Archive for December 2015

The ten best films of … 1925

The Big Parade (1925).

Kristin here:

As all about us in the blogosphere are listing their top ten films for 2015, we do the same for ninety years ago. Our eighth edition of this surprisingly popular series reaches 1925, when some of the major classics of world cinema appeared. Soviet Montage cinema got its real start with not one but two releases by one of the greatest of all directors, Sergei Eisenstein. Ernst Lubitsch made what is arguably his finest silent film. Charles Chaplin created his most beloved feature. Scandinavian cinema was in decline, having lost its most important directors to Hollywood, but Carl Dreyer made one of his most powerful silents.

For previous entries, see here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924.

The lingering traces of Expressionism vs the New Objectivity

The Joyless Street (1925).

Last year I suggested that German Expressionism was winding down in 1924. It continued to do so in 1925. Indeed, no Expressionist films as such came out that year. What I would consider to be the last films in the movement, Murnau’s Faust and Lang’s Metropolis, both went over budget and over schedule, with Faust appearing in 1926 and Metropolis at the beginning of 1927.

Murnau made a more modest film that premiered in Vienna in late 1925, Tartuffe, a loose adaptation of the Molière play. The script adds a frame story in which an old man’s housekeeper plots to swindle and murder him. The man’s grandson disguises himself as a traveling film exhibitor and shows the pair a simplified version of the play, emphasizing the parallels between the hypocritical Tartuffe and the scheming housekeeper.

The film has some touches of Expressionism but cannot really be considered a full-fledged member of that movement. The lingering Expressionism is not surprising, considering that some of the talent involved had worked on Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr.Caligari: screenwriter Carl Mayer, designers Walter Röhrig and Robert Herlth, and actors Werner Krauss and Lil Dagover.

The visuals include characteristically Expressionist moments when the actors and settings are juxtaposed to create strongly pictorial compositions. These might be comic, as when the pompous Tartuffe strides past a squat lamp that seems to mock him, or beautifully abstract, as when Orgon is seen in a high angle against a stairway that swirls around him:

A restored version is available in the USA from Kino and in the UK in Eureka!‘s Masters of Cinema series. (DVD Beaver compares the two versions.) The restoration was prepared from the only surviving print, the American release version; it runs about one hour.

The other German film on this year’s list, G. W. Pabst’s The Joyless Street, contrasts considerably with Tartuffe. It was arguably the first major film of the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity trends in German cinema. I have already dealt with it in a DVD review entry shortly after its 2012 release. The restoration incorporated a good deal more footage than had been seen in previous modern prints, but it remains incomplete.

Once more the comic greats

The Gold Rush (1925).

For several years now these year-end lists have mentioned Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd, in various combinations. Early on it would was Chaplin alone (Easy Street and The Immigrant for 1917) or Lloyd and Keaton alone (High and Dizzy and Neighbors for 1920). In a way most of these films were placeholders, signalling that these three were working up to the silent features that were among the most glorious products of the Hollywood studios in the 1920s. In our 1923 list, each found a place with a masterpiece: Chaplin’s A Woman of Paris, Keaton’s Our Hospitality, and Lloyd’s Safety Last.

This year we may surprise some by giving Lloyd a miss. For years The Freshman was thought of as his main claim to fame, perhaps alongside Safety Last. I think this was largely because The Freshman was the one of the few Lloyd films that was relatively easy to see. (Perhaps also because Preston Sturges dubbed it an official classic by making a sequel to it (The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, aka Mad Wednesday, 1947.) Now that we have the full set of Lloyd’s silent features available, it emerges as a rather tame entry compared to Safety Last, Girl Shy, or our already-determined entries for 1926, For Heaven’s Sake, and 1927, The Kid Brother. Let’s just call The Freshman a runner up.

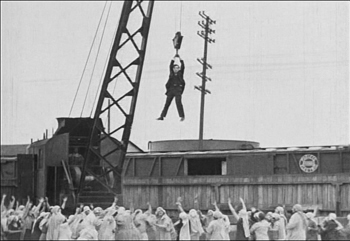

Keaton’s Seven Chances takes one of the most familiar of melodramatic premises and literally runs with it. James Shannon discovers from his lawyer than he stands to inherit a great deal of money if he is married by 7 pm on his 27th birthday–which happens to be the day when he receives this news. A misunderstanding with the woman he loves leads to a split, and in order to save himself and his partner from bankruptcy, Shannon determines to marry any woman who will volunteer in time. Hundreds turn up.

The result is another of the extended, intricate chase sequences that tend to grace Lloyd’s and Keaton’s features, and to a lesser extent Chaplin’s. In fact Seven Chances has a double chase. The first and longer part involves a huge crowd of women gradually assembling behind Shannon as he unwittingly walks along the street. This accelerates and keeps building, exploiting various situations and locales, as when the chase passes through a rail yard and Shannon escapes by dangling from a rolling crane above the women’s heads. Eventually the action moves into the countryside, where the brides temporarily disappear, taking a short cut to cut Shannon off, and he ends up in the middle of a gradually growing avalanche.

Seven Chances is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino.

Of all the films on this year’s list, Chaplin’s The Gold Rush is probably the most widely familiar. The Little Tramp character, here known only as a “Lone Prospector,” blends hilarity with pathos in a fashion that is actually typical of relatively few of the director/performer’s films overall. It is, however, how many people think of him.

