Archive for the 'Directors: Vertov' Category

The ten best films of … 1929

Lucky Star

Kristin here:

As 2019 fades away, it’s time once more to look back ninety years at some great classics. This series started somewhat by accident, when we wanted to celebrate the pivotal year 1917. That was when the stylistics of the Classical Hollywood filmmaking system, which had been slowly explored for several years, finally clicked into place and became the norm in the American studios.

After that, our series became a regular and surprisingly popular feature. The point is partly just to have some fun and partly to call attention to great films that have remained obscure and/or difficult to see.

For past entries, see: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, and 1928.

After the riches of the 1920s silent film, 1929 stands out as an anomalous year. The transition to sound was under way internationally, but different countries proceeded at different paces. The new technology often was not amenable to maintaining the freedom of cinematographic and editorial style achieved during the height of the silent cinema. There are arguably not as many indisputable masterpieces from this year as from previous ones–but there are some.

Oddly enough, truly major films from this year seem to have suffered a great deal from a lack of access, both in distribution of prints and release of good (or even any) copies on home-video formats. In part I want to draw attention to the shocking neglect of some great movies.

The list is dominated by Hollywood and especially the USSR, for opposite reasons. The American studios were well into sound production, and some of the top directors found tactics for using the new technique in imaginative ways.

In the USSR, on the other hand, silents reigned. Moreover, the great directors were not lured away to work in America, as so many European filmmakers were. (For example, Murnau’s career was nearly over, and he released no films in 1929.) Thanks to them, the golden age of silent cinema continued on.

A great year for the Soviet Montage movement

The General Line (aka Old and New, dir. Sergei Eisenstein)

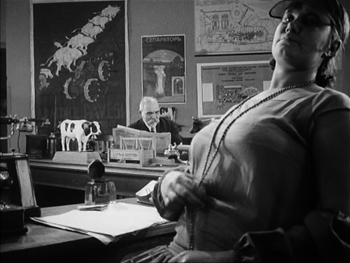

The General Line is probably the least of Eisenstein’s four silent features. The earlier films were all set before or on the very day of the 1917 Soviet Revolution, and they all have a vigor and a sense of political fervor that The General Line can’t quite match. Instead, it’s about policy, specifically the portion of the First Five-Year Plan devoted to the collectivization of private farms. Eisenstein adopts an odd tactic for dramatizing the need for such a drastic overhaul of life in the countryside. He presents a single protagonist for the first time, Marfa, a poor peasant working her land alone and without a horse for the plowing.

She becomes convinced that the answer to her and her neighbors’ plight is to create a cooperative dairy for the village. But throughout, Marfa has few allies and encounters opposition from both the local wealthy Kulaks and the poor peasants, who are portrayed as ignorant, greedy, and even violent in their determination to retain full ownership of their farms and livestock. Marfa is too weak to succeed without the support of the local government agronomist and a few like-minded farmers. The task of collectivization seems too overwhelmingly difficult to ever succeed.

In retrospect, we know about the systematic exile and execution of the Kulak class and the famines that resulted from government tactics over the coming decade. It is unpleasant to see Eisenstein, however unwittingly, providing propaganda for Stalinist policies.

Still, Eisenstein is Eisenstein, and The General Line is as formally daring as his earlier work. Apart from dramatic angles and rapid, jarring cutting, he experiments with extreme contrasts of elements within the frame by using depth compositions. These exploit wide-angle lenses and create impressive deep-focus images. In the shot above, Marfa is dwarfed by a pampered bull in the near foreground, and in a third plane beyond her we see the grotesquely fat Kulak lolling in the sun on his porch.

Other compositions create even greater contrasts. On the left, Eisenstein provides an image of bureaucratic indolence, official red-tape being a favorite (and apparently approved) satirical target for Soviet filmmakers. On the right frame, there’s a suggestion of the power of the collective’s new bull, who will sire a generation of calves.

Despite the grimness of the situation, Eisenstein manages to slip in an unusual amount of humor, and The General Line is quite entertaining.

The best DVD version I know of is the French one from Films sans frontiers, which is still available from Amazon France. The print in Flicker Alley’s “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film” is somewhat grayed out in comparison. Unfortunately this important set seems to be out of print. Flicker Alley rents The General Line online here.

