Archive for September 2012

The wayward charms of Cinerama

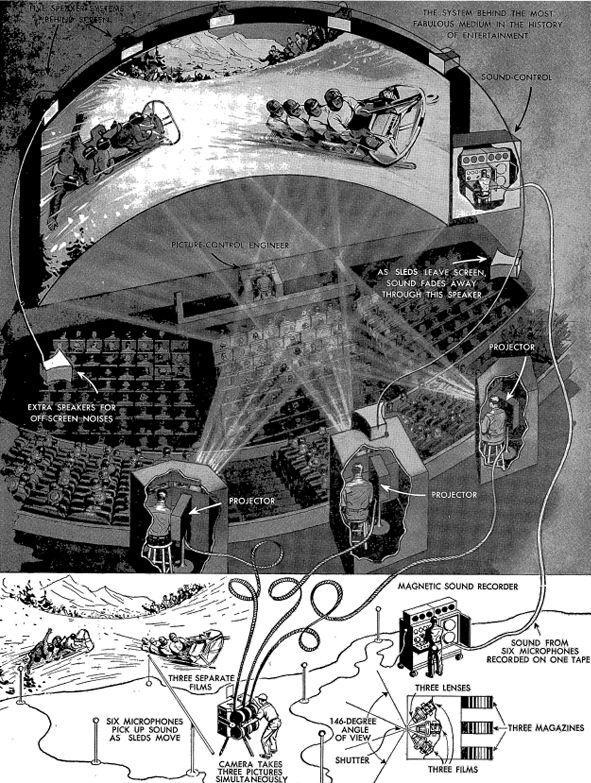

From Cinerama Holiday souvenir book, 1955.

DB here:

Two slumbering potential giants stirred in the last months of 1952, and as 1953 got underway the motion picture industry was faced with the greatest upheaval since sound films revolutionized the industry nearly 26 years ago.

Winfield Andrus, “3-D Finding Its Place,” The 1953 Film Daily Yearbook (New York 1953), 147.

Andrus was referring to 3D and to Cinerama, two technical marvels that promised to revive American filmgoing in the postwar era. In the short term, that didn’t happen. 3D died quickly, and Cinerama remained a novelty before expiring in 1962. But eventually 3D became viable, as the last decade has shown. Moreover, Cinerama’s impact was felt throughout the 1950s. Studios competed with it by introducing other widescreen formats, stereophonic sound, and extravagant roadshow productions. Cinerama, people are starting to point out, was a prototype of what Imax has become. Just as we’re now more interested in classic 3D (see my entry on the reissued Dial M for Murder), we ought to take another look at Cinerama in its more or less pure state.

Devoted aficionados like John Harvey of the New Neon Cinema in Dayton have kept Cinerama alive in theatres, and the challenge has been taken up by other venues. One of the most passionate advocates has been David Frohmaier, whose documentary Cinerama Adventure graced our Wisconsin Film Festival some years back. That documentary showed up on the 2008 DVD release of How the West Was Won, and it’s an essential, affectionate introduction to this most ungainly of film formats.

Now Frohmaier has brought us the 1952 film that started it all. This Is Cinerama has just been released by Flicker Alley, one of our most exacting and adventurous DVD publishers. The whole meticulous package–the film itself, presented in Frohmaier’s Smilebox display, along with an abundance of extras—offers a good chance to think about what Cinerama amounted to.

Cinerama had its ups and downs over a decade. Control of the technology and the venues shifted unpredictably, as did the revenues and profits. But I think that Cinerama’s unique accomplishment lies partly in its unintended consequences. Seeking to become the most realistic form of cinema yet known, Cinerama demonstrates how enjoyably un-realistic, even surrealistic, movies can be.

One hell of a demo

When This Is Cinerama opened at the Broadway Theatre in Manhattan on 30 September 1952, it presented itself as the ultimate package of new entertainment technologies. It was of course in color, which was still something of a rarity in motion pictures. It used stereophonic sound, with five speakers behind the screen and two in the auditorium. The screen itself was a wonder: it was seventy-five feet wide and about 23 feet high, bent in a 146-degree arc. That made the display span fifty feet. Later, some screens would be nearly a hundred feet long and over thirty feet high.

All who saw the film felt that this was an immersive experience. The goal, claimed Cinerama’s inventor Fred Waller, was to approximate what our eyes take in, including peripheral vision. Indeed, Waller claimed that our sense of depth in the world and an image depended on peripheral information. Anyone who has been in a wraparound theme-park attraction can attest to the fact that an image stretching to the edges of sight can provide a pretty compelling illusion, especially if the images carry us forward. You can undergo this illusion in Disney’s Circle-Vision 360°.

Cinerama’s colossal screen size and deep curve dictated a new approach to image-making. No standard 35mm frame could fill such a wide display without losing resolution. The scale of the show demanded three projectors, each trained on one-third of the screen. The image became a triptych, with thin overlaps or “blend lines” demarcating the panels. Naturally, all three had to be exactly aligned and kept in strict synchronization. If one film reel lost frames through a mishap, for future shows projectionists snipped the corresponding frames out of the other two reels.

The projectors were initially housed in separate booths, with a projectionist in charge of each. A fourth booth was given to the sound mixer (off to the right side in the above diagram), who oversaw the multiple track playback at each performance. Yet another staff member was in charge of monitoring the whole performance. Interestingly, the projectors were said to be placed level with the screen, in order to avoid any keystoning distortions of the display. But the diagram above, along with the Cinerama displays I’ve seen, position the projectors fairly high in the auditorium.

The image looked something like the still on the right. Even in this tiny image you can see slight differences between the panels and vignetting along the joins. Projectionists had to ensure that the three panels yielded comparable illumination and color temperature. Each projector’s gate had a little gadget known as a “jiggolo” that ran rapidly along the edges of the frame to blur the blend lines.

The image looked something like the still on the right. Even in this tiny image you can see slight differences between the panels and vignetting along the joins. Projectionists had to ensure that the three panels yielded comparable illumination and color temperature. Each projector’s gate had a little gadget known as a “jiggolo” that ran rapidly along the edges of the frame to blur the blend lines.

To gain resolution, each frame on the film strip used about twice the image area of conventional film. Surprisingly, the image area wasn’t much wider than normal film but it was 1 1/2 times the normal height (that is, 6 perforations high rather than the usual 4). To allow more frame space, the soundtrack was played on a separate magnetic film reel. The resulting images yielded very high resolution.

These sprawling images came from three cameras interlocked into a single bulky unit. The lenses were angled at 48 degrees to one another, turned inward to cross at a precise focal point. The camera lenses, all purpose-made, had a focal length of 27mm–another factor that would yield some striking pictorial effects. All three lenses shared a common shutter and had interlocked diaphragms to ensure comparable exposure. Because flicker would be disturbing on such a wide display, particularly on the edge panels, the film ran at 26 frames per second rather than the usual 24. The aspect ratio varied between 2.6:1 and 2.77:1.

This Is Cinerama was what we’d today call a demo. Lowell Thomas, one of the backers of the process, noted that if they’d told a story with actors, the emphasis would be taken off Cinerama itself, which was “a major event in the history of entertainment.” “The logical thing,” Thomas remarked, “was to make Cinerama the hero.”

The result was a travelogue (a word Thomas hated). After Thomas’ prologue, the film proper opens with the famous ride on a plunging rollercoaster. Then come episodes devoted to the canals of Venice, some church choral music, Scottish pipers, Viennese boy choristers, Spanish dancers, and an excerpt from Aida performed at La Scala. During the intermission Thomas inserts another demo, this time of the surround-sound effects. (We have to remember that stereophonic sound was a big novelty at that point; stereo LPs came later.) The bulk of the second part is spent at the Cypress Gardens leisure park, providing images of handsome men and women at play and climaxing in some exciting water-skiing. This is sort of double product placement–not only promoting the park but also water skis, another Fred Waller invention. The film ends with an awe-inspiring flight crisscrossing America, from New York and the Pentagon to the Golden Gate Bridge, and back to the rugged terrain of the West and Southwest.