The Gold Rush looks rather old-fashioned compared with Seven Chances. Although the opening extreme long shots of an endless line of prospectors struggling up over a mountain pass are impressive, much of the action takes place in studio sets, sometimes standing in for alpine locations. Both the cabins, Black Larsen’s and Hank Curtis’, are like little proscenium stages, with the action captured from the front. Yet the film depends on its brilliant succession of gags and on the Prospector’s status as the underdog who is also the resilient and eternal optimist.

The best bits of humor arise from Chaplin’s ability to create funny but lyrical moments by transforming objects metaphorically. Given the plot, some of the best-known gags arise from meals. One is the dance of the rolls, part of a fantasy sequence in which the Prospector dreams of entertaining a group of beautiful women at dinner (above), when in fact the women stand him up. Trapped by a storm in a remote cabin, the Prospector and his partner cook one of his shoes. He serves it on a platter and carefully “carves it, with the leather becoming the meat, the nails bones, and the laces spaghetti.

Many home-video versions of The Gold Rush have been released, but the definitive restoration of the 1925 version is available from the Criterion Collection.

The Golden Age in full swing

Lazybones (1925).

When people speak of the “Golden Age” of the Hollywood studio system, they usually seem to mean the 1930s and 1940s (and the lingering effects of the system in the 1950s). A look at Hollywood films of the 1920s shows that it was already functioning at full steam. Three features of 1925 display the utter mastery of continuity storytelling and style and a sophistication that matches films of subsequent decades.

Lady Windermere’s Fan may be the best silent made by Ernst Lubitsch, who has appeared on these lists before. It arguably ranks alongside Trouble in Paradise and The Shop around the Corner as one of the best films of his entire career. It’s a loose adaptation of the Oscar Wilde play, but it’s pure Lubitsch throughout.

Anyone who thinks that the classical Hollywood system was merely a set of conventions that allowed films to be cranked out with minimal originality could learn a lot from Lady Windermere’s Fan. Its completely correct use of continuity editing, three-point lighting, and the like does not preclude imaginative touches and methods of handling whole scenes. There’s the sequence when Lord Windermere visits the mysteriously shady lady Mrs. Erlynne in her drawing-room. The camera is planted in the center of the action, with frequents cuts as the two characters move in and out of the frame and even cross behind the camera. There’s not a hint of a mismatched glance or entrance across this complex and unusual series of shots. There’s the racetrack scene, as everyone present watches and gossips about Mrs Erlynne in a virtuoso string of point-of-view shots.

The racetrack scene ends with a wealthy bachelor following Mrs Erlynne out of the track. The camera moves left to follow her, keeping her in the same spot in the frame. As the man gradually catches up, Lubitsch uses a moving matte to hint at their meeting without showing it or cutting in toward the action.

A good-quality transfer of Lady Windermere’s Fan is only available on DVD as part of the More Treasures from American Film Archives 1894-1931. (Beware the copy offered by Synergy, which according to comments on Amazon.com is from a poor-quality, incomplete print.)

The one title on this list whose inclusion might surprise readers is Frank Borzage’s Lazybones. I remember being bowled over by this film during the 1992 Le Gionate del Cinema Muto festival in Pordenone, which included a Borzage retrospective. I found the more famous Humoresque (1920) a disappointment, but Lazybones was a revelation. This is another case of a film that was simply unknown when film historians started writing about the Hollywood studio era. It was not discovered until 1970, when it was found in the 20th Century-Fox archives. As a result, Lazybones was, as Swiss film historian Hervé Dumont put it in his magisterial book on the director, “revealed as the most poignant–and the most accomplished–of Borzage’s works before Seventh Heaven.”

Year by year since we started this annual list, I looked forward to recommending Lazybones, and now we arrive there. I rewatched it for the first time to see if it really deserved to make one of the top ten. The answer is yes. For me, this is as good as 7th Heaven, or as near as makes no difference.

It’s difficult to describe the plot of Lazybones, since it doesn’t have much of one. Steve (played by the amiable Buck Jones) is a very lazy young man living in a rural village. He has a girlfriend, Agnes, whose mother scorns him. The girlfriend has a sister, Ruth, who returns home with a baby in tow. In despair, Ruth leaves the baby on a riverbank and tries to drown herself (image at top of section). Steve rescues her, and she explains that unknown to her family, while she was away she married a sailor who subsequently went down with his ship. She has no proof of this and knows her tyrannical mother will assume that the baby is illegitimate. Steve decides to keep her secret and adopt the apparent foundling himself.

All this happens during the initial setup. Then the little girl, Kit, grows up into a young lady. Along the way, not all that much happens. Steve, lacking any goals, stays lazy, which sets him apart from the energetic, ambitious protagonists of most Hollywood films. Kit is shunned by her classmates and the townspeople, and Steve tries to shelter her from all this. He loves Agnes but quickly loses her to a richer, more respectable man. He goes off to fight in World War I, becomes an accidental hero, and returns home after perhaps the shortest battlefront scene in any feature of the period. Kit finds a boyfriend.

What makes all this riveting viewing is its mixture of quiet comedy and poignancy. Steve is so amiably and unrepentantly loath to work that he is scorned by nearly everyone, and yet he commits an act of great kindness for which he gets no credit at all, except from his devoted mother. It is clear that these snobbish townspeople would scorn him even if they knew how he has kept Kit out of the orphanage and made a happy life for her.

