Archive for the 'Directors: Scorsese' Category

Learning to watch a film, while watching a film

The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992).

DB here:

“Every film trains its spectator,” I wrote a long time ago. In other words: A movie teaches us how to watch it.

But how can we give that idea some heft? How do movies do it? And what are we doing?

Many menus

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (2011).

In my research, I’ve found the idea of norms a useful guide to understanding how filmmakers work and how we follow stories on the screen. A norm isn’t a law or even a rule; it’s, as they say in Pirates of the Caribbean, more of a guideline. But it’s a pretty strong guideline. Norms exert pressure on filmmakers, and they steer viewers in specific directions.

Genre conventions offer a good example. The norms of the espionage film include certain sorts of characters (secret agents, helpers, traitors, moles, master minds, innocent bystanders) and situations (tailing targets, pursuits, betrayal, codebreaking, and the like). The genre also has some characteristic storytelling methods, like titles specifying time and place, or POV shots through binoculars and gunsights.

But there are other sorts of norms than genre-driven ones. There are broader narrative norms, like Hollywood’s “three-act” (actually four-part) plot structure, or the ticking-clock climax (as common in romcoms and family dramas as in action films). There are also stylistic norms, such as the shoulder-level camera height and classic continuity editing, the strategy of carving a scene into shots that match eyelines, movements, and other visual information.

Thinking along these lines leads you to some realizations. First, any film will instantiate many types of norms (genre, narrative, stylistic, et al.). Second, norms are likely to vary across history and filmmaking cultures. The norms of Hollywood are not the same as the norms of American Structural Film. There are interesting questions to be asked about how widespread certain norms are, and how they vary in different contexts.

Third, some norms are quite rigid, as in sonnet form or in the commercial breaks mandated by network TV series. Other norms are flexible and roomy (as guidelines tend to be). There are plenty of mismatched over-the-shoulder cuts in most movies we see, and nobody but me seems bothered.

More broadly, norms exist as options within a range of more or less acceptable alternatives. Norms form something of a menu. In the spy film, the woman who helps the hero might be trustworthy, or not. The apparent master mind could turn out to be taking orders from somebody higher up, perhaps somebody supposedly on your side. One scene might avoid continuity editing and instead be presented in a single long take.

Norms provide alternatives, but they weight them. Certain options are more likely to be chosen than others; they are defaults. (Facing a menu: “The chicken soup is always safe.”) An action film might present a fight or a chase in a single take (Widows, Atomic Blonde), but it would be unusual if every scene in the film were played out this way. Not forbidden, but rare. Avoiding the default option makes the alternative stand out as a vivid, willed choice.

Very often, critics take most of the norms involved for granted and focus on the unusual choices that the filmmakers have made. One of our most popular entries, the entry on Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, discusses how the film creates a demanding espionage movie by its manipulations of story order, characterization, character parallels, and viewpoint. It isn’t a radically “abnormal” film, but it treats the genre norms in fresh ways that challenge the viewer.

Because, after all, viewers have some sense of norms too. Norms are part of the tacit contract that binds the audience to creators. And the viewer, like the critic, looks out for new wrinkles and revisions or rejections of the norm–in other words, originality.

Picking from the menu

Norms of genre, narrative, and style are shared among many films in a tradition or at a certain moment. We can think of them as “extrinsic norms,” the more or less bounded menu of options available to any filmmaker. By knowing the relevant extrinsic norms, we’re able to begin letting the movie teach us how to watch it.

The process starts early. Publicity, critical commentary, streaming recommendations, and other institutional factors point up genre norms, and sometimes frame the film in additional ways–as an entry in a current social controversy (In the Heights, The Underground Railroad), or as the work of an auteur. You probably already have some expectations about Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch.

Then, as we get into the film, norms quickly click into place. The film signals its commitment to genre conventions, plot patterning, and style. At this point, the film’s “teaching” consists largely of just activating what we already know. To learn anything, you have to know a lot already. If the movie begins with a character recalling the past, we immediately understand that the relevant extrinsic norm isn’t at that point a 1-2-3 progression of story events, but rather the more uncommon norm of flashback construction, which rearranges chronology for purposes of mystery or suspense. Within that flashback, though, it’s likely that the 1-2-3 default will operate.

As the film goes on, it continues to signal its commitment to extrinsic norms. An action scene might be accompanied by a thunderous musical score, or it might not; either way, we can roll with the result. The characters might let us into their thinking, through voice-over or dream sequences, or we might, as in Tinker, Tailor, be confronted with an unusually opaque protagonist whose motives are cloudy. The extrinsic norms get, so to speak, narrowed and specified by the moment-by-moment working out of the film. Items from the menu are picked for this particular meal.

That process creates what we can call “intrinsic norms,” the emerging guidelines for the film’s design. In most cases, the film’s intrinsic norms will be replications or mild revisions of extrinsic ones. For all its distinctiveness, in most respects Tinker, Tailor adheres to the conventions of the spy story. And as we get accustomed to the film’s norms, we focus more on the unfolding action. We’ve become expert film watchers. We learn quickly, and our “overlearned” skills of comprehension allow us to ignore the norms and, as we stay, get into the story.

Narration, the patterned flow of story information, is crucial to this quick pickup. Even if the film’s world is new to us, the narration helps us to adjust through its own intrinsic norms. The primary default would seem to be “moving spotlight” narration. Here a “limited omniscience” attaches us to one character, then another, within a scene or from scene to scene. We come to expect some (not total) access to what every character is up to.

In Curtis Hanson’s Hand That Rocks the Cradle, we’re initially attached to the pregnant Claire Bartel, who has moved to Seattle with her husband Michael and daughter Emma. When Claire is molested by her gynecologist Dr. Mott, she reports him. The scandal drives him to suicide, and his distraught wife miscarries. She vows vengeance on Claire. Thereafter, the plot shuttles us among the activities of Claire, Mrs. Mott, Michael, the household handyman Solomon, and family friends like Michael’s former girlfriend Marlene. The result is a typical “hierarchy of knowledge”–here, with Claire usually at the bottom and Mrs. Mott near the top. We don’t know everything (characters still harbor secrets, and the narration has some of its own), but we typically know more about motives, plans, and ongoing action than any one character does.

More rarely, instead of a moving spotlight, the film may limit us to only one character’s range of knowledge. Again, scene after scene will reiterate the “lesson” of this singular narrational norm. That repetition will make variations in the norm stand out more strongly. Hitchcock’s North by Northwest is almost completely restricted to Roger Thornhill, but it “doses” that attachment with brief asides giving us key information he doesn’t have. Rear Window and The Wrong Man, largely confined to a single character’s experience, do something similar at crucial points.

Sometimes, however, a film’s opening boldly announces that it has an unusual intrinsic norm. Thanks to framing, cutting, performance, and sound, nearly all of Bresson’s A Man Escaped rigorously restricts us to the experience of one political prisoner. We don’t get access to the jailers planning his fate, or to men in other cells–except when he communicates with them or participates in communal activities, like washing up or emptying slop buckets.

The apparent exception: The film’s opening announces its intrinsic norm in an almost abstract way. First, we get firm restriction. There are fairly standard cues for Fontaine’s effort to escape from the police car that’s carrying him. Through his optical POV, we see him grab his chance when the driver stops for a passing tram.

The film’s title and the initial situation let us lock onto one extrinsic norm of the prison genre: the protagonist will try to escape. Knowing that we know this, Bresson can risk a remarkable revision of a stylistic norm.

Fontaine bolts, but Bresson’s visual narration doesn’t follow him. The camera stays stubbornly in the car with the other prisoner while Fontaine’s aborted escape is “dedramatized,” barely visible in the background and shoved to the far right frame edge. He is run down and brought back to be handcuffed and beaten.

The shot announces the premise of spatial confinement that will dominate the rest of the film. The narration “knows” Fontaine can’t escape and waits patiently for him to be dragged back. In effect, the idea of “restricted narration” has been decoupled from the character we’ll be restricted to. This is the film’s first, most unpredictable lesson in stylistic claustrophobia.

Got a light?

