is about to retire and is convinced that someone is coming to kill him. While Don Celso awaits his assassin, he fraternizes with his co-workers, with schoolteacher and author Jean Giono, and with others in the hotel where he resides. He also recalls his childhood, when he talked to Long John Silver and went to movies with Beethoven. Eventually the plot shifts levels of reality even more radically, as one séance blends into another, characters shot down in a massacre return to life, and eventually Celso takes credit for inventing the people around him.

Mungiu’s handheld shots have no place here. As in Mysteries of Lisbon and his Proust film, Time Regained, the camera glides through this world with velvety assurance. Sometimes the characters do too, as they seem to ride the dolly or saunter in front of a blatantly unreal backdrop. Ruiz subverts academic cinema by using its well-upholstered technique, but he also mines film history. He revisits tableau staging in the shrewdly split set of Don Celso’s office, and he continues to exploit his more-Wellesian-than-Welles big-foreground technique.

Above all, the boy’s trip to the movies, in an awkwardly tilted image in which the usher usually blocks the screen, pays typically skewed homage to the medium’s enchantment. The mock film of Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream has given way to The Foxes of Harrow, the Hollywood cinema of Ruiz’s childhood.

Land, sea, and sky

small roads (2012).

When one thinks of the long take, James Benning comes quickly to mind, and small roads is true to form—in more ways than one. Forty-seven fixed shots in 102 minutes take us from the Far West to the South and to the Midwest before shifting westward again. The roads are indeed small, far from superhighways and traffic circles. As usual, landscape is the protagonist and slight shifts in image or sound arrest our attention. There are plenty of perceptual teasers. When a distant truck descends the distant sloping road above, it vanishes. Will it re-emerge in the nearer road? At another point, we wonder when, or if a car we hear will appear in the frame.

Hogarth spoke of art that leads the eye “on a wanton kind of chase,” and Benning’s roads—almost never seen from dead center, so we’re not given central perspective—carve oblique or sinuous paths into fields, plains, deserts, and forests. Road signs reenact the curve of the roadway, with carets and squiggles providing spare geometric “readings” of the piled-up surfaces of color and mass. There’s also some synesthesia. In one shot, I thought I heard mist rolling in. The topographies are real but through Benning’s strict scrutiny they become as fantastical as Ruiz’s dreamscapes.

That’s why I suspect that roads aren’t the real subject of the film. They serve as a pretext for Benning’s recurring interests in how wind curls clouds and makes branches tremble, how light outlines trees, how shapes like squat black oil derricks and the textures of fat snowflakes and soggy leaves can command the frame. Now that Benning has moved to digital filming, he has discreetly inserted some CGI. I couldn’t spot any, though one partial moon in daylight looks suspicious to me. No matter. Painterly beauty, along with a certain placid mystery, is enough for any movie nowadays.

At the other extreme lies the bustle of Leviathan, a poetic, quasi-abstract documentary by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. The filmmakers capture a New Bedford fishing trip through GoPro digital mini-cameras worn by fishermen, tossed into a netful of fish, or dragged through the water. Long takes abound here too, but it’s hard to say how many. As in The Man with a Movie Camera, the very boundary between one shot and another is put into question. So is the boundary between us and the space onscreen, as we’re weirdly wrapped in the extreme wide-angle yielded by this lens.

This is what you get when no human eye is looking through the camera. Often, in fact, nobody could look through the lens. No head, let alone human body, could occupy the space of some of these shots. Chains roll out past us from churning greenish darkness, while fish drift and slither on all sides. We’re right next to a gull trying to use its beak to lift itself to another area of the hold. Here the fish-eye lens lives up to its name. The camera bobs in a tank as fish are tossed in and spin aimlessly past. Coasting along the edge of the craft, we dip abruptly in and out of the heaving water, our plunge accentuated by brutal sound cuts. We chase starfish and ride waves, spinning up to watch gulls blotting out the sky. Accelerations of speed (again, Man with a Movie Camera comes to mind) render the action hallucinatory, especially since the shutter can capture foam with strobe-like precision.