The film is beautifully shot, and Borzage displays such an easy mastery of constructing a scene, particularly in depth, that it is easy to miss the underlying sophistication. Early on, Agnes and her mother arrive at Steve’s house. As Agnes waits outside the fence in the foreground, Steve tips his hat to her, in the foreground with his back to the camera. The mother passes by him toward the house, her mouth fixed in a sneer. We may think that Steve is oblivious to this, but once she passes out of the frame in the foreground, he puts his hat back on and slips it down over his face rather cheekily as he glances at her, his gesture suggesting his indifference to her opinion of him. (Note also the subtle touch of his lazily fastened suspenders.)

Borzage has mastered the use of motifs that are so characteristic of Hollywood cinema. There’s a running gag about the dilapidated gate of the picket fence around Steve’s and his mother’s house, with each person remarking “Darn that gate!” as they struggle through it. The repetition becomes cumulatively funnier because about two decades pass in the course of the film without the thing being fixed. The acting, particularly of Buck Jones and Zasu Pitts (as Ruth), is affecting.

It’s difficult to convey the charms of such an unconventional film, but give it a try and you may be bowled over, too.

A superb DVD transfer of Lazybones was included in the lavish Murnau, Borzage and Fox box (2008). The 20th Century-Fox Cinema Archives series offers it separately as a print-on-demand DVD-R. I’ve not seen it but suspect that there would be some loss of quality in this format. Besides, every serious lover of cinema should have that big black box sitting on their shelves next to the Ford at Fox one.

Returning to the more familiar classics, my final Hollywood film of the year is King Vidor’s The Big Parade.

Apart from its success and influence, however, The Big Parade remains an entertaining, funny, and moving film. Vidor’s scenes often run a remarkably long time, suggesting the rhythms of everyday life. One such action involves James fetching a barrel back to where he and his mates are staying so that he can turn it into an outdoor shower. When nearly back, he encounters Melisande, whom he initially can’t see. His stumbling about and her increasing laughter at his antics are played out at length (see top), as is a supposedly improvised scene shortly thereafter where James tries to teach Melisande how to chew gum.

A very different sort of prolonged scene is the long march of James and his comrades through a forest full of German snipers in trees and machine-gunners in nests. They begin by walking through an idyllic-looking forest, then increasingly encounter fallen comrades, and finally reach the Germans.

For years the prints of The Big Parade available were less than optimum, with some based on the 1931 re-release version, where the left side of the image had to be cropped to make room for the soundtrack. A 35mm negative was discovered relatively recently, however, and is the basis for the superb DVD and Blu-ray versions released in 2013.

Finally, I turn you over to David for some comments on films that fall within his specialties.

Eisenstein, action director

Watch this. Maybe a few times.

These two seconds, violent in both what they show and the way they show it, seem to me a turning point in film history. Here extreme action meets extreme technique. The spasms of the woman’s head, given in brief jump cuts (7 frames/5/8/10), create a sort of pictorial fusillade before we get the real thing: a line of riflemen robotically advancing into a crowd.

It’s not usually recognized how often changes in film art are driven by showing violence. Griffith’s last-minute rescues usually take place in scenes of massive bloodshed; not only The Birth of a Nation but the equally inventive Battle at Elderbush Gulch use rapid crosscutting to treat a boiling burst of action. The Friendless One’s pistol attack in Intolerance is rendered in flash frames that Sam Fuller might approve of. Later, the Hollywood Western, the Japanese swordplay film, the 1940s crime melodrama, the Hong Kong action picture, and many other genres pushed the stylistic envelope in scenes of violence. Hitchcock’s vaunted technical polish often depended on shock and bloodletting, from a bullet to the face (Foreign Correspondent) to stabbing in the shower (Psycho). The free-fire zone of Bonnie and Clyde and Peckinpah’s Westerns took up the slow-motion choreography of death pioneered by Kurosawa. Extreme action seems to call for aggressive technique, and intense action scenes can become clipbait and film-school models.

Sergei Eisenstein is celebrated as the theorist and practitioner of montage, whatever that is; but he insisted that what he called expressive movement was no less important. Just as montage for him came to mean the forceful juxtaposition of virtually any two stimuli (frames, shots, elements inside shots, musical motifs), so he thought that expressive movement ranged from a haughty tsar stretching his stork neck (Ivan the Terrible) to peons buried up to their shoulders, squirming to avoid horses’ hooves (Que viva Mexico!). In Eisenstein, psychology is always externalized, crowds move as gigantic organisms, and any action can turn brutal. (I fight the temptation to call him S & M Eisenstein.) We can trace influences—Constructivist theatre, the chase comedies coming from America, his interest in kabuki performance—but when he moved into cinema from the stage, Eisenstein became an action director, in a wholly modern sense.

Eisenstein’s first two features bracket the year 1925. Strike was premiered in January, The Battleship Potemkin in December. The first was apparently not widely seen outside Russia until the 1970s, but the second quickly won praise around the world. Potemkin’s centerpiece, the Odessa Steps sequence, became an instant critical chestnut, proof that cinema had achieved maturity as an art. Owing nothing to theatre, this massive spectacle was as pure a piece of filmmaking as a Fairbanks stunt or a Hart shootout. But of course Eisenstein went farther.

