Archive for the 'Directors: Eisenstein' Category

Rotterdam starts strong

Dear Comrades! (2020)

DB here:

Thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, we’re able to visit this venerable event, celebrating its fiftieth year! As with Venice and Vancouver, we’re happy to get online access to some outstanding films. We pass along the news to you here and in upcoming entries.

A dish best served cold?

Riders of Justice (2020).

Why is revenge so common as a driving force in film, fiction, and drama? Well, it sets up story action we like: search, mysteries, discovery, pursuit, confrontation. And it’s an impulse we find easy to understand. If you wrong me or mine, I’m likely to want payback.

As a high-school teacher once said to me, when I protested that the punishment wasn’t fair: “I don’t want to be fair. I want to be just.” In real life, Trump whines about unfairness, but he wouldn’t recognize justice if it met him head-on. Which it just might. Anyhow, in movies justice becomes our noblest excuse for the pleasures of vengeance.

Once our sympathy for the avenger is aroused, the storyteller has to decide how to treat the plot. Revenge shouldn’t be easy. It comes with a price. In Hong Kong films, revenge is usually the righteous settling of accounts.The price it demands is usually physical (wounds, maybe death) and social (the loss of friends cut down in the assault).

There’s another tradition of revenge drama that emphasizes the moral costs of revenge, the sense that it taints the avenger. You turn implacable, self-righteous, prone to error. Maybe the target isn’t really guilty? And can’t you forgive? And aren’t you turning obsessive? Can you sacrifice the other parts of your life to this mission? All of these questions haunt Anders Thomas Jensen’s seriocomic thriller Riders of Justice.

Markus, a stolid soldier, returns home when his wife is killed in a subway accident. His daughter Mathilde is traumatized. Markus’s stoic grief changes to rage when he is told by the statistician Otto, who survived the accident, that the crash was engineered by a gangster killing a rival. Markus’s icy pledge to vengeance sweeps up Otto, his two hacker friends, Mathilde, her boyfriend, and others.

In early days of this blog I wrote a lot about Danish films, which I’ve always admired. Many years ago Anders Thomas Jensen, director of Riders of Destiny, brought to our Wisconsin Film Festival The Green Butchers (2003). His scripts, for his own films and those directed by others, find a unique, tightly designed blend of drama and humor, with a penchant for showing the dumb side of male bonding (In China They Eat Dogs, 1999; Flickering Lights, 2000; Adam’s Apples, 2005)

Riders of Justice is in this vein, but it plays with larger ideas too. It starts and ends with a network-narrative premise (again, very Danish) emphasizing remote human connections. In between the characters come to grips with the role of chance in their lives. Scenes both serious and comic show them trying to reckon the reason behind their impulses. Even the numbermumbler Otto, who calculates probabilities of everything, admits to Mathilde that even the simplest event is impossible to explain through cause and effect.

You know that comfortable feeling you get at the start of a movie, when the story has hooked you, the characters command your sympathy (even when they make mistakes), and you realize that you’re in good hands for the next couple of hours? That was my response to Riders of Justice. Not least, it brings together for the umpteenth time two of the finest actors in world cinema, Mads Mikkelson (scary, in a trim Pentateuch beard) and Nikolaj Lie Kaas (sensitive, blinking behind wire-rims).

Riders of Justice has been purchased by Magnolia and is planned for a spring release.

Bolshevik nostalgia in 1.33

Dear Comrades! (2020)

“Dear Comrades!” is the salutation of a letter never sent. At a meeting of officials trying to handle a sudden strike, Lyudmila Syomina voiced a need for harsh reprisals for these traitors to the Soviet state. But after being called to write a letter and read it at a forum, she flees. She is torn by fear that her daughter has been captured or killed during the very violence she advocated.

Dear Comrades!, the latest and perhaps best film from the distinguished, pleasantly erratic director Andrei Konchalovsky, is set in Novocherkassk, 1962. The strike and the massacre were revealed in 1975 by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and confirmed by an inquiry in 1992. Konchalovsky has undertaken a historical recreation, an examination of his parents’ postwar generation, and, I think, an oblique critique of authoritarianism. He seems equivocal about Putin’s “managed democracy” (though he’s not as big a booster as his brother Nikita Mikhalkov). In any case, we can’t help seeing the film as echoing the tyranny on display in Russia’s recent years, i.e., yesterday. Unlike the current demonstrators supporting Navalny, though, Konchalovsky’s characters yearn for well-run autocracy. After all, under Stalin, prices went down.

Classic Soviet fiction and film featured what’s come to be called a “conversion narrative.” In order to build any plot, you need drama. But you also have to conform to Bolshevik ideology. Some conflict can be supplied by villains (“traitors,” “wreckers”) seeking to undermine the Great Soviet Experiment. You can also create drama with characters who are ignorant of the true way, or uncertain about abandoning personal commitments and embracing the Party. So the plot can trace the gradual conversion of a character to sturdy Communist principles. This functions, in classic Socialist Realist storytelling, as psychology.

But Lyudmila is a hard-core Party loyalist. She benefits from the perks of office: a love affair with her superior in a nice apartment, the ability to jump the queue scrambling for food and matches, a paycheck that pays for a European-style coiffure. In exchange she mouths, with unblinking cobra severity, a strict adherence to policy. Yet her daughter Svetka has joined the strike and goes missing during the melée.Lyudmila’s search doesn’t easily dissolve her ideological tenacity. Like Mother Courage, Lyudmila stubbornly refuses to see what’s in front of her. She can’t believe that the KGB, not the Army, would plan a massacre that mowed down citizens.

Eventually we get glimpses of a de-conversion narrative. Lyudmila starts to sense that the current system is corrupt. “What am I supposed to believe in if not communism? Blow it all up and start again.” Yet what should replace it? The only alternative she knows. “I wish Stalin would come back.”

Konchalovsky has shot the film in lustrous, drypoint black and white, and in a silent-era ratio of 1.33:1. It’s one of the most elegantly composed and staged films I’ve seen in recent years; it could be studied just for its use of axial cuts. I’d almost call it “Straubian-Huilletian,” were it not so defiantly committed to the melodrama of a family crisis within social turmoil. But Dear Comrades! is far from your standard historical pageant. It’s at once austere and inventive.

Konchalovsky activates a great many motifs from classic Soviet film, treating them both for sly comedy and sharp drama. Satire on bureaucracy, another traditional source of plot developments, pervades the first half. Like Eisenstein in October, Konchalovsky can spare a shot mocking an empty conference table after the staff has fled.