In an essay for Cahiers du cinéma, the late Chris Marker pointed out that the film amounts to a religious-popular spectacle. For all the globe-trotting of the first part, the last half is a paean to the splendor that is the postwar USA. The last word spoken, or rather sung, in the film is “America.” Indeed, as many have pointed out, the word Cinerama is an anagram for American. I’ve sometimes wondered about the logo, that peculiarly zigzagged string of letters. It suggests a crumpled snippet of film, with squarish frames like our vertical panels, and its bumpiness evokes the ups and downs of a roller coaster. But there’s no mistaking the logo’s recurring color scheme of red, white, and blue.

In an essay for Cahiers du cinéma, the late Chris Marker pointed out that the film amounts to a religious-popular spectacle. For all the globe-trotting of the first part, the last half is a paean to the splendor that is the postwar USA. The last word spoken, or rather sung, in the film is “America.” Indeed, as many have pointed out, the word Cinerama is an anagram for American. I’ve sometimes wondered about the logo, that peculiarly zigzagged string of letters. It suggests a crumpled snippet of film, with squarish frames like our vertical panels, and its bumpiness evokes the ups and downs of a roller coaster. But there’s no mistaking the logo’s recurring color scheme of red, white, and blue.

Party like it’s 1952

As a novelty, This Is Cinerama succeeded, running for over two years in New York. The system was installed in big-city theatres around the country. At a time when the average price of a movie ticket was $.46, the high-end seats for a Cinerama feature cost $2.80, or $24.34 in today’s currency. The Cinerama organization produced four more episodic travel-centered pictures: Cinerama Holiday (1955), The Seven Wonders of the World (1956), Search for Paradise (1957), and Cinerama South Sea Adventure (1958). Another picture made in a rival three-panel technology, Windjammer (1958), wound up in Cinerama venues as well. By 1957, Variety announced, the first three releases had grossed $60 million worldwide.

The problem was that on those grosses, profits came to only $6 million. Eighty percent of the box office take was used up in operation of the theatres.Morever, the complexity and cost of a Cinerama system meant that very few venues existed; by 1959, there were about twenty screens in the US and another eight or ten abroad, and not all were operating. In addition, overall US movie attendance was dropping, from about 47 million weekly in 1954 to 32 million in 1959.

New management succeeded in opening many more Cinerama theatres on a franchise basis, but the company needed fresh product as well. A coproduction deal was struck with MGM to use the process on fictional features. The results were The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962) and How the West Was Won (London premiere, 1962; US release, 1963). To expand the audience, these films were also released in anamorphic widescreen to non-Cinerama venues.

Both films won large audiences, but they failed to make a profit. Soon the company’s theatres began exhibiting 70mm film releases under the Cinerama brand. The films were shown on curved screens, but with single-lens projection. The first of these releases was It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963); eventually even 2001: A Space Odyssey (1967) would be exhibited in “Cinerama.” In the course of these years, the company was acquired by Pacific Theatres, where it still resides. Classic triptych Cinerama was gone.

I never saw it in its prime.

I did see How the West in its original anamorphic release, and that has stayed with me for a couple of reasons. First, I was moved by it. It’s kitsch in many ways, but there are several exciting and touching scenes. Moreover, even as a squeaky-voiced teen I recognized something genuinely weird about the way it looked. Its imagery haunted me, though I didn’t have ways to understand them. Many years later, writing portions of a book that became The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I couldn’t watch any of the Cinerama travelogues in archives. I had to content myself with watching pink, cropped 16mm anamorphic copies of How the West Was Won. In all, it was very hard to get a sense of what the thing looked like (let alone sounded like).

Not until 2003 did I see both This Is Cinerama and How the West Was Won in the three-panel format, during a conference on widescreen cinema held at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England. That experience was wonderful, and it left me wanting to study the films more closely.

Now I can, and you can too. David Strohmaier has devised a transformation that captures the shape of a Cinerama projection. He calls it the Smilebox. The Flicker Alley DVD of This Is Cinerama is in Smilebox, as you see from my Venetian image above. Warner Bros’ 2008 Blu-ray release of How the West Was Won provides both a Smilebox version and a wider-than-CinemaScope letterbox version.

Through painstaking restoration by Greg Kimble and others, the films look clean and bright. Digital cleanup has regularized the color values from panel to panel and nearly eliminated the blend lines. The result conforms to what the makers would surely have preferred–a greater sense of uniform tonality, light, and space across the frame than surviving Cinerama images have.

For anybody interested in the history of American cinema, the Flicker Alley DVD is essential. It provides a long-missing chapter in the development of widescreen filmmaking. This Is Cinerama is a documentary that is also a document of postwar American pride, of film technology, and of the movie business. But I think it represents even more. For the most part neither Smilebox nor digital restoration has removed the peculiarities that, perhaps perversely, fascinate me about this unique format.

Nice big image you got here. Be a shame if anything happened to it.

Cinerama camera in a mock covered wagon for How the West Was Won.

Like any picture-making process, Cinerama captures the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. Unusually in the history of cinema, it does it with a semicircular array of cameras. The images from those cameras are projected on a corresponding semicircular surface, in the hope that they will simulate not only the spatial layout in front of those three lenses but also the way the world looks to us.

Fred Waller thought that his invention provided greater realism, because our vision subtends a horizontal arc wider than that of conventional camera lenses. Fred fell a few degrees short, though. Claiming that we take in about 160 degrees, he thought that 146 degrees was a good approximation, but our visual field is actually a bit wider than 180 degrees. (Without turning our head, we can roll our eyes.) More important, though, is the assumption that a faithful image of the world should try to capture the curvature of the image as it passes through the cornea to the retina. We see a bowed world, many have claimed, so our pictures should present the way things look.

Yet there’s a difference between visual sensation and visual perception. Even if the light from the world hits our photoreceptors in a partial or distorted way, what we see is regular and unified. On our retinas, near things loom large and distant things look tiny, but we’ve evolved to adjust to the distortions in early stages of vision and see things in normal size. A person ten feet away is twice as large on our retina as somebody twenty feet off, but that’s not the way they look. We don’t see our retinal image, any more than we see the wildly misshapen image of the world projected to brain areas. The eye is a part of the brain, and the brain reworks the stimulus–cleans it, enhances it, corrects it, straightens it out, and gives it a stability that isn’t there in the raw input.

For the most part, normal camera lenses approximate the way the world looks to us after our brain has processed visual signals. Most images show straight-edged walls and sidewalks, railroad tracks meeting at the horizon, proportional human beings. When Cinerama or other nonstandard image-making technologies present distortions to our eyes, we take them for what they are: not “what we really see” but rather pictorial displays creating distinct effects of their own.

Hence the irregular appeals of Cinerama. Suppose we’re not interested in seeing the world as it registers on our sensory system. Suppose we’re interested in exploring uncommon pictorial effects. If we suppose all that, we can have the sort of fun watching Cinerama that we get from this 1877 picture by Caillebotte (Paris Street, Rainy Day), a virtuoso reworking of geometric space.

Take image sharpness. In the 2003 Bradford shows, I was overwhelmed by just how precisely distant objects registered. This was partly due to the greater resolution of a bigger image area, partly to the use of wide-angle lenses with breathtaking depth of field in brilliant sunlight. I can’t illustrate some of the most dazzling effects here, including the sight of a very distant bathing beauty racing through a crowd and up to the foreground in the Cypress Garden sequence of This Is Cinerama. But if you have a large home theatre monitor or projected display, you might be able to spot her. Here I’ll just mention how the farthest stretches of the famous roller-coaster stand out crisply, and in big-screen projection, the people in the far distance do too.

Such short-focal-length lenses distort the visual field in predictable ways. For one thing, they make horizontal lines bow upward or downward. For this reason, Cinerama DPs were at pains to keep the horizon near the center of the shot and to avoid or cover contours parallel to the horizon. Linus Rawling’s canoe oar bends disconcertingly in the central panel even before it hits the blend line and shoots off on its own.

Verticals can get distorted as well. On the edges of each panel, human figures can look bulged, pinched, or oddly torqued.

Cinerama’s triptych format complicates perspective effects by welding three wide-angle images together. When presenting built environments, often each panel displays its own distinct vanishing point–sometimes central, sometimes angular, sometimes both. The results recall the Caillebotte picture, all acute angles and avenues flung out to left and right.

One cinematographer tells us that “special sets had to be built with curves and bends to rectify the false perspective inherent in three-camera systems.” But often we get contorted interiors. Dr. Caligari might feel at home in Lowell Thomas’ office.

The blend lines add their own constraints. From a distance, the Golden Gate looks very planar, but as our plane swoops nearer, the horizon remains flat while the bridge develops a couple of kinks.

