Archive for July 2015

Homunculus and his friends

Sappho (1921).

DB here:

Of the big-ass explosion movies, only two items in this summer’s spate of them have intrigued me. I liked Mad Max: Fury Road well enough, but not as much as MM2 and 3. I look forward to Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation, in a series for which I have much affection. As for the arthouse releases, the ones I’ve already seen are A Pigeon Sat… (good but not as sardonically bizarre as earlier Andersson, methinks) and About Elly. That one is a masterpiece.

I have stronger reasons than indifference for missing so much, and for tardy blogging besides. I’ve been on my annual trip to Belgium for research and lecturing in the Summer Film College. As a result, your recent movie experiences and mine have been divergent, perhaps even insurgent.

Apart from two screenings in the Brussels Cinematek’s Hou series (their restoration of Green, Green Grass of Home, gorgeous vintage print of City of Sadness), I spent the last four weeks watching 35mm prints of movies by Godard, movies starring Burt Lancaster, and assorted silent films from the 1910s and 1920s. I also re-met one of the most charming directors I know of, and in general had a hell of a time.

Today’s entry focuses on my archive work. Next up, a report on the Summer Film College.

Conrad’s many moods, mostly unhappy

Landstrasse und Grosstadt.

The archive stuff was recherché. I’ve been trying to see as many 1910s and early 1920s features as I could, but this time around I didn’t catch anything as mind-bending as Jasset’s Au pays de ténébres (1911) or Doktor Satansohn (1916) or Fabiola (1919) or I.N.R.I (1920), encountered on earlier visits to the Cinematek. I did get further confirmation that in Germany the “tableau style” exploited so vigorously in Europe and somewhat in America in the 1910s, was pretty much replaced by Hollywood-style editing by 1920. And I got some welcome doses of Conrad Veidt, another favorite in this vicinity.

In Die Liebschaften des Hektor Dalmore (“The Liaisons of Hektor Dalmore,” 1921), Veidt plays a callous playboy who keeps on retainer a man who looks very much like him. It’s a lifestyle choice. When a compromised woman’s father demands that Hektor do the right thing, he sends out his double to marry her. Surprisingly, the double isn’t rendered through trick photography. Richard Oswald, always a fast man with a gimmick, found a pretty good Veidt lookalike, which can’t be easy to do.

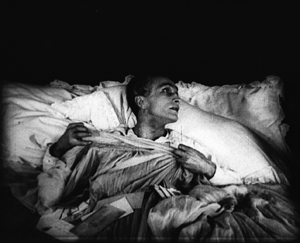

The hero’s Casanova complex carries him from dalliance to dalliance, and as you’d expect in a twins situation, there are confusions between the real and the fake Hektor. Fights and abductions liven things up. The climax is a duel in which the real Hektor, overconfident, learns to his grief that an outraged husband is a better marksman. The scene is handled through brisk shot and reverse-shot, garnished with an over-the-shoulder shot as Hektor aims his pistol. And there are dashes of mildly Expressionist set design (furnished by Hans Dreier). Veidt in a phone booth does the décor proud. But he doesn’t need fancy sets to project a feeling: on his deathbed, his expression and his clutching fingers show a man bereft of erotic illusions.

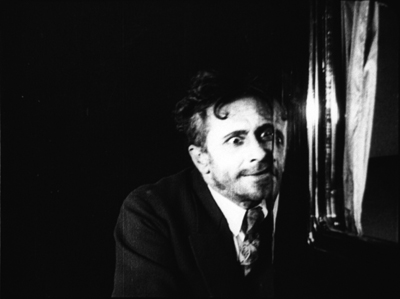

The other Veidt vehicle lacked doubles but not ambition. Landstrasse und Grosstadt (“Village and City,” 1921) casts him as Raphael, a wandering violinist who teams up with Migal, an organ grinder. They become a popular act in the big city, and as Raphael’s playing improves, Migal becomes his manager. Nadia, a woman who joins them, falls for Raphael and shares his success. But in an accident he suffers a hand wound and his career slumps. Migal sees his chance to move in on Nadia. Perhaps this shot gives you a hint of his designs.

Actually, most of Landstrasse and Grosstadt isn’t as hammy as this. A very nice shot shows Raphael in silhouette approaching a mansion to hear his rival Cerlutti give a salon concert. And of course Conrad gives the blind violinist a delicate, spectral pathos, as shown above.

Artificial man lurks in the shadows, destroys humanity

Sappho.

All the films I saw broke down scenes into many close shots, reminding us that Caligari (released 1920) probably wasn’t typical of German staging or cutting of that moment. It now seems to me almost consciously anachronistic, rejecting the reverse angles and precise scene breakdown that were becoming common. In Die Ehe der Fürstin Demidoff (“The Marriage of Fürstin Demidoff,” 1921), when a governess drags a recalcitrant girl back to her bedroom, the action is split up into four shots, all of different scales from close-up to long-shot.

Although I saw a fragmentary print of Sappho (1921), it’s clear that in parts it has the audacious monumentality of a Joe May production. The most staggering shot is that of the Opera surmounting today’s entry, but there’s no shortage of striking images. Above I include a shot of a madman that, thanks to window reflections, suggests his split-up psyche.

Sappho also doesn’t shirk editing effects either. During a frantic automobile ride, there are glimpses of hands on a steering wheel, a foot on brakes, panicked passengers, and POV shots through the windshield. Forty-nine shots rush by in a flurry, anticipating similar sequences in French Impressionist films like L’Inhumaine (1924). Feuillade was experimenting with rapid cutting of action at about the same time.

