Archive for the 'Directors: Walsh' Category

Solo in Bologna

Kristin here:

Two days before David and I were to set out for Bologna and its annual Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, back pain struck him. He decided not to go, and so our coverage this year will be briefer. I struggled to see as much as possible, but if anything, the program was even more packed than last year.

The auteurs

The main threads included four directors who are of historical interest. Raoul Walsh was the main attraction, with emphasis less on familiar classics like Roaring Twenties and White Heat and more on hard-to-see items like Me and My Gal and other early 1930s films. Lois Weber, the first important female director in American cinema, was represented with as complete a retrospective as possible, including fragments from features not otherwise extant. Jean Grémillon, one of the less famous French prestige directors during the 1930s and 1940s, was extensively represented. And there was Ivan Pyriev (or Pyr’ev, going by the program notes’ spelling), most famous as one of the main proponents of the “kholkoz [collective farm] musicals” of the last 1930s and 1940s.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

The Civil Servant (or The State Functionary, 1931) was a full-blown, skillful leap into Montage, with an prologue of trains coming into Moscow, shot with canted framings, low angles, and quick cuts with trains moving left, then right. The rest is a satire on bureaucracy within the national railroad system—ostensibly set during the Civil War but clearly a contemporary story. It’s broad in its humor, and it has the obvious typage in the choice of actors, the wide-angle lenses that the Montage filmmakers explored in the late 1920s, and other scenes of quick cutting with jarring reversals of directions.

Official dislike of The Civil Servant kept Pyriev from directing again for three years. Turning his back on Montage, he went to the other extreme, helping to develop the kholkoz (collective-farm) musical and making some of its liveliest, most entertaining, and most enthusiastic examples of that genre. His Traktoristi of 1939 was not shown during the festival, but one that I hadn’t seen, Swineherd and Shepherd (1941), is fully its equal. From the moment the film begins, with the camera madly tracking backward through a birch forest as the heroine runs full tilt after it, singing joyously to the masses of pigs that emerge from corrals and gallop along with her, the spectator realizes that this film will be exactly what one wants and expects from Pyriev.

A later entry in the genre, The Cossacks of the Kuban (1950), was even better, and I can see why it is Olaf’s favorite. The opening vistas of immense wheat fields, gradually moving to scenes with tiny figures and finally to ranks of harvesting machines and trucks achieves a genuine grandeur, aided considerably by the fact that by this point Pyriev is working in color. The story goes beyond the simple stock figures of some of the earlier musicals, with a stubborn Cossack who heads one collective farm nearly missing his chance at romance with a widow who heads a rival farm.

Overall, I like these films a little better than those of his more famous colleague in the creation of buoyant musicals, Grigori Alexandrov. Yet it has to be mentioned that there is a certain underlying unease in being entertained by films that created hugely idealized images of life on collective farms. In reality many peasants were starving, and few were working with such cheerful enthusiasm to increase production for the sake of the great Soviet state. One might rationalize this dissonance by thinking that Pyriev was perhaps making fun of his subject with over-the-top dialogue and musical numbers. Yet surely to many audiences at the time, this was escapist entertainment, and urban audiences may have had little sense of the blatant inaccuracy of the portrayals of the countryside.

Two more straightforward dramas, The Party Card (1936, below) and The District Secretary (1942), a war story, were more conventional Socialist Realist works, skillfully done but lacking the appeal of Pyriev’s lighter films.

It was sad to see the one post-Stalinist film from Pyriev’s late career, his adaptation of The Idiot (1958). A sumptuous production, again in color, it consisted almost entirely of overblown confrontations among characters. The actors shout all their lines at each other with almost no variation in the dramatic tone, with everything underlined by an amazingly intrusive musical score.

I saw only a few of the Walsh films, since they frequently conflicted with the Pyrievs and Grémillons and just about everything else on offer. To me, the director was a bit oversold. Peter von Bagh’s introduction to the catalog says, “Unjustly, Raoul Walsh, although blessed with so much cinephilic worship, is usually placed a few notches below his more revered colleagues Ford and Hawks. Now he will have a chance to be upgraded, in our continuing series featuring extensive screenings from Walsh’s silent period through his very rare early sound films.” Perhaps Walsh will go up a notch in people’s estimations—the screenings of his films were certainly very popular—but not, I think, the few notches it would take to place him alongside these two other masters. I enjoyed Me and My Gal, a rare 1932 comedy in which Spencer Tracy and a very young Joan Bennett adeptly exchange snappy patter, yet it occurred to me more than once during the screening that Twentieth Century (1934) is a much funnier film.

The Big Trail, shone in its original wide-screen Grandeur format on the giant Arlecchino screen, was better than I expected. Walsh was given enormous resources to tell the story of a large wagon train making its way to Oregon from the Mississippi. He showed off the crowds of wagons, cattle, and people by the simple expedient of raising the camera height so that most of the screen’s height became a tapestry of people stretching into the distance, all going about their business while the main dramatic action in the foreground occurred. This often involved a very young John Wayne, whose occasional awkward delivery of lines managed somehow to fit with his character.

