Archive for the 'Directors: Petzold' Category

Vancouver: First sightings

Big Tech as Pac-Man: The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

DB here:

Every festival has had to adjust to COVID-19. This year the venerated Vancover International Film Festival continues with some in-person events at the VIFF Centre and the Cinematheque, but most of the screenings are done remotely. The streaming resource is available only in British Columbia and is a wonderful option for regional cinephiles.

Over the next two weeks, we’ll continue our annual tradition of covering some of the outstanding films mounted by this superb festival. As usual, we hope to guide local viewers while the event is in progress and to signal readers about upcoming releases in their territories.

Deep dives

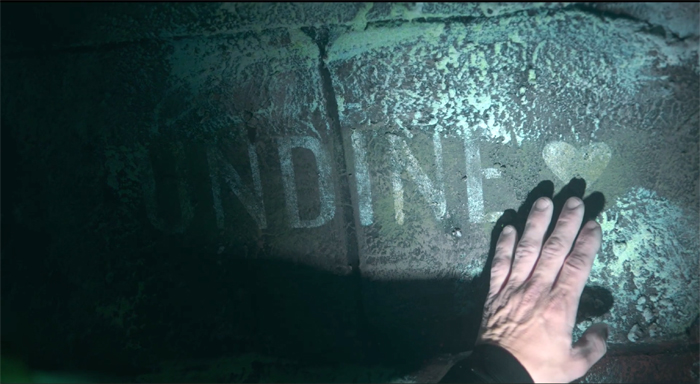

Undine (2020).

No lyrical drone vistas, no establishing shot, no title telling us where and when we are, no voice-over trying to lure us in. Just bam, here it is, deal with it. Any movie that starts with a reaction shot in OTS (over the shoulder) of a fiercely downcast woman gets points automatically. The fact that she goes on to threaten to kill the man she’s talking to is just a bonus.

That threat, made by the protagonist of Christian Petzold’s Undine, is about the only hint that she’s capable of homicide. She seems otherwise a well-adjusted young woman free-lancing as a guide in Berlin’s Urban Development Center. As in other Petzold films, thriller conventions are invoked but suspended while a deepening personal drama emerges. At first, we tag along with Undine in her rebound-affair with Christophe, an engineer specializing in repairing underwater equipment. All is going well enough, but there are signs of trouble, particularly a near-death experience in a lake. Then, after the midpoint, tension ratchets up with two quick twists that put new pressure on Undine to take violent action.

Sorry to be so oblique, but this is one of those movies with a real plot, and since it’s eventually coming to the US, I’m avoiding spoilers. Admittedly, the last twenty minutes take off into new territory, and I found myself unable to know what to expect next. (It’s one of those movies that seems to end several times. That is often a good thing.) But the unruffled precision of Petzold’s direction, the thriftily paid-out backstory, and his gift for suspenseful storytelling mitigate the quasi-supernatural tint of the twists. I tend to see them as GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema), ambiguous moments that may flow from the characters’ imaginations.

An undine is a water nymph, the heroine’s lover is a diver, her job is to lecture on the rebuilding of Berlin over the years, and his job is to explore a submerged city (which hosts a slab bearing her name). All this was for me a reminder that ambitious directors can invest genre conventions with poetic lyricism. Admirers of Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and Transit (2018) will need no urging to visit a film I found completely absorbing.

A film from two billion years from now

Last and First Men (2020).

On the visual level, Jóhann Jóhannsson’s Last and First Men is a good example of what we call “abstract form” in our book Film Art. The filmmaker builds a film out of patterns of sensuous visual qualities. Everyday objects can yield these qualities (our example is Ballet Mécanique), but abstract form can also be found in unusual, even unidentifiable sources.

That’s what we get here. The shots reveal structures and textures in immense, brutal constructions of metal, stone, and cement. Are they sculptures? Totems of some bizarre religion? Remnants of blasted modernist buildings? Fragments of space ships crashed to earth? The moving camera reveals their shapes, textures, and off-kilter strains for symmetry. You lose all sense of scale: these might be the size of dinner tables or tabernacles. Most are set against the sky, alternately misty or searingly bright.

No story connects our views of these strange monuments. On the soundtrack, though, a woman’s voice recounts the history of the future. After two billion years, the narrator represents the “eighteenth species” of humans, and via telepathy she informs us of the impending end of human life on Neptune.

We never see any of those events, just the ruins calmly surveyed by the camera. Almost never does the commentary sync up with the shots. The woman’s account of future humans might at first seem to match the carved, staring blocks we see, but she goes on describe them as furry or translucent.

The disparity between description and depiction emphasizes the gap between tracks.

For most of the film, then, we have a split. The image track explores abstract, nonnarrative form. The soundtrack supplies a narrative, actually a Very Grand Narrative. The text, it’s revealed in the credits, comes from Olaf Stapledon’s 1930 science-fiction novel, Last and First Men.

There’s yet a third layer. Jóhannsson, a brilliant composer who died in 2018, gave us memorable concert music and film scores (Sicario, Arrival, The Miners’ Hymns). Along with the voice-over we hear a sometimes radiant, sometimes jarring orchestral accompaniment created by Jóhansson and electronic composer Yair Elazar Glotman. The music doesn’t cooperate much with the voice-over. As the commentary proceeds with a businesslike dryness, the music often flows and eddies on its own course.

The fact that the three channels of picture, voice, and music seldom converge actually sets your imagination free. There’s no need to see the images as illustrating the text, or the music as operatically enhancing either one. We’re allowed to keep the realms separate, or to test obscure correspondences. We can, for instance, see the expressive qualities of the shots as enduring remnants of human will–eccentric, obstinate, and obscure as it can be. The music’s alternation of drone passages, scraps of choral lyricism, and ominous rumbles might seem to chart humans’ up-and-down fate in the late Anthropocene. The narration, recited by Tilda Swinton, adds a quality of stoic dignity to the mix. And you’re invited to try out metaphors, as when cavities in what seems to be an elongated cathedral suggest eyeholes for staring across space.

The disparity of channels is enhanced by another mystery I haven’t seen mentioned in reviews. The images betray their origins on 16mm film. There are light leaks on the frame edges, specks of white suggesting dust on the negative, and even bits of grit and hair in the aperture. Perhaps you can see the hair snagged in the upper right of the image below.

These flaws have not been digitally removed. Indeed, the film’s opening moments linger on black frames flecked with white dust, priming us to watch for faults in these images.

The effect is to add an archaic quality, as if this is all found footage from long before the end recounted on the soundtrack. Since the narrator tells us that humankind goes through many near-extinctions until the big one, these relics may be from one of those future collapses–or, perhaps, from our own past, remnants of a calamity we’ve forgotten. The text speaks of “the debased rites of your religions long ago,” and those big-eyed humanoids are reminiscent of Australian aboriginal art.

In all, it’s a bleakly beautiful experiment. The film premiered with live orchestral accompaniment in the 2017 Manchester International Festival, and it must have been hypnotic. The film and soundtrack are now available on a CD/Blu-ray combination, as well as on vinyl.

Meet the New New Boss, same as the Old New Boss

The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

The scathing 2003 documentary The Corporation took seriously the idea that corporations were persons. Their behavior, considered clinically, is that of a sociopath. Now Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott’s followup shows how the 2008 financial crisis provoked corporations to rehabilitate. Hip CEOs admit the existence of racial bigotry, income inequality and the failures of conservative government. The solution? More corporate power. Did this make them any less dangerous?

Nope. Multinationals shape government policy as vigorously as ever, especially in the era of Trump and other demagogues. But the corporations’ new message is soft power. Posing as socially committed, emphasizing stakeholders as well as shareholders, Big Business is (a) trying to convince consumers that it’s on their side; and (b) arguing that the New Corporation will correct the shortcomings of government policy through privatization. In other words: We’ve learned our lesson. We get it. So let us run things. Besides, what choice do you have?

Bakan and Abbott shrewdly show that this ploy neatly fits an updated clinical symptom of the sociopath: “Use of seduction, charm, glibness, or ingratiation to achieve one’s ends.”

