Archive for the 'Film archives' Category

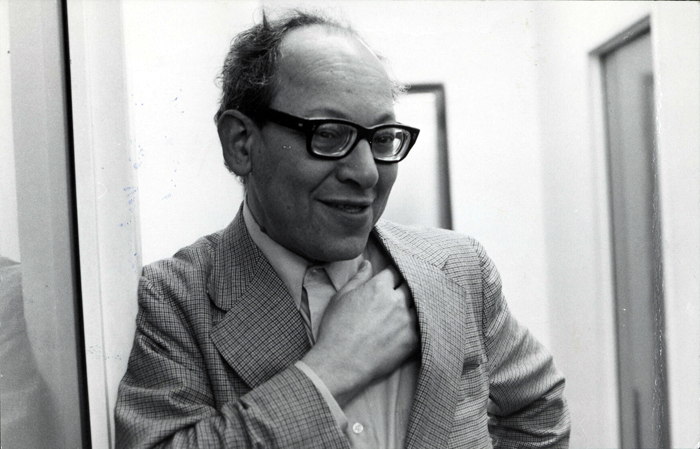

Jacques Ledoux, man of the cinema

Jacques Ledoux.

DB here:

Jacques Ledoux, one of the world’s premiere film archivists, died in 1988, but his example and influence live on. An insatiable cinéphile, a friend to filmmakers around the world, and a tireless collector of films for the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, Ledoux did not have the celebrity status of Henri Langlois. Quietly and modestly, he went about the task of building one of the great film libraries and launching traditions that outlived him. He was at the center of Belgian film culture, which was as cosmopolitan as any you would find in bigger European or American cities.

Central examples of his enterprise: EXPRMNTL, the Knokke-le-Zout experimental film festival; the annual Cinédécouvertes summer festival showcasing films of exceptional ambition that had not yet found a local distributor; and the L’Age d’or prize for films challenging “cinematic conformism.” Martin Scorsese’s The Big Shave (1967) had its premiere at Knokke, where it won the Prix L’Âge d’or. The first winner, in 1955, was Agnès Varda for La Pointe Courte; later winners read like a roster of great directors. The impulse continues to this day. In addition, Ledoux established a distribution branch that allowed student groups and film clubs to borrow prints for their screenings.

There were always obscure legends about his past. “Jacques Ledoux”–“Jacques the Gentle”–was a name he took late in life. Eventually we learned that as a boy he survived the Holocaust by jumping off a train shipping him to Auschwitz. By the end of the 1940s he was participating in the Archive’s activities and he eventually became the director.

Ledoux set about creating a vast showcase of world cinema. Five screenings, two of them silent films, ran every day of the year. Admission prices were low, to permit students to come. At the same time, Ledoux oversaw collections of film technology that formed the basis of educational exhibits. The Archive became the center of the city’s film activities.

Ledoux was a passionate collector, amassing films from far outside Belgium. He was curious about all types of cinema, mass-market and esoteric. When the Nouvelle Vague directors wanted to see a film banned in France, they took the train to Brussels and Ledoux’s domain. The same urge for comprehensiveness informed his efforts to document film history, with filmographies and background information in books published by the Archive. He became a moving spirit of FIAF, the International Association of Film Archives; here you can read about his many accomplishments in that area, as well as his eventual friction with the organization.

His generosity extended to young researchers like Kristin and me, who were welcomed to study films at the Archive. That became the basis of our lifelong friendships with Archive staff and many Belgian cinéphiles, as sometimes chronicled in our blog entries. So grateful was I for Ledoux’s assistance that when I was offered a professorship at my university, I gave it his name. He had just died, and he probably would have protested that he wasn’t worthy; but he has remained an inspiration to us for over forty years.

His generosity extended to young researchers like Kristin and me, who were welcomed to study films at the Archive. That became the basis of our lifelong friendships with Archive staff and many Belgian cinéphiles, as sometimes chronicled in our blog entries. So grateful was I for Ledoux’s assistance that when I was offered a professorship at my university, I gave it his name. He had just died, and he probably would have protested that he wasn’t worthy; but he has remained an inspiration to us for over forty years.

The Archive, now calling itself the Cinematek, has just finished a centenary exhibition devoted to Ledoux. Christophe Piette, organizer of the event, has memorialized it in a lovely multilingual book that gathers reminiscences by Ledoux’s colleagues. There are memoirs by Noël Desmet, Clementine Deblieck, Jean-Paul Dorchain, Hilde Delabie, and Gabrielle Claes, Ledoux’s successor as director. Bernard Eisenschitz, Eric De Kuyper, and P. Adams Sitney offer illuminating appreciations of Ledoux’s contributions. (Sitney’s very full account of Knokke doings is a crucial document in the history of the American avant-garde.) Ledoux’s own voice is represented by a program note for a 1968 science-fiction series. There are many wonderful illustrations–photos, posters, correspondence (Cocteau, Lenica, Akerman). Kristin and I have provided recollections of a man we immensely admired. When you read one of our blog entries on older films, classic or little-known, chances are good that we first saw the film at the Cinematek.

The book is published in a limited edition but is available for purchase at https://cinematek.myshopify.com/en/collections/boeken/products/jacques-ledoux. Every university library with a substantial collection of film literature should acquire a copy!

Anke Brouwers has written a vivid overview of Ledoux’s career for the exposition. Many nifty documents are illustrated.

There are too many citations of Ledoux and the Archive on our site for me to list them. Two extensive ones are “Ledoux’s Legacy” and “Watching movies very, very slowly.” For others, you could try the Search function (using “Brussels”) to find accounts of our many visits.

When media become manageable: Streaming, film research, and the Celestial Multiplex

Never coming to the Celestial Multiplex: Liberty Belles (Del Henderson, 1916).

DB here:

A directors’ roundtable in The Hollywood Reporter says a lot in a little.

Fernando Meirelles: This June, The Two Popes was in 35 festivals. Then we were going to have two or three weeks of theaters. And then the [Netflix] platform. I mean, it couldn’t be better.

Martin Scorsese: We are in more than an evolution. We are in a revolution of communication and cinema or movies or whatever you want to call it.

Meirelles casually omits DVDs, at one point the most rapidly adopted format of consumer media. Yeah, what ever happened to discs? And in what follows, I’ll take issue with Scorsese’s claim that streaming has triggered a revolution. It’s more a case of evolution that issued in a sweeping change, like Engels’ transformation of quantity into quality, or Hemingway’s claim that he went broke slowly, then quickly.

More important, I’ll try to assess the impact streaming has had on what Kristin and I and other researchers and teachers try to do–study film as an art form in its historical dimensions.

Managing your time, and your movies

If we’re looking for a revolutionary turning point, I’d suggest the moment that movies no longer became appointment viewing. When they played theaters you had limited access. The film was there for only a while (even The Sound of Music eventually left) and you had to watch it at specified times. On broadcast TV and cable, the same conditions applied. But with the arrival of consumer home videotape in the 1970s, the viewer was given greater control.