New Babylon (dir. Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg)

This masterpiece by Kozintsev and Trauberg is all too little known. Information on the internet tends to come more often from musicologists, since Dmitri Shostakovich wrote the original musical accompaniment, rather than from film scholars. Many viewers have heard recordings of the score but not seen the film itself.

Kozintsev and Trauberg were the leading members of the FEKS (“Factory of the Eccentric Actor”) filmmaking group, based in Leningrad rather than Moscow. As the name suggests, the practitioners aimed not at realism, but at the grotesque, the comic, and the appeal of popular rather than high art.

New Babylon deals with the Paris Commune of 1871, a brief period when workers took over the French government. It was seen as a forerunner of the Soviet Revolution.

The title refers to a giant Parisian department store, which also seems to be in the business of putting on patriotic operettas about the current war with Germany. The store’s owner and patrons, as well as the performers in the operettas (see above) represent the bourgeoisie, while the workers who staff the store and create its products eventually rebel and run the doomed revolutionary government.

Again there is a heroine who represents the people, though she is unnamed, being known only as the shop assistant. She begins as a naive girl selling lacy clothing at the New Babylon and ends by becoming a militant revolutionary, standing atop a street barricade made up of the contents of the store–with the lace becoming bandages.

In keeping with its eccentric nature, the film mixes broad humor in the depiction of the bourgeoisie with grim tragedy as the defenders of the commune are shot in street fighting or tried and executed. The FEKS directors came from experimental theatre, but they also mastered the art of editing. New Babylon contains virtuoso sequences of crosscutting that sharpen the class struggle at the heart of the film.

New Babylon was restored in a joint venture by Dutch and German broadcasting channels and released, with the Shostakovich score, on DVD. There are Dutch and German versions, as Nieuw Babylon and Das neue Babylon respectively, which are out of print. We have the former. These retain the Russian intertitles, and, despite what the covers say, there are English and French optional subtitles as well as Dutch and German ones. (The booklet, however, is only in Dutch or German.) The quality is acceptable, but this film really needs a better restoration and Blu-ray release. It seems evident that the aspect ratio used in the current release crops the image to some extent.

Man with a Movie Camera (dir. Dziga Vertov)

I need say little about this film, since it has been widely seen, praised, and discussed. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, when many academic film scholars were obsessed with “self-reflexive,” or, less redundantly, “reflexive” films, Man with a Movie Camera was the great film. The result was, perhaps, that this admittedly very fine film was over-hyped. Nowadays it is as likely to be studied for the fact that Vertov’s wife, Elizaveta Svilova, created the very flashy Montage-style editing as it is for its reflexivity.

She is even seen doing so. At a number of points brief scenes of her examining, sorting, and splicing shots, which are subsequently seen in motion or in freeze-frames.

The film is a documentary, showing the filming, assemblage, and projection of a city symphony along the lines of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt, of two years earlier. Vertov’s version sort of a day in the life of Moscow (and glimpses of other cities), also beginning with the city waking up and going to work. Here, however, we see cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman (Vertov’s brother), with his camera and tripod traveling around the city, climbing factory smokestacks, filming from moving cars, and so on. Although many shots are straightforward documentary images, others use special effects, such as split-screen in the opening shot on the right below.

The film is available (as The Man with the Movie Camera) in Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray of Vertov’s main surviving silent and early-sound films.

Arsenal (dir. Aleksandr [or Ukrainian, Oleksandr] Dovzhenko)

Ukrainian director Dovzhenko came somewhat late to the Montage movement, contributing Arsenal in 1929 and Earth in 1930. When I was in graduate school, these were classics that everyone saw, mainly because 16mm prints were circulating. Now I wonder how many students and cinephiles see them. The standard print that has been released on DVD by a number of companies is quite poor: dark, low-contrast, cropped (though not as badly as the End of St. Petersburg version I complained about in our 1927 list).

Arsenal begins with the return of Ukrainian troops from World War I, with an emphasis on the decimation and impoverishment of the rural countryside with the loss and mutilation of many farmers. Only well into the film are we introduced to Timosha, the stalwart young representative of the proletariat who weaves through the film but does not really become a conventional protagonist.