One result is a disembodied, dehumanized vision of sea and sky: The camera as flotsam. But we also get bumpy, skittish visions of human labor definitely tied to bodies that harvest the ocean. Work activities are filmed from cameras lashed to the fishermen’s heads or lying on the deck among scallops to be shucked. Most documentary close-ups of artisans’ tasks are taken from far back and with long lenses; here the very wide-angle GoPro lenses not only show tasks from the inside, but their distortions exaggerate each gesture, sometimes heroically, sometimes grotesquely. Either way, human activity has been defamiliarized no less than undersea life.

We start the movie immersed in a welter of details and stay enmeshed for nearly an hour. Only then do we get an “establishing shot” showing the boat deck and mapping the overall process of filling and emptying the nets. And fairly soon after that, as if to parody the usual documentary about fisher folk, we get a four-minute shot of the captain dozing off while watching a TV show (apparently The Deadliest Catch). Leviathan ends with a sequence that brackets the chiaroscuro of the opening, but we no longer see a clam’s-eye-view of being snagged. Instead, we get barely illuminated darkness with whiffs of crimson teasingly darting to the edge of the frame, as if to signal the end, before swerving back to the center, then heading offscreen. Again, Ruiz has the line: Special shadows that give off light.

Ready to declare cinema dead? There is a cure for your malaise. We call it a film festival.

More of my thoughts on Ruiz can be found here and here. His widow Valeria Sarmiento completed his very last project, The Lines of Wellington.

On small roads and digital manipulation, see Michal Oleszczyk’s discussion at Slant and Robert Koehler’s informative review in Variety. In correspondence Benning confirms:

Yes, lots of compositing, but no speed changing, although the border cops are going around 100 mph. . . . Shot 26 has a sky that was filmed the next day about 100 miles away. And yes the moon was out, but that shot is pointing north so I filmed the moon in the southern sky during the day, and put it into the northern sky. All the compositing was done with shots I made; always somewhere nearby. (100 miles is nearby when you circle 2/3 of the US.)

You can learn more about Leviathan from Dennis Lim’s article on the filmmakers in the New York Times. The New York Film Festival provides a lengthy Q & A on its website. See also Phil Coldiron’s “Blood and Thunder: Enter the Leviathan“ in the latest Cinema Scope, with some superb frame enlargements. Above all, don’t miss the extract on vimeo, which gives you a good sample of the splendor of this film.

Leviathan (2012).

The smoking section

Twenty Cigarettes.

DB here:

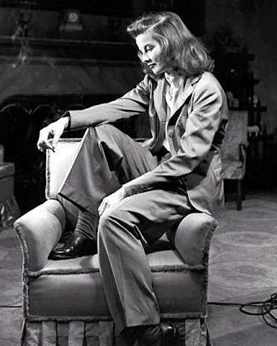

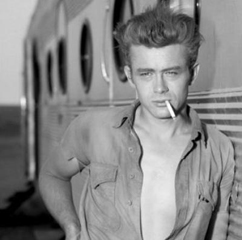

Reflect for a moment on the powerful role played by the cigarette in twentieth-century photographic portraiture. Before our recent worries about lung cancer, why were artists, movie stars, and other celebrities so often artfully posed with a tobacco product? Sometimes the imagery seems to evoke sophistication, presenting the subject as a man or woman of the world.

Or the portrait can suggest a relaxed, informal moment, a cigarette break.

That moment of relaxation can be extended to suggest contemplation or meditation, with the eyes gazing off into the middle distance. Despite the pretty face, this person is deep.

Alternatively, the cigarette can also suggest that painting or writing is a pretty casual affair. Smoking while working, the artist becomes an artisan. Maybe creating masterpieces is no more highfalutin than laying pipe.

And of course there’s the erotic side. A cigarette can make you look attractively dangerous.

In Golden Age studio portraiture, the smoke can become a compositional arabesque.

I’m not suggesting that James Benning set out to subvert this glamourous, stylized tradition in Twenty Cigarettes, which I caught at the Hong Kong Film Festival. But I think his film presents smoking as never seen before–defamiliarizing it, the Russian Formalist literary critics might say. And the movie’s not solely concerned with smoking. It resonates a bit with something I looked into in an earlier entry, on facial expressions in The Social Network. But here the film asks a different question: How expressionless can a face be?

