Archive for the 'National cinemas: Thailand' Category

Vancouver 2018: Crime waves

Burning (2018).

DB:

It’s striking how many stories depend on crimes. Genre movies do, of course, but so do art films (The Conformist, Blow-Up) and many of those in between (Run Lola Run, Memento, Nocturnal Animals). The crime might be in the future (as in heist films ), the ongoing present (many thrillers), or the distant past (dramas revealing buried family secrets).

Crime yields narrative dividends. It permits storytellers to probe unusual psychological states and complex moral choices (as in novels like Crime and Punishment, The Stranger). You can build curiosity about past transgressions, suspense about whether a crime will be revealed, and surprise when bad deeds surface. Crime has an affinity with another appeal: mystery. Not all mysteries involve crimes (e.g., perhaps The Turn of the Screw), and not all crime stories depend on mystery (e.g., many gangster movies). Still, crime laced with mystery creates a powerful brew, as Dickens, Wilkie Collins, John le Carré, and detective writers have shown.

We ought, then, to expect that a film festival will offer a panorama of criminal activity. Venice did last year and this, and so did the latest edition of the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some movies were straightforward thrillers, some introduced crime obliquely. In one the question of whether a crime was committed at all led–yes–to a full-fledged murder.

Smells like teen spirit

Diary of My Mind.

Start with the package of four Swiss TV episodes from the series Shock Wave. Produced by Lionel Baier, these dramas were based on real cases–some fairly distant, others more recent, all involving teenagers. The episodes offer an anthology of options on how to trace the progress of a crime.

In Sirius a rural cult prepares for a mass suicide in expectation they’ll be resurrected on an extraterrestrial realm. The film focuses largely on Hugo, a teenager turned over to the cult by his parents. Director Frédéric Mermoud gives the group’s suicide preparations a solemnity that contrasts sharply with the food-fight that they indulge in the night before. Similarly, The Valley presents a tense account of a young car thief pursued by the police. Locking us to his consciousness and a linear time scheme, director Jean-Stéphane Bron summons up a good deal of suspense around the boy’s prospects of survival in increasingly unfriendly mountain terrain.

Sirius and The Valley give us straightforward chronology, but First Name Mathieu, Baier’s directorial contribution, offers something else. A serial killer is raping and murdering young men, but one of his victims, Mathieu, manages to escape. The film’s narration is split. Mathieu struggles to readjust to life at home and at school, while the police try to coax a firm identification from him. This action is punctuated by flashback glimpses of the traumatic crime. The result explores the parents’ uncertainty about how restore the routines of normal life, the police inspector’s unwillingness to press Mathieu too hard, and the boy’s self-consciousness and guilt as the target of the town’s morbid curiosity.

This insistence on the aftereffects of a crime dominates Diary of My Mind, Ursula Meier’s contribution to the series. This too uses flashbacks, mostly to the moments right after a high-school boy kills his mother and father. But there’s no whodunit factor; we know that Ben is guilty. The question is why. Ben’s diary seems to offer a decisive clue (“I must kill them”), but just as important, the magistrate thinks, is his creative writing under the tutelage of Madame Fontanel, played by the axiomatic Fanny Ardent. Because she encouraged her students to expose their authentic feelings, Ben’s hatred of his father had surfaced in his classroom work. Perfectly normal for a young man, she assures the magistrate. No, he asserts: a warning you ignored. The shock waves that engulf onlookers after a crime, the suggestion that art can be both therapeutic and dangerous, the question of a teacher’s duty to both her pupils and the society outside the classroom–Diary of My Mind raises these and other themes in a compact, engaging tale.

Last hurrah of (movie) chivalry

Chinese director Jia Zhangke is no stranger to criminal matters. His films have dwelt on street hustles, botched bank robberies, and hoodlums at many ranks. Ash Is Purest White is a gangster saga, tracing how a tough woman, Qiao, survives across the years 2001-2018. Initially the mistress of boss Bin, Qiao rescues him from a violent beatdown using his pistol. She takes the blame for owning a firearm. Getting out of prison, Qiao tracks down the now-weakened Bin, who has taken up with another woman.

Ash Is Purest White tackles a familiar schema, the fall of a gang leader, from the unusual perspective of the woman beside him, who turns out to be stronger than he is. Most of the film is filtered through her experience, and along with her we learn of Bin’s decline and betrayal, along with his integration into the corrupt and bureaucratic capitalism of twenty-first century China. The second half of the film shows Qiao forced to survive outside the gang’s milieu. A funny scene plays out one of her scams: picking a prosperous man at random, she announces that her sister, implicitly his mistress, is pregnant. Just as important, Qiao’s adventures allow Jia to survey current mainland fads and follies, including belief in UFO visits.

Among those follies, Bin suggests, is a trust in mass-media images. As Ozu’s crime films (Walk Cheerfully, Dragnet Girl) suggested that 1930s Japanese street punks imitated Warner Bros. gangsters, so Jia’s mainland hoods model themselves on the romantic heroes of Hong Kong cinema. They raptly watch videos of Tragic Hero (1987) and cavort to the sound of Sally Yeh’s mournful theme from The Killer (1989). They derive their sense of the jianghu--that landscape of mountains and rivers that was the backdrop of ancient chivalry–not from lore or even martial-arts novels but from the violent underworld shown on TV screens.

