Archive for the 'Directors: Sturges' Category

How he (mostly) got away with it: Matthew H. Bernstein on Preston Sturges

DB here:

Matthew H. Bernstein is a long-time friend and a superb scholar. His biography of Walter Wanger has become a classic of Hollywood business history, and his many books and articles have refined our sense of American cinema. When we learned of his research into Sturges (a favorite of this blog), we were happy to propose that he do a guest entry. Here’s the lively, trailblazing result.

How should films portray sex and marriage? Hollywood’s Production Code, established in 1930, set forth some definite ideas.

Sex

The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing. . . .

Scenes of Passion

They should not be introduced when not essential to the plot.

Excessive and lustful kissing, lustful embraces, suggestive postures and gestures, are not to be shown . . .

Seduction or Rape

They should never be more than suggested, and only when essential for the plot, and even then never shown by explicit method.

They are never the proper subject for comedy.

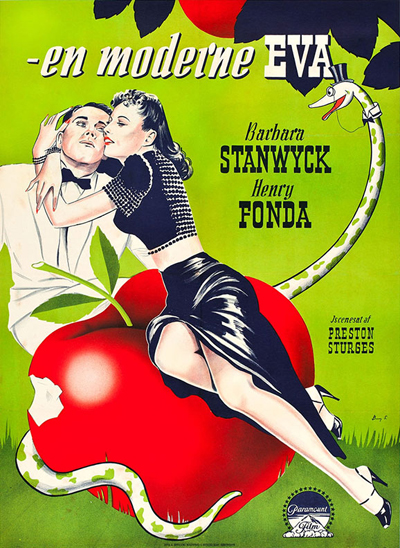

Those of us who savor Preston Sturges’s great romantic comedies of the 1940s—The Lady Eve (1940), The Palm Beach Story (1942) and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944)—admire them in part for their violation of just about all these tenets. They are full of “suggestive postures” like the lengthy chaise longue scene in The Lady Eve. Their central topic is often the seduction of men by women (The Lady Eve, The Palm Beach Story and arguably Miracle). References to extra-marital sex, contemplated or accomplished, abound. And all three films ridicule “the sanctity of the institution of marriage” into the ground. Film critic Elliot Rubinstein once observed, “If Sturges’s scenarios don’t quite invade the province of the flatly censorable, they surely assault the border outposts, and some of the lines escalate the assault into bombardment.”

The Production Code Administration, on paper and in practice, was particularly obsessed with regulating the depiction of female sexuality on screen. Yet Sturges’ attacks on conventional morality are launched by heroines: con artist/card sharp Jean/Eve (Barbara Stanwyck) in The Lady Eve, the hard-headed Gerry Jeffers (Claudette Colbert) in The Palm Beach Story and the naïve man-bait Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. They are all variants of what Kathleen Rowe has called the “unruly woman,” characters who create “disorder by dominating, or trying to dominate, men,” and being “unable or unwilling” to stay in a woman’s traditional place. Mary Astor’s much-married Princess Centimilia/Maude in The Palm Beach Story deserves an honorable mention here too.

True, by each film’s conclusion, the Sturges heroine agrees to get or stay married. She fulfills the conventions of romantic comedy and the stipulations of the PCA. Yet in each film the path to a proper end looks so much like a roller-coaster ride that the significance and sanctity of marriage come to seem ridiculous.

How did Sturges get away with so much? A look behind the scenes at the negotiations around The Lady Eve can help us understand his strategies. It also shows that the Code was more flexible and fallible than we often realize.

Convolutions in the Code

Sturges had one advantage at the outset. He worked in a genre that was already testing the limits of the Code. Granted, the PCA in 1934 aimed to regulate film content in every genre. None, however, flaunted, even parodied, the strictures of the Code more thoroughly than screwball comedy did. Rubinstein puts it well: “The very style of screwball, the complexity and inventiveness and wit of its detours around certain facts of certain lives, the force of its attack on the very pieties it is pledged to sustain, cannot be explained without recognition of the censors. Screwball comedy is censored comedy.“

By the end of the 1930s, filmmakers were pushing hard against censorship. Romantic comedies were growing more risqué by the month, as shown by 1940 releases like My Little Chickadee, The Philadelphia Story, The Road to Singapore, Too Many Husbands, The Primrose Path, Strange Cargo, and most especially, This Thing Called Love. A sort of arms race took place, and Sturges, emerging as a writer-director in 1940, benefited from this escalation.

Just as important is a fact that many fans of Hollywood still don’t realize. We like to think that daring filmmakers were charging boldly against an iron wall, with chief censor Joseph Breen and his associates setting forth implacable demands. But the administration of the Code was not a mechanical, totalitarian affair. It was most often a matter of negotiation.

Releasing Hollywood’s product, even risqué films, benefited all parties involved. If the Code were enforced with absolute rigidity, the industry would suffer. Some films would have to be abandoned. Then urban audiences would have found the safely released product pallid, and critics would have complained about bland output. Then as now, edginess sold, and at least some audiences were eager for it.

Accordingly, Breen and co. recognized that the Code could not be applied ruthlessly. Indeed, historians Lea Jacobs, Richard Maltby and Ruth Vasey have shown that the PCA, like its forerunner the Studio Relations Committee, often helped filmmakers find ways around the most stringent policy demands. Through a give-and-take, censors and filmmakers could settle on scenes and lines of dialogue that could avoid public outcry. No one flaunted and taunted the PCA as well as Sturges, yet Breen and co. often helped him find ways of rendering suggestive situations without baldly transgressing the Code.

One typical filmmaker/PCA tactic that favored Sturges was an appeal to ambiguity. Far from being inflexible, the staff recognized that not every viewer picked up on a lewd line or suggestive situation. Some viewers would find no innuendo in a sexually-charged scene. (The 1940s critic Parker Tyler referred to this as “the Morality of the Single Instance.”) For example, in The Lady Eve, there’s a fade-out from Charles’s and Jean’s passionate embrace in the bow of the ship at night to the fade in of the ship’s prow slicing through the ocean the next morning.

That passage would suggest to the naïve viewer that they kissed for a while and went to their cabins separately. After all, in the morning we find Jean getting dressed in her stateroom and talking with her father. Then we see Charles on deck alone, waiting for Jean.

But the sophisticated viewer would understand that the earlier fade-out indicated what Joseph Breen routinely called “a sex affair.” (The ocean spray on the fade-in could be seen as a very subtle extra touch.) Crucially, Jean’s later statement to Hopsy after she is unmasked as a cardsharp sustains both readings. “I’m glad you got the picture this morning instead of last night, if that means anything to you . . . it should.” When self-regulation was well-calibrated—and this was a moment-to- moment, scene-by-sceene, film-by-film achievement—there was wiggle-room that would let innocent viewers remain innocent while letting sophisticated viewers feel sophisticated.

Apart from the increasing eroticism in screwball comedy and the willingness of the PCA to work with filmmakers to allow double layers of meaning, Sturges benefited from good timing. During this period, Breen grew more permissive in his application of the Code. He never explained why, but the late-1930s bombardment of questionable material was probably one cause. Breen was pretty exhausted after seven years of trying to accommodate the filmmakers’ increasingly outré ideas. He was so tired that he temporarily resigned in Spring 1941.

Sturges’ circumvention of the Code also depended on his personal qualities. Clearly he was a persuasive negotiator. The PCA correspondence shows Breen and his successor, Geoffrey Shurlock, rescinding countless directives they initially gave him to eliminate dialogue lines or bits of action. It’s likely that the PCA admired Sturges’ comic gifts and thus gave him greater room to maneuver than other directors enjoyed. (Much the same thing happened when the Studio Relations Committee had given leeway to Ernst Lubitsch prior to 1934.) Sturges also employed a tactic of overkill. In his scripts and in the scenes as finally staged and shot, he created so many potential infractions of the Code that to challenge each one would reduce the film to rubble, or reduce Breen and co. to stress-induced madness.

Still, Sturges played the PCA game. His convoluted plots stuck to the letter of the Code, always finally coming down on the side of pure romance and happy marriage. But they wreaked havoc with its spirit—often with the PCA’s sanction. By the premiere of The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Sturges was relentlessly mocking the PCA’s regulations. It’s likely, I think, that the PCA was for the most part in on the joke.

After negotiations, which grew more elaborate with each title, each Sturges romantic comedy received a seal. The films made it through partly because of the PCA’s quixotic mandate, partly because the Code’s requirements had been loosened, and partly because of Sturges’ extraordinary skill in exploiting the Code. These are the crucial reasons Sturges got away with it. Along with his prolific comedic imagination, he was often aided by the very body that was supposed to be censoring him.

