Archive for July 2012

Beyond praise 5: Still more supplements that really tell you something

Real-time performance-capture images for The Adventures of Tintin.

Kristin here:

The Extraordinary Voyage (2011, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange)

I had expected to follow up my entry on Hugo when the DVD was released. I anticipated that its supplements would explore the flashy technical and artistic aspects in detail. But the lengthy first chapter proved to be largely the cast and crew presenting variations on how lucky they were to have worked with Martin Scorsese (and each other) and how much they learned from him.

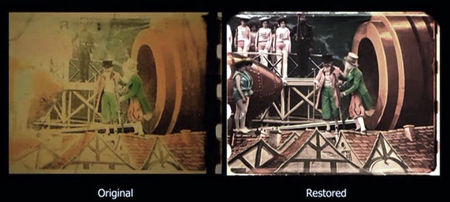

That wasn’t promising, and I turned instead to Georges Méliès himself. Flicker Alley, which has served the filmmaker so well in the past (see here), has recently released the restored color version of A Trip to the Moon in a Blu-ray/DVD combination set. It is accompanied by a 65-minute documentary on the Méliès, the film, and the restoration. It’s odd to call a 65-minute film that accompanies a fifteen-minute “feature” a supplement, but I recommend it anyway.

I suspect that The Extraordinary Voyage would be quite effective in easing students into very early silent cinema and intriguing them about an era that must seem hopelessly remote to them. It begins with a charming introduction to the context of the turn of the previous century and then moves quickly into the director’s young-adult life. When it comes to the famous incident in which Méliès’ camera jammed while he was filming, creating an inadvertent magical transformation, the filmmakers have an actual 1937 recording of Méliès himself describing the event. Presumably this was the original source of this oft-repeated anecdote. He specifies that it happened on the Place de l’Opéra and involved a bus turning into a hearse. I still wonder if it all happened so neatly, but hearing it directly from Méliès makes it a little more plausible. If it wasn’t true, it should have been.

The film includes as talking heads several filmmakers who admire Méliès’ work: Costa-Gavras, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Michael Gondry, Tom Hanks, and Michel Hazanavicius. There is a good summary of the fascination with the moon in popular culture of the day,  including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

The documentary touches on issues relevant to early silent cinema in general. One of these is the frequent pirating of films, with Méliès starting an American branch of his Star Films in New York, under the direction of his brother Gaston, to help protect his intellectual property. A clip from the Segundo de Chomon version of the film, An Excursion to the Moon, is included.

At about 23 minutes in, a short overview of early movie music is given, followed by a helpful explanation of how the hand-coloring of Méliès’ films was handled by a local workshop run by women. At 30 minutes in there are several dazzling examples of hand-colored scenes (right).

After a quick summary of Méliès’ decline and death, the film moves to the restoration of the only known hand-colored copy of A Trip to the Moon, found in the film archive in Barcelona. Here the hero is Tom Burton, the Director of Technicolor Creative Services, who gives a brief indication of how computers have transformed restoration:

We have a palette of digital tools to work from that are a collection of maybe five or six of the main commercially available restoration platforms, but then we also bring into the mix all of the approaches that you would use if you were doing visual effects for a modern movie.

The comparison of visual effects with restoration is in some ways an apt one and might lead students to look upon early films in a new light.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Blu-ray/DVD/Ultraviolet set, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

It’s probably a good idea to supply both Blu-ray and DVD discs in one package, but including the supplements only in Blu-ray is annoying and increasingly common. That’s the way the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo discs have been handled. Teachers without access to a Blu-ray player have fewer options when trying to use supplements in teaching. It also makes it much more difficult to make frame grabs from the supplements to, say, illustrate a blog entry on useful supplements.

I decided to check out the supplements for this film because the ones for Zodiac and The Social Network were so good. I figured David Fincher was particularly concerned about his films’ bonus materials. Unfortunately this set of supplements is quite uneven. The cast and crew seem to be obsessed with the character of the heroine and with the delights of shooting in Sweden. I confess that I stopped watching some of the chapters as the talking heads went on and on about these subjects. Some of the tracks also consisted of a lot of candid behind-the-scenes footage, which is all very well, but there was little structure to this and only occasional comments to explain what was going on.

Fortunately the “Post-Production” section is very informative and interesting. “In the Cutting Room” is fairly technical but makes some fascinating points. I particularly liked the description of how Fincher eliminates reframings and unsteady shots by using the extra image space allowed by newer capture media. (Earlier digital film frames allowed no extra image area outside what would show up on the screen; as the image below indicates, the final frame can be selected from a larger picture.) This desire for a stable image in an era where the “queasi-cam” so often rules points to one distinctive trait in Fincher’s style. It indicates a willingness to actually think through the framing of each individual shot and the purpose for choosing that framing. Steven Spielberg does the same thing. Many don’t.

