Archive for July 2013

How to write: Professor Westlake is in

Donald Westlake in 2001. Photo by David Jennings.

DB here:

There can be no question of my doing justice to the writing of Donald Westlake, also known as Richard Stark, Tucker Coe, and other cover names. For background you can go to his fine site or to Wikipedia, or this warm appreciation by Michael Weinreb. Here I just want to pay brief tribute to a writer who, like Rex Stout and Patricia Highsmith, seemed incapable of composing a bad sentence. Elmore Leonard gets deserved recognition as a laconic master of language, but Westlake was no less skillful. In some ways he was more ambitious and audacious.

He was astoundingly versatile. He wrote straight novels, erotica, and science-fiction, but fame came to him when he worked in three registers: terse toughness, wry comedy, and straight-up farce.

As Westlake he wrote psychological thrillers. Best-known, I think, is The Ax (1997), about a downsized executive eliminating the competition for jobs that might come up. Also as Westlake, he wrote comic crime novels. Many of these center on a gang of inept working-class thieves led, if that’s the word, by the hapless John Dortmunder. As Richard Stark, Westlake wrote very hard-boiled novels about Parker (no first name), an utterly emotionless professional thief, and his sometime assistant Alan Grofield.

Westlake rang many variations, both high and low, on the heist formula, and his plotting was fastidious. He made one story do for two novels by telling it from different viewpoints (Slayground and The Blackbirder, both 1971). The plot of one Dortmunder novel, Drowned Hopes (1990), was so complicated that it left interstices for Westlake’s friend Joe Gores to fill in an intersecting novel, 32 Cadillacs (1992).

Nearly all the Stark books have a strict four-part structure. In the early books, this is used to mark segments of time and to shift point of view. Elsewhere Westlake uses this pattern to rearrange blocks of time, so that part one takes place in the present, leading to a crisis. Parts two and three flash back to what led up to the book’s first chapter. Part four finishes up the action left hanging in part one. This layout was both a trademark and a self-imposed constraint that Stark-Westlake had to overcome in every book. Today’s young fiction writers could learn construction from these trim, no-nonsense tales.

At the moment, though, our topic is style. Here is the opening of Stark’s The Mourner (1963).

When the guy with asthma finally came in from the fire escape, Parker rabbit-punched him and took his gun away. The asthmatic hit the carpet, but there’d been another one out there, and he landed on Parker’s back like a duffel bag with arms. Parker fell turning, so that the duffel bag would be on the bottom, but it didn’t quite work out that way. They landed sideways, joltingly, and the gun skittered away into the darkness.

There was no light in the room at all. The window was a paler rectangle sliced out of blackness. Parker and the duffel bag wrestled around on the floor a few minutes, neither getting an advantage because the duffel bag wouldn’t give up his first hold but just clung to Parker’s back. Then the asthmatic got his wind and balance back and joined in, trying to kick Parker’s head loose. Parker knew the room even in the dark, since he’d lived there the last week, so he rolled over to where he knew there wasn’t any furniture. The asthmatic, coming after him, fell over a chair.

The economy is remarkable. There’s no explicit indication that we’re in a hotel room, or that Parker has been waiting for the invasion. This is in medias res storytelling, a Stark specialty. (Many of the novels begin with a “When…” clause.) In a couple more paragraphs, Parker gets the advantage and knocks out both men. “The asthmatic went down, hitting furniture on the way.”

The faintly amused tone here (being caught by “a duffel bag with arms,” kicking a man’s head “loose,” falling over a chair) is stronger in the Stark novels centered on Grofield. He’s a semi-professional actor who goes in for theft to finance his small-town theatre troupe. Parker is introverted, stoic, and borderline sociopathic, while Grofield is laid-back, good-natured, and quick with backchat. The opening of The Damsel (1967), parallel to that of The Mourner, shifts toward the deadpan comedy of the Dortmunder capers.

Grofield opened his right eye, and there was a girl climbing in the window. He closed that eye, opened the left, and she was still there. Gray skirt, blue sweater, blond hair, and long tanned legs straddling the windowsill.

But this room was on the fifth floor of the hotel. There was nothing outside that window but air and a poor view of Mexico City.

Grofield’s room was in semidarkness, because he’d been taking an after-lunch snooze. The girl obviously thought the place was empty, and once she was inside she headed striaght for the door.

Grofield lifted his head and said, “If you’re my fairy godmother, I want my back scratched.”

Opening one eye, then the other: The micro-action is as vivid as Rod Steiger or Eli Wallach playing up to us in a Leone film. The tone has changed too. Words like “snooze” wouldn’t show up in a pure Parker novel, I think. And now we get some scene-setting, but that’s because the wounded Grofield, flat on his back, can’t give us a tour of the room through physical action. What replaces Parker’s tussle is sexy banter. After the woman finds a suitcase full of cash, she gets suspicious. Grofeld explains: “I wear money.”

Finally, here’s extravagant burlesque from a non-Dortmunder story, Help I Am Being Held Prisoner (1974). The plot, about a practical joker who is thrown into prison among hard cases, is preposterously enjoyable, but again it’s the style that arrests, and convulses. The protagonist is accompanying Eddie, a demented ex-officer after they’ve broken out of the joint, sneaked onto a military base, and settled down in the mess for dinner.

“Speaking of landing on mines,” he said, “that reminds me of another funny story.” And he proceeded to tell it. Soon our food came, and so did the wine, but Eddie kept on telling me his reminiscences. Friends of his had fallen under tanks, walked into airplane propellers, inadvertently bumped their elbows against the firing mechanism of thousand-pound bombs, and walked backwards off the flight deck of an aircraft carrier while backing up to take a group photograph. Other friends had misread the control directions on a robot tank and driven it through a Pennsylvania town’s two hundredth anniversary celebration square dance, had fired a bazooka while it was facing the wrong way, had massacred a USO Gilbert and Sullivan troupe rehearsing The Mikado under the mistaken impression they were peaceful Vietnamese villagers, and had ordered a nearby enlisted man to look in that mortar and see why the shell hadn’t come out.

It began after a while to seem as though Eddie’s military career had been an endless red-black vista of explosions, fires, and crumpling destruction, all intermixed with hoarse cries, anonymous thuds, and terminal screams. Eddie recounted these disasters in his normal bloodless style, with touches of that dry avuncular humor he’d displayed during our hour at the bar. I managed to eat very little of my veal parmigiana–it kept looking like a body fragment–but became increasingly sober nonetheless. A brandy later with coffee, accompanied by a Korean War story about a friend of Eddie’s trapped in a box canyon for nine days by a combination of a blizzard and a North Korean offensive, who kept himself alive by sawing off his own wounded leg and eating steaks from it, but who later died in Honolulu from gangrene of the stomach, didn’t help much.

It’s a challenge to a novelist to tell us something funny is coming up and then to make it much funnier than we expect, turning it into a crescendo of slapstick violence. It’s partly the appositional phrases, which pile up mishaps, and partly the mock-heroic word choices. Would you (or I) come up with epithets like “endless red-black vista” or “gangrene of the stomach”? Could we pull off that satiric stab of a massacre occurring “under the mistaken impression they were peaceful Vietnamese villagers”? Extra-credit assignment: Diagram the last sentence. Could we write something so complicated and impeccable?

By these standards, most of our novelists, beach-book maestros or middlebrow bestsellers or literary lions, don’t cut it.

