Archive for February 2015

BIRDMAN: Following Riggan’s orders

DB here:

In a Broadway bar, the New York Times drama critic has just told Riggan Thomson that her review will destroy his play. Riggan snatches up her review of another production, reads it quickly, and declares it packed with meaningless “labels.”

There’s nothing in here about technique. There’s nothing in here about structure. Nothing here about intention.

Happy to oblige, Mr. Thomson. Spoilers ahead.

Structure: Icarus rises

Birdman’s plot covers six days at a critical period in Riggan’s life. He’s an over-the-hill movie star identified with playing the crime-fighting superhero Birdman. Now he’s directing and starring in a play he has based on Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk about When We Talk about Love.” The film’s plot starts on the day before the first preview, when during a rehearsal Riggan hires the arrogant but talented actor Mike Shiner. Three nights of more or less bungled preview performances follow. The climax comes on opening night. In the play’s suicide scene, the despondent Riggan shoots off his nose. The Times critic publishes a rave review and Riggan, recovering in the hospital, finds that he has a Broadway triumph. His response to that, however, is rather ambivalent.

The film feels a little odd—“quirky” is the official term—but its blend of comedy and drama is constructed along familiar lines. The major characters have goals. Riggan wants to prove he can do something valuable, while paying homage to Raymond Carver, who encouraged him when he was starting out on the stage. Riggan is also disturbed by his failures as a father and husband; mounting this play about love would seem to be an act of penance. The protagonist’s search for authentic success and psychological stability might remind you of 8 ½ and All That Jazz, which also endow their protagonists with flamboyant fantasy lives.

The other characters state their goals in that confessional mode typical of melodrama. (Extra motivation: in the world of the theatre people are always ready to overshare.) Mike wants to express himself artistically and to make Riggan’s play conform to his standards of honest realism. Lesley, the female lead and Mike’s girlfriend, wants to make her Broadway debut a success. Jake, Riggan’s producer, is trying to pull the whole thing off. Riggan’s scowling daughter Sam is looking for a settled life after a stint in rehab, while Riggan’s girlfriend and second lead Laura wants to have a child. As the plot develops, in true Hollywood fashion, the major characters achieve their goals.

Structurally, the plot falls into the four parts that Kristin has found to be common in Hollywood features.

The Setup lays out the premises for the action—identifying characters, explaining their motives, and articulating their goals. It’s packed with exposition, ranging from the old standby in which a character announces what the other character knows (“You’re my attorney. You’re my producer. You’re my best friend”) to the meeting with the press in which Riggan’s past as a movie star and his hope for this production are redundantly laid out. The thirty-minute setup ends with the first botched preview and Riggan’s moment with his ex-wife Sylvia. He explains that the production means everything to his self-respect.

The Complicating Action, a counter-setup which redirects character goals, centers mostly on the effects that Mike has on the show. Since he drunkenly improvised during the first preview, Riggan realizes they have to come to some understanding. Mike’s onstage antics in the second preview threaten Lesley’s hopes for a breakout career. They break up, and Mike and Sam begin flirting. Mike also steals the spotlight in a newspaper feature about the production, even swiping Riggan’s story about Carver’s encouragement. More deeply, Mike’s rants against Hollywood make Riggan feel even more fearful that his play will be a disaster and he’ll be a laughingstock. All of these anxieties come to focus in an extended inner dialogue between Riggan and Birdman, who insists that he will fail and will have nothing left. Riggan is ready to cancel the show, but Jake pushes him forward.

About an hour in, near the midpoint, we get the Development. This typically consists of a holding pattern. The plot doesn’t advance much. Riggan’s conflict with Mike deepens and his worries about the show mount. Lesley thanks him for giving her a chance, he reprimands himself again for being a bad dad to Sam, and Sam and Mike become a couple. A comic interlude, probably the film’s most widely-known scene, adds to Riggan’s debasement. He’s locked out of the theatre and, wearing just his underpants, races around the block through a Times Square crowd.

Reentering the theatre, he plays the crucial motel scene by lurching down the aisle and onto the stage, where he enacts the suicide. It’s also during the Development that Riggan meets Tabitha, the Times critic, and learns that, sight unseen, she plans to roast his play. The next morning his fantasies take over and, urged by Birdman, he enjoys a swooping and soaring flight around the theatre district.

The fourth part, the Climax, begins with the intermission during the premiere. The audience drifts onto the sidewalk, praising the first act. Backstage Riggan tries to calm his nerves. After confessing to Sylvia that he once tried suicide, he takes the pistol on stage and prepares for the motel scene. On stage, as if succumbing to Birdman’s rhetoric, Riggan confesses, “I don’t exist.” He blasts off his nose. After a brief montage, the epilogue shows us the result. Recovering in the hospital, Riggan has a successful play, a sympathetic ex-wife, and a daughter reconciled to loving him. Even Birdman, sitting on the toilet, is for once silent.

But the very last moments are equivocal and for once you won’t get the spoiler from me. Suffice it to say the tag is ambiguous in magical-realist fashion.

The plot helps us trace character change along classical lines. Key locales mark phases of the action. Sam and Mike meet on the rooftop twice, Riggan visits the bar twice, and Riggan’s ex Sylvia comes to his dressing room once in the Setup and once in the Climax. Whenever we return to the stage we see a version of either the apartment quarrel or the motel suicide. (We do glimpse, also twice, a hallucinatory scene of dancing reindeer, associated with Laura.) The main arenas are the stage and Riggan’s dressing room, which is the site of eight major scenes. The corridors snaking around the theatre serve as transitional spaces. As the film goes on, González Iñárritu tells us, the corridors get narrower and dingier. The fairly rigid time-structure of the plot finds a counterpart in a to-and-fro spatial pattern that measures Riggan’s jagged decline.

I’ve barely mentioned one of the crucial factors in the film’s narration. From the start Riggan hears the voice of Birdman admonishing him to return to superhero movies and give up this arty stuff. At certain points, it seems that Riggan gains some telekinetic powers, enabling him to smash flower pots, furniture, and light bulbs with the wave of a hand. These moments can be construed as subjective, in the sense that he “actually” destroyed them in a normal rage but felt that he was disposing of them through a superhero’s powers.

These powers are suggested at the start with an image of him levitating during meditation. They come to a kind of climax when he launches himself, a trench-coated Birdman, into the air, in a flight that serves as a counterweight to the humiliation of his naked canter through Times Square. Again, the film’s narration suggests that it’s all in his mind: after he lands and returns to the theatre, a cab driver pursues him demanding his fare.

The nagging voice of Birdman supports another kind of structure, a thematic one pitting East Coast and West Coast values. The material is traditional, being given sharp expression in The Band Wagon. The opposition goes back at least to Twentieth Century (1934, a Hollywood satire on Broadway pretensions) and Merton of the Movies (1922, a Broadway satire on Hollywood vulgarity). Of course the two artforms feed off one another. Twentieth Century started as a play, and Merton was made into a movie. The Producers began as a movie mocking Broadway, it became a hit Broadway musical, and the musical was made into another movie.

Birdman revisits these well-worn themes. Mike and Tabitha excoriate Riggan for his trashy films; only the theatre is real art. By contrast, Birdman’s croaking whispers remind Riggan that millions of ordinary folk like his blockbuster movies, while the theatre is for phonies. Mike’s narcissism and pretentiousness, the absurdity of his notion of realism, and the snobbishness of Tabitha all support Birdman’s point. As is common in such movies, the Eastern elite is shown as a pushover for superficial seriousness and ham acting. At the same time, Riggan sincerely wants to pay homage to the emotional core of Carver’s story; he may just not realize how bad the idea is.

The eternal Hollywood/Broadway opposition is sharpened in the light of new entertainment trends. Birdman tells Riggan that old superheroes—presumably those of the vintage of Michael Keaton in Batman (1989)—have it all over “posers” like Downey and the new generation. This motif refers, I think, to the modern trend toward troubled superheroes, set up in Burton’s Batman and carried to neurotic extremes in later comic-book sagas. But of course Riggan personifies the troubled superhero himself.

The sense of Riggan being old-school is reinforced by another familiar thematic duality, that of the young versus their elders. Riggan’s conflict with his daughter recycles the motif of a father so obsessed with work and seduced by false values that he ignores his daughter. (What is it with our filmmakers and this father/daughter thing? Is it just a way to pair older men with cute younger women in a safe way?) Sam berates him for being invisible in today’s world.

You hate bloggers, you mock Twitter, you don’t even have a Facebook page. You’re the one who doesn’t exist. . . . You’re not important. Get used to it.

The modern definition of entertainment includes the Internet, a realm that Riggan enters only by accident during his skivvy promenade. Sam’s denunciation reiterates Birdman’s insistence that Riggan doesn’t exist, except that she makes it worse: even if he returned to the Birdman role, no one would care.

The presentation of superheroics in Riggan’s fantasy mocks summer tentpoles, and would appear to express director Alejandro González Iñárritu’s distaste for action extravaganzas. But the movie is pretty hard on the theatre world too. It’s unfair for Mike and Tabitha to castigate Riggan now that playing a superhero has become artistically legitimate. The only performers Riggan can imagine replacing his wounded cast member are accomplished actors (Harrelson, Fassbender, Renner) who also star in franchise entertainments. The new entertainment economy shows that Riggan was a pioneer; now everybody wears a cape. But these stars routinely do serious films, even Broadway drama, along with tentpole movies. Why can’t Riggan cross over too?

The disruption that arrives when popular entertainment invades the sacred space of the theatre finds a hallucinatory expression during the climactic montage. Now street drummers and superheroes crowd the stage of the St. James. What price Tabitha’s Art of the Theatre with Spidey drawing big crowds?