Akio Morita of Sony called it “time-shifting.” The phrase, shrewdly positioned as a defense of off-air copying, captures a fundamental appeal of physical media. You could watch a film at home, and whenever you wanted to. Yes, VHS and even Beta yielded shabby images and even worse sound, but (a) theatres were often not much better, and (b) a video rental was cheaper than a movie ticket. Most important was a general rule of media technology: For the mass market, convenience trumps quality.

Videotape swept the world in the 1980s and gave films an aftermarket. Many an indie filmmaker could get financing for a project on anticipated tape sales. The laserdisc gained some attention in the 1990s, becoming a sort of transitional format. It improved quality (better analog picture, digital sound) but had drawbacks too. A movie wouldn’t fit on a single disc side, and a laserdisc was pricier than tape. LD remained a niche format, chiefly for educators and home-theatre enthusiasts.

The laserdisc was superseded by the DVD, introduced in 1996. Journalists claimed that it enjoyed the fastest consumer takeup in electronics history. Discs were more convenient than tapes, and proof of concept had been provided by the success of CDs for music. To compete, cable companies introduced “video on demand,” a time-shifting compromise between scheduled cable delivery and rental of tape or disc. People still use cable VOD, and for some purposes it’s a cheaper alternative to committing to subscription services.

Reviewing The Irishman, a critic suggested that most people will skip seeing it in theatres and watch it on Netflix, where it’s “more manageable.” With tape and disc, either analog or digital, consumers became accustomed to a huge degree of manageability. They could pause, skip ahead or skip back, race fast-forward or –back, play slowly, and above all play the movie over and over. DVDs made all these options quicker and more convenient than tape had. The market boomed. Video stores made discs available for rental, as tapes had been, and retail stores offered them for sale, at increasingly low prices.

But there were problems. In the 2000s there was a glut of DVDs, and consumers began to realize that a few weeks after release many titles would end up in the bargain racks. A brisk secondary market developed thanks to the US “first sale” doctrine, most virtuosically exploited by Redbox. Worse, there was piracy. Pirating analog tapes degraded quality across generations, but with digital discs you could rip perfect clones. Any teenager could hack past region coding and anticopying software.

The Blu-ray disc was an improvement on the first-generation DVDs, and it came along as more people were buying widescreen and high-definition home monitors. Properly mastered, Blu-ray discs looked good, and they had bigger storage capacity. Some consumers got excited, but the improved format couldn’t arrest the headlong decline of disc sales. In addition, the industry’s rationale for Blu-ray was its resistance to rippng, but hackers breached the codes with ludicrous speed.

From this angle, streaming is parallel to digital theatre projection : a new phase in the war against piracy. Likewise, as in theatrical screenings, you’re paying for an experience, not an item. You’re not buying an object you can copy or resell. If a movie is available only on streaming, you’re renting something, not owning it legally. One aspect of manageability—personally possessing a movie—is traded away for convenience and, ultimately, for limited access, as I’ll try to show.

Not so gently down the stream

With streaming, the age of appointment viewing seems more or less over. And the infinite vista of the Internet has encouraged tech-heads to imagine something like the Celestial Jukebox, a vast virtual multiplex in which all movies will be available. If iTunes and Spotify did something like this for music, why not cinema?

Let’s consider the pluses and minuses of streaming for ordinary consumers and for filmmakers.

Obviously, there’s convenience. After the monstrous tape cassettes, DVDs looked adorably slim. Now, gathering in slippery stacks, they have their own sinister aura. With streaming, there’s no need to run out to the video store or to buy new shelving to support a bulging library of discs.

There’s also price, compared to either theater tickets or cable fees. From $6.99 per month (Disney+) to $12.99 (Netflix), streaming services promise to provide TV and movies quite cheaply. And there’s the range of choice, which even on second-tier streamers exceeds the capacity of most towns’ video stores back in the day. Finally, there are many obscure films lurking in the corners of most streamers, so the joy of discovery is still there to a degree.

On the minus side, there’s one that gets the most press—the further erosion of “the theatrical experience.” Critics emphasize the pleasures that come from being in an audience, but this always seems to me overrated. More valuable to me are the scale of image and sound you get in a theatre. I like my movies to loom.

Above all, there’s a virtue in the lack of manageability. In the theatre you can’t pause the movie or run back or skip ahead. You can close your eyes, look away, or leave, but at bottom you’re there to turn your sensorium over to the filmmaker, to go through an experience you don’t control. This unshakeable grip on your attention yields some of cinema’s most powerful effects.

The condition of privatized viewing isn’t unique to streaming, of course. Nor is another drawback, that of the cyclical expiration and refreshing of “content” on streaming platforms. Admittedly, we’re warned. Newspapers and websites run alerts notifying us when a title is leaving a service—perhaps for a little while, perhaps longer, perhaps forever. And this situation is a bit like DVDs’ going out of print. But at least some disc copies exist to be sold second-hand or cloned as files. In working on my book on the 1940s, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that I could track down arcane titles on out-of-print discs, and at fair prices. When something not on disc leaves streaming, how do you access it?

I think there will be some pushback when subscribers learn about the costs that more and more services are tacking on. Yes, with Amazon Prime for $119 per year you get access to many films, along with other services. But for a great many films Amazon demands an extra rental fee and very short-term access. Within Amazon, there are channels (Britbox, HBO Now, Starz, Cinemax et al.), all of which demand further subscription payments. As people start to realize that streamers will have exclusive licenses for titles, they’ll feel pressure to subscribe to many services. Here, as elsewhere, the total streaming price tag starts to look like cable fees. Even the New York Times has noticed.

Another problem won’t bother most consumers, but it does matter. A streamed title will occasionally be in an incorrect aspect ratio. Most commonly, a Scope (2.39 or so) image will be cropped to 1.85. I noted this some years back, relying on a website showing faulty Netflix transfers, but that site seems to have been taken over by … Netflix itself.

Netflix will say, with all “content providers,” that they get the best material they can from their licensors. I don’t watch streaming enough to know how common wrong aspect ratios are, but if you know of examples, I’d like to hear.

Finally, even streaming companies can collapse. Unless Apple buys a studio (Lionsgate? MGM? Columbia?), it must rely on original content, and it could well flop. On the day I’m writing this, one hedge fund manager predicts we have reached peak Netflix. Given greater competition, slower growth, and accelerating cancellations, he maintains that Netflix is on the wane. If it scales back or fails (it currently carries $12.43 billion in debt), what will happen to its licensed material and its original content?

What about creators? Filmmakers, especially screenwriters, have enjoyed boom times. It may be a bubble, with over 500 scripted series available on broadcast, cable, and streaming. Still, it has given everyone a lot of opportunities. Documentary filmmaking in particular has enjoyed a shot in the arm.

And features are still doing quite well, at least on Netflix. Of the streamer’s top 10 releases in 2019, seven were features. But those proportions may change. Aside from big theatrical movies licensed from the studios, the impact of proprietary “event” programming (War Machine, Bird Box) has been fairly ephemeral. (Obviously Roma and The Irishman are exceptions.) The strength of streaming, it seems to me, is the same thing that sustained broadcast TV: serial narratives. Hence the popularity of Friends and The Office, as well as House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black.