The film begins with a fascinating visit to the Davos Forum, where air-kissing one-percenters solemnly assure us that everybody wins when a corporation acknowledges the public good. The star player is Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase. Having helped crush American cities in the financial crisis (and paying a derisory $13 billion fine), he is now playing rescuer by supporting the rebuilding of Detroit, to the benefit of his company’s image. The film goes on to trace how the public face of caring executives is belied by business as usual, most savagely British Petroleum’s catastrophes in Texas City and at Deep Water Horizon.

Bakan and Abbott marshall a great deal of evidence to show how the plutocracy, and especially those in the digital technology sector, have turned a market economy into a market society. For us, the role of worker-consumer redefines the other dimensions of civic life. You work without union protections and scramble to keep up. You give your personal information to Facebook, Google, and Amazon in exchange for convenience and lower costs. (The old adage holds: If something is free, the product is you.) Schools, postal delivery, war, water, and relationships are all ripe to be rendered as private enterprise. With AI algorithms, the customer-customized milieu of Minority Report is already here.

Talking heads, from Chomsky and Robert Reich to Diane Ravitch and Vandana Shiva, offer pithy critiques, and footage garnered from around the world illuminates each of the points in the Corporate Playbook. As a counterweight, later portions of The New Corporation show some pushback. Katie Porter poleaxes Mr. Dimon in a House hearing, and we glimpse AOC in her usual passionate eloquence. Still, the emphasis falls less on pols and more on citizens who struggle against corporate power.

Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaign are shown to be as important to the left as the Tea Party was to the right. The filmmakers give special attention to the efforts of many tough, idealistic people to run for public office. As one commenter puts it, “Even in the worst situations, people always fight.” In a remarkable passage, a dopy prankster from The Corporation is shown to have become a proud progressive after seeing the first film and joining the Sanders campaign.

The film is startlingly up-to-date, incorporating events around the George Floyd atrocity and the Black Lives Matter street actions. Some will say that the late sections drift a bit from the film’s core message of analyzing the fake social concerns of the New Corporation. But income inequality and environmental destruction, central drivers of new social movements, are invoked in corporate PR as vital concerns for companies’ new image, so the final sequences don’t seem to me tacked on. They show what real social engagement, as opposed to panting coverage in Forbes, looks like.

Where do you start? someone asks in Tout va bien. The answer: Everywhere at once. I think The New Corporation indicates that this might just work.

The three films I’ve discussed are exemplary of the strengths that have characterized the Vancouver festival for its 39 years. Here you can plunge into international auteur cinema, unusual experimental work, and documentaries committed to our noblest aspirations. Programmers Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and their colleagues scour the world for provocative films, and the results have taught Kristin and me lessons about cinema we wouldn’t have learned otherwise. It’s worth noting that VIFF’s welcome to Canadian cinema has always been fruitful: The New Corporation, like its predecessor, is a British Columbia production and is featured in the festival’s ongoing True North series.

Fourteen years ago I wrote that Vancouver was the very model of a regional festival, at once deeply local and unpretentiously cosmopolitan. It still is. Take that, corornavirus! Nothing stops dedicated film lovers.

Thanks to Alan Franey, Jane Harrison, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

A sensitive review of Undine is offered by David Hudson at the Criterion Daily.

A note on Last and First Men: In watching the film, I found myself constantly asking if these structures really existed, or whether they were CGI creations or miniatures or objects purpose-built for the film. Some reviews have revealed their secret identity, and knowing what they are does raise some interesting thematic implications. But I’m refraining from telling you because I think your first encounter with the film ought to include that mystery about what exactly you are seeing. If you want to know what they are, Google is at your service. There’s also this spoiler-filled behind-the-scenes video.

Jennifer Abbott has another documentary in this year’s festival: The Magnitude of All Things. I look forward to it.

Undine (2020).

Back on the book beat

Phoenix (Christian Petzold, 2014).

DB here:

One of my undergrad professors told me: “Bordwell, you have to decide whether you’re going to be a reading man or a writing man.” Professors of the male persuasion talked that way then. When I said I wanted to be both, my mentor puffed his pipe. He really smoked a pipe. He said: “It’s damn hard.” This kindly man knew English Renaissance drama and poetry practically by heart but never wrote a book.

I start to see what he means. For some decades, I managed to read a fair lot and write a decent amount. You’d think in retirement it would get easier. But I have too many interests and projects, and publishers dump a heap of intriguing items on the market every week. The months go by, the books pile up on the side table and on the floor, and I try to keep up. I really do. I’m always behind.

So at intervals I stop obsessing about 1910s cinema and 1940s Hollywood and Rex Stout and how best to think about film form and style, and I swerve to what colleagues are discovering. Turns out, quite a bit. What better time than a plague to catch up?

Flooding the zone

What’s it like to live across the street from a prolific polymath?

For twenty-five years we had as neighbor James W. Cortada, a genuine intellectual range rider. Trained as a scholar in Spanish diplomatic history, he finished his Ph.D. in one of the worst hiring years: 1973, the same year I came out. I was lucky to find work, but Jim took a job selling IBM computers. Eventually he became an executive specializing in innovation and management.

But he was also a compulsive researcher and writer. While holding down a desk job and supervising staff and toting PowerPoints around the world, he managed to publish books in a host of areas. He was a guru of Total Quality Management, producing books and yearbooks on the subject. He also became a premiere historian of computer technology, with such classics as Before the Computer. What I like about this book is the way it integrates study of the tools and machines with examination of the office-based practices of sorting, bookkeeping, and other mundane activities. Unbelievably, Jim continued his graduate interest in Spanish political history. Along the way he wrote a research manual (History Hunting), turned out a study of 9/11’s impact on business, and edited with Alfred Chandler a massive book on information in US life.

Jim writes any size. He has produced The Digital Hand, a magisterial trilogy surveying the use of computers in American life. What about the rest of the world? That’s covered in The Digital Flood, another showstopper. Then there’s IBM: The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon, which is the definitive account of a corporate behemoth, with access to information only an insider could obtain.

Not to mention (so I’ll mention it), Jim’s more or less single-handed creation of a whole discipline: the history of information. The ideas are there in early works, but the first crystallization was the stupendous All the Facts, a sweeping survey of how Americans passed along data–not just in business but in cookbooks, diaries, maps, and other vessels of knowledge.

Since 1971 Jim has authored or edited over seventy books. Retirement has revealed what a slacker he was before. Between March 2019 and March 2020, he published four volumes. He also found time to head our neighborhood association, contribute many articles to professional journals, play with his grandkids, and banter over burritos at El Pastor (before lockdown).

You haven’t lived until your neighbor drops by at the cocktail hour with the cheerful greeting, “How many words did you write today?” Fortunately, he’s utterly generous. Jim reads everything I show him, immediately giving me helpful advice. He’s just an all-around intellectual who, because of the 70s job market, wound up in a non-academic line of work. He shows what you can do if you have brains, pluck, and a hunger to find things out. Long before our millennial “knowledge workers,” he showed what a rigorous university education could bring to corporate culture.

Probably the most immediately significant items in Jim’s recent output are two books he wrote with William Aspray. From Urban Legends to Political Fact-Checking: Online Scrutiny in America, 1990–2015 is a scrupulous in-depth account of how fake facts and the debunking of same stretch back to the very origins of the Net. The book digs back to pre-Internet online legends circulated on Prodigy and America On Line, chief among them being the infamous Willie Lynch letter purporting to instruct planters how to discipline their slaves. The bulk of the book shows how over twenty-five years, rumors and half-truths become depressingly long-lived.

In charting the surging infection of lies, pranks, and blatant dumbassery, the authors also show how snopes and other fact-checking bodies try to catch up. Still, I found the persistence of even the stupidest ones discouraging. Trump’s 2015 assertion that he saw Arabs in New Jersey celebrating 9/11 is an example of the “Celebrating Arabs” meme that popped up immediately after the Trade Center was hit. Asked about it, he asserted: “It was on television. I saw it.” That’s all you need.

In charting the surging infection of lies, pranks, and blatant dumbassery, the authors also show how snopes and other fact-checking bodies try to catch up. Still, I found the persistence of even the stupidest ones discouraging. Trump’s 2015 assertion that he saw Arabs in New Jersey celebrating 9/11 is an example of the “Celebrating Arabs” meme that popped up immediately after the Trade Center was hit. Asked about it, he asserted: “It was on television. I saw it.” That’s all you need.

