Archive for the 'Little stabs at happiness' Category

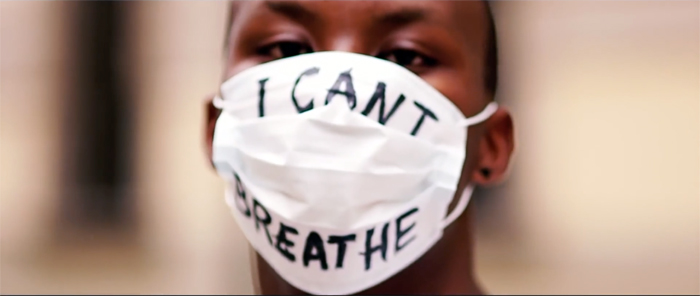

Little stabs at happiness 6: Breathe

Commander in Chief (2020).

Last summer, in hope of reviving spirits in these times, I ran a series of clips I admired for their ability to arouse and energize. They created a sort of disciplined exhilaration through adroit editing, camerawork, and music. They reliably gave me a lift, and maybe you too.

Now, in the Caligula phase of Trump’s presidency, it seems appropriate to pay my respects to a masterpiece of engaging agitprop. I’ve registered my reservations about the Lincoln Project in an earlier entry, but there’s no denying that these walking wounded of right-wing partisanship have recruited some very talented filmmakers. Their “Covita” assemblage was superb, and they have outdone themselves with this morning’s triumph.

Here it is:

Experience it–but then we should study it.

It’s an excellent example of what we call in Film Art associational form–a blending of images, sounds, and texts to imply ideas and provoke feelings, in the manner of lyric poetry. The text itself is a lyric poem, at once ode, elegy, and apostrophe. Demi Lovato’s choked, rising and falling vibrato is in itself powerfully expressive. Just as important, the audiovisual texture enriches the text. Sometimes it’s a matter of the image echoing the words, and sometimes the associations are purely visual. An element in one shot, such as a gesture or facial expression, will call up something similar, or a contrast.

The effects flash by quickly. Taken just as images, what do these shots have in common?

Nothing but a pulse: Labored breathing on a ventilator matches the flicker of an emergency vehicle’s turn signal, as if life is running out before our eyes..

The structure mimics the song’s layout. We move from problem to solution, from crisis to resistance, from emptiness to crowds, ending on a resolution that puts action in the hands of the viewer. Threading it all together is the way “I can’t breathe” gets redefined. The phrase shifts from being associated with George Floyd and other victims of police atrocities, to the COVID-19 pandemic, before adding a twist: Trump’s own bout with the virus, capped in a direct address to him. How does it feel to be able to breathe? By the end breathing becomes metaphorically linked to voting. How does that feel?

As I mentioned in that earlier entry, contemporary agitprop reminds us how much every filmmaker owes to traditions. The techniques used in Commander in Chief stretch far back into the history of cinema; the upraised fists of the finale could have come straight out of Soviet montage.

It might seem pedantic to talk this way about such a powerful piece of cinema. But the point is that the things we study are really out there, crafted by creative filmmakers and having an impact on viewers. The art we care about has concrete effects, and in studying it we can clarify just how those effects are achieved. Analyzing forms and styles can broaden our sense of what cinema can do, and it can strengthen our respect for the filmmakers who explore it.

A similar analysis could be undertaken with many of the best current polemical documentaries, like Unfit and Totally Under Control. These galvanize us not just through their subjects and “messages” but through their fresh use of conventions of form and style. (The sequences of Totally Under Control devoted to First Capon Jared Kushner will remain models of satiric montage.) As with the best of Adam Curtis’s work, these are important contributions not just to political discourse but to the history of film as an art form.

Those goosebumps, that quivering gut, those tears? They come from cinema, grand synthesis of the arts.

Another documentary working in this vein, Leo Hurwitz’s Strange Victory, is discussed here. It’s completely appropriate to our current crisis.

For other reflections on the Trump coup attempt, go here and here and here and here.

P.S. 9 December 2020: After winning an Advertising Age award for the Lincoln Project campaign videos, Rick Wilson explains the strategy and assesses their success in the first of four parts.

P.P.S. 24 December 2020: More backstory on the making of these videos from producer/director Ben Howe.

Totally Under Control (2020).

Little stabs at happiness 5: How to have fun with simple equipment

Tiger on Beat (1988).

DB here:

Simple equipment includes, but is not limited to, knives, pistols, shotguns, ropes tied to shotguns, surfboards, chainsaws, etc.