The most impressive, and nutty, film in this batch came from Homunculus, the largely lost German serial released through 1916 and into early 1917. The script was written by one of the blog’s favorite peculiar directors, Robert Reinert. The plot involves an artifical man created in the lab, à la Frankenstein’s monster. He’s a superman, in both strength and ambitions. The only surviving episode of the serial is Die Rache des Homunculus (“The Revenge of Homunculus,” 1916). (But see the codicil.) In this installment, posing as Professor Ortmann, Homunculus decides to drive humanity to destroy itself. He assumes a disguise to rouse the rabble, even inducing them to turn against himself in his Ortmann guise.

As in Expressionist drama, this overachiever is pitted against a crowd that, in the end, pursues him maniacally.

Director Otto Rippert gives us splendid mass effects in a quarry and along a beach, but there are also deep tableau images and sustained chiaroscuro, particularly in a showing the heroine Margot shrinking from Homunculus as he locks his rival in a dungeon.

Fans of Metropolis will notice that Rippert anticipates Lang’s unison choreography of crowds, as well suggesting that mob frenzy can create a sort of ecstasy in the woman who’s swept along.

In her book The Haunted Screen Lotte Eisner traces the films’ mass spectacle back to the stage work of Max Reinhardt and other theatre directors of the era. On the basis of this episode alone, Homunculus ranks with Algol and May’s Herrin der Welt as an example of big-scale fantasy in German silent cinema. Who needs Ant-Man when we have Homunculus?

Next time: Burt and Jean-Luc, together again for almost the first time.

Thanks to Nicola Mazzanti, Francis Malfliet, Bruno Mestdagh, and Vico de Vocht for their assistance during my visit to the Cinematek.

Kristin analyzes stylistic conventions of German cinema of this period in her Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available for download here). She’s written on Caligari here and here.

A so-so copy of Sappho is on YouTube.

On Homunculus, Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel, pp. 160-167. Substantial excerpts can be found here.

Munich archivist Stefan Drössler has recovered a mass of Homunculus footage and has assembled a version of the serial, which premiered last year in Bonn. Nitrateville has the story.

The Brussels Cinematek will release its Hou restorations on DVD early next year: Cute Girl, The Boys from Fengkui, and Green, Green Grass of Home. As a reminder, my video lecture on Hou is here.

The still below, taken as the prints were readied for the Summer Film College, points ahead to our next entry–number 701, as it turns out.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: A final entry

The courtyard outside the Cineteca di Bologna, during Il Cinema Ritrovato.

DB here:

Some initial figures are in, and they’re fairly stupendous.

There were about 85,000 admissions to all screenings of this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, which ended ten days ago. That figure includes the big public shows on the Piazza Maggiore, but the day-in, day-out screenings were heavily attended as well. There were 2500 or so festival passes sold. Assuming that those people stayed for four of the festival’s eight days and attended four shows a day, we can surmise that at a minimum 40,000 of overall admissions came from dedicated cinephiles surging from venue to venue. And of course many passholders stayed seven or eight days and squeezed in more than four viewings on each one.

Broiling heat—one day approached 100 degrees Fahrenheit—didn’t seem to keep many away from the films, panels, book talks, and other events that crowded the schedule. Between 9 AM and 1 PM, each two-hour block offered six to eight choices, and the afternoon blocks, running from 2:30 to about 8 PM offered even more. Now that the festival has another space, a nearby university auditorium fitted for DCP projection, a whole new column of events was slotted in. Below, a bit of the queue for the Isabella Rossellini interview in the auditorium.

Next year, planners are hoping to add screenings at a renovated 100-year-old theatre on the Maggiore. There seems no doubt that the Cannes of Classic Cinema will get even bigger.

For the first time, I felt the pace was a bit rushed. Getting together with old friends was somewhat harder than before, unless you came a day or so early. (Even then, there were tempting Maggiore evening shows.) But the atmosphere was still easygoing. The courtyard of the Cineteca was an island of steamy relaxation, boasting more tables than in past years. The tent cafe provided snacks and drinks for those who simply decided not to be obsessive. Even I stopped and sat down, twice.

Word is out. A new wave of young film lovers has discovered Ritrovato. What had been dominated by hip (or hip-replaced) baby boomers was now teeming with students. The festival has added a Kids section and another devoted to older teens, and it was a pleasure to see them winding through the corridors of the Cineteca. The World Press has finally woken up too. The Guardian ran a rapturous encomium. Loyal blog sites such as Photogénie provided extensive coverage.

Just speaking for us, this was the first year Kristin and I had almost no time to blog during the event. Hence this, the last of our catch-up entries. (Click back for the earlier ones.) And I will leave out a lot.

All in favor of film, raise your hands

Has everything been said about digital cinema and its differences from photochemical cinema? Maybe so. Nonetheless, the two panels I visited on the subject raised a lot of intriguing points, in quite different formats.

The first session compared 35mm prints with digital restorations. Through clever maneuvering, the Ritrovato boffins were able to switch back and forth between versions as both were running, and the results were pretty compelling. Schawn Belston of Twentieth Century Fox provided a sample of Warlock, a twenty-year old print. It was contrasty but had saturated color; this was the sort of image I remember seeing in theatres. The digital restoration, a work in progress, was paler, with sharper edges, more solid-black shadows, and a more pastel color design. Pretty Poison was a much newer print, on Vision stock, and looked fine, as did the DCP.

