Archive for the 'Fans and fandom' Category

Little things

Equinox Flower (Ozu, 1958).

DB here:

Academic critics and fans share a passion for looking closely at the movies we admire. A lot of film critics enjoy spiraling out from the film to ponder Big Ideas, which is okay, I guess. But I confess I particularly enjoy digging in for trouvailles (great word), lucky discoveries that passed me by on earlier encounters.

Across my career, many of the directors I admire seem to have tucked in little things just for me (or you). They don’t necessarily carry meanings; they’re quietly decorative, subtly off-center to the narrative. Tati slipped peculiar items into the corners of the frame. Sturges offered gags that only people with his sense of humor will find funny. A successful crowdsourcing enterprise exposed Welles’ homages to early film. Above all, Ozu nudged me toward red teakettles and surprising details. Who else lines up the levels of beverages in a table setting, and then matches that plane to the edge of a fruit bowl?

If you care enough about my movie, the director seems to say, I’ll reward you with a trouvaille. Here are two I found recently.

Showing the stitches

Sometimes a trouvaille is a felicity of craft. The director quietly shows off his virtuosity to those in the know. While studying Pulp Fiction for a book I’m finishing, I noticed that Tarantino sets up the ending in a sidelong way.

You’ll remember that the opening shows Honey Bunny and Pumpkin discussing how a restaurant is one of the safest robbery targets. Abruptly they launch an assault on the diner. Then they drop out of the film for a couple of hours.

Very likely we’ve forgotten about them when Jules and Vincent settle down for breakfast in a diner. After discussing the virtues of pork products and the prospects for Jules’ future, Vincent rises to go to the toilet. As he pauses, it’s possible, but not easy, to discern the larcenous couple out of focus in their booth behind him. Given their peripheral status and the centrality of Travolta’s performance, I suspect that almost no one notices them on a first viewing.

Soon after Vincent has left, we’ll hear a repetition of the final bits of the couple’s conversation and we’ll see a replay of their leaping up to announce the robbery. Tarantino has rewarded the sharp-eyed viewer with a slight anticipation of the replay, and a hint at how his film will fold back on its opening sequence.

But this echo is matched by a “pre-echo” during the opening sequence. As Pumpkin and Honey Bunny plan their heist, a close view of her includes a bulky man in a t-shirt walking into the distance.

At this point, a first-time viewer hasn’t been introduced to Vincent, so the t-shirt guy is just part of the scenery. Only in retrospect do we realize that here Tarantino is anticipating, and overlapping, the portion of the robbery that we’ll see in the final moments of the film.

Here the critic/fan is invited to appreciate how carefully made the film is. It’s a quality we don’t sufficiently recognize in Tarantino: a delight in fine-grained formal niceties.

Easter Egg, avant la lettre

In Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1950), tennis pro Guy Haines is introduced (implausibly) reading a book on his trip. Soon he’s accosted by the spoiled, marginally nuts Bruno Anthony, and the plot gets under way. Only a fan, or a critic, will want to know: What’s Guy reading?

It’s not easy to tell. We don’t get a close-up of the book. The best we can tell, from above, is that it’s a hardcover, with a photo on the back of the dust jacket. Later, after Guy and Bruno have shared a meal in a compartment, we can glimpse the spine.

Blown up, thanks to the glory of Blu-ray, the spine looks like this.

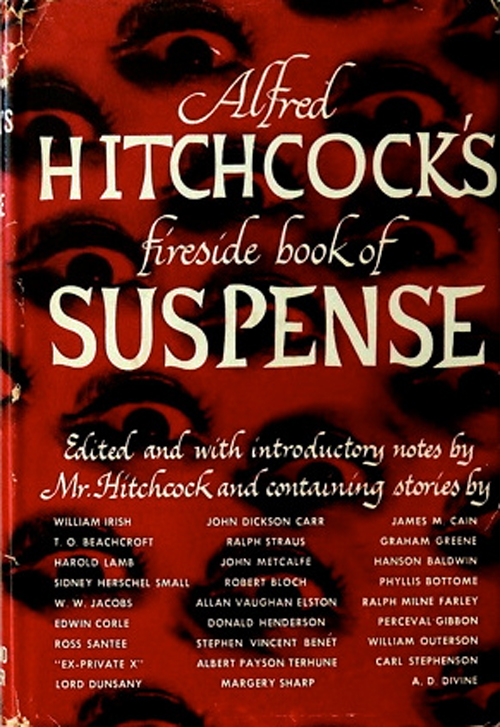

A little research reveals that the volume is Hitchcock’s collection of stories published in 1947 by Simon and Schuster.

Several anthologies were published under Hitchcock’s name from the 1940s onward, but most were in paperback. This was a more prestigious item, and I suspect it helped the branding effort that was underway during his Hollywood career. The picture on the back is of Hitchcock, of course. (My copy lacks a dust jacket, so I can’t supply that.) But the resonance comes from the fact that I was reading this very book as part of preparation for my own study of 1940s mystery culture.

It’s not exactly product placement; the book’s presence is too fleeting to register with audiences, surely. Including the book seems more in the nature of a private joke among Hitch and his team. Guy is a man of good taste, reading a book by the man directing the film he’s in.

Today we’re familiar with Easter Eggs, those bonus materials that establish a complicity between filmmmaker and viewer. Is this an early example? It could be a prize for fan connoisseurship. The book isn’t emphasized, being buried in the mise-en-scene, and so it encourages the devout to poke and probe. It also points outside the film to the production context. Still, how many 1950 viewers, lacking our ability to freeze and magnify the frame, could have spotted it? Perhaps only the devotion of a modern fan, aided by new technology, can bring this trouvaille to light. An incipient Easter Egg, then, awaiting digital technology to be discovered?

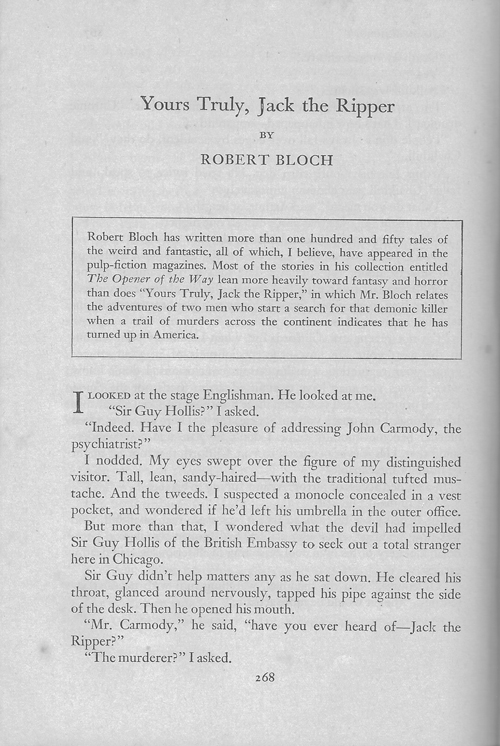

Once we’re down this rabbit hole, let’s scramble further. What stories might Guy be reading? There are two hints. We have the placement of the jacket flap in the shot above, and an earlier shot showing the book open.

As best I can tell, the story Guy’s reading is likely to be “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.” It tells of a psychiatrist who meets an Englishman called “Guy Hollis.” Sir Guy believes that Jack the Ripper has migrated to the US and is at large in Chicago. With the aid of the psychiatrist, Sir Guy finds him. Apart from the name Guy, the correspondence to Strangers it would seem to involve a peculiar bond between two men, one of whom is a psychopathic killer.

But there’s another, stranger affinity.

The author of “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” is Robert Bloch., whose novel Psycho would furnish Sir Alfred his 1960 film. Coincidence? In the land of trouvailles, are there any coincidences?

Fans have raked over these movies assiduously, so I can’t imagine I’m the first to notice these fine touches. No matter. When you discover them on your own, you still feel a tiny thrill of communicating with the filmmaker, behind the backs of all those folks who didn’t notice. Ozu, I often feel, is making movies especially addressed to me. It’s an illusion, of course, but I refuse to give it up.

Thanks to the University of Wisconsin–Madison Filmies listserv for helping me understand what counts as Easter Eggs, and for a reality check on my sanity.

This site includes lots more on Hitchcock, Ozu, Sturges, and Tarantino. My book on Ozu is available from the University of Michigan. It takes time to download, so be patient.

P.S. 15 August 2021: As I thought, I’m not the first. A mere twenty-one years ago, Dana Polan in his monograph on Pulp Fiction (British Film Institute) noticed the pre-echo of Vincent headed toward the toilet. Good going, Dana! Film analysis wins again.

Days of Youth (Ozu, 1929).

When media become manageable: Streaming, film research, and the Celestial Multiplex

Never coming to the Celestial Multiplex: Liberty Belles (Del Henderson, 1916).

DB here:

A directors’ roundtable in The Hollywood Reporter says a lot in a little.

Fernando Meirelles: This June, The Two Popes was in 35 festivals. Then we were going to have two or three weeks of theaters. And then the [Netflix] platform. I mean, it couldn’t be better.

Martin Scorsese: We are in more than an evolution. We are in a revolution of communication and cinema or movies or whatever you want to call it.

Meirelles casually omits DVDs, at one point the most rapidly adopted format of consumer media. Yeah, what ever happened to discs? And in what follows, I’ll take issue with Scorsese’s claim that streaming has triggered a revolution. It’s more a case of evolution that issued in a sweeping change, like Engels’ transformation of quantity into quality, or Hemingway’s claim that he went broke slowly, then quickly.

More important, I’ll try to assess the impact streaming has had on what Kristin and I and other researchers and teachers try to do–study film as an art form in its historical dimensions.

