Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Amazon Doesn’t Own James Bond—Yet: Making Sense of the 007 Franchise. A guest post by Colin Burnett

Kristin here:

Students and faculty in the film-studies division of the Department of Communication Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison are known for aesthetic analysis of films and historical study of the film industry. One aspect of the latter has been the study of franchises. Long ago Henry Jenkins coined the term acafan, defined as someone who is a fan of what he or she studies but also produces academically solid publications on it. His Textual Poachers (1992, second edition 2012) became a classic in the study of fandoms. His Convergence Culture (2008) examined the relationship between fandoms and film, television, and other media franchises.

Henry studied under David here at the university. I think it’s safe to say that David was also an acafan when he wrote about Asian action cinema in Planet Hong Kong (2000, second edition 2011, available as a PDF here). I, too, admitted to being an acafan when I wrote my study of Peter Jackson’s (or should I say New Line’s) Lord of the Rings films in The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (2007).

In 2016 I took a look at the continuation of the LOTR franchise, which was still going strong then and is still going strong now. No doubt next year, when we reach the twenty-fifth anniversary of the release of The Fellowship in the Ring, there will be considerable exploitation of re-releases and yet more licensed products.

More recently Colin Burnett, another of David’s students, known for his study of Robert Bresson, has turned his enthusiasm for the James Bond franchise into a research project. I am happy to see him discovering shifts in control of the film and merchandising rights that somewhat parallel those in the LOTR franchise, most notably with Amazon’s ambitious prequel series, The Rings of Power. Thanks to Colin for contributing an entry dissecting and clarifying the recent Variety article announcing Amazon MGM’s acquisition of the Bond film franchise.

Amazon Doesn’t Own James Bond–Yet

In a development that has shocked the entertainment industry, Amazon MGM announced on February 20, 2025 that it had taken over “creative control” of the James Bond film franchise. What exactly does this mean, and why is it so shocking?

Reporting on the news has tended to overlook some crucial details about the structure of the Bond franchise, a factor which in turn has colored the speculations of commentators and fans. Variety’s February 20 headline, for instance, alleges that “Amazon MGM gains creative control of 007 franchise.” This simply isn’t the case.

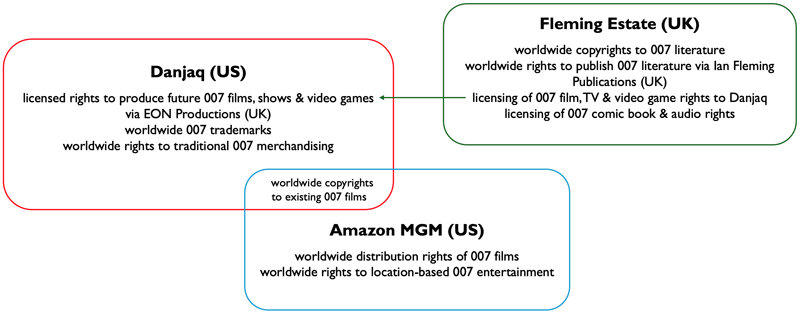

The Bond franchise is configured as a shared rights and licensing network (above). For decades, even prior to Amazon’s acquisition of the studio in 2022, MGM has owned the worldwide distribution rights of the Bond films, as well as shared copyrights for the existing Bond film titles. The new pact, which some price at $1 billion (unconfirmed), gives Amazon MGM the power to manage the artistic direction of the film series for the first time, and thus presumably a controlling stake in a company called Danjaq.

How did we get here?

Danjaq/EON Productions’s shifting media franchising strategy

Until now, production of the film series has been in the able hands of the Broccoli family. In 1961, producers Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli and Harry Saltzman optioned Ian Fleming’s novels and formed Danjaq, a rights holding firm initially based in Switzerland (now in the US). To produce their Bond film series, Broccoli and Saltzman acquired the small British production company EON Productions, allowing them to benefit from British tax breaks and subsidies. They also formed a partnership with Hollywood studio United Artists (UA) to finance and distribute their projects. Over the years, there have been changes here and there—MGM acquired UA in 1981, and Broccoli’s stepson Michael G. Wilson and daughter Barbara Broccoli took the reins of EON/Danjaq in 1995—but the EON/MGM arrangement has remained relatively stable.

The decades-long partnership between EON and MGM has always favored the Broccolis. Through EON, they shaped the creative direction for the series, and through Danjaq, the Broccolis managed the copyrights for the cinematic Bond and the global Bond trademarks. But when the multinational technology company Amazon purchased MGM in March 2022, it acquired considerable leverage in the Bond franchise. Almost immediately, tensions began to surface between EON and MGM. The longtime partners couldn’t agree on the next steps for the series.

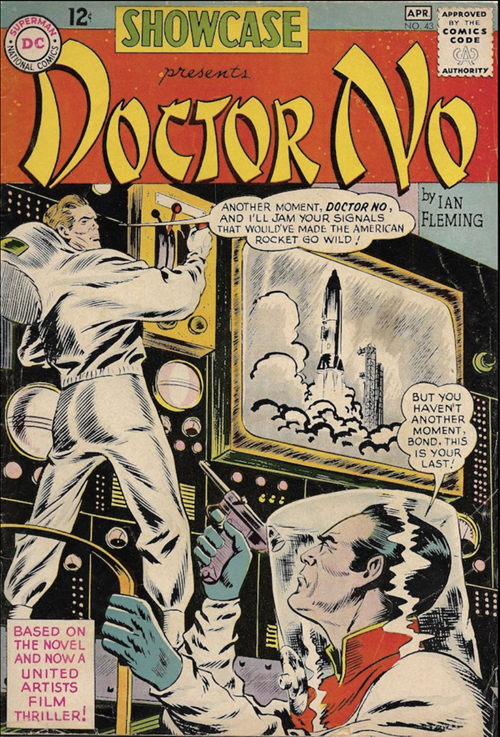

Reports indicate that Amazon MGM was intrigued by the possibility of a James Bond Universe akin to Disney’s Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars Universe. The concept is not a foreign one to Bond producers. Between 1961 and 2002, EON worked with partners in numerous popular media to spread the Bond story throughout the market. They licensed publishers DC, Dell, Marvel, and Topps comics to adapt their films into comic books, such as the 1962 DC Showcase 32-page comic book adaptation of the film Dr. No.

In the 1960s, they showed interest in a children’s TV series based on the 1967 novel The Adventures of James Bond Junior 003 ½ , published by Ian Fleming publisher Jonathan Cape. The concept came to fruition with the syndicated show James Bond Jr. (1991-1992).

In the early 2000s, they started development on a spinoff film titled “Jinx,” based on the Halle Barry character from the 2002 film Die Another Day. And for decades, EON has worked with video game designers to create interactive adventures, the most famous being GoldenEye 007 (1997) for the Nintendo 64 system. In fact, there’s a new EON-licensed game in the works.

In recent years, EON has devoted most of its resources to the films, whose productions became more ambitious. Perhaps sensing Bond’s uniqueness in the market, where franchises saturate consumers with content—Marvel and Alien movies and streaming series, Star Trek shows, Star Wars games, Avatar comics, etc.—EON opted for a more restrained approach that focused on films, creating the impression that they were “specials” and avoiding product overexposure. There have been exceptions. When the Daniel Craig era came to an end with 2021’s No Time to Die, EON signed with Amazon Prime—prior to the Amazon’s acquisition of MGM—to partner on the reality show 007’s Road to a Million. The series required little creative investment on Wilson’s and Broccoli’s part, and Bond doesn’t appear in the show, protecting EON’s most valuable commodity.

Amazon MGM’s notion of a cross-media Bond Universe simply didn’t appeal to EON, and the development of a series to follow the Craig films stalled. Exacerbating the situation, reports are that EON was flummoxed about how to relaunch the films after the creative and financial triumphs of the Craig era.

Why did EON step away?

Commentators have alleged that these creative impasses placed pressure on Wilson and Broccoli to sell their creative stake in the film series. But other developments suggest that the picture is more complicated.