Fake News Nation: The Long History of Lies and Misrepresentation in America is broader and aimed at a more popular audience. It offers eight historical episodes as case studies in rumor and deceit. The earliest instance is the presidential election of 1828, which blended corruption, sex, and racism in an intoxicating cocktail: “General Jackson’s mother was a COMMON PROSTITUTE. . . . She afterwards married a MULATTO MAN, with whom she had several children, of which member General JACKSON is one!!!” Nice to know triple exclamation points aren’t an invention of tweens and trolls. The book surveys conspiracy theories around the assassinations of Lincoln and Kennedy, mythmaking in the Spanish-American War, and disinformation in controversies about Big Tobacco and climate change. It’s a completely fascinating read.

It’s also fairly dispiriting. It brings out the Mencken in me, admittedly never far from the surface. The books suggest that the venality of hoaxers, the credulity of the multitude, and the social incentives to hide the truth and spread lies don’t promote a public demand for accuracy and nuance. What we see now, in the Republicans’ current attempt at a fascist takeover of our civil society, is the implementation of Steve Bannon’s suggestion to “flood the zone with shit.”

It’s not that the wacko alternatives carry much weight, though they do play to darker desires. More important is the sheer firehose fusillade of preposterous claims. Who can keep up? Nuanced fact-checking seems only to add to the swirl of uncertainty. Are coronavirus cases being undercounted? Overcounted? Confusion and overload are central to the plan. Instead of “Drain the Swamp,” the motto is “Swamp the Drain.”

So books like Jim’s and Mr. Aspray’s buoy us as we paddle to keep our heads above the waves of sludge. Meanwhile, Jim is eight chapters into his next opus.

Techbeat

Jim’s work as a historian of business technology reminds us that tech is a part of film history too. But for many decades, materials, machines, and tools weren’t sufficiently reckoned into the study of film. Scholars of early cinema were, I think, the first to examine the standardization of equipment and film stock; Gordon Hendricks’ dauting Edison Motion Picture Myth (1962) situated the emergence of moving-image technology in the context of Edison’s corporate strategy. Eventually, by the 1980s, people were considering the role of camera and lens design, lighting rigs, film stock, and camera carriages in shaping film style. Our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema was one effort in this direction.

Since then many scholars have turned to the histories of image and sound technology to clarify their research questions. Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood is a model of how to integrate information about labor practices, technology, and industrial organization with the results in the finished film. He shows, for instance, that the menu of options available to filmmakers in staging and cutting scenes had knock-on effects in choices about camera mobility, which in turn was facilitated by particular dollies, cranes, and other gadgets available.

Since then many scholars have turned to the histories of image and sound technology to clarify their research questions. Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood is a model of how to integrate information about labor practices, technology, and industrial organization with the results in the finished film. He shows, for instance, that the menu of options available to filmmakers in staging and cutting scenes had knock-on effects in choices about camera mobility, which in turn was facilitated by particular dollies, cranes, and other gadgets available.

His analyses of scenes from 1930s and 1940s films, both classic and obscure, train the reader in what to watch for. In all, it’s a persuasive meshing of functional explanations of style with causal accounts of what goes on behind the scenes–not least, the sheer sweat of pushing dollies and following focus. He draws an enlightening contrast with the brain-work of producers, screenwriters, and directors.

The work of production is bodily. The actors move their arms and legs and torsos, and the grip and operator move theirs. Each must anticipate the others’ gestures, like dancers in an ensemble. the Hollywood studio system relied on preproduction planning in order to rationalize production, but the process of filmmaking ultimately came down to craftspeople working together in the moment. One type of collaporation was corporate; the other was corporeal (158).

A graduate of our program, Keating carries forward our respect for filmmaking craft, including its more toilsome routines.

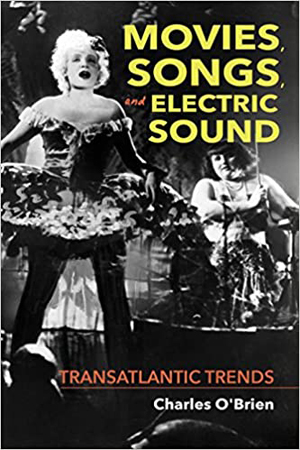

No less sensitive to the concrete demands of technology, and the ingenious workarounds that can be discovered, is Charles O’Brien’s account of the international transition to talkies, Movies, Songs, and Electric Sounds: Translatlantic Trends. Like Keating, he’s studying a body of conventions, here those that arose in the vogue for the international “song film” in 1928-1934. And like Keating, he’s very precise. He measuresg average shot lengths and brings out the implications of how much time is devoted to songs or dialogue.

But this is no simple data dump. O’Brien charts the various strategies in which song sequences allude to the theatre situation and absorb themselves into the ongoing story line. He traces a distinction between the Hollywood song sequences, which were quickly relegated to farces like the Marx Brothers films, and the European sequences, which adapted more varied forms, such as pantomime and verse-like dialogue stretches. The latter strategy was especially common in Germany, partly due to the studios’ commitment to direct sound. O’Brien offers a particularly cogent account of the virtuoso carriage scene in The Congress Dances (1931), which in its joyful excess remains stunning today. (See clip above.)

O’Brien further contextualizes his discoveries by considering broader business culture, such as the market in song recordings and sheet music. All in all, a tight, coherent account of how technological change introduces both functional equivalents of existing techniques and spillover effects–unexpected advantages that artists can exploit.

Shawn VanCour’s Making Radio: Early Radio Production and the Rise of Modern Sound Culture focuses similarly on technology and craft at this period, bringing in other institutional pressures on craft workers making audio artifacts. In fascinating detail, Shawn (another UW alumnus) shows how the separation of body and voice created by radio broadcasts posed many problems for engineers, writers, and other staff. One result was a sort of “practical theory,” a body of ideas about what radio essentially was, alongside particular practices that shaped both technology and dramaturgy.

For instance, everybody recognized the need to dramatize story action with sound effects and music, but paramount was the need to keep dialogue clear. The compromises and trade-offs were debated in trade journals and executed on the airwaves, with fascinating effects on standards of proper audibility. One consequence was the valorization of a “radio voice,” the mellifluous tones suited to the new medium’s demands, both technical and institutional. VanCour shows that these debates were picked up in the motion-picture industry at the period O’Brien investigates. Sometimes, less often than we think, inquiries do converge in fruitful ways.

At intervals of a decade, Paolo Cherchi Usai has rethought the ideas and evidence informing his exploration of silent film. Burning Passions (1991) was a precise manual for archival research. Silent Cinema: An Introduction (2000) was a deeper plunge, taking into account digital transformations that he explored in the contemporaneous The Death of Cinema (2001). Now, he has gone Full Cortada with the massive Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship.

At intervals of a decade, Paolo Cherchi Usai has rethought the ideas and evidence informing his exploration of silent film. Burning Passions (1991) was a precise manual for archival research. Silent Cinema: An Introduction (2000) was a deeper plunge, taking into account digital transformations that he explored in the contemporaneous The Death of Cinema (2001). Now, he has gone Full Cortada with the massive Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship.

This is an encyclopedia that reads like a series of engaging art history lectures. In his opening, Paolo acknowledges the avalanche of new material he faced. More than fifty thousand features and shorts have survived from the years 1894 to 1929, and research has expanded accordingly. He pursues three questions: What was silent cinema thought to be at the time? How may we study it? And why does silent film matter as an expression of culture? These questions are pursued in fifteen chapters bearing one-word titles like “People,” “Building,” “Duplicates.”

No summary can do justice to the world that this book opens up. We learn about the machines, the venues, the processes, and the people. There are floorplans of studios and theatres, comparisons of different color processes (gorgeous), and discussions of how projectionists regulated the speed of the show. The book devotes a whole chapter to theatre acoustics, the use of sound effects and recordings, and even the clapper sticks used by the benshi commentators in Japan. Another fascinating chapter traces the fate of a single film through multiple versions, from camera negative to digital format. Throughout, Méliès’s Trip to the Moon is used as a benchmark to remind us of all the ways that every copy is a unique artifact, a claim that Paolo has advanced consistently over the years.

Silent Cinema is a must-have book for everyone interested in cinema of all eras. Its publication price made it the film-book bargain of the year, but Bloomsbury and Amazon are now offering it on obscenely generous terms. If you’re not a silent fan, this giddy ride can make you one.