Managing your time, and your movies

If we’re looking for a revolutionary turning point, I’d suggest the moment that movies no longer became appointment viewing. When they played theaters you had limited access. The film was there for only a while (even The Sound of Music eventually left) and you had to watch it at specified times. On broadcast TV and cable, the same conditions applied. But with the arrival of consumer home videotape in the 1970s, the viewer was given greater control.

Akio Morita of Sony called it “time-shifting.” The phrase, shrewdly positioned as a defense of off-air copying, captures a fundamental appeal of physical media. You could watch a film at home, and whenever you wanted to. Yes, VHS and even Beta yielded shabby images and even worse sound, but (a) theatres were often not much better, and (b) a video rental was cheaper than a movie ticket. Most important was a general rule of media technology: For the mass market, convenience trumps quality.

Videotape swept the world in the 1980s and gave films an aftermarket. Many an indie filmmaker could get financing for a project on anticipated tape sales. The laserdisc gained some attention in the 1990s, becoming a sort of transitional format. It improved quality (better analog picture, digital sound) but had drawbacks too. A movie wouldn’t fit on a single disc side, and a laserdisc was pricier than tape. LD remained a niche format, chiefly for educators and home-theatre enthusiasts.

The laserdisc was superseded by the DVD, introduced in 1996. Journalists claimed that it enjoyed the fastest consumer takeup in electronics history. Discs were more convenient than tapes, and proof of concept had been provided by the success of CDs for music. To compete, cable companies introduced “video on demand,” a time-shifting compromise between scheduled cable delivery and rental of tape or disc. People still use cable VOD, and for some purposes it’s a cheaper alternative to committing to subscription services.

Reviewing The Irishman, a critic suggested that most people will skip seeing it in theatres and watch it on Netflix, where it’s “more manageable.” With tape and disc, either analog or digital, consumers became accustomed to a huge degree of manageability. They could pause, skip ahead or skip back, race fast-forward or –back, play slowly, and above all play the movie over and over. DVDs made all these options quicker and more convenient than tape had. The market boomed. Video stores made discs available for rental, as tapes had been, and retail stores offered them for sale, at increasingly low prices.

But there were problems. In the 2000s there was a glut of DVDs, and consumers began to realize that a few weeks after release many titles would end up in the bargain racks. A brisk secondary market developed thanks to the US “first sale” doctrine, most virtuosically exploited by Redbox. Worse, there was piracy. Pirating analog tapes degraded quality across generations, but with digital discs you could rip perfect clones. Any teenager could hack past region coding and anticopying software.

The Blu-ray disc was an improvement on the first-generation DVDs, and it came along as more people were buying widescreen and high-definition home monitors. Properly mastered, Blu-ray discs looked good, and they had bigger storage capacity. Some consumers got excited, but the improved format couldn’t arrest the headlong decline of disc sales. In addition, the industry’s rationale for Blu-ray was its resistance to rippng, but hackers breached the codes with ludicrous speed.

From this angle, streaming is parallel to digital theatre projection : a new phase in the war against piracy. Likewise, as in theatrical screenings, you’re paying for an experience, not an item. You’re not buying an object you can copy or resell. If a movie is available only on streaming, you’re renting something, not owning it legally. One aspect of manageability—personally possessing a movie—is traded away for convenience and, ultimately, for limited access, as I’ll try to show.

Not so gently down the stream

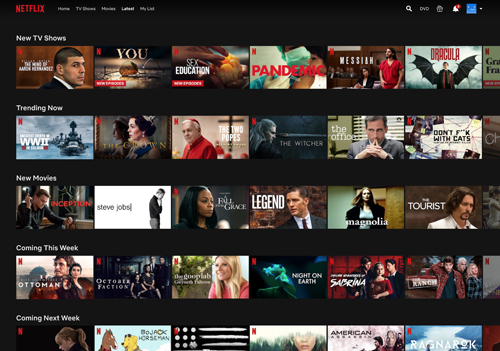

With streaming, the age of appointment viewing seems more or less over. And the infinite vista of the Internet has encouraged tech-heads to imagine something like the Celestial Jukebox, a vast virtual multiplex in which all movies will be available. If iTunes and Spotify did something like this for music, why not cinema?

Let’s consider the pluses and minuses of streaming for ordinary consumers and for filmmakers.

Obviously, there’s convenience. After the monstrous tape cassettes, DVDs looked adorably slim. Now, gathering in slippery stacks, they have their own sinister aura. With streaming, there’s no need to run out to the video store or to buy new shelving to support a bulging library of discs.

There’s also price, compared to either theater tickets or cable fees. From $6.99 per month (Disney+) to $12.99 (Netflix), streaming services promise to provide TV and movies quite cheaply. And there’s the range of choice, which even on second-tier streamers exceeds the capacity of most towns’ video stores back in the day. Finally, there are many obscure films lurking in the corners of most streamers, so the joy of discovery is still there to a degree.

On the minus side, there’s one that gets the most press—the further erosion of “the theatrical experience.” Critics emphasize the pleasures that come from being in an audience, but this always seems to me overrated. More valuable to me are the scale of image and sound you get in a theatre. I like my movies to loom.

Above all, there’s a virtue in the lack of manageability. In the theatre you can’t pause the movie or run back or skip ahead. You can close your eyes, look away, or leave, but at bottom you’re there to turn your sensorium over to the filmmaker, to go through an experience you don’t control. This unshakeable grip on your attention yields some of cinema’s most powerful effects.

The condition of privatized viewing isn’t unique to streaming, of course. Nor is another drawback, that of the cyclical expiration and refreshing of “content” on streaming platforms. Admittedly, we’re warned. Newspapers and websites run alerts notifying us when a title is leaving a service—perhaps for a little while, perhaps longer, perhaps forever. And this situation is a bit like DVDs’ going out of print. But at least some disc copies exist to be sold second-hand or cloned as files. In working on my book on the 1940s, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that I could track down arcane titles on out-of-print discs, and at fair prices. When something not on disc leaves streaming, how do you access it?

I think there will be some pushback when subscribers learn about the costs that more and more services are tacking on. Yes, with Amazon Prime for $119 per year you get access to many films, along with other services. But for a great many films Amazon demands an extra rental fee and very short-term access. Within Amazon, there are channels (Britbox, HBO Now, Starz, Cinemax et al.), all of which demand further subscription payments. As people start to realize that streamers will have exclusive licenses for titles, they’ll feel pressure to subscribe to many services. Here, as elsewhere, the total streaming price tag starts to look like cable fees. Even the New York Times has noticed.

Another problem won’t bother most consumers, but it does matter. A streamed title will occasionally be in an incorrect aspect ratio. Most commonly, a Scope (2.39 or so) image will be cropped to 1.85. I noted this some years back, relying on a website showing faulty Netflix transfers, but that site seems to have been taken over by … Netflix itself.

Netflix will say, with all “content providers,” that they get the best material they can from their licensors. I don’t watch streaming enough to know how common wrong aspect ratios are, but if you know of examples, I’d like to hear.

Finally, even streaming companies can collapse. Unless Apple buys a studio (Lionsgate? MGM? Columbia?), it must rely on original content, and it could well flop. On the day I’m writing this, one hedge fund manager predicts we have reached peak Netflix. Given greater competition, slower growth, and accelerating cancellations, he maintains that Netflix is on the wane. If it scales back or fails (it currently carries $12.43 billion in debt), what will happen to its licensed material and its original content?

What about creators? Filmmakers, especially screenwriters, have enjoyed boom times. It may be a bubble, with over 500 scripted series available on broadcast, cable, and streaming. Still, it has given everyone a lot of opportunities. Documentary filmmaking in particular has enjoyed a shot in the arm.

And features are still doing quite well, at least on Netflix. Of the streamer’s top 10 releases in 2019, seven were features. But those proportions may change. Aside from big theatrical movies licensed from the studios, the impact of proprietary “event” programming (War Machine, Bird Box) has been fairly ephemeral. (Obviously Roma and The Irishman are exceptions.) The strength of streaming, it seems to me, is the same thing that sustained broadcast TV: serial narratives. Hence the popularity of Friends and The Office, as well as House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black.

Like network TV, a streamer needs a reliable, constant flow of content—not only many shows, but many episodes. The model of the series, if only in six or eight parts, secures the loyalty of the viewer for the long term. Even if all episodes are dumped at once, the promise of continuation after an interval of a year or several months keeps the viewer willing to hang on till the next season.

The pressure on the creators is predictable. Since form follows format, writers and producers will be pushed to come up with series ideas. A friend of mine pitched a feature-length movie to a streaming service. The suits loved the idea but wanted it as a series and were already scanning the script outline for a plot point that could launch a second season. Some of the streaming series I’ve seen, notably Errol Morris’s Wormwood, seemed to me stretched.

If a filmmaker lands a feature film on a streaming platform, other problems could follow. We’re well aware that independent filmmakers gain few royalties from streaming; their big check tends to be the initial acquisition. At the same time, they can’t be sure that people are watching their entire movie. My barber couldn’t stick with The Irishman, even with pee breaks.

Streamers seem to have accepted grazing as basic to the viewing experience. For purposes of measuring total viewership, Netflix counts a “viewing” of a film or program as a minimum of two minutes. In the light of the two-minute rule, we might expect filmmakers to crowd their opening scenes with plenty to grab us. That goes back to TV and TV-influenced films, of course, which tried to have a strong teaser even before the credits. Now, it turns out, streaming pop songs are being crafted with shorter intros and earlier choruses “to get to the good stuff sooner.” Maybe filmmakers will be trying the same thing. Maybe they already are.

Streaming and film research

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018).

Finally, what are some consequences of streaming for researchers, educators, and your all-around obsessive cinephile?