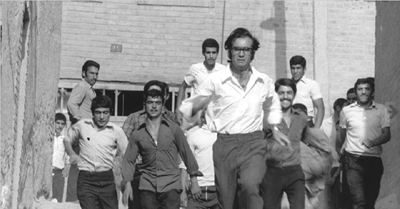

Many films have been drawn from Westlake’s books. Made in USA (1966) and Point Blank (1967) are probably the most famous, but both are very free treatments. Closer to the brusque Stark spirit is The Outfit (1974), while the French version of The Ax (2005, by Costa-Gavras) is quite watchable. I haven’t seen the recent Parker, with Jason Statham, yet. Sad to report, the several Dortmunder movie adaptations don’t make me laugh much. But Westlake had no illusions: “A movie is not the book it came from and in almost every case it shouldn’t be the book it came from.” Westlake wrote screenplays too, notably The Stepfather (1987) and The Grifters (1990).

He died in 2008. He seems to have been the most easygoing, unpretentious writing machine you’d ever want to meet. The University of Chicago Press is republishing the Stark novels in handsome uniform editions, and there remain many other Westlakes that deserve unearthing. Read them for pleasure, for the smooth carpentry of their plots, and their cunning simplicity of style.

The top image, by David Jennings for The New York Times, is taken from the official Donald Westlake site, now maintained by his son Paul. My quotation from Westlake about adaptations comes from Albert Nussbaum, 811332-132, “An Inside Look at Donald Westlake,” Take One 4,9 (1975), 10-13. This postal interview, conducted by a prisoner at a penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, includes some insider information on Godard’s Made in USA.

The Outfit (1974), from the 1963 novel of the same name by Richard Stark.

The other Kurosawa: SHOKUZAI

Shokuzai (2012).

DB here:

This year’s trip to Brussels and the Royal Film Archive of Belgium was more low-key than usual. The Cinematek’s mini-festivals were suspended this year, with Cinédecouvertes to resume next summer and the L’age d’or competition to get its own slot in the fall. The usually reliable Écran Total series at the Galeries Cinema was gone, replaced by mostly recent releases. The Cinematek’s main venue was featuring America in the 1980s (not to be despised, but these items were familiar to me) and Antonioni, because of the current exhibition devoted to him in the Musée des Beaux-Arts. And even my archive viewing was slimmed down to only a few days, as I watched some 1940s American features too obscure even to circulate on bootleg DVDs.

I wasn’t exactly bereft of choices, and I could occupy my time preparing for my Antwerp lectures on Ozu, but I was angling for something special. Luckily, our old friend Gabrielle Claes, recently retired as Director of the Cinematek, called my attention to a one-off showing of Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Shokuzai (“Penitence,” 2012) at Cinéma Vendôme, a local arthouse. The bonus: Kurosawa in person! So of course Gabrielle and I went.

Before and after the movie, I began thinking about his career and his place in recent Japanese film history.

Making waves in the 90s

Sonatine (1993).

During the 1990s a new generation of Japanese directors came to international attention. Thanks to home video formats, as well as to a rising taste for international crime and horror films, western audiences became aware of filmmakers from many countries who unabashedly worked in low-end popular genres. The success of Hong Kong films in 1980s festivals had made programmers open to Asian pulp fictions. Soon commercial companies saw a fan market for video versions of movies that were unlikely to get theatrical distribution outside Japan. These films changed forever the image of Japanese cinema as a refined and dignified tradition.

Admittedly, Western views of Japanese film were probably too sanitized. Ozu never shrank from bawdy humor, Mizoguchi could display acute suffering, and Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sanjuro were exceptionally bloody by 1960s American standards. Still, things had gotten quite wild in later years. Films that weren’t widely exported, such as those exploiting juvenile-delinquency, yakuza intrigues, and swordplay, as well as the softcore erotica known as “pink” films, would have shown western audiences something quite surprising. In the 1980s, charmers like Tampopo, The Funeral, and other export releases could hardly have prepared audiences abroad for the cinema of shock that was becoming common at home. Perhaps only Ishii Sôgo’s Crazy Family (1984), widely circulated in Europe and America, hinted at what was ahead.

The oldest provocateur was Kitano Takeshi (born, like me, in 1947), who came to directing after a solid career as a comedian. His Sonatine (1993) established him as master of the impassively violent, disturbingly amusing gangster movie. I don’t think anyone can forget Sonatine’s elevator-car shootout, which is unleashed after an awkward, semicomic passage of passengers behaving as we all do in an elevator, adopting neutral expressions and avoiding each other’s eyes. The most celebrated director of this group, Kitano influenced action filmmakers around the world and probably helped spark a revival of interest in classic yakuza pictures.

Other directors were younger and got their start in more marginal filmmaking. Tsukamoto Shinya had worked in Super-8 since childhood and made his breakthrough film, Tetsuo (1989) in 16mm, which became a cult hit on worldwide video. Soon Tetsuo II (1992), Tokyo Fist (1995), Bullet Ballet (1998), and other films showcased a frenetic, assaultive style that was the cinematic equivalent of thrash-rock. Miike Takeshi made several V-films before he hit international screens with Audition (1999), and soon his earlier theatrical releases Shinjuku Triad Society (1995) and Fudoh: The New Generation (1996) became staples of cult screenings and video collecting. Miike pushed things over the edge. Even Kitano did not dare to show a schoolgirl assassin firing deadly darts from her vagina.

I don’t mean to suggest that these directors were sensationalistic all the time. Miike made children’s films, a discreet heart-warmer (The Bird People in China, 1997), a mystical drama (Big Bang Love Juvenile A, 2005), and classical swordplay sagas (Thirteen Assassins, 2010). Kitano developed his interest in prolonged adolescence through sentimental drama (A Scene at the Sea, 1991), Chaplinesque road movie (Kikujiro, 1999), symbolic pageant (Dolls, 2002), and self-referential absurdity (Takeshi’s, 2005, and others). Still, these two directors have often returned to the downmarket genres that launched their reputations.

Nor do I want to suggest that all the filmmakers emerging to wider awareness at this time were roughnecks. Kore-eda Hirokazu began his career in documentary films, followed by the solemn, elemental Maborosi (1995). Kawase Naomi, one of Japan’s few women directors, won acclaim with the sensitive rural drama Suzaku (1997), and Suo Masayuki became a top-grossing export with his satiric comedies Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (1992) and Shall We Dance? (1996). Yet Kore-eda, widely respected for his nuanced family films, made a movie centering on a sex dolly (Air Doll, 2009), and Kawase had worked for years on autobiographical documentaries dealing bluntly with family tensions, old age, and women’s oppression. Suo’s debut was a pink film called Abnormal Family: My Older Brother’s Bride (1984) in which an affectionate parody of Ozu’s style was used to present copulation, teenage sex work, and a golden shower.

In sum, in Japan the distance between serious art and more sensual, not to say shocking, cinema isn’t that great. To take a more recent example, who would have expected that the director of the quiet, deeply moving Departures (2008; Academy Award, Best Foreign-Language Film) would have learned his craft in a series centering on men who grope women on commuter trains? (Sample title: Molester’s Train: Seiko’s Ass, 1985.)

Mysteries, mundane and supernatural

Shokuzai.

Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s career fits the trend I’ve sketched. Born in 1955, he started with pink films and V-cinema, but the theatrical release Cure (1997) won festival berths and international distribution. It presents the now-familiar mixture of mystery story and supernatural tale, in which a detective with personal problems investigates serial killings and begins to suspect that the murders are performed under some mesmeric influence. In Charisma (1999) the supernatural elements dominate, as a police officer tries to understand the powers of a tree that can magically regenerate itself. Pulse (2001) locates the otherworldly forces in the Internet, where ghosts take over people’s lives and eventually lead humans to flee Tokyo.

