Archive for the 'National cinemas: Turkey' Category

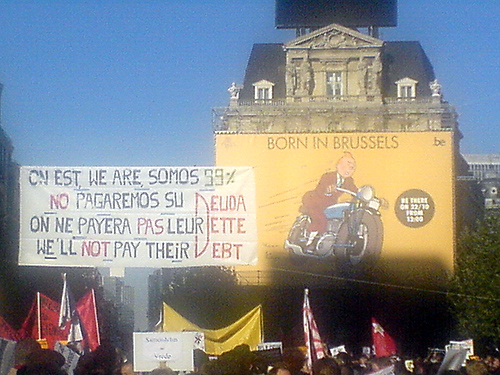

Catching up 99%

Clash by Night.

DB here:

Amplifications, corrections, and updates have been piling up over the last couple of months, and we began to realize that simply appending postscripts to older entries probably didn’t register with many readers. Judging by our stats, revisiting older entries isn’t a priority for most of the souls whom fate throws our way. So here’s some new information about older posts.

*I wrote about Jafar Panahi‘s This Is Not a Film at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Today Variety reported that an appeals court has upheld Panahi’s sentence of six years in prison and a twenty-year ban on travel and filmmaking. His colleague Mohammad Rasoulof’s jail sentence was reduced to a year. Panahi’s attorney says that she will appeal the decision to Iran’s Supreme Court. Be sure to read the Variety story for some background on the despicable treatment of other filmmakers, notably a performer who, merely for acting in a movie, was sentenced to a year in jail and ninety lashes.

*My trip to the Hong Kong festival last spring was to have included a visit to Japan. But the earthquake and the tsunami decided otherwise. Here are two remarkable items about the country’s catastrophe and the people’s resilience. First, a camera captures what it’s like to be in a car that’s swept away. Then we have photographs of the remarkable recovery that some areas have made–a real tribute to Japanese resilience. (For the links, thanks to Darlene Bordwell and Shu Kei.)

*My trip to the Hong Kong festival last spring was to have included a visit to Japan. But the earthquake and the tsunami decided otherwise. Here are two remarkable items about the country’s catastrophe and the people’s resilience. First, a camera captures what it’s like to be in a car that’s swept away. Then we have photographs of the remarkable recovery that some areas have made–a real tribute to Japanese resilience. (For the links, thanks to Darlene Bordwell and Shu Kei.)

*At Fandor, in response to Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, Ali Arikan wrote a penetrating and personal essay that I wish I’d had available when I wrote my review at VIFF.

*Tim Smith‘s guest entry for us, “Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD,” was a huge hit and went madly viral. At his site, Continuity Boy, he has posted a new, no less stimulating entry on eye-scanning. It shows that we can track motion even when the moving object isn’t visible!

*During my trip to Brussels in early September for the conference of the Screenplay Research Network, I stole time to visit the superb Galerie Champaka for the opening of its show dedicated to Joost Swarte (above). Longtime readers of this blog know our admiration for this brilliant artist, so you won’t be surprised to learn that I had to get his autograph. The show, consisting of work both old and new, was also quite fine; it’s worth your time to explore the pictures, such as the one revealing how Disney was inspired to create Mickey (above). Thanks to Kelley Conway for taking the shot, and to Yves for taking this one. And special thanks to Nick Nguyen (co-translator of two fine books, here and here) for alerting me to the show.

*An update for all researchers: Now that we have online versions of the Variety Archives and the Box Office Vault, we’re happy as clams. (But what makes clams happy? They don’t show it in their expressions, and their destiny shouldn’t make them smile.) Anyway, to add to our leering delight, we now have the splendidly altruistic Media History Digital Library, which makes a host of American journals, magazines, yearbooks, and other sources available in page-by-page format, ads and all. You’ll find International Photographer (too often overshadowed by American Cinematographer), The Film Daily, Photoplay, and many more. Get going on that project!

