Archive for April 2012

Carry me back to the old Virginia

Chaz Ebert and Roger Ebert on the stage of the Virginia Theatre, Ebertfest 2012. Photo by DB.

DB here:

The fourteenth Ebertfest, held in the sumptuous Virginia Theatre in Urbana, had its customary mix of independent films old and new, Hollywood classics (sometimes cult classics), an Alloy Orchestra performance, and some unclassifiable items. It was, as ever, a crowd-pleasing jamboree. It reflected Roger’s eclectic tastes and was brought to us by Chaz Ebert, festival director Nate Kohn, and woman-who-knows-and-does-all-things Mary Susan Britt.

You can see the intros, the panels, and the Q & As—that is, nearly everything, except the movies and the offside fun–on the Festival channel here.

The young and the restless

Kinyarwanda.

First features are a hallmark of Ebertfest, and many have stayed in my memory, among them The Stone Reader (2003), Tarnation (2004), Man Push Cart (2006), The Band’s Visit (2008), and Frozen River (2009). This year there were several feature debuts.

Patang (The Kite) concentrates on a single day in the life of a family celebrating the annual festival of kite-flying in Ahmedabad, India. An uncle has returned to town with his daughter, and usual in such movie reunions, old tensions are reignited. A side-story concerns Bobby, a street-wise local, and a little boy who delivers kites. Needless to say, this story intersects with and sheds light on the primary family conflict.

Prashant Barghava is a pictorialist with an eye for startling color and compositions. Shot in nervous handheld images, with many planes of action jammed together and the camera eye seeking something to focus on, Patang reminded me of The Hurt Locker, but without that film’s sense of ominous vigilance. The tone of this one is more exuberant, and the cast of nonactors gives it vibrancy.

Kinyarwanda, by Alrick Brown and an energetic team of collaborators, explores the Rwandan genocide of 1994 in an unusual way. It displays the role of the Muslim community in protecting the Hutu population (many Christian, some not) from the depredations of the Tutsi death squads. To emphasize the breadth of experience, the film adopts a chaptered network-narrative structure. A Catholic priest, a young woman, an angry Tutsi, a sympathetic imam, a little boy, and a leader of the Rwanda Patriotic Front gradually converge, first in a mosque compound, and ten years later in a reeducation and reconciliation camp. The film also plays with time, replaying some key events—notably the Tutsi’s advance on Jeanne’s home—but also anticipating some outcomes. Interestingly, by showing many of the Tutsi killers in 2004 repenting their crimes before we see those attacks, the film builds a degree of compassion into its overall form.

Scenes with adults are dominated by either personal problems (the Hutu/ Tutsi clash infiltrates a marriage) or discussions of religious doctrine. There are as well wordless moments in which we follow children—a little girl whose Qu’ran has been defaced, a boy who encounters a death squad while sent to fetch cigarettes. If the adults supply the film’s prose, the kids are its poetry.

Patang played both Berlin and Tribeca and will be opening in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco soon. Kinyarwanda won awards at several festivals, including Sundance and AFI Fest, and is coming to several other festivals. It arrives on DVD 1 May.

The misfit section

Terri.

Two other young directors got good exposure. Robert Siegel wrote the screenplay for The Wrestler after working on The Onion (Madison cheer obligatory here). His debut feature, Big Fan, is the story of a football fan who is mangled by his idol and has to struggle against his family’s pressure to sue. Patton Oswalt, who had to cancel his Ebertfest visit at the last minute, played Paul with a potato-like obstinacy that offset the shrieking caricatures around him. On the down side, I could have done with a couple of hundred fewer close-ups. (Watching a movie at the Virginia reminds you of the power of the two-shot.) Still, Siegel wisely doesn’t give his hero a girlfriend who would lead him to the Big Normal and wean him away from his obsession. As Siegel points out, “He’s completely happy, but everyone around him thinks he’s unhappy.” Big Fan is an enjoyable portrait of the sports nerd.

More laid-back was Azazel Jacobs’ second feature Terri. It’s sort of a coming-of-age movie, but it has a peculiar humor that such wistful exercises usually lack. Terri, an enormous teenager, goes to high school in pajamas and is teased mercilessly, but he reacts with a dead-eyed passivity that suggests both resignation and resilience. Like the hero of Gulliver’s Travels, the book Terri is working his way through, he’s tied down by Lilliputians around him, but he gets by.