Eisenstein is of course more grotesque: the panicked Mensheviks have leaped out of their furs, or been Raptured. The portrait of Khrushchev stands in for the Stalin picture hanging in every Socialist Realist office, parlor, bivouac, and meeting hall.

Konchalovsky stages the massacre of the strikers mostly through the heroine’s viewpoint. In place of the vast views supplied by Eisenstein in October (1928), the camera is tied down to a beauty shop.

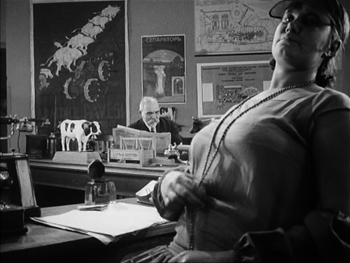

In Soviet World War II films, the officials plan strategy in monumental headquarters (Front, 1943). The shabby offices of Konchalovsky’s provincials seem both cramped and hollow.

During the agitation and cleanup, Konchalovsky seems to me to rework specific images from Eisenstein’s Strike (1925). The hosing of blood from the streets seen in reflection echoes a shot of the factory in Strike. And in both, the police study the spies’ snapshots of strikers.

Dear Comrades! deserves all the attention it’s getting. Winner of this year’s Special Jury Prize at Venice, it has been picked up by Neon for US release. It’s also Russia’s submission for the Best International Feature Film Academy Award. It’s being streamed by several film festivals, notably Seattle’s, which offers it at a very reasonable price. But how I long to see it on the big screen.

I discuss some Danish network narratives in Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema and other examples in some entries. Katerina Clark has an excellent discussion of the conversion narrative in The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Indiana University Press, 2000). For a discussion of Socialist Realist film style, see this entry.

P.S. 4 Feburary 2021: Anders Thomas Jensen gives a very informative interview about Riders of Justice in Variety.

Riders of Justice (2020).

The ten best films of … 1929

Lucky Star

Kristin here:

As 2019 fades away, it’s time once more to look back ninety years at some great classics. This series started somewhat by accident, when we wanted to celebrate the pivotal year 1917. That was when the stylistics of the Classical Hollywood filmmaking system, which had been slowly explored for several years, finally clicked into place and became the norm in the American studios.

After that, our series became a regular and surprisingly popular feature. The point is partly just to have some fun and partly to call attention to great films that have remained obscure and/or difficult to see.

For past entries, see: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, and 1928.

After the riches of the 1920s silent film, 1929 stands out as an anomalous year. The transition to sound was under way internationally, but different countries proceeded at different paces. The new technology often was not amenable to maintaining the freedom of cinematographic and editorial style achieved during the height of the silent cinema. There are arguably not as many indisputable masterpieces from this year as from previous ones–but there are some.

Oddly enough, truly major films from this year seem to have suffered a great deal from a lack of access, both in distribution of prints and release of good (or even any) copies on home-video formats. In part I want to draw attention to the shocking neglect of some great movies.

The list is dominated by Hollywood and especially the USSR, for opposite reasons. The American studios were well into sound production, and some of the top directors found tactics for using the new technique in imaginative ways.

In the USSR, on the other hand, silents reigned. Moreover, the great directors were not lured away to work in America, as so many European filmmakers were. (For example, Murnau’s career was nearly over, and he released no films in 1929.) Thanks to them, the golden age of silent cinema continued on.

A great year for the Soviet Montage movement

The General Line (aka Old and New, dir. Sergei Eisenstein)

The General Line is probably the least of Eisenstein’s four silent features. The earlier films were all set before or on the very day of the 1917 Soviet Revolution, and they all have a vigor and a sense of political fervor that The General Line can’t quite match. Instead, it’s about policy, specifically the portion of the First Five-Year Plan devoted to the collectivization of private farms. Eisenstein adopts an odd tactic for dramatizing the need for such a drastic overhaul of life in the countryside. He presents a single protagonist for the first time, Marfa, a poor peasant working her land alone and without a horse for the plowing.

She becomes convinced that the answer to her and her neighbors’ plight is to create a cooperative dairy for the village. But throughout, Marfa has few allies and encounters opposition from both the local wealthy Kulaks and the poor peasants, who are portrayed as ignorant, greedy, and even violent in their determination to retain full ownership of their farms and livestock. Marfa is too weak to succeed without the support of the local government agronomist and a few like-minded farmers. The task of collectivization seems too overwhelmingly difficult to ever succeed.

In retrospect, we know about the systematic exile and execution of the Kulak class and the famines that resulted from government tactics over the coming decade. It is unpleasant to see Eisenstein, however unwittingly, providing propaganda for Stalinist policies.

Still, Eisenstein is Eisenstein, and The General Line is as formally daring as his earlier work. Apart from dramatic angles and rapid, jarring cutting, he experiments with extreme contrasts of elements within the frame by using depth compositions. These exploit wide-angle lenses and create impressive deep-focus images. In the shot above, Marfa is dwarfed by a pampered bull in the near foreground, and in a third plane beyond her we see the grotesquely fat Kulak lolling in the sun on his porch.

Other compositions create even greater contrasts. On the left, Eisenstein provides an image of bureaucratic indolence, official red-tape being a favorite (and apparently approved) satirical target for Soviet filmmakers. On the right frame, there’s a suggestion of the power of the collective’s new bull, who will sire a generation of calves.

Despite the grimness of the situation, Eisenstein manages to slip in an unusual amount of humor, and The General Line is quite entertaining.

The best DVD version I know of is the French one from Films sans frontiers, which is still available from Amazon France. The print in Flicker Alley’s “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film” is somewhat grayed out in comparison. Unfortunately this important set seems to be out of print. Flicker Alley rents The General Line online here.

New Babylon (dir. Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg)

This masterpiece by Kozintsev and Trauberg is all too little known. Information on the internet tends to come more often from musicologists, since Dmitri Shostakovich wrote the original musical accompaniment, rather than from film scholars. Many viewers have heard recordings of the score but not seen the film itself.

Kozintsev and Trauberg were the leading members of the FEKS (“Factory of the Eccentric Actor”) filmmaking group, based in Leningrad rather than Moscow. As the name suggests, the practitioners aimed not at realism, but at the grotesque, the comic, and the appeal of popular rather than high art.

New Babylon deals with the Paris Commune of 1871, a brief period when workers took over the French government. It was seen as a forerunner of the Soviet Revolution.

The title refers to a giant Parisian department store, which also seems to be in the business of putting on patriotic operettas about the current war with Germany. The store’s owner and patrons, as well as the performers in the operettas (see above) represent the bourgeoisie, while the workers who staff the store and create its products eventually rebel and run the doomed revolutionary government.

