Archive for the 'Directors: Cameron' Category

3D in 2019: RealDvided?

Kristin here:

From August of 2009 to April of 2012, David and I (mostly I) posted a series of entries on the spread of 3D film production and exhibition. The series kicked off with my provocatively titled, “Has 3-D already failed?”. It had a lot of background facts and figures, but the main point was to express skepticism about the extravagant claims that were being made by some in the industry who predicted that eventually most or even all films would be released in 3D. I opined that 3D would probably remain confined to certain genres, mainly animated films and big action pictures. At the time, Julie & Julia was my example of the type of film that would never be made in 3D. Today it could be Can You Ever Forgive Me?

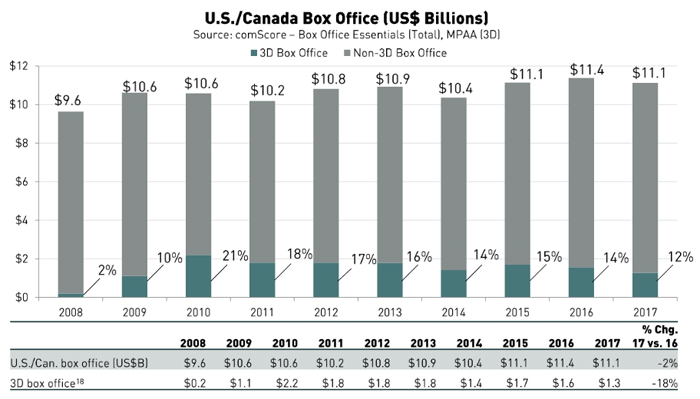

I followed up four times during 2011, as 3D continued to spread. In January I posted “Has 3D already failed? The sequel: RealDlighted.” Hollywood was just coming off the year that 3D admissions as a percentage of total box-office peaked at 21%, to a considerable extent thanks to Toy Story 3. Of the top eleven grossers, seven were in 3D. 3D TVs had become a significant force in the electronics market that year as well, though sales were lower than predicted.

Conversion of screens overseas was also proceeding apace. That surge would eventually fuel the continued production of 3D films in the US, despite their decline in the domestic market.

Already, though, industry commentators were predicting that decline. I cite some of them and their arguments in this entry.

Our entry was followed later in January by the second part: “Has 3D already failed? The sequel: RealDsgusted.” I dealt with the backlash among audiences and critics, especially in the face of conversions of past films to 3D. Not being a fan of 3D, I pointed to the one film in that format that I looked forward to seeing: Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010). It did not disappoint, and its tour of the Chauvet cave, not open to the public, struck me at the time as an ideal use for 3D. I still think so.

In July, in “Do not forget to return your 3D glasses,” I examined the fact that 3D films’ shares of total box-office takings were falling. It wasn’t by much, only from 21% in 2010 to 18% in 2011–but there were more 3D films released that year, and a lot more theaters were equipped by that time to show them.

On August 30, I ended my series with “As the summer winds down, is 3D doing the same?”

In April, 2012, David weight in on the roles played by James Cameron and other powerful directors in pushing digital projection and 3D, in his “It’s good to be King of the World.” That entry, extended and updated, became a chapter in his e-book, Pandora’s Digital Box.

Our series got quite a bit of attention because Roger Ebert, a foe of 3D, cheerfully linked all of our entries.

As it turned out, our series appeared just after the technique had begun its slow drop in the percentage of total box-office receipts provided by 3D screenings.

Assuming the decline has continued, by 2018 that percentage might have been as low as half the high of 21% in 2010 (fueled primarily by Avatar, which was released on December 18, 2009). Will Cameron’s current big 3D project turn the tide? I’ll have a little to say on that at the end.

It has its moments

Ironically, at about the same time that our series closed, we became increasingly interested in the format. Not that we had completely rejected it to begin with. There had been some excellent animated films made by Pixar, Laika, and Disney. The occasional auteur dabbled in the format, as when Scorsese made Hugo (2011). This is a far cry, though, from believing or hoping that 3D would become universally used. Again, who would want to see If Beale Street Could Talk or Vice in 3D?

But the technology improved, and the films got better-looking. More auteurs utilized 3D. There was Cuarón’s Gravity (2013), perhaps the first film in which the 3D effects were utterly convincing. That was partly because so many shots were largely or entirely digitally created and partly because of innovative lighting technology. I still think it’s the only film I’ve seen that is dramatically better in 3D than flat. In 2016, Spielberg made the underappreciated The BFG. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Jean-Luc Godard proved that 3D technology could be simple indeed and still create a masterpiece like Adieu au langage (2014; see here and here). That and Gravity are the only films that I think really must be seen in 3D.

Older 3D films also got a new lease on life through home video. It was the 2012 release of Dial M for Murder on 3D Blu-ray that spurred us to invest in a 3D television. (David saw the screening at the Toronto International Film Festival and wrote about it.)

Interestingly, 3D televisions provide the first method which allows someone analyzing a 3D film to watch it on a personal viewer rather than needing it professionally projected on a screen. You can freeze the frame, and the 3D image hovers before you.

Unfortunately 3D lasted on television for a very short time. By 2012, DirectTV dropped it, and sports, the great hope for 3D television, failed to sustain the format as ESPN stopped showing 3D in 2013. From 2014 to 2017, the major manufacturers of 3D TVs ceased production of them. We shall simply have to nurse ours along or somehow buy a backup machine before it’s too late. Fortunately most 3D Blu-ray discs have been sold as a set with standard Blu-ray copies of the same film, so we can go on watching Moana and Kubo and the Two Strings and others once the set ceases to function. (Robert Silva offers a good rundown on the history of 3D TV, including the reasons for its failure. As he points out, home-theater video projectors with 3D capacity are still available.)

Blink and it’s gone

These days, it seems that unless you live in a large city, if you don’t catch a 3D screening early a film’s run, it will later only be showing flat.

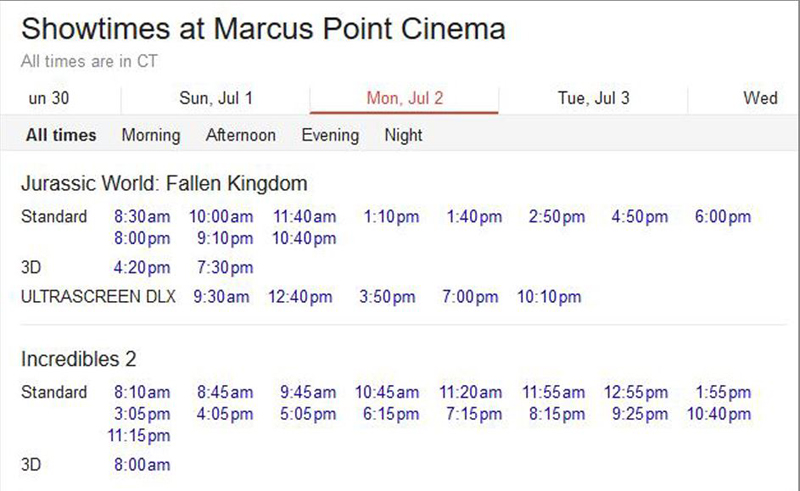

I first noticed this diminution in the number of 3D screenings last summer. Incredibles 2 was showing at our local multiplex, Marcus Point Cinema, part of the Marcus chain of nearly 700 Midwestern theatres, and I wanted to see it in 3D. Checking the theater’s schedule, I was startled to discover that the 3D version was playing only once a day, at 8am. There were 17 showings in 2D. The film had opened on June 15 and thus had been out a little over two weeks.