Auteurs never went away

The Headless Woman (2008).

At intervals people tell us that we need to stop studying directors and turn instead to Culture or Other Collaborators or some other inputs. Surely the classic formulations of auteur criticism have some problems. Still, it’s terribly hard to shake the idea that a great many films are usefully understood in light of directors’ purposes and plans. Directors play a central role in the production process and under certain circumstances are granted the possibility of building a body of work. We can argue about Roy del Ruth or Michael Bay, but not certain “strong filmmakers” who have, as Andrew Sarris put it long ago, personal visions.

An obvious example is the obstinately eccentric Jacques Tati. In just a few films, he changed our conception not only of film comedy but of the art of cinema itself. How that happened is the subject of Malcolm Turvey’s fine book Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism. Malcolm, who just last week contributed a guest blog on research into neuroscience and camera movement, is a major scholar of cinematic modernism. Here he shows that in spirit Tati is an experimental filmmaker.

An obvious example is the obstinately eccentric Jacques Tati. In just a few films, he changed our conception not only of film comedy but of the art of cinema itself. How that happened is the subject of Malcolm Turvey’s fine book Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism. Malcolm, who just last week contributed a guest blog on research into neuroscience and camera movement, is a major scholar of cinematic modernism. Here he shows that in spirit Tati is an experimental filmmaker.

There’s an extensive body of close analysis on Tati, to which Kristin in particular contributed as far back as the 1970s. Malcolm adds to this with some keen studies of framing, sound, and gag structures. What he brings to the table is the way that distinctively modernist conceptions of humor and comedy find their way into this vaudeville-inspired entertainer. From aleatory gags–apparently random synchronizations of noises and movements–to fragmented and incomplete or unconsummated gags, such as the precarious taffy that doesn’t quite plop off its hook, Tati intuitively reawakens the spirit of irrational laughter that inspired avant-gardists.

Malcolm traces Tati’s lineage back to Albert Jarry, Jean Cocteau, and the avant-garde’s fascination with circus and music hall. Other sources were Chaplin, Léger, and René Clair. In a sort of feedback loop, the avant-garde borrowed from slapstick comedy, while Tati’s cinematic transformation of music-hall numbers into decentered, absurd, or perplexing cinematic sequences revives the anarchic spirit of the modernists. His satire of the postwar managed society sought to make us see the world around us from a potentially subversive angle. The dreary vacation routines of M. Hulot’s Holiday and the opaque surfaces and chilly contours of Mon Oncle and Play Time are disrupted by characters who revel in disruption, and a filmmaker who imagines our daily march easily turned into charmingly clumsy dance. Beneath the paving stones, the beach, went a May ’68 slogan. “His was the quintessentially avant-garde project,” writes Malcolm, “of closing the gulf between art and life” (p. 237).

Tati went his own way, but many of our auteurs are part of larger schools or trends. From almost the beginning of cinema, historians have talked about movements or schools whose members share broad goals or generational sources, but who then can be distinguished by virtue of their particular sensibilities. Such, for instance, is Christian Petzold. One of “the Berlin School” of filmmakers coming to prominence in the 1990s, he has gained fame internationally, particularly with Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and in 2018 Transit. I’m still catching up with his oeuvre, having seen these films at festivals (along with his contribution to Dreileben, 2011), and I’m also roaming among the no less interesting work of his colleagues, particularly Angela Schanelec and Thomas Arslan.

Tati went his own way, but many of our auteurs are part of larger schools or trends. From almost the beginning of cinema, historians have talked about movements or schools whose members share broad goals or generational sources, but who then can be distinguished by virtue of their particular sensibilities. Such, for instance, is Christian Petzold. One of “the Berlin School” of filmmakers coming to prominence in the 1990s, he has gained fame internationally, particularly with Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and in 2018 Transit. I’m still catching up with his oeuvre, having seen these films at festivals (along with his contribution to Dreileben, 2011), and I’m also roaming among the no less interesting work of his colleagues, particularly Angela Schanelec and Thomas Arslan.

All the more welcome, then, is Brad Prager’s monograph on Phoenix in the Camden House German Film Classics series. This is an admirable close reading of Petzold’s film, bringing a range of cultural references to bear on the suspenseful story of a woman returning from a death camp to a husband who, it turns out, has his own guilty secret.

Prager skilfully invokes the citations–Vertigo, Siodmak’s work, American noir–and considers how Petzold’s genre affiliations (he often makes politically inflected thrillers) merge with his examination of trauma in German history. It isn’t easy to do justice to the film’s remarkable climax, which I decline to spoil for you, but Prager manages it. This scene is one of the great fake-outs in recent film, I think, and Prager is alive to all its bleak ironies, including the heroine’s rendition of Kurt Weill’s “Speak Low.”

Phoenix (the book) is a model of compact, probing analysis. I’d be happy to have Prager tackle another Petzold, especially one I just saw and much admire, his first feature The State I Am In (Die innere Sicherheit, 2000), which seemed to me to do for Fritz Lang what Phoenix does for Hitchcock. More generally, Petzold has a pictorial exactitude we seldom see nowadays, and he deserves wide-ranging study.

The New Argentine Cinema wasn’t as cohesive a group as the Berlin School, but there’s little doubt that Lucrecia Martel emerged as one of its singular talents. I remember the jolt of seeing La ciénaga (2001) and immediately taking frames from a 35mm print so we could feature it in Film History: An Introduction (2d ed., 2002). The Headless Woman (2008) at Vancouver confirmed my sense of a major talent, and most recently Zama (2017) confirmed it. Kristin wrote an appreciation from the Venice premiere. It was the best film we saw there and one of the finest of that year.

The New Argentine Cinema wasn’t as cohesive a group as the Berlin School, but there’s little doubt that Lucrecia Martel emerged as one of its singular talents. I remember the jolt of seeing La ciénaga (2001) and immediately taking frames from a 35mm print so we could feature it in Film History: An Introduction (2d ed., 2002). The Headless Woman (2008) at Vancouver confirmed my sense of a major talent, and most recently Zama (2017) confirmed it. Kristin wrote an appreciation from the Venice premiere. It was the best film we saw there and one of the finest of that year.

All the features of a classic auteurism were here (and in The Holy Girl, 2004): persistent themes, distinctive plotting, signature style. These qualities are given full consideration in Gerd Gemünden’s Lucrecia Martel. Gerd has done a thorough job in surveying her career and dissecting the films. He shows that she is especially interested in rendering physical sensation–textures, touch–through evocative images and sounds. Anybody who has seen La ciénaga can’t forget the opening scene’s glimpses of a scummy swimming pool and flaccid necks and groins, let alone the wine and splinters of glass splashed onto a drunken woman’s corrugated chest. The rain in The Headless Woman is no less palpable, while the humid torpor of the colonial outpost in Zama is sticky almost beyond endurance. This tactility makes Martel’s stringent criticism of class inequities even more powerful.

This critical aperçu finds its place in Gerd’s comprehensive account of Martel’s oeuvre. As is usual in the series Contemporary Film Directors (yeah, an auteur title for sure), we get detailed production dossiers, wide-ranging background on literary sources and cultural context of reception, and close studies of the films. There’s also a rich bibliography and an interview with some surprises; for such an elliptical, visually oriented director, Martel claims that oral storytelling is a primary inspiration.

Auteur studies are not what they used to be. Instead of paeans to directorial genius, they can be subtle, wide-ranging discussions of what Eliot called “tradition and the individual talent.” Acknowledging influences, circumstantial pressures, forced choices, opportunities, and the like, our writers can show that some directors still build up films that yield resonant personal expression. Choice within constraints: that’s the story of creativity in all the arts, and the most nuanced auteur accounts can show how that process works in fascinating detail.

Will we still have books as the coronavirus burns its way through our lives? Can publishers survive? Yes, we’re sequestered, and maybe that’s encouraging us to read more; but people will have a lot less money for books. What will entice us to invest in personal libraries?

An encouraging sign is that so many of the books on film here have very fine illustrations, many in color. So thanks to the publishers for understanding that well-reproduced pictures can attract readers as well as document arguments. And Silent Cinema includes a filmography with references to online collections. With books like these, we can correct and expand what my old prof said: You can be a reader and a writer and a viewer. Now we just need time, and safety.