Like network TV, a streamer needs a reliable, constant flow of content—not only many shows, but many episodes. The model of the series, if only in six or eight parts, secures the loyalty of the viewer for the long term. Even if all episodes are dumped at once, the promise of continuation after an interval of a year or several months keeps the viewer willing to hang on till the next season.

The pressure on the creators is predictable. Since form follows format, writers and producers will be pushed to come up with series ideas. A friend of mine pitched a feature-length movie to a streaming service. The suits loved the idea but wanted it as a series and were already scanning the script outline for a plot point that could launch a second season. Some of the streaming series I’ve seen, notably Errol Morris’s Wormwood, seemed to me stretched.

If a filmmaker lands a feature film on a streaming platform, other problems could follow. We’re well aware that independent filmmakers gain few royalties from streaming; their big check tends to be the initial acquisition. At the same time, they can’t be sure that people are watching their entire movie. My barber couldn’t stick with The Irishman, even with pee breaks.

Streamers seem to have accepted grazing as basic to the viewing experience. For purposes of measuring total viewership, Netflix counts a “viewing” of a film or program as a minimum of two minutes. In the light of the two-minute rule, we might expect filmmakers to crowd their opening scenes with plenty to grab us. That goes back to TV and TV-influenced films, of course, which tried to have a strong teaser even before the credits. Now, it turns out, streaming pop songs are being crafted with shorter intros and earlier choruses “to get to the good stuff sooner.” Maybe filmmakers will be trying the same thing. Maybe they already are.

Streaming and film research

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018).

Finally, what are some consequences of streaming for researchers, educators, and your all-around obsessive cinephile?

I think it’s fair to say that home video, in the form of tape, laserdisc, and digital disc, democratized film study. From the late 1960s on, I traveled to archives and film distributors to watch films for my research. It was troublesome, time-consuming, and costly. As a grad student I took a bus from Iowa City to Chicago to watch 16mm prints of Dreyer and Sontag films. I drove to Eastman House to see films in projection. I stayed in Paris a couple of months to work at the Cinémathèque Française on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse.

As a prof here at Madison I spent hundreds of hours watching prints in our Center for Film and Theater Research. Over the decades I trekked to Denmark for Dreyer and 1910s films, to Japan for silent films, to Paris and Munich and the BFI and MoMA and UCLA and Eastman House and the Library of Congress, and above all Brussels for many, many projects. Collectors, from Manhattan, Tokyo, and Milwaukee helped as well. Kristin and I owe archivists everything.

The terrible quality of films on tape didn’t help me study visual style, but laserdiscs were a big improvement. (Hong Kong films tended not to be in Scope on tape but were on LD.) And one LD format, CAV, was frame-accurate; you could study a shot frame by frame, something not possible with many DVDs. There’s always a trade-off with any technology.

Even after even after DVDs arrived I kept up my travels. I could use discs for bulk background viewing, but often I still had to rely on prints. Sometimes I wanted to count frames (handy in looking at Soviet montage and Hong Kong action). Moreover, looking at film prints revealed that the color palettes on DVDs could be quite different, and soundtracks were often cleaned up for the home market. And of course thousands of films, especially from outside Hollywood or in the first decades of cinema, were never going to be available on consumer video. My most recent extended archive stay, in Washington in 2017 thanks to a Kluge Professorship, showed me the glories of the 1910s in prints that are mostly accessible only to researchers.

What do scholars of an analytical bent need? Entire films that can be paused. Frame stills, made photographically or through software. Clips as evidence for our claims. Stills and clips are our equivalents to quotation for literary scholars and illustrations for art historians.

Apart from convenience and cost savings, the disc revolution yielded something I couldn’t get otherwise. In an archive, it’s impossible to study film-based 3D cinema. But thanks to Blu-ray, I can stop on a 3D frame. (. . . And, for instance, spot the way Hitchcock makes the clock quietly pop out in Dial M for Murder, below). This is a unique benefit—but a waning one, as 3D discs are increasingly hard to find and 3D monitors scarcely exist any more. As I said, trade-offs.

From this standpoint, Netflix and its counterparts offer a step down from DVD and Blu-ray. In terms of choice, many films aren’t currently available on streaming, and many more never will be. You can pull a DVD off a shelf whether you’re online or not, but for streaming you need a good connection. The controls of a streaming view aren’t as precise as those on a DVD player; slow forward and back to study cuts and gestures aren’t feasible, it seems.

When cable cropped films, as it frequently did, you had recourse to DVDs, perhaps even from foreign sources. But as exclusive licensing increases, only one service will have a title. Frame grabs are possible with some software, but clips are more difficult.

Worst of all, many worthwhile films will apparently never find their way to disc. I first noticed this in 2017 when I wanted to buy a copy of I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, a Netflix release of a Sundance title. As far as I can tell, it’s not available on DVD. The same fate has befallen one of my favorite films of 2018, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Only a few years ago it would be unthinkable for a Coen Brothers film not to find DVD release. Even Roma has had to wait for a Criterion deal to make it to disc. Clearly Netflix, and perhaps other streamers, believe that putting films on disc damages the business plan. So Meirelles doesn’t include DVDs in the lifespan of The Two Popes.

Without DVDs, some cinephiliac consumers are lamenting, rightly, the loss of bonus materials. The Criterion Channel has been exceptionally generous in shifting over its supplements to the streaming platform, but other companies haven’t been. Scholars and teachers rely on the best bonus items, including filmmaker commentaries, to give students behind-the scenes information on the creative process. There are, I understand, rights issues around supplements, and bandwidth is at a premium, but there’s no point in pretending that the loss of disc versions hasn’t been important.

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas put forth the question debated in the directors’ roundtable I mentioned: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

Still, the big changeover hasn’t happened quite yet. Every year has its failed blockbusters, and films big and middling and little (Blumhouse, for instance) still continue. Arthouse theatres, which rely on midrange items, indie production, and foreign fare, are putting up a vigorous fight, emphasizing live events and community engagement.

Meanwhile, streaming makes film festivals and film archives more important. Festivals may host the few plays that a movie gets (as in the 35 fests which ran The Two Popes), and filmmakers, as Kent Jones remarks, are eager for their films to play on the big screen in those venues. Archives will need not only to preserve films but also make classics and current movies available in theatrical circumstances. Smart film clubs like the Chicago Film Society and our Cinematheque keep film-based screenings alive.

Before home video, few film scholars undertook the scrutiny of form and style. Those who did had to use editing machines like these. (One scholar called my study of Dreyer, not admiringly, the first Steenbeck book.) Ironically, just as an avalanche of films became available for academic study, and as tools for studying them closely became available for everyone, most researchers turned away from cinema’s aesthetic history and a film’s specific design in order to interpret their cultural contexts. There were exceptions, like Yuri Tsivian’s efforts to systematically study patterns of shot length, but they were rare.