Once the Sturges film was released, the PCA staffers could wearily pat themselves on the back for a job well done. Yet critics’ reviews, complaints from state censor boards, and letters of protest from ordinary viewers indicate that the agency often badly misjudged how the films’ moral tone would be received. The PCA’s dual mandate—to try to give filmmakers the maximum freedom to create risqué situations but at the same time to uphold the Code–was a tightrope walk. With Sturges and other filmmakers, the agency lost its balance. Sometimes the PCA didn’t diminish the sexual dimensions enough, and sometimes the agency did not even notice elements that could give offense.

There were signs already, in the reaction to the 1940 burst of sexier films like The Primrose Path and This Thing Called Love. Local informants had asked MPPDA attorney Charles C. Pettijohn, “Doesn’t Mr. Hays have any influence with the producers any more, and has that fellow Breen out there killed himself or has he just been compelled to walk the gangplank?” Unlike the PCA staff, who had worked day by day to tone down an audacious script and had faced the charms of a persuasive filmmaker, local censorship boards reacted solely to a finished Sturges film. They merely saw what was on the screen. Many did not like what they saw.

Up the Amazon for a year

The PCA correspondence concerning The Lady Eve is surprisingly brief. Before the film was completed and a seal was granted, Breen sent only two letters to Luigi Luraschi, Paramount’s liaison on censorship. They strikingly illustrate how cooperative Breen could be when it came to scenes regarding illicit sex.

When he read Sturges’s first complete script of 7 October 1940, Breen had objections to many “questionable lines of dialogue.” Breen warned Sturges and Luraschi against anything “suggestive” in the scene between Muggsy and Lulu as they say their farewells before departing the expedition. In this brief exchange, Mugsy stiffly tells her “So long, Lulu…I’ll send you a post card” as she demurely (looking down) places a lei over his neck. This brief exchange directly undercuts Hopsy’s just-spoken, high-minded farewell to the Professor: “This is the way I’d like to spend all my time…in the company of men like yourselves…in the pursuit of knowledge.”

While it’s difficult to imagine Muggsy as a sexual partner to anyone, the woman’s downcast face and her gift of a lei could be seen to suggest her heartbreak.

Jean’s later, rapid-fire description of Hopsy’s many female admirers in the Main Dining Room of the S.S. Southern Queen originally contained comments about women who were “a little flat in the front” or “a little flat behind. ” These were cut because they were too physiologically specific about the female form. We hardly miss them, as Jean was permitted to deliver plenty of color commentary, as she detailed the women’s futile attempts to attract Hopsy’s attention.

However, Breen wrote the word “in” alongside certain demands he had made for eliminations in his 9 October letter, indicating that Sturges and Luraschi had persuaded him to relent. For example, Breen eventually accepted this exchange from Jean and Charles’s first evening together. Charles has suggested they go dancing:

Jean: Don’t you think we ought to go to bed?

Charles (after a pause): You’re certainly a funny girl for anyone to meet who’s just been up the Amazon for a year.

Jean: (after a pause): Good thing you weren’t up there two years.

Breen’s next letter (21 October) on Sturges’s revised script expressed satisfaction with all the changes made, noting that Jean’s line about heading to bed “will be delivered without any suggestive inference, or reaction.”

In the finished film, there is nothing arch about Stanwyck’s thoughtful, almost parental delivery of the first line, spoken as she looks straight ahead and then looks down to stub out her cigarette before she turns to face Charles. Likewise, her delivery of the second line is wry and mildly mocking yet almost compassionate. Still, the connotation remains that Jean is suggesting they sleep together. Instead, the couple proceeds to Charles’s cabin to meet his snake Emma.

Breen was particularly concerned about other allusive dialogue. At the Pikes’ party, Sir Alfred (Eric Blore) explains to Charles a fictionalized version of Jean’s family history which resulted in the existence of two sisters, one a lady, one a cardsharp. (Sir Alfred will later describe this as “Cecilia or the Coachman’s daughter, a gaslight melodrama.”) Breen insisted that Sir Alfred’s tale include a line indicating that Jean’s mother divorced her elderly earl before taking up with the groom “Handsome Harry” and giving birth to Jean. That way Jean’s birth would not seem illegitimate. Sturges obliged. Yet he somehow persuaded Breen to retain this later portion of the Alfred-Charles exchange, also alluding to an adulterous affair.

Charles: They [Jean and Eve] look exactly alike!

Sir Alfred: We must close our minds to that fact…as it brings up the dreadful and thoroughly unfounded suspicion that we must carry to our tombs, you understand…as it is absolutely untenable…that the coachman, in both instances…need I say more?

Why did Breen let Sturges keep in this suggestion that Handsome Harry was the biological father of both sisters, perhaps as the result of adulterous affairs? It is hard to say. True, the offending line concerns a “suspicion” voiced by Sir Alfred, rather than a fact. But Charles immediately affirms its likelihood: “But he did, I mean, he was, I mean…” before being shushed for the nth time by Sir Alfred. Here again, Breen consented to Sturges’s use of questionable material.

Breen’s greatest objection in his initial letter concerned pp. 70-74 of the first submitted script, which suggested “a sex affair.” “Inasmuch as this is treated without the proper compensating moral values, it is in violation of the Production Code, and will have to be eliminated entirely from your finished picture.”

The offending pages outlined a scene between Charles and Jean set on the deck of Jean’s cabin at the end of their first evening together. Just previously, Jean has caught Charles and her father the Colonel (Charles Coburn) playing double or nothing. Charles would then be called away to receive from the ship’s purser the incriminating photo of Jean, the Colonel and Gerald. Charles would then return to the gaming room table and the dialogue exchange with Jean about all women being adventuresses. Then Charles would ask Jean if they can go down to her cabin. There, Charles lights Jean’s cigarette; he “struggles to say something” but Jean tells him, “Kiss me,” and he obeys. (“He crushes her in his arms” as she “sinks back against the chaise longue.”) The film would then cut to a shot of the rail of Jean’s deck and of “the moonlit water beyond. A lighted cigarette arcs over the rail and down into the water. FADE OUT.”

This version presents Charles sleeping with Jean even though he knows from the purser’s photograph that she’s a cardsharp. As Brian Henderson notes, this arrangement of events would make Charles a cad, far worse than the hypocritical prig that he is in the finished film. Sturges eventually solved the problem by having Charles learn of Jean’s duplicity on the morning of their third day together at sea. But before Sturges made this change, Breen’s October 9 letter directed that Charles could not speak the line about going down to her cabin; that the scene could not play out on Jean’s private deck; and that “it would be better to have the embrace with the couple standing up.” The shot of the cigarette thrown over the railing also “should be omitted, on account of its connotations.”

In response, Sturges watered down the offending scene of passion and relocated it to the bow of the ship, where (in a reworking of a scene he had always envisioned) Charles recites his “I’ve always loved you” speech and they eventually embrace as the scene fades out. This created the PCA-approved ambiguity about what transpired sexually between them.

Here, Sturges’s solution to a problem of plot and characterization went hand in hand with the double-meaning practices of the Production Code. Sturges must have written the passionate private deck scene knowing full well that Breen would demand its elimination or transposition. His immediate agreement to revise it was likely a bargaining ploy to earn Breen’s goodwill to bank against other PCA objections.

When Sturges cut the cabin deck setting and the prone postures of pp. 70-74 from the first submitted script, he also saved a crucial part of Jean and Charles’s penultimate exchange as they enter Jean’s cabin.

Charles: Will you forgive me?

Jean: For what? Oh, you mean…on the boat…the question is, will you forgive me?

Although Breen accurately predicted that this bit of dialogue would “probably be acceptable” if the earlier scene “is cleaned up,” for now, Breen stated that their exchange had to be cut “by reason of its reference to the aforementioned sex affair.” In other words, Breen, not unreasonably, read Jean and Charles’s dialogue as referring only to their sleeping together, rather than to everything that transpired between them on the S.S. Southern Queen, including Jean’s duplicity and Charles’s narrow-mindedness. Forgiveness is of course a key issue in the drama of The Lady Eve.

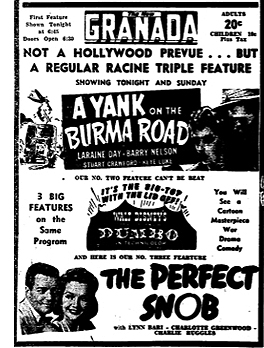

Hix Nix Sexy Pix

The MPPDA issued its seal on 26 December 1940. Released in mid-March 1941, The Lady Eve passed the censors without cuts in Chicago and the states of Massachusetts, New York and Virginia. However, Kansas, Maryland, Ohio and Pennsylvania were a completely different story.