I think it’s fair to say that home video, in the form of tape, laserdisc, and digital disc, democratized film study. From the late 1960s on, I traveled to archives and film distributors to watch films for my research. It was troublesome, time-consuming, and costly. As a grad student I took a bus from Iowa City to Chicago to watch 16mm prints of Dreyer and Sontag films. I drove to Eastman House to see films in projection. I stayed in Paris a couple of months to work at the Cinémathèque Française on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse.

As a prof here at Madison I spent hundreds of hours watching prints in our Center for Film and Theater Research. Over the decades I trekked to Denmark for Dreyer and 1910s films, to Japan for silent films, to Paris and Munich and the BFI and MoMA and UCLA and Eastman House and the Library of Congress, and above all Brussels for many, many projects. Collectors, from Manhattan, Tokyo, and Milwaukee helped as well. Kristin and I owe archivists everything.

The terrible quality of films on tape didn’t help me study visual style, but laserdiscs were a big improvement. (Hong Kong films tended not to be in Scope on tape but were on LD.) And one LD format, CAV, was frame-accurate; you could study a shot frame by frame, something not possible with many DVDs. There’s always a trade-off with any technology.

Even after even after DVDs arrived I kept up my travels. I could use discs for bulk background viewing, but often I still had to rely on prints. Sometimes I wanted to count frames (handy in looking at Soviet montage and Hong Kong action). Moreover, looking at film prints revealed that the color palettes on DVDs could be quite different, and soundtracks were often cleaned up for the home market. And of course thousands of films, especially from outside Hollywood or in the first decades of cinema, were never going to be available on consumer video. My most recent extended archive stay, in Washington in 2017 thanks to a Kluge Professorship, showed me the glories of the 1910s in prints that are mostly accessible only to researchers.

What do scholars of an analytical bent need? Entire films that can be paused. Frame stills, made photographically or through software. Clips as evidence for our claims. Stills and clips are our equivalents to quotation for literary scholars and illustrations for art historians.

Apart from convenience and cost savings, the disc revolution yielded something I couldn’t get otherwise. In an archive, it’s impossible to study film-based 3D cinema. But thanks to Blu-ray, I can stop on a 3D frame. (. . . And, for instance, spot the way Hitchcock makes the clock quietly pop out in Dial M for Murder, below). This is a unique benefit—but a waning one, as 3D discs are increasingly hard to find and 3D monitors scarcely exist any more. As I said, trade-offs.

From this standpoint, Netflix and its counterparts offer a step down from DVD and Blu-ray. In terms of choice, many films aren’t currently available on streaming, and many more never will be. You can pull a DVD off a shelf whether you’re online or not, but for streaming you need a good connection. The controls of a streaming view aren’t as precise as those on a DVD player; slow forward and back to study cuts and gestures aren’t feasible, it seems.

When cable cropped films, as it frequently did, you had recourse to DVDs, perhaps even from foreign sources. But as exclusive licensing increases, only one service will have a title. Frame grabs are possible with some software, but clips are more difficult.

Worst of all, many worthwhile films will apparently never find their way to disc. I first noticed this in 2017 when I wanted to buy a copy of I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, a Netflix release of a Sundance title. As far as I can tell, it’s not available on DVD. The same fate has befallen one of my favorite films of 2018, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Only a few years ago it would be unthinkable for a Coen Brothers film not to find DVD release. Even Roma has had to wait for a Criterion deal to make it to disc. Clearly Netflix, and perhaps other streamers, believe that putting films on disc damages the business plan. So Meirelles doesn’t include DVDs in the lifespan of The Two Popes.

Without DVDs, some cinephiliac consumers are lamenting, rightly, the loss of bonus materials. The Criterion Channel has been exceptionally generous in shifting over its supplements to the streaming platform, but other companies haven’t been. Scholars and teachers rely on the best bonus items, including filmmaker commentaries, to give students behind-the scenes information on the creative process. There are, I understand, rights issues around supplements, and bandwidth is at a premium, but there’s no point in pretending that the loss of disc versions hasn’t been important.

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas put forth the question debated in the directors’ roundtable I mentioned: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

Still, the big changeover hasn’t happened quite yet. Every year has its failed blockbusters, and films big and middling and little (Blumhouse, for instance) still continue. Arthouse theatres, which rely on midrange items, indie production, and foreign fare, are putting up a vigorous fight, emphasizing live events and community engagement.

Meanwhile, streaming makes film festivals and film archives more important. Festivals may host the few plays that a movie gets (as in the 35 fests which ran The Two Popes), and filmmakers, as Kent Jones remarks, are eager for their films to play on the big screen in those venues. Archives will need not only to preserve films but also make classics and current movies available in theatrical circumstances. Smart film clubs like the Chicago Film Society and our Cinematheque keep film-based screenings alive.

Before home video, few film scholars undertook the scrutiny of form and style. Those who did had to use editing machines like these. (One scholar called my study of Dreyer, not admiringly, the first Steenbeck book.) Ironically, just as an avalanche of films became available for academic study, and as tools for studying them closely became available for everyone, most researchers turned away from cinema’s aesthetic history and a film’s specific design in order to interpret their cultural contexts. There were exceptions, like Yuri Tsivian’s efforts to systematically study patterns of shot length, but they were rare.

Whatever the value of cultural critique, one result was to leave aesthetic film analysis largely to cinephiles and fans. Thankfully, the emergence of the visual essay, in the hands of tech-savvy filmmakers like kogonada and Tony Zhao and Taylor Ramos, eventually attracted academic attention. Film analysis has returned in the vehicle of the video essay, which is a stimulating, teaching-friendly format. Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I have participated in this trend through our work with Criterion and occasional video lectures linked to this site.

All this was made possible through the digital revolution, or evolution, and we should be grateful. Still, streaming filters out a lot of what we want to study. It’s clear that, for all their shortcomings, physical media were our best compromise for keeping alive the heritage of critical and historical analysis of cinema. We’ve largely lost physical motion pictures as a contemporary medium. (How many young scholars, or filmmakers for that matter, have handled a 35mm print?) Now, to lose DVDs and Blu-rays is to lose precious opportunities to understand how films work and work on us.

Thanks to all the archivists, collectors, and fellow researchers who made our research so fruitful and enjoyable in the pre-digital age.

A good overview of the streaming business at this point is “The future of entertainment,” in The Economist.

Kristin discusses the fantasy of the Celestial Multiplex with archivists Schawn Belston and Mike Pogorzelski. For examples of how to watch a film on film slowly, go here. Samples of editing-table discoveries are here and especially in the Library of Congress series that starts here. In another entry, I discuss the use of 3D in Dial M for Murder.

P.S. 24 January 2020: Then there’s this, from Facebook.

Dial M for Murder (1954).

Frodo lives! and so do his franchises

Given the saturation of fantasy, sci-fi and superhero films we experience today, not to mention how frequently we quote from Lord Of The Rings, it bears reminding now and again (not too obsessively, mind) just what a game changer Lord Of The Rings was.

Jordan Adcock

Kristin here:

A little over ten years ago, in April 0f 2006, I finished the manuscript of The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (University of California Press, 2007). Given that I had previously written books and essays on films by such auteurs as Sergei Eisenstein, Jacques Tati, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean Renoir, and Robert Bresson, those who knew my work were perhaps bemused by this change of direction.

I had decided to tackle this project, which proved to be an enormous but richly rewarding one, in 2002, after the release of the first part of The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring (December, 2001). Already it was apparent to me that Peter Jackson’s adaptation would be an enormously influential film, to the point where, whether or not one likes the movie itself, it would be among the most historically important films ever made. New Line used the internet to promote it at a time when it was still not common for a film to have its own studio-created website. The cooperation between the filmmakers and the video-game designers was unprecedented. The extended-version DVD releases, arriving only five years after the introduction of the format, had unique depth and breadth. The impact of its technical innovations, particularly in digital special effects and color grading, was enormous. The film’s success boosted the many independent producers around the world who had largely financed it. Not to mention the ways in which the movie transformed New Zealand through tourism, a small but sophisticated and thriving film industry, and a surge of national pride. The film and the franchise impacted the Hollywood industry in almost any way one could imagine.

In 2002, to believe all of this was going to happen and to commit to spending time, money, and effort in researching all these topics required something of a leap of faith. It was one I was confident in making. Uncharacteristically for a historian, I made some predictions about the lasting power of LOTR and its franchise. This risk was inevitable, given that I was writing about a lengthy ongoing event, one which clearly would last far into the future. The book begins: “The Lord of the Rings film franchise is not over, not will it be for years.” [p. XIII] Later I specified:

The franchise is not nearly over. Middle-earth-themed video games continue to appear. Additional licensed toys and collectible items are still being brought out. Fan activity remains lively in cyberspace and the real world. The phenomenon has reached into international culture in ways that go far beyond the commercial confines of the franchise. Politics, education sports, and religion all reflect the influences of the film. An extinct race of tiny people discovered on a Pacific island was instantly dubbed “hobbits” by headline writers and even the scientists who discovered them. [pp. 9-10]

I was reminded of these claims by two recent events. First, last week’s Comic-Con included, as usual, a Weta Workshop booth, and, as usual, several of its popular limited-edition collectible figures from LOTR were debuted there. Second, on June 23, Jordan Adcock posted an intriguing article, “Can fantasy films escape Lord of The Rings’ shadow?” on Den of Geek. Yes, thirteen years after the release of The Return of the King (December, 2003) and ten after I ended the coverage in my book, the franchise goes on, as does the influence of Peter Jackson’s film. The number of products and tie-ins is far smaller than at the height of the films’ releases, but it seems to have settled down to a steady flow.

This combination suggested that it is an opportune time to point out that this film is still influencing the fantasy genre–perhaps too greatly–and that its franchise, though reduced, rolls on. I don’t think I was being terribly prescient in predicting all this, but it’s a bit of a relief to find out that I was right.