Bin’s decline is portrayed as abandoning those ideals of righteousness and self-sacrifice flamboyantly dramatized in the movies. But Qiao clings to the imaginary jianghu to the end. She explains to him that everything she did was for their old code, but as for him: “You’re no longer in the jianghu. You wouldn’t understand.” You can respect his pragmatism and admire her tenacity, but he’s still a feeble figure, and she’s left running a seedy mahjongg joint–one much less glamorous than the club she swanned through at the film’s start. Appropriately for someone who got her idea of heroism from videos, we last see her as a speckled figure on a CCTV monitor.

From dailiness to darkness

Burning.

Often the crime in question is presented explicitly, but two films leave it to us to imagine what shadowy doings could have led to what we see. In Manta Ray, by Phuttiphong “Pom” Aroonpheng, we get the familiar motif of swapped identity. A Thai fisherman finds a wounded man in the forest and nurses him back to health. The victim is a mute Rohinga whom the fisherman names Thongchai. They share a home and the occasional dance and swim, even a DIY disco.

But who attacked Thongchai in the forest, and why? And what is the connection to the unearthly gunman who paces through the forest, bedecked in pulsating Christmas bulbs? And what makes the foliage teem with gems glowing in the murk? Somewhere, there has been a crime.

Manta Ray accumulates its impact gradually, with the scenes of the men’s routines giving way to mystery when the fisherman vanishes and Thongchai (named by the fisherman for a Thai pop singer) is trailed by a ninja-like figure clad in a red cagoule. A disappearance and a reappearance (of the fisherman’s wife) punctuate moody scenes of trees and sea. The opacity of the action makes a political point: offscreen, Thais brutally hunt down the refugee Rohingas. But the critique of anti-immigrant brutality is intensified by the lustrous cinematography (Aroonpheng was a top DP). You can feel the texture of the planks in the cabin and the sharp edges of the gems that fingers root out of the forest floor. This is probably the most tactile movie I saw at VIFF.

Then there was Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. Lee started his career strong and has stayed that way. The slowly paced, Kitanoesque gangster story Green Fish (1997) and Peppermint Candy (1999), with its reverse-order chronology, both achieved local popularity and established him as a fixture on the festival circuit. Oasis (2002), a daring romance of a disabled couple, won a special prize at Venice. Secret Sunshine (2007) brought Lee even more widespread fame. Like the episodes of Shock Waves, it dealt with the aftereffects of a horrific crime. Virtually everyone I know who saw the film remembers most vividly a particular scene: the heroine, having converted to Christianity and at last ready to forgive the perpetrator, visits him in prison. It’s one of the most nakedly blasphemous scenes I’ve ever seen, carried off with a shocking calm. Crime–this time, a gang rape–is also at the center of Poetry (2010), with another mother facing familial tragedy.

Most of these plots, particularly Poetry, are rather busy, but Burning is more stripped down (though not short). Lee Dong-su maintains the shabby family farm while his father is in jail awaiting trial. In town Dong-su meets Haemi, a former classmate now running sidewalk giveaways.

She lures him into her life by asking him to feed her cat while she’s in Africa, but before she leaves they start an affair. But he seldom breaks into a smile, favoring a puckered-lip passivity. After their coupling, we get his POV on a blank wall.

This turns out to be the first of many disquieting passages. Between bouts of tending livestock, feeding Haemi’s cat, and masturbating to her picture, Dong-su gets mysterious phone calls with no one on the line. He meets Haemi at the airport only to discover that she’s formed a friendship (or more?) with the suave Ben, whose gentle courtesy makes Dong-su feel an even bigger bumpkin. Soon the three are hanging out together, but at parties Dong-su can only stare at Ben’s yuppie friends. Dong-su, who wants to be a writer, is a fan of Faulkner, but Ben compares himself to the Great Gatsby.

After a long night of relaxing at the farm, with the men watching Haemi dance topless, she disappears. A black frame, a dream of a burning greenhouse, and Dong-su is left alone halfway through the movie. What happened to Haemi? And why does Ben say he enjoys torching greenhouses? Dong-su turns detective,

Lee is a master of pacing, and the deliberateness of the film delicately turns a romantic drama into a critique of entitled lifestyles and then into a psychological thriller. We are locked to Dong-su’s consciousness except for a couple of telltale shots of Ben calmly studying his rival from afar. We get Vertigo-like sequences of Dong-su trailing Ben and probing for clues and perhaps having more dreams. At the same time, Dong-su starts writing, as if Haemi’s disappearance has inspired him, but he finds more violent ways to release his simmering bewilderment.

After only one viewing, I didn’t find Burning as devastating a film as Secret Sunshine or Poetry, but I’d gladly watch it again and probably I’d see more in it. Lee manages to sustain over two and a half hours a plot centering on three, then two principal characters. He has earned the right to soberly take us into the mundane rhythm of a loner’s life and then shatter that through an encounter with two enigmatic figures who may be playing mind games. As with Manta Ray, we have to infer some of the action behind the scenes, but that just shows that in cinema, classic or modern, crime can pay.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Japadog, a Vancouver landmark.