Herewith another attempt to brighten your days with a choice film sequence that never fails to bring a foolish grin to my face. Apologies as ever to Ken Jacobs for my swiping his title.

Tiger on Beat (aka, but less pungently, Tiger on the Beat, 1988) is prime Hong Kong showboating. This final scene assembles some of the greats—Chow Yun-Fat, Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, Chu Siu-Tung (too little to do)–and near-greats like Conan Lee Yuen-Ba, who gets points for heedlessly executing the stunts Chow and Chow’s doubles can’t. Lau Kar-Leung (aka Liu Chia-Liang), one of Hong Kong’s finest directors, imbues both the staging and the editing with the crisp, staccato rhythm that this tradition made its own, and that few American directors have ever figured out. (It’s a long clip, so it may take a little time to load. In addition, our Kaltura operation is having problems, so you may want to try different browsers.)

Come to think of it, this little-stabs entry contains some fairly big stabs of its own.

The whole film is worth a look. Opening scenes feature Chow in outrageous threads, the very opposite of a cop in plainclothes, and there’s a fine car chase in which many risk life and limb. But this sequence, lit high-key so that every splash of saturated color pops, is for me the highlight, a tour de force of action cinema. Probably not for the kids, but what do I know about kids?

Sequences like this were what drove me to teach Hong Kong film and write Planet Hong Kong. They also impelled Stefan Hammond and Mike Wilkins to write Sex and Zen and a Bullet in the Head (1996), the most deeply knowledgeable fanguide to this glorious cinema. Stefan followed it up with Hollywood East: Hong Kong Movies and the People Who Made Them (2000). Now Stefan and Mike have effected a merger of these and updated and expanded them. They’ve also recruited a band of other Guardians of the Shaolin Temple: Wade Major, Michael Bliss, Jeremy Hansen, Jude Poyer, David Chute, Dave Kehr, Andy Klein, Adam Knee, Jim Morton, and Karen Tarapata.

The result is another indispensable volume, More Sex, Better Zen, Faster Bullets: The Encyclopedia of Hong Kong Film. The recommendations are sound, the plot synopses are nearly as much fun as the movies, and the authors have wisely retained chapter titles like “So. You think your kung fu’s. . . pretty good. But still. You’re going to die today. Ah ha ha ha. Ah ha ha ha ha ha.”

They weigh in on today’s sequence: “This gory Armageddon-duet consistently scores on Top Ten End-Battle Lists among HK film aficionados.” Makes me even more confident to recommend it to you. They add that the credits music is “a hard-rocking theme song by HK power diva Maria Cordero.” So I let it run.

I analyze this and other action sequences in this blog entry. An appreciation of Lau Kar-Leung is here.

For more little stabs, check out earlier entries in this series.

Chow Yun-Fat gets his daily dose of egg yolks (Tiger on Beat).

Little stabs at happiness 4: Hitmen, with a side of sukiyaki

A Hero Never Dies (1998).

DB here:

Again, with apologies to Ken Jacobs, I offer another clip that pleases me in this long, hot summer. For earlier installments, go here, here, and here.

Johnnie To Kei-fung has been one of the leading Hong Kong directors since the 1990s. The first edition of my Planet Hong Kong (2000) wasn’t able to incorporate many mentions of his work, but that failing was remedied in my second edition, where he got several pages. Kristin and I first met him in fall of 2001, when Yuin Shan Ding arranged for us to visit the set of Running Out of Time 2. That was a memorable night, with the bike race shot in an elaborate false street wreathed in noirish city vapor.

We spent down time with the stars Ekin Cheng Yee-kin and Lau Ching-wan. It was the beginning of a long friendship with Shan, Mr. and Mrs. To, and the Milkway team.

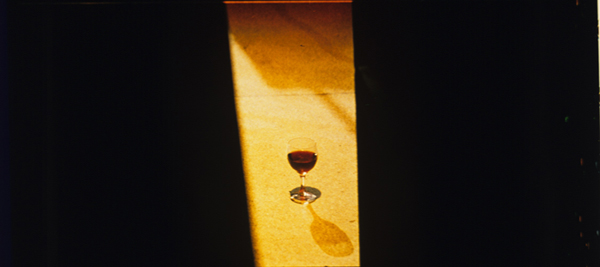

Well before this, though, I had been teaching Mr. To’s films in my courses, and I much enjoyed showing–on 35mm, no less–A Hero Never Dies (1998). This flamboyant film, about two rival hitmen who unite against the gang bosses who have betrayed them, is a sort of post-John-Woo meditation on the costs of loyalty.