Most intrinsic norms aren’t laid out as boldly as the opening of A Man Escaped, but ingenious filmmakers may provide some variants. Take a fairly conventional piece of action in a suspense movie. A miscreant needs to plant evidence that incriminates some innocent soul.

In Strangers on a Train, that evidence is a cigarette lighter. Tennis star Guy Haines shares a meal with pampered sociopath Bruno Antony, whose tie sports colorful lobsters. Bruno steals Guy’s distinctive cigarette lighter.

Bruno has proposed that they exchange murders: He will kill Guy’s wife Miriam, who’s resisting divorce, and Guy will kill Bruno’s father. Bruno cheerfully strangles Miriam at a carnival, aided by the lighter.

When Guy doesn’t go through with his side of the deal, Bruno resolves to return to the scene of Miriam’s death and leave the lighter to incriminate Guy. The film’s climax consists of the two men fighting on a merry-go-round gone berserk. Although Bruno dies asserting Guy’s guilt, the lighter is revealed in his hand. Guy is exonerated.

Once the lighter is introduced in the early scenes, it comes to dominate the last stretch of the film. In scene after scene, Hitchcock emphasizes Bruno’s possession of it. Sometimes it’s only mentioned in dialogue, but often we get a close-up of it as Bruno looks at it thoughtfully–here, brazenly, while Guy’s girlfriend Ann is calling on him.

When Bruno picks up a cheroot or a cigarette, we expect to see the lighter.

One of the film’s most famous set-pieces involves Bruno straining to retrieve the lighter after it has fallen through a sidewalk grating.

Bruno has dropped it before, during Miriam’s murder, but then he notices and retrieves it. It’s as if this error has shown him how he might frame Guy if necessary. The image of the lighter in the grass previews for us what he plans to do with it later.

What does the lighter have to do with norms? Most obviously, Strangers on a Train teaches us to watch for its significance as a plot element. It’s not only a potential threat, but also Bruno’s intimate bond to Guy, as if Bruno has replaced Ann, who gave Guy the lighter. The film also invokes a normalized pattern of action–a character has an object he has stolen and will plant to make trouble–and treats it in a repeated pattern of visual narration. The character looks at the object; cut to the object; cut back to the character in possession of the object, waiting to use it at the right moment. Our ongoing understanding of the lighter depends on the norm-driven presentation of it.

Once we’re fully trained, Hitchcock no longer needs to show us the lighter at all. En route to the carnival to plant the lighter, Bruno lights a cigarette with the lighter, although his hands conceal it. But then the train passenger beside him asks for a light.

In order to hide the lighter, Bruno laboriously pockets it and fetches out a book of matches.

If we saw only this scene, we might not have realized what’s going on, but it comes long after the narrational norm has been established. We can fill out the pattern and make the right inference. Bruno wants no witness to see this lighter.

The hand that cradles the rock

In The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, under the name Peyton Flanders, Mrs. Mott becomes nanny to Claire’s daughter and infant son. Pretending to be a friendly helper, she subverts Claire’s daily routines and her trusting relationship with Michael. As in most domestic thrillers, the accoutrements of upper-middle-class lifestyle–a baby monitor, a Fed Ex parcel, expensive cigarette lighters, asthma inhalers, wind chimes–get swept up in the suspense. Peyton weaponizes these conveniences, and through a somewhat unusual narrational norm the film trains us to give her almost magical powers.

We get Peyton’s early days in household filtered through her point of view. Classic POV cutting is activated during her job interview. She notices that Claire’s pin-like earring drops off and she hands it back to her.

Attachment to Peyton gets more intense when she sees the baby monitor and then fixates on the baby.

We’re then initiated into her tactics, and to the film’s way of presenting them. Serving supper, Claire doesn’t notice that her earring drops off again. Peyton does.

Breaking with her POV, the narration shifts to Claire and Michael talking about hiring her. But this cutaway to them has skipped over a crucial bit of action: Peyton has picked up the earring. Unlike Hitchcock, director Curtis Hanson doesn’t give us a close-up of the important object in the antagonist’s hand. In a long shot we simply see Peyton studying her fingers. Some of us will infer what she’s up to; the rest of us will have to wait for the payoff.

After another cutaway to the couple, Peyton “discovers” the earring in the baby’s crib. Her show of concern for his safety seals the hiring deal and begins her long campaign to prove that Claire is an unfit mother.

This elliptical presentation of Peyton’s subterfuges rules the middle section of the film. Selective POV shots suggest what she might do, but we aren’t shown her doing it–only the results. For instance, Claire lays out a red dress for a night out. Peyton sees it, then sees some perfume bottles.

Cut to Claire and then to an arriving guest, and presto. When she returns to the mirror, her dress is suddenly revealed as having a stain.

Later, Claire agrees to send off Michael’s grant application during her round of errands. Once she gets to the Fed Ex office, she will discover the missing envelope. Before that, though, we get another variant of the intrinsic norm showing Peyton’s trickery.

In the greenhouse, while Claire is watering plants, Peyton spots the envelope in her bag. We don’t see her take it, and there’s even a hint that she hasn’t done so. A nifty shot lets us glimpse her yanking her arm away as Claire approaches. It’s not clear that she has anything in her hand.

In what follows, the narration confirms Peyton’s theft while building up the threat level.

If she’s caught, this woman will not go away quietly.

While cozying up to the children–Peyton cuddles with Emma and even secretly breast-feeds baby Joe–Peyton eliminates all of Claire’s allies. By now we know her strategy, so after she suggests to Claire that the handyman Solomon has been molesting little Emma, all the narration needs is to show us Claire discovering a pair of Emma’s underwear in his toolbox. As with Bruno’s pocketing the lighter in Strangers on a Train, we’re now prepared to fill in even more of what’s not shown: here, Peyton framing Solomon.

Michael, a furtive smoker, sometimes shares a cigarette with Marlene. So it’s easy for Peyton to plant Marlene’s lighter in Michael’s sport coat for Claire to discover. Again, the moment of the theft has given her quasi-magical powers. She sees Marlene’s lighter in her handbag in the front seat.

Again thanks to a cutaway, we don’t see her take it. Indeed, it’s hard to see how she could have; she comes out of the back seat with an armload of plants.

But later Marlene will tell Michael (i.e., us) that she’s lost her lighter, and a dry cleaner will find it and show it to Claire.

The attacks have escalated, with Claire now suspecting Michael of infidelity. She confronts him without knowing that Michael has invited friends to a surprise party for her. Her angry accusations are overheard by the guests, and this public display of her anxieties takes her to a new low.

Peyton’s revenge plan is almost wholly consummated, so we stop getting the elliptical POV treatment of her thefts. Instead, the plot shifts to investigations: first Marlene discovers Peyton’s real identity, with unhappy results, and at the climax Claire does. Her POV exploration of the empty Mott house counterbalances Peyton’s early probing of Claire’s household. When she sees Mrs. Ott’s breast pump–another domestic object now invested with dread–she realizes why baby Joe no longer wants her milk.

This is the point, fairly common in the thriller, when the targeted victim turns and fights back.

In The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, a familiar action scheme–someone swipes something and plants it elsewhere–is handled through an unusual narrational norm. The scenes showing Peyton’s pilfering skip a step, and they momentarily let us think like her, nuts though she is. Thanks to editing that deletes one stage of the standard shot pattern, the film trains us to see how banal domestic items, deployed as weapons, can destroy a family. In the course of learning this, maybe the movie makes us feel smart.

Arguably, we’re able to fill in the POV pattern in The Hand That Rocks the Cradle because we’ve learned from encounters with movies that used the standard action scheme, including Strangers on a Train. This is one reason film style has a history. Dissolves get replaced by fades, exposition becomes more roundabout, endings become more open. As audiences learn technical devices, intrinsic norms recast extrinsic ones and some movies become more elliptical, or ambiguous, or misleading. All I’d suggest is that we get accustomed to such changes because films teach us how to understand them. And we enjoy it.

The passage about training us comes from my Narration in the Fiction Film (University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 45. I discuss norms in blog entries on Summer 85, on Moonrise Kingdom, on Nightmare Alley, and elsewhere. A book I’m finishing applies the concept to novels as well as films.

