Archive for December 2008

The ten best films of . . . 1918

Kristin here–

We ended 2007 with a salute to the 90th anniversary of the solidification of the classical Hollywood filmmaking system. 1917 was not only the year when all the guidelines—continuity editing, three-point lighting, and unified story structure—gelled in American cinema. It was also one of those years (like 1913, 1927, and 1939) when a burst of creativity took place internationally. For those years, it’s hard to keep one’s greats list to ten.

Enough of you enjoyed that entry that we thought we would come up with another list to end 2008. For some reason, 1918 doesn’t yield the plethora of great films that obviously should go on such a list. Maybe it’s the sheer accident of preservation. After a string of masterpieces from Douglas Fairbanks in 1917, there seems to be a dearth of his films extant from the following year. Some filmmakers, like Cecil B. De Mille, simply released fewer films in 1918. And of course, some masterpieces may still lie gathering dust on archive shelves, waiting to be discovered.

Still, great films were made that year, some familiar—some that should be better known. Some are available on DVD, and some are excellent candidates for release by some of the enterprising companies like Kino International, Image Entertainment, and Flicker Alley.

1. The list isn’t in rank order, but for me the outstanding film of 1918 is Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru, better known to most as The Outlaw and His Wife, by Victor Sjöström. This tale of an enduring love between a man  hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

This year Kino also brought out a disc with the dynamite double bill of two tragedies Ingeborg Holm (1913) and Terje Vigen (1916). David and I have both written about the staging in Ingeborg Holm, and David has had much to say on tableau staging in 1910s cinema. Watch these three films, and you will understand why we consider Sjöström perhaps the great director of the decade. It’s a shame that more of his films are not available yet in the U.S. Buy copies of these, and maybe Kino will bring more of them out.

2. Another master of this era, Louis Feuillade, made a sequel to his Judex (1916): La Nouvelle Mission de Judex. David discusses both in the second chapter of his Figures Traced in Light. Although Judex is available on DVD, so far the second serial is not.

3. I suspect that Hearts of the World is one of those D. W. Griffith features that a lot of film enthusiasts have heard of but not seen. Remarkably, it’s not available on DVD. (Keep your old laserdisc if you’ve got one!) I have to admit, it’s not one of my favorite Griffiths, though it does have a charming performance by Dorothy Gish and contains scenes that were actually shot near the front lines in France.

4. Ernst Lubitsch was making the transition from shorts to features in 1917 and 1918. While Carmen is historically important for his development toward his mature style, most audiences these days would probably find Ich möchte kein Mann sein (“I don’t want to be a man”) more entertaining. It’s a comedy about an independent young lady who escapes her strict governess and guardian by going out on the town disguised as a man—in the process joining her guardian without his recognizing her (see the frame at the bottom). Its star, Ossi Oswalda, was an outgoing blonde dynamo, quite different from Pola Negri, whom Lubitsch turned to for his later historical epics.

Kino has made several of Lubitsch’s films from the late 1910s and early 1920s available. Ich möchte kein Mann sein can be bought on a single disc with Die Austerinprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” 1919), another Oswalda comedy. I’d recommend getting it as part of the larger “Lubitsch in Berlin” set, which also includes the hilariously imaginative Die Puppe (“The Doll,” 1919), the Expressionist satire Die Bergkatze (“The Wildcat,” with Negri in her one comic role for Lubitsch, 1921), an Arabian-nights epic Sumurun (1920), and the historical epic Anna Boleyn (1921), as well as a documentary on Lubitsch.

5. In 1918 Cecil B. De Mille made a film that would change his career’s trajectory: Old Wives for New. At the  time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

6. Hell Bent, by John Ford, was long thought to be among his many lost westerns from the early years of his career. It was rediscovered in the Czechoslovakian archive and shown years ago in Pordenone at the Il Giornate del Cinema Muto festival. I must confess that I don’t remember it very well, apart from one spectacular tilt downwards as a stagecoach (?) races down a winding mountain road. Not as good as Straight Shooting, and Hell Bent survives in rocky shape (perhaps too much so for DVD release), but Ford films of this era are so rare that I’ve listed this one.

7. Like Lubitsch, in the late 1910s Charlie Chaplin was making a gradual transition from shorts to features. In 1916 and 1917 he released a remarkable string of Mutual two-reelers, from The Rink (December 1916) to The Adventurer (October 1917). In 1918, with A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms, he increased the films’ length to three reels, or roughly 45 minutes, and started releasing through First National. He also cut back on the number of titles released each year. Apart from a brief promotional film for war bonds, A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms were his only 1918 releases. Which is better? I suppose most people would say Shoulder Arms. To me it’s a toss-up.