Some local censors demanded deletions of elements Breen had highlighted. Ohio and other localities objected to Sir Alfred’s dialogue about the fantasy fatherhood of Jean and Eve (“as it is utterly untenable that the coachman in both instances. . . .”). But most of the eliminations concerned elements Breen and his team had not commented upon. Among these were (again for Ohio, initially) Sir Alfred’s summary recap of the tale to Jean the next morning: “So I filled him full of handsome coachmen, elderly Earls, — young wives, and the two little girls who looked exactly alike.”

Other targets were Jean’s wisecracks. When Jean and Charles return from her stateroom after changing her shoes, the Colonel archly comments, “Well, you certainly took long enough to come back in the same outfit.” Jean’s reply–“I’m lucky to have this on. Mr. Pike has been up a river for a year”—offended Pennsylvania. Ohio objected to Jean’s comment, “That’s a new one, isn’t it?”, when Charles invites her into his cabin to see Emma.

Yet another instance concerned Charles’s exchange with Eve during their wedding night train ride. He is asking about her previous marriage to Angus.

Charles: When they brought you back, it was before nightfall, I trust.

Jean: Oh, no.

Charles: You were out all night?

Jean: Oh, my dear, it took them weeks to find us. You see, we’d make up different names at the different inns we stayed at.

Though Jean and Angus were married, the implication of using false names at a hotel (which Sturges would recycle for Trudy and her unknown husband in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek) was the deal-breaker for Ohio. Of course, one possible connotation of Eve’s many pre-Charles couplings is that not all of them were marriages. (If they were, this imaginary Eve is an early version of the Princess in The Palm Beach Story, another figure who satirizes conventional marriage.) Yet Breen’s only comments on this scene concerned Eve’s nightgown and particularly the scene’s blocking—that Eve’s revelations of her previous marriages occur away from the bed and that the bed be deemphasized throughout the scene.

Sturges must have made the case that there was no room to have the actors sit elsewhere. Meanwhile, Breen was distracted from what Jean was saying by where she was when she said it.

Local censors were most keenly opposed to two other scenes that Breen had ignored. Both take place in Jean’s stateroom.

In the first, Charles replaces Jean’s broken shoe. In one twenty-second two-shot, he kneels down to slip the shoe on her foot; looks over her foot and slowly looks up her leg all the way to her face; expresses his hope that he didn’t hurt her when she tripped him in the dining room; and then on his way to looking down at her leg and foot again, pauses momentarily but very definitely, on her décolletage. Then he looks back up at her again. There is no dialogue to distract the viewer from what Charles is looking at.

Oddly, no censors objected to this very suggestive shot; instead they focused on what ensued. Ohio, Kansas, and Maryland joined Pennsylvania in demanding the elimination of what the last described as the “semi close-up view where [Charles] allows his eyes to pass up and down over her.” This was a quick POV series of shots in which (1) Charles struggles to look at Jean; (2) Jean appears blurry and asks Charles if he’s all right; and (3) Charles, after swallowing, struggles to reply in the affirmative.

Charles is so “cockeyed” from Jean’s perfume that when they eventually stand up, he can make only the weakest attempt to kiss her, which Jean easily repulses. To the censors, however, the combination of close shot scale, physical intimacy, and intoxication (even from perfume) was intolerable–too expressive of Charles’ rising desire. I suspect they actually conflated the lengthy take and the medium close-ups (no “looking over” occurs in the point of view sequence). In any case, censors had seldom seen such “looking over” shots since the early 1930s.

In addition, all four offended states were roused by the famous chaise longue scene. As Charles tries to apologize for scaring Jean with his snake Emma, she holds him close, runs her hands through his hair, tickles his ear, and breathes heavily in his face. Taking the key elements of the shoe-replacement business to another level, the erotic hilarity of this scene arises from the complete power of Jean’s spell over Charles and their sheer proximity, in two long takes (one lasting 36 seconds, and then a closer, three-minute and fourteen-second shot). During all this time, Jean won’t let Charles kiss her, but their faces are close together and their lips are never far apart. For some censors, the most provocative elements of the scene resided in the dialogue that begins with Charles’s fall to the ground ands run through his “accompanying indecent action” (Pennsylvania again) of pulling down Jean’s skirt.

Pennsylvania also cut Jean’s sigh of anticipatory orgasmic release after describing her first encounter with her future husband: “And the night will be heavy with perfume and I’ll hear a step behind me and somebody breathing heavily and then – Ohhhhh!”

Ohio originally wanted the entire scene deleted, starting with Jean’s command “Oh, come over here and sit down beside me” through their final exchange:

Jean: Oh, you’d better go to bed, Hopsy. I think I can sleep peacefully now.

Charles (adjusting his bow tie): Well, I wish I could say the same.

Jean: Why, Hopsy!

Industry representatives negotiated with the Ohio and Pennsylvania boards to try to reduce their demands; Pennsylvania was unmoved, but Ohio was persuaded to let all but their final exchange remain in the film. An outraged San Antonio Amusement Inspector articulated the boards’ thinking when she cut what she called the film’s two “prolonged scenes of passion” in Jean’s stateroom. These, she pointed out to Breen, violated Section 2 of the Code, about “suggestive postures and gestures” and seduction being used for comedy. So in San Antonio, as in Pennsylvania and Kansas, viewers missed the bulk of two of the most celebrated comic scenes in American film history.

With The Lady Eve, Breen’s instincts were generally astute. He had advised against Sir Alfred’s sketch of the Handsome Harry plot. He had eliminated the overt sex affair scene in Jean’s cabin. Yet he missed many elements as well. Besides those stateroom scenes cut by state and city censors, there were ostensibly innocent lines. As Charles searched for a new pair of shoes, Jean says, “See anything you like?” and leans back with a bare midriff.

The constantly repeated phrase “been up the Amazon for a year” references Charles’s extended sexual privation and naivete, which make him susceptible to Jean’s wiles. But the phrase can also be taken as evoking female anatomy itself. The neglect of these details resulted from Breen’s increasing tolerance and his equally increasing tiredness. We’re lucky he left them in.

Upping the ante

The negotiations over The Palm Beach Story and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek followed the pattern set by The Lady Eve. The writer-director proposed increasingly outlandish scenarios; Geoffrey Shurlock and Breen again demanded an increasinglyu longer list of changes across a longer series of letters. Sturges alternately made cuts or assured them he could handle the material.

Once more, certain moments wound up offending local censors. For The Palm Beach Story, released in late 1942, only New York and Kansas passed the film without eliminations. Elsewhere, many of the suggestive elements that Shurlock had criticized were cut. One was Gerry’s line—describing how Tom sees her after many years of marriage–as “just something to snuggle up to and keep you warm at night, like a blanket” (Pennsylvania). Another was the first vertebrae-kissing scene in which a very drunk Tom breaks down a very drunk Gerry’s resistance to having sex.

Other deletions concerned details that had escaped Shurlock’s notice: Pennsylvania removed the underlined portion of Gerry’s explanation to Tom, after the Wienie King’s visit and munificence, of “the look” women get from men: “From the time you’re about so big, and wondering why your girl friends’ fathers are getting so arch all of a sudden – nothing wrong – just an overture to the opera that’s coming.” Even after many changes to her dialogue, scenes with Princess Centimilia could have provoked bans or major cuts. After all, she is followed around by her gigolo Toto (Sig Arno) and (in an ironic adherence to the Code’s demands) marries purely to legitimize her sexual impulses. Yet in part because of Mary Astor’s frantic line delivery, her scenes were retained. Overall, relative to its many potential offenses, The Palm Beach Story faced surprisingly minimal objections.

The entire premise of Miracle and the ensuing action mock the notion of marriage’s sanctity from multiple angles. Breen, the American military, and the Legion of Decency examined the film minutely before it was issued a seal, and many changes were made. For this reason, only one state board (Kansas) cut one line of dialogue: Trudy’s comment that “Some sort of fun lasts longer than others.”

Still, there was much to offend audiences and censors in the completed film. For example, the MPPDA and Sturges received numerous letters of complaint linking the film to the growing problem of juvenile delinquency. One viewer in Minneapolis wrote that the film showed it to be “a subject for slapstick and high comedy, especially if the delinquent is unusually fruitful. . . . My boy thought she must have passed the night with 6 soldiers or sailors. . . . In Hollywood I understand you can get away with despoiling young girls and morals don’t exist except for yokels. Do you have to spread that poison?” Given the growing panic over what was seen as a national JD epidemic, Paramount’s delay in distributing Miracle—it was completed in Spring 1943 but released in January 1944—exacerbated the controversy.