Grover Crisp of Sony brought a Kubrick-approved print of Dr. Strangelove, considered best-quality in 1990s. He ran it in tandem with the recent 4K restoration managed by Cineric. The difference was very striking. For black-and-white, at least, the DCP seemed to me to have all the better of it. Kubrick, a major otaku on matters photographic, would I think have approved.

Further proof of the Crisp-Sony finesse was available in the utterly dazzling DCP we saw of Cover Girl (1944) on the big Arlecchino screen. I was surprised to find some of my circle disdaining this movie, but I think it’s wonderful. It seems to me a rough draft for many of Gene Kelly’s MGM pictures, from the trio boy-girl-stooge we get in Singin’ in the Rain (with Phil Silvers as Donald O’Connor) to the mind-bending doppelganger dance that looks forward to Anchors Aweigh and Jerry the Mouse. I also like the clever motifs of feet and faces, and the flashbacks, and …well, I must stop, because I expect to use Cover Girl as a major example in my still-unfinished book on Hollywood in the 1940s. Suffice it to say that I have never seen a better DCP rendering of Technicolor than was on display in Grover’s new edition.

Davide Pozzi rounded out the session with a pairwise comparison of different versions of Rocco and His Brothers. A vintage print from the camera negative had been vinegared, so the shots had rippling focus; the DCP restoration was fairly sharp and bright. This was a real work of reclamation.

The panelists agreed on a lot. Don’t try to banish grain; film is grainy. Don’t expect to match everything. No two prints ever looked alike anyhow, and variations among screens, lamps, and other exhibition factors don’t let us capture a pristine original experience. Because of the advances of digital restoration, there are new frustrations. Archivists are aware that older restorations may not look good today, while cinephiles who forgive scratches on “vintage” 35mm copies howl if a restoration doesn’t look smooth as silk.

Film has many futures. Pick one.

Serge Bromberg introducing the Lobster Films anniversary program, which included several “faux Lumières.”

Another panel, “The Future of Film” (let’s ban this as a title, shall we?), was less focused but more provocative. No fewer than fifteen critics, archivists, manufacturers, and filmmakers gathered before a standing-room crowd to discuss the prospects for the photochemical medium formerly known as film.

The panel’s speakers worked in shifts, three at a time. Everybody was lucid and brief. Some general points:

On the manufacturing front, Kodak and Orwo are committed to producing motion-picture stock. Christian Richter of Kodak noted that in 2006 his firm produced 11.8 billion feet of motion-picture film, while last year it produced only 450 million feet. The demand may be plateauing, but it’s too soon to be sure. The crucial problem may be the absence of labs, although boutique labs are starting to appear.

Some filmmakers, such as Gabe Klinger, consider film an essential part of their aesthetic. Alexander Payne prefers to shoot on film, but more important is film projection. He restated his view that “flicker will always be superior to glow.” By contrast, archivist Grover Crisp proposed that the standard of film projection had sunk so low that he prefers to see digital presentations, although those too can be substandard.

Some archives are preserving on film recent movies, including those shot digitally. Sony does, as does the CNC. Eric Le Roy reported that all French films receiving subsidy must deposit a print and the negative there, even if the project originated digitally. Mike Pogorzelski of the Academy archive spoke of the ongoing “Film to Film” effort, begun in 2012.

More generally, two archivists argued that the future of film lay in museums. José Manuel Costa of the Portuguese film archive argued that the basic principle had to be a respect for the nature of the medium. Cinema has changed, but it has existed in a specific technological environment since the nineteenth century, and it’s the mission of a film museum to retain that technology as long as possible. Accordingly, a film should be shown in the format in which it was made.

Belgian film archivist Nicola Mazzanti (on left above, with Pietro Marcello and Alexander Payne) seemed in accord. He remarked, in the wake of the earlier session, that digital treatment, or film restoration generally, can’t duplicate tinting, toning, stencil color, Technicolor, and other older processes. The originals are what they are—imperfect—but that imperfection is inherent in their material history. More acutely, the world outside the archive is entirely digital, so it will be a big task to keep analog alive. It will take money. And no European archive’s budget equals the cost of a single season of La Scala.

Scott Foundas, who chaired the sessions with easy good humor, indicated that perhaps the state of play was this. Digital capture and storage would not wholly replace film. By now film is recognized as distinct and worth its own attention. It’s going to exist alongside digital media for some time to come, although in niches and in more rarefied forms than before; like vinyl records.

Bologna, it became clear, is one of those places where film will continue to flourish. Fifty percent of screenings this year were analog, and the programmers included showings of Vertigo, The Heroes of Telemark, All That Heaven Allows, and other titles on “vintage” prints from earlier eras. Audiences packed in to see them and cheered.

What they saw, we must see

With all the talk of film’s enduring powers, two screenings reminded me of the power of photochemical recording as a record of history, both en masse and individual.

German Concentration Camps Factual Survey was overseen by Sidney Bernstein and involved several skilled filmmakers, including Hitchcock. It was designed to be shown to the German people as a record of what they had ignored over the last dozen years. But it remained unfinished when it was shelved in 1945.

In recent years the surviving reels have been shown occasionally under the title Memory of the Camps. In 2008 several staff at London’s Imperial War Museum began to restore the original and fill out the final reel. The filmmakers added a new recording of the original commentary, previously not attached to the footage.