Editor Angus Wall talks about this advantage of the extra size of the image and how Fincher uses it to stabilize unsteady images. It’s worth quoting at length, and it demonstrates the thoughtful commentary in this particular supplement:

I’ve never seen a movie that was sort of “re-operated” to the extent that this one was. Which I think has an effect on the viewing of the movie. David is really type-A in terms of making the shots very specific. They start in a certain way, they end in a certain way. And the framing, he’s very precise in terms of his composition. He doesn’t like a lot of what you see in 99% of movies, which is very subtle moves where the operator will actually reframe according to how the actor’s moving. David doesn’t like that. Even if there were a lot of those in this film, and before, some of those takes we would have thrown out, because we just wouldn’t have been able to stabilize them to the degree that he likes it. With this, because you have this full raster, this big area around the image, you can take those images and stabilize them, really lock them down. So the movie is really locked down in terms of camera operating. More than any other movie that I can think of.

The smooth glide as the car initially approaches the country house is one example of that utter stability, used to ominous effect in that particular scene.

There’s also some interesting discussion about how the two main characters don’t meet each other until well into the film and how that affected decisions about editing. Rather than frequently intercutting between Mikael Blomkvist and Lisbeth Salander, the filmmakers decided to create longer self-contained scenes involving each, thus switching back and forth less frequently. The idea was that the exposition set forth in each scene would be too difficult to absorb if it was chopped into smaller segments. Form, style, and function, neatly explained.

Fincher also points to an interesting underlying anxiety the spectator might feel because the narrative progress gives little sense of how much action is still to come:

You don’t know where you are in the narrative. You don’t know if you’re at the beginning of the third act or … I don’t think it’s bad, because we have a five-act movie. I think that’s what’s causing everybody’s anxieties, that it doesn’t feel like, OK, here’s where we are, we’re entering the third act now. Now it feels like, fuck, this movie could go on … indefinitely. That’s the part that’s bothering me. If we told them it was going on for another forty-five minutes, they wouldn’t have a problem. It’s the indefinite part.

Since I’ve written a book claiming that classical films usually don’t have three acts, I was intrigued by this statement. (See also my earlier blog entry here and David’s essay here.) I posit instead that classical films typically create acts that run about 25 to 30 minutes, and that the film’s length determines how many acts it has. Four acts is the most common throughout Hollywood’s history, but a 158-minute film would be likely to have five acts. (Has David Fincher read my book?!) His point about the audience feeling a bit lost in an unconventional narrative structure is a rare instance of a director talking about form in such an abstract way, and it seems quite valid for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

It’s also rare to get a supplement on ADR (automated [or additional] dialogue replacement), but there’s a six-minute one in the “Post-Production” section. This consists of a behind-the-scenes session with Rooney Mara supplying not just dialogue but breathing, grunts, and other noises. It’s clearly a real session, not a staged one, though the actress does seem a bit self-conscious with the documentarian’s camera turned on her. Fincher’s and Mara’s banter between takes gives a sense of what I suspect really goes on during this phase of production.

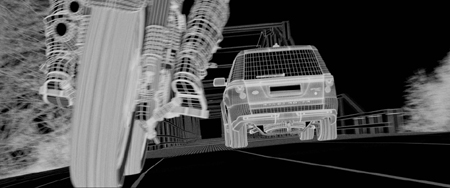

There’s a brief supplement called “Main Titles,” which deals with the form and inspiration for the CGI under the titles. Fincher wanted to tell the story of the whole trilogy in two and a half minutes, “and it has to be spectacular.” Apart from the discussion of form, there’s a good look at unrendered CGI footage compared to the finished images.

Finally, an eight-minute “Visual Effects Montage” displays a variety of special effects in a clever way. There is a section at the beginning where we are shown the image without added effects, then the same image with the areas to be altered highlighted in various superimposed colors, and finally the finished images with the effects added. This is particularly good for showing the sorts of mundane effects that are used to enhance shots unnoticeably, adding cars’ headlight beams, reflections in glass, falling snow, and the like. There is a shot with a section of a building on location blotted out with a greenscreen and the final shot showing the use of alterations in the building:

Obviously here the fog was also added with CGI.

This montage goes very quickly. If you’re using it in a class, best to prepare ahead and be ready to pause and point out what’s going on in the many short shots used in the demonstrations.

The second half of the effects montage moves to splashier scenes of the type the public associates with “special effects”: wire-frame vehicles for a chase (see image at the top of this section), head-replacement to add Mara’s head to her stunt-double’s body, and explosions.

Don’t bother with the “Stockholm Syndrome” section. Basically all we learn is that when a scene is shot on location, sheep can unexpectedly wander in and interfere.

The Adventures of Tintin (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital Copy combo, Paramount Pictures)

Again, the supplements for this release are available only in Blu-ray.

Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson decided some years ago to collaborate on what was announced to be a three-film series adapted from Hergé’s Tintin comic books. The notion was that each of them would direct one film, with an as-yet-unspecified director doing the third. Spielberg’s initiatory film did not do as well at the domestic box-office as had been hoped, though it fared better in Europe and other non-North American markets, where the comics are highly popular. Jackson has announced that after he finishes both parts of The Hobbit, he will launch into the next Tintin film. (At least, that’s what he said originally. After yesterday’s announcement that there will be three Hobbit films, his start on the Tintin film will presumably be delayed.)