Studied neutrality

A person in a medium shot smokes a cigarette. Repeat nineteen more times, showing smokers who suggest different ethnic and social identities. They are framed against outer walls, gardens, skies, or rooms. As in the Structural Film tradition, we witness an activity whose end is more or less known, and this forces us to study the minutiae of the process. But how much time the shot takes isn’t completely determined. Some smokers smoke faster than others, some shots run longer, and occasionally Benning halts the shot before the cigarette is quite finished.

In each shot, the smoker doesn’t talk and seldom looks at the camera. No one else is visible or audible (except, in one take, a voice distantly shouting, “Fuck you!”) Benning put himself out of sight during the filming of each take. By cutting the smokers off from all social intercourse, the film reminds us that it’s probably more usual for to people smoke while doing something else, like reading or watching TV or talking with friends. Benning forces us to watch the act of smoking in an almost artificially pure state. The film quickly becomes a study in smoking styles—quick non-inhalant puffs, luxuriant drags, little exhalations, slow streams curling out of nostrils. The ciggie is held tipped up in a dainty salute, or jammed between fingers. Solitary smoking becomes a sort of social-science experiment: If you can’t walk around, talk to others, window-shop, or whatever after you’ve lit up, how will you behave?

You’ll behave, Benning’s film suggests, by putting on the most blank expression possible. The portraits of artists and movie stars above use the cigarette to enhance the subject’s attitude–frankness, cool regard, disdain, pensiveness, intellectual seriousness. The cigarette, even the smoke, signifies. Nothing in the cigarette-portrait tradition prepares us for the almost frightening neutrality we see on the faces of Benning’s people. What are they thinking? Are they feeling anything?

It’s rather hard to maintain a poker face in a social interaction. Engaging with others, we spontaneously send signals of interest or mutual understanding, if only through raised eyebrows or a quick smile. But Benning’s lone smokers are eerily blank. Even what might seem to be an expression is often simply the person’s face at rest. (Some resting faces are read as non-neutral, as when an elderly person seems perpetually frowning or hangdog.) In the film, when the person’s expression changes, that’s usually because of the smoking; the twenty people squint or frown or tighten their jaw as they suck or exhale. For once facial movement is divorced from emotional signaling, and the result is a kind of anti-Shirin, Kiarostami’s portrait gallery of people caught up (apparently) in spontaneous bursts of emotion.

Benning’s film brings to mind the Warhol Screen Tests, and he has acknowledged the influence. Yet unlike Warhol, Benning gave his people the same specific task to execute. He’s like Hou Hsiao-hsien, who has explained that he got performances from his nonactors by letting them occupy themselves with eating and smoking. Warhol, as I recall, left things up to his performers, and so they might fiddle with props, run through a range of expressions, or simply stare innocently or challengingly at the camera. (To avoid reproduction rights problems, let me just send you here to sample some possibilities. On this page Nico the superstar seems herself to recreate the mystique of the classic studio portrait.)

Twenty Cigarettes yields something different from the Screen Tests I’ve seen. Using the cigarette as a constant feature, pulling smoking out of its usual place in our habits and social exchange, denying the tradition that shows smoking as connoting attitudes and emotions in people onscreen, Benning enables us to watch, across some ninety minutes, faces that aren’t dramatizing themselves or sending signals. No stars, these folks, let alone superstars. No narcissism either.

Yes, through dress and hair and demeanor we quickly characterize these men and women by type (housewife, hipster, working man). And each face carries marks of experience we can’t help but wonder about. At times I found myself looking for wrinkles and the other signs of smoking’s skin damage. And yes, the subjects know the camera is there, so to some extent they are posing themselves. Even granting all this, it seems to me that Twenty Cigarettes gives us a disconcertingly pure example of what happens when people make a tremendous effort to show as little of themselves as possible. We get to study what lived-in faces look like when they aren’t participating in social life but are aware that the camera is watching them.