8. David and I started attending Il Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1986, when the festival was launching its great series of national retrospectives. In quick succession, these retrospectives revealed three hitherto virtually unknown but major auteurs of the 1910s: the Swede, Georg af Klercker, in 1986; the Russian, Evgeni Bauer, in 1989; and the German Franz Hofer, in 1990. Bauer’s career ended with his death in 1917. Hofer remained active until the early 1930s. The Giornate’s German program contained only six of his films, however, and those from the 1913-1915 period. I suspect that means the later teens titles are lost.

In contrast, nearly all of af Klercker’s films survive, mostly in the original negatives. The prints shown at Pordenone were stunning. The director had a great eye for settings, using beaded curtains, mirrors, and other elements to considerable effect. He made three films in 1918: Fyrvaktarens dotter, Nobelpristagaren,Nattliga toner, the first two of which were shown in the 1986 retrospective.

Unfortunately since then the films have not been made widely available, either in prints or on DVD. Having not seen the two titles just mentioned since 1986, I can’t say that I remember them well enough to judge between them. So I’ll just leave all three films here, along with the advice to seize any chance you may get to see those or af Klercker’s other films.

(Given how little known af Klercker’s work is outside Sweden, I should point out a major English-language piece on the director’s style, Astrid Söderbergh Widding’s “Towards Classical Narration? Georg af Klercker in Context,” in editors John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930 [Sydney: John Libbey, 1999].)

9. Stella Maris, directed by Marshall Neilan, was the first of five features Mary Pickford starred in in 1918. Its reputation lies mainly in the fact that Pickford played a double role, the bed-bound but lovely title character, and an ugly, slightly deformed orphan. In its outline, the story sounds abstract and overly symmetrical. Stella Maris’s relatives shut her off from all ugliness in the world, keeping her in happy innocence well into her teens. Unity, the orphan, has known nothing but deprivation. As Stella comes to glimpse the grim side of life, Unity is adopted and has glimpses of the beauties enjoyed by the rich. Both become miserable as a result.

The overall implication is pretty grim. Stella’s world is initially wonderful only because everyone lies to her. She becomes embittered when she finally discovers this. At the heart of the tale is the deception that life is beautiful. Unity, who has not been deceived, knows better from the start. Even one brief reference to the war, as a troupe of soldiers passes by the estate where Stella lives, makes it seem tragic—this in a film that came out about two months after the U.S. had entered World War I.

The balance between the two characters is made less artificial than it might sound by Pickford’s extraordinary performance—not so much as Stella, who is a rather passive version of the typical Pickford persona, but as Unity. The waif’s frequent disappointments and outright suffering create a strong effect that shadows even the quasi-happy ending. It’s a beautifully made film as well, with the use of glamorous backlight (as in the image at the top of this entry). Stella Maris is available on DVD from Image.

10. I have been hard put to find a feature to round out the list, so I’m substituting a group of shorts. They’re not masterpieces by any means, but each displays the talents of a great silent comic well on the way toward his most fruitful period.

There’s no single great film to mark Harold Lloyd’s transition, but during 1918 he was developing his “glasses” character. He had had a modest success with his “Lonesome Luke” series from 1915 to 1917, where he essentially created a variant of Chaplin. In September, 1917, Lloyd first wore his famous black, lens-less glasses in Over the Fence. His early one-reelers wearing those glasses were still sheer slapstick, with little of the characterization that he would later develop to go with his new look. Arguably it was 1919 or even 1920 before he had fully nailed that persona. Still, during 1918 one can see him groping toward the formula.

Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection” volumes contain four films from that year, all co-starring Lloyd’s  regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

1917 and 1918 formed the high point of the string of comic shorts directed by Fatty Arbuckle, in which he also co-starred with Buster Keaton and Al St. John. When Keaton went solo, he proved to be a far better director than Arbuckle. Arbuckle tended to simply face his camera perpendicularly toward the back of the set for every shot, just cutting to whatever scale of framing would best display a gag. Here it’s the perfectly timed and executed gags that dazzle, and the films are often hilarious. In 1918, the team made The Bell Boy, Moonshine, Out West, Good Night Nurse, and The Cook. The latter shows off Arbuckle and Keaton’s dexterity at juggling props and Fatty’s surprising grace, as when he improvises a Salome dance with a head of lettuce standing in for that of John the Baptist!