It’s a film of character revelation rather than plot turns. No, Terri’s addled uncle isn’t going to die; no, Terri’s not going to lose his virginity. The action revolves around Jacob Wysocki as the title character and John C. Reilly, who never disappoints in any film, as the school principal. Their scenes together are the heart of the film, and if Terri is looking for a father-figure/ role model this off-center administrator with a soft heart for hard cases wouldn’t be a bad choice. To the film’s credit, though, we have little reason to suggest that he’s looking for any such thing. This movie has tact.

I ran into another Ebertfest first-time-director, Nina Paley, whose Sita Sings the Blues (2009) I first saw and loved at Roger’s event. Kristin had already seen it at the Wisconsin Film Fest. Sita worked her way into our blog and into our Film Art material. Nina, long a foe of copyright in any form, told me she plans an act of “copyright civil disobedience” soon. In the meantime, check her effervescent blog site, news of her new project Seder-Masochist, and excerpts from her new books about Mimi, Eunice, and their take on IP.

And then there was…

Take Shelter.

The first evening’s late show was given over to John Davies and Raymond Lambert’s Phunny Business, a documentary about the rise of a Chicago comic club, and this was preceded by Kelechi Ezie’s The Truth about Beauty and Blogs. I had to miss the doc, but go here for a review from Scott Jordan Harris. The short was charming—a snappy comedy about a single woman trying to be Queen of All Media on her YouTube show. Very quickly her aplomb cracks and she uses her online persona to recapture her straying boyfriend. Her web skills give her a rostrum, and then a tracking device (she follows him on Facebook), but soon her site turns into a diary of mounting desperation.

Higher Ground: Not a come-to-Jesus moment but a go-from-Jesus one. I had trouble figuring out the tone. I think the obvious caricatures, including an unctuous evangelical marriage counselor, were there to suggest that the ordinary believers were more worthy of respect. But they all gave me the creeps, including the relentlessly sunny pastor. Also, it seemed a bit of a hothouse drama. I missed a sense of exactly where this story took place, and I kept wondering how all these people made a living wage. But of course it’s Vera Farmiga’s film, and as usual she projects a wary intelligence. The opening sequence showing a string of people being immersion-baptized had a winning radiance.

Joe vs. the Volcano: Joe wins the match, sort of. It deserves to be a cult film for its portrayal of a workday out of the dankest basements of Brazil and Hudsucker Industries. Still, I thought everybody was trying a little too hard, especially Meg Ryan. Cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt talked about how he likes shooting on film and showing on digital: Film’s richness can support 4K, 8K, or whatever. As for 48 frames per second: “I can’t wait.”

Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time: A warts-and-all tribute to the stubborn director of over thirty films. I can’t think of a question to ask about Paul Cox that the film doesn’t answer.

The Alloy Orchestra: Wild and Weird: Classic early trick-films plus a couple of avant-garde items from the 1920s given new brio by the Alloy boys. It was fun but less hefty than earlier efforts. I especially liked re-seeing Winsor McKay’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (aka The Pet) from 1921, which replays McKay’s fascination with figures and spaces that swell to mammoth proportions (a bit like Avery’s King-Size Canary), though the effect is less looming onscreen than in the comics. You can see the whole thing, and other of the W & W titles, on Fandor, one of this years E-fest sponsors.

I’d like to see the Alloy talents and others move away from the big spectacles like Napoleon and Metropolis, which appeal to our current tastes in splashy films with special effects, and toward quieter, less-known silent masterworks by the French (e.g., Germinal), the Danes (The Abyss, The Ballet Dancer, The Evangelist’s Life), Italians (Il Fauno, Rapsodia Satanica, Ma l’amore mio non muore) and above all Victor Sjöström. Audiences would, I think, love Ingeborg Holm, Sons of Ingmar, Masterman, and The Girl from Stormycroft, and the Alloyists could do them proud. Not to mention William S. Hart, whose films are among the pride of US silent cinema.