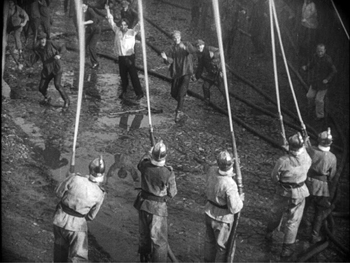

The Steps sequence was probably the most violent thing that anybody had ever seen in a movie. A line of soldiers stalks down the crowded staircase. A little boy is shot; after he falls, skull bloodied, his body is trampled by people fleeing the troops. Another man falls, caught in a handheld shot. A mother is blasted in the gut, and her baby carriage, jouncing down the steps, falls under a cossack’s sword. A schoolmistress who has been watching in horror gets a bullet in the eye–or is it a saber slash? The sequence ends as abstractly as it began, if “abstractly” can sum up the horrific punch of these images.

The film is much more than this sequence, of course, but every one of its five sections arcs toward violence, and each payoff is shot and cut with punitive force. The mutiny itself is a pulsating rush of stunts, unexpected angles, and cuts that are at once harsh and smooth. The whole thing starts with a rebellious sailor smashing a plate (in inconsistently matched shots) and ends with the ship confronting the fleet, a challenge rendered by percussive treatment of the men and their machines.

In Strike, Eisenstein rehearsed his poetry of massacre, along with a lot of other things. Instead of rendering an actual incident, as in Potemkin, here he portrays the typical phases any strike can go through. The plot starts with injustices on the shop floor, escalates to a walkout, and then—of course—turns violent, as provocateurs make a peaceful demonstration into a pretext for harsh reprisals. Throughout, Eisenstein experiments with grotesque satire and caricature. The workers are down-to-earth heroic; the capitalists are straight out of propaganda cartoons; the spies are beastly, the provocateurs are clowns. Every sequence tries something new and bold, and weird.

The most famous passage, well-known from his writings if not from actual viewing, is the climax. Here a raid upon workers in their tenements is intercut with the slaughter of a bull. Montage again, of course, but what isn’t usually noticed is the remarkable staging of that police riot, with horsemen riding along catwalks and fastidiously dropping children over the railings. For my money, more impressive than this finale is the earlier episode in which firemen turn their hoses on the workers’ demonstration. The workers scatter, pursued by the blasts of water, until they are scrambling over one another and pounded against alley walls. This is Strike’s Odessa Steps sequence, and for throbbing dynamism and pictorial expressiveness–you can feel the soaking thrust of the water–it has few equals in silent film.

For Eisenstein, the bobbing, screaming head in my clip was the “blasting cap” that launched the Odessa massacre. Is the woman the first victim of the troops, or is her rag-doll convulsion a kind of abstract prophecy of the brutality to come? Yanked out of the actual space of the action, it hits us with a perceptual force that goes beyond straightforward storytelling. Kinetic aggression, making you feel the blow, is one legitimate function of cinema. Eisenstein is our first master of in-your-face filmmaking.

After many tries, archives have given us superb video editions of Potemkin and Strike, both available from Kino Lorber. Potemkin’s original score captures the film’s combustible restlessness. Strike seems to have been shot at so many different frame rates that it’s hard to smooth out, but the new disc makes a very good try, and it’s far superior to the draggy Soviet step-printed version that plagued us for decades.

Chamber cinema

Every so often a filmmaker decides to accept severe spatial constraints, creating what David Koepp calls “bottle” plots. Make a movie in a lifeboat (Lifeboat) or around a phone booth (Phone Booth) or in a motel room (Tape) or in a Manhattan house (Panic Room) or in a remote cabin plagued by horrors (name your favorite). In the 1940s several filmmakers were trying out a “theatrical” approach that welcomed confinement like this; Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles, H. C. Potter’s The Time of Your Life, and of course Rope are examples. Today’s filmmakers are still exploring “chamber cinema.” The Hateful Eight is the most recent instance, with most of its chapters set in Minnie’s Haberdashery.

Typically, the chamber films in any period aren’t “canned theatre” like the PBS or English National Theatre broadcasts. Chamber films push the camera into the space, often showing all four walls and letting us get familiar with the rooms the characters inhabit. But this requires not only a carefully planned setting but also a good deal of cinematic skill in smoothly taking us to the primary zones of action.

Carl Dreyer was one of the earliest exponents of chamber cinema. He had seen initial examples in German Kammerspiel (chamber-play) films like Sylvester (1924) and had made a mild version himself in Michael (1924). Dreyer took the aesthetic to new heights in The Master of the House (1925).

Long before Akerman’s Jeanne Dielmann, Dreyer gave us a film about housework. Ida’s husband Victor is unemployed, so while he loafs and drifts around town, she struggles to keep things going. He pays her back with scorn and abuse. The plot is structured around two days, which yield a before-and-after pattern. At the end of the first, Ida leaves Victor, and a month later, his realization of his mistakes is revealed by his behavior in the household. The drama comes not only from the characters’ conflicts but from the way they handle everyday things like butter knives and laundry lines.

Rendering the household in all its specificity obliges Dreyer to rethink continuity filmmaking. He lays out the geography of the home by shooting “in the round” and cutting on the basis of eyelines and frame entrances. (He displays the same confidence in the “immersive camera” that Lubitsch displays in Lady Windermere’s Fan.) He trains us to notice landmarks, to associate bits of action with particular areas of the apartment, and to sense the characters’ changing emotions in relation to small adjustments in composition. The film is an exceptionally fluid, assured one, and it prepares for more daring Dreyer experiments to come: the fragmented interior spaces of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, the creeping camera of Vampyr, and the intensely theatricalized late films Day of Wrath, Ordet, and Gertrud. Little-known at the time, The Master of the House has come to be regarded as one of the most quietly perfect of silent films.

