Archive for the 'Film music' Category

Oscar’s Siren Song (A Slight Return): Best Original Song

One Night in Miami (2020).

Jeff Smith here:

On Monday, I offered an overview of the five nominees for Best Original Score as well as a prediction regarding the winner. Today, I do the same for the Best Original Song nominees.

The usual caveats apply for those readers interested in the online betting markets. My picks are for “entertainment purposes only.”

As we’ll see, the race in the Best Original Song category is extremely competitive. Indeed, I almost flipped a coin to make my final decision. I didn’t. But the very fact that I thought about it indicates the low level of certainty I have about my prediction.

I should add that there are a few SPOILERS AHEAD. If you don’t want to know some of the key plot twists in Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga or a small but important plot point of The Life Ahead, you can skip to the last section.

Best Original Song: The Underdog

One striking detail about this year’s nominees is the fact that four of the five function as “needle drops” introduced as the film’s closing credits start to roll. Perhaps a steady diet of television episodes streamed during the pandemic has accustomed viewers to expect that this is the way songs now function in movies. Several shows, both old and new, have used these needle drops quite creatively. (I’m thinking here of Mad Men, The Marvelous Mrs. Maysles, and WandaVision. I’m sure you all have your own favorites.)

Set off from the narrative flow of the episode, music supervisors found they could use a song as a curtain closer to highlight elements of theme, tone, or mood without worrying about things like time period or the musical tastes of the show’s characters. Such transmedial influences eventually might establish this as the primary function of popular songs in films. If this year’s nominees are any indication, the trend is already well on its way.

The one exception is “Husavik (My Hometown)” from Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga. The film, of course, is a vehicle for star Will Ferrell. He plays an Icelandic version of his usual man-child persona. It adds, though, a musical competition element borrowed from other comedies, like Pitch Perfect, and from popular music shows, like American Idol.

Ferrell plays Lars Ericksong, a humble “meter maid” whose lifelong dream is to compete in the Eurovision Song Contest. Eurovision, of course, is an annual event in real-life. It remains the longest running internationally televised music competition. The contest played an instrumental role in launching the careers of artists like ABBA, Céline Dion, and Julio Iglesias.

Lars hopes to follow in their footsteps, but his ambitions are mocked by the other residents in his small town.

Lars’ only defender is Sigrit, his childhood friend and his partner in the musical duo Fire Saga. Fire Saga plays a vital role in the town’s musical culture, performing regularly at a local bar. Yet their audience mostly rejects their musical offerings. Instead, they prefer “Ja Ja Ding Dong,” a sexually suggestive nonsense song that is the antithesis of past Eurovision winners.

Sigrit, played winningly by Rachel McAdams, is steeped in Icelandic folklore. She makes offerings to a small den of elves that she hopes will prompt Lars to return her considerable affections for him. She also believes in the “speorg note,” a mystic tone that Sigrit’s mother tells her represents the truest expression of the self.

Fire Saga enters the national competition hoping to earn the honor of representing Iceland. During an Icelandic Public Television meeting, their song is picked at random simply to meet Eurovision’s requirements for a country’s eligibility. At Reykjavik, Lars and Sigrit nervously wait backstage for their performance. Sigrit wishes that she could sing in their native language since it would calm her down. Lars, though, warns against it noting that a song in Icelandic would never win Eurovision.

Fire Saga loses to a talented competitor named Katiana, played by Demi Lovato in a nice cameo. Embittered, Lars refuses to attend a party celebrating the winner and Sigrit joins him in solidarity. When the boat hosting the party explodes, killing everyone aboard, Fire Saga becomes the Icelandic entry as the only surviving runner-up.

Once in Edinburgh, the site of the 2020 competition, Lars and Sigrit clash regarding the best way to present their music. (In reality, the 2020 Eurovision contest was to be held in Rotterdam but was cancelled due to the pandemic.) Lars wants to wow the audience with elaborate costumes and stagecraft. He also hires a K-Pop producer to remix their recording, giving it a hip new arrangement. Sigrit would rather just let the music speak for itself.

During the semi-finals, Fire Saga’s performance of “Double Trouble” seems to be going well. But Lars’ desire for showmanship backfires when the absurdly long scarf he has given Sigrit gets caught in the gears of his giant hamster wheel.

Sigrit is able to free herself before she suffers the fate of Isadora Duncan. But the hamster wheel breaks free and crashes into the audience. Although Lars and Sigrit recover just in time to finish the song, they are initially met with stunned silence. This is followed by some snickers scattered amongst the crowd. Lars and Sigrit leave the stage dejected, smarting from their humiliation.

Crestfallen, Lars returns to Húsavik, reconciled to life as a fisherman rather than a musician. Sigrit stays behind to continue her dalliance with Alexander Lemtov, a rival contestant from Russia. Sigrit is gobsmacked when she learns that Fire Saga has been voted through to the finals, a plot twist perhaps inspired by the real-life hate-watching that produced surprisingly long runs by American Idol contestants like Sanjaya Malakar.

Lars makes a mad dash back to Edinburgh, both to participate in the finals and to declare his love for Sigrit. Looking like the Gorton Fish guy, Lars sneaks onstage just as Sigrit has begun “Double Trouble.” He stops her mid-phrase and persuades her to sing a new song even though he knows the change will result in Fire Saga’s disqualification. Sigrit begins tentatively but soon grows in confidence as she reaches the chorus, sung in Icelandic much to the delight of those watching in Húsavik. The song builds to its climactic final note, a high C# that is held for several seconds, leaving both the audience and Lars rapt in awe. This time Fire Saga’s performance is met with thunderous applause. In an aside just for the viewer, Lars exclaims, “The speorg note!”

There’s a lot wrong with Eurovision. Some of the film’s gags misfire badly. The race to get Lars from the airport to the auditorium features the kind of crazy stunt work that’s grown stale from overuse. (Think spinning car and reaction shots of screaming passengers!) And at 126 minutes, Eurovision has two or even three subplots too many.

Yet the filmmakers definitely stick the landing with Fire Saga’s triumphant performance of “Husavik (My Hometown).” Seeing Lars cede the spotlight to Sigrit and her rise to the moment brings a lump to the throat, just as it does in other show-biz success stories like 42nd Street (1932) and A Star is Born (2017). (It’s an old formula but a potent one.)

Moreover, the sequence pays off several dangling causes (the reference to Icelandic lyrics in the scene backstage, the rekindled romance of Lars’ father and Sigrit’s mother, the speorg note). Even Fire Saga’s disqualification strikes the right tone by making the duo the musical equivalent of Rocky. They win by losing, content in the knowledge they were worthy contenders and in the realization of what they truly value. Watching the folks back in Húsavik swell with community and nationalist pride is just the cherry on top of a very satisfying sundae.

Any one of Eurovision’s Europop pastiches would have been worthy of nomination. For example, the faintly ridiculous quality of Lemtov’s “Lion of Love” makes it a perfect surrogate for the character’s ostentation and vanity. But only “Husavik (My Hometown)” both tickles the fancy and tugs the heartstrings.

Still, despite its appositeness for Eurovision’s story, I think it is a long shot when it comes to claiming the trophy. You have to go back to The Muppets in 2011 to find an Oscar-winning song in a live action comedy. And that was a strange year in which there were only two nominees. Before that, you have to reach all the way back to 1984’s The Woman in Red. That year, the winner was “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” written and performed by the great Stevie Wonder. Despite its considerable craft, “Husavik (My Hometown)” seems unlikely to alter a trend that rewards songs in dramas rather than comedies.

The Bridesmaid (as in “Always the…”)

This past February, Diane Warren received her twelfth Academy Award nomination for “Io Sì (Seen),” featured in the Italian film, La Vita davanti a sé. Warren has won an Emmy, a Grammy, and two Golden Globe awards, but has yet to claim an Oscar. This puts Warren in some pretty good company. Her colleague, composer Thomas Newman, has been nominated fifteen times without winning. Composer Victor Young received 21 nominations before finally breaking through with Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Sadly, Victor Young didn’t live long enough to actually receive the award. He died at age 57 just months before the ceremony.

Warren’s latest effort, “Io Sì (Seen),” is the type of soaring power ballad she has spent much of her professional life perfecting. The song starts with a modest piano figure that accompanies Laura Pausini’s indomitable voice at a moderate tempo. The lyrics offer a simple but powerful declaration of emotional support regarding the need to be “seen.” Pausini’s voice rises in the chorus as she vows in Italian, “But if you want, if you want me, I’m here.” The addition of a string orchestra and tasteful percussion accents provides additional emotional heft.