Take Shelter: A tour de force of what literary theorists call the fantastic: Is the hero going mad, or is there indeed something real behind his visions of impending disaster? Everyone has praised, and rightly, the precision of the performances and framings. Jeff Nichols was another first-timer at Ebertfest some years back, with Shotgun Stories. Take Shelter is the sort of movie that makes independent American cinema proud.

A Separation: I wrote about it here a year ago, having seen it during what might be my last visit to Hong Kong. This time around, I admired it all over again. It shows many characters’ attitudes without bias (everyone has his or her reasons), and it’s aware of how lies told out of loyalty corrode love. The screening was enhanced by excellent background information from Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Omer Mazaffar during the Q and A.

If you’re a good storyteller, I think, you balance straightforward presentation (e.g., A Separation’s exposition, which sketches in the core of a relationship) and somewhat sneaky suppression (e.g., the ellipsis that hides a key event from us). I’ve argued that Iranian directors understand suspense better than almost anybody working today, and this film supports that hunch. Now let’s get hope we get to see, on some platform, Arghadi’s earlier exercise in mystery and ambivalent morality, About Elly. Now there’s an overlooked/ forgotten film.

E-fest goes digital

Ebertfest has shown digital copies of films in the past, notably Bad Santa and Woodstock, but this time around only Take Shelter was on film. Everything else was on HDCam, except Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time, which was on Blu-ray.

James Bond, legendary projection magician and theatre designer/ outfitter, oversaw the shows. Although the films often looked very good on the 50+ -foot Virginia screen, his expert eye saw shortcomings in the digital versions. Even I could detect the videoish quality of Joe vs. the Volcano. It looked pretty good, but compared to what James had shown in years past—70mm prints of Lawrence of Arabia, Play Time, My Fair Lady—there was definitely a sense that we were passing into a new era. Above you see James between his thoroughbreds, the lovingly assembled 35/70mm projectors.

Because Steak ‘n Shake became a festival sponsor this year, Roger presented James with the first-ever S-n-S award, a cap displaying the motto, “In Sight It Must Be Right,” a fitting label for James’ superlative standards in projection. Here he receives the Order of Takhomasak.

James was ably assisted by Steve Kraus and Travis Bird, who is both a musician and a cinephile. Great guys and great professionals, all.

The Virginia Theatre, an analog artifact if there ever was one, is closing after Ebertfest this year. It will be renovated and spiffed up, with new seats and many other upgrades.

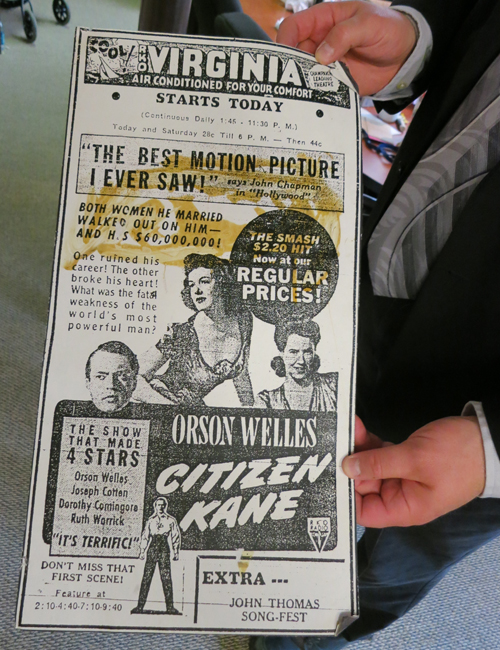

The festival wrapped up with Citizen Kane brought to us digitally. A Blu-ray copy was screened, and instead of the film’s original track, we heard Roger’s pointed and wide-ranging 2001 commentary. He was by this point an old hand at play-by-play explication, after years with his “Cinema Interruptus” series, now taken over by Jim Emerson. After the screening, I was happy to be able to interview Jeff Lerner, of Blue Collar Productions. Jeff produced and recorded Roger’s commentary. Again, check the Ebertfest channel if you want to see the Q & A, which takes off after Chaz’s moving memoir.

Thanks to the many staff and guests who made this year’s Ebertfest especially enjoyable. I’m particularly grateful to C. O. “Doc” Erickson for giving me an interview for an upcoming blog entry, and to David Poland and Michael Barker for enlightening table talk. Thanks as well to Jim Emerson, excellent companion of the highway.