Media franchises like Bond, the Lord of the Rings, Oz, and Marvel are all about rights. In recent weeks, peculiar news has surfaced in The Guardian (UK) about an Austrian-born developer named Josef Kleindienst, owner of a luxury property empire in Dubai, filing a number of “cancellation actions based on non-use” in UK and European courts. His ambition is to claim ownership of a broad swathe of Bond trademarks. These trademarks—for such items as computer programs, electronic comic books, electronic publishing and design—have not been used for a period of five years. Kleindienst is alleging that Danjaq’s trademarks for “James Bond Special Agent 007,” “James Bond 007,” “James Bond,” “James Bond: World of Espionage,” and the expression “Bond, James Bond” are subject to challenge.

These legal challenges, assuming they have standing, would have placed EON/Danjaq in the difficult position of having to battle a well-resourced foe in court or to quickly roll out product to renew their trademarks. A loss of even some of these trademarks could be devastating for the franchise. Acquiring the trademarks would not be easy, but were Kleindienst to succeed, he could at least in theory challenge or seek compensation from the production and release of any product seeking to use the James Bond name. Perhaps Wilson and Broccoli elected to sell their controlling stakes in Bond to avoid a protracted legal battle. Perhaps, too, the multi-billion-dollar firm Amazon MGM stepped in, and agreed as part of the deal to fight these impending trademark challenges to keep all Bond rights under the EON-MGM tent.

If such speculation has merit, then Wilson and Broccoli ceded creative control because it was their only major bargaining chip with Amazon MGM. The deal would ensure their continued roles as stewards of their portion of the Bond rights. After all, even EON/Danjaq doesn’t own all of the Bond intellectual property. The literary, audio, and comics rights are retained by the Ian Fleming Estate and managed by the firm of Ian Fleming Publications (IFP). In a statement issued on its website, IFP addressed the Amazon MGM deal, acknowledging Wilson and Broccoli “for their remarkable stewardship and vision. Their imagining of James Bond on screen has created one of the world’s great film franchises and has led the incredible success of the British film industry.”

What lies ahead for 007?

Here too there’s much speculation. Most fans of the film series seem skeptical about the new Amazon MGM era, concerned that Bond will become just another media franchise. An Ellis Rosen New Yorker cartoon captures the general mood, showing Jeff Bezos—in the guise of Bond villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld—standing over a bound James Bond who lays prone under the Amazon Swoosh symbol in a position reminiscent of the famous laser-torture sequence from 1964’s Goldfinger. In the original, Sean Connery’s Bond says to rival Auric Goldfinger, “You expect me talk?” Goldfinger’s answer is iconic—“No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!” In the New Yorker version, Bezos responds, “No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to star in a series of increasingly bland spinoffs and TV shows that have significant viewership decline after the first episode.”

One thing’s for certain: Bond has entered the “content” era. The film franchise will no longer focus on films alone. Given its extraordinary resources, Amazon MGM may even make a bid for all Bond rights, including a buyout of IFP, bringing the Bond property under one rights-holding company for the first time since the 1950s.

In the meantime, will Amazon MGM respect the Bond film property? Will it treat the replacement of Craig with the same care EON addressed the “new Bond” question in the past? Will it pursue EON’s commitment since the onset of the Craig era to “quality” blockbuster production, with an emphasis on location shooting, practical effects, and adherence to the spirit, if not the letter, of the Fleming version of the character? I have reasons to doubt some of this.

Among other concerns, the copyrights to Ian Fleming’s original Bond stories expire in the UK in 2034, a date that marks 70th anniversary of the author’s death (Fleming’s works are already in the public domain in Canada.)

Amazon MGM has just under a decade to exploit the Bond film rights before competitors are legally able to launch their own adaptations of Fleming’s 007. We can expect more studio-bound, computer-generated (CG) productions, which is more efficient than the location-based approach of EON and today drives most major franchise filmmaking. We can also expect streaming series: a Felix Leiter series, a Moneypenny series, or perhaps a Lashana Lynch 007 series or a Jinx series. Perhaps we can expect Amazon MGM to option a number of the “Bond Continuation” novels released by IFP since Ian Fleming’s death in 1964. Most assuredly, we can expect a “mothership” theatrical series with a new Bond, and even a revival of the James Bond Jr. animated series, for which some fans are nostalgic. Amazon MGM will do many of the things EON/Danjaq did or had hoped to do in the past but didn’t have the resources or bandwidth to do in recent decades.

We can expect, in short, what we’ve come to expect, over and over again. A new Bond era.

For more on EON Productions and its reliance on British film subsidies, see pages 41-42 and 55-56 of James Chapman’s Dr. No: The First James Bond Film (New York: Wallflower Press, 2022). See also Charles Drazin, A Bond for Bond: Film Finances and Dr. No (London: Film Finances, Ltd., 2011).

For a detailed account of the original deal between EON and UA/MGM, see chapter eight of Tino Balio’s United Artists, The Company that Changed the Film Industry, Volume 2, 1951-1978 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987).

Colin Burnett is Program Director and Associate Professor in the Film & Media Studies Program at Washington University in St. Louis. He is the author of two books, including one on the major French director Robert Bresson. He has written an article on storytelling in the James Bond film series for the Journal of Narrative Theory and is completing a new book entitled Serial Bonds: The Shape of 007 Stories.

Moana’s roundabout voyage back to the multiplex: A guest post by Nicholas Benson and Zachary Zahos

I dimly remember hearing in late 2020 that the sequel to Moana (2016) was going to be Moana: The Series, streaming on Disney+ rather than a theatrical feature. David and I liked Moana very much, but in those of Covid and non-theater-going, it seemed a minor thing. A series wasn’t appealing, and we could just ignore it. Then about a year ago it was re-announced as a theatrical feature. I just assumed that the powers-that-be had simply decided that what was by that time being called Moana 2 would make more money by being released “Only in theaters,” as the posters inevitably pointed out.

That was true, but there’s much more lurking behind such a decision. Straight to streaming or released to theaters first? has become a puzzling question for studios as they discover that the huge profits they assumed their new streaming services would bring in were not all that huge or maybe not profits at all.

I am delighted to have two experts, Nicholas Benson and Zachary Zahos, who follow the distribution strategies of the film industry, contribute a guest post on how Moana 2’s change from modest Disney+ series to a box-office hit creeping up on the total domestic gross of Wicked reflects major shifts in the industry’s decisions about releasing options.

Nicholas Benson received his Ph.D. in Media and Cultural Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is now an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and Media at SUNY Oneonta. His current work considers the intersection of discourses of storytelling and management within franchise production cultures. Zachary Zahos also received his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is currently serving as Public History Fellow at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Back in September Zach and Matt St. John contributed a entry to this blog, examining a claim that movie lovers had stopped going to theaters.

Thank you, Nick and Zach, for your contribution to our understanding of the current tangled distribution systems of the current industry! Over to you.

The curse has been lifted—at Walt Disney Pictures.

After a run of box-office bombs, Disney’s flagship film studios bounced back in 2024: Pixar with Inside Out 2, 2024’s top-grossing film, and Walt Disney Animation Studios with Moana 2, which just cleared $1 billion globally. Even Mufasa: The Lion King, a CGI prequel produced by Disney’s live-action division, looks destined to overcome a weak start to become a profitable “sleeper hit.”

The cynical read on all this is that Disney, to quote The Town’s Matt Belloni, “engineered” a surefire 2024 by pushing riskier bets, such as Pixar’s Elio and the Snow White remake, to this calendar year. But, at the end of the day, adaptive engineering, risk mitigation, studio chicanery, whatever you call it—this is how Hollywood lives to tell another tale, and you need not look further than Moana 2 for a revealing case of Disney executives reading the horizon and changing course.

Moana 2’s present status, as a resounding theatrical success, interests us in particular due to the roundabout journey—and P.R. spin—it took to get here. For those unaware, the film now playing in multiplexes called Moana 2 was greenlit in 2020 as a television series (titled Moana: The Series) for the company’s streaming platform Disney+. It was only last February when CEO Bob Iger announced that this project was instead heading to theaters under the new title Moana 2. While the trades were quick to discuss the financial calculus behind such a shift (per Deadline: “after misfires … more Moana is a safe bet for the House of Mouse”), Disney has been careful to publicly attribute this decision to creative, rather than business-minded, imperatives. For instance, Jennifer Lee, former CCO at Disney Animation, told Entertainment Weekly in September:

We constantly screen [our projects], even in drawing [phase] with sketches. It was getting bigger and bigger and more epic, and we really wanted to see it on the big screen. It creatively evolved, and it felt like an organic thing.

