Archive for the 'Directors: Hong Sangsoo' Category

Talking pictures: Wisconsin Cinematheque screenings and podcasts

Hill of Freedom (2014).

DB here:

Crises make people resourceful, and the Covid-19 virus has spurred workers in film culture to try new ways to feed movie appetites. The tactics include making films available virtually. Our Wisconsin Cinematheque has joined this movement by offering titles on a weekly basis in cooperation with friendly distributors.

Along with the virtual screenings, the crew of Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King have created podcasts discussing the movies available for viewing. This week’s program is Hong Sangsoo’s Hill of Freedom. You can see it by going here. This ingratiating movie is one of my favorite Hong titles; I reviewed it at Vancouver here.

You can hear Mike King and me discussing Hill of Freedom in our Cinematheque podcast. The series has already hosted discussions with New York Times critic Manohla Dargis and Twentieth Century Fox archivist Schawn Belston. The team has also corralled filmmakers James Runde, Dan Sallitt, Mark Goldblatt, Peter O’Brian, Mary Sweeney, and not least the wonderful Bill Forsyth. Go here for the complete list.

Thanks to Mike King, Ben Reiser, and Jim Healy for setting up this pleasant encounter. Keep in touch with our Cinematheque!

Bill Forsyth has been one of our blog’s best friends, so do check in on our encounters with him: at Ebertfest in 2008 and at Antwerp in 2015. The Antwerp visit led to a fine interview as well.

Tom Paulus interviews Bill Forsyth in the Antwerp Summer Film College of 2015.

Reporting from the Wisconsin Film Festival 2019

Hotel by the River (2018).

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival is all too rapidly approaching its end, so it’s time for a summary of some of the highlights so far.

New films from around the world

We have not quite managed to catch up with all the recent films by Korean director Hong Sang-soo, but we took a step closer with Hotel by the River. It’s an impressive film, in part by virtue of its setting. The Hotel Heimat stands beside a river which is covered in ice and snow. Even the further shore with its mountains, is reduced to shades of light gray in the misty, cold light. All of this is enhanced by the black-and-white cinematography that creates a background against which the characters and the small trees create simple, austere compositions.

The story involves an aging poet who somehow senses that he is going to die soon and settles in at the hotel to wait for death. His two sons, one a well-known art-film director with a creative block and the other secretly divorced, come to visit. A young woman who has recently broken up with her married lover is visited by a sympathetic character who may be her sister, cousin, or friend. They encounter the poet by the river, and he compliments them effusively for adding to the beauty of the scene. Conversations about life ensue. The women take naps, the men bicker. Sang-soo’s typical parallels and repetitions unfold. It’s a lovely film.

Yomeddine, an Egyptian film, created something of a stir last year when it was shown in competition at Cannes. It was a surprising choice, given that it is writer-director A. B. Shawky’s first feature.

It’s also a modest, low-budget film, and like so many such films made in countries with limited production, it’s a road movie. No need to build sets or use complex lighting. The two central characters are Beshay, dropped off as a small child at a leper colony by his father, and Obama, a young orphan who knows nothing of his birth parents. Coincidentally, they both come from Qena, a city north of Luxor on the great Qena Bend of the Nile. Longing for links to their origins, the two set out there. At first they ride in the donkey cart that Beshay uses in his work as a garbage-picker, but later, when the donkey dies, they travel on foot and occasionally by train, riding without benefit of tickets.

There’s no indication where the orphanage and leper colony are and thus how long a trek the two face. I’m pretty familiar with the Nile, but they follow the large canals and train tracks that run parallel to the river on both banks. The villages along their route look pretty much alike. Shortly into the trip, however, Shawky suddenly confronts us with the Meidum pyramid (above), which acts as a handy landmark to reveal that the pair have a long way to go. It’s Shawky’s only display of an ancient site. Beshay and Obama have no idea what it is, but they explore it and spend the night in its small chapel.

