Archive for April 2019

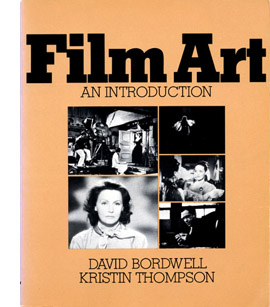

Frisky at forty: FILM ART, 12th edition

DB here:

The first edition of Film Art: An Introduction rolled into an unsuspecting world in 1979. Its butterscotch jacket enclosed 339 pages of text and black-and-white illustrations. It was, I think, the first film studies textbook to use frame enlargements instead of production stills. It was definitely the first to argue for a systematic aesthetic of cinema integrating principles of form (narrative/nonnarrative) with style (techniques of the medium). Our goal, of course, was to enhance the readers’ appreciation of the range and power of film as an art form.

Not that there wasn’t a lot of room for improvement. Across three publishers–Addison-Wesley, then Knopf, and finally McGraw-Hill–the book has gained subtlety, precision, bulk, and color images. It now has a suite of online supplements in the form of aids for teachers and video clips for student reference, and the website you’re now visiting. Then there’s our streaming series on the Criterion Channel.

Not that there wasn’t a lot of room for improvement. Across three publishers–Addison-Wesley, then Knopf, and finally McGraw-Hill–the book has gained subtlety, precision, bulk, and color images. It now has a suite of online supplements in the form of aids for teachers and video clips for student reference, and the website you’re now visiting. Then there’s our streaming series on the Criterion Channel.

The core of our efforts remain the ideas and information we explore in the text. That material, happy to say, has found support among teachers, scholars, and writers of other textbooks. Through their suggestions and criticisms, we’ve had four decades to refine what Kristin and I initially set out, and on the eleventh edition Jeff Smith joined us to make things even better.

What’s new about this twelfth edition? Of course, we’ve updated it. We incorporate examples from Get Out, Son of Saul, mother!, Moonlight, Guardians of the Galaxy, Tiny Furniture, Inside Man, Wonderstruck, Dunkirk, Fences, Manchester by the Sea, Baby Driver, The Big Sick, Hell or High Water, Hostiles, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, The Blind Side, Opéra Mouffe, My Life as a Zucchini, Kubo and the Two Strings, Lady Bird, Birdman, The Lost World: Jurassic Park, Tangerine, A Ghost Story, Snowpiercer, The Grand Budapest Hotel, and other recent titles.

One of the biggest changes involves the addition of an analysis of social and political ideology in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. This detailed look at Fassbinder’s melodrama of prejudice replaces our study of masculinity and violence in Raging Bull. That earlier piece will be posted for free access on this site, joining analyses from earlier editions on this page.

The most evident difference, signaled on the cover you see above, is a new case study of how a film gets made.

Production: The hows and whys

The book’s opening chapter,”Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business,” matters a lot to us. We try to provide concrete, systematically organized information about how people work with technology and within institutions to implement the techniques we’ll survey in later chapters. At the same time, our discussion of production, distribution, and exhibition tries to show how filmmaking institutions shape creative choices about form and style. Perhaps because we try to make those choices down-to-earth, we’ve been pleased to find that Film Art is used in film production courses.

For several editions, Michael Mann’s Collateral served us well as a model of how decision-making in the production process shaped the final film. We thought, however, it was time to refresh that chapter, and La La Land provided us rich opportunities. We had already written blog entries (here and here) about aspects of the film, but we wanted learn more about how it had been created.

Made by a director not much older than our students, La La Land was perfect for a book that tries to be both up-to-date and sensitive to film history. From the burst of ensemble energy in the opening traffic jam to the parallel-reality ballet at the end, Damien Chazelle’s film was both contemporary and classical, what Kristin calls “a modern, old-fashioned musical.” We thought it would help students see that a young filmmaker can draw on tradition while staying firmly in our moment.

The film’s production decisions were well-documented, so we were able to trace four areas of creative choice. By considering the film’s mise-en-scene, camerawork, editing, and sound, we could set up the major stylistic categories to come in later chapters. For example, Jeff could point out unique features of Justin Hurwitz’s score.

We were lucky to get guidance from Damien himself. He reviewed our analysis, and then went far beyond the call of duty. He came to Madison to talk with our students (chronicled here). He sat for interviews with the Criterion Channel on Jean Rouch and Maurice Pialat. He did three Q & A’s. He even took snapshots with his fans.

And Damien energetically helped us secure rights to the cover image, a process that all writers of film books approach with fear and trembling. In short, he proved a total mensch. The fact that he had already read our work when we first contacted him encouraged us in the belief that we might be helping young filmmakers find their way.

Film Art wherever you go

Film Art is now available in a variety of formats and prices. The print edition is now a looseleaf, unbound one. Bound copies still circulate for rental. Students may also rent or buy the e-book edition, which comes packaged as a digital resource called Connect. It’s possible to merge some of these alternatives. The various options for getting the book are charted here.