The 13 surviving Arbuckle-Keaton films (some with missing bits) are available on Eureka’s definitive boxed set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films.” (That’s Region 2 format only, and available from Amazon UK.) Image’s “The Best Arbuckle Keaton Collection” has 12 films, missing only the more recently rediscovered The Cook. Image brought out The Cook on a disc with Arbuckle’s A Reckless Romeo (1917, sans Keaton). Kino’s two separately available volumes of “Arbuckle & Keaton” (here and here) contain 10 shorts total, again missing The Cook.

Apart from all these films, it’s worth noting that in the world of animation, 1918 saw the release of Winsor McCay’s fourth cartoon, The Sinking of the Lusitania, and Dave Fleischer’s first, Out of the Inkwell, which launched the enduring series.

Next year, 1919. Happy 2009 to all our readers!

A glance at blows

DB here:

Perhaps it came from watching the Odessa Steps sequence, projected in hazy 8mm, on the bedroom wall during my teenage years. Or maybe it was seeing my first Bruce Lee movie in the early 1970s. In any case, at some point I became a connoisseur of action sequences. Eventually I was able to indulge this tendency by writing about Eisenstein, but also by studying Asian action film.

I became convinced that martial arts movies from Japan and Hong Kong constituted as important a contribution to film aesthetics as did the Soviet Montage movement. Through shot-by-shot and even frame-by-frame analysis, I tried to show that these movies were exploring ways that cinema could arouse us kinesthetically. Their use of composition, cutting, color, music, and physical motion was not only beautiful but also engaging on levels that we didn’t fully understand. (Perhaps now that we know about mirror neurons we’re in a better position.) Certain turns in the action make us laugh, but not in derision. We laugh in jubilation, and sometimes out of admiration for sheer audacity. At their most ambitious, these films achieved the physical-emotional ecstasy that Eisenstein found in sharply executed “expressive movement.”

A jolting blur

So it was with a definite sadness that I watched, from the 1980s onward, the tendency of American filmmakers to give up on rendering physical movement with full force. Action sequences became jumbled arrays of short shots and bumpy framings. The clarity and grace of motion seen in classic Westerns and comedies, in the work of Keaton and Lloyd and Ford and Don Siegel and Anthony Mann, gave way to spasmodic fights and geographically challenged chases. At first, the chief perpetrators were Roger Spottiswoode and Michael Bay. Now it’s nearly everybody, and journalistic critics have recognized that this lumpy style has become the norm, even in the generally admired Bourne entries.

Classic Hong Kong and Japanese action scenes were “expressionistic” in the sense that their larger-than-life balletics and aerobatics amplified recognizable (if extreme) possibilities of the human body. The result was a carnal cinema, in which shooting and cutting aimed to enlarge and prolong graceful movement. By contrast, Hollywood action scenes became “impressionistic,” rendering a combat or pursuit as a blurred confusion. We got a flurry of cuts calibrated not in relation to each other or to the action, but instead suggesting a vast busyness. Here camerawork and editing didn’t serve the specificity of the action but overwhelmed, even buried it.

Why is the filmmaker reluctant to face the concrete, moment-by-moment facts of the fight? Maybe it’s fear of censorship, or maybe it’s just lack of interest in physical processes. By contrast, most of the great Hong Kong action directors have been themselves martial artists. To them a fight is a suite of tangible actions and micro-actions. Or maybe the new muddier approach seeks to hide the fact that the action is preposterous. Western audiences don’t like far-fetched action that isn’t comic, but the new action picture is touted as a return to realism. Bond is tough and Jason Bourne’s adventures are “gritty.” Yet realism comes at a price, in this case the loss of bodily movements elegant in their efficiency.

Defenders of the impressionistic approach say that it renders “what the action feels like.” But that would entail that the action feels fast and confusing. To whom? Maybe to a duffer like me, if I were dropped into the melee, but not to trained fighters. Bourne isn’t confused: his senses are alert, and his gestures are economical and smooth. So why render the scene as chaotic and show his gestures in jerky cuts? Any fighter overcome by the sensory overload handed to us would lose big.

The classic Asian approach also tries to make us experience how the action feels, but it starts by taking pains to show how it looks. Hong Kong filmmakers constructed a sequence on a firm foundation, and that meant making each shot impossible to misunderstand. They then built those crisp images into what I called the pause/ burst/ pause structure. This simple pattern, capable of great variation. creates a staccato exhilaration.

How? Here’s a first approximation. The stylistic orchestration of the fight trips off optical, auditory, and muscular responses in our bodies, while the pauses give the movement a chance to echo. Instead of a vague busyness, a sense that something really frantic but imprecise is happening, we get a marked rhythm alternating an exact visceral impact with tingling aftereffects. Eisenstein believed that when we see an expressive movement, we reflexively repeat that movement, albeit in weakened form. After one of these sequences you feel tired, but in a good way. We’ve been given a taste of what physical mastery feels like.