More VIFF vitality, fancy and plain

I Wish.

DB here:

Back from Vancouver Internatonal Film Festival, we’re still assimilating. We just learned of the winners, but here are some more movies that won my admiration.

Three lives, four-plus hours

Art cinema has been attracted to mystery and intrigue plots since at least The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Antonioni needed an enigmatic disappearance to get L’Avventura going. Before and after there were Cronaca di un amore, La Commare Secca, Blow-Up, La Guerre est finie, and the works of Robbe-Grillet. Not to mention Vagabond and Toto les héros and, venturing to Asia, Chungking Express and Fallen Angels.

True to this tradition, in Dreileben (Three Lives, 2011), conventions of festival cinema—elliptical transitions, ambiguous dream sequences, retrospectively identified point-of-view shots, anecdotal realism, de-dramatization, open endings—punctuate, and puncture, a killer-on-the-loose scenario. The genre is respected to the extent of supplying teasing clues, some conveniently recorded on video and in an old photograph. (Shades of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.)

The murder-mystery element is, I think, part of the reason that this TV installment-story has been making the festival rounds. Yes, there’s also its pedigree (three accomplished directors) and its use of the now-common strategy of network narrative. Each of the three episodes focuses on different characters whose paths cross. We get pieces of the whole story; scenes glimpsed in one episode are fleshed out in another.

The tryptych format recalls the Belgian Trilogy (Lucas Belvaux, 2002). But that exercise retold its story by centering on a core of characters, replaying events and switching point of view (and genre) from film to film. Dreileben’s first two episodes focus on characters at some remove from the crime and the criminal, a strategy that redefines what counts as the central situation. Moreover, and unlike most network narratives, these plots show few points of contact. Characters connect very rarely across episodes, so that each tale gains a weight of its own. The mad-killer element comes to seem secondary for quite a while.

The first episode, Beats Being Dead, directed by Christian Petzold, is largely organized around the perspective of Johannes, a young medical student about to embark on a prestigious fellowship. He becomes attached to a moody immigrant woman working in a nearby hotel. Over the romance hovers not only a brutish biker club but also a mental patient, accused of murdering a girl, who escapes from Johannes’ hospital and lurks around the forest. This episode is presented in a clean, almost enameled visual style sharpened by the abrupt scene shifts characteristic of modern cinema.

The second part, Don’t Follow Me Around (Dominik Graf), seemed to me the strongest. Johanna, a female police psychologist, is brought to the town, apparently to profile the criminal, but actually to conduct a rather different investigation. She stays with an old friend and her husband, and Johanna’s visit opens up a new psychodrama all its own. The rather narrow focus of the first, on a romantic triangle, here widens to consider frayed friendships, marital suspicions, and old passions. The character relationships get more complicated as things move along. The somewhat informal framings and jerky cutting (nearly three times as many shots as in the Petzold, in about the same running time) accentuate Johanna’s discomfort and her eventual moments of confronting her past.

After two films hovering around the fringes of the crime, the third installment, One Minute of Darkness, signed by Christoph Hochhausler, seems to go to the heart of things. Now we follow the escaped lunatic Molesch pursued by Markus, a cop so flagrantly unhealthy that he seems to risk a coronary every time he rises from his sagging armchair. Yet this detective story turns out to be not quite as cut-and-dried as we expect. That’s partly because of Molesch’s encounter with a little girl and partly because the first episode is revealed in retrospect to unfold in a more indeterminate time frame than we might have thought. The film doesn’t plug every gap, I think; I left thinking we needed a fourth or fifth installment. But that’s probably part of the point.

Genre conventions permeate all three episodes, which seriatim present twentysomething romance, simmering melodrama, and classic sleuthing and pursuit, all spiced by stalker-in-the-shadows atmospherics. Dennis Lim’s illuminating essay indicates that this trio of films is the product of a German debate about how filmmakers committed to “auteur cinema” can deal with matters of genre.

More broadly, works like Dreileben characterize much of today’s festival moviemaking: an effort to graft modernist narrative strategies onto a genre-driven plot premise. (We see it in The Skin I Live in too.) A cynic could argue that a serial-killer investigation serves to attract audiences who might be put off by purely formal gymnastics. But actually mystery plots, based on hiding information and misdirecting our attention, mesh well with the narrational maneuvers of international art cinema. If crossover films like this bring in more viewers, that’s a side benefit of merging two robust traditions—a storytelling mode that hides and then reveals secrets, and one that believes that even when revealed, secrets remain secretive.

POV = Perplexities of Vision

Headshot.

The barely-converging fates of Dreileben reminded me of the network knitting of Johnnie To’s Life without Principle. In a similar way, two exercises in optical point-of-view echoed the last sequence of Panahi’s This is Not a Film. In that non-film, the camera abandoned by a cameraman seems to be picked up by Panahi himself and carried beyond what we normally think of as “house arrest.” But one of the resources of the POV shot is that it can coax us to ask who’s seeing what we see. If we aren’t given an identifying shot of the looker, we can start to wonder. Played upon in countless horror movies to hint at the eyes of the stalking monster/ killer, the unspecified POV in Panahi’s hands (or perhaps not in his hands) becomes charged with political consequence.

