Archive for the 'Directors: Lang' Category

Quality bingeing

Mon Oncle (1958)

Kristin here:

Or binging, if you prefer. Either is an acceptable spelling.

Streaming entertainment is one of the things that are saving our sanity as we sit in our homes. With the theaters closed and new movies either delayed or sent straight to streaming, movie critics, other journalists, and movie buffs are now making best-films-to-stream-during-the-pandemic lists a new and common genre across the internet.

Maybe you’ve been streaming a lot of TV series, even ones you’ve already seen, and are feeling a bit guilty about that. Maybe you’re longing for something more worthwhile to watch but wishing that that something would take up more time than your average feature film.

For those people, I offer a list of films to binge. These are either long in themselves or are split up into many parts that can be binged just like TV series. Others are stand-alones but can be grouped in meaningful ways.

My experience is that online disc orders are taking longer than usual. With Amazon prioritizing health and work-at-home supplies, Blu-rays are taking around two weeks rather than two days. (David and I, of course, count Blu-rays and streaming as part of our work-at-home requirements.) While you’re waiting, I’ll bet many of you have some of these discs on your shelves already and have always meant to make time for them. That time, lots of it, has arrived.

Serials

Many fine serials were made in the silent era, but Louis Feuillade remains the director that most of us think of first in relation to this format. His three great serials of the 1910s (not including, alas, the fine Tih Minh [1918]) are available on home video.

Fantômas (1912). 5 episodes, 337 minutes. Fantômas is available in Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. David wrote a viewer’s guide to it here.

Les Vampires (1915). 10 episodes, 417 minutes. Les Vampires is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. As far as I can tell, it is streaming only on Kanopy (apart from unwatchable public domain pre-restoration prints).

Judex (1917). 12 episodes, 315 minutes. Judex is ordinarily available from Flicker Alley, though it is currently listed as out of stock. Amazon has 5 left. For maximum bingeing opportunities, watch all three serials in a row and then stretch them out with Georges Franju’s charming remake, Judex (1963) for an extra 98 minutes (it’s $2.99 to stream it on Amazon Prime).

Miss Mend (Boris Barnet, 1926). Three episodes, 235 minutes. The only American-style serial from the Soviet Union that I know of, or at least the only one easily available. I wrote about it briefly when it first came out from Flicker Alley. You can still get it from Flicker Alley or Amazon. We wrote briefly about it here.

Le Maison de mystère (Alexandre Volkoff, 1923). 10 episodes, 383 minutes. I’ve already written in some detail about this long-lost serial. It’s probably not as good as Feuillade’s best, but it’s good fun and beautifully photographed (see top of section) and acted–and long enough to require a meal break. Fans of the great Ivan Mosjoukine (as he spelled his name after emigrating from Russia to France) will especially want to see this one. Available from Flicker Alley

Berlin Alexanderplatz (Rainer Werner Fassbender, 1980) 13 episodes and an epilogue. 15 hours, 31 minutes. Back when it first came out, this was treated more as a film than a TV series. It showed in 16mm at arthouses and archives. David and I drove to Chicago to see the whole thing in batches over a single weekend at The Film Center (now the Gene Siskel Film Center). It’s available on either DVD or Blu-ray as a Criterion Collection set (#411 for you Criterion number-lovers). It’s also streaming on the Channel. Both have a batch of supplements, even the 1931 German film of the novel, so you can stretch the experience out even longer.

Silent serials may work for some families, if the kids have been introduced to silents already through the more obvious route of films with Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and the other great comics of the era. If not, families can fill their time with more recent films in episodes with continuing stories.

The serial format has had a comeback in recent decades, partly due to the influence of the first Star Wars trilogy and partly to the need for ever expanding amounts of moving-image content in the era of home-video, cable, and internet services. For those who want to binge Star Wars, you don’t need my guidance. Anyway, I gave up after the first of the recent series, the one where Adam Driver took over as the villain. (Not that I have anything against Adam Driver. It was the film.) Even daily life in a pandemic is too short for more.

The Harry Potter series. (2001-2011) Eight episodes, 990 minutes, or 16.5 hours. This series is not high art, but it’s pretty good, highly entertaining (to some, at least), and even has one episode, number three, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, HP and the Prisoner of Askaban (above). The others are HP and the Sorcerer’s Stone (or Philosopher’s Stone in the UK and elsewhere; Chris Columbus), HP and the Chamber of Secrets (Chris Columbus), HP and the Goblet of Fire (Mike Newell), HP and the Order of the Phoenix, HP and the Half-Blood Prince, HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, and HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part II (the last four, David Yates). These films are, of course, available in multiple versions, on disc and streaming. As far as I can tell, none of the complete boxed sets have the two last parts in 3D; those have to be purchased separately. Having seen the last film in a theater in 3D, I can say that it doesn’t seem to be one of those films that is much improved if one sees it that way (unlike Mad Max: Fury Road, in the section below).

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings extended editions: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Desolation of Smaug (2013), The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003, above). 6 episodes, 1218 minutes, or 20 hours, 18 min. Yes, for sheer length this serial tops them all. Plus there are lots of supplements. Each part of the Hobbit films has one commentary track and a bunch of making-ofs, adding up to 40 hours, 5 1/2 minutes. This pales, however, in comparison with the LOTR extended editions, which have four commentary tracks, totaling 45 hours, 44 minutes. The making-ofs are hard to get exact figures for, but I estimate about 22 hours for all three films. That’s about 68 hours of audio and visual supplements.

To top that off, the Blu-ray set contains the three feature-length documentaries by Costa Botes: The Fellowship of the Rings: Behind the Scenes, The Two Towers: Behind the Scenes, and The Return of the King: Behind the Scenes, all adding another 5 hours, 2 1/2 minutes. (Botes’s films were also included in a “Limited Edition” reissue of the theatrical versions of the LOTR films in 2006.) In toto, if one watches every single item and listens to all the commentaries, one could escape 133 hours and 10 minutes of isolation boredom–and possibly go mad in the process. But treating the bingeing as an eight-hour-a-day job, it would come to 16 1/2 days.

All this does not include the supplements accompanying the theatrical-version discs. These are charming but more oriented toward introducing complete neophytes to the universe of Middle-earth than toward giving filmmaking information.

Series

Series, as opposed to serials, usually involve continuing characters but self-contained stories. Most of the series below could be watched out of order without suffering much. It would help to watch Mad Max first, since it’s an origin story. The Apu Trilogy should be watched in order because it’s about the central character’s stages of life. Each of the M. Hulot films bears the traces of the contemporary culture in which it is set, but one can understand each fine out of order. I saw Traffic first, in first run, and then saw the others.

Mad Max (1979), Mad Max 2, aka The Road Warrior (1981), Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) add up to 411 minutes, or 6 hours and 51 minutes. You know them, you love them–but have you ever watched them straight through? We’ve written about Fury Road (here and here). That’s a film where the 3D really does play an active role.

Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot films: Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), Mon Oncle (1958, see top), Play Time (1967), and Traffic (1971). They add up to 7 hours and 4 minutes. Or add his non-Hulot films, Jour de fête (1949) and Parade (1974) for just under an additional 3 hours of hilarity. You can buy all of Tati’s films at The Criterion Collection or stream them at The Criterion Channel. Throw in my “Observations on Film Art” segment on Parade for an extra 12 minutes. And check out Malcolm Turvey’s new book, Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism, soon to be discussed in a portmanteau books blog here.