Each of these books represents an integral research project, but all are part of larger research programs too. Jim Cortada’s work is an epic instance, but we find the same trajectory in the film scholars’ careers. As writer, archivist, and filmmaker, Paolo Cherchi Usai has devoted his life to silent cinema. Patrick Keating’s study of camera movement joins his first book on the history of Hollywood lighting. Charles O’Brien has already given us a fine-grained comparison of the conversion to talkies in the US and France. Shawn VanCour is active in archiving sound and is exploring radio’s relation to other acoustic media. Malcolm Turvey’s book on Tati joins his earlier books on avant-garde filmmakers’ conceptions of vision and 1920s modernism in Europe. Petzold’s film is a natural step beyond Brad Prager’s work on Herzog and on visuality in German Romanticism. Gerd Gemünden’s many books include one on German exile cinema and Billy Wilder’s American films.

Kristin’s writings on Tati from the late Seventies are in her Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis.

P.S. 29 May: I just got another volume that chimes with this entry. It’s Marco Abel’s The Counter-Cinema of the Berlin School from 2013, and it’s a very comprehensive and in-depth consideration of this important group.

Trafic (Jacques Tati, 1971).

Hunting Deplorables, gathering themes

The Hunt (2020).

DB here:

I recently participated in a Film Comment podcast with Nic Rapold and Imogen Sarah Smith. It was fun. Yes, The Hunt was involved.

And last month I posted a “blog lecture” for my seminar on Poetics of Cinema. Because it included references to classroom material, I thought it was too insular for general consumption, so I posted it privately. Encouragingly, some of our regular readers wrote to ask about accessing it, so today I’m putting up a more broadly-aimed version. Again, yes, The Hunt is involved.

We like to watch (and listen)

First and fast, some foundations. As Paul Krugman might say, wonkish ones.

Most basically, I’m interested in two questions: How do films work? How do they work on us? The first question, I think, can productively start with filmmaking craft and the norms that filmmakers work with in their historical situation. Within and against those norms, filmmakers create work that blends tradition and innovation. I’m interested in conventions–the conventional side of “unconventional” works, and the unconventional side of more apparently rule-abiding ones. I sometimes say I want to know filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

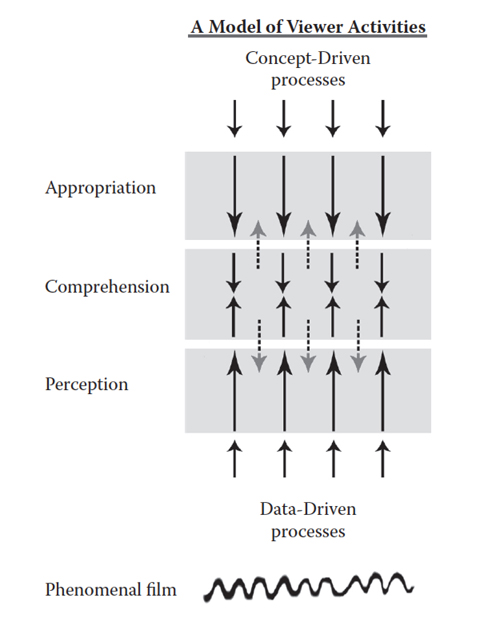

But asking how films work on us has driven me to posit a conception of spectators’ activities. After all, in any art it’s legitimate to try to explain how the design features of a work are shaped to elicit effects, ranging from perceptual and emotional ones to broader effects of comprehension and what I call appropriation. I assume that in every sphere “the beholder’s share” in watching movies is considerable, and active.

Using a common psychological distinction, I’ve argued we can roughly understand this process with a diagram, above.

The activity proceeds both “from the bottom up” via the fast, mandatory, specialized activities of visual and auditory perception. The process works as well as from the “top down” via more deliberative mental acts. Comprehension, typically of story patterns, operates in the middle. So you “just see” a man in tights walking across the shot. Thanks to story comprehension skills you “just see” Batman striding to face off against a crook. Thanks to your wider conceptual schemes, you can appropriate that as patriarchy in action, or the pain of vigilante justice, or a template for an action figure you might buy, or whatever. Where’s emotion? At all stages, I think.

And all these processes seem to me inference-based to some degree. In grasping artworks, even perception has an inferential dimension, going beyond the information given. Patches and contours on the screen are grasped as people, places, and things; sound waves are grasped as speech and music. The process is inferential because these perceptual conclusions are defeasible, as most illusions are. Things might be otherwise than they seem; we bet (fast, unreflectingly) that things are as they seem until other information pulls us up short. Similarly, story comprehension relies on skills of inference we’ve developed since childhood, built partly upon our social intelligence. And appropriation is obviously inferential, building hypotheses about the meanings and uses we can ascribe to film.

Perception and comprehension are strongly shaped by the film’s form and style. But as we go up from perception, the filmmaker’s power decreases and the viewer’s power increases. Viewers wield most power in appropriation, those top-down, concept-driven inferences that pull the film, or at least the viewer’s construct of the film, into wider projects.

Let’s think of appropriation as most basically using the film for myriad personal or social ends. That activity involves, for want of a better term, themes–ideas, categories, dualities, pop-culture memes, right up to wider beliefs about the world. Cultural processes, affecting the lower levels to some degree, are at work here most explicitly.

At this moment, when many people are sheltering at home, they are appropriating films for many purposes–to distract them, to entertain the kids, to learn more about health policy or the effects of pandemics. Fans, I assume, are seizing the pretext to binge on a saga they love, or check out a series they’ve put off. Online critics, pressed to turn in copy, are mustering their new listicles, recommendations of films to watch while we’re in lockdown.

This situation is just a special case of appropriation, of finding aspects of the film that can be recruited for purposes that may or may not accord with the filmmakers’ original intentions. No producer planned for Outbreak (1995) or Contagion (2011) to serve as audiovisual aids during a plague.

As my Batman example indicates, interpretation is a rich instance of appropriation, displaying how resourceful people can be in their inferential elaborations.

I wrote the book Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema (1989) as an attempt to spell out my ideas. I concentrated on two critical institutions, journalistic criticism and academic interpretation. But I think my claims could be applied to “amateur” critics and fandoms too. (This blog entry on Room 237 gestures in these directions.) Another article on this site, “Film Interpretation Revisited,” is a summary of the book, as well as a reply to critics.

So much for “the beholder’s share.” Can we go back to the “maker”? In a later section I’ll float some ideas about the place of thematics in relation to form and style. I’ll also consider how artists can anticipate and manipulate the appropriation process–a sort of meta-strategy to grab control higher up the chain.

Yes, spoilers for The Hunt are involved.

Interpretation, whys and wherefores

Interpretation seems to me to involve two tasks. First, there’s problem-solving: How should I interpret this film (or show, or whatever?) Second, there’s argument, or rhetoric: How should I make the case that this interpretation is worthwhile? Making Meaning has a lot to say about critical rhetoric, but I’ll concentrate on the problems interpreters set themselves.

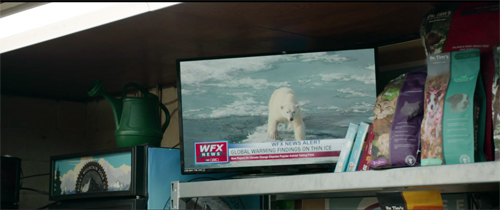

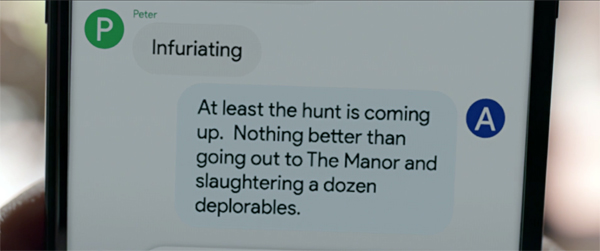

I assume that interpretation ascribes meanings to films. What sorts? I start with referential meanings (a big category including building the story world as well as tapping into real-world information, like specific times and places). In The Hunt, recurring TV images of polar bears struggling on melting ice floes nudge us to remember the climate crisis.

There’s an extra referential layer in the chyron, which expresses Fox-News style skepticism about climate change. That line helps confirm the right-wing ideology that supposedly permeates the quickee mart.

