Archive for the 'Directors: Capra' Category

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929)

DB here:

The Donovan Affair was Columbia’s first all-talking picture, and Frank Capra’s as well. We discussed it a little in an entry devoted to a Cinema Ritrovato retrospective of Capra’s films. The film lacked, and still lacks, a soundtrack, which may be lost.

The Donovan Affair is an unusually fluid early talkie, and that led me to speculate we might be seeing the silent release version. Wrong! It really does survive only as a sound film without a soundtrack; the Library of Congress print I studied last month has a leader labeled “synchronized version.”

The clunky plot didn’t improve on repeated viewing, but the film did teach me some things about those transitional years 1928-1932, when filmmakers were figuring out how to make a sound feature. I thought I’d share some of those findings with you today.

But I must warn you that there’s one big spoiler coming up. I tell you whodunit. It’s necessary to make a point, but I will warn you just before the offending paragraph, so you can skip if you wish.

Blood-spattered footlights

Murder ran wild on the Anglo-American stage of the 1920s. While melodramas of love and betrayal waned, mysteries rose in popularity. There were plays about gangsters, trials, and domestic homicide. There were comedies of lethal intrigue in spooky settings, like The Bat (1920), The Last Warning (1922), and The Cat and the Canary (1922). A little more seriously, in response the rise of the genteel British detective novel (Christie, Sayers, Allingham et al.), there emerged plays that dumped murder into society drawing rooms.

You know the format. The setting is typically a mansion, with portraits, plush salons, and an impressive library. The victim, usually a bounder, deserves killing. The suspects are both high and low: businessmen, doctors, lawyers, dowagers, flappers, playboys, ne’er-do-wells, gangsters, and servants. Into this ménage steps a police inspector, often with a bumbling assistant, who will more or less skillfully reveal the culprit. In the process, though, someone else is likely to die.

The prototype is Bayard Veiller’s play The Thirteenth Chair (1916), but by the 1920s Britain and the US produced a host of popular and well-reviewed drawing-room mysteries: The Nightcap (1920), In the Next Room (1923), The Creaking Chair (1924), Interference (1927), The Man at Six (1928), The Clutching Claw (1928), and The Canary Murder Case (1928). The most famous entry in this cycle is probably Patrick Hamilton’s Rope (1929), which stands out because it presents the crime from the killers’ viewpoint. The question isn’t “Who did it?” but “Will they get away with it?” Rope’s “inverted” structure (no pun intended; it’s a trade term) was anticipated by A. A. Milne’s The Fourth Wall (1928).

Owen Davis’s play The Donovan Affair (1926) fits snugly into this cycle. The action starts with Inspector Killian and his assistant Carney ushering the suspects into the Rankin family library. The rakish Jack Donovan has been murdered at a birthday dinner. The circumstances are odd: To demonstrate a glowing ring Donovan wears, the lights were turned out. In the darkness, he was stabbed with a carving knife.

Most of those at the table have good reason to kill Donovan. He was having affairs with married women and had an eye on Rankin’s daughter Jean, whom David hoped to marry. The first act is centered on exposition that emerges from Killian’s questioning of the guests. One, Horace Carter, comes forward to declare he knows who the killer is, because the victim’s missing ring was slipped into his pocket. Killian doubts that the ring could have been visible, and so the lights are switched off a second time as a test. Bad idea: When the lights come back on, Horace has been stabbed with the same knife. Score one for law and order. Later one character will shoot another as Killian looks on.

The next two acts expose more motives, lay false trails (David has brought a gun to dinner and has blood on his cuff), and string out physical clues, including a fake ring and some threatening letters to Donovan. In frustration, Killian leaves the suspects to pool their information, in hopes that they’ll discover the killer. Once more the lights are put out to allow the culprit to replace the ring and a missing letter. The killer is revealed, and there’s a struggle in semidarkness. Killian and his men burst in to seize the guilty party.

Among all this claptrap, the blackout gimmick is worked very hard. Bayard Veiller’s Thirteenth Chair had staged a stabbing in a dimly-lit séance, and Davis himself had let the electricity fail in The Haunted House (1924). The blackout-covering-a-killing would be reused in The Spider (1927). The Donovan Affair justifies the device through the luminous ring. In plot terms, it’s another red herring, but it plausibly motivates darkening the stage during the murders. The effect seems to have come off.

The audience found itself frequently strung almost to the endurance limit, and now and then a voice from the crowd would beg a relentless actor not to turn out those lights again. For it was generally in the darkness that stabbings, shootings and assorted mayhem would stalk through the play.

It must have been riveting to see the ring (a green-tinted flashlight) floating around the darkness. Capra’s film is at pains to reproduce this signature effect, but with some differences.

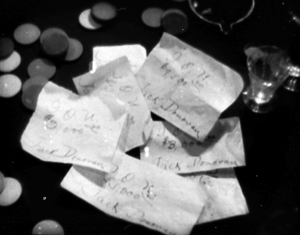

The screenplay subtracts some of the characters and adds a sinister caretaker and Porter, a gambler to whom Donovan owes money. The plot begins well before the crime, with an opening that establishes Porter among his cronies. A second scene shows Donovan brushing off Mary, the Rankin family maid; in the play their liaison is revealed very late. Then guests gather for the birthday dinner, and after some salon byplay they sit down to eat, with Donovan demonstrating the power of the cat’s-eye ring. In the darkness he’s murdered.

A title, “One hour later,” introduces the main stretch of the film, which corresponds more closely with the play’s action. Inspector Killian arrives and sizes up the suspects. Most of the play’s clues emerge, with suspicion scattered around freely.

Like the play, the film is built around blackouts showing off the wandering ring, but now these are motivated as reenactments of the crime. Killian puts Porter in Donovan’s seat, and in the darkness he becomes the second victim. After more intrigue, Killian demands another go-round, and this time the killer is exposed.

The film’s blackout scenes run 36 seconds, 42 seconds, and about 100 seconds for the climax. This last scene varies the treatment by showing some silhouettes.