Dr. Mabuse films plus Spione: Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Spione (1928, frame above), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) and The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), adding up to 610 minutes, or 6 hours and 10 minutes. Few if any directors have extended a series over such a stretch of time, and the Mabuse films are quite different from each other (including having different actors play the master criminal). I throw Spione into the mix because the premise and tone are so similar to the first Mabuse film. Haghi is basically Mabuse as a master spy instead of a gambler and general creator of chaos; given that he’s played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, who was the first Mabuse, the comparison is almost inevitable. One can almost imagine Haghi as just another of Mabuse’s disguises and it fits right into the series. I’ve linked the streaming sources to the titles above.

Kino Lorber has the restored version of Der Spieler on DVD and Blu-ray, Eureka has the restored version of Spione on DVD and Blu-ray (note: Region 2 coding) The Criterion Collection offers a DVD of Testament, and Sinister Cinema has a DVD of The 1,000 Eyes. (For those who want to dig deeper, there a Blu-ray set of all of Lang’s silents, from Kino Classics and based on the F. W. Murnau Stiftung restorations. That totals 1894 minutes, or about 31 and a half hours. I don’t know if that counts the supplements, but there are lots of them.)

Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali (“Song of the Little Road,” but nobody calls it that, 1955), Aparajito (1956), and The World of Apu (1959). 341 minutes. Satyajit Ray’s trilogy may seem like a serial, in that it follows the life of the main character, Apu. Yet Ray had not planned a sequel until Pather Panchali achieved international success, and the films have big time gaps in between, with no dangling causes. These are three of the most beautiful, touching films ever made, and the stunning restoration from a damaged negative and other materials is little short of a miracle. If you have never seen these or saw them before the restoration, do yourself a favor and binge them. Have some tissues handy, and I don’t mean for stifling coughs and sneezes. Available on disc from The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Collection here, here, and here.

Now I briefly cede the keyboard to David for his recommendations of Hong Kong series.

Triads vs. cops, Triads vs. Triads

Infernal Affairs (2003).

There are many delightful Hong Kong series. I enjoy the silly Aces Go Places franchise (1982-1989) and the pulse-pounding Once Upon a Time in China saga (1991-1997). Alas, almost none of these installments entries are represented on streaming. I could find only the weakest OUATIC title, Once Upon a Time in China and America (1997) on Amazon Prime, Vudu, and iTunes.

If you want to go for samples, there are two diversions from the ever-lively Fong Sai-yuk series. The Legend (US title of the first entry, a bit pricy from Prime). The more reasonably priced Legend II, the US version of the second entry, has a fantastically funny martial-arts climax featuring Josephine Siao Fong-fong as Jet Li’s mom. This is available from several streamers. Older kids won’t find either one too rough, I think.

There are two outstanding series more suitable for adult bingeing. Infernal Affairs (2003-2004) was made famous by Scorsese’s remake The Departed (2006), but the original is better, and the follow-ups are loopier. The first entry offers solid, suspenseful plotting and meticulous performances by top HK stars Tony Leung Chui-wai and Andy Lau Tak-wah, supported by a rogues’ gallery of unforgettable character actors. Parts two and three spin off variations on the first one, tracing out before-and-after incidents and throwing in some quite strange narrative contortions. The whole thing provides an engrossing five and a half hours of entertainment. Available from several services.

In my book Planet Hong Kong I analyze the trilogy as an example of how directors Andrew Lau and Alan Mak Siu-fai created a more subdued thriller than is usual in their tradition. Bonus material: In the spirit of providing free stuff during the crisis, here in downloadable pdf form is my little chapter on the trilogy: Infernal Affairs interlude.

Also subdued, even subtle, is Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Election (2005) and Election 2 (aka Triad Election, 2006). These films dared to show secret gang rituals that other filmmakers shied away from. The first part plays out ruthless competition among rival Triad leaders, including strikingly unusual methods of punishing one’s adversary. The second entry, even more audacious, suggests that Hong Kong Triad power is intimately tied up with mainland Chinese gangs, backed up by political authority.

Johnnie To’s pictorialism, so feverish in The Longest Nite (1998), A Hero Never Dies (1998), The Mission (1999), and other films, gets a nice workout here as well. Infernal Affairs is agreeably moody, but the Election films are black, black noir.

The pair add up to three hours and a quarter. The first film is apparently available only on disc but the second is streaming from several sources.

Of course, to get into the real Hong Kong at-home experience, some viewers will find all these films easily and cost-free on the Darknet.

Thematic combos

Flicker Alley’s Albatros films. 5 films, 664 minutes, or 11 hours and 4 minutes. I wrote about the DVD set, “French Masterworks: Russian Émigrés in Paris 1923-1929” when it first came out. It’s still available here. The Albatros company made some of the key films of the 1920s, most of which are still too little known, including Ivan Mosjoukine’s Le brasier ardent (1923, above). If this is still a gap in your viewing of French films, here’s a chance to fill it.

Yasujiro Ozu: The Criterion Collection has released a helpful thematic grouping of some of Ozu’s early films. One is “The Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies” (DVD and streaming), including I Was Born, but …, Tokyo Chorus, and Passing Fancy, adding up to 281 minutes. The British Film Institute has gone further along the same lines, releasing “The Gangster Films,” also three silents: Walk Cheerfully (1930), That Night’s Wife (1930), and the wonderful Dragnet Girl (1933); they add up to 259 minutes. The BFI has also put out “The Student Films,” (listed as out of stock at the moment) yet more silents: Ozu’s earliest complete surviving film, Days of Youth (1929), I Flunked, But … (1930), The Lady and the Beard (1931) , and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? (1932), adding up to 251 minutes.

David has recorded an entry on Ozu’s Passing Fancy for our sister series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel; it should go online there sometime this year.

Or watch all the “season” films in a row: Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Early Spring ((1956), Equinox Flower (1958), Late Autumn (1960), End of Summer (1961), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962), for a grand total of 840, or 14 hours. Including An Autumn Afternoon is cheating a bit, since the original title means “The Taste of Mackerel.” Still, it’s so much like the earlier films in equating a season with a stage of life that the English title seems perfect. The early films equate the seasons with the young people, about to marry or recently married, while in the later films, and especially the last three, the seasons refer to the older generation, lending an elegiac tone to the end of Ozu’s career. David has done commentary for the DVD of An Autumn Afternoon.

All of these (except for Days of Youth) and many other Ozu films can be streamed on The Criterion Channel, which also has a bunch of supplements on this master director.

Or just watch The Criterion Channel’s Kurosawa films in chronological order, or Bresson’s or Godard’s or Bergman’s or …

Or watch all of Hideo Miyazaki’s films in chronological order, with or without the company of kids.