Cigarette pictures, as if you didn’t know: Susan Sontag, Cary Grant, Louis Feuillade, Gary Cooper, Katharine Hepburn, Robert Rauschenberg, Jean-Luc Godard, Bette Davis, James Dean, Gary Cooper again, and Marlene Dietrich.

The website Celebrities with cigarettes includes many studio portraits. For examples from the Warhol Screen Tests, go here. On this page Nico the superstar seems herself to recreate the mystique of the classic studio portrait. Background on the making of Benning’s film can be found in this interview at Cinema Scope. On MUBI Neil Young provides a stimulating and painstaking analysis of Twenty Cigarettes.

Thanks to J. J. Murphy for discussions about Warhol, the subject of his forthcoming book, and of course to James Benning for his assistance.

Twenty Cigarettes.

Dispatch from sunny Vancouver

Ballast.

After six days, plenty to report from the Vancouver International Film Festival. It has been unusually warm and sunny during our first week, but we have diligently spent most of our time in darkened theaters.

Kristin here:

Another country heard from

It’s a rare day when one gets to see a Haitian film. It’s an equally rare day when one gets to see a Jordanian film. On Monday I saw both, and the contrast between them could hardly have been greater.

Eat, for This Is My Body (Mange, ceci est mon corps, 2007), a Haitian/French co-production is Michelange Quay’s first feature. A Haitian-American, Quay received his MFA in directing at New York University.

The film’s opening is extraordinary, with a series of low-altitude helicopter shots beginning over the ocean and then moving rapidly across huge shanty-towns and finally into bleak mountain canyons in the country’s interior. After this passage of flight over bright landscapes, the bulk of the story takes place in and around a quiet, dark, nearly deserted colonial mansion somewhere in the countryside.

I’ve noticed that there seems to be a mini-revival of 1970s-style art cinema conventions. After many years in which art cinema tended to mean intricate psychological studies, a more challenging, formalist avant-garde seems to surface now and then. While watching Eat, for This Is My Body, it occurred to me that it could almost have been called Haiti Song, so strongly did it remind me of Marguerite Duras’s India Song. There enigmatic actions, often dancing, were staged in a colonial house. Eat, for This Is My Body’s action is, if anything, more enigmatic, though in this case the native population is present in the house in the person of a dignified manservant and a group of nine boys brought at intervals into the house, apparently as a treat.

The story is so minimal as to be non-existent. Apart from the nine boys, there are only three characters: an  old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

The Jordanian film, Captain Abu Raed (2007), takes a more familiar approach, centering around a likable, heartwarming protagonist. Raed, an airport janitor, finds an old pilot’s hat, and the children in his working-class neighborhood assume he really is a pilot. He plays along, less to feed his own ego than to inspire their imaginations through false tales of his adventures abroad. Gradually he becomes more involved in the lives of some of his listeners, and the film progresses from the sugar-coated tone of the opening scenes into a darker situation as Raed seeks a way to save the family of a violent neighbor.

Director Amin Matalqa was raised principally in the U.S., but he returned to his native country for this, his first feature. It is also the first feature film to come from Jordan in decades, and it reflects a slow but distinct movement into movie production in some of the Middle-Eastern countries where conservative religious views have long suppressed it. Captain Abu Raed is technically polished and makes considerable use of Amman cityscapes and ancient ruins as backdrops for the action. It’s also definitely a crowd-pleaser, judging by the sold-out audience I saw it with.

Another rarity is Australian director Benjamin Gilmore’s first fiction feature, Son of a Lion (2007), which he filmed entirely in the Peshawar region of Pakistan. That’s an area adjacent to the northwest border of the country with Afghanistan, notorious as a refuge for Taliban fighters and probably Osama bin Laden. The program lists Son of a Lion as an Australian/Pakistan production. I doubt any Pakistani funding went into it, but Gilmour wrote the script with the advice of the local people, and non-professionals play all the characters. The credits also contain quite a few Pakistanis performing tasks behind the camera.

The story seems inspired in part by the “child’s quest” narratives of the Iranian classics of Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

Son of a Lion was shot under difficult and dangerous circumstances on digital video (with post-production handled, amazingly enough, by Peter Jackson’s Park Road Post facility in New Zealand). The shots of the beautiful desert landscapes are not up to those we are used to from Iranian films, but they manage to suggest the grandeur of the area and to give a fascinating and humanizing insight into a region which the American government and media portray as merely a hotbed of terrorism.