David and I usually wait for a few weeks to see a popular film so that the crowds will die down. I expected that there would be few people at an 8 am show, so I set my alarm and set out early the next morning for Point Cinema. I purchased my ticket, and as I was moving away from the ticket desk, I heard the woman behind me purchase tickets to Incredibles 2 for herself and her two children. She bought them for the 8:10 am screening in 2D. The children were not too young to cope with 3D glasses, and the family was there early enough to attend the 8 am screening with me. Whether through a wish to save money or simply by preference, they had chosen to see the film in 2D. Indeed, I had the pleasure of a completely private screening.

Another of 2018’s big 3D films was also playing, as the schedule above shows. Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (which I didn’t see) had two 3D screenings per day, against sixteen flat ones. It is notable that five of those were on the “Ultrascreen.” This may suggest that large-screen showings with elaborate sound systems, including IMAX, are more attractive to audiences than 3D, even when these large-screen showing also involve an upcharge. More about that later.

I wondered if this imbalance between 3D and 2D screenings was part of a larger pattern, so I have occasionally checked schedules for other 3D films. Also, might Marcus be limiting the number of 3D screenings so severely, or were other theaters doing the same? On August 1 I looked up the schedule for Mission Impossible: Fallout, showing at two local multiplexes:

Point Cinema was showing the film twice in 3D, four times flat on its Ultrascreen, and nine times “standard,” as 2D on an ordinary screen is now known. Its rival theater, New Vision Fitchburg 18 + Imax, had no 3D screenings at all; as the possessor of our only IMAX screen, it had four flat screenings and seven standard ones.

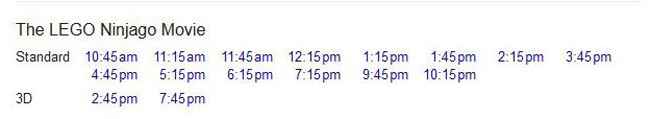

On September 17, I found this schedule for another popular animated film:

Again we see the considerable imbalance, with two 3D screenings versus fourteen in 2D.

Might this imbalance result from the fact that I was waiting a while into the run to check? I looked at Ralph Breaks the Internet for November 26, 2018, the Monday after its opening on Wednesday, November 21:

The same pattern holds even during the first week of the film’s run, in both theaters. In this case, however, the 3D screenings seem to have ended sooner than we expected. We went to Ralph on December 7, and there was no 3D showing available, so we saw it in 2D. The same ended up being the case with Spiderman: Into the Spider-Verse, which apparently had no 3D screenings after its first or second week. That’s a film we have been told would distinctly benefit from being seen in 3D, but we missed our chance. So far it’s not even clear whether the film will be released in 3D for home video.

I decided to try a similar exercise with a much larger city: Chicago. Of the theaters selling tickets on Fandango for Saturday, January 26, 375 screenings were of 2D versions, and eight of 3D films, all of the latter at AMC theaters. One of the latter is of A Beautiful Planet, an Imax documentary. Five of the 3D screenings were of Aquaman and two of Spiderman: Into the Spider-Verse.

I realize that awards season is not the ideal time of year to be looking at statistics of 3D films. Many of the films currently playing in cinemas have Oscar and other nominations, and have been held over to play only a few times a day to take advantage of that fact. On the other hand, there are some films, including Oscar nominees, that could plausibly have been made in 3D a few years ago and were not. These notably include Mary Poppins Returns, Glass, Bumblebee, and First Man. (M. Night Shyamalan has said he would never make a film in 3D, but Glass is the sort of film that another director might have made in that format.) I’ll try the same exercise during the summer movie season and see what the balance is. I’m sure there will be more 3D screenings proportionately than there are now–but probably not as many as in 3D’s heyday of 2010 to 2013.

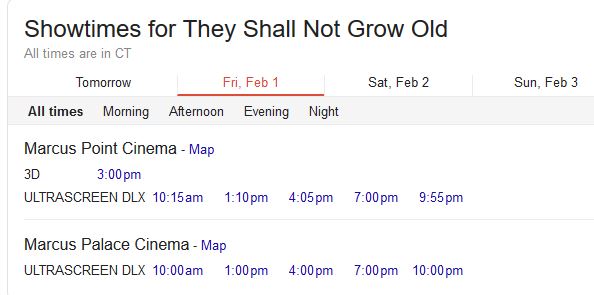

Even an event film that depends heavily on its flashy technical aspects, Peter Jackson’s restored, colorized, 3D-ized, sonorized documentary, They Shall Not Grow Old (2018), was shown here in Madison more often in 2D. It played on two days in late December. On the first day, 3D was available, but we saw it on the second and had to settle for 2D. It was brought back again recently for a short run, and we saw it again, this time at the single daily 3D matinee screening available. There were five 2D shows on the Ultrascreen.

This time Marcus’ other local multiplex didn’t show it in 3D at all.

We thought that seeing They Shall Not Grow Old in 3D was interesting and worthwhile. Still, we had thought it very effective without the 3D. The restoration, color, and sound were the most remarkable parts of Jackson’s transformation of the old footage.

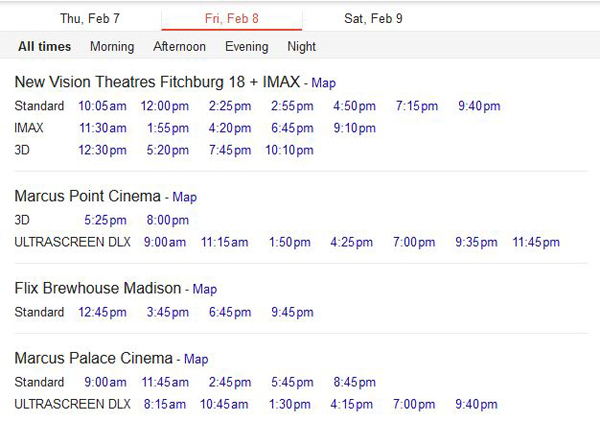

All of these schedules are for 3D films that had been running for a while. I also, however, checked the opening Friday, February 8, for The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part. (It opened Thursday, February 7, but Friday was the first day with a full schedule.)

Four theaters, including three multiplexes, were playing the film that day. There were a total of 40 screenings, 16 of them standard, 18 in IMAX or Ultrascreen DLX auditoriums, and six in 3D. None of the latter were on large-format screens. As in earlier cases, the Marcus Palace Cinema had no 3D screenings, even for the opening weekend; it does have 3D capacity. It has two Ultrascreen DLX auditoriums, which the managers seem to favor over 3D. Flix Brewhouse Madison does not have 3D facilities, but as its name implies, one can consume sandwiches, beer, and so on while viewing films.