These scenes feel surprisingly protracted: 30 seconds is a long time on the screen. Likely there would have been dialogue and sound effects, as there are in the play’s blackout intervals.

Here’s the paragraph with the spoiler. In both play and film, the butler Nelson is revealed as the murderer. (At this point in history, having hired help commit the crime wasn’t yet out of bounds.) Nelson is in love with Mary, whom Donovan has seduced. The film hints at this in a way that the play doesn’t. Mary is introduced early as Donovan’s mistress, Nelson seems to have eyes for her, and during a test to see if any woman’s handwriting matches that on a telltale letter, he lingers solicitously over Mary.

Variety praised Capra’s film as well-constructed and surprisingly funny, chiefly because of a whimsical old couple added to the ensemble. Capra claims that The Donovan Affair taught him to add doses of comedy as much as possible: “Comedy in all things.” Actually, though, Owen Davis claimed that he was teasing the genre in his original. “The Donovan Affair was, naturally, a success, although I am, I think, the only one who knows that it was as deliberate a burlesque as The Haunted House had been.”

Opening up the proscenium

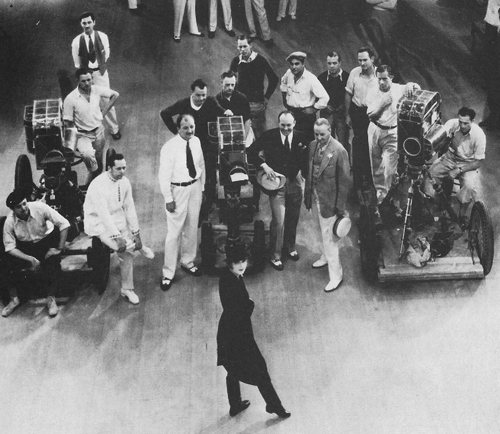

A posed shot of the multiple-camera teams for Sunny (1930).

In his autobiography Capra regarded The Donovan Affair as a turning point in his career. While complaining about the constraints on sound cameras, he regarded the film as “the beginning of a true understanding of the skills of my craft: how to make the mechanics—lighting, microphone, camera—serve and be subject to the actors.” To my way of thinking, what he did within the confines of early talkies was inject some of the pictorial fluidity and impact on display in the silent cinema. The Donovan Affair is a lot less pictorially stilted than most of the 1929 American films I’ve seen.

Like many early talkies, the film relies heavily on multiple-camera shooting of the sort still used in TV comedies and soap operas. For this film, according to Joseph McBride, five cameras were used. The range of coverage allowed for continuous sound recording while preserving the option of analytical editing. While one camera recorded a wide framing, a long lens could scoop out a closer view without moving that camera into the space.

So when Mary calls on Donovan in the second scene, we can see her arrive in a long-lens mid-shot, then we can see Donovan’s reaction in a long shot. Mary comes forward and a third camera picks them up in a two-shot.

The technique permits smooth matches on action, as when Mary turns her head in a medium shot and leaves in the background of the master shot.

But it’s also clear that multiple-camera shooting allowed for alternative takes. The mismatches we can detect across some cuts suggest this. During continuous dialogue, Lydia’s arm is up in one shot and down in the next.

Capra claims that Columbia allowed him to print only one take, but he got around this by not slating his shots. He simply let the camera run and replayed the action, sometimes several times. This allowed actors to improve their performances in a fluid process. CApra wound up with only one take number, out of which he could pick the take he wanted. This tactic might explain disparities of figure position.

Multiple-camera shooting could yield some awkwardness, especially when shot scale wasn’t adjusted. Here’s an interesting example showing Jean’s quarrel with her stepmother Lydia. As Lydia crosses in front of Jean, the match cut on my second frame below creates a little bump by not sufficiently changing the angle and figure size. The slight pan following the women accentuates the disparity.

A jerky cut like this would be very rare later in the 1930s, as it is today. As recording technology improved, Hollywood would move back to single-camera shooting for most scenes, and shot scales were more exactly planned and executed.

If multiple-camera shooting feels a bit theatrical, it’s because it surrenders a degree of freedom in camera placement. We always seem to be watching things from outside a proscenium, even when items are enlarged. I think that the early talkies’ habit of starting with a flamboyant camera movement, as in Sunny Side Up (1929) and The Broadway Melody (1929), was a way of saying, “Don’t worry, this is still cinema.” Capra follows this habit by beginning on a close view of a pile of Donovan’s IOUs and then tracking back very far to set his first scene among the gamblers.

The film’s second “act” starts with a comparable flourish. A long shot of the library shows Carney bustling toward the offscreen front door in the background. The camera tracks in and waits for him to return.

Presumably we would be hearing him greeting Inspector Killian offscreen, but the frame is empty for about fifteen seconds. Then Carney and Killian stride in, and the camera pulls back to something like the initial master framing.

Another way to add fluidity was to insert shots that don’t require lip synchronization. Cutaways to objects or reaction shots could be inserted into the dialogue-laden stretches. For example, Nelson and Mary peer into the library to watch the guests, and Ted Tetzlaff’s cameras give us two shots from positions different than we’ve seen so far.

More boldly, after Donovan is killed, Capra gives us not only a shot of Mrs. Lindsey wailing but brief close-ups of Jean’s and Lydia’s reactions.

These two shots are only 32 and 36 frames respectively, harking back to the punchy montage of silent cinema, and they stand out by contrast with the extreme long-shots around them.

Similarly, you have to think of all those subjective POV shots in 1920s silent films when we watch Killian survey the suspects. As he talks with Rankin, he scans them right to left in a series of POV shots, including one longish, zigzag pan. Here are some extracts.

The end of the pan shot shows Lydia shifting her gaze from Killian to her husband, off left. We then cut to her husband and Killian, who’s just finishing his scanning of the suspects. Her gesture cast suspicion on her; after all, she’s hiding her affair with the dead man.