Thanks to Kat Spring and Nate Kohn for correction of boo-boos.

Speaking of digital, here’s a neat possibility: http://gizmodo.com/5906353/the-avengers-screening-delayed-because-some-dunce-deleted-the-freaking-movie.

This deserves a blog entry of its own. The hands belong to Steven Bentz, Virginia Theatre Director, whom we must thank for preserving this ad (from, I assume, 1941). Note the listing of start times for the feature, and the request not to miss the opening. This is a topic discussed elsewhere on this site.

It’s good to be the King of the World

DB here:

Every spring the National Organization of Theatre Owners holds a convention and trade show in Las Vegas. It’s now called CinemaCon, but in earlier times it was known as ShoWest. The gathering assembles thousands of exhibitors from around the world. Directors and stars show up to publicize summer and fall releases. There are screenings, award ceremonies, display booths, and panels about everything from sound systems to popcorn pricing.

The convention is always an extravaganza, but in 2005 things were particularly stirring. Then fewer than a hundred US screens were digital. To ShoWest 2005 came three of the most financially successful directors in history: George Lucas, James Cameron, and Robert Zemeckis. Robert Rodriguez joined them, and Peter Jackson participated in a prerecorded video clip. Their mission: to sell digital cinema.

Battle angels

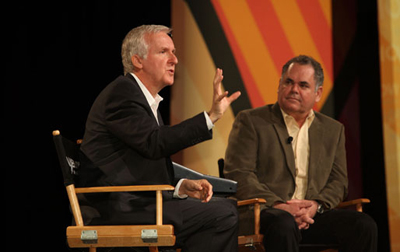

James Cameron and George Lucas at CinemaCon 2011.

Cameron and company knew that the exhibitors needed a rationale for switching that would actually enhance their business. The killer app for digital screening, these directors and others had decided, was 3D.

Lucas claimed that he was hoping to re-release the first Star Wars in 3D in 2007. “We’re giving you two years,” he said pleasantly. Zemeckis announced two 3D films in preparation. In a 3D film clip, Jackson said, “I’m looking forward to one day seeing Hobbits in 3D.” Cameron, who had started working with 3D back in the 1990s, was fresh off the January release of Aliens of the Deep in IMAX 3D. He promised the exhibitors Battle Angel, telling Lucas, “You can have all my theatres when Battle Angel moves out.”

One argument was that 3D offered a way to build the business. 3D screenings would bring in new audiences who seldom went to ordinary movies. More important, the enhanced format would justify higher ticket prices. But of course 3D would necessitate moving to digital projection.

No Battle Angel and no Star Wars IV showed up in 3D, but the celebrity directors kept their word to some extent. Zemeckis led the pack with Beowulf (2007), and Avatar (2009) cemented the deal. With its record $2.7 billion worldwide box office, the latter convinced exhibitors that digital and 3D could be huge moneymakers. In 2009, about 16,000 theatres worldwide were digital; in 2010, after Avatar, the number jumped to 36,000. 3D was the killer app, or Trojan Horse, that pressured exhibitors into going digital.

But here’s the funny thing. At the 2005 confab, the directors summoned up an explanation that goes back to the days when TV threatened the movie trade: You need something special to yank viewers off their couches. In 1953, the bonus was widescreen color images and stereo sound. In 2005, the bonus was stereoscopic projection. All tentpole pictures, Cameron claimed, would be in 3D. “With digital 3D,” he said, “we now have a reason to get people out of their houses from in front of their flatscreen, high-definition TVs and back to the movies.” The premise was that 3D wouldn’t be feasible at home.

Now let’s jump ahead. It’s the 2011 conference of the National Association of Broadcasters. 3D TV is starting to arrive. Celebrity director James Cameron visits with his business partner Vince Case, who have formed the Cameron Pace Group. According to Variety his message to the TV people is:

Your business is about to go 3D. . . . [He said that] the transition to 3D televison as going to happen much faster than usually predicted, even as soon as five years [when] “everything is in 3D and people demand 3D the way people used to demand color, and if you’re not broadcasting in 3D you’re not playing the game and you’re not getting any revenue.”