Collectibles, video-games, and more

Fans and collectors continue to purchase LOTR studio-licensed and fan-generated items of all sorts. Some of these are from the era of the film’s release, and some are new. A search on “Lord of the Rings” in the collectibles category on eBay generates 13,476 items, only a small percentage of which are related to products relating to the novel’s franchise or that of the 1978 Ralph Bakshi film. Some of the upscale and/or rare items sell for hundreds of dollars. There is still a demand.

In my book I made no effort to catalog all the products made to that point. In fact, I don’t think it would have been possible, unless I had had access to New Line’s records of its licensing contracts. Besides, that wasn’t part of the purpose of the book. In discussing licensed products, I was more interested in digital technology had affected what sorts of items were made. There was the motion-capture for the video games, for example. There were the DVDs–a format introduced as recently as 1997, the year when Miramax signed a contract with Saul Zaentz, thus obtaining the rights for Peter Jackson to make LOTR. (In Chapter 7 I give a little history of the introduction of DVDs and the part LOTR played in the studios efforts to move from rentals to purchases of home video.) There was the facial scanning of the actors for the action figures. There was, however, a dizzying array of hundreds, or more likely thousands of other, more conventional products licensed around the world. I once bought a lottery ticket in London not because I hoped to win a prize but because it was LOTR-themed and had a picture of Elijah Wood as Frodo on it.

Here I just want to give a few examples to show that New Line-licensed products are continuing to appear. I won’t include any Hobbit-based licensed products except in passing. Obviously the second trio of films extended the original franchise, but here I am only concerned with the longevity of the LOTR’s ability to generate more products and to influence the fantasy genre.

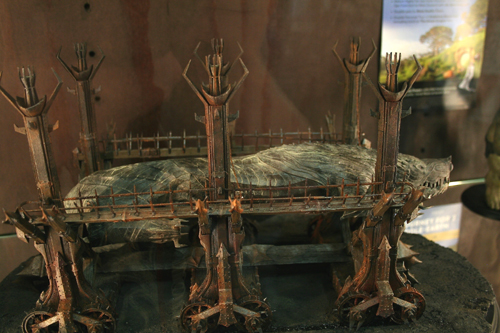

I mentioned the Weta Workshop collectible figures, which continue to be among the most popular products among devoted fans. The main fan-site, TheOneRing.net (Disclosure: I am a member of the staff) annually posts a video tour of the Weta booth at Comic-Con. This year’s video, Collecting the Precious-Weta Workshop Comic-Con 2016 Booth Tour (by TORn staffer Josh Long, about 18 minutes), lovingly moves over the glass cases containing the new items, including statues of Lurtz and Boromir enacting the latter’s death scene late in Fellowship. There’s also a big piece with the battering-ram, Grond. (I have a sentimental attachment to Grond, since it was the only one of the large miniatures made by Weta Workshop that I saw during my 2003 tour of facilities at Stone Street Studios. See above for the miniature version of the minature.) In watching the video, I didn’t keep count, but although over half of the figures are from The Hobbit, there are quite a few LOTR ones as well.

I have lost track of all the Middle-earth-based video games that have appeared since the last one the book covered: “The Battle for Middle-earth” (released on December 6, 2004, and, as far as I can tell, still in print). It was the fourth, and the first to concentrate on battles and strategies rather than on the plot of the movies themselves. By now here have been 22 of them, according to the “Middle-earth in video games” entry on Wikipedia, the most recent being “Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor” (2014). Its action takes place between that of The Hobbit and of LOTR. The total given above includes “Lego The Lord of the Rings.”

Lest one think that the only products are expensive ones aimed at the most enthusiastic core fans and dedicated gamers, I should mention that there are less pricey items. Inevitably, given the recent fad for adult coloring-books, there is one based on LOTR, list price $15.99, released May 31 of this year. (See top.) I expect a Hobbit one will follow. Warner Bros. has continued to bring out a film-based LOTR wall calendar each year. You can already pre-order the 2017 one, due out on September 15.

The posthumous career of J. R. R. Tolkien

As I pointed out in The Frodo Franchise, there has long been a franchise based around Tolkien’s original novels, which I discussed briefly. Lest we think that the film franchise must inevitably fade, it is worth noting that HarperCollins, Tolkien’s publisher, has kept the novel-based one going for decades after the author’s 1973 death.

There are, for example, numerous games like “The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game” (judging from the comments on Amazon, this must have appeared in 2013). HarperCollins publishes its own calendar, based on Tolkien’s work as a whole rather than just LOTR. Many do center on LOTR, often featuring the work of a major Tolkien illustrator. With The Hobbit having been published in 1937, however, its 80th Anniversary is being featured for 2017, also available for pre-order.

The Tolkien-based franchise items tend to be somewhat more dignified than many of the film-derived ones. This is especially true given that many of the products consist of new or reissued works by Tolkien.

Non-fans of the books may not be aware that the Tolkien publishing juggernaut goes on as well. These are not all cobbled-together variants of existing Tolkien works. Actual new texts by him appear at intervals as his son Christopher Tolkien slowly releases editions of unfinished manuscripts by his father. By now Tolkien has far more literary works published posthumously than during his lifetime, even if one does not count Christopher’s epic assemblage of the drafts for LOTR in the twelve thick volumes of “The History of Middle-earth.” (Tolkien was a notorious non-finisher and left behind many incomplete academic manuscripts as well.)

Earlier this year there appeared The Story of Kullervo, retold by Tolkien from the Finnish epic The Kalevala. Amazingly, a second is due this year: The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun (out November 3). These poems, both with historical and formal analysis by notable Tolkien scholar Verlyn Fleiger, are not for the broad audience of Tolkien fans, but they obviously generate enough interest among core devotees and scholars to be worth publishing.

Tolkien was a talented amateur artist who occasionally illustrated his own work, most notably The Hobbit, and drew many sketches and maps to help him visualize Middle-earth. The ones for LOTR were published last October as The Art of The Lord of the Rings.

There are also, of course, as many different new editions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings as the publishers can possibly justify in some fashion. Every now and then a “gift edition” with new illustrations appears. The one tied to the 80th anniversary of The Hobbit is a version illustrated by Jemima Catlin, announced for early next year. On September 22, the long-delayed facsimile of the first edition of The Hobbit is due to appear. (As I recall, it was originally supposed to be part of the 75th anniversary celebration.) This facsimile is of considerable interest to fans and scholars alike, since Tolkien revised portions of the original tale. Most notably, it contains a very different version of the famous riddles scene between Bilbo and Gollum, in which the Ring is introduced in a way completely incompatible with the premises concerning it established later by Tolkien in LOTR.

Even bits of film and audio recordings of Tolkien occasionally resurface. On August 6 at 8 pm London time, BBC Radio 4 will broadcast of “Tolkien: The Lost Recordings.” This program is based around some newly rediscovered audiotapes of outtakes from the BBC’s 1968 documentary, Tolkien in Oxford.

Fantastic stories and where to find them

Jordan Adcock’s “Can fantasy films escape Lord of the Rings‘ shadow?” was inspired by the release and failure of Warcraft: The Beginning. He uses the occasion both to explain why the Jackson’s LOTR trilogy so dominates conceptions of filmic fantasy and to suggest how Hollywood might make films that won’t be compared to it and inevitably found wanting.

Alcock largely credits the film’s lingering impact to the depth and plausibility of its visual rendering of Tolkien’s invented world, Middle-earth. He spends some time describing how Tolkien, with his brilliant command of history and ancient languages, managed across his lifetime to develop a consistent, appealing continent with different races, languages, countries, and landscapes, as well as its own history. Jackson’s film manages to create “a fantasy world with both digitally-aided grandeur and a practical, lived-in feel […] Jackson recreates Tolkien’s precision of time and setting.”

Certainly the film’s production design, its New Zealand locations, and its cinematography creates a Middle-earth that impressed even the film’s harshest critics. Its treatment of the plot and characters, though less successful overall, stuck far closer to the novel than did the more recent Hobbit trilogy. (See here, here, here, and here for my comments on the strengths and failures of the three parts of the latter.) Long-time fans like me forgave LOTR a lot, including added schoolboy humor and Arwen supposedly dying, for the visuals and the music and the near-perfect casting. And, as David, who has never read Tolkien, remarked to me when we walked out of theater after his first viewing of Fellowship, “Well, it’s better than Star Wars!” Within the fantasy genre, LOTR probably is the finest achievement in modern American moviemaking. It is no wonder that subsequent films, even twelve years later, are seen by critics either as pale imitations of it or as failed attempts to create a different but equally dense and coherent fantastical world.

Alcock’s hints at how filmmakers might avoid such problems, but in the process he also admits that his solutions are nearly impossible to achieve. First, he points out that the fantasy world need not be created across several decades–and yet if it isn’t, it will not measure up.

Authors and screenwriters don’t have to go away and devote the rest of their lives [to] creating a universe as large and self-sustaining as Tolkien’s, but against such a brilliant creation done such justice, all other attempts feel a little short-termist.

I assume “done such justice” refers to Jackson’s film, the implication being that the screenwriters need not necessarily invent an entire world but might find it ready-made in a literary work. The fact that the Harry Potter serial achieved such fierce fan devotion and high BO seems to confirm that. Though not an impressive stylist, J. K. Rowling shares with Tolkien a remarkable imagination when it comes to making the Wizarding World vivid to readers. She also anchors it just enough in the real world to make it appealing and easy to relate to. Her novels bear almost no resemblance to LOTR, apart from the fact that the Dementors seem derived from the Black Riders. To a considerable extent, the strongest aspects of the film adaptation’s version of Rowling’s world parallels that of LOTR, superb design and excellent casting being perhaps foremost among them.