Again there is a heroine who represents the people, though she is unnamed, being known only as the shop assistant. She begins as a naive girl selling lacy clothing at the New Babylon and ends by becoming a militant revolutionary, standing atop a street barricade made up of the contents of the store–with the lace becoming bandages.

In keeping with its eccentric nature, the film mixes broad humor in the depiction of the bourgeoisie with grim tragedy as the defenders of the commune are shot in street fighting or tried and executed. The FEKS directors came from experimental theatre, but they also mastered the art of editing. New Babylon contains virtuoso sequences of crosscutting that sharpen the class struggle at the heart of the film.

New Babylon was restored in a joint venture by Dutch and German broadcasting channels and released, with the Shostakovich score, on DVD. There are Dutch and German versions, as Nieuw Babylon and Das neue Babylon respectively, which are out of print. We have the former. These retain the Russian intertitles, and, despite what the covers say, there are English and French optional subtitles as well as Dutch and German ones. (The booklet, however, is only in Dutch or German.) The quality is acceptable, but this film really needs a better restoration and Blu-ray release. It seems evident that the aspect ratio used in the current release crops the image to some extent.

Man with a Movie Camera (dir. Dziga Vertov)

I need say little about this film, since it has been widely seen, praised, and discussed. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, when many academic film scholars were obsessed with “self-reflexive,” or, less redundantly, “reflexive” films, Man with a Movie Camera was the great film. The result was, perhaps, that this admittedly very fine film was over-hyped. Nowadays it is as likely to be studied for the fact that Vertov’s wife, Elizaveta Svilova, created the very flashy Montage-style editing as it is for its reflexivity.

She is even seen doing so. At a number of points brief scenes of her examining, sorting, and splicing shots, which are subsequently seen in motion or in freeze-frames.

The film is a documentary, showing the filming, assemblage, and projection of a city symphony along the lines of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt, of two years earlier. Vertov’s version sort of a day in the life of Moscow (and glimpses of other cities), also beginning with the city waking up and going to work. Here, however, we see cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman (Vertov’s brother), with his camera and tripod traveling around the city, climbing factory smokestacks, filming from moving cars, and so on. Although many shots are straightforward documentary images, others use special effects, such as split-screen in the opening shot on the right below.

The film is available (as The Man with the Movie Camera) in Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray of Vertov’s main surviving silent and early-sound films.

Arsenal (dir. Aleksandr [or Ukrainian, Oleksandr] Dovzhenko)

Ukrainian director Dovzhenko came somewhat late to the Montage movement, contributing Arsenal in 1929 and Earth in 1930. When I was in graduate school, these were classics that everyone saw, mainly because 16mm prints were circulating. Now I wonder how many students and cinephiles see them. The standard print that has been released on DVD by a number of companies is quite poor: dark, low-contrast, cropped (though not as badly as the End of St. Petersburg version I complained about in our 1927 list).

Arsenal begins with the return of Ukrainian troops from World War I, with an emphasis on the decimation and impoverishment of the rural countryside with the loss and mutilation of many farmers. Only well into the film are we introduced to Timosha, the stalwart young representative of the proletariat who weaves through the film but does not really become a conventional protagonist.

Dovzhenko has come to be viewed as the poet of the Montage movement, and many of the scenes, especially early on, are more grimly lyrical than part of a straightforward causal chain of events. There is also a touch of what we would now call “magical realism,” as in two scenes where horses speak to their masters. Dovzhenko also employs a wide range of Montage techniques: canted shots (as above); very rapid, rhythmic cutting; jump cuts; compositions with very low horizon lines (below); and so on.

Given the importance of Arsenal, it is a shame that the old copies have not been replaced by high-quality, restored DVDs and Blu-rays. The images here are taken from the best release I know of, Image Entertainment’s old DVD. I’ve boosted the brightness and contrast, but the result is still not ideal, and the DVD is long out of print. (It’s worth seeking out, since it has a commentary track by our friend and colleague Vance Kepley.) The best version I have found is on YouTube, using the Film Museum Wien print. It’s not cropped and has a brighter, less contrasty image (on the right in the comparison above); the subtitles are in French.

Hollywood on the verge

I presume that some readers will expect to see the two official classics of early sound Hollywood, Ernst Lubitsch’s The Love Parade and Rouben Mamoulian’s Applause. Probably in the days of Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957) these were some of the rare films from the period that could be seen. They also were by major directors. Looking at them again, though, I don’t feel that they’re up there with the films below.

The Love Parade has the problem of dire sexual politics, the point being that while wives are naturally subservient to their husbands, a man put in the same position is entitled to be upset. That’s what happens when a court official, played by Maurice Chevalier, marries the queen of the mythical kingdom of Sylvania, played by Jeanette Macdonald in her screen debut. Moreover, we’re expected to find humor in a comic subsidiary plot where the official’s valet does a courtship duet with a maid, slapping her around a bit and apparently sexually abusing her in some fashion offscreen. Beyond that, though, there is a gaping plot hole that undermines the whole thing. The official is portrayed as nothing but a serial seducer, and yet when Sylvania is in financial difficulties, overnight he comes up with a brilliant plan to solve everything. In addition, after seemingly obsessed with sexual matters, he becomes bored with his marital position as the queen’s boy toy.

Applause displays rather clumsy camera movements that gave it cinematic flair in an era of clunky camera booths. But it simply seems to me not a very good film otherwise. Thunderbolt effortlessly runs rings around it.

Thunderbolt (dir. Josef von Sternberg)

Decades ago, when I taught the basic survey film-history course at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, one could still rent Thunderbolt in 16mm. I showed it the week we studied the coming of sound. Returning to it now, I still think it’s the greatest early Hollywood talkie that I’ve seen. Here’s a film that came directly after von Sternberg’s string of silent masterpieces (not counting, unfortunately, the lost The Case of Lena Smith), and before one of his best-known works, The Blue Angel.

I’m baffled by the fact that it has never been available on DVD or Blu-ray. Fans share dreadful copies of the old VHS release or off-air recordings. Fortunately Turner Classic Movies aired it some years ago, and we have a watchable, if occasionally glitchy, homemade DVD.

The plot bears a vague resemblance to that of Underworld. A tough crime boss, nicknamed Thunderbolt (again played by George Bancroft), learns that his mistress is secretly seeing a young man and plans to marry him. The resemblance stops there, however. In an attempt to invade the young man’s apartment and murder him, Thunderbolt is finally caught and sentenced to death. Much of the rest of the film takes place in perhaps the strangest death-row prison ever portrayed on film.