In 2005 Cameron told filmmakers and exhibitors to shoot in 3D to outrun television. Six years later, when nearly half of movie screens are digital, he advised broadcasters to adopt 3D as fast as possible.

It’s probably not irrelevant that the Cameron Pace Group supplies 3D cameras and assistance to both filmmakers and TV production companies. During the following year, the group announced, it was a 3D equipment provider for CBS Sports and ESPN.

Lest Cameron’s message be missed, he and Pace reiterated it earlier this month. At NAB’s convention he said that sports was only the beginning. Episodic television can also be shot quickly in 3D and easily converted to 2D. Television can’t confine itself to one-off shows or a 3D channel: “We have to hit a critical mass of enough entertainment in 3D.” “The future of 3D,” he told an interviewer, “will be defined by TV.”

Leapfrog

James Cameron and Vincent Pace.

Where does this leave film? Having convinced exhibitors to go digital and to install 3D rigs in their booths, what does Cameron propose to offset the rise of 3D TV? He came to last year’s CinemaCon with a new “incentive”—now all stick and no carrot.

It’s well known that one problem with 3D cinema is a dimmer image. If a vibrant 2D film image is about 16 foot-lamberts, many 3D films are shown at less than four. This turned out to be a problem with screenings of Avatar, which in some venues ran at two foot-lamberts. So Cameron is proposing that exhibitors fit their projectors with gear that permits higher frame rates. Shooting and showing at 48 frames per second (or even 60 fps) instead of the traditional 24 will yield a brighter, sharper picture. Interestingly, 3D TV doesn’t have the same problem with light output, so it’s possible, notes Steven Poster of the ASC, that a 3D HD image would have whiter whites and blacker blacks than a 3D film screening.

Moreover, Cameron prepared a demonstration that showed that in 3D, figure movement and camera movement strobe noticeably at the 24fps rate. They look much smoother at 48fps. This is probably true, but I haven’t noticed problems of strobing in 35mm films by Mizoguchi, Jancsó, Welles, Renoir, and other camera-movement masters. Since they didn’t use our modern 3D, they didn’t encounter the artifacts that Cameron and his peers now brood over.

Having pressured exhibitors to go digital and 3D, Cameron is now asking them to change their equipment to permit him to shoot in a new way he likes better—and to compensate for a deficiency in the 3D system he thrust on them. But he assures them that revamping their projectors is merely a matter of “little tweaks . . . tiny things that make it better.” He has claimed it’s a matter of a software upgrade.

This holds good, evidently, only for the projectors made since January 2010, the so-called “second” series. Projectors made earlier may need replacing. Moreover, one report suggests that the projectors using the Texas Instruments system, the dominant technology in the field, will require not only new software but a new media block. Christie, a major projector manufacturer, says that it will have these available in June for $10,000 apiece.

You have to give Cameron credit for chutzpah. Once more he trots out the argument that theatres have to leapfrog home viewing:

With theatre owners already worried that audiences are abandoning the cinema for the comforts of their home entertainment centers, Cameron argued that exhibitors cannot afford to make the case that “What you’re going to see is special and better than what you have in your home, except the motion sucks.”

The message seems clear. Digital and 3D gave you a competitive advantage for a couple of years, but now it’s time to retool. Those of you who didn’t get 3D along with digital, better start moving, especially if you want Avatar 2 and 3. (Just what Lucas said in 2005 about Star Wars IV 3D, which still awaits us.) And upgrade to 48fps, or even 60. Cameron’s message got support in this year’s NATO convention, when Peter Jackson announced that he’d be trying to induce some theatres to play The Hobbit at 48 fps, the rate at which he’s shooting that 3D production.

Who died and made you King of the World?

I’m left with two observations.

First, there was a time when exhibitors called these directors’ bluff. When Lucas griped that there weren’t enough digital screens for Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of the Sith (2005), John Fithian, president of the National Organization of Theater Owners, replied memorably: “I don’t put projectors in just for Star Wars.”

Now, it seems, the exhibitors are so scared of missing the next blockbuster that the filmmakers can dictate terms. It’s remarkable that these men can do something neither Griffith nor DeMille nor Disney nor any other powerful Hollywood filmmaker of the classic years dared do. They keep asking that the fundamental technology of cinema be changed so we can all watch a couple of their movies for a month or two every few years.