The modest arrangement allows the song’s simple beauty to shine through. Its mood and Pausini’s vocal delivery seem miles away from the bombast that made Aerosmith’s “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing,” one of Warren’s earlier nominees, a chart-topping single.

For me, though, that is all to the good. La Vita davanti a sé is itself an unassuming coming-of-age tale that depicts the unlikely friendship that develops between Madam Rosa, an elderly Holocaust survivor, and Momo, a 12-year-old orphan from Senegal.

Buoyed by Sophia Loren’s valedictory performance, the song reflects the strong filial bonds that form when Momo becomes Rosa’s ward. The lyrics’ reassurance that “I’m here” capture the ways in which Momo and Rosa have learned to care for one another. Placed just after the funeral ceremony that closes the film, “Io Sì (Seen)” sustains the scene’s bittersweet, melancholy tone and carries it into the credits. The song also reiterates the story’s central themes regarding the need for unconditional acceptance and love’s ability to overcome differences in gender, race, and age.

La Vita davanti a sé has become an unlikely hit for Netflix. At the peak of its popularity, it reached the streaming service giant’s top ten in 37 different countries. Perhaps that sleeper success will bolster Warren’s chances among Academy voters. She is eminently deserving of the award as a sort of career honor.

Could this be Warren’s year? Perhaps. Still, the fact that more famous songs by Warren, like “Because You Loved Me” and “How Do I Live,” also suffered defeat raises some doubts.

Panthers and Boxers and Yippies (Oh My!)

The three remaining nominees are all songs featured in films that look back at the legacy of sixties political activism. Unlike Eurovision Song Contest and La Vita davanti a sé, Judas and the Black Messiah, One Night in Miami, and The Trial of the Chicago 7 all received multiple nominations. Often the halo effect created by that reflected glow can make a difference in very competitive races. Moreover, the two titles receiving Best Picture nominations – Judas and Chicago – also benefit from the massive “For Your Consideration” ad campaigns that appear in trade publications like Variety. All of this suggests that, if you are looking for this year’s winner, you might look here.

Let’s start with “Fight for You,” the groovin’ track by H.E.R. that closes Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah. The song self-consciously evokes music from the period depicted in the film. As H.E.R. told Variety, she wanted the music to have a hopeful vibe, but lyrics that connected to the Black Panthers’ historic fight against injustice. She drew upon the classic soul music of Marvin Gaye, Nina Simone, and Sly and the Family Stone, artists who made records that were both popular and politically astute.

The final product is a remarkable synthesis of these different elements. The syncopated brass and organ chords recall vintage Sly and the Family Stone tunes like “Stand.” The spare but funky bass line and the supple guitar melody wouldn’t be out of place on Gaye’s classic, “Let’s Get it On” while the doubling of H.E.R.’s voice, sometimes in octaves and sometimes in thirds, conjures up his masterful What’s Going On album. The string arrangements and choral melody also bring to mind Curtis Mayfield’s classic score for Superfly (1972) for good measure. Only one of the five nominees will make you want to get up dance, and this is it. With its Funk Brothers arrangement and uplifting social message, “Fight for You” educes a bit of folk wisdom from P-Funk guru George Clinton: “free your mind… and your ass will follow.”

Celeste and Daniel Pemberton’s “Hear My Voice” from The Trial of the Chicago 7 also evokes sixties soul, albeit with more of pop flavor and even a dash of Northern soul. Celeste grew up around Brighton on England’s southern coast. Her interest in music was nurtured by her early exposure to American jazz vocalists like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. Those influences can be heard in Celeste’s elegant phrasing on “Hear My Voice.” (Beware ads.) But her vocal style has also drawn comparisons to more contemporary British soul singers like Amy Winehouse and Adele.

The end result doesn’t slavishly duplicate any of those other singers, emerging as something else entirely. In fact, although Celeste’s voice has a timbre all her own, to my ears, the slightly retro vibe of “Hear My Voice” evokes sixties pop and blue-eyed soul artists like Dionne Warwick and Dusty Springfield. The song itself is a mid-tempo ballad with a loping, syncopated beat and an arching upward melody furnishing the tune’s main hook. Pemberton’s arrangement heightens the pop elements in the recording by emphasizing the piano and strings climbing steadily upward.

The Trial of the Chicago 7’s title is fairly self-explanatory, dramatizing the prosecution of activists from the Black Panthers, the Yippies, and Students for a Democratic Society after protesters violently clashed with police at the 1968 Democratic Convention. David’s blog on Aaron Sorkin shows, among other things, how the screenwriter/director drew upon the “drama of ideas,” a tradition associated with “turn of the century” playwrights like Henrik Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw. In a slight break from that tradition, though, Sorkin sought to end the film on a note of optimism and hope that would yield a sense of empowerment.

According to Pemberton, the director’s first choice for an end-title song to reflect that tone was the Beatles’ classic from Abbey Road, “Here Comes the Sun.” The composer, though, gently persuaded Sorkin to try something fresh, a new song unburdened by the enormity of the Beatles’ legacy. He also reminded Sorkin of the huge licensing fees that any Beatles song would inevitably command. Pemberton and Celeste’s much-deserved Oscar nomination vindicates the composer’s instincts. Had Sorkin used “Here Comes the Sun,” viewers would have soaked in its upbeat vibe. But The Trial of the Chicago 7 would have gotten only five nominations rather than the six it ultimately received.

Last, but certainly not least, we have Leslie Odom Jr. and Sam Ashworth’s “Speak Now,” featured in Regina King’s directorial debut, One Night in Miami. The film offers a fictionalized account of a fabled meeting of four icons of the 1960s: Malcolm X, Jim Brown, Muhammad Ali, and Sam Cooke.

The group assembles in a room at the Hampton Hotel to celebrate Ali’s victory over then heavyweight champion Sonny Liston. Yet, with only some vanilla ice cream and a flask of booze as party favors, the good-natured banter soon devolves into a debate about the best ways to achieve social change on the path toward racial equality.

Both musically and lyrically, “Speak Now” seems keyed to an important scene in the film where Malcolm chides Cooke for recording trifling love songs rather than music that speaks to the ongoing struggle for civil rights. He pulls out a copy of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and plays “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Malcolm then asks Sam why it is that a white boy from Minnesota makes music that seems so perfectly attuned to the historical moment. Isn’t “Blowin’ in the Wind” the type of song Cooke should write? Malcolm’s criticism becomes a dangling cause that is picked up in the film’s epilogue. As a guest on The Tonight Show, Sam performs “A Change is Gonna Come” for the first time, showing how he embraced Malcolm’s challenge to him.

Beginning with a syncopated acoustic guitar riff, “Speak Now” not only recalls several moments of the film where Cooke pulls out his own guitar, but also evokes the type of folk music that was Dylan’s stock in trade during the early sixties. The guitar is soon joined by a swirling Hammond B-3 organ. The instrument’s timbre evokes both the gospel music that inspired Cooke throughout his career and Al Kooper’s distinctive organ stylings on two Dylan masterpieces recorded after he went electric: Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. Floating above both is Odom’s plaintive voice, urging the film’s viewer to “Listen, listen, listen.” Providing the link between past and present, the lyrics entreat the audience hear to the “echoes of martyrs” and the “whispers of ghosts.” Odom’s soaring falsetto suggests both vulnerability and hope. The song gradually builds, adding strings and percussion, until it reaches a rousing climax.

With its simple arrangement and its mixture of styles, “Speak Now” sounds like the musical child that Bob Dylan and Sam Cooke never had the opportunity to conceive. It provides a fitting end to One Night in Miami by reminding us that the struggle for civil rights continues, especially at a historic juncture where America is challenged to confront the structural and institutional foundations of white privilege and white supremacy.

Prediction

On Oscar night, I will be watching with bated breath to see if…..

…singer Molly Sandén hits the “speorg note” during the performance of “Husavik.” If she does, it will bring down the house (or at least break a few champagne glasses).

But the winner? Your guess is as good as mine. This is among this year’s most competitive races. In Variety, Jon Burlingame notes that Diane Warren’s past nominations made her the early favorite, but adds, “You can’t count out anyone, however, in this year’s level playing field.”