Transport

Compare the action scenes of the first Transporter film (2002) with those of Transporter 3 of this year. The first, directed by Hong Kong veteran Yuen Kwai (aka Corey Yuen), isn’t a patch on his best home-ground work (Ninja in the Dragon’s Den, Righting Wrongs, Yes, Madam!, Saviour of the Soul), but the bigger budget provided by Luc Besson gave him a chance to put Jason Statham through some energetic paces, particularly on the oil-slicked floor of a bus garage.

Yuen, a director who sacrifices even dialogue to pictorial rhythm, is fond of percussive insert shots (e.g., the garage scene’s crackling close-ups of Statham snapping bike pedals onto his shoes) and steep, tight angles that spread all of a fight’s players into a diagrammatic composition.

But Transporter 3, choreographed but not directed by Yuen, has buried precise, bone-whacking action under freeze-frames, superimpositions, ramping, color shifts, and other Tony Scott doodling.

Something more sober but just as nerveless is at work in Quantum of Solace. Here the jabbing handheld work of the Bourne pictures has been replaced by steadier framing and smoother traveling shots, but the hyperkinetic, what-did-I-just-see cutting is still there. Again, I think that the filmmakers are worried about the implausibility of the action scenes and so muffles them by a haphazard handling.

Back to basics

Most discouraging has been the way that many Asian filmmakers have taken up the Hollywood approach. Today’s standard Hong Kong action picture is likely to be as visually and kinetically disorganized as the Hollywood product. That’s why I can recommend, as a palate-cleanser if nothing else, Ryoo Sung-wan’s City of Violence (2006), a Korean film recently made available on DVD from Dragon Dynasty.

It is unapologetically formulaic. Pals in a teenage gang grow up to be gangsters and cops. Our protagonist, a big-city cop, returns to the hometown to discover that the weakest of the old crew has become a sadistic overlord. Fights ensue, culminating in a twenty-minute battle in which the hero and another schoolmate penetrate a restaurant where the villain is celebrating his new status. Thrashing their way through a crowded courtyard, then through a narrow tunnel of dining rooms, and finally into a two-story banquet hall, our heroes confront increasingly skilful fighters and eventually face off against their boyhood friend.

Ryoo keeps the action scenes fairly brisk and inventive. The most impressive early one shows the hero surrounded by a battalion of young thugs in a nighttime boulevard. The teens, in an obvious bow to The Warriors, come dressed in ingenious uniforms and display alarming skills with hockey sticks and baseball bats. As in Hong Kong films, judicious long shots keep us oriented to phases of the action.

Borrowing unashamedly from John Woo’s Better Tomorrow series and countless Japanese swordplay films, City of Violence shows flashes of pictorial wit. The cop and his pal realize they’re confronting a platoon of bodyguards at supper when doors slide open to reveal a tunnel-vision perspective of fighters, blobs of black broken rhythmically by women’s pastel outfits.

The film flaunts vivid color and icy focus in a way that much more expensive Hollywood genre movies, with their brackish palettes and soft edges, mostly avoid. (The realism alibi, again.) Even Ryoo’s use of CGI is playfully pretty, in a way that Casino Royale could be only in its credits sequence. Here the gang lord realizes his old pals are approaching.

I don’t want to oversell this film, but it does show that the classic Asian tradition has not expired. Running under ninety minutes without credits, City of Violence aims at nothing more than telling a familiar story with vigor—along the way making us gape and flinch. In a good way.

For arguments about Eisenstein and expressive movement, see my Cinema of Eisenstein, new ed. (Routledge, 2005). The case for Japanese and Hong Kong action films is made in Chapters 12-15 of Poetics of Cinema, and the pause/ burst/ pause pattern is analyzed in Chapter 8 of Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. There, among other things, I try to give Yuen Kwai his due.

Ashes to Ashes (Redux)

DB here:

Hong Kong films constantly shift their shapes. Both film prints and video versions circulate in a bewildering variety of forms. A movie shot in Cantonese (the vernacular of the locals) may be dubbed into Mandarin, the language of the Mainland and of Taiwan. But it may also be dubbed into English, French, or other Western languages; such was the fate of many kung-fu films of the 1970s, as well as later productions like The Killer (1989). I have seen Happy Together in Italian and In the Mood for Love in Spanish. When a movie is exported, it may also be recut to suit the local market. Typically Hong Kong producers have sold films under terms that allowed foreign distributors to do pretty much what they liked with both theatrical and video releases.