Moroccan films are not quite as rare as these, but they’re certainly not common. As Burned Hearts (Morocco/France, 2007) was being introduced, I realized that the only other Moroccan film I had previously seen was by the same director, Ahmed El Maanouni. That had been Trances, a semi-documentary1982 film about a touring pop-music group. It was shown last year at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, having been the first film restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Founda tion.

Burned Hearts was another film that seemed to transport me back to the 1970s art cinema. A young man returns to his childhood home after being educated as an architect in Paris. His tyrannical uncle is dying, and flashbacks present the painful memories evoked by the familiar sights and sounds of the city, this exploration of the character’s mental paralysis, along with the black-and-white cinematography of the locations, evokes both Duras and Antonioni. But El Maanouni refuses to concentrate solely on the hero’s concerns, bringing in several intriguing characters from the neighborhood and having groups spontaneously break into song and dance in the streets and shops.

Melodramas from Mexico

These films all come from regions seldom represented in international film festivals, but Mexican cinema  has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

The other Mexican film, All Inclusive (2008), deals with another family crisis, but one which takes place over a few days in a luxurious resort on the “Mayan Riviera.” The story is slickly told by director Rodrigo Ortúzar Lynch and beautifully shot by Juan Carlos Bustamante, but I found the story forumulaic. A man who has just been told that he has only a short time to live, goes on vacation with his family, whom he has not informed of his condition. As he struggles with his secret, his wife and three children undergo their own crises. One daughter faces up to the fact that she is a lesbian, the son becomes entangled in an online “affair” with another man’s girlfriend, and the wife, assuming that her husband is being unfaithful, allows a young scuba instructor to seduce her—all this observed by the sardonic goth daughter.

As the tensions grow, a hurricane approaches, and the climactic set of revelations and reconciliations come just as it hits. During the narrative, each of the troubled family members manages to find someone gorgeous willing to bed them and/or hear their tales of woe. The idea that the bearish husband, seeking escape in a local bar, would run across a stunning 23-year-old Cuban woman who would take him into her home, listen at length to him, and finally, of course, teaching him to enjoy life. This gives him the courage to return to his family and tell them the truth. Once the family members have bared their soles, they become a jolly, well-adjusted bunch. It’s an entertaining story with likeable characters and touches of humor—but it’s a bit too much to believe.

Americans in Canada

Apart from Craig Baldwin’s Mock Up on Mu, which David will cover, I’ve seen two American indies so far. Momma’s Man (2008) is directed by Azazel Jacobs. It deals with Mikey, a man traveling on business who has problems with his flights and ends up staying with his parents in their New York loft. Finding excuses not to return to his wife and baby in California, he fritters away his time by reverting to his childhood pursuits. The film takes the daring step of being centered on an unsympathetic character who is the point-of-view figure for all but a few scenes. It manages to convey his gradual move from indecision to obsession and eventually a full-blown breakdown in a believable fashion.

Part of the appeal of Momma’s Man comes from the fact that Mikey’s parents are played by Ken Jacobs, the great experimental filmmaker, and his artist wife Flo Jacobs. It is set in their actual New York loft, a maze of odd filmmaking devices, accumulated pop-culture artifacts, and artworks. The two give extraordinary performances, managing to seem wise and caring and at the same time obsessive and eccentric to a degree that might have contributed to Mikey’s breakdown. Although Jacobs cast an actor as Mikey, one has to suspect that the film is at least somewhat autobiographical, and the casting of his parents has created a uniquely convincing portrait of a family.

David and I were delighted to see RR (2007) on the program. It’s the latest feature by American avant-gardist James Benning. Jim is an old friend, having been a graduate student in our department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison during our early years there. He has concentrated largely on landscape films, usually consisting of lengthy, static shots. This one consists wholly of distant views of trains in what appear mostly to be western and Midwestern locations. In virtually every case the shot holds until the entire train has moved through the shot or out of sight—or stopped, in a few cases.