Dovzhenko has come to be viewed as the poet of the Montage movement, and many of the scenes, especially early on, are more grimly lyrical than part of a straightforward causal chain of events. There is also a touch of what we would now call “magical realism,” as in two scenes where horses speak to their masters. Dovzhenko also employs a wide range of Montage techniques: canted shots (as above); very rapid, rhythmic cutting; jump cuts; compositions with very low horizon lines (below); and so on.

Given the importance of Arsenal, it is a shame that the old copies have not been replaced by high-quality, restored DVDs and Blu-rays. The images here are taken from the best release I know of, Image Entertainment’s old DVD. I’ve boosted the brightness and contrast, but the result is still not ideal, and the DVD is long out of print. (It’s worth seeking out, since it has a commentary track by our friend and colleague Vance Kepley.) The best version I have found is on YouTube, using the Film Museum Wien print. It’s not cropped and has a brighter, less contrasty image (on the right in the comparison above); the subtitles are in French.

Hollywood on the verge

I presume that some readers will expect to see the two official classics of early sound Hollywood, Ernst Lubitsch’s The Love Parade and Rouben Mamoulian’s Applause. Probably in the days of Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957) these were some of the rare films from the period that could be seen. They also were by major directors. Looking at them again, though, I don’t feel that they’re up there with the films below.

The Love Parade has the problem of dire sexual politics, the point being that while wives are naturally subservient to their husbands, a man put in the same position is entitled to be upset. That’s what happens when a court official, played by Maurice Chevalier, marries the queen of the mythical kingdom of Sylvania, played by Jeanette Macdonald in her screen debut. Moreover, we’re expected to find humor in a comic subsidiary plot where the official’s valet does a courtship duet with a maid, slapping her around a bit and apparently sexually abusing her in some fashion offscreen. Beyond that, though, there is a gaping plot hole that undermines the whole thing. The official is portrayed as nothing but a serial seducer, and yet when Sylvania is in financial difficulties, overnight he comes up with a brilliant plan to solve everything. In addition, after seemingly obsessed with sexual matters, he becomes bored with his marital position as the queen’s boy toy.

Applause displays rather clumsy camera movements that gave it cinematic flair in an era of clunky camera booths. But it simply seems to me not a very good film otherwise. Thunderbolt effortlessly runs rings around it.

Thunderbolt (dir. Josef von Sternberg)

Decades ago, when I taught the basic survey film-history course at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, one could still rent Thunderbolt in 16mm. I showed it the week we studied the coming of sound. Returning to it now, I still think it’s the greatest early Hollywood talkie that I’ve seen. Here’s a film that came directly after von Sternberg’s string of silent masterpieces (not counting, unfortunately, the lost The Case of Lena Smith), and before one of his best-known works, The Blue Angel.

I’m baffled by the fact that it has never been available on DVD or Blu-ray. Fans share dreadful copies of the old VHS release or off-air recordings. Fortunately Turner Classic Movies aired it some years ago, and we have a watchable, if occasionally glitchy, homemade DVD.

The plot bears a vague resemblance to that of Underworld. A tough crime boss, nicknamed Thunderbolt (again played by George Bancroft), learns that his mistress is secretly seeing a young man and plans to marry him. The resemblance stops there, however. In an attempt to invade the young man’s apartment and murder him, Thunderbolt is finally caught and sentenced to death. Much of the rest of the film takes place in perhaps the strangest death-row prison ever portrayed on film.

Von Sternberg treats sound as a gift, not an obstacle. He cuts from cell to cell, all beautifully lit and composed, while offscreen a seemingly endless supply of singers and instrumentalists perform everything from “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” from a black soloist to a group of singers rendering barbershop-quartet style renditions like “Sweet Adeline” to a classical group that seems to be passing through. Sometimes we see the source of the music, sometimes we don’t. The music doesn’t seem to have much to do with the dramatic action but perhaps reflects the eccentricities of the warden–Tully Marshall chewing the scenery even more than usual.

Speaking of music, the film also includes an early scene with Thunderbolt and his mistress visiting a Harlem nightclub. The prolific black actress Theresa Harris, in her first known role, sings “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” Now that’s using early sound well.

Thunderbolt isn’t quite up to the level of Underworld or Docks of New York. Fay Wray and Richard Arlen make a blander couple than Evelyn Brent and Clive Brook in the former film. Still, it’s a major work in von Sternberg’s career. Let’s hope one of the DVD/Blu-ray companies finally makes it available.