Upon reviewing The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, James Agee famously stated that “the Hays office has been either hypnotized …or raped in its sleep.” The same might seem to be true of The Lady Eve and The Palm Beach Story, but this was manifestly not the case. There were elements that the PCA didn’t catch–suggestive postures and dialogue, scenes of seduction–because Sturges created so many and whisked them by so swiftly. But he got away with it for other reasons as well. The PCA helped steer Sturges to finding ways of modifying the most brazenly unacceptable material. The standards of acceptability were expanding, controversially, and they would continue to do so. Meanwhile, the response of local censor boards and individual audience members provides crucial evidence of how at times the PCA succeeded and at other times it failed to suppress material that might offend. Knowing this history can only deepen our appreciation of what the Sturges comedies achieved.

This entry is a revised version of a portion of an article that appears as “The edge of unacceptability: Preston Sturges and the PCA” in Refocus: The Films of Preston Sturges, editors Jeff Jaeckle and Sarah Kozloff, forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press. Primary sources include Sturges’ correspondence and the PCA files housed at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills. The Lady Eve and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek files are available on microfilm in MLA, History of Cinema: Selected Files from the Motion Picture Association of America Production Code Administration Collection (Woodbridge, CT: Primary Source Microfilm, 2006).

I’ve also drawn on these published sources: David Bordwell, “Parker Tyler: A suave and wary guest”; Brian Henderson, Five Screenplays by Preston Sturges (1986); Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Work of Preston Sturges (1994); Lea Jacobs, The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film (1997); Kathleen Rowe, The Unruly Woman: Gender and the Genres of Laughter (1995); and Elliot Rubenstein, “The End of Screwball Comedy: The Lady Eve and The Palm Beach Story,” Post Script 1, no. 3 (Spring-Summer 1982), 33-47.

THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS: A usable past

Hellzapopppin’ (1941).

DB here:

By now everybody is used to allusionism in our movies—moments that cite, more or less explicitly, other films. But we tend to forget that movies have been referencing other movies for a long while. One classic form is parody, as when Keaton’s The Three Ages (1923) makes fun of Intolerance (1916). Another example occurs in Me and My Gal (1932). Spencer Tracy tells Joan Bennett that he just saw a movie called “Strange Innertube,” and then Raoul Walsh gives us a comic version of the inner monologues used in Strange Interlude (1932).

Some allusions are in-jokes that sail by most viewers. Almost everybody notices when Walter Burns (Cary Grant) in His Girl Friday mentions that a character played by Ralph Bellamy looks like “that fella in the movies—you know, Ralph Bellamy.” Probably fewer people catch the later line, Walter’s threat to the authorities: “The last man who said that to me was Archie Leach just a week before he cut his throat.” Grant’s real name, of course, was Archibald Leach.

Week-End at the Waldorf (1945) is a sort of updating of Grand Hotel, so when one character remarks that a plot twist “is straight out of the picture Grand Hotel,” we probably catch the self-reference. But the other character piles on the allusions by replying: “That’s right. I’m the baron, you’re the ballerina, and we’re off to see the wizard.” Did people notice MGM congratulating itself twice? And you wonder how many viewers catch the spoiler in Hellzapoppin’ (1941), released only four months after Citizen Kane. Chic Johnson spots a Rosebud sled hanging outside an igloo and remarks, “I thought they burnt that.”

At the beginning of the 1940s, two novice directors seemed to be bringing fresh air to Hollywood cinema. Preston Sturges and Orson Welles were identified with innovative approaches to genre and storytelling. So we might expect them to inject something new into this practice of alluding to other movies. I think they did.

Consider a particular strategy that Sturges and Welles toyed with. Today, we enjoy it when a director treats characters in non-sequel films as sharing a fictional world. Tarantino imagines shifting his characters or brand names (e.g., Red Apple cigarettes) from movie to movie.

When I sell my movies, I retain the rights to characters so I can follow them. I can follow Pumpkin and Honey Bunny or anybody and it’s not Pulp Fiction II.

Jackie Brown (1997) features Michael Keaton as FBI agent Ray Nicolet, who also appears, played by Keaton, in Soderbergh’s Out of Sight (1998). The tactic fitted these directors’ adaptations of novels by Elmore Leonard, who tends to carry over characters from book to book.

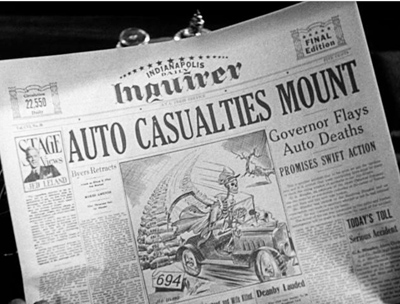

It’s a bit surprising to see this impulse in Sturges and Welles too. The governor and the political boss in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) are McGinty and the Boss in The Great McGinty (1940), and they’re played (uncredited) by the same actors. A newspaper glimpsed in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) contains a column, “Stage Views,” by drama critic Jed Leland, a major character in Citizen Kane (1941).

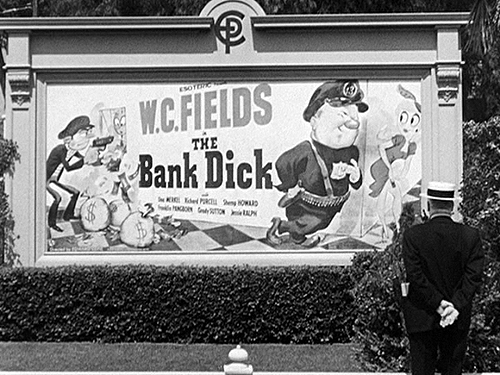

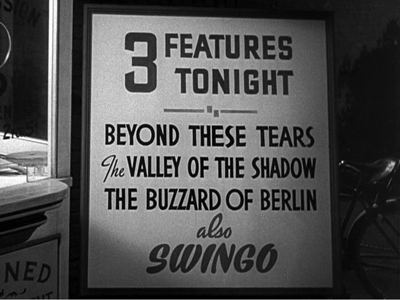

Today fans are used to spotting things that most viewers might not get, but in the early 1940s, it was rarer. I’ve proposed earlier that sometimes Hollywood’s creative community is addressing not the broad audience but its own members, perhaps letting dedicated outsiders “overhear” the conversation. One example would be the nearly-hidden jokes that can be wedged into the background or on the edges of the action. In an entry about a year ago, I considered how sequences around the small-town movie theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek carry barely-noticeable jabs at current films, mostly those by Sturges’ home studio Paramount. And Luke Holmaas has pointed out to me that Hail the Conquering Hero contains a billboard advertising Morgan’s Creek—a sort of joking product-placement. Today, I want to suggest that Welles moved onto the same terrain but followed even more circuitous paths.

The past, not recaptured

Make pictures to make us forget, not remember.

Comment card from first preview of The Magnificent Ambersons, 1942.

The Magnificent Ambersons is, everybody knows, a film about the past. Its story action begins around 1885 and concludes just before World War I. Most of the plot concentrates on the decline of the Amberson family, due partly to financial mismanagement and the willful pride of Isabel Amberson’s son, George Minafer. Parallel to that decline is the development of the town into a city and the rise of the automobile company founded by Eugene Morgan, a failed suitor for Isabel’s hand. A major turning point comes when, after Wilbur Minafer’s death, Isabel is left a widow. She’d like to marry Eugene, but she declines because George is opposed. At the same time, George tries to win Eugene’s daughter Lucy. After the death of Isabel and her father Major Amberson, the family is destitute and George must find a way to support his aunt Fanny. Struck by a car, George is hospitalized, and only then does he reconcile with Eugene and Lucy.

After weak previews, the film was drastically recut, and some new scenes were shot. The original version has not yet been found, so we’re left with a ruined masterpiece. Still, there’s enough there to let us appreciate Welles’s effort to make sense of a crucial period of American history. Old money was giving way to modern, technology-driven fortunes; Eugene’s auto company is the Dell Computers of its day. The film also evokes changes in urban life, with shifting property values and rising pollution shown as consequences of progress. It’s the most downbeat of the “nostalgia” cycle of the 1940s, which includes Strawberry Blonde (1941), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), and Centennial Summer (1946).