PLF vs 3D

This reluctance on the part of theaters to devote their screens and time-slots to 3D reflects the general decline in the format. According to Variety, ever since Avatar (2009) pushed cinema owners to invest in 3D equipment (and in the case of those who hadn’t converted yet, to switch to digital projection), 3D has declined. From $2.2 billion in grosses in 2010, fueled largely by Cameron’s film, the figure had shrunk to $1.3 billion in 2017. That year only 44 films were released in 3D, dropping from 52 in 2016.

We’re all familiar with the reasons for this, which we discussed in our series linked above and which continue to be chewed over in the press. People don’t feel the upcharge is worth it. Small children can’t keep the glasses on. Some moviegoers get headaches from the glasses. The projection system and the glasses often create a dimmer image. Virtually all 3D live-action films have some shots converted to 3D in post-production. The post-production conversion process has improved, but some early shoddy post-production conversions gave people the idea that only native 3D films are worth watching.

Theater owners and managers have their own set of reasons for not wanting to show 3D. We haven’t been able to find out the range of terms distributors set for theaters renting a film. Are 3D screenings required for any film offering that option? Are there minimum numbers of screening? Must the screenings be in auditoriums of a minimum size? How long does the 3D run have to be? Still, I have gleaned a bit of information from people involved in exhibition.

One employee of a multiplex told us that a film released in a 3D format had to be given some 3D screenings at the opening week of the run. The exhibitor could then continue the 3D shows if the box-office receipts warranted it. This makes sense, as the distributor is getting a cut of the takings. Given 3D’s decline in popularity, this pretty much explains the pattern of the small numbers of screenings reflected in the schedules illustrated above.

The owner of one Midwestern small-town theater pointed out to us that the 3D upcharge in itself hurts the theaters. He declined to convert to 3D back when distributors were pushing theaters to do so. At the time, he recalls that about fifty cents of the proposed $2 upcharge went to the 3D firm and the distributor got a percentage of the remainder. Moreover, as he put it, “For a family of four that’s $8 less for vending – that’s my reasoning.” As we know, movie theaters typically depend on their customers buying expensive treats at the concession stand (and increasingly on meals, whether consumed in their theater seats or at a restaurant positioned in the lobby) to make a profit.

3D also is losing out to an attraction that moviegoers are proving more willing to pay extra for: PLF or Premium Large Format auditoriums. The most high-profile of these is IMAX, which starting out in the 1970s as a largely museum-based attraction showing its own short documentaries. It branched out into occasionally showing studio feature films, starting with Disney’s Fantasia 2000 (2000) and continuing with such event films as the last five Harry Potter installments. It was when IMAX films went from being shown on 70mm film to a digital format (introduced in 2008) that it really took off, since existing multiplexes could convert an auditorium to an IMAX venue. From 299 screens worldwide in 2007, IMAX expanded to 1302 by September, 2017. Of those, 1203 were in multiplexes.

For much of this time IMAX screenings were often in 3D. With the waning popularity of that format, however, in July, 2018, IMAX announced that it was cutting back on 3D. The success of Dunkirk in 2D IMAX was cited as proof that people would accept even a period war film not involving Americans if shown in the large format and flat. The announcement specified that IMAX screenings of the forthcoming Blade Runner 2049 would be only in 2D. The fact that Christopher Nolan had shot much of Dunkirk using an IMAX film camera became a publicity point for the film. Similarly, the fact that Cuarón shot Roma in digital large-format featured in popular coverage (the camera was an Alexa65). The irony that the film would mainly be seen on TV screens was not lost on commentators, but at least it received a limited theatrical release, including 70mm screenings. Large, sharp, flat images were winning out over 3D.

The Ultrascreen DLX mentioned above in some of the Marcus schedules is a somewhat smaller version of IMAX combined with luxurious surroundings. The chain’s website provides details.

The UltraScreen DLX® concept features three important S’s – screen, seating and sound. A massive screen size coupled with HEATED DreamLounger℠ leather recliners provide maximum comfort, including a spacious seven feet of legroom between the rows of seats. Add immersive, multidimensional sound for a lifelike experience that makes guests feel part of the action. Speakers are located in the front, back, sides and ceiling to bring even more dimension to the audio of a film.

The system of speakers described is an Atmos installation.

Theater chains typically brand their own PLF installations. Ultrascreen DLX is Marcus’ version, while the B&B chain (the country’s seventh largest, operating mainly in the plains states) has its B&B Grand Screens (see bottom). The first was introduced in 2010 in St. Louis. Some chains mix IMAX with their own brand, depending on the local market. Regal, for example, has 87 IMAX houses and 89 with its proprietary RPX screens. (For a detailed history of the spread of PLF installations to 2016, see Daniel Loria’s “Large Screens, Premium Experience.”)

In many cases, these large-screen auditoriums include other “premium” aspects, such as the big reclining seats, wide gaps between rows, and elaborate sound systems. As with 3D, the ticket price involves an upcharge, but since no fee goes to the 3D company for the glasses and other expenses, the theater owner keeps more of that extra money.

Blame China

It’s common to point out that China, now the world’s second largest movie-exhibition market and soon to become the first, loves 3D. The Chinese are building new theaters at a fast clip, and a high proportion of the new screens have digital 3D capacity. In fact, in 2016, fully 78% of screens in the Asia-Pacific region could show 3D, an astonishingly high proportion considering that in the US the figure was half that, at 39% (according to IHS Markit). And that 78% was a share of far more theaters, 46,949 3D-capable theaters in the region versus 16,745 in the US. Undoubtedly China’s share was larger than its neighbors in Eastern Asia and the Pacific Rim. Other areas of the world also had higher proportions of 3D screens than the US, though not by nearly as much. Europe, the Middle East, and Africa together had 45% 3D screens, and Latin America 43%.

Thus the common wisdom is that Hollywood continues to make 3D films to a large extent to cater to Chinese enthusiasm for the format. Indeed, some films that are released only in 2D in the States are shown in 3D in China, including 2012 (2009), Looper (2012), Iron Man 3 (2013), Lucy (2014), Transcendence (2014), and Jason Bourne (2016). The latter ended up nauseating quite a few Chinese viewers, given its “run-and-gun” style compounded by the 3D.

Naturally Hollywood wants to cater to this giant market, even though the percentages of the ticket receipts returned to the American studios by Chinese distributors are considerably lower than in the US and other markets.

So why show 3D films in the US at all? Presumably there remains enough of a market for them that studios don’t want to risk leaving money on the table. Since they’ve laid out the extra money to make a film in 3D, they might as well show it. There are presumably some people, especially teenagers, who are much more likely to see a film if it’s in 3D.