Just really long films

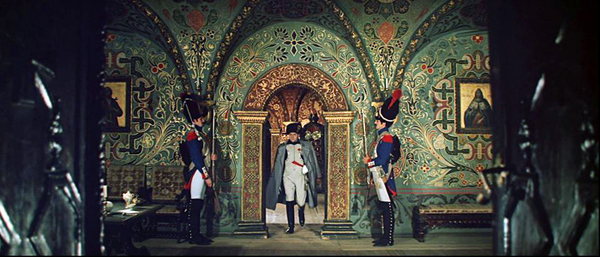

War and Peace (Sergei Bondarchuk, 1965-1967, above) 4 parts: 7 hours, 3 minutes, 44 seconds. I suppose this is technically a serial, since the parts were released over three years. Still, the idea presumably was that it ultimately should be seen as one film, and the running time would permit it being seen in one day fairly easily. I have not seen this restored version, only the considerably cut-down American release back when it first came out. I remember it as being quite conventional, but on a huge scale in terms of design, cinematography, and crowds of extras. Seeing it in its original version would no doubt be impressive (see above). Available on disc at The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Channel. The supplements total 175 minutes and four seconds, pushing the total up to nearly 10 hours.

Satan’s Tango (Béla Tarr, 1994) 450 minutes, or 7 hours 30 minutes. Film at Lincoln Center has just made Tarr’s epic available for streaming; you can rent it for 72 hours and support a fine institution. As to owning it, the DVDs seem to be out of print. There is, however, a Blu-ray coming from Curzon Artificial Eye on April 27 in the UK. Pre-order it here. Obviously many of us will still be stuck inside by the time it arrives. Or if you have it on the shelf and never quite got around to watching it, here’s your chance. Derek Elley’s Variety review sums up its pleasures. Our local Cinematheque has shown it twice, once in 35mm and more recently on DCP (see here, with the news buried at the bottom of the story). David reported on that first showing, and later he wrote a general entry about Tarr’s work on the occasion of having met the man himself.

Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985) 550 minutes, or 9 hours and 10 minutes. The Holocaust examined through modern interviews with a broad range of people involved. Available in a restored version on disc from The Criterion Collection. It does not seem to be available currently for streaming.

Unclassifiable

Then there’s Dau (2020-), a biopic of a Soviet scientist that is perhaps the most ambitious filmmaking venture ever.

Shot on 35mm over three years in a real working town with 400 characters played by actors who remained in character and costume round the clock the whole time. Few have seen these, though two showed at the Berlin festival this year. We haven’t seen them but plan to give it a go, since they have just shown up online. Here’s a helpful summary of the project. At the Dau Cinema website, you can stream the first two films for $3 each: Dau. Natasha (2:17:53) and Dau. Degeneration, (6:09:06) adding up to 8 hours and 27 minutes. Twelve more films are announced for future release, with no timings given. Clearly not suitable for family viewing.

I have not attempted to add up all these timings, but if you can track most of them down, they might get you through much of the isolation period. Stay safe!

Election (2005).

The ten best films of … 1928

La passion de Jeanne d’Arc

Kristin here:

Time for our twelfth annual alternative to the usual list of the ten best films of the current year. Instead, I offer a list from 90 years ago, in part for fun and in part to call attention to some lesser-known classics that are worth discovering. (See here for our lists from 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, and 1927.)

The year 1928 marked the triumphant conclusion of the silent cinema. Very few sound films were made that year, and those that were often included only music, perhaps sound effects, and occasionally some passages of dialogue. Sound was not innovated because the silent cinema was in aesthetic decline. Quite the contrary. It was initially an enhancement that film-industry people assumed would make films more lucrative. In most cases the “talkies” that followed over the next few years were inferior to their silent predecessors, in part due to the limitations of the new sound technology. Those who opposed the addition of sound could point to the films of 1928 as evidence that the young art form had already reached a peak of perfection that was being tarnished by the addition of recorded sound.

In compiling this year’s list, I came up with eight titles that seemed unquestionably to belong on it. There were another six on a list of possibilities for the final two slots. More than in past years, this year gave me a chance to go back and rewatch films I hadn’t seen in a long time, in some cases since graduate school in the 1970s. Some held up well, some not so much. In a few cases, restorations made since my first viewings revealed new strengths in films I remembered from poor prints.

As always, there are films that have been lost but which plausibly could have filled out the list, most notably Ernest Lubitsch’s The Patriot and F. W. Murnau’s 4 Devils.

First, the eight obvious choices, in no particular order apart from #1.

1. La passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

Not every year includes a film that is not only one of the tops of its year but of all cinematic history as well. Carl Theodor Dreyer’s final silent film is one such masterpiece.

Jeanne d’Arc seamlessly blended the stylistic traits of the great artistic film movements of the 1920s, German Expressionism, French Impressionism, and Soviet Montage and made something new and unique of them.

Expressionist designer Hermann Warm’s past credits had included two films that have featured in these lists, Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Fritz Lang’s Die müde Tod. Warm collaborated with French theatrical designer Jean Hugo to create spare, white, off-kilter sets that focus our attention on the spiritual drama. Fast editing conveys subjectivity, as in the scenes where Jeanne is threatened with torture and where the citizens are suppressed when they riot after her execution. Rudolph Maté’s cinematography is startlingly dependent on close shots, particularly on the face of Jeanne, played by Renée Falconetti in one of the most intense and affecting performances in any film.

The steady progression of the action condenses days of trial testimony into one apparently continuous story. Between the sets and this inexorable march toward Jeanne’s martyrdom, there is a sense of both spatial and temporal disorientation that focuses our attention intensely on the central conflict.

Until 1981, prints of Jeanne d’Arc were indistinct and incomplete. A pristine print that restored the original visual quality and detail was found in Norway. (The film was among the early ones to be shot on panchromatic film stock without the actors’ using makeup. The result is a detail of texture in the faces that enhances the performances tremendously.) This print is the basis for the Criterion Collection’s edition of the film.

It’s a film that one can see over and over and still be overwhelmed at the originality and intensity of Dreyer’s vision. We saw it projected last November in Houghton, Michigan, with Richard Eichhorn’s recently composed accompaniment, “Voices of Light,” essentially an oratorio and film score rolled into one. We were somewhat trepidatious about whether the score would be distracting, but it proved very effective. Once again, I was reminded of how great this film is. (“Voices of Light” is an optional accompaniment on the Criterion edition linked above.)

2. October

If Jeanne d’Arc gains intensity through a nearly claustrophobic treatment of space, Sergei Eisenstein creates an epic tenth-anniversary celebration of the 1917 Revolution in his October (finished and released a year late).

Perhaps the most extreme example of Soviet Montage’s frequent avoidance of a single protagonist, October cuts among a wide variety of the people involved in the revolution. Workers pull down a statue of the Tsar. Lenin speaks at Finland Station. Kerensky and his officials luxuriate in their Winter Palace headquarters. Sailors wait on the Aurora battleship. Elderly citizens try to protect the specious February Revolution. Female soldiers are summoned to protect the Palace from the attacking Red forces. Looters steal bottles from the Tsar’s wine-cellar. The result is a sort of patchwork collage of the Revolutionary events leading up to the storming of the Winter Palace and the attack itself, with a slow build to an exultant climax as the Red forces triumph.

Eisenstein was given extraordinary access to the locales of the actual events, so that the vast halls of the Winter Palace and the trappings of royalty (Fabergé eggs and fancy crystal liquor bottles) give a sense of reality rare in fictional reenactments. (There was a time when October was plundered for “documentary” footage of events which had not been recorded by cameras at the time.) He used the settings to ridicule the anti-revolutionary forces, as when young cadets are summoned to help fight the Red forces and are dwarfed by the muscular colossi that line one area of the Palace’s exterior (above).

The film also represents Eisenstein’s experiments with “intellectual montage,” where he attempts to convey ideas strictly through juxtaposing series of images. In belittling the phrase “for God and country,” he tries to reduce the notion of “God” to absurdity by linking a long series of increasingly exotic depictions of deities from different religions.