Most ambitious of all is Capra’s handling of the dinner table situation. Smoothly integrating singles and two shots of characters around a table was one of the triumphs of classical Hollywood style in the late 1910s. Matching character positions and eyelines from shot to shot became part of every director’s craft. Capra adapts talking pictures to these constraints in a flow of shots that include dialogue and keep all characters’ relationships clear and consistent while picking out important details and reactions.

For example, when Donovan talks with Mrs. Lindsey, we get her husband’s glare as he watches from across the table.

Here the proscenium is broken. Instead of covering the action from outside, now the camera penetrates space and can take up a variety of angles among the characters.

This camera ubiquity can be exploited to dramatize the murder weapon. A master shot shows the dinner party, with Rankin at the head of the table and his wife Lydia at the foot, turned from us.

Mary brings the roast and the carving knife to the table. Cut in to Mary lifting the knife, which glints.

Donovan flinches as the reflection dazzles him. Cut to Lydia, from the foot of the table, saying, “Mary,” and looking down the table to where Mary would be.

We’re in a sort of triangular space—Mary-Donovan-Lydia—and the relationships are reaffirmed when a return to the earlier setup shows Mary responding to Lydia’s look.

The dialogue continues within these shots. Capra’s changing setups must have required quite a bit of effort in 1929, what with cameras in booths and the pressures to stick with continuous multi-camera takes. But, reviving silent-film table coverage, he gives us what would be one conventional way to handle such an action in the 1930s.

There are other felicities in the film, but I think I’ve said enough to indicate how it’s an enlightening transitional work. Tied to the multi-camera technique for most of its running time, Capra breaks away for significant stretches. He found a way to give camerawork and cutting some moments of the sort of fluidity that would pervade Hollywood in the 1930s.

Capra wasn’t the only major director to cut his talkie teeth on adaptations of stage thrillers. Hawks made The Criminal Code (1931) from a 1929 prison drama, while Hitchcock based Blackmail (1929) and Number Seventeen (1932) on popular plays from 1928 and 1925. Film mysteries would change in the 1930s, with sophisticated detective comedies like The Thin Man and adaptations of the adventures of Charlie Chan and Perry Mason.

Creaky though it might seem in later decades, the manor-house murder would remain a reference point. On stage its premises were given a new twist in Christie’s The Mousetrap (1952), enhanced with social criticism in J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls (1945), and parodied in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound (1962). You can argue that the provincial procedurals with a British accent (Wexford, Midsomer Murders, Inspector Morse, and so on) grow out of the spillikins-in-the-parlor tradition, but shifting the viewpoint to that of the detectives.

Thanks to Lynanne Schweighofer, Zoran Sinobad, and Mike Mashon of the Library of Congress and Jim Healy, Mike King, and Roch Gersbach of our Cinematheque for arranging my viewing of The Donovan Affair. Thanks also to Ben Brewster for discussions of the film and 1920s theatrical practice.

A fleshed-out synopsis of the film was published at the time.

Bruce Goldstein had the excellent idea of adding live performers to screenings of The Donovan Affair. He details his efforts to find the original dialogue in this TCM article.

Ray Collins fans may be interested to know that in the stage version he played the butler–described in the script as “really the only acting part in the play.”

My quotation about rapt audiences for the stage version comes from the review, “’The Donovan Affair’ Thrills in Mystery,” The New York Times (31 August 1926), 15. Quotations from Capra are from the first edition of his autobiography, The Name above the Title (New York: Macmillan, 1971), 105. Joseph McBride has written the most comprehensive and probing biography, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

In his autobiography Owen Davis remarks that the failure of The Haunted House, a “burlesque mystery melodrama” impelled him to write The Donovan Affair. That was a play that “could hardly be accused of not being mysterious enough, and one that actually dripped with blood and missed no trick at all of the tried and true tricks of mystery story writing from Gaboriau through Poe and Doyle and Anna Katherine Green and Mrs. Rinehart, even taking in the tricks of the present, and very skillful, crop of hard-boiled detective story writers who were at that time printing their first compositions on a slate in some primary school.” See My First Fifty Years in the Theatre (Boston: Baker, 1950), 94-95.

My exploration of theatrical thrillers has been aided by Amnon Kabatchnik’s two excellent reference books: Blood on the Stage: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection: An Annotated Repertoire, 1900-1925 (Scarecrow, 2008) and Blood on the Stage, 1925-1950: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection: An Annotated Repertoire (Scarecrow, 2010).

As ever in such matters, Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website offers background information and critical discussion of authors, periods, and conventions.

On multiple-camera shooting in early sound film, see Chapter 23 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. A good primary source is Karl Struss’s article “Photographing with Multiple Cameras,” TSMPE XIII, 38 (1929), 477-478.

The Donovan Affair (1929).

Foreground, background, playground

The Devil and Miss Jones (1941); The Hudsucker Proxy (1994)

DB here:

I’ve been waiting for thirty years for Alice in Wonderland. No, not the theatrical release of Tim Burton’s version. That interests me only mildly. I’m referring to the DVD release of the 1933 Paramount picture. I saw it on TV as a kid, and remembered it only dimly. But it bobbed up on my horizon in the summer of 1981 when I was doing research on our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was reluctant to attribute pioneering spirit to director Norman Z. McLeod. Instead, I realized that these images’ somewhat freaky look owed more to one of the strangest talents in Hollywood history.

I tried to see Alice in Wonderland, but I couldn’t track down a print. So for years I’ve been waiting to find if it confirmed what I saw on those typescript pages. In the meantime, for the CHC book and thereafter, I’ve bided my time, sporadically looking in on the career of one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. He’s the subject of a new web essay I’ve just posted here (or click on the top item under “Essays” on the left sidebar). Today’s blog entry is a teaser trailer for that.

Deep thinkers

It’s commonplace now to say that Citizen Kane (1941) pioneered vigorous depth imagery, both through staging and cinematography. Many of the film’s shots set a big head or object in the foreground against a dramatically important element in the distance, both kept in fairly good focus. But where did this image schema come from?