Many other films have sought to present the past, recreating the settings and costumes and props of an era. But Ambersons is about pastness. It conveys a melancholy recognition that things are always changing, that we struggle to make sense of events only after it’s too late to affect them. It’s a film centered on missed opportunities and what might have been. Eugene might have married Isabel when they were young, but his drunken serenade turns her against him. If George weren’t such a prig, he might have reconciled himself to Isabel’s remarriage; only at the end, kneeling in prayer, does he seem to realize how his stubbornness cheated many people of happiness. The original ending would have shown Eugene visiting Fanny in a boarding house, with her long and unspoken love for him counterpointing his suggestion that he’s been true to Isabel.

Ambersons carries its sense of an unrecoverable past into the very texture of its telling. At first, the aura of things gone by is given by Welles’ voice-over narration. In affectionate comedy he introduces us to habits and routines of an era of streetcars and changing men’s fashions. After Eugene’s botched serenade, the townsfolk add their voices to the chorus with comments on the scandal. More backstory is given when George is shown growing from a spoiled boy to an arrogant young man. Our narrator recalls “the last of the great Amberson balls.” Eugene arrives, a widower, bringing his daughter Lucy, and George begins to court her that night.

Now the narrator’s past-tense explanation withdraws for some time. Instead, characters take up the burden of narrating the past. “Eighteen years have passed,” says Isabel’s brother Jack at the ball. “Or have they?” Before Eugene dances with Isabel, he remarks that the past is dead. Unfortunately, it won’t stay buried. The old romance between Isabel and Eugene will be rekindled, and bad business decisions and George’s spendthrift ways catch up with the family.

Welles’s plot construction relies on ellipsis. The scenes skip over major story events—Wilbur’s death, the decline of the family fortune, Gene’s second courtship of Isabel, and Isabel’s death. So much occurs offscreen that we are left to play catch-up. We must listen to characters report on what has just happened, or reflect on the more distant past. The film is built on recollection and reaction. We don’t see Fanny at Isabel’s deathbed; she simply flies out of the room to embrace her nephew: “She loved you, George.” We don’t see George and Isabel on their European trip; we learn of it from the doleful Uncle Jack, who thinks that Isabel is falling sick. This refracted narration allows Jack to voice his concern—he’s probably the one Amberson whose judgments we trust—and Gene to display helpless, rigid sorrow at the news.

One of Ambersons’ most famous scenes, the long take of George and Fanny in the kitchen, is characteristic. Under her questioning, he explains that Gene and Isabel were starting to reunite at his college graduation. A peppy nostalgia movie would have shown us that cheerful moment on the campus, but Welles channels the information through George’s insensitive report and Fanny’s uneasy questions—and the scene climaxes with her breaking down in tears. As ever, melancholy wins out. As a result of George’s telling, Fanny will plant the suspicion that gossip about Isabel has been destroying the family’s good name.

Similarly, another film’s finale would show the reconciliation of the young lovers, George and Lucy, in the hospital. Instead Welles’ original script presents that moment through Eugene’s somber report of it to Fanny in her boarding house. (In the version we have, we get the report in the hospital corridor.)

Sometimes, the gaps in time and action are abetted by the studio’s reediting. In the present version, we learn about Aunt Fanny’s failed investments later than in the original version. But even then the information would have been presented after the fact. On the whole, the sense of the sadly unalterable past is built into Welles’ screenplay. As each scene unfolds, we get news about what has happened in the gap since the last scene, or what has happened years before. At the railroad station, Uncle Jack, about to depart, recalls a woman he left here long ago. “Don’t know where she lives now–or if she is living.” Here the pastness he evokes is familiar to us from earlier in the film: “She probably imagines I’m still dancing in the ballroom of the Amberson mansion.” At the limit, Major Amberson’s garbled fireside reverie takes us back to the origins of life: “The earth came out of the sun, and we came out of the earth . . . so–whatever we are must have been in the earth.” Now the past is primeval.

Retro as remembrance

Welles enhances the aura of pastness through specific film techniques. Critics have rightly been alert to creative choices that carry over from Citizen Kane: looming sets, drastic deep-focus cinematography, low angles, chiaroscuro, and long takes, often employing splendid camera movements. But the film displays some unique choices that are, historically, anachronistic.

The most noticeable old-time technique concludes the idyll in the snow. Jack, Fanny, Lucy, and George are riding in Eugene’s horseless carriage. This, one of the few scenes that doesn’t replay the past in its conversation, is given special treatment as a moment out of time. The iris out that concludes the scene is something of a visual equivalent to the old song the riders sing, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.”

Similar is the vignetting that softens the edges of the opening sequences, starting with the first shot showing the streetcar stopping for the lady of the house.

Welles’ visual techniques aren’t faithful to the period when the story action takes place. Assuming that the snow idyll occurs around 1904, the iris wouldn’t have appeared in films of that time. And the earlier period of the streetcar shot and changing men’s fashions probably predates the invention of cinema. But by 1942, these techniques were associated with silent film generally and give a cinematic tinge of “oldness” to the action.

I say “by 1942” because recent years had made intellectuals especially conscious of film history. Several books, notably the 1938 translation of Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach’s Histoire du cinéma (translated as The History of the Motion Picture) and Lewis Jacobs’ sweeping The Rise of the American Film (1939) had concentrated on the stylistic innovations of Porter, Griffith, and other pioneers. With some theatres reviving silent classics like Caligari and The Birth of a Nation, cinephiles in urban centers had some opportunities to see silent movies. Most notably, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library was founded in 1935 and under the curatorship of Iris Barry, began building a permanent archive and screening retrospectives.

MoMA also assembled many films into traveling 16mm programs that could be rented by schools, museums, libraries, and other institutions. Silent films also circulated in 8mm and 16mm prints from private companies like Kodascope and Castle Films. Throughout the late 1930s and 1940s, silent comedies were the most popular; Chaplin reissued The Gold Rush in a sound version in 1942. Welles’s interest in silent slapstick is shown in the recently discovered pastiche, Too Much Johnson (1938), which evidently owes a good deal to Entr’acte (1924), a MoMA-canonized classic.

Ambersons offers other, less obvious allusions to old cinema. One cluster of them comes during George and Lucy’s stroll along the sidewalk. George, somewhat petulantly, is insisting that his trip abroad with his mother may last a long time. “It’s goodbye, Lucy.” Angling for a declaration of devotion from her, he gets brittle, agreeable indifference. When he has stalked off, we learn that she is actually quite shaken by the prospect of separation. Watching the dramatic interplay in this long traveling shot, we are probably not likely to pay attention to the posters the couple pass outside the Bijou theatre.

The advertisements announce movies that could have played the Bijou in 1912. The ones in the rear of the lobby are impossible to make out, and there’s one outside I can’t be sure of. (See the codicil.) Raking the frames on DVD and on a good 35mm print, I’ve been able to discern The Bugler of Battery B (1912), Her Husband’s Wife (aka, How She Became Her Husband’s Wife, 1912), Ten Days with a Fleet of U.S. Battleships (1912; in the foyer), and The Mis-Sent Letter (1912). There were several Jesse James films circulating in 1911-1912, but one two-reeler named for the bandit (at the bottom of the second frame here) seems a likely candidate.

These casual background details betray extraordinary fussiness on the part of Welles and his colleagues. Few viewers would pay attention to all the posters, and very few viewers would realize that they’re all from the same year. It’s one thing to include authentic automobiles from the era, as car fanciers would be sure to spot mistakes. But 1912 two-reelers? It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the filmmakers put the posters in to satisfy themselves. (If you’re skeptical, I’d ask: If you’d thought of it, wouldn’t you do it?)

There’s more. The most prominent hoarding advertises a Western, The Ghost at Circle X Camp (1912), from Gaston Méliès. Surely the name also evokes Gaston’s brother Georges, by then an established pioneer of film history and a figure doubtless known to Welles. Is this a sideswiping tribute from one magician-cineaste to another?

There’s also a deliberate anachronism. Tim Holt, who plays George, was the son of action star Jack Holt. A lobby card over the box office announces “Jack Holt in Explosion.”

I can find no trace that such a film existed. Moreover, films of that era seldom identified the main actors in advertising, and in any case Holt was not a featured player in 1912. In order to create an in-joke/homage, Welles seems to have prepared a poster for a fictitious film—as Sturges did with Chaos over Taos and Maggie of the Marines in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek.

Perhaps the most sneaky allusion comes at the very end. After the florid voice-over credits for technical contributions, Welles intones: “Here’s the cast.” Medium-shots of the actors dissolve into one another as the voice-over identifies them. The images recall photographic portraits from the nineteenth century. They also seem to be a variant of those 1930s opening credits that catch the players in shots extracted from the movie to come. Still, there’s something peculiar about these.

Some of the actors look straightforwardly out at us, as we’d expect.

But others turn their heads slightly or shift their gaze, toward or away from us.