Creating an original screenplay with a similarly original world, however, seems an extremely tall order. To be sure, it is not impossible. George Miller’s first Mad Max film was not a fantasy but an action-revenge film shot on the cheap with an unknown star-to-be. Its success, probably based on skillful direction and an appealing actor, allowed Miller to transform Max’s ordinary Australian Outback into a distinctive fantasy world, a post-apocalyptic Wasteland. This, too, was fairly low-budget, requiring little more than a desert, a bunch of eccentric, souped-up vehicles, and a team of daredevil stunt performers. Even greater success allowed the third film a big Thunderdome set, some modest special effects, and a second star. Most recently Miller gained a blockbuster-size budget for special-effects, an Oscar-winning co-star, and a multiplication of the weird vehicles. This is not to say that Miller’s created world is as complex as Middle-earth, but it has a visceral sense of reality and a distinctive look that set it apart from any other films, fantasy or not. But how often can you generate a Mad Mad-style franchise from almost nothing?

Alcock doesn’t mention it, but fairy tales have become a fallback option for Hollywood fantasy. Such films, adapting the originals into versions aimed at adults, have largely failed to catch on. (Given the recent failure of The Huntsman: Winter’s War, we might suspect that the success of Snow White and the Huntsman was due largely to the star power of Kristen Stewart, fresh off the Twilight series.) Fairy tales are sketchy stories with fantastical events and minimal characterization. They usually either take place more-or-less in our world or else spend little time describing the look of Faerie.The designers are left to their own imaginations to create settings, most of which tend to be pretty conventional.

Following in the footsteps of the LOTR and Harry Potter filmmakers, finding a novel or other literary property with the built-in popularity to carry a big-budget special-effects film seems the way to go. Despite the plethora of fantasy novels since LOTR appeared in the 1950s, choosing just the right one has proven a considerable challenge.

New Line’s adaptation of The Golden Compass, the first book in Philip Pullman’s brilliant His Dark Materials trilogy, was creditable but not exciting enough to create a successful film, let alone a franchise justifying the expense. Perhaps the novel was too little known in the US. The same could be true for The BFG, another British children’s classic, which is doing even worse at the box-office. (The studio could at least have had the sense to rename it The Big Friendly Giant, though that probably would not counteract what I suspect was the public’s mistaken impression that the film was aimed strictly at children, and very young ones at that.)

Alcock carries on his speculations.

So how does a different fantasy film emerge from the shade that Middle-earth put over all the competition? Frankly, it’d have to be another masterpiece to do it. The problem is the cohesion of vision or sincerity of intent from these other would-be franchises.

“Make a masterpiece” is excellent advice but rather difficult to follow. It doesn’t always work, either. Probably the two best mainstream American films I saw last year were Mad Max: Fury Road and Pixar’s Inside Out. Both were fantasies. Neither, as far as I know, drew any comparisons to LOTR from critics or fans, so they did escape its shadow. Both were highly praised by critics and won Oscars. They may or may not be considered masterpieces in the long run, but they certainly could count as such in the context of contemporary Hollywood. One made lots of money and may eventually spawn a sequel, given Pixar’s growing penchant for such things. The other, given its hefty budget, probably did not make a profit, or at any rate not one that Warner Bros. would consider large enough to justify taking the franchise to a fifth film–unless, perhaps, Miller went for a lower-budget project. So making a masterpiece may help distance a film from LOTR, but it does not guarantee a more practical sort of success.

On the issue of vision or sincerity mentioned above, Alcock touches on one subject that I think helps explain why it’s extremely hard to produce successful fantasies that have not the slightest whiff of Middle-earth about them. His point also explains why we seem to be stuck in a dismal summer where every week the same set of interchangeable films come out. He discusses Hollywood’s failure to follow up the LOTR with a fantasy franchise that would avoid the inevitable comparisons to LOTR.

Just think of The Golden Compass, New Line’s attempt to create a new fantasy franchise out of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, much more lukewarmly received and whose box office led to New Line’s end as an independent company. Now there’s food for thought–would Warner Brothers [sic], who own New Line as all but a label today, have really greenlit Lord of the Rings in its ultimate form?

I think we know that the answer to that question is almost certainly no.

In fact, LOTR actually did fail to get greenlit in its final form, though at a different major studio. As I describe in The Frodo Franchise, in 1998 Harvey Weinstein was planning to produce LOTR as a two-feature film directed by Jackson and with a budget of $140 million. When the project was a year and a half into the scripting and design process, Weinstein was called into Michael Eisner’s office at Disney, parent company of Miramax. Eisner demanded that he cut the film to one feature, made for $75 million. Jackson balked and persuaded Weinstein to put the project into turnaround for two weeks. Famously Jackson pitched it to Bob Shaye, founder and co-president of New Line, a man who knew the value of a franchise with a built-in fan base and proposed to make LOTR as three features.

Today’s New Line, a mere production unit of Warner Bros., could not undertake such a project on its own accord, and today’s Warner Bros. surely would not. With studios opting for the most established formulas, a film comparable in originality to LOTR being made, especially with all three parts shot simultaneously, would be little short of a miracle.

The only circumstance in which such things can happen would be an adaptation of a book so successful that it virtually guarantees box-office success. Warner Bros. undertook the Harry Potter series under such circumstances, given the overwhelming popularity of the book. That the resulting series of films pleased established fans and new audiences probably owes much to the fact that Rowling took an active role in consulting on the scripting and other aspects.

Today’s largely unappealing lineup of summer films (and I am writing here of mainstream Hollywood films, not including such original independent fare as James Schamus’ excellent Indignation) has been punctuated so far by two entertaining and satisfying items: The BFG and Pixar’s Finding Dorie. Both fantasies, one an undeserved box-office failure, the other a record-breaker. Which goes to show, I suppose, that good, non-LOTR-influenced fantasy (whatever its box-office record) rests with auteurs and Disney/Pixar.

Is television the answer?

Like numerous other writers, Alcock offers Game of Thrones as a model for what fantasy films with richly realized worlds might be.

If Middle-earth has a “successor,” it’s Game of Thrones. Based on George R. R. Martin’s books, the TV series has come far closer to Lord of the Rings‘ immersive world-building and cultural impact than any other fantasy, and perhaps suggests how Lord of the Rings might be adapted today.

He is far from the only writer to offer Martin’s books and the TV series based on them as an example of successful world-building. Many would say, to be sure, that the shadow of Tolkien’s and Jackson’s influence hovers over it, but perhaps that does not matter. It has brought respected long-form fantasy to TV, just as LOTR brought it to the big screen. It has gradually achieved critical acceptance, garnered a healthy number of awards, and contributed familiar tropes to modern culture, even for those unfamiliar with the books or series. I myself gave up on the novel after reading the first volume and have seen no episodes of the series. Already by the end of the first book it seemed to me that Martin was starting repeat his own devices, and if he was doing that within one book, what would later volumes be like? I certainly can’t see it as literature on a level even remotely approaching that of LOTR or even Harry Potter. I have not seen any episodes of the HBO series and hence cannot judge it. From what I can tell, it does not escape the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR, but that’s probably a matter of opinion.

Many fans who long to see an adaptation of Tolkien’s The Silmarillion have suggested that long-form television would be a more plausible medium than theatrical film. I consider The Silmarillion utterly unfilmable, except possibly in the hands of a brilliant animator, but that’s another issue. The point is that television, and especially powerful cable channels like HBO, are seen as the venue for long films that would be unlikely to be greenlit as high-budget theatrical features.

Despite appearances, I am not a keen fan of fantasy literature and films. The only fantasy novels (apart from children’s books) I have enjoyed enough to reread are LOTR, the Harry Potter series, and Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. The seven-part TV series based on the latter ended its American run on BBC 2 just over a year ago. I believe it is somewhat parallel to the LOTR film in being a reasonably successful–artistically at least–adaptation of a major work of literature It also bears no trace of Tolkien’s influence.

How does it escape? If you asked someone who had read both Martin’s books and Clarke’s whether they had read Tolkien, he or she would probably guess that Martin had and would have no idea whether or not Clarke had.

Martin admits his debt to Tolkien freely. “I revere Lord of the Rings, I reread it every few years, it had an enormous effect on me as a kid. In some sense, when I started this saga I was replying to Tolkien, but even more to his modern imitators.”

Clarke also was a Tolkien fan, but I have never seen anyone compare JS&MN to LOTR, either the original novel or the TV series. For one thing, she had other, quite different influences well, as described in a reader’s guide on her publisher’s website.

During an illness that required her to rest a great deal, Clarke re-read Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and when she finished she decided to try writing a novel of magic and fantasy. She had long admired the fantasy writing of Ursula Le Guin and Alan Garner, but also loved the historical fiction of Rosemary Sutcliff and novels of Jane Austen. These various influences were to come together in a novel which is part magical fantasy, part scrupulously researched historical novel, with teasing faux-academic footnotes referencing a bibliography of magical books entirely of her own invention.

Clarke also has a literary skill that elevates her above most writers in the genre. Her approach was not to invent an imaginary world à la Middle-earth, but to begin by setting her story in the actual English history of the Regency era. Into that she inserted two magicians seeking to revive the tradition of Faerie-derived English magic and use it to aid their country during the wars with Napoleonic France. Her seamless blend of real historical figures and events with her own inventions can leave many nonspecialist readers wondering which is which.

I have already written about the TV adaptation of Clarke’s book, pointing out both what I consider some problems with the adaptation of the narrative and some real strengths of the series. As with LOTR, the adaptation’s strengths have much to do with the design, the special effects, and the acting. Indeed,the series won two BAFTA TV Craft awards, for production design (above, designer David Roger accepts his award) and special effects. In some ways, it could have been to TV what LOTR was to film, though it was far less successful with audiences and thus will no doubt have concomitantly less influence.

The elusive “masterpieces” of fantasy that Adcock suspects might escape from the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR could be either films or TV series. But unless the studios greenlight more imaginative fare, that shadow will persist for a long time.