The other sorts of meaning I identify are more abstract. They include explicit meaning, usually given in language. In The Hunt, Athena expresses her disdain for the Deplorables whom she has gathered her friends to kill. She articulates a part of the film’s explicit meaning: The elite treat their social inferiors as prey.

There’s also implicit meaning, suggested through many cues, not just verbal ones. Crystal, the fierce fighter who confronts Athena at the end, is too laconic to speechify, and she never asserts that the underclass can be resilient and pitiless. But we are to grasp that meaning through her behavior–as the prey fighting the predator. Story comprehension feeds our interpretive move. By the end of the film we may take the polar-bear footage as implying that the Politically Correct hunters care more for these beasts than their vulnerable fellow humans.

Referential meaning, explicit meaning, and implicit meaning are typically under the control of the filmmakers. Clearly Craig Zobel, Damon Lindelof, Nick Cuse, and their colleagues want us to make the inferences I just made, along with many others. But it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that some implicit meanings escape the filmmakers. I’ll try to show later that filmmakers sometimes try to back up and frame their films to cover those unintended implications.

We can argue about some of these meanings. In The Hunt, Crystal recalls a childhood story of a race between a rabbit and a turtle. The rabbit lost through laziness, but he took revenge on the turtle by killing him and his family. The tale becomes part of a motif: Early in the film we see a video of a turtle humping a boot, while at the end we see a bunny hop into a gory kitchen.

After telling the story, Crystal declares she’s not sure whether she’s the rabbit or the turtle in the hunt. I think we’re supposed to think about whether the underclass (if it’s the turtle) can ever win more than a temporary victory. This sort of equivocation about implicit meaning is common in artworks. Indeed, the clash of implications encourages us to interpret them. The tactic might seem designed only for “difficult” films, but it’s surprisingly frequent in mainstream movies, as I’ll suggest later.

A fourth sort of meaning, I think, is what people have come to call symptomatic meaning. Here the film says more than it intends. It reveals, like a psychoanalytical symptom, an “unconscious” problem with the explicit and implicit dimensions put forth. (This is the “hermeneutics of suspicion,” which Susan Sontag discusses in “Against Interpretation” in relation to Marx and Freud.)

Critics may say that cheerful Eisenhower-era comedies betray anxieties about gender and identity. Some consider superhero franchises as unwittingly betraying a commitment to fascistic authority. From this perspective, Indiana Jones is less an adventurer than an imperialist. Symptomatic meanings leak out and can’t be contained. If implicit meaning is the filmmaker being more or less subtle, symptomatic meaning works behind the filmmaker’s back.

The Hunt is of course ripe for symptomatic interpretation, as I’ll mention below. However much its sympathies may seem to lie with the prey, it seems unable to avoid double-edged gags at their expense.

For all of these types of meaning, the process I posit is the same. The viewer maps, from the top down, concepts onto cues and patterns found in the film. Given the results of perception and comprehension, the viewer selects certain items to bear the meanings we bring to the task.

For example, I said that Athena articulates the predatory view of the oligarchy. Why did I pay attention to her and her words rather than, say, the layout of comestibles on the kitchen island? Because I have a rough but well-practiced mental schema for personhood. That’s more salient in building up a narrative than spotting bits and pieces of scenery. (These details can become salient, as the cheese-slicer will eventually, but the filmmaker has to make them so, as hand props or in close-ups or whatever.)

Making movies mean (but not like Zahler does)

The information in a film is most simply a flow of images and sounds. Perceptually I go beyond that information to recognize a person. Given that my person schema is furnished with properties like beliefs, desires, consciousness, and so on, I can build up a sense that Athena is stating her views on late capitalism.

Similarly, my repertoire of person schemas enables me to build up a sense of Crystal’s character, based on her appearance, speech, and actions. She too has beliefs (she’s being hunted), desires (she wants to survive), plans (she will fight), and attitudes (she scorns the sissified elites). She has character traits. In certain relevant respects, she’s like us and the people we know.

Filmmakers are practical psychologists. They know, from having consumed films as well as made them, how to highlight information and make it vivid and salient, so that we’ll lock in our concepts easily. For lots of reasons, we’re interested in other people, so that gives film artists an immediate purchase on using characters and their actions to convey abstract or general meanings.

For symptomatic interpretation, the same process holds. Character recognition and construction will be important for finding the flaws and failings of the film’s primary meanings. Of course, the symptomatic critic may “read against the grain” and look for less salient items that betray the film’s unconscious meanings. The fact that the climactic confrontation takes place in a kitchen could suggest that the filmmakers, for all their flaunting of strong women, are assuming a patriarchal ideology: Woman’s place, even as a killer, is in the home.

And the very end of the film, with Crystal strutting out as a fashionista, suggests that she has bought into the shallow values of the elite.

She’s not leading a revolution but killing her way to upward mobility.

I emphasize character as a site of interpretive elaboration because it’s so central to all critical schools, from fandom and journalism to the upper reaches of Academe. It’s not the only set of cues that get mobilized, though. Small details dropped in can serve too. A jar of Pickled Pigs Lips in a fake quickee mart reveals the sneering disdain of the hunters who’ve set up the display, but some viewers may find that it nudges us to mock trailer-trash taste.

The glimpse we get of the jars before the camera pans away seems to be the sort of cue aimed at “committed viewers,” willing to freeze the frame in playback to look for touches like this.

In Making Meaning, I talk about structural patterns as well, like journeys and character relationships, which prompt us to assign interpretations. There are stylistic cues too–not just the soundtrack with its dialogue and not just written language, but also camera movements, cutting, lighting, and so on. All these can be recruited to bear meanings. Critics often interpret a low angle as conferring power on a figure. Style, at bottom aimed at guiding attention and creating emphasis through the line of least resistance, can sometimes come forward and fill less concrete and fundamental functions–that of suggesting implicit or symptomatic meanings.

To wax wonkish again, Making Meaning suggests that the abstract meanings critics map onto cues are organized as semantic fields,which are in turn processed by assumptions and hypotheses. All that machinery is put into motion through schemas (prototypes and mental models) and heuristics (short-cut reasoning routines provided by social milieu or personal proclivity). The result is a “model film,” the film as interpreted by the critic.

You need lose no sleep over these matters. I simply argue that interpretation is a rational, fairly systematic process of informal reasoning operating within institutions that reward certain activities. Academics reward novel “readings,” while arts journalism does less elaborate versions as well. Even the “male gaze,” though stripped of its Lacanian baggage, has found its way into mainstream criticism (and the film industry).

Themes are memes, sometimes

“Themes come cheap,” I said one night in the seminar, rather flippantly. “They’re practically free.”

What I was suggesting was that themes are often obvious in a way style and overall form aren’t. They rise out at us unbidden. Before people watched The Hunt, they had been alerted to look for certain meanings. Mass media, critics, and the filmmakers had primed us to catch the big ideas the film was laying out.

That’s because films take meanings not only as effects but also materials. Films are made out of images and sounds, but they’re organized through form and style . . . and themes. If we look at it from the filmmaker’s standpoint, themes (like subject matter) can be treated as stuff to be worked on through technique. Like subject matter, they can float “obviously” on the surface, protruding a bit but still tugged by the flow of form and style.

In the Poetics Aristotle posited the category of “thought” as a component of tragedy. This term appears to mean something rather special. “Thought” isn’t what characters in drama think, or even what the playwright thinks. Rather, it’s what the characters say: their efforts to crystallize ideas and feelings in statements. The functions of thought in this sense “are demonstration, refutation, the arousal of emotions such as pity, fear, anger, and such like, and arguing for the importance or unimportance of things.”

The plot, Aristotle says, must create its effects through events and their patterning, “but these must appear without explicit statement, whereas in the spoken language it is the speaker and his words which produce the effect.” Thought in Ari’s sense spells out what action leaves tacit.