The Connect package includes teaching aids for the instructor (self-tests, quizzes) and access to thirty-six film extracts, courtesy of the Criterion and Janus companies. There are also four fine videos on production practice by our colleague Erik Gunneson.

As I discussed at exhausting length when I previewed our new edition of Film History: An Introduction, the variety of formats for the book reflects not only changes in technology and the publishing market but also changes in consumer preferences.

However it’s accessed, Film Art: An Introduction still makes us happy. We’ve tried our hardest to help readers understand a bit more about the techniques and effects of cinema. As we point out in the book, thanks to smartphones everybody is a filmmaker now. We think that students’ hands-on experience prepares them for our efforts to understand the creative choices filmmakers have faced from the very beginning.

Thanks as ever to the staff at McGraw-Hill: our editor Sarah Remington and the team consisting of Danielle Clement, Sue Culbertson, Maryellen Curley, Joni Fraser, Ann Marie Jannett, and Elizabeth Murphy. Thanks as well to Kaitlin Fyfe and Erik Gunneson here at the Department of Communication Arts, UW–Madison. And of course thanks to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, and their colleagues at Criterion.

Instructors who want to learn more about this edition can find a McGraw-Hill representative here.

Jeff Smith, who wrote the analysis of Ali: Fear Eats the Soul for our book, also provided an incisive discussion of staging in the film for our series on the Criterion Channel.

There’s a fuller account of how we came to write Film Art in our announcement of the previous edition.

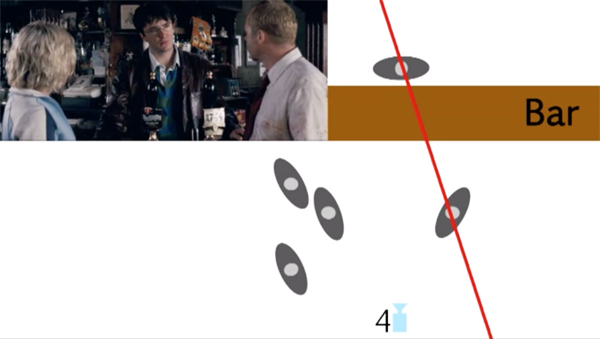

Video supplement: Shifting the Axis of Action in Shaun of the Dead.

Two essential German silent classics from Edition Filmmuseum

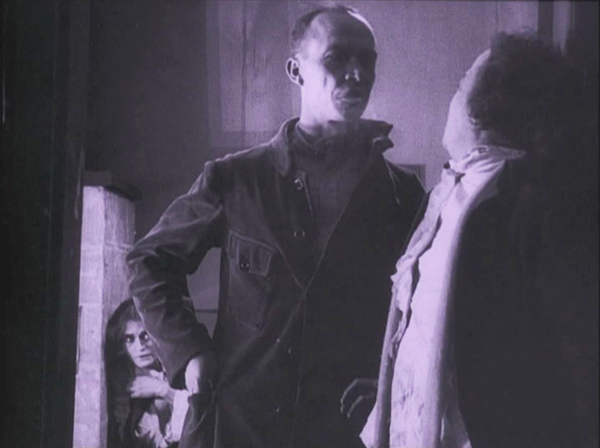

Der Gang in die Nacht (1921).

Kristin here:

Back in 2016, the Munich Film Archive gave us a preview of the restored version of F. W. Murnau’s earliest surviving film, Der Gang in die Nacht (1921). The print was splendid, and David posted an entry in which he analyzed the film’s style and situated it in the context of German cinema in the early post-World War I years. He tied the film to the tableau style that developed in much of the world outside the USA during the 1910s and which began to adjust to Hollywood norms of continuity editing just when Murnau was making films like Der Gang in die Nacht.

In that entry he used several frames from the restoration, and a glance over it will show its spectacular visual quality. I won’t spend much time on that film here, since David covered it so thoroughly. He wrote, “We can hope that the film will soon appear on DVD. Remember DVDs?” He and I certainly do. The Edition Filmmuseum obviously does as well. They continue to release their restorations and collections of more recent experimental films solely on DVD. Maybe Blu-rays are simply too expensive to produce, or perhaps the staff there consider Blu-rays a passing fad, like talkies. At any rate, this DVD release looks great (see above). it can easily be ordered from the Edition Filmmuseum’s shop (English page).

Apart from the tableau staging and the proto-continuity cut-ins that David discusses, there are some impressive depth shots–involving, as often happens in 1910s films, spectators in a theater box with the stage in the distance.

The film was restored from the original camera negative, though negatives were not edited in the final form of the film. By studying Murnau’s shooting script and restoration work previously done by Enno Patalas, the team were able to reconstruct the films’s editing and intertitles. The tinting and toning are based on the conventions of the period and are thoroughly plausible. David’s remarks in his earlier post are condensed slightly into this still applicable summary quoted in Stefan Drössler’s notes on the film:

The Munich Film Museum’s team has created one of the most beautiful editions of a silent film I’ve ever seen. You look at these shots and realize that most versions of silent films are deeply unfaithful to what early audiences saw. In those days, the camera negative was usually the printing negative, so what was recorded got onto the screen. The new Munich restoration allows you to see everything in the frame, with a marvelous translucence and density of detail. Forget High Frame Rate: This is hypnotic, immersive cinema.

