You can go home again, and maybe find an old movie

Tuesday | March 11, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

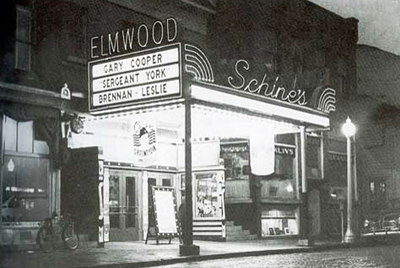

Schine’s Elmwood Theatre, Penn Yan, New York, late 1954-early 1955. Photo courtesy Yates County History Center.

DB here:

Nowadays when a theatre closes or goes digital, it says farewell by screening The Last Picture Show. That hadn’t yet become a tradition when the Elmwood Theatre of Penn Yan, New York presented Bogdanovich’s movie on its final day in November 1972.

Six people showed up.

The Elmwood had been going downhill for years. “I think the theatre building is an eyesore,” declared the chairman of the town’s Urban Renewal Agency. Once part of the powerful Schine circuit, the theatre had been acquired in the mid-1960s by the Rochester-based Panther chain, later renamed Countrywide. That firm seems to have specialized in low-budget genres and X-rated fare. In Penn Yan, the UR officer declared, most of the Elmwood’s programs were rated “restricted,” adding: “Yet it is claimed by some that it is a recreational facility for our children.” Disney films were screened at the Elmwood during those years, but local moviegoer Robert Brainard noted: “They were getting all the junk and nobody was going, not even the kids.”

When the theatre was finally closed, it stood vacant. Vandals broke the windows, and pigeons roosted inside. It had come a long way from the 1940s.

In 1974, two businessmen paid $11,000 for the building and turned it into a racquet club. That business operated for some years, but in 2003 the entire structure was demolished and a new village hall was built on the site.

By then a small three-screen mall cinema had set up business elsewhere in town. I report on a visit here.

In January, I was back in Penn Yan and naturally I sniffed around. Thanks to John H. Potter and Lisa M. Harper of the Yates County History Center, and my sisters Diane and Darlene, I came away with some precious information about the theatre I attended for the first eighteen years of my life.

I also came away with an extremely rare film.

Broadway Melodies and Cherry Blossom Queens

Captain Harry Morse ran steamboat trips on Lake Keuka. He was a legendary figure. Some said that as a boy he had caught a lake trout on his nose. (I know: How could you do that? Supposedly he bent over the side of a boat and a trout leaped up and glommed on.) More prosaically, Morse invested in Penn Yan movie houses, and in 1920 he bought the Shearman House Hotel, a popular stopover for visiting vaudevillians. Morse turned the Shearman House into a theatre.

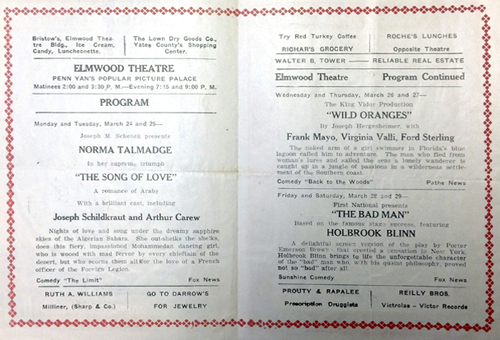

The Elmwood Theatre opened in 1921. It held at least 700 people. That’s pretty big for a town of 4500 people, but as the county seat and a business center, Penn Yan brought in farm families. Many shows were accompanied by printed programs listing coming attractions and carrying advertisements for local businesses. This one, for Song of Love, is from 1923.

Admission was typically 11 cents for matinees and 17 cents for evenings. “Specials” like Chaplin’s The Kid boosted ticket prices to 17 and 28 cents. In 1936 the Schine chain acquired the house.

The Elmwood benefited from the projection expertise of Nathaniel P. “Nat” Sackett. Nat had begun his film career in 1908 at another local movie house, vocalizing with the song slides shown between reels. He became a projectionist before joining the Elmwood in 1923. He stayed on for several decades. According to Nat, The Broadway Melody was the first sound film the Elmwood played. During World War II, he worried that too many theatres were running triple features. If the fad continued, production couldn’t keep up. For Penn Yan, one feature was good enough—especially if it was something like How Green Was My Valley or Captains of the Clouds.

A small-town movie house often became a community center. Elmwood patrons remember talent shows and holiday parties, with gifts and contests before the screenings. In 1940 a housewife attending I Love You Again could join an hour-long cooking class (with prizes) just before the show. Young women would be named Apple Blossom Queen or Cherry Blossom Queen. Halloween screenings included costume contests and of course sudden blackouts and scary sound effects. During the war, with no television or Internet, people flocked to the theatre for newsreels. Customers were steered in and out by ushers; the Elmwood employed them well into the 1950s.