*This just in, for silent-cinema mavens: The Davide Turconi Project is now online, thanks to a decade of work by the Cineteca di Friuli. Turconi was a much-loved Italian film historian who, among other accomplishments, collected clips of frames from little-known or lost films. The archive of 23,491 clips, usually consisting of two frames, is free and searchable. On the left we see a snip from Louis Feuillade’s Pâques florentines (Gaumont, 1910). Paolo Cherchi Usai and Joshua Yumibe coordinated this project, with support from Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto, George Eastman House, and the Selznick School of Film Preservation. (Thanks to Lea Jacobs for supplying the link.) For more on Josh’s research, see our entry here.

*This just in, for silent-cinema mavens: The Davide Turconi Project is now online, thanks to a decade of work by the Cineteca di Friuli. Turconi was a much-loved Italian film historian who, among other accomplishments, collected clips of frames from little-known or lost films. The archive of 23,491 clips, usually consisting of two frames, is free and searchable. On the left we see a snip from Louis Feuillade’s Pâques florentines (Gaumont, 1910). Paolo Cherchi Usai and Joshua Yumibe coordinated this project, with support from Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto, George Eastman House, and the Selznick School of Film Preservation. (Thanks to Lea Jacobs for supplying the link.) For more on Josh’s research, see our entry here.

And while we’re on silent cinema, Albert Capellani is in the news again. Kristin wrote about this newly discovered early master after Il Cinema Ritrovato in July. A recent Variety story discusses some recent restorations and gives credit to the Cineteca di Bologna and Mariann Lewinsky.

*My entry on continuous showings in the 1930s and 1940s attracted an email from Andrea Comiskey, who points out that when Barbara Stanwyck and Paul Douglas go to the movies in Clash by Night (above), she prods him to leave by pointing out, “This is where we came in.” Thanks to Andrea for this, since it counterbalances my example from Daisy Kenyon, which shows Daisy about to call the theatre for showtimes. And since posting that entry, I rewatched Manhandled (1949). There insurance investigator Sterling Hayden hurries Dorothy Lamour through their meal so that they’ll catch the show. He apparently knows when the movie starts. So again we have evidence that people could have seen a film straight through if they wanted to. It’s just that many, like channel-surfers today, didn’t care.

*Finally, way back in July, expressing my usual skepticism about Zeitgeist explanations, I wrote:

I’m still working on the talks [for the Summer Movie College], but what’s emerging is one unorthodox premise. As an experiment in counterfactual history, let’s pretend that World War II hadn’t happened. Would the storytelling choices (as opposed to the subjects, themes, and iconography) be that much different? In other words, if Pearl Harbor hadn’t been attacked, would we not have Double Indemnity (1944) or The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945)? Only after playing with this outrageous possibility do I find that, as often happens, Sarris got there first: “The most interesting films of the forties were completely unrelated to the War and the Peace that followed.” Sheer overstatement, but back-pedal a little, and I think you find something intriguing.

David Cairns, whose excellent and gorgeously designed Shadowplay site is currently rehabbing Fred Zinnemann, responded by email:

Firstly, I find the start of WWII being equated with Pearl Harbor a little American-centric. Much of the world was already at war when that happened. Secondly, it could certainly be suggested that the two films you cite WOULD have been different without a world war. Billy Wilder and Robert Siodmak were comfortably making films in France before Hitler’s invasion drove them to a new adopted homeland. Those movies might well have happened without WWII, but they would probably have had different directors.

Thanks for this. Your points are well-taken. Not only was I America-centric, but I neglected to point out that before Pearl Harbor America was more or less directly involved in the war. Even though America wasn’t yet in the war in late 1941, a lot of the economy was on a war footing and the industry was already benefiting from the rise in affluence among audiences.

Your point about the particular directors is reasonable too. I think I chose bad examples. All I wanted to indicate was that the Hollywood system continued to function as usual, particularly with respect to narrative strategies. For instance, Chandler wrote the screenplay for DOUBLE INDEMNITY (and apparently was responsible for the flashback construction), and as you say, had another director handled it, at the level of narration it might well have been the same. UNCLE HARRY is a harder case for me, I admit! Maybe I should have chosen THE BIG SLEEP and MURDER, MY SWEET!