As so often happens with structural films, small variations become evident to the alert viewer. A shot of a  car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

RR draws us to enter into perceptual play, often with a distinct touch of humor. Few of Jim’s films have contained the measure of their shot length in their mise-en-scene so decisively. The length and speeds of the trains determine the duration of the shots, and one learns to watch for the number of engines pulling or pushing a train as an indicator of how long the train is likely to be. A few shots show trains moving slowly and decelerating at an almost imperceptible rate, teasing us as to whether they will stop altogether and whether the shot will end if they do. At times a train may move through the shot, only to reveal another on a parallel track. One shot plays a very clever game with us. I won’t reveal what it is, but the shot comes perhaps a third of the way through: an oblique view along a track with bushes prominently in the foreground and a short, arched underpass in the middle distance.

Jim has continued to shoot in 16mm in an increasingly digital age, and he consistently manages to make gorgeous images that look more like 35mm. The last one of RR, involving a vast wind farm, is a stunner.

Captain Abu Raed.

David here:

An unusually good VIFF, with many films to get your eyes open.

Enter the Dragons, with Tigers

As usual, the venerable Dragons and Tigers thread is offering some remarkable new films from Asia. The Good the Bad the Weird lived up to its reputation, not to mention its title, offering frenetic action and comic-book (in the good sense) bravura. Sell Out!, a Malaysian satire of corporate maneuvering and media brainwashing, doesn’t get points for subtlety—the goliath is called the FONY corporation—and sometimes it tries too hard. Still, it’s likeable enough, and the fact that it’s a musical adds a welcome bit of froth. The funniest bit, for me, was the opening parody of an art movie, which does actually get integrated into the main action.

Two late works by long-time Japanese directors offered a study in contrast. Kitano Takeshi’s Achilles and the Tortoise starts out sweet and ends very sour, not to say bitter. In telling the story of a boy whose spontaneous love of drawing is forced into narrow commercial channels, Kitano suggests that art is a racket. Across the decades, schools and galleries push the pliant, nearly comatose young artist to create a signature style. He is told to be original, but also he must harmonize with fashion and tradition. With a grim obstinacy he tries to fulfill what the business demands, and to the end he is still trying.

Achilles is less willful than Takeshis’ and Glory to the Filmmaker!, and it tells a more coherent tale, but their glum narcissism is still in evidence. The film cries out for an autobiographical interpretation: is the naïve filmmaker corrupted by exposure to international art cinema? Pictorially, there’s some confirmation of this: Kitano seems to have abandoned his early films’ ingenious use offscreen spaces and planimetric compositions. Like his hero, who can’t achieve artistic singularity, Kitano has become a surprisingly academic and anonymous stylist.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

Wakamatsu’s technique is unstressed: No fancy angles, neverending tracking shots, or virtuoso compositions, just a businesslike application of today’s wobbly handheld look. The cunning lies in the film’s structure. After a half-hour montage summarizing the formation of the group, we are carried into the hideouts and watch the punishment grow more feverish and self-destructive under the domination of two leaders who seem parallel to Mao and Madam Mao.

By the end of the second hour, the remains of the army are on the run, struggling through vast snowy landscapes. Soon four survivors straggle into a ski lodge, hold the owner’s wife hostage, and face their final challenge: wave after wave of police assaults. Waiting for the inevitable outcome, the survivors spare time for grim humor: On 28 February one remarks, “I’m glad the all-out war won’t be tomorrow. Then my death anniversary could come only every four years.” And they can pause for an exercise in political discipline. After a lad takes an extra cookie, he criticizes himself. Stern reprimand follows: “That very cookie you ate is an anti-revolutionary symbol.” Unsentimental and unsparing, United Red Army is over three hours long, with not a longueur in sight.

A man parks his car to pick up some cake at a bakery. He has been away from home all night; now he’s rude to the lady behind the counter. Having bought a couple of cakes, he finds that a sinister black car has double-parked and hemmed him in. His efforts to find the owner lead to a spiral of comic and pathetic confrontations with an orphan child, burly Triads armed with whitewash, and a pimp with a distinctly bad haircut.