For staged action, veteran cinematographer William Daniels warned that “We invariably consider the blend lines first, then plot and stage the action to suit the camera setup.” Most obviously, directors had to keep people away from the panel joins. We can see the unfortunate result in this image from This Is Cinerama. The gent on the far right is at once pinched and bulged, and the building in the B and C panels gets the Caillebotte treatment. Worse, a young Venetian man’s head on the blend line undergoes an unfortunate warping.

When a figure moves from panel to panel, the wide-angle distortions combine with the panel edges to create a faceted, almost cubistic space. Here’s the first anomaly I spotted when watching How the West Was Won as a kid in 1963.

As Linus is walking toward Mr. Prescott, James Stewart seems to stride diagonally forward a bit (in the A panel). After he pivots, he grows very large as he starts to walk straight (the B panel). , then stride diagonally into depth (the third panel). Each wide-angle lens makes people swell or shrink as they come to or from the camera, and with the creases supplied by the blend lines, scenes like this become attractively odd. With the panels ironed out, we see people taking strangely roundabout paths to one another.

The effect is even more noticeable in big action scenes, when horizontal movements that are really parallel seem to peel off from one another. During the Indian chase, the wagons are fleeing alongside one another, as a back-projection shows. But the more dynamic angle on the wagon teams creates an image that hits you like a cold shower.

To the audience in front of a curved screen, the movement in the second shot would have looked somewhat (but not entirely, I think) more linear. For us, we see a perspective we’ve never seen before, with wagons diverging from one another but neither getting smaller or larger. And how about the dizzy swerve that the pathway in panel C takes when it reappears in panel A?

The angled-triptych format obliged actors to adjust their performances in counterintuitive ways. “An actor in a side panel,” wrote Daniels, “cannot look directly at one in the center panel when speaking to him, but must cheat a little–direct his eyes a little behind the one in the center.” Here’s an example from The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm that stands out when seen in the flat format. Wilhelm is speaking to Greta from the C panel, but it seems that Laurence Harvey didn’t cheat his body quite enough. He seems to be speaking past her, an effect not helped by the disproportionate size of his body.

This Is Cinerama is obsessed with centering its action, but sometimes the center seems strangely off-kilter. With the water-skiing women shown earlier, the three cameras create a sort of hollow viewing station. Why do the flanking skiiers seem to be moving at angles to the central trio? Why do the ropes of the central skiiers fly off (jaggedly) to one side, rather than expand directly towards us, like train tracks?

As with the wagon teams, you have to imagine diagonal actions as rotated inward to parallel one another during projection. What you see is not what you’d get in the theatre. But also, what you see is something you’ve never seen in a movie before.

Most of these effects are heightened by the inability of the three-eyed monster to record close-ups. Because of the short focal length, the camera unit sat very near the actors: for a shot from the waist up, the central lens was between one-and-a-half and three feet away. Putting the camera so close necessitated lights being attached to the camera unit. But normally close-ups were avoided, so the human figures never dominate their locales. These movies are, more than most, about space–however buckled and bizarre that space might be.

Because of the panels, panning shots were to be avoided, but certain kinds of camera movement forward were welcomed. The signature Cinerama shot is the shot plunging toward the vanishing point–a boat rushing through the water, an aerial view banking toward the horizon. Even though the blend lines made shapes and edges wrinkle, this gigantic, embracing image streaming toward viewers gave a compelling illusion that they were hurtling forward.

The distortions are less visible from a perfect vantage point in a Cinerama auditorium–presumably, as close as you can get. Distortions on the display edges would be minimized by peripheral vision, which isn’t good at registering detail. Presumably some of the curvilinear shapes, like Linus’ oar, and those kinks across the blend lines, would be less egregious if viewed straight on. Watching from the front row in Bradford, I recall seeing these distortions, but they didn’t seem as vivid.

Naturally, not everybody in the auditorium has a perfect vantage point. In the original screenings, people who had sat on the sides complained that movement on the nearest flanking panel seemed to flow upward. Smilebox, which respects the overall geometry of the display, still yields disparities. Linus’ oar still curves, though not as pronouncedly.

My images here, and yours on your home screen, are unavoidably mapping a curved display onto a flat surface, so there will still be anomalies. If you want to try cutting down on them, sit close to the Smilebox display. I prefer to sit back and enjoy their weirdness.

They’re features, not bugs

What about the films themselves? Arguably no great film was made in the format, but all the releases probably have some admirers. I want to end by talking about the two I find most appealing.

Cinerama’s travelogues were episodic, designed to show off features of the process in different filming situations. The two fiction features had to highlight the process and tell a coherent, engaging story. They too tend toward the episodic, but they handle that option in different ways. And stylistically, both work against the official “rules” of the new format.

The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, an entertaining family film, employs a frame story. The brothers are assigned to write the family history of the local Duke. Jacob, an expert linguist, does his job dutifully, but Wilhelm plays hooky to find and write up fairy tales he hears. His zeal to collect stories leads to the loss of their commissioned manuscript, and he falls ill, during which several fairy-tale characters come to visit him. Eventually Jacob is honored by the Royal Academy, but it’s Wilhelm who gets enduring glory by being swarmed over by hordes of children anxious to hear his latest tale. Within this overarching plot, three of the stories are enacted using various special effects, including puppet animation. Some of these shots appear to have been shot in a non-Cinerama format and “paneled” afterward.)

It’s tempting to ascribe the frame story’s direction to Hollywood veteran Henry Levin and the embedded fantasies to co-director George Pal. To the connoisseur of Cinerama, those fantasy passages offer some delights. If anybody told Pal about the rules for shooting in the format, he ignored them. The fairy tales give us whirling camera movements, bumpy subjective shots, and frequent assaults on the audience in the manner of 3D. During a wild coach ride, the coachman hurls himself to and from the camera. Later, a knight’s bumbling servant slays a dragon in lunging close-up.

You can even take certain passages as sly parodies of the brand. The Woodsman in the first tale has hitched a ride on the back of the coach, and he stoops to look underneath. Cut to his point-of-view: an upside-down version of a signature Cinerama shot.

Whoever directed the frame story scenes, however, was fairly bold too, moving his actors in zigzag patterns more flamboyant than the blocking of How the West Was Won. And instead of the small, high sets recommended for the format, Wonderful World shoots in throne rooms and palace salons that seem to stretch on forever. In smaller sets, like the brothers’ cottage, their friend’s bookshop, and especially the lair of a witch, the compositions take advantage of crannies and oddly angled planes that enhance the exaggerated distances.

As in German Expressionist cinema, the distortions seem to suit an atmosphere of fantasy. There’s even a massive violation of one of the basic rules of Cinerama: avoid tilting the camera. High and low angles were likely to exaggerate any distortions in the panels. Yet Levin, or Pal, or both occasionally throw in expressive angles, most strikingly a low angle showing Wilhelm’s family and friends ascending to his sickroom.

The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm solves the problem of the episode film by giving us a frame story. How the West Was Won solves it by a more threaded structure. A family saga creates branching stories that show three generations of kin participating in the winning of the frontier. The story acknowledges, briefly, the conquest of indigenous peoples–the “liberal Westerns” of the 1950s haven’t been ignored–but slavery doesn’t play a significant role. This is a story of white people.

The Prescott clan sets out on the Erie Canal, but on the rivers all but two of them lose their lives. The warm, slightly romantic Eve settles with the trapper Linus Rawlings on a farm in Ohio, while her sister Lilith ventures west. Eve’s son Zeb joins the Union forces in Civil War and later moves west with the railroad, eventually becoming a marshall. Lilith joins a wagon train, takes up with a gambler, inherits a worthless mine in California, and reunites with her lover on a riverboat. They become entrepreneurs investing in the railroad system. Near the end of the century, Lilith loses her fortune and joins Zeb, now retired, and his wife and children. But before they can settle down on Lilith’s inherited Arizona ranch, Zeb has to settle a score with a bandit who intends to rob a train. The film falls into sections specified in the credits–The Rivers, The Plains, and so on–but not in the film, though the parts usually end with fades.