At the end, Riggan earns his accolades as an actor, but what he’s been after, hinted at in the references to Icarus and the liberation of his flight over the city, is validation of his worth. Once he realizes he is indeed loved (by ex-wife, daughter, best friend), he’s happy to pay the price of his nose. He gains a new superhero cowl, a gauze-bandage mask, and a surgical version of Birdman’s beak. And now that flight is no longer fleeing, he can consider all his options.

Technique; or, Intensified continuity without cutting

This plot could easily have been presented in a manner typical of today’s moviemaking, both indie and mainstream. That is, there might have been hundreds or probably thousands of shots. But Birdman, we’re told by people who should know better, consists of a single shot.

Any viewer can see that’s not true. Depending on how you count the opening quotation from Raymond Carver (is it part of the credits, or a separate shot?), there are sixteen discernible shots in the movie. Apart from the titles, the opening gives us three quick images—a seaside landscape with jellyfish, two shots of a plunging comet—and the final portion of the film provides a montage of nature scenes, interiors, and stage performers.

Admittedly, these shots account for little of the running time. The bulk of Birdman consists of what appears as a continuous shot running a little over 101 minutes. In production, several shots were merged seamlessly into the one that we perceive. The hospital epilogue consists of another long take, that lasting about eight minutes, and it too may have been assembled from separate takes.

Filmmakers confront a lot of options for handling long takes. The boldest, probably, is the static framing that doesn’t use camera movement. This option is employed in early cinema (viz. the Lumiêre films), in the tableau tradition I’ve gabbled about fairly often, and by some very rigorous directors like Hou Hsiao-hsien, Andy Warhol, and Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet. But most films using long takes rely upon camera movement.

In Birdman, unsurprisingly, the camera movements are typical of Hollywood’s modern intensified continuity style. For example, we often get the push-in on a character close-up.

We get orthodox Steadicam movements trailing a character from behind or backing up as he or she strides toward us. This yields the familiar walk-and-talk.

And we get the standard treatment of people around a table, with the camera circling it to pick up each one’s reaction at a critical point.

To a great extent, then, Birdman’s long-take style stitches together schemas that are well-established in contemporary Hollywood. Another current device is the occasional depth shot yielded by wide angle lenses. This technique was well-established in Hollywood in the 1940s, and today’s filmmakers rely on the same sort of tools that classic cinematographers used: strong lighting and wide-angle lenses.

The wide-angle lenses used on Birdman, only 14mm and 18mm, don’t always create wire-sharp focus in depth, but they provide enough visibility to create depth effects. Sometimes the rear plane is made sharper through racking focus.

More pervasively, in many long-take films, the camera movements replicate the patterns we find in an edited scene. Editing gives the camera a kind of ubiquity: it can go anywhere. Tethered to unfolding time, the long take sacrifices the ability to change views instantly. Yet in such films the action is staged and framed so that nothing important escapes our notice. The action gets spelled out as precisely as it would if the scene were edited.

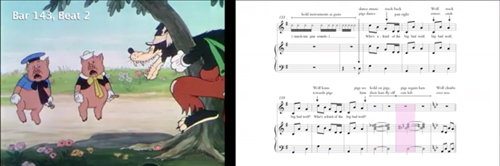

People have wondered a lot about the hidden edits that blend Birdman‘s long takes, but more important, I think, are the ways that the style adheres to standard editing patterns within its long takes. For example, the over-the-shoulder angles of shot/reverse-shot are mimicked by a camera arcing to favor first one character, then another.

We can get shot/ reverse-shot effects via mirrors.

A pan can also approximate a point-of-view shot, as when Tabitha sees Riggan at the other end of the bar.

Throughout, the ensemble staging motivates shifts that would normally be covered by cuts. Mike and Riggan are seen from behind the bar, but when customers spot Riggan and ask Mike to take a picture, the camera sidles around the bar.

As Mike and Riggan turn back to the bar we are effectively 180-degrees opposite to the first setup.

With cutting, a similar shift would have been motivated by changing the axis of action through shifts in staging.

Long-take shooting can’t mimic editing perfectly. An unbroken shot doesn’t yield the instantaneous change of angle supplied by a cut. But the scene can’t be allowed to go dead while the camera operator shifts to a new spot. So the interval between one sustained angle and another has to be filled up by dialogue and physical action. One way to motivate the change of camera position is through the actors’ changing positions. In the bar scene, the fan’s photo op motivates the camera move.

Alternatively, the actor’s gestures can provide some wedged-in bits. When Riggan and his wife have an intimate talk at his dressing table, he executes some business with a beer bottle that justifies shifting the angle to favor him.

Once we’re on him, he turns serious and the dialogue and facial expression motivate a push-in.

In normal shooting and cutting, the technique is fitted to the unfolding action. With a commitment to the long take, the director must fit the action to the technique. This is why, I think, González Iñárritu and his DP Emmanuel Lubezki spent months blocking the action on a sound stage and hiring stand-ins to move around the sets they’d built. Long before the actors came on the set, the filmmakers had mapped out many wedged-in bits of action they’d execute.

Giving up cutting forces other storytelling decisions. A narrative film typically distributes knowledge among its characters, and so the long-take camera must carve a path through the story world that either restricts or expands what we know. The mobile long take sticking with one character tends to restrict our knowledge. The long take that shifts among characters gives us a wider range of information. And whenever one character leaves another, there’s a forced choice: Which one does the narration follow? This is a choice in any storytelling medium, but in the long-take film the options are narrower: the issue is which one the camera will follow.

Birdman stays mostly with Riggan, but in the Complicating Action and Development sections, the narration needs to give us information on the doings of Mike, Lesley, and Sam. So, in another act of fitting and filling, the choreography must make those characters adjacent to some other action. The mazelike playing space of the film, in the bowels of the theatre, facilitates these comings and goings, so that we can drop one character and pick up another. When Lesley and Laura kiss, Mike interrupts them and Lesley hurls a hair dryer at him. He ducks out.

We could stay with Lesley and Laura, or follow Mike. We follow Mike so that we can shift to the new scene, with him visiting Riggan to complain about the pistol and then joining Sam on the roof. Nothing more of consequence will happen between Lesley and Laura; following Mike will lead us to the next story bit. The camera sees all that matters.

The long take’s muffled mimicry of orthodox editing pays some dividends. Arcs and short pans work when characters are close together, but if an encounter is played out in medium shot and one character pulls away, the camera is forced to pick a target. Whom will it follow? This effort becomes quite expressive when Mike is punching up Riggan’s table scene. Just as Mike takes over the rewriting of the lines, he hijacks the camera.

Things start with the usual circling shot.

As Mike’s pitch builds, he breaks from the neutral two-shot and circles Riggan. The camera favors him as he walks off, returns to the table and exhorts Riggan to turn up the tension. (“Fuck me!”)

Now that the two are in proximity, we can see Riggan, infected by Mike’s energy, deliver a more spirited line reading.

The scene ends with a segue to the next passage of walk-and-talk, as Sam comes onto the stage in depth.

In such scenes, the obstinate commitment to the long take itself motivates a dramatic effect. Later, Sam’s tirade about Riggan’s irrelevance gains force because the camera swings to her and stays fastened there.

In a cutting-based scene, there would have been the temptation to show Riggan’s reaction while Sam is unloading on him. True, we could get the same delayed revelation of his response by letting her tirade play out before cutting to him. But given our tacit adherence to the long take, and given the initial framing, we can’t see both of them. The refusal of editing itself justifies holding on her and suppressing his response. In the same way, showing her somewhat chastened pause and then following her walking past him motivates finally revealing his reaction.

A bonus: This scene’s concealment of the reverse angle—what is Sam seeing?—anticipates the film’s final image.

What about the long take’s effect on time? The plot’s tension relies upon the pressure of time. A great many actions are jammed into a short, continuous span. This is a common effect in films built around both a deadline and a confined space. Birdman‘s long take, with its rapid tracking movements and hurly-burly entrances and exits, enhances the pressure. But we need to note how much this result relies on another sort of “hidden editing.”

We often hear that the long take ties us to “real time.” And clock duration, with one minute onscreen equaling one in the story, is indeed a convenient, normative default. Yet suitably cued, a long take can halt duration in the present to give us flashbacks, as we’ve seen at least since Caravan (1934). Films by Angelopoulos, Jancsó, and others have shown that the long take can compress or expand story duration, and even replay events. The remarkable Iranian single-shot feature Fish and Cat of 2013 is full of ribbon-candy time wrinkles.

Once more, Birdman plays it straight. Like a normal movie, it uses sound bridges and night-to-day transitions to skip over stretches of story time. The film is a clear-cut example of the difference between story time (the years of Riggan’s career and the others’ lives), plot time (six days), and screen time (about 110 minutes). The central long take creates ellipses akin to traditional scenic links, and it does so in ways that are easy to grasp as we’re watching.

Intention: The expected virtues of ignorance

The crucial creative decision behind the film was the choice to shoot the extended take. González Iñárritu asserts that he didn’t model the technique on Rope but rather on the long takes of Max Ophuls. He also acknowledges that he was enraptured by Aleksandr Sokurov’s Russian Ark, a feature film that was indeed shot in one long take (thanks to video, but without CGI blending).

The status of the long take has changed across the history of film. In the first twenty years or so, it was more or less taken for granted as the most basic way to shoot a scene. Longer takes became rarer in most national cinemas during the 1920s, with editing becoming the preferred technique for building up action. Even complicated camera movements were consigned to comparatively brief shots.