The question is, will the slow decline of 3D, with fewer films made each year and a lower share of the box-office contributed by them, eventually lead to the complete demise of 3D? Will the failure of 3D TV mean that fewer and fewer 3D films will be released for home-video in 3D? Already this has happened to some extent.

In 2014 for the first time Disney released one of its successful 3D animated films, Frozen, only on standard DVD and Blu-ray. It has continued this policy. In England, though, some Disney films are still released in 3D Blu-ray. Remarkably, amazon.com offers the imported region-free Irish 3D Blu-ray, Blu-ray, and DVD combo of Moana at a bargain price, and it’s not from a third-party seller. We may be out of luck with Ralph Breaks the Internet, since Amazon UK has announced a Blu-ray-DVD set, with no 3D option.

I for one would regret the total demise of 3D. There are relatively few films that I strongly prefer to see in their 3D versions, but it would be a pity if filmmakers did not have the option of making a film like Gravity or Cave of Forgotten Ancestors or Moana in 3D.

It may happen, though. In mid-January an online post in Chinese speculated that people there were becoming less obsessed with 3D. (The original Chinese piece is here, with a brief summary in English here.) How long might take for Chinese moviegoers’ enthusiasm to cool to the extent it has in the USA? Perhaps within a few years China and other overseas markets will no longer provide an adequate support for 3D.

The return of James Cameron

While the world awaits the four threatened sequels to Avatar (currently announced for 2020, 2021, 2024, 2025), we have another another Cameron project to re-excite us about 3D. Originally Cameron had planned to direct Alita: Battle Angel himself, but given the burden of responsibility for all those sequels, he turned those duties over to another advocate of 3D, Robert Rodriguez, with Cameron producing and co-writing. (Sin City is much admired by 3D fans.)

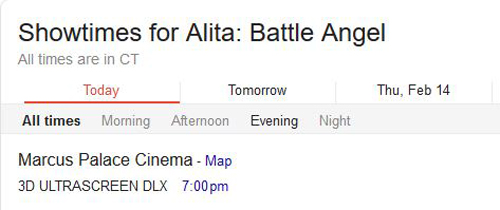

I post this on the second of two days featuring special evening screenings of Alita only in 3D, even as it shows. This has literally been publicized as an event movie, an “Early 3D Fan Event.” (See top.) Only one of our local multiplexes is showing this early screening. Interestingly, it’s the Marcus Palace, which seemed to avoid 3D for the earlier films for which I checked. This being a special fan event, modest swag is involved.

Cameron must be disappointed that 3D has not spread to the point where all screenings of Alita could be in 3D. The existence of this “3D fan event” basically acknowledges that there is a core audience for 3D and another audience, probably much larger, who usually, if not always, would prefer standard screenings. The 3D fans presumably are inclined to come to the film when it first opens, and this event caters to that habit–and ideally generates favorable word-of-mouth for the 3D version.

The film has had a mixed reception from critics, with a 60% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Nearly all the reviews I have read, even favorable ones, fault the script but praise the visual effects (by Weta Digital). Most do not mention the 3D. One enthusiastic reviewer, Molly Freeman on Screen Rant, did mention and laud the 3D, writing, “However, the true star of the movie isn’t the writing or any of the performances, it’s the visuals. To the filmmakers’ credit, the visuals are absolutely stunning and if moviegoers have to choose only one 2019 release to see in IMAX 3D, Alita: Battle Angel is it.” This is a good news/bad news comment. On the one hand, Cameron would be glad to see the 3D in this film recommended so highly. On the other, it does suggest what is happening in reality: that many moviegoers are avoiding 3D unless it has the sort of event cachet that has been created around this particular film. And only time will tell whether audiences will take this advice, at least after the first week or two. Initial reports are not sanguine.

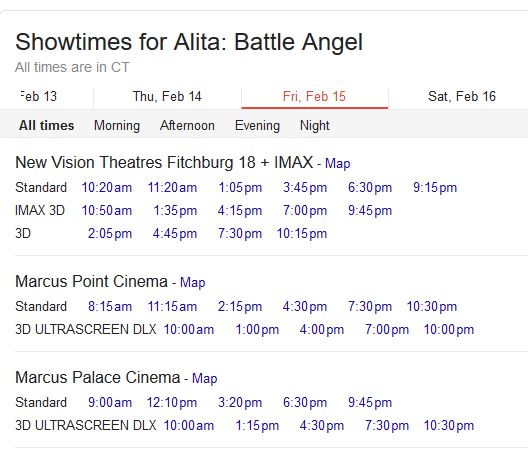

Early on in the run, the Alita will be showing on many screens, PFLs or not. The opening weekend, February 15-17, has this set of offerings in Madison:

Setting aside the IMAX screenings, New Vision has opted for one fewer 3D showings than standard ones. The two Marcus multiplexes have no 3D screenings apart from on their Ultrascreens. The same pattern carries into the following weekdays, except that New Vision has no morning matinees. (The Marcus cinemas, as we’ve seen, starts some screenings as early as 8 am every day.) Marcus management seems to assume that 3D is less appealing on a regular screen than a PLF one, despite the double upcharge. This upcharge, by the way, is significant, especially for a family. An adult ticket for a 2D screening at New Vision costs $11.40, a 3D ticket $15.10, and a 3D IMAX ticket $17.21. That’s just about 50% more for the highest ticket than the lowest.

A news item about Alita reveals one more reason why theater managers might not be overly keen on showing 3D. We all know that 3D glasses are notorious for cutting down the brightness of the projected image. It turns out, however, that there’s much more to it than that. Projecting 3D is not simply a matter of slapping a different lens onto the projector and ingesting a DCP file into the projector, as a fascinating article on Rerelease News reveals. Theaters receive several DCP files, and which one they use depends on the sort of projection set-up they have. Given that projection is now done by people with minimal training, the wrong file sometimes is used. Cameron, Rodriguez, and Jon Landau (who also was a producer on the film) were clearly concerned about this and included a message to theaters playing Alita:

IMPORTANT 3D NOTE: The key to the 3D experience is the light. You have been provided with both a general release 4.5 FL 3D DCP and a premium 6 FL-XBrite 3D DCP. Projecting an XBrite 3D DCP at the standard 4.5 Foot Lamberts of light will result in a dark, hard-to-see presentation. It was especially color graded at 6 foot lamberts and must be run at 6 FL. Projected in this way, it will look amazing!

Conversely, if a general release 3D DCP is shown at 6 FL it will look overly bright. It must be run at 4.5 Foot Lamberts, and it will look terrific at that light level. Since you may have some auditoriums capable of running at 6 FL 3D with others that can only hit 4.5 FL 3D, please confirm that the correct DCP file is loaded in the appropriate theater and that each is run at its proper light level.

This will make a huge difference in the presentation and to audience enjoyment. Thanks so much from Robert Rodriguez, Jon Landau, and Jim Cameron.

I’m sure this is excellent advice, and I hope it is followed, especially at the Marcus Point multiplex near us. Still, I suspect not all theater managers enjoy being confronted with this sort of complexity.