The standard answer used to be: The genius of Gregg Toland and Orson Welles. In the 1980s, however, I wanted to explore the possibility that something like the deep-focus look had been a minor option on the Hollywood menu for some time. Once you look, it’s not hard to find Kane-ish images in 1920s studio films, from Greed (1924) to A Woman of Affairs (1929).

During the 1930s, William Wyler cultivated such imagery in some films shot with Toland, such as Dead End (1937), and some films shot by other DPs, such as Jezebel (1938). In turn, Toland had undertaken comparable depth experiments in films with other directors. Moreover, yet other directors, notably John Ford, had used this sort of imagery in films shot by Toland and others, such as George Barnes, Toland’s mentor. There are plenty of non-auteur instances too. (See my post on 1933 Columbia films.) We also find similar imagery in films from outside America. Here’s a stunner from Eisenstein’s Bezhin Meadow (banned 1937).

You see how complicated it gets.

What I concluded in Chapter 27 of CHC was that Toland and Welles didn’t invent the depth technique. They fine-tuned it and popularized it. Their predecessors, in the US and elsewhere, had staged the action in aggressive depth and used many of the same compositional layouts. But the wide-angle lenses then in use couldn’t always maintain crisp focus in both planes (below, American Madness, 1932).

Welles and Toland found ways to keep both close and far-off planes in sharp focus. They deployed arc lamps, coated lenses, and faster film stock. Although it wasn’t publicized at the time, we now know that some of the most famous “deep-focus” shots were also accomplished through back-projection, matte work, double exposure, and other special effects, not through straight photography. Again, though, this tactic was anticipated in earlier films. One of my favorite examples comes from a matte shot in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935).

Menzies seems to have planned for similar fakery. In the script for Alice in Wonderland we find: “CLOSE UP, leg of mutton. The room and characters in the background are on a transparency.”

The flashy depth compositions of the 1920s and 1930s were typically one-off effects, used to heighten a particular moment. Welles and Toland pushed further by making the depth look central to Kane’s overall design and by featuring such imagery in fixed long takes. The prominence of Kane may have encouraged several 1940s filmmakers, such as Anthony Mann, to make the depth schema part of their repertoire. But as the style was diffused across the industry, the hard-edged foregrounds became absorbed into dominant patterns of cutting and spatial breakdown. The static long takes of Kane remained a rare option, perhaps because they dwelt on their own virtuosity.

Digging up films made around the time of Kane, I found many filmmakers experimenting with the look that Toland and Welles highlighted. You can see touches of it in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and All That Money Can Buy (1941). Above all, there are two remarkable movies directed by, of all people, Sam Wood. Our Town (1940) turns Wilder’s play (itself surprisingly melancholy) into a Caligariesque exercise.

Several shots anticipate the low-slung depth, bulging foregrounds and all, that became the hallmark of Citizen Kane a year later.

Our Town also uses postproduction techniques that yield depth-of-field effects you couldn’t get in camera.

Perhaps even more startling is Wood’s Kings Row (1942), with deep-focus imagery that occasionally rivals Kane‘s.

From the evidence I was encountering, it seemed that Welles and Toland’s accomplishment was to synthesize and push further some deep-space schemas that were already circulating in ambitious Hollywood circles. Connecting some dots, I realized that one of the earliest champions of aggressive imagery in general, not just big foregrounds and deep backgrounds, was William Cameron Menzies.

Menzies frenzies

Menzies started out as an art director, most famously for United Artists. He designed sets for Mary Pickford’s Rosita (1923, directed by Lubitsch) and several Fairbanks films, notably The Thief of Bagdad (1924). He won the first Academy Award for set design and went on to a noteworthy career—most famously as production designer for Gone with the Wind (1939). He also directed films, such as Things to Come (1936) and Invaders from Mars (1953). Most significant for my purposes, he was production designer for Our Town, Kings Row, and three other films of the early 1940s directed by Sam Wood. And he designed the 1933 Alice in Wonderland. The drawings I saw in Edouart’s script were by Menzies or his assistants.

Menzies was one of the chief importers of German Expressionist visuals to the US. Although his early efforts leaned toward Art Nouveau effects, by the end of the 1920s he was cultivating a dark, contorted look keyed to the harsh geometry of city landscapes.

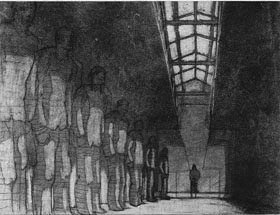

Since the late 1920s, Menzies had explored the possibility of steep depth compositions. He didn’t usually employ a big foreground, but he did favor overwhelming perspective–either abnormally centered or abnormally decentered. Here is his sketch for Roland West’s Alibi (1929) and the shot from the finished film.

Menzies loved slashing diagonals created by architectural edges and worm’s-eye viewpoints. The harrowing opening of Things to Come is full of such flashy imagery.

Menzies calmed his style down for GWTW, although the sequences he directed bear traces of his inclinations. And in his work for other directors he managed to slip in a few odd shots. Here, for instance, is a typically maniacal central perspective view from H. C. Potter’s Mr. Lucky (1943). Squint at this image and you’ll see that it’s weirdly symmetrical across both horizontal and vertical axes.

When he met Sam Wood, it seems, Menzies found a director ready to let his imagination roam further. In these collaborations, we get depth shots à la Welles and Toland, but also skewed perspectives. Pride of the Yankees (1943/44) searches for ways to make a baseball stadium look like a Lissitzky abstraction.

Menzies subjects the partisans of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1944) to his sharp diagonals as well.

Alice, we hardly knew ye

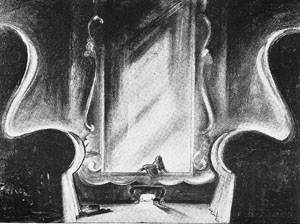

What then of Alice in Wonderland? Back in the early 1980s, I wasn’t permitted to photocopy or photograph script pages. Here is one of the few sketches I later found for the film. Alice crawls into the mirror with looming armchairs in the foreground.