Creating something of a network narrative, Chung Mong-hong’s Parking in its modest way offers a cross-section of Taiwanese society, from the prostitute brought over from China to a jaunty barber who more or less controls the switch-points of the story. The ending will strike some as dovetailing all the cards a little too smoothly, but I found it satisfying, if only because it lets our haughty hero show unexpected resilience and compassion. This is only Chung’s second feature, but his work bears watching.

For once, it really is rocket science.

If you’ve already figured out the deep connections among Scientology, the aerospace industry, ritual sex magic, New Age spirituality, and the migration of Los Angeles hipsters to San Francisco in the 1950s, Mock Up on Mu won’t come as news. If, like me, you haven’t the faintest idea about the cat’s-cradle ties among these cultural phenomena, Craig Baldwin’s latest collage-essay-epic-lyric-narrative (all terms he applies to it) is the very thing you need. It’s as exuberantly peculiar as his earlier work like Tribulation 99 and Spectres of the Spectrum, flooding us with a relentless voice-over that splits off from and reconnects with the torrent of images grabbed from all manner of movies.

These earlier films had stories of a sort, swollen conspiracies and ominous coincidences that make Baldwin the eccentric cousin to Fritz Lang. But Baldwin says that these stories couldn’t really engage people, couldn’t get them to identify. Mu tells a more personalized tale. L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology, has colonized the moon and sends Agent C to earth to arrange for people to be shipped up. Agent C runs afoul of Lockheed Martin, corrupt aerospace executive, and becomes attached to Jack Parsons, an early rocketeer who in the 1950s assumed the secret identity of Richard Carlson, so-so Hollywood actor. Meanwhile, Aleister Crowley rules a secret society at the center of the earth….

Or maybe not.

Actually, I won’t swear to much of what I just said. Baldwin’s phantasmagoria tests my memory, as well as plausibility. The story line is swallowed up by what he calls footnotes—swarming digressions, tangents, and flashbacks which are conjured up in imagery that shoots off in a dozen different directions. A few frames from a kiddie science movie or a grade-Z space opera, juxtaposed to Parsons’ rapid-fire account of the history of rocket testing, whiz by almost subliminally.

In any case, there are characters and a more or less linear story. But Baldwin is Baldwin, so things can’t be so simple. He has for the first time staged and shot footage of actors, and their scenes form a sort of string that you can follow. But just as crystals grow in fantastic array along a string, alien footage exfoliates out from the staged scenes. Baldwin aims, he says, at “a dialectical density.”

The result is a narrative experiment I’ve never seen before. With a simple cut, our characters are replaced by figures from other films, who become, in some spectral fashion, both alien inserts and our characters.

Confused? Here’s an example. Agent C (who will turn out to be Marjorie Cameron, muse of many West Coast artists) is riding with rocket scientist Jack Parsons. A series of shots shows them in the car’s front seat.

As the scene goes on, one character gets replaced by another.

Eventually both of our originals have been replaced.

The stand-ins can even change position as the dialogue continues uninterrupted (but always mis-synchronized).

The cuts make the inserted characters surrogates or avatars for our people, but they retain wisps of their original, enigmatic existence. They also remind us that situations like driving in a car are genre stereotypes, schemas so common that individual instances can serve as place-holders for one another. Yet the shots always return to the original actors, anchoring the associations and keeping at least one plane of the narrative moving forward.

These phantasmagoric shifts make the identity transformations in I’m Not There look labored. In Mock Up on Mu Baldwin may have found a new method of cinematic storytelling. Don’t expect Hollywood to pick it up soon.

Pulling half away

How do you tell your audience what it needs to know to understand what it’s seeing, and what it will see? A film can handle exposition (aka backstory) in several ways. Most films favor concentrated and preliminary exposition: Most information is given in one spot and quite early on. This is when you get the opening dialogue when characters say to one another: “Look, you’re my sister. You can tell me.” (Ohh…They’re sisters.) Concentrated, preliminary exposition is usually clunky, but it can be done with finesse, as in the opening soliloquy of Jerry Maguire.