The takeaway from all this is that I and I’m sure many others, were right in predicting that 3D would remain a niche within popular cinema as a whole, confined largely to animation and to fantasy and sci-fi films. More interesting, though, is the fact that PLF auditoriums have proven more popular as a reason to get off the couch and go to a theater, even if the comfort, spaciousness, mega-multi-track sound, and huge screens come at a higher ticket price.

Thanks to David Hancock of IHS Markit for his assistance over the years. Also, thanks to Steve Guttag and Russ Collins for information about 3D. For the story of how 3D became the Trojan Horse in the digital conversion of theatres, see Pandora’s Digital Box.

Thanks also to Jim Healy for some expert opinions and for pointing me to the Rerelease News piece.

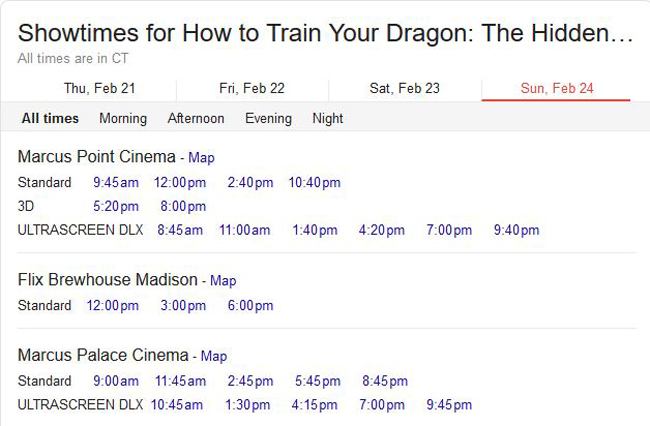

PS [Added February 18, 2019] More evidence, for the opening weekend of How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World here in Madison:

[PPS March 6: Tomorrow will be the last 3D showing in Madison, at 5 pm at Marcus Point. After that it will shown only in standard or PLF.]

The Gearheads

Mourning.

DB here:

At the Wisconsin Film Festival I saw the best film I’ve seen over the last six months. I can’t really say much about it, but I’ll do what I can. My remarks make most sense, I think, if I embark on a pretty long detour.

The frame-rate shuffle

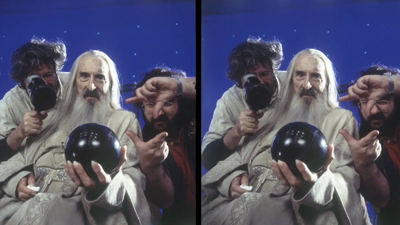

3D still photographs by Peter Jackson taken during the filming of the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

In the wake of April’s convention of the National Association of Theater Owners, the biggest press tumult surrounded Peter Jackson’s ten-minute demo from The Hobbit. Fulfilling what James Cameron had called for at the 2011 NATO confab, Jackson has been shooting at 48 frames per second, and the demo was screened at that rate. Cameron and Jackson are concerned that there’s too much image judder and strobing in digital cinema, especially 3D. They propose a higher frame rate to smooth things out.

Opinion on the Hobbit footage was divided. Some theatre owners and operators were happy with it, but others were uneasy. The higher frame rate tends to eliminate motion blur and create a sharpness that recalls, for some viewers, the brittle look of HD sports broadcasts. “It looked to me like a behind-the-scenes featurette,” said one.

Jackson, who has been preparing for this initiative on his Facebook page, defended his decision. He maintains that audiences will adapt to it, just as his production team has. Many exhibitors seem to have dismissed the new initiative as too expensive, particularly at a time when many are still paying off the digital conversion. But the Regal Entertainment Group, the largest cinema chain in the US, announced plans to outfit up to 2700 screens so that The Hobbit can be screened at 48 fps. It now seems possible that The Hobbit may be shown in no fewer than six formats: 2D, 3D, and Imax, and in each there will be both 24 fps and 48 fps presentations.

Not being present to watch the footage, I have to withhold judgment about how it looks. I haven’t though, withheld my opinion about how Cameron and Jackson, along with George Lucas, have used their roles as superstar directors to prod exhibitors to adopt expensive new technology. They acted as the figureheads for the switch to digital in 2005, using 3D as the incentive for exhibitors to convert. A few years later, after proposing 3D television, Cameron upped the ante by urging higher frame rates for film. Jackson has joined him by actually making a film at 48 fps. Cameron has said he prefers 60 fps, which may mean that the goal posts get shifted again when Avatar 2 or something else comes along.

You can go to my earlier post for more thoughts on their tactics. My book on the digital conversion, due out on this site in a few days, offers a fuller account. In the meantime, I’m going to try to understand this frame-rate fracas in a wider historical context.

The palette

Cinema technology has been surprisingly stable, as befits its status as the last surviving nineteenth-century engine of popular entertainment. The dimensions of the film strip, the rate of shooting and showing, and other fundamental factors have altered relatively little. The coming of sound and then the replacement of nitrate-based film by acetate are perhaps the biggest alterations in the basic technology. Below this macro-level, though, innovation has been constant.

From the 1920s through the 1960s, most of the change came in the production sector. The adoption of panchromatic film stock; color processes, principally Technicolor and the monopack systems like Agfacolor and Eastman Color; the development of various lighting units (carbon-arc, incandescent, Xenon); the shift from optical sound recording and reproduction to magnetic processes; the emergence of different sorts of camera support (varieties of tripod, dollies, and cranes, along with handheld devices)—all of these shaped how movies were made but had relatively little effect on how they were shown.

Some 1950s innovations launched in the production sector, notably widescreen cinema, stereophonic sound, and 3D, reshaped exhibition more drastically, because they came at a moment when theatres were anxious to lure back their clientele. Other revampings of exhibition, like wide-gauge film (65mm/70mm) and Cinerama, were never intended to be the universal standard. They were designed for a distribution system that included roadshow exhibition. Dedicated screens showcased big films like The King and I and Lawrence of Arabia for long, well-upholstered runs before the film hit the neighborhoods and the suburbs.

Producers innovate and exhibitors hesitate. Exhibitors must be cautious and conservative; they risk revamping their venue at great cost only to find that the new technology isn’t catching on. The roadshow system repaid exhibitors well, until it collapsed in response to the rise of saturation booking in the 1970s. For similar conservative reasons, exhibitors looked askance at the digital sound reproduction technologies that emerged from the 1970s through the 1990s. At one point, a house had to accommodate four different sound systems, some of them subject to periodic upgrades.

When technologies emerge in the production sector, they mostly promise to enlarge the filmmaker’s palette. A 1950s film could be made black-and-white or color, deep-focus or soft-focus, with arc or incandescents, flat or anamorphic, and so on.

In practice, of course, not everything was possible on every project. Budgets, as ever, limited options, and many directors and DPs disliked shooting in color or CinemaScope but were obliged to do so. And there were some trade-offs. Filmmakers of the 1930s could not shoot on orthochromatic stock, and after the mid-1950s, it was hard to make a film destined for the classic 1.37 Academy ratio. Still, there were few absolutely forced choices, and many directors explored different options from project to project.