Whether Soviet audiences of the late 1920s could make anything of such passages is impossible to know for sure, but one suspects that some of them would have been incomprehensible. Still, it is exciting to see an artist playing with such possibilities. Certainly the technique lived on, whether from the simple juxtaposition of cackling hens and gossiping women in Lang’s Fury or Jean-Luc Godard’s dense, often impenetrable strings of images, especially in his political films.

October exists in many versions. Beware the heavily cut versions under the title Ten Days That Shook the World. These images were taken from the 2008 release by the Soviet Ruscico company in its “Kino Academia” series.

3. Spione

Despite the widespread enthusiasm for Lang’s Metropolis, his other big films of the 1920s–Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Die Nibelungen (Siegfried and Kriemhilds Rache), and Spione–seem to me better. Metropolis is perhaps flashier in its design and conception and certainly very entertaining, but it’s also sprawling and implausible and essentially pretty silly.

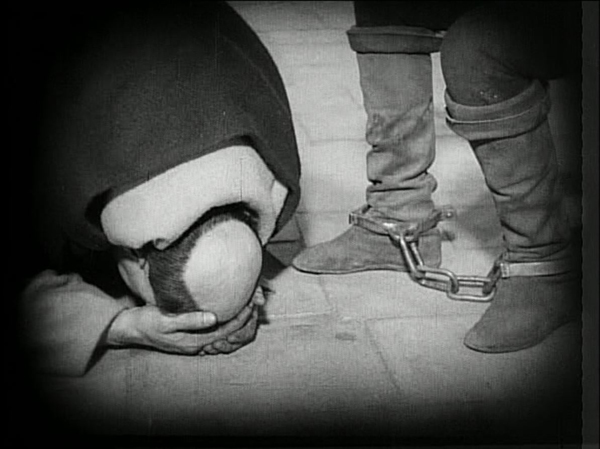

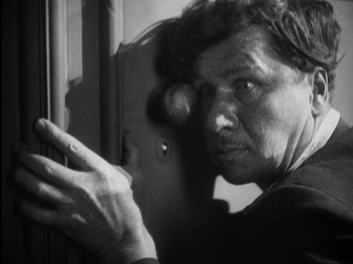

Spione, on the other hand, has a tight, fast-paced narrative. It’s sort of Dr. Mabuse boiled down to one feature instead of two, and with the villainous Haghi (again played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge) as a banker secretly masterminding a spy ring rather than a gambling racket. There are no great “heart vs. hand” themes here–just a rattling good tale stylishly presented. Expressionism has disappeared in favor of a streamlined look (above), and Lang’s editing has sped up since Mabuse.

There’s not much point in detailing the plot here, since it would involve too many spoilers. Discover it for yourself if you haven’t already.

Spione circulated for years in the truncated American release version, which is how I first saw it. A 2004 Murnau Stiftung restoration of the complete version was a revelation, not only for its more complete narrative but for its superb visual quality. It’s a feast of shots that only Lang could have composed (above and bottom). These frames are from the Eureka! DVD, but the company has subsequently released it in dual format DVD and Blu-ray. Kino Classics has also released it in Blu-ray. The same company has put out a boxed-set of all Lang’s silent films (including Die Pest im Florenz, directed by Otto Rippert from Lang’s script). We were given this recently and haven’t had time to explore it, but it looks like a must for any fan of Lang.

4. L’Argent

Marcel L’Herbier makes his second and final appearance on this annual list with his epic adaptation of Emile Zola’s L’Argent, updated to contemporary Paris. (See the 1921 entry for El Dorado; I also wrote about the Flicker Alley releases of the restored versions of L’Inhumaine [1923] and Feu Mathias Pascal [1925].)

Inspired by Abel Gance’s even more epic Napoléon (1927), L’Herbier set out to make a film that would require a large budget. To obtain that, he made a deal for his own company, Cinégraphic, to co-produce with the mainstream studio, Cinéromans. The result contains brightly lit sets of big banks and expensive apartments, as well as shots made in the Paris Bourse over a three-day weekend (above). L’Argent also had an all-star cast. It included Brigitte Helm and Alfred Abel fresh off Metropolis, thanks to the German distributor, UFA. It also meant that Cinéromans tampered with the film, re-editing and shortening it.

Given L’Herbier’s reputation as an aesthete and an avant-garde filmmaker, L’Argent was dismissed by many at the time as a purely commercial endeavor. It remained unseen and hence virtually forgotten for decades. A screening at the New York Film Festival in 1968 surprised and impressed the spectators. The real recognition of the film as a major artwork came, however, in 1973, when critic and theorist Noël Burch published his monograph, Marcel L’Herbier (Paris: Seghers, 1973). In it he hailed L’Argent as a masterpiece, devoting the entire final chapter to an analysis of it. Burch also wrote the entry on L’Herbier for Cinema: A Critical Dictionary: The Major Film-makers ([New York: Viking Press, 1980], Vol. Two, pp. 621-28), edited by Richard Roud; again Burch devoted much of his text to L’Argent.

I have expressed my reservations about L’Herbier’s films in earlier entries, but for me L’Argent is the big exception: stylistically daring and narratively engaging. Perhaps adapting Zola led L’Herbier to make a more conventionally suspenseful film than usual. Referring to the French Impressionist movement in general, Burch wrote, “L’Argent undoubtedly marks the end of the period of experimentation, since it is itself the culmination of all these experiments–not just L’Herbier’s, but those of the first avant-garde and even, to a certain extent, of the entire Western cinema (with the exception of the Russians)” (Roud, pp. 624-25).

The story involves two powerful bankers who spar for control of one large bank’s standing on the stock market. One, the villainous Saccard, aims to send a famous aviator on a perilous flight across the Atlantic to promote his bank’s oil holders in Latin America–while seducing the aviator’s wife during his absence. The other, Gundermann, tries to thwart him by buying up shares of his rival’s bank and then selling them to cause a drop in the bank’s value.

In portraying all the complex machinations going on, L’Herbier adopts a restless camera, frequently moving among and around characters rather than following them. The most striking example comes early on, when an underling comes to visit Gundermann and waits in an odd, unfurnished room decorated with a map of the world. As he looks around, the camera circles him until a servant unexpectedly appears through a door and escorts him in.

The odd distortions in these shot exemplify another cinematographic technique that was in increasing use during the late 1920s: conspicuous wide-angle lenses. On the left below, Saccard is nearly dwarfed by one of his telephones, while on the right the scene of the aviator’s departure makes the plane’s wings jut into the foreground and extend far into the background.

There are some subjective moments, carrying forward the tradition of French Impressionism. Yet for the most part the restless camera, the distorting lenses, the odd angles (see the top image of this section), and the unusual crosscutting are not subjective, which makes this an atypical Impressionist film. Instead they suggest the unnatural, disconcerting world of capitalism, of money and those who struggle over it. Perhaps by minimizing character psychology and striving to represent more abstract concepts, L’Herbier briefly carried Impressionism to a more political–and dramatic–level.

In 2008, L’Argent was released on DVD by Eureka! in the UK as a “Special 80th Anniversary 2 x Disc Edition.” The source material was a beautiful fine-grain positive struck from the original negative, with something close to L’Herbier’s original intended cut. It includes Jean Dréville’s Autour de “L’argent,” a 40-minute making-of (surely one of the first of its type), recorded during the original production. The DVD is still in print and is, as far as I know, the only release of this restored version.