As genuine as this sentiment might be, we sincerely doubt that Moana 2’s last-minute about-face, from streaming series to theatrical film, emerged from creative disagreements alone. The film industry has changed rapidly over the last five years—streaming has undergone its own boom and bust cycle during this time, with vintage concepts like advertising, bundling, and return-on-investment, bringing Hollywood executives down to earth. In short, the Walt Disney Company that announced Moana: The Series in 2020 is different from the one that released Moana 2 in theaters last month.

Longtime readers will recall this blog’s fondness for the first film, as shared by David, Kristin, and Jeff Smith. We count ourselves Moana fans, as well, while also agreeing with critical consensus that Moana 2 lacks the inspiration (or songs) of the original.

But what follows is not a review. While we will make reference to certain storytelling choices present in the film, our main goal here is to argue that Moana 2—or, more specifically, the production and circulation context surrounding it—is symptomatic of a global industry in flux. As the world’s largest legacy entertainment company, Disney is not one to buck trends but rather to reinforce them. An engaged analysis of Disney’s recent executive-level decisions offers us a chance to gauge which way the winds of commerce are blowing.

Yet the company’s sheer scope, both internally and across its multi-generational audiences, invariably creates sites of tension and contest. We see that in Jennifer Lee’s public assurances concerning Disney’s creative community, and not its C-suite, steered Moana 2 into theaters. But we also see such tension and contest in how Moana 2’s production history throws long-standing hierarchies at the Walt Disney Company into relief. As a result of Disney+ and recent executive initiatives which we will delve into here, the line separating the company’s film and television output has become increasingly blurred, as have the rules for successfully exploiting marquee franchises, particularly those geared toward younger audiences.

What is clear to us is that, even in success, Disney+ has failed to solve all of its parent company’s problems and in the process has created several new ones. This is not simply because of profit margins, but also because such investments, from both studio and audience, run downstream from discursive categories like “film,” “television,” and “streaming.”

In the case of Moana 2, the shift of Disney’s prized sequel from the “streaming television” to the “theatrical film” column, months out from release, occurred in large part due to the promise of greater financial returns. That much seems obvious, no matter what Jennifer Lee and other creative executives say, given how most studios across the industry have learned to love movie theaters again.

But we do not wish to suggest these leaders are lying through their teeth, either. As strategic as Lee’s statement to Entertainment Weekly may have been, she does seem to genuinely represent the values and norms of the world’s most famous animated film studio. Where else but movie theaters do you go when you design your expensive franchise sequel to be “bigger and more epic”? So, while Moana 2 sailed back to multiplexes amidst an industry-wide correction away from pyrrhic victories in streaming, its journey looks especially inevitable if you account for the particular industrial apparatus from which the film came.

We’ll expand on these ideas by teasing out a few historical threads relevant to Moana 2’s production. These concern Disney+, Disney Animation Studios, and the Walt Disney Company, as well as the latter’s general playbook toward franchising animated entertainment.

Disney+ and the business of animation today

Disney’s recent theatrical rebound is notable given the obstacles—some of them industry-wide, others self-inflicted—its film division has faced since its peak in 2019. That year, Walt Disney Studios reported $11.1 billion in worldwide theatrical revenue, with a record seven films (among them the animated sequels Toy Story 4 and Frozen II) each surpassing $1 billion at the global box office. In November of 2019, the company launched its Disney+ streaming platform. While it always seemed destined to succeed, Disney+ exploded in growth months later as the COVID pandemic closed theaters and Disney’s theme parks.

Since that high-water mark, Disney’s films have struggled, partially due to counterproductive distribution decisions and a streaming-focused production pipeline. On the distribution side, during the pandemic then-CEO Bob Chapek (above) launched Disney+’s day-and-date “Premier Access” program and arranged for Pixar’s latest films, beginning with Soul (2020), to skip theaters and instead premiere on the streaming platform. While this strategy fueled subscriber growth, almost every animated film Disney released to theaters in its wake, most notably Lightyear (2022) and Strange World (2022), underperformed at the box office. Analysts have attributed this cold streak to a range of causes, including the notion that Disney’s streaming release strategy had “conditioned audiences” to wait for theatrical releases to hit streaming.

Much ink has already been spilled on another contributing pop psychology phenomenon, that of “franchise fatigue.” The idea that audiences are burned out by the proliferation and interconnectedness of so much franchise material may not be neatly supported by the data. The top 10 movies of 2024 were all franchise properties, after all. It is a more credible notion if one examines Disney’s many spin-offs on streaming. Since 2019, the company’s marquee film production companies, among them LucasFilm and Marvel Studios, have shifted resources to producing long-form television series for Disney+. LucasFilm and Marvel respectively launched their Disney+ slates with The Mandalorian and WandaVision, both of which were well received and highly rated. But ever since, Disney’s streaming series have attracted increasingly mixed critical responses (even after controlling for toxic fan reactions) and diminishing viewership numbers (here and here).

That does not mean all Disney+ originals are destined for failure. What seems increasingly clear is that certain forms of programming, such as animation, perform more consistently, albeit under a typically lower ceiling of viewership. In October, The Hollywood Reporter published a 3000+ word article headlined, “Is Disney Bad at Star Wars? An Analysis.” To be clear, the piece answers its core question with, “On balance, no.” Nevertheless, this article is relevant to this discussion in that it contrasts the strong ratings of the Star Wars animated series on Disney+ with the franchise’s live-action series for the same platform. New animated series like The Bad Batch have more than earned their keep, with their large volume of episodes (usually 16 per season vs. 8 for live-action series) driving viewer engagement at a fraction of the cost of their recent live-action counterparts.

So, Disney+ is a sensible launching pad for new animated Star Wars series. Does that make it also wise to premiere the latest Disney Princess tale on the same platform? (Despite Moana 2’s “Still not a princess!” joke, in the eyes of Disney, she officially is one, as the Princesses scene in Ralph Breaks the Internet, below, demonstrates.) Well, that depends.

Traditionally, Disney has had three main paths for exploiting animated franchise content: theatrical distribution, commercial television, and direct-to-video (DTV). Each of these had clear advantages and disadvantages, and for many years these three paths looked fairly straightforward. Theatrical distribution, both then and now, is prestigious and visible to a large, diverse audience, and it comes with the potential for massive global box office revenues and merchandising opportunities which can immediately counteract the large budget.

The other two categories—commercial television and DTV—were lucrative paths for many years at the Walt Disney Company, but under the Disney+ paradigm have begun to appear less distinct from the theatrical option. Commercial television traditionally came with less expectation that it feel cinematic, and therefore could be made on a smaller budget. Television series promise a smaller, more concentrated audience of children or existing fans and a long tail financial model that relies on revenue generated through ad support and future syndication possibilities. DTV content, for its part, follows a similar model to commercial television but at an even lower scale of cost, with accordingly lower (but faster) profit potential.

The visibility of commercial television content within the Disney animated fold is moderate (and outright low for DTV). Millions of children apparently watched the Tangled (2010) spin-off Rapunzel’s Tangled Adventures, which was produced by Disney Television Animation and aired from 2017 to 2020 on the Disney Channel. We don’t expect you, reader, to have heard of this show, though at the same time we would be surprised if you never before heard of Tangled. Thus, even resounding successes of this type will remain off the radar of the general, adult-aged public, and so commercial television spin-offs, even if not the highest quality, will not inherently hurt the brand as a large film can.

It’s on this last point, regarding visibility, where the project formerly known as Moana: The Series was always destined to be different. With the company’s flagship studio, Disney Animation Studios, producing it, the budget leaped beyond any animated project Disney produced before for television or DTV. Launching Moana: The Series exclusively on Disney+ had potential upside, but as we will see, these benefits began to look questionable.