The prospect of an enhanced palette is in fact one reason that some filmmakers embraced new technologies. Sergei Eisenstein (who trained as an engineer) was eager to try out sound, color, and even television because they expanded creative choice. Orson Welles saw in the RKO effects department, which had pioneered sophisticated optical-printer work, a way to create images that couldn’t be generated in the camera. As is now widely known, many of Citizen Kane’s most famous “deep-focus” shots were achieved through special effects. Similarly, Stanley Kubrick renewed the power of his images through his eager adoption of new technologies, including long lenses for Paths of Glory, the handheld camera in Dr. Strangelove, faster lenses for Barry Lyndon, and the Steadicam for The Shining. These filmmakers wanted to multiply options, not foreclose them.

Share our fantasy

The changes that Cameron and Jackson propose are more sweeping. Now that digital projection is an accomplished fact, there will be backward pressure to create a wholly digital workflow. Filmmakers who want to shoot on 35mm will be reminded that they will eventually be fiddling with a digital intermediate, and that the final version will be digital, not film-based. A selling point of digital cinema to the creative community was the promise of complete control over the film’s look and sound, so that the audience gets exactly what the filmmaker envisioned. To assure that integrity, the director will have to shoot and finish the project on digital. That will take away an entire dimension of choice—specifically, shooting on film.

The pressure to shoot 3D adds to this. Martin Scorsese and Ang Lee showed up at the same NATO convention to praise the format. Now films that aren’t tentpole items can be made in 3D, they agreed. According to Variety, Scorsese claimed that “2D projection [sic] will eventually go the way of black-and-white—used primarily as a stylistic choice—as auds will soon acclimate to depth even in indie films.” This sounds like a widening-of-the-palette defense, as does his reaction to new frame rates. “You can do anything you want [in post-production] with that image at that level of clarity, can’t you?”

In contrast to Scorsese’s offhand pluralism, Cameron, Jackson, and their confrère Lucas may be creating a scorched-earth policy. Their conception of cinema, I would say, is now largely that of the Gearhead. Their notion of artistry has become quite mechanical, in that they see progress to depend almost wholly on improved hardware (and software).

They represent three mini-generations of Hollywood techno-lover: Lucas, who began in animation; Cameron, who started as a model-builder; and Jackson, the 1980s fanboy who played with King Kong action figures. They are directors who treat cinema as a delivery system for stories grounded in genre conventions. Fantasy is their touchstone, and realism of any sort bears only on how vividly we perceive the images, not what the films show or say or suggest.

Back in 1999, Lucas noted frankly that film was becoming a form of painting, “unfixing the image.”

You have news footage, you have documentary footage—which are supposedly realistic images—and then you have movies, which are completely fantasy images. There’s nothing in a movie that’s true or real—ever . . . . The people in the movie are actors playing parts. The characters are not real. The sets are not real. If you go behind that door you’ll see there’s no building—it’s just a big flat piece of wood. Nothing is real. Not one little tiny minutia of detail is real.

The Hollywood cinema was then putting fantasy and special effects at the center of its aesthetic, and Lucas understood that every film—action picture, romantic comedy, even dramas—would rely on special effects to a new extent.

Here’s Cameron saying the same thing in defending 3D in 2008.

Godard got it exactly backwards. Cinema is not truth 24 times a second, it is lies 24 times a second. Actors are pretending to be people they’re not, in situations and settings which are completely illusory. Day for night, dry for wet, Vancouver for New York, potato shavings for snow. The building is a thin-walled set, the sunlight is a Xenon, and the traffic noise is supplied by the sound designers. It’s all illusion, but the prize goes to those who make the fantasy the most real, the most visceral, the most involving. This sensation of truthfulness is vastly enhanced by the stereoscopic illusion.

It’s hard to believe that Lucas and Cameron don’t know the long tradition of debate in the arts about realism. Realism can be considered a question of subject matter, plot plausibility, random detail, psychological revelation, and many other things; it isn’t just about trompe l’oeil illusion. Moreover, documentary and experimental filmmakers have suggested that cinema can capture moments of unplanned truth. And André Bazin and others have argued that even when presenting fictional tales, photographic cinema gives us unique access to some essential qualities of phenomenal reality. For Bazin, even an awkwardly shot scene could preserve the sensuous surface of things with a conviction that no painterly manipulation can equal—not perfection but brute facticity. Instead, Lucas and Cameron offer a Frank Frazetta notion of realism: glistening, overripe, academically correct rendering of things we’ve seen many times before.

Turnstile dynamics

NATO’s 2005 ShoWest convention: Lucas, Robert Zemeckis, Randal Keiser, Robert Rodriguez, Cameron.

I see a valid place for a cinema of splendor and spectacle, especially in certain genres. There’s nothing wrong with seeking new methods of pictorial representation, as Spielberg did in Jurassic Park, a genuine triumph of veridical realism. Nor am I trashing Lucas and Cameron wholesale; I admire their early films a fair amount. But they’re forcing their conception of cinema on all filmmakers.

Am I being unfair? I don’t think so. When directors say that digital or 3D or 48 fps is the future of cinema, they’re implying wholesale conversion is in the offing. Although Scorsese says that 2D or another frame rate will remain an option, Cameron and Jackson aren’t quite so open-handed. Because they’re convinced that the result is much more immersive, and immersion is always good, the technology should suit every kind of movie. Cameron again:

It is intuitive to the film industry that this immersive quality is perfect for action, fantasy, and animation. What’s less obvious is that the enhanced sense of presence and realism works in all types of scenes, even intimate dramatic moments.

Both directors usually add that they’re not insisting that every film is suited to the new bells and whistles, that it has to suit the plot and so on—the usual boilerplate about the primacy of “story.” “Stereo [imagery] is just another color to paint with,” says Cameron.

But they sound as if not having 3D or 48 fps puts the movie at a disadvantage. Cameron in 2008:

Every time I watch a movie lately, from 300 to Atonement, I think how wonderful it would have been if shot in 3D.

Jackson in 2011:

You get used to this new look [48 fps] very quickly. . . Other film experiences look a little primitive. I saw a new movie in the cinema on Sunday and I kept getting distracted by the juddery panning and blurring. We’re getting spoilt! . . . There’s no doubt in my mind that we’re headed toward movies being shot and projected at higher frame rates.

As happened before, the pronouncements of the directors mesh well with the initiative of the manufacturers. Back in 2005, Cameron, Lucas, Jackson, Robert Rodriguez, and Bob Zemeckis took to the NATO stage to help sell the Digital Cinema Initiatives program to skeptical exhibitors. Their support (and the box-office numbers of the 3D Chicken Little) aided the projector manufacturers Christie, Barco, NEC, and Sony in rolling out units. The number of digital screens in the US and Canada jumped from ninety in 2004 to over 300 at the end of 2005.

This year, with about two-thirds of all US screens fully converted, Christie circulated a promotional leaflet tied to Jackson’s demo. A few years ago, the future was all about 3D, but now, the text states flatly, “The future of cinema is all about high frame rates.” The cards are on the table.