The most lustrous edition of The Master of the House is the Criterion release. It contains an in-depth interview with Danish film historian Casper Tybjerg and a visual essay that Abbey Lustgarten and I prepared. Criterion has posted an extract from the essay. More about this release is here.

In connection with the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction, to be published in mid-January, we have added ten new online Connect video examples. These include one based on clips from the Blu-ray of The Gold Rush, which the Criterion Collection has kindly allowed us to use. We discuss two contrasting styles of staging used for comedy effects in the isolated cabin set.

The Dumont quotation is from his Frank Borzage: Sarastro à Hollywood (Cinémathèque française, 1993), p. 108.

Lea Jacobs and Andrea Comiskey have examined the complicated early distribution of The Big Parade in their “Hollywood’s Conception of Its Audience in the 1920s,” The Classical Hollywood Reader, Steve Neale, ed. (Routledge, 2012), p. 97.

Eisenstein’s aesthetic of expressive movement, and its relation to montage, is discussed in David’s The Cinema of Eisenstein. On Dreyer’s “theatricalized” cinema see his The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer, and this essay on its sources in 1910s tableau filmmaking. Eisenstein’s exactitude in matching gesture to sound and cutting is demonstrated in Lea Jacobs’ Film Rhythm after Sound, reviewed here.

Lev Kuleshov’s second feature, The Death Ray, doesn’t make our top-ten list for 1925, but as a bonus we include its poster (by Anton Lavinsky), which must rank among the most beautiful of that year.

THE HATEFUL EIGHT: A movie is a really big thing

Photo: Barbara Grassia.

DB here:

The latest dispatch from the Hateful Eight platter farm in Valencia CA, overseen by veteran film guru Chapin Cutler of Boston Light & Sound. Chapin writes:

This is a picture of the last three Hateful Eight prints leaving our print assembly location in Valencia. They are destined for local LA presentation locations.

Most of the other prints have been delivered or will be today [18 Dec.].

All locations have had their equipment delivered, save one; due to facility issues, that venue’s equipment will be delivered Monday. By Sunday night or early Monday morning, all but the expected and remaining nine venues will be complete. The remaining nine will be done by end of day, Wednesday, 23.

Just to remind you, from Chapin’s previous message:

Each shipping case is 5 ft. x 5 ft. by 1 ft. thick. When loaded, it weighs about 400 lbs. . . . With the reel full, out of the box, the film and reel weigh about 250 lbs. Four people can easily lift it onto a platter deck.

I’m asking Santa for one.

Thanks to Chapin for his work on the project and his cooperation with our blog. Thanks as well to the thriving and inspiring Art House Convergence.

If you haven’t yet seen the list of Hateful Eight 70mm venues and showtimes, you can find it here.

P.S. 23 December 2015: Thanks to Gary Meyer of Art House Convergence, here’s a link to a very full story on the rehabbing of projectors for Tarantino’s Great Experiment.

P.P.S. 31 December 2015: Be sure to check this suspenseful tale of projecting the movie…with Tarantino in the audience.

Modest virtuosity: A plea to filmmakers, old and young

Panic in the Streets (1950).

“It’s where you put the camera and what’s in front of you [that’s important],” Deakins said. “There’s too much obsession these days about digital film…it’s becoming so technically-orientated, and that’s just distracting from what’s actually being put in front of the lens.”

DB here:

Every now and then I get worried by the repetitive look of recent films. I want to beg filmmakers (young ones especially) to try something else.

What could they do? Start with what to avoid. They could suspend the walk-and-talk, the tendency to rely on singles, the bumpy handheld takes, the swoopy crane shots, and the urge to cut on every line of dialogue. They could back off, in other words, from intensified continuity and go for something more daring and original.

More positively, there are some relatively unexplored areas of film style that yield results that are forceful and graceful. Today’s example: ensemble staging that minimizes camera movement and cutting. Minor spoilers.

Some basics

It’s a demanding technique. Essentially the filmmaker has to shape a scene among several actors in ways that guide our attention to the key pieces of information. That guidance is done through performance, framing, lighting, and other tactics. Beyond highlighting the major points of the scene, staging can create what critic Charles Barr called “gradation of emphasis.” Because several elements of the action are all visible at once, some can become primary, some secondary; and this interplay enriches our understanding of the scene.

So take this scene from Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets (1950). A dead man has been found to carry the Bubonic plague virus, and Dr. Clinton Reed is investigating people who have come in contact with him. A restaurant owner and his wife have denied knowing the victim, but now Reed and Police Captain Warren have learned that the wife has come down with the plague. They visit the apartment, too late to save her. Her husband Mefaris comes in and learns that she has died—and that she might have lived had the couple told the truth.

The two-minute scene plays out in just two shots, both with slight panning movements. The scene’s impact owes a lot to the performances: the line readings, facial expressions, and gestures, including the wonderful way that Richard Widmark rips off his surgical mask in angry frustration. But the scene also benefits from small but significant rearrangements of the actors in the frame. This staging ties together the performance elements in a smoothly rising flow.

Here’s the scene. I’ll try to indicate some practical directing principles at work.

After Captain Warren has sent his men to find the husband, we have our principal players in the middle ground in a framing from the knees up (the plan-américain). As is common in 1940s dramas, the scene will be given added depth, not only by the patrolman behind Warren but by the junior officer Paul behind Reed, coming out of the sickroom. That depth is activated when Reed comes forward to pack his briefcase and orders Paul to burn the bedding, and Warren orders the patrolman to close the bedroom door.