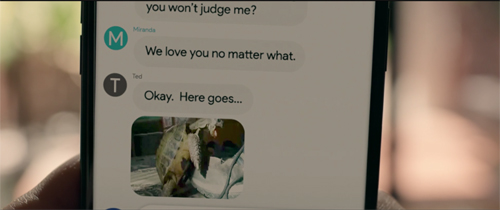

The Hunt does both. Ideas, images, and stereotypes circulating in US society have been taken by the filmmakers as already-fairly-processed material to be reworked into images and sounds and story. The explicit and implicit meanings critics build out from the film are the result of form and style shaping all this stuff into a perceptible, comprehensible experience. At moments, though, the oligarchs and the Deplorables state their sociopolitical views pretty frankly, as in the text message above. As Ari puts it, “they argue for the importance and unimportance of things.” Thought-as-theme is a prime cue for interpretation.

Themes can become not only material but also pattern. Certain genres of narrative are heavily “thematized” in that their organization is based on explicit or implicit meanings. Allegory is a classic instance. The Pilgrim’s Progress has a thematic armature, crystallized in the journey of Pilgrim to the Heavenly City. Ditto Animal Farm, which is usually taken as an allegory of the Russian Revolution. (Interestingly, The Hunt cites Animal Farm.) I expect that right now some grad students are writing papers about The Hunt as an allegory of working-class resistance.

Other heavily thematic genres are parables, fables, and the like. Crystal’s childhood story of the rabbit and the turtle becomes a parable of social injustice.

There are lots of ways that themes provide formal architecture. Some early films, like One Is Business, the Other Crime (1912), depend on thematic contrast. Here the fate of a poor man forced into thievery is juxtaposed with the law’s ignoral of a rich man’s transgressions. (Class resentment didn’t start with The Hunt.) Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) tries for a four-way thematic comparison/contrast of prejudice through the ages.

We also have “social cross-section” films, where stages of the narrative enact encounters with various institutions. As critics have noted, in The Bicycle Thieves(1948), Ricci’s search for his stolen bike brings him into contact with the labor union, the government, the church, and the bourgeoisie–none of whom are of help. A similar cross-sectional dynamic suggests social critique in Mizoguchi’s Life of Oharu (1952) and Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960).

Granted, in such modes, the film’s thematic skeleton can seem obvious. Other films leave meaning more free-floating, and even allegories can be less clear-cut than they may seem. (Think of Kafka.) I just want to signal, for the sake of comprehensive coverage, that filmmakers, like other artists, draw upon abstract ideas and meanings as materials to be reworked by their art.

To be good critics, we ought to be aware of both the materials and the transformations that come from them. I suggest this in a piece I’ve flagged before, “Zip. Zero. Zeitgeist.”

The filmmakers fight the power (of viewers)

The filmmaker’s power wanes as we move toward appropriation. But not completely. Filmmakers can use themes to manage a film’s reception.

For example, the Russian Formalist literary theorists floated the idea of the “biographical legend.” This is a public version of the artist’s life that can guide interpretations of the work. Boris Eichenbaum suggested that the Americans had one biographical legend for O. Henry, but the Russians built up a different one.

Critics and commentators build up the biographical legend in order to support interpretations, but the artist can contribute to the process. When Christopher Nolan tells us that as a youth he loved Star Wars, noir movies, and experimental fiction, he’s inviting us to put his own “intellectual blockbusters” in a certain perspective. He’s flagging certain cues, inviting certain mental sets, coaxing us toward certain inferences.

It’s not news. Contemporary critics took Douglas Sirk’s 1950s melodramas as glossy reflections of the superficial values of Eisenhower America. But when he was interviewed by Jon Halliday, he presented himself as offering a Brechtian critique of those values. Later critics eagerly started scanning the films for narrative and stylistic cues that suggested implicit meanings that subverted the suburban bourgeoisie. Chabrol, typically jaundiced, put it this way:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics with their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, not knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want.

If critics can use the artist to interpret the film, why can’t the artist use the critics to steer us toward preferred interpretations?

It isn’t just the filmmaker doing this. Auteur personas created by the filmmaker, the industry, and critical discourse can be seen as pushing us toward certain thematic interpretations.

Now to finish with a point I suggested above. It’s often in a filmmaker’s interest to avoid consistent and clear presentation of themes. I’ve come to think that many ambitious Hollywood films are systematically ambivalent about what they are “saying.” Rather than make a weighted, compact statement of “thought” in Ari’s sense, they scuttle and shuttle between alternate thematic possibilities. Or rather, they shuffle several disparate “thought” statements to counterbalance one another.

This has many benefits. It can stoke controversies. Is The Dark Knight in favor of vigilantism, or does it celebrate anarchy, or does it hold out hope of noble self-sacrifice? Nolan says:

We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story. . . . We’re going to get wildly different interpretations of what the film is supporting and not supporting, but it’s not doing any of those things. It’s just telling a story.

Another benefit: If someone objects to one piece of thematic material, you can always say, “But look, we offset that with this…” It’s a way of widening the film’s appeal to many lines of thinking, while marketing the film as complex.

The creators of The Hunt claim to have aimed the film at smugly woke people like themselves in an effort to humanize the Other.

So we heightened the reality as much as we could. Some of the people who are being hunted are literally the guy with the tiki torch or a guy posing next to a dead animal; they’re two-dimensional stereotypical representations of what liberals see conservatives as. And then we had to do the same thing with the liberals. But there had to be one character in the movie, the hero who defied the conventions of stereotyping, who when you look at her you basically say, “Oh, she has an accent like this. She wears clothes like this. This is who she is.” And let’s be wrong about her. Let’s let the movie be about the cautionary tale of, here’s what happens when you get it wrong.

I think that the idea the audience wants Athena to be wrong about Crystal is maybe our own interior desire to say, “Maybe I’m wrong about my uncle who I’m screaming at at Thanksgiving. Maybe there’s a little bit more to him than meets the eye. Maybe I’m trying to put him in this specific lane because we have to choose a side, but maybe there’s many sides and there’s a little bit more nuance in the conversation.”

The caricaturing of the woke characters allows woke viewers to recognize the satire (and since woke viewers are likely to be educated, they know that satire exaggerates). Presentation of the Deplorables is exaggerated too, confirming that “There’s many sides.”

But there’s a kink for a symptomatic reading: Crystal may not be an actual Deplorable. We never learn her politics. She has been kidnapped in error, mistaken for a fierce Trumpist with the same name. So again the film manages to have it many ways. “Getting it wrong” here doesn’t mean disparaging a right-winger but rather not knowing whether somebody is right-wing or not. The real conversation is postponed because of a mistake. (No mistakes, no stories.)

I don’t mean to sound cynical about this. Art is opportunistic. We just ought to be aware that filmmakers can make the meta-move, using whatever means they can to close off interpretations that they might not prefer. Ultimately, since appropriation is top-down, they can’t control everything we might ascribe to the film. (See Room 237 again.) But there is a bit of a struggle there. Filmmakers will always try to join and constrain the hunt for meaning in their movies.

There’s a lot more to be said about interpretation, but I hope that readers will find something worth considering here. I may redo other Private seminar entries as public ones when time permits.

Thanks to Nic Rapold of Film Comment and Imogen Sarah Smith for a pleasant discussion. My citation of Aristotle on “thought” is from Stephen Halliwell, The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary (Chapel Hill, 1987), 53. The reinterpretation of Sirk’s melodramas was undertaken in Jon Halliday’s interview book Sirk on Sirk (Secker and Warburg, 1971). The Chabrol quote is from Making Meaning (Harvard University Press, 1989), 210.

Phoenix (2014), one of the Christian Petzold films discussed in the Film Comment “At Home” podcast.

Vancouver 2018: Panorama of the Rest of the World, the sequel

Seder-Masochism (2018)

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival is over, but we still have films to talk about. Here are four, and David and I will probably post another blog apiece. Between Venice and Vancouver, we have seen a lot of great and very good films recently. Once again, the claims of the death of cinema are robustly refuted.

Dogman (Matteo Garrone, 2018)

Garrone is best known outside Italy for his 2008 film Gomorrah. While that film was about gangs and organized crime in Naples, Dogman centers around a shifting relationship between a meek-mannered dog/boarder/groomer who has fallen in with a volatile, enormous local thug.

The title emphasizes the honest side of Marcello’s life, and we see some comic scenes of him with dogs. Soon, however, it is revealed that he sells cocaine on the side and sometimes acts as a getaway driver for thefts committed by the monstrous ex-boxer, Simoncino. Eventually he even takes the fall for a robbery and spends a year in jail in Simoncino’s place.