The long take in today’s sense emerges most vividly in the early sound period, when directors began to use it creatively. During the 1930s, some long takes would be static or relatively so, in films like John Stahl’s Magnificent Obsession (1936) or musicals, especially those featuring Fred Astaire. Other long takes would make extensive use of camera movement. A great many early talkies begin with a fancy traveling shot before moving to more orthdox, editing-driven scenes. And the musicals of Busby Berkeley flaunted outrageous crane shots. In Japan, the USSR, France, Germany, and many countries, the sound cinema brought a renaissance of long takes, propelled by camera movement.

For the most part, this technical choice was felt to serve the story. You sustained the shot because the rhythm of performance benefited, or because you wanted to explore a space through a camera movement. In Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932), the tracking shots are designed to create uncertainties about where characters are when they go offscreen.

Behind the scenes, though, the filmmakers felt a certain pride in making a solid tracking or crane shot. A lengthy camera movement was a challenge because the cameras were big and bulky, they had to roll smoothly on tracks or other supports, lighting had to be controlled carefully, and equipment noise might be picked up.

Despite the difficulties, in the 1940s, some American directors seemed to have welcomed longer takes. The new interest probably owed something to new technology, such as the crab dolly’s ability to edge the camera through narrow spaces and turn in many directions. With complex camera movements easier, the takes could become longer. At a time when most films averaged eight to ten seconds per shot,Otto Preminger could make Daisy Kenyon (17 seconds), Centennial Summer (18 seconds), Laura (average 21 seconds), and Fallen Angel (33 seconds). There were as well Billy Wilder with Double Indemnity (14 seconds) and A Foreign Affair (16 seconds), Anthony Mann with Strange Impersonation (17 seconds) , and John Farrow with The Big Clock (20 seconds). This isn’t to mention the big long-take films of the period from The Lady in the Lake to Rope and Under Capricorn. The opening of Ride the Pink Horse contains a remarkable long-take tracking shot, and one shot in Welles’ Macbeth consumes a full camera reel.

It seems that for some directors sustaining the take was itself the main concern. The more complex the locale—a crowded room, a busy street, an overgrown landscape—the more that the sustained camera movement would be considered, at least by those in the know, as a difficult technical accomplishment.

The result was virtuosity, but with an alibi. Long takes are flashy. But…they can save money. (All those script pages covered fast, no need for editing.) They can be justified as realism. (The action can build over “real time.” Besides, don’t we see reality in a “continuous shot,” not cuts?) They can be motivated as subjective. (By staying with a character over a stretch of time, we become identified with him or her.) Regardless of these reasons, or excuses, there’s an undeniable bragadoccio associated with the protracted camera movement. Your peers in the industry will recognize what you’ve done, and cinephiles will applaud your bravado.

The Movie Brats seized on the virtuoso camera movement and long take as a mark of prowess. A new competition sprang up between Scorsese and DePalma, encompassing Raging Bull, Bonfire at the Vanities, Goodfellas, and Snake Eyes. Even a straight-to-video heist movie like Running Time (1997), choosing to hide its cuts in the Rope manner, has a bit of playground swagger. (Bruce Campbell is in it too.) No wonder that Christine Vachon remarks that shooting a whole scene in one is a “macho” choice.

It’s in this context that we can appraise González Iñárritu’s declared intentions. He was clearly drawn to the virtuosic side of the very long take, and his DP Emmanuel Lubezki had made the complex camera movement his signature with Children of Men and Gravity. After Snake Eyes showed that CGI could stitch together several long takes into a seamless whole, many directors saw that digital filmmaking could extend the shot beyond anything in analog cinematography. A new level of virtuosity was called for, not only the logistics of choreography but the skills of hiding the cuts. Do it right, you might even get tossed an Oscar or two.

The filmmakers justify Birdman‘s technique on familiar grounds. There’s realism:

We are trapped in continuous time. It’s only going in one direction. . . .This continuous shot [yields] an experience closer to what our real lives are like. (González Iñárritu)

There’s subjectivity.

I thought [the continuous take] would serve the dramatic tension and put the audience in this guy’s shoes in a radical way. (Lubezki)

To really not only understand and observe, but to feel, we have to be inside him. [The one shot] was the only way to do that. (González Iñárritu)

Is it showoffish? No, it serves the story.

All the choices we made were serving the purpose and dramatic tension of the characters, not about “Look how impressive we can be.” All the shots were meant to serve the narrative of the film. (González Iñárritu)

But there’s still virtuosity—art conceived as a triumph over self-imposed obstacles.

It was risky! Every scene—good or bad—I had to leave in. It was an endless strand of spaghetti that could choke me! Every note had to be perfect. (González Iñárritu)

I’ve never cared much for González Iñárritu’s films; they always seem too close to their influences. (My remarks on Babel are here.) Still, Birdman seems to me a fascinating example of how traditions can be revisited, or at least repackaged. I can also appreciate the skill with which the whole affair has been brought off. But I also wish that critics and mainstream filmmakers would be more accurate and comprehensive when talking about film form and style. Birdman isn’t a single-shot movie, and to insist on that point isn’t just pedantry. Part of the critic’s job is to look at what’s there, and a full account of the movie (which mine isn’t) would need to reckon in the other shots the film presents.

Critics should acknowledge that the long take has other expressive possibilities, some of them impossible to reduce to the patterns of continuity editing. To go back to Hou Hsiao-hsien, Flowers of Shanghai consists of thirty-five shots, nearly all made with a gently shifting camera. But Hou’s mobile long takes retain the intricacy of his static shots in earlier films. The camera may circle the action, but at each moment it’s not only following one character’s movement but drawing into view other movements, greater and lesser, nearer and farther off–the whole thing building up gestures and dialogue and facial reactions, as if by brush strokes, into a rich sense of characters coexisting in a story world and a social system. The result is a gradation of emphasis, to use Charles Barr’s neat phrase, that enriches our sense of the drama.

And sometimes the camera will not see all. Hou accepts the limits of the long take by making some action visible, some action partly visible, and some action unseen, even within the frame. Characters and props slide in to block the main action, sometimes shifting “against the grain” of the camera’s movement. The film’s visual flow doesn’t replicate the schemas of traditional scene analysis; often we must strain to see a gesture or reaction.

Hou’s isn’t the only way to use long takes, but it’s one that deserves more attention. Granted, he and other explorers in this vein will never win an Oscar. But our critics, too often dutifully repeating PR talking points, should signal that the enjoyable virtuosity of Birdman is only one way to employ the rich resources of cinema.

I’ll save for another time a reply to Riggan’s question to Tabitha: “What has to happen in a person’s life for them to become a critic anyway?”

My background information on Birdman‘s technique comes mostly from Jean Oppenheimer’s article, “Backstage Drama,” American Cinematographer 95, 12 (December 2014), 54-67. So does the quote from Lubezki above. A shooting script for the film is here. Information about the concealed digital cuts is in Bill Desowitz’s Indiewire piece.

Kristin’s model of four-part plot structure is discussed in several entries and in my essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture” and the book chapter “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.”

The idea that a camera movement can recapitulate the pattern of analytical editing was floated by André Bazin and developed in detail by John Belton, “Under Capricorn: Montage Entranced by Mise-en-scène,” in his Cinema Stylists (Scarecrow, 1983), 39-58.

For more on the long take, see our entry “Stretching the shot.” The Christine Vachon quotation is linked there, as is De Palma’s sense of competing with Scorsese. The first essay in my Poetics of Cinema discusses trends in long-take shooting and camera movement in the 1940s. See as well Herb A. Lightman, “The Fluid Camera,” American Cinematographer 27, 3 (March 1946), 82, 102-103, and “‘Fluid’ Camera Gives Dramatic Emphasis to Cinematography,” American Cinematographer 34, 2 (February 1953), 63, 76-77. On Dreyer’s camera movements in Vampyr, see my book The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. I discuss Angelopoulos, Hou, and long-take staging generally in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. On this site, I discuss Hou’s staging practices here and here. And for discussions of intensified continuity style, see The Way Hollywood Tells It.

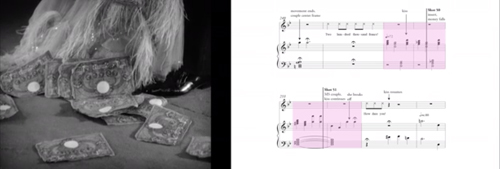

Two frames from Flowers of Shanghai (1998) are below, showing the camera’s slight movement around the central lantern and Pearl’s face, as well as the shift in the young man’s posture as he waits for an answer to his question. He’s in the process of clearing a bit of space for us to glimpse the older man, Hong, who’s sitting between him and Pearl.

P.S. 24 Feb 2015: Thanks to Paul Mollica for a name correction!

The sirens’ song for Oscar

The Lego Movie.

Another guest blog this week, this time from Jeff Smith, our colleague in the department here at UW–Madison. Jeff is one of America’s experts on movie music and sound technology. He contributed an entry on Atmos last year. He has written many articles on film sound, along with two books: The Sounds of Commerce and Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. He’s also our collaborator on the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction.

‘Tis the season for Oscar buzz, and the media glut of award prognostications is already upon us. Most of the attention will go to the above-the-line talent who’ve received nominations (actors, directors, and screenwriters). The craft categories tend to get much less scrutiny, but the work of cinematographers, editors, and composers plays an equally important role in making their films award-worthy.

Today I offer some observations about this year’s nominees in the music categories: Best Original Score and Best Original Song. By using the nominees as examples, I hope to illuminate some of the ways that music continues to contribute to cinema’s narrative functions and its emotional impact on viewers. I’ll also offer my predictions for who will win at the end of each section.