Yomeddine is a likeable film blending humor, pathos, and a little suspense as it follows the pair on their quest. It’s also a plea for tolerance. Beshay’s deformities scare off those who wrongly think that leprosy is contagious (with treatment it is not), and Obama is denigrated by his classmates as “the Nubian,” for his relatively dark skin. Their sometimes prickly odd-couple friendship is a demonstration of how people of various backgrounds, including those on the margins of society, can get along. That, I suspect, is what led Cannes programmers to include it in the competition.

Overall it’s a well-made, entertaining film, perhaps an indication that we shall see more from Beshay on the festival circuit in the future.

[April 19: Yomeddine won the Audience Favorite Narrative Feature at the Wisconsin Film Festival.]

Ralph and Venellope Back in 3D

Phil Johnston with Ben Reiser, Senior Programmer, Wisconsin Film Festival.

UW–Madison grad Phil Johnston was a key participant in the festival. Not only did he program one of his favorites, Ozu’s Good Morning (1959), but he also visited a class and ran a public event around Wreck-It Ralph 2: Ralph Breaks the Internet. Phil was a writer on both entries and co-director on the second, while also providing screenplays for Zootopia (2016) and Cedar Rapids (2011). We’re very proud of him, and we were happy to welcome him back home.

I love both the Wreck-It Ralph films, but I don’t like to go to hit movies early in their runs. We usually wait a few weeks till the crowds die down. As I recently pointed out, though, that means risking no longer having the option of seeing a 3D film in that format. So it happened with both Ralph Breaks the Internet and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Fortunately for us, the UW Cinematheque added permanent 3D capacity to its projection options, so Ralph 2 was shown in that format. The 3D much enhances the sense of being surrounded by the myriad “websites” in the scenes showing general views of “the internet,” as well as by the vehicles and netizens that flash past in their travels.

Both Ralph films display a non-stop inventiveness, and I agree with Peter Debruge’s comment that Wreck-It-Ralph “ranks among the studio’s very best toons.” The sequel is, if anything, even better. The scene in which Venellope von Schweetz confronts the full panoply of Disney princesses and tries to prove herself one of them became a classic before the film was even released.

The notion of Venellope moving from the sickly sweet “Sugar Rush” arcade game to the wildly dangerous online “Slaughter Race” (see bottom) is a great concept to begin with, and her rendition of her “Disney princess” song, “A Place Called Slaughter Race” is hilarious. The film was robbed, in my opinion, when her song didn’t get nominated for a Oscar.

The film has jokes to burn, as in the clever puns on the signs that flash in the internet and game scenes. I look forward to being able to freeze-frame the images to catch the many I missed. Unfortunately the Blu-ray release will not be in 3D. Disney has been phasing out releasing its 3D films in that format ever since Frozen, but you could for a time order such discs from abroad. (Other studios are following suit, and our 3D copy of Into the Spider-Verse is wending its way from Italy as I type.) I am told that the only 3D Ralph will be the Japanese version, at something like $80. Fortunately, it looks great in 2D as well, but I’m glad to have seen it on the big screen in 3D once.

So old they’re new again

Jivaro (1954).

Recent restorations have become a increasingly important component of our festival’s wide variety of offerings. Selections from the previous year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna are now regularly programmed, and we had visiting curators presenting their new projects. (For a brief rundown of the Bologna offerings this year, see here.)

Another film taking advantage of the Cinematheque’s new 3D capacity was Jivaro, a jungle-adventure film of the type more popular in the 1950s and 1960s than it is now. Having seen a such films when growing up, I can say that Jivaro is better than many of its type.

It was made late in the brief early 1950s vogue for 3D, so late in fact that the studio decided to release it only in 2D. One attraction of its screening at the WFF was the fact that it was screening publicly for the first time ever in its intended format. Bob Furmanek, 3D devotee and expert, introduced the film and took questions afterward; he has been a driving force in the restoration of this and many other 3D films. (His immensely valuable site is here.) Below Bob shows one of the polarizing filters used in projection booths.