David replied with his usual generosity:

That’s OK! BIG SLEEP and MURDER MY SWEET definitely work! Plus any number of non-flag-waving musicals, westerns, swashbucklers (though there’s a little propaganda message in THE SEA WOLF at the end) and certainly comedies and horror. . . .

And then there’s KANE and AMBERSONS.

Better late than never–something you can say about all these updates.

Reasons for cinephile optimism

Hollywood may have largely let us down this year, but after the first few days at the Vancouver International Film Festival, we’ve seen several excellent films and a lot of originality. Here are two of the highlights so far.

Kristin here:

Every year, when festival posts its list of films, I look through it for titles I’d heard about from other festivals or seen enthusiastically reviewed or had recommended to me. One title I was delighted to see on this year’s program was Lech Majewski’s The Mill & the Cross. It’s not nearly as famous as some of the other films showing here, like The Skin I Live In or Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, but I keenly anticipated seeing it.

I learned about The Mill & the Cross through an article in American Cinematographer (posted on the film’s rich website). Majewski collaborated with art historian Michael Francis Gibson to explore Pieter Bruegel’s 1564 masterpiece, “The Way to Calvary.” In the painting, the figure of Christ carrying his cross to calvary is set in the midst of a vast landscape full of fields, cliffs, a distant town, trees, and hundreds of people, all surmounted by a windmill atop one of the rocky formations and silhouetted against a windy, cloudy sky. Majewski sought, as he said, “to enter Bruegel’s world”—to enter into the painting itself and bring it to life.

His goal reminded me of Godard’s 1982 film, Passion, where one of the main characters films actors in a studio. He appears to be trying to replicate classic paintings, with models posed in costumes and miniatures representing a cityscape. I’ve never been able to picture what the result might have looked like. I’m not sure I would have enjoyed watching it, which may be part of Godard’s point. But Majewski had the tremendous advantage of modern computer technology to create an almost seamless blend between digital elements derived from the original painting and those derived from live-action filmmaking on location and in front of blue screens. For those who complain about “effects-heavy” blockbusters, The Mill & and Cross is a powerful counter-example, a film utterly dependent on CGI yet meditative and even profound. It certainly succeeds in Majewski’s goal, creating an uncanny sense of being inside the painting (see above.)

For the film seeks to explore the qualities that Bruegel himself did, to push the crucifixion to a minor place in the composition of the whole and to explore the sacred in the everyday. The film’s story is dense. On one level, we watch Bruegel sketching his models as he explains the concept of the painting to his patron. But we also see him departing home in the morning, and we follow the everyday doings of his family. We see several other minor characters who will figure in the painting waking up and beginning to work, including the miller in his mill atop the cliff. The filmmaking team found a surviving mill of the period, and for an astonishing scene early on, the ancient works in the vast interior were set in motion for the first time in centuries.

We see details of the characters’ lives, such as a man hitching up a horse to a wagon, an innocent-appearing detail until we realize much later in the film that this cart will deliver the wood for making the crosses and will carry the two thieves condemned to die alongside Jesus to Golgotha. Finally, we are invited to contemplate the contradiction, so familiar from thousands of paintings, that an event from antiquity is seen taking place in a contemporary landscape. The result is a comment on the Spanish occupation of Flanders as well as on the Biblical story.

In an all-too-brief scene, Bruegel explains the composition of the painting to his patron, showing how the small group around Jesus forms the center, with the lines between the other main elements around the periphery intersect with it. The implicit comparison is to a charming moment in the film when the painter admires an intricate spiderweb. Apart from all the thematic material, we do learn something about Bruegel’s painting–a point that is emphasized at the end of the film, which tracks back from the actual painting in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, as if inviting us to go and contemplate it in the light of what we have just seen.

Part of what makes The Mill & the Cross so exciting is that it achieves that rarest of things, making us feel that we are seeing something very worthwhile that has never been done before.

The film has a very limited release in the U.S. Anyone who has a chance to see it on the big screen should snatch it. The images, shot on the Red One camera and projected (here, at least) on 35mm, are spectacular.