Best Original Score

Even before this year’s nominees were announced, one of 2014’s most distinctive and innovative film scores was declared ineligible by the Academy. Antonio Sanchez’s driving percussion score for Birdman was disqualified under Rule 15, which states that scores “diluted by the use of tracked themes or other pre-existing music, diminished in impact by the predominant use of songs, or assembled from the music of more than one composer shall not be eligible.” Apparently, in the view of the Academy’s music branch, Birdman’s use of substantial excerpts of concert music by Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Ravel, and John Adams weakened the impact of Sanchez’s score. That explanation, though, probably doesn’t pass the eyeball (or eardrum) test of anyone who has seen Alejandro González Iñárritu’s film. Sanchez’s drum work adds verve and energy to several of the director’s elaborately choreographed (and seamlessly stitched together) long takes.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s electronic score for Gone Girl was also a notable snub, especially since their bold, pathfinding music for The Social Network took home the top prize just four years ago. The fact that both of these scores failed to secure nominations may be a sign that the Academy’s music branch is returning to the verities of good old-fashioned melody and harmony as the basic tools in the composer’s kit.

That being said, the absence of Sanchez, Reznor, and Ross from the list of nominees doesn’t mean that the remaining scores are dull or unadventurous. Quite the contrary. Several of them push film composition in new and exciting directions. Their scores fulfill traditional functions but employ innovative scoring techniques and orchestrations.

Old sounds, new sounds

Take, for instance, Gary Yershon’s score for Mike Leigh’s biopic, Mr. Turner. Bypassing the conventions of orchestral writing for film, Yershon composed for a chamber-sized ensemble. Some cues combine a saxophone quartet with a string quintet, a musical choice that seems deliberately anachronistic. (As Yerson himself says in the soundtrack’s liner notes, Adolph Saxe’s invention wasn’t even patented until 1846, just a few years before Turner’s death.) Other cues add flute, clarinet, harp, tuba, or timpani to the mix. But these embellishments simply add color to the basic sound of Yershon’s twin string and saxophone ensembles.

Yershon says he was attracted to the saxophone due to its ability to glissando – that is, bend pitch from one note to another. Yershon certainly exploits this element of the instrument’s sound by building his melodies from long sustained notes that slowly take on serpentine shapes. Saxophone glissandi have an almost iconic function in the idioms of jazz and pop music . (Think of the opening phrase of Wham’s “Careless Whisper.”) In this case, though, the technique gives Yershon’s score a minimalist, modernist edge.

Yershon’s inclusion of a saxophone quartet departs from two norms: the period music of Turner’s time and the symphonic orchestrations that have characterized biopics for decades. The saxophone was never a major component of the Hollywood sound crafted during the studio era. Composers like Max Steiner and Victor Young occasionally included saxophones in their arrangements of music played onscreen by dance bands, but for the most part, their wind arrangements were for some combination of flutes, oboe, English horn, clarinets, and bassoons.

Is Yershon’s score inappropriate on historical grounds? I don’t think so. By modernizing the sound of Leigh’s period biopic, Yershon’s score adds a contemporary resonance, perhaps encouraging viewers to see parallels between Turner’s painting and the work of modern-day artists. Indeed, as Guy Lodge noted in his Hitfix review of the film, “It’s tempting, even, to view the film as biopic-as-self-portrait, revealing shades of one life through another. Leigh has a reputation for prickliness and resistance to self-explication; perhaps it’s not surprising that he’s long been fascinated by Turner’s allegedly gruff, taciturn genius.”

Yershon’s use of contemporary instruments may not in itself suggest those historical parallels. Indeed, most viewers probably have no idea when the saxophone was invented. But it certainly invites us to think about Leigh and Yershon’s reasons for opting for such a modern sound. And with its smaller instrumental forces, Yershon’s score resists some of the sweeping emotionalism that is found in other examples of the genre.

Zimmer pulls out all the stops

Hans Zimmer’s nomination for Interstellar is the tenth of his long and distinguished career. With all apologies to John Williams, Zimmer is arguably Hollywood’s leading film composer and his work is emblematic of a larger industry turn toward emphasizing musical tone and texture rather than big memorable themes. Zimmer’s score for Interstellar is no exception to this rule. In this case, though, much of the tone and texture is provided by the four-manual Harrison & Harrison pipe organ found in London’s Temple Church.

Director Christopher Nolan says that he liked the sound of the church organ as something that added an element of religiosity to Interstellar. But the organ contributes other things as well. For one thing, the organ’s booming bass register adds mass and heft not only to the music, but also to the astronomical bodies shown onscreen. The sheer size of these lower frequencies enhances the sense of scale in Nolan’s imagery. Thanks to the organ’s huge pitch range, the instrument’s upper register provides the quieter, swirling arpeggios needed to suggest the story’s filial bonds between father and daughter. At the same time, the instrument’s big, fat bottom end adds the musical bombast needed to convey the film’s epic visions of distant planets, wormholes, and alternate dimensions.

More important, despite the church organ’s strong association with sacred and liturgical music, Zimmer’s score never sounds like a Bach toccata. Rather, due to its repetitive, but intricate arpeggiations and simple, but affecting harmonic structures, Interstellar’s music has the kind of trippy, drone-ish, psychedelic feel that suggests both Terry Riley and Iron Butterfly. Zimmer’s score does not contain anything that is an obvious quote from the music of Stanley Kubrick’s “thinking man’s” sci-fi classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Yet, in its own way, Zimmer’s music recalls the period where such films were being produced, indeed the very kind of film that Nolan self-consciously tried to recreate.

In developing the score for Interstellar, Nolan and Zimmer also departed from the norms for director-composer collaborations. Most composers begin their work at a fairly late stage in the filmmaking process. In some cases, they may work from a completed script. In most cases, though, a composer starts with a rough cut of the film, making his or her contribution felt only during post-production.

In contrast, Nolan acknowledged that he has gradually been bringing Zimmer into his production at earlier and earlier stages. Nolan dislikes the practice of temp tracking, a technique that involves slugging in preexisting music that temporarily serves as a guide to the production team during the editing process. Says Nolan, “To me music has to be a fundamental ingredient, not a condiment to be sprinkled onto the finished meal.”

For Interstellar, Nolan asked to meet with Zimmer well before production began. As Nolan recounts in the liner notes to the soundtrack, he gave the composer an envelope containing a one-page summary of the fable that sat at the heart of the story. The description did not contain any details of the film’s genre or plot. Rather the summary simply laid out the narrative’s emotional core. Zimmer then took the summary and retired to his studio to start composing. Several hours later, Zimmer brought back a CD that contained about three or four minutes of music. Nolan listened to the new piece: a simple piano melody that nonetheless captured the feeling of what the director says he was “already struggling with on the page.”

When Nolan began shooting, he frequently listened to Zimmer’s simple piano piece, which functioned as a kind of “emotional anchor” for the film. Eventually, Zimmer returned to the studio and created the huge musical canvas that captures Interstellar’s heady exploration of space and time. Underneath it all, though, is the humble melody Zimmer wrote prior to production, the modest edifice upon which the rest of the score is built.

More songs about buildings and food service

Like Zimmer, Alexandre Desplat has several previous nominations to his credit, including those for the scores of Best Picture winners The King’s Speech and Argo. Unlike Zimmer, though, Desplat has yet to win. Among Hollywood’s current A-list composers, Desplat has shown extraordinary versatility. He’s at home writing for foreign art films, American indies, animation, and studio genre pictures. Desplat’s score for Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel is the third he has done for the director, following earlier collaborations on The Fantastic Mr. Fox and Moonrise Kingdom.

Here again, Desplat’s score for The Grand Budapest Hotel departs from established norms of Hollywood orchestration. Although he uses a slightly smaller version of the wind and brass sections usually found in older Hollywood film scores, he avoids the normal violins, violas and cellos. Instead he opts for a string section comprised of balalaikas, cimbaloms, zithers, mandolin, and acoustic guitar. This choice is intended to reflect the vaguely Mitteleuropean setting of the film. Just as the story is loosely inspired by the writings of Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig, the music reflects the social and geographical milieu of Zweig and his characters during the 1920s and 1930s. Eastern European and Russian folk melodies inspired much of Desplat’s. This combination of instrumentation and idiom creates a harmonic and timbral palette that proves to be enormously flexible in the composer’s hands, enabling him to add classical, modern, and jazz touches wherever they are needed.

Although Desplat employs unusual orchestration in The Grand Budapest Hotel, his score is fairly traditional in other ways. There are leitmotifs for several of the main characters, such as M. Gustave, Zero, Madame D., and Ludwig. An eight-measure theme is also linked to situations of adventure or danger. These themes and motifs tighten up the film’s structure. Such cues for patterning are particularly important when one considers The Grand Budapest Hotel’s “Chinese box” or “Russian doll” narrative construction, which nests stories inside stories.

Desplat’s score also captures the film’s dark yet whimsical tone. In interviews, the composer acknowledges that Bernard Herrmann and Carl Stalling were important influences on his work. At first blush, Herrmann, who composed several iconic scores for Alfred Hitchcock, and Stalling, who wrote crazy, almost manic music for Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons, would seem to occupy opposite corners of the universe. It’s to Desplat’s credit, though, that he is able to blend these diverse influences in a manner that is perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s imaginary “snow-globe” world. Indeed, the cue for the scene where Gustave is hanging from a cliff features harmony that would not be out place in Herrmann’s score for North by Northwest, an obvious inspiration.

But the mood is much lighter and airier in Anderson’s cliffhanger, partly because of the tenor established by Desplat’s music.