If the vote reflects the song that is most clearly integrated into the film’s story, it’s “Husavik.” It is also rumored to be making a late charge, aided by late campaigns by Netflix and the tiny town of the title.

If, on the other hand, the vote reflects the song that I’d want next in my iTunes queue, it’s “Fight For You.” It’s got a funky groove that just keeps on keepin’ on.

That being said, I don’t think either of those two songs will carry the day. Ever since the nominations were announced, it’s generally felt like a two-horse race: Diane Warren vs. Leslie Odom Jr. The voting could split between those who desire to finally recognize Warren after so many nominations and those who find Odom deserving of the award for Best Supporting Actor but who still voted for Daniel Kaluuya instead.

The fact that Odom is a double nominee would seem to help his chances. But his song’s social significance also gives it a slight edge. In 2015, Common and John Legend took home the prize for “Glory,” their inspirational song from Selma. Like “Speak Now,” the lyrics of “Glory” captured the zeitgeist surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement, particularly the protests in Ferguson, Missouri. The message of “Speak Now” is just as relevant and just as timely. It is possible that voters will want to acknowledge it for that very reason.

Still my gut tells me this is Diane Warren’s year. Thirty-three years ago, Warren sat in the venerable Shrine Auditorium as a first-time nominee. She came in with a fighter’s chance. Her song, Starship’s “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now,” had a fighter’s chance having hit the top of the charts in five different countries, eventually earning gold or platinum record status in four of them. But it was aced out by an even more popular song, “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life” from Dirty Dancing. It had gone to #1 in six countries and earned gold or platinum status in seven different markets.

Warren’s been waiting ever since for a chance to pop the cork in a champagne bottle at an Oscars afterparty. I think the bubbly finally flows for her this Sunday.

Once again, a shoutout to Jon Burlingame for his coverage in Variety of the Academy Awards’ music categories. His analysis of the Best Original Song nominees can be found here, here, and here.

To find short interviews with all of the songwriting teams, check out these items from The Hollywood Reporter and Billboard.

A podcast with H.E.R. discussing her collaboration with Tiara Thomas and D’Mile on “Fight For You” can be heard here.

A very long interview with Daniel Pemberton describing his work on The Trial of the Chicago 7 can be found here.

Leslie Odom Jr. talks about writing “Speak Now” here and here.

Finally, Diane Warren performs a medley of all twelve of her Oscar-nominated songs here.

Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga (2020).

Vancouver: First sightings

Big Tech as Pac-Man: The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

DB here:

Every festival has had to adjust to COVID-19. This year the venerated Vancover International Film Festival continues with some in-person events at the VIFF Centre and the Cinematheque, but most of the screenings are done remotely. The streaming resource is available only in British Columbia and is a wonderful option for regional cinephiles.

Over the next two weeks, we’ll continue our annual tradition of covering some of the outstanding films mounted by this superb festival. As usual, we hope to guide local viewers while the event is in progress and to signal readers about upcoming releases in their territories.

Deep dives

Undine (2020).

No lyrical drone vistas, no establishing shot, no title telling us where and when we are, no voice-over trying to lure us in. Just bam, here it is, deal with it. Any movie that starts with a reaction shot in OTS (over the shoulder) of a fiercely downcast woman gets points automatically. The fact that she goes on to threaten to kill the man she’s talking to is just a bonus.

That threat, made by the protagonist of Christian Petzold’s Undine, is about the only hint that she’s capable of homicide. She seems otherwise a well-adjusted young woman free-lancing as a guide in Berlin’s Urban Development Center. As in other Petzold films, thriller conventions are invoked but suspended while a deepening personal drama emerges. At first, we tag along with Undine in her rebound-affair with Christophe, an engineer specializing in repairing underwater equipment. All is going well enough, but there are signs of trouble, particularly a near-death experience in a lake. Then, after the midpoint, tension ratchets up with two quick twists that put new pressure on Undine to take violent action.

Sorry to be so oblique, but this is one of those movies with a real plot, and since it’s eventually coming to the US, I’m avoiding spoilers. Admittedly, the last twenty minutes take off into new territory, and I found myself unable to know what to expect next. (It’s one of those movies that seems to end several times. That is often a good thing.) But the unruffled precision of Petzold’s direction, the thriftily paid-out backstory, and his gift for suspenseful storytelling mitigate the quasi-supernatural tint of the twists. I tend to see them as GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema), ambiguous moments that may flow from the characters’ imaginations.

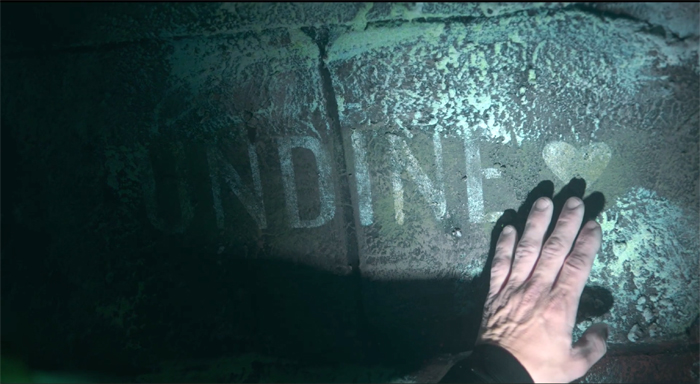

An undine is a water nymph, the heroine’s lover is a diver, her job is to lecture on the rebuilding of Berlin over the years, and his job is to explore a submerged city (which hosts a slab bearing her name). All this was for me a reminder that ambitious directors can invest genre conventions with poetic lyricism. Admirers of Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and Transit (2018) will need no urging to visit a film I found completely absorbing.

A film from two billion years from now

Last and First Men (2020).

On the visual level, Jóhann Jóhannsson’s Last and First Men is a good example of what we call “abstract form” in our book Film Art. The filmmaker builds a film out of patterns of sensuous visual qualities. Everyday objects can yield these qualities (our example is Ballet Mécanique), but abstract form can also be found in unusual, even unidentifiable sources.

That’s what we get here. The shots reveal structures and textures in immense, brutal constructions of metal, stone, and cement. Are they sculptures? Totems of some bizarre religion? Remnants of blasted modernist buildings? Fragments of space ships crashed to earth? The moving camera reveals their shapes, textures, and off-kilter strains for symmetry. You lose all sense of scale: these might be the size of dinner tables or tabernacles. Most are set against the sky, alternately misty or searingly bright.

No story connects our views of these strange monuments. On the soundtrack, though, a woman’s voice recounts the history of the future. After two billion years, the narrator represents the “eighteenth species” of humans, and via telepathy she informs us of the impending end of human life on Neptune.

We never see any of those events, just the ruins calmly surveyed by the camera. Almost never does the commentary sync up with the shots. The woman’s account of future humans might at first seem to match the carved, staring blocks we see, but she goes on describe them as furry or translucent.

The disparity between description and depiction emphasizes the gap between tracks.

For most of the film, then, we have a split. The image track explores abstract, nonnarrative form. The soundtrack supplies a narrative, actually a Very Grand Narrative. The text, it’s revealed in the credits, comes from Olaf Stapledon’s 1930 science-fiction novel, Last and First Men.

There’s yet a third layer. Jóhannsson, a brilliant composer who died in 2018, gave us memorable concert music and film scores (Sicario, Arrival, The Miners’ Hymns). Along with the voice-over we hear a sometimes radiant, sometimes jarring orchestral accompaniment created by Jóhansson and electronic composer Yair Elazar Glotman. The music doesn’t cooperate much with the voice-over. As the commentary proceeds with a businesslike dryness, the music often flows and eddies on its own course.

The fact that the three channels of picture, voice, and music seldom converge actually sets your imagination free. There’s no need to see the images as illustrating the text, or the music as operatically enhancing either one. We’re allowed to keep the realms separate, or to test obscure correspondences. We can, for instance, see the expressive qualities of the shots as enduring remnants of human will–eccentric, obstinate, and obscure as it can be. The music’s alternation of drone passages, scraps of choral lyricism, and ominous rumbles might seem to chart humans’ up-and-down fate in the late Anthropocene. The narration, recited by Tilda Swinton, adds a quality of stoic dignity to the mix. And you’re invited to try out metaphors, as when cavities in what seems to be an elongated cathedral suggest eyeholes for staring across space.