Surely, I thought, the film would be an early example of the depth aesthetic that would be developed by Welles, Wyler, and Wood/ Menzies. Alas, the film has nothing like those imperious armchairs.

In fact, Alice proves a huge disappointment on the pictorial front. Menzies expended all his ingenuity on the special effects, coordinated by Paramount master Farciot Edouart. Although the spfx are not in the league of that other big 1933 effects-film King Kong, they are pretty solid for the time. It’s just that this remains a painfully arch, flatly filmed exercise.

But I look on the bright side. Menzies created some memorable movies, both on his own and with other directors. (Of his directed films, not only Things to Come but Address Unknown, 1944, remain of interest today.) Perhaps most important, his stylistic boldness may have encouraged other filmmakers to try something fresh. Most immediately there is Since You Went Away (1944), a big Selznick production that bears traces of the Menzies touch.

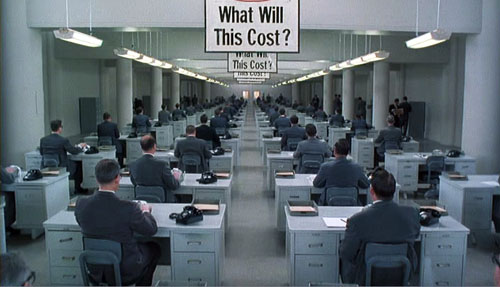

More broadly, Menzies represents a strand in American cinema that never really disappeared. His frantic Piranesian perspectives, canting the camera and filling the frame with grids, whorls, and cylinders, are still in use. And his head-on, wide-angle grotesquerie looks ahead to the Coen brothers. This shot of a department-store manager in The Devil and Miss Jones (1941) could come from any of their films.

Menzies’ films, though mostly not celebrated as classics, gave American cinema the permission to be peculiar. Meet me in the sidebar for a closer look at one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. Special thanks to Meg Hamel for going beyond the call of duty in posting that essay.

Invaders from Mars (1953); Shutter Island (2010).

Kurosawa’s early spring

The Most Beautiful (1944).

For Donald Richie

DB here:

Cinephile communities aren’t free of peer pressure. Sometimes you must choose or be thought a waffler. In postwar France, the debate within the Cahiers du cinéma camp often came down to big dualities. Ford or Wyler? German Lang or American Lang? British Hitchcock or American Hitchcock? In the America of the 1960s and 1970s, we had our own forced choices, most notably Chaplin or Keaton?

This maneuver assumed that a simple pair of alternatives could profile your entire range of tastes. If you liked Chaplin, you probably favored sentiment, extroverted performance, and direction that was straightforward (“theatrical,” even crude). If you liked Keaton, you favored athleticism, the subordination of figure to landscape, cool detachment, and geometrically elegant compositions. One director risked bathos, the other coldness. The question wasn’t framed neutrally. My generation prided itself on having “discovered” the enigmatic Keaton, in the process demoting that self-congratulatory Tramp. Keaton never begged for our love.

Of course it was unfair. The forced duality ignored other important figures—Harold Lloyd most notably—and it asked for an unnatural rectitude of taste. Surely, a sensible soul would say, one can admire both, or all. But we weren’t sensible souls. Drawing up lists, defining in-groups and out-groups, expressing disdain for those who could not see: it was all a game cinephiles played, and it put personal taste squarely at the center of film conversation.

In the 1950s another big duality slipped into Paris-influenced film talk. Virtually nobody knew about Ozu, Shimizu, Gosho, Naruse, Shimazu, Yamanaka, et al., so two filmmakers had to stand in for the whole of Japanese cinema. Mizoguchi or Kurosawa?

A problematic auteur

For Cahiers the choice was clear. Mizoguchi was master of subtly shaping drama through the body’s relation to space, thanks to quiet depth compositions and modulations of the long take. In Japan, land of exquisite nuance, the dream of infinitely expressive mise-en-scene seemed to have come true.

There seemed to be nothing nuanced about Kurosawa, whose brash technique, overripe performances, and propulsive stories seemed disconcertingly “Western.” Sold, like Satyajit Ray, as a humanist from an exotic culture, he played into critics’ eternal admiration for significance. This director wanted to make profound statements about the bomb (I Live in Fear), the relativity of truth (Rashomon), the impersonality of modern society (Ikiru), and the complacency of power (High and Low, The Bad Sleep Well). Even his swordplay movies seemed moralizing, with the last line of Seven Samurai (“The victory belongs to these peasants. Not to us.”) summoning up a cheer for the little people. Kurosawa could thus be assigned to Sarris’s category of Strained Seriousness. “He’s the Japanese Huston,” said a friend at the time.

But there was no overlooking his cinematic gusto. He made “movie movies.” He flaunted deep-focus compositions, cunningly choppy editing, sinuous tracking shots (through forests, no less), dappled lighting, and abrupt addresses to the viewer, by a voice-over narrator or even a character in the story. He exploited long lenses and multiple-camera shooting at a period when such techniques were very rare, and he may have been the first director to use slow-motion for action scenes. Bergman, Fellini, and other international festival filmmakers of the 1950s didn’t display such delight in telling a story visually. If you liked this side of his work, you overlooked the weak philosophy. On the other hand, if you found the style too aggressive, it could seem mere calculation on the part of a man with something Important to say.

The case for the defense was made harder by the fact that he was a controversial figure at home as well. Japanese critics I met over the years expressed puzzlement about Western admiration for the director’s style. I was once on a panel in which an esteemed critic blamed Kurosawa for influencing Western directors like Leone and Peckinpah. His violence and showy slow-motion had helped turn modern cinema into a blunt spectacle. No wonder Lucas, Spielberg, Coppola, and Walter Hill have loved this macho filmmaker.