Sometimes the shift is tiny, as with the Joseph Cotten cameo. But the tactic is made into a joke when Tim Holt, staying in character, snaps his glance furtively to the camera.

Why these fillips? Here’s my conjecture. Some 1910s films, from both America and Europe, introduced their casts with shots of the actors standing as if on a theatre stage. The actors then looked to left, then right, pretending to take in all sides of a live audience. Here’s an example from Reginald Barker’s The Wrath of the Gods (1914), featuring actor Thomas Kurihara.

None of the 1910s examples I know was framed as closely as Welles’s shots are. But I surmise that Welles offered a modernized variant of a minor silent-film convention. If this is right, it has to be an allusion more far-fetched than even the ones Sturges supplied.

Maybe I’ve gone too far. Once filmmakers start playing these games, overreach is a constant temptation. In any case, I think there’s enough evidence that Welles, like Sturges, was invoking early film history as a way of reinforcing the overall pastness-strategy of his film.

I’d go further and speculate that Welles’s obsessively pinpointed allusions may have stirred a competitive spirit in Sturges. Now we can see the Miracle of Morgan’s Creek tracking shot past the movie house posters as a variant, two years later, of the angle Welles chose for his long take.

And perhaps the audacious inclusion of footage from The Freshman (1925) at the start of The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947) was sparked by Welles’ virtuosically faked newsreel in Citizen Kane. As the two boy wonders from the East took advantage of the biggest train set a kid could play with, they may have egged each other on.

For more on the practice of allusionism and world-building see The Way Hollywood Tells It. Thanks to Ben Brewster for information on Jack Holt’s career. My quotation of the Ambersons preview card comes from Simon Callow’s Orson Welles vol. 2: Hello Americans (Viking, 2006), 87.

The Holt and Méliès posters are mentioned in the cutting continuity in Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction (University of California Press, 1993), 214. Alas, the other posters aren’t specified.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster’s illustration, which we can glimpse more fully in a later phase of the shot, shows a man thrashing an American Indian while a woman stretches out her arms in the cabin in the background. At first I thought the first words are The Car, but I can find no film from the period that begins with that phrase. (It would fit more closely with Ambersons thematically than most of the other titles, but in fact “car” wasn’t then a common term for automobile.) Then I thought it was The Coin Box Girl, but again no such film seems to have existed, and that title is hardly in keeping with the illustration. Any ideas?

Yes, I know. Welles would have had a good big belly laugh at these efforts.

P.S. 10 June: I’ve been pursuing some readers’ leads about the still-mysterious poster. In the meantime, Joseph McBride has has corresponded with me with more ideas and information about Ambersons. Joe is the author of many books, including What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: A Portrait of an Independent Career, Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless, and Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit, a meticulous study of those two murders. He is one of the world’s top Welles scholars, so naturally I’m happy to pass along his thoughts.

AMBERSONS is my favorite film, as you probably know, even in its partly ruined state. I think all your analysis is acute, and I like your focus on the self-conscious awareness of pastness that Welles conveys and dissects in the film. The film is redolent of Welles’s youth and even more so of the period before he was born (the period for which I find most of us are most nostalgic). Nostalgia was considered a neurosis in the pre-modern era, a sign of inability to adjust to reality rather than the warm-and-fuzzy state it’s thought of being today. There’s a deep melancholy throughout the film, even if Welles, good magician that he is, distracts us with misdirection via comedy in the beginning while simultaneously laying the seeds of destruction and foreshadowing George’s “comeuppance,” etc.

Last month I was at the Welles conference in Woodstock, Illinois, which has preserved much of its nineteenth-century flavor, including the Opera House where Welles put on TRILBY (but most of the Todd School for Boys he attended is gone). That town and its main square, with bandstand and Civil War monument, seems very Ambersonian as well. I have always seen AMBERSONS as Welles’s most deeply personal film, and his claim that Eugene Morgan is partly based on his father (and that Booth Tarkington knew his father) is noteworthy, as is George Amberson Minafer’s evil-twin resemblance to the young George Orson Welles.

I would only add to your insights that there was much more about the loss of the Amberson fortune in the full version of the film (you allude to that a bit), even though, as you intriguingly note, Welles employs an elliptical style throughout. Welles’s use of ellipsis is Lubitschean (he considered Lubitsch a “giant”), although used for somewhat different reasons, Welles doing so mostly to condense the story in witty ways (and, as you observed to me, focus on characters’ emotional reactions to offscreen events, in the manner of Henry James) and Lubitsch to evade censorship while providing subtle rather than blunt treatments of sex. And some of Lubitsch’s German films, as you know, start with specially posed head shots of him and his main actors, somewhat similar to what Welles does at the end (though he teasingly keeps himself out of frame, partly to stress the voice aspect and also to keep the identification of himself with George stronger). Tim Holt gazing accusingly at us in the end credits is startling — maybe it’s not only to keep him in character but also to say, “I’m you.”

Welles is terrible (archy, corny, and putting on a phony kid voice) as George in the radio version, which, however, is much like the film in some ways. During the night devoted to radio in the 1978-79 “Working with Welles” seminar I co-hosted for the AFI at the DGA Theater, Welles’s longtime associate Richard Wilson and I ran the first ten minutes of the radio show as the soundtrack for the film imagery, and it worked amazingly well. Welles’s use of ellipsis in the film recalls his radio work, in which he and his writers would condense a large novel into one hour, etc. The vignettes at the opening of AMBERSONS are very much drawn from radio. He sold the project to RKO’s George Schaefer by playing the radio show, though the fact that Schaefer fell asleep before the end might have given them pause.

Welles said he included the “Jack Holt in EXPLOSION” gag did to please Jack when he visited the set. Jack was an action star for Capra before AMBERSONS and turns up in THEY WERE EXPENDABLE, in the scene in which John Ford pays homage to his high school teacher Lucien P. Libby by naming a boat after him. Another of those in-jokes that permeate even classic Hollywood, as you say. Mr. Libby influenced Ford’s portraits of Lincoln and other folksy politicians as humorous storytellers.

Welles’s early films show a keen awareness of film history and culture, more than he would let on later he knew at that young age. He described THE HEARTS OF AGE to me as a spoof of THE BLOOD OF A POET and LA CHIEN ANDALOU. TOO MUCH JOHNSON is full of film influences and allusions (I think I sent you my essay on the film from Bright Lights. And KANE has its share of in-jokes, such as Gregg Toland interviewing Kane on board a ship and Kane responding with his first words in the film after “Rosebud” — “Don’t believe everything you hear on the radio.”

Thanks to Joe for corresponding.

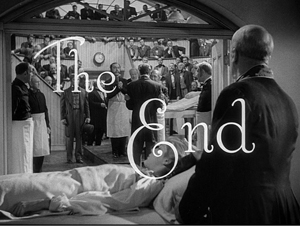

Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941).

Innovation by accident

DB here:

The old drama is being reenacted before our eyes, and as often happens, Harvey Weinstein plays the villain. The American release version of Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, which has cut and changed the original, is being decried as a travesty, the dilution of an artist’s original conception in the name of what somebody thinks will sell.

I take up The Grandmaster in another entry. For now, I just want to point out the archetype goes back long before Harvey came on the scene. A screenwriter or director comes up with a fresh approach to telling the story. But a producer rules it out as something the audience won’t buy, or even understand. Moral: In Hollywood, the creative force is stifled by a money person who insists on doing things as usual.

The 1940s in Hollywood was an era of narrative innovation. It gave us weird dream sequences and insane protagonists and subjective point of view and byzantine flashbacks and talking houses and complicated replays of action we thought we understood. While working on a book on this era, I’ve begun to wonder what the limits of innovation might be. What could make the boss tell the filmmaker that a particular narrative choice just went too far?

Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a bumpy production

A Letter to Three Wives (1949).

One example I found was purely anecdotal, but nifty nonetheless. In preparing the screenplay for Out of the Past (1947; aka Build My Gallows High), screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring wanted to have the story told by a deaf-mute boy. Apart from the fact that the boy plays a minor role in the opening of the film as it was finished, the idea of someone who cannot hear or speak serving as narrator proved to be something of a stretch for the time. Mainwaring reports that the idea was rejected.

That’s the kind of thing I wanted to find. Yet my searches sometimes came up with cases where the producer’s notes actually resulted in improvements. Take A Letter to Three Wives (1949), justly praised as one of the best films of the 1940s.