Kurosawa’s films became perhaps too quickly identified with what was known as J-horror. His taut, slowly unfolding plots and calm but menacing style did have something in common with the Ring series (1998-2000) that was becoming popular at the time. At the same time, Kurosawa draws on a some story elements common across Asian crime and horror films: revenge, often by a parent or elder figure in the name of a lost child; the suggestion that childhood, especially that of girls, has a corrupt and sinister side; and a sense that modern technology such as computers and cellphones harbor demonic threats. But I think that his films were more thematically ambitious, even pretentious, especially in the case of Charisma, with its ambiguous ecological symbolism. And like his peers, he wasn’t interested only in suspense and shock. His mainstream family drama Tokyo Sonata (2008) attracted western viewers with no knowledge of his spookier side.

The policier aspect is evident from the start of Shokuzai. Originally a five-part TV drama broadcast in weekly installments, it starts with the rape and murder of a schoolgirl, Emili. Her four playmates have seen her attacker ask her to leave the playground with him, so when she’s found dead, the police and Emili’s mother Asako press the girls to identify him. Through fear or trauma, none of the girls can remember what he looked like. Asako summons all four to her home and demands penitence from them in the future—in ways each one must find for herself.

After this prologue, Shokuzai downplays supernatural elements in favor of character studies of the four surviving girls, with a “chapter” devoted to each. The young women live separate lives and their paths don’t intersect; only the implacable Asako reappears in each thread. By the final installment, Asako has more or less given up tracking the killer, but when one young woman accidentally recognizes him, on TV, Asako pursues him and discovers the roots of the crime in her own past.

This is pretty much modern thriller territory, with a whiff of Barbara Vine/Ruth Rendell in the film’s effort to trace how a single event resonates terribly through innocent lives. As with such thrillers, the strength of Shokuzai seems to me to lie largely in characterization and atmospherics. Each young woman is given a distinctive personality, and each one’s professional and personal life fifteen years after the crime is presented with a teasing, hypnotic deliberation. Sae is a meek, sexually immature nurse who is lured into marriage with a rich former schoolmate; his seemingly harmless obsession turns domineering. Maki becomes a schoolteacher herself, and her relentless, demanding methods soon antagonize the local parents—until she unexpectedly proves herself heroic. Akiko has become a hikikomori, a recluse, and is only briefly drawn out of her drowsy existence by the daughter of her brother’s girlfriend. The good-natured little girl in effect reintroduces Akiko to childhood. In the penultimate chapter, the sexual bargainer Yuka seeks to seduce her brother-in-law and to take revenge upon her sister for being their mother’s favorite.

Each young woman is associated with an object or gesture seen in the prologue: a French doll, a bloody blouse, a policeman’s kindly squeeze on the shoulder. At one level, these bits of the past take on psychological impact. The trauma around Emili’s death suggests sources of the grown-up women’s neurotic behavior. Maki, the girl who after the killing rushes frantically through the school looking for someone in authority, becomes an all-controlling schoolteacher. Akiko’s bloody school blouse will find its fulfillment in a brutal crime involving a girl’s toy.

Yet these associations carry extra resonances. It’s partly because of the quietly ominous way Kurosawa films commonplace objects like a ruby ring or a jump rope. Maybe there is a whiff of the supernatural after all, given the unexpected connections revealed between the men in the women’s later lives and the little girls’ fetishes and rituals. Fate plays such cruel tricks that it might as well be malevolent magic.

The demand for expiation and the mother’s implacable intervention in an investigation will remind many viewers of Bong Joon-ho’s Mother (2009, South Korea) and Nakashima Tetsuya’s Confessions (2010). Asako’s characterization gets fleshed out in the fifth episode, which presents two crucial flashbacks leading up to the crime. One even replays a moment leading up to the murder, supplying a previously withheld reverse-shot in the manner of Mildred Pierce’s replay. (Some things don’t change.)

Presumably the recurring flashbacks to the prologue were also motivated by the rhythm of the weekly TV broadcasts. Viewers couldn’t be expected to recall everything from earlier installments.

You can object, as critics have, that the revelations in Shokuzai’s finale are creaky and far-fetched. Raúl Ruiz, in Mysteries of Lisbon, embraces the arbitrariness of old-fashioned plotting, with its felicitous accidents, secret messages, and hidden identities. He scatters these devices freely throughout his story, making them basic ingredients of his film’s world. Instead, Kurosawa introduces most such devices at the last minute, which makes them more surprising but also more apparently makeshift. Still, you can argue that once you eliminate purely supernatural causes for the creepy things we see and hear, audiences will embrace convoluted plots (as again, in Confessions) to rationalize their thrills. As so often in popular narrative, no coincidence, no story.

Quiet elegance

Kurosawa uses long takes, fairly distant framings, and solemn tracking shots to heighten an atmosphere of dread. The questioning of the children is played out in an extreme long shot, refusing exaggeration but conveying very well the flat, obdurate refusals confronting the cop.

In the Q & A after the screening, Kurosawa explained that he didn’t alter his filming style much for the television series, although he found himself writing more dialogue than he would have included in a theatrical feature. His visual technique displays a dry, precise elegance–the Japanese might say it possesses shibui— and it has, as far as I know, no equivalent in current American cinema. The compositions are painstakingly exact, though they’re not as rigidly geometrical as Kitano’s planimetric images and they don’t self-consciously evoke Ozu in the way Suo’s do.

Everything lies in plain sight. The bright, saturated tones of the childhood prologue contrasts sharply with the wan color schemes throughout the present-day sequences.

Kurosawa’s staging has a clarity and point that’s rare today. He often lets significant action unfold without interruption. For example, in Yuka’s flower shop, he gives us a shot lasting nearly a minute. Yuka’s sister has come to voice her suspicion that her husband has had sex with Yuka. Kurosawa moves the two women around the frame discreetly, sometimes hiding their facial reactions, and using the Cross to shift their positions both laterally and in depth. A single step forward can mark rising tension as the sister demands an explanation, and a retreat from the foreground can create a mini-suspense about Yuka’s reaction.

After hiding Yuka’s reaction in the distance, Kurosawa creates a mini-climax by having her turn abruptly to the camera before bending over and sobbing.

Kurosawa saves the cut, as David Koepp might say, in order to ratchet the drama up. In a closer view we can watch the sister, ashamed of her suspicions, consoling Yuka and succumbing to her lies.

Contrary to what proponents of intensified continuity will tell you, you can build an engrossing scene without fast cutting, tight close-ups, and arcing camera movements. Like American directors of the studio era, Kurosawa always knows the best place to put the camera, and he keeps things simple and direct.

Kurosawa’s patient, compact staging has its counterparts in the work of Claire Denis, Manuel de Oliveira, and many other European filmmakers. It’s just that it’s a bit unexpected in the 1990s Japanese iconoclasts. For all their self-conscious extremism, they have wound up reinvigorating certain classic techniques of cinematic expression. This is just one of many reasons to catch Shokuzai on a screen, big or little, near you.

You can see some trailers and extracts from Shokuzai here, but you have to sit through a wretched Peugeot ad every time.

Shokuzai is coming to the Vendôme on 24 July.

On the earthy side of Japanese culture, which I think feeds into the 1990s trends I’ve mentioned, see Ian Baruma’s Behind the Mask.

P.S. 23 July 2013: Adam Torel of the ambitious Third Window Films writes to tell me that the company is releasing Eyes of the Spider and Serpent’s Path on DVD in September. Third Window distributes other recent Japanese films, including items by Miike and Tsukamoto.

Il Cinema Ritrovato, number 9 and counting

Kristin here:

For a second year running I unexpectedly ended up attending Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna alone. (For the 2012 report, see here.) Last year David’s back went out shortly before we were due to leave. This year an exceptionally long stretch of days with heavy thunderstorms resulted in flooding in our basement (where many of our books reside). I had already been in London for nearly three weeks and was planning to meet David in Bologna. Instead, he valiantly stayed home to deal with the unwanted water, and I went on to the expanding smorgasbord of films presented by the festival.