Von Sternberg treats sound as a gift, not an obstacle. He cuts from cell to cell, all beautifully lit and composed, while offscreen a seemingly endless supply of singers and instrumentalists perform everything from “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” from a black soloist to a group of singers rendering barbershop-quartet style renditions like “Sweet Adeline” to a classical group that seems to be passing through. Sometimes we see the source of the music, sometimes we don’t. The music doesn’t seem to have much to do with the dramatic action but perhaps reflects the eccentricities of the warden–Tully Marshall chewing the scenery even more than usual.

Speaking of music, the film also includes an early scene with Thunderbolt and his mistress visiting a Harlem nightclub. The prolific black actress Theresa Harris, in her first known role, sings “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” Now that’s using early sound well.

Thunderbolt isn’t quite up to the level of Underworld or Docks of New York. Fay Wray and Richard Arlen make a blander couple than Evelyn Brent and Clive Brook in the former film. Still, it’s a major work in von Sternberg’s career. Let’s hope one of the DVD/Blu-ray companies finally makes it available.

Lucky Star (dir. Frank Borzage)

I well remember the astonishment and delight of the audience at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1990 when the previously lost Lucky Star was shown in that year’s Borzage retrospective. A print had recently been discovered at the Nederlands Filmmuseum (now the EYE Film Institute Nederlands).

Lucky Star was originally released in silent and part-talkie versions. The restored print was of the silent version, which was lucky indeed. Having seen how awkward and distracting the recently restored talking sequences in Paul Fejos’s Lonesome are, one can only cringe at the thought of similar scenes being inserted into Borzage’s lovely film.

Lucky Star again pairs Charles Farrell and Janet Gaynor, who had been firmly fixed as the ideal romantic couple by 7th Heaven and Street Angel.

There can be few, if any films of this period where the romantic leading man spends most of the narrative in a wheelchair. Tim has suffered a grievous injury fighting in World War I, and he and Mary, a young farm girl, fall in love. Mary’s mother insists that there’s no future with a disabled man and forces her to agree to marry a sleazy, bullying soldier. Such prejudice against a “cripple” is the main underlying theme of the film.

The development of the plot is surprisingly leisurely. The first half consists largely of Mary’s visits to Tim and his attempts to help her overcome some of the slovenliness and petty dishonesty stemming from her family’s extreme poverty. There is no real goal or conflict until the intrusion of the rival soldier about halfway through. The charm of the two characters and the actors playing them carry the action effortlessly.

As with 7th Heaven, the studio-built sets are remarkable, in this case representing entire houses set amid rolling woodlands. (See top.) The acting is splendid as well. Farrell in particular is quite convincing as a man who is paralyzed from the waist down. One remarkable shot lasting 2 minutes and 40 seconds has him struggling to leave his wheelchair and use crutches instead before finally falling into the foreground. The framing remains steady until a reframing downward at the end.

Lucky Star is one of the films included in the 2008 box, “Murnau, Borzage and Fox.” So far that invaluable set is still available. Otherwise one can find English and French DVDs of it as imports.

Hallelujah (dir. King Vidor)

For the first time, a mainstream director (Vidor was at the top of his game after enjoying a huge hit with The Big Parade in 1925) and MGM, one of the Majors of Hollywood, acknowledged that a gripping melodrama could be just as entertaining with an all-black cast as an all-white cast. That is, entertaining to those outside the deep South, where exhibitors refused to play the film, robbing it of its chance to become profitable.

Well established as a classic of both early sound cinema and African-American cinema, Hallelujah retains its entertaining quality. It is easy from a modern perspective to dismiss it as racist or dependent on stereotypes. But I think that put in the context of 1929, the film was as progressive as one could expect in the day.

Vidor had long cherished the project and gave up his salary to get a greenlight from MGM. The crew was racially mixed, including an assistant director, Harold Garrison, who was black. More importantly, the musical director, responsible for the many musical numbers, was Eva Jessye, the first widely successful black female choral conductor. A few years later she would participate in the premiere of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts, and alongside George Gershwin, she was musical director for Porgy and Bess.

Vidor shot the exteriors in the Memphis area, hiring local black preachers to consult on the religious scenes, including the river baptism. He accepted changes from his cast when they found their dialogue not ringing true. In short, he struggled to be as authentic as he could.

The casting was done with particular care. Zeke was originally to be played by Paul Robeson, the most respected black performer of the day, but he was unavailable. Instead Daniel L. Haynes, a notable stage actor, got the part through having understudied Robeson in the original production of Showboat. Haynes gives Zeke a buoyant appeal that maintains sympathy for him despite his vulnerability to temptation. Nina Mae McKinney, also coming from a stage career, did the same for the seductress Chick.

Hallelujah does not have the technical polish of a film like Thunderbolt, to a considerable extent because Vidor chose to shoot so much of it on location. The tracking shots during the opening number, “Oh, Cotton,” are certainly impressive for a 1929 film. There is also some impressive night shooting during Zeke’s chase after the escaping Chick.

Hallelujah is available on DVD from the Warner Brothers Archive Collection. Unfortunately the company has chosen to put a boilerplate warning at the beginning that essentially brands Hallelujah as a racist film:

The films you are about to see are a product of their time. They may reflect some of the prejudices that were common in American society, especially when it came to the treatment of racial and ethnic minorities. These depictions were wrong then and they are wrong today. These films are being presented as they were originally created, because to do otherwise would be the same as claiming these prejudices never existed. While the following certainly does not represent Warner Bros.’ opinion in today’s society, these images certainly do accurately reflect a part of our history that cannot and should not be ignored.

I don’t think this description fits Hallelujah, but it certainly sets the viewer up to interpret the film as merely a regrettable document of a dark period of US history. Warner Bros. demeans the work of the filmmakers, including the African-American ones. The actors seem to have been proud of their accomplishment, as well they should be.

Sound and silence

Blackmail (dir. Alfred Hitchcock)

Long ago, when I first saw Blackmail, I thought it was a pretty mediocre, clumsy film. Luckily I have learned quite a bit about cinema since then and can appreciate Hitchcock’s clever use of sound–beyond just the famous “knife … knife … KNIFE” scene.

There’s the sequence where the blackmailer saunters into the tobacco store run by the heroine’s parents. He starts forcing her and her policeman boyfriend to pamper him with an expensive cigar and a good English breakfast. As he eats, he whistles “The Best Things in Life Are Free,” successfully annoying the boyfriend even further (above).

Earlier in this scene, Hitchcock presents a leisurely long take as the blackmailer performs an elaborate examination of said expensive cigar. His byplay generates suspense in us about whether he will get away with his tactic, as well as suspense in the father as to just when he is going to pay for that cigar.