At just 24 FPS, fast panning and sweeping camera movements that are a critical part of any blockbuster are severely limited by the visual artifacts that would result. . . .

The “Soap Opera Effect” has been derisively used to describe film purist perceptions of the cool, sterile visuals they say is [sic] brought on by digital.

But the success of Hollywood, Bollywood and big-budget filmmakers around the world has little to do with moody art-house films. The biggest blockbusters are usually about immersive experiences and escapism—big, vibrant, high-action motion pictures.

The HFR system, then, aims to spiff up franchises and tentpoles, and all other filmmaking must be dragged along and adjust. Although Jackson says he has heard no plans to charge more for 48 fps shows, Christie thinks we would pay for this treat:

Beyond the simple turnstile dynamics of “must-see” movies, a new, higher standard of movie-going should support premium pricing. Managed right, hotly-anticipated 3D HFR should empower ticket up-charges.

By all signs, the churn won’t stop. “Every three months you’re behind,” says Ang Lee. “We’re guinea pigs.” David S. Cohen, technology writer for Variety, believes that 48 fps is a transitional technology and that 60 fps will win out (“but not soon”). He adds: “Bizzers in both TV and movies are going to be making creative and financial decisions about HFR for years—maybe forever.”

Lucas and Cameron, and then Jackson, grasped that if cinema technology went wholly digital, it would change in fundamental ways. It would turn a medium into a platform, like a computer operating system. The most basic technology of showing a movie would become subject to rapid, radical, ceaseless remaking. It would demand versions, upgrades, patches, fixes, tweaks, and new software and hardware indefinitely.

I’m not sure that NATO’s members have fully realized this. They went into the deal lured by the chance to raise ticket prices and thus offset flat or slumping admission numbers. But attendance is still stagnant, even with the occasional stupendous successes like Avatar and The Avengers. Interestingly, AMC, one of the Big Three circuits that invested heavily in digital projection, is reportedly in talks to sell out to Chinese investors, and other chains are on the auction block. The studios are proceeding with VOD plans that may thin theatrical attendance even more.

Meanwhile, exhibitors face a long future of payouts. When cinema goes IT, as Steve Jobs might put it, we should expect a big bag of pain.

And now for something completely different

I saw Morteza Farshbaf’s Mourning (Soog) on a so-so DigiBeta copy at the Wisconsin Film Festival. This Iranian feature was shot on some godforsaken digital format, certainly nothing that Cameron and Company would approve. For all I know, its camera movements may have strobed unacceptably. I didn’t care.

Cameron et al. claim to worship the god of Story, but no film they’ve made has this subtle a grasp of narrative. Mourning gives us a plot so full of twists—in terms of what happens and how we learn about it—that I can’t summarize even the basic situation without subtracting some of your pleasure. A man and a woman are driving a little boy through a landscape. That’s about all I can tell you.

The film critics at Christie would consider it a moody art-house film. It’s also simple, suspenseful, and surprising, even shocking. It is formally inventive, emotionally poignant, and respectful of its characters and its audience. It is gentle but also unflinching. It’s the closest thing to Chekhov I’ve seen onscreen in a long time.

Was I immersed? Yes, but not in the way Cameron et al. define that state. I was trying to figure out what had already happened, what was happening at the moment, and what might happen next. And maybe I wasn’t seeing things “realistically,” in the 3D sense, but I was seeing something that captured the world we live in—our surroundings (and their stubborn physicality) and our relations to others. That world was also poetically heightened through the most straightforward means: camera placement, lighting, cutting, sound design. The film was, in other words, working in ways that we have always considered central to cinema’s creative mission.

Mourning is part of the fine Global Lens program of circulating features. Here’s a schedule of where and when films in the program are playing. Ask your local festival or art house to book Mourning, or try to see it when it’s available online or on disc. It’s even worth an upcharge.

Lucas’s remarks on realism come from “Return of the Jedi,” an interview with Don Shay in Cinefex no. 78 (July 1999), 18. Figures on the adoption of digital cinema are taken from the report, “Digital Cinema Roll-Out Begins,” Screen Digest (April 2006), 110. A detailed video explaining Hobbit production methods is here, as part of the video diaries on Jackson’s Facebook page. For more from a veteran, see “‘The Hobbit’: Douglas Trumbull on the 48 Frames debate.”

After writing this, I found that Devin Faraci of Badass Digest has a vigorously critical entry on the footage and even calls Jackson and Cameron “gearhead directors.” So I can’t claim originality, but it’s nice to know I have a badass ally.

Thanks to Jim Cortada, author of the forthcoming Digital Flood and Co-Director of the Irvington Way Institute, for explaining IT matters to me.

P.S. 11 May: Christopher Nolan, still embracing film-as-film, claims he’s no gearhead.

It’s good to be the King of the World

DB here:

Every spring the National Organization of Theatre Owners holds a convention and trade show in Las Vegas. It’s now called CinemaCon, but in earlier times it was known as ShoWest. The gathering assembles thousands of exhibitors from around the world. Directors and stars show up to publicize summer and fall releases. There are screenings, award ceremonies, display booths, and panels about everything from sound systems to popcorn pricing.

The convention is always an extravaganza, but in 2005 things were particularly stirring. Then fewer than a hundred US screens were digital. To ShoWest 2005 came three of the most financially successful directors in history: George Lucas, James Cameron, and Robert Zemeckis. Robert Rodriguez joined them, and Peter Jackson participated in a prerecorded video clip. Their mission: to sell digital cinema.

Battle angels

James Cameron and George Lucas at CinemaCon 2011.

Cameron and company knew that the exhibitors needed a rationale for switching that would actually enhance their business. The killer app for digital screening, these directors and others had decided, was 3D.

Lucas claimed that he was hoping to re-release the first Star Wars in 3D in 2007. “We’re giving you two years,” he said pleasantly. Zemeckis announced two 3D films in preparation. In a 3D film clip, Jackson said, “I’m looking forward to one day seeing Hobbits in 3D.” Cameron, who had started working with 3D back in the 1990s, was fresh off the January release of Aliens of the Deep in IMAX 3D. He promised the exhibitors Battle Angel, telling Lucas, “You can have all my theatres when Battle Angel moves out.”

One argument was that 3D offered a way to build the business. 3D screenings would bring in new audiences who seldom went to ordinary movies. More important, the enhanced format would justify higher ticket prices. But of course 3D would necessitate moving to digital projection.

No Battle Angel and no Star Wars IV showed up in 3D, but the celebrity directors kept their word to some extent. Zemeckis led the pack with Beowulf (2007), and Avatar (2009) cemented the deal. With its record $2.7 billion worldwide box office, the latter convinced exhibitors that digital and 3D could be huge moneymakers. In 2009, about 16,000 theatres worldwide were digital; in 2010, after Avatar, the number jumped to 36,000. 3D was the killer app, or Trojan Horse, that pressured exhibitors into going digital.