The example of mismatched reverse angles comes from The Irishman (2019) In the first cut, Frank is starting to settle his coat collar, but in the second, his arms are down and the collar is smooth. In a later portion of that second shot, Hoffa gestures freely with his right hand, but in the over-the-shoulder reverse, his arm is at his side and it’s Frank who gets to make a similar gesture. To be fair, I should say that I found some striking reverse-angle mismatches in Strangers on a Train too.

For more on conventions of the domestic thriller, go to the essay “Murder Culture.”

Radomir D. Kokeš offers an analysis of how Kristin and I have used the concept of norm. We are grateful for his careful discussion of our work and his exposition of the achievement of literary theorist Jan Mukarovský. See “Norms, Forms and Roles: Notes on the Concept of Norm (not just) in Neoformalist Poetics of Cinema,” in Panoptikum (December 2019), available here.

Strangers on a Train (1951).

Five critics, one of them a killer

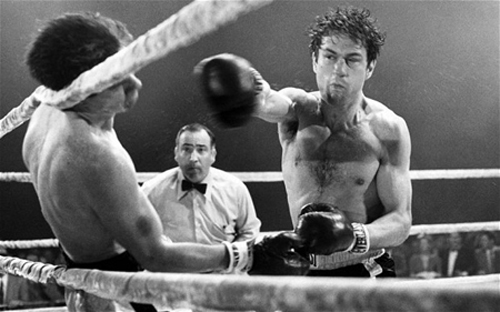

Goodfellas (1990).

DB here:

Fourteen months of being house-bound gave me plenty of chance to catch up on my reading. But the reading was almost all devoted to the book I was writing on mystery plots in fiction, film, and other media. Now that it has been catapulted out to unwary publisher’s readers, it’s time for me to catch up on some 2020 books I like. In this batch, all have a connection to film criticism, and murder, attempted or consummated, creeps into more than one.

Movies for Muggles

Somebody ought to write a history of the one-movie monograph. Early on there were picture books, and roadshow attractions often produced pretty laminated books as souvenirs, filled with PR stories and color images. My vote for the first analytical monograph would be the very ambitious Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima! (1962). In the early 1970s, American academic presses began offering critical studies of single films; an early example was the FilmGuide series edited by Harry Geduld and Ron Gottesman. (My favorite entry was Jim Naremore‘s study of Psycho.) Since then many publishers have pursued the format, usually as part of a series.

Now we have 21st Century Film Essentials, newly launched at the University of Texas Press. The first two entries are pretty canon-busting. Dana Polan writes on The Lego Movie, and Patrick Keating on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. I haven’t seen Polan’s book, but Keating directly takes up the challenge of the series.

As a franchise film, as a work of digital cinema, as a work of collaborative authorship, and above all as a thoroughly engaging demonstration of the art of storytelling, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is an essential work of twentieth-first century cinema.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

Keating’s argument for the film’s richness, I think, revolves around two central concepts. First is that of narrative viewpoint. Virtually all of Azkaban, unlike the earlier entries in the franchise, is filtered through the consciousness of Harry. We’re attached to him as he experiences the action. That doesn’t, Keating hastens to add, make the film radically subjective; indeed, there are relatively few shots from Harry’s optical viewpoint. Attaching the unfolding plot to a character doesn’t rule out a wider perspective, if only because cinema puts him within a wider frame of a shot or an edited sequence. There’s always the possibility of our registering action or other characters’ reactions. The end of the Quidditch flight is thick with these impacted viewpoints, and elsewhere Cuarón’s constantly moving camera nudges us toward implications that supplement, or sometimes contradict, what Harry is concentrating on.

Keating’s other main concept is connected to the broadening of viewpoint: worldbuilding. This idea is obviously central to Rowling’s achievement, as it has been to franchises since Star Wars. But Keating lifts the idea to a central role in how films engage us. The richly realized world of Potter is only an extreme instance of what every narrative does. Borrowing from critic V. F. Perkins, Keating suggests that any film narrative supplies us with the possibility of many stories that are only hinted at, or merely latent.

Most movies prune those secondary offshoots, the better to force us to concentrate on our protagonist. But Tom Stoppard showed that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern deserved their own play. Similarly, franchise films, with the ever-present prospect of sequels, crossovers, or reboots, make us aware that any character, even any item of furniture, secretes a new story, or a bunch of them. The Potter films are committed to this spinoff aesthetic, packing in as many suggestions of sidestories as the screen will bear. This principle finds tangible expression in the portraits jammed into the Gryffindor common room and dorms guarded by the Fat Lady.

Overwhelming us with characters and situations, many in motion, this gallery is perfectly in keeping with English traditions of floor-to-ceiling decor. It’s also a groaning feast of other stories that could yet, somehow, intersect with Harry’s fate. Keating’s shrewd commentary on worldmaking is one of the book’s highlights.

Keating ties these ideas to phases of production and division of labor, reviewing how the novel’s viewpoint and worldbuilding strategies are transposed and extended by script, camerawork, editing, performances, set and costume design, and music. Throughout he weaves what he takes to be the film’s binding theme, that of time. Is the future preordained, as Ms. Trelawney insists in her frantic, fumbling lectures? Or is it open, as Hermoine and others tell Harry? This makes the film’s tour de force climax with the Time Turner into a synthesis of restricted viewpoint (we’re with Harry as he witnesses an alternative future) and worldbuilding (the future is what you make it).

I might quarrel with Keating’s suggestion that the impulse driving Harry’s action is a struggle with the dementers. I saw his relation to Sirius Black as more than the subplot Keating considers it. Overall, though, Keating has produced not only a subtle, supple analysis of the film but also a model for how to understand cinematic storytelling in the age of the blockbuster.

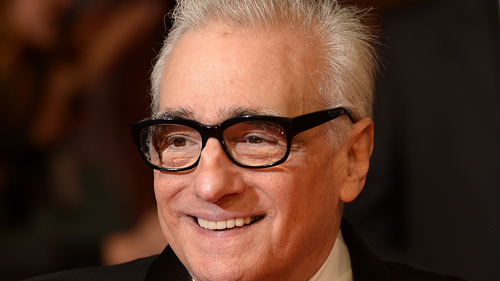

Wiseguy’s progress

If Keating’s book is a classical sonata, Glenn Kenny’s Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas is bop. Keating offers a tidy analysis through crisply defined categories. Kenny provides a hardcopy approximation to a packed DVD.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

It’s overwhelming. Kenny has evidently read everything about the real-life sources of the story, and his interviews turn fan service toward crime reporting. It is no small thing to pursue hard cases who were recruited for bit parts. Kenny has also garnered a lot of information from staff like AD Joseph Reidy, who are seldom given much attention. Keating would probably be happy to see Kenny’s narrative splinter into stories leading to other stories, such as the effects of the film on the careers of Barbara De Fina and Ileanna Douglas.

I compared the book’s central chapter to a DVD commentary. Anybody delivering a voice-over play-by-play regrets that you have to keep up with the film and can’t devote as much time to a big scene as you might like. Thanks to the print format, Kenny is able to pause the film and spiral out from it to fill in backstory or behind-the-scenes dynamics.

Early on, he can give us three pages on Tuddy, both his original (who died in prison) and Frank DiLeo, the actor playing the role. Kenny explains that DiLeo was a music executive who oversaw Michael Jackson’s “Bad” video, which included a Wanted poster of Scorsese in a subway scene, which ties to a sneaky reference to the “Smooth Criminal” video featuring a character named Frank Lideo, played by Joe Pesci. . . well, you get the idea. Likewise, in an astonishing cadenza, Kenny identifies every actor and wiseguy in the long POV tracking shot in the Bamboo Lounge.

His account of the cast rummages through filmographies and personal histories, and adds the sort of oversharing we welcome: “Behind the placid mook mug seen in the movie was a remorseless killer.”

All these exfoliating tales don’t conceal a sustained performance of film criticism. Kenny’s governing idea is that Goodfellas cons us through a bait and switch. Lured in by a rapid-fire opening that arouses a bemused attraction to these bad boys, we’re gradually forced to a more sober, even horrified, realization of their moral and emotional brutality. I think that this fairly reflects most viewers’ experience. But how does the trap work?