The DVD lives up to that description.

A 1921 double feature

Without much fanfare, this release also contains another major classic of 1921, Scherben (“Shattered” or more literally “Fragments”). Its director, Lupu Pick, is probably best known today from his performance as the tragic Japanese spy, Dr. Masimoto, in Fritz Lang’s Spione (1928). He was, however, a prolific director from 1918 to 1931. (His acting career lasted from 1910 to 1928.) Many of his films are apparently lost, though I have seen two: Mr. Wu (1918) and Das Panzergewölbe (1924), both good but conventional films.

As a director, however, he is best known for making two of the main films in the brief vogue for Kammerspiele: Scherben and Sylvester, or New Year’s Eve (1923). These two films were scripted by Carl Mayer, who, as Anton Kaes points out in the accompanying booklet, wrote all the German Kammerspiele films: Hintertreppe (1921, dir. Leopold Jessner), Sylvester, and Der letzte Mann (1924, dir. Murnau). One might add Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Michael (1924), shot in Germany and scripted by Thea von Harbau.

Mayer was all in favor of films with no intertitles–though in practice that meant almost none. Der letzte Mann is one such, with an expository title introducing the sarcastic happy ending that Mayer was forced to add. Scherben is another. Near the end there is a single dialogue title. Moreover, Scherben’s subtitle is Ein deutsches Filmkammerspiel: Drama in fünf Tage. The five days are divided into the five reels of the film, and each is introduced by an expository title. There are a few letters and other texts that convey vital information, but overall the action is presented pictorially.

Scherben might be said to represent the slow cinema of its day. Its remarkable and lengthy opening shot is filmed from the front of a slowly moving train, simply showing progress along a track in a snowy landscape (above).

The main character (played by Werner Krauss, famous as Dr. Caligari) is a linesman, living with his wife and daughter in an isolated house. Their stultifying daily routine is gradually set up during the early scenes. Drama is introduced when a railroad inspector comes to visit, staying with the family. He and the daughter are immediately attracted to each other, spending a night together. The wife discovers this, staggers out into the snow to pray at a local shrine, and freezes to death. The tragedy deepens from there.

The film proceeds at the notoriously languid pace of German art films of the period. Pick injects stylistic flourishes derived from trends of the period. For some reason, the hallway of the family’s house has little Expressionistic painted highlights dotted around it.

Werner Krauss often acts “with his back,” well before Emil Jannings was praised for doing so in the framing prison scenes of E. A. Dupont’s Variety (1925.)

Pick calls upon the 1910s obsession with mirrors when the inspector reacts to accusations that he has seduced the linesman’s daughter.

Pick also evokes the depth staging of the tableau style, with small areas of the screen glimpsed in the background, most notably in the scene where the mother discovers the lovers together. (See below.)

The print is not as spectacular as that of Der Gang in die Nacht, having been reconstructed from prints in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow and the Bundesarchiv in Berlin without extensive digital restoration. Still, we should be glad to have this milestone film available. Taken together, the two films make a welcome addition to the number of German classics available for home viewing and classroom use.

Scherben (1921).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Four for the road

Suzanne Simonin, La religieuse de Denis Diderot (1966).

The Wisconsin Film Festival is over, and already we’re looking forward to the next one. In the meantime, here are our last thoughts on some films that impressed us.

Kristin here:

Dürrenmatt in Dakar

Hyenas (1992).

Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty is known mostly for his two feature films, Touki Bouki (“The Hyena’s Journey,” 1973) and Hyenas (1992), and less so for a handful of shorts. Though unable to direct for long stretches of time, Mambéty, who died of cancer in 1998, has been well-served by preservationists. In 2013, Touki Bouki was released by the Criterion Collection in a box set of restorations by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project. Now the Cinémathèque Suisse has sponsored a 4K restoration of Hyenas. As the echoes in the two titles suggests, Hyenas was intended to be the second film in a thematic trilogy about the corruption of ordinary people by greed. The third film, Malaika, was planned, but Mambéty’s early death intervened.

Hyenas is based on Swiss playwright Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s dark 1956 comedy, Der Besuch der alten Dame, known in English as The Visit. The film follows the story of the original fairly closely, at least in the play’s first two acts.

The action is set in the village of Colobane (Mambéty’s hometown, where Touki Bouki was also set). The village has fallen on hard economic times, and the genial local shopkeeper, Dramaan, helps keep the place going by extending credit to his regular customers. City officials announce the imminent arrival of Linguère Ramatou, a Colobane woman who left the village and has become extremely wealthy. Dramaan, who had courted Ramatou in their youth, is delegated to greet and butter her up (above). She, however, accuses him of having impregnated her and refused to confess to being her baby’s father. Forced to go abroad, she became a prostitute, was severely maimed in a plane crash, and ended up rich. (How is never explained). Now she promises the villagers great financial aid if they will agree to kill Dramaan.