Second, if these guys are so passionately committed to quality, why don’t they make better movies?

For accounts of Cameron’s 3D explorations before Avatar see Christopher Probst, “Future Shock,” American Cinematographer 77, 8 (August 1996), 38-44; Ron Magid, “Digitizing the Third Dimension,” AC 77, 8 (August 1996), 45-50; Jay Holben. “Taking the Plunge,” AC 84, 7 (July 2003), 58-71; and John Calhoun, “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea,” AC 86, 3 (March 2005), 58-69.

According to Cameron, he and Vincent Pace, an expert in underwater cinematography, have been working together since 1988. They began building an HD and 3D system in 1999 and finished their first one in 2000. See the GigaOM interview here. In the same interview Cameron mulls over the prospect of 4K television transmission.

A video showing Cameron’s ideas about digital cinema is available at Filmofilia.

As many have pointed out, higher frame rates were argued long ago for film screenings, notably by Doug Trumbull and Dean Goodhill. (See also Roger Ebert on Goodhill’s Maxivision.) Needless to say, Eastman Kodak enthusiastically supported this initiative, since it would step up film consumption.

This entry is a pendant to the series, Pandora’s Digital Box, which ran on this site earlier this year. That series, reorganized and expanded with new material and arguments, will be available in e-book form later this spring.

Avatar.

Spring comes, bringing movies for Badgers

Good Bye (Mohammad Rasoulof).

DB here:

The thirteen years of our Wisconsin Film Festival have furnished plenty of high-definition moments. I’ll never forget Roger Ebert facing a crowd of a couple of thousand in the Orpheum Theatre to introduce A Hard Day’s Night, or Michael Snow explaining Corpus Callosum to a couple of hundred of the devout in our Cinematheque. We sponsored the first retrospective of Hong Sang-soo’s work—after he had made only three films—and he came along. Hundreds of young filmmakers have visited Madison with their independent works, while we’ve also sponsored some wonderful restorations of classics. Somehow spring always arrives right on time as people line up, chatting, to pass from sunshine into the darkness of our local movie houses, or to the many coffeehouses and pubs near the venues.

Some years the festival has clashed with the Hong Kong International Film Festival, and it’s always been awkward for me to leave Madison for the Fragrant Harbor. But this year, number 14, I can happily stay at home and let the festival come to me.

Roger Ebert and Meg Hamel, Wisconsin Film Festival 2006.

You can see what’s on offer here. Our programming team has gone the full distance for us.

This year’s guests include the distinguished experimentalist Phil Solomon (three programs, one curated by him) and Dan Levin, cognitive scientist and part-time filmmaker , who’s paying tribute to Joel Gersmann in a movie called Filthy Theater. We also have James Schamus of Focus Features. You know him as the award-winning screenwriter of many Ang Lee films and a founder of the Good Machine company, a bastion of bold independent cinema in the 1990s. His New York Times profile is here. James is giving a talk, “My Wife Is a Terrorist” on Thursday at 7:30, and it should be quite something: a narrative analysis of his wife’s Homeland Security file, including, he promises, meditations on redactions.

I thought I’d use today’s entry to signal to Madisonians, and anybody else who’s interested, some of the films that we’re showing that I’ve found worthwhile. In some cases, I supply links to write-ups on this site.

Monsieur Lazhar is a warm drama given astringency by its sudden bits of realism. The mysterious title character takes a teaching post in a primary school and must negotiate between corridor politics and students’ personal problems. Just enough sweetness, just enough toughness, and just enough of an uncertain ending to put it squarely in the Tradition of Quality. That isn’t meant as a complaint.

For me The Devil, Probably is second-tier Bresson, which means first-rate anybody else. People tend to forget that this spiritual director, his eyes supposedly lifted to the clouds and mists of holiness, was also resolutely secular. He was fascinated by young people and their way of being in the world, from the boyish Country Priest to the hapless Mouchette. Moving with the times, he gave us this reflection on post-’68 disenchantment with where things were going. I should see it again. Everybody should.