Kenny plots an “arc of disengagement” between the killings of Tommy and Spider. A rise-and-fall pattern links the parallel scenes of the Bamboo Lounge, the Copacabana, and the shabby tavern where the gang meets to whack Morrie. Kenny draws nuanced comparisons with The Godfather and is very detailed on Scorsese’s visual techniques, particularly the freeze-frames and fadeouts, which usually get less attention than the flashy camera moves. One of the book’s main points is that Scorsese, newly aware of how TV commercials trained viewers in quick pickup, deliberately decided to make his fastest-paced movie. And of course the music is central to managing our mood and commenting on the story.

As a seasoned reviewer, Kenny can write. “Frisky newlyweds still hot for each other; you love to see it.” Henry (“a walking appetite”) eventually pulls Karen into his schemes: “The revitalized marriage will find its sense of twisted teamwork.” And digression is welcome when it humanizes the author. Listening to Sid Vicious’ version of “My Way” is comparable to “say, eating the fried chicken from the Kansas City restaurant Stroud’s for the first time.” (The “say” makes the sentence.) A movie about food begs the critic to sample a little synaesthesia, with music evoking mouth-watering chicken. Come to think of it, that linkage of music and food is in Goodfellas too.

I especially enjoyed Kenny’s rebuke to fans who bust this carefully constructed work into “movie moments.” You probably know that one school of criticism thinks that films are more or less loose assemblages of scenes, out of which certain instants become incandescent. Certainly there are such moments in many movies, and sometimes they stand out from a gray pudding. But often strong moments ravish us because they’ve been prepared for by careful craft. So Kenny’s guided tour of Goodfellas shows its affinities with Keating’s holistic approach:

Serrano and his crew reduce movies to anthologies of “cool” or shocking moments, as opposed to fictions whose circumscribed worlds aspire to create beauty or sorrow or horror or joy in some formally coherent whole.

Mon semblable, mon frère.

Dead end at the ocean’s edge

La La Land (2016).

On the other hand, I ought to be out of sympathy with Mick LaSalle’s Dream State: California in the Movies. It’s unabashedly reflectionist, tracing how films project contradictory images of the Golden State. The screen image of California promises pure self-fulfillment, but that leads to loneliness, danger, conformity, and loss of dignity. If Kenny and Keating see movies as made by an army of artisans, LaSalle treats them as springing full-blown from American mythology. There is barely a mention of a director, let alone a sound mixer, in his account.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

I’ve explained elsewhere (here and here) why I find such claims unpersuasive. I think that reflectionism is every smart person’s mistaken idea about cinema. But sometimes, as with Susan Sontag’s essay “The Imagination of Disaster,” a reflectionist account of a film can activate some valuable ideas and information along the way, and it can host some entertaining writing. These benefits, I think, emerge throughout Dream State. In kaleidoscopic bursts, LaSalle provides suggestive takes on movies familiar and obscure, and the way they link to one another.

For example, he tracks recurring plot patterns. There’s California’s version of the One Great Night, when individual transformation takes place in a few hours of turbid activity (Superbad, Modern Girls). American Graffiti is the prototype, and in just two pages LaSalle evokes the way audience knowledge races ahead of the characters, far into the future. (Curt winds up in Canada, which probably has to be explained to young viewers today.)He’s very good on the cost-of-stardom plot, from What Price Hollywood to La La Land, this last the only film that faces the fact “that every great advance requires sacrifice, and that even though there is nothing like the joy of first love , there is nothing more important than the fulfillment of one’s inner self.”

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

Another critical avenue that LaSalle opened up for me was iconographic: the differences between LA movies and San Francisco movies. He deftly contrasts the ambience and topography of the cities. Noir and disaster films are primarily anchored in LA, while San Franciso movies tend to be steeped in nostalgia (e.g., Jobs, Milk). He keeps finding new angles to comment on. Avoiding the obvious effort to discuss California’s boom during and after the war, he skips back to the months around Pearl Harbor to bring to light films, mostly exploitation quickies like Secret Agent of Japan and Little Tokyo, USA, that rushed to treat Japanese Americans as potential spies. Meanwhile, the unoffending citizens were shipped off to internment. On a lighter note, anybody who’s bold enough to praise Gidget as a more mature film than Easy Rider gets my admiration (and agreement).

LaSalle, who came to California from the east, weaves in bits of memoir that highlight his main theme. And like Kenny, he writes with conversational wit.

“Home is horrible. Oz is horrible, too. . . but at least it’s in color.”

On Saturday Night Fever and Grease: “One seems tough, but it’s soft. (Of course, that’s the New York film.) One seems soft, but it’s hard. (Of course, that’s the Los Angeles film.)”

In Hollywood “integrity is so original it might just work as a strategy.”

In Out of the Past, “sex can kill you, but it’s worth it anyway.”

In San Francisco (1936) “if only to get Jeanette MacDonald to stop singing, the Earth had to intervene.”

Contrasting Monterey Pop to Woodstock‘s utopian fantasy, LaSalle nearly had me on the floor.

This is a model? Hundreds of thousands of intoxicated people, unable to wash, all but sitting in their own slop, cheering for a series of aristocrats that swoop down to entertain them and then leave? Meanwhile, the army flies in food and the slave classes clean out the Port-O-Sans? That’s sustainable as a societal model?

In addition to all this, through engaging appreciation, LaSalle has prompted me to seek out a great many films I hadn’t heard of. That’s another duty of the good critic. After seeing so much–pounding the beat every day–the movie reviewer can steer you to new discoveries.

Cinephile into cineaste and back again

He Said, She Said (1991).

All of these critics have participated in filmmaking. Mick LaSalle has written and produced documentaries. Glenn Kenny has been an actor in several films (including Soderbergh’s Girlfriend Experience). Patrick Keating, who has an MFA in cinematography, has been a DP on independent projects. Reciprocally, director Ken Kwapis started out wanting to be a film critic–in third grade, no less.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

Kwapis intercuts three sorts of chapters. There is the chronological account of the filmmaking process, with advice on taking meetings, establishing rapport on the set, giving actors “playable notes,” and coping with postproduction and marketing. Kwapis insists at every turn that you need to be both firm and flexible, open to every suggestion from the production team but still adhering to your conception of the project.

But this is not auteurism on steroids. If you’re not a Spielberg or a Nolan, the director has to learn tact and strategy. Kwapis emphasizes not abstract technique but the interactive, interpersonal demands of filmmaking, He suggests ways of responding to producers’ notes or actors’ complaints that allow everyone to keep their dignity. Just stepping away from the Video Village, that cluster of people around the monitor, and positioning yourself by the lens is a way of proactively steering the scene. He even gives good advice about bad reviews. His creative process? “I want to stand behind the camera and make sure there’s something alive going on in front of it, something recognizably human.”

A second batch of chapters shows this aesthetic/ethos in action through case studies from Kwapis’ career. Starting with Follow That Bird (1985), the Big Bird movie, and running up to A Walk in the Woods (2015), these chapters are about concrete problem-solving. How do you direct puppets? Or orangutans? Or Rip Torn? How do you support an actor who’s just not physically up to the role? There’s a fascinating account of staging options in The Office, where different situations force choices between developing the action in the “bull pen” or in the conference room.

The 1990s were rife with narrative experiments, and He Said, She Said (1991) was one of them. Unfolding over two days, its first part uses flashbacks to present Dan’s memory of his romance with Lorie, while the second part shifts to her version, with replays and gap-filling scenes that show the biases of his account. Kwapis and his wife Marisa Silver (Permanent Record) decided to divide responsibilities, with him directing the man’s scenes and her directing the woman’s. They also built in stylistic differences.

We pre-visualized each version to create as much contrast between Lorie’s and Dan’s personaities as possible. For example, I often show Dan’s literal point of view of Lorie, while Marisa uses camera movement and choreography to underscore how Lorie feels about herself (i.e., insecure).

They created specific ground rules for shooting the scenes. Kwapis’ portion came first, so that Silver could see it and fine-tune the replay. Kwapis is admirably specific about how their strategy shaped performance and plot, with minor characters in one half becoming major in the second.