Alternatively, the filmmaker may cooperate and remake the film to fit foreign tastes. During the boom years of the 1980s and early 1990s, when many films were funded through presales to Taiwan, it was common to have both a Taiwanese version (usually longer) and a Hong Kong one. Jackie Chan’s Police Story (1985) included extra scenes of Jackie’s antics to satisfy Japanese audiences, and the directors of Infernal Affairs (2002) provided a less desolate ending to satisfy Chinese censors. In addition, filmmakers began circulating “international versions” that would play film festivals, and these might not accord with what was released locally. I’ve discussed one instance earlier on this blog: a version of Days of Being Wild that includes opening material not visible in the international print. My current supposition is that this is a local release print that may have circulated in Western Chinatowns too.

To complicate things further there was the institution of the midnight show. Instead of holding test screenings, Hong Kong producers would preview their films at a few theatres late on weekend nights. Audiences knew that they were acting as guinea pigs and weren’t shy about expressing their displeasure. While filmmakers cringed in the back, viewers might shout insults at the screen. The producers and the director would meet to settle on what changes should be made. Then they would hustle to prepare new versions for the official release in the next week or two.

On top of this, add the next layer of revision: the post-festival rethink. Western directors have redone their movies after discouraging festival response. Probably the most famous instance is the death and resurrection of Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny (2003).Now that Hong Kong and Taiwanese directors circulate on the fest scene, they too have tinkered with their work after premieres, notably Hou Hsiao-hsien, who has reworked films following less than enthusiastic Cannes screenings.

A director’s job is never done?

Like many Hong Kong movies, nearly every one of Wong Kar-wai’s films went through multiple versions. But unlike many directors he seems to enjoy tweaking and rethinking his work. In production he shoots scenes, watches them, reshoots them, recuts them, and reshoots again. Editing and mixing involve the same play with variants. He adds different shots, juggles the order, adds or subtracts music at will.

The process may seem to betray an uncertainty about what he wants his movie to be. For In the Mood for Love, he shot scenes of the central couple making love but didn’t use them, playing with the possibility that the affair is chaste. 2046 began as a high-concept project, based on the fifty-year expiration of the 1997 handover accords, and it went through many different incarnations. At one point it was to be a tale of the intertwining lives of different Hong Kong citizens whose addresses were 2046 on their streets. Even the actors may not know what’s up. At the Cannes premiere of 2046, Maggie Cheung was startled to learn that she was barely in the movie.

Of course most filmmakers rediscover their films at each stage of production, but for Wong the idea of a “locked” version is fairly indeterminate. Virtually everyone now acknowledges that a Wong festival premiere is a first approximation. Delivered in the nick of time (sometimes embarrassingly late), the film is likely to be reworked after initial screenings. Venice and Cannes, Tony Rayns points out, have served as counterparts to the local midnight shows.

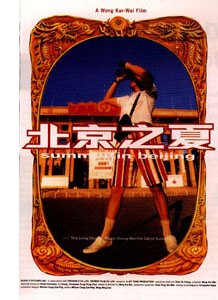

In Planet Hong Kong I suggested that Wong became a shrewd guardian of his brand. He has created high-end ancillary products, not only CD soundtracks but posters, T-shirts, glossy photo books, and limited-edition DVD sets. The Happy Together anniversary box (limited to 2046 units) includes a model of the spinning Iguazu Falls lamp and a pair of men’s briefs. The spinoffs are issued with fancy packaging, and they have usually sold briskly in upscale Asian shops, particularly in Japan. It’s characteristic that Wong’s aborted project Summer in Beijing could serve as a corporate travel logo. At once cult filmmaker and luxury franchise, Wong has every reason to refresh, and re-market, his content at intervals.

In Planet Hong Kong I suggested that Wong became a shrewd guardian of his brand. He has created high-end ancillary products, not only CD soundtracks but posters, T-shirts, glossy photo books, and limited-edition DVD sets. The Happy Together anniversary box (limited to 2046 units) includes a model of the spinning Iguazu Falls lamp and a pair of men’s briefs. The spinoffs are issued with fancy packaging, and they have usually sold briskly in upscale Asian shops, particularly in Japan. It’s characteristic that Wong’s aborted project Summer in Beijing could serve as a corporate travel logo. At once cult filmmaker and luxury franchise, Wong has every reason to refresh, and re-market, his content at intervals.