Marker might note that How the West Was Won revives the piety and chauvinism on display in This Is Cinerama. The Prescott women found a kind of holy family, bound, as one song puts it, “for the Promised Land.” Some writers thumb through the phone book to get names for their characters, but screenwriter James R. Webb seems to have favored the Old Testament. Eve, living up to the positive side of her name, becomes the first woman of the new land. In forcing Linus to become a farmer, she helps turn the wilderness into a garden. Lilith, whose name associates her with sexuality and demonic possession, becomes a dance-hall girl and eventually a millionairess, but she has no children. At the end she returns to her nephew, Zebulon, named for her father; in the Old Testament he is the founder of a tribe. And Zeb has named his daughter Eve. The family abides in an endless cycle, its members replacing one another and its history intertwined with the full flowering of the United States.

The film ends with the sort of God’s-eye views that conclude This Is Cinerama, but emphasizing the modern West, with its dams, roads, cities, even whorls of traffic. Interestingly, in the place of the forward rush of the earlier film, these aerial shots pull us backward, the classic mark of the end of a story. But the finale of the epilogue carries us forward once more, under the Golden Gate Bridge and into a sunburst over the Pacific. Since women have played a central role, no surprise that the final lyrics of the choral accompaniment celebrate heroes as “every mother’s son.” This country has reached its natural limit; beyond is heaven, and the chorus tells us, here at last is the Promised Land.

Most scenes are handled briskly, but with little nuance beyond what the actors bring to the story. The spectacle remains appealing, the music infectious, and the imagery always impressive–especially when it’s a little whacked out, as in my examples above and many other scenes of the film. Like The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, this has shown that Cinerama can be edited rapidly. This Is Cinerama has only a little more than two hundred shots, but Wonderful World has a thousand, and How the West Was Won has over eleven hundred. The chapters of the latter yield some striking results: most average between eight and nine seconds, but John Ford’s Civil War segment averages nearly fifteen seconds, while the climactic Outlaws segment averages about five seconds.

That climactic sequence, directed like most of the film, by Henry Hathaway, makes splendid and varied use of the format. Despite a heavy reliance on back projection and several shots that seem not to have been made in the three-camera process, this monumental remake of The Great Train Robbery is a showcase for how Cinerama could create exciting action through staging and editing. To the advantages of Cinerama–forward drive, looming landscapes, and immersive sound–Hathaway and editor Harold Kress add percussive cuts of logs sliding this way and that, along with painful stunts, including one showing a man flung off a train and into a cactus.

By contrast, the Civil War sequence shows how a director can triumph over an inflexible format by relying on expressive stasis. Ford the pictorialist will carve striking compositions out of the constraints of Cinerama. He exploits the depth of the 27mm lenses, sometimes stationing all his figures in the central zone, as if he’s trying to preserve the 1.37 aspect ratio. At other moments he confines the action to a single flanking panel.

Sometimes Ford simply ignores the triptych format in order to split the frame in half or, say, two-fifths. He also gives his actors postures, props, and gestures that allow them to underplay. With Ford, even fresh-minted junior stars like Carroll Baker and George Peppard can give performances of gravity.

Ford’s creative choices stand out most strongly in two scenes set on the farm. In the first, Linus Rawlings has gone off to battle, and his son Zeb is itching to follow. Eve, now old, accepts with weary sadness that he will have his way. There’s a Griffithian two shot of Eve and Zeb on the porch, her arms dangling wearily and her right hand rising and falling as she asks Zeb about whether he’ll get a uniform. The hell with Cinerama, Pappy seems to say: Just fill up half the frame with the cabin to keep us fastened on the couple.

After a quick embrace, Eve dashes into the house. A porch shot that is virtually a Fordian doorway framing shows Zeb leaping with joy before he turns, sees something in the house, and halts in his tracks. Ford needn’t show us Eve’s grief. This is the most tactful shot in the whole film.

Soon enough Ford will recall this scene. Zeb has left for the war. Eve, kneeling at the family plot, prays to her father before slipping behind the rail. Her face is hidden, but her hands again express her resignation, and prefigure her death. She was never the same, her other son will say, after Zeb left.

These homestead passages are echoed by a scene at the end of the Civil War segment. Back from the war, Zeb learns of his mother’s death from his brother Jeremiah. The two sit on the porch sharing a dipper of water and recalling their father. Zeb rises to go, they shake hands, and we get another muted Fordian moment. Why move your actors when you can pose them?

Now the old director, a master of depth since the 1910s, bends this newfangled format to his own ends. Zeb leaves the frame, comes back in the far distance, and is finally blocked by the farmhouse, leaving Jeremiah quietly weeping.

That’s how you handle this busy, noisy new contraption, Ford seems to say. Dwell on moments of stillness and pathos. Use handshakes, embraces, a drooping black shawl. Keep the action in a well-defined zone. And treat this as a silent movie.

The most comprehensive account of Cinerama’s development is Thomas Erffmaier’s 1985 Northwestern Ph. D. thesis, The History of Cinerama: A Study of Technological Innovation and Industrial Management. Also invaluable are John Belton’s Widescreen Cinema (Harvard University Press, 1992) and Robert E. Carr and R. M. Hayes’ Wide Screen Movies (McFarland, 1988), usefully supplemented by Daniel J. Sherlock’s emendations here. A good older work is Michael Z. Wysotsky, Wide-Screen Cinema and Stereophonic Sound (Focal Press, 1971). Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale put This Is Cinerama into the context of postwar blockbusters in Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010), Chapter 7. On the Web, restorer and cinematographer Greg Kimble provides a thorough and well-illustrated account of Cinerama at In 70mm.

Chris Marker’s “Le Cinérama” appeared in Cahiers du cinéma no. 27 (October 1953): 34-37.

Cinerama grew out of Fred Waller’s experiments with gunnery-training displays during World War II, as Strohmaier documents in Cinerama Adventure. Waller discusses this work in “Cinerama Goes to War,” New Screen Techniques, ed. Martin Quigley, jr. (Quigley, 1953), 119-126. This collection includes other pieces of value on Cinerama, 3D, CinemaScope, and other new technologies. It would be interesting to know if Waller’s efforts influenced, or were influenced by, psychologist J. J. Gibson’s comparable wartime experiments with aerial training films. Gibson’s ideas about how we grasp space through “optical flow” and centered perspective have obvious parallels with the Cinerama process. Waller was said to have been influenced by another psychologist, Adelbert Ames, Jr., one of the founders of 1950s “New Look” psychology. Waller’s belief that our peripheral vision was more important than stereopsis in determining depth echoes Ames’ hypothesis that convergence and binocular disparity were overrated as depth cues.

Greg Kimble provides a thorough overview of the making of How the West Was Won in a 1983 article for American Cinematographer, available here. I’ve drawn as well on William Daniels’ article “Cinerama Goes Dramatic,” American Cinematographer 43, 1 (January 1962): 28-29, 50-54. Also useful was Darrin Scott, “Panavision’s Progress,” American Cinematographer 41, 5 (May 1960): 302, 304, 320-322, 324. My quotation about readjusted sets comes from Scott’s piece.

Three-panel Cinerama features can be seen occasionally today at the Pictureville Cinema in Bradford, the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles, and the Seattle Cinerama.

Simultaneously with This Is Cinerama, Flicker Alley has published a lavish Smilebox version of Windjammer, also prepared by David Strohmaier. That’s a whole other story.

P.S. 5 October: You never can tell. Jim Emerson forwards me this Indiewire report by Len Maltin on a new short made in three-panel Cinerama.

How the West Was Won.

A Hobbit is chubby, but is he padded?

Kristin here:

On July 14 at this year’s Comic-Con, a thirteen-minute montage of clips from The Hobbit was shown during an appearance by Peter Jackson and cast members of the film. Afterward in press interviews, Jackson unexpectedly hinted that The Hobbit, long announced as being made in two parts to be released in December 2012 and 2013, might be expanded to three parts. This possibility inspired much skepticism among fans and members of the press. And yet only two weeks later, on July 30, it was announced that The Hobbit would indeed be released in three parts, the third to appear in the summer of 2014.

Although some fans of the film of The Lord of the Rings were delighted, there was much speculation in the press that the move was made from sheer greed, milking a third blockbuster from Tolkien’s modest children’s book. There were even some accusations that Jackson had lost his creativity and was seeking to extend his most successful series beyond its logical stopping point.