The disparity of channels is enhanced by another mystery I haven’t seen mentioned in reviews. The images betray their origins on 16mm film. There are light leaks on the frame edges, specks of white suggesting dust on the negative, and even bits of grit and hair in the aperture. Perhaps you can see the hair snagged in the upper right of the image below.

These flaws have not been digitally removed. Indeed, the film’s opening moments linger on black frames flecked with white dust, priming us to watch for faults in these images.

The effect is to add an archaic quality, as if this is all found footage from long before the end recounted on the soundtrack. Since the narrator tells us that humankind goes through many near-extinctions until the big one, these relics may be from one of those future collapses–or, perhaps, from our own past, remnants of a calamity we’ve forgotten. The text speaks of “the debased rites of your religions long ago,” and those big-eyed humanoids are reminiscent of Australian aboriginal art.

In all, it’s a bleakly beautiful experiment. The film premiered with live orchestral accompaniment in the 2017 Manchester International Festival, and it must have been hypnotic. The film and soundtrack are now available on a CD/Blu-ray combination, as well as on vinyl.

Meet the New New Boss, same as the Old New Boss

The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

The scathing 2003 documentary The Corporation took seriously the idea that corporations were persons. Their behavior, considered clinically, is that of a sociopath. Now Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott’s followup shows how the 2008 financial crisis provoked corporations to rehabilitate. Hip CEOs admit the existence of racial bigotry, income inequality and the failures of conservative government. The solution? More corporate power. Did this make them any less dangerous?

Nope. Multinationals shape government policy as vigorously as ever, especially in the era of Trump and other demagogues. But the corporations’ new message is soft power. Posing as socially committed, emphasizing stakeholders as well as shareholders, Big Business is (a) trying to convince consumers that it’s on their side; and (b) arguing that the New Corporation will correct the shortcomings of government policy through privatization. In other words: We’ve learned our lesson. We get it. So let us run things. Besides, what choice do you have?

Bakan and Abbott shrewdly show that this ploy neatly fits an updated clinical symptom of the sociopath: “Use of seduction, charm, glibness, or ingratiation to achieve one’s ends.”

The film begins with a fascinating visit to the Davos Forum, where air-kissing one-percenters solemnly assure us that everybody wins when a corporation acknowledges the public good. The star player is Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase. Having helped crush American cities in the financial crisis (and paying a derisory $13 billion fine), he is now playing rescuer by supporting the rebuilding of Detroit, to the benefit of his company’s image. The film goes on to trace how the public face of caring executives is belied by business as usual, most savagely British Petroleum’s catastrophes in Texas City and at Deep Water Horizon.

Bakan and Abbott marshall a great deal of evidence to show how the plutocracy, and especially those in the digital technology sector, have turned a market economy into a market society. For us, the role of worker-consumer redefines the other dimensions of civic life. You work without union protections and scramble to keep up. You give your personal information to Facebook, Google, and Amazon in exchange for convenience and lower costs. (The old adage holds: If something is free, the product is you.) Schools, postal delivery, war, water, and relationships are all ripe to be rendered as private enterprise. With AI algorithms, the customer-customized milieu of Minority Report is already here.

Talking heads, from Chomsky and Robert Reich to Diane Ravitch and Vandana Shiva, offer pithy critiques, and footage garnered from around the world illuminates each of the points in the Corporate Playbook. As a counterweight, later portions of The New Corporation show some pushback. Katie Porter poleaxes Mr. Dimon in a House hearing, and we glimpse AOC in her usual passionate eloquence. Still, the emphasis falls less on pols and more on citizens who struggle against corporate power.

Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaign are shown to be as important to the left as the Tea Party was to the right. The filmmakers give special attention to the efforts of many tough, idealistic people to run for public office. As one commenter puts it, “Even in the worst situations, people always fight.” In a remarkable passage, a dopy prankster from The Corporation is shown to have become a proud progressive after seeing the first film and joining the Sanders campaign.

The film is startlingly up-to-date, incorporating events around the George Floyd atrocity and the Black Lives Matter street actions. Some will say that the late sections drift a bit from the film’s core message of analyzing the fake social concerns of the New Corporation. But income inequality and environmental destruction, central drivers of new social movements, are invoked in corporate PR as vital concerns for companies’ new image, so the final sequences don’t seem to me tacked on. They show what real social engagement, as opposed to panting coverage in Forbes, looks like.

Where do you start? someone asks in Tout va bien. The answer: Everywhere at once. I think The New Corporation indicates that this might just work.

The three films I’ve discussed are exemplary of the strengths that have characterized the Vancouver festival for its 39 years. Here you can plunge into international auteur cinema, unusual experimental work, and documentaries committed to our noblest aspirations. Programmers Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and their colleagues scour the world for provocative films, and the results have taught Kristin and me lessons about cinema we wouldn’t have learned otherwise. It’s worth noting that VIFF’s welcome to Canadian cinema has always been fruitful: The New Corporation, like its predecessor, is a British Columbia production and is featured in the festival’s ongoing True North series.

Fourteen years ago I wrote that Vancouver was the very model of a regional festival, at once deeply local and unpretentiously cosmopolitan. It still is. Take that, corornavirus! Nothing stops dedicated film lovers.

Thanks to Alan Franey, Jane Harrison, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

A sensitive review of Undine is offered by David Hudson at the Criterion Daily.

A note on Last and First Men: In watching the film, I found myself constantly asking if these structures really existed, or whether they were CGI creations or miniatures or objects purpose-built for the film. Some reviews have revealed their secret identity, and knowing what they are does raise some interesting thematic implications. But I’m refraining from telling you because I think your first encounter with the film ought to include that mystery about what exactly you are seeing. If you want to know what they are, Google is at your service. There’s also this spoiler-filled behind-the-scenes video.

Jennifer Abbott has another documentary in this year’s festival: The Magnitude of All Things. I look forward to it.

Undine (2020).

The poet of dynamic immobility: Ennio Morricone: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Ennio Morricone holding his principal instrument, the trumpet, in a picture taken in the 1970s. Photo by Roberto Masotti.

DB here: For our blog entry #1001, who better to memorialize Morricone than our stalwart collaborator Jeff Smith? He has provided many music-sensitive analyses of films both recent and classic. Our most popular entries from last year were his two looks (here and here) at the music and musical culture behind Once Upon a Time. . . . in Hollywood. Herewith his warm appreciation of a maestro.

Jeff here:

On July 6, 2020, the legendary composer Ennio Morricone passed away in Rome at the age of 91. As expected, several encomia were published reflecting upon Morricone’s musical genius. Of particular note were reflections by two writers for Variety, film critic Owen Gleiberman and film music historian Jon Burlingame.

The tributes highlighted many notable features of Morricone’s film work: his gift for melody, his sense of humor, his eclecticism, and his amazing productivity. Having written more than 500 film and television scores, Morricone’s compositional output was jaw-dropping. After all, even Josef Haydn wrote only 106 symphonies.

Throughout my own career as a film scholar, I frequently engaged with Morricone’s music. In preparation for the writing of my dissertation, I did an independent study with David on Hollywood film music. My final project? A detailed analysis of the score for Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, complete with handwritten transcriptions of every musical theme and motif I could identify.

I vividly remember the satisfaction I felt in being able to play the main title from start to finish on the piano. It is one thing to read music and play it. It is another to take what you hear and try to put it in some reproducible form on paper. Playing back Morricone’s famous theme, I felt I’d gained insight into the mind of the great composer. That work eventually became the basis for chapter six in my first book, The Sounds of Commerce.

My fascination with Morricone’s work has continued to the present day. Last summer, I wrote a review of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, a book of interviews conducted by Alessandro De Rosa. This past April the Criterion Channel posted my most recent “Observations on Film Art,” which examines musical motifs in Morricone’s score for The Battle of Algiers.

That’s close to thirty years of near-obsessive fascination with Morricone’s music and his compositional style. In what follows, I share some additional thoughts on the Maestro’s legacy, offering some insight on the reasons for his seemingly inexhaustible creativity.

The Sicilian defense

The first section of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words is all about the maestro’s love of chess. Although the composer would describe himself as a hobbyist, his chess skills surpassed those of most amateurs. Morricone played against Boris Spassky, Garry Kasparov, and other Grand Masters. When asked about his passion for the game, Morricone explains that he sees important parallels between music composition and chess. Both activities involve mathematical relations. These relations are further expressed in axes of verticality, horizontality, and graphics.