Although the mayor indignantly refuses, Dramaan soon notices that his fellow citizens are buying luxurious goods that they should not be able to afford. He futilely tries to get local officials to protect him from assassination. All this is played for bitter comedy by an engaging cast of non-professionals. The thematic point is made clear, especially when Mambéty intercuts a pack of hyenas lurking in the nearby brush with a mob of locals who prevent Dramaan from fleeing the town.

It helps to know something about the setting, which would be familiar to Senegalese audiences. The film gives the impression that Colobane is a remote country village. In fact it is a small arrondissement of greater Dakar, a major port on the west coast of Senegal. In a lengthy overview of the director’s life, including an interview with Mambéty shortly before his death, N. Frank Ukadike explains:

The Colobane of Hyènes is a sad reminder of the economic disintegration, corruption, and consumer culture that has enveloped Africa since the 1960s. “We have sold our souls too cheaply,” Mambéty once said. “We are done for if we have traded our souls for money. That is why childhood is my last refuge.” But what remains of Colobane is not the magical childhood Mambéty pines for. In the last shot of Hyènes, a bulldozer erases the village from the face of the earth. A Senegalese viewer, one writer has claimed, “would know what rose in its place: the real-life Colobane, a notorious thieves’ market on the edge of Dakar.”

The last shot is startling, as it reveals for the first time (at least to non-Senegalese viewers) that Colobane is located right up against a city. Possibly in Mambéty’s childhood it was a village later absorbed by the spread of Dakar. It’s not clear from the film when the action is taking place, although Ukadike suggests that it must be in the 1960s or later. The implication of the final shot is that the corruption of the villagers is as much an urban problem as a rural one–if not more so.

The restoration has resulted in vibrantly colorful images that emphasize the indigenous costumes, particularly of Ramatou and her entourage (see bottom). Metrograph is releasing the film theatrically in the US, and with luck a Blu-ray will eventually make it more widely available.

David here:

Anomalies in the space-time continuum

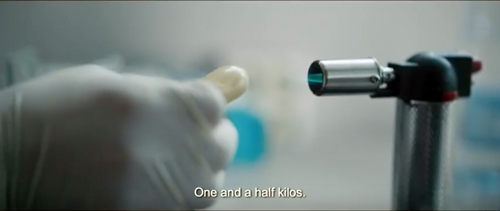

Vultures (2018).

Almost from the start, popular moviemaking has played tricks with linear time and space. Edwin S. Porter’s Life of an American Fireman (1903) contains both a dream and editing that replays key actions from two viewpoints. The more developed silent cinema explored flashbacks, subjective viewpoints, and other strategies. By the 1940s, filmmakers around the world were trying these tricks in sound movies, all seeking to enhance curiosity or suspense or surprise.

Most of the movies that play with space and time resolve the uncertainties clearly. The opening of Mildred Pierce skips over important moments without telling us, but by the end a flashback fills them in. This sort of gamesmanship has remained a permanent resource of mainstream cinema, especially in genres that rely on crime and mystery. Think of Pulp Fiction or Memento or The Usual Suspects, or more recently Identity, Side Effects, or the many heist movies that conceal crucial parts of the plan.

Börkur Sigpórsson’s debut feature Vultures is a good example of a conventional crime film made more intriguing by the way it’s told. The basic story is formulaic. An Icelandic real-estate developer needs to replace money he’s embezzled, and so sets up a drug-smuggling deal. He enlists his ex-con brother Atli to help the mule, a Serbian woman named Zonia, get through airport security. After that, Zonia has to be sequestered until she evacuates the pellets of cocaine she’s swallowed. In the meantime, Lena the policewoman gets on the trail. The whole scheme falls apart when Zonia collapses and Atli starts to take pity on her, while Erik decides to get the pellets by any means necessary.

This straightforward arc of action is presented in fragments that jump among time frames. Before the credits, we see Zonia hesitantly gulping down the pellets, getting sick on the flight into Reykjavík, and hiding in a toilet. She’s frightened when she hears a knock on the door.

Flash back to follow Atli and Erik planning the smuggling scheme. Then, via brief replays, we’re back with Zonia swallowing the pellets, Zonia on the plane (with Atli now revealed as a fellow passenger), and Zonia bolting to the toilet. He’s the one knocking on the door.

This sort of back-and-fill pattern sharpens our interest by delaying the revelation of who’s knocking on the door, while also filling us in on the brothers’ scheme. The interpolation also allots some sympathy to Atli. In the flashback he’s shown visiting his drug-devastated mother and trying to reassure his wife that he’s going to be providing for her and his son. Soon we see him distracting the airport police so that Zonia can pass through freely. The deal seems to have come off. All they have to do is retrieve the pellets.

Abruptly we skip far ahead in time to reveal a bit of the end of the story. I won’t provide a spoiler, but let’s just say that whatever certainty we gain about the outcome is provisional and partial. Still, with this small anchor in Now, the narration doubles back again through a long flashback that traces the unraveling of Erik’s scheme.