Lucky Star (dir. Frank Borzage)

I well remember the astonishment and delight of the audience at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1990 when the previously lost Lucky Star was shown in that year’s Borzage retrospective. A print had recently been discovered at the Nederlands Filmmuseum (now the EYE Film Institute Nederlands).

Lucky Star was originally released in silent and part-talkie versions. The restored print was of the silent version, which was lucky indeed. Having seen how awkward and distracting the recently restored talking sequences in Paul Fejos’s Lonesome are, one can only cringe at the thought of similar scenes being inserted into Borzage’s lovely film.

Lucky Star again pairs Charles Farrell and Janet Gaynor, who had been firmly fixed as the ideal romantic couple by 7th Heaven and Street Angel.

There can be few, if any films of this period where the romantic leading man spends most of the narrative in a wheelchair. Tim has suffered a grievous injury fighting in World War I, and he and Mary, a young farm girl, fall in love. Mary’s mother insists that there’s no future with a disabled man and forces her to agree to marry a sleazy, bullying soldier. Such prejudice against a “cripple” is the main underlying theme of the film.

The development of the plot is surprisingly leisurely. The first half consists largely of Mary’s visits to Tim and his attempts to help her overcome some of the slovenliness and petty dishonesty stemming from her family’s extreme poverty. There is no real goal or conflict until the intrusion of the rival soldier about halfway through. The charm of the two characters and the actors playing them carry the action effortlessly.

As with 7th Heaven, the studio-built sets are remarkable, in this case representing entire houses set amid rolling woodlands. (See top.) The acting is splendid as well. Farrell in particular is quite convincing as a man who is paralyzed from the waist down. One remarkable shot lasting 2 minutes and 40 seconds has him struggling to leave his wheelchair and use crutches instead before finally falling into the foreground. The framing remains steady until a reframing downward at the end.

Lucky Star is one of the films included in the 2008 box, “Murnau, Borzage and Fox.” So far that invaluable set is still available. Otherwise one can find English and French DVDs of it as imports.

Hallelujah (dir. King Vidor)

For the first time, a mainstream director (Vidor was at the top of his game after enjoying a huge hit with The Big Parade in 1925) and MGM, one of the Majors of Hollywood, acknowledged that a gripping melodrama could be just as entertaining with an all-black cast as an all-white cast. That is, entertaining to those outside the deep South, where exhibitors refused to play the film, robbing it of its chance to become profitable.

Well established as a classic of both early sound cinema and African-American cinema, Hallelujah retains its entertaining quality. It is easy from a modern perspective to dismiss it as racist or dependent on stereotypes. But I think that put in the context of 1929, the film was as progressive as one could expect in the day.

Vidor had long cherished the project and gave up his salary to get a greenlight from MGM. The crew was racially mixed, including an assistant director, Harold Garrison, who was black. More importantly, the musical director, responsible for the many musical numbers, was Eva Jessye, the first widely successful black female choral conductor. A few years later she would participate in the premiere of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts, and alongside George Gershwin, she was musical director for Porgy and Bess.

Vidor shot the exteriors in the Memphis area, hiring local black preachers to consult on the religious scenes, including the river baptism. He accepted changes from his cast when they found their dialogue not ringing true. In short, he struggled to be as authentic as he could.

The casting was done with particular care. Zeke was originally to be played by Paul Robeson, the most respected black performer of the day, but he was unavailable. Instead Daniel L. Haynes, a notable stage actor, got the part through having understudied Robeson in the original production of Showboat. Haynes gives Zeke a buoyant appeal that maintains sympathy for him despite his vulnerability to temptation. Nina Mae McKinney, also coming from a stage career, did the same for the seductress Chick.

Hallelujah does not have the technical polish of a film like Thunderbolt, to a considerable extent because Vidor chose to shoot so much of it on location. The tracking shots during the opening number, “Oh, Cotton,” are certainly impressive for a 1929 film. There is also some impressive night shooting during Zeke’s chase after the escaping Chick.

Hallelujah is available on DVD from the Warner Brothers Archive Collection. Unfortunately the company has chosen to put a boilerplate warning at the beginning that essentially brands Hallelujah as a racist film:

The films you are about to see are a product of their time. They may reflect some of the prejudices that were common in American society, especially when it came to the treatment of racial and ethnic minorities. These depictions were wrong then and they are wrong today. These films are being presented as they were originally created, because to do otherwise would be the same as claiming these prejudices never existed. While the following certainly does not represent Warner Bros.’ opinion in today’s society, these images certainly do accurately reflect a part of our history that cannot and should not be ignored.