Scoring the Beautiful Minds of Cambridge

Ironically, Desplat’s chief competition may come from himself. Besides The Grand Budapest Hotel, Desplat also received a nomination for the fact-based espionage thriller, The Imitation Game. It was the fourth time in the last fifteen years that a single composer received two Oscar nominations for Best Original Score. And like the other nominees discussed here, Desplat developed an unusual compositional technique for the film, allowing for an element of randomness to determine his score’s final musical shape.

Whereas Sanchez deviated from compositional norms by improvising beats for Birdman, Desplat’s score for The Imitation Game pushes the envelope by featuring three computerized pianos, which sometimes play random patterns of preprogrammed music. According to the composer, the pianos’ fast, complex combinations not only underscore the urgency of the Bletchley Park team’s search for a solution to the Nazis’ Enigma code, but they also function as an musical correlative of cryptanalyst Alan Turing’s thought processes. As director Morton Tyldum put it, he wanted the music to seem subjective, as though it was conveying the mental operations inside the head of an awkward, but brilliant mathematician.

Desplat’s use of rapid scales and arpeggios to represent Turing’s genius actually recalls Philip Glass’ score for Errol Morris’s documentary about Cambridge physicist Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time. To be fair, Glass’ compositional style has employed these kinds of musical textures in many other types of cinematic contexts. Glass’s work not only appears in other Morris films, but also in biopics about Japanese writer Yukio Mishima and the Dalai Lama, and even in horror films and dramas, such as Candyman and The Hours. Given the constancy of his compositional proclivities, it is perhaps easy to make too much of Glass’s ability to depict the depth and brilliance of Hawking’s intellect. Yet there is little question that Glass’s music adds both a sense of mystery and majesty to Morris’s imagery, which itself explores such imponderables as the nature of time and the origins of the universe.

Because of this precedent, it is perhaps doubly striking that composer Johann Johannson took such a different tack in his music for the Hawking biopic, The Theory of Everything. With long sustained string lines and simple piano melodies, Johannson aims for a soft lyricism that is intended to add both pathos and subdued passion to the film’s depiction of Hawking’s relationship with his wife Jane. Since the film is based on Jane’s account of their marriage, it is probably not surprising that Johannson’s score plays her point of view even more than it does that of its putative subject. As the composer explains, the “heart of the film is the love story: Stephen and Jane, Jane and Jonathan. That’s really what the music needed to capture.” Thanks to Johannson’s use of harpsichord, celeste, harp, and guitar, the tone colors of the music remain light, making his score for The Theory of Everything a modern counterpart to the work of the Georges Delerue.

Prediction

All five nominees are quite worthy of the award for Best Original Score. But, if I had the opportunity vote, I would probably cast it for The Grand Budapest Hotel. Not only is Desplat’s score perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s distinctive style, but it would be nice to see the composer recognized for the overall quality of his oeuvre. Desplat’s fans, though, probably split their votes between The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Imitation Game, thereby increasing the chances that he’ll once again go home empty-handed.

In underlining The Theory of Everything’s romance plotline, Johansson’s score is perhaps the most traditional among the five nominees. I don’t believe, though, that its adherence to longstanding film score conventions will hurt it on Oscar night. Johansson’s sweet lyricism already carried the day at the Golden Globes, an award that has correctly predicted the eventual Oscar winner four out of the last five years. Although there could be an upset in this category, I expect we’ll see Johannson triumphantly hoist the little gold man over his head come Sunday night.

Best Original Song

If recent award ceremonies are any indication, this is a category that has fallen a bit on hard times. At least this year, there are five legitimate nominees. Last year one of the nominees was disqualified, and in 2012 and 2011, the category fielded only two and four nominees respectively.

One potential reason for the paucity of original songs may be the previously mentioned turn toward tone and texture in contemporary scoring practice. In the old days, many of the best-remembered and best-loved songs from the movies were crafted from themes specifically composed for the score. This was the case with tunes like Alfred Newman and Frank Loesser’s “Moon of Manakoora” from The Hurricane, Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s “Days of Wine and Roses,” or even James Horner and Will Jennings’s “My Heart Will Go On” from Titanic. Since current film composers are turning away from big themes, it seems there is less opportunity to adapt a musical motif into something that works as a theme song. (Of course, there are occasional exceptions. In 2013, Adele and Paul Epworth took home the Oscar for Skyfall, updating the established formula for making Bond theme songs.)

This year’s nominees also lack anything resembling last year’s heavyweight battle between Frozen’s “Let It Go” and Despicable Me 2’s “Happy.” All of the nominees seem quite worthy. None of them, though, has created the kind of cultural ubiquity enjoyed by Idina Menzel’s and Pharrell Williams’s chart-topping singles.

Two of the nominees have the misfortune of appearing in little seen films: Beyond the Lights and Glen Campbell: I’m Not Me. Diane Warren is one of the industry’s top songwriters and her “Grateful” is featured in the former of the two films. Warren also is a seven-time Oscar nominee, and although I believe her time at the podium will eventually come, it seems unlikely this year. Glen Campbell and Julian Raymond’s “I’m Not Gonna Miss You” is a moving ballad, made all the more poignant due to the singer’s ongoing struggles with Alzheimer’s disease. Campbell’s battle, which is the subject of James Keach’s documentary about the singer’s farewell tour, makes the song a counterpart to other epitaph numbers, such as Johnny Cash’s cover of “Hurt” or Warren Zevon’s “Keep Me in Your Heart.”

The third nominee is “Lost Stars” from Begin Again, director John Carney’s belated follow-up to his earlier indie sleeper, Once. “Lost Stars” was written by two members of the nineties band the New Radicals: Gregg Alexander and Danielle Brisebois. The latter has come a long way since her days as a seventies child star appearing in Broadway’s Annie and television’s All in the Family. Starting in the 1990s, Brisebois remade herself as a successful songwriter and producer, penning tracks for Donna Summer, Natasha Bedingfield, Kelly Clarkson, and a host of other top female performers.

“Lost Stars” is heard several times in Begin Again. The first time Gretta (Keira Knightley) performs it in a spare singer-songwriter arrangement featuring acoustic guitar, piano, and strings. It underscores a flashback of Gretta’s arrival in New York with her skeezy rock-star boyfriend Dave (Maroon 5’s Adam Levine). Later, we hear it as a track on Dave’s CD. Here he gives it an up-tempo stadium-pop sheen. Near the film’s end Dave again performs “Lost Stars,” this time as an arena-rock power ballad.

It is unusual to hear an Oscar-nominated song played in such wildly different styles, and even more unusual for one of those versions to be served up in a manner intended to seem excessive and distasteful. Tellingly, the end credits list Dave’s rendering of the song on CD as “Lost Stars (Overproduced Version).” The contrast between them, though, provides important character motivation for the film’s resolution. Dave’s indifference to Gretta’s creative vision of the song shows that he is ill suited to be her romantic partner. It also reveals producer Dan as a much more kindred spirit for Gretta’s professional ambitions. She gets to keep her coffeehouse, folkie purity even as her coffers are filled by the filthy lucre earned from sales of the soulless version featured on Dave’s major-label CD.

Interestingly, on Oscar night, Adam Levine will sing “Lost Stars” as part of the broadcast. If the producers wanted to stay true to the spirit of “Begin Again,” they might have opted for Keira Knightley to perform the song. Yet the fact that Levine was the first performer announced suggests that his star power was simply too much of a draw. Despite the film’s critical view of Dave’s talent, sales of Levine’s version of the song appear to have outpaced Knightley’s. Begin Again may be cynical about the music’s industry’s overinvestment in mainstream tastes, but Levine’s “overproduced” version of “Lost Stars” has done a great deal to give the film much-needed media exposure.

The fourth nominee, The LEGO Movie’s “Everything is Awesome!!!”, arguably displays an even more mind-bending degree of complexity in its relation to the popular music marketplace. The song appears quite early on in the film introducing us to a “utopian” animated world where citizens happily play their part in serving Lord Business. As my colleague Jeremy Morris pointed out in a campus symposium on song “hooks,” “Everything is Awesome!!!” is a tongue-in-cheek anthem to teamwork, conformity, and the dominant ideologies regarding labor and consumerism. Think of it as Adorno and Horkheimer for the toddler set, or better yet, as part of the Frankfurt Pre-School.

As an element of internal critique within The LEGO Movie, “Everything is Awesome!!!” is pretty effective. In a particularly naked example of Marx’s “false consciousness,” we see the characters’ submission to corporate control even as we recognize that all is not awesome in Lego Land.

If only the song weren’t so damned catchy. Like the film, the song appears to be crafted to appeal to both the kids who make up its target demographic and the parents stuck in the theater with them. The melody is deliberately simple with a pitch range and structure that any three year-old could sing. However, the song’s “four on the floor” rhythms and electro-flavored instrumentation also make it palatable to adults as well. The end result is an earworm that insinuated itself into my brain for days at a time.

Much of the song’s success derives from its ability to play it both ways. On the one hand, as a theme song for The LEGO Movie, “Everything is Awesome!!!” gently satirizes the unholy marriage between business and government that structures the Lego universe. On the other hand, though, the song appears in what is essentially a feature-length commercial for toys. Moreover, it is so hooky and memorable that it also helps promote The LEGO Movie in various ancillary markets. Still, if that sounds even more cynical than Begin Again’s depiction of corporate sellout, I can’t think of another song that would better fit what The LEGO Movie tries to accomplish.