The scene works well enough in the silent version of the film, but the little sound effects and muttered comments of the blackmailer make it a combination of tension and humor that wouldn’t come across without the sound. It also makes a nice contrast with the extended scene of the heroine in the artist’s studio. There the veiled threat of his seduction attempt and her naive reactions create a genuine suspense with no humor.

In contrast, there are passages of fast cutting that help avoid the stagey quality of much early sound cinema. The opening police raid and the later chase after the blackmailer through the British Museum’s Egyptian rooms (see bottom) both employ this tactic effectively.

By the way, I always thought that the giant pharaonic head in the shot where the blackmailer slides down a chain must have been a process shot, with a smaller head blow up for effect. Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray disc of the film, though, shows the label under the head well enough to reveal that it’s a cast of one of the giant heads of Rameses II from his temple at Abu Simbel (see bottom). Casts aren’t much in favor in most museums these days, so it’s no longer on display.

Pandora’s Box (dir. G. W. Pabst)

Fritz Lang, who has appeared quite regularly on these lists, released only The Woman in the Moon, his least interesting 1920s film, in 1929. Expressionism was over. In contrast, Pabst filled in with perhaps his most popular film, Pandora’s Box.

The film derives from a pair of Expressionist plays, Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box, by Frank Wedekind. The first play had been filmed in 1923, as Erdgeist with Asta Nielsen as Lulu, and directed by Leopold Jessner in the Expressionist style. It survives but is among the most difficult Expressionist films to see. Pabst combined the second half of Earth Spirit and the entirety of Pandora’s Box for his version.

The play and film both depend on the central character being played by someone who can simultaneously Lulu’s conflicting traits: her vivacious joy in living, her strange mix of generosity and selfishness, her egalitarian attitude toward others, and her naive amorality. American star Louise Brooks was perfectly cast, as were the supporting roles, including veteran Expressionist actor Fritz Kortner as the wealthy publisher who is keeping Lulu as his mistress at the film’s beginning.

Although the source material would lend itself to Expressionist designs, Pabst went for a more modern, streamlined look, as in Lulu’s apartment (below) and the luxurious home of Dr. Schön.

Pandora’s Box was issued on DVD by The Criterion Collection but is now out of print. We can hope for a Blu-ray version.

Wild and tame surrealism

I’m dividing the tenth slot for two very different short films that were in their own ways experimental masterpieces that had a considerable lasting influence.

Un chien andalou (dir. Luis Buñuel)

Few if any trends in cinema have been so dominated by a single film. Surrealism was still a concentrated movement in the late 1920s, before it diffused out internationally to become a permanent option for experimental filmmaking. With Salvador Dalí as scriptwriter, Buñuel managed to create a loose narrative centered around displaying constant incongruous juxtapositions and inexplicable occurrences. It also aimed to offend, with the opening eye-slitting, the attempted rape, and the cavalier treatment of the clergy.

Un chien andalou, being short and in the public domain, is widely available online and on DVDs issued by small companies. I haven’t seen the BFI’s Blu-ray of L’Age d’or and Un chien andalou, but that would seem to be the best bet for quality.

The Skeleton Dance (dir. Walt Disney, animator Ub Iwerks)

The Skeleton Dance is a much tamer film than Un chien andalou, a humorous, entertaining treatment of the disturbing subject of death. (Nevertheless, it was reportedly banned in Denmark as being too macabre.) The subject was apparently suggested to Disney by composer Carl Stalling, whom the director approached to do music for two earlier Disney films. Stalling was interested in creating films based on musical themes, and The Skeleton Dance became the first of Disney’s “Silly Symphonies” series.

Stalling eventually moved on to Warner Bros.’s animation unit, where he composed the music for two series modeled on (and parodies of) the “Silly Symphonies”: the “Merry Melodies” and the “Looney Tunes.” Thus The Skeleton Dance helped inspire three of the great animated series of the 1930s and beyond.

The cartoon has only the loosest of plots, running (much as the “Night on Bald Mountain” episode in Fantasia would) through the eerie events of a night through to the calming effects of dawn. The opening features a frightened owl (below left) and a howling dog, but the main “characters” are four skeletons that leave their graves to dance and cavort. Iwerks showed off his virtuoso skill, with the complex figures of the skeletons moving in circles so that they crossed over each other, as in the circular dance in the image above. He also uses two basic techniques of animation, stretch and squash, to turn the rigid bones into lively, pliable figures (below right).

The Skeleton Dance is included in the “Walt Disney Treasures: Silly Symphonies” DVD set, now out of print.

Compilations of Carl Stalling’s brilliantly zany (and surrealistic) music for the “Merry Melodies” and “Looney Tunes” were released on CDs as “The Carl Stalling Project” Volume 1 and Volume 2. Remarkably and deservedly, these are still in print after many years. If you do not already own these, hasten to buy yourself a belated Christmas present.

Conclusion: Acknowledging two notable events

The year saw Buster Keaton, who has figured so prominently in these lists, make his final silent feature, Spite Marriage. A pleasant film, but one which does not reach the heights of his great comedies earlier in the decade. Second, the earliest surviving film of Yasujiro Ozu, Days of Youth, dates from 1929. Although not top-ten material, it already displays his unique style. Assuming we continue this annual list, it will not be long before Ozu begins appearing on it.

There’s an ongoing controversy over versions of New Babylon. Specialist Marek Pytel has noted that a number of scenes were cut from the film after its premiere, thus making the new version impossible to synchronize with Shostakovich’s score. The missing footage having been rediscovered, Pytel has constructed a new print and synced it with a piano version of the score. His website on the restoration of the original version is here. Ian McDonald has written an extensive series (in three parts, here, here, and here) analyzing in complex detail the evidence for and against Pytel’s claims. Among those is Pytel’s statement that Trauberg told him that the initial version is the one that he and Kozintsev would consider definitive, while at other times the director said that the edited version as released is the preferred one.

Pytel also has claimed that Kozintsev and Trauberg wanted the musical score to be recorded and added to the film; he argues that the film should be run at 24 fps and used that running time in the small number of live performances that have so far been the public’s only access to his version. The very low-resolution clip from Pytel’s version that he posted on Youtube, however, shows the action to be distinctly too fast at 24 fps. Perhaps Kozintsev and Trauberg would have accepted this faster action in exchange for a musical track, but it would have been quite distracting.

The standard version on the Dutch/German DVD seems to me to be running at the correct, slower speed, with the music reasonably well synced.