Once upon a time, and time again

DB here:

Cesare Zavattini, central screenwriter of Italian Neorealism, liked to tell this story. A Hollywood producer once told him:

“This is how we would imagine a scene with an aeroplane. The plane passes by. . . a machine gun fires . . . the plane crashes. And this is how you would imagine it. The plane passes by. . . The plane passes by again… The plane passes by once more…”

He was right. But we have still not gone far enough. It is not enough to make the aeroplane pass by three times; we must make it pass by twenty times.

And, Zavattini seems to suggest, the machine gun should never fire.

Neorealism was one of the most important influences on what we’ve come to call the postwar European “art cinema,” and particularly on filmmakers’ treatment of time. I thought of the Zavattini passage while watching the opening scenes of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, a film which proves that you can always ring fresh changes on a well-established tradition.

Actually, “opening scenes” isn’t quite right. The very first thing we see, a sort of prologue, presents in two shots the lead-up to a crime. Then come a couple of minutes of credits. Then we get nearly fifty minutes of nighttime shots of police cars driving through the countryside, headlights appearing tiny in the landscape. Again and again the cars halt as the police ask their murder suspect if this is the place where he and his brother buried the body of the man they killed. The suspect says he was drunk and can’t remember exactly. The investigators pick over the area looking for clues before driving on.

But the sequences aren’t quite as spare as I’ve indicated. Scenes inside the car and poking around the areas that might harbor the body pick out two main characters: a brooding doctor and a careful prosecutor overseeing the operation. The secondary cops and assistants are sketched in too. So we have a sort of balancing act between daringly distant “empty” shots and more standard expository scenes. The conversations in the car and in the landscape balance moments that dwell on atmospheric detail. So the relaxed pacing spares time for what will surely be one of the film’s most famous shots, a view of an apple shaken from a tree and bouncing downhill into a stream, where it continues to roll and bob in the dark. It presages the importance of melons, and in the final shots, a yellow soccer ball.

We frequently find that an art film flaunts some arresting narrational devices at the start before taming it as things move along. (Think of 8 ½’s bold opening, initiating us into Guido’s fantasy world, in effect teaching us how to watch the film.) Similarly, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia gets more linear and psychological as it goes along. It shifts from the more unfamiliar uncertainties of the futile stops and explorations to the better-defined questions we expect in a mystery. Is the suspect really guilty, or did his brother commit the murder? What triggered the killing? What effect has the crime had on the dead man’s wife and son?

The gradual shift seems to me to match a certain rigor in Ceylan’s stylistic handling. (Warning: Stylistic spoilers ahead.) In the nighttime search, long shots and extreme long shots dominate—if not by their number, at least by their prominence and vividness.

But having given us plenty of lengthy establishing shots in the first long section, Ceylan denies them in the next two portions.Later in the evening, the search party takes refuge in the house of a village leader and shares a meal with him. Here the action is broken up into close shots, with no long shots (I think) establishing where the characters are sitting. Everything, including the arrival of their host’s beautiful daughter, is given in tight shots of each character.

When the searchers return to town the next morning, they’re greeted by an angry mob. Again, the action isn’t shown fully. Now very long telephoto shots let us glimpse the police and the wife and son of the murdered man, with the crowd visible only as surging, out-of-focus heads and shoulders blocking the foreground.

The last forty minutes or so are centered on the doctor. Attached to him, we watch some interactions that trace out his responses to what he’s witnessed. These are handled in a traditional way, with shot/ reverse-shots, some of them head-on optical point of view, and lingering shots of the doctor brooding.

To the end, Ceylan doesn’t become completely predictable. There’s a nifty bit of elliptical editing during a conversation with the prosecutor. The offscreen sounds of an autopsy, layered by the sound of children’s play, recall passages of shrewdly timed offscreen dialogue that we heard during the long night’s search. And the final few shots play with optical point-of-view in a misleading fashion that has become something of a tradition in the art cinema.