Yet I don’t maintain that he’s insincere. His drive to redo his films seems to go beyond indecision or commercial calculation. Wong seems to have taken to heart his central theme of the transient moment, the fact that love can be extinguished at any instant. So why not change your films to match your mood today? Further, like Warhol, he seems to enjoy prodigality for its own sake. He enjoys conjuring up one variation after another, multiplying just barely different avatars, and draping in mist the notion of any original text. His films’ basic constructive principle—the constant repetitions that create parallels and slight differences, loops of vaguely familiar images and sounds and situations—gets enacted in his very mode of production.

So he rebuilds even after release. The DVD release lets him tack on unused materials, extra scenes and different endings. That’s enough for most directors, but Wong has long harbored the dream of compiling vast swatches of unused footage in a sort of variorum DVD set of all his films. But why should he have all the fun? He once announced plans to put his footage for Happy Together on the Internet and let anyone make a personal version of it. That didn’t happen, but he did allow his assistants to make Buenos Aires Zero Degree (1999): not only an essayistic making-of but also a handsome reliquary of discarded material, including a gorgeous sequence of two taxis arcing away from each other.

Evil East, Malicious West, and their posse

Now we have Ashes of Time Redux, premiered at Cannes and showing in the US. The most apparent analogies, the oft-revised Blade Runner and the other redux, Apocalypse Now, don’t do justice to Wong’s fussbudget impulses.

For the original Ashes Wong assembled a high-wattage cast that included two of the Heavenly Kings of Cantopop and three glamorous female stars. He spreads out their duties by means of an ensemble plot. At the center stands Ouyang Feng (Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing), a swordsman who has set up a way station on the edge of the desert. He acts as a broker for people who want to hire killers. Another swordsman, Huang Yaoshi (Tony Leung Kar-fai) visits him every year. Ouyang nurses unrequited love for his brother’s wife (usually known as the Woman, played by Maggie Cheung Man-yuk), who lives far away. Huang is also subject to the Woman’s charms, but he is more deeply in love with Peach Blossom (Carina Lau Kar-ling), a woman he saw bathing her horse in a river. Peach Blossom is the wife of yet another wandering swordsman, who is gradually growing blind (Tony Leung Chiu-wai). He too fetches up at Ouyang’s outpost. Huang also runs afoul of the Murongs, a brother and sister who may be the same person (Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia). Meanwhile, a young girl (Charlie Yeung Choi-nei), fortified only with a mule and a basket of eggs, waits at Ouyang’s cabin to hire someone to avenge her brother’s death. Finally, there is Hong Qi (Jacky Cheung Hok-lau), a down-at-heel young killer for hire, who is followed across the desert by his wife.

The interlocking love triangles around a narcissistic man recall Wong’s breakthrough film, Days of Being Wild (1990), although here the parallels and connections are fleshed out through kinship too. The basic relations are at first hard to parse, though a Western viewer who didn’t recognize these stars will have more trouble than a Chinese one. Wong complicates the exposition by fragmenting his scenes and inserting flashbacks, though most of the latter are easy to follow.

He also helps the audience by following a common Hong Kong storytelling principle: reel-by-reel plotting. This breaks the movie into fairly discrete chunks of ten minutes (about a reel) or twenty minutes (about two reels). The first reel sets up the central relation of Ouyang Feng and Huang Yaoshi. Then two reels are devoted to the Murongs and their efforts to trap Huang. The next two reels are spent on the Blind Swordsman, followed by two reels devoted to Hong Qi and the Egg Girl. The last two reels unearth the long-simmering relationship among Ouyang, the Woman, and the despairing Huang. So the plot is actually a bit tidier than it seems at first, although each of these chunks is marbeled with references to other story lines. In Redux, Wong has also divided the plot into seasons, a strategy that accentuates the multipart structure.

Now about all those versions. Preliminary confession: These comments are based on one 35mm screening, and my analytical points are based on a DVD screener.

Keeping it unreal

Before Redux, there were at least two versions of Ashes of Time. One premiered at the Venice festival of 1994, the other became the international standard version. The differences are striking.

The international version has several hyperactive swordfights quite early. In a prologue before the title credit, Ouyang Feng and Huang Yaoshi fight a duel. After that, each is given a combat sequence in which he takes on hordes of assailants. These sequences are rapidly cut, with exaggerated angles, accelerated or slowed motion, and pulsing freeze frames. At the end of the international version comes a brief, parallel epilogue showing the surviving warriors (Ouyang, Huang, Hong Qi, and Murong) in the midst of combat. This epilogue includes a tableau of Yin, the female Murong, writhing ecstatically on a bed of red blossoms.

It’s widely believed among Hong Kong film people that this international version was initially created for the regional market and overseas Chinatowns. Wong added swordplay sequences at the beginning and end in order to satisfy his Taiwanese producers, who wanted more action in this otherwise talky and moody movie. How this version, running about ninety-five minutes without credits, became the standard one I don’t know, but evidently Wong did not control the international rights on the film. In any case, we have the evidence of Derek Elley’s Variety review that these passages were not in the Venice copy.