This initial discussion of chess struck me as a key to understanding Morricone’s creative process. The game of chess is often analogized as a battle where stratagems and tactics are deployed in an effort to outmaneuver – and thus, defeat – one’s opponent. That comparison undoubtedly rings true. Yet when one looks at the board before the game starts, it also represents something simpler: a field of open possibilities. Not every move is permissible, of course. But when you consider possible combinations of moves, the permutations can number in the millions. And even though the rules of chess constrain the patterns of moves that can be made, all of these possibilities are generated by the dispositions of up to 32 pieces on a field of 64 squares.

Morricone seems to approach the blank space of staff paper as though it were a chessboard at the start of the game. A chess player works with sixteen pieces that can be used in various combinations. A composer works with the twelve tones of the chromatic scale to create intervals and chords. As with the chessboard, there are millions of different permutations in the way these twelve tones can be arranged. More importantly, since each note in the scale can be varied by pitch class, duration, articulation, dynamics, and instrumental color, the options seem endless.

Yet while the “terror of the white page” can be an obstacle to the creative process, that has never appeared to be the case with Morricone. Why? I think it is because the composer found a method of composition that reduced the apparently infinite possibilities to the level of the merely multitudinous.

In Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, the composer characterized himself as a student of the Second School of Vienna. Unlike Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern, who were part of the first Viennese School, Morricone tried to transpose the former’s twelve-tone technique into a seven-tone system while retaining the latter’s commitment to the rules of serialism that ordered all other musical parameters. For Morricone, this system had the advantage of enabling him to write tonal music without having to slavishly adhere to its characteristic tensions and resolutions. By adopting Webern’s principles of serialism, the notes, according to Morricone, “are freed from their reciprocal constraints.”

Over time, Morricone learned how to adapt this simplified version of twelve-tone serialism to the needs of each film score he wrote. In some cases, he would work within a pentatonic system. In others, he might base his compositions on a row of six or eight tones. In still others, he might jettison the system altogether.

This simplified serial technique provided Morricone with a compositional framework that was extraordinarily generative. Once the composer has determined the tone row and the ordering of other musical parameters, he simply spins off hundreds of variations that are then fitted to the film’s dramatic situations. The smaller tone row still acts as a guarantor of harmonic unity. Morricone describes it as the music’s DNA, something like an identifying marker in every musical “cell.” Specific changes in rhythm, tempo, orchestration, volume, and tessitura all provide means of refreshing the basic musical schema.

Indeed, Morricone’s compositional system proved so procreant that he sometimes wrote three or four versions of a score’s theme in order to give the director some options to choose from. In Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, he offers an example with the police triumph theme in The Untouchables. The theme was the last one written for the score, and Morricone prepared three pieces that were recorded with two pianists. He then sent them off for director Brian De Palma’s consideration. De Palma didn’t like any of them. Back to the drawing board,

Morricone wrote three more pieces and shared them with De Palma. In a phone call, the director told Morricone that he still wasn’t convinced. Morricone completed three additional pieces and sent them. This time, though, he included a brief that summarized the strengths and weaknesses of all nine proposals. Morricone himself recommended against variant number six, claiming it was most triumphant and therefore the least convincing. Concluding his story, Morricone asks, “Guess which one he chose?”

After I sniggered at the composer’s dig at De Palma’s musical sensibilities, the larger implications of Morricone’s anecdote began to sink in. My mind was well and truly blown. If Morricone had written eight other themes in lieu of the one that was ultimately chosen, how much music had he actually written for The Untouchables? And if this, as Morricone indicates, was not an isolated case, how many unused cues are likely sitting in boxes somewhere in Rome simply waiting to be discovered? As noted earlier, Morricone had written music for more than five hundred films and television shows. Were the aggregated number of unused cues and alternate versions of themes the equivalent of another one or two hundred scores? And if we trust Morricone’s judgment, some of these versions are actually better than the ones we already know.

All of this is a reminder that Morricone’s output is astonishing. This is evident both in terms of the size of his corpus and the sustained quality of his work over a period of almost sixty years.

Much of that productivity, I think, was fueled by Morricone’s transposition of serialist concepts to the film score. Like the rules of chess, which prohibit certain moves, Morricone’s use of simplified tone rows gave him a set of “rules” that fruitfully limited certain options in terms of melody and harmony, but still preserved the usual range of choices for other musical parameters. It also shaped our sense of Morricone’s style by favoring certain compositional devices over others. Pedal points and ostinati are completely permissible in Morricone’s system. But a rapid chromatic run of the type used in classical Hollywood “hurries” would be out of bounds.

Such a rapid chromatic run is also ill-suited to Morricone’s aesthetic for another reason; it is a musical gesture that implies directional movement. Instead Morricone strives to produce a sensation of “dynamic immobility” in his work, the musical equivalent of the swirls, eddies, and ripples we associate with lake water. The sense of immobility derives from Morricone’s interest in writing tonal music outside of the strict rules governing the Western tonal system. One hears chord changes. But you couldn’t describe any particular change as a modulation insofar as there is no definite key to ground these harmonic relations. Consequently, you discern harmonic change, but without the sense of teleological movement toward a cadence as a definite endpoint.

If Morricone’s approach to harmony strives for a feeling of moving stasis, what then accounts for the music’s dynamism? For Morricone, it is the constant change evident in the other musical parameters: texture, pitch, dynamics, and timbre.

Listen again to the cue from The Untouchables. Do you notice the sorts of surges and swells produced by its chord changes? Does it sound like it moves to a definite endpoint? Or does one instead get the feeling of an endlessly deferred resolution? If those surges and swells produce the latter, that’s Morricone’s “dynamic immobility” in situ.

Morricone’s creative spark seems all the more remarkable when one considers that he worked in a production environment guided by the notion that “I don’t need it good; I need it Tuesday.” That Morricone flourished within this milieu for more than five decades eventually made him “untouchable.”

Roll over Beethoven and tell Tchaikovsky the news

A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

In The Sounds of Commerce, I argued that the 1960s proved to be an important period in the history of the Hollywood film score as the dominance of its neoromantic style began to wane. Driven partly by the popularity of theme songs and soundtrack albums, composers infused the classical Hollywood score with elements of both jazz and pop music. To be sure, those styles all had their place in Hollywood films. Characters performed Tin Pan Alley songs in musicals. Dance bands played jazz as part of the nightlife featured in gangster films and films noirs. And one even heard the occasional bit of Gershwin-style orchestral jazz pop up in a score. The changes I discerned in sixties film scores were more a matter of degree than of kind.

What prompted the change? Besides the emergence of new ancillary markets for film music, Hollywood also saw a generational shift take place throughout the industry, including film composers. Sadly, some of the greatest proponents of the classical Hollywood style, such as Herbert Stothart, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Victor Young, were dead before 1960. Others, like Roy Webb, Max Steiner, and Miklós Rózsa, remained active, but they saw fewer assignments come their way.

Taking their place was a new breed more attuned to changes in the jazz and pop idioms. Instead of aping Gershwin, these new composers were more likely to draw upon swing music or West Coast jazz. Similarly, several film composers also began to incorporate elements of pop music’s newest sensation: rock and roll. In an interview I did with Henry Mancini, he described his famous “Peter Gunn” theme as a rock tune due to its “straight eight” rhythms and its twangy guitar line. Not coincidentally, John Barry’s arrangement of the James Bond theme foregrounded Vic Flick’s guitar in a similar way. The middle section of the tune features a swinging, Dizzy Gillespie-ish break. But that guitar sound stood out, much closer to Carl Perkins than to Wes Montgomery.

During the 1960s, no film composer was as thoroughly steeped in the rock idiom as Ennio Morricone. Yet, unlike Mancini and Barry, who were drawn toward rockabilly in their use of electric guitar, Morricone cribbed from the slightly more modern sounds of early sixties surf-rock. Morricone tells Alessandro De Rosa that he used the electric guitar long before he wrote the scores of his spaghetti Westerns, albeit not as a solo instrument. Yet he opted to feature the electric guitar in the main theme of A Fistful of Dollars because he liked “its tough and sharp timbre,” which he felt was perfect for the atmosphere of the film.