5. Steamboat Bill Jr.

This was the first Keaton film I ever saw, and I immediately became a fan. (The director is credited as Charles Reisner, but we all know that Keaton was primarily responsible for the direction of his films of this period.) It’s not as good as The General (what is?), but it beats out The Cameraman, Keaton’s other feature of this year, by a nose.

Keaton plays the dandified son of a gruff steamboat owner. He returns home from school and gets put into working clothes by his father, whose deteriorating steamboat is competing for tourists with a larger, newer boat. Naturally young Bill is in love with the daughter of the other steamboat’s owner. The action mainly consists of Bill, Sr. trying to prevent Bill, Jr. from clandestinely meeting his girlfriend.

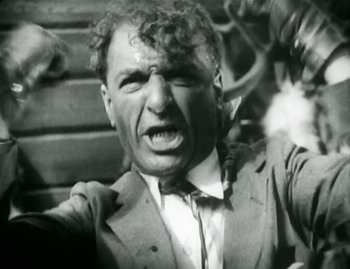

There’s lots of humor along the way to the climax, in which a huge storm hits the town. It’s a classic sequence of Keaton pulling variant gags on the situation of being in a high wind (above) and surrounded by collapsing buildings and flying objects. Perhaps Keaton’s most famous, and dangerous, gag comes when he pauses in front of a house’s façade, which tears loose and falls straight down on him–with a window sparing him from being crushed.

Reportedly the top of the frame missed his head by six inches, but we know Keaton was a little crazy in how far he would go for a laugh.

Steamboat Bill, Jr. was the last film Keaton made with his own production company. The Cameraman was made at MGM, and though it is very good, thereafter his career slowly declined after his move to that studio. This will, alas, be the last Keaton film represented in this series.

6. The Circus

Coincidentally, The Circus was the first Chaplin film I ever saw. I happened to take my first film course at the point where Chaplin had re-released The Circus, accompanied by a new musical score he composed himself. (Skip, if you can, the added opening, with Chaplin singing a maudlin song over an excerpt from later in the film.) The re-release was 1969, though I must have seen it in 1970 at Iowa City’s art-house, the Iowa. (Also coincidentally, my father managed the Iowa when he was at the university there on the GI bill in the years immediately after World War II. He was dating my mother at that point, and there she saw Day of Wrath. Hence when David and I became a couple in the mid-1970s, she understood what the book he was currently working on was about. But I digress.)

The print I saw at the Iowa was pristine.

Up to that point, The Circus had been unavailable to most viewers, though I suspect bootleg prints circulated among collectors. It’s among the least known of Chaplin’s features, and it’s still hard to see. There’s a Park Circus DVD available in England, consisting of the re-release version equally in mint condition; that’s the one I’ve taken these illustrations from. More recently the film has been released as a Blu-ray/DVD combination. There is also an Artificial Eye Blu-ray available, which gets high marks from DVD Beaver. I haven’t seen this and don’t know whether it’s the re-release version or the original.

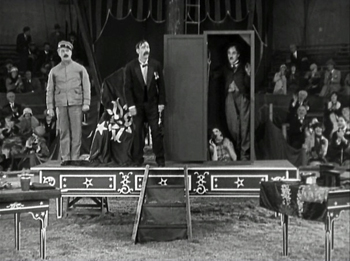

Chaplin plays his Little Tramp character, introduced wandering around the sideshow attractions near a circus. Mistaken for a pickpocket, he flees among the booths, occasioning a brilliantly staged triple scene in a hall of mirrors. When he first enters it, he is alone and struggles to figure out how to exit. A short time later, pursued by the pickpocket, the two stumble into the room, and a comic chase ensues (above). Finally, a cop is chasing Charlie, who tries to confuse him by luring him into the mirror maze. It’s a set of gags that builds, with the figures popping unexpectedly into the foreground when we had assumed that the real actors were in the depth of the shot. Each scene in the maze is handled in a single take from the same camera setup.

The flight from the cop leads the Tramp into a failing circus cursed with a group of highly unfunny clowns. Charlie inadvertently and unwittingly becomes a sensation for his antics, including his invasion of a magician’s act.

The cruel circus owner hires him, supposedly as a prop man, and the show becomes a huge success. Charlie falls for the maltreated daughter of the owner, who in turn becomes smitten by a handsome tightrope walker. Trying to impress the daughter, the Tramp goes on when the tightrope walker fails to show up one day. The result is a classic extended scene of Charlie on the high wire, executing a series of comic moments before the whole thing is topped off by a group of monkeys who escape and end up swarming over him as he struggles to keep his balance.

I hope now that The Circus is becoming more available, it can takes its place beside Chaplin’s other features.

[December 29: Thanks to Valerio Greco for alerting me that a restoration of the original version of The Circus is underway in Bologna, to be released by The Criterion Collection.]

7. The Docks of New York

I’ve already written about this, Josef von Sternberg’s final silent feature, in 2010 on the occasion of The Criterion Collection’s release of it alongside Underworld and The Last Command in an essential box-set. The six films von Sternberg made with Marlene Dietrich after she came to Hollywood generally get more attention than any of his silents. If I were allowed three of his films for a proverbial desert-island situation, I would take Underworld, The Docks of New York, and Shanghai Express.

Docks is a concentrated dose of the atmospheric cinematography the director is famous for, in this case employed to create the grungy settings of the film. In the opening, the oil and sweat on the stokers’ bodies (above) is palpable, and the fog, hanging nets and lanterns, and smoke of the dockside sets establish the sleezy, hopeless milieu that drives the heroine to attempt suicide.

Apart from the impressive visuals, the film gains much of its appeal from its two central performances. Betty Compson manages to gain our considerable sympathy for “the Girl” in a remarkably short time, and she has to–the film is only 75 minutes long and she spends her first onscreen appearances unconscious after her near-drowning. George Bancroft, known mostly for supporting roles in westerns, came into his own as the protagonists of three von Sternberg films–including Thunderbolt but not The Last Command. Here he again plays the big lug with a well-hidden heart of gold.

Unfortunately the von Sternberg silents set from The Criterion Collection is out of print. Track it down somewhere or hope for a Blu-ray release.

[December 29: Peter Becker of The Criterion Collection tells me that, although a Blu-ray release is not yet scheduled, there is a good possibility that it will happen.]

8. Storm over Asia

After Mother and The End of St. Petersburg, Storm over Asia (the original title translates as “The Heir of Genghis Khan”) is the last of Vsevolod Pudovkin’s three great silent features. Unlike the first two, it is set in Mongolia. The Soviet industry officials were concerned to portray the Revolution in the various other countries that along with Russia made up the Soviet Union.

The story takes place during the Civil War years that followed the Revolution. A young Mongolian peasant tries to sell a valuable fox fur at a trading post, but the British dealer cheats him. The peasant strikes him and is forced to flee into the mountains, where he joins the Red partisans fighting the British imperialists. (This does not follow historical fact, since the British occupied parts of Siberia and Tibet, but not Mongolia. In reality, for a brief period in 1921, White Russian forces drove out the Chinese from Mongolia. In response, the Red Army moved in, supporting the Mongols in their quest for independence.)