The film was highly enjoyable, partly for the 3D (shrunken heads thrust into the lens and spears coming at us!) and partly for the comfortable familiarity of its genre tropes. There’s the genial South American trader who has gained the respect of the locals, the seemingly deluded adventurer with a map to a lost treasure who turns out to be right, the gorgeous woman who shows up dressed in tight blouse, skirt, and high heels, the beautiful local girl in hopeless love with a white man, and so on. (The beautiful girl was an early role for Rita Moreno, who labored as an all-purpose-ethnic bit player for years before West Side Story made her a star.) Leads Fernando Lamas and Rhonda Fleming supply beefcake and cheesecake, respectively, at regular intervals. Lamas (as you can see above) barely buttoned his shirt across the whole film. It’s hot in jungles.

For those with 3D TVs, Jivaro is already out on Blu-ray.

The Museum of Modern Art has followed up its restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) with one of Forbidden Paradise (1924). Both were shown at this year’s festival. We saw Rosita at the 2017 Venice International Film Festival and wrote about it then. In preparing my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005; available free as a PDF here), I saw an incomplete copy of one preserved in the Czech film archive–a key element in constructing this new version. Naturally I was eager to see the new scenes and much-improved visual quality of the MOMA restoration. Archivist Katie Trainor was present to explain the process, which yielded a version that is about 90% the length of the original.

Of all Lubitsch’s Hollywood films, this is the one that most looks back to his German features of the late 1910s and early 1920s. For one thing, his frequent star of that period, Pola Negri, was by now in Hollywood and worked here with him again here, their sole Hollywood collaboration. She stars in a highly fanciful tale of Catherine the Great, and the quasi-Expressionistic sets present an appropriate version of historical style. The set in the frame above (taken from a 35mm print, not the restored version) is my favorite, with its lugubrious creatures crouched atop the wall. Grotesque sphinxes? (The designer might have been thinking of the the two beautiful granite sphinxes of Amenhotep III that sit to this day by the Neva River in front of the Academy of Arts, though they were brought to Russia decades after Catherine’s reign.) Or just elaborate gargoyles?

The plot centers around a brief affair between a young officer (Rod La Rocque) and the licentious Catherine. A brief attempt at revolution flares up. All this is deftly dealt with by the Lord Chamberlain, played by Adolf Menjou, hamming it up with eye-rolls and knowing chuckles.

It’s not first-rate Lubitsch, largely lacking the lightness that one associates with the director, and which he had already achieved in his second Hollywood film, The Marriage Circle (1924). But it’s a pleasant entertainment, and the set and costume designs are visually engaging–especially in this excellent new restoration.

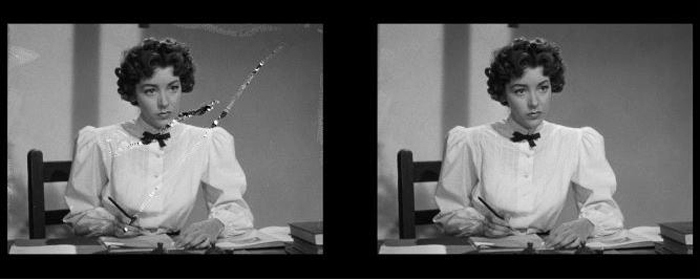

David watched None Shall Escape (1944) for his book on 1940s Hollywood, but I was unfamiliar with it until its restored version was shown here as one of the Il Cinema Ritrovato contributions. The film was originally made by Columbia and was presented at our fest in a 4K restoration from Sony Pictures Entertainment, the parent company of Columbia. Rita Belda, SPE’s Vice President of asset management, was here to explain the complicated process. She summarizes it here as well.

The film had been carefully preserved, probably because of its historical importance as a unique fictional depiction of Nazi atrocities. The original negative and three preservation positives survived. These had the usual scratches and tears, as evidenced in the first comparison image above. A significant challenge, however, was that the prints had all been lacquered in a misguided attempt to preserve them. The result was staining throughout, evident in both comparison images. Digital removal allowed for a stunningly clear image throughout the finished version.