De Rosa also notes that the Shadows’ surf music was extremely popular on Italian record charts in the early sixties, especially their Western-themed classic “Apache.” The distinctive twang of Hank Marvin’s Fender Stratocaster was widely imitated by Italian beat bands. By the time A Fistful of Dollars was in production, the Shadows’ influence had seeped into Italian popular music culture. When they topped the Italian charts in 1963 with “Geronimo,” another paean to the American west, it probably seemed quite natural to make the Stratocaster’s sound the centerpiece of Leone’s groundbreaking film.

Morricone made the electric guitar the star of many more spaghetti Western scores. But none so prominently as the “Man With the Harmonica” theme of Once Upon a Time in the West. Famously, the film features no main title in the opening credits, “scoring” the scene instead with the sounds of the wind, a creaking mill, the clanging of a metal gate, and an especially persistent horsefly (among other things). Morricone’s score doesn’t come into Leone’s film until about the twenty-minute mark. But when it does it makes quite an entrance.

Frank and his gang have just slaughtered the McBain family. The only survivor is a red-headed boy who comes running out of the house after hearing gunshots. As he comes into a close-up, Bruno Battisti D’Amario’s guitar starts blasting through the theater speakers. The sound is loud and distorted, cutting through the silence like an axe through a chicken’s neck.

In his instructions to D’Amario, Morricone insisted that the theme was meant to “wound the audience’s ears like a blade” the first time we hear it. As a coup de théâtre, it is brutally effective. I’ve seen it more than twenty times, and the moment never fails to give me chills. Here we see Morricone experimenting with the timbre of the guitar by heightening the effects of high volume and high voltage to overdrive the power valves of the amplifier. The effect was such that some critics even described Morricone’s score for Once Upon a Time in the West as a sort of “post-Hendrix” rock. The comparison was undoubtedly flattering. No musician had done more to explore the timbral possibilities of the electric guitar than Jimi Hendrix.

Morricone experimented in other ways that seemed to merge elements of avant-garde classical music with more vernacular forms. Consider his “Harmonica” motif in Once Upon a Time in the West alongside Henry Mancini’s main title for Wait Until Dark, which was released about a year before Leone’s epic. Both film scores explore microtonal effects, albeit in quite different ways.

In Mancini’s case, he asked the studio to give him two pianos that were tuned a quarter tone apart. He then asked his two performers to play the chords of an accompaniment figure in rapid succession.

The dissonance produced through this effect is unlike any produced in atonal writing. There the composer deliberately emphasizes intervals that create a sense of disharmony, such as minor seconds, major sevenths, and tritones. Yet Mancini’s microtonal experiment does something else entirely. Our ears tell us we should be hearing the same chord, but the repetition on the detuned pianos sounds a bit off. Mancini’s score evokes a kind of dislocation well suited to Wait Until Dark’s generic trappings as a psychological thriller. The effects, though, were even more pronounced for the two pianists who played on the main title. Pearl Kaufman and Jimmy Rowles both reported having to take frequent breaks during the recording sessions. The sort of “swimming” effect produced by the detuned pianos gave them a feeling of vertigo and nausea commonly found in motion sickness.

Morricone’s approach to microtonal harmonies proves to be much more elemental: the wavering sounds of two notes played on the harmonica, ostensibly a half step apart. Anyone who has played a harmonica knows it requires great breath control. Inhale and you make one pitch. Exhale and you make another. Beyond that, skilled performers can also bend pitch on a harmonica by changing their embouchure. Harmonica players can also use their hands as dampers, altering the sound in much the same way a wah-wah mute alters the tone of a trumpet.

All of these techniques give the harmonica player a number of means to bend pitch. Morricone takes full advantage of them with the “Harmonica” motif in Once Upon a Time in the West.

Listening to this passage, one can hear how Franco De Gemini’s mouth harp straddles the fence between sounding bluesy and sounding strident. Morricone viewed the half-step relation in the motif as a key element in building musical tension since it is heard in the flashback that explains Harmonica’s life-long quest for revenge. Yet De Gemini’s subtly wavering pitch seems to capture the full range of microinterval variants that fall between the D# and E that comprise the last two notes of the motif.

Both composers’ explorations of microtonal effects prove effective. But the precision of the quarter tone difference in Mancini’s detuned pianos gives the music a mechanistic quality that seems cold and brittle. By contrast, the harmonica’s fluid pitch-bending in Once Upon a Time in the West is looser, freer, more improvisatory – all of which fits the types of vernacular music played on harmonica.

This effect was enhanced by Morricone’s recording techniques. He first recorded the orchestra and then recorded De Gemini’s harmonic track individually. Although the latter recording was less precise, Morricone said that “the tension generated by the performance made his harmonica float over the orchestra. Now on the beat, then behind it, this time ahead….in short, it was almost as though it was fluctuating.”

Morricone’s compositional and recording techniques in Once Upon a Time in the West might seem less daring than Mancini’s more avant-garde experiment in Wait Until Dark. Yet Morricone’s music gains something in its more organic placement within Leone’s film. The harmonica’s wavering pitch is akin to the sorts of portamenti and string-bending frequently heard from saxophones, guitars, and basses in a multitude of rock and roll songs produced throughout the idiom’s history. And the harmonica as an object has long been a common feature of the Western’s iconography. In this way, Morricone’s experimentation is grounded in the dramatic, stylistic, and symbolic structures of Leone’s epic.

A horse of a different tone color

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

Unquestionably, Morricone’s most audible innovations came through his approach to orchestration. As nearly every obituary noted, his unusual combinations of instruments became a hallmark of the Morricone sound. In a summary of the signature elements found in the score for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, The Economist declared:

And then there is the freewheeling range of sounds with which he chose to make that music: the whistling, the yodeling, the gunfire and the squeaky ocarina, an ancient Italian wind instrument that looks like a sweet potato and is better known to a younger generation as the soundtrack of a Nintendo video game.

As I suggested above, Morricone was part of a cohort that moved outside the neo-Romantic style of film composition associated with the studio era. Unconventional orchestrations were an important part of that push.

Several factors provided impetus for this change. One was the embrace of jazz and pop styles. Incorporating those elements often meant writing for the instruments typically associated with those idioms. Mancini, John Barry, Frank De Vol, and Nelson Riddle all were prominent exponents of this approach during the 1960s. Indeed, many of Mancini’s orchestrations simply add strings to the usual forces of a jazz big band.

A second factor was the breakdown of the studio system in the 1950s. The majors’ retrenchment saw them making fewer films and reducing their overhead costs. They sold off parts of their backlots and leased their soundstages to independent producers or television crews. They also tried to shed labor costs, including those associated with maintaining an in-house orchestra.

This was bad news for musicians, who suddenly found themselves working in a gig economy as independent contractors. But it was good news for composers who now could write music for something other than a standard chamber orchestra. (During the Golden Age, studio bosses would sometimes chafe at the notion of hiring extra musicians, since they were already keeping as many as fifty regularly on call.)

With more flexible options when it came to musical labor, composers began to experiment with more unusual combinations. Whereas the typical studio orchestra employed one or two keyboardists, Bernard Herrmann arranged one cue in Journey to the Center of the Earth for nine organs. Three organists played electronic organs and one played a cathedral organ.

In many ways, Herrmann’s experiments with orchestration provide an interesting foil for Morricone’s own flights of fancy. For two of the scores Herrmann wrote for Alfred Hitchcock, he self-consciously limited his palette to the sounds of a single section of the orchestra. On Psycho, Herrmann wrote only for strings, claiming that the more monochrome sound was fitting for a black and white film. Yet, within that uniformity, Herrmann wrought an extraordinary range of subtle differences in timbre through the use of pizzicato, mutes, and unusual bowing techniques. The famous bird shrieks produced by the violins during the shower murder recall the avant-primitivism of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. But Herrmann achieved this effect only with strings rather than a full orchestra.

Herrmann did something similar in his unused score for Torn Curtain, which was written for sixteen French horns, nine trombones, two tubas, twelve flutes, two sets of timpani, eight cellos, and eight basses. For Torn Curtain, Herrmann’s restriction of his palette was inspired by the setting rather than the cinematography. By emphasizing the low brass and lower-pitched strings, the composer sought to find a sonic equivalent to the drab cheerlessness of life behind the Iron Curtain. Alas, Hitchcock rejected the score under pressure from Universal to produce a saleable music tie-in. The studio wanted something like the Beatles. What they got from Herrmann was more like John Philip Sousa on an acid trip.