The British shoot the protagonist but discover on him a document that seems to identify him as the heir of Genghis Khan. So they set him up as a puppet ruler in order to control the local population. Eventually he rebels and leads a storm-like assault that defeats his oppressors.

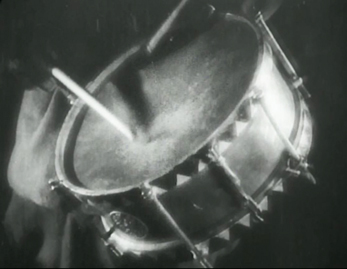

Storm over Asia uses many of the Soviet Montage devices that by 1928 were fairly conventional. For instance, there are many rapid, rhythmic alternations of shots. When the fur trader reacts angrily against the protagonist’s resistance to being cheated, brief shots of his angry call for troops to capture the young man alternate with shots of a drum being beaten. The final “storm” battle uses rapid montage as well. There is also the usual visual symbolism mocking the enemy, as exemplified by the empty officer’s uniform in the shot above.

Early Montage films tried to do away with a single central character in favor of a focus on the masses. October, for example, has no main hero. In Storm over Asia, though, the story arc is definitely crafted around the Mongol’s growth into a rebellious leader of his people. We will see Eisenstein opting for a central identification figure in Old and New (1929).

My illustrations were taken from the old Image release, apparently no longer available. The Blackhawk print has been released by Flicker Alley.

Those are the eight films I put on my “top” list. I thought of stopping there, but the number ten is sacred for such lists, plus part of the point here is to throw a spotlight on lesser-known films.

I gathered a second group of films that might claim the remaining two slots. These were mostly films that were already hallowed classics when I was in graduate school: King Vidor’s The Crowd, Jean Epstein’s La chute de la maison Usher, René Clair’s The Italian Straw Hat, and Victor Seastrom’s The Wind. Beyond that there were the more recently rediscovered and much admired film, Paul Fejos’ Lonesome and the still little-known The House on Trubnoya, by Boris Barnet.

Oddly, the three American films on this list have some distinct similarities. The Crowd and Lonesome are surprisingly parallel. Lonesome follows two lonely people in New York finding each other and falling in love in one hectic day. The Crowd starts with a somewhat similar situation–both even involve dates at Coney Island–but follows the couple through several years of happy times and misfortune during their marriage. The Wind is less realistic, dealing with a sensitive young woman who travels to the west and, plagued by the incessant wind and a real or imagined rape, slips into madness. All three strive to reject the conventional Hollywood romance. Unfortunately all three, however admirable for most of their plots, lead to abrupt, implausible happy endings.

I saw The Italian Straw Hat in my graduate-school days and found it remarkably unfunny, given its reputation. Returning to it now, I still find the first two-thirds largely devoid of humor. (The dance scenes during the wedding party seem interminable, with no little vignettes or gags among the characters at all.) The last portion picks up, but on the whole it’s hardly the model French farce it is held to be. Certainly Clair made a leap forward in skill and sophistication in his early sound films. (Les deux timides, also 1928, is no doubt a better film.)

The Italian Straw Hat probably owes its classic standing in part to the fact that the Museum of Modern Art acquired and circulated it early on. Curator and critic Iris Barry adored it and lauded it in a 1940 essay (reproduced in the booklet included in the Flicker Alley release.) I wonder how many others of the films considered classics have become so because they were among the few silents available in the decades before the 1960s, when film studies and archival curatorship began to be more comprehensive. Knowing the range of international films we know now, would these films have become quite so highly respected above others? I found myself reluctant simply to fill out my list with old standards. The choice was difficult.

Wanting to avoid carrying on the older canon at the expense of more recently rediscovered films for at least one of my films on this list, I always try to include a little-known but worthy film here. This year there is only one (if you don’t count L’Argent), and that is Barnet’s The House on Trubnoya.

The final slot goes to Epstein’s The Fall of the House of Usher. I have always considered this a somewhat tedious film, but the restoration of the film’s full length and improved visual quality in the Epstein box-set released in 2014 by La Cinémathèque Française makes it far more interesting and effective.

So here is the completion of my list.

9. The House on Trubnoya

Boris Barnet was a member of Lev Kuleshov’s school in the early years after the revolution. He played a major role in Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, and he began directing films on his own with the wonderful serial, Miss Mend. He made more films, and some others may show up in our coming lists. Right now, there’s The House on Trubnoya.

The House on Trubnoya is included in Flicker Alley’s major DVD set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.” (I can’t believe that we didn’t feature this on our blog, but it includes eight major Soviet films of the silent era.) The copy on the back of the box describes Barnet’s film as “often described as one of the best Soviet silent comedies.” I’m not sure that’s a major distinction, though Kote Miqaberidze’s Georgian satire My Grandmother (1929; available on DVD and Fandor’s Amazon streaming site) is quite funny, as is Ivan Pyriev’s The State Functionary (aka The Civil Servant; not, as far as I know, available on home video). But The House on Trubnoya is my favorite among the comedies I’ve seen.

It’s a satire on middle-class citizens’ maltreatment of their servants, though it doesn’t become Soviet-style preachy until well into the story. The film begins by setting up the titular house (on a well-known street in Moscow). We see it via its staircase and landings in the morning, rendered in a vertical view that looks startlingly like an iPhone image (above). It also recalls the seven levels in the staircase elevator shot climbing upward to 7th Heaven, though who knows whether Barnet had seen that by the time he planned his film. The residents of the various apartments emerge to use the communal stairway as a junkyard and work area, dumping trash, splitting firewood, beating curtains, and generally abusing the rules of the building, as one conscientious young Party member points out.

We are introduced to a barber, whose lazy wife makes him do all the chores. Then suddenly we’re with a professional driver with his own car. Just as suddenly we’re watching a peasant girl chase her runaway duck through a maze of traffic and nearly get hit by a tram. As the driver brakes hastily and jumps out to see if she’s hurt, there’s a freeze-frame.

A narrating title declares, “”But wait, we forgot to tell you how the duck ended up in Moscow.” Reverse motion leads to another title, “A day earlier.” A flashback to the heroine’s comic departure from a train station in the middle of nowhere shows the very uncle whom she is going to Moscow to visit arriving at the station just after she has left. Finding herself lost in Moscow with her duck, the heroine gains employment as a put-upon maid serving the barber and living in the house on Trubnoya. Her political awakening and the rehabilitation of the House on Trubnoya form the rest of the plot.

The House on Trubnoya is, in short, an imaginative, clever, and funny Soviet Montage film. Barnet’s other films are worth exploring as well. Check out The Girl with the Hatbox from 1927; it didn’t make last year’s top items, but it was on the long list.

10. La Chute de la maison Usher

Jean Epstein, who was probably the finest of the French Impressionist directors, has figured in these ten best lists before, in 1923 for Cœur fidèle, in 1924 for the little-known L’affiche, and 1927 for his masterly La Glace à trois faces.

I have long considered La Chute de la maison Usher interesting for its use of German Expressionist-inspired sets, but the fuzzy, incomplete prints that for decades were the only available versions made it difficult to enjoy. The restored version on the complete DVD set of Epstein’s works, which I discussed here, makes it far more interesting.

Taking its slim plot from Poe, the film follows a visit by an elderly man to the isolated castle of his old friend, Roderick Usher. Usher is painting a portrait of his beloved wife, but it is soon made clear that each time he presses the brush to the canvas, a little of her life is drained away–though the local doctor is mystified by her decline.