Optical POV isn’t as fully exploited as you might expect in Pan-ek Ratanaruang’s Headshot. One of its premises is that Tul, a contract killer, is wounded in the cranium and as a result sees the world upside down. But the trauma takes place in the first few scenes, and what follows until the midpoint is a set of flashbacks explaining how he became a gun for hire. Present-time episodes showing him getting adjusted to his affliction alternate with past-tense scenes that supply him with motives for revenge.

So far, so noirish. Indeed, the iconography (crooked lawyers, not one but two femmes fatales, chiaroscuro scenes) and the plot (flashbacks, voice-overs, double- and triple-crosses) put us in familiar, quite enjoyable territory. Needless to say, like nearly all film noir heroes Tul has never seen a film noir, so he can’t sense the walls closing in as quickly as we can. He remains idealistic—“I may kill people, but I’m not a crook”—and trusting to a fault.

The upside-down POV works okay as a general pointer to the film’s Buddhist thematics, but the inverted shots are fairly few, introduced to defamiliarize a bit of action. They aren’t exploited as a thoroughgoing formal device. For a while vision scientists believed, mistakenly, that when people wore inverting spectacles, they eventually learned to see the world rightside up. Is Ratanaruang suggesting that Tul adapted in this way?Early in the film the hero pins pictures on his wall upside down, but near the film’s end I thought I saw a shot ostensibly through Tul’s eyes showing us the inverted pictures on the wall, rather than the way they’d look if he saw upside down. In real life, as if it were relevant, it seems that wearing inverted spectacles doesn’t make you see things right way round eventually. The world always looks flipped. But you can adapt to this upside-down array fairly quickly and execute normal activities like riding a bicycle and even reading. Presumably this explains why Tul’s marksmanship remains lethally good in the gunplay finale.

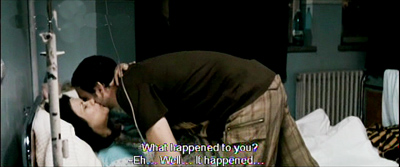

Far more consistent–obsessive, actually–is the play with optical POV in the Romanian film Best Intentions by Adrian Sitaru. When Alex’s mother has a stroke, he leaves Bucharest to visit her. She’s recovering reasonably well, but Alex becomes so anxious about her care that he makes life miserable for her, his father, his girlfriend Lia, and the doctor, an old family friend. After the first scene, when Alex gets the call about her stroke, a drastically totalizing POV system kicks in. Whenever Alex is in the presence of anyone else—major character, minor character, onlooker—we see him through that person’s eyes. If he’s alone, usually on the phone, the shots of him are unassigned and objective, but when he’s in public, he’s only shown subjectively. Moreover, we never get a POV shot from his perspective.

A narrational game emerges. When Alex is interacting with only one other person, we quickly grasp who the Unseen Seer is. For instance, we understand that he’s met at the train by his father, identified by his offscreen voice.

When Alex first visits his mother in the hospital, however, the POV floats momentarily. At first it might seem we’re seeing Alex’s entry through his mother’s eyes,when he briefly acknowledges the camera’s field of view.

But when he moves past, we realize we’re seeing him from the viewpoint of the woman in the bed beside his mother’s.

When he’s with only one other character, the scene plays out without cuts. When cuts come within a scene, they’re motivated as shifts from one character’s POV to another’s. Here we first see Alex and his mother through the eyes of the patient across the room, whom we glimpse in the background during his entrance above. When the mother’s neighbor looks at them, that motivates a closer view of them.

This tag-team POV becomes quite engaging when several characters are present. In a dazzling scene of three couples drinking around a tavern table, the dialogue is fast-moving and the cuts come quickly. I found myself trying to chart exactly whose view we’re getting. Sometimes the POV gets anchored retroactively: one of several characters we see in shot A becomes the POV vessel in shot B. For more fun, the system develops in unexpected ways as the movie proceeds.

The experiment is worthwhile, and not just as a formal game. Recall Erving Goffman’s notion that social life is a stage in which we enact the roles that put us in a good light. Best Intentions shows Alex as not only a caring son but a guy earnestly playing a caring son. In the Theatre of Everyday Life, he’s something of a drama queen. Of course he’s partly right to be concerned about the health-care system (he’s probably seen The Death of Mr. Lazarescu), but that concern also handily motivates his incessant performance of his part.

As a result of Sitaru’s rigorous formal constraints, Alex is onscreen for nearly every instant of this 101-minute movie. (The very brief exception is itself of interest.) His narcissism, his urge to control others, and his inability to really listen to his family and friends—all are perfectly captured by a stylistic strategy that constantly gives him center stage. I haven’t seen Sitaru’s previous film Hooked (2007), but that too used an enveloping POV strategy. Interestingly, there he assigned all three major characters optical POV shots. In Best Intentions, denying Alex his own POV underscores his fretful obliviousness to what anyone else thinks. He makes a scene in every scene, becoming an object of fascination and frustration, for others and for us.