The final nominee is “Glory” by John Legend and Common. The song is featured in Selma, Ava DuVernay’s biopic about Martin Luther King Jr. A soulful, gospel-inflected ballad, the song was written as a tribute to the members of the Civil Rights movement who worked tirelessly in their fight for equality, especially their efforts to help passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. It appears during an epilogue underscoring a montage that mixes fictional scenes with photographs and archival footage of the real-life Selma marches. The sequence also relates the fates of the various historical actors depicted in the film, reminding us of the sacrifices they made.

With its soaring chorus and rapped verses, “Glory” is decidedly contemporary fare. Yet it remains a worthy successor to the rhythm-and-blues classics heard in the film, such as Otis Redding’s “Ole Man Trouble” and The Impressions’s “Keep on Pushin’”.

Like the other four nominees, “Glory” displays the kind of multi-functionality that is the hallmark of great movie songs. Its style reminds viewers of the important role played by black churches in the early years of the Civil Rights movement. The song’s uplifting tone also provides a satisfying emotional climax to the film, providing a sense of triumph over the physical and political challenges faced by the film’s characters. Lastly, Common’s lyrical reference to the protests of Ferguson also reminds us that the struggles for civil rights continue.

The historical parallels between current events and protests portrayed in Selma have earned considerable commentary by pundits and journalists. And one doesn’t need to hear the song or even see the movie to understand the reasons why the phrase “Black lives matter” resonates across these different generations. Yet Legend and Common’s song makes perhaps the film’s most concrete and explicit connection between past and present. By linking the literal and metaphorical dimensions of Selma’s historical allegory, “Glory” achieves an associative richness that very few recent movie songs can match.

Prediction

Entertainment Weekly characterizes this as a two-horse race. The magazine suggests that “Everything is Awesome!!!” and “Glory” each give voters a chance to right a perceived wrong, honoring a film snubbed in some of the other categories.

As I indicated earlier, I find the pop panache of “Everything is Awesome!!!” undeniable. More important perhaps, the filmmakers adroitly weave the song into particular scenes in The LEGO Movie. Still, I don’t think that will be enough for “Everything is Awesome!!!” to take home the top prize. In underscoring Selma’s import and its timeliness, “Glory” does something that none of the other nominees does. By drawing together African-American musical styles, both past and present, “Glory” is imbued with a political and historical resonance that strives for higher ground. For that reason, I expect John Legend and Common will add Oscar to the other accolades they have received.

First, many thanks to Jeremy Morris, my colleague in the University of Wisconsin’s Communication Arts Department, whose thoughts on The LEGO Movie have unquestionably shaped my own. A shout-out also to Jon Burlingame, whose coverage of film music topics in Variety is second to none. Burlingame has surveyed the best Original Score nominees, and the Best Original Song nominees.

On Desplat, see Burlingame’s article “Alexandre Desplat’s Twin Takes on WWII: ‘The Imitation Game’ and ‘Unbroken.” Additionally, Matt Zoller Seitz’s companion volume to The Grand Budapest Hotel contains an interview with Desplat and an analysis of the score that reproduces excerpts from certain cues. More on Seitz’s book can be found in this promo film. The Grand Budapest Hotel’s entire soundtrack is on YouTube. Earlier entries on The Grand Budapest Hotel on this site are here and here.

For those interested in the development of Interstellar’s score, there’s a short video on J. Bryan Lowder’s blog containing interviews with both Christopher Nolan and Hans Zimmer. Lowder offers a thorough overview of Zimmer’s score here. John Legend offers comments on his song for Selma.

Begin Again.

Memory books, the movies, and aspiring vamps

Kristin here:

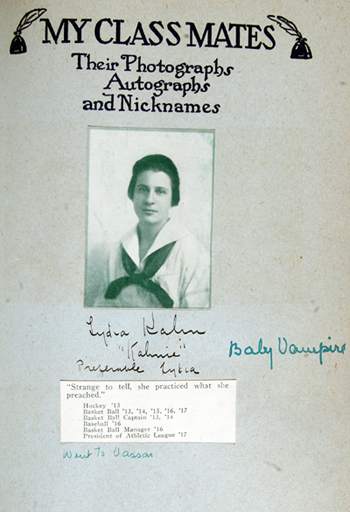

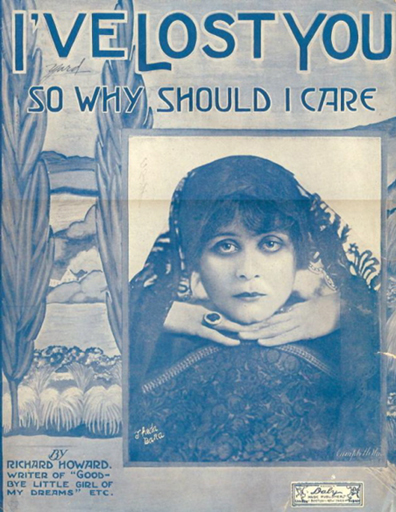

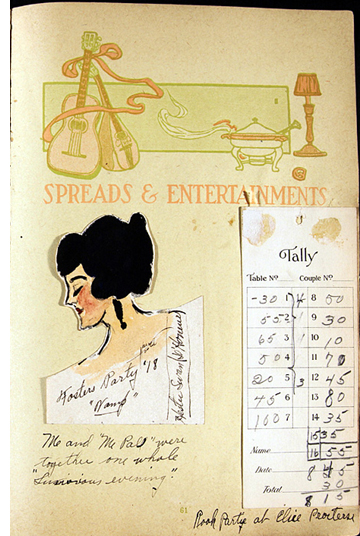

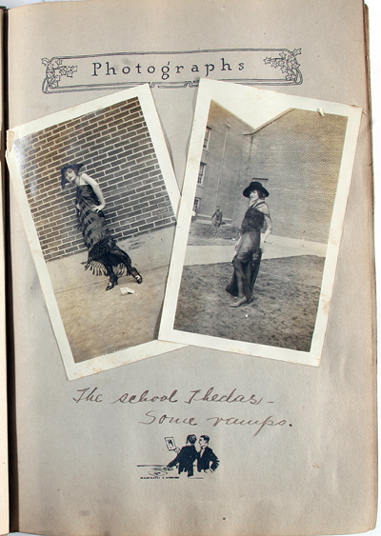

We are happy to have a guest entry from our long-time friend and colleague, Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, who recently retired from teaching film at the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. Back in the 1990s, when David and I were helping edit a series called “Wisconsin Studies in Film” (University of Wisconsin Press), Leslie contributed Reel Patriotism: The Movies and World War I. Now she is involved in a fascinating project on the same period, the 1910s. There is much focus these days on reception studies, which focuses on trying to gauge the reactions of audiences to movies. Reconstructing mental events is a difficult, near impossible task. Yet Leslie has found a way to glimpse the ways in which American girls and young ladies of decades ago consumed and thought about movies: by studying the scrapbooks they left behind. Here’s a sample of what she has discovered.

Fangirls of yesteryear

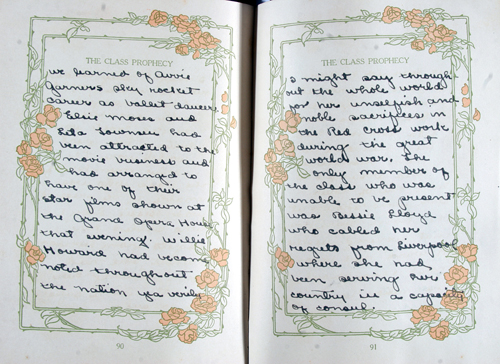

Kate Key received a scrapbook bound in red leather and entitled My Commencement as a gift from her oldest sister Ruth when she graduated from Lampasas High School, class of 1917.

She was eighteen, born and raised in this central Texas farming and ranching community of about 2,100. As far as I can tell, there were no dedicated film theatres in town. Instead, movies alternated with concerts, vaudeville and plays on the bill at the Witcher Opera House. So, I was surprised to read in her class prophecy (a humorous forecast of what the students would be doing in a fictive future) that Elsie Moses and Leta Townsen would return for their class’s reunion in 1928 as movie stars and graciously show their films at the Grand Opera House.

This caused me to wonder whether girls who lived in other parts of the United States also made jokes out of the movies? Might scrapbooks offer film historians like me, interested in the ways that films fit into the lives of everyday people, a new sort of evidence of exhibition and reception in the 1910s and 1920s? When girls mentioned movies in their scrapbooks, or pasted in ticket stubs and theater programs, did they whisper “open sesame” to a quotidian film culture? Was that culture different from and more pervasive than that practiced by fangirls (and boys) who avidly consumed Photoplay and wrote mash notes to their favorite actors? I began to search out scrapbooks, specifically high school and college memory books.

To date, I have collected upwards of 45 scrapbooks. The scrapbooks I have found and studied are mainly the products of white, middle class and upper middle class girls. I have an example or two at either end of the economic spectrum. Despite my best efforts, I have had no luck so far finding the memory books made by African-American teenagers, though I suspect these exist. (I would welcome any suggestions.) New immigrants to the country may not have been aware of this “tradition.”

Before I survey what I have learned from American girls about themselves and about movie-going, let me tell you a bit about scrapbooks.

Multi-purpose compendiums

They have a long history in the United States. Samuel L. Clemons, Mark Twain himself, was an avid scrapbook-maker, and he patented a model featuring self-adhesive pages in 1873. By 1880, how-to books like E.W. Gurley’s Scrapbooks and How to Make Them, Containing Full Instructions for Making a Complete and Systematic Set of Useful Books, guided novices with instructions for what to include and even recipes for the glue to stick objects in place.