Whatever the value of cultural critique, one result was to leave aesthetic film analysis largely to cinephiles and fans. Thankfully, the emergence of the visual essay, in the hands of tech-savvy filmmakers like kogonada and Tony Zhao and Taylor Ramos, eventually attracted academic attention. Film analysis has returned in the vehicle of the video essay, which is a stimulating, teaching-friendly format. Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I have participated in this trend through our work with Criterion and occasional video lectures linked to this site.

All this was made possible through the digital revolution, or evolution, and we should be grateful. Still, streaming filters out a lot of what we want to study. It’s clear that, for all their shortcomings, physical media were our best compromise for keeping alive the heritage of critical and historical analysis of cinema. We’ve largely lost physical motion pictures as a contemporary medium. (How many young scholars, or filmmakers for that matter, have handled a 35mm print?) Now, to lose DVDs and Blu-rays is to lose precious opportunities to understand how films work and work on us.

Thanks to all the archivists, collectors, and fellow researchers who made our research so fruitful and enjoyable in the pre-digital age.

A good overview of the streaming business at this point is “The future of entertainment,” in The Economist.

Kristin discusses the fantasy of the Celestial Multiplex with archivists Schawn Belston and Mike Pogorzelski. For examples of how to watch a film on film slowly, go here. Samples of editing-table discoveries are here and especially in the Library of Congress series that starts here. In another entry, I discuss the use of 3D in Dial M for Murder.

P.S. 24 January 2020: Then there’s this, from Facebook.

Dial M for Murder (1954).

Cine-Vienna

The Third Man (1949).

DB here:

En route to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, Kristin and I paid a visit to this wonderful city. We wandered around, stomped through museums, ate tasty food, and saw a bit of the city’s film culture.

Visiting venues

Our first stop was the Austrian Film Museum. Founded in 1964 by the avant-garde filmmaker Peter Kubelka, the Museum has built up a collection of over 30,000 films. It contains a fine film theatre with features of the “Invisible Cinema” (above) that Kubelka and Jonas Mekas set up in Anthology Film Archive many years ago.

The Museum has been a pioneer in producing outstanding books and DVD editions devoted to an eclectic array of filmmakers (James Benning, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Straub/Huillet, Joe Dante). Exceptional as well are the Museum’s online offerings of films, clips, images, and paper documents.

Our host was our old friend, the ebullient curator Christoph Huber. Here he is with his colleagues Alexandra Thiele and Jurij Meden.

We didn’t have a chance to visit the classic Stadtkino in the same neighborhood, nor did we check out the highly esteemed Austrian Film Archive. But I did mosey down to the Gartenbaukino, a big, beautiful modernistic venue.

Built as a ballroom that occasionally screened films, the Gartenbau was made a permanent cinema in 1919. In 1960, after being redesigned by Robert Kotas, it opened as a showcase for widescreen motion pictures.

It’s now said to be the biggest theatre in Austria, with over 700 seats. Note the rising curtain, said to be a rarity these days.

The Gartenbaukino is equipped to project not only digital and 35mm but also 70mm. Managing Director Norman Shetler notes that it was the first Austrian theatre to boast large-format projection (for Spartacus) and was adapted for Cinerama as well.

More recently, the Gartenbau reactivated its 70mm equipment to show The Hateful Eight. The Phillips DP70 projectors now screen wide-gauge classics like Lawrence of Arabia and The Sound of Music. Picture and sound were excellent for The Dead Don’t Die, so I bet 70mm shows here are fantastic. Like the Stadtkino, the Austrian Film Archive, and the Film Museum, the Gartenbau is a venue for the city’s annual film festival, the Viennale.

Prater, not so violet

Plenty of movies have been set in Vienna, most notably The Joyless Street, Merry-Go-Round, Letter from an Unknown Women, and Amadeus. But for movie nerds the most flagrant example is The Third Man (1949). And Vienna hasn’t forgotten what this movie did for its local landscape, not least the amusement park set within the vast and beautiful park known as the Prater.

Said to be the oldest amusement park in the world, the Prater ‘s entertainment sector contains attractions that are shiny and enjoyable old-school rides: roller coaster, loop-the-loop, tilt-a-whirl, haunted house. There are shooting galleries, ice-cream stands, and even a Madame Tussaud’s.

But of course the looming attraction is the great Ferris wheel that Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) and Harry Lime (Orson Welles) share during their ominous reunion. I’m sure I’m not the only viewer who always expects Harry to try to throw his old friend out of the cabin.

The big wheel has been declared a site of European film culture and decorated with a more or less accurate image of the coy Lime.

My ride in the wagon was gentle and elating. I tried to replicate Harry’s POV on the “ants” below, whose lives, he says, can’t matter much.

A studio-based version of the Prater featured in the now mostly lost Josef von Sternberg film, The Case of Lena Smith (1929).

Oh, yeah–we also paid a visit to a street named for one of my favorite auteurs. See below.

Next up: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

For information about Viennese film culture, thanks to Christoph Huber, his colleagues, and the indefatigable Ted Fendt. Thanks as well to Norman Shetler and two staff members at the Gartenbau cinema. Christoph, by the way, is an exceptional critic. You’ll learn from reading his essays in Cinema Scope.

Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction, and (sometimes) recovery

Kristin here:

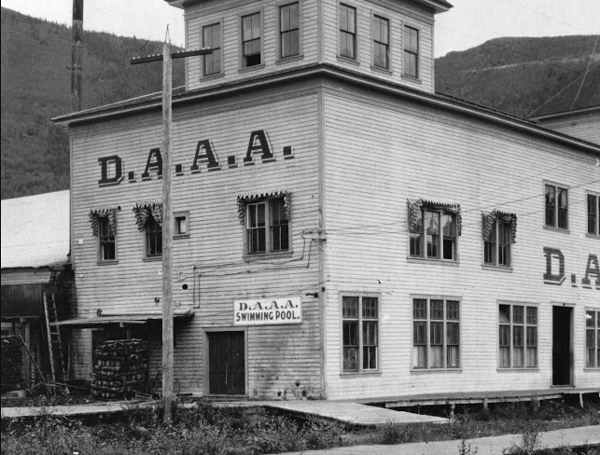

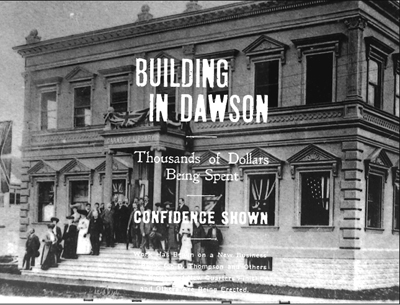

Many readers of this blog have heard of the Dawson City Film Find (hereafter DCFF), as it is called in Bill Morrison’s extraordinary documentary, Dawson City: Frozen Time. How in 1978 work on a construction site in Dawson City, Canada, led to the discovery of hundreds of reels of nitrate films packed into a swimming pool in 1929, covered over, and forgotten. How these reels turned out to be from silent films, mostly from the 1910s, many of them previously thought entirely lost.