If Herrmann’s orchestrations were the musical equivalent of a Mark Rothko painting, exploring a range of subtle shadings within a single color, Morricone’s were closer to the collage principles of Robert Rauschenberg. Just as Rauschenberg’s work juxtaposed unconventional materials and objects within a single canvas, Morricone enjoyed the wild, discordant collisions that could come by combining oddball instruments with one another. The composer is often described as a postmodernist because of his “everything but the kitchen sink” approach to orchestration. No doubt this is one of the reasons his work was so appealing to “downtown” musical avant-gardists like John Zorn.

Consider, for example, the way Morricone uses vocal textures throughout his score for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. It features Edda Dell’Orso’s gorgeous soprano, natch. But it also features a variety of other vocal sounds, some of which border on the “unmusical.” These include the famous “coyote incipit” that has become something of a meme for the spaghetti Western more generally.

There are also plenty of other chants, grunts, and yelps that add their flavors to the musical stew. Morricone even had his singers vocalize through various trumpet mutes to produce the “wah-wah-wah” that is a motivic counterpart to the coyote incipit.

Morricone also made marvelous use of library effects to incorporate the sonic iconography of the Western into his score. We hear gunfire, whipcracks, and ricocheting bullets as elements of rhythmic punctuation throughout the music of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. (Since cowboy yells and whipcracks both appear in the opening theme of Rawhide, perhaps both of these tactics are a sly reference to star Clint Eastwood’s television career.) Even these audacious touches are supplemented by simple, but effective solutions to musical problems. In need of a rhythmic pulse underneath the melody, Morricone coaxed Bruno D’Amario to tap the pickup on his electric guitar.

All of this suggests something very Cagean in Morricone’s approach to orchestration. It is though he took the idea of Cage’s “prepared piano” in which different objects could be laid on the strings of piano’s soundboard, and applied it to the full orchestra.

What is the sound of one wing flapping?

The Mission (1986).

Although Morricone’s spaghetti Western scores displayed his boldest experiments in orchestration, his interest in unusual sonorities continued throughout his career. Some choices are a bit more conventional than others. But they always strike me as inherently right. The oboe seems like a fairly idiosyncratic instrument for an 18th-century Jesuit missionary. Surprisingly, though, its melancholic yet dulcet melismas are a perfect complement to the big sound of The Mission’s double chorus, the latter itself inspired by the luminous sacred music of Palestrina.

Or think of Morricone’s use of the panpipe. He seems attracted to its airy timbre, using it in several scores throughout his career. Yet, comparing its appearance in both Once Upon a Time in America and Casualties of War shows that the panpipe’s sound resists any easy associations. In Leone’s gangster epic, the panpipe is introduced in “Cockeye’s Theme” in a scene where Noodles buys a one-way ticket to Buffalo. After completing his purchase, his attention is drawn to a large poster encouraging tourists to visit Coney Island. The music suggests Noodles’ memories of childhood and his grief after hearing the news that his three childhood friends all died in a battle with federal agents.

It comes back, though, at the moment when Dominic is killed by Bugsy, a rival gang member. As Morricone noted, Leone identified this scene “as a definite point of no return in the story, the watershed marking the end of youth.”

In contrast, for De Palma’s combat film, Morricone used two panpipes in the theme he wrote for the young Vietnamese woman who is abducted, raped, and killed by US soldiers. Here the motivation was something that struck Morricone in the staging of her death.

She buckles her legs like a dying bird, before tumbling down from the high ground. I imagined a theme based on just a few notes for two panpipes, which by ping-ponging their sound, evoke the slowing fluttering of a bird’s wings shortly before death.

At first blush, Morricone’s description of the scene sounds like “Mickey-Mousing” where the music accents a character’s actions, movements, or gestures. But what Morricone actually gives us turns out to be much more sophisticated. A classical Hollywood composer like Max Steiner might have caught the girl’s collapse through a downward glissando or a rapid, descending scale run. Instead Morricone gives us a different musical gesture – the alternation of two notes on the panpipe – to suggest an action not visible onscreen: a dying bird’s fluttering wings.

As is evident in the clip, we hear the two panpipes play over the image of the young woman’s broken body. Yet Morricone associatively links it to the birdlike movement seen about a minute earlier: the buckling of her knees as she falls.

A moment such as this one nicely captures Morricone’s gift for storytelling. Many of Morricone’s fans treat his scores as absolute music, often listening to them repeatedly without ever watching the films they accompany. But Morricone also had a gift for translating a film’s larger themes and meanings into musical forms.

Morricone achieved fame for his beautiful melodies, rich harmonies, and surprising orchestrations. None of that would be very meaningful, though, if these elements weren’t firmly rooted in the composer’s extraordinary dramatic sense.

The greatest?

The Hateful Eight (2015).

At the end of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, Alessandro De Rosa asks the composer if there was a specific moment when he realized he’d become one of the greatest, most influential composers of the century. Morricone gets flustered by the question, claiming such judgments are premature. In music, it takes hundreds of years to determine whether one’s work endures. He then adds a polite, but banal conclusion, saying it is wonderful to be appreciated and even better to have one’s music reach so many people.

Still disarmed by the question, Morricone continues hesitatingly:

The greatest of the century? It is difficult to reply….Oh dear…. where did you hear this?

De Rosa responds, “It was just to provoke your vanity…” Acknowledging the trap set before him, Morricone smiles and replies, “You don’t say….I figured!”

Morricone’s humility might be a tacit recognition that he’s had the great fortune to write music for the movies–one of the greatest engines for pleasure that the world has ever seen. A great film surely benefits from a great score. Yet it can seem that the composer is just along for the ride.

Still, Morricone understood that his music was often better than the films it accompanied. As he well knew, fortune gives with one hand and takes with the other. Morricone wrote music for masterpieces like Days of Heaven. He also worked on schlockfests like The Exorcist II: The Heretic.

Perhaps more than other craft positions, the lot of a film composer can seem unique. Music exists as its own formal system. But film scores are always written in the service of something else and judged accordingly. Directors often hope in vain that a composer can salvage a bad scene. Yet composers themselves will say they’re not miracle workers. And even when the score can stand on its own, some pugnacious critic will ask, “Should it?”

When I was doing the initial research for my dissertation during the early nineties, I recall some film music critics dividing the field into craft workers and stylists. The paradigm case for the former was a composer like Jerry Goldsmith, who subordinated his personality to the dramatic requirements of the work. Goldsmith could write a bittersweet jazz melody for Chinatown, a stirring horn call for the war epic Patton, cartoonish “Mickey-mousing” for the comic fantasy Gremlins, and outré dodecaphonic themes for sci-fi adventures like Planet of the Apes and Alien. Binge-watch all five films and it would seem hard to believe the music was all the work of a single person.

Stylists, on the other hand, were composers who had created such a distinctive sound that their music could not be mistaken for that of another. All three of the composers featured in my book seemed to fit that rubric – Henry Mancini, John Barry, and Ennio Morricone – a factor that likely contributed to the popularity of their scores in ancillary markets.

Looking back almost thirty years later, the label of stylist fits the work of Mancini and Barry quite well. In fact, I have anecdotal proof of the latter in my first viewing of Michael Apted’s espionage thriller Enigma. Halfway through film, I wondered to myself who had written the score since it sounded a lot like John Barry. Checking the poster afterward, my hunch was confirmed; it was John Barry!

For Morricone, though, the “stylist” label seems misapplied. At the time, this was due to the fact that he was so strongly associated with the spaghetti Western. He had written music for more than thirty films in the cycle and had come to define it in the public imagination. It is telling that the scores written for other spaghetti Westerns by Luis Bacalov or Riz Ortolani sound like Morricone facsimiles.

Identifying Morricone so closely with the spaghetti Western, though, ignores the inspired music he wrote for so many other genres: horror films, gangster films, thrillers, historical epics, political satires, and even the occasional romantic drama.

Take five Morricone classics not so randomly selected: Teorema, Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, Cinema Paradiso, Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, and The Hateful Eight. Could any other composer have written the notes that we hear? Probably not. They all seem to bear the distinctive Morricone signature. Yet they are also so unlike one another that it seems unfair to suggest that he didn’t mold his sound to the specific needs of each film. For Morricone, we have to throw out the “either/or” implied by the rubric. He’s both a craft worker and a stylist.

If that seems like a copout on my part, it’s one I will happily embrace. For me, like many others evaluating Morricone’s legacy after his death, his music is both cerebral and visceral. It warms the heart and tickles the brain, sometimes simultaneously. And that seems rare for much 20th-century concert music, which even at its best, can feel quite cold and analytical.