The programmers are limited to their existing venues: the relatively small Mastroianni and Scorsese auditoriums in the Cineteca’s building, the larger Arlecchino and Jolly commercial cinemas, and the vast space of the Piazza Maggiore for the nightly open-air screenings starting at 10 pm. This year for the first time, to accommodate the many films, post-dinner screenings, starting at 9:30, 9:45, or 10 pm, were scheduled in the Scorsese and Mastroianni.

Faced with so many options, one could only focus on a few of the bounteous threads of programming. I opted to see as many of the early Japanese sound films as possible, the early (pre-mid-1960s) Chris Marker works, and the annual Cento Anni Fa series, this year presenting a sampling of films from 1913, the year when worldwide the cinema seemed to take an extraordinary leap forward in complexity and inventiveness. Whenever there was a gap, I could fit in items from the other threads: European widescreen movies; cinema of the 1930s that presaged the coming war; a retrospective of the work of Soviet director Olga Preobrezhenskaja, another devoted to Vittorio de Sica, primarily as an actor, more Chaplin restorations from the Cineteca’s ongoing project, the newly restored Hitchcock silents, and of course various other newly restored films. A tradition of highlighting the work of a Hollywood director has become a centerpiece of Il Cinema Ritrovato, with the subject this year being Allan Dwan.

Japanese Talkies, Part 2

Last year I caught only a few of the films in the retrospective of early Japanese sound films. I regretted not being able to see more, but the Ivan Pyriev and Jean Grémillon threads lured me away. This year the rival was Chris Marker, but I determined that by careful planning, I could fit almost everything in both retrospectives into my schedule. These became my top priorities.

The Japanese series is ongoing and organized not by auteurs but by film companies. The programmers were again Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, whose encyclopedic knowledge of the history of Japanese studios of the 1930s made  for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

I had seen only one of the films in the series, Mikio Naruse’s 1935 masterpiece, Wife, Be like a Rose. I didn’t remember much about it, except that it was marvelous, and it proved so on second viewing. Naruse often has been compared with Ozu, both during his active career and since. Overall, he seems to me not as great a filmmaker, but Wife, Be like a Rose must be among his best films and would undoubtedly rank alongside some of Ozu’s work of this period. A moga (modern girl) is upset that her father has deserted his family in Tokyo and established another family in the countryside. Determined to drag him back to his familial responsibilities, the daughter confronts the possibility that he was right in leaving her mother. The film is shot in a somewhat Ozu-like style, with low camera heights and across-the-line shot/reverse shots. Still, there is no slavish imitation (the climax is filled with camera movements), and Naruse’s film is both moving and stylistically engaging.

Naruse was the only director with two films in the retrospective. His Five Men in the Circus, also released in 1935, was a less ambitious work than Wife, Be like a Rose, but it was an entertaining story of musicians on the road earning a living during the Depression, encountering disappointments in work and love.

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

The Japanese musicals were all charming films. Romantic and Crazy (1934) starred the popular comic performer Kenichi Enomoto, better known as Enoken. (In the West, he is most familiar from his comic role in Akira Kurosawa’s third feature, The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail [1945].) Romantic and Crazy is basically a college musical imitating the early 1930s films of Eddie Cantor–and at  moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

Another notable film was Sadao Yamanaka’s Kôchiyama Sôshun (1936), one of his three surviving feature films. (These and fragments of others are available on a new set from Eureka! in its “Masters of Cinema” series.) It’s a strange film, partly comic but mostly a crime story. An attractive woman, played by a very young Setsuko Hara, keeps a shop owned by a local gangster, and tries to prevent her thuggish younger brother from becoming a criminal. The title character, Kôchiyama Sôshun, appears to be an idler getting by on the income from his wife’s gambling house, but he apparently has unlimited sources of money. Despite his shady background, Kôchiyama tries to help save the heroine when, after her brother has gambled away the house and shop, she is forced to sell herself into prostitution.

The seasons of early Japanese sound films will continue during the 2014 Il Cinema Ritrovato, with a focus on Shochiku.

Chris Marker’s youth returns

It has been difficult to see any of Chris Marker’s early films lately. By early I don’t mean early 1950s, but essentially anything made before La jetée (1962). As Florence Dauman of Argos Films explained in an introduction to one of the programs, Marker thought of the films made during his first decade as a director as mere trials and didn’t want them seen again. Fortunately Dauman and others made the decision not to honor his wishes. Perhaps Marker thought that his later films, more complex and philosophical (Sans soleil comes to mind), were how he wanted to be remembered. But the playful, emotional, politically committed film essays of the 1950s and early 1960s are precious and not to be abandoned. We were treated to excellent restored prints of them during the festival.

The only film that made me understand Marker’s reluctance to show his early work was Olympia 52 (1952), a documentary on the Olympic Games in Helsinki. It was Marker’s first professional feature, and it is barely competent. The coverage sticks almost entirely to the track and field events, with endless 100-meter dashes, shot-puts, hurdles, high jumps, pole-vaults, and so on. The several cameras filming the events rendered very different footage, ranging from excellent to dark gray. Cut together, these shifting images look amateurish. A brief series of shots of yacht-racing, equine-jumping, and other sports leads back to more shot-puts, hurdles, pole-vaults, and so on. Valuable practice for Marker, no doubt, but a film which bears no hint of the talent soon to burst forth.

It was wonderful to see Letter from Siberia (1958) again after so many years. David and I had taught it in an introductory class in the mid-1970s. Its repeated series of shots of a bus on a street and some men doing construction work has been an example of the powers of the sound track from the very first edition of Film Art in 1979 to the present one.

There were no subtitles on the prints, and the headphone translation could never keep up with the rapid, contemplative voice that accompanied these images, so I missed much of the point of Dimanche à Pékin (1956) and Description d’un Combat (1960). Marker’s written contribution to Joris Ivens’ documentary …À Valparaiso (1963) presaged much of his later work. His 16mm documentation of American hippies’ gently protesting assault on the Pentagon in La sixiéme face du Pentagone (1968) made me proud to be an American (something not too easy in the light of recent events).

Dwan at his peak? The 1920s

I missed most of the Dwan films, but I managed to fit in three of the four from the 1920s. These did not include the 1923 Gloria Swanson vehicle Zaza, alas, though I heard good things about it from friends who saw it. The three I caught seemed to represent Dwan at the height of his career.

I had seen the other Swanson film, Manhandled (1924) before, but it was a treat to see it again. It’s a strange mixture of realism–most notably in the famous early scene of the working-class heroine’s commute home on a crowded subway–and an absurdly melodramatic plot in which she manages to attain the pampered stature of a kept woman while maintaining her virtue. Swanson is a delight, and the fact that the film is incomplete, missing a scene in which she demonstrates her talent for mimicry by imitating various characters, including Charlie Chaplin, is a true pity. We can only hope that a complete version will someday surface.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

As always it was a treat to hear anecdotes from the man who had the inspired idea of interviewing stars and filmmakers from the silent era before it was too late. The Iron Mask was another impressive print, dated 1999 and bearing a Carl Davis score. I much prefer Douglas Fairbanks in his early comedies to his more famous swashbuckler films, and the story and staging in this one seemed very by-the-numbers, especially in comparison to the more imaginative East Side, West Side. Its main interest, and that was considerable, lay in the impressive sets designed by Ben Carré and William Cameron Menzies and its glowing cinematography by Henry Sharp.

By the end of the week, I was happy to have caught these particular Dwan films. From conversations with people who followed his thread more closely, I gathered that they thought the 1920s titles were the best of those shown in Bologna.