Moana’s voyage toward streaming…

Moana: The Series was first announced, by Jennifer Lee, at the virtual Disney Investor Day event in December 2020. The broader theme of the investor’s day was Disney’s new structure, which separated content creation from distribution in a bid to turn to what newly appointed CEO Bob Chapek referred to as a “DTC [direct-to-consumer] first business model.” The Moana series thus joined a slate of other Disney+ releases, including day-and-date release movies like Raya and the Last Dragon (2021), Marvel series such as Loki (2021-2023), and limited series such as WandaVision (2021). Though executives continued to gesture towards the importance of “legacy distribution platforms,” such as theatrical and linear television, the focus was on the corporation’s investment in Disney+. As Chapek put it in his opening statement:

We knew this one-of-a-kind service featuring content only Disney can create would resonate with consumers and stand out in the marketplace and needless to say Disney+ has exceeded our wildest expectations.

The idea to expand the Moana franchise into a series, therefore, was a direct result of corporate confidence in DTC platforms as the future of distribution. Chapek’s new corporate structure promised a streamlined production pipeline that seemed to completely separate the creation and production process from the distribution process — in other words, creatives would generate content and then the distribution team would figure out the best way to get that content to the consumer. Chapek explained the structure in a statement:

Managing content creation distinct from distribution will allow us to be more effective and nimble in making the content consumers want most, delivered in the way they prefer to consume it. Our creative teams will concentrate on what they do best—making world-class, franchise-based content—while our newly centralized global distribution team will focus on delivering and monetizing that content in the most optimal way across all platforms, including Disney+, Hulu, ESPN+ and the coming Star international streaming service.

This new agnostic approach to distribution seemed to lead to a general confusion about how to staff DTC productions. The Moana follow-up presented a mixed bag in terms of who was brought back from the original production. Voice talent Dayne Johnson and Auliʻi Cravalho respectively reprised their roles as Maui and Moana. However, original Moana directors Ron Clements and John Musker were absent. Instead, Jason Hand, Dana Ledoux Miller and David G. Derrick Jr. (above) were hired to co-direct and run the series. Hand, who had the most experience working with Disney animation of the three, started his career at Disney in 2005, as a layout artist on the DTV sequels Tarzan 2: The Legend Begins and Lilo & Stitch 2: Stitch Has a Glitch. Disney has a well-known apprenticeship program and tends to hire and promote from within, so it’s not out of the ordinary that a series like this would be given to greener talent looking to gain experience.

That said, Moana: The Series’s production team was indicative of a broader ambivalence the company seemed to have about how much to invest in, and therefore how to staff, DTC content. While the series Baymax! (2022) brought in Big Hero 6 (2014) director Don Hall as showrunner, other series like Zootopia+ (2022) and the upcoming Tiana (2025) did not bring back the same directing or writing teams from the original films. Instead, Zootopia+ was directed by Trent Correy and Josie Trinidad, who previously worked in the Animation and Story departments on Zootopia, respectively. Tiana is reportedly being run by Joyce Sherri, who served as staff writer for the Netflix miniseries Midnight Mass (2021).

…and back to the multiplex

News on the Moana series remained sparse from 2020 until February 2024, when Bob Iger announced during a CNBC interview that the series would now be a theatrical feature slated for a fall 2024 release. The news came shortly before a Q1 earning call where he assured shareholders that “the stage is now set for significant growth and success, including ample opportunity to increase shareholder returns as our earnings and free cash flow continue to grow.”

Iger’s assurance came on the heels of a tumultuous few years for Disney, after a series of box-office failures and an internal struggle for power that resulted in the ousting of CEO Bob Chapek and a return to the post for Iger. While the issues faced by Disney were multifaceted, the all-in approach to DTC content was central to the company’s financial struggles. Subscriber fees could only generate so much revenue, and that revenue didn’t seem enough to sustain the enormous content library required to maintain a streaming platform. In September of 2022, Bob Chapek indicated to Hollywood Reporter that Disney+ had a content problem. As Chapek put it:

It’s important to go back to when Disney+ was launched and what the hypothesis was about how much food you had to give that system for it to truly maximize its potential, and I would say we dramatically underestimated the hungry beast and how much content it needed to be fed.

The extent of this issue became apparent during a 2023 lawsuit against Disney by investors alleging Disney hid the actual costs of running the service to offer the appearance of profit potential. Though the service is reportedly now profitable, since its inception Disney+ has racked up over 11 billion dollars in losses, showing that the DTC, subscription-based model has not been the massive success it was predicted to be in 2020.

In late 2024, as the premiere for the re-titled Moana 2 approached, those who worked on it related to press outlets various versions of how the series abruptly shifted to a theatrical film. We can return to that September Entertainment Weekly profile to see a few explanations side-by-side. For instance, co-director David G. Derrick Jr. described the decision to pivot from a series to a feature film as a moment of “mutual realization” between the studio’s various teams:

It became apparent very early on that this wanted to be on the big screen. It felt like a groundswell within the whole studio.

Co-director Dana Ledoux Miller framed it as a push from the creatives, out of a desire to showcase their work. She suggested the project had “the best artists in the world” and added:

Why are we not letting them shine on the biggest screen in the biggest way?

This rhetoric stood in sharp contrast to Chapek’s 2020 Investor Day video, in which he seemed to downplay the importance of theatrical distribution in favor of the convenience of DTC exhibition. At that point, there was no sense that artists would feel minimized by having their work showcased on DTC platforms. Instead, these new comments by the creative team touted theatrical exhibition as a prestigious honor and the only way to showcase quality artistic achievement.

In other words, after years of the studio relegating several projects to Disney+ or day-and-date releases, Moana 2’s pivot feels like a pointed reinvestment in the theatrical experience. Jennifer Lee reinforced this perspective when she said to Entertainment Weekly:

Supporting the theaters is something that we talked about. … We love Disney+, but it will go there eventually. You could really put it anywhere, but these artists create stories that they want to see on the big screen and that we want the world to see on the big screen.

When the show was reworked as a movie, the absence of certain high-profile talent associated with the first Moana—especially popular songwriter Lin-Manual Miranda—became apparent. The official reason for Miranda’s absence was that he was already committed to another Disney theatrical project, Mufasa: The Lion King (2024). While Moana composers Mark Mancina and Opetaia Foa’i did return to score the movie, the new songs for the sequel were primarily composed by Abigail Barlow and Emily Bear. The two were, as Billboard put it, “the youngest (and only all-women) songwriting duo to create a full soundtrack for a Disney animated film.” Until that point their only real credit was writing an unsanctioned viral musical based on the Netflix show Bridgerton (2020 – ). Though having young women write the music for a musical about young women was a positive move for Disney, the pair’s relative inexperience became more conspicuous when the Disney+ show was transformed into a tentpole feature film. In its review of the film, The Hollywood Reporter noted that “Miranda’s absence is unfortunately felt” throughout the musical numbers. Variety, more pointedly, called the new batch of songs, “imitation-Lin-Manual knockoffs.”

The lack of personnel continuity between Moana and Moana 2 highlights the general disorganization within Disney’s new corporate structure. Despite the claim that content can be created and then distributed wherever by reading the will of the data gods, the reality is projects still seem to work best when the venue of the exhibition is known during the early stages of production. When Disney has done theatrical sequels they tend to staff them with creative talent from the original. Jennifer Lee oversaw the creation of Frozen 2 (2019), Andrew Stanton returned for Finding Dory (2016), and Pete Doctor directed Inside Out 2 (2024). Though Miranda claims he was otherwise preoccupied, one wonders if he would have still worked on Mufasa: The Lion King had he known the Moana follow-up was destined for a theatrical release.

While this is primarily an industry analysis, even a cursory look at Moana 2’s narrative reveals the editorial marks left by this unusual production. As with the first film, the sequel tasks Moana with breaking an ancient curse, except this one was set by a storm god named Nalo, who drove the different peoples of Polynesia apart. With this clear objective, Moana remains a classical, goal-oriented protagonist, but the seams begin to show once you look at the other characters. Curiously, Nalo remains an off-screen antagonist, who is not properly introduced until a mid-credits scene that mimics Thanos’s first appearance in The Avengers (2011). The journey is also now populated by a group of secondary characters easily identified by a defining trait (e.g., Moni is a huge Maui fanboy). The first act, set on Moana’s well-populated island of Motunui, feels especially abridged from the project’s looser, episodic origins, and the onslaught of new characters leaves little room for the emotional depth and character development that many critics respect about the first film (here and here).