Calming down

All these films, as well as others we’ve discussed in this year’s VIFF, might seem to support the idea that Form Is the New Content. It takes a film like Hirokazu Kore-eda’s I Wish to remind you of the power of less convoluted storytelling. Like Still Walking, it’s a family drama-comedy, but a little more somber and a little more comic. Devastatingly simple, too.

A family has split up. One brother, Koichi, stays with his mother and grandparents in Kagoshima, where the volcano splutters ashes into the air. The younger brother, toothily grinning Ryu, has gone off to Fukuoka with father, a scruffy rock guitarist. The boys communicate by phone, hoping to reunite the family.

They hatch a plan. They’ve convinced themselves that if they make a wish at the precise moment that two bullet trains pass one another, that wish will be granted. So Koichi and Ryu plan a pilgrimage that eventually encompasses their pals and that becomes a confrontation with the mundane realities of death and solitude, mitigated by comradeship and the hospitality of strangers.

The boys’ situation ripples outward to encompass the grandparents’ friends and the sons’ schoolmates and their parents, all of whom earn quietly incisive vignettes. Routines—classroom encounters, swimming sessions, Koichi’s run-ins with teachers, Ryu’s nights out with dad’s band—are recycled without fuss, building up a textured sense of each boy’s world. Kore-eda presents everything so unemphatically that he makes film direction look very easy.

Despite lacking the fanciness of the modern network narrative and its disjunctive time schemes and viewpoint switches, Kore-eda’s plot, like that of Ozu’s Early Summer, effortlessly creates a ramifying world in which our boys feel at once comfortable and apprehensive. Come to think of it, some of the kid comedy recalls the two brothers’ antics of I Was Born But, and the surprisingly sympathetic young teachers, reminiscent of the adults in Ohayo, become co-conspirators and, a little bit, surrogate parents. I Wish is a modest movie; it almost lowers its eyes in front of you. It’s also the closest thing to perfection that I saw in Vancouver.

For a lively roundup of ideas on Dreileben, see David Hudson’s Daily MUBI entry. An informative presskit is here. Headshot has been bought for US release by Kino Lorber. An informative interview with Adrian Sitaru is here. I discuss arthouse genre crossovers in an earlier year’s entry from VIFF. For a more thorough study of network narratives, see “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance” in my Poetics of Cinema.

23 October 2011: Thanks to Christoph Huber for correcting an error in the initial post. Although there is a town called Dreileben, the film doesn’t take place there, as I had said.

I Wish.

Wantons and wontons

Oxhide II.

DB here, with more from the Vancouver film fest:

Two of the more innovative films I saw evoked film history—one explicitly, the other obliquely. Raya Martin’s Independencia is part of a planned series devoted to the history of the Philippines, told from the bottom up. In this first installment, villagers flee into the jungle to hide from the American “liberation” of their islands. The film centers on a mother and son who, joined by a woman the son finds, create a new family. After years, the son and the woman have a child, but their new life is threatened by the encroachment of the invaders.

What sets Independencia apart is Martin’s effort to create the look and feel of a 1930s fiction feature. He shot the movie wholly in a studio, and the evidently faked backdrops are counterbalanced by gorgeously controlled lighting effects, and even dashes of color. Since virtually no Filipino films survive from this period, Martin gives us less a pastiche than a possibility, a sort of hypothetical archival film. The fact that the film makes aggressive use of Dolby sound, especially during a tremendous storm sequence, only adds to the sense of history being reimagined for today.

More traditional, at first glance, is Puccini and the Girl, a historical drama by Paolo Benenuti and Paolo Baroni. Facts of the case: In 1909, a maid in Puccini’s Tuscan villa, accused of being his concubine, committed suicide. But an autopsy revealed that she was a virgin.

The film’s reconstruction of what happened behind the scenes, tracing the veins of jealousy and deceit running through the household, relies on recent research into the tragedy.

At the same time, we have an homage to silent cinema. In most scenes we hear no dialogue: actors whisper at a distance from us, or simply conduct themselves without speaking. What words we do hear are recited pro forma (the Mass) or sung (in a waterside tavern, or in nondiegetic accompaniment). There is only one line of conversation, and that is given greater saliency by being a cry from the heart.

So we’re largely confronted with a silent film, accompanied by music and sound effects. To add to the estranging effect, characters communicate chiefly through letters and telegrams—exactly as in the films of the period. We hear the letters’ text read aloud, but the sense of stately compositions propelled by written commentary, distinctive features of 1910s cinema, remains. An unwitting homage, perhaps, but one that pleased this fan of classic tableau cinema.

Independencia was part of the Dragons and Tigers thread, one of the hallmarks of the Vancouver event. Year after year it gives an unequaled view of current Asian cinema. This year’s program, assembled by Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, was at least as fine as ever. Eight films compete for the $10,000 prize given to first or second features. The winning film, Eighteen by Jang Kun-jae, centered on the familiar situation of teenage lovers separated by parents and school pressures. I didn’t see all the competitors, but my own favorite was Chris Chong’s Karaoke, a Malaysian story of a young man coming to terms with his mother’s decision to sell her karaoke bar. The first ten minutes are quite creative, disorienting the audience through complicated sound mixing, while the boy’s community, devoted to the production of palm oil, is presented with a documentary directness.