Glimpses of 1913

There was a time when the Cento Anni Fa series, programmed by Mariann Lewinsky, was a must-see for me. With the proliferation of screenings, however, seeing all of the sessions has become difficult, and I found myself ducking in and out to catch a few items now and then. I wanted to see the new restoration of Mario Caserini’s remarkable feature, Ma l’amor mio non muore!, but there was something else I wanted to see playing opposite both screenings. Luckily the Cineteca has put the film out on DVD. The catalog claims that it’s the first diva film. It stars Lyda Borelli in a spectacular performance, plus it has many complex examples of what David calls tableau staging (see here), especially in the amazing set in the frame above. One of the must-see films of 1913.

I am not a great fan of Italian (or any other) spectacles set in ancient times, and there were quite a few included in the series. They also tend to be rather long, which makes it more difficult to fit them into a packed schedule. Still, I did like Spartaco ovvero il gladiatore della Tracia (Giovani Enrico Vidali). Its minor actors and extras avoided giving the usual impression of people milling around in sets; they actually behaved as if they were living in real places in antiquity. The actress playing Emilia (not listed in the catalog) gave an engaging performance, quite the opposite of the diva approach, though Mario Guaita as Spartaco depended largely on rolling his eyes upward at frequent intervals to convey suffering. As Ivo Blom points out in his program notes, however, Guaita turns out to be the the first strongman figure, bending iron bars with his hands a year before Bartolomeo Pagano supposedly innovated this iconic gesture as Maciste in Cabiria.

More than that film, though, I was impressed by Luigi Maggi’s La lampada della nonna. It begins with an old woman knitting beside an oil lamp. When her grandchildren try to present her with a new electric one, she objects. The bulk of the film is an extended flashback set in the era of the Risorgimento, with the heroine in her youth helping to shelter a wounded officer and falling in love with them. The lamp, seen unobtrusively in the background of several shots, comes to play a key role as a signal in the climactic scene. Again there is an unusual degree of naturalness in the acting, with the extras in the military campground scene, for example, all given bits of plausible action to collectively present the impression of an actual campground. The flashback structure, framing, staging, and acting all reminded me strongly of Griffith at the same period.

There were slight but charming films like Léonce et Toto, a very funny Léonce Perret comedy (director unknown, but probably Perret). Léonce’s wife receives a tiny chihuahua as a gift and immediately dotes on it, to the point of putting it on the table at meals. The hero is disgusted and tries increasingly devious and extreme ways of getting rid of the little pest. Another was an American documentary with the irresistible title Aquatic Elephants. Who would not delight in five minutes of elephants rolling cheerfully in a pond while silly men try to stand on them and invariably fall into the water?

DVDs and Blu-ray

Just about every film scholar and buff in the world probably knows the Criterion Collection. As a brand, it’s sort of the Pixar of high-end home-video. We all have at least some of its releases on our shelves, whether lined up alphabetically or by director or by number. This year a session was devoted to the background of the company, with guests Jonathan Turell and Peter Becker (left and right, above). The history of Criterion is a bit complicated. Briefly, it was founded in 1984 to release laserdiscs and eventually, after the introduction of DVDs in 1997, switched to that format, eventually adding Blu-ray discs. Becker joined the company in 1993.

Criterion is closely linked to the historically important Janus Films, founded in 1956 and responsible for distributing many of the most famous art films of subsequent decades. In 1966 it was acquired by Saul J. Turell and William Becker, the fathers of the two speakers. Their sons are now co-owners of the Criterion Collection, of which Peter is the president; Jonathan is director of Janus.

To David’s and my generation of film students, Janus was a key player in our discovery of art cinema. How many of us, I wonder, first watched many of the classics that now grace Criterion DVDs through the landmark PBS series, “Film Odyssey,” in 1972? I first saw and was bowled over by Ivan the Terrible in that series. Three years later, when I was working on my dissertation on the film, I called Janus and got through to Saul Turell. Could I possibly borrow 35mm prints of the two parts of the film, I asked, explaining that I needed and to take frames from good copies. He gave me the name and phone number of a person in the company’s storage facility to call, and she arranged to ship the prints to me. I was able to spend weeks in front of a Steenbeck in the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, wallowing in strange, beautiful images and sounds. Nearly all the illustrations in my book, Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, were taken from those prints.

That same spirit of cooperation with academic film studies has lived on. David and I are grateful for our friendly relationship with the Criterion team, who have cooperated in our creation of video-based online examples tied to Film Art: An Introduction. (The examples all come from Janus films; a sample analysis of a clip from Vagabond is available on YouTube.)

The pair’s presentation included a video, The Criterion Collection in 2.5 Minutes. It features over 600 clips from the collection as of September 1, 2012, chosen and edited by Jonathan Keogh, clearly one of the company’s most devoted fans. Although cut too fast too allow the viewer to identify every title (and I must admit, I don’t think I could recognize every single one, even with longer excerpts), it’s an exhilarating paean to great cinema.

The plaudits in the festival’s annual DVD contest were spread, deliberately or not, among many DVD/Blu-ray companies, with none winning more than one award. A number of items that we’ve covered here took home awards: Flicker Alley’s collection of films by the Russian firm in Paris, Albatros, was deemed the best boxed-set of silent films; and Edition Filmmuseum’s set of four Asta Nielsen films shared the award for best rediscovery. Our friends at the Belgian Cinematek won best Blu-ray boxed set for the “Henri Storck Collection.” Criterion took home best Blu-ray for its edition of Paul Fejos’s Lonesome. For these and the other winners of this year’s DVD awards, see Jonathan Rosenbaum’s website. (As one of the jurors, he explains the changes in the award categories this year.)

The Return of Carbon Arcs

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

They came from the remarkable 2006 find of a wealth of films, equipment, posters, and even sets and puppets, in a warehouse in Belgium. The collection all originated from the stock of the traveling Théâtre Morieux, which had started with puppet and magic-lantern programs, adding films in 1906. All this material had been in the warehouse for a century and was in good condition.

The projector used for the program was not from 1906, but it was old, and very heavy. I happened to be between films when a truck with a crane delivered the projector and a generator and a team set up the equipment facing a small screen on one side of the courtyard. (At the very top of today’s entry, the crane lowers the projector body onto its platform. Above, festival coordinator Guy Borlée watches as the lamp housing is attached. Bottom, all ready to go and waiting for the sun to set.) The projector was a Prevost, of French manufacture, I would guess from the 1940s.

When 10 pm arrived, it became apparent that the light from buildings near the Cineteca could not be entirely controlled. Shadows of the trees in the courtyard were cast on the screen, with light patches between them. But traveling cinemas no doubt frequently set up in venues where nearby sounds and other distractions abounded, so we all accepted the light pollution as part of the experience.

Perhaps the most memorable of the films was Cambrioleurs modernes (“Modern Burglars,” director unknown, 1904). In some ways it was rather crude, with the set consisting of two large painted house façades facing each other, angled from the front, and a wall beyond them. The acrobatic burglars arrived over the wall to rob one house, propping a long board against an upper window to use as a chute for sliding furniture and other large objects down.

The action becomes faster and more impressively choreographed as police arrive, also over the wall, and give chase. Soon burglars and comic cops are diving through windows and doors in the two buildings, as well as performing comic acrobatics on the chute. The whole thing, as far as I could tell, was done in a single take, though there might have been some invisible cuts. If it was indeed one shot, it was a most impressive piece of staging and performance.