John Klempner’s original novella (published in 1945) and novel (1946), both titled A Letter to Five Wives, obviously involved two more couples. After some other writers had drafted versions, Vera Caspary was assigned to prepare a treatment. Probably with the input of producer Sol Siegel, she eliminated one couple. Her adaptation already contains much of what is distinctive about the movie as we have it. Instead of the many distributed flashbacks in the originals, the treatment consolidated them into three lengthy ones. At Siegel’s suggestion, Caspary brought the three women together on the boat. To Fox studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck we apparently owe the idea that one woman, Deborah, would be the primary vehicle of our sympathy and would initiate and resolve the mystery of whose husband has defected. Above all, Caspary’s treatment includes the unforgettable voice-over of the never-seen Addie Ross.

When director Joseph L. Mankiewicz saw Caspary’s final adaptation, in effect “A Letter to Four Wives,” he declared he “looked upon the Promised Land” and quickly turned it into a screenplay. After reading Mankiewicz’s screenplay, Zanuck intervened again , demanding that another wife be lopped off. Mankieiwicz called this “an almost bloodless operation.”

It’s probably irrelevant that A Letter to Three Wives won that year’s Academy Awards for best screenplay and best direction. Even if it hadn’t been honored, after reading the original tales and Caspary’s adaptation, I have to conclude that the film is the best version of the lot. I suppose it partly goes to show the old rule that bad or so-so books can make very good movies. (Exibit A: The Birth of a Nation; Exhibit B: The Magnificent Ambersons; Exhibit C: The Godfather. Defense rests.) But clearly, the cuts and changes demanded by Siegel and Zanuck improved the property. The “creatives”–Klempner, Caspary, Mankiewicz–were by force majeure steered toward good results.

You can argue, though, that no written version of the film tried to be innovative, except perhaps for the device of Addie’s spectral presence. And Mankiewicz declared himself happy to make the adjustments. What about cases in which genuinely bold ideas were curtailed by the powers above? So I looked into two titles that, when released in the producers’ cuts, were denounced by their writer-directors.

Two years after Preston Sturges finished and cut his film about the discovery of ether anesthesia, Paramount producer B. G. “Buddy” DeSylva supervised and released a reedited version called The Great Moment (1944). Sturges noted of the film:

It is coming out in its present form over my dead body. The decision to cut this picture for comedy and leave out the bitter side was the beginning of my rupture with Paramount. . . The dignity, the mood, the important parts of the picture are in the ash can.

A second example is a more famous release, Twentieth Century-Fox’s All About Eve (1950). After the success of A Letter to Three Wives, Zanuck allowed Joseph L. Mankiewicz to film his three-hour screenplay as a “shooting draft.” When Zanuck saw the result, he insisted on cutting it to 138 minutes.

Throughout his life Mankiewicz was an angry man. His interviews and writings excoriate mothers, film festivals, doctors and nurses, Michelangelo Antonioni, television, the American male, theatre operators, Graham Greene, the AFI, PBS, Richard Nixon, Dennis Hopper, The Untouchables (film version), British craft unions, and other malefactors. High on the list was Darryl F. Zanuck. Long before the Cleopatra debacle, Mankiewicz was already carrying a grudge because Zanuck removed a replayed scene from All About Eve. He definitely didn’t consider that a bloodless operation.

Zanuck had final cut and he got bored with the same scene shot from different points of view.

Here, I thought, were sterling examples of creators bumping up against what was impermissible. Yet the more I looked, the more I found that the situation couldn’t be reduced to the daring director versus the philistine producer. I was forced to consider the possibility that the producers’ changes yielded not timid conformity but instead some unpredictable results–things that were themselves novel, in intriguing ways. The suits hadn’t intended to do something bold, yet in revising and patching up the films shot by two venturesome directors, they actually found themselves pulled in new directions.

Call it inadvertent innovation. Not surprisingly (this is the 1940s), it involved flashbacks.

Which great moment?

Kitty Foyle (1940).

By the early 1940s, movie flashbacks adhered to several conventions that we still recognize. Typically, we’re given a situation, the narrative Now, in which a character is recounting or simply remembering past events. We then move to those events, a shift often signaled by a track-in, a musical cue, a dissolve or other optical effect, and/or sounds from the next sequence mingling with the spoken transition. We may hear the voice-over remarks of the lead-in character at times during the action we see. Once the flashback action is complete, we return to the present, with the character who launched the flashback finishing the testimony or closing off the memory. And if the film includes several flashbacks, they are typically presented chronologically, so that the earliest events from the past are shown before later ones.

Kitty Foyle (1940) offers a clear example. In the present, Kitty recalls her romances. As they develop, we return to the present at key moments to gauge her reactions. For the sake of clarity, the romances themselves are shown to us in 1-2-3 order, tracing the events that lead up to the crisis that launched her memory journey.

Not all flashbacks respect chronology, though. Citizen Kane’s first flashback traces Kane’s career as the banker Thatcher knew it. His recollections show us Kane as a child, a young man, and then a much older man forced to sell his newspaper empire. The next flashback, as recounted by Kane’s business manager Bernstein, takes us back to show Kane as a young man assuming control of his first newspaper. Several years before Kane, Sturges had composed a script based on similarly shuffled chronology. The Power and the Glory (1933), directed by William K. Howard, presents an old man recalling episodes in the life of tycoon Thomas Garner, and those are presented out of 1-2-3 order. (I analyze that film here.)

Sturges was confronted by the problem of order in preparing Triumph over Pain. This project would tell the story of Dr. W. T. G. Morton, the popularizer of surgical anesthetic. Biographical films about scientists and inventors had become a successful cycle in the late 1930s, but Sturges wanted to stay fairly close to the facts. The problem was that Morton’s story couldn’t lead easily to a triumphant finale. Sturges noted dryly:

Dr. Morton’s life, as lived, was a very bad piece of dramatic construction. He had a few months of excitement ending in triumph and twenty years of disillusionment, boredom, and increasing bitterness. . . . To have a play you must have a climax and it is better not to have the climax right at the beginning.

Accordingly, Sturges had somehow to rearrange portions of Morton’s life.

Since [the writer] cannot change the chronology of events, he can only change the order of their presentation.

The title Sturges gave to his final version, Great without Glory, indicates its tone. A quasi-documentary prologue hails the modern benefits of anesthesia. We move to the late 1800s, when Morton’s friend Eben Frost finds a medal given to Morton now sitting in a pawnshop. He brings the medal to Morton’s widow Elizabeth, and as they sit in her parlor, the film’s first long flashback starts. It presents the public celebration of Morton’s triumph, as he and Eben are driven through the crowded streets.

The ensuing scenes trace the aftermath of his discovery—the fact that he could not patent it, his efforts to build a business on sale of ether bottles, a bout of illness, and then his receiving the medal while he is plowing on his farm.

Sturges’ version returns to the narrating frame, as Eben examines some more personal memoirs that Elizabeth has written. The second flashback initiates the play with chronology. It traces events leading up to the action we saw completed at the start of the first one. The plot takes us back to the couple’s courtship, the first years of Morton’s dentistry practice, and his arduous experiments with ether. He finds prosperity using it on his patients. Challenged to demonstrate his invention in a public surgical operation, he realizes that his demonstration will show his rivals his trade secret. He is about to leave the operating theatre when he sees the patient: a girl about to have her leg amputated. Unable to let her face agony, he turns back to reveal his discovery to his peers.

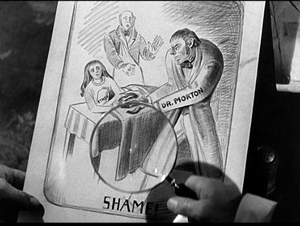

The plot’s true climax is Morton’s gesture of sacrifice. Sturges encourages us to see it as a contrast to the way the press and his profession vilified him. During the first flashback, a newspaper cartoon shows Morton preying on innocent patients, as typified by a girl on a gurney.

Sturges expected us, I think, to recall this image when Morton decides to help the girl. In his life, the cartoon came later, but showing it early in the film lets Morton’s gesture serve as a rebuke to those who are going to hound him.

After revealing Morton’s sacrifice, Great without Glory provides a bitter epilogue. The film ends with a return to the framing situation in Elizabeth’s parlor. Eben rises sadly, leaving Elizabeth alone.

Sturges could simply have built his film around Morton’s early life and his successful discovery, ending before the decades of poverty that followed. Instead, by focusing his biopic around our failure to appreciate and reward selfless research, he wanted to praise a man who achieved greatness but not the long-lived veneration accorded Edison or Pasteur. Yet showing Morton’s fall from grace after the crowd’s acclaim meant that the high point of a science biopic would be accomplished far too early in the plot. What we today call the “darkest moment”—Morton’s rejection by his public and his poverty—would come too soon. When Sturges showed his cut to his friend John Seitz, a great cinematographer, Seitz asked: “Why did you end the picture in the second act?”