Outside the competition, I saw several Asian films of consequence. I’ve already discussed Yang Heng’s Sun Spots and Bong Joon-ho’s Mother. Ho Yuhang’s At the End of Daybreak marks a shift from his lyrical first feature, Rain Dogs, which I reviewed at Vancouver in 2006. A plot situation close to that of Eighteen is treated in much darker tones. A young man falls in love with a high-school girl, but he’s driven to murder by her growing indifference to him. The familiar elements of furtive sex, drinking parties, and demands from the girl’s family for reparations are given a noirish treatent. Ho’s admiration for American crime novels shows in his increasingly bleak handling of the affair. Here the femme fatale is a high-school girl, and the entrapped male’s revenge is complicated by an unexpected erection.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Bong Joon-ho has been something of a leitmotif on this site lately, with my comments on Influenza and Mother. Under the rubric “Bong Joon-Ho & Co.,” Dragons and Tigers screened a collection of shorts paying tribute to the Korean Academy of Film Arts. Most were from the 2000s, but Kim Eui-suk’s Chang-soo Gets the Job, dated from 1984. Focusing on a gang of teenage purse snatchers, Kim’s film was a little rough technically, but it built its story deftly. The quality of the rest was quite strong, with the grisly and wacky Anatomy Class (2000, Zung So-yun) being a high point. Meanwhile, Bong’s Incoherence (1994) shows that his urge to deflate official hypocrisy, seen in Memories of Murder and The Host, was already present in his student days.

My admiration for Hirokazu Kore-eda runs high, as I indicated in my discussion of Still Walking at last year’s VIFF. But Air Doll, while full of vagrant pleasures, left me unsatisfied. The Kafkaesque premise, derived from a manga, is that an inflatable saucy-French-maid dolly comes to life, endowed with speech and movement but retaining her seams and air valve (both of which will figure in the plot). Her sad-sack owner doesn’t notice the transformation, but while he’s at work, she takes a job at a video store and wanders the city.

The aim, I think, is to defamiliarize ordinary city life by seeing it through Nazomi’s eyes. The fact that a sex effigy is the most innocent character in the movie is part of the point. Makeup, money, and fashion start to seem extensions of sad, solitary eroticism, and the line between mainstream movies and porn gets blurred. But all the thematic elements didn’t blend very well, and at moments, as during the music montages showing people’s desperate loneliness, I worried that for once Kore-eda had slipped into conventional sentimentality. The tone also shifts, with a climax that revises the big scene of In the Realm of the Senses. Kore-eda deserves credit for his unflagging effort to try something fresh with every project, but here, it seemed to me, that the film was defeated by an overcute conceit and underdeveloped execution.

The most exciting Asian film I saw at VIFF was Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide II. Her first feature, Oxhide, was screened at Vancouver in 2005. (Full disclosure: I was on the jury that awarded that film the D & T prize.) This one seemed to me even better.

To say that this 132-minute film is about a family making dumplings is accurate but misleading. To add that the action consumes only nine shots makes it sound like an arid exercise. In fact, it’s a consistently warm, engaging—I don’t hesitate to say entertaining—film that is also a demonstration of how a simple form, patiently pursued, can yield unpredictable rewards.

In the first Oxhide, we saw the comedy and tensions of Liu’s life with her parents, who run a leatherwork shop. By the time she shot part two, they had already lost their business, but the sequel presupposes that the shop is still going, albeit coming to a critical point. So there’s a quasi-documentary aspect, as the family’s financial strains, discussed cryptically at various points, hover over the mundane process of wonton cookery. Yet although everything looks spontaneous, it was all completely staged—written out in detail, rehearsed over months, reworked in test footage, and eventually played out in “real time.”

And in real space. The first shot, which consumes twenty minutes, shows Liu’s father pummeling a hide in his vise and eventually clearing the table for serious food preparation.

Actually, the film’s subject is that table. On its surface, a meal is prepared; around it, the family gathers; we even see what happens underneath. We watch father and mother chop scallions, mince pork, twist and yank dough, pinch the dumpling wrappers around the filling. We watch the daughter try to match her parents’ dexterity. This is a movie about housework as handiwork, and family routines and frictions.

For minutes on end, we see only hands and arms; Liu’s 2.35 frame often chops off faces. Liu employed a construction-paper mask to create the CinemaScope format within HD video. Why the wide frame? Most filmmakers use it for expansive spectacle, she remarks; but “I wanted to see less.” And the horizontal stretch further emphasizes the table.

As if this weren’t rigorous enough, Liu has filmed the table from a strictly patterned arc of camera positions, dividing the space into 45-degree segments. These unfold in a clockwise sequence around the table. What could seem an arbitrary structural gimmick is justified by the fact that each setup proves ideally suited to each stage of the process. When father and mother team up to start the meal, the angle gives us two centers of interest. And Liu feels free to “spoil” her mathematical structure by varying the height and angle of her camera. Plates, bowls, and an articulated lamp become massive outcroppings in this micro-landscape.