This ‘n’ that

Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1963 crime/road movie L’Aîné des Ferchaux (based on a minor Georges Simenon novel) is almost impossible to see on the big screen, apparently due to some sort of rights problem that keeps the French distributor from circulating it. (It is available on a region 2 French DVD without subtitles.) The festival managed to show it in the European widescreen thread by borrowing a print from Svenska Filminstitutet, complete with Swedish subtitles. Translations in Italian and English were projected on small screens below the image. I quickly got accustomed to skipping down to the read the third set of subtitles. It’s certainly not one of Melville’s masterpieces, but it’s definitely worth seeing.

The basic premise is that an unscrupulous banker, Dieudonné Ferchaux (veteran French star Charles Vanel), flees arrest by flying from Paris to New York and then setting out toward the South via car. Michel Maudet, an unsuccessful young boxer (Jean-Paul Belmondo), also unscrupulous but so far with no apparent serious crimes to his name, goes along as his secretary. Although the two seem to like each other, Michel becomes increasingly tempted to steal the suitcase stuffed with cash that Ferchaux has picked up in New York, while Ferchaux seems to lose interest in visiting various other places where he has stashed away large sums. The gradual switch in their power relationship furnishes one main line of interest.

The film is also remarkable in that the two stars did not go to the U.S.A. to appear in the considerable amount of landscape footage shot there by a second unit. Instead, they worked in interior sets in France, as well as exteriors that pass for America. Melville managed to stitch these two kinds of footage into a reasonably convincing depiction of an American road trip.

Another film that has long been hard to see outside Italy, at least in its original form, is Rossellini’s L’Amore (1948), two contrasting short tales displaying the acting talent of Anna Magnani. The first, Une voca umana, is based on Jean Cocteau’s  much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

The longer second part, Il Miracolo, is more engaging and original. It is based on an idea by Fellini and a script by Tullio Pinelli and Rossellini. A feeble-minded homeless woman, Nannina, who is tending a herd of goats near a small Italian village, meets a traveler (played by Fellini, left) whom she, being very pious, assumes to be St. Joseph. He offers her wine and, when she falls asleep, rapes her. Learning that she is pregnant, and not realizing what the traveler did, Nannina becomes convinced that she is carrying the baby Jesus. She is teased and hounded by the townspeople. This part of the film led to censorship problems, not because of the sexual content (the rape is simply skipped over and merely implied) but because of the apparent parody of the Immaculate Conception. (This, too, has been available in a mediocre copy without subtitles on an Italian DVD.)

Apart from its innate interest, L’Amore is historically important for the “Miracle Decision” in the U.S., where it was banned for sacrilege. The Supreme Court decision in the case led to the extension of first-amendment protection to cinema.

Il Cinema Ritrovato has become a venue for the exhibition of the latest restorations by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation. This organization restores films from countries whose archives do not have the means to do such work. Since 2007, the foundation has preserved on average three films a year. This year the items on show at Bologna included Filipino director Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light (1975, also known as Manila in the Claws of Neon). I had never seen a Brocka film (it’s discussed in a passage of Film History: An Introduction, for which David was responsible), but I was impressed by this one, widely considered to be his best.

It follows a naive young man from the countryside whose girlfriend has become the victim of sex-trafficking; he seeks her in Manila and experiences unfair wage practices and other forms of corruption. Brocka managed to blend seamlessly an absorbing narrative with sympathetic characters and an undercurrent of bitter social critique. Remarkably, Brocka also shot a 22-minute making-of documentary, quite similar to modern DVD supplements, that explains how he created realistic scenes of construction work with a small budget and shooting on location with non-professionals.

Another World Cinema Foundation restoration shown this year is the 1971 classic, Ragbar (Downfall, directed by Bahram Bayzaie). Given the extraordinary burst of creativity that has occurred in Iranian filmmaking since the 1980s, I had high hopes for this. In some ways it resembles more recent classics, most notably in its setting in a school.

The hero is a misfit who has come to teach at the school and becomes the victim of pranks and taunts by his unruly students. A rumor gets started that he is in love with the older sister of one of the students, and in attempting to scotch the rumor, he falls in love with her. Gradually he comes to understand his students and gain their respect. The film is entertaining, though the slim plot seems dragged out too long. The approach is more like commercial mainstream art cinema than like more recent Iranian films. Culturally it is quite interesting, showing some of the customs of the era shortly before the overthrow of the Shah. Most notably the women wear western-style clothes, and some are unveiled.

Unfortunately I had to miss a third Foundation restoration, Ousmene Sembène’s early short Borom Sarret (1969).

The World Cinema Foundation screenings are among the high points of Ritrovato, and I look forward to seeing more of them in years to come. Among all the festival’s restorations of well-known classics (this year Hiroshima mon amour, Richard III, and so on), it was a pleasure to see as well some well-known but hitherto difficult to see films. I hope all three, plus Brocka’s making-of, are included in a future WCF DVD set. (The first set was issued last year and is available from amazon.fr.)

Finally, I managed to see a few of the films in the “War Is Near: 1938-1939” thread. One was a program of three of Humphrey Jennings’ less familiar documentaries, all from 1939: Spare Time, about how working-class people spend their leisure time; The First Days, on the preparations for war in England after its declaration; and S. S. Ionian, on a cargo ship paying visits to ports of call in the Mediterranean. The first two had the true Jennings touch, looking at everyday events with a fresh, unpretentiously poetic viewpoint. The third was more conventional, aimed at presenting information about the importance of non-military shipping for the war effort. All three films, along with a dozen others, are available on the first volume in the BFI’s region-free DVD edition of Jennings’ complete films.

I also saw Edmond T. Gréville’s Menaces (1940). Its story of impending war is what David would call a network narrative, set among the residents of a cheap Parisian hotel–a sort of low-rent version of Grand Hotel. Although most of the stories are not directly about the war, its threat hovers over them all. Perhaps the stand-out is Prof. Hoffman, a disfigured emigré German war veteran (Erich von Stroheim) who gradually realizes that once war breaks out, he will be an enemy alien in the country he considers home. (The film is available on a region 2, unsubtitled French DVD.)

Menaces was the last film I saw at this year’s festival, and now I look forward to being able to report in tandem with David at next year’s!

Once more we thank the Ritrovato team (especially Marcella Natale), led by Peter von Bagh, Guy Borlée,and Gian Luca Farinelli, for their visionary achievements. They have changed our conception of what a film festival can be, and they have led us to a deeper and wider appreciation of the glories of cinema.

[July 19: Thanks to Antti Alanen for pointing out that Saul and Jonathan Turell’s name has only one r. It’s spelled indiscriminately all over the internet with one r or two, so thanks also to Brian Carmody of Criterion for confirming that Turell is correct.]

[July 29: Guy Borlée has kindly sent me links for some of the festival events that have gone online at Vimeo since I posted this entry. There’s a set of all the lectures given during the week, including the Peter Becker and Jonathan Turell presentation on the Criterion Collection that I describe above (direct link to the Criterion session here). I mentioned Kevin Brownlow’s introduction to The Iron Mask, but he did a whole presentation on Allan Dwan as well. You can also watch the DVD awards ceremony.]

Mixing business with pleasure: Johnnie To’s DRUG WAR

Drug War (2012).

DB here:

At first glance, Drug War (2012) seems an unusual film for Johnnie To Kei-fung and his Milkyway Image company to make. For one thing, this Mainland production lacks the surface sheen of To’s Hong Kong projects. Shot in wintry Jinhai, a northern port city, and in the central city of Erzhou, it presents stretches of industrial wasteland and bleak superhighways. As a result, To’s characteristic audacious stylization gives way to a bare-bones look. The saturated palette of The Longest Nite (1998) and A Hero Never Dies (1998) is gone, replaced by metallic grays and frosty blues. Hong Kong heartthrob Louis Koo, rapidly becoming To’s jeune premier, is bluntly deglamorized—first glimpsed spewing foam as he tries to steer his car, then moving through the film with a blistered face and a bandaged nose. The noir-flavored Exiled (2006) made its steamy Macau locales seem exquisitely somber and menacing, but Drug War’s early scenes in a hospital have a mundane, documentary quality. Little in To’s earlier work prepares us for the grubby scene of drug mules groaning as they shit out plastic pods of dope.