I’ve seen Ashes in 35mm in several countries, and it’s always been the international version. That is the version available on Hong Kong laserdisc and video, as well as on Japanese DVD (as near as I can tell from my imperfect disc). But the French DVD, released by TF1, is quite different. It runs 87:30 without credits (and assuming 24 fps). This version lacks several scenes, including the opening brawls, and ends with a close-up of the pale face of the Woman looking out to sea. It may be that this French version, billed on the packaging as the “original” one, is close to the Venice print.

Wong reports that he rescued original material, both positive and negative, from various sources. Since some of it was in poor condition, digital versions were made. In the final result, a few shots have been replaced with alternate takes. Yet the film is not simply restored but “reimagined,” as the title Redux indicates.

By and large, the sequence of story events, the shot-by-shot progression, and the monologues and dialogues are the same in both the international version and this new one. What, then, has Wong changed? He has kept nearly all of the brief prologue showing a rapid-fire combat between Ouyang and Huang. He has eliminated the approximately three minutes of the two fights that establish the solo prowess of the fighters. He has also cut the epilogue’s burst of action, retaining only a shot of Ouyang slashing in slow-motion and swiveling in a freeze frame that gradually fades out. In other fight scenes, he has trimmed some elaborate action and at least one gory bit, showing Murong impaling a cat.

Which is to say that he has deleted several conventional displays of the wuxia pian, or “heroic chivalry” film, of the 1990s. In Planet Hong Kong, I argued that Wong’s films often play off the mainstream conventions of his moment. He embraces pop music, pop stars, and pop genres: the triad movie (As Tears Go By, 1988), the melodrama (Days of Being Wild, Happy Together), and the romantic comedy/ cop movie (Chungking Express). But the films rework those conventions too. Wong subtracts a bit of glossiness by emphasizing the grubbiness of location shooting and by mussing up his stars, but then he re-beautifies things through his lustrous images and his unashamed interest in romantic longing. His men alternate between impulsive action and moody withdrawal, and his women mostly lounge about waiting for their men to make a move. (You could do a whole essay on the figure of the Waiting Woman in his work.) The sheer conviction of his style and sentiment can redeem quite hoary clichés, such as the woman’s inevitable complaint that her man never told her he loved her (a crucial turning point in Ashes of Time).

By the early 1990s, the wuxia pian had become a fantasy extravaganza, packed with flying swordsmen, magic potions, special effects, dynamic visuals, pounding music, and play with gender identity. The second and third installments of Tsui Hark’s Swordsman trilogy, a phantasmagoric treatment of the genre, present Brigitte Lin as the bi-gendered Invincible Asia, a vessel of both martial and erotic fantasies.

In part Ashes cites these current formulas in order to rework them. Conventional props like magic wine become tied to themes of memory and regret for missed chances. Discussions of combat strategy are replaced by monologues musing on lost loves. The male/ female masquerade of The East Is Red becomes, in Ashes, a hallucinatory shift of identity (are the Murongs two people or one person?) and forms one point of a thematic continuum centering on men’s desire to possess other men’s women.

Visually as well, Wong borrows and reworks fantasy wuxia conventions. One of the women warriors in The East Is Red (1993) unleashes her volcanic sword skills while standing on the surface of the sea.

Something quite similar happens in Ashes. But once Wong has turned Murong’s ambidextrous gender into a question of identity, you could argue that the geysers of water she unleashes make a broad thematic point: the primal force of a character named both Yin and Yang.

So the original Ashes reworks motifs to be found in Tsui’s extravaganzas, and for all I know in others as well. But apart from the Murong waterworks, these moments of dialogue with the fantasy wuxia pian entries are muffled in Redux.

From the original action scenes Wong has trimmed the turbocharged leaps and swoops, the blasts of “palm power,” and the possibility that a slashing blade can make a hillside explode. Perhaps Wong wanted to leave behind the overwrought world of wuxia fantasy—popular in 1994 but likely to seem cartoonish to Western audiences now. I wonder, though, why he has retained the opening clash between Ouyang and Huang, since the rest of the film presents them as friends. The answer may lie in the original Louis Cha novel, The Eagle-Shooting Heroes, a multi-volume saga that inspired both Ashes and the 1993 Jeff Lau film (co-produced by Wong) called by the novel’s title.