Yet if one reads the filmmakers’ statements about the decision to make an additional part of The Hobbit, it is clear that they intend to add more plot material rather than stretching the story of the relatively short novel. There is plenty of additional, directly relevant material in Tolkien’s appendices to LOTR. None of it is given in enough detail to make a free-standing film. Still, no doubt the filmmakers and the production studio began to realize that they had the rights to all this material, and that incorporating some of it into The Hobbit was their only chance to use it. Warner Bros. surely was delighted at the prospect of another lucrative blockbuster.

I’m not convinced, however, that Jackson’s team made their decision primarily from considerations of money. For one thing, some of the material from the appendices was created by Tolkien to tie the events of The Hobbit to those of LOTR. The filmmakers could use it for that same purpose. So far, the trailers and images from the forthcoming film seem to me quite promising in terms of how the appendices have been quarried for useful story items.

It happens that for avid fans of Tolkien, this is a special moment. It’s Tolkien Week. Ever since 1978, the week in which September 22 occurs is dedicated to The Professor, as he is respectfully known to devotees. And September 22 is Hobbit Day, because it is the shared birthday of Bilbo Baggins (who turned 111 on the occasion of the Long-Expected Party that opens the book) and his adopted nephew Frodo (who turned 33, the age of adulthood for Hobbits).

Warner Bros. and the filmmakers have shrewdly chosen this week to release the second trailer for The Hobbit (not counting the teaser). It appeared online on September 19, with the best-quality versions on Apple. (A high-quality version of the first trailer can be seen here.) There’s also a site where you can watch the trailer with five alternative endings, all of them humorous. (The Bilbo one is undoubtedly the best, though I enjoyed the Gandalf one as well. The Dwarf ending is actually the same as in the theatrical version.) The first part of The Hobbit is due out on December 14 in the USA and many markets, and on other dates in December elsewhere.

From two parts to three

I have a uniform paperback edition of the two novels where The Hobbit runs 272 pages and The Lord of the Rings, not counting the appendices or Prologue, runs 993 pages. So The Hobbit is less than a third the length of its sequel. The implication would seem to be that in order to be comparable to Jackson’s version of LOTR, its film adaptation should occupy a single part of perhaps three hours.

Of course LOTR, even in its eleven-and-a-half-hour extended DVD versions, left out a great deal of Tolkien’s novel. (Excision was Tolkien’s expressed preference, by the way, for a film adaptation. In a letter disapproving of a 1957 treatment for a proposed film of LOTR, he stated that cutting scenes was far preferable to racing through a complete but compressed version.) Still, given the huge success of the three-part film, it seemed reasonable that Jackson and company would treat The Hobbit more fully, eliminating less and giving fans a more complete version of the earlier book.

But three parts for The Hobbit? Especially when this change was sprung on the public less than six months before the world premiere of the first part (November 28 in Wellington)? The move proved controversial and has been argued and speculated about ever since. Every trailer, every scrap of footage (especially the 13-minutes of clips shown at Comic-Con and still not available to anyone who was not in Hall H on July 14), every photograph has been closely examined for hints of what extra material might be included in an expanded Hobbit.

The reactions have generally been of four types. Keen fans of Jackson’s LOTR are delighted, trusting him and his fellow screenwriters, Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens, to come up with extra material true, if not to the book, at least to the spirit of the first film. Others are more skeptical, feeling that Jackson’s team is being too ambitious and is trying to stretch the book’s contents too far. After all, it was written as a children’s novel, not an epic romance like LOTR. A third group simply accuses Jackson of opportunism, whether his own or mandated by greedy corporate types at Warner Bros. (parent company of production unit New Line). Finally, a few commentators view the move as evidence of artistic “stagnation” on Jackson’s part

Most prominent among those in the fourth camp is James Russell, who wrote a piece baldly entitled “Peter Jackson’s three Hobbit films suggest he is running on empty,” for The Guardian. He argues that Jackson had never had a commercial success before LOTR, and that his post-LOTR films have been neither as lucrative nor as critically praised. Now, Russell suggests, Jackson has returned to familiar territory, despite having initially hired Guillermo del Toro to do the directing honors:

It’s hard to see how making The Hobbit could be seen as a positive step for Jackson. However, splitting the story into three separate films takes the moribund self-absorption of the project to entirely new levels. It looks as if Jackson is running entirely on empty, pushing this side project to ridiculous extremes because he has nothing else to offer.

(See also IndieWire‘s “An Open Letter to Peter Jackson on Splitting The Hobbit into Three Movies.”)

Jackson inadvertently encouraged such an interpretation back in the early days of pre-production, when del Toro was still the designated director. He said that he had visited Middle-earth once and did not want to compete with himself. Even when del Toro exited the project in late May, 2010, Jackson said he would not step into the job unless no one else could be found and the project was in danger of falling apart. Asked when the production process would move forward, he responded: “I just don’t know now until we get a new director. The key thing is that we don’t intend to shut the project down…We don’t intend to let this affect the progress. Everybody, including the studio, wants to see things carry on as per normal. The idea is to make it as smooth a transition as we can.”

The announcement that Jackson would in fact direct The Hobbit was not made until mid-October, and his statement in the press release was notably bland: “Exploring Tolkien’s Middle-earth goes way beyond a normal film-making experience. It’s an all-immersive journey into a very special place of imagination, beauty and drama. We’re looking forward to re-entering this wondrous world with Gandalf and Bilbo – and our friends at New Line Cinema, Warner Brothers and MGM.” Nevertheless, he has assured the public that once he agreed to direct, his immersion in pre-production re-ignited his enthusiasm for working with Tolkien’s material. Judging by the two trailers, as well as the eight video production diary entries so far posted on Jackson’s FaceBook page, that enthusiasm is genuine. The expansion of the film to three parts is another indicator that he has been inspired by his return to Middle-earth.

Not padding but extension

Major spoilers ahead! Page and chapter numbers from the two novels are from the most definitive versions of the texts: for The Hobbit, Douglas Anderson’s The Annotated Hobbit, second edition, and the 50th anniversary single-volume edition of LOTR, edited by Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull.

The widespread assumption since the announcement of the three-part Hobbit has been that Jackson and his fellow screenwriters would simply stretch out the action of the book. Yet that is clearly not what the trio is up to. In the press release, Jackson sounded much more enthusiastic:

Upon recently viewing a cut of the first film, and a chunk of the second, Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens and I were very pleased with the way the story was coming together. We recognized that the richness of the story of The Hobbit, as well as some of the related material in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings, gave rise to a simple question: do we tell more of the tale? And the answer from our perspective as filmmakers and fans was an unreserved ‘yes.’ We know the strength of our cast and of the characters they have brought to life. We know creatively how compelling and engaging the story can be and—lastly, and most importantly—we know how much of the tale of Bilbo Baggins, the Dwarves of Erebor, the rise of the Necromancer, and the Battle of Dol Guldur would remain untold if we did not fully realize this complex and wonderful adventure.

There is a great deal of material in the appendices of LOTR relating to the plot of The Hobbit, though in many cases that material involves characters and events barely referred to in the novel. In the book, Gandalf departs from the Dwarves and Bilbo midway through, going off, as he later reveals briefly “to a great council of the white wizards, masters of lore and good magic; and that they had at last driven the Necromancer from his dark hold in the south of Mirkwood” (p. 357). All this was later fleshed out, partly in the body of LOTR and partly in its appendices: the council became The White Council, which included Elves like Galadriel and Elrond; the Necromancer gained a name, Sauron; his “dark hold” became his secondary dark tower, Dol Guldur.

As is quite clear from the trailers and from statements by the filmmakers, action involving the White Council and the attack on Dol Guldur will figure prominently in The Hobbit. Already an image of the White Council, including Saruman and apparently taking place at Rivendell, has surfaced in one of the licensed tie-in books:

This may not, however, be the White Council meeting that occurs during the action of The Hobbit. It may be a flashback to the one in Third Age 2851, described in the invaluable chronology of Appendix B:

2850 Gandalf again enters Dol Guldur, and discovers that its master is indeed Sauron, who is gathering all the Rings and seeking for news of the One, and of Isildur’s Heir. He finds Thráin and receives the key of Erebor. Thráin dies in Dol Goldur.