I don’t think this description fits Hallelujah, but it certainly sets the viewer up to interpret the film as merely a regrettable document of a dark period of US history. Warner Bros. demeans the work of the filmmakers, including the African-American ones. The actors seem to have been proud of their accomplishment, as well they should be.

Sound and silence

Blackmail (dir. Alfred Hitchcock)

Long ago, when I first saw Blackmail, I thought it was a pretty mediocre, clumsy film. Luckily I have learned quite a bit about cinema since then and can appreciate Hitchcock’s clever use of sound–beyond just the famous “knife … knife … KNIFE” scene.

There’s the sequence where the blackmailer saunters into the tobacco store run by the heroine’s parents. He starts forcing her and her policeman boyfriend to pamper him with an expensive cigar and a good English breakfast. As he eats, he whistles “The Best Things in Life Are Free,” successfully annoying the boyfriend even further (above).

Earlier in this scene, Hitchcock presents a leisurely long take as the blackmailer performs an elaborate examination of said expensive cigar. His byplay generates suspense in us about whether he will get away with his tactic, as well as suspense in the father as to just when he is going to pay for that cigar.

The scene works well enough in the silent version of the film, but the little sound effects and muttered comments of the blackmailer make it a combination of tension and humor that wouldn’t come across without the sound. It also makes a nice contrast with the extended scene of the heroine in the artist’s studio. There the veiled threat of his seduction attempt and her naive reactions create a genuine suspense with no humor.

In contrast, there are passages of fast cutting that help avoid the stagey quality of much early sound cinema. The opening police raid and the later chase after the blackmailer through the British Museum’s Egyptian rooms (see bottom) both employ this tactic effectively.

By the way, I always thought that the giant pharaonic head in the shot where the blackmailer slides down a chain must have been a process shot, with a smaller head blow up for effect. Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray disc of the film, though, shows the label under the head well enough to reveal that it’s a cast of one of the giant heads of Rameses II from his temple at Abu Simbel (see bottom). Casts aren’t much in favor in most museums these days, so it’s no longer on display.

Pandora’s Box (dir. G. W. Pabst)

Fritz Lang, who has appeared quite regularly on these lists, released only The Woman in the Moon, his least interesting 1920s film, in 1929. Expressionism was over. In contrast, Pabst filled in with perhaps his most popular film, Pandora’s Box.

The film derives from a pair of Expressionist plays, Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box, by Frank Wedekind. The first play had been filmed in 1923, as Erdgeist with Asta Nielsen as Lulu, and directed by Leopold Jessner in the Expressionist style. It survives but is among the most difficult Expressionist films to see. Pabst combined the second half of Earth Spirit and the entirety of Pandora’s Box for his version.

The play and film both depend on the central character being played by someone who can simultaneously Lulu’s conflicting traits: her vivacious joy in living, her strange mix of generosity and selfishness, her egalitarian attitude toward others, and her naive amorality. American star Louise Brooks was perfectly cast, as were the supporting roles, including veteran Expressionist actor Fritz Kortner as the wealthy publisher who is keeping Lulu as his mistress at the film’s beginning.

Although the source material would lend itself to Expressionist designs, Pabst went for a more modern, streamlined look, as in Lulu’s apartment (below) and the luxurious home of Dr. Schön.

Pandora’s Box was issued on DVD by The Criterion Collection but is now out of print. We can hope for a Blu-ray version.

Wild and tame surrealism

I’m dividing the tenth slot for two very different short films that were in their own ways experimental masterpieces that had a considerable lasting influence.

Un chien andalou (dir. Luis Buñuel)

Few if any trends in cinema have been so dominated by a single film. Surrealism was still a concentrated movement in the late 1920s, before it diffused out internationally to become a permanent option for experimental filmmaking. With Salvador Dalí as scriptwriter, Buñuel managed to create a loose narrative centered around displaying constant incongruous juxtapositions and inexplicable occurrences. It also aimed to offend, with the opening eye-slitting, the attempted rape, and the cavalier treatment of the clergy.