The seams where Moana: The Series was stitched together into Moana 2 are not only evident in the story, but in the production and promotion as well. Being forced into the throes of a giant A-list press junket was probably not what these first time directors signed up for; it’s certainly something the team behind the direct-to-video Cinderella II: Dreams Come True (2002) never had to deal with, and for good reason.

Yet Moana 2’s directors were left answering questions about decisions made in the first movie they had little or no control over. For example, the cute pig Pua, whom fans felt was underused in the original movie, took on a more prominent role in the sequel. When asked by CinemaBlend if they responded to any feedback about the first film, director/writer Dana Ledoux Miller responded:

Look, people really wanted Pua in that first movie on the canoe. I wasn’t around, but we put Pua on the canoe now.

While not overly awkward, the exchange highlights the behind-the-scenes break in continuity. Similarly, young songwriters who should be establishing their own identity were instead having their work compared to the beloved music of Lin-Manuel Miranda. Ultimately, while this has financially paid off for Disney, Moana 2 was clearly a ship built for the smaller more secluded waters of Disney+. Though it has survived, the tepid reviews suggest it may have been only by the skin of its teeth.

Riding the popcorn-bucket wave

Moana 2 is not only indicative of the pitfalls of the DTC model but highlights the inherent potential of theatrical distribution, especially for franchised content. Despite lukewarm reviews, the movie has already earned record numbers at the box office. More importantly, it has reignited interest in the brand more broadly. Moana became the latest entry in a list of high-profile collectors’ popcorn buckets distributed by theaters (above).

While they might seem like a gimmick, these popcorn buckets have become an integral aspect of the theatrical distribution model and the “post-pandemic ‘identification’ of moviegoing.” They  work in favor of both the theaters and the studios by raising awareness about the films and the brand. As one journalist pointed out, “I didn’t realize Despicable Me 4 was happening until I saw the popcorn bucket.” With the release of toy lines (Funko dolls aplenty, including Pua, above and left), popcorn buckets (and nacho boats!), and theme park tie-ins, the hype machine that spins around a massive theatrical release has become somewhat intuitive over the past century in a way that DTC models have difficulty emulating, even with the benefit of synergy within vertically integrated corporate structures.

work in favor of both the theaters and the studios by raising awareness about the films and the brand. As one journalist pointed out, “I didn’t realize Despicable Me 4 was happening until I saw the popcorn bucket.” With the release of toy lines (Funko dolls aplenty, including Pua, above and left), popcorn buckets (and nacho boats!), and theme park tie-ins, the hype machine that spins around a massive theatrical release has become somewhat intuitive over the past century in a way that DTC models have difficulty emulating, even with the benefit of synergy within vertically integrated corporate structures.

Though box-office numbers are important, this hype is equally valuable. In this way, Moana 2 was a success even before it debuted. The trailer for Moana 2 broke the record for the most-watched trailer for a Disney movie ever, reaching over 178 million views in 24 hours. Likely not coincidentally, that trailer ended with an image of Maui holding Pua, announcing that this cute character was, as Miller had put it, “on the canoe” and (more importantly) ripe for new licensing deals. When Moana 2 was announced to be a movie, it kicked off one of the largest and most lucrative global merchandising campaigns in recent memory. Apart from Moana merchandise, there were brand partnerships with airlines to local Hawaiian food chains. Imagery flooded public spaces. Hasbro introduced cutting-edge 3D printing technology to inject toys and dolls as quickly as possible into the marketplace. This success, both in theaters and retail, suggests that even if somewhat clunky, the 11th-hour decision to turn a television show into a movie seems to have been financially prudent – at least in this instance.

New rules, some of them old

During Disney’s 2024 Q4 earnings call, Bob Iger admitted, seemingly unintentionally, the motivation for recent subscription price increases for Disney+. According to Iger, these streaming price hikes were designed less to generate revenue through subscriber fees and more to shift consumers to the ad-supported model:

It’s not just about raising pricing, it’s about moving consumers to the advertiser-supported side of the streaming platform. … The pricing that we recently put into place, which is increased pricing, was actually designed to move more people in the AVOD [advertising video-on-demand] direction because we know that the ARPU [average revenue per user] — and interest in it from advertisers in streaming — has grown.

Iger’s comments point to how these companies are starting to recognize (or grapple with) where the actual value of the streaming service lies within the broader corporate structure: specifically, how the streaming service functions, or serves, the vast media franchises these companies have restructured around. Until recently, executives imagined them as vertically integrated platforms that allowed corporations to get content directly to consumers without the need for middlemen (though, with the exception of Comcast, third-party telecom companies still control the actual distribution pipeline, complicating the notion that these are truly vertically integrated systems). As this system evolves to support ads, content will need to be capable of sustaining viewers over time and selling ad space to sponsors. In other words, despite all the obfuscation of what will likely amount to a transition period, streaming services seem destined to be mostly a different distribution platform for what had been commonly known for the past century simply as commercial television.

Despite some disruptions over the past several years, theatrical distribution continues to hold a privileged position in the cultural zeitgeist, especially for high-profile properties. Movies can air on TV, but the experience of watching them is still culturally different from that of watching something in a movie in the theater. The act of going to the movies is an event apart from one’s day-to-day life (one must schedule a movie, what David called “appointment viewing”), while television, regardless of its distribution mechanism, remains intertwined with the cadence of one’s daily routine.

Take, for example, a recent review of Mufasa: The Lion King (2024) in Polygon. Writer Petrana Raduloviv opines that the movie would have fared better as a video-on-demand release:

Mufasa: The Lion King, the 2024 movie about Simba’s majestic father, seems like it could exist right alongside Simba’s Pride, The Lion King 1 ½, and the animated TV show The Lion Guard. Except instead of being cheaply thrown together for young audiences, it was directed by Academy Award winner Barry Jenkins (Moonlight, The Underground Railroad), with a script from Catch Me If You Can screenwriter Jeff Nathanson, and music from Lin-Manuel Miranda.

In other words, the string of Lion King sequels might lead people to think that this latest one could be treated like the previous ones, being presented DTV. The celebrity talent involved, however, kindled enough interest to lure audiences into theaters and make Mufasa a hit.

Despite claims to the contrary, lines between various exhibition sites remain strong. DTV content and theatrical releases are seemingly different cultural categories that, in turn, invite different reading strategies. As the above quote suggests, success is, in part, based on expectations, and expectations tend to be tied directly to the site of the exhibition. As media conglomerates consolidate and organize transmedia franchises, they must negotiate the utility and corporate value of each exhibition site at their disposal. The task for media producers over the next few years is to calculate the financial value of these cultural categories and use that to calibrate the production costs of their various franchise proliferations. In short, this difference in cultural capital between these two exhibition sites constitutes a difference in industrial strategy as corporations seek to exploit and profit from their various properties in myriad ways. How this shakes out will have lasting effects on the future of film and television creation for decades.

Studios are grappling with these questions of medium-specificity, appropriate exhibition, and franchise management in real-time. New rules are being forged that will shape the future of distribution. As we see it, streaming is unlikely to collapse theatrical and television into a single system but instead offer a hybrid exhibition site that seems to fill the role of both commercial television and the direct-to-video market.

What complicates streaming currently is that it has traditionally been subscriber-supported and therefore followed a premium cable, rather than a commercial television, model of production (see Amanda D. Lotz for more on this distinction). Unlike the commercial television or direct-to-video route, where the value for those exhibition options was tied to their lower production costs, streaming tends to demand a similar quality production to film since it’s not really competing with broadcast television. Instead its rival is seemingly premium cable programming like Game of Thrones. Therefore, it’s very expensive, sometimes more expensive than film production.