2851 The White Council meets. Gandalf urges an attack on Dol Guldur. Saruman overrules him. (p. 1088)

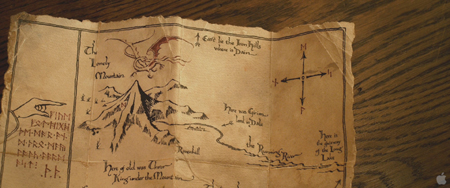

An image of Dol Guldur appears in the second trailer:

Saruman opposes the attack on Dol Guldur because he has secretly begun to search for the One Ring, desiring it for himself. Thráin gives Gandalf not only the key of Erebor but a map of it. That’s the map Gandalf looks at in Bag End just after his arrival in The Fellowship of the Ring. He will give the map and key to Thorin Oakenshield, son of Thráin and leader of the Dwarven troop in The Hobbit. Both will be crucial in the plot. The map also appears in the second trailer:

Tolkien wrote the appendices in 1954-55, vainly hoping to include them in the third volume of the novel. (They were incorporated into a later edition.) They retrospectively fill in events of the Third Age that led up to the plot of LOTR. He did not go back and extensively revise The Hobbit to incorporate these events, though he did a bit of fiddling with the original version in order to bring it more in line with LOTR. One cannot help but suspect that Tolkien wished he could have dealt with all these events in more than outline form. I for one am intrigued to see these bits of plot, sketched out by Tolkien in such a tantalizing way, fleshed out by the filmmakers.

No doubt that, as with LOTR, I will not agree with all the choices the screenwriters make in doing so. Still, we already have evidence that they can be adept in incorporating material from the appendices into the plot. They already did so to a more limited extent in LOTR. The scene in the extended DVD version of The Fellowship of the Ring of Aragorn visiting the grave of his mother, Gilraen, at Rivendell is derived from “Here Follows a Part of the Tale of Aragorn and Arwen,” a section of Appendix A (pp. 1057-1063). Tolkien considered this tale the most important part of the appendices, insisting that if foreign translations had to cut them, they should at least retain the narrative of the Aragorn-Arwen romance. The scene at Gilraen’s grave, brief though it is, adds depth to Aragorn’s character and to his relationship with his foster father, Elrond.

This moving story is also the source of the scene in The Two Towers where Elrond tries to persuade Arwen to leave Middle-earth for the Undying Lands by predicting her life with Aragorn. The dramatization of the prediction is a literal flashforward, for in the book Aragorn’s death eventually leads Arwen to regret her decision to remain with him, and she wanders, embittered and alone, in Lothlórien for a year before her own death (a period depicted by a single shot in the film). This flashforward is a powerful scene, and the film is all the better for its inclusion. We should not leap to the assumption that Jackson, Walsh, and Boyens will falter in their attempts to draw material from the appendices into The Hobbit.

There has been much fan speculation that the longer version of The Hobbit will include flashbacks to more of the Dwarves’ history. A scene might show the dragon Smaug driving the Dwarves from their ancestral home in the Lonely Mountain and assembling the hoard on which he lies when they return to retake the mountain. It might include their move into exile in the Blue Mountains west of the Shire. All of this could also be linked to Moria. Balin, whose tomb the Fellowship members discover in the Mines of Moria in The Fellowship of the Ring, is a character in The Hobbit, the eldest of the Dwarves. Between the action of The Hobbit and that of LOTR, he leads a troop of Dwarves to Moria to try and recapture it from the orcs that had conquered it generations earlier.

Tolkien wrote a brief history of the Dwarves and Khazad-dûm (Moria) in “Durin’s Folk,” another section of Appendix A. This includes an entire scene with dialogue, depicting Thráin’s father Thrór’s suicidal attempt to re-enter Moria; he is killed by the orc Azog. Although not crucial for the Quest of Erebor plot of The Hobbit, a flashback to such a scene would link it to the Moria passage of LOTR. There is a causal connection as well. Before departing for Moria, Thrór gives Thráin the last of the seven Dwarven rings, which leads Sauron to capture and imprison Thráin in Dol Guldur, taking the ring from him; that is why Gandalf later finds him in Sauron’s dungeons.

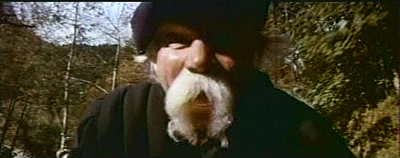

Such scenes might or might not be used, but the filmmakers have definitely decided to include Radagast the Brown, the third wizard, who is only mentioned in The Hobbit. (He appears in one scene in the LOTR novel, but he was eliminated from the film.) Radagast plays a limited role in Tolkien’s Legendarium, having apparently “gone rustic” and become absorbed with the birds and animals of Mirkwood, largely abandoning his part in trying to defeat Sauron. Still, his inclusion in the film seems a positive thing, as some charming shots of him playing with hedgehogs in the second trailer suggests:

The decision to divide The Hobbit into three parts presumably came too late to permit numerous changes in the first part. Nonetheless, the point at which the first film was planned to end has apparently been changed dramatically. The film’s official site posted an interactive wallpaper generator that showed a panoramic scroll summarizing the film’s scenes, from Gandalf scratching a rune on Bilbo’s door to the moment when the Dwarves and Bilbo escape from Thranduil’s dungeons in barrels floating down a river. That scene happens well over halfway through the novel. Once the three-part release was announced, the wallpaper generator was changed to its current version, which ends with the episode of Gandalf, the Dwarves, and Bilbo trapped up burning fir trees by wargs and goblins. Two shots from that episode are the latest events shown in the new trailer and would seem to provide a good cliff-hanger for the ending:

This episode happens in Chapter 6 of the book’s 19 chapters, while the barrels scene is in Chapter 9. This shift suggests that a considerable chunk of action has been added to the first film. That action probably derives from the LOTR appendices rather than some stretching of episodes from The Hobbit.

Perhaps to reassure fans, most of the new trailer shows scenes very familiar from the book: the Dwarves arriving unexpectedly at Bag End, the three trolls preparing to cook Bilbo (above), and of course the beginning of the famous riddling contest between Bilbo and Gollum. Two shots of Bilbo’s awestruck reaction to being in Rivendell (at the top) capture the spirit of the book perfectly. After all, Bilbo ended up living in Rivendell during his declining years, and while there he translated the ancient Elvish texts that became The Silmarillion. All this suggests that the bulk of the material derived from the appendices will appear in the second and third parts.

As a long-time Tolkien fan, I would be as disappointed as anyone if the decision to divide The Hobbit into three parts were done merely by stretching out the plot of the novel. All the evidence, however, points to a careful incorporation of bits of Tolkien’s own text to fill out the background of the tale and to link it more firmly to LOTR. Essentially it sounds as though the screenwriters have sought and probably found a way to incorporate the original “bridge” film, announced long ago when The Hobbit adaptation was first revealed in the press, into The Hobbit.

The bridge film was to have been a sequel to The Hobbit, which at that time was planned as a single film. It would fill in the events between the end of The Hobbit and the beginning of LOTR–a gap of sixty years in the novels. It apparently was to have been made up primarily of scraps of plot garnered from the appendices. Whether the writers would have been able to come up with an overall structure to unite those scraps is debatable. Using the strong spine of The Hobbit‘s plot to support them seems a promising solution to the problem.

Perhaps I will be disappointed upon seeing the film, but all the evidence so far indicates that the writers have been inventive and careful in expanding the project. Moreover, the trailers suggest that the technology used to create Gollum and to manipulate the sizes of the actors has improved since LOTR, as the frame below indicates.

Happy Hobbit Day to all!

For Tolkien’s thoughts on cutting versus compression for adaptations of his films, see The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, p. 261.

TIFF: More than movies

Audiences gather for screenings at the Bell Lightbox, hub of the Toronto International Film Festival.

DB here:

Around midnight tonight, the crowds packing the Toronto International Film Festival will disperse, leaving the city full of memories of another extraordinary year. I’ve been back in Madison for this last week, but my few days at TIFF remain on my mind. This is partly because along with the films came a lot of ideas, opinions, and information. At any festival, fraternizing with audiences, critics, and programmers is one fine way to get that stimulation. It happened after some of the Wavelengths section’s short-film programs. Here are Raymond Phatanavirangoon and Bob Koehler outside the Art Gallery of Toronto, where their Devo retro-stylings raised our conversation to a new level.

More structured sessions delivered too. Out of my 4-plus days at the Toronto International Film Festival, I set aside about one and a half for industry panels and filmmaker Q & A’s. Let me tell you a little of what I learned.