Few will know the story in the detail with Morrison provides, nor will they know the rich historical context that he provides for the discovery and recovery of the reels. His film is not, however, simply a presentation of the DCFF. It’s about growth, loss, recovery, and destruction in several areas, all circling around Dawson City as their hub. The subtitle “Frozen Time” is a bit misleading. The reels of nitrate sealed away in the permafrost were no doubt frozen, and the temporal fictional and newsreel images they contained were lost for decades.

Morrison, however, weaves information about a variety of other subjects together in a way that makes the passage of time palpable for us. We see its effects on people and places and discover the odd, fortuitous connections among them in a dizzying fashion.

A complex film like this deserves an extended commentary, which I offer below. There are spoilers galore in it, and I would suggest seeing the film before reading this. It should appeal to anyone interested in early cinema, in North American history, and in documentaries in general. Kino Lorber has recently released Dawson City: Frozen Time on Blu-ray, with extras including eight films from the DCFF.

Easing into the past

The films-in-a-swimming-pool hook is what Morrison uses to lure us into his larger historical weave. He begins with a hint of the recovered footage, showing a baseball game which will later be revealed as the scandalous 1919 World Series where White Sox players were bribed to throw the deciding game. Then we see briefly see Morrison himself being interviewed by a talk-show host, followed by a lady in 1890s costume enthusiastically introducing a premiere screening of some of the restored films for an audience in the Palace Grand. That theatere is a modern reconstruction of the first theater built in Dawson City, used for live drama, opera, eventually films, and other forms of entertainment.

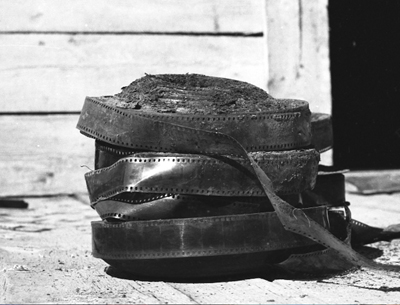

We move by stages back into history. Fifteen months before the premiere the discovery was made: a man running a back hoe turned up reels and coils of film. We meet the protagonists of the film-discovery portion of Morrison’s tale: Michael Gates, curator of Collections at Parks Canada from 1977 to 1996, and Kathy Jones-Gates, Director of the Dawson Museum from 1974 to 1986. She was Kathy Jones at the time of the discovery; this tale even has a romance, since the pair married after working together on the recovery of the buried reels. The couple describe the initial find, over still photos of mud-covered reels taken with Jones’s camera (above).

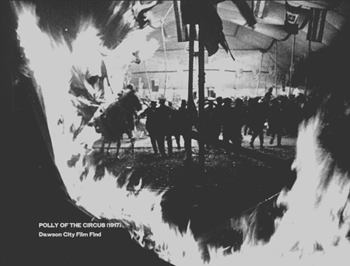

Morrison now takes us further back, to demonstrations of how nitrate film was made (with extracts from a 1937 film optimistically titled Romance of Celluloid) and how it is prone to catch fire and burn fiercely. The well-known 1897 Charity Bazaar disaster in Paris is cited, while film of a burning tent and fleeing spectators is shown. No visual record survives of the Charity Bazaar disaster, not even photographs. News accounts used engravings as illustrations. The burning tent footage is from a film released twenty years later, Polly of the Circus (1917), one of the main lost films recovered in the DCFF.

Morrison does not hide this source but superimposes a caption giving the film’s title, date, and source. This is the first time he draws upon DCFF images to evocatively represent real historical events. Later in Dawson City, the mention of an actual person, such as Gates, sending a letter will be accompanied by a montage of letter-reading moments culled from DCFF films. It’s a clever way to add a little humor and to show off a wide variety of the titles without dwelling on long clips from any one film.

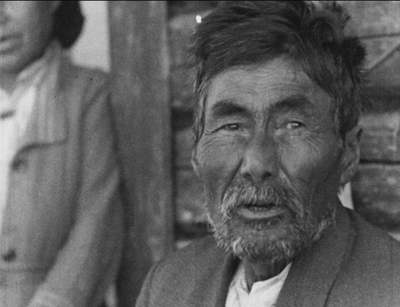

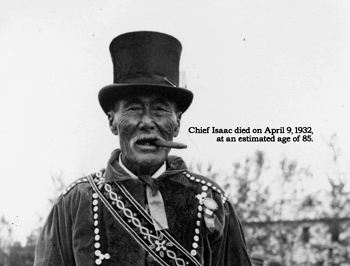

Having established the destructibility and danger of nitrate, Morrison flashes back to the earliest period portrayed in the film. Epic photographs show forested landscape. The narration, done with captions rather than voiceover, informs us that for millennia the area where the Klondike River flows into the Yukon has been the hunting grounds for one of the First Nations, the “native Hän-speaking people.” (The footage is from City of Gold, the famous 1957 Canadian documentary about Dawson City, which will become more important later in Morrison’s film.) A photo introduces Chief Isaac, leader of one subgroup of the Hän.

Nothing is said at this point, but the fate of these hunting grounds initiates one of the major threads recurring through the film, that of ecological destruction.

The third major thread is the history of Dawson City itself, which is as fascinating as the story of the buried films. In late 1896 or early 1897 one Joseph Ladue claimed 160 acres as a town site, where he sold lumber and lots to prospectors. By the summer of 1897 there were 3500 residents, and Morrison uses population figures to trace the wide swings in the town’s fortunes over the decades.

At this point the Northwest Mounted Police relocated the Häns’ village five miles downriver, and their fishing and hunting grounds were destroyed by mining.

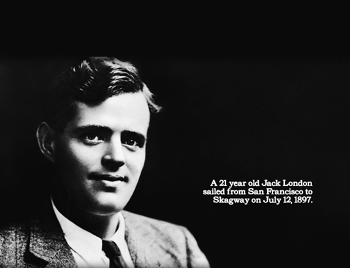

During the descriptions and facts about the huge amounts of gold coming out of the area, Morrison introduces other motifs and threads. He mentions that Jack London was among the prospectors. He was the first of several writers and theater figures who were in the Yukon, often during these early years. Most of them resurface late in the film later on, turning out to have surprising connections with the history of the cinema and each other.

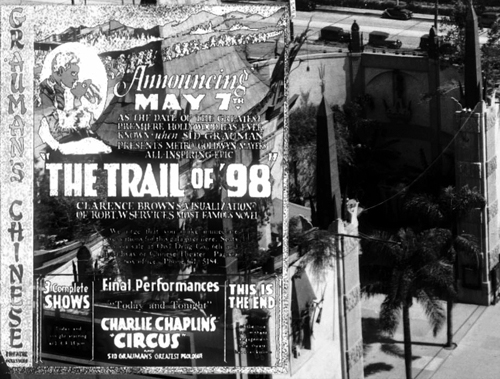

Famous entrepreneurs of later years got their starts here. Sid Grauman was a newspaper boy who eventually went on to build a theater chain, including the Egyptian and Grauman’s Chinese in Los Angeles. Ted Richard, who staged boxing matches in the Monte Carlo theater, later founded the New York Rangers and rebuilt Madison Square Garden. Alex Pantages started as a bartender, rebuilt Dawson City’s Orpheum theater after it burned to the ground in 1899 and showed traveling programs of early movies. He became one of the first major film tycoons, building a string of 70 theaters in North America.