The supplements form a narrative of the film’s making, bookended by “Toasting Tintin” and “Toasting Tintin Part 2,” brief episodes set at the launch and wrap parties. The tale is pleasant and generally worth watching, though they are far from as entertaining and informative as the supplements that Michael Pellerin produced and directed for Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings and King Kong DVD sets. But this is Spielberg’s show, since he did the first film and indeed originated the project. At first he envisioned the film as live-action, with the dog Snowy the only major CGI character. Spielberg asked Jackson’s effects house Weta Digital to do some tests animating Snowy. To his (apparent) surprise, Jackson himself, as a fan of the comics since childhood, played Captain Haddock in the test. That fact was well known to fans, and the inclusion of the test footage (above) is no doubt a crowd-pleaser.

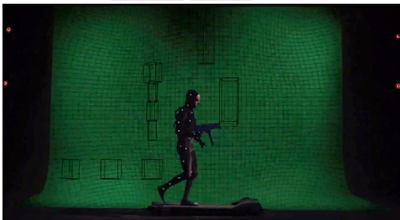

The decision to use cutting-edge performance-capture techniques led to the film being entirely animated.

“The World of Tintin” gives background on Hergé and deals briefly with the screenwriting process. This leads into “The Who’s Who of Tintin,” dealing with characters and acting, with some good material on performance capture near the end. The next section, “Tintin: Conceptual Design” has good material on the visual style of the characters and near the end includes some pre-viz material.

The outstanding supplement, however, is “Tintin: In the Volume,” nearly 18 minutes of footage concerning performance capture. Spielberg’s role as director was primarily concentrated into a remarkably short 31-day shoot with the actors. This was done in a state-of-the-art performance-capture facility called “The Volume” and located at Giant Studios. The Volume is a large space with about 160 cameras built into the ceiling and pointing down into the performance space. These capture the space from multiple angles. Additional cameras on the stage level follow the actors’ movements, which are inserted into the space. Moreover, hand-held monitors similar to portable gaming devices allow the filmmakers to see simple versions of the settings and the partially rendered characters while pointing the device at the actors in their performance-capture rigs.

There are also larger monitors that show the actors their own performances translated into the characters (top of entry). Whatever one thinks of the look of contemporary animation of this type, the technology has evolved to a remarkable level, and this supplement provides an excellent explanation of the practicalities of performance capture. We see the motion-capture suits being put on and the dots painted onto the actors’ skin. There is also information on how the set elements and props need to be transparent so that the cameras can capture the dots on the actors’ faces and costumes through them. The image at the bottom shows Jamie Bell as Tintin looking at a mock-up of the model ship. It’s made of little metal rods and rendered into a ship on the monitors.

“Snowy: From Beginning to End” is less cutesy than it sounds. It discussed the digital tool developed for modeling the dog’s fur. There’s also good stuff on how several dogs were recorded to provide different-sounding barks depending on the type of action in a scene.

The biggest tasks on the film came after the performance capture and editing. Weta Digital spent two years creating the final images. “Animating Tintin” is an excellent eleven-minute account of that process.

The sections “Tintin: The Score” and “Collecting Tintin” (on Weta Workshop’s designs for the collectible figures) are rather thin and could be skipped unless a teacher wants to show the whole set of supplements as a single “making-of” documentary.

It’s become apparent that many of the best supplements on Blu-ray and/or DVD releases are devoted to special effects, especially performance capture. The Adventures of Tintin does genuinely involve innovations in this technology, and the “In the Volume” chapter is very informative. Supplements are getting repetitive, though, and I would like to see the producers of such documentaries pay more attention to techniques and choices in other areas. Comparing final cuts of scenes with earlier cuts, or showing story conferences where real debates about scripts occur (as was done in the first Pirates of the Caribbean film’s supplements), or displaying how decisions about digital-intermediate grading are made–a bit of imagination could spice up the offerings. That and a realization that film fans are interested in just about any aspect of production (or distribution, for that matter). Supplements risk falling into conventional patterns, and that won’t make them the appealing bonus material that they used to be.

While I was gearing up to write this entry, we received Mark Parker and Deborah Parker’s book, The DVD and the Study of Film: The Attainable Text (Palgrave, 2011). Based on a great deal of research, including many interviews, the authors include a summary history of DVDs and supplements; there is a detailed chapter on The Criterion Collection, interviews with directors and scholars who have recorded commentary tracks, and a case study of Atom Egoyan.

Digital projection, there and here

Galeries Cinéma banner, Brussels, 2012.

DB here:

The Cinéma Arenberg, in the splendid Galerie de la Reine, has long been a mainstay of Brussels film culture. Since 1939, the lovely Art Deco theatre was what we Americans call an art-house. Over the years Kristin and I visited the city, the Arenberg’s autumn and spring schedules featured recent releases, but every summer the programmers plunged into plucky repertory programs. While the multiplexes ran Hollywood blockbusters, the Arenberg provided 90 or so classics and little-known releases under the rubric of Écran Total. It was here, for example, that I saw von Trier’s The Kingdom and resaw Vanishing Point. Four years ago I left a little note about the three titles I watched during my last day in town: India Song, Serpico, and Darjeeling Limited. That trio gives you a sense of how varied and interesting the programming was.