Good Bye (aka Goodbye) has a bit of Bresson about it. It’s an austere film concentrating on a woman lawyer forced out of her profession and up against a plethora of problems. Her past and present unfold gradually: Every scene has two levels, usually a mundane action that gradually yields hints about her husband, her unborn child, and her plans to leave Iran. A scathing portrait of a culture of bureaucracy, bribery, and surveillancer (the film was smuggled out of the country), Good Bye will stay with you. Kristin talks about it here.

Current, in my view wholly justified, admiration for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy should bring people to The Deadly Affair, Sidney Lumet’s intelligent version of A Call for the Dead. All have had their say about Guinness vs. Oldman as spymaster George Smiley, but what about a 57-year-old James Mason in the role? This time around the sexual jealousies underlying the recent Tinker Tailor are brought to the fore (the title is a pun), with Harriet Andersson as a ravishing Ann Smiley.

Another Brit retrospective item is Alberto Cavalcanti’s Went the Day Well? Kristin spent a whole blog on this surprisingly grim study in complacency overcome by offhand heroism.

One of the very best films we saw at Vancouver last fall was Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (above), which we discuss a little bit here. Somber and mesmerizing, it coaxes you to pay attention. My kind of movie.

Speaking of Hong Kong, there’s one of Johnnie To’s latest, Life without Principle. This story of intersecting destinies during the European financial crisis spurred me to comment at some length here. To is, in my immodest opinion, one of the best directors working anywhere today, and a chance to see his recent work is really splendid. We have a 35mm print, and I’m tempted to go back and see it a third time.

Klown’s outrageous bad manners are perhaps a little too calculated, but this Danish dramedy from Lars von Trier’s company does catch you up. Laced with jokes about pedophilia and manly touching rituals, it seems at first glance a rough-edged bromance. Two pals and a nephew go on a canoeing trip aiming to end at an upscale brothel. After a string of slapstick disasters, the thing looks ominously like it might end in hugs and cheerful tears, but the biggest sting comes in the last few seconds. With a funny, offhand performance by musician Bent Fabric and a walk-on by Jørgen Leth (himself no stranger to outlaw sexytime).

Testosterone to the bursting point is no less on display in Policeman, a bristling, brutal examination of male bonding among Israeli cops. Although it builds to an incendiary action sequence, it’s mostly a study of how people of all classes and political cultures acquire an appetite for violence. Kristin wrote about it here.

Ben Rivers’ Two Years at Sea is a low-key, haunting piece. A portrait documentary? Semi-autobiographical fiction? Experimental film? All three, I guess. And in glorious black-and-white 16mm, which Rivers processes himself. Kristin gives it thumbs up here.

Finally: No film can portray the state of a country at a moment in history, but you’ll be thinking a lot about how today’s Russia might work after you see Elena. A character study of a woman whose ruthlessness is made reasonable and even sympathetic, a thriller centered on how to keep your enemies close, and a sociological study of the haves and have-nots in rapacious capitalism.

Because these are outstanding movies, several are listed as sold out. But some seats have been kept aside, and inevitably some who bought tickets won’t show up. The festival staff tell me that there will be a wait line for each show, and they’ll try to get everybody in. Me, I hope to watch at least a dozen programs, and I’ll try to blog about some in the afterglow. See you there?

Sleepless Night (Nuit blanche; Frédéric Jardin).

Once more, Mad City movies

Night and the City.

DB here:

It’s been a busy time in Madison, at least for me. KT is in Egypt, peering at shards of statues and documenting earlier Armana excavations. I’m at home, having missed the Hong Kong International Film Festival (doctor’s orders) and wistfully wishing I’d been there for the tribute to Peter Chan Ho-sun (check out Fred Ambroisine’s interview at Twitchfilm) and a chance to see—Don’t say whoa!—Keanu Reeves, who was there with Side by Side, his new film on digital cinema (snif).

Instead of traveling, I’ve been doing other stuff. There were, and still are, last-minute checks and fixups on the new edition of Film Art. I went to some movies–Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, The Hunger Games, The Raid: Redemption, Carnage, 21 Jump Street—as well as screenings at our Cinematheque. Late at night I’ve been watching 1940s films for a long-range project. Most frantically, I’ve been working on a little e-book to be finished, I hope, in three weeks. It will be available on this site, ludicrously cheap, you will want one for sure, I bet, well, why not? More about it later.