In other words, a cinephiliac idea. (Kwapis prepared for his task by watching Rashomon, The Killing, and Citizen Kane.) The third type of chapter he offers is pure, sharp film criticism, always informed by the demands of craft. His account of American Graffiti is quite different from LaSalle’s, but no less appealing, emphasizing Curt’s visit to Wolfman Jack as an epiphany that needs no formal underlining (“no ham-fisted push-in”).

Other chapters scrutinize 2001, Lawrence of Arabia, The Graduate, I Vitelloni, and other classics. Without being pretentious Kwapis manages to invoke the “objective correlative” (e.g., shoes in Jojo Rabbit) and reflexivity (no big deal). I especially appreciated his detailed analysis of staging in a scene often overlooked in The Magnificent Ambersons: George’s confrontation with a gossipy neighbor, handled in one deftly choreographed close framing.

Kwapis designed the book to explore these three dimensions, but he isn’t puritanical about keeping them apart. Case studies and problem-solving pop up in the general advice sections, and the critical acumen shines through even brief examples of on-set tips (e.g., decisions about a score for Traveling Pants). It all flows together.

The result ranks with Sidney Lumet’s Making Movies and Alexander MacKendrick’s On Film-Making, the most acute personal reflections on Hollywood directing. But like those, it’s more than a testament to the power of craft. It’s also a vision of how, as the first chapter says, to go “beyond success and failure in Hollywood.” You do it, Kwapis maintains, by knowing your plan, respecting your co-workers, inviting discovery through accidents, and staying humane. I like to think that studying films as a critic helped him get there. Not every director, after all, can quote Jean Renoir.

“Only a hack cares about the goddam script”

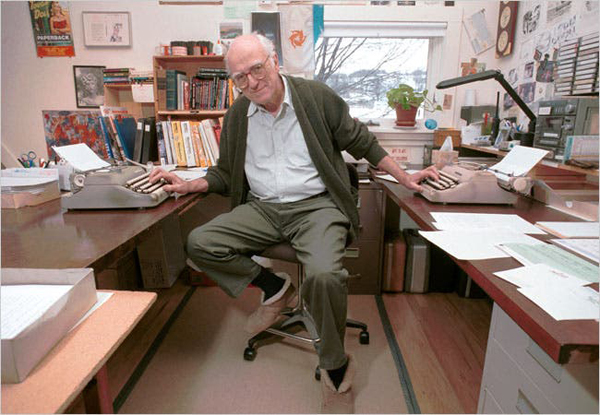

Donald Westlake (David Jennings for the New York Times).

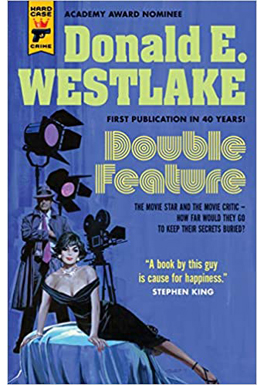

I promised you a murderer, and he arrives in Donald E. Westlake’s Double Feature, a pair of novellas originally published as Enough (1977). The second, Ordo, takes place in Hollywood, when a sailor learns that his first wife has become a movie star and decides to look her up. It’s remarkable in several ways, but the story that grabbed me was A Travesty. On the first page a film critic kills his girlfriend.

True, it’s an accident, but even then he seems less distressed than he should be. He wipes down the crime scene and slips out. Of course he becomes a suspect. Once he seems to be cleared, the trusting cop lets him mosey along on later investigations. They discover that the critic has a knack for solving crimes, including an old-fashioned locked-room puzzle. He gets caught thanks to a plot twist that owes a good deal to Westlake’s early days writing happily overblown softcore porn.

True, it’s an accident, but even then he seems less distressed than he should be. He wipes down the crime scene and slips out. Of course he becomes a suspect. Once he seems to be cleared, the trusting cop lets him mosey along on later investigations. They discover that the critic has a knack for solving crimes, including an old-fashioned locked-room puzzle. He gets caught thanks to a plot twist that owes a good deal to Westlake’s early days writing happily overblown softcore porn.

The plot lives up to its title, being a travesty of whodunits and man-on-the-run thrillers. Westlake invokes mystery conventions like the dying message and the final twist: “As with all Least Likely Suspects, I was in reality the Murderer.” But this guilty protagonist is writing a profound essay on Top Hat and interviewing an over-the-hill director who undermines his belief in the auteur idea that “it’s up to the director to color and shape the material and so on.”

A: Yeah, that’s fine, but you got to have the material to start with. You got to have the story. You got to have the script.

Q: Well. . . . I thought the director was the dominant influence in film.

A: Well, shit, sure the director’s the dominant influence in film. But you still gotta have a script.

Well, that wasn’t any help. What was I supposed to do, go ask three or four screenwriters for suggestions?

A Travesty reveals that Westlake followed East Coast cinephile taste pretty closely. In the passage after this one, the killer regrets placing Brant so high in the Pantheon–a clear reference to Andrew Sarris’s writings. Better to ask a real director like Hawks or Ford or Hitchcock, or even Fuller.

Hip movie references are de rigueur in most mysteries today. (Grudge-reading The Woman in the Window, I thought: Just kill me now.) But how many thrillers in 1977 invoked Marion Davies or Manny Farber’s Negative Space? Our anti-hero argues with a girlfriend about circumstantial evidence in The Wrong Man and Call Northside 777. And as you’d expect, the big clues that reveal the killer to her come from Gaslight.

Westlake has long been one of my heroes; his Richard Stark novels get a chapter in that manuscript I mentioned at the outset. (Go here and here to gauge my dedication.) Like Elmore Leonard, he had a pragmatic approach to movie versions of his work. As far as I know, he complained only of Godard’s handling of The Jugger, which became Made in USA, not that anybody could tell. He wrote screenplays, notably The Stepfather (1987) and The Grifters (1990), and many of his stories have been adapted to the screen (Point Blank, The Outfit).

Nearly all his work I know has a zesty playfulness, and A Travesty is no different. It suggests that, after shooting down movies and destroying reputations, film critics have earned a chance to kill for real. They just turn out to be fairly bad at it.

My stack of reading has barely dwindled. I’ll try to file some more book reports as summer unfolds and the mosquitos discover our shady lawn.

Thanks to Patrick Keating and Mick LaSalle for sending me copies of their books, though I would have bought them anyway. Thanks especially to Patrick Hogan for telling me of his friend Ken Kwapis’s book.

Philip Pullman, a master of the sort of world-building Keating celebrates, argues against dwelling on the story spinoffs harbored by a richly realized milieu. He borrows the scientific idea of “phase space” to suggest that too great a concentration on the indefinitely large possibilities of a story world can freeze a narrative’s progress and distract the reader from the through-line. A story, he says, is a path through a forest and readers are best gripped by sticking to Red Riding Hood’s journey. (Compare Sondheim’s Into the Woods.) Interestingly, he compares this strategy to the cinematic idea of knowing the right spot for the camera, a spot that’s just as valuable for what it excludes as for what it shows. See Daemon Voices: On Stories and Storytelling (Vintage, 2017), 20-24, 122-123.

For more on Parker Tyler, see the chapter in my The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture. Avoiding straight reflectionism, Tyler saw the film world as its own sealed-off realm. If the movies reflect anything, it’s not what America thinks but what Hollywood thinks that America thinks. Or rather, what Hollywood imagines that America dreams.

In this entry I write about some of the anti-Japanese films Mick LaSalle discusses.

This entry analyzes the pseudo-documentary style of The Office. I write about 1990s as an era of narrative experimentation in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies.

No admirer of Westlake can ignore the addictive Westlake Review or, of course, the official webpage maintained by his son Paul. Westlake’s motto: “My subject is bewilderment. But I could be wrong.”

American Graffiti (1973).