The Arenberg closed down at the end of 2011, but the cinema has reopened under new management as Galeries Cinéma. It didn’t sponsor an Écran Total season this year. Instead it offered brand-new releases on its three screens, along with some children’s programs.

Most notable for me this time was Leos Carax’s Holy Motors. Whatever you’ve heard about this film is probably accurate. I found it an exhilarating, frustrating, and continuously provocative descent into Surrealist role-playing. It’s a tour of cinema genres and an anthology of bits of other movies, from Marey to Franju, and not forgetting Carax’s own. Especially evocative were the poetic fusions, such as the way that the body stocking Oscar dons for digital motion-capture evokes both ninja outfits and the leotards of Feuillade’s Vampires. Carax films Oscar’s SPFX exercise in a way that connects Muybridge to video games and recalls the exuberantly spasmodic scene in Mauvais Sang in which Denis Lavant races madly down the street to the accompaniment of David Bowie’s “Modern Love.”

Whether you find Holy Motors infuriating or beguiling, you won’t forget it.

Exquisitely shot on digital capture, Carax’s film was given crisp, bright digital projection at the Galeries. And speaking of digital projection. . . .

The new issue of Film History, devoted to digital technology’s impact on filmmaking and film culture, includes Lisa Dombrowski’s article “Not If, But When and How: Digital Comes to the American Art House.” It’s a very fine survey of all the issues facing the art-film community at this moment. Lisa reviews the major technological and financing conditions before going into depth on a case study of three art theatres in Miami. The author of a very good book on Samuel Fuller, Lisa knows how to tie together industrial and aesthetic issues skilfully.

Another young scholar, this one at the Free University of Brussels, has concentrated on the digital transition in Europe. Since 2005 Sophie De Vinck has been studying how the conversion of theatres fits into European film policy. The result was her 2011 thesis, “Revolutionary Road? Looking back at the position of the European film sector and the results of European-level film support in view of their digital future.” The thesis, running to a whopping 769 pages, is an immense resource, and not just for people interested in digital cinema. Sophie surveys the history of national and international support of the Western European film industry, from production through exhibition, and she provides both a broad context and very specific analysis.

Part of her argument is that the “diversity” aimed at by subsidized filmmaking hasn’t been matched by diversity in audiences. But digitization offers a new chance to show films outside the dominant forms of commercial cinema and perhaps attracted new sectors of the public. “Every innovation usually brings with it possibilities for new or smaller sector players to strengthen their competitive position.” Her examination of how digital conversion affects small and art-house venues provides a complement to Lisa’s research.

I wish I’d known about Sophie’s thesis when I was writing the blogs that became Pandora’s Digital Box, but at least I can signal her work now. Best news of all: Sophie has generously made “Revolutionary Road?” available under a Creative Commons license here as a pdf. Full of valuable statistics and well-honed observations, her work helps us understand how the contemporary European film industry has survived and sometimes flourished over the last fifty years.

Cinema Arenberg, Brussels, 2008. The original design of the curved doorway and neon sign was restored in 2005-2006.

The indispensable site Cinema Treasures has a brief entry on the history of the Cinéma Arenberg/ Galeries. More extensive information can be found in Isabel Biver’s luxurious survey, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins, which I wrote about in an earlier entry.

P.S. 1 August 2012: I just learned from Gabrielle Claes that Giovanna Fossati’s book on digital restoration in film archives, From Grain to Pixel, is now available for free in pdf form here. It’s well worth reading.

Sometimes a shot . . .

I Topi Grigi, Chapter 6: Aristocrazia Canaglia.

DB here:

… just knocks you out.

In wrapping up my stay at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, where I concentrated mostly on German films of the late 1910s and early 1920s, I watched a copy of I Topi Grigi (“The Gray Rats”), a 1918 Italian serial. It’s part of an immense series devoted to the adventures of the cadaverous rogue Za La Mort. Directed by and starring the fascinating Emilio Ghione, it’s in the vein of Fantômas and Les Vampires, though I don’t find it as ingenious or funny or as skillfully directed as Feuillade’s masterpieces.

But then you get those moments. Za La Mort and his young charge Leo are aboard an ocean liner when it’s struck by a torpedo. The passengers panic and make for the lifeboats. It ought to be a spectacular scene reminiscent of Atlantis (1913), but there aren’t many shots devoted to this climax. We see only a few images of people rushing up to the deck from their cabins. The central shot showing the crisis is an image slung along the side of the ship, down the row of lifeboats as people scramble into them. The shot is interrupted by glimpses of men climbing the masts and survivors in the water, but this camera setup is the only one concentrating on the process of getting people offboard.

At first we’re looking down the row of boats, but, as you can tell from my top image, we can’t see much of anything–mostly a man in a nightshirt grabbing the hull of a lifeboat. Then, as the boat is lowered and he has to pull back, we get to see a lot more. Into the slot formed by the lifeboat supports, crisscrossed by ropes and rigging, slip faces and bits of bodies. A woman stoops, a man in silhouette shouts. Meanwhile, a dark-haired woman leans over the railing.