Oxhide II is unpretentiously inventive, quietly virtuosic. Evidently it took a Chinese filmmaker (whose day job is writing TV dramas) to blend domestic life with the rigor of Structural Film. Liu displays the fine-grained resources yielded by several cinema techniques, from framing and staging to lighting and sound. The finished dumplings get constantly rearranged on the cutting board. Each family member has a different technique for pulling off bits of dough, and each gesture yields its own distinctive snap.

I had to think, almost with pity, of all those US indie filmmakers who believe they have to cultivate CGI and slacker acting, to seduce investors and strain for outrageous sex and edgy violence. Liu made this no-budget, low-key masterpiece over years in a single room, and with her parents. That’s a new definition of cool.

Liu promises us another installment. In the meantime, every festival that’s serious about the art of cinema should pledge to show Oxhide II.

Puccini and the Girl.

PS 12 October: Thanks to Matthew Flanagan for correcting an embarrassing typo.

PS 15 October: Thanks to Ben Slater for correcting yet another one!

Angles and perceptions; with a note on Thai censorship

Hide your face

“Angles alter perceptions,” notes a recent Newsweek story. You bet, as we say in Wisconsin. But intriguing evidence emerges from new research into videotaped confessions.

Over 500 jurisdictions now record confessions on video, we’re told. In virtually all instances, there’s only one camera, and it shows only the accused. That means, in movie terms, there are no reverse shots of the questioner.

What difference does it make? Quite a lot, it seems.

In Newsweek‘s words, “When a camera shows only a suspect’s face, studies show, potential jurors are more likely to believe the confession was voluntary and the suspect guilty than when it shows the faces of both suspect and interrogator.” The problem may also infect judges. Experiments conducted by G. Daniel Lassiter at Ohio University found that a sample of 21 judges appraised the confessions as more voluntary when the camera framed only the confessor and didn’t show the police officer.

The obvious worry is that we can’t be sure that the confession is voluntary if we don’t get any sight of the questioner. To take an extreme, but not fanciful, possibility, maybe the person offscreen is holding a weapon. But even if the questioner isn’t threatening the confessor, his or her facial expression will help us appraise the whole situation more fully. Is s/he reacting with sympathy, anger, or neutrality? Do the questioner’s facial expressions set a context for the questions asked? We can’t know, and this absence of knowledge may encourage us, by default, to side with authority and presume that the confession is genuine.

In fiction films, sometimes the camera doesn’t give us the reverse angle. It may simply dwell on one character, often when she or he is delivering a monologue. A close analog to the videotaped confession occurs in Truffaut’s 400 Blows when an offscreen therapist questions the boy Antoine about his life.

Several effects flow from Truffaut’s choice of this technique. The handling suggests a quasi-documentary objectivity in recording Antoine’s replies. Making the questioner unseen suggests that she won’t become a significant character, rather a voice that typifies the impersonal authority of the detention facility. The fact that the questioner is a woman reminds us of Antoine’s relation to his mother, an important topic in the interview. In all, this strategy concentrates on Antoine, letting us see new sides of his past and his mind.

In other scenes, I’ve noticed that suppressing the reverse angle not only showcased the character we see but also rendered the scene’s action more suspenseful or ambiguous. Recall the famous first shot of The Godfather, which concentrates on the mortician and refuses to supply the reactions of Don Vito.

The shot gives full sway to Bonasera’s monologue. At the same time, by slowly zooming back, the shot creates a growing suspense. To whom is he speaking? What is the listener’s reaction? Only at the end of Bonasera’s plea, when he rises to whisper in Vito’s ear, does Coppola supply the view of Don Vito—a big theatrical entrance for this character and the actor playing him.

Less operatic is an early scene in Sauvage Innocence (2001), by Philippe Garrel. The filmmaker François is going over his dead wife’s belongings, which his friend has preserved. Garrel gives us an establishing shot of the action, then, as the friend continues to talk, the camera concentrates on Francois’s reaction to the letters, poems, and photographs. Although his expressions are somewhat ambivalent, at least we can see them.

But in the next scene, a single shot lasting about seventy-five seconds, Garrel withholds the reverse angles that we’d normally get when his protagonist speaks. The camera favors the friend, a minor character, who asks questions about François’s new film while feeding a baby. François replies that he’s having trouble finding a producer, and if this last opportunity fails, the project will be over.

Garrel doesn’t choose to reveal François’s expression as he reports this critical state of affairs: no reverse shots. We must infer his emotional state from his voice, his pauses and sighs, and his postures as he replies, rises, and sits down.

At most we can assume that he’s dispirited, perhaps because of his film’s slim prospects and the reminder of his dead wife.

In the scene, there’s one glimpse of his face, as he turns slightly, and—Tim Smith might be able to confirm this—I’d bet that most viewers zero in on him at that moment. (The movement is centered in the frame as well.) But that view is pretty brief and uninformative.

Overall, we have to infer François’s attitude from other cues than his expressions, and the results aren’t clear-cut. It seems to me that Garrel’s choices here are typical of one strain of “art cinema.” This storytelling tradition aims to make scenes somewhat indefinite in their meaning and to leave considerable room for spectators to play with various implications of the action.