Whether or not the standard version is the preferred one, it has long been the one we have, and it is quite brilliant as it stands. Being episodic, it does not show signs of being incomplete, though obviously one would wish to see the extra footage in the Pytel version to be able to judge.

Our friend and colleague Ian Christie, noted historian of Russian and Soviet cinema, discusses the historical context of New Babylon in a short video essay.

Blackmail.

Beach blanket ballads: SUN & SEA (MARINA)

Sun & Sea (Marina) (Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė, 2019).

DB here:

Excitement, shock, tension, maudlin sentiment–these and other emotional qualities are pretty common in artworks. But how often do we get what I’m forced to call anxious languor? That seems to me the dominant expressive quality of the remarkable Lithuanian opera Sun & Sea (Marina), which won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation at the Venice Biennale.

It’s not a film, but having read about it before going to the Mostra, I was keen to see it. Kristin and I were not disappointed. It’s the work of director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, writer Vaiva Grainytė, and composer Lina Lapelytė. You can watch extracts here and here and here.

Video clips, or indeed a full-length record, can’t capture this unique spectacle. And of course it set me thinking about film.

Duet in the sun

Sun & Sea: Marina portrays a group of people at the beach. Instead of being mounted on a stage, the action, such as it is, takes place on a ground floor of a warehouse. You view the ensemble from catwalks above. On the sand below are pastel beach blankets, personal belongings, and some litter. Thirteen singers and some civilians lie reading or snoozing or listening to cellphones. A woman deals out Tarot cards. There’s a little boy playing in the sand, dudes tossing a frisbee or playing badminton, and occasionally a couple’s dog needs walking. The dog barks from time to time.

The piece lasts about seventy minutes, recycled so you can enter at any point. At the Biennale, it was initially open only one day a week, but later you could attend on either Wednesday or Saturday. The queue wasn’t impossible; I think we waited about half an hour.

The looped nature of the presentation works against there being a plot, and there’s scarcely any characterization. The libretto identifies the Wealthy Mommy, the Volcano Couple, the Workaholic, the 3D Sisters (twins), and others, but when you’re watching it, you’re much more aware that this is about particular bodies in a specific space.

The music, in the lyrical minimalist vein, consists mostly of arias, characters’ soliloquies backed up choral passages. There’s an organ ostinato recalling Philip Glass and tunes that reminded me of the lilting faux-naīveté of Meredith Monk. The rhythm is alternately solemn and bouncy, the phrases are brief, and the mood of the whole score seems summed up in the soaring Chanson of Too Much Sun:

My eyelids are heavy,/ My head is dizzy,/ Light and empty body./ There’s no water left in the bottle.

Some of the arias, like this one, report thoughts caught in the moment. The first and last songs are Sunscreen Bossa Novas, sung by a middle-aged woman worrying about protecting her skin. Another woman complains about dogshit and spilled beer in the sand. One of the most moving passages is the Chanson of Admiration, a breathy soprano solo:

What a sky, just look, so clear!/ Not a single cloud,/ What is there?–seagulls or terns?/ I can never tell./ O la vida/ La vida…

Other characters provide dramatic monologues. The Workaholic sings the Song of Exhaustion, an admission that even relaxing, he can’t slow down. (“My colleagues will look down on me. . . . I’ll become a loser in my own eyes.”) Still others tell stories. A woman recalls her husband’s death while swimming with his girlfriend. A house guest learns that his host has a brain tumor. A couple talks about catching an early-morning flight. Most abstractly, the Philosopher thinks about globalization: how strange to play chess (a game of Indian origin) on the beach while eating dates from Iran and wearing a swimsuit made in China.

Other characters provide dramatic monologues. The Workaholic sings the Song of Exhaustion, an admission that even relaxing, he can’t slow down. (“My colleagues will look down on me. . . . I’ll become a loser in my own eyes.”) Still others tell stories. A woman recalls her husband’s death while swimming with his girlfriend. A house guest learns that his host has a brain tumor. A couple talks about catching an early-morning flight. Most abstractly, the Philosopher thinks about globalization: how strange to play chess (a game of Indian origin) on the beach while eating dates from Iran and wearing a swimsuit made in China.

Sun & Sea (Marina) has been considered a commentary about our poisoning the planet, and the booklet included with the LP of the score includes essays about climate change. But the opera as staged invokes the crisis obliquely and poetically. One passage notes that the seasons are out of joint at Grandma’s farmhouse, with frost and snow in May and Easter weather during Christmas. It’s presented not as a warning but as a puzzling development. A recurring line in the songs is “Not a single climatologist predicted/ A scenario like this,” and it’s applied to love affairs as well as volcanic eruptions. The crises of the Anthropocene era are refracted through personal relationships.

Environmental degradation is registered through the sensibility of drowsy vacationers. The twin sisters are distressed to learn that coral and fish will perish, but they console themselves that a 3D printer will produce enduring copies of everything, including the girls themselves. (“3D Me lives forever.”) Even pollution right under your nose is filtered through the dazzling torpor of a day at the beach. One of the loveliest songs invites us to imagine that the sea is acquiring new beauty.

Rose-colored dresses flutter;/ Jellyfish dance along in pairs–/ With emerald-colored bags,/ Bottles and red bottle-caps./ O the sea never had so much color!

In all, though you might register some perturbations in the ecosystem, you come away from lolling on the sand feeling pretty good.

After vacation,/ Your hair shines,/ Your eyes glitter,/ Everything is fine.

Eisenstein on the beach

What about cinema? Seeing something so resolutely presentational makes you think about what film can’t do. The online videos only hint at the decentered, dispersed quality of the opera. Some of the action takes place directly under the catwalks, so you can’t take in the ensemble at a single glance. We had to move around to get a sense of what had been happening underneath us.

Just as important, nobody in the audience is significantly closer to the stage than anybody else. Cinema of course has what Noël Carroll has called variable framing, the ability to change the scale of the material in the image (through cutting, camera movement, zooming, optical effects, digital postproduction). Even in proscenium theatre, the people in the orchestra see more details than those in the balcony. But Sun & Sea (Marina) keeps everybody pretty much at the same distance from the spectacle. We can fixate on some figures rather than others, and we can enlarge them artificially via the zoom on our cellphones, but the naked eye has to take in the whole thing at once, all the time. And even that’s not really the whole thing.

The sense of dispersed action is strengthened by the surround-sound speakers. They delocalize each voice. You have to search the array of bodies to find the soloist, and when a song is tossed from singer to singer it scrambles your attention. This might remind a cinéphile of Jacques Tati’s compositional strategies, particularly in Play Time, where long shots coax us to scan the image to find a sound’s source. But at least Tati had a more restrictive frame. Sun & Sea (Marina) plants us in a three-dimensional field with only partial access to the entire scene.