While our young man in the nightshirt sways precariously, the boat continues to descend and we can see even further down the row of lifeboats. A woman in the middle distance calls out. The woman at the railing has started to crawl down the side of the ship.

Now, in the depth of the shot, people are seen trying in vain to pile into the boats. Abruptly, a man on a rope swings into the shot.

The boats are edging away from the ship’s hull–a slight gap emerges in the distance–but we can see passengers still shoving to try to board them.

It’s over for these people. The lifeboats descend, the boy in the nightshirt is still stranded on the side, and the woman who has climbed down beside him vainly stretches out her arm. (See below.)

A new video essay from Flavorpill offers you “135 shots that restore your faith in cinema.” It’s mostly a collection of purty pitchers laced with emblematic moments from classics. But probably you, like me the day before yesterday, haven’t seen Topi Grigi, so my images offer no cosy film-nerd nostalgia. And compared to the Hallmark-Cards aesthetic on display in most of the video essay’s clips, this shot is pretty messy.

But it engages your vision in a dynamic way. It coaxes you to watch a process, in all its scrambling disorder, along a line of sight that emerges, gradually, as uncannily precise. Desperate faces and gestures cascade through a rigid geometry–frames within frames, receding arches like ribbing in a vault, taut diagonals slicing across the frame. Would I trade this concise, rousing, remorseless stream of images for the last forty minutes of Titanic? Yes.

Joseph North offers an admirably detailed chronology and contextualization of the series in his 2011 Masters Thesis, Emilio Ghione and the Mask of Za La Mort. It’s available as a pdf here. Thanks as well to Edward Branigan for alerting me to the Flavorpill video.

Not-quite-lost shadows

I.N.R.I.: The Catastrophe of the People (1920).

DB here:

One way to write the history of film as an art is to chart firsts. When was the first close-up, the first moving camera, the first use of cutting? Asking such questions was a common strategy of the earliest film historians, and it has persisted to this day in pop histories. Civilian readers can be excused for thinking that Griffith invented the close-up and Welles originated ceilings on sets. These myths have been recycled for decades.

The “revisionist” historians of the 1970s, mostly academics who aimed to do primary research, pointed out that talking about first times is risky. Too often the official account is wrong, and earlier instances can be found. In most cases, we can’t really know about first times. Too many films have vanished, and nobody can see everything that has survived. Innovation is always worth studying, but, the revisionists argued, it’s best understood within a context.

So they set themselves to figuring out not when certain cinematic techniques began but when they became common practice–when most filmmakers in a given time or place adopted them. That way we can discover innovations more reliably; they’ll stand out against the background of more orthodox choices. But of course, to build up a sense of these norms, it’s not enough to focus on the masterpieces cited in the official histories. You need bulk viewing.

Studying norms of storytelling and visual style is a large part of what Kristin and I have done since the 1970s. One section of our 1985 book The Classical Hollywood Cinema tried to chart when certain fundamental techniques of Hollywood storytelling coalesced into common practice. Kristin argued that the late 1910s are the key years, with 1917 as a plausible tipping point. By then, continuity editing and goal-oriented plotting, among other creative options, became dominant practices in American features. If you’re interested in blog posts touching on this, see the codicil.

Yet it’s reasonable to ask: But what happened in other countries? Was Hollywood unique, or were there comparable norms emerging in Russia, France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and elsewhere?

Several years ago, I began trying to watch as many US and overseas features from the period 1908-1920 just to see what I might find. Doing this led me to make arguments about the development of staging-driven cinema (often, but not only, European), as opposed to editing-driven cinema (usually, but not invariably, American).

A vast resource for my bulk viewing of 1910s cinema has been the Royal Film Archive here in Brussels. While the collection houses virtually every classic, it also includes films that haven’t been discussed by many historians–obscurities, if not downright rarities. Films from many countries passed through Brussels, and the archive was able to acquire copies from many distributors going back to the 1910s. Although I had watched several German films in the collection on earlier visits, this year I had a pretty concentrated dose. So as in previous years (see that codicil again), I offer you some chips from the workbench.

Cinematic scarcity

I.N.R.I.

German films of this period are of special interest for my research questions because of an unusual situation. From 1916, films from the US and nearly all of Europe were banned from Germany, and this ban held good until 31 December 1920. As Kristin puts it in her book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available as a pdf here):

Foreign films appeared only gradually on the German market. In 1921, German cinema emerged from years of artificially created isolation. . . .Because of the ban on imports, German filmmakers had missed the crucial period when Hollywood’s film style was changing rapidly and becoming standard practice. . . . The continuity editing system, with its efficient methods of laying out a clear space for the action, had already been formulated by 1917. The three-point system of lighting was also taking shape. In contrast, German film style had developed relatively little during this era.

Kristin was again exploring craft norms, the creative choices favored by Lubitsch’s contemporaries. She drew some of her evidence from films she saw here at the Cinematheque, but I wanted to revisit those and see some others. What exactly did German films look like at this point? Not the official classics like Caligari and Nosferatu, but more ordinary, maybe even bad movies?