“Today,” remembered Nancy Gillette, “most people cannot imagine a theatre as large as the Elmwood, which included a large balcony, being full most of the time.” By the 1930s, admission prices had come down a bit for children. Ten cents admitted Nancy to the Saturday marathon matinees: “Gene Autry, Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Charlie Chan, the newsreel and one or two cartoons—WOW!” Lines of kids stretched down the block. In the 1950s, Diane and I were among them, watching the same cowboy heroes, along with Tarzan and Martin and Lewis.

Romances and marriages were forged at the Elmwood. In 1933, a young man taking tickets let a young woman slip out to retrieve the keys she left in her car. Over the next few days he began to drive by her house. Her cousin knew the young man and said, “Margaret, I am taking you out when Sam comes along, and I’ll stop his car and introduce you to him.” After two years of dating, Margaret and Sam married and eventually had three children. The Elmwood manager gave Sam’s mother and Margaret free passes.

Local kids like Sam found good work at the theatre. Being an usher got you free movies and a chance to flirt with the concession girls and those who came “solo.” After movies there was pizza at the Den below the theatre. But among the ushers’ tasks was the very onerous one of changing the marquee. Jerry Nissen remembered:

First you had to do layout on paper what the marquee was to say. Then, working from the last letter in the last row, fill a heavy wooden box until you get to the first letter of the first row. The solid metal letters were stored in the basement and you hauled them up to the street. Now imagine, if you will, climbing a rickety old step ladder in the rain or snow and taking down the old message and then letter by letter placing the new message on the two-sided marquee. Brrrr, it used to get very cold. Also on occasion we were the targets of some nice vocal comments and snowballs coming from the T & C Tavern across the street.

DIY movies, 1915

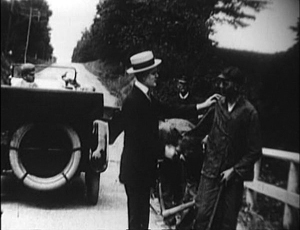

Wheat and Tares (Penn Yan Film Corporation, 1915).

Penn Yan had theatres before the Elmwood went up. In the ‘00s and ‘10s Nat Sackett sang at Theatorum and another theatre, both owned by the Wickham brothers. For a time Nat took over ownership of them. Before Captain Morse built the Elmwood, he was showing movies at the old Sampson legitimate theatre, as well as in the Cornwell, located above a department store. The town apparently had four screens in 1911.

With so many films playing within a couple of blocks, it’s perhaps not surprising that a local businessman decided to make one of his own.

Edward R. Ramsey owned a local paper mill and a factory that manufactured electrical cable. The story goes that when Ramsey observed that Hollywood, California was buying a great deal of his cable, he decided to try moviemaking. Ramsey sold his cable plant and started the Penn Yan Film Corporation.

After making some shorts, Ramsey tied his first feature production to a fund-raising effort by Keuka College. The college’s aim was to provide advanced education to rural students who couldn’t to go to a big university. Ramsey’s film would demonstrate the virtues of going to college. All the talent was local, including the cameraman, who was Ramsey’s brother. From outside, Broadway actor and occasional film director George E. LeSoir was recruited to direct the show.

Shot in the summer of 1915, Wheat and Tares traces the story of two young men. Both Jim Watson and Will Beggs read dime novels, but Jim is encouraged by Alice Corwin, daughter of a Penn Yan businessman, to improve himself. Uplifted by literature, Jim leaves the farm for Keuka College. There he learns enough to become an auto salesman. At the same time, Will (who stuck to pulp fiction) falls in with a gang of layabouts and petty crooks. Their fates converge when Jim discovers oil. A crooked realtor hires Will to put Jim out of action long enough for the site option to expire. But Alice renews the option, and Jim’s family becomes rich. Meanwhile, Will’s life of crime catches up with him, and he is sentenced to a prison road gang. Jim and Alice, now married and with a child, stop when they see Will on the road. Jim vows to help his old friend go straight.

Despite its opening-night success at the Sampson playhouse, Wheat and Tares didn’t have legs. Keuka College closed in fall 1915 and didn’t reopen until 1921. Ed Ramsey died in an auto accident in June 1916. The film may have gotten no distribution outside the region. Stored in the Ramsey home, it was discovered decades later when the house was prepared for demolition. The film was transferred to safety stock and eventually to DVD. That’s the version I have seen.

In the moralizing manner of its day, the full title, Wheat and Tares: A Story of Two Boys who Tackle Life on Diverging Lines, contrasts the life paths of its two protagonists. A tare is a form of weed that infects a field of healthy wheat. Tares in their early stages look very much like wheat, so the metaphor implies that one must wait to see if a young man will turn out well or not. (The Biblical reference is a parable by Jesus, at Matthew 13: 34-35.)