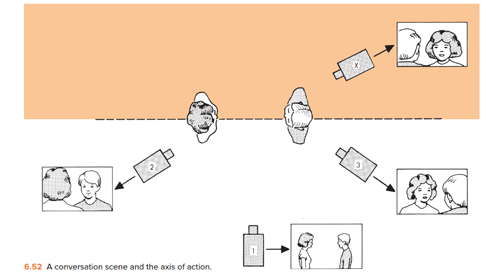

That access is, of course, a very unusual one. When I was first studying classic continuity editing, with the 180-degree rule and matches on action and all the rest, I wondered: Would that system work if the camera were pointing straight down at the actors? That is, what if we constructed a whole story from variants of the bird’s-eye view we use to diagram spatial layouts? Instead of this:

We’d have movies with shots like this.

We’d apparently lose the eyeline match, at least! We’d also have to distinguish characters in unusual ways, by hats and hairstyles and maybe boutonnieres. But I was assuming a drama in which people moved around on foot and had face-to-face encounters. Sun & Sea (Marina) suggests that another way to build a vertically viewed spectacle is to show people sprawled out on belly, back, or side–postures motivated by the beach setting.

Then perhaps we could, through editing, create “reverse angles” from straight down. Or couldn’t we?

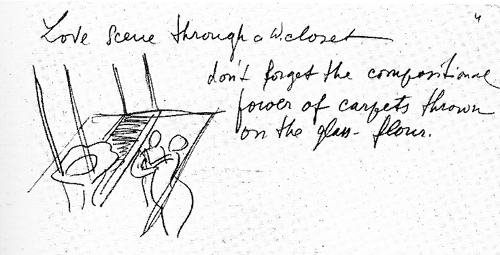

Actually, as usual, Eisenstein was there ahead of us, in his plans for The Glass House, a film set in a skyscraper made of glass. The transparent walls would let us see what’s happening next door, while the floors would create a stacked space, presenting actions from more or less straight down. Naughty as he was, he even conceived a “Love scene through a water closet.”

In one note, he called the film’s view “A Hovering Space”–not a bad description of what we see in Sun & Sea (Marina).

I’m still thinking about this remarkable piece of work, about the anxious languor it projects and its ways of building a scattered scene out of microactions. But I’m also enjoying remembering the sheer sensuous pleasure of it. I hope that somehow I get to see it again. I hope you can too.

Our visit to the Biennale was made possible by the generous invitation of Peter Cowie, Savina Neirotti, Paolo Baratta, and Alberto Barbera. As ever, we appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich. Michael Philips of the Chicago Tribune and Keith Simanton, Senior Film Editor and Content Manager of IMDB, accompanied us to the show and proved fine company.

There’s a very informative interview with the artists (who have been friends since childhood) here at BarbART. It includes footage from their earlier collaboration, Have a Good Day! Background on the artists can be found at Neon Realism. The score is available as an LP. It includes a custom code for downloading an mp3 file. Beware: Many earworms wriggle within.

Of course Sun & Sea (Marina) reminds you of another Tati masterpiece, M. Hulot’s Holiday. Kristin long ago wrote a careful analysis of that film with a title I might have borrowed for this: “Boredom at the Beach.” It’s in her collection Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis. Also on Tati: Watch for Malcolm Turvey’s excellent forthcoming study Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism.

The diagram of the 180-degree editing system comes from Film Art: An Introduction. Photos in this entry by DB.

P.S. 15 September 2021: Sun & Sea (Marina) is coming to the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019).

Annette Michelson and the Post-Revolutionary Project

The All-Union Creative Conference of Workers in Soviet Cinematography, 1935. First row: V. I. Pudovkin, Sergei Eisenstein, Edward Tissé, and Alexander Dovzhenko. Second row Yuri Raisman, Annette Michelson, et al.

DB here:

Annette Michelson, a pioneering figure in studying cinema, died nearly a year ago, age 95. She enjoyed a distinguished career as an art critic, lecturer, editor, and professor of film. Her influence went beyond her own writings; as an editor she supported now-classic works like P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film and the English translation of Noël Burch’s Theory of Film Practice. She was a tireless advocate for contemporary avant-garde filmmakers as well as “difficult” films, from the works of Godard and Vertov to 2001. Upon her retirement, her students and colleagues published a festschrift, Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson. Many of her essays were collected in a volume called, poetically enough, On the Eve of the Future.

One of Annette’s major accomplishments was co-founding the journal October in 1976. So it’s entirely appropriate that the newest issue is devoted to essays and memoirs celebrating her accomplishments. Edited by Rachel Churner and Malcolm Turvey, it gathers many exceptionally valuable items. It makes available two little-known pieces by Annette: her important essay from 1969, “Art and the Structuralist Perspective,” and a later reflection on Picabia and the cinema. There’s also a wide-ranging conversation with Edward Dimendberg.

One of Annette’s major accomplishments was co-founding the journal October in 1976. So it’s entirely appropriate that the newest issue is devoted to essays and memoirs celebrating her accomplishments. Edited by Rachel Churner and Malcolm Turvey, it gathers many exceptionally valuable items. It makes available two little-known pieces by Annette: her important essay from 1969, “Art and the Structuralist Perspective,” and a later reflection on Picabia and the cinema. There’s also a wide-ranging conversation with Edward Dimendberg.

Yve-Alain Bois analyzes her early, Paris-based art reviews and journalism, including many extracts and printing in toto her very first piece in the New York Herald Tribune. (The first sentence uses one of her favorite words: radical.) There are lengthy tributes from students, colleagues, artists, filmmakers (Gitai, Rainer, Ken Jacobs). Babette Mangolte contributes portraits and some images of Annette’s legendary loft. In all, this is a monumental undertaking and essential for anyone who wants to understand Michelson’s unique stance at the crossroads of film, visual art, critical theory, and Continental philosophy.

The recollections go far toward humanizing a figure who was for many of us a forbidding presence. I met Annette in late 1972, when I interviewed for a job at New York University. She scared me. (I wasn’t alone.) A few years later, when I did a visiting stint there during Noël Carroll’s leave, she proved much less intimidating. Maybe I was less skittish, or she was more mellow. She took a shine to Kristin, and we developed a mutually teasing friendship. I enjoyed her unusual habits, such as playing Berg on her turntable at ear-splitting pitch.