Friends of Andy Warhol often commented that he used his ever-present Polaroid to keep his distance from his surroundings. You wonder if a similar strategy didn’t insulate, to some minimal degree, the American, British, and Russian cameramen who filmed the liberation of the camps. Their images show shriveled corpses covering the ground, flung into pits, shoveled into heaps. Spindly survivors move like ghostly marionettes. When I saw the first images of the bland camp officials smoking and chatting under guard, I immediately wondered: What self-control it must have taken not to have killed these men on sight.

The film is structured as a sort of anti-Grand Tour, starting in Bergen-Belsen, where SS officers seem genuinely annoyed at being forced to clear out the dead. The film moves eastward, guiding us by maps, to end in the abandoned Nazi extermination camps built in German-occupied Poland. Here shoe brushes, spectacles, and children’s toys fill warehouses. The names of German companies proudly adorn ovens.

One of the film’s main points, apparently suggested by Hitchcock, is the fact that the camps existed very close to population centers. Did the people celebrating Oktoberfest in Munich ever think of Dachau, half an hour away by train? Did the people breathing the mountain air of Ebensee spare a thought for the camp nearby? Arriving Allies insisted that people from surrounding towns be brought to witness what they had ignored. In the footage, men, women, and children file by the carnage.

Some seem moved, but eerie shots show town elders standing stiff and impassive before heaps of bodies.

Toby Haggith, one of the film’s restorers, was on hand for a follow-up session, something really demanded by the intensity of the experience. He answered questions with great seriousness and eloquence. He explained that the restoration team had decided to leave in the film’s original errors, based on contemporary reports of the size or uses of certain camps, as well as the film’s avoidance of focusing on Jewish victims. The film stresses the Nazis’ crimes against humanity at large, an emphasis, as Haggith pointed out, in tune with the United Nations initiative of the moment. “The very historicity of the film is what seizes us.”

Godard has suggested that there must be footage of the day-to-day running of the camps. Would the society that devised Agfa film and Arriflex cameras have failed to document the industrial-scale slaughter of which the Reich was so proud? Were there no amateur cineastes among the SS-men leading comfortable lives in their cottages? Was there no Leni Riefenstahl to cheerfully lend credibility to these charnel houses? Even if such footage exists, German Concentration Camps Factual Survey will serve as an unforgettable reminder that humans have a terrifying gift for brutality, and for ignoring horrors enacted right beside them.

Many doubts, much faith

Visita ou Memórias e Confissões.

In 1982, financial setbacks forced the Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira to sell the house he had lived in for forty years. Before leaving, he decided to record his affection for the place. The result, Visita ou Memórias e Confissões was the quietest film I saw at Ritrovato. It was also one of the best.

We start at the gateway, coming in as if guests. But who owns the voices we hear? The murmuring man and woman who seem to be our surrogates passing along the path? We never see them as they enter the magnificently curvilinear house. But is it right to say they? Although we hear two voices, we hear only one person’s footsteps. The somewhat whimsical uncertainty that haunts so many Oliveira films is summoned up here by the simplest of means.

Eventually Oliveira greets us, standing in his study before his typewriter, and he explains some of the house’s history. He also runs some footage on a 16mm projector that coaxes him into discussing death, women, virginity, and sanctity. “I’m a man of many doubts and much faith.” Occasionally we hear the couple whispering as we coast past art objects and family pictures.

Oliveira tells us of his 1963 arrest while making Rite of Spring and his 1974 conflict with workers in his family’s factory—a tumultuous event that, we learn rather late, is the cause of his financial distress. These revelations come in the midst of a fascinating account of his family, accompanied by a tribute to his wife, to whom the film is dedicated. Individual history and social history blend in his recollections and the flow of visual memorabilia.

The spectral visitors glide out with us, and the film that Oliveira has been showing halts, leaving us a blaring white frame. According to his wishes, Visita wasn’t shown until after his death. Perhaps in 1982 he expected that event to come rather soon; he was seventy-three, after all.

He couldn’t have known, surely, that he would live another thirty-three years and make twenty-four more films. As José Manuel Costa pointed out, the great director wanted the film to be shown posthumously not as a final boast, but rather a wry, modest memoir of an exceptionally full life. By turns ironic and confessional, Oliveira’s testament demonstrates that we can be moved by a soft-spoken, patient peeling back of layers of the past.

Of course it was shown on film.

Kristin and I thank the many staff members who make Ritrovato such a wonderful experience. Special thanks to Gian Luca Farinelli, Guy Borlée, and Cecilia Cenciarelli. We are particularly grateful to Marcella Natale for her many moments of assistance, including giving us preliminary attendance figures.

German Concentration Camps Factual Survey will play several film festivals and public venues during the rest of the year and will eventually be distributed on DVD. Night Will Fall (2014), André Singer’s documentary on the making and restoration of the original film, is already available.

P.S. 31 July: Danny Kasman has an illuminating interview with Toby Haggith on the Factual Survey, along with important background information, at Cineaste.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: revelations from India and Iran

Pather Panchali

Kristin here:

The second half of my week at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna was centered around two Asian events: a small program of Iranian films from the 1960s and 1970s and the restored Apu trilogy. In between those screenings I tried to fit in some programs of pre-1920s cinema.

Bringing the Apu Trilogy back from the ashes

That was the title of a panel presentation during the festival, one which I missed because I was watching the first of the four Iranian films. In this case the metaphor is literal. The original negatives of the Apu films were stored in a London warehouse, and in 1993 a fire damaged them extensively.