One sequence that usually got the students going was the men’s first up-close confrontation in a bar. Having struck out at each other long-distance, they rendezvous for a face-off–not over guns but over glasses of wine. The clip lacks subtitles, so I should explain that each man instructs the bartender to pour for the other one. Then, after Lau deploys his portion tactically, he refers to Lai’s wrecking his apartment: “This is for destroying my home.” There follows a tabletop action scene.

Shot and cut with great precision, timed to an infectious tune, it’s a model of mock-heroic filmmaking. Its brashness suits its swaggering protagonists, but it has a playground absurdity that evokes Leone. (Think of the hat-blasting gun duel in For a Few Dollars More.) The comedy is enhanced by Lau’s reaction shots and, as Kristin likes to point out, the heaviest coin in Hong Kong. One student told me: “When you’ve got a sequence like this, you’ve got a great national cinema.”

The result yields a pure kinetic pleasure, due partly to the coiling camera movements and the echoing rhythm of the cuts and gestures (ducking out of frame/rising into frame, finger flips/snorting smoke). Mr. To kindly took me through the sequence in an interview, and I learned that it was all shot in one night, after the bar had closed. It wasn’t storyboarded, but by this point Mr. To had all his shots and cuts in his head, and he and the actors developed the sequence as they filmed it.

It takes real pictorial intelligence, I think, to glide between concreteness and abstraction, onscreen and offscreen space, and each man’s optical viewpoint so suavely and zestfully. The camera plays peekaboo with the action.

As for the performances, Mr. To explained that Lau Ching-wan is such an extroverted actor that Leon Lai-ming could counter that bravado best by impassivity, returning his look at key moments. It’s an echo of what Howard Hawks told Montgomery Clift in facing off against John Wayne in Red River. Eventually it all settles into a calm, integrating long shot that declares a truce. What a pleasure to see a scene that actually buttons itself up visually.

And the song? Mr. To told me that the pop version of “Sukiyaki” (on the ambient soundtrack of my own teen years) was often played in theatres as pre-show music. “It always reminds me of movies.”

Thanks to Shan, Mr. and Mrs. To, To Kei-chi, and many other members of the Milkyway team. And to Li Cheuk-to, Athena Tsui, Jacob Wong, Sam Ho, and all the other HKIFF allies over the years. And continued hope for a strong Hong Kong!

We have many blog entries on Johnnie To and Milkyway.

Upper row, left to right: Lau Ching-wan, Yau Na-hoi, Johnnie To Kei-fung; bottom row, Ekin Cheng Yee-kin, DB, KT. Hong Kong, November 2001. Photo: Yuin shan Ding.

Little stabs at happiness 3: You know, for kids

Iron Monkey (1993).

DB here:

Another entry (apologies to Ken Jacobs) of little things that cheer up lockdown. Previous entries are here and here. This one, unlike a couple to come, is suitable for all ages.

Why do I get a thrill from watching an apparently frail little boy beat the bejeezus out of unkempt bullies? More to the point, why weren’t there movies like Iron Monkey (1993) when I was a tad?

It’s a wing of the Tsui Hark Wong Fei-hung reboot saga that began with Once Upon a Time in China (1991), putting Jet Li on the world map. This installment is directed by Yuen Wo Ping, master choreographer of Crouching Tiger and The Matrix and no mean director himself. It’s a prequel, showing us the young Fei-hung learning his craft from his apothecary father and the mysterious robinhoodish Iron Monkey.

Before the main course, here’s a snack.

This one minute of graceful movement is one minute more than you find in most of our movies today. Do something short, smart, and crisp, and the camera loves it.

To see Young Wong finding his groove, here’s the scene in which he practices some fancy evasion and defense against heavily armed but fatally dumb thugs.

The subtitles provide a whole other level of diversion.

The whole film, featuring Donnie Yen and other Hong Kong stalwarts, is good dirty fun. Versions are available on streaming, but you should avoid the sanitized Miramax release. There’s also a 1977 kung-fu film bearing this English-language title, but its plot is quite different.

Note: The boy Wong is played by a girl martial artist, Angie Tsang Sze-man, who went on to become a wushu champion.

For an update on the situation in Hong Kong, here is a story in the Washington Post.

I write about the art and craft of Hong Kong martial arts movies in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. It explains, among other things, why the subtitles are so weird (p. 78).

P.S. 15 June 2020: Thanks to Radomir Kokes (Douglas) for correcting my misattribution of The Transporter to Yuen Wo Ping. It was of course directed by the great Corey Yuen Kwai.