Today passions seem to have cooled, but I should confess that my own tastes remain rooted in my salad days (1960s-1970s). I could live happily on a desert island with only the films of Ozu and Mizoguchi. I’d argue forever that Japanese cinema of the 1920s through the 1960s is rivaled for sheer excellence only by the parallel output of the US and France. (For more on this matter, see my blog entry on Shimizu.) On Kurosawa, however, my feelings are mixed. I still find most of his official classics overbearing, and the last films seem to me flabby exercises. But there are remarkable moments in every movie. Overall, I’ve responded best to his swordplay adventures; Seven Samurai was the first film that showed me the power of the Asian action aesthetic. I think as well that his earliest work up through No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), along with the later High and Low and Red Beard, are extraordinary films. And, like Hitchcock and Welles, he is wonderfully teachable.

We don’t live on desert islands, and gradually we’re gaining easy access to the range of Japanese filmmaking of its great era. We can start to see beyond the fortified battlements set up by generations of critics. With so many points of entry into Japanese cinema, mighty opposites lose their starkness; polarities dissolve into the long tail. Nevertheless, personal tastes take you only so far, and objectively Kurosawa still looms large. Whatever your preferences, it’s important to study his place in film history and film art.

Gauging that place involves thinking outside some traditional conceptions of how films work. Like most ambitious Japanese directors, Kurosawa provides bursts of cinematic swagger. This six-shot passage from Rashomon revels in its own strangeness.

Here traditional over-the-shoulder shots submit to a brazen geometry. Out of an ABC film-school technique Kurosawa creates a cascade of visual rhymes and staccato swiveled glances. Yes, an ingenious critic could thematize this bravura passage. (“The symmetries put the central characters, each of whom asserts a different version of what happened, on the same visual and moral plane.”) Instead I’m inclined to think that the shots constitute a little thrust of “pure cinema,” a brusque cadenza that keeps our eyes, if not our hearts or minds, locked to the screen. From this angle, Kurosawa claims some attention as an inventor of, or at least tinkerer with, the disjunctive possibilities of film form.

His centenary arrives in 2010, and the occasion is celebrated by Criterion with a set of twenty-five DVDs. Most of these titles have already been available singly, and the discs lack all the bonus features we have come to admire from the company. Yet the crimson and jet-black box, the discreet rainbow array of slip cases, and the subtly varied design of the menus add up to a good object, like the latest iPod—something you want even if it means re-buying things you already have. There’s also a handsome picture book with notes by Stephen Prince on each film.

To viewers who need the assurance of cultural importance, this behemoth announces: You must know Kurosawa to be filmically literate. And that’s more or less true. Just as important, the inclusion of four rarities from his early years gives the collection a claim on every film enthusiast’s attention. One hopes that those titles will eventually appear separately, perhaps in an Eclipse edition. [See 15 May 2010 update at the end.] For now these copies of the wartime features are far better than the imports I’ve seen.

The Big Box makes it tempting to mount a career retrospective on this site, but that’s far beyond my capacity. Future blog entries may talk more of this complicated filmmaker, but for now I’ll confine my remarks to these early works. They offer plenty for us to enjoy.

Audacious propaganda

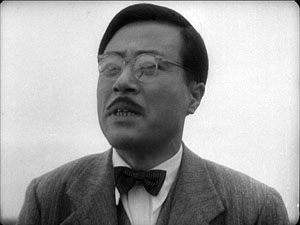

Although Kurosawa was only seven years younger than Ozu, he belongs to a distinctly different generation. Ozu directed his first film in 1927, at the ripe age of twenty-four. He grew up with the silent cinema and made masterful films in the early 1930s, during the long twilight of Japanese silent filmmaking. Kurosawa became an assistant director in the late 1930s. Although he evidently directed large stretches of Yamamoto Kajiro’s Horse (1941), he didn’t sign a feature as director until he was thirty-three. His closest contemporary, and a director whom some Japanese critics consider his superior, is Kinoshita Keisuke. Kinoshita was born in 1912 and his first feature, The Blossoming Port, was released in the same year as Kurosawa’s debut.

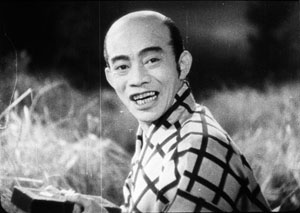

Kurosawa and Kinoshita began their careers making wartime propaganda. Their task was to display Japanese self-sacrifice and spiritual purity in stories of both the past and the present. In the Sanshiro Sugata films (1943, 1945), Kurosawa presents judo as an integral part of Japanese tradition and a path to enlightenment. Much of the external conflict is devoted to uniting martial arts (ju-jitsu, karate) under the rubric of the less aggressive but more powerful judo, and to showing how it can defeat American-style boxing. But the internal dimension is also important. Judo is a means of tempering character and accepting one’s proper place. Humble, unflagging devotion to one’s vocation becomes heroic.

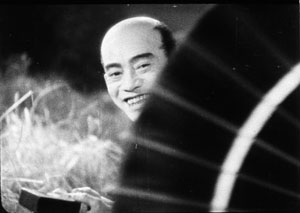

The same quality can be found in The Most Beautiful (1944), a story of teenage girls working in a factory manufacturing lenses for binoculars and gunsights. Vignettes from the girls’ lives dramatize the need for cooperation and sacrifice, even as wartime demands for output threaten the girls’ health.

A more detached conception of the Japanese spirit underlies The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail (1945). This adaptation of a plot from Noh and Kabuki theatre shows officers escorting a general through enemy territory. Disguised as monks, the bodyguards are forced to bluff their way through a checkpoint. The situation is one of hieratic suspense, made more tonally complex by Kurosawa’s addition of the movie comedian Enoken. Enoken plays a dimwitted porter reacting to the charade played out by his betters. By dramatizing one of the most famous episodes in Japanese literature, Kurosawa was reasserting the tradition of devotion to duty and honor. The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail was released the same month that the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima.