None Shall Escape is notable as the only Hollywood film made during the war to depict major aspects of the Holocaust. It begins with a frame story set in the future. This postwar trial of Nazi criminals remarkably prefigures the Nuremberg trials. Testimony is given against a single officer, who stands in for all the accused officers and collaborators. Wilhelm Grimm begins as a schoolteacher in a small Polish city but proves so devoted to the Nazi cause that he rapidly rises through the ranks. After the city is seized during the German invasion, Grimm comes to rule the city. At the trial, townsfolk who had resisted and suffered under his domination testify, and their stories unfold as a series of lengthy flashbacks.

The film is an effective and moving drama, not least because it demonstrates the explicitness with which it was possible to depict Naziism in this period. It shows, as Hitler’s Children (1943) did, the insidious indoctrination of young people by the Nazi party. But no other film depicted the rounding up of Jews and their dispatch to concentrations camps–named as such.

Director André De Toth, though not a top auteur, again proves the value of sheer skill and artistry in filmmaking, a value that David recently discussed in relation to Michael Curtiz. None Shall Escape is an impressive example of the power of the classical Hollywood system–and a beautiful film, as one might expect from cinematographer Lee Garmes. Marsha Hunt gives a moving performance as Marja, another schoolteacher who fearlessly persists in opposing Grimm and his oppression of the townspeople; it is a pity that she never achieved the stardom that she merited.

Perhaps most notably, De Toth stages a powerful scene in which Jews rebel against being packed into trains and are ruthlessly mowed down by their captors. It must have given many Americans a first glimpse of what would soon be revealed by newsreels and personal testimony.

Now, back to the movies. More festival coverage to come, when we get time to write!

For more on early 3D, see David’s entry on Dial M for Murder.

Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018).

Christopher Nolan: Back into the labyrinth

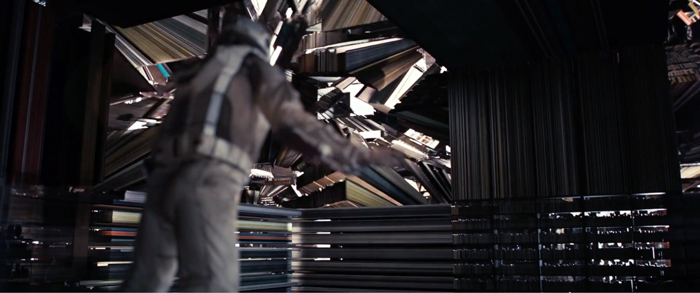

Interstellar (2014).

DB here:

A new edition of our e-book Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages has just gone into production at the hands of our web tsarina Meg Hamel. It updates our discussion of Nolan’s career by including a brand-new chapter on Interstellar and one on Dunkirk that revises and expands our blog entries on the film (here and here).

The book also includes a new chapter surveying Nolan’s approach to filmic storytelling, along with more links and frame enlargements. I wrote the bulk of this second edition, with Kristin contributing portions on exposition in Inception and Dunkirk.

As in the first edition, I try to respond to the objections that some viewers have about Nolan’s work. I grant some problems with his films, chiefly at the level of visual style. But I also try to make a case that Nolan has been exploring film narrative in ways that are significant for film history. I argue that his achievement contributes to storytelling trends of his moment (from the 1990s on) and in art and literature more generally. His work is shaped by what I call a “formal project,” akin to that we find in Alain Resnais and Hong Sangsoo.

Nolan’s detractors are likely to counter that those directors are better than Nolan. But they work in different circumstances. In the context of mass-audience Hollywood cinema, I think Nolan’s work repays scrutiny.

I’m mostly offering analysis, not evaluation. I have to admit, though, that in reworking the book and rewatching the films, I’ve come to extend my admiration for certain projects (The Prestige, Dunkirk) to others, especially Interstellar. Still, even if you don’t share my regard for the films, I think that it’s worth discussing what Nolan’s accomplishment shows about trends in modern cinema and the broader possibilities of filmic storytelling.

Which is to say, yet again, that Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages 2.0 is primarily a venture in film poetics.