In the meantime, Madison has hosted some remarkable visits. I’ve already mentioned Lynda Barry’s delightful presentation of Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti. I must also mention two other dignitaries that illuminated our lives this spring.

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

More recently, we were visited by Schawn Belston, an old friend who’s Senior Vice-President of Library and Technical Services at Twentieth Century Fox. Our Cinematheque is running a string of Fox restorations, and Schawn brought along a stunning print of the lustrous noir classic Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950).

There’s a nifty story behind that print. Schawn and archivist (and Badger) Mike Pogorzelski discovered an original camera negative in the Movietone News vault in Ogdensburg, Utah. When they struck our print (directly from the neg) and showed it to Dassin a few years ago, he wept with pleasure.

Schawn found another version of unknown provenance. On the basis of the first reel, which he screened for us, this seems to be a British version, with a different voice-over narrator, varying footage and cutting patterns, and a lighter, more romantic score. As Schawn pointed out, this plays more slowly and is more of a melodrama than a thriller; it also makes the Richard Widmark character a little more sympathetic, I thought. Nobody has yet discovered why this version was made.

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

*Lots of filmmakers are still finishing on film, but the plan is to make no prints available to US theatres after 2012. About 300 prints of current titles will still be made for the world market.

*Both Fuji and Kodak are still making film stock, even new emulsions, but the decline in usage will raise prices. A 35mm print now costs $4000, a 70mm print runs $35,000 and up.

*Storage problems are immense. The studio wants to save all the raw footage; in the case of Titanic, that comes to 2.5 million feet. Which version of the film has priority for the shelf? Typically, the longest cut, often the first preview print.

*All studios are still making 35mm negatives for preservation, typically from 4K scans. Ironically, their soundtracks, usually magnetic, can’t match the uncompressed sound of the files on a Digital Cinema Package (DCP).

*”Film is the most stable medium, but the preservation practices for it are the most vulnerable.”

*Nearly all film restoration is digital now, so the best way to show the results is probably digitally. That also makes for standardized presentation and less wear and tear on physical copies.

*Most classic films in a studio library are not available on DCP. If an archive or cinematheque or theatre wants one, there are ways to make on-demand DCPs. But it’s not cheap. A 2K scan runs $40,000; a 4K scan, somewhat more. Schawn opts for 4K because a digital version should be the best possible. It might be the last chance to make one!

*Films stored on digital files must be migrated frequently. Sometimes that’s done through “robotic tape recycling.” But there are problems with the constantly changing formats and standards. The Movietone News library was originally digitized to ID-1, a high-end broadcast tape format from the mid-1990s, so that material will need to be copied to something more current.

*Schawn believes that objective criteria about color, contrast, and other properties need to be balanced with concern for the audience’s experience. By today’s standards, original copies of Gone with the Wind and The Gang’s All Here look surprisingly muted. But to audiences of the time, they probably looked splashy, because viewers saw so few color movies. Restorers and modern viewers have to recognize that perception of a film’s look is comparative, and the terms of the comparison can change.

Schawn’s point was made after his visit with our Cinematheque show of the restored copy of Chad Hanna (Henry King, 1940). For a Technicolor film, it had a surprising amount of solid black, and not just in night scenes. We’re used to “seeing into the dark” via today’s film stocks and digital video formats, and we probably identify Technicolor with the candy-box palette of MGM musicals on DVD. We sometimes forget that chiaroscuro was no less a resource of color film of the 1940s than of black-and-white shooting of the period. A leisurely, charmingly unfocused story with a radiant Linda Darnell (she lights up the dark) and Fonda at his most homespun, Chad Hanna was good in itself and an education in color style circa 1940.

Schawn’s visit, like Tony’s, was informative and plenty of fun. We want to see both again soon.

Up next, as Robert Osborne would say: Some picks for the Wisconsin Film Festival, which launches Wednesday.

Thanks to Jim Healy, Cinematheque programmer, for arranging Schawn’s visit and the Fox retrospective.

Chad Hanna. Not, emphatically not, from 35mm; from Fox Movie Channel.