Un chien andalou, being short and in the public domain, is widely available online and on DVDs issued by small companies. I haven’t seen the BFI’s Blu-ray of L’Age d’or and Un chien andalou, but that would seem to be the best bet for quality.

The Skeleton Dance (dir. Walt Disney, animator Ub Iwerks)

The Skeleton Dance is a much tamer film than Un chien andalou, a humorous, entertaining treatment of the disturbing subject of death. (Nevertheless, it was reportedly banned in Denmark as being too macabre.) The subject was apparently suggested to Disney by composer Carl Stalling, whom the director approached to do music for two earlier Disney films. Stalling was interested in creating films based on musical themes, and The Skeleton Dance became the first of Disney’s “Silly Symphonies” series.

Stalling eventually moved on to Warner Bros.’s animation unit, where he composed the music for two series modeled on (and parodies of) the “Silly Symphonies”: the “Merry Melodies” and the “Looney Tunes.” Thus The Skeleton Dance helped inspire three of the great animated series of the 1930s and beyond.

The cartoon has only the loosest of plots, running (much as the “Night on Bald Mountain” episode in Fantasia would) through the eerie events of a night through to the calming effects of dawn. The opening features a frightened owl (below left) and a howling dog, but the main “characters” are four skeletons that leave their graves to dance and cavort. Iwerks showed off his virtuoso skill, with the complex figures of the skeletons moving in circles so that they crossed over each other, as in the circular dance in the image above. He also uses two basic techniques of animation, stretch and squash, to turn the rigid bones into lively, pliable figures (below right).

The Skeleton Dance is included in the “Walt Disney Treasures: Silly Symphonies” DVD set, now out of print.

Compilations of Carl Stalling’s brilliantly zany (and surrealistic) music for the “Merry Melodies” and “Looney Tunes” were released on CDs as “The Carl Stalling Project” Volume 1 and Volume 2. Remarkably and deservedly, these are still in print after many years. If you do not already own these, hasten to buy yourself a belated Christmas present.

Conclusion: Acknowledging two notable events

The year saw Buster Keaton, who has figured so prominently in these lists, make his final silent feature, Spite Marriage. A pleasant film, but one which does not reach the heights of his great comedies earlier in the decade. Second, the earliest surviving film of Yasujiro Ozu, Days of Youth, dates from 1929. Although not top-ten material, it already displays his unique style. Assuming we continue this annual list, it will not be long before Ozu begins appearing on it.

There’s an ongoing controversy over versions of New Babylon. Specialist Marek Pytel has noted that a number of scenes were cut from the film after its premiere, thus making the new version impossible to synchronize with Shostakovich’s score. The missing footage having been rediscovered, Pytel has constructed a new print and synced it with a piano version of the score. His website on the restoration of the original version is here. Ian McDonald has written an extensive series (in three parts, here, here, and here) analyzing in complex detail the evidence for and against Pytel’s claims. Among those is Pytel’s statement that Trauberg told him that the initial version is the one that he and Kozintsev would consider definitive, while at other times the director said that the edited version as released is the preferred one.

Pytel also has claimed that Kozintsev and Trauberg wanted the musical score to be recorded and added to the film; he argues that the film should be run at 24 fps and used that running time in the small number of live performances that have so far been the public’s only access to his version. The very low-resolution clip from Pytel’s version that he posted on Youtube, however, shows the action to be distinctly too fast at 24 fps. Perhaps Kozintsev and Trauberg would have accepted this faster action in exchange for a musical track, but it would have been quite distracting.

The standard version on the Dutch/German DVD seems to me to be running at the correct, slower speed, with the music reasonably well synced.

Whether or not the standard version is the preferred one, it has long been the one we have, and it is quite brilliant as it stands. Being episodic, it does not show signs of being incomplete, though obviously one would wish to see the extra footage in the Pytel version to be able to judge.

Our friend and colleague Ian Christie, noted historian of Russian and Soviet cinema, discusses the historical context of New Babylon in a short video essay.

Blackmail.

Vertov, sound technology, and 3D: Recent Blu-ray releases

The Man with a Movie Camera.

Kristin here:

Every now and then we accumulate a few new DVDs and Blu-ray discs and write up a summary of each. This entry is the first time when all the discs discussed are Blu-ray. In fact, none of these releases is available in the DVD format.