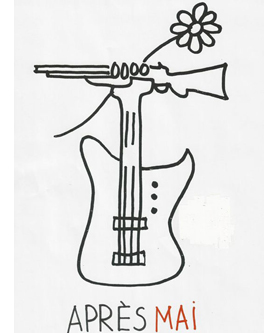

From Assayas to Asia

TIFF: Where programmers meet stardom.

The talkfests I attended shed light on both film artistry and film business-making. Central to the first area was the master class with Olivier Assayas, hosted by Brad Deane.

Assayas, a charming fellow, talked fluently about how Something in the Air (discussed here) bears traces of his youth. During the 1970s, high-school kids were “footsoldiers of the cultural war of the time.” He recalled his affinities with the artistic side of the counterculture, as opposed to the extremes of the political activists, some of whom, being aligned with Maoism, refused to recognize the Cultural Revolution as “disaster on a demented level.” Yet this shouldn’t be taken as apolitical aestheticism; Assayas has been a vigorous advocate for the work of Situationist Guy Debord.

Assayas was refreshingly detailed about his working methods. He writes only one draft of his screenplay, partly because he wants to protect the “digressive” aspects of his story. (This tendency is apparent, and enjoyable, in Something in the Air.) Since his films are difficult to classify within standard genres, he needs to cobble together creative financing for each project. But the script becomes obsolete when he casts the film and visits locations. By embodying the characters, the actors create beings “more powerful than what I’ve written.” Working with them, he refuses to supply background on the characters’ psychology. “I look to them to understand the characters.” This hands-off approach yields striking results in the new film, where nearly all the cast is non-professional.

Assayas was refreshingly detailed about his working methods. He writes only one draft of his screenplay, partly because he wants to protect the “digressive” aspects of his story. (This tendency is apparent, and enjoyable, in Something in the Air.) Since his films are difficult to classify within standard genres, he needs to cobble together creative financing for each project. But the script becomes obsolete when he casts the film and visits locations. By embodying the characters, the actors create beings “more powerful than what I’ve written.” Working with them, he refuses to supply background on the characters’ psychology. “I look to them to understand the characters.” This hands-off approach yields striking results in the new film, where nearly all the cast is non-professional.

Assayas doesn’t undertake elaborate rehearsals, instead coming to the set each morning and describing the shots they’ll make. He wants to take account of the evolution of the film as it’s been developing. He doesn’t fully block the shots. He sketches each one in longish takes that, as the actors expand on the action, “add layers” to what he’d initially planned. Alternatively, he cuts up the long takes and combines pieces of them. For Something in the Air, he relied on stable and wide framings, partly in reaction to trends toward handheld shots and close-ups, partly because he used the crane to create a “floating,” more lyrical circulation through the space.

Artistry, mixed with business sense, was apparent in one of the panels at the Asian Film Summit’s day of meetings. Colin Geddes hosted a session on Asian genre cinema, and several producers and directors shared thoughts on action cinema as an international genre. Fanboy blood pulsed high.

Artistry, mixed with business sense, was apparent in one of the panels at the Asian Film Summit’s day of meetings. Colin Geddes hosted a session on Asian genre cinema, and several producers and directors shared thoughts on action cinema as an international genre. Fanboy blood pulsed high.

Eli Roth (left), another kid who grew up with Kung-Fu Theatre on TV, was bowled over years later by Korean and Japanese thrillers like Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. Now Roth is producer and co-writer of The Man with the Iron Fist, directed by RZA–who is, according to Roth, letter-perfect on his kung-fu film knowledge. “We wanted to do a movie like we saw as kids on Saturday afternoon.” But production values in the genre have swollen since the old days. The project is using the Hengtian studio’s vast replica of the Forbidden City. RZA, Roth says, expected The Last Emperor to be a kung-fu movie, so this is his attempt to make things right.

Tom Quinn, Co-President of the Weinstein Company’s RADiUS division, had similar affinities. As he pointed out, East Asian countries have strong local markets and so can build a base in genre cinema. With quantity comes quality. While working at Goldwyn and Magnolia, Quinn handled US distribution for The Host, Pulse, Tears of the Black Tiger, and most recently 13 Assassins, along with many other titles. Ong-Bak, on view at TIFF in 2004, was a particular triumph for him, yielding over a million dollars in its first weekend of release and eventually garnering $4.5 million in the US. Even the heavy piracy of Ong-Bak Quinn takes as a positive sign, “a validation of the film’s value.”

Bill Kong, a legendary Hong Kong producer and a force behind Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, along with Stephen Fung, director of Tai Chi 0 (above), filled out the panel. Overall, the discussion ranged widely, but one question kept cropping up. Why is it that Western films are widely popular in Asia, but Asian cinema is almost completely a niche market in the West? I didn’t hear a clear answer (though I’d start an answer with Western racial prejudice).

Kong noted that Asian filmmakers don’t have high expectations about penetrating the US market, but other panelists were more hopeful about crossover projects. Quinn pointed out that the festival circuit built an audience, and Roth thinks that Tarantino has been a major player in making Asian film more popular, especially with the Kill Bill duet. The fact that Russell Crowe plays a major part in The Man with the Iron Fist suggests that things may be changing.

Bigger than Bollywood

Mira Nair.

The East/West dynamic was also the focus of two other panels. “India: Lessons from Bollywood and the Independents” brought together a nearly all-female group of experts to discuss local financing and wider distribution. All were agreed that it was necessary to convince the world that Indian cinema was bigger than Bollywood. As director Dibakar Banarjee put it: “We need to open the third eye.”

The local industry has a certain comfortable inertia. A film might cost only $150,000, but it can collect 90% of its production costs upon its opening run, said Shailja Gupta, who has been both a director and production executive. Foreign distribution is a major risk at this budget level. So how does a project, particularly an independent film, get international traction?

Coproductions are an obvious path, and while they are still rare, the trend is emerging. The Indian government’s National Film Development Corporation Ltd. has helped with coproductions since 2006, says Nina Lath Gupta, NDFC Managing Director. Such enterprises are rare and mostly involve France or Germany. By establishing the Film Bazaar in 2007, the NDFC acknowledged the importance of marketing as well as financing, and this is getting local filmmakers acquainted with the need to think more globally.

Another path to the overseas market was suggested by Guneet Monga (right). She is a producer on the network narrative Peddlers and the two-part gangster saga Gangs of Wasseypur; both earned very good buzz at TIFF. Monga pointed out that sales agents can help shape projects for international distribution.Working with Elle Driver, she was able to generate three versions of Gangs, targeted for different regions. Moreover, sales agents can help a film by avoiding the old practice of selling it as a single package. Instead, the agent can pre-sell it with a minimum guarantee and negotiate territorial rights further down the line.

Another path to the overseas market was suggested by Guneet Monga (right). She is a producer on the network narrative Peddlers and the two-part gangster saga Gangs of Wasseypur; both earned very good buzz at TIFF. Monga pointed out that sales agents can help shape projects for international distribution.Working with Elle Driver, she was able to generate three versions of Gangs, targeted for different regions. Moreover, sales agents can help a film by avoiding the old practice of selling it as a single package. Instead, the agent can pre-sell it with a minimum guarantee and negotiate territorial rights further down the line.

Mira Nair, distinguished director of Salaam Bombay and Monsoon Wedding, has long enjoyed worldwide exposure, of course. She shared her thoughts on how filmmakers could follow their visions and still, as she put it, “put bums on seats.” That’s accomplished by not worrying about distribution but devoting energies to creative choices–such as she undertook in The Reluctant Fundamentalist, her first foray into the thriller genre.

During the India panel, moderator Meenakshi Shedde asked if China might become a coproduction partner for local films. This is currently not happening, but the question reflects the significance of the People’s Republic on the global film scene. Earlier in the day, a panel on “Financing Between Asia and the West,” moderated by Patrick Frater, concentrated mostly on China as the leading edge of the region. Once more, the question of coproductions was central.

“Coproduction is a reality now for global filmmaking,” declared Peter Shiao, CEO of Orb Media Group. But the power of China in the new media landscape has created a false optimism among Western entrepreneurs. Shiao warned newcomers that coproductions can’t be fulfilled in good faith with perfunctory gestures, such as including a Chinese actor in a secondary role. (The Expendables 2 was mentioned in this connection.) Aspiring filmmakers need to grasp and follow the China Coproduction Film Office regulations straightforwardly.