So if the plotting gradually settles down into something less disconcerting, so does the visual style. But that shouldn’t take away from the delicacy and deliberation of a film that gains real gravity through hints and elisions. Above all, certain faces, particularly the despairing one of the prisoner who has a painful secret (surmounting this section), exercise a powerful hold on us. The conclusion of Once Upon a Time in Anatolia pulses with genuine emotion, coolly contained in a mode of cinematic expression that after sixty years or so continues to harbor great power.

The Zavattini passage on flying planes is available here.

PS 9 October: Thanks to Miklós Kiss for correcting an embarrassing spelling error.

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia.

PS October 8: Jim Emerson has also written on The Mill & the Cross, linking to an interview with Majewski on BOMblog.

Wrapping up the ROW

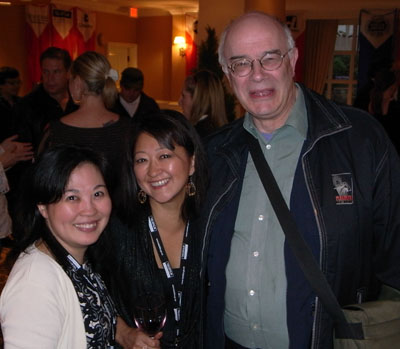

Paparazzi swarm over the nominees for the Dragons and Tigers Award at the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Kristin here:

Some final films from VIFF

So far Central American countries have produced fewer films than their neighbors to the north and south. So I couldn’t pass up The Wind and the Water, the first fiction feature made in Panama. Made by a collective of fifteen young indigenous people from the Kuna Yala archipelego under the leadership of MIT graduate and first-time director Vero Bollow, it’s a tale of threats to the paradisiacal island by developers who want to build a giant hotel there. It also reflects temptations for young people to desert their traditional lives on the islands for the attractions of nearby Panama City.

The contrast between the islands emerges through a simple tale. Machi, a young man from the islands, goes to the city for schooling and finds it grim and threatening. Rosy, a transplanted native who grew up there, aspires to be a model.

She returns to the islands for her grandfather’s funeral. Confronted with crude latrines and fish-head stews, she is initially miserable but gradually falls under the spell of the area’s beauty. Meanwhile her father works for the group planning to move the islands’ population to a new suburb and build their resort.

The plot is based loosely on that population’s vigorous efforts—successful so far—to fend off efforts of outsiders to gain control of the islands. I was reminded while watching it of the many classic documentaries of the 1930s and 1940s, like Song of Ceylon, shot by Americans and Europeans in exotic locales. For decades film scholars deplored the fact that the people who formed the subjects of such films were being portrayed by outsiders. The Wind and the Water, though a fiction film, has a strongly documentary thread running through it, but this time it is the local population making a film about their own situation.

Bollow (right), who initially left MIT to live in Panama and bring digital technology to indigenous people, wrote the script along with the fifteen team members. She attended Vancouver and answered questions, but members of the team will be traveling with the film to other festivals.

Bollow (right), who initially left MIT to live in Panama and bring digital technology to indigenous people, wrote the script along with the fifteen team members. She attended Vancouver and answered questions, but members of the team will be traveling with the film to other festivals.

In some ways, Ozcan Alper’s debut feature, Autumn, is a classic art-house film. Yusuf, a student radical, is released after ten years in prison because he has a fatal lung disease. He returns to his home. He returns to his rural home in the eastern Turkish mountains and settles in with his widowed mother, keeping his illness secret. He tutors a local boy in math and perhaps falls in love with a melancholy prostitute struggling to support her child.

Many of the scenes consist of the hero lying or sitting in the yard, contemplating the surrounding mountains as autumn slowly changes them. David found the lack of dramatic action and the slow pace of the scenes to be overly familiar conventions of art cinema. No doubt the hero’s goals are de-dramatized, as when he promises a bicycle to the student should he succeed in mother or when very late in the film he decides to help the prostitute. There is one central motif that becomes overly emphatic. When Yusuf first notices the prostitute, she is buying a Russian novel; they simultaneously sit alone watching the same broadcast of Uncle Vanya; eventually she tells Yusuf that he’s like a character out of Russian literature. The film’s tone successfully suggests this comparison without our needing to have it made explicit.