In 2013, The Criterion Collection and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences began a collaborative restoration. Working meticulously by hand and employing an innovative rehydration technique, experts at L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna rescued the images for about 40 percent of Pather Panchali and 60 percent of Aparajito. The negative of Apu Sansar (The World of Apu) was wholly lost. For it and the missing parts of the other two films, footage from fine-grained masters and duplicate negatives from various archives was used. The restoration was done in 4K. (For an interview with Lee Kline, Criterion’s technical director, see here. There is a short but informative short film on the restoration, including some before-and-after comparisons, on Vimeo.)

The result is spectacular, far better than one would expect, given the dire circumstances the restorers faced. It was a privilege to see the entire trilogy over three days on the huge screen of the Cinema Arlecchino from the front row. There were times when the replacement footage was obvious, but for the most part, the images look pristine. They also look like film, with no hint of video-y quality about them.

I had seen the trilogy only once, in 16mm back in my graduate-school days. At the time, I admired it but wasn’t bowled over. Sitting through the Ritrovato screenings, I found it a profoundly moving and beautiful experience. Satyajit Ray manages both to maintain a quiet, leisurely pace and to compress the hero’s life, from birth to early adulthood, into three parts totalling less than six hours.

Apu’s strict but devoted mother (below left, in Aparajito) anchors the first two films, gaining our sympathy despite her scolding and worrying. Apu’s wife, Apurna (below right, in Apu Sansar), is in the third film for a remarkably short time. Yet we quickly come to understand her love for this unknown man whom she marries almost by accident, her sense of humor, and her compassion, all of which are vital to our sympathy for Apu’s utter devastation after her death. Indeed, the trilogy involves five major deaths, all of which makes the hopeful ending the more affecting.

Presumably The Criterion Collection will bring out a Blu-ray set of the three films, though no date has yet been announced.

Iran’s own New Wave

Admirers of Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Asghar Farhadi, Jafar Panahi, and other notable directors of the Iranian cinema of the past few decades might be curious about their forerunners. Iranian film critic and historian Ehsan Khoshbakht has begun to satisfy that curiosity by programing a short series of classics of pre-Revolutionary cinema. According to his program notes (available in their entirety online), the four films shown in Bologna constitute about a quarter of the output of the Iranian New Wave. I hope there will be further screenings at future festivals.

As Khoshbakht warned in introducing the earliest film in the series, Shab-e Ghuzi (Night of the Hunchback, 1965), it is not a masterpiece and certainly not a forerunner of the filmmaking that would later bring Iran to prominence in international festivals and art cinema. Director Farrokh Ghaffari was a pioneer of Iranian filmmaking beginning in the 1950s, but he is perhaps equally important in having started the first Iranian film archive.

Night of the Hunchback is a black comedy with a story loosely derived from The Trouble with Harry. A player in a cheap entertainment troupe is accidentally killed, and the bulk of the film follows his corpse as it is passed from one group of characters to another; these include a pair of smugglers running a beauty salon, who provide much of the film’s humor (above). Most try to dispose of it, but a society woman trails it in the hope of retrieving an incriminating document in its jacket pocket. By Western standards it seems like a fairly mainstream commercial work, but it departed from commercial Iranian cinema, according to Khoshbakht, “with its respect for folklore and its bitter portrayal of the upper class.” It was a commercial flop but gained some attention at European film festivals.

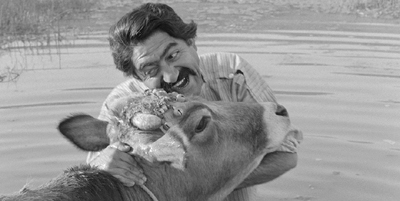

The most famous film of the era is Gaav (The Cow, dir. Dariush Mehrjui, 1969). It centers around Hassan, the owner of his village’s sole cow. He dotes on the beast, as is quickly established in an early scene when he affectionately bathes her.

When the cow mysteriously dies (a cause is hinted at but never confirmed), the villages lament the loss of their only source of milk, but they also worry about how Hassan will react when he hears the news.

Although Hassan is the evident protagonist of the film, the drama centers more around the ignorance, lack of judgment, and even cruelty of the villagers. The film begins not by introducing Hassan and his cow but with a disturbing scene of the local children chasing and tormenting a mentally defective young man. This establishes the tone for several later scenes.

When the cow’s death is discovered, the small group of men who wield authority initially concoct a story of the cow having run away, and the villagers bury the carcass (bottom). As Hassan descends slowly into madness, the people supposedly trying to help him make every possible wrong decision, leading to disaster.

If the films I discussed in my previous entry extolled the virtues of village life and represented leaving home as unwise, The Cow is just the opposite. Cut off from the outer world, the villagers have little education or ability to come up with logical solutions to problems. It’s a theme repeated in the other two Iranian fiction films on the program as well.

Yek Ettefagh-e sadeh (A Simple Event, dir. Shrab Sahid Saless, 1973), the latest of the films shown, seems the most obvious forerunner of the wave of Iranian cinema that started in the 1980s. It closely follows the daily routine of a young, unnamed boy living in a small town on the edge of the Caspian Sea. We see him at school, helping sell the few fish that his father catches each day, eating and trying to study in the almost unfurnished house he shares with his father and sickly mother.

There’s little dialogue, apart from scenes in the school. I believe the boy speaks two lines in the entire film, and his father communicates with him only occasionally, to order him around: “Close the door” or “Study.” Much of the action consists of the boy running through the streets on errands, including his night-time visit to fetch a doctor for his ailing mother (below).