On the point about whether Warner Bros. would greenlight a LOTR trio of films today. I discuss studio executives’ decisions about which fantasy films to make, specifically in relation to Warner Bros. and Jack the Giant Slayer, in “Jack and the Bean-counters.” In my 1999 book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood, I suggested that Hollywood’s originality and risk-taking had declined so much, even by then, that many classic and successful films could not be greenlit; I suggested Witness, Chinatown, The Fugitive, and Alien as fairly recent examples. By now the system has become even more exclusionary.

The idea that series TV offers the advantage of more time to play out the narrative of a long book is not true in all cases. Including credits, JS&MN runs a total of 406 minutes, while LOTR runs 558 minutes in its theatrical edition and an extra two hours in the extended home-video release. (In the 50th Anniversary edition, Tolkien’s novel runs 1029 pages without the appendices. The first edition of JS&MN is 782 pages.) Ironically, in the wake of LOT’s success, New Line optioned JS&MN as a possible successor to Jackson’s film. The Golden Compass took precedence, and eventually JS&MN became available for the BBC to adapt. Made as a trilogy, with a higher budget, it would have looked great on the big screen.

Wildstyle, Gandalf, and Batman in The Lego Movie (2014)

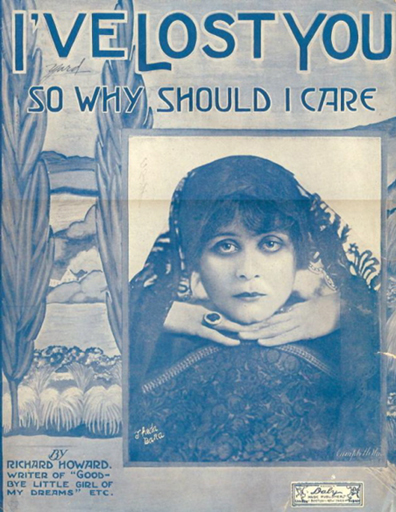

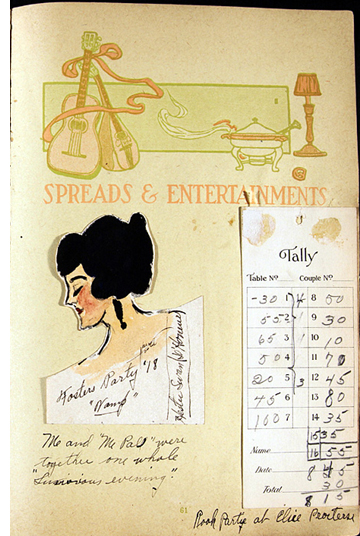

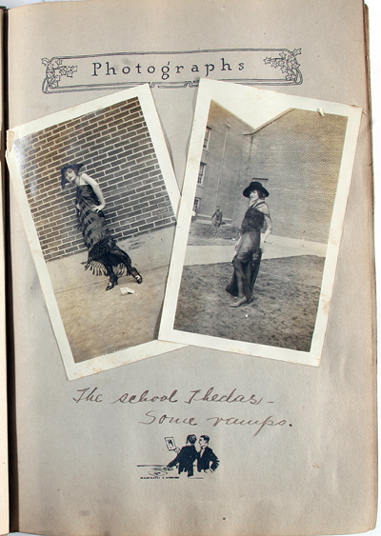

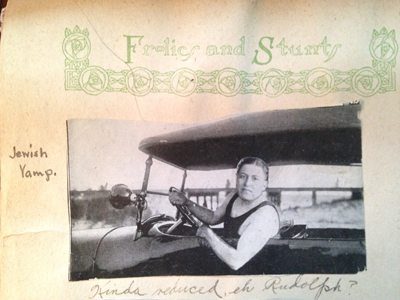

Memory books, the movies, and aspiring vamps

Kristin here:

We are happy to have a guest entry from our long-time friend and colleague, Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, who recently retired from teaching film at the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. Back in the 1990s, when David and I were helping edit a series called “Wisconsin Studies in Film” (University of Wisconsin Press), Leslie contributed Reel Patriotism: The Movies and World War I. Now she is involved in a fascinating project on the same period, the 1910s. There is much focus these days on reception studies, which focuses on trying to gauge the reactions of audiences to movies. Reconstructing mental events is a difficult, near impossible task. Yet Leslie has found a way to glimpse the ways in which American girls and young ladies of decades ago consumed and thought about movies: by studying the scrapbooks they left behind. Here’s a sample of what she has discovered.

Fangirls of yesteryear

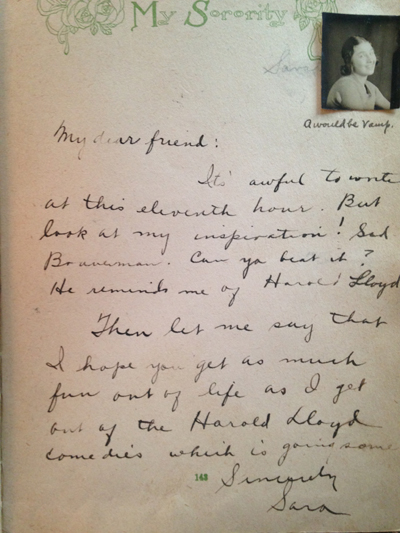

Kate Key received a scrapbook bound in red leather and entitled My Commencement as a gift from her oldest sister Ruth when she graduated from Lampasas High School, class of 1917.

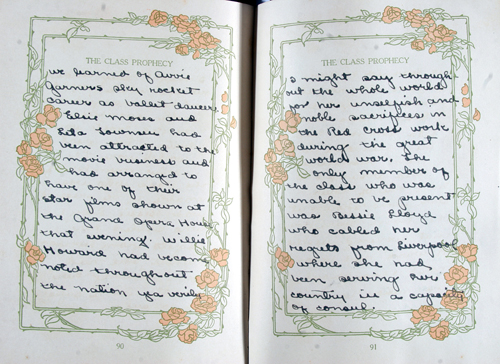

She was eighteen, born and raised in this central Texas farming and ranching community of about 2,100. As far as I can tell, there were no dedicated film theatres in town. Instead, movies alternated with concerts, vaudeville and plays on the bill at the Witcher Opera House. So, I was surprised to read in her class prophecy (a humorous forecast of what the students would be doing in a fictive future) that Elsie Moses and Leta Townsen would return for their class’s reunion in 1928 as movie stars and graciously show their films at the Grand Opera House.

This caused me to wonder whether girls who lived in other parts of the United States also made jokes out of the movies? Might scrapbooks offer film historians like me, interested in the ways that films fit into the lives of everyday people, a new sort of evidence of exhibition and reception in the 1910s and 1920s? When girls mentioned movies in their scrapbooks, or pasted in ticket stubs and theater programs, did they whisper “open sesame” to a quotidian film culture? Was that culture different from and more pervasive than that practiced by fangirls (and boys) who avidly consumed Photoplay and wrote mash notes to their favorite actors? I began to search out scrapbooks, specifically high school and college memory books.

To date, I have collected upwards of 45 scrapbooks. The scrapbooks I have found and studied are mainly the products of white, middle class and upper middle class girls. I have an example or two at either end of the economic spectrum. Despite my best efforts, I have had no luck so far finding the memory books made by African-American teenagers, though I suspect these exist. (I would welcome any suggestions.) New immigrants to the country may not have been aware of this “tradition.”

Before I survey what I have learned from American girls about themselves and about movie-going, let me tell you a bit about scrapbooks.

Multi-purpose compendiums

They have a long history in the United States. Samuel L. Clemons, Mark Twain himself, was an avid scrapbook-maker, and he patented a model featuring self-adhesive pages in 1873. By 1880, how-to books like E.W. Gurley’s Scrapbooks and How to Make Them, Containing Full Instructions for Making a Complete and Systematic Set of Useful Books, guided novices with instructions for what to include and even recipes for the glue to stick objects in place.

Arranged by topic and indexed for efficient access, early scrapbooks consolidated recipes for food or household concoctions. They served as encyclopedias and also provided entertainment. Poetry and fiction were appropriate inclusions harking back to the days of commonplace books. The scrapbook became a means for autobiography and a method of keeping family history. Gurley promoted making scrapbooks both an individual and a collective endeavor. Neighborhoods might organize a scrap-book club, and families could draw on the help of relatives to fill the gaps in their chronicles by bringing their books to reunions. For example, in 1906, Marion Renfrew, a school girl in Boston, invited her friend Eva Alberta Mooar to a party celebrating the “debut” of the “offspring of her labor and patience Memory Book.” Eva saved that letter in her own scrapbook, and the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Radcliffe preserved Mooar’s book in its archive.

Marketing scrapbooks to girls

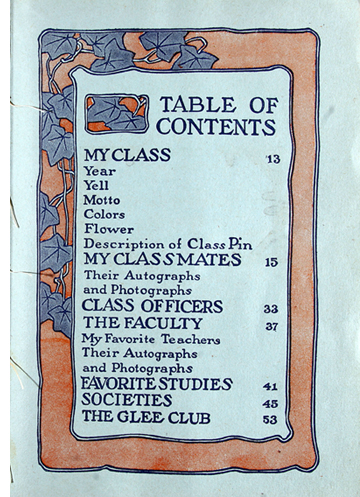

Girls were a devoted audience for advice about creating scrapbooks, and the activity became, increasingly, a gendered one. By 1905, scrapbooks were a commodity, mass produced, sold at stationery shops, and complemented by auxiliary  businesses which supported them. Companies manufactured specialty paper corners, some with elaborate designs for sticking photographs to the scrapbook page. One genre of scrapbook was the memory book designed mostly for girls and young women and given to them as presents on special occasions like graduation from high school or college.

businesses which supported them. Companies manufactured specialty paper corners, some with elaborate designs for sticking photographs to the scrapbook page. One genre of scrapbook was the memory book designed mostly for girls and young women and given to them as presents on special occasions like graduation from high school or college.