Streaming tends to look for a larger audience and is not aimed at exploiting as much as expanding a story world as a franchise. This strategy may be something that fans of that particular story world want, but a general audience would rather watch individual stories than dive into an elaborate franchise saga. Streaming shows also tend not to consistently generate the same cultural impact as a theatrical release (is anyone talking about The Skeleton Crew?). In other words, as it exists, streaming offers the worst of all worlds for media conglomerates looking to exploit their intellectual properties in ways that generate revenue and help the brand. Shows are expensive to produce, they can generate bad press and harm the brand, but they have very little potential to generate large revenues.

We would argue that this is likely why Moana: The Series was reworked into Moana 2 and prepared for a theatrical run. Though the budget has not been officially revealed, based on industry sources, the budget was likely close to the $150 million budget of the first movie. In other words, it’s not because the story got “too big,” but because the budget was too big to justify it being tossed into the increasingly large pile of disposable Disney+ content.

Moana 2 is part of a clear trend. In 2023 The Mandalorian’s final season was transitioned from a Disney+ series to the upcoming theatrical release, The Mandalorian and Grogu (2026). Inside Out 2 (2024) enjoyed a successful box office run as a traditional Pixar theatrical release. A few months later, after the movie hit streaming services, the short, animated spin-off series Dream Productions (2024) debuted on Disney+. The four-episode limited series was produced on a severely reduced budget concurrently with the feature film production. However, mid-production Disney cut the episode order from seven to four.

When Moana: The Series was announced in 2020, Disney also announced a Tiana musical series based on the Princess and The Frog (2009). Though it was set to be released in 2023, it’s still in development – perhaps preparing to shift into a feature film. Disney has also systematically canceled or prepared to phase out many of its more expensive shows, even popular ones. Shows such as Ahsoka, Andor, and The Acolyte are all being canceled after one or two seasons. This suggests that Moana 2 did not evolve on a whim, but rather as part of a broader systematic move away from expensive Disney+ series and towards high-profile theatrical content. As Disney builds its advertising infrastructure, we’ll likely see Disney+ pursue things like Young Jedi Adventures (2023): franchise spin-offs aimed at families and children that are relatively cheap to produce and have syndication potential.

Yet Moana 2 also highlights a unique value of streaming over other forms of exhibition: data. Moana (2016) was the most streamed movie of 2023. Because of this, Disney knew that Moana (2016) was popular among their fanbase. This likely gave Iger and others some confidence that even without the A-list creative talent behind the scenes, the property alone could carry a sequel to a box office win, which in turn results in positive press and better stock performance. Similarly, the popularity of The Mandalorian (2019 -) as the second most streamed series on Disney+, behind only The Simpsons, likely factored into the choice to greenlight The Mandalorian and Grogu (2026) for theatrical release. We would likewise guess that the greenlighting of Frozen 3 and Zootopia 2 was likely less about some burning creative need to expand those stories and more about promising Disney+ data.

The decision to release the Moana sequel in theaters also reflects the obvious point that theatrical movies generate a higher profile than DTV series. Once they end their theatrical runs and are offered on streaming services, the desire to see them may lead to new subscribers.

Ultimately, what we see is not the erasure of one form of exhibition in favor of streaming, or competition between theaters, television, and streaming services, but the formation of a nascent symbiosis between these sites, as media conglomerates consider their place within each corporate enterprise.

Our gratitude to Matt St. John for inspiring and improving this piece.

We would also like to thank Kristin for her edits and insights on contemporary animation.

Relevant to this discussion is a newly filed lawsuit suing Disney for copyright infringement over the Moana franchise. Entertainment Weekly broke this news on January 12, and it goes without saying that we will follow this case as it proceeds.

Women, Oscars, and power (a repost)

Kathleen Kennedy on the 1 January 2013 cover.

Kristin here:

David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1000+ entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed. The run-up to the Oscars seemed a good time to revisit this one.

Ever since the Oscar nominations were announced on Tuesday, January 23, social media and mainstream news outlets have been full of posts and articles about the “snubs” of female directors, notably Greta Gerwig and Celine Song. Even Hilary Clinton weighed in with some Barbie-love. Of course the failure to nominate many other people, male and female, also insired similar indignant tirades by fans. How could Alexander Payne be left out when virtually everyone who sees The Holdovers adores it? What about Leonardo DiCaprio? Or Greta Lee? Or fill in the blank?

This sort of kvetching goes on every year, when inevitably a large number of worthies fail to be nominated. This year was perhaps bound to produce more of these also-rans, since as many have pointed out, this year saw an unusual number of excellent films. Christopher Nolan, Wes Anderson, and Alexander Payne released films that are arguably among their best. Aki Kaurismäki, after a gap of six years, returned with the quietly excellent Fallen Leaves. Hayao Miyazaki came out of retirement with The Boy and the Heron. Outside the Oscar nominees, major veteran filmmakers contributed Close Your Eyes (Víctor Erice) and R.M.N. (Cristian Mungui). The list could go on.

Returning to the issue of female directors and actors being snubbed by Academy voters, a few people point out that Margot Robbie is nominated for “Best Picture,” having been one of the producers of Barbie. Emma Stone is in the same position with Poor Things (though she, of course, did get nominated for Best Actress). On the whole, however, being a woman nominated for producing a Best Picture gets little or no attention, even if it is arguably as prestigious, if not more so.

This strange imbalance has gone on for a long time. On October 23, 2017, I posted a blog entry on the topic. It was inspired by a Variety cover story on Kathleen Kennedy (above). I discussed the reasons why female producers are ignored by the public and by journalists. As I say below, that happens partly because there is no “best producer” category, and in the past, the names of the producers who would claim the statuette if their films won, were not listed. I see that this year, the Academy’s website does list all the names of the producers of the Best Picture nominees. Did they read my post? I’ll never know. I note that the suggestion made in my final paragraph has not been followed by the press.

The old post does give a rundown of female producers who were nominated and in some cases won, from the first in 1973 up to 2016, by which point women were commonly being nominated in this category. For 2023, eight of the 30 producers of Best Picture nominees are women.

The original entry

We are now well into the season when award speculation begins. Well, actually Oscar speculation knows no season these days, but it snowballs between now and the announcement of the winners on March 4–at which point the speculation concerning the 2018 Oscar race revs up.

Among the issues that will inevitably come up is the question of whether more women directors will get nominated, especially following the critical and box-office success of Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman. It would be great to see more female nominees for Best Director, but the real problem is achieving more equity in the number of women being able to direct films at all. Unless more women direct more films, their odds of getting nominated will be low. Maybe the occasional Kathryn Bigelow will emerge, but overall the directors making theatrical features remain largely male.

Variety recently ran a story about initiatives to boost women’s chances in Hollywood. It stressed the low percentage of women in various key filmmaking roles:

The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University found that in 2014, women made up just 7% of the directors behind Hollywood’s top 250 films. Overall, of the 700 films the center studied in 2014, 85% had no female directors, 80% had no female writers, 33% had no female producers, 78% had no female editors and 92% had no female cinematographers.

Discouraging, except that there’s one figure that doesn’t support the lack of women. If 33% of films were without female producers, that means 67% had female producers–which is a lot better than in those other categories.

One thing that has struck me as odd is the lack of attention paid to the distinct rise in the number of female producers being up for Oscars in the recent past. This Variety article, however, is the first one I’ve seen offering numbers to show that women are doing a lot better in the producing field than in other major areas.

The missing names

Kathleen Kennedy, the lady illustrated at the top of this entry has produced seven films nominated as Best Picture, and she is considered one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. How could she not be? She produced Steven Spielberg’s films, alongside others, for many years and since October, 2012, she has been President of Lucasfilm in its incarnation as a subsidiary of Disney. She runs the Star Wars series.

In the Indie realm, producer Dede Gardner is on a roll, having since 2011 had three films nominated for the top prize in addition to wins in 2013 and 2016. Others, such as Megan Ellison and Tracey Seaward, have enjoyed multiple nominations. (I’m using the film’s year of release rather than the year when the award was bestowed.) As we’ll see, female producers are beginning to catch up to their male colleagues in number as well as prestige. Why no fuss about such important strides?

I think the main reason is that there’s no “Best Producer” category. If there were, I suspect our image of women in the industry would be very different. But there’s just a Best Picture one. In most cases neither the industry journals nor the infotainment coverage lists the producers alongside the titles of the Best Picture nominees. So who’s to know that the “Best Picture” race also is, faut de mieux, the “Best Producer” contest.