According to Sturges, Buddy DeSylva said the same thing. He was already hostile to Sturges, and after some mixed preview results he set about reshaping the picture. The result is a good example, I think, of unintended innovation.

DeSylva did, as Sturges indicated, “leave out the bitter side” in certain respects. He lopped off the final scene showing the mourning of Eben and Elizabeth. The Great Moment doesn’t return to the narrating frame set up from the start of the picture. This is a little disconcerting structurally, but it wasn’t unknown at the period. Guest in the House (1944), Dillinger (1945), and other films “forget” the fact that they began with a character recalling the past.

Nor did DeSylva start the plot with Sturges’ prologue and narrating frame. He offered something immediately upbeat: Morton and Eben descending to the cheering crowd and riding through the streets to acclaim. This action, surprisingly, takes place during the credit sequence.

By inserting the moment of Morton’s triumph at the very start of the movie, before we have even seen a flashback to it, or indeed even know who these people are, DeSylva seems to illustrate the film’s title. Our first impression is that Morton’s great moment is the public recognition of what the crowds’ placards announce is his conquest of pain.

Only after this “flashforward” does the release version settle down to something roughly like Sturges’ structure. Eben discovers the medal, brings it to Elizabeth, and elicits her recollections. Some of the scenes are rearranged from Sturges’ version; the placement of one, showing Morton sick in bed, seems calculated to lead in to his death (as it doesn’t in the Sturges cut). The newspaper cartoon is there, ready to form a parallel with the climax. As in the Sturges version, a return to the narrating frame shows Eben and Elizabeth in the present launching the second big flashback. With other alterations, we go through the couple’s romance and marriage, culminating in the discovery of ether and the prosperity of Morton’s practice.

DeSylva retains Sturges’ climax: the scene when Morton must choose whether or not to reveal his trade secret to his competitors in the public demonstration. Seeing the girl praying on the gurney, he decides to do it. The film ends with him striding into the operating theatre, about to share his discovery. It is here that DeSylva halts the film, without, as we’ve seen, returning to the frame featuring Eben and Elizabeth.

Both locally and more broadly, the effect is curious. Now Morton’s great moment is revealed, as Sturges wished, as the moment of his self-sacrifice, not the moment of his celebrity. But more strangely, without the final frame situation, the film ends just before the opening credits sequence. We could easily imagine the credits as an epilogue, with Morton’s entry to his colleagues dissolving to the parade in his honor before the final fade-out. Instead, the film halts and wraps back around itself like a Möbius strip: the last thing we see immediately precedes the first thing we saw.

I’m not trying to make this movie Memento or Primer, but there is something uncanny about the release cut’s looped structure. Sturges created a story that was depressing but tidy (prologue, carefully framed flashbacks, epilogue). DeSylva, unable to rewrite Morton’s history and apparently reluctant to junk the project, made the story more upbeat but also more untidy. Trapped by Sturges’ design, he re-carved it in a uniquely peculiar shape.

Sturges’ bold stroke was to switch the two chronological blocks of Morton’s life and to make us sense the injustice of Morton’s fleeting fame. DeSylva wanted to avoid the grim epilogue in the present and end on an upbeat note. But he did retain the split chronology, so that the contrast between obscurity and fame remains. He inadvertently innovated by making the opening credits preview a scene far ahead in the plot, and then letting the ending twist back to it. By playing the title over the parade, the release version shifts us across two moments, and meanings, of greatness: celebrity and self-sacrifice.

Did Buddy set out to be daring? I don’t think so. He faced constrained solutions whichever way he turned, just like us most of the time. More on this matter at the end.

As easy as C-A-C-B-C-B-C

As I mentioned, flashbacks usually sit comfortably in a frame, a well-established present situation that we depart from and return to. The shifts in and out of the past can be eased by various devices, one of which is a voice-over representing the character. The voice-over may be objective, as when a trial witness is testifying, or subjective, representing the “inner voice” of the person remembering what we have in the flashback.

Again, however, a film built out of flashbacks has many options. Coming to direction in the mid-1940s, Joseph L. Mankiewicz was in a position to try his own riffs on current experiments in storytelling.

So, for instance, in House of Strangers (1949), he frames a flashback without a voice-over. The camera coasts up a stairway to a window at night; dissolve to the window in daytime, and pull away to reveal the earlier scene. Our understanding of the time shift is aided by the comparison on the musical track: a phonograph record of a passage from the opera Martha fades out, and in the flashback, the Monetti family patriarch, now alive, is singing it.

Similarly, A Letter to Three Wives (1949) supplies the symmetrical structure in shifting from Deborah to her anxious memories and then back again.

But the voice-over varies from the usual. Instead of hearing her voice asking herself, “Is it Brad?” we hear the voice of Addie Joss, who also narrates the film. The suburban wives’ obsession with their rival, who may have run off with one husband, has allowed her to burrow into each woman’s consciousness. (In addition, her voice merges with the chugging of the ship to create distortions courtesy of Sonovox.)

House of Strangers is built around one long flashback; A Letter to Three Wives gives us three parallel ones. All About Eve yields yet another variant. Three characters at a banquet recall their experiences with Eve, the dazzling young actress to be given an award. There will be several flashbacks following Eve’s career chronologically and skipping from one remembering character to another. Given this plan, Mankiewicz’s long version planned for one moderate experiment and one fairly daring one.

The moderate experiment was to eventually eliminate the visual anchoring of the frames. He had planned to start with very clear bookends around the flashbacks and then gradually discard framing scenes. For instance, after Addison DeWitt’s voice-over introduces the other characters, including Margo and Karen sitting at his table, Karen’s voice-over intervenes. We leave the banquet to flash back to her meeting Eve.

In Mankiewicz’s “shooting draft” of the film, we then return to the banquet in the standard bookend fashion. Karen looks over at Margo much as Addison had looked at her. We hear Margo’s voice-over, and then her flashback is launched. Mankiewicz planned, in all, three of these base-touching intervals in the banquet. The later flashbacks are simply signaled by voice-overs only, interweaving the memories of Karen, Margo, and Addison as Eve rises in the theatre world. In short, Mankiewicz wanted to replace block flashbacks with “polyphonic” ones, but only after careful preparation.

The more daring experiment, and the one whose loss rankled for years, was the idea of replaying Eve’s famous “applause” monologue. We’re at Margo’s party, and several characters are perched informally on the staircase. Addison and Bill, Eve’s fiancé, have argued about the nature of the theatre. Then Eve launches on a brief but impassioned ode to the joys of acting. Applause amounts to “waves of love coming across the footlights and wrapping you up.” Mankiewicz wanted this to follow a scene between Karen and Eve in Margo’s bedroom. Introduced by Karen’s voice-over, this scene shows Eve pressing Karen to help her become Margo’s understudy. Following this, Eve’s monologue can be seen as a warm testimony to her dedication to the theatre—a confession that Karen watches dotingly from a higher step.

At this point, Margo enters from the kitchen and confronts Eve before insulting the other guests and flouncing off to bed.

Instead of showing this scene’s aftermath, Mankiewicz wanted to break chronology and skip back to the beginning of the party, with Margo’s voice-over now introducing things. After some scenes showing her efforts to get Eve out of her life, she was to stalk out of the kitchen and hear in the hallway the end of Eve’s monologue.

They [Margo and Lloyd] exit into the dining room. As they open the swinging door, the CAMERA REMAINS in the doorway. Margo and Lloyd walk toward the stairs. In the b.g., Eve is talking to the group.

How much she says is dependent on how long it takes Margo and Lloyd to reach her.

EVE (in the b.g.): Imagine,,, to know, every night, that different hundreds of people love you… They smile, their eyes shine—you’ve pleased them, they want you, you belong. Anything’s worth that.

Just as before, she becomes aware of Margo’s approach with Lloyd. She scrambles to her feet….

MARGO: Don’t get up. And please stop acting as if I were the queen mother.

And as Margo speaks—or before—we FADE OUT.

By following Margo’s efforts to cast Eve out, the effect of hearing part of the monologue is to confirm Margo’s suspicions that Eve’s demure obedience conceals her desire to compete on the stage.

What Mankiewicz wanted, it seems, was to use a replay for a new purpose. In Mildred Pierce and other 1940s films, the replaying of an action fills in missing material, usually with the purpose of dispelling a mystery or providing a surprise. Here the replay contrasts two characters’ reactions: Karen finds Eve’s speech touching, Margo finds it threatening. Most replays enhanced plot, whereas this emphasized characterization (which in turn advanced the plot).