The Reilly & Britton Company offered eight different titles of school memory books for sale by 1917. The price of these gift books depended on their binding; “Fancy cloth, decorated with gold and two colors,” cost two dollars (about $40 today), but a leather cover with a velvety finish called ooze, added an extra dollar and twenty-five cents.

A blank page might have invited girls to fill in stuff of their choosing, but flowery Art Nouveau borders pushed the design toward a notion of conventional, appropriate girlhood. The filled spaces also conjured the metaphor that school was a garden, carefully tended, its flowers growing in tidy uniform beds. Memory books featured standard tables of contents that suggested what girls should preserve and how their mementos ought to be arranged. However helpfully intended, these headings also functioned to delimit what high school included and to prompt girls to tell a cheery, triumphal story in which “favorite” teachers, “best friends,” all sorts of parties, athletic endeavors, and the rituals of graduation would lead ineluctably to the happy reunion foretold by the class prophecy.

Still, what I have come to relish about girls who made scrapbooks is that they did not necessarily abide by the dictates of their books’ blueprints. They surely recognized the ideological requisites of girlhood structured onto memory book pages, but they may not have entirely subscribed to them. Often and idiosyncratically, girls changed and adapted their books.

Girls make scrapbooks to suit themselves

Elizabeth Walker travelled more than one hundred miles from Mineola, Texas to attend the College of Industrial Arts at Denton in 1918. She seemed to embrace the process of compiling My Memory Book. Hers was larger than most: 15” wide, 11” tall, and 2 ¼” thick. It appears that she received it when she matriculated and she filled in the pages as she progressed through her four years of teacher-training. After Elizabeth graduated in 1922, she became a teacher in El Paso. She continued to slide letters, documents including the Code of Ethics for Texas teachers and newspaper clippings, inside the back cover of her book during the 1930s. The most recent insertion was dated 15 July 1969. It was snipped from the school’s (now Texas  Women’s University) alumnae bulletin and brought her up-to-date on members of the class of ’22.

Women’s University) alumnae bulletin and brought her up-to-date on members of the class of ’22.

Still, at the beginning, the freshman Elizabeth had composed a bantering dialogue with her memory book’s table of contents. She treated it as a slightly irritating senior who was trying to tell her how to act. For instance, halfway down the list of things she was supposed to save were pressed flowers and leaves. “Don’t believe in ‘em,” retorted Betty.

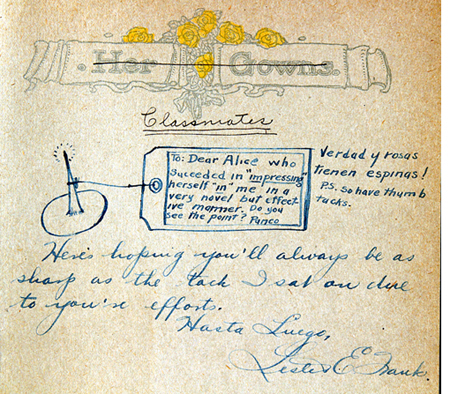

Alice Ebeling graduated in 1919 from South Bend High School in Indiana. She drew a line through the heading “Her Gowns,” replaced it with “Classmates,” and used the pages for autographs from her friends including Lester Frank (left). Apparently, he was on the receiving end of a prank she played in Spanish class.

Corinne Campau, Sophie B. Wright High School, New Orleans, class of 1919, crossed out “Favorite Studies” and pasted in a drawing of a rotund store clerk resembling the Campbell Soup kids drawn by Grace Drayton. Even better, the illustration covered up rude comments Corinne had written about a first-aid class and its annoying, irrelevant, teacher: “IT’S a joke. (‘Girls, I heard a case of a beautiful young woman—Oh, a sweet lovely young woman who fell on a brick + broke her hip.’)”

To me, there is irony, if not a nervous, dark humor in the decision of Fannie Klapman (Murray F. Tuley High School, Chicago, 1920) to glue a little cloth envelope embroidered with flowers on the page designated for “Card Parties.” The description she wrote underneath said, “New Year’s card from my brother at that time in France.” (He mustered out safely and went on to graduate from Crane Junior College in 1920.)

As well as manifesting a playful irreverence, the ways that girls altered memory books testified to a belief in their own agency. Scrapbooks were not private or secret like diaries. Girls took them to school where they solicited classmates’ autographs and good wishes; they showed them to friends who visited their homes. Although I expect many girls started to compile their memory books by following the order set out in tables of contents, when that rubric didn’t accommodate their stuff or their lives, they deliberately, messily, and with the knowledge that their actions would be seen, took matters into their own hands. They also began to make changes in the history of their lives at school almost as soon as they pasted their stuff in place. Memory books, like memory itself, were changeable, dynamic.

Movies and American girls

Since none of the books I have examined contain designated pages for films, how did American girls fit movie scraps into their memory books? When I consider my collection of artifacts, two broad patterns hold.

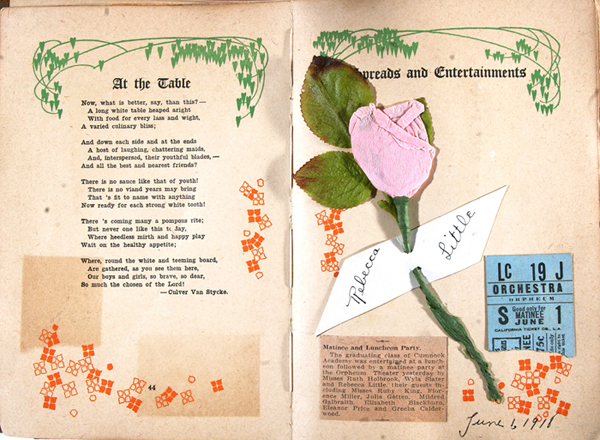

First, girls saved ephemera including ticket stubs, programs, occasionally newspaper advertisements that proved they actually saw films. (Above, Rebecca Little’s scrapbook from 1918.) I’ll call this category “Girls Go to the Movies.”

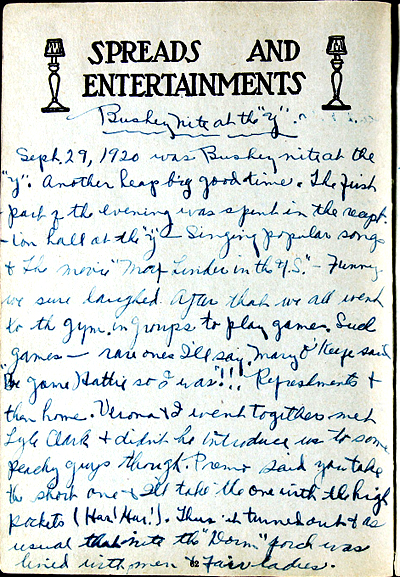

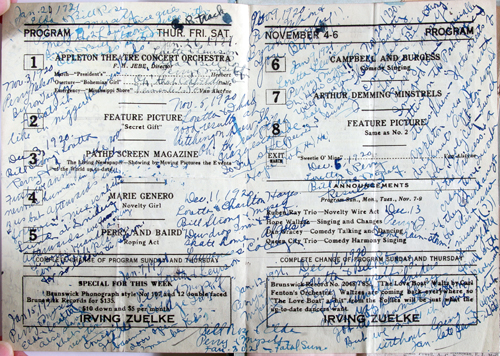

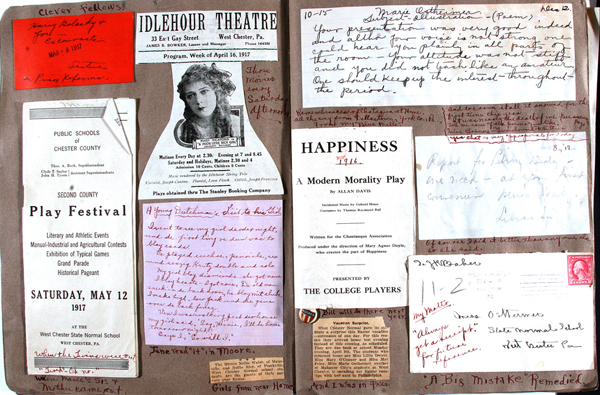

Second, and more intriguing, scrapbooks are crammed full of evidence that girls incorporated the movies–their actors, narrative conventions, and film titles—into a vernacular culture, national in its scope, spanning different religious affiliations. (Above, Hattie Stein’s School Friendship Book describes how she and her friends saw a Max Linder movie at the YMCA in Appleton, Wisconsin.) Let’s name this second motif, “Girls Make Fun with Movies.”

Girls go to the movies

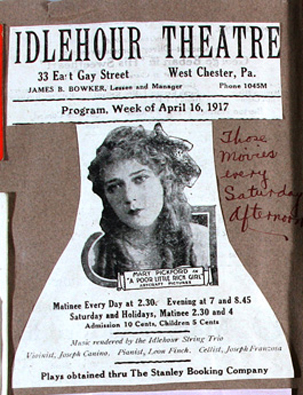

Scrapbooks show that movie-going was one activity among many that mattered to girls in the 1910s and 1920s. No one expressed this better than did Marie Ostheimer, who graduated from West Chester Normal School in southeastern Pennsylvania in 1917. The only mention of film in the thirty-six pages of her Normal Life is the Liberty Bell-shaped newspaper ad for The Poor Little Rich Girl at the Idlehour Theatre which she clipped out (see bottom image). Nevertheless, she captioned it “Those movies every Saturday afternoon.” Her annotated two-page spread surrounds Little Mary with play programs, an excellent evaluation she received for a class presentation, news cuttings about her own and her friends’ trips home, and a receipt that was evidence of some sort of kerfuffle over a doctor’s bill. It is a snapshot of learning, leisure, and life experiences among which going to the picture show was part of the routine of weekend fun.

home, and a receipt that was evidence of some sort of kerfuffle over a doctor’s bill. It is a snapshot of learning, leisure, and life experiences among which going to the picture show was part of the routine of weekend fun.