Another, perhaps less important reason why producers draw less attention is that because a film often has several producers. It’s more complicated to assign responsibility for who did what. Most people have a general idea of what directors do. They’re on set, they make decisions, and they supervise other artists. A female producer, like a male one, may have been included for many reasons. She might have done most of the work in assembling the main cast or crew members or she might have concentrated on gaining financial support. She might instead be termed a producer as a reward for crucial support at one juncture. We can’t know, and that perhaps makes it difficult for the public to get enthusiastic about producers. Of course, if journalists covered them more in the entertainment press, the public might gain more of a sense of what producers do.

Yet whatever their contribution, those producers played some sort of crucial role, and they are the ones who get up and receive the statuettes when that last climactic announcement of the evening is made. (Lately there has been a trend for the every member of the cast and crew and all their relatives present to rush onto the stage for a grand finale, but it’s the producers who give the thank-you speeches.) They can take those statuettes, with their names engraved on them, home and put them on their mantels or to their office to display in a glass case. Yet few have any name recognition outside the industry, the entertainment press, and a few academics.

Despite these producers’ importance, it’s difficult to find out who they have been over the years. Go to almost any website, including the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ own, in search of Oscar nominees stretching back through the years, and you will usually find names listed in all the other categories–but only the title of the nominated films in the Best Picture category. I finally found a complete list of Best Picture nominees’ producers compiled by an industrious contributor to Wikipedia. Going through and doing some counting and cross-checking, I have created and annotated my own list. With it I’ve tried to show the fairly steady progress that women have made in this category. I call them “nominees” below. Somewhat paradoxically, they win the Oscars, though technically the film is the official nominee.

To keep this list from becoming even longer, I’ve listed only nominated films which had one or more women among their group of producers. Up to 2008 there were five films each year. Starting in 2009 the number could be anywhere between five and ten, though it’s usually eight or nine. I give the number of nominated films starting in 2009. Assume any films not listed were produced by men. If you’re curious about who those men were, click on the link in the previous paragraph.

Here’s how things developed, including only years when female producers were “nominated.” (My comments in red.) Be patient. It gets off to a slow start, but things pick up.

And the nominees are …

1973 The Sting (WINNER) Tony Bill, Michael Phillips, and Julia Phillips.

Julia Phillips becomes the first female producer nominated since the Oscars began in 1927 and the first to win.

1982 E.T. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

The second female producer nominated.

1984 Places in the Heart. Arlene Donovon.

The third nominated female producer.

1987 Fatal Attraction. Stanley R. Jaffe and Sherry Lansing.

The fourth nominated female producer.

1989 Driving Miss Daisy. (WINNER) Richard D. Zanuck and Lili Fini Zanuck.

Lili Fini Zanuck is the second female producer to win.

1991 The Prince of Tides. Barbra Streisand and Andrew S. Karsch.

1994 Forrest Gump. (WINNER) Wendy Finerman, Steve Tisch, and Steve Starkey.

The Shawshank Redemption. Niki Marvin.

Wendy Finerman (right) becomes the third woman producer to win a Best Picture Oscar.

This is the first year when two women are nominated. From this point to the present, there has been no year without at least one female producer nominated.

1995 Sense and Sensibility. Lindsay Doran.

1996 Shine. Jane Scott.

1997 As Good as It Gets. James L. Brooks, Bridget Johnson, and Kristi Zea.

The first year when four women are nominated.

The first time two women are nominated for the same film.

1998 Shakespeare in Love. (WINNER) David Parfitt, Donna Gigliotti, Harvey Weinstein, Edward Swick, and Marc Norman.

Elizabeth. Alison Owen, Eric Fellner, and Tim Bevan.

Life Is Beautiful. Elda Ferri and Gianluigi Brasch.

Gigliotti is the fourth woman to win a producing Oscar.

1999 The Sixth Sense. Frank Marshall, Kathleen Kennedy, and Barry Mendel.

First year when a woman producer, Kennedy, is nominated for a second time.

2000 Chocolat. David Brown, Kit Golden, and Leslie Holleran.

Erin Brockovich. Danny DeVito, Michael Shamberg, and Stacey Sher.

For the second time, two women are nominated for the same film.

2001 The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2002 The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2003 The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. (WINNER) Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

Lost in Translation. Ross Katz and Sofia Coppola.

Mystic River. Robert Lorenz, Judie G. Hoyt, and Clint Eastwood.

Seabiscuit. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Gary Ross.

Walsh is the fifth woman to win in this category.

Walsh and Kennedy tie for the first woman nominated three times.

The second year when four women are nominated.

2004 Finding Neverland. Richard N. Gladstein and Nellie Bellflower.

2005 Crash. (WINNER) Paul Haggis and Cathy Schulman.

Brokeback Mountain. Diana Ossance and James Schamus.

Capote. Caroline Baron, William Vince, and Michael Ohoven.

Munich. Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy, and Michael Mendel.

Cathy Schulman is the sixth woman to win.

The third time four women are nominated.

Kennedy becomes the first woman nominated four times.

2006 The Queen. Andy Harris, Christine Langan, and Tracey Seaward.

2007 Michael Clayton. Jennifer Fox and Sydney Pollack.

Juno. Lianne Halfon, Mason Novack, and Russell Smith.

There Will Be Blood. Paul Thomas Anderson, Daniel Lopi, and JoAnne Sellar.

The first year in which five women are nominated in this category.

2008 The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Céan Chaffin.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

First time a woman, Kennedy, reaches a fifth nomination.

The third time two women are nominated for the same film.

2009 The first year of up to ten nominations. Ten films nominated.

The Hurt Locker. (WINNER) Kathryn Bigelow, Mark Boal, Nicholas Chartier, and Greg Shapiro.

District 9. Peter Jackson and Carolynne Cunningham.

An Education. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

Precious. Lee Daniels, Sarah Siegel-Magness, and Gary Magness.

Kathryn Bigelow becomes the seventh woman to win in this category. (Right, with her producing and directing Oscars.)

The fourth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2010 Ten films nominated.

Inception. Christopher Noland and Emma Thomas.

The Kids Are All Right. Gary Gilbert, Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, and Celine Rattray.

The Social Network. Pana Brunetti, Céan Chaffin, Michael De Luca, and Scott Rudin.

Toy Story 3. Darla K. Anderson.

Winter’s Bone. Alex Madigan and Ann Rossellini.

The second year five women are nominated in this category.

2011 Nine films nominated.

Midnight in Paris. Letty Aronson and Stephen Tenebaum.

Moneyball. Michael De Luca, Rachael Horovitz, and Brad Pitt.

The Tree of Life. Sarah Green, Bill Pohlad, Dede Gardner, and Grant Hill.

War Horse. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Kennedy receives her sixth nomination.

The third year in which five women are nominated in this category.

The fifth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2012 Nine films nominated.

Amour. Margaret Mengoz, Stefan Arndt, Veit Heiduschka, and Michael Katz.

Django Unchained. Stacey Sher, Reginald Hudlin, and Pilar Savone.

Les Misérables. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Debra Hayward, and Cameron Mackintosh.

Lincoln. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Silver Linings Playbook. Donna Gigliotti, Bruce Cohen, and Jonathan Gordon.

Zero Dark Thirty. Mark Boal, Kathryn Bigelow, and Megan Ellison.

Eight female producers nominated, besting the previous record by three.

The first year in which each of two nominated films has two female producers.

Kennedy receives her seventh nomination.

2013 Nine films nominated.

12 Years a Slave. (WINNER) Brad Pitt, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Klein, Steve McQueen, and Anthony Katugas.

American Hustle. Charles Roven, Richard Suckle, Megan Ellison, and Jonathan Gordan.

Dallas Buyers Club. Robbie Brennert and Rachel Winter.

Her. Megan Ellison, Spike Jonze, and Vincent Landay.

Philomena. Gabrielle Tana, Steve Coogan, and Tracey Seaward.

The Wolf of Wall Street. Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, Joey McFarland, and Emma Tillinger Koskoff.

Dede Gardner becomes the eighth woman to win an Oscar in this category.