Of course it’s a crime story, the genre in which To and his writer-producer collaborator Wai Ka-fai have gained most acclaim. More specifically, it’s a police procedural, a mode they have worked skillfully with Expect the Unexpected (1999) and Mad Detective (2007). Those, like most cop movies, thread the personal lives of the investigators into the cases they’re running. Drug War, though, gives us no glimpse of the cops off-duty. The result presents our officers as strictly business: no wives, kids, or civilian pals distract them from their mission. In this respect, the film’s closest analogue is probably PTU (2003), but even that showed its patrolling cops in more camaraderie and clashes than we get here.

True, there are brief moments of comradeship, as when Yang offers money to help the cops from Erzhou, and her colleagues chip in. A marvelous shot juxtaposes one cop’s cash with the video stream of the burning bills in the ceremony honoring Timmy’s dead wife and her brothers.

Yet the result humanizes the crooks more than the cops. Timmy mourns his family; we don’t know if Captain Zhang has one.

The concentration on routine and tactics is due partly to the action’s compressed time frame: the seventy-two hour pursuit of the drug gang permits no rest. In addition, made chiefly for the Mainland audience (with Mainland funding), Drug War was subject to censorship that’s more stringent than that in Hong Kong. It may be that To, Wai, and their screenwriting team were cautious about integrating personal lives into their plot. Exploring the officers’ off-duty frailties and failures might have made censors fret. And of course the emphasis on selfless officers sacrificing their personal lives sends a positive ideological message.

I think that the film benefits in other ways from skipping what Ross Chen calls “cop soap opera” and focusing relentlessly on the central cat-and-mouse game. Zhang’s investigation becomes engaging for us thanks to well-honed Milkyway narrative maneuvers: a focus on suspenseful strategies and unexpected countermeasures, the weaving together of various destinies, a fascination with doubling and mirroring, surprising genre tweaks, and unusually laconic signaling of story information. Beneath its drab, almost generic surface and its apparently prosaic account of police procedure, Drug War offers a typically engrossing, off-center Milkyway experience.

And yes, gunfights are involved. But even those are not quite business as usual.

Live or die, I’ll be with you

After a prologue in which a vomiting Timmy Choi Tin-ming crashes his car into a restaurant, we see several lines of action converging at a highway tollbooth. A truck driven by two drug-addled men pulls through, followed by two more men in a muddy red sedan. Soon an overheating bus pulls up. Panicking, the drug traffickers inside make a run for it before they’re brought down by highway officers and Captain Zhang Lei, who has been working undercover on the bus. The mules are taken to a hospital—the second convergence point—and there Captain Zhang notices that Timmy, borne by on a gurney, has burns typical of a drug explosion. Zhang and female officer Yang Xiaobei visit the site of Timmy’s crash, where they find his cellphone. Its mysterious call queue launches their investigation.

If you haven’t yet seen the film, I hope that the preceding has whetted your interest. From now on, I’m afraid I must indulge in what we in the trade call spoilers.

The tollbooth confrontation, it turns out, is a sting operation by which Zhang can nab the traffickers he has infiltrated. The truckers who pass through at the same time are bringing ingredients for Timmy Choi’s local meth factory, and the red sedan is carrying cops who’ve been tracking them. When Zhang and Yang find Timmy’s cellphone, they find dozens of missed calls from the truck drivers, and this enables them to connect Timmy with the shipment. His lab has exploded, killing his wife and her brothers. He escaped but suffered the burns and nausea we saw at the outset.

To escape the death penalty Timmy offers to turn snitch. The rest of the film will intercut among various lines of action: the truckers and their pursuers, the cops using CCTV cameras to track the crooks, and Zhang’s efforts to use Timmy to infiltrate the ring. Zhang’s strategy takes him up the chain of command. There is the laughing Jinhai smuggler HaHa and his wife, who are trying to become drug distributors by means of the port they control. They are wooing the cokehead Li Suchang, his superior Uncle Bill Li, and the real bosses, a Hong Kong gang headed by Fatso (Milkyway regular Lam Suet). Timmy, who knows them all, is positioned as go-between. As with many Hong Kong films, a hierarchy of villains permits a cascade of meetings, showdowns, chases, and chance encounters. Through it all, the question persists: Can Zhang trust Timmy to stay bought?

The first third of the film centers on Zhang’s daring scheme to penetrate the gang. Since HaHa and Li Suchang (called Chang in the English subtitles) have never seen one another, he forces Timmy to set up two meetings. The meetings are timed so that Zhang can impersonate Li in the first meeting and then play HaHa in the second. The result is a pair of virtuoso scenes I’ll go into shortly.

The central chunk of the film follows Timmy’s efforts to get a fresh load of dope for Zhang’s deal. His source is another of his factories, this one staffed by a family of deaf-mutes (a typically perverse Milkyway genre tweak). This section culminates in two intercut police raids: one, a painless seizure of HaHa and his wife, the other a bloody shootout in the factory. The two mutes in charge escape through a hidden passageway, a ploy that renews Zhang’s distrust of Timmy. Timmy vows that he didn’t know about the escape hatch.

The film’s final third introduces the Hong Kong gang directing Uncle Bill from behind the scenes. The film’s first two sections have emphasized the cops’ ability to track the gang with public surveillance cameras and minicams secreted in hotel suites and in the meth warehouse. Now we learn that the gang has its own technology. Hidden microphones and wireless recorders allow gang members to listen to conversations. Fatso feeds dialogue to Uncle Bill in his negotations with Zhang/HaHa. In their final rendezvous at a nightclub, Zhang discovers the ruse and uses it as an excuse to finalize the deal. But when the Hong Kongers demand a night out just for themselves, Captain Zhang must let Timmy go off with them and trust him to deliver them to him the next day.

Timmy betrays everyone. At the climax all the forces in play converge once more, this time outside a primary school. Cars bearing police surround the vehicles carrying the gang. Even the truckers are summoned by Timmy, and eventually the deaf-mutes show up too. Timmy tears off the wire he’s wearing, tells the gang that it’s an ambush, and launches an all-out firefight. While cops and crooks blast each other, Timmy slips into a school bus to hide from the barrage.

The gang is cut down, but so too are the police, including Yang. Even our protagonist Zhang is fatally wounded. Hong Kong aficionados will find here echoes of the pitiless climax of another Milkyway policier I probably should not specify.

The film’s epilogue, like the prologue, centers on Timmy in extremis. In prison he’s strapped down for lethal injection while he babbles the name of every dealer he knows, hoping somehow to save himself from execution. He fails.

Perhaps the most memorable image in the film’s final moments comes a bit earlier, at the end of the gun battle. Timmy brutally finishes off Captain Zhang, only to discover that Zhang has handcuffed his wrist to Timmy’s ankle. Timmy is captured frantically dragging Zhang’s corpse around the street, fulfilling Zhang’s warning after the ill-fated factory raid: “Live or die, I’ll be with you.”

Playing parts

Within this broad movement toward giving Timmy his punishment, at horrendous cost to the forces of law, To and Wai have built fine-grained scenes that swerve the conventions of cop movies in typical Milkway directions. The chief example involves large-scale repetition. During the first section, Zhang goes undercover, pretending to be a gang member. The subterfuge is given a twist: Zhang impersonates Li Suchang in his meeting with HaHa, then he impersonates HaHa in his meeting with Suchang. Once more a Milkyway film finds tricky drama in symmetry and doubling.