As often happens with flashback construction, the time-shifting in Vultures has a double impact. It teases us with hints about what will happen, and it forces us to concentrate on how and why it happens. (Something similar is at work in Duvivier’s Lydia, which I analyze in this month’s “Observations on Film Art” installment on the Criterion Channel.) Told more linearly, Vultures wouldn’t have been so engaging, I think. Nor would it have so sharply focused our concern about the characters’ decisions. And that crucial glimpse of the future allows us to hope that Zonia’s fate isn’t what it would have seemed to be if her story had been presented in 1-2-3 order. As usual, the how of storytelling is as important as the what.

During the 1950s, films not only fractured their action in challenging ways but also refused to resolve all the questions that were raised. We might not fully understand everything that happened. This strategic ambiguity has been central to what’s sometimes called “art cinema,” and is nicely showcased in Pause, another debut feature. If Vultures plays hob with the crime movie, Cypriot director Tonia Mishiali gives us a jagged domestic drama, a diary of a going-mad housewife.

Elpida is falling apart. The darkly comic opening scene, with a doctor ticking off a virtually endless list of her ailments, portrays her as enervated and beaten-down. How she got that way becomes clear. Her husband Costas shovels in food in angry silence. He watches soccer on their main TV, while she has to watch her violent crime videos with headphones. He comes and goes as he pleases; she steals time to attend a painting class or have coffee with a neighbor. When he decides to sell her car without further discussion, and when a young contractor comes to repaint their apartment house, Elpida dares to imagine life without the lout she married.

Imagine is the key word. From her drab routines we pass without warning into fantasies of resistance, escape, and payback. At first, the visual narration makes clear that these acts of rebellion are wholly in her mind. As the film goes along, however, the boundary gets fuzzy. Is the breezy workman making a pass at her, or is she just wishing for it? Is she really drugging Costas’ coffee? And is murder in the offing?

The cinematography won’t tell us. Like Vultures, Pause presents its story through a now-standard blend of planimetric framings and a “free-camera” handheld style that suggests nervous urgency. The fantasies are treated through both techniques.

A woman’s domestic discontents, projected through fantasy, has been a mainstay of cinema since at least Germaine Dulac’s Smiling Madame Beudet (1923). Here, Mishiali’s careful pacing of Elpida’s household chores establishes a solid rhythm that’s broken by the imaginary moments. Like many modern films, the drama builds up by immersing us in the characters’ routines and then disturbing them with sudden outbursts. Yet the climax is remarkably quiet, further teasing us about what may or may not have happened. In any case, by the end, Elpida may be liberated. Yet her final laughter, echoing through the end credits, doesn’t feel especially jubilant.

Get thee from a nunnery

Suzanne Simonin, La religieuse de Denis Diderot was Jacques Rivette’s second feature. In 1962 he submitted a screenplay to censorship authorities but was told that if the film were made it would probably be banned. After another try in 1963, a third version was cautiously accepted, with the warning that it might well be forbidden to viewers under 18.

Shooting began in September of 1965. Catholic groups immediately objected. After a public outcry, in which Godard called on Minister of Culture André Malraux to intervene, there was a screening at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival. The film wasn’t released in France until July of 1967. Usually known as La religieuse (The Nun), it’s gone largely unseen in America. We were lucky to screen the sparkling 4K version that Rialto is now distributing.

The story is set in the years 1757-1760. Suzanne, illegitimate daughter of a prominent household, is parked in a convent, like many women who had no other life chances. Her first Mother Superior, who treats her with affection, dies and is succeeded by a harsh younger woman. Suzanne loves God but resists the rigid discipline. She’s beaten and starved, denied access to her Bible, and believed to be possessed.

She’s rescued by church officials and a kindly lawyer, who oversee her transfer to a very different convent. That’s run by a sexy, permissive Mother Superior who seems anxious to bed our heroine. Suzanne finds the license of her new home as disquieting as the asceticism of the old one. In the end, she escapes with a priest who abandons his vows. Soon she’s on her own in a grimy secular milieu.

No wonder the French church was outraged. True, Diderot’s novel was a classic, and Rivette had already mounted the story as a play. But on film the revelation of ecclesiastical corruption was vivid and shocking, and the presence of New Wave star Anna Karina gave it undeniable prestige. Popularity, too: It attracted more than 2.9 million spectators, making it the ninth most successful release of the year. (Films by Godard, Rohmer, Bresson, Bergman, and Chabrol drew fewer than half a million.) Rivette’s first feature, Paris nous appartient (1961) had drawn only about 29,000. As often happens, creating a scandal proved good for business.