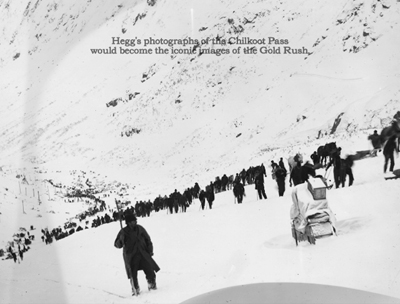

The Gold Rush frozen in time

One of the revelations of Dawson City is the work of photographer Eric Hegg, who traveled to the Yukon alongside with the hordes of hopeful prospectors. He, however, worked as a photographer, and shot thousands of images that became, as Morrison’s caption says, “the iconic images of the Gold Rush.” The one above shows the arduous and crowded journey up over the notorious Chilkoot Pass. Chaplin later staged a remarkably similar scene for The Gold Rush (1925), though whether he could have seen Hegg’s images is unclear.

By the summer of 1898, the population of Dawson City was around 40,000, and the richest claims were all taken. Businesses were set up to cater to the prospectors, including Hegg’s photographic studio. Saloons, casinos, theaters, as well as more practical boat-builders and banks sprang up. Of the two initial banks that opened branches, the Canadian Bank of Commerce is the more important to Morrison’s story, since it eventually acted as the Dawson City agent for distributors sending films to town.

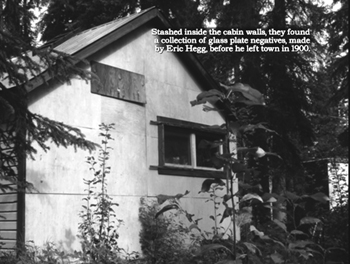

The first boom ended in the spring of 1900, after the announcement of a gold strike in Nome. Three-quarters of Dawson City’s population left, including Hegg, who left his collection of glass negatives with his partner, Ed Larss. He opened a new studio in Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush.

After his departure, Hegg disappears from Dawson City for quite some time. His work there, however, was also fortuitously rescued from oblivion. Twenty minutes from the end, we are introduced to Irene Caley and Will Crayford, who married in 1947 and decided to move a cabin from Dawson City to Rock Creek. Inside the walls they found hundreds of Hegg’s glass negatives. How they got there is unknown. Coincidentally, Hegg died in 1947, presumably unaware of the recovery of his early negatives.

The newlyweds proposed to strip the emulsion off the plates and use them to build a greenhouse. Luckily a local shopkeeper recognized their nature and gave the couple plain plates in exchange for the 93 glass ones, as well as 96 nitrate negatives. He donated the collection to the National Museum of Man in Ottawa. Arguably this rescue is as significant as the DCFF, especially given that Hegg’s photographs mostly survived in beautiful condition and constitute the best record of the Gold Rush’s first stage.

In 1949 a book of Hegg’s photographs, edited by Edith Anderson Bccker, was published as Klondike ’98.

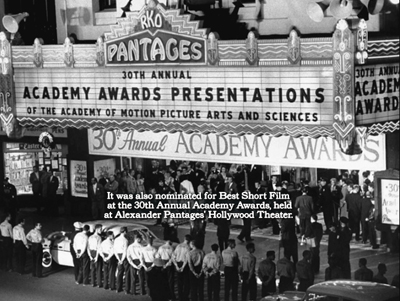

Subsequently documentary film director and producer Colin Low saw the plates in Ottawa and was inspired to make City of Gold (1957), co-directed by Wolf Koenig. City of Gold, which drew extensively on Hegg’s images, was nominated for an Oscar for Best Short Film. The awards ceremony took place at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles, built and owned by the same Alexander Pantages who launched his theatrical career in Dawson City. It would be nice to think that whoever attended that ceremony representing City of Gold saw the connection.

In 1900, Hegg moved to Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush. His post-Dawson City photographs also survive. The University of Washington’s collection contains over 2100. Its library offers a short biography and a generous sampling of those photographs here.

Weaving the threads together

Dawson City’s second boom was less spectacular but more ominous. The White Pass Railroad made Dawson City more accessible, and heavier equipment was brought in: giant hoses to break up the ground, sluices to convey the ore to a central locale, and so. Miners brought their families to live in Dawson City, with the population steadying at 9000. Various institutions, including banks, the Carnegie Library (above), and, in 1902, the huge Dawson Amateur Athletic Assocation (DAAA) building was built, with an auditorium, billiards room, bowling alley, skating rink, and swimming pool (top). I can’t summarize the whole film, but by this point Morrison has introduced enough people and places to start connecting them up in unexpected ways.

One such thread meanders like this. The celebrity motif returns at about this point, with Marjorie Rambeau (later to have a career as a character actress in movies from 1917 to 1957) performing in Dawson City with a traveling theatrical trouple. Rambeau is not significant here, but Fatty Arbuckle was also in the cast. This information is accompanied by a frame from Fatty’s Day Off (1913), a film discovered in the DCFF.

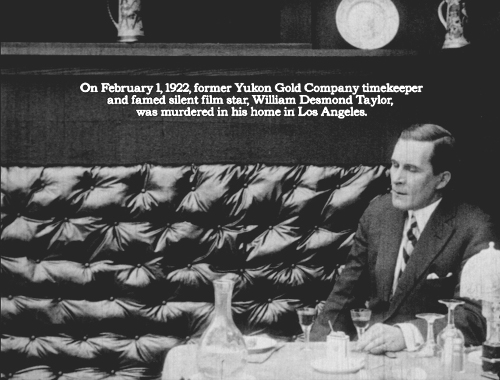

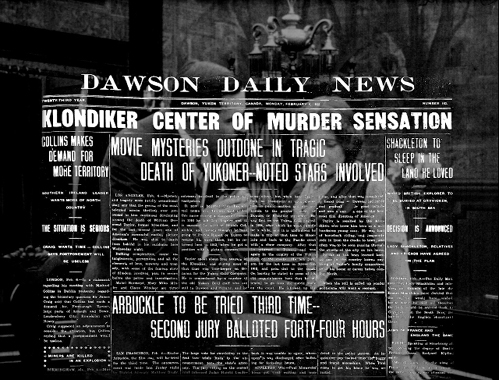

Shortly after this, we hear of two further celebrities-to-be who were in Dawson City. In 1908, poet Robert Service arrives to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce, and the following year he writes his first and best-known novel, The Trail of ’98 (1909), about the Gold Rush. From 1908 to 1912, William Desmond Taylor works as a timekeeper on a large gold-mining dredge belonging to the Yukon Gold Company, founded by Daniel and Soloman Guggenheim in 1907. These dredges handled most of the mining, throwing many out of work and causing Dawson City’s population to shrink to 3000. Huge dredges would continue to grind down the land for decades.

In 1912, Taylor left for Hollywood, where he enjoyed a short but prolific career as an actor and director, before, as Morrison foreshadows, his untimely death.