The major alternative is distributed exposition, where information about the backstory is spread out, evenly or unevenly, across the film. This is common in mystery films (as when, under pressure, characters start to confess their relation to the murder victim) and in “puzzle films” like Memento, where we only gradually understand the relations among the characters. Delayed and distributed exposition in straight dramas is common in European art cinema, but it’s rare in the US, although independent films like Claire Dolan and Man Push Cart have made good use of the technique. Kristin already mentioned a similar strategy at work in Eat, for This Is My Body.

Lance Hammer’s Ballast comes garlanded with praise from festivals and major news outlets like the New York Times. For once the advance word is justified. I thought that Ballast was an exceptional intimate drama, focused almost entirely on three people and their layered relationships in a country town in the Mississippi Delta.

At this point I should mention how the three principals are connected, but part of the daring of Hammer’s film is to postpone, for almost an hour, telling you such things. He says he wanted a film that is, like the Delta, “spacious and quiet and slow.” Here the very issue of what we need to know is put into question. By blocking our knowledge of characters’ relationships, Hammer forces us to confront moments of action in a pure state. Each instant, each shot even, gains an integrity and gravity it wouldn’t have if we knew the full dramatic context.

Take the opening. After a brief, wordless prologue showing a boy in a field of crows, we’re in a vehicle pulling up at a bungalow.

The indistinct figure of a man goes to the door. Inside, a brief shot shows a black man’s face in silhouette.

Soon, the first man, who is white and weatherbeaten, is seen at the door, expressing concern for the man inside.

The white man enters, wrinkles his nose at a smell, and proceeds to another room, where a figure, turned from us, lies on a bed.

The black man continues to sit impassively before his TV, though now we can see his face more clearly.

Who are these men? What connects them? Who has died? An ordinary film would tease us with these questions but answer them fairly soon (say, in the next three or four scenes). Here, we will have to wait a considerable time to find out the answers. In the meantime, what we have registered in place of an action arc is the atmosphere of shock, sorrow, grieving, and lowering skies. And almost immediately a rather dramatic event will occur, nearly offscreen, and its causes will remain equally opaque for quite some time.

Ballast’s delay in spelling out its story premises is sustained by two unusually quiet main characters. Lawrence, the man sitting in the darkness, leads a solitary life and speaks reluctantly and briefly. Likewise, the boy James is often silent or alone. These two don’t soliloquize, and they live one day at a time. We must simply observe their behavior, try reading their minds, and more generally absorb the emotional tenor of their lives.

The sparseness of the exposition also puts us on the alert for any scrap of information that will fill in the blanks. For instance, references to “the store” flash out as clues to possible connections among the characters. Hammer’s strategy demands that the audience exercise a degree of patient concentration that most films never ask for.

For roughly the first half of the film, then, Hammer’s narrational technique creatively impedes our full understanding of the basic givens of the story. Once the relationships have coalesced (though there are still some revelations to come), the dialogue becomes more explicit and, some would say, the drama more traditional. But the visual narration continues to mute and elide dramatic moments. At some points pieces of action are rendered opaque by the bobbing, jump-cut camerawork. Most memorably, a clumsy embrace is hidden by a “wrong” camera setup, all the better to make us wonder about the impulses behind the gesture. Hammer matches his oblique plotting with an oblique visual style.

Hammer has cited Bresson as an inspiration, and in conversation he also mentioned late Godard, who has become willing to avoid exposition for nearly an entire film. Unlike Godard, who seems to revel in the pure artifice of withholding information, Hammer appeals to realism: The gradual piecing together of the narrative, he remarked to me, is like our coming to know people in life, bit by bit.

Correspondingly, by the end of Ballast we come to feel more empathy for Hammer’s characters than for Godard’s, and possibly even for most of Bresson’s enigmatic souls. But the empathy doesn’t come cheap, and it isn’t wallowed in. The climax is brushed past in one sideswiping shot; blink and you’ll miss it. In another interview, Hammer speaks of “putting something out and pulling half away.” By leaving us to fill in that half, Hammer exhibits his respect for his characters, and for his audience.

Mock Up on Mu

P. S. For dispatches from 2006 and 2007 editions of the VIFF, type Vancouver into our search box.