During earlier decades, Japanese cinema had created a complex tradition. In part, it conducted a sustained dialogue with Western cinema. Tokyo had access to a wide range of Hollywood movies, and directors studied American technique closely. Just as Ozu would not be Ozu without his early fondness for Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd, Mizoguchi learned a good deal from von Sternberg. Between 1938 and 1942, alongside German imports Tokyo theatres screened Fury, Only Angels Have Wings, The Sea Hawk, The Awful Truth, Angels with Dirty Faces, Boys Town, Young Tom Edison, Only Angels Have Wings, and many French titles. In 1942, with Hollywood films now banned, one could still see René Clair’s Le Million and À Nous la liberté—films that had been circulating in Japan since the early 1930s and could have served as models of flashy sound technique. It’s misleading to talk of Ozu as “purely Japanese” and Kurosawa as “Western”: All Japanese directors of the 1920s and 1930s were deeply acquainted with Western cinema, and American cinema in particular furnished a foundation for most local filmmaking.

Yet there are crucial differences. Japanese cinema welcomed extremes of stylistic experimentation that would have been rare in Western cinema. The 1920s swordplay films (chambara) pioneered rapid editing, handheld camerawork, and abstract pictorial design. (I supply some examples here.) Directors working in the contemporary-life mode (the gendai-geki) experimented similarly, often achieving remarkable visual effects and bold stylization. Mizoguchi and Ozu have become our emblems of this creative rigor and richness, but they are the peaks of what was a collective approach to filmic expression. Not every film was an experiment—indeed, most behave like Hollywood or European productions—but many ordinary movies, signed by unheralded directors, exhibit flashes of unpredictable imagination. This was the tradition of permanent innovation that directors of the Kurosawa-Kinoshita generation inherited.

As the war dragged on, however, Japanese studio productions lost much of their audacity. Production fell from over 400 films in 1939 to fewer than 100 in 1943. Censorship may have made filmmakers cautious about style as well as subject and theme. Most of the fifty-plus films I’ve been able to see from the period 1940-1945 are quite conservative aesthetically. Several of these seem to me quite good, but they rely on fairly standard Hollywood technique sprinkled with touches that had become markers of Japanese cinema (sustaining scenes in rather distant shots, using cuts rather than dissolves to shift scenes, and so on). Swordplay films become more severe and monumental. Even Mizoguchi’s Genroku Chushingura (1941-42) and Ozu’s There Was a Father (1942), superb as they are, are more elevated in tone than the directors’ earlier works.

Against this backdrop, Kurosawa’s films stand out; they are the most extroverted works I know in this period. Their innovations remain vivid; Sanshiro Sugata, for one, with its hierarchy of competitors, its rivalry among schools, and its visceral technique, may have invented the modern martial arts film. But we should also realize that these early films build upon the traditions already firmly established in Japanese cinema.

Playing with the passing moment

Consider transitions. Kurosawa is famous for his elaborate links between sequences, from the hard-edged wipes to swift imagistic associations. But we should recall that transitional passages offer moments of flashy style in American and European cinema of the 1920s and 1930s, and indeed right up to this day. (For examples, go here and here.) In the same year as Sanshiro, Kinoshita gave us this moment in Blossoming Port. A con artist is trying to bilk money from a town. He bows, leaving an empty frame.

Without a discernible cut, heads pop into the empty frame, rocking to and fro.

Another cut reveals that the people we see are in a boat tossing on the waves, and the conman’s partner is enjoying an outing with the locals. Kurosawa’s scene-changes—sites of what Stephen Prince has called “formal excess”—can be seen as prolonged, imaginative reworkings of this tricky-transition convention.

Japanese filmmakers were more willing to play with the expressive and “decorative” side of filmmaking than most of their Western peers. Directors created not only flashy transitions but moments of stylistic playfulness within scenes. Sometimes this just adds to the overall tone of comedy, as in this pretty passage in Heiroku’s Dream Story, another 1943 release. The hero, played by Enoken, is squatting and talking to a charming girl (Takamine Hideko). She twirls her parasol between them, and we get a straight-on cut that creates a moment of abstraction as the parasol glides across the frame in contrary directions. (The vertical pair of frames shows the cut.)

This decorative symmetry would be rare in Hollywood outside a Busby Berkeley number, but it enlivens the characters’ exchange in a way similar to the more dramatic Rashomon sequence. To borrow a phrase that Kepler applied to nature’s way with snowflakes, a filmmaker may seek to ornament a scene by “playing with the passing moment.”

Likewise, in The Blossoming Port, as an older woman recalls a romance of her youth, the natural sound fades out and the back-projection behind the carriage shifts from the seaside to urban imagery of the period she’s remembering.

The frank artifice of this shot shows that Japanese filmmakers were eager to let us enjoy the forms with which they were working.

A similar explicitness about style can be seen in one of Kurosawa’s signature devices, the axial cut. This technique shifts the framings toward or away from the subject along the lens axis. If the shots are short enough, we sense a bump at the abrupt change of shot scale.

Kurosawa often uses this cutting to stress a momentary gesture or to prolong a moment of stasis. But it can structure a simple dialogue scene as well. In Sanshiro Sugata, the hero’s first conversation with Sayo takes place as they descend a stair toward a gateway. Kurosawa uses axial cuts to keep up with them as they move away from us down the steps. Illustrated with stills, this technique looks like a forward camera movement, but in fact these images come from separate shots.

The crux of the scene is Sayo’s revelation that the man Sanshiro must fight is her father, and instead of big close-ups to underscore his reaction, Kurosawa simply lets his hero halt while Sayo continues down the steps. The steady pattern of cut-ins to the characters’ backs makes Sayo’s sudden turn to the camera more vivid, and Sanshiro’s reaction is underplayed by not giving us direct access to his face.

An earlier entry traces theaxial cut back to silent film, when its jolting possibilities were exploited in Soviet montage cinema. Japanese directors also used the device often. Yamanaka Sadao, one of the most-praised directors of the 1930s, used axial cuts prominently in an early dialogue scene of Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937). The cuts are accentuated by low-height compositions that maintain the steep perspective of the street.

The technique gains more punch in Japanese swordplay films. Here is a percussive instance from Faithful Servant Naosuke (1939), four short shots yanking us inward in a way that Kurosawa would make his own.