The opening and closing of the door becomes an important pictorial element, but for now it simply clears the background for the two-shot involving Warren and Reed talking of the death certificate. Noise from offscreen motivates the camera’s pan left to follow Warren as he meets the husband, Mefaris, coming in.

Mefaris confronts Reed and demands to know what’s happening. When he calls his wife, Paul steps out, guiding our attention to him as a sign of death. Mefaris begins to guess. The phlegmatic patrolman, who’ll feature throughout the scene, is there to keep Mefaris under control.

The risk is that we’ll watch that centrally place cop and miss something else, so Kazan takes care to make him impassive. Later, he’ll be more distant, in shadow, and out of focus. More generally, such ancillary characters need to keep still and stare at what we’re supposed to be watching.

Mefaris comes closer to Reed, blocking our view of Paul. Reed tells him his wife is dead. Mefaris tries to go to her room, but the patrolman shows his value by restraining him—and opening up a slot for us to see Paul, who confirms Reed: “She’s dead, mister.”

This sort of unnoticeable blocking and revealing through slight shifts in actors’ position goes back to 1910s cinema but is seldom used today.

Finally accepting the grim news, Mefaris ponders and comes forward. Without cutting, Kazan has brought him and Reed into closer visibility. As ever, a Cross refreshes the composition. And as Reed asks questions, his head blocks the patrolman so that we can concentrate on Mefaris’ indignant reaction.

Mefaris’ refusal to talk is the climax of the shot. We cut to Warren at the door and the camera pans with him to confront Mefaris angrily.

Now only Reed is visible in the background, squeezed between the two faces. Mefaris finally identifies Poldi as the man they need to find. Warren shoves him down and the space, quite clenched just a moment before, opens up. As gradation of emphasis, we get Reed brushing at Mefaris’ lapel after Warren’s meaty hands have crumpled it. After Warren’s outburst, Reed’s anger at Mefaris seems to have turned into a flicker of compassion.

Warren and Reed depart, just as Paul returns to the death room and the patrolman closes the door. The final framing leaves nothing to distract us from Mefaris, brought low by grief and his fatal failure to cooperate.

Kazan is, we might say, a “post-Welles” director in that he, like many others, adopted the vigorous use of depth staging and wide-angle cinematography made famous in Citizen Kane. It’s not hard to find elsewhere in Panic in the Streets some more flagrant instances of in-your-face deep focus, with big heads and exaggerated distant points.

In the scene above, the depth is nothing like so aggressive. It is, we might say, modestly virtuoso—a clean, unnoticeable, but well-calibrated piece of staging that unfolds the action so that we always know where to look.

Why not?

I anticipate some objections from a skeptical filmmaker.

“This scene isn’t cinematic. There isn’t enough cutting and it’s lacking close-ups.”

Today, though, everybody acknowledges that cutting isn’t the be-all and end-all of cinema. Directors get lots of credit for sustaining their shots, if it’s done with a self-congratulatory virtuosity. (See Gravity, Birdman, the opening sequence of Spectre.) In particular, a lengthy walk-and-talk shot is greeted as a bold stroke. So clearly the absence of cutting is okay if you make a big deal of it.

Close-ups are important, but maybe not as much as we think. Today’s style often relies too much on close-ups, partly because people think they won’t read well on small monitors and other displays. But those displays are getting bigger and sharper. I suspect that you’d find the Blu-ray edition of Panic in the Streets plenty okay for home viewing.

“Put it another way. This is too theatrical.”

Too reliant on actors, then? But what mainstream cinema isn’t? And isn’t today’s standard style, bombarding us with facial close-ups, quite “theatrical” in making the actor—and not even the body, just the face—the center of our attention?

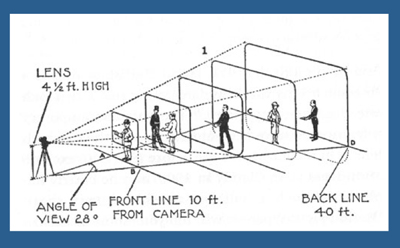

Moreover, as I’ve argued here and elsewhere, the space of a shot is the opposite of the space onstage. Theatrical space is wide and rectangular, and actors tend to arrange themselves laterally, across the stage. Cinematic space–the space captured by the camera–constitutes a pyramid, extending narrowly away from the lens, and so it favors depth. (See the diagram above.) Theatrical space is calculated for the sightlines throughout the auditorium; cinematic space is calculated for one sightline, that of the camera. Accordingly, a film can have staging in depth that wouldn’t work onstage. You couldn’t arrange the Panic scene this way in live theatre; some people couldn’t see the background action clearly, because the foreground figures would mask it.

If “theatrical” also means “too tied to the proscenium,” that objection fails too. Granted, this is a scene that suggests a missing fourth wall. The camera doesn’t penetrate the space enough to suggest the entire room. Shortly, though, I’ll show you that this approach can be more immersive, activating areas behind the camera (and so behind us).

“It’s not realistic. People don’t stand and talk that way.”

Cinema ≠ reality.

“It’s too risky. Too much can go wrong with all that shifting in one shot.”

You need skillful actors who can time their lines, hit their marks, and coordinate with one another. If one thing goes wrong, you have to start again. Shrinking from this, directors opt for plenty of coverage to adjust pacing and select the best performances during editing. “The important thing for the editor is coverage,” notes Ridley Scott. “That’s why I always have multiple cameras, so I can shorten the scene.”