Megan Ellison becomes the first woman nominated for two films in the same year.

2014 Eight films nominated.

Boyhood. Richard Linklater and Cathleen Sutherland.

The Imitation Game. Nora Grossman, Ido Wostrowskya, and Teddy Scharzman.

Selma. Christian Colson, Oprah Winfrey, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

The Theory of Everything. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Lisa Bruce, and Anthony McCarten.

Whiplash. Jason Blum, Helen Estabrook, and David Lancaster.

2015 Eight films nominated.

Spotlight. (WINNER) Blye Pagon Faust, Steve Golin, Nicole Roaklin, and Michael Sugar.

The Big Short. Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, and Brad Pitt.

Bridge of Spies. Steven Spielberg, Marc Platt, and Kristie Macosko Krieger.

Brooklyn. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

The Revenant. Arnon Milchan, Steve Golin, Alejandro G. Iñárittu, Mary Parent, and Keith Redmon.

Blye Pagon Faust and Nicole Roaklin become the ninth and tenth winners.

For the first time two women win for the same film.

For the second time, two nominated films have two female producers.

2016 Eight films nominated.

Moonlight. (WINNER) Adela Romanski, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

Hell or High Water. Carla Haaken and Julie Yorn.

Hidden Figures. Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenro Topping, Pharrell Williams, and Theodore Melfi.

Lion. Emile Sherman, Iain Canning, and Angie Fielder.

Manchester by the Sea. Matt Damon, Kimberly Steward, Chris Moore, Lauren Beck, and Kevin J. Walsh.

Adela Romanski and Dede Gardner become the eleventh and twelfth winners.

For the second time, two women win for the same film.

For the second time, eight women are nominated, which so far remains the record.

Why should these names be hidden?

So we have overall 88 nominations for women, with twelve women winning Oscars for producing films. That compares with four nominations and one win for female directors. Women have not come all that close to parity with men in the producing category, but compared to the directors category, which people seem to take as a bellwether for the status of professional women in Hollywood, it’s spectacular. Moreover, we can see a fairly steady growth over the past twenty-three years, to the point where seven or eight producing nominations a year routinely go to women.

Of course, Oscars are not the only or the most objective way of measuring women’s power in Hollywood. One could try a similar examination of the number of women producing Hollywood’s top box-office films over the years. I assume there would be a similar growth in numbers, but the measurement would probably be a little more nuanced. That would be a much bigger project than would fit in a blog entry–even entries as long as the ones we occasionally favor our readers with. The San Diego State University study I mentioned earlier took an approach of this sort, and I’m sure there is deeper digging to be done among the statistics revealed by such research..

Given the way the Oscars have captured the public’s and the industry’s imaginations, however, the growing number of female producers being honored is a good way to point out that things may be better than they seem when one focuses narrowly on the directors category.

After all, the prescription for putting more women in the director’s chair and behind the camera and so forth is always that more female producers and writers are needed, making films for women and by women. This seems reasonable, and yet the question remains, if women are doing so well, relatively speaking, in rising to the top as producers, why, over the twenty-three years since 1994 haven’t they hired more women at every level for their film crews? (Of course, some of them have acted as producer-directors on their own projects.) Why hasn’t Kennedy, who has been firing and hiring male directors for Star Wars projects lately, ever given a female director a shot at it? Maybe she will at some point, as the evidence grows that women can create hits.

Perhaps most women producers are constrained by their fellow producers on projects, who are often men. They may feel pressured to reassure studio stockholders and financiers by sticking with the tried and true. And yet there do finally seem to be signs that studios are looking beyond the obvious pool of talent. Patty Jenkins, an indie filmmaker, directs Wonder Woman to unexpected success. Taika Waititi, a Maori-Jewish indie filmmaker from New Zealand, suddenly finds himself directing Thor: Ragnarok, which shows every sign of becoming a hit. With luck, the effect of the rise of female producers, as well as of more broadminded male ones, will finally have a significant impact on both gender and ethnic diversity in Hollywood filmmaking.

In closing, I would suggest to the press that it would be helpful for them in writing their endless awards coverage to list more than just the titles of the Best Picture nominees. Add the names of their producers, who are in effect nominated for Oscars. Treat them more like stars, the way you do with directors. I realize that there are often lingering disputes over which of the many producers attached to some films are actually the ones eligible to accept Oscars for them. But once such disputes are resolved, these “nominees” should be listed, and certainly after the awards are given out, they should be part of the historical record of Oscar nominees and winners. This would help both the public and the industry to get the big picture, not just the Best Picture.

[Oct. 24, 2017: My thanks to Peter Nellhaus for pointing out Julia Phillips’ win for The Sting in 1973. I have corrected the text accordingly.]

The Shawkshank Redemption (1994).

BABYLON and the alchemy of fame

Babylon (2023).

DB here:

The circus parade has just passed, and behind it comes a little man mopping up all the droppings left by the lions, tigers, camels, and elephants. Somebody calls out, “Why don’t you quit that lousy job?”

The little man answers: “Are you kidding? And leave show business?”

From one angle, the joke anticipates the dramatic arc of Babylon. Damien Chazelle’s film traces how five characters seeking a future in the movies immerse themselves in a debauched culture, all for the sake of the dream machine.

For trumpeter Sidney Palmer and singer/actor Fay Zhu, the movie moguls’ bacchanals pay the bills and allow networking. Jack Conrad, a major star, loves being a drunken libertine but expresses contempt for the films he makes, movies that are only “pieces of shit” rather than innovative high art. Manuel Torres becomes an all-purpose gofer on set and eventually a studio executive, trying to work within the system. Nellie LaRoy is attracted to the movie world as much for the whirl of drink, drugs, dance, gambling, and fornication as for the glamor drenching the screen. Finding her film persona as the Wild Child, she can act by acting out.

These characters, all from working class origins, are brought together at a moment of technological upheaval: the period 1926-1934, with the establishment of talking pictures. This would seem to threaten moviemaking, not to mention the high life offscreen. Other pressures include the stock market collapse and the resulting depression, along with the establishment of a stricter standard of what could be depicted onscreen, the famous Hays Code. (The Code isn’t mentioned directly in Babylon, but it’s suggested as part of a broader concern with morality in the film colony.)

By the time sound has fully arrived, all of Babylon‘s primary characters, voluntarily or not, are no longer working in the Hollywood industry. Fay Zhu leaves for European production. Sidney, whose band is ideal for sound cinema, quits in disgust after he’s forced to darken his skin further. When the press and the public turn against Jack, he commits suicide. Nellie dances off into darkness and a lonely death. Manny, vainly in love with Nellie, can’t halt her self-destruction and has to flee town to avoid reprisals from the mob. From this angle, a confluence of debauchery and technology has wrecked whatever spark of life the system had.

The bleak satire that is Babylon poses a host of questions. Why, for instance, are there apparently deliberate anachronisms? The backdrop sets for the Vitoscope’s outdoor filming would be unlikely for 1926. Jack misquotes Gone with the Wind a decade before the book was published. The vast opening orgy seems more typical of Von Stroheim’s films than any actual Hollywood party on record. And given Vitoscope’s marginal status, how does the studio head afford such a mansion?

But I’m interested today in the ways the characters seek fame. I think their situations are a development of qualities we’ve seen in other Chazelle show-biz films. One way or another, nearly all those characters have sought to find a creative impulse that can make the compromise with a corrupt system yield some artistic rewards. The pressures and temptations of Babylon are extreme versions of factors we’ve seen at work in Whiplash and La La Land, but the characters react rather differently.

The suicidal drive for perfection

Whiplash (2014).

I think about that day

I left him at a Greyhound station

West of Santa Fé

We were seventeen, but he was sweet and it was true

Still I did what I had to do

‘Cause I just knew. . . .

These are the first lines we hear at the start of La La Land. Sung by a young woman slipping out of her car, they foreshadow the film’s plot developments. Sebastian and Mia, the couple at the center, both put their careers ahead of their love for each other and separate at the end. Each seeks success–Mia in screen acting, Sebastian in starting a jazz club–and that drive blocks a compromise in which one or both might give up their dreams for the sake of staying together.