These people disappear for a time, and we learn that in 1911 the auditorium of the DAAA was turned into a movie house, the DAAA Family Theater. Other theaters in town went over to showing films. Morrison conveys this via an amusing montage of shots of people in cinema and theatrical audiences, all from DCFF films. He also provides a quick summary of disastrous nitrate fires during the early 1910s.

There follows a long interlude of coverage of the suppression of laborers and leftists during this period, in part to show off some of the newsreel footage preserved in the DAAA swimming pool. These include the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, the “Silent Parade” protesting violence against African-Americans in 1917, and the World Series scandal of 1919.This somewhat tangential though interesting foray into politics also serves to bring us forward nearly a decade.

The Solax studio fire, which also happened in 1919, provides a rather wobbly transition back to film and Dawson City as the end point of a film distribution line. The population has sunk to 1000 by this point. Since the films shown in the town during this decade were not shipped back to the distributor, many of them were stored in the basement of the Carnegie Library and continued to be through the 1920s.

A long, effective montage of shots from various DCFF films follows, beginning with people listening through doors and going through them, so that we get the impression of a giant house with dozens of people sneaking around. This is followed by shots of men attempting to embrace women and being repulsed.

The last of these is from The Kiss (1914), starring William Desmond Taylor. A caption announces his murder in 1922.

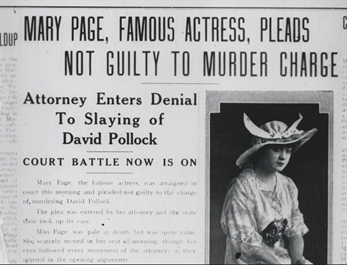

A Dawson City newspaper page announcing the murder and calling Taylor a “Klondiker” and a “Yukoner” is superimposed over another image from The Kiss. Coincidentally, just below this story is one about Arbuckle’s second murder trial ending in a hung jury. The second Taylor headline points out: “Noted Stars Involved.” One of these was Mary Miles Minter, and Morrison shows her in a film, The Little Clown (1921), from the DCFF. Minter had acted in films directed by Taylor, though this is, alas, not one of them. It was however, discovered among the DCFF films. Not one to quit there, Morrison cuts to a shot from another DCFF film, The Strange Case of Mary Page (1916), which has a plot that resembles Taylor’s case.

That two Hollywood directors should have been linked to murder cases, one as victim, one as alleged perpetrator (Arbuckle was never convicted), was certainly a gift to a director keen to stitch as many elements of his film together as possible through associations rather than straightforward historical causes.

Other connections are less elaborate. At the point where the story of Dawson City has reached the late 1920s, The Trail of ’98 (1928), an adaptation of the Robert Service novel mentioned above, is shown via a superimposed poster to be screening at Grauman’s Chinese, another chance confluence of two people who could not have crossed paths in the Yukon, since Grauman left there in 1900.

The burial

All this material has brought us to the point when the accumulating films in the library basement were transferred to the DAAA swimming pool. By 1928 Dawson City had developed a “modest season tourist industry.” Chief Isaac, whom we met early on, had become mayor of Moosehide (above). And Clifford Thomas, the man responsible for putting the film reels in the swimming pool, moved to Dawson City to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce. He also became the treasurer of the Dawson Amateur Hockey League, which played on the ice rink installed annually over the swimming pool.

In 1929 the library storage had reached capacity, and when Thomson inquired of the studios what he should do with the films, he was instructed to destroy them. At about the time, it was decided to fill in the pool so as to allow for a the skating rink to get rid of a broad bulge caused by the pool’s cover. Thomson made the decision to use the reels as fill in this conversion. Numerous other reels were burned or thrown into the Yukon River–a standard way of disposing of trash.

Morrison could have skipped back to the recovery of the films roughly fifty years later, but instead he continues the Dawson City story. First, he poetically indicates the long decades the reels spent sealed underground with a montage of women asleep, all drawn from DCFF films. The talkies finally reach Dawson City, and more silent reels are dumped or burnt. Chief Isaac dies in 1932.

Parades continue to celebrate the Gold Rush heritage, as recorded by George Black, an avid local amateur cinematographer who recorded several events shown in Dawson City. The one below took place in 1941.

By 1950, the population of Dawson City dropped under 900 people. The last theater was torn down in 1961, though the replica of the Palace Grand went up as a multi-purpose facility in 1962.

On November 15, 1966, the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation closed down its last dredge. A lengthy drone shot flies high over the tortuous, unnatural landscape that resulted from many decades of grinding down and spewing out the land (bottom). The ecological thread has not been emphasized through most of the film, but it comes to a devastating conclusion.

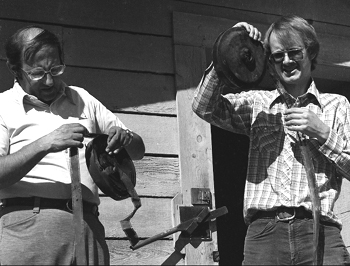

Morrison reaches the discovery of the reels in 1978, and Gates and Jones-Gates resume their story. They contact Sam Kula, Director of Audiovisual Archives, 1973-1989 at the National Archives of Canada. Kula comes to Dawson City, and he (left) and Gates (right) investigate the sodden reels of film.

Kula initially suggested donating the films to the local museum and contacted Kathy Jones. She helped dig up the films, which turned out to be far more numerous and buried far more deeply than they imagined. A newspaper item about the find led to a letter from Clifford Thomson. His explanation of how he had arranged for the films to be put in the swimming pool solved that mystery and provides us with our basic knowledge of the origins of the reels.

The rest of the film’s tale of the reels’ discovery follows how the three rescuers tried to ship the thems to the National Archives of Canada, with several truck, bus, and air services refusing to deal with nitrate film. In November of 1978 a Canadian Air Force plane delivered 506 reels to the Archives.

Morrison ends with a series of shots from various DCFF films with heavy deterioration. The thread of nitrate’s flammability and the recounting of numerous nitrate fires finds its quiet ending in the film’s lengthy final shot. A female dancer performs a modern dance that apparently expresses anguish. Blank white flashes flicker across the frame, suggesting that the dancer is being enveloped by the flames generated by nitrate film.

It is a fitting ending to a film that blends fascinating information and poetic associations in equal measures.

Some caveats

Despite my considerable admiration for Dawson City: Frozen Time, I have to take issue with some of the descriptions in this last part of the film. The narration does not point out that most of the films recovered were incomplete–not surprisingly, given how many reels were burned or otherwise destroyed. A film historian would assume that. A casual viewer would not. Similarly, there is an explicit statement that “every other copy” of these films had been lost to fire and decay. Some of these films, however, survived elsewhere, and sometimes in better copies.

The reception of the film has, through no fault of Morrison, distorted the significance of the DCFF considerably further. This evidently started with a extensive article in Vanity Fair that dubbed the DCFF “The King Tut’s Tomb of Silent-Era Cinema.” Numerous reviewers picked up this idea and repeated it, as when Kenneth Turan began his review, “It’s been called the King Tut’s Tomb of silent cinema, a celluloid find at one of the world’s far corners that dazzled the film universe.”