Captain Cinephilia: Scorsese strikes back

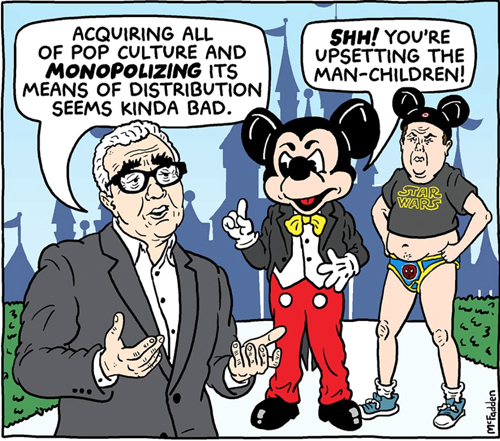

Brian McFadden, No One Is Safe: Martin Scorsese Roasts Your Fandom.”

DB here:

It started with a brief, almost offhand remark.

“I don’t see them,” [Scorsese] says of the MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe]. “I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well-made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

When I learned about this interview (Empire, November issue), I took it as simply a roundabout statement of personal taste. Scorsese doesn’t find Marvel movies, and perhaps other comic-book sagas of superheroes, to his taste. He gave them a fair shot, but he now no longer sees them. He considers them visceral stimulation, like carnivals or theme parks. They’re not cinema, if you consider cinema as emotional expression of psychological conflicts.

In the massive responses to Scorsese, people pointed out that viewers often respond emotionally to superhero films. They root for certain characters, they’re amused or thrilled by certain situations, and many claim to be deeply moved by the heroes and villains (Loki, even Thanos). In fact, it’s exactly the “emotional, psychological experiences” embedded in the Marvel and DC plots that some fans say distinguish them from crude comic-book movies that went before. Much the same could be said of the Bond films, which became more humanized with Quantum of Solace, though intermittently before.

As for the claim that the superhero films “aren’t cinema,” I wasn’t really upset. Over the decades we’ve heard that 1910s films “aren’t cinema” (too theatrical), or that adaptations of novels or plays “aren’t cinema” (too literary or stagebound), or that narrative films “aren’t cinema” (usually proposed by avant-gardists). When the claim relies on a notion of some cinematic essence (editing, or pure visual form) that’s missing from this or that movie, you might be able to have a productive conversation. But if “This isn’t cinema” comes down to “I don’t like films like this,” we’re back to personal taste.

On other occasions Scorsese went on to say a lot more. The ultimate result was a 7 November article in the New York Times. I think we should take this as his most thoroughgoing effort to explain his thinking. We can supplement that with some remarks he made in interviews and Q & A sessions.

Herewith my attempts to figure out Scorsese’s argument. Trying to sort this out might teach us some important things about film now.

Scorsese in defense of Cinema

Scorsese’s Times article, “I Said Marvel Movies Aren’t Cinema. Let Me Explain,” begins by disclaiming any hatred for Marvel movies as such. “The fact that the films themselves don’t interest me is a matter of personal taste and temperament.”

But everyone’s taste gets shaped by their moviegoing experience, and in his youth Scorsese was attracted to films from America and Europe. These yielded “revelation—aesthetic, emotional, and spiritual revelation.” The films were, he felt, about characters who were complex, sometimes contradictory in their minds and behavior.

Moreover, these films showed that cinema was an art form, one existing in both commercial and more experimental spheres. Hollywood studio output (Ford Westerns, Hitchcock thrillers), European imports (Bergman, Godard), and avant-garde work (Scorpio Rising)—all these showed that cinema had powers equal to those of music, dance, and literature. These films were technically accomplished, sometimes virtuoso, but at their hearts were intense, complex emotional appeals that assured that they would be watched for decades later.

Today the Marvel pictures, often skillfully made, lack “revelation, mystery, or genuine emotional danger.” They are repetitive, adhering to a basic formula, “defined as variations on a finite number of themes.” By contrast, the films of Paul Thomas Anderson, Claire Denis, Wes Anderson, and other directors offer new and unpredictable experiences, and they expand the possibilities of the art form. “The unifying vision of an individual artist” is essential to cinema.

It’s exactly the exploratory filmmakers who are being stifled by the Marvel releases, and indeed all the franchises. These more personal films aren’t just constrained by lower budgets; they can’t get much exposure on theatre screens either. “Around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen.” Most filmmakers design their films for that scale and that communal experience, but the blockbuster films are pushing smaller pictures into streaming outlets.

The franchise mentality is a corporate one. The products are “market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.” As often happens, the business constrains the art. But you might say, what about the old studio system? Wasn’t that as mercenary as today’s franchise juggernaut? No, because the studios set up a creative tension between the business end and the artistic end that yielded outstanding works, even masterpieces. Today’s franchise producers are indifferent to art and hold a view of film history that is both “dismissive and proprietary.”

As a result we have two domains: worldwide audiovisual entertainment vs. cinema. They overlap less and less, and it seems likely that the financial power of one will dominate and belittle the other.

I think that some of these arguments are plausible, while others deserve more probing.

Film art: Who’s the artist?

Andrew Sarris.

During the 1950s and 1960s, this general argument was promulgated by the so-called auteur critics around Cahiers du cinéma and was developed and promoted by Andrew Sarris in the US and Movie magazine in the UK. Scorsese was deeply influenced by these ideas. He was one of many cinephile directors-in-training who assumed that the best films bore the “unifying vision of the individual artist,” who was the auteur (author) of the film.

What was considered the “auteur theory” is too complicated to explore fully here. Minimally, it’s the idea that, all other things being equal, in many movies (often the best ones) the director can be considered the source of the film’s distinctive artistic qualities. The director may achieve this by exercising near-total control (e.g., Chaplin), or working with close collaborators (Powell and Pressburger, Donen and Kelly) or serving as a “filter” for the offerings of various contributors (probably most filmmakers).

This is the minimal case. The maximal one rests on the idea that once we make the director the central power, we then discover a “unifying vision.” At this level the distinctive features of form, style, and theme coalesce into a personal conception of human life. For Ford, that might include the value of traditions and the costs they demand of those subscribing to them. Hitchcock’s recurring concern, Robin Wood famously argued, is the realization that complacency, a trust in social order, is vulnerable to disruption.

The difference between the two versions I’m sketching isn’t hard and fast. Still, it often holds good. A friend, for instance, grants that Tony Scott is a distinctive filmmaker. “He just has nothing to say.” The idea that an auteur has something consistent and personal to “say,” deliberately or unconsciously, from film to film, is a hallmark of auteur criticism at its most ambitious. And the greatest auteurs, perhaps, show development in what they say across their careers. John Ford’s attitude toward the frontier can be said to change from The Iron Horse (1924) to Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

The minimalist auteur concept isn’t new. From the 1920s on, historians and critics often attributed creative authority to Griffith, Chaplin, De Mille, Hitchcock, and European and Soviet directors. And in most film industries, executives recognized that the director had the most responsibility for the film’s look and feel.

One revolutionary edge of auteur criticism was to discover auteurs nobody had noticed before–largely unknown filmmakers working alongside humbler folk. And the critics went further, suggesting that some of these filmmakers could be considered auteurs to the max.

Typically auteur critics didn’t examine the concrete context of production to determine who did what in particular cases. They inferred directorial expression by watching lots of films and tracing recurring strategies of style and theme. Sometimes they backed their conclusions up by interviews with–who else?–the director.

Minimal versions of the auteur idea are central to film culture now. Festivals promote directors, as do studio marketers. Movie lists in reference books and search sites give directors the pride of place. Variety and Hollywood Reporter reviews usually don’t name producers, cinematographers, and other contributors, but the director is always mentioned (and blamed or praised for the film). Academics and cinephile critics ascribe more maximalist “personal visions” to directors around the world, from David Lynch and Spike Lee to Wes Anderson to Wong Kar-wai and Jane Campion.

Auteur +genre = ?

Black Panther: Danai Gurira (Okoye), Ryan Coogler on the set.

Despite the prominence of some directors, they’re usually not what draws audiences. In most countries, the mass-market cinema is dominated by genres that are populated by well-known stars.

Sarris and others assumed that auteurs built upon the foundations provided by genre conventions and star images. Ford gave the Western a new force not only through his images and use of music but also by redefining the star personas of John Wayne and Henry Fonda. Hitchcock and Lang worked with and against the conventions of the thriller, while Ophuls gave the melodrama a melancholic elegance. Or so goes auteur gospel.