Cutting and Social Intelligence

Some years ago I developed some ideas about the importance of shot/ reverse shot cutting in an essay called “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision.” (1)

One school of thought in film studies holds that cinematic conventions are wholly arbitrary social constructions. This implies that we have to learn to watch movies, just as we have to learn any arbitrary sign system, like Morse code or written languages. My essay argued that cinema, like painting, offers a continuum of conventions: some require a lot of exposure to learn, while others require much less. The easiest ones rely on regularities of everyday experience. I tried to show that shot/ reverse shot is a fairly easy convention to learn because it mimics the alternation between speaker and listener that we find in the turn-taking of ordinary conversation.

As my examples suggest, even if person A is doing all the talking, we don’t fully understand the scene if we can’t also monitor the reactions of B. By contrast, the shot/ reverse-shot patern keeps a running tab of the dynamics of the conversation. When a director wants to suppress information about B’s response, deleting the reaction shot can create uncertainty or suspense.

Confessions aren’t fictional films; we don’t assume that they use much staging. I’d argue that in videotaped interrogations any uncertainty about the listener’s reactions is quelled by our assumption that the officer is neutral or that any emotion she expresses has no effect on the confession. In other words, during a videotaped confession, any reaction on the part of B is presumed, perhaps wrongly, to be irrelevant. But in watching a fiction film, we tacitly assume that the director has suppressed B’s reaction in order to shape our experience in a particular way. The use of shot/ reverse shot, then, has a narrational function, governing the flow of story information.

We might posit this maxim of social intelligence: We understand an interchange more fully when we can see both participants’ responses to it, moment by moment. This notion underpins our old friend shot/ reverse shot, a convention that requires no specialized learning beyond watching and participating in conversations in real life. The absence of the reverse shot in videotaped confessions forces us to fill in one side of the conversation, and what we fill in may not be warranted.

Lassiter suggests a subtler effect of single-shot confessions. He has specialized in what psychologists call “illusory causation,” as explained in a 2002 press piece.

Criminal interrogations are customarily videotaped with the camera lens zeroed in on the suspect. Psychological research has shown that objects that are the focus of attention, are “more likely than less conspicuous objects to be judged the originators of a physical event, even when there is no objective basis for such a conclusion,” said G. Daniel Lassiter, author of the study. This phenomenon is referred to as “illusory causation.”

So by concentrating wholly on the suspect, the framing attributes a greater causal power to him or her than would a shot/ reverse-shot sequence.

I can’t at the moment see how this might come into play in a fiction film. In both of my major examples here, Bonasera and the baby-feeding friend have less causal power than the character whose response is suppressed. I suspect that the story context of film scenes provides our main sense of who has the causal power, which film style can reiterate or undercut.

Censoring Syndromes

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Syndromes and a Century was one of the best new films I saw last year. It has played at Venice, Vancouver (my quick remarks are here), Hong Kong, and other major festivals. It also won the best editing award at the Asian Film Awards. You can read the Variety review here. Jeff Reichert’s exhilarating appreciation appears, in keeping with the theme of the above entry, at Reverse Shot.

But now Apichatpong has withdrawn the film from theatres because local censors have demanded cuts. The objectionable portions include shots of monks playing with toys and a doctor kissing his girlfriend in a hospital. Details are available at Variety and Limitless Cinema. According to Screen Daily (not available free online):

Apichatpong questions why many other Thai and foreign films which contain excessive violence, nudity, coarse language, crude jokes on other ethnic groups, and monks doing stupid things did not suffer the same fate.

Below I reprint Apichatpong’s most recent statement and information about a petition that’s available online.

Free Thai Cinema Movement Petition

Statement by Apichatpong Weerasethakul with Bioscope, the Thai Film Foundation, Thai Film Director’s

Association, and Alliances.

I am saddened by what has happened to my film. However, this is not the venue to try to make SYNDROMES AND A CENTURY shown in Thai theaters. It is not my intention to use this opportunity to promote my work.

But, it is time to seriously think about what is going on with our censorship laws, so that the next generation of filmmakers will not face the same problems as us, and so that the Thai audiences can truly achieve a freedom of choice.

It is time we discuss whether all films, before being released, should be seen by the Buddhist council, doctors council, teachers council, labor council, the army, pet lovers group, taxi union, representatives from other foreign countries etc? Or, is it easier to turn our nation into a Fascist state so that we can live in harmony and don¹t have to waste time talking about democracy?

The system of the Thai Board of Censors needs to be evaluated. Their members’ relevancy and efficiency needs to be questioned, and we should decide whether the laws should be changed.

I would like to ask you to reflect on the censorship practices in our country and to provide us with advice at

http://www.petitiononline.com/nocut/petition.html

Later on, this Petition will be submitted to the Thai government. Your support will be a great contribution to our fight for one of our most basic rights – that of freedom.

I am grateful for your time and your participation. Thank you very much.

Warmest Regards,

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

KICK THE MACHINE FILMS Co., Ltd.

(1) It’s not available online; it was published in Post-Theory and will be reprinted in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema collection.