The surviving copy of Wheat and Tares has lost its opening reel. What remains is a fairly ordinary 1915 film. The parallel stories of Jim and Will aren’t developed in tandem; we lose Will for most of the film. A great deal of the second reel is occupied with rich boys hazing Jim at college, which does teach him the manly art of self-defense, but to no special point: he doesn’t get to use his boxing skills later. Another undeveloped plot line involves a movie company filming in the vicinity.

Theme and plot don’t match very well. If you are trying to convince people that going to college will better them, why show your hero succeeding by stumbling onto an oil gusher? Jim would have been just as likely to find oil if he had stayed a sodbuster. The climax is particularly feeble: While Jim is recovering from the beating given him by Will and another thug, it’s Alice who saves the day. She does this not through extraordinary courage or sacrifice, but simply by having her father write a check that renews the option. The realtor, a very passive villain, does nothing, underhanded or otherwise, to block her maneuver.

Stylistically, you can hardly expect The Birth of a Nation, The Cheat, or Regeneration from this tiny Finger Lakes company. In most respects, the film resembles standard films of the period. Some filmmakers were exploiting the sort of crosscutting popularized by Griffith, but Ramsey and Le Soir take almost no advantage of it. There’s no fast cutting to pick up the pace. Most scenes are played in single shots, with close-ups used only to emphasize details, such as a deck of cards, that can’t be easily seen in the master framing. The closest shots of the principals occur during a phone conversation–again, a convention of the period.

Nor does the film exploit the sort of complicated staging we find in tableau cinema. There is one rather well-handled crowd shot, as well as a smooth track-in and-out when Will recruits a one-eyed thug to help him ambush Jim. Simple camera movements like this were by 1915 considered a fairly normal option.

There is an ambitious matte effect when Jim and his college chum Phil visit the movies, but even this fairly common device is somewhat bungled when the boys’ bodies become ghostly by crossing into the matte area.

Although Wheat and Tares exemplifies ordinary cinema of that day, like most films of the first great era of cinema it’s a pleasure to watch. Shooting on location yields spontaneous beauties. At one point Jim rides home on the trolley. In a film utterly lacking in calculated lighting effects, we get a lovely image. Not only do we see the town and wagons pass through windows, but after Will and his partner jump aboard, accidents of backlighting turn them into sinister shapes.

Trolley shots are among the glories of 1910s cinema; I don’t think I’ve ever seen a bad one.

Penn Yan must have been gorgeous then, with the main streets lined with elms.

The trees were felled by Dutch elm disease and other factors, I’m told.

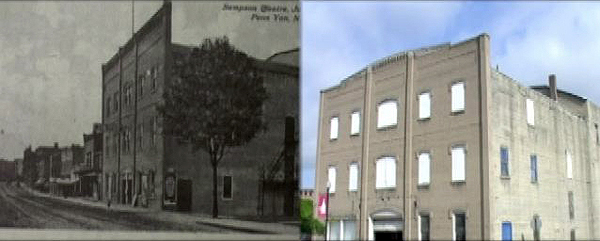

As with any film shot in surroundings that you know, part of the fun comes in spotting familiar locales. John Creamer’s introduction juxtaposes some town landmarks. Here’s the Sampson Theatre, then and now.

Two locations that my sisters discovered pop up late in the film. For a chase, the camera was set up just around the corner from Ramsey’s house.

Ramsey’s house was demolished to add a building and a parking lot to the local hospital, but from that vantage point, we found the source of another shot. The camera was apparently set up in front of Ramsey’s home to frame Jim and Alice and their child in their chauffeur-driven Maxwell. The sidewalk in the foreground is gone, but the background area, including the fire hydrant, has stayed surprisingly constant.

And whatever the faults of Wheat and Tares, watching it gives you a glimpse of the entrance to Captain Morse’s Sampson Theatre (below). In the summer of 1915, Charlie Chaplin had sauntered into my home town. The show starts on the sidewalk, as they used to say.

I’m grateful to John and Lisa of the Yates County History Center for all their suggestions, for access to their files, and for the exterior photo up top and the shot of the Elmwood interior. You can read the local newspaper’s announcement of the Wheat and Tares premiere, with a teaser synopsis, here. Thanks also, of course, to Darlene and Diane. The picture of Penn Yan’s town hall was supplied by Darlene, whose photography site is here.

A DVD copy of Wheat and Tares is available for $15 from the Yates County History Center. You can email Lisa M. Harper, ycghs at yatespastdotorg, or call (315) 536-7318. Credit cards accepted.

The indispensable guide to the theatres in this region is Norman O. Keim’s Our Movie Houses: A History of Film and Cinematic Innovation in Central New York (University of Syracuse Press, 2008). You can read about the Schine chain there, or here.

Wheat and Tares is a prime example of an orphan film. Dan Streible of NYU is a moving force behind retrieving and restoring these elusive items, and a new Orphan Film Symposium is coming up in Amsterdam.

Wheat and Tares (1915). The sign on Charlie’s crotch reads” “Meet Me at the Sampson Program.”