The 1970s New Hollywood auteurs embraced genre filmmaking as well. Bogdanovich, Coppola, Altman, Woody Allen, and others tested themselves in a variety of genres. Even Scorsese tried a “woman’s picture” (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), a musical (New York, New York), and a biopic (Raging Bull). They are only roughly parallel to today’s indie filmmaker who, after a breakthrough project at Sundance or SxSW, signs on to make a franchise picture.

As a generous and enthusiastic cinephile, Scorsese has long subscribed to a version of auteurism. Perhaps one source of his misgivings about Marvel and its counterparts is that he can’t detect auteurs in these movies. Does that mean they aren’t there? Is today’s studio cinema largely a genre cinema, minus the classic bonus of high-end auteur expression?

One of his comments has attracted little notice. Scorsese remarks of the theme-park picture:

The technique is very well done but there is only one Spielberg, there is only one Lucas, James Cameron. It’s a different thing now.

This implies that even the franchise genres could sustain some degree of what Sarris called “directorial personality.” Admirers of Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarock, James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, or Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman might agree. This has been one line of defense in the pushback to Scorsese’s comments.

Or maybe we should attribute whiffs of personal expression today to the producers (Bruckheimer, Kathleen Kennedy, Kevin Feige). Even in Hollywood’s heyday, we sense Gone with the Wind and Duel in the Sun as Selznick productions. Then there’s Walt Disney, surely a producer as auteur. I suspect that Scorsese finds these old films more inspiring than today’s behemoths.

Closing the drawbridge on Fort Multiplex

Avengers: Endgame (2019).

A genre can rise and fall in popularity. As the Western and the musical declined in the 1970s, horror and science-fiction gained traction as both programmers and A-list blockbusters. Add in the rise of fantasy, crystallized in the prestige accorded the Lord of the Rings installments. Oddly, as comic book sales declined, comic-book movies came to be a central contemporary genre. The superhero film proved a powerful blend of all these trends.

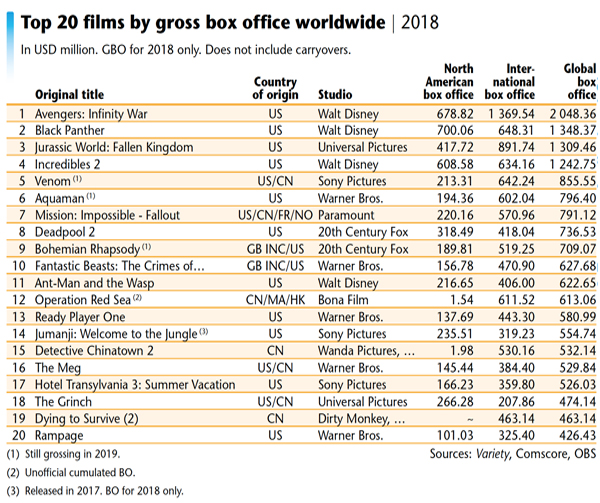

Today, the stifling presence of the fantasy/SF/comic-book franchises seems obvious. Look at two snapshots.

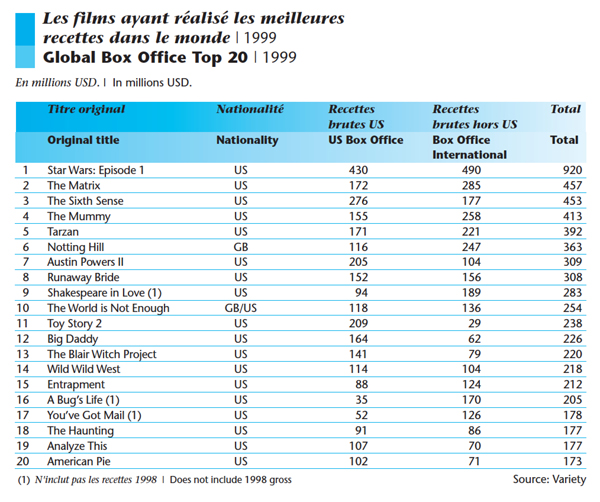

In 1999, the world’s top-grossing film was Star Wars: Episode 1. Among the twenty top hits were fantasy/SF blockbusters The Matrix and The Mummy, as well as a Bond entry. But there were also lower-budget horror films (The Sixth Sense, The Blair Witch Project). Most surprisingly, the top twenty include many comedies, mostly star-driven.

Now consider the 2018 situation.

Five of the global top ten were superhero films. The big winner was Avengers: Infinity War, which earned over two billion dollars globally–nearly twice as much as second-place Black Panther. Among the top ten are Venom, Aquaman, and Deadpool 2. Add The Incredibles as a sixth superhero film if you want. At 11 is Ant-Man and the Wasp. Most of the remaining titles are also franchise entries. There’s also the fantasy/SF blend Ready Player One, the monster movie Rampage, and the action thriller The Meg. Only China is offering live-action comedy (Detective Chinatown 2) and drama (Dying to Survive).

Of course nobody knows better than Scorsese that the big-budget fantasy/SF film has long been with us. His New York, New York (1977) came out the same year as Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, while 1980 saw the release of both Raging Bull and The Empire Strikes Back. But in those years straight-up genre films had a fighting chance. Smokey and the Bandit, The Goodbye Girl, 9 to 5, Airplane!, and others won big box-office.

Scorsese films have landed in the top twenty occasionally (e.g., The Color of Money and The Wolf of Wall Street). On the whole, though, I’m not suggesting that Scorsese now sees himself as competing with the biggest grossers. He’s surely right that today’s superhero films dominate the landscape. But do they squeeze out other films to the degree he suggests?

In some venues, probably yes. Small towns with one or two multiplexes may not have space for the minor-key movie. But bigger towns and midsize cities can be quite hospitable to them. In one week, alongside the big releases, multiplexes in my town of Madison, Wisconsin (pop. about 250,000) played Motherless Brooklyn, Jojo Rabbit, Parasite, The Lighthouse, The Current War, Brittany Runs a Marathon, and documentaries on Molly Ivins and Miles Davis. At least some of these qualify as original vehicles. At its widest release, The Lighthouse played on nearly 1000 US screens, and Jojo Rabbit arrived at over 800.

These are merely data points, not systematic samplings. And you might argue that we’re in the middle of Oscar qualifying season, so more offbeat films are numerous now. Okay, go back to July, the most competitive month for domestic releases. Nationally, the big pictures didn’t prevent the release of Yesterday, Midsommar, Late Night, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Booksmart, The Dead Don’t Die, The Biggest Little Farm, The Farewell, The Art of Self-Defense, Amazing Grace, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood.

Again, not all of these count as auteur vehicles, and several failed domestically, but they still squeezed into multiplexes. The Tarantino film obviously commanded a wide release, but many of the titles I mentioned played on between 1000 and 2000 screens. Booksmart opened on over 2500, Midsommar on 2700.

The industry doesn’t depend on the smaller or more personal titles, but then it seldom has. The biggest box-office successes in the heyday of the studio system were almost never auteur classics. Variety reported that the top domestic hits of 1943 were For Whom the Bell Tolls, Song of Bernadette, This Is the Army, Stage Door Canteen, Random Harvest, Hitler’s Children, Casablanca, Madame Curie, Star Spangled Rhythm, and Coney Island. True, Frank Borzage struck gold with Stage Door Canteen, but it’s not typical of his work. Lubitsch (Heaven Can Wait) and Hitchcock ( Shadow of a Doubt) were far down the list, bested by the likes of Sam Wood, Clarence Brown, and Henry King.

Or take 1952, ruled by The Greatest Show on Earth (De Mille), Quo Vadis, Ivanhoe, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Sailor Beware, The African Queen (Huston), Jumping Jacks, High Noon (Zinneman), and Singin’ in the Rain (Donen/Kelly). True, The Quiet Man hit number 12, and Mann’s Bend in the River number 13. But of the top hundred the only other auteur pictures seem to be Pat and Mike (no. 39), Monkey Business (no, 47), Carrie (no. 54), The Lusty Men (no. 76), and Five Fingers (no. 85).