The basic assumption: Since the German directors weren’t seeing American movies, they’d be less likely to imitate them. Some hypotheses follow from this. German directors would presumably rely less on cutting, especially within scenes, than Americans did. They might incline toward staging complicated action in a single shot. The cutting is likely to be what Kristin calls “rough continuity” or “proto-continuity”–essentially, long shots of the whole action broken by occasional axial cuts that enlarge something for emphasis. We wouldn’t expect to find sustained passages of close-up or medium-shot framings.

To give myself some reference points, on each visit I’ve watched European films in conjunction with American films of the same era. This mental trick helped differences pop out more easily.

Fortunately for peace in our household, I’ve found Kristin’s claims about German cinema well-founded. As in other years, I also stumbled across some gratifyingly strange movies.

Blocking, tackled

Throughout the period 1908-1920, we find many scenes staged in a single fixed shot. In many other blog entries, and in books like On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I’ve tried to show that this wasn’t simply a passive recording of a “theatrical” scene. Drawing on capacities specific to the film medium, directors used composition, lighting, setting, and figure movement to shape the perceptual and emotional flow of the scene.

Here’s a late example from The Brothers Karamazov (1920) directed by Carl Froelich and Dmitri Buchowetzki. Starring Fritz Kortner, Emil Jannings, Werner Krauss, and other heavyweights, it has perhaps more ham per square inch than any other film I saw on this pass. Yet its tableau moments subordinate the performers’ charisma to an overall expressive dynamic.

Old Fyodor Karamazov has been murdered, and his son Dmitri is accused of the crime. Protesting his innocence, he’s about to be arrested when Grushenka bursts out. “I’m the guilty one!”

In the tableau tradition, “blocking” takes on a double meaning–not only arranging actors in the shot, but also judiciously using them to mask or reveal areas of space. Thus Dmitri at first blocks Grushenka, but when he lowers his hands, she pops into visibility–frontal and centered, so we can’t miss her. Dmitri sinks to the lower half of the shot when her dialogue title comes up, leaving her to command the frame. Meanwhile the police official has pivoted slightly, making sure that we pay attention to her outburst. Not incidentally, he blocks another policeman behind him, keeping the frame dominated by Grushenka.

This scene goes on quite a bit longer, with some careful balancing and rebalancing of points of interest in the lower part of the frame. The action ends with a nice touch: the embracing Dmitri and Grushenka are separated, and she’s pulled away, one arm flailing.

Without benefit of cutting, then, techniques of tableau construction guide our attention smoothly in the frame by using movement, centering, advance to the camera, character looks, blocking and revealing, and other tactics.

The Germans had embraced this tableau option in the earliest 1910s. The films of Franz Hofer and others show how an entire scene could be covered in a single camera position, with staging providing a continuous flow of interest. Go here for an amusing example from The Boss of the Firm, a 1914 comedy starring Lubitsch.

The commitment persisted into later years. The earliest film I watched in this cycle, Hilde Warren and Death (1917), by the quite interesting director Joe May, had several passages of tableau staging. In the most elaborate one, the mistress of Hilde’s dissolute son tells him that now he’s out of money, she has switched her affections to a rival. It plays out without a cut or intertitle for about a minute at 18 frames per second. When Fernande spurns him, he grovels, just as the salon door opens. (Whenever there’s a rear door like this, we’re likely to get a tableau scene.) His rival shows up to take her to the opera.

Fernande asks him to stay outside, but the son demands that he stay, waving his hand. In a staging tactic that should be familiar to us now, the son rises, blocking the rival for an instant.

The rival rebalances the composition, and makes himself visible, by moving to the right background. This switching of characters’ position in the frame is known as the Cross. But when the son gets angry, the rival crosses again, easing himself toward the area of conflict. Note that the son’s bodily attitude, tensing up, actually shifts him rightward a little, opening up a space for the other actor to be seen.

Now the rival steps to the forefront and wedges himself in between Fernande and the son. He invites the young man to leave, with a gesture that occupies the dead center of the frame: Who could miss its assured insolence? And now the maid, previously in the background and blocked by Fernande, makes herself known. Seeing how things are developing, she fetches the son’s hat.

The son gets off one last grimace, front and center, before departing. As he walks back, the rival swivels to blot him out, leading the ladies in mocking laughter. (It’s clear the rival belongs to the 1%.)

One good Cross deserves another: Now the rival settles in where the son was at the start of the scene, and the son is retreating in shame along the rival’s path.

This tableau technique, constantly calculating points of interest from the standpoint of monocular projection–that is, what the camera lens takes in–is far from theatrical. Well-timed blocking and revealing wouldn’t work given the multiple sightlines of a theatre stage. The action is staged for the only eye that matters: the camera’s.

Once we grant that theatrical playing space is quite different from that provided by the camera, we can see more exactly what the tableau tradition owes to the stage. Silent cinema’s “precision staging,” as Yuri Tsivian has called it, is close to choreography. If we want to appreciate what directors of this period accomplished we need to look at the scenes as varieties of pictorialized dance, designed around the axis of the camera lens.