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Few of Walsh’s pre-1920s films survive, but those few were shown. I skipped the wonderful Regeneration, having seen it multiple times, but I caught The Mystery of the Hindu Image, notable mainly for Walsh’s own performance as the detective, and Pillars of Society, a somewhat stodgy adaptation of the Ibsen play.

I can’t say much about the Weber films, since they were consistently in conflict with screenings of films by the other main auteurs. I regret having skipped one Pyriev film, Six O’clock in the Evening after the War (1944) to see Shoes (1916), which had been touted as one of the director’s best. It proved a considerable disappointment, stuffed with expository intertitles that often simply described what we could already see from the action in the images. This may have been because Weber’s “discovery,” Mary McLaren, was so inexpressive. She almost constantly wore the same expression of resigned sadness at her family’s grinding poverty, varying it occasionally with a look of annoyance at her father’s shiftless behavior. I tried to steer people to The Blot, which is probably Weber’s masterpiece among the surviving films.

It was fairly easy to see most of the Grémillon titles, because a number of them were repeated in the course of the week. I enjoyed Maldone, which I had seen once long ago. Its story involves a runaway heir to a large estate who has run away as a young man and now, in late middle age, works on a canal barge. Infatuated with a beautiful gypsy and spurned by her, he returns to claim his inheritance, only to be disgusted by gentrified life. Like Pyriev, Grémillon came late to one of the commercial avant-garde movements of the 1920s, French Impressionism. He uses the subjective camera effects and the rhythmic editing in a straightforward way, with little of the flashiness of a L’Herbier or a Gance. Maldone and his subsequent film, Gardiens des phare (1929), shown at the festival in a tinted Japanese print, remind me of perhaps the best filmmaker of the Impressionist movement, Jean Epstein.

This legacy might logically have led Grémillon into the Poetic Realism of France in the 1930s. Unfortunately his first sound film, La petite Lise (1930), which might be said to fit into that tradition, was not shown. After seeing several of the films on offer this year, I still think it may be his masterpiece. (We talk about it briefly in the section on early sound cinema in Film History: An Introduction.) Though some might argue that he has at least one foot in that tradition, his work is perhaps closer to what the Cahiers du cinéma critics later dubbed the Cinema of Quality.

As for the others I caught: L’étrange Monsieur Victor (1938, dominated by Raimu as a successful merchant who is not all he seems), Remorques(1939-41, perhaps Grémillon’s best-known film, re-teaming the favorite French couple of the 1930s, Jean Gabin and Michele Morgan), and Pattes blanches (literally, “White putties,” 1948). I enjoyed them all, and yet there was no sense of discovering an overlooked genius. Best of the sound features for me was Pattes blanches, which tempered Grémillon’s taste for melodrama with a hint of surrealism. The obsessive young wastrel Maurice (played by a very young Michel Bouquet), the gamine hunchback maid who falls in love with the reclusive and menacing local nobleman, and the nobleman himself, invariably bizarrely clad in his white puttees, help give the film a fascination that the others, for me at least, lack.

The themes

There were other threads oriented by genre or topic or period. These I sampled when it was possible to insert them into my schedule. One of these was “After the Crash: Cinema and the 1929 Crisis,” which included an intriguing potpourri of documentaries and fiction films from several countries and political stances, from Borzage’s A Man’s Castle to two short films by Communist-leaning Slatan Dudow, director of Kuhle Wampe. Because of my interest in international cinema styles of the late 1920s and early 1930s, I went to Pál Fejös’s Sonnenstrahl (“Sun Rays,” 1933) was shown in the festival’s first time slot, 2:30 on Saturday afternoon. It thus competed with the first showing of the Grandeur version of The Big Trail and the first program of the “Cento anni fa” set of 96 films from 1912, but such is Bologna’s lavish scheduling.

Fejös, a Hungarian, made films in Hollywood, France, Denmark, Sweden, and a number of other countries. Sonnenstrahl, with its romance between German actor Gustav Fröhlich and French leading lady Annabella, is basically a reworking of the director’s best-known film, Lonesome (1928), with touches of 7th Heaven (Borzage, 1927), redone for the Depression era. It’s a pleasant enough piece, though not up to Fejös’s best work of the 1920s. Again, the program claims to too much for the filmmaker by saying that some historians consider him “as one of the cinema’s great poets, along with Murnau and Borzage.”

The Depression program also included a surprisingly good early sound film by Julien Duvivier, David Golder (1931, above). It’s the story of a wealthy businessman, played by Harry Baur, who discovers that his wife and daughter love him only for his money. How he could have lived this long with them without realizing this is perhaps a weakness in the plot, but from the start Duvivier showed a remarkable assurance in framing, cutting, and camera movement that was continually in evidence. Sets by the great Lazare Meerson also enhanced the style.