Other changes serve to create greater nuance or lyricism. The synthesizer score has been replaced by a spacious orchestral one, enhanced by stereo. Other stretches of music have been dropped altogether. There is a little less of the Morricone flavor now; the music coaxes rather than hammers. We get more shots of the moon, some fresh landscape vistas, a few more pools of water. Sometimes blood splashes out at us, but at one point an out-of-focus spray of blood is replaced by an optical effect showing wafting dark red billows.

The most pervasive change has involved the color tonalities. The 35mm prints of Ashes I’ve seen have favored a vivid orange-brown palette, with strong blues (sky and water), red accents, and very little green. The video copies vary, but the most commonly available DVD version is notably more russet and lower contrast than the 35mm. Redux, though, is a total rethink. Interiors have lost most of their hard-edged chiaroscuro and become softer and paler. Exteriors, and some interiors, have been keyed toward a hard yellow. The vivid browns and oranges have gone a bit gray, and the blacks verge on green. In addition, some highlights have burned out.

Consider these three frames. The first is a scanned Fujichrome slide that was photographed from a 35mm print. The second frame is from the Hong Kong DVD release. The third is from the Redux screener DVD. None has been photographically adjusted for reproduction here.

All of these are some distance from their sources; for instance, the 35mm slide can’t really capture the range of tonalities of the original, especially in the dark areas. Still, I think the relationship is a fair reflection of the differences. In 35mm, Redux looks a lot more crisp, rich, and detailed than in this DVD frame-grab, but the lemon yellows and pale greens are fairly faithful to my memory of the print.

Wong has taken advantage of ways to improve the film. Seeing the international version in 35mm, I was struck by problems in color matching. Shots apparently taken on different days didn’t always cut smoothly together, and sometimes shot/ reverse-shot passages displayed varying color grades and levels of graininess. By adding fairly consistent tints and by softening certain sequences, Wong has given the film greater tonal consistency. Further, he has upped the artificiality of the film’s look, creating a neutral ground against which certain colors, such as the wan face and ruby lips of the Woman, stand out even more vividly. With its softening and tinting, the film now looks more like a recent release–portions of Soderbergh’s Traffic, say, or some of the tamer stretches of a Tony Scott movie.

Once Redux appears on DVD, admirers will be kept busy plotting some minute differences in shot order and alternate takes. They will marvel at the way that Wong has inserted a few more images (e.g., during the fantasy caressing of Ouyang) but has kept the overall sequence the same length. There will also be intriguing questions. Why the choice of yellow as a key tone? Why the occasional and blatantly video-derived image, such as the pan shots that enframe the central story, and perversely run the opposite direction of their counterparts in the other versions? And why the digitized banks and foliage—maybe just because they look wonderful?

In case you wonder, this frame is not inverted.

I’m still getting accustomed to the film’s new look, and I need to see a print again to verify these general impressions. Still, I like to think that by recasting his film so markedly, Wong has brought his masterpiece back under his control. In this sense, his changes remind me of Stravinsky’s reorchestration of Petrushka and other early ballets. Stravinsky rewrote the scores in order to win performance rights, but he also brought his latest thinking to the task. In the same way, Wong has made Ashes of Time new all over again—available to many more viewers now and hereafter. This daring, fourteen-year-old exercise in avant-pop moviemaking is miles ahead of nearly everything on view right now.

For more on Wong Kar-wai product lines, go here. Wong talks about the restoration of Ashes here and here and in a video interview at the New York Film Festival. For more on reel-by-reel plotting in Hong Kong film, and a broader discussion of Wong’s films, see my Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, 180-182, 271-281. For other critical discussions of Ashes of Time, see Stephen Teo, Wong Kar-wai (London: British Film Institute, 2005) and Peter Brunette, Wong Kar-wai (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005). Unless otherwise noted, the frame enlargements in this entry are taken from a 35mm print of the 1994 international version of Ashes.

Thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Sarah Simonds and Jacob Rust of Sundance 608, Madison, Wisconsin, where Ashes of Time Redux is scheduled to open on 30 January.

Top: WKW and the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, which awarded its Best Film honor to Ashes of Time, spring 1995. Below: DB presents WKW with the award.

Danes not dour, can do drollery

DB here:

With our new edition of Film History: An Introduction in the final phases of production, we’re pretty busy. But I still hope to post an entry on Ashes of Time Redux later this week. I’ve got some pretty pictures, at least.

In the meantime, if you know the films of Carl Dreyer, you must look at this mini-movie. It was created by Henrik Fuglsang, the Danish Film Institute archivist at work on a massive website devoted to Dreyer.

Have patience and let it load fully; the holiday cheer is worth it. Thanks to Casper Tybjerg for sending me the link.