We’re clearly intended to side with this sad sack. After one house robbery, Simoncino’s partner reveals that he put a dog in the freezer to keep it quiet. Marcello sneaks back in and, a suspenseful and remarkable scene, attempts to revive the frost-covered animal. He also dotes on his daughter and seemingly pursues his criminal activities in order to be able to take her on “adventures,” including scuba-diving.

Despite this sympathetic side, however, Marcello never seems to consider giving up crime; he’s mainly interested in getting his fair share of Simoncino’s ill-gotten gains. Although the film is continually entertaining and suspenseful, its ending is somewhat disappointing. We are left knowing what Marcello’s probably fate will be, but we have little sense of his attitude toward what has happened.

Marcello Fonte, looking like a rather emaciated version of the comic Toto, won the Best Actor prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Magnolia has the US rights and plans to release Dogman in 2019.

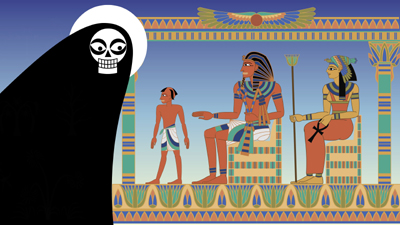

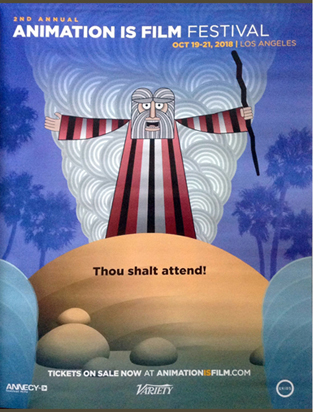

Seder-Masochism (Nina Paley, 2018)

Seder-Masochism is the only US film I’ll be writing about from Vancouver. (We tend to skip US films here, since we assume we can see them in the US.) Paley’s not part of the Hollywood establishment or even the mainstream indie scene. It’s not easy to see her wonderful animated films on the big screen, but their bright colors and imaginative graphics deserve to be shown that way.

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

This conversation is a mix of humor and serious points about Judaic traditions and particularly the celebration of Passover. The story of Moses and the Exodus is rendered in much the same way she treated the tale of Sita and Rama from the Hindu epic, the Ramayana–with musical numbers. Moses is introduced with “Moses Supposes,” from Singin’ in the Rain, and, inevitably, there is a “Go Down, Moses” episode. Unlike Sita, where blues songs were used throughout, the musical pieces in Seder are wide-ranging, culminating in a brilliant three-minute summary of the history of the territory which is now Israel, done to “This Land is Mine,” the song written to the theme of Otto Preminger’s Exodus. (The sequence, as well as several other excerpts from Seder are available on YouTube.)

The sequences set in ancient Egypt are generally accurate. I was amused by the fact that the animal and bird hieroglyphs in the background inscriptions moved rhythmically during the musical numbers, and the Hathor heads on the sistrums sang along. Using Hathor, the cow goddess, as the golden calf was an inspiration.

Seder-Masochism got the most enthusiastic applause I heard at the festival, partly because the filmmaker was present (in her custom Seder dress). There were Sita fans in the audience, and one Jewish lady asked how she could get a copy to show her 12-year-old daughter. Paley replied that the film will continue to play festivals and probably be available on the fim’s website for download in the spring.

In the meantime, watch for it at festivals–or let the organizers know that you want to see it on their schedule. We were happily surprised to see a full-page ad for the Los Angeles Animation Is Film Festival (October 19-21) in the current Variety (above left) and illustrated by an image derived from the film. You may find others.

Styx (Wolfgang Fischer, 2018)

I was surprised to discover that so far Austrian director Wolfgang Fischer’s Styx has not been picked up by a North American distributor. It seems like the sort of film to appeal strongly to audiences. It’s protagonist is a strong, ultra-competent woman, it has a riveting plot full of suspenseful situations, and it deals with the immigrant crisis facing Europe.

A long portion of the film contains no real dialogue. The opening sequence occurs at the scene of a traffic accident where the heroine, Rike, is established as a doctor as she heads the team treating the victim. Cut to her provisioning her yacht for a solo trip. A lovely shot of a compass “walking” its way down a map establishes her route and distant goal: Ascension Island (see bottom). Her departure reveals that her starting point is Gibraltar (above). From that point, we watch Rike expertly dealing with her vessel, enjoying the solitude of the ocean, and reading about Darwin’s activities on Ascension.

Apart from a few overheard commands during the initial emergency scene, there is no dialogue until Rike makes radio contact with a nearby commercial vessel which warns of a serious storm approaching. A tense scene of her struggle to deal with the storm at night creates the first major suspense of the film. From her arrival in an ambulance in the opening sequence, actress Susanne Wolff is present in every scene, and as an experienced sailor she was able to handle the yacht and do without a stunt double.

Rike comes through the storm without difficulty, but a leaky vessel crowded with African immigrants striving to get to Europe is visible in the distance. Ordered by a coast-guard official not to interfere, she uneasily waits for a sign of a rescue vehicle that still has not shown up after hours of waiting. One teen-aged boy manages to swim from the derelict ship, and he complicates her situation considerably. The dilemma remains: try and take the rest of the refugees on board her small yacht or wait for the promised rescue.

The remainder of the film generates unrelieved suspense as Rike debates what to do and Kingsley begs her to rescue his sister, still abroad the sinking boat. A non-actor discovered in a school in Nairobi, Gedion Oduor Weseka is convincing and touching as the desperate boy.

Nearly all of Styx was shot at sea, with Fischer’s small crew mounting their camera hanging off the sides of the boat and scrambling to keep out of sight during filming. No special effects were used for the storm and other ocean scenes. At intervals some impressive extreme long shots from overhead, presumably taken by drones, emphasize the yacht’s isolation in the vastness of the sea.

The film is riveting from beginning to end. I recommend it, though at least for North America, festival screenings are probably the main places where it can be seen. Perhaps it will eventually be available on streaming services. In some European countries, it will probably be released theatrically.

Transit (Christian Petzold, 2018)

The central premise of Transit resembles that of Casablanca. A group of émigrés are desperately awaiting the letters of transit that will allow them to flee fascist Europe for North America. In this case they’re in Marseille rather than Casablanca, and the plot focuses on one rather ordinary, non-heroic man–or so he seems. Our protagonist is Georg, a Jew lingering in Paris as the authorities arrest fugitives. The authorities are working for a fascist regime, though Nazis are never mentioned specifically.

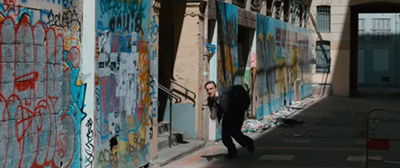

Moreover, the settings and costumes are mainly modern. Early on Georg flees a round-up through allies covered with spray-painted graffiti (below), and the vehicles in the streets are all contemporary models. Petzold’s avoidance of period mise-en-scene sets up a strange, somewhat surrealist world, but it also invites us to consider the parallel with current social problems.

By chance Georg gains possession of the manuscripts and papers of Weidel, a well-known author who has met a bloody end in a cheap hotel room. Fleeing to Marseilles with a wounded fellow Jew who dies along the way, Georg visits the Mexican consulate and is mistaken for Weidel, whose transit papers for him and his estranged wife have been approved. Naturally Georg accepts the error. While waiting for the papers to come through, he befriends his dead friend’s widow and her son, immigrants to Europe from the Maghreb, and by chance encounters and falls in love with Weidel’s wife (who does not realize her husband is dead), hoping to use the two letters of transit to escape to a new life with her.

Between the inexplicable modern settings and costumes and the extraordinary coincidence of this meeting, the film is far from being realistic. It reminded me of the late films of Manoel de Oliveira (see our earlier reports on Doomed Love, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl, The Strange Case of Angelica, and Gebo and the Shadow), with touches of Bresson in the situation and the acting, particularly of Franz Rogowski as Georg. But Petzold is not simply imitating these and other directors. Transit is a remarkable, original film, one of the best we saw at Vancouver.

Transit has been acquired for US distribution by Music Box for an early 2019 release. Definitely keep an eye open for a screening near you, most likely in festivals and large-city art houses and perhaps eventually on streaming..

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Styx (2018).