The film retains some of the traits of Impressionism, as when Madeline’s reaction to the effects of her husband’s painting are rendered in a superimposition of negative and positive images of her face.

The film has a minimal plot, but its focus is largely on experimentation in creating an eerie atmosphere. Shots of books falling in slow motion from their shelves, of curtains blowing in a cold wind that seems perpetually to invade the house, of frogs copulating in a nearby pond, and of the Expressionist-derived decors contribute less to a linear plot than to a mood of undefined menace.

The castle’s exterior is represented by obvious cardboard models, which tends to undermine the effect created by the interiors. The cheapness of these models is particularly noticeable in the climactic scene of the destruction of the house. This is unfortunate, but one must give Epstein credit for having done so much with so little.

This will be Epstein’s final appearance in our “Ten Best” lists, but I would like to call attention to his other 1928 film, Finis Terrae, the first of what the Epstein box-set collects as his “Poémes Bretons.” These are less Impressionistic, though Finis Terrae has a few impressive subjective shots. They are more realistic and poetic, largely involving the sea.

As I wrote at the beginning, 1928 was part of the period when the American industry was on the cusp of making sound standard in its films. Other national cinemas followed at various paces. One film that did not quite make my top-ten list demonstrates what must have worried film theorists and critics–and no doubt some filmmakers.

The restored version of Lonesome includes some dialogue sequences in a film otherwise accompanied by recorded music. There is an enormous contrast between the silent and sound footage. The story is largely told visually, but the dialogue scenes, clearly done in a sound-proof studio, are delivered in a stilted fashion by the young actors who are otherwise so casual and lively. The prospect of whole films being made in that fashion clearly disturbed lovers of films like La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and Steamboat Bill, Jr. Watching Lonesome gives a dramatic insight into this slice of cinema history–a period that fortunately lasted only a few years as the technology improved and as filmmakers increasingly managed to make sound films that were just as imaginative, artistic, and engrossing as their silent predecessors.

January 6, 2019: Thanks to Docks of New York fan Tony Lucia for a correction on that section.

Spione

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

The ten best films of … 1927

Underworld.

Kristin here:

Once again it’s time for our ten-best list with a difference. I choose ten films from ninety years ago as the best of their year. Some are well-known classics, while others are gems I have found while doing research for various projects–though I have to admit that most of the films on this year’s list are pretty familiar.

One purpose of this yearly exercise is to call attention to great films of the past, for those who are interested in exploring classic cinema but aren’t sure where to start. (Previous lists are 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, and 1926.)

Hollywood dominates this year, with half the list being American-made.

There are reasons for the lack of international titles. This year was was the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but although Vsevolod Pudovkin’s celebratory film The End of St. Petersburg is here, Sergei Eisenstein did not finish October in time and it came out in 1928. (I remember the third anniversary film, Boris Barnet’s Moscow in October, as good but not necessarily top-ten material.) Some major directors didn’t release a film or made a lesser work. Dreyer was at work on The Passion of Joan of Arc, but it, too, wasn’t released until 1928. Lubitsch made The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg, a good but not great entry in his oeuvre. Japan’s output is largely lost. Yasujiro Ozu made his first film in 1927, but his earliest surviving one comes from 1929. Most of Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1920s films are gone, including those from 1927.

1927 was the year when Hollywood dipped its toe in sound filmmaking, but we need not worry about the talkies for now. Instead, all ten titles are examples of the state of sophistication that the silent cinema had achieved by the eve of its slow demise. (Sunrise‘s recorded musical track does not a talkie make.)

Hollywood, comic

The General is often listed as a 1926 film. This is technically true, in a sense, but I choose not to count its world premiere in Tokyo on December 31, 1926. Its American premiere was scheduled for January 22, 1927 but was delayed until February 5 by the popularity of Flesh and the Devil, which was held over in the theater where Keaton’s film was eventually to launch.

David recently posted an entry on how the great silent comics moved from shorts in the 1910s to features in the 1920s. His example was Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy, one of our ten best for 1924. Keaton moved into features slightly later than Lloyd, excepting The Saphead (1920), an adaptation of a play, in which Keaton was cast in the lead but over which he had no creative control. Once he did tackle features, he soon became adept at tightly woven plots with motifs and sustained gags. The General, based on a real series of events during the Civil War, has a solid dramatic structure that is more than just an excuse for a bunch of humorous bits. (A dramatic film, The Great Locomotive Chase, was produced by Disney in 1956 and based on the same events.)

The French title of The General is Le Mécano de la General. One might call Keaton that, since The General‘s comedy is essentially a long set of variations on the humor to be gotten out of the physical characteristics of a Civil-War-era train and its interactions with tracks and ties. Keaton had always been fascinated by modes of transportation and other mechanical sources of gags: an earlier train in Our Hospitality, boats in The Boat and The Navigator, a DIY house (One Week), film projection in Sherlock Jr., and so on.

At the beginning, Keaton’s character, Johnny Gray, tries to enlist in the Confederate army, but he is rejected without explanation. The officers consider him more valuable as a train engineer. Later, when Johnny is taking troops up to the front, a group of disguised Union soldiers steal his beloved engine, “The General.” Pursuing the thieves, he ends up deep in Union-occupied territory and takes his engine home, just in time to participate in a battle and prove his worth as a soldier.

The perfection of Keaton’s construction of gags is evident in one famous scene where Johnny’s engine is towing a cannon pointed up at an angle that would clear the cab if it were fired. Johnny has just loaded it with a cannon-ball and lit the fuse; he is returning to the engine when he foot becomes caught in the hitch attaching the cannon to the fuel car. The hitch drops, jolting against the ties so that the cannon slowly sinks to point straight ahead. A cut to a side view shows Johnny noticing this and panicking.

A view from behind the cannon emphasizes his danger as he starts to climb into the fuel car but gets his foot caught in the chain, a situation made clear by a cut-in. Once he is atop the wood-pile, he throws a log which fails to shift the cannon’s aim.

A cutaway establishes the Union soldiers who have stolen the General, approaching a lake in the background. Back at the pursuing engine, Johnny gets onto the cowcatcher, as far from the cannon as he can get. A return to the previous framing shows Johnny’s engine starting to turn on a curving stretch of track with the lake in the distance. The cannon follows.

As Johnny’s engine moves just out of the cannon’s trajectory, it fires. This would be enough for the pay-off of this elaborate gag, but the smoke quickly blows aside (possibly a wind machine offscreen left?) and we see the explosion in the distance near the General. As so often happens with Keaton’s gags, we are likely to gasp in amazement at the moment’s sheer physical complexity and ingenuity, as well as Keaton’s dexterity, before we start laughing.

The consensus among most critics and historians is that The General is Keaton’s finest film. In my opinion it goes beyond the top ten for a year to the top ten, period. Participating in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll of scholars and filmmakers, I put it in my list of ten films. It only made it to number 34 among voters, but then, my opinions didn’t coincide too well with the “winners.” Only two of the top ten were on my list. Such exercises are hardly definitive, given how difficult it is to choose among films at the highest levels of brilliance. That’s why David and I tend to stay away from them–except for films made ninety years ago.