We hope to make the new edition available this month or in January. It would be priced higher than the current edition, at $3.99 (i.e., the cost of a Tall Caramel Frappucino). This pays for a new design for the book, one exploiting the horizontal format for widescreen frame enlargements. We won’t be embedding video extracts in the text, as we did last time, but we may set up the clips as online links.

To the hundreds of you who bought copies over the years, thank you. We appreciate your support, and we hope that the new edition will also be worth the attention of the readers who visit this site.

Just to be clear, we’ve also welcomed the narrative explorations of Resnais and Hong Sangsoo on our website, and in our research more generally.

Interstellar (2o14).

Patchwork imagination: Lee Kwangkuk’s framed and frayed stories

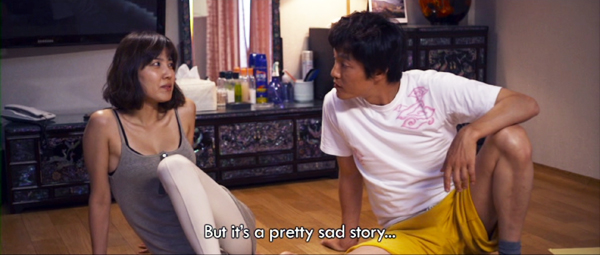

Romance Joe (2011).

DB here:

Seeing Hong Sangsoo’s The Day a Pig Fell in the Well at the 1997 Hong Kong Film Festival didn’t convince me that he was a major talent. That happened two years later, when I saw The Power of Kangwon Province at the same event, and again at Cinédécouvertes in Brussels. At Hong Kong, and again at Brussels, I saw The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2001). In those days, Hong made a movie every year or two, like your ordinary director.

I was impressed. I included Kangwon Province as an example of modern South Korean cinema in our second edition of Film History: An Introduction (published 2002), and it’s still there in our upcoming fourth edition. A year earlier, I had brought Hong to our Wisconsin Film Festival for what I think might have been his first retrospective–if three films count as a retrospective. And I drew on a scene from The Virgin as an example of subtle ensemble performance in Figures Traced in Light (2005). And I contributed an essay to Huh Moonyung’s anthology Hong Sangsoo (Kofic/Seoul Selection, 2007).

I was impressed. I included Kangwon Province as an example of modern South Korean cinema in our second edition of Film History: An Introduction (published 2002), and it’s still there in our upcoming fourth edition. A year earlier, I had brought Hong to our Wisconsin Film Festival for what I think might have been his first retrospective–if three films count as a retrospective. And I drew on a scene from The Virgin as an example of subtle ensemble performance in Figures Traced in Light (2005). And I contributed an essay to Huh Moonyung’s anthology Hong Sangsoo (Kofic/Seoul Selection, 2007).

My apologies for playing an egocentric cinephile game. Boasting aside, though, I want to express genuine satisfaction at Hong’s sustained creativity. He has become prolific but not stale; every film offers the viewer and the filmmaker himself fresh challenges. What attracts me is his simplicity of means and the way he devises narrative games that make satiric points (usually about male vanity) without seeming mannered or precious.

He has gotten ever-greater recognition, as evidenced by the current Film Comment cover story, Dan Sullivan’s perceptive appreciation of his three (!) 2017 releases. Even more startling is a real high-culture breakthrough. In its print editions over the years, The New York Review of Books has resolutely ignored Kiarostami, Kitano, Wong Kar-wai, and Hou Hsiao-hsien, to pick some exceptional directors who hit their strides in the 1990s. But the 7 December NYRB boasts Phillip Lopate’s wide-ranging essay introducing Hong to its readership.

So he’s one of those overnight successes who took twenty years. Moreover, it’s gratifying to see that recently this body of work has had some influence, most apparent for me in the work of Lee Kwangkuk. Today I want to offer some notes on an intriguing, quietly ambitious filmmaker working in the shadow of Hong.

Two shorts

Hard to Say.

Lee learned on the job, assisting on Hong’s Tale of Cinema (2005), Woman on the Beach (2006), Like You Know It All (2009), and Hahaha (2010). His films have the crystalline cinematography and color design of Hong’s, and he has learned how to make movies that consist largely of two-person dialogues, shot in long, poised takes punctuated at just the right moment by a close-up. He has cast several actors who have appeared in his mentor’s films.