Although there’s a superficial resemblance between A Simple Event and the later films of the “child quest” genre, I see considerable differences as well. In films like Kiarostami’s Where Is My Friend’s Home? or Panahi’s The Mirror, the child protagonists have clear-cut goals which they have decided upon themselves. They are stubborn and determined, and as they doggedly pursue their goals we are never unsure about their motives.

In A Simple Event the boy has no goal, and we learn almost nothing about his character. Is he really as stupid as his teacher believes, or is he behind his classmates because he gets little chance to do his homework? Does he love his mother or is he indifferent to her declining health? Is he resentful but cowed by his elders? Or is he resigned and accepting of his lot? We have no way of knowing. His one independent action is to buy a bottle of Coca-Cola to go with his usual meager meal after his father uncharacteristically gives him a little money.

There’s certainly a suggestion, once again, that small-town life is deadening to people. The rote learning and lack of relevance in the subjects taught in school help explain the lack of imagination and the resignation to their situation among the students.

My suspicion is that later directors may have seen the potential in A Simple Event and built upon it, introducing a greater empathy with their child protagonists and certain greater drama and suspense.

To me, the surprise among the Iranian films was Oon Shab Ke Baroon Oomad Ya Hemase-Ye Roosta Zade-ye Gorgani (The Night It Rained or the Epic of the Gorgan Village Boy, dir. Kamran Shirdel, 1967). It’s a  sophisticated investigative documentary that reminded me of the work of Erroll Morris.

sophisticated investigative documentary that reminded me of the work of Erroll Morris.

The film begins with a written report on the making of the film itself, submitted to the authorities by Shirdel. It seems to describe earnest attempts to document an inspiring story that had been widely circulated in newspapers. On a rainy night, a boy in the village of Gorgon had discovered that flooding had undermined the local train tracks; he signaled an oncoming train by setting his jacket alight, successfully stopping it and saving 200 passengers’ lives.

Doubt begins to creep in, though. Among the many newspaper titles shown trumpeting the boy’s feat, we find one calling it a pack of lies. Shirdel’s report indicates that his team could not find the boy and set out to interview various people. Gradually it becomes apparent that the whole story was concocted and that the train–a cargo train with no passengers aboard–was stopped by local railway officials. Throughout the film, there are further passages from the production report, describing the filming work as if it were for a simple, laudatory documentary about the heroic boy. We see, however, that much of the filming undermines that heroism and satirizes the government’s willingness to perpetuate false accounts of it.

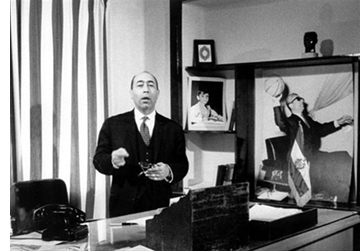

Shirdel carefully avoids making that point explicitly. He intercuts interview scenes, some of the boy rattling off his story and some of newspaper editors defending the story (above). In other scenes, we hear from indignant railway officials and an editor who dismisses the incident as pure fiction. The director seems to let us decide on the truth, but the the absurdity of boy’s supposed heroism becomes increasingly apparent.

Not surprisingly, Shirdel’s film was banned. Six years later, according to the program notes, “it was deemed harmless. It was then premiered at the Tehran International Film Festival where it won the Best Short Film award.” Clearly the officials who cleared it for release missed the ironic underpinnings of the film.

The Night It Rained (and perhaps others of Shirdel’s films) may have offered a model of reflexive filmmaking that later directors picked up on. Close-up, The Mirror, Salaam Cinema, and Through the Olive Trees all bring filmmaking into the stories they tell.

Thanks to Ramin S. Khanjani for some corrections concerning the Iranian section of this entry. His article on The Night of the Hunchback, “Actors and Conspiracies,” was published in Film International 15, 3/4 (Autumn 2009/Winter 2010): 66-71.

The Cow.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: Back to the future (of movies)

DB here:

The Teatro Comunale of Bologna is an eighteenth-century opera house that was launched by a premier of a work by Glück. It has hosted massive productions of Wagner, Rossini, and Verdi, and was a favorite venue of Toscanini’s. Elegant and imposing, with box seats and an orchestra pit, it makes you feel like you’re in Senso or Liebelei.

In some years Cinema Ritrovato has secured the Teatro for gala screenings of silent films, complete with orchestral accompaniment. One show of Lady Windermere’s Fan was a delight. In another year, the hammering Meisel score for The Battleship Potemkin nearly blasted me out of my seat. I was sitting up front.

This year it was Rapsodia Satanica (1917) that got the Comunale treatment. This apparition has lost none of its exuberant morbidity, and we got to watch it with the original Pietro Mascagni score. Timothy Brock found that the original orchestra parts were lacking hundreds of tempo changes, because Mascagni himself conducted during screenings and never inserted them. Through careful testing against the film, Brock managed to create a score that brought a packed Communale audience to its feet cheering. One more testament to the power of 1910s cinema.

1915 and all that

Assunta Spina (1915).

I tried, really tried, to see other wonders from all the places and periods on display at this year’s overstuffed Ritrovato. But because of my love of ‘teens films, both American and not, I kept coming back to as many items from that era as I could squeeze in.