But here’s the funny thing. At the 2005 confab, the directors summoned up an explanation that goes back to the days when TV threatened the movie trade: You need something special to yank viewers off their couches. In 1953, the bonus was widescreen color images and stereo sound. In 2005, the bonus was stereoscopic projection. All tentpole pictures, Cameron claimed, would be in 3D. “With digital 3D,” he said, “we now have a reason to get people out of their houses from in front of their flatscreen, high-definition TVs and back to the movies.” The premise was that 3D wouldn’t be feasible at home.

Now let’s jump ahead. It’s the 2011 conference of the National Association of Broadcasters. 3D TV is starting to arrive. Celebrity director James Cameron visits with his business partner Vince Case, who have formed the Cameron Pace Group. According to Variety his message to the TV people is:

Your business is about to go 3D. . . . [He said that] the transition to 3D televison as going to happen much faster than usually predicted, even as soon as five years [when] “everything is in 3D and people demand 3D the way people used to demand color, and if you’re not broadcasting in 3D you’re not playing the game and you’re not getting any revenue.”

In 2005 Cameron told filmmakers and exhibitors to shoot in 3D to outrun television. Six years later, when nearly half of movie screens are digital, he advised broadcasters to adopt 3D as fast as possible.

It’s probably not irrelevant that the Cameron Pace Group supplies 3D cameras and assistance to both filmmakers and TV production companies. During the following year, the group announced, it was a 3D equipment provider for CBS Sports and ESPN.

Lest Cameron’s message be missed, he and Pace reiterated it earlier this month. At NAB’s convention he said that sports was only the beginning. Episodic television can also be shot quickly in 3D and easily converted to 2D. Television can’t confine itself to one-off shows or a 3D channel: “We have to hit a critical mass of enough entertainment in 3D.” “The future of 3D,” he told an interviewer, “will be defined by TV.”

Leapfrog

James Cameron and Vincent Pace.

Where does this leave film? Having convinced exhibitors to go digital and to install 3D rigs in their booths, what does Cameron propose to offset the rise of 3D TV? He came to last year’s CinemaCon with a new “incentive”—now all stick and no carrot.

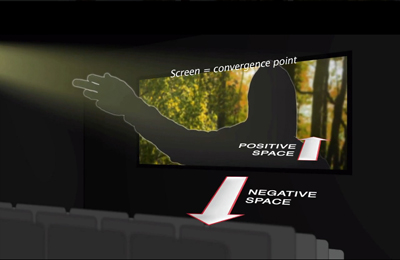

It’s well known that one problem with 3D cinema is a dimmer image. If a vibrant 2D film image is about 16 foot-lamberts, many 3D films are shown at less than four. This turned out to be a problem with screenings of Avatar, which in some venues ran at two foot-lamberts. So Cameron is proposing that exhibitors fit their projectors with gear that permits higher frame rates. Shooting and showing at 48 frames per second (or even 60 fps) instead of the traditional 24 will yield a brighter, sharper picture. Interestingly, 3D TV doesn’t have the same problem with light output, so it’s possible, notes Steven Poster of the ASC, that a 3D HD image would have whiter whites and blacker blacks than a 3D film screening.

Moreover, Cameron prepared a demonstration that showed that in 3D, figure movement and camera movement strobe noticeably at the 24fps rate. They look much smoother at 48fps. This is probably true, but I haven’t noticed problems of strobing in 35mm films by Mizoguchi, Jancsó, Welles, Renoir, and other camera-movement masters. Since they didn’t use our modern 3D, they didn’t encounter the artifacts that Cameron and his peers now brood over.

Having pressured exhibitors to go digital and 3D, Cameron is now asking them to change their equipment to permit him to shoot in a new way he likes better—and to compensate for a deficiency in the 3D system he thrust on them. But he assures them that revamping their projectors is merely a matter of “little tweaks . . . tiny things that make it better.” He has claimed it’s a matter of a software upgrade.

This holds good, evidently, only for the projectors made since January 2010, the so-called “second” series. Projectors made earlier may need replacing. Moreover, one report suggests that the projectors using the Texas Instruments system, the dominant technology in the field, will require not only new software but a new media block. Christie, a major projector manufacturer, says that it will have these available in June for $10,000 apiece.

You have to give Cameron credit for chutzpah. Once more he trots out the argument that theatres have to leapfrog home viewing:

With theatre owners already worried that audiences are abandoning the cinema for the comforts of their home entertainment centers, Cameron argued that exhibitors cannot afford to make the case that “What you’re going to see is special and better than what you have in your home, except the motion sucks.”

The message seems clear. Digital and 3D gave you a competitive advantage for a couple of years, but now it’s time to retool. Those of you who didn’t get 3D along with digital, better start moving, especially if you want Avatar 2 and 3. (Just what Lucas said in 2005 about Star Wars IV 3D, which still awaits us.) And upgrade to 48fps, or even 60. Cameron’s message got support in this year’s NATO convention, when Peter Jackson announced that he’d be trying to induce some theatres to play The Hobbit at 48 fps, the rate at which he’s shooting that 3D production.

Who died and made you King of the World?

I’m left with two observations.

First, there was a time when exhibitors called these directors’ bluff. When Lucas griped that there weren’t enough digital screens for Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of the Sith (2005), John Fithian, president of the National Organization of Theater Owners, replied memorably: “I don’t put projectors in just for Star Wars.”

Now, it seems, the exhibitors are so scared of missing the next blockbuster that the filmmakers can dictate terms. It’s remarkable that these men can do something neither Griffith nor DeMille nor Disney nor any other powerful Hollywood filmmaker of the classic years dared do. They keep asking that the fundamental technology of cinema be changed so we can all watch a couple of their movies for a month or two every few years.

Second, if these guys are so passionately committed to quality, why don’t they make better movies?

For accounts of Cameron’s 3D explorations before Avatar see Christopher Probst, “Future Shock,” American Cinematographer 77, 8 (August 1996), 38-44; Ron Magid, “Digitizing the Third Dimension,” AC 77, 8 (August 1996), 45-50; Jay Holben. “Taking the Plunge,” AC 84, 7 (July 2003), 58-71; and John Calhoun, “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea,” AC 86, 3 (March 2005), 58-69.

According to Cameron, he and Vincent Pace, an expert in underwater cinematography, have been working together since 1988. They began building an HD and 3D system in 1999 and finished their first one in 2000. See the GigaOM interview here. In the same interview Cameron mulls over the prospect of 4K television transmission.

A video showing Cameron’s ideas about digital cinema is available at Filmofilia.

As many have pointed out, higher frame rates were argued long ago for film screenings, notably by Doug Trumbull and Dean Goodhill. (See also Roger Ebert on Goodhill’s Maxivision.) Needless to say, Eastman Kodak enthusiastically supported this initiative, since it would step up film consumption.

This entry is a pendant to the series, Pandora’s Digital Box, which ran on this site earlier this year. That series, reorganized and expanded with new material and arguments, will be available in e-book form later this spring.

Avatar.