As with Hong, Lee’s characters tend to be artists: filmmakers in Romance Joe (2011), actors in A Matter of Interpretation (2014), and novelists in A Tiger in Winter (2017). They have romantic liaisons, but they also spend inordinate stretches of time wandering streets, hanging out, and drinking immense amounts of soju. And like Hong, Lee has experimented with storytelling formats.

Most obviously, there are embedded stories. Early and late Hong explored a modular narrative, broken into two or three blocks, with story lines splitting or converging. At first blush, Lee developed this in a more traditional direction, inserting stories within stories, Russian-doll fashion. His two favored forms of this are the flashback and the dream.

We get both in the short Hard to Say (2012). In a playground, a young woman declares her love for a young man, who puts her off, suggesting he’s been attracted to another woman, a guitarist. “You can imagine all you want,” he says, but he’s not going to be her boyfriend.

Saddened, the woman finds a guitar abandoned in the woods, and starts to listen to it. Cut to the boy, who’s now searching for the singer who played a song he loves. (Are we in a flashback?) He finds the young woman of the first scene, but as a different character, a poised and meditative guitarist. She tells him, via a flashback, how her father forbade her to learn the guitar, so she learned to play it in her imagination, in shadow strums and plucks.

When she finally got an instrument, she found she could play it perfectly. After her tale ends, she asks him to hug her.

Abruptly we’re back on the playground, where the original young woman is waking up from sleep. Now the boy is interested in her and offers to walk her home. The guitarist’s claim for the power of imagination is vindicated.

The fact that we’re not sure where the girl’s dream begins is conventional, but also characteristic of the way that Lee frays the boundaries of his embedded stories. And the fact that the boy has fallen in love with the girl while in her dream shows the porousness of the subjective stretch that’s embedded. Hard to Say provides a miniature example of how Lee’s characteristic plot structure prompts us to see stories within stories, and then refuses to keep them sealed tight. Early in a film, we might be led to expect a solidly implanted flashback, but soon the whole frame is revealed as less objective than we might think.

The transforming power of the imagination is given a more somber treatment in another short, Soju and Ice Cream (2016). A young woman fruitlessly selling insurance policies meets an old woman who asks her to fetch some ice cream in exchange for a basket of soju bottles. In one bottle our heroine finds a slip of paper, a sort of reformation vow written by the woman: “Do not give up. Make a plan. Stop drinking. Keep smiling.” Suddenly, in what appears to be a flashback, we’re watching the old woman write the note, in an apartment tagged with Post-its. She gets a phone call from her landlord evicting her.

The old woman casually blows into a bottle she’s just drained and, as if by magic, the girl hears and feels the breath.

Now able to listen to the old lady’s phone call, she discovers that the woman’s daughter treats her as harshly as she has treated her own mother.

The girl bursts in on the old woman–in the past? in her mind?–and pours her resentment of her mother into a criticism of the old lady for taking loved ones for granted.

Back at the ice-cream stall, she snaps out of her reverie to discover that the bottles are gone and the old woman is long dead. This touch of the fantastic has given her the chance to empathize with her mother and, in a long coda, to implore her sister to heal the family wounds. Here imagination yields not wish fulfillment, as in Hard to Say, but the recovery of duty and devotion.

Dream on

A Matter of Interpretation.

A Matter of Interpretation tackles dream narratives on a bigger scale. Yeon-shin, an actress, stalks out of a brutally awful avant-garde play because, among other problems, there is no audience. As she wanders the city, she recalls breaking up with her boyfriend a year or so ago. Now, on another bench, Yeon-shin meets a detective who claims to be able to interpret dreams. So she tells her dream of attempting suicide in a car halted in a field of goldenrod.

But a thumping from the trunk interrupts her, and she finds a man tied and gagged there. He’s the detective who had asked her about the very dream he’s now in. In a flashback he explains he found himself in the car, contemplating suicide, before she arrived.