There was, centrally, the series Cento Anni Fa (A Hundred Years Ago), curated by Marianne Lewinsky and Giovanni Lasi. 1915 was, of course, a decisive year in American cinema, to be forever identified with Griffith’s monumental The Birth of a Nation. Standard histories would have it that this was the stroke that revealed the artistic power of cinematic storytelling. Griffith’s colossus was naturally very influential, but it wasn’t an isolated accomplishment. Earlier films, such as Weber/Smalley’s Suspense (1913), and other 1915 films–De Mille’s The Cheat and Walsh’s Regeneration in particular–are more typical stylistically of what Hollywood silent cinema would turn out to be.

Add to this list another 1915 item. If film history were an exercise in fairness, Reginald Barker would be recognized as one of the directors who set American filmmaking on its “classical” road. Working under Thomas Ince’s supervision, Barker showed a flair for economical framing, frequent changes of setup, and bold cutting within scenes. His Typhoon (1914) is at many moments more nuanced in its analytical editing than Birth.

1915 was a fine year for Barker. He turned out the long-praised The Italian (shown in the series), as well as the dynamic Civil War drama The Coward, along with superb William S. Hart westerns like On the Night Stage.

So The Despoiler, another Barker from 1915, did not disappoint. It survives only in a cut-down French print, but it still packs a sensational punch.

The original, according to a contemporary review, involves a border war in which troops invade a small town. The leader of the dark-skinned horde fastens on one beautiful woman, who has taken refuge in a nunnery. She is about to sacrifice herself to save the others, when the colonel learns that she is his own daughter. She is saved, and at the very end the whole thing is shown to have been a dream. The French version Châtiment (“Punishment”), painstakingly restored by the Cinémathèque Française in 2010, was modified to fit propaganda demands of the war period. Here the daughter really gets raped, and she shoots her attacker. The colonel turns his troops loose on the nunnery, but halts them in time when he realizes who the victim is. No dream stuff here.

Barker’s style is fluid, and he builds great suspense when the daughter, barely recovered, prepares to shoot her ravisher with his own pistol. The scene has judicious depth staging, as when the soldier lies drunkenly on the cot but he’s blocked by the woman’s gradual decision to use the weapon. At the proper moment she swivels aside to reveal his head lolling in the background.

The match-on-action when the woman turns and pulls up her sleeve is more perfect than many such cuts in Griffith’s films. She then strides to the background to give us a full view of her target.

A brief shot of the daughter’s attacker is replaced by a 3/4 view of her drawing a bead on him, with Jesus taking her side.

Other countries’ 1915 output wasn’t ignored. We got Denmark’s Revolutionary Wedding, proof that August Blom had not given up the somewhat rigid version of the tableau style he had used in Atlantis (1913). More florid were the Italian offerings. Assunta Spina (lovingly restored by Bologna’s own Cineteca and now available in a DVD), is a classic of the nation’s silent cinema. It was treated to a carbon-arc projection one evening in the courtyard. The less-known but no less flamboyant Il Fuoco (“The Fire”) is a melodrama about a rich woman who destroys a naive, passionate painter.

The two films are famous for showcasing the divas Francesa Bertini and Pina Menicelli respectively. But they’re just as important as powerful illustrations of the variety of 1915 pictorial styles. Assunta Spina is a triumph of tableau staging. By contrast, the opening of Il Fuoco, detailing the first encounter of the owl-woman and the burly artist, is as rigorous a piece of editing that I’ve seen anywhere at the period. Assunta Spina fills the frame with layers of depth (above and first still below). Il Fuoco makes play with bold optical POV, especially when the painter is transfixed by his languid model.

To which one can only say: Zowie.

Bluebirds of happiness

Back in the 1980s I wanted to see some films from Universal’s Bluebird Photoplay series. It had been accepted wisdom that the Bluebirds were among the first American films seen in Japan, and accordingly they had influenced Japanese filmmakers. My searchings led me merely to fragments at the Library of Congress. But today, according the Ritrovato’s indispensable catalog, about thirty complete titles have been found in archives. The most famous, Lois Weber’s Shoes (1916), screened at Bologna in 2011.

The Bluebird franchise was identified with feel-good stories, often rom-coms centered on women and derived from fiction by women. Mariann Lewinsky points out that the unit was a training ground for Rudolph Valentino, Mae Murray, Tod Browning, Rex Ingram, and several other notables. A striking number of Bluebirds were directed by women, in particular Elsie Jane Wilson. About 170 films were produced under the logo, and Hiroshi Komatsu’s catalogue entries confirm that they had a powerful impact on Japanese fans and filmmakers.

Four Bluebird titles, all discovered at the French CNC archive, confirmed the ingratiating charm attributed to the brand. Little Eve Edgarton (1916) centers on a botanist daughter who’s whip-smart in science. Her father tries to marry her off to an older colleague, but she resists. The Love Swindle (1918) is more elaborately plotted. The main couple meet cute during a comic home invasion, in which Diana Rosson proves better at defeating hungry tramps than Dick Webster, who gets conked out trying to protect her. After a date, Dick decides Diana’s too modern and highbrow for him. Diana, undaunted, takes a room in a pension and masquerades as her own impoverished sister, Miranda. Dick naturally falls for Miranda.

Here again, the polish and inventiveness of ‘teens Hollywood comes through. Stylistically, we find nearly everything characteristic of classical presentation: scene analysis, angled shot/reverse shot (though no over-the-shoulders), surprising camera movements, expressive low and high framings. In narrative terms, our heroines conceive goals and pursue them tenaciously. Rosamond in The Dream Lady (1918) even makes a list of her four aims in life. Getting a house is surprisingly easy; marrying a real gentleman takes a little longer.