Along the lens axis

To return to the first question: Yes, German films seem to have clung to the tableau tradition after 1917, when Americans had abandoned it. Yet shots like those in The Brothers Karamazov and Hilde Warren are fairly rare; most scenes in most German films of the period use a fair amount of editing. What do we make of that?

The trend is fairly general. Some staging-driven films, like Ingeborg Holm (1913) and the early serials of Feuillade, are built entirely out of one setup per scene, occasionally broken by cut-ins of printed matter or other details. This period constituted a brief golden age of this “tableau” tradition–visible in American cinema, but more pervasive in European cinema. But by the late 1910s, most directors around the world were cutting up their dialogue scenes at least a little. Gradually, the tight choreography of the tableau gave way to the easier method of using close-ups to pick out key instants.

The European default seems to have been what Americans called the “scene-insert” method. A long shot (called the “scene”) is interrupted by a cut to some part of it (the “insert”). Then we go back to the orienting view. The cuts are typically straight in and back along the lens axis.

Here’s a straightforward German example from The Devil’s Marionettes (Marionetten des Teufels, 1920). A fake medium has been brought to a rich man’s home to read the fortune of his daughter. As she leaves he pays her, and from his ring she’s able to identify him as a Duke.

Note that the first setup is much farther back than the tableau scenes in Brothers Karamazov and Hilde Warren. There’s not much to be done with such a distant shot except cut in.

The Devil’s Marionettes scene has two inserts, but it’s conservative by American standards. By 1917, Hollywood directors were increasing the number of “inserts” considerably and making them the dominant source of the ongoing action. Some European directors took this option; notable instances are Abel Gance and Victor Sjöström. Others, though, relied on the scene-insert approach, not building the action out of a lot of closer views. The post-1917 German films I’ve seen, most recently and on other occasions, favor a moderate scene-insert approach like the one in Marionettes. Accordingly, the “pure” tableau option waned.

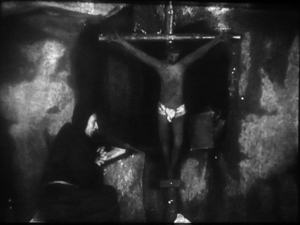

Yet one basic idea of the tableau strategy persisted. We can see this in directors’ use of the axial cut, which provides a constant orientation to the setting. While American directors were often building up a scene from many angles, German directors seemed reluctant to show the action, at least in interior sets, from distinctly varied viewpoints. So when they broke a dialogue scene into many shots, they stuck to the camera axis, cutting in and out along that. You can see that in the Marionettes scene. Consider as well this moment in I.N.R.I.: The Catastrophe of the People (1920). Within a single overall orientation, the editing enlarges or de-enlarges the three characters in the boudoir.

Even with the drastic enlargement from the first shot to the second, or from the third to the fourth, our orientation is basically the same. The staging cooperates with this strategy, making sure that all three players’ faces turn to the camera, even if their bodies are angled away from it. They’re playing to the lens axis, we might say.

When directors try to shift the angle more drastically, the consequences can be strange. In Rose Bernd (1919), an adaptation of a famous Gerhardt Hauptmann play, an axial cut has brought the bullying Streckmann striding toward the camera to meet his wife and Rose, chatting in his garden.

As he flirts with Rose, director Alfred Halm provides another axial cut, from farther back, as a neighbor woman passes in the foreground. Rose turns to look.

The print is missing dialogue titles, but there evidently was one here, as Rose comments on the woman passing. The dialogue title provides some cover for the extraordinary cut to the next shot.

The time is clearly continuous, as the woman is still walking past the garden gate, now in the distance. But Rose, Streckmann, and his wife have been completely rearranged in the frame. They’re positioned frontally, as in the I.N.R.I. boudoir example, and they create the sort of foreground/ background dynamic characteristic of 1910s cinema generally. Halm could have shown Rose’s comment and the others’ reaction by cutting back in along the axis, to a closer shot of the group in the garden (like the second one above). Instead, he shifted his camera position sharply. The new shot does highlight Rose and her gesture, but at the price of spatial coherence.

Aliens, missing shadows, and lustful monks

Tötet nicht Mehr!: Misericordia (To Kill No More!: Misericordia, 1919).

So some of our hypotheses seem borne out. Many German directors apparently adopted a conservative position toward American-style analytical editing until the ban relaxed in 1921. After that, as Kristin documents in her Lubitsch book, films by Murnau, Lang, and others employ more varied angles and less frontal staging. It seems likely that the Germans learned about this approach from the new availability of films from America and European countries (some of which were adopting the American approach).

My latest plunge into Weimar cinema yielded other enjoyments. It’s commonly said, for instance, that Germans experimented with expressive lighting effects. So did directors in many other countries, but I did find some striking uses of sparse, stark illumination. One example is the prison cell from Tötet nicht Mehr!: Misericordia (1919), above. Even more daring is this double close-up from I.N.R.I.

Harvey Dent has nothing on the conniving Russian student Alexei, half of whose face seems just scooped away by shadow. The faint shadow cast on the wall tempts us, in a weird Gestalt illusion, to see his head as partly transparent.