So, yes, it’s risky. But risk is celebrated in the noisy virtuosity of the flamboyant long takes. Why not take risks in this more unusual way?

“It’s too hard! I never learned how to do these things.”

Once upon a time, every director knew how to stage scenes like this. The “tableau cinema” of the 1910s cultivated a rich set of creative choices about staging, and directors proved very versatile in exploring them. With the arrival of continuity editing in the 1910s, a degree of de-skilling took place, but directors still retained some sense of dynamic staging. We see it in 1930s and 1940s films too.

Now, much later, this sense is all but gone. Is ensemble staging taught in film schools? Could even our best directors of today—Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson, Quentin Tarantino, et al.—pull off a scene in this manner? Soderbergh couldn’t do it when he tried in The Good German. (I look forward to seeing if Todd Haynes makes the effort in Carol.)

On the whole, though, I agree: It’s hard today. Neither directors nor actors nor DPs are, I think, well-versed in what’s necessary to stage scenes this way. Most directors, and nearly all viewers, have simply forgotten that this rich menu of expressive techniques ever existed. So why not revive it?

Post-grad work

One other objection occurs to me.

“Ensemble staging of this sort is too modest. In an age of directorial bravura, where every filmmaker tries to punch above his weight, nobody will notice if I direct scenes this way. And getting the next job demands that my contribution get noticed. I’m competing with a lot of eye candy out there.”

I’d agree. But there is a lot of leeway in this approach for more self-conscious effects. Maybe most viewers and even filmmakers wouldn’t notice the robust delicacy of the scene above. But how about offering something more audacious that stays within the parameters of this style?

Try this earlier scene from Panic in the Streets. Reed, his assistant Paul, and local officials are now identifying the plague virus and are beginning to figure out how to deal with it. I hope I’ve primed you to notice the less-quiet virtuosity on display here.

A director today might have shown us the body, the reporters photographing it, and the medical team in one vast shot, perhaps from a high angle that craned in. Or perhaps we’d have gotten a long walk-and-talk taking Reed through a hospital corridor as he snaps out orders to all the staff involved.

Instead, Kazan leaves a lot of this material offscreen, to be inferred through details. The plaguey corpse lies just outside the lower frame line, but we won’t realize this for a while. And the reporters are offscreen, “behind us.” So we’re inside the proscenium. Part of the interest of the scene is not just following the ongoing drama but figuring out what’s going around us.

In this more complex scene, Kazan threads characters through the space, making some more prominent and then letting them fall back. He obeys Alexander Mackendrick’s dictum:

Composing in depth isn’t simply a matter of pictorial richness. It has value in the narrative of the action, the pacing of the scene. Within the same frame, the director can organize the action so that preparation for what will happen next is seen in the background of what is happening now.

We start with Reed and his team bent over the microscope. In the background a patrolman passes. For an instant the frame flares up.

Reed looks up, slightly annoyed, but when it happens again we can see that it’s the result of a photographer’s flash. In the distance, after Reed bends over, we can see the patrolman blowing his nose. Because we know that the plague is loose, that simple gesture becomes a warning. And on the big screen you can now notice the vague reflection of the photographer in the window between Reed and Paul. The second fading flashbulb tells us where to find this man’s phantom image.

So the action develops in three zones.: the cops in the distance, the team at the microscope, and the offscreen police photographers behind us. Two of these zones get closed off when the photographers leave and Reed orders the curtains drawn.

The space goes shallow as we get a succession of two-shots, the first with the health officer who comes forward and learns that he must cremate the corpse, the second with the morgue supervisor.

Now we get a pause. Reed, isolated against the curtains, stares down at the corpse, trying to work out a plan. As in the earlier scene, a simple pan brings Paul to him for a final two-shot. The serum has arrived, and this sets up the second phase of the scene.

The scene has developed around two nodes: the microscope bench in the middle ground and the still-unseen corpse in the foreground. This use of depth has fulfilled Mackendrick’s dictum, as the action around the ‘scope has prepared us for the series of one-on-one instructions Reed issues to his team. As in the earlier scene, this shot ends with the figures closer to the camera than they were at the start.

As in the earlier example, we get a cut. (Critics have often talked about single-shot scenes. What about studying two-shot scenes? I suggest we start with Mizoguchi.) Reed heads outside for another encounter, this time with a police official, who gets emphasized not through cutting but by letting his head block that of the morgue supervisor.

We pan with Reed as he goes to the corridor and the gathering group. More blocking and revealing: As Reed asks the cop about people who’ve been in contact with the corpse, he pivots and the composition frames the sniffling cop in the vanishing point.

Today a filmmaker might give us a big close-up of this poor guy, playing up his misery. But that would suggest that he’ll become an important story factor. He’s actually not in danger, so his minor status in the frame is completely appropriate.

For similar reasons, no need to cut in to Reed addressing the assemblage of men; none will prove significant. Instead, the action moves back to the foreground. First, Reed thanks the morgue attendant.

More important, and more virtuoso, is the way that the key dramatic elements in what follows are framed in a tight space between Paul and Reed in the foreground. First it’s the official in charge of cremation, then it’s the two skeptics.

Once more a shot ends in the closest framings so far. As a complaining civilian quarrels with Reed, both advance to the camera and Reed obliges him to take his medicine. The shot ends with the man wincing and lowering his head as the needle goes in; not such a tough guy after all.

Far from being simply of casual interest, these reluctant ne’er-do-wells anticipate the stubbornness and stupidity that Reed will encounter when he ventures into the city among the populace.