Seen today, La religieuse is hard to imagine as a mass-audience hit. Rivette presents his inflammatory plot with a calm austerity. The dominant colors, at least for the first seventy minutes or so, are shades of beige, brown, white, and black. Shot in very long takes, usually at a distance from the action, the scenes are confined largely to chapels, corridors, and sparsely furnished rooms. La religieuse exemplifies what one wing of Cahiers du cinéma called “classical” direction. As a critic, Rivette admired Hawks, Preminger, Rossellini, the American Lang, and late Dreyer for their sober, unemphatic staging of performances. In place of flashy angles and aggressive cutting, mise-en-scène should center on expressive bodies and faces captured from a respectful distance.

In a 1974 interview, Rivette explained that his most proximate influence was Mizoguchi Kenji–a director who made the restrained, long-take scene central to his style. While most scenes in La religieuse are cut up a little, Rivette seldom moves nearer than medium-shot distance. He uses close-ups with the same parsimony that Mizoguchi displays. Most directors would have cut in to a closer view of Suzanne when, kneeling, she’s asked to pray to Jesus, but Rivette obstinately makes her gesture part of a nearly two-minute shot.

This might seem a stagy approach, especially if you remember Rivette’s interest in varieties of theatre. But like other Cahiers critics, he believed that “classical” filmmaking harbored qualities that also kept cinema “modern,” on the aesthetic and moral edge.

In the abrupt editing of the long takes in Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964), Rivette found a revival of the powers of montage. Dreyer didn’t hesitate to interrupt moving shots. Rivette felt that the film exploited “tantalizing cuts, deliberately disturbing, which mean that the spectator is made to wonder where Gertrud ‘went’; well, she went in the splice.”

In La religieuse, most cuts within scenes are axial, not reverse angles, and they often mismatch action in ways that break the flow of the long takes.

At other moments, Rivette’s editing subjects his distant shots to ellipses that recall Godard’s jump-cuts and Resnais’ experiments in Muriel. We get space-time anomalies more abrasive than those in Vultures and Pause.

Suzanne is in her cell, fretfully pacing. She pauses and, thanks to a cut, seems to look at herself at prayer.

She drifts to her needlework, and suddenly a cut takes her back to the other side of the room.

While she looks in the mirror, the camera backs up and, continuing over a cut, arcs to the right to reveal that she’s already flung herself onto her bed.

Where did Suzanne go? Well, she went in the splices.

It’s wonderful to have this quietly astonishing film available again. The ever-reliable Kino Lorber is bringing out a Blu-ray edition next month, with commentary by Nick Pinkerton, a critical essay by Dennis Lim, and a new documentary about the production. Don’t you want one? I bet you do.

Thanks as usual to the coordinators of our film festival–Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, and Zach Zahos–as well as their colleagues and the hordes of cheerful volunteers who kept everything running smoothly.

The information about Colobane from N. Frank Ukadike is from his article on California Newsreel. For a trailer of the restored Hyenas, see here.

The information on La Religieuse‘s censorship struggles comes from Jean-Michel Frodon, L’Âge moderne du cinéma français: De la Nouvelle Vague à nos jours (Flammarion, 1995), 149-151. Rivette’s comments on Mizoguchi’s influence are in this Film Comment interview from 1974. His remarks on Gertrud are part of a 1969 Cahiers du cinéma panel discussion, “Montage,” translated in Rivette: Texts and Interviews, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum (British Film Institute, 1977), 86-87. The conversation is available online at DVDBeaver. I derived attendance figures from Simon Simsi, Ciné-Passions: 7e art et industrie de 1945 à 2000 (Dixit/CNC, 2000), 46-47.

What’s an axial cut? Glad you asked. Kurosawa uses them (here too), as does Eisenstein and his Soviet peers and French avant-gardists. Silent cinema has plenty, but so do the films of Wes Anderson and John McTiernan. And The Simpsons, often.

Our first full day of the festival opened with a screening of Ozu’s Good Morning (Ohayo), selected by guest Phil Johnston, and the final show a week later presented Jackie Chan’s Police Story. (The first is already available in a Criterion disc, the second is coming soon.) Now that’s what I call a film festival.

Hyenas (1992).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Not docudramas, but docus as dramas

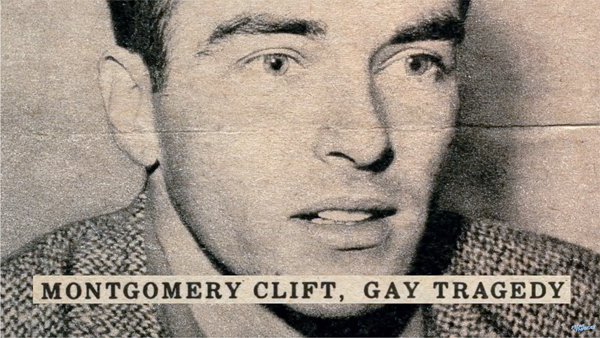

Making Montgomery Clift (2018).

DB here:

Our days and nights at our annual film festival would have been hopelessly frustrating if we hadn’t already seen several of the fine items on offer. At other festivals we caught Asako I and II, Ash Is Purest White, Dogman, The Eyes of Orson Welles, The Girl in the Window, Girls Always Happy, The Image Book, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Lucky to Be a Woman, The Other Side of the Wind, Peterloo, Rosita, Shadow, Styx, Transit, and Woman at War. As you can see, our programmers assembled a spectacular array of movies. Most of these we’d happily watch again, but there were so many new offerings we had to resist.