Baur also starred as Jean Valjean in Raymond Bernard’s 1934 three-part Les Misérables. I skipped the screenings, since the film is available in a Criterion boxed set (along with Bernard’s remarkable 1932 anti-war film Wooden Crosses). The Bernard film was part of the “Ritrovati and Restaurati” thread. The presence of Baur in both David Golder and Les Misérables led to the Depression and Ritorvati threads to weave together to produce a third: “Homage to Harry Baur.”

The only other entry in this brief thematic collection was Duvivier’s La tête d’un homme (1933), the third film based on a novel by Georges Simenon. Baur stars as Commissioner Maigret, and Valery Inkijinoff (known largely as the hero of Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia/The Heir of Ghengis Khan, though he acted in numerous other films as well) plays the doomed, obsessive villain, Radek. The film is not as accomplished as David Golder, but it’s an entertaining little thriller with some novel twists. Early in the film the murder is revealed, and we know from the start the Radek committed it. The duel between him and Maigret becomes the focus of the action. Moreover, the very first scene introduces a thoroughly unlikeable fellow who initially seems to be the villain, a womanizing cad who lives by gambling and other unsavory activities, yet who himself eventually comes to be tormented and threatened by Radek.

Another intriguing thread was “Japan Speaks Out! The First Talkies from the Land of the Rising Sun.” Ordinarily I would have tried to see most of these, but again they conflicted with the auteur threads I was trying to follow. I did make it a point to see Mizoguchi’s first sound film, Hometown (1930, above), since it’s one of the hardest to see. A part talkie built around a famous Japanese tenor and opera singer, it was more an historical curiosity than a satisfying film. I reluctantly skipped Heinosuke Gosho’s delightful Madame and Wife (aka The Neighbor’s Wife and Mine), the first really successful Japanese talkie, having seen it a number of times. On David’s and Tony Raynes’ advice, I caught Yasujiro Shimazu’s First Steps Ashore, a romantic tale inspired by Von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York. It didn’t quite match the original (as what could?) but was an entertaining tale well acted by the two leads. The first frame below reflects something of the style of Docks of New York, but the second, more typical of the film, is pure Shochiku.

The organizers of Il Cinema Ritrovato have declared that they will continue to show films on 35mm as long as possible. Most of the screenings that I attended were indeed on film. There’s no doubt that the move to digital restoration became dramatically more apparent this year. Nearly all of the 10 pm screenings on the Piazza Maggiore were digital copies, including Lawrence of Arabia, Lola, La grande illusion, and Prix de beauté. David and I don’t usually go to these screenings, since we invariably want to see films in the 9 or 9:30 AM time slots and don’t want to fall asleep during them. But I did catch two digital restorations shown earlier in the evening in the Arlecchino.

The first, Voyage to Italy, was flawless and sharp—perhaps a little too sharp. I liked the film much better than the first time I saw it, maybe because I understood better the claims that are made for it as a forerunner of the art cinema of the 1960s, with the aimless, confused couple presaging the characters of directors like Antonioni.

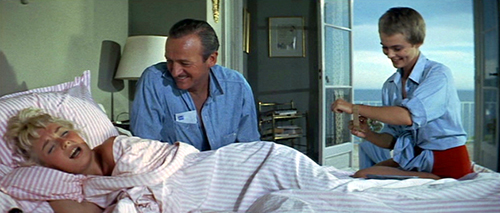

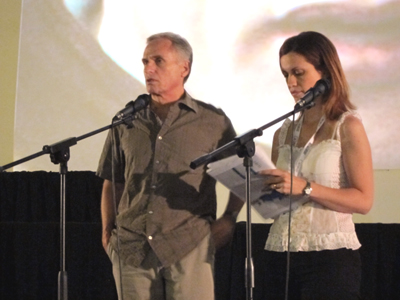

Perhaps the high point of my week, though, was an entry in an ongoing thread at the festival, “Searching for Colour in Films.” There were many films in this category, which was broken down into the silent and sound eras. Bonjour Tristesse may well be my favorite Otto Preminger film. Our old friend Grover Crisp (above, with interpreter) returned to Bologna to introduce it in a digital restoration, but one which, he assured us, retained the grain of the original film. It was certainly a beautiful copy and looked great on the Arlecchino screen. (The frames at the top and bottom of this entry were taken from a 35mm copy, not a DVD or the new restoration.)

Il Cinema Ritrovato grows more popular each year. A number of our friends from other festivals and alumni of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s film studies program attended for the first time and vowed to return. Perhaps a sign that the event is gaining real prominence internationally was the fact that Indiewire columnist Meredith Brody also made her first visit. She conveys the impressions of a newbie in a series of posts: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 4, and Day 5. For many images of the festival guests and screenings, see the official website.

David analyzes one Hitchcock-like scene in The Party Card in his On the History of Film Style.

July 9: Thanks to Ivo Blom for correcting my spelling of Harry Baur’s name.