The last time I saw her was in March 2006. She had recently moved from her loft to a new place in midtown, and she was surrounded by boxes of books. Though somewhat frail, she insisted we go out for lunch. We talked about Eisenstein, Godard, and the history of the Anthology Film Archive.

Years before, feeling frisky during a sabbatical, I sent some friends the photo you see above, accompanied by the following text.

From Moscow Weekly (7 November 1993)

INTERACTION OF SOVIET MONTAGE CINEMA AND NEW AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE CONFIRMED BY NEWLY DISCOVERED PHOTO

Glasnost’ has brought many unexpected revelations, but few have been so striking as the proof that there existed an objective relationship between revolutionary Soviet filmmaking and the New York avant-garde cinema of the 1960s.

Until now, a continuity between the experimental Montage directors and the “New American Cinema” of Stan Brakhage and Hollis Frampton seemed an academic flight of fantasy. Many scholars had posited such an affiliation, but hard evidence had been lacking. What could the Marxist cinema of the 1920s have offered the apolitical formalists of the post-Beat generation?

Plenty, it now turns out.

While rummaging in old photographs at Goskino, a young Russian filmmaker, Yevgenii Zhirmunsky, found a crumpled envelope labeled “Conference 1935: Miscellaneous.” The notation referred to the notorious 1935 All-Union Conference of Soviet Cinematography, at which the major directors capitulated to Stalinist demands for Socialist Realism.

Highlight of the Conference was the ritual humiliation of Eisenstein, the most celebrated Soviet director, and the elevation of the Vasilievs’ Chapayev, soon to become the prototype of Socialist Realism.

Zhirmunsky discovered that the envelope held several snapshots of cineastes dozing through papers or denouncing their comrades from the lectern. Most informative, however, was an original version of the famous photo of the premiere directors–Eisenstein, Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Pudovkin, and others. Zhirmunsky was startled to discover that versions of this photo, reproduced in both East and West for sixty years, had eliminated a key participant at the Conference.

Airbrushing and photomontage were common in the Stalin era. When a political figure fell from favor, he was often deleted from all photographs. Sometimes other figures were added in this Bolshevik version of “virtual reality.”

Now, thanks to Zhirmunsky’s discovery, film scholars know that an influential figure of the New York avant-garde attended the 1935 Conference. Professor Annette Michelson, critic, teacher, and tireless promoter of the New American Cinema, was present and, to judge by the photo, became a central participant in the events taking place.

The photo shows her wearing a loose sweater and blue jeans, characteristic garb of New York bohemians. While a woman seems out of place amid the gabardine-suited directors, Michelson’s intensely serious expression suggests that she followed the debates with keen interest. Her proximity to Eisenstein, and his almost adoring expression, suggests a special affinity between them.

Zhirmunsky surmises that Michelson, long an advocate of the historical continuity of the Soviet avant-garde and the New American film, conveyed to her Manhattan contemporaries the essential insights of the revolutionary directors. This would provide the “missing link” long sought for between the two movements.

Not surprisingly, Michelson has been the most outspoken advocate of the continuity of the two traditions.

Zhirmunsky surmises that Michelson’s “formalism” was anathema to authorities and led to her being deleted from the photo.

The photo is to be published in the US journal October this fall, prefaced by an essay by Zhirmunsky detailing the facts behind his extraordinary discovery.

And he persists in his quest for glasnost’ treasures. “I’ve found some new film footage of the taking of the Winter Palace,” he remarks. “There’s a chap in one shot who seems to be Fredric Jameson.”

My friends assured me that Annette would enjoy it. Apparently she did, because she responded in kind.

Dear Professor David Bordwell,

Professor Annette Michelson asks me, in her present absence from New York, to answer your most kind forwarding to her and to express her profound thanks. I communicated to her your message by telephone last night in California where she was delivering a keynote address at a Maya Deren conference and speaking, as fate would have it, on the Deren-Eisenstein relation.

You can, of course, imagine the extremely great gratification she feels about E. Zhirmunsky’s* discovery. This is a true resurrection that will heal an error and correct a wound maintained for more than a half century! Well, once again, we see that truly Truth is the daughter of Time. Of course you and I know that Professor Michelson, with her usual modesty, rejoices not for herself alone, but for Film History and for all those, who like yourself, labor to its greatest glory.

Professor Michelson found most interesting, of course, your hermeneutics of the original version. She suggested, however, that I communicate to you (although not for publication) her personal interpretation, based, of course, on her living memory of the fateful occasion. You will have noticed that everyone in this picture is smiling or laughing; everyone but Pudovkin, who seems to be explaining something and Professor Michelson (who was , of course at that time, far from being a tenured full Professor, in fact, she had not yet begun the graduate studies from which she … but that is another story).

The reason for this is that Professor Michelson had just challenged the famous director and actor on a point involving the famous debate between himself and Comrade (this is, of course, old style way of speaking) Eisenstein. Perhaps you have some memory of this about building blocks or opposing forces?

Such, it would appear, was the strength of Professor’s challenge coming, in addition to boot, from an American young girl, that the general reaction – even from Donskoi and Bek-Nazarov – was “It appears like the Amerikanska has you, there, Comrade! What have you got to say for yourself now?”

And while Eisenstein is certainly admiring of this daring young female who defends his more correct Hegelian position, he is also clearly amused by Pudovkin’s being flustered by her so that he can hardly defend himself.

For everyone but the two protagonists, the event was a subject of amazement and amusement that lasted far into the Moscow night and beyond, but as you can see from the transcripts of the Conference, it was erased from the record. Perhaps one day, Zhirmunsky or some bold graduate student will turn up the handwritten transcript of this important vis à vis. In the meantime, all heartfelt thanks to you, Professor Bordwell, in Professor Michelson’s name,

Yours sincerely,

R.I. Durakova, Research Assistant, The Post-Revolutionary Project

*Do you have his patronymic, since we would like to write and thank him?

I learned from this that even a sophomoric jape can help cement a friendship. Stuart Liebman, one of her most devoted friends, tells me that Annette continued to enjoy that picture in her final days. Her sense of humor is only one of the many things that make me glad to have known her.

The group portrait is discussed in Annette Michelson, “From Magician to Epistemologist: Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera,” reprinted in October (162 (Fall 2017), 113-132. The essay was first published in Artforum in 1972. She notes that Jay Leyda suggested that the photo might have been misdated and was taken later than 1935.

For discussions of Soviet creative retouching of photographs, see David King’s The Commissar Vanishes.

Thanks to Malcolm Turvey for conversations around this issue of October, which also includes an extract from my book Making Meaning.

Doctored photograph of the 1935 group portrait, with Michelson removed and a generic comrade substituted.