The first impersonation goes more easily, but it gets a healthy dose of suspense. Zhang plays Li Suchang as a cold, impassive negotiator. He barely speaks in response to HaHa, who lives up to his name by supplying a stream of chatter and guffaws. He’s not as dense as he might appear, but Zhang has little trouble intimidating him. The problem is that the mini video camera hidden in Zhang/Li’s cigar case is first blocked by food on the table and then arouses the curiosity of HaHa. The tension rises as HaHa examines the case, but Timmy nonchalantly rescues it. His intervention reinforces our sense, in this stretch of the film, that he is cooperating smoothly with the police sting.

Once the charade is over, the film’s narration increases the suspense by the tight timing of the next meeting, which takes place only minutes after the first. Zhang and Yang, who will be playing HaHa’s wife, must change clothes swiftly and prepare cameras to record the deal. The real Li Suchang goes upstairs with Zhang and Timmy just as the real HaHa and wife saunter out of the other elevator: The shot sums up the charade Zhang has engineered, as well as the plot’s mirror structure.

The second encounter ratchets up the tension. Zhang and Yang imitate HaHa and his wife, whom they’ve watched moments earlier; they even repeat lines spoken by the real couple in the previous scene. But Li Suchang is a more aggressive bargainer than HaHa and offers Zhang/HaHa some cocaine. The real HaHa claimed never to have touched the drug, so Zhang/HaHa declines. But Li insists, so the policeman must snort a line. This induces a good deal of uneasiness, which is upped when Li insists he take another hit. Zhang/HaHa obliges and becomes woozy. When Li demands that he snort a third line, Timmy again intervenes and asks that they proceed with the deal. Li relents and they make an appointment with Uncle Bill.

After Li Suchang leaves, there follows a chilling scene in which Zhang goes into drug shock, collapsing to the floor and twitching frantically. Timmy explains what the other cops must do to save him, and by following his commands they revive Zhang. Again Timmy seems firmly on the side of the police. But Zhang still wonders: Did Timmy secretly signal to Li? His mistrust will expand when the deaf-mute factory workers elude the police through an exit that Timmy didn’t mention.

The motif of doubling, a To/Wai staple, runs through the movie: two truckers, two cops tailing them, two deaf-mute killers, two raids, two traffic encounters with the gang, two times that Zhang must trust Tommy and release him. Even the climax consists of not one but two gun battles, the first in front of the school, the second in a nearby street. But the scenes in which Zhang plays both parties in a drug deal serve as the most audacious instance, and a fine example of Milkyway’s gift for reimagining basic conventions of the crime film.

Milkyway’s rule of one

In Planet Hong Kong 2.0, as well as in my discussion of Mad Detective on this site, I suggest that despite all this obsessive doubling, Milkyway films tend to refuse the redundancy that crime movies usually demand.

One instance is the gradual revelation that in the opening, the bus overheating at the toll booth is part of a police trap. Not only is Zhang aboard (sporting a Stetson), but the ticket taker is Officer Yang and the driver (merely glimpsed) is one of Zhang’s men. Since the incident isn’t referred to as a sting afterward, we must realize on our own that this sequence furnishes an abrupt introduction to the police unit’s efficiency and farsightedness.

Another instance is a little less cryptic but has longer-term consequences. The police are preparing for the double masquerade, and Zhang lets Timmy pick out appropriate outfits for them to wear. In a scene lasting only forty-five seconds and ten shots, the emphasis is on Timmy’s careful selection of suits—presented, as we might expect, in imagery of pairing.

While this preparation is going forward, To inserts a shot of hands crushing aspirin tablets into powder.

Later we see that Officer Yang is filling a flask with the powdered aspirin.

What’s going on here? Another sort of film would have inserted dialogue something like this: HaHa hasn’t met Li Suchang, but he’s probably heard that he’s a druggie. He’ll expect me to use coke. If he offers, I’ll tell him that I use only my own. We’ll prepare some fake stuff for me to bring in a flask. And this would have been a clear setup for what will in fact happen in the first meeting. But we don’t get such a setup. Moreover, at this point Yang’s action is even more cryptic because we don’t yet know about Suchang’s addiction, which Zhang is planning to mimic. Yang is preparing a protective measure against a threat we will only learn of later.

The Milkyway writing team often treats story points in this peremptory way. If the Hollywood rule is “Tell the audience every major point three times,” To and Wai often assume that one mention is enough, and even that can come before we’re in a position to appreciate it. Indeed, Zhang’s scam depends completely on the fact that HaHa and Suchang have never met, but that premise is told us on only one occasion, and it’s not given much emphasis.

Again, we could play Hollywood scriptwriters and let Zhang and Yang huddle to explain how they will exploit the fact that the two gangsters can’t recognize each other. But the Milkyway team skips all that. The plan is devised offscreen. We next see Zhang and Timmy picking their wardrobe and Yang preparing the phony cocaine.

In the prologue, we have gotten another roundabout piece of foreshadowing. As Timmy’s car careens down the street, a single shot is presented as the view of a surveillance camera.

A more orthodox film would then cut to a Network Operations Center where concerned officials are watching traffic. But To simply cuts back to the car, where Timmy’s cellphone falls to the floor. Only after Timmy becomes a person of interest to the police do we see investigators re-running CCTV footage of the car. The one video shot has been a hint about how the police will build up their knowledge of Timmy. More broadly, it prefigures the importance of police video surveillance of the gang throughout the film.

Most laconic of all, I think, is the rather complicated scene taking place at a traffic light. The transfer of an important valise, containing money or drugs, is one of the most hoary conventions of the cop thriller. Director To makes it the occasion of a crisscrossing geometry and barely noticeable hints about Timmy’s ultimate aims.

Waiting at the light on the way to a meeting, Zhang as HaHa gets a call from Suchang and Uncle Bill, in a Mercedes sedan waiting behind them. There’ll be no meeting; a deal will be done right here. Zhang’s team is spread out in other vehicles backed up at the light.

But when Zhang as HaHa picks up a parcel to deliver to a white van further along the line of cars, To’s camera coasts rightward to show a dark van waiting in the next lane. We aren’t shown who’s in it. Soon, as Zhang transfers the bag to the van, we see yet another vehicle at the front of the line, and over his shoulder we see a woman inside.

Cut to inside that vehicle, where the woman, the driver, and a fat man in the back seat sit impassively.

Within the plot, the scene functions as Bill Li’s effort to determine whether he’s being set up. The transfer turns out to be a fake, aiming to confirm that Timmy has not turned snitch. If his associates are undercover cops, they are likely to reveal themselves here in order to make a bust. That would fail, because the bag Zhang ends up with carries only imported cigars.

Beyond its function as a test, the traffic stop plays a crucial narrational role. Through mere glimpses and without anything being prepared for, we’re introduced to the Hong Kong gang that will play a commanding role in the last third of the film. The subterfuge is that we haven’t yet been told that there is such a gang; at this point, they are simply oddly emphasized passengers in adjacent vehicles. A more traditional plot would have included an earlier scene in which the police identify the Hong Kong suspects and provide their backstory. Then, seeing them at the intersection would satisfy us that we were putting the story together. Instead, working with almost no dialogue, using the traffic backup as another convergence point, To and Wai have evoked a strange uneasiness. Who are these people, and why are we seeing them?

Immediately after these shots of adjacent vehicles, another dark van opens and a passenger sets a carrying case on the street. Yang in her guise of HaHa’s wife fetches that case. Then, in a slippery set of POV shots, Timmy turns and looks back at other men in vehicles, and then at Uncle Bill and Li Suchang, who seem to evade his stare.