It seems plausible, then, that in Hollywood “audiovisual entertainment” has overwhelmingly dominated the market for decades. Auteurs seldom win the biggest grosses. But again Scorsese’s career history may have influenced his judgment.

There was a moment, the Holy 1970s, when genre cinema with a personal-vision inflection was occasionally lucrative. The Godfather, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, American Graffiti, Blazing Saddles, Alien, Apocalypse Now, The Shining, and other notably original productions did earn money and awards. Yet in retrospect that seems an interregnum. The top rentals of the following decade, the 1980s, were dominated by Spielberg and Zemeckis. Then there were the usual array of star-driven comedies and action pictures. Genres came back strong, and auteurs had to work within them, or around the edges.

Such is pretty much the case right now. At the top end, perhaps the superhero films are roughly equivalent to the biblical sagas, historical pageants, and theatrical adaptations that roadshowed throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Now as then, a number of auteur films are still getting theatrical releases. The blockbusters keep the lights on and the popcorn moving so that theatres can afford to wedge straight-up genre pictures and offbeat indies into their week. It seems that you can’t run Avengers: Endgame on all 22 screens.

Art vs. craft?

Anthony and Joe Russo directing Avengers: Endgame.

But maybe we shouldn’t think of the big pictures as “audiovisual entertainment.” What’s opposed to that? “Cinema,” Scorsese said. I’d propose that this formulation means “artistic cinema.” Which is to say that we’re in the realm of the classic distinction between art and entertainment.

This has given an opening to the people riled up by Scorsese’s remarks. Admirers of Marvel, DC, and comparable pictures can say that they find them as emotional, revelatory, inspiring, etc. as anything he finds in Bergman or Sam Fuller. They feel it in their bones. And who’s to gainsay that? Scorsese doesn’t have their bones, and neither do you or I.

On more objective grounds, I suggest that Scorsese has floated another distinction. Forget calling some things “cinema” and some things not. I think that he’s distinguishing craft from art.

Let’s say provisionally that craft is the skillful manipulation of the medium to produce the desired effects. Art, on this understanding, can be considered something more. It’s usually grounded in craft, but not always. It’s also formally and emotionally complex, original in its relation to what came before, and offering new experiences on repeated exposure (rather than replays of the original response). Many, like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, would add that art induces reflection on ourselves and the world, making us wiser and deepening our humanity.

From this angle, Scorsese’s recognition of the “talent and artistry” of franchise films can be seen as a nod to craft competence. “The technique,” he says, “is very well done.” Our blockbusters are comparable to many of those anonymous hits of the studio era, turned out by skillful but impersonal artisans.

In response, the MCU advocates would need to show that the films go beyond craft. For example, some advocates find in these films the kind of character complexity Scorsese attributes to Hitchcock. He finds that Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest suffers “painful emotions” and an “absolute lostness.” Marvel fans will say something like this about moments in the stories of Tony Stark, Captain Marvel, Captain America, and the Winter Soldier.

Scorsese might reply that these are not complex characters. Yet for many years people said the same about the work of Hitchcock and other Hollywood auteurs. When people started to study them, we saw things differently. Only closer analysis of the comic-book films can give us better grounds to argue about whether their characters exhibit the “contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures” Scorsese champions.

Realism and its rivals

Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014); Raging Bull (1980).

A few scattered speculations and I’m done.

I don’t know that we’ve fully recognized that these SF and fantasy franchises descend from earlier forms. Silent crime serials and installment films featuring Dr. Gar el-Hama and Judex had the same reliance on secret identities and world-threatening master villains. Chinese wuxia films gave their knight-errants the power to soar into the air (the “weightless leap”) and emit blasts of energy (“palm power”). The bullet ballets of Hong Kong films have obviously influenced Hollywood action pictures, but we haven’t acknowledged how our comic-book movies incorporate fantasy martial arts techniques. Hollywood owes Asian action cinema more than we usually admit.

But the silent policiers and the fantasy wuxia are flagrantly unrealistic. And Scorsese, more than many of his colleagues, is committed to realism. He couldn’t, I think, make Big Trouble in Little China or Kill Bill. I’d suggest he’s intrinsically out of sympathy with quasi-supernatural action. (Hugo is a historical film, and it’s about a sacred era of Cinema past.) Superhero dramaturgy, I hazard, rubs him the wrong way, and not just because it lacks psychological depth.

I’ve argued elsewhere on this blog that Scorsese makes forays into expressionist and impressionist technique, but they usually issue from a base of harsh realism. His commitment to realism may make it hard for him to engage with the more outrageous narrative conventions of the superhero film.

Here another classic dichotomy suggests itself. If you have to choose between basing your story on plot or character, Scorsese will choose character. In fantasy films, though, character motive and reaction are based on elaborate plot machinations. These films depend a lot on elaborate fake identities, as well as recognitions of hidden kinship. She’s my sister! He’s my father! Such devices serve to provide intricate genealogies and networks of relationships for fan homework.

Likewise, theatrical melodrama and adventure fiction from the nineteenth century supply superhero sagas with orphans of mysterious parentage, duels, hairbreadth escapes, family secrets, coded documents, precious but mysterious objects, and other franchise conventions. These are woven into complex schemes and counter-schemes of the sort found in the silent crime serials. But all these features run counter to the psychological conflicts that animate Scorsese’s plots.

Recognitions of kinship rely in turn on a plot strategy that’s worth discussing a little more; I suspect it yields much of the emotional resonance that fans enjoy. These films rely on courtship and romantic rivalries throughout, of course, as well as friendships forged and broken. These are standard for most American genres. But I’ve been surprised at how often family relations are developed in complicated ways.

It’s not just Star Wars. The Marvel Universe relies heavily on kinship to sustain its plots, as well as its pathos. Tony Stark and Pepper Potts have a daughter, as does Scott Lang. Hawkeye has a family, as does T’Challa, whose cousin N’Jadaka becomes a prime adversary. Nebula and Gamora are pressured to be dutiful daughters to Thanos. Thor and Loki share a mother, Frigga. You can argue that Tony Stark becomes a father-figure for Peter Parker. Other characters are more isolated, but for some of them, notably Natasha and Bucky, the Avengers team constitutes a surrogate family.

Marvel’s focus on the family asks us to exercise the skills we must bring to classic mythology, nineteenth-century novels, and TV soap operas. We need to keep track of who’s related to whom, and what in their past encounters can arouse obligations and conflicts. I don’t think that plots resting on such dense kinship relations are of great appeal to Scorsese; his families, when they’re present at all, are pretty small-scale (Raging Bull, Cape Fear, Shutter Island, The Age of Innocence).

Most of all, when Scorsese speaks of these films shying away from risk, I suspect he’d include their avoidance of narrative risk. In fantasy and SF, nobody need really die. Hero, villain, love interest, and sidekick can return in a parallel world, or they can be resuscitated through a new gadget. The worst outcome need not be the worst, as when Avengers: Endgame uses nanotech and time travel to rewrite the past. Plot mechanics again. Despite all the assurances that Tony Stark is really, really gone, we could find a way to bring him back if Downey wanted to sign on again. (Black Widow is being resurrected for a prequel adventure.) But there’s no bringing back Sport from Taxi Driver or Rodrigues from Silence—except in a prequel, another convention that Scorsese would likely disdain.

I’m just spitballing here, but for Scorsese and other stylized realists like Michael Mann, the comic-book convention of eternal return might seem merely juvenile wish fulfillment. Something really has to be at stake, and ultimates must be faced’ Danger and death are real. This is grown-up drama.

I’m not intrinsically opposed to the conventions ruling comic-book movies myself. In general, I think that plot is as underrated as character is overrated. (I’d rather give up the distinction altogether, but that’s another story.) Superhero films are mostly not to my taste, but I think they’re worth studying as intriguing contributions to trends in modern cinema. My point is just that the personal aesthetic of Scorsese, as both cinephile and cineaste, doesn’t fit very well with the elaborate, ever-changing rules of the magical MCU. He finds enough magic in a sinuous tracking shot, or a carefully synced doo-wop song, or an unexpected angle, or a wiseguy shouting match. That is Cinema.