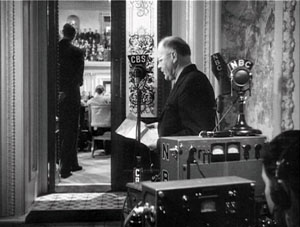

Tom Paulus reminds me that Capra films sometimes make use of this technique, as in this string of concentration cuts from Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

Interestingly, Mr. Smith ran on several Tokyo screens in October 1941; it may have been the last Hollywood feature to receive theatrical distribution before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

To say that Kurosawa adapts traditional devices doesn’t take away from his accomplishment. No artist starts from zero, and in commercial cinema, filmmakers commonly revise schemas already in circulation. So Kurosawa puts his own spin on the axial cut, not only by using it frequently, but also by varying it in the course of a film. Sanshiro Sugata 2 makes the axial shot-change a sort of internal norm, but then varies it: inward or outward, cuts or dissolves, how great a variation of scale? When Sanshiro leaves Sayo, the three phases of his departure are marked by simple repetition: each time he halts and looks back, she responds by bowing.

Like the Rashomon sequence, this shows Kurosawa’s fondness for permuting simple patterns. But there’s an expressive payoff too. The framings that make Sayo dwindle to a speck give the axial cuts the forlorn, lingering quality we usually associate with dissolves. In addition, for viewers who know Sanshiro 1, the scene calls to mind the staircase passage we’ve already seen. Their first extended encounter is paralleled by their last one.

Axial cuts are easier to handle when the subject is unmoving, or moving straight toward or away from the camera. What about other vectors of motion? In The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, as the general’s bodyguards file out of the compound, they pass a line of soldiers in the foreground. Kurosawa combines concentration cuts with lateral cutting, so our men stalk leftward through the frame once, then again, then again, each time both closer to us and further along the row of soldiers.

Kurosawa revises other traditional techniques. You can find moments of extended stasis in swordplay films of earlier decades, and the technique surely owes something to the prolonged mie poses in Kabuki. But Kurosawa’s early films turn long pauses into living freeze-frames. Instead of using an optical effect, he simply asks his actors not to move! One combat in Sanshiro shows the audience caught in absolute stillness, staring at the result of Sanshiro’s throw. In Sanshiro 2, our hero and the boxer stand like statues in the prizefight ring until the American collapses. And in The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, the groups gathered at the checkpoint are absolutely unmoving for nearly fifty seconds as Benkei leads them in prayer.

This shot’s tactful, reverential composition echoes a fairly standard image for showing loyal retainers; here’s an example from a 1910s version of Chushingura.

In sum, I think that for his “manly movies” Kurosawa sifted through the Japanese film tradition and pulled out the most vigorous techniques he could find, all the while recognizing that rapid pacing needs the foil of extreme immobility. He compiled a digest of many arresting visual schemas available to him, and then pushed them in fresh directions. He realized as well that he could apply this sharp-edged style to genres dealing with modern life.

A most stubborn young woman

Although we think of Kurosawa as a “masculine” director, two of his finest films center on women. The Most Beautiful and No Regrets for Our Youth can be thought of as propaganda, but this label shouldn’t put us off. Propaganda works partly because it taps deep-seated emotions, and I’d argue that the formulaic nature of a “social command” can allow filmmakers a chance at emotional and formal richness. Because the message can be taken for granted or read off the surface, an ambitious director can go to town—nuancing the presentation, complicating its implications, taking the clichéd message as an occasion for pushing formal experiment. (Which is one aspect of what the Soviet montage filmmakers did.)

The Most Beautiful, probably the best movie ever made about child labor, starts off as a doctrinaire effort. Before even the Toho logo fades in, a title declares: “Attack and Destroy the Enemy.” The first fifteen minutes are filled with pledges to help the war effort, work to meet an emergency quota, obey orders, display filial devotion, build noble character, and think constantly of how making flawless lenses saves soldiers’ lives. The rest of the movie focuses on the pain of doing all this. This story of patriotic affirmation is steeped in tears.

The film’s structure looks forward to the ensemble-based, threaded plotlines employed in Red Beard and Dodes’kaden. We follow various stories, if only briefly, as the teenage girls push themselves beyond the limits proposed by their overseers. The factory directors and the dormitory mother are barely characterized, so that the focus falls on the girls who have left their homes to serve their country. One looks out the window when a train passes; another walks sobbing across a garden made of heaps of earth from each girl’s native village. When one girl falls from a roof, she promises to keep working on crutches. Another hides the fact that she has a fever. In this movie, workers cry out “Mother!” in their sleep.

Sanshiro Sugata pulses with the exuberance of a young man’s body itching for constant movement. Kurosawa’s second film applies his muscular techniques to a static situation: Girls bent over machines. True, there are interludes of a marching and volleyball, the latter calling forth a standardized stretch of montage, but the director’s central task is to dynamize conversations. He finds a remarkable array of options. We get good old axial cutting, but there are also jump cuts (as if the action were too urgent to wait for dissolves), resourcefully simple staging (see this entry), abrupt close-ups, quick flashbacks, and judicious long takes jammed with actors.

Off on the right stand two tall girls frowning and looking down; their quarrel will burst out in a later scene.

The virtuosity here is quieter than in Sanshiro, largely because of the insistent threat of shame. A Hollywood film of the period might play up the triumphant achievement of the quota, but here this goal fades away. Instead, the plot is driven by a nearly desperate fear of failure. The men in charge offer bluff reassurance, but in a reprise of high-school nerves, the girls fret constantly about doing less than their mates. Their anxiety is translated into gesture-based performance—not through Western hysteria but through gestures of lowering the eyes, bowing the head, turning one’s back. The Most Beautiful has some of the greatest back-to-the-camera scenes in film history, and Kurosawa doesn’t hesitate to insert some of these moments in wide shots, creating a delicate emotional counterpoint. At one moment the girls are distracted by a passing airplane but their leader is sunk in thought; at another moment the girls challenge the leader while her accuser can’t face her.

The girls’