Another area of German expertise was special effects, and I saw plenty of sophisticated double exposures, matte shots, and split-screen tricks. As you’d expect, some of these were used to suggest hallucinations or the supernatural. At the very top of today’s entry is another image from I.N.R.I., which presents the student Dmitri’s fever dream. Below are a couple of nice ones from Lost Shadows (Verlorene Schatten, 1921). A Satanic traveling showman puts on shadow plays, but his cast is drawn from real life: He bargains with people for their shadows, and eventually leaves the hero without one.

What, finally, about what we all yearn for: an extravagantly nutty film? Nothing in this foray matches the work of Robert Reinert (Opium, Nerven), about which I’ve written in Poetics of Cinema and on the DVD restoration of Nerven. Reinert is on another plane of delirium, as mentioned in an earlier entry. Nonetheless, apart from moments in many of those movies already discussed, I found two pervasively peculiar items.

The more well-known is Algol (1920), directed by Hans Werckmeister. The sets, although designed by Walter Reimann of Caligari fame, aren’t cramped and contorted but are instead vast, geometrical, and a bit reminiscent of the Monster-Machine aesthetic of Expressionist theatre.

The plot is your everyday visit from another planet. An alien from Algol visits a coal mine and gives a loutish miner a machine that generates endless energy. (Today the Algolian could take a bribe from an oil company to head back home.) The miner becomes a tycoon controlling the world’s energy supply. This monumental fantasy (big sets, big crowds) is enacted with maniacal gusto by Emil Jannings, who spends his wealth, like all good plutocrats, on bacchanals featuring crazy dancing.

Algol is forthcoming in the Filmmuseum DVD series.

The Plague in Florence (Die Pest in Florenz, 1919) is less famous, although the script is by Fritz Lang. Directed by Otto Rippert (Homunculus, 1916; Totentanz, 1919), this tells of Julia, a woman whose all-powerful sexuality wreaks havoc on the city. Even churchmen lust for her, and eventually Florence sinks into debauchery. What redeems, if that’s the right word, the city is the appearance of a plague that strikes citizens dead in their tracks. Personified as a gaunt woman rising up from the marshes and mournfully playing a violin, the plague eventually kills Julia and her umpteenth lover.

Before this, we’ve had everything I’ve mentioned and more: a couple of fancy tableau sequences, axial cuts, wild mismatches between shots, spectacular lighting effects (e.g., catacombs, below), and hallucinatory sequences. At one point, the mad monk vouchsafes Julia a glimpse of the horrors to come by showing her a river of corpses calmly flowing underground.

Of course the monk isn’t invulnerable to Julia’s charms. Trying to pray away the impulses she arouses in him, he sees her as his Savior. Herr Rippert, Señor Buñuel is on the other line.

Who knew film history could be so surprising? You don’t get this stuff in your usual pop history. But maybe it’s better we don’t share this with the civilians.

My usual heartfelt thanks to the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, its staff (particularly Francis, Bruno, and Vico), and especially its Director, Nicola Mazzanti. Thanks also to Sabine Gross for a translation.

My previous Brussels research visits are chronicled in this blog over the years. A 2007 entry talks about my viewing method and concentrates on Yevgenii Bauer. The following year’s entry is devoted to William S. Hart. An eclectic 2009 one surveys films from Germany, France, Denmark, and even Belgium. In 2010 I went twice, once in January (watching mostly Italian diva films) and as usual in July (but no entry for that visit, consumed as I was with writing about Tintin). The 2011 entry is diverse, covering many national cinemas, and, implausibly, runs even longer than the others.

We have many other entries on film style in the 1910s. One considers how the Hollywood style coalesced in 1917; another talks about Doug Fairbanks. There’s also an entry on 1913, which discusses both Suspense and Ingeborg Holm, and there are discussions of Sjostrom as a master of both the tableau approach and continuity editing. And of course there’s plenty on Feuillade’s staging; you might start here, and perhaps pause over the mini-essay here, which talks about the director’s eventual experiments with editing. Elsewhere on the site there’s an essay on Danish cinema that echoes some points made in today’s entry. (Unlike other countries, neutral Denmark was able to send its films to Germany during the war, so there may have been some influence there.) Broader comparative arguments about this material have been sketched in a lecture I’ve given in various places, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

Interest in German cinema of the period grew after Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto held its trailblazing program published as Before Caligari, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (University of Wisconsin Press, 1991; now, alas, very rare). See also the valuable collection edited by Thomas Elsaesser, A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades (Amsterdam University Press, 1996). Kristin has an essay here on Die Landstrasse (1913), a remarkable instance of the tableau style.

As my research on the 1910s draws to a close, I’m thinking of how to synthesize and present my arguments. Originally I was considering a book, but the number of stills, and the specialized nature of the project, would probably make publishers shudder. At the moment, I’m thinking about creating a series of PowerPoint lectures, with voice-over. These would be freely available for people to use in courses if they wanted. That initiative would be another experiment in using the Web to get information and ideas out there to interested readers.

Professor Bordwell illustrates his views on visual storytelling (Algol).