To me, the success of the film arises from the director’s integration of the landscape into the story. The prominence of the rugged landscape and the care with which the story is linked to the fall of leaves and the creeping of snow down the mountainsides lifts this above standard art-house fare. In this case, the fading of the year, beautifully brought into a central role by the cinematography, becomes linked more subtly to the hero’s plight.

Kill Daddy Goodnight, an Austrian film by veteran director Michael Glawogger, starts with a promising premise. The protagonist Ratz hates his father, a cold and critical government minister, and creates a videogame, “Kill Daddy Goodnight,” to wreak a fantasy revenge. Summoned by Mimi, a friend with whom he may or may not be in love, he abruptly flies to New York. She wants him to renovate the basement hideaway of her grandfather, a fugitive Nazi war criminal. Initially revolted, over the course of his work he comes to like the old man. Ratz also manages to find a sleazy internet entrepreneur willing to offer “Kill Daddy Goodnight” on his website, where it becomes an immediate success. Interspersed with this plot are scenes of an unidentified man (below) recording testimony against and visiting his childhood friend, who had worked for the Nazis during the war and killed his father.

So far, so good. But the film’s already complex plot is overburdened by strong hints of Ratz’s incestuous desire for his sister, a thread that comes to little. Mimi’s motivations are confusing, and it’s hard to sympathize with any of the characters. Perhaps that was the intention, but my sense was that the two intriguing plotlines, which could have fit neatly together, were diffused by distractions and uncertainties.

I didn’t get to many documentaries, but being a lover of Vivaldi’s vocal music, I had to see Argippo Resurrected. It’s the fascinating tale of how Czech conductor and musicologist Ondrej Macek ingeniously tracked down the lost 1730 opera, which had originally been composed for Prague. He then staged the piece in one of the two perfectly preserved court theaters of the era, the Castle Theatre at Cesky Krumlov, two hours outside of Prague, near the Austrian border.

The other is at Drottningholm, outside Stockholm, where in 1999 David and I had the privilege of seeing The Garden, a new opera about Linnaeus. (It was the first premiere at the theater since it was sealed in the 18th century.) The original candles have prudently been replaced by electric replicas of one candlepower each, flickering realistically. The Cesky Krumlov theater still uses real candles to light both the stage and the musicians’ stands. I guess this says something about fire codes in Eastern Europe. I for one would be happy to risk it in order to have a thoroughly authentic experience, especially if a Vivaldi opera was playing.

It’s a complicated story to fit into 62 minutes. Director Dan Krames took a clever and effective approach, starting backwards. He shows the theater first, with its wooden framework, sets, and stage machinery. He then goes on to introduce some of the musicians and singers, in the process explaining the concept of authentic performance style to those who may not be familiar with it. We also get to see some short excerpts from rehearsals, so that we come to know the opera a little. Only then does Krames proceed to the tale of Macek’s search for the original manuscript and his laborious piecing-together of the individual arias. Macek makes an engaging subject, though he is so self-deprecating about his discovery that the film has to include another musicologist to explain just how extraordinary the accomplishment was.

Finally Macek takes us on a tour of Venice, showing the few surviving places associated with Vivaldi, whose life is little documented. Along the way, there are further excerpts from rehearsal for the production shown, featuring a collection of excellent singers. Krames told me that Argippo Resurrected should be released on DVD in about a year. In the meantime, a live recording of Macek’s production is available as a 2-CD set.

Some final photos

Film festivals aren’t just for watching movies, of course. They’re for seeing old friends, meeting new ones, and sharing meals—including the festival’s wonderful hand-made waffles—to talk about what we’ve seen. As usual, David had his camera in hand nearly all the time, as the accompanying images show.

Theresa Ho, Eunhee Cha, and Tony Rayns: Three key players in the Vancouver Festival.

Chris Chong (director of Karaoke) and Liu Jiayin (Oxhide II).

Bob Davis, of American Cinematographer, and Noel Vera, Critic after Dark.

Canadian corner: Lisa Roosen-Runge, Shelly Kraicer, and Peter Rist.

Get your Terimayo, Oroshi, and Okonomi here: Japadog, a Vancouver Institution.