Thirty years later, Morricone’s music still enthralls me in a way that’s unlike that of any other film composer, especially when the score is heard coming from the big screen. I’ve had the great pleasure of screening a 35mm print of The Untouchables the past two years. Hearing Morricone’s main title played back in Dolby Stereo with a proper subwoofer, I still get goosebumps. I even anticipate the massive bass drum hit that punctuates the rhythms played by brushes on the snare. If the stinging guitar chord that introduces Frank was intended to sound like a stab, that bass drum sound is the musical equivalent of a gut-punch.

Ciao, Maestro! You will be missed. Yet your music will live on, perhaps even for centuries. For my part, you’ve given me hundreds of joyful moments at the cinema and a lifetime of wonderful memories.

Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words can be found here. If you want to learn more about his music, this is a great place to start. It includes reproductions of Morricone’s handwritten musical notation. It also includes a thorough survey of both Morricone’s film scores and his concert works.

My review of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words is here. A brief discussion of Morricone’s score for The Hateful Eight can be found in my 2016 Oscar preview. Incidentally, Tarantino used Bernard Herrmann’s rejected score for Torn Curtain for the excerpt from Rick Dalton’s action film The 14 Fists of McCluskey in Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood. The cue can be found here and the scene from Tarantino’s film is here.

My chapter on Morricone’s spaghetti Western scores can be found in The Sounds of Commerce.

Henry Mancini discusses his score for Wait Until Dark in his autobiography, Did They Mention the Music? Bernard Herrmann’s score for Psycho has been analyzed by several film music scholars. Among the best is Fred Steiner’s “Bernard Herrmann’s ‘Black-and-White’ Music for Hitchcock’s Psycho,” anthologized in Elmer Bernstein’s Film Music Notebook: A Complete Collection of the Quarterly Journal, 1974-1978. Details of Herrmann’s orchestrations for his rejected score for Torn Curtain can be found in the liner notes of conductor Joel McNeely’s recording. They’ve been posted here.

The chess portrait above is by Riccardo Musacchio.

Morricone waits backstage at a 2010 concert of his work at the Royal Albert Hall in London. Photo by Roberto Musacchio.

Twice upon a time . . . in Hollywood: Jeff Smith revisits Tarantino’s retro opus

The Wrecking Crew (1969).

Jeff Smith’s blog entry on Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood has been our most popular offering this year. In the wake of that, he offers a few more observations. (DB)

The film’s commercial success confirms the value of original intellectual property, up to a point. Four weeks after its release, Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood’s current box office total is just over a $120 million for the domestic market. It’s also earned about $117 million in foreign markets. It seems likely to be the only film this summer to surpass $200 million globally that is neither a remake, a sequel, nor a franchise film.

Still, I agree with the general sentiment that there are no blue-sky lessons to be learned here. Tarantino is one of those rare talents who offers viewers a unique personal vision that has appeal beyond the arthouse. (Others would include Alfonso Cuarón, Damien Chazelle, and, of course, Christopher Nolan.) Current projections put Once Upon a Time . . .’s cumulative box office total around $385 million. That figure would fall short of Django Unchained’s $425 million, but would be considerably better than Inglourious Basterds’ $321 million. Not quite Inception or Gravity money, but not chump change either.

Tarantino’s film also gives Sony Pictures something to promote this Oscar season, along with Tom Hanks as Fred Rogers in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood and Greta Gerwig’s take on Little Women. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood seems likely to snag several nominations in major categories. I would be very surprised if it didn’t score nods for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actress, and Best Cinematography.

I also have a few stray observations that didn’t make it into my earlier post. One is another element of counterfactual history.

One evening Cliff and Rick watch “All the Streets Are Silent,” the episode of The F.B.I. that Tarantino has recreated. They want to see the Rick’s guest spot as Michael Murtaugh, alongside James Farentino and Norman Fell. But who actually played Murtaugh in that episode? None other than the late, great Burt Reynolds, whom Tarantino had originally cast in the role of George Spahn.

Reynolds is among a trio of sixties stars who served as role models for Rick Dalton. Steve McQueen is perhaps the most notable, both as a character who appears in the scene at the Playboy Mansion and as the star of The Great Escape, a part Rick had hoped to get. McQueen also came to movies from the small screen. From 1958 to 1961, he was the star of Wanted: Dead or Alive, a show that was an inspiration for Bounty Law.

The second model for Rick is, of course, Clint Eastwood. Eastwood made his mark as the star of TV’s Rawhide before achieving international fame in spaghetti westerns playing Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name. This trajectory is echoed in Rick’s late-career arc, although his westerns don’t achieve the renown of Eastwood’s.

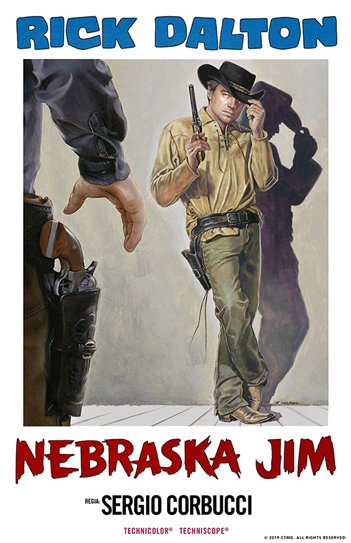

Burt Reynolds’ path to stardom was somewhat different from McQueen’s and Eastwood’s. Reynolds played only a supporting role on CBS’s Gunsmoke from 1962 to 1965 before he went to Italy to star in Sergio Corbucci’s Navajo Joe. Again, Rick follows this pattern, as we see when he moves from supporting TV parts to starring in the fictional Corbucci title Tarantino devised, Nebraska Jim.

What most differentiates Reynolds from the other two stars, however, was his close relationship with stuntman Hal Needham. Needham did stunt work in more than 300 films and 4500 television episodes, often acting as Reynolds’ stunt double. He also did uncredited stunt work on a handful of films and shows referenced in Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood, such as Mannix, C.C. & Company, and The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean. Needham would later direct Reynolds in several box office smashes, like Smokey and the Bandit and The Cannonball Run. In Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood, Rick’s rapport with Cliff was inspired by Reynolds’ and Needham’s long friendship, a professional association which spanned almost forty years.

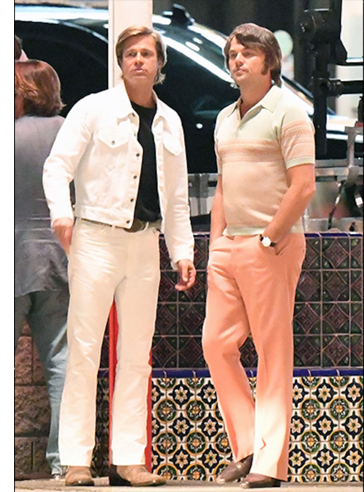

Lastly, a sharp-eyed reader of the blog, Karl Wallin, also pointed out another connection between Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood and The Wrecking Crew. (Karl is an old chum and the only person I know even more obsessed with Tarantino’s film than I am.) Karl noted that the white denim suit that Cliff wears in the blood-soaked climax matches the white suit Matt Helm wears during the last twenty minutes of The Wrecking Crew. (See top still.)

Lastly, a sharp-eyed reader of the blog, Karl Wallin, also pointed out another connection between Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood and The Wrecking Crew. (Karl is an old chum and the only person I know even more obsessed with Tarantino’s film than I am.) Karl noted that the white denim suit that Cliff wears in the blood-soaked climax matches the white suit Matt Helm wears during the last twenty minutes of The Wrecking Crew. (See top still.)

Karl pointed out another serendipitous connection between different aspects of the Manson case. As I mentioned in the earlier post, Manson met a couple of times with record producer Terry Melcher about the prospect of signing a contract. Melcher ultimately soured on the deal, which led Manson to target the producer’s former residence as the site of the first murders. On some of the albums Melcher produced, he worked with a loose collection of extremely talented session musicians that were the Los Angeles equivalent of Motown’s The Funk Brothers. The group included several notable instrumentalists, such as guitarists Glen Campbell and Tommy Tedesco, pianists Leon Russell and Dr. John, bassist Carol Kaye, and drummer Hal Blaine. The name of this loose collective? The Wrecking Crew!