We’re left with a dream that contains a flashback, as in Hard to Say. But it’s not a veridical one, since the man finds the pill bottle empty and Yeon-shin finds it full. So it’s a dream within a dream? Moreover, her dream features a character whom the dreamer did not know…until she recounted the dream. We’re entitled to take what we see as a version of what Yeon-shin told the detective, I suppose, with him plugged into the role that some faceless man played in the original dream. Or maybe she’s just fibbing. Or maybe what we’re seeing is a free elaboration of the situation, a startling variant without any source in her mind. The uncertainty, of course, is the point.

In any case, the detective interprets Yeon-shin’s dream as being about her dumping her ex, with the recurring car symbolizing her career failure. And now he explains his skill as a dream interpreter through a flashback to his caring for his ill sister, and her recounting a dream about a customer.

As the film goes on, we get to meet Yeon-shin’s boyfriend, Woo-yeon, through a string of flashbacks framed by her telling. Later in the day, he winds up on the bench with the detective, who probes one of his dreams–in which, again, the car and the detective appear.

Back in reality, in a string of precise repetitions, Woo-yeon follows Yeon-shin’s wanderings through the streets. And that night, exhausted and depressed, she has another dream that brings Woo-yeon back into her life.

Like Hard to Say, A Matter of Interpretation offers some legible time shifts–conventional framing situations for flashbacks–in order to give the imaginary scenes escape hatches, as the detective slips into the dreams recounted by the lovers. By the end, we’ve been prepared for their paths to cross, not least because Yeon-shin’s final dream presents a reconciliation she seems to yearn for.

Telling it backwards and sideways

There aren’t any dreams per se in Romance Joe, but it’s no less committed to the zigzag contours of the imagination. The plot presents several different time schemes (although some may be fictitious), and they don’t stay neatly separate. Again, there’s a benevolent contamination of one zone by another.

A young filmmaker has disappeared. His parents come to his friend Dam Seo to investigate.

Again, what seems to be a tidy flashback shows Dam meeting with the son, who rants that he’s run out of stories.

In a standard film, we’d return to Dam Seo and the parents for more discussion. Instead we’re now in a village, where a third filmmaker, director Lee, is dumped by his producer and ordered to conjure up a story pronto. Lounging in the hotel, Lee is brought coffee by a waitress who admires one of his films, A Good Guy, for its “critical approach to narrative.” Pleased, Lee asks her to stay the night, and she agrees, for money. He reminds him, she says, of another director who visited the town, the man she calls Romance Joe.

Joe, it turns out, is the missing, unnamed director the parents are worried about; but it’s not at all clear that Dam Seo is narrating this encounter of Lee and Rei-ji. How could he know about them? His flashback simply bleeds into a new set of scenes with these other characters.

Rei-ji tells of Joe’s coming to town, and in flashback we see him wandering the streets, then checking into a hotel and trying to write. Despondent, he starts to slash his wrist. That scene is interrupted by a flashback to Joe as a teenager finding a young woman, Cho-hee, with slashed wrists in a forest. He takes her to the hospital. At this point, the flashback-within-a-flashback ends. Rei-ji, delivering coffee, finds the bleeding Joe and hurries away.

Here, about thirty minutes in, we finally return to the initial situation of Dam Seo talking to the parents about their missing son. The father is dismissive: “All these kids today wasting their lives on film.” But the mother is sympathetic to Dam Seo and asks about his work. He says he’s working on a story, and he tries it out on them. This launches what can only be called a hypothetical sequence, about a boy visiting a town in search of his missing mother. But soon enough the boy encounters Rei-ji, the coffee-girl/hooker.

And the boy’s tale frays further when it’s interrupted by a scene of Cho-hee in the forest, starting to slash her wrists and then being discovered by the teenage Joe. There’s crosstalk among what ought to be distinct realms–Dam Seo’s script versus Cho-hee’s reality, one speaker’s story versus another’s.