There are as well ambitious storytelling gambits. At one point in The Dream Lady, an orphan girl imagines that she has a mother and lives in nice surroundings. Director Elsie Jane Wilson cuts freely between the girl’s fantasy and Rosamond looking in on her. One startling cut matches on the girl’s gesture of flouncing her ribbon, taking us between dream and reality. (It’s actually a cheat–wrong arm–but perhaps the change of angle covers the disparity. Sort of like here.)

Then there’s the plot of The Little White Savage (1919). It starts with a circus boss and his sidekick telling customers how they acquired a star attraction, a wild girl purportedly from an island on no maps. The flashback yarn is absurd from the get-go, and it gets wilder as it proceeds, as the heroic sidekick somehow goes from he-man adventurer to pious parson. In a surprisingly salacious passage, Minnie, escaped from the sideshow, hops into the clergyman’s bed. They squeeze and nuzzle unashamedly as nosy townsfolks watch in horror.

It’s all a tall tale, of course, confirmed when the frame story reveals Minnie as simply a cute modern girl. The Confession (Fox, 1918), hinged on a more serious lying flashback and may have supplied the premise for The Little White Savage. Again we find the 1910s as an era of fertile innovation. “Its breezy bold difference makes it worthwhile,” wrote a critic of this Bluebird release. “What Paul Powell and scenarist Waldemar Young have done here is the sort of adventure that makes screen progress.”

A bigger-budget Universal release served as pendant to the Bluebirds. Lois Weber’s Dumb Girl of Portici (1916) was a collaboration with dancer Anna Pavlova. A truncated version had long lain at the British Film Institute, but Geo Willeman and Valerie Cervantes found a 16mm print at the New York Public Library. That enabled them to create a very pretty, nearly-complete version, which now concludes with a lengthy Pavlova dance. The super-production, now running nearly two hours, was based on Daniel Aubert’s 1828 opera and offers some ambitious spectacle.

As a prestige entry with crowd scenes, lavish sets, and one of the stage’s top stars, it’s about as far from the humble Bluebirds as you can get. It’s notably stiffer and less dynamic too; what is it about costume pictures that makes for an academic approach? Still, The Dumb Girl of Portici and the Bluebirds exemplify the ways in which filmmakers of the period laid down many paths of exploration for the future.

The devil you know

I first saw Rapsodia Satanica some years back during a Brussels visit. I liked it fine, but seeing it with tinting and hand-coloring, on the big Comunale screen, with a live orchestra convinced me that it really needs its score. The plot is thin, but with the music throbbing along with its heroine’s seductive pirouettes and mournful drifting, the whole thing makes powerful cinema. It was in fact billed as a “Cinematic-Musical Poem,” suggesting that here lyricism will dominate.

With the score tightly matching fluent acting, I’m reminded of a point Kristin made some years ago. She wrote about the ‘teens as an era in which many directors opened up new domains of cinematic expressivity. Having developed effective methods of storytelling, they began looking for techniques that would deepen the emotional impact of the action. Rapsodia satanica is practically a case study for this tendency.

Countess Alba sells her soul to regain youth. One of her suitors kills himself, the other flees. She winds up alone on her estate. This simple story is elaborated through many techniques of mise-en-scène. There are the dancelike performances; Satan practically coils himself around his victim’s calf. There are the costume changes, as Alba moves from her heavy dowager dress to diaphanous veils in her voluptuous phase, and then, in her solitude, a simple shift. When she thinks the surviving lover is about to return, she wraps herself in the veils she wore before. Even the hand-coloring adds impact; as in the pair of stills below, often Alba’s dress is the only colored mass in the shot.

The hallucinatory images gain both precision and passion from the soaring score. Our heroine sells her soul to Satan in exchange for a return to youth. The moment when she sheds her elderly skin and emerges, like the butterfly we’ll see later, as a ravishing beauty is accompanied by a motif that exfoliates just as lushly. An offscreen pistol shot is prepared by a driving crescendo, but the orchestral outburst is still startling. The countess registers the realization that one lover has killed himself, and diva Lyda Borelli synchronizes her attitudes with that climax: body clenched at first, then sliding toward a more doleful pose.

At forty-two minutes, Rapsodia Satanica is practically, as Gian Luca Farinelli remarked in his introduction, an experimental film. Its unsettling use of multiple mirrors, trapping the heroine in fractured reflections, sets up Charles Foster Kane’s zombie-like passage through his palace. The film’s second part, in which the heroine drifts through landscapes and enormous rooms, looks forward to the American “trance films” of the 1940s and the Cinema of Walkies, from Neorealism and Antonioni to Tarkovsky. In all, the film lets us recognize the persistence of some trends across film history, and appreciate that the 1910s are not as far away as they might seem.

Thanks to Guy Borlée and Cecilia Cenciarelli for help with this entry.

The immense catalogue of this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, essential for background to the screenings, can be purchased here. There’s a pdf for reading or downloading here. These folks think of everything.

For contemporary accounts of The Despoiler, see the Lantern pages here and here. The Cinémathèque Française webpage provides a detailed explanation of the restoration. The Photoplay review of The Little White Savage is here.

You can read more about Bluebirds at Adrian Curry’s “Poster of the Week” site on mubi, from which I took the Bluebird logo above. Be sure to scroll down to enjoy the gorgeous designs on display.

For more on why the ‘teens are crucial, see the Vimeo talk, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” On continuity editing, you might start here; on tableau staging, here. Kristin’s article is “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp, eds., Film and the First World War (1995).

Rapsodia Satanica.