Harold Lloyd’s The Kid Brother is similarly one of his finest, along with Girl Shy (featured on my 1924 list and discussed by David in a FilmStruck introduction and his entry linked above). As David points out, Lloyd’s features usually give his character a flaw to overcome. Here, as a country boy overshadowed by his tough father and two older brothers, he believes himself to be timid and not worth much. He eventually proves himself, of course, partly from a desire to save his father, who is wrongly accused of stealing some money, and partly through the encouragement of Mary, owner of a medicine show passing through town, with whom he falls in love.

Harold Hickory is quickly set up as fantasizing that he is as capable as his father, the local sheriff, when he holds his father’s badge against his chest (see the top of this section). Not just a prop for character exposition, however, the badge leads him to be mistaken for the real sheriff. In trying to pass himself off as a convincing sheriff, he sets in motion a series of events that lead to the accusation of theft against his father and his attempts to recover the money from the real thieves.

As with Keaton, one of Lloyd’s strengths was an ability to plan a gag to use the whole frame, whether in depth or from side to side. The film stages several scenes in depth, as when the dishonest medicine-show men who will eventually steal the money arrive to try to get a permit to perform in town. As they arrive, Harold is seen in depth, wearing his father’s hat and badge, thus setting up the idea that they will believe that he is actually the sheriff. A more extended example occurs later, when he meets and is attracted to Mary, he climbs a tree to call after her as she leaves him, disappearing again and again behind a hill in the distance, and reappearing each time he climbs higher.

Lloyd skillfully employed shallow space equally well. When the medicine-wagon is destroyed by fire, Harold invites Mary to spend the night at his house. A disapproving neighbor lady soon takes her away, and Harold sleeps on the couch he had made up for Mary, complete with a tablecloth hung to give her privacy. Believing Mary still to be in bed, the two brothers separately sneak in to court her by primly handing her breakfast and gifts around the edge of the cloth. A shot from the other side shows Harold pretending to be Mary and enjoying being served food by the brothers when it is usually he who does the cooking.

Like The General, The Kid Brother demonstrates the sophistication that the great silent comedians had achieved by the late silent period.

As with the Lloyd films included in previous lists, The Kid Brother was released in the 2005 New Line boxed set, “The Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection,” now out of print and available only from third-party sellers. Sold separately, Volume 2 is still in print; it contains The Kid Brother and The Freshman, as well as other important Lloyd films. Volume 3 is still available new from third-party sellers. Volume 1 is available from third-party sellers, mainly in used (and higher-priced copies).

Hollywood, serious

The popular impression seems to be that the gangster genre originated in the early sound period. Wikipedia’s entry on the subject treats Public Enemy (1931), Little Caesar (1931), and Scarface (1932) as the first gangster films. There had been occasional silent films that could fit into that category, notably The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912, D. W. Griffith) and Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915, Maurice Tourneur). In 1927, however, Josef von Sternberg made Underworld, which basically defined the genre that would soon become more prominent.

It has the gangster’s little mannerism, with “Bull” Weed bending coins to show off his strength (possibly the source of the cliché of the gangster flipping a coin). There’s the emblematic and ironic death, as when Bull’s nemesis “Buck” Mulligan is shot and falls at the foot of a cross-shaped memorial arrangement of flowers in the shop he uses as a front. There’s the thug with a heart of gold redeemed by the loyalty of a friend.

Von Sternberg is most often associated with Marlene Dietrich, whom he directed in seven films in the 1930s. He built three of his last four films of the late 1920s, however, around the burly star George Bancroft (below left). (We will encounter the second in next year’s list.) He’s also associated with beautiful design and cinematography, and the look of Underworld often anticipates the films noir of the 1930s (above, top, and below right).

I’ve already written about Underworld in greater detail than I have room for here–with additional pretty pictures. That was on the occasion of Criterion’s release of a set containing von Sternberg’s last three silents. Still indispensable but out of print and selling for high prices when you can find it. (Time for a Blu-ray?)

Late in her life, I asked my mother (born in 1922) what the earliest film she could remember seeing was. She replied that she couldn’t give me the title but recalled an image: a woman floating on a lake supported by reeds. I was quite astonished, partly because of all possible late 1920s films she had mentioned one which I could identify instantly from that brief description and partly because her memory had retained an impression of one of the great classics of the silent cinema. Living on a farm in Ohio, my mother probably saw it in a late run and so probably was six or seven at the time.

The presence of Sunrise on this list will hardly come as a surprise to anyone. Murnau has been a regular, appearing in our 1922, 1924, 1925, and 1926 entries. His first Hollywood film was thoroughly Murnauesque in style. It’s story of village versus country with a lingering touch of Expressionism in the rural scenes (below left) and modern design on ample display in the city (below right). The action could be set equally plausibly in Germany or the USA, except for the English-language signs in the city.

The plot is simplicity itself, with none of the characters even given a name. A Man is seduced by a Woman from the City, who convinces him to drown his Wife “accidentally” and flee with her to the gaiety of urban life. He nearly pushes his Wife into the lake while rowing across to the mainland but relents and tries to gain her forgiveness. This all occupies less than half the film, and most of the rest consists of the couple going forlornly to the city, with the Wife heartsick and the Man pathetically trying to reassure her. Once they reconcile, there is a long stretch of them having a good time in the city before heading home.

Yes, a good time. One might expect the city to be a hotbed of decadence that contrasts with their virtuous country life, but apart from an aggressively flirtatious gentleman, most of the people they meet are kind to them. A friendly photographer thinks they are a newly married couple and takes their portrait, sophisticated patrons at the dance-hall appreciate their performance of a country dance (below), and so on.

This meandering little set of unconnected vignettes does not conform to the Hollywood ideal. It presumably aims to guarantee that we believe in the husband’s redemption and the couple’s future happiness after their symbolic “re-marriage.” It holds our attention partly because of the charm of the two lead actors, George O’Brien and Janet Gaynor, and partly because the visual style always gives us something to look at. Murnau uses his “unfastened” German-style camera movements, not only in the famous track to the marsh early on but in a movement over diners’ heads accomplished by placing a camera on a support suspended from a track on the ceiling. (This technique was being widely adopted in Hollywood during the second half of the 1920s.)

Plus there’s that memorable scene of the Wife drifting on the lake, supported by reeds.

Sunrise is available in the elaborate 2008 12-disc boxed-set “Murnau, Borzage and Fox,” though the print is the usual soft, rather dark one available elsewhere. (The main gems of the box are the rare Borzage silents, including Lazybones, one of my 1925 picks.) Eureka! put out an edition of Sunrise as the first entry in its “Masters of Cinema” series. It contains not only the same print but a second print, a Czech release with distinctly better visual quality. (The image of the restaurant directly above was taken from it, while the others are from the “Fox Box.” I have not made a comparison between the two, but apparently the Czech version has significant differences from the American one.) This edition is out of print. Eureka! now offers the same two prints and supplements as a DVD/Blu-ray combination. Note that (despite what the Amazon.uk page says), this is a region 2 DVD and region B Blu-ray; both would require a multi-standard player in the USA and other regions.

The same “Fox Box” set contains Frank Borzage’s 7th Heaven, one of his best-loved films. By rights it should not be a great film. It is intensely sentimental, depends on huge coincidences, and has a thoroughly implausible ending, not to mention a saccharine religious theme that runs through it. Yet somehow it manages to be the greatest hypersentimental, coincidence-ridden, implausible, pious film ever. I cannot explain how or why.