Arranged by topic and indexed for efficient access, early scrapbooks consolidated recipes for food or household concoctions. They served as encyclopedias and also provided entertainment. Poetry and fiction were appropriate inclusions harking back to the days of commonplace books. The scrapbook became a means for autobiography and a method of keeping family history. Gurley promoted making scrapbooks both an individual and a collective endeavor. Neighborhoods might organize a scrap-book club, and families could draw on the help of relatives to fill the gaps in their chronicles by bringing their books to reunions. For example, in 1906, Marion Renfrew, a school girl in Boston, invited her friend Eva Alberta Mooar to a party celebrating the “debut” of the “offspring of her labor and patience Memory Book.” Eva saved that letter in her own scrapbook, and the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Radcliffe preserved Mooar’s book in its archive.

Marketing scrapbooks to girls

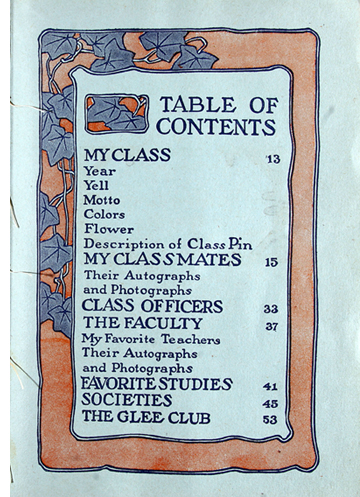

Girls were a devoted audience for advice about creating scrapbooks, and the activity became, increasingly, a gendered one. By 1905, scrapbooks were a commodity, mass produced, sold at stationery shops, and complemented by auxiliary  businesses which supported them. Companies manufactured specialty paper corners, some with elaborate designs for sticking photographs to the scrapbook page. One genre of scrapbook was the memory book designed mostly for girls and young women and given to them as presents on special occasions like graduation from high school or college.

businesses which supported them. Companies manufactured specialty paper corners, some with elaborate designs for sticking photographs to the scrapbook page. One genre of scrapbook was the memory book designed mostly for girls and young women and given to them as presents on special occasions like graduation from high school or college.

The Reilly & Britton Company offered eight different titles of school memory books for sale by 1917. The price of these gift books depended on their binding; “Fancy cloth, decorated with gold and two colors,” cost two dollars (about $40 today), but a leather cover with a velvety finish called ooze, added an extra dollar and twenty-five cents.

A blank page might have invited girls to fill in stuff of their choosing, but flowery Art Nouveau borders pushed the design toward a notion of conventional, appropriate girlhood. The filled spaces also conjured the metaphor that school was a garden, carefully tended, its flowers growing in tidy uniform beds. Memory books featured standard tables of contents that suggested what girls should preserve and how their mementos ought to be arranged. However helpfully intended, these headings also functioned to delimit what high school included and to prompt girls to tell a cheery, triumphal story in which “favorite” teachers, “best friends,” all sorts of parties, athletic endeavors, and the rituals of graduation would lead ineluctably to the happy reunion foretold by the class prophecy.

Still, what I have come to relish about girls who made scrapbooks is that they did not necessarily abide by the dictates of their books’ blueprints. They surely recognized the ideological requisites of girlhood structured onto memory book pages, but they may not have entirely subscribed to them. Often and idiosyncratically, girls changed and adapted their books.

Girls make scrapbooks to suit themselves

Elizabeth Walker travelled more than one hundred miles from Mineola, Texas to attend the College of Industrial Arts at Denton in 1918. She seemed to embrace the process of compiling My Memory Book. Hers was larger than most: 15” wide, 11” tall, and 2 ¼” thick. It appears that she received it when she matriculated and she filled in the pages as she progressed through her four years of teacher-training. After Elizabeth graduated in 1922, she became a teacher in El Paso. She continued to slide letters, documents including the Code of Ethics for Texas teachers and newspaper clippings, inside the back cover of her book during the 1930s. The most recent insertion was dated 15 July 1969. It was snipped from the school’s (now Texas  Women’s University) alumnae bulletin and brought her up-to-date on members of the class of ’22.

Women’s University) alumnae bulletin and brought her up-to-date on members of the class of ’22.

Still, at the beginning, the freshman Elizabeth had composed a bantering dialogue with her memory book’s table of contents. She treated it as a slightly irritating senior who was trying to tell her how to act. For instance, halfway down the list of things she was supposed to save were pressed flowers and leaves. “Don’t believe in ‘em,” retorted Betty.

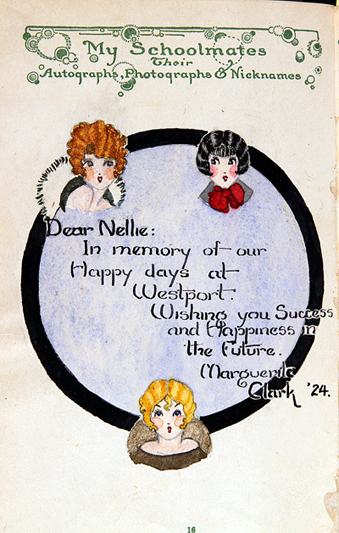

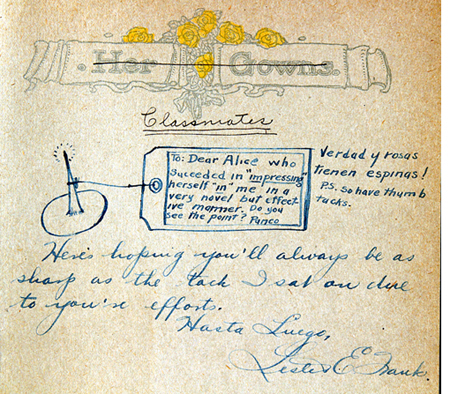

Alice Ebeling graduated in 1919 from South Bend High School in Indiana. She drew a line through the heading “Her Gowns,” replaced it with “Classmates,” and used the pages for autographs from her friends including Lester Frank (left). Apparently, he was on the receiving end of a prank she played in Spanish class.

Corinne Campau, Sophie B. Wright High School, New Orleans, class of 1919, crossed out “Favorite Studies” and pasted in a drawing of a rotund store clerk resembling the Campbell Soup kids drawn by Grace Drayton. Even better, the illustration covered up rude comments Corinne had written about a first-aid class and its annoying, irrelevant, teacher: “IT’S a joke. (‘Girls, I heard a case of a beautiful young woman—Oh, a sweet lovely young woman who fell on a brick + broke her hip.’)”

To me, there is irony, if not a nervous, dark humor in the decision of Fannie Klapman (Murray F. Tuley High School, Chicago, 1920) to glue a little cloth envelope embroidered with flowers on the page designated for “Card Parties.” The description she wrote underneath said, “New Year’s card from my brother at that time in France.” (He mustered out safely and went on to graduate from Crane Junior College in 1920.)

As well as manifesting a playful irreverence, the ways that girls altered memory books testified to a belief in their own agency. Scrapbooks were not private or secret like diaries. Girls took them to school where they solicited classmates’ autographs and good wishes; they showed them to friends who visited their homes. Although I expect many girls started to compile their memory books by following the order set out in tables of contents, when that rubric didn’t accommodate their stuff or their lives, they deliberately, messily, and with the knowledge that their actions would be seen, took matters into their own hands. They also began to make changes in the history of their lives at school almost as soon as they pasted their stuff in place. Memory books, like memory itself, were changeable, dynamic.

Movies and American girls

Since none of the books I have examined contain designated pages for films, how did American girls fit movie scraps into their memory books? When I consider my collection of artifacts, two broad patterns hold.

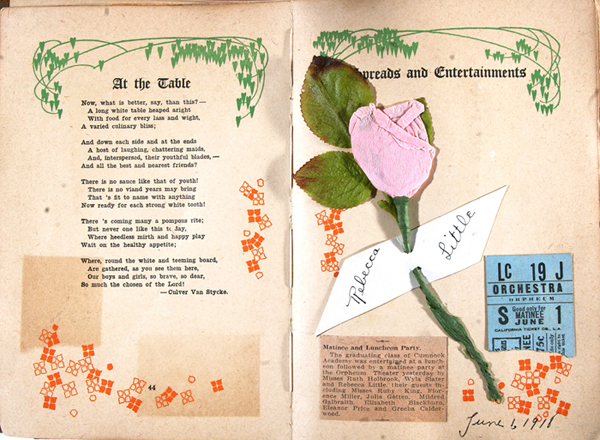

First, girls saved ephemera including ticket stubs, programs, occasionally newspaper advertisements that proved they actually saw films. (Above, Rebecca Little’s scrapbook from 1918.) I’ll call this category “Girls Go to the Movies.”

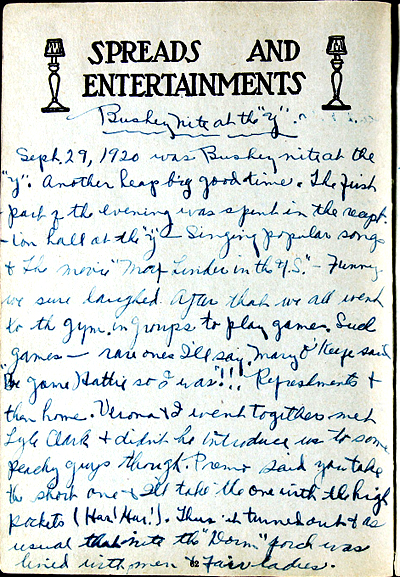

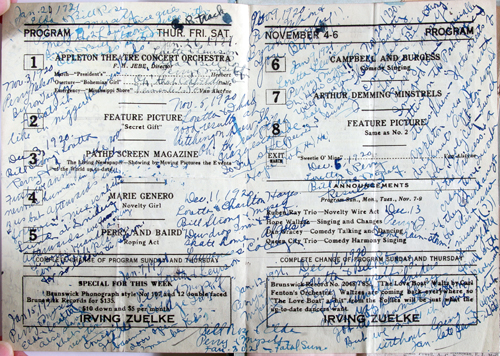

Second, and more intriguing, scrapbooks are crammed full of evidence that girls incorporated the movies–their actors, narrative conventions, and film titles—into a vernacular culture, national in its scope, spanning different religious affiliations. (Above, Hattie Stein’s School Friendship Book describes how she and her friends saw a Max Linder movie at the YMCA in Appleton, Wisconsin.) Let’s name this second motif, “Girls Make Fun with Movies.”