With this elbow room I could pay attention to three documentaries I’d been looking forward to. They had all the appeal of a fictional film, with keen plots and tricky narration and fascinating characters. It didn’t hurt that two were about world-class celebrities and the third appealed to my deepest conspiracy-theory instincts.

Heart of Glasnost

Werner Herzog’s Meeting Gorbachev was a surprisingly conventional effort for this legendarily odd filmmaker. As my colleague Vance Kepley remarked, Herzog typically makes documentaries of two types. He probes eccentric personalities (the “ski-flyer” Steiner, or a man trying to hang out with grizzly bears) or he treks into remote, dangerous landscapes (Antarctica, a swift-moving volcano, the fires of Kuwait).

But this portrait of Mikhail Gorbachev is neither. Herzog’s interview with the elderly but still vigorous Soviet leader is interrupted by biographical inserts tracing his career, his struggles, and his policies. Newsreel footage and other talking heads provide context in a mostly straightforward account of the man’s life and work. Only a story about tree slugs briefly diverts Herzog’s attention.

The film revives our appreciation of a politician many people have tried to bury. Gorbachev emerges as a thoughtful, upbeat man who tried to make the Soviet Union more democratic and open to the popular will, to create Communism with a human face. But he triggered events that cascaded too quickly. He broke up the USSR but also cleared a path for economic collapse and a corrupt kleptocracy. His suggestion for his tombstone inscription: We tried.

Herzog’s montages dramatize the breakdown of national borders, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the coup that destabilized reforms while Gorbachev was away from Moscow. The main principle of swimming with sharks in a bureaucracy is: Don’t tell anybody what you’re going to do until you do it. The 1991 unseating of Gorbachev by Yeltsin reminds me of a second: Don’t take vacations.

Meeting Gorbachev is actually a double portrait, because Herzog puts a good many personal feelings into it. He remembers the emotion he felt as Germany reunited. Gorbachev’s call for “a common European home” rouses him to recall his youthful Wanderjahr when he walked across the continent.

Although I don’t think the name Trump is mentioned, his shadow falls over the whole film. Portraying a sane, reasonable leader today seems virtually a bid for controversy. Gorbachev reminds us of the reductions in nuclear weaponry that he negotiated with Reagan and Thatcher. “People say that Reagan won the Cold War. Actually, it was a joint victory. We all won.” The idea of pursuing policies that benefit the whole world seems oddly old-fashioned right now.

When Herzog gives us a glimpse of a robotic Putin peering down into the casket of Gorbachev’s beloved wife, we’re forced to register what Russia has become, and how the US is now complicit with it. Maybe this film has more of the director in it than I initially thought. As Herzog dared to declare in an earlier film, Nosferatu lives.

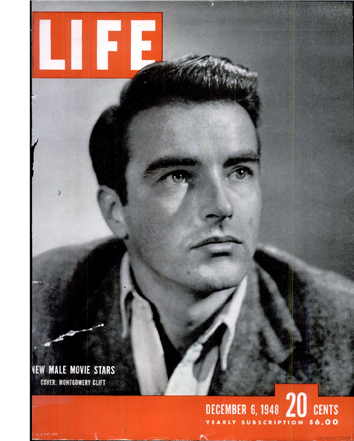

Unmaking an icon

Whenever I see Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift kiss in A Place in the Sun, I think: Here are the two most beautiful people in the Western world. I’m not alone. Clift was one of Hollywood’s most celebrated stars after the war, partly because he didn’t easily fit the molds of either the old guard or the new.

The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan).

The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan).

In this context, Clift looks like cannon fodder. Put him alongside Lancaster in From Here to Eternity, and you’ll find it hard to believe he’s the prizefighter; in that movie, only Sinatra looks skinnier. Delicate, with an innocent stare and an angular body, a wide-eyed Clift takes over his debut film, Red River (1948), from the lumbering John Wayne. Hawks claimed he told Clift that if he quietly watched the action from behind his tin coffee cup, he could steal every scene.

Clift carved out a space all his own. Late in his career, the tremor in his voice and a wary tilt of the head gave him antiheroic quality, as in Wild River (1960). Not for him the over-underplaying of Brando or the unpredictable gestures and dialogue cadences of James Dean. He has his own method, not The Method.

One of the many merits of Making Montgomery Clift, a fascinating documentary by Robert Clift and Hillary Demmon, is that it triggers such thinking about the actor’s craft. Emerging from a hillock of papers, home movies, video tapes, and audio tapes, the film documents two dramas–that of Clift’s life, and that of the process through which complex human beings get flattened into media clichés. As a bonus, we reap many insights into how actors shape their performances, sometimes against the grain of the script they’re handed.