I cannot think of a more inapt comparison. Tutankhamun’s tomb is one of only two largely undisturbed royal tombs from the entire three-thousand-year history of ancient Egypt, and it is far and away the more important of the two. Despite the tomb’s small size in comparison with others in the Valley of the Kings, an extraordinary number of intact royal grave goods came from it–about 5000 of them (a small sample shown above). Indeed, most of what we know about ancient Egyptian royal grave goods is derived from those pieces. Tutankhamun’s tomb is, as far as we now know, unique.

In contrast, there have been many hundreds of discoveries of original silent films. One of the most notable is the Desmet collection in the Netherlands, which contained over 900 films, most of them complete and in excellent condition. Other such discoveries have ranged from single prints to large collections. Those who have discovered and restored these films are still building the international archival holdings of silent cinema. The Dawson City find is simply one important contribution to this extensive and ongoing effort.

Sam Kula himself wrote, “No-one familiar with the considerable resources now accessible through the work of film archives throughout the world would seriously argue that the Dawson Collection, or any one cache of early film, will lead to a wholesale re-write of the histories.”

The story continued

Morrison essentially ends his account when the films leave Dawson City, which is quite understandable. But the viewer might ask what happened next. There is little attention paid to the lengthy, complex procedures necessary to rescue the films from the effects of their long burial and to transfer their images onto modern negatives.

The Blu-ray release contains a nine-minute supplement, Dawson City: Postscript, which does trace some of the subsequent history of the rescued reels. We see the washing of the films in the Canadian facility, as well as the storage facilities in which the original films were stored once they had been duplicated. In the US, the Library of Congress’ 388 reels are now kept at the Packard Campus in Culpeper, Virginia, which David visited and blogged about earlier this year. Morrison maintains his history of Dawson City as well, noting that in the summer of 1979 the town suffered a disastrous flood and that the premiere of some of the restored films took place shortly after that, on September 1.

At first glance, the Dawson find seems to have been handled in a casual way, with local administrators who were not film archivists digging up reels with shovels and handling them in a way that today would seem reckless. Some have assumed that considerable unnecessary damage was done to the films after their discovery. Yet no written account of the whole affair has yet been published.

I asked our friend Paolo Cherchi Usai, Senior Curator of the Moving Image Department of the George Eastman Museum, for his opinion. He kindly gave me his account of the rescue process, which suggests that the original participants in Dawson City did the best they could under extremely challenging circumstances.

As Paolo wrote in introducing his description, “Please note that what I know is just a matter of oral history — things I heard from the protagonists and witnesses of the events, several years ago. Also, I have not yet seen Bill Morrison’s film.” Others may be able to correct or expand upon some of what Paolo has written. Still, it provides a very informative and useful summary of the rescue process. (I have identified the people mentioned below in brackets. The undated image of a silent-era drying drum is the only image in this entry that is not from Dawson City: Frozen Time.)

In my opinion, the rescue of the Dawson City was a miracle of improvisation and initiative achieved under extremely difficult and often adverse circumstances (see below). In all fairness, I can’t call it a disaster (I can think of other occurrences in my field where that term could rightfully apply). In hindsight, it is all too easy to point out the mistakes made in the process; back in 1978, archival practices were less sophisticated than they are now.

The comparison with Tutankhamen’s tomb is indeed excessive in regard to the aesthetic importance of the films; there is no exaggeration, however, in pointing out the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the discovery, and the steps taken in a very short period of time. You don’t find silent films in a frozen swimming pool that often. When you do, the historical value of the artifacts is not an issue. You want to save all the objects, and then find out their worth. That’s the main reason for the mystique surrounding the discovery; that’s also why I heard about it as soon as I started studying silent film history and film preservation.

It must be pointed out at the outset that the film reels found in the layer right under the permafrost that covered the swimming pool were already decomposed. Nothing could be done to save those prints. It is my understanding that preliminary identification work was undertaken at Dawson City, and that such work was implemented in a cold area. It may be argued that there was no particular reason why this work had to be done there instead than later in Ottawa, but that’s what happened. The late Sam Kula, one of the protagonists (together with Bill O’Farrell [Head of Film Preservation, 1975-2002, National Archives of Canada] and Paul Spehr [former Secretary for the Motion Picture Section of the Library of Congress and Assistant Chief of the Motion Picture Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress], among others) of this story, may have been able to explain this.

The reels gradually thawed in at least three stages, during their transfer to a) an air-force base near Dawson City; b) the National Archives in Ottawa; c) the Library of Congress. The thawing could perhaps have been minimized (if not avoided altogether) if the material had been processed in a refrigerated area from beginning to end. This didn’t happen. The nitrate unit at the National Archives of Canada had been shut down to make room for operations on safety materials, and no special precaution could apparently be taken while dividing the collection in two main groups: the Canadian newsreels to be kept at the National Archives, and the American films to be sent to the Library of Congress.

Bureaucracy was the nemesis of the Dawson City rescue project. The only way Bill O’Farrell could bypass it was for him to personally transport the reels of American films from Canada to the US by car, in a large station wagon, from Ottawa to Suitland, Maryland. His heroic feat — perhaps the most important of his career — would have hardly been possible today. He had no choice; following the usual protocol would have taken months, and the emulsion on the prints would have melted completely. Paul Spehr did his part by having the films accepted into the collection in record time, without following the standard acquisition procedures at the LoC. O’Farrell had alerted Spehr that “there is water in the cans” — this is what Spehr heard on the phone, and he expected this to be the case when the material arrived. It’s not that the reels were drenched in a pool of water in each can; but there was water. The prints had thawed.

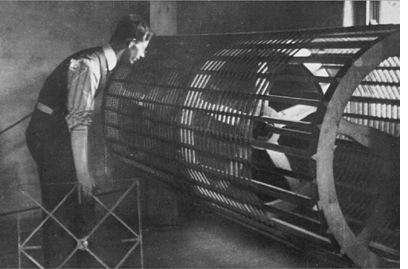

In that situation, it was deemed necessary to do something about that water. The technical staff at LoC designed and built  a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

To reiterate the point, the whole story has always been described to me as an emergency rescue performed at breakneck speed, a chain of events where careful advance planning could not be part of the picture. The only way to avoid the partial loss of the emulsion would have been to undertake the entire process in a much colder working area. By the time the reels reached Dayton, however, it would have already been too late to apply such a solution, even if a low-temperature processing area had been available. All that could be done at LoC was to “stabilize” the material long enough for it to go through the printers for duplication.

So that’s that. I hasten to add that my recollections raise a number of questions to which I have no answer.

Our thanks to Paolo for filling in so much of the rest of the story of the Dawson City Film Find.

Thanks to Jonathan Hertzberg of Kino Lorber for his assistance.

The Sam Kula quotation comes from his account of the DCFF rescue, “Rescued from the Permafrost: The Dawson Collection of Motion Pictures,” which can be found on Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archvists #8 (Summer 1979), reprinted from American Film (July 1979).

A brief description of the “Public Archives of Canada/Dawson City Collection” is on the Library of Congress “Motion Pictures in the Library of Congress” page.