Solid coproductions are rare, agreed Bruno Wu, founder and chair of many top Chinese media groups. He pointed out that what works in China won’t necessarily work in the rest of the world, but what works in the rest of the world is likely to work in China. So the Chinese investor needs to look at projects that will play internationally. He gave as examples his firms’ deals with Justin Lin and John Woo, who have reliably won global audiences. Along similar lines, Stuart Ford, founder and CEO of IM Global, suggested that a good alternative to coproduction involves soliciting equity investment from China for Western films. For example, Chinese investors in Paranoia, a $40 million production, acquired mainland distribution rights as part of the deal.

The soundness of investing in Western films seems borne out by local box-office figures. Seventy percent of China’s market receipts come from English-language imports; the several hundred domestic films produced earn only twenty percent. And theatrical receipts provide, according to Peter Shiao, ninety percent of a film’s earnings. Windows in the Western sense don’t exist, and there’s no legitimate home video market. Gradually local filmmakers are experimenting with Western ancillary tactics; Painted Skin: The Resurrection recently tried out apps and games.

China-based Video on Demand is more promising. In a few years, Wu expects there to be several million addressable HD cable homes, and providing entertainment on demand might provide a way around the national quota system for film import. There is no quota restraining VOD distribution, and as it takes hold, it might reduce piracy.

A killer app? (as in killing off business?)

Jonathan Sehring and Winnie Lau at the VOD panel at TIFF, 9 September 2012.

Speaking of VOD, in early September I signed up. I did it partly because there was one title I needed to see immediately: Keanu Reeves’ Side by Side, the documentary about the digital vs. film controversy. More abstractly, I had been learning a little about VOD when I recast and expanded my blogs on digital exhibition for Pandora’s Digital Box, and I was curious about how VOD worked in practice.

After a period of turmoil, the US film industry has integrated VOD into its system of non-theatrical ancillaries. Before, we had DVD and Blu-ray, both rental and retail, along with movie channels like HBO and Sundance available on subscription cable. Eventually movies would show up on basic-cable channels. There was also “pay per view” via cable, a one-off transaction now known as Pay TV VOD.

Now, the internet has expanded the options.

*Electronic Sell-Through (EST) allows the consumer to download a film and own it. This service is available through iTunes, Amazon, and other outlets.

*iVOD (internet VOD) is a one-off rental, to be run immediately or within a specified time period. To check the 1.77 aspect ratio on Dial M for Murder, I rented it for 24 hours on iTunes.

*Subscription VOD (SVOD), which you get with Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and other providers. This option provides a library of titles available at any time for a monthly fee. SVOD is comparable to cable-television subscriptions, and it’s becoming very popular, as all-you-can-eat options tend to be.

In addition, another option hovers over the business:

*Premium VOD (PVOD) consists of a one-off rental available sooner than the traditional home-video window. The transmission would be via cable or satellite, not the Net, and the price point has typically been $30 for one viewing. The studios tried out PVOD with DirecTV in 2011, with apparently unencouraging results. Worse, last year’s Tower Heist fracas, during which Universal planned to put the film on PVOD 30 days after theatrical release, triggered threats of boycotts from exhibitors. PVOD, however, is likely to reappear at some point because it can offset losses from the declining DVD market.

No surprise, then, that one industry panel was called “VOD Killed the DVD Star.” The session assembled major players in that domain to discuss the present situation and the prospects for the future.

Much of the panel’s time was devoted to explaining why filmmakers needed to be flexible about accepting VOD as a legitimate complement to or substitute for theatrical release. VOD, they insisted, shouldn’t be seen as a dumping ground for weak or narrow-interest films. The reason: The consumer is king, and consumers want everything on demand.

Winnie Lau, Executive Vice-President for Sales and Acquisitions at Fortissimo, said that companies now recognized that consumers should be able to see a film on whatever platform they want. Given the high costs of a theatrical release, that option isn’t justifiable for many films. Philip Knatchbull, CEO of Curzon Artificial Eye, put the case more strongly, declaring that with the consumer in control, notions like windows and “on demand” are losing their usefulness. His view suits a company that, like IFC, has integrated video and theatrical distribution with theatre ownership and HD delivery. There are, he suggested, only home cinema and public cinema, and everyone in the film value chain should be aiming to reach millions of screens.

Tom Quinn of RADiUS was working for Magnolia when in 2005 Mark Cuban experimented with a multiple-platform release of Bubble. “His vision,” Quinn recalled, “was to make films available whenever people liked.” The Bubble experiment was problematic because it came out on film and on DVD simultaneously, but Quinn said that “the hotel VOD numbers were through the roof.” This summer, after twelve months of preparation, RADiUS has issued its first VOD titles, and Bachelorette, released earlier in September, won notice for earning about half a million dollars in its first weekend.

The prototype of longer-term VOD success is the later career of Edward Burns. Burns, who had his first success with the breakout indie movie The Brothers McMullen (1995), was lively and articulate. “VOD helped me stay in business.” He knew firsthand the slow rollout that characterized 35mm platform release in the 1990s, along with the months of press tours. In the years that followed, he realized that his movies–basically, as he put it, people bullshitting with one another around a kitchen table–had shrinking theatrical prospects. In 2007, he offered Purple Violets exclusively on iTunes. This came around the time that IFC and Magnolia were experimenting with day-and-date releasing on different platforms.

The prototype of longer-term VOD success is the later career of Edward Burns. Burns, who had his first success with the breakout indie movie The Brothers McMullen (1995), was lively and articulate. “VOD helped me stay in business.” He knew firsthand the slow rollout that characterized 35mm platform release in the 1990s, along with the months of press tours. In the years that followed, he realized that his movies–basically, as he put it, people bullshitting with one another around a kitchen table–had shrinking theatrical prospects. In 2007, he offered Purple Violets exclusively on iTunes. This came around the time that IFC and Magnolia were experimenting with day-and-date releasing on different platforms.

Burns was satisfied with the results and built a production model around VOD. The cast and crew work for free and collectively own the film. Budgets can be low; he claimed last year that Newlyweds cost only $100,000. Payments are deferred, and if a film breaks through, everyone makes money. His last three films, he reported, did. He compared the business model to that of an indie band. VOD gets his work to the people who watch HBO, Showtime, AMC. “That’s our audience.”

Burns is an unusual instance, since as one panelist pointed out, he has established his own brand. Still, other VOD releases can break out. The most widely publicized example is Margin Call, with about $4.5 million on VOD. Jonathan Sehring, President of IFC and Sundance Selects, was a pioneer of alternative platforms, and he remarked that 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days did better on VOD than in theatrical release (where it grossed $1.2 million). In a recent interview, Sehring indicates that the recent IFC release About Cherry as doing as well as Bachelorette on VOD and other revenue streams.

It seems, then, that these and other industry decision-makers see VOD as offering two avenues, depending on the film. VOD can provide a new window, to be added before or after or during theatrical release. Alternatively, VOD can replace theatrical, as it has done for Burns (who will still occasionally give a film like the upcoming Fitzgerald Family Christmas brief theatrical play). With this option, many films, both domestic and imported, will never see a theatrical release but they might make money on the less costly VOD platform.

The problem for the second strategy is finding a way to make the film stand out from the thousands of titles available in cable and VOD libraries. A theatrical release provides the “shop window,” as Knatchbull called it, but without that, the film needs other salient features–big stars or cult buzz–to attract the home viewer.

Despite the panel’s title, the guests didn’t predict that VOD would displace discs. In fact a couple of panelists agreed that DVD and Blu-ray would be around quite a while. Quinn (left) confessed that as someone who grew up with VHS he would always be collecting his favorite films on physical media.

There’s something else to consider: some dramatic disparities between VOD and DVD consumption. The differences are spelled out in a recent IHS Screen Digest report.

On one hand, the VOD audience has grown rapidly. The report counted transactions–buying a movie in any form–and came up with striking figures for the world’s top five regions.

2007: DVD retail and rental: 2.7 billion transactions; online VOD in all forms: 14.8 million transactions.

2011: DVD retail and rental: 2.58 billion transactions; online VOD in all forms: 1.4 billion transactions (nearly all SVOD).

The Screen Digest team estimates that 2012 will see an even bigger burst in online VOD, totaling 3.4 billion transactions, with nearly all that via subscription. (I’m in there somewhere.) By contrast, physical media sales and rentals are predicted to fall further, to 2.4 billion transactions.