On the life, we learn that Clift was often a buoyant, bisexual fellow, not the brooding and moody figure of legend. He was also a demanding artist who turned down juicy parts. When he signed up for a role, he insisted on vetting the script and sometimes rewriting it. In split-screen Clift and Demmon present the page on the left, scribbled up with Monty’s notes and excisions, and then run the scene alongside. The excerpts they give us from The Search and Judgment at Nuremberg show how a committed actor can strip an overwritten scene down to an emotional core.

If nothing else, Making Montgomery Clift shows us how performances shape movies: the actor as auteur. But it’s exactly this analysis of craft that’s missing from most film biographies. Those doorstop volumes revel in scandal and exposés because publishers think that a straightforward account of hard-won artistry–the sort of thing we routinely get in biographies of composers or painters–doesn’t suit movies. The result is glamor, excitement, sad stories, and banal interpretations rolled into one fat book.

This is the other drama so patiently traced by Clift and Demmon. They show how two 1970s biographies set a mold for the Tragic Homosexual story that has dogged the Clift legend ever since. Just as the filmmakers pay attention to the movies, they provide close readings of passages in the books, and the evidence of sensationalism, inaccuracy, and offhand speculation is pretty damning. One description of Clift’s injured face after his 1957 car crash savors brutal detail. And it’s not just the ambulance-chasers; passages from John Huston’s autobiography also radiate bad faith.

Clift understood that cookie-cutter journalism would oversimplify him. Thanks to the endless tapes he and his brother Brooks made of their phone conversations, we hear his quick condemnation of “pocket-edition psychology.” There’s a continuum between the tabloid headline, the talk-show time-filler, the celebrity memoir, and the bulging star bio. All try to iron out the wrinkles. During the Q & A, Robert Clift talked about traditional biographies as exercises in taxidermy: “It feels so real because it’s dead.” Hillary Demmon remarked that they wanted to “open up Monty to more readings.”

Making Montgomery Clift proves that academic talk about the “social construction” of this or that isn’t hot air. The film ranks with Errol Morris’s Tabloid as combining a fascinating life story (full of, yes, drama) with a serious argument about how celebrity culture reduces that story to captions and soundbites. Let’s hope the film makes its way to wider audiences, in theatres and on disc and streaming services. It belongs in the library of every college and university, so that students can get acquainted with an extraordinary performer, appreciate the art of star acting, and witness how the media shrink people to less than life size.

In the crosshairs of history

Like other baby boomers, I’m a connoisseur of conspiracy theories. But we have an excuse. Today’s kids grow up with school lockdowns and street shootings; we had assassinations. Patrice Lumumba (1961), Medgar Evers (1963), John Kennedy (1963), Lee Harvey Oswald (1963), the Freedom Summer murder victims (1964), Malcolm X (1965), Martin Luther King (1968), and Robert Kennedy (1968): this cavalcade of killings made political life seem a theatre of Jacobean intrigue.

Not the least of these was the 1961 death of the UN Secretary-General Dag Hammerskjöld. Hammerskjöld had pressed for peace in the Middle East and was a patient advocate for decolonization in Africa. En route to the breakaway Congolese province of Katanga, his plane crashed. For years many people, including former President Harry Truman, believed that the plane was shot down in order to murder Hammerskjöld.

So of course I had to see Mads Brügger’s Cold Case Hammerskjöld. It did not disappoint.

At first it seems cutesy, with the filmmaker dictating his findings to two African women typists, who occasionally turn to question him. He’s both pedantic and flamboyant (wearing white clothes to match the habitual outfit of a villain he will expose). In contrast there’s the veteran Hammerskjöld researcher Göran Björkdahl (on the right above beside Brugger). Björkdahl is a steady presence as the men question witnesses to the crash and then, crazily, set out to dig up the site. When they’re forbidden to do so, you might think that we’ve got another film about not making a film.

Instead, in the spirit of Morris’s Thin Blue Line, the story we’re investigating drifts into another story, and then another, as documents and witnesses and people who refuse to talk to the filmmakers lead to some appalling charges. Let’s simply say, to preserve the film’s shock value, that the Hammerskjöld case reveals SAIMR, a white supremacist militia for hire. The most horrifying claim about SAIMR and its leader is broached by a well-spoken mercenary purportedly haunted by guilt. His claim has been contested by researchers (as reported in the New York Times). Even if his charge doesn’t hold water, though, the existence of SAIMR seems well-documented.

We conspiracy theorists are often told that history proceeds by accident, not by intention. Yet some intentions succeed splendidly (viz. the killings itemized above), and some succeed by luck. Perhaps the darkest intentions chronicled in Cold Case Hammerskjöld were too crazy to be implemented. But that doesn’t lift responsibility from the feverish minds who dreamed them up, or from the institutions–perhaps mining companies, perhaps MI6 and the CIA–that gave them a hand. In an era when white supremacy has come on strong, Brügger’s film will remain the provocation it was intended to be.

One more entry will talk about still more films at this festival which so generously spoils us.

Thanks to film festival coordinators Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, Zach Zahos, and their dedicated staff for this year’s wonderful event.

Cold Case Hammerskjöld.