Vertov and more Vertov

Soviet director Dziga Vertov is known primarily for The Man with a Movie Camera (1929), one of the most revered silent films. It is a documentary, an experimental film, a city symphony, and a witness to Soviet society in the late 1920s, all in one. Flicker Alley has done great service to silent Soviet cinema with its Landmarks of Early Soviet Cinema and the serial Miss Mend by Boris Barnet and Fedor Ozep. Now it has brought out a Blu-ray disc of a remarkable 2014 restoration of The Man with the Movie Camera.

This version is based largely on a print struck from the original negative and left by Vertov with the Filmliga of Amsterdam, an early cine-club. It subsequently passed to the Nederlands Filmmuseum. The restoration added clips culled from other archival prints to fill in gaps in this copy, producing an edition that will be a revelation to many who are used to the scratchy, contrasty, and cropped prints that have circulated for decades.

For one thing, seeing that missing left side of the frame makes a big difference. A booklet included with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

Yet Flicker Alley has been too modest in emphasizing this as a release simply of The Man with a Movie Camera. The full title of the release is “Dziga Vertov: The Man with the Movie Camera and other Newly-Restored Works.” Yet the “Other Newly-Restored Works,” featured in very small print on the cover, are hardly incidental. They include features that many researchers and cinephiles have long wished that they could view in good prints–or any prints at all.

These other works include most of Vertov’s famous features of the 1920s and early 1930s: Kino-Eye (1924), his first feature; Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1931), his first sound feature; and Three Songs about Lenin (1934), a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the death of Lenin.

I don’t think any of these films is as important as The Man with the Movie Camera. For me, Kino-Eye is the most charming, with candid depictions of peasant festivals and the like. It was Vertov’s first opportunity to stretch his ambitions after years of work in newsreels and documentaries. It has a spontaneity that perhaps disappeared in the later features.

The disc includes an informative booklet that discusses both the films and their restorations. As an extra, there is the 1925 Kino-Pravda newsreel episode that Vertov made to commemorate the first anniversary of Lenin’s death. It incorporates rare newsreel footage of Lenin, cutting it together in ways that look like modern gifs.

The visual quality is inevitably variable, with the earlier films looking contrasty, but these are no doubt the best versions that we are likely ever to have. This Man with a Movie Camera supersedes the one from the BFI (in the UK) and from Kino (in the USA), though many will want to have the latter for its lovely score by Michael Nyman. The Flicker Alley version has a very different, but highly appropriate, score by the Alloy Orchestra.

Not all of Vertov’s early features are included. For those who want more, Edition Filmmuseum’s release of A Sixth Part of the World (1926), The Eleventh Year (1928), both with a Michael Nyman score, and one shorter film plus a documentary on Vertov, remains a necessity.

3D curiosities

Flicker Alley has also developed a specialty in releasing DVDs and Blu-rays exploring film formats. The company has paid particular attention to Cinerama (This Is Cinerama, Cinerama Holiday, South Seas Adventure, Windjammer, Seven Wonders of the World, and Search for Paradise). Now, in celebration of the centennial of 3D exhibition , it branches out into 3D with 3-D Rarities, described as “A Collection of 22  Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

This BD brings together a thoroughly heterogeneous collection of short items, assembled into two programs. The first, “The Dawn of Stereoscopic Cinematography,” covers the years from 1922 to 1952, with short films made outside mainstream Hollywood. Some test footage by Edwin S. Porter and William E. Waddell shown in 1915 no longer survives, so the earliest films on the program are “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” (1922-23), including Thru’ the Trees, a travelogue of Washington, D. C. featuring shots of famous buildings framed primarily by foreground tree branches to create planes in depth.

The items that follow range from promotional films to animated shorts to a burlesque comedy featuring two fairly tame striptease segments and two fairly unfunny comedians. A  promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

For many the highlights of this first program will be four shorts from the National Film Board of Canada, two of them by Norman McLaren. The first, Now Is the Time (1951), uses the filmmaker’s familiar drawn-on-film style (right), while the second, Around Is Around (1951), employs an oscilloscope to create more abstract patterns.

Films by two of McLaren’s colleagues are also included: O Canada (1952) by Evelyn Lambart and Twirligig (1952) by Gretta Ekman. These films are among the only ones on the whole program where objects are not thrust or thrown “out” at the audience.