It seems to me that this sequence, with the flashbulbs and the curtain and the line-up for the vaccine, provides a self-assured command of craft that is as exuberant as anything in today’s flashy direction. If you can be flashy in a quiet way, this scene manages it.

This kind of staging can give cuts extra force. In the first scene, the cut to Warren ratcheted up the tension: Reed’s persuasion failed to win over Mefaris, so brute force is the next step. In the mortuary scene, the cut to the corridor as Reed passes through is more perfunctory, but it at least maintains the fluidity of the action.

A more dramatic instance of saving your cut for maximum impact comes near the climax, when Poldi is carried down a precarious staircase and his crooked boss Blackie flings his body over the railing. The cut to the extreme long-shot shocks you with how far he must fall.

There is much else to admire in Panic in the Streets; it’s a fine instance of Joe MacDonald’s location cinematography as well. I use it as simply an example of how much classical cinema has to teach us. It’s a pity that our filmmakers have unlearned some of its lessons, but it’s not too late—especially for brave young filmmakers—to relearn them.

For an example of lateral, rather than depth-based, ensemble staging, see our most popular entry, “Watching you watch There Will Be Blood.” Use the category tableau staging to access entries on the principles I’ve mentioned. The whole subject is discussed in more detail in Chapter Six of On the History of Film Style and in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. It’s also treated in my video lectures How Motion Pictures Became the Movies and CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses. The diagram of the visual pyramid is from Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford University Press, 1997), 170.

Panic in the Streets.

THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth

DB here:

By now everybody knows that Tarantino’s forthcoming The Hateful Eight was shot on film in the Ultra Panavision 70 format. This anamorphic widescreen process yields a projected aspect ratio of 2.76–in a word, humongous. An early version of it, MGM Camera 65, was employed on Ben-Hur (1959), but Panavision quickly developed a new generation of cameras and renamed the process. It wasn’t heavily used; supposedly Khartoum (1966) was the last film shot in the format.

The process by which Tarantino, ace cinematographer Robert Richardson, and the enthusiastic boffins at Panavision revived Ultra Panavision 70 is detailed in the current American Cinematographer (alas, not yet online). The production is an extraordinary tale. But what about exhibition? Luckily, the widescreen fans among us can glean a lot about that from veteran projectionist Paul Rayton’s interview with Chapin Cutler, co-owner of Boston Light & Sound. It was the task of Chapin and his team to find over 100 projectors, refurbish them, test them, and set them up in theatres all over America.

Chapin is a legendary figure in movie exhibition. Trained as a projectionist during his college years, he and Larry Shaw have made BL&S one of the very top companies for installation and maintenance of theatre projection equipment. He has supervised theatrical setups at festivals (Sundance, Telluride, TCM), industry gatherings (CinemaCon), and at some of the world’s top-notch theatres.

He’s more than a professional’s professional: He loves film and prides himself on delivering a powerhouse show. He was a natural choice for a movie geek like Tarantino to arrange the roadshow screenings of The Hateful Eight.

Chapin has discussed the nearly military precision necessary to fulfill Tarantino’s mandate in The New York Times and The Boston Globe. You should read these pieces for essential background. When Chapin added some new information courtesy of the listserv of the Art House Convergence, I jumped at the chance to include you in the audience. I know that many of our readers are keen to devour whatever they can learn about this film, one of the year’s major American releases.

So here are Chapin’s notes on how you prepare and ship out 100+ 70mm film prints.

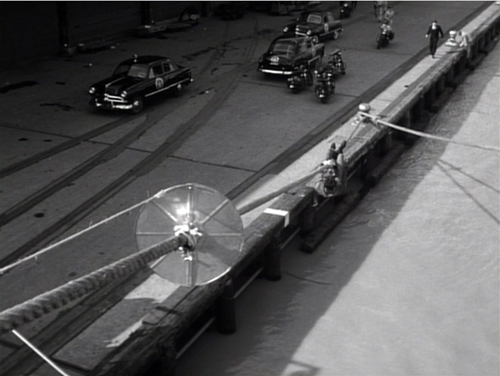

For those of you that are interested in these things, attached is a picture of our “platter farm” in Valencia CA. This is where all the prints are being made up.

The space before, in Academy ratio.

The space after, in sort of Ultra Panavision.

We are getting the prints as 1000 ft. loads, so we have to assemble 20 rolls to make a print up.

About 90 of the prints will be made up for platter operation and shipped totally assembled. The prints are being ultrasonically welded so that it is one continuous piece of film; no splices. The remaining prints are going out for reel to reel houses.

On the right of the frame above you can see part of one of the shipping cases. It is 5 ft. x 5 ft. by 1 ft. thick. When loaded, it weighs about 400 lbs. On the platter next to it, there is a partially disassembled platter reel. With the reel full, out of the box, the film and reel weigh about 250 lbs. Four people can easily lift it onto a platter deck.

We have a dedicated team of four folks working 7 days a week to get this done.

All this makes you appreciate the effort behind the scenes that makes this remarkable enterprise work. (So far, there have been a couple of problematic press screenings, but a dozen or so other shows–notably last night’s SAG screening at the Egyptian–have gone off perfectly.) Whatever you think of Tarantino as a filmmaker (I like him), he deserves credit for exposing a new generation to the volcanic fun of a roadshow presentation. And we should thank Chapin, the guru with the bandit mustache, as well.

Photo credits: Chas. Phillips.

The Hateful Eight.