Girls go to the movies

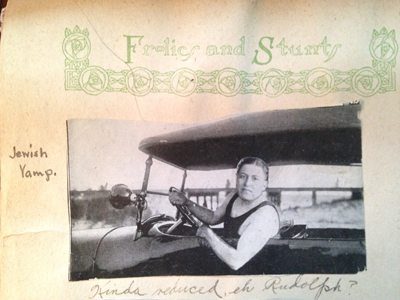

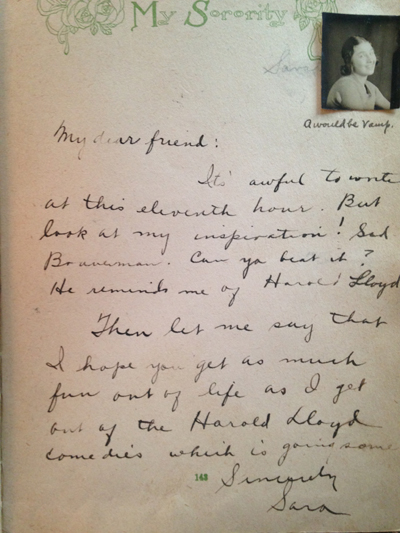

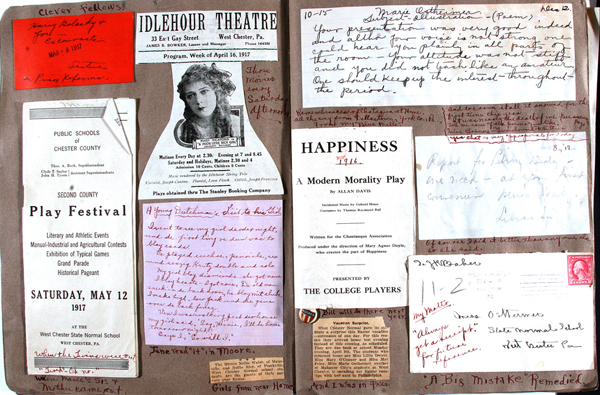

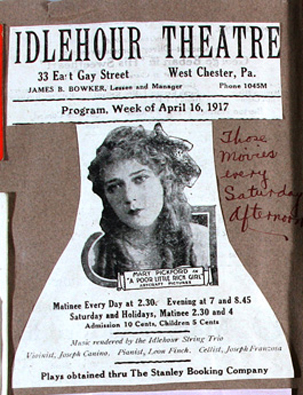

Scrapbooks show that movie-going was one activity among many that mattered to girls in the 1910s and 1920s. No one expressed this better than did Marie Ostheimer, who graduated from West Chester Normal School in southeastern Pennsylvania in 1917. The only mention of film in the thirty-six pages of her Normal Life is the Liberty Bell-shaped newspaper ad for The Poor Little Rich Girl at the Idlehour Theatre which she clipped out (see bottom image). Nevertheless, she captioned it “Those movies every Saturday afternoon.” Her annotated two-page spread surrounds Little Mary with play programs, an excellent evaluation she received for a class presentation, news cuttings about her own and her friends’ trips home, and a receipt that was evidence of some sort of kerfuffle over a doctor’s bill. It is a snapshot of learning, leisure, and life experiences among which going to the picture show was part of the routine of weekend fun.

home, and a receipt that was evidence of some sort of kerfuffle over a doctor’s bill. It is a snapshot of learning, leisure, and life experiences among which going to the picture show was part of the routine of weekend fun.

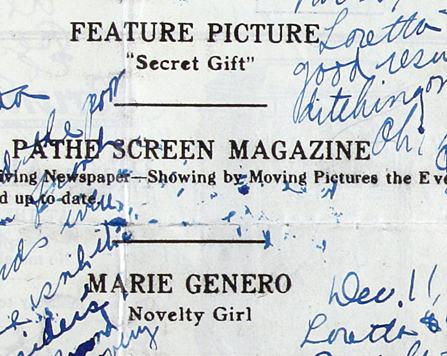

When girls did go to the movies with friends—which always seems to be the case—the screening was only one feature of the afternoon or evening’s or weekend’s entertainment. Case in point: Hattie Selma Stein, Busheys Business Academy, Appleton, WI, 1921-1922. She used a vaudeville program (above, the film Secret Gift is the 2nd turn and the chaser) to record the movies she attended during her year at school. Hattie jotted down the names of her companions, what the weather was like, how they “annoyed” the “nervous humans” seated in front of them, where they had snacks afterwards, and whether she and her boyfriend Perry won the race to the dorm’s porch swing at the end of the evening.

She didn’t always name the movie that served as the pretext for the date. Neglecting to note the film’s title wasn’t unusual in the scrapbooks I’ve examined. Instead, what girls saved was their experience of going to the movies.

For both Hester Swan from Independence, Missouri, class of 1919, and Janet Seidenman, who graduated from Western High School in Baltimore in 1926, food made an evening with friends and films tasty–an adjective which, at the time, meant not only yummy but also “in conformity with good taste.” Swan and twenty others attended a “line party,” featuring Marguerite Clark starring in Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch. “After the show Grape Sherbert and Cake were served. We all had a lovely time and enjoyed the show and refreshments immensely.” In a page of her scrapbook, Seidenman drew an arrow from a caption “Richard Barthlemess [sic] in ‘The Fighting Blade.’ Peanut chews were served and everybody was happy,” to her admission ticket, which she also festooned with an inch-long strip of Kodak film negative.

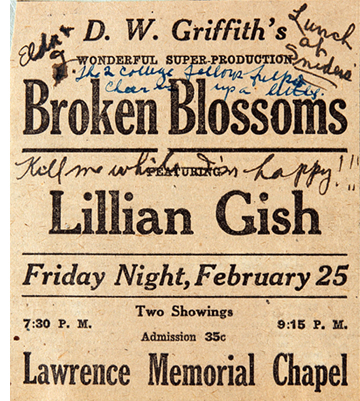

Every so often, though, going to the movies was a special occasion. Girls responded to promotional hype surrounding roadshows. When they saved movie programs, it was invariably from “big” films shown at a theaters which usually presented plays, for instance, the Majestic Theatre in Boston or the Savoy in San Francisco, or motion pictures made on the grand scale by D.W. Griffith. Hattie Stein captioned the ad for Broken Blossoms (right) showing at the Lawrence University Chapel, “Kill Me While I’m Happy.” She also noted that two “college fellows” were on hand to cheer her up and, of course, there was “lunch,” a colloquialism for snacks, at Sniders afterwards.

Girls make fun with movies

Girls did much so more than purchase tickets, sit in theaters, and watch movies before munching on peanut chews. Memory books show that girls around the United States incorporated the movies into their own playful culture. Certainly this is evidence that by the mid-teens, Americans were widely and deeply aware of information about movie stars, narrative conventions, movie-making itself, and the nuts and bolts of film exhibition. I think it’s also akin to the ways girls exercised control over their scrapbooks. When they used movies to make jokes, girls inflected the tone of the film industry’s advertising and narrative messages. They impressed their own proclivities onto increasingly standardized fare. The graduation convention of the class prophecy is a good place to start to see how girls adapted and used the movies for their own purposes.

So you want to be in pictures?

Class prophecies were an American school graduation tradition at least through the 1960s when I completed junior high. They were intended to be light-hearted, funny predictions about the future lives of the members of the class. Prophecies were guided by certain conventions of the form. They were often read publicly during graduation festivities, and it was not unusual to find pages designated for the class prophecy in memory books. Sometimes a prediction hinged on the student’s traits, interests, or romantic inclinations; it could hinge on word play about their name. It was important that the audience got the joke, or most of the jokes.

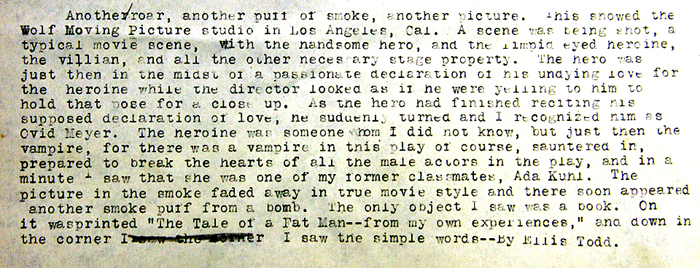

In nearly every class prophecy I encountered written from 1917 onward, at least one student was proclaimed to be destined for a job in the film industry. The most elaborate example lodged in Bertha Glennon’s memory book. Glennon graduated in 1918 from high school in Stevens Point, WI, the small city where I live. In fact, she was the author of her class’s prophecy and it was also her honor to read it aloud at Class Day a few days before the more formal graduation exercises. (She wore a dress of old-rose colored voile for the occasion.) The rhetorical device she created to frame her story was personal, timely, and more than a little macabre. The United States had entered World War I in April of Bertha’s junior year, and she had done her bit by helping to supervise in the Red Cross Room at school where students rolled bandages.