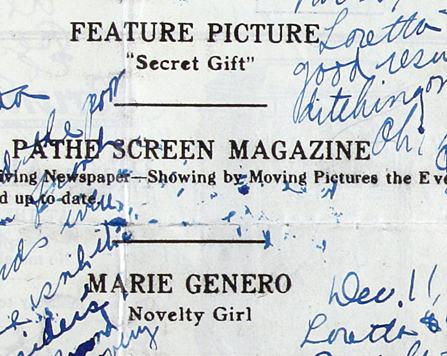

When girls did go to the movies with friends—which always seems to be the case—the screening was only one feature of the afternoon or evening’s or weekend’s entertainment. Case in point: Hattie Selma Stein, Busheys Business Academy, Appleton, WI, 1921-1922. She used a vaudeville program (above, the film Secret Gift is the 2nd turn and the chaser) to record the movies she attended during her year at school. Hattie jotted down the names of her companions, what the weather was like, how they “annoyed” the “nervous humans” seated in front of them, where they had snacks afterwards, and whether she and her boyfriend Perry won the race to the dorm’s porch swing at the end of the evening.

She didn’t always name the movie that served as the pretext for the date. Neglecting to note the film’s title wasn’t unusual in the scrapbooks I’ve examined. Instead, what girls saved was their experience of going to the movies.

For both Hester Swan from Independence, Missouri, class of 1919, and Janet Seidenman, who graduated from Western High School in Baltimore in 1926, food made an evening with friends and films tasty–an adjective which, at the time, meant not only yummy but also “in conformity with good taste.” Swan and twenty others attended a “line party,” featuring Marguerite Clark starring in Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch. “After the show Grape Sherbert and Cake were served. We all had a lovely time and enjoyed the show and refreshments immensely.” In a page of her scrapbook, Seidenman drew an arrow from a caption “Richard Barthlemess [sic] in ‘The Fighting Blade.’ Peanut chews were served and everybody was happy,” to her admission ticket, which she also festooned with an inch-long strip of Kodak film negative.

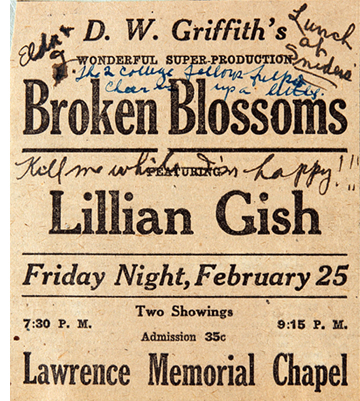

Every so often, though, going to the movies was a special occasion. Girls responded to promotional hype surrounding roadshows. When they saved movie programs, it was invariably from “big” films shown at a theaters which usually presented plays, for instance, the Majestic Theatre in Boston or the Savoy in San Francisco, or motion pictures made on the grand scale by D.W. Griffith. Hattie Stein captioned the ad for Broken Blossoms (right) showing at the Lawrence University Chapel, “Kill Me While I’m Happy.” She also noted that two “college fellows” were on hand to cheer her up and, of course, there was “lunch,” a colloquialism for snacks, at Sniders afterwards.

Girls make fun with movies

Girls did much so more than purchase tickets, sit in theaters, and watch movies before munching on peanut chews. Memory books show that girls around the United States incorporated the movies into their own playful culture. Certainly this is evidence that by the mid-teens, Americans were widely and deeply aware of information about movie stars, narrative conventions, movie-making itself, and the nuts and bolts of film exhibition. I think it’s also akin to the ways girls exercised control over their scrapbooks. When they used movies to make jokes, girls inflected the tone of the film industry’s advertising and narrative messages. They impressed their own proclivities onto increasingly standardized fare. The graduation convention of the class prophecy is a good place to start to see how girls adapted and used the movies for their own purposes.

So you want to be in pictures?

Class prophecies were an American school graduation tradition at least through the 1960s when I completed junior high. They were intended to be light-hearted, funny predictions about the future lives of the members of the class. Prophecies were guided by certain conventions of the form. They were often read publicly during graduation festivities, and it was not unusual to find pages designated for the class prophecy in memory books. Sometimes a prediction hinged on the student’s traits, interests, or romantic inclinations; it could hinge on word play about their name. It was important that the audience got the joke, or most of the jokes.

In nearly every class prophecy I encountered written from 1917 onward, at least one student was proclaimed to be destined for a job in the film industry. The most elaborate example lodged in Bertha Glennon’s memory book. Glennon graduated in 1918 from high school in Stevens Point, WI, the small city where I live. In fact, she was the author of her class’s prophecy and it was also her honor to read it aloud at Class Day a few days before the more formal graduation exercises. (She wore a dress of old-rose colored voile for the occasion.) The rhetorical device she created to frame her story was personal, timely, and more than a little macabre. The United States had entered World War I in April of Bertha’s junior year, and she had done her bit by helping to supervise in the Red Cross Room at school where students rolled bandages.

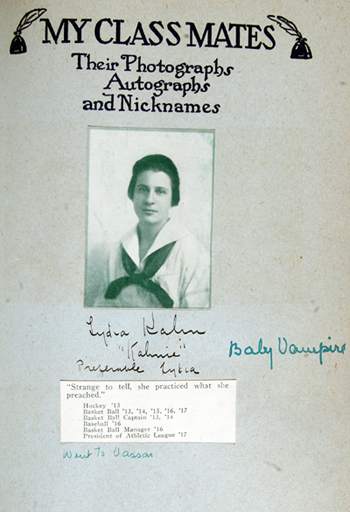

In the class prophecy, Glennon imagined herself as a nurse taking a break from her duties in a hospital on the western front. She sat on a hill and watched bombs explode in the distance. In each burst of smoke, Bertha saw a vision of the future. Boom! As the dusty haze resolved into an image, she identified classmates Ovid Meyer and Ada Kuhl in the midst of shooting a scene for a movie melodrama. Bertha Glennon described mise-en-scene, cinematography, and editing in sharp detail.

Glennon also wrote a diary that documented what she did every day during 1918, so, I know that in the five months leading up to her graduation she went to the movies fifteen times. Once she went on her birthday, another time because she didn’t have a date to the prom. She also recorded once when she went with her mother to visit a sick uncle. At his house she found a movie magazine which she read to pass the time while the grown-ups chatted. Bertha Glennon may have been a little better informed than most of my scrapbook girls, but she was not movie-mad.

Most often in class prophecies, girls were cast as movie stars. Dewene Flynt, Elizabeth Walker’s classmate at Mineola High School (1918) was sure to work for the American Motion Picture Co. and Adelheit M.W. Dettmann of Atlantic, Iowa (1918) was destined to be “Charles Chaplin’s leading lady.” After graduating in 1919 from Sophie B. Wright high school in New Orleans, Elizabeth Wakeman “will play piano at a moving picture show.”

“My Ambitions”

As you might guess, in real-life 1910s and 1920s America, relatively few girls made the transit from the high school auditorium to the movie studio, not even Rebecca Little who graduated from the Cumnock Academy in Los Angeles in 1918. (Martha Graham danced at the May Day celebration at her school that year.) Yet among the young women I have met in these books, one did actually become an actress: on the stage in the 1920s, on the radio in the 1930s, in the movies in the 1940s and 1950s, and on television in the 1950s and 1960s. She also wrote a novel, under the pseudonym Xanthippe, which was adapted into a film. Edith Meiser who graduated from the Liggett School in Detroit in 1917 is the exception that proves the rule. She was extraordinary.

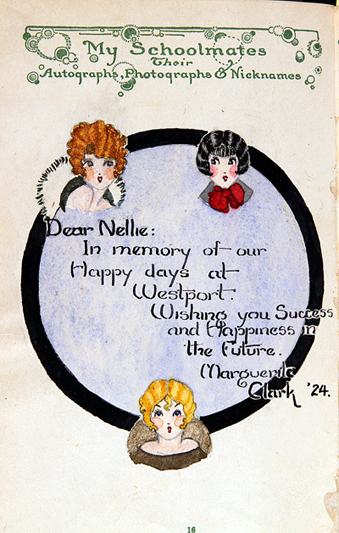

In fact, the hopes girls had for themselves and the wishes they made for others, were, in the main, conventional: success, happiness, good luck, and marriage. In a cartoon of a schoolgirl dreaming of her future, Sylvia Seidenman (Western High School, Baltimore, 1917) might have chosen the nurse with a hypodermic needle, a mother, a scholar, a ballet dancer, or a teacher with a ruler in her hand. Sylvia drew an arrow pointing at the typist, noting “This for me.” Edna Kallberg (Central High, Minneapolis, 1921) cut out and glued down a fat-cheeked toddler washing dishes (below left). “My Ambitions” was the heading which she affixed like a valance above the illustration. Nellie McKeever, from Westport High School, in Kansas City, Missouri (1924) had more talented friends and teachers than most girls did, but the same sentiments abide in their art and calligraphy (below right).

Girls didn’t make jokes with the movies when they autographed each other’s books; they wrote cautionary rhymes. “Long may you live; happy may you tarry, Court whom you please, but mind whom you marry.” (Mollie Winer warned Mary Louise Howell, Commercial High School, Atlanta, 1918.)

Some alluded to infamous moments in classes. Nearly always, they expressed the desire to be remembered. As Beatrice B. requested of Dolly Bennett (Houghton High School, Houghton, Michigan, 1921) “In the wood-box of your memory, save a little stick for me.”