The rest of the film will intercut these story lines, with some peculiar interferences. Rei-ji tells Lee of meeting Joe, who says he has no more stories and is tired of them. But after spending the night with her he tells (or seems to tell) the story of himself as a teenager, and his love for Cho-hee. The stories intersect unexpectedly, with the vagabond boy revealed to be present when Rei-ji discovers Joe’s suicide attempt. Again, though, the boy is initially presented as purely fictitious, a character in Dam Seo’s uncompleted screenplay. A similar disconnected connection involves the name “Romance Joe.” It’s the nickname Rei-ji gives the anonymous director she meets, but much later in Cho-hee’s story, it’s the title of the film Joe as a student is making in Seoul. By canons of plausibility, Rei-ji could know nothing of this.

All this is hard to visualize in my prose, but I think you can see how the firm outlines of flashback episodes or embedded tales become hazy. By the end, two filmmakers want to film this tangled tale. Director Lee sees that it could become a thriller. Joe, encouraged to tell his own story by Rei-ji, seems to be rejuvenated and wants to revisit the forest of his childhood. Yet it’s not clear that either will make the movie–especially after we hear Rei-ji confide to another waitress that you just have to tell your clients what they want to hear. (So is her story about Romance Joe’s writer’s block calculated to mend Lee’s own?) The film’s final image, harking back to an Alice in Wonderland motif, suggests that the whole patchwork of stories might be pure fabulation.

Far from being a simple imitator of Hong, Lee has taken some of his experiments in fresh directions. Some of these involve abstract form, others style; his shots tend to be prettier, and he’s more likely to break a scene into reverse angles. Other differences lie in the emotional tint of the film. Hong’s films are usually comedies, however mordant. Lee’s films have a grimmer tone. Although Hard to Say is light-hearted, Soju and Ice Cream, revealing family breakup, job insecurity, and alcoholism, modulates into tearful frustration. The comic suicide attempts of A Matter of Interpretation are balanced by the melancholy prospect of aborted artistic careers and disrupted love affairs. When Jeon-shin sees the detective again in the final stretches of the film, he ignores her; their momentary friendship is over.

Romance Joe offers something grimmer than Hong’s comedy of bad manners. At the core of the story action is the sad tale of Cho-hee, scorned by her classmates, oppressed by her parents, and desperate to flee town. After her wrist-cutting episode, she and the young Joe flee to Seoul for a night, but in confusion he abandons her. She too returns home, only to leave again when she becomes pregnant (by whom?). She becomes a Seoul prostitute. Through a chance meeting Cho-hee finds that her life has become a source for Joe’s student film. She seems cheered by this, but we never see her fully grown. Joe must confront not only his feeble career but his long-ago failure to honor his promise to Cho-hee: “I’ll always protect you.” Like her and Rei-ji he bears the stigmata of a botched suicide.

This somber tone has wholly taken over Lee’s recent A Tiger in Winter. Thoroughly linear in construction, with no embedded tales, it probes an unhappy couple: a failed novelist living on the margins and his alcoholic former girlfriend, who’s found success but now suffers writer’s block. It’s a chronicle of yuppie pathos and pain in chilly urban landscapes, where we find anomie and temps morts and, again, suicide.

“In Romance Joe,” Lee remarks, “I was focused on someone that was committing suicide because they didn’t have a story any more, and in A Matter of Interpretation she didn’t have an audience any more.” In A Tiger in Winter, the characters have run out of stories and audiences. Clearly, for Hong, your prospects are bleak when you can’t summon up the redeeming power of imagination.

Thanks to Lee Kwangkuk and Tony Rayns for help in preparing this entry. Romance Joe was once available on South Korean DVD, but apparently no longer. The only Lee Kwangkuk film currently on video, as far as I know, is Soju and Ice Cream, part of an omnibus film for the Korean Human Rights Commission. Lee’s oeuvre is a real opportunity for an ambitious streaming service.

My quotation from Lee comes from an easternkicks interview. Our entries on Hong Sangsoo are here. One of them is a 2012 first impression of Romance Joe. On embedded stories in general, there’s this.

Hard to Say (2012).