The first program ends with an advertisement, Bolex Stereo (1952), a camera which supposedly was going to bring 16mm 3D home-movies into people’s living rooms. The complicated technology demonstrated shows why the idea did not catch on.

The second program, “Hollywood Enters the Third-Dimension,” consists mainly of trailers interspersed with a few shorts. The trailers include It Came from Outer Space and Miss Sadie Thompson (both 1953). One fascinating film is Rocky Marciano vs. Jersey Joe Walcott (1953), and I say this as one who has no interest in boxing. This 16-minute black-and-white film starts at the training camps of the two opponents and moves on to the match itself, in which Marciano famously knocked out Walcott in less than two minutes. The in-ring controversy over the call occupies the last part of the film, giving the whole thing a distinct dramatic shape. Multiple-camera filming and 3D add visual interest.

Stardust in Your Eyes (1953), a comedy short starring comic and impersonator Slick Slavin (aka Slaven in the credits), is said in the program notes to have been “a big hit at 3-D festivals. Judge for yourselves, but I advise keeping a finger on the next-chapter button for this one.

Few of these shorts can be said to be important classics of the 3D repertoire, but overall one gains a sense of the surprising range of films made with the process. One also learns that thrusting guns, spears, swords, and even sling-shots toward the audience, as well as throwing stones and other missiles at them, never grow old as far as the makers of these films are concerned. We have a pistol aimed at us in one of the “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” from 1922 (below left) and a rifle in the trailer for Hannah Lee (1953, right).

At least we now have the 3D version of Mad Max: Fury Road to recharge this particular visual trope in highly original ways.

Sound marches on

Way back in 2008, when this blog was a mere two years old, I reported on the first volume of a two-disc set of DVDs inaugurating the highly ambitious project, A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures. That first volume covered the period to 1932. This one is entitled “The Sound of Movies: 1933-1975.” There was of course a lot more recorded sound in that period, and the new set stretches to four Blu-ray discs, for a total of over twelve hours of running time.

I can’t claim to have watched all those hours, but every section I sampled boasted extraordinary amounts of information. Robert Gitt, who originated the project with a 1992 lecture, again narrates. The coverage includes a huge number of rare diagrams, photographs, documents, and demo reels. In addition, many of the chapters add clips from films that contained the most innovative sound techniques of their day. The Garden of Allah, Okhlahoma!, Medium Cool, and many other titles are excerpted in superb copies.

The set as a whole is a gold mine for specialist researchers and technology buffs. The discs include long and detailed passages on such topics as push-pull recording and noise reduction, the latter a crucial challenge to the sound-recording industry for decades. Teachers who searched assiduously could find many clips suitable for classroom use.

A fair amount of the material ought to be interesting to nonspecialists too. For example, the third disc includes a history of early multi-channel and directional sound. The section on early stereophonic systems is fascinating, with its coverage of Leopold Stokowski’s participation in the two most important early films to introduce this new technology to a popular audience: 100 Men and a Girl (1937) and Fantasia (1940). We get generous clips from each. From 100 Men and a Girl, we see most of the famous scene in which an orchestra plays on different levels of Stokowski’s house and multiple channels allow sonic “close-ups” of each type of instrument over close views of that section of the orchestra:

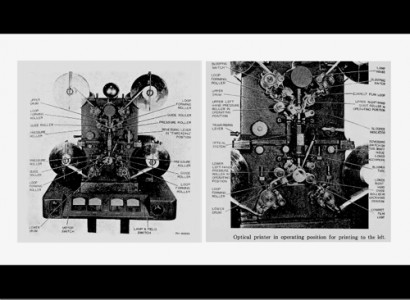

A thorough history of Fantasia includes the image below, typical of the sorts of material The Century of Sound presents: the Fantasound optical printer invented in order to print the multiple optical tracks used for the film’s stereo.

And someone obviously could not resist including a goodly dose of the short dances from the Nutcracker Suite section of the film (see bottom).

The Century of Sound is not for sale commercially. It “is available free of charge to educational, archival and research institutions and to qualified individual educators, researchers and scholars as a not-for-profit educational resource.” There is a modest fee for shipping. For information on ordering, write to CenturyofSound@cinema.ucla.edu.

Flicker Alley’s release of This Is Cinerama provoked David to a survey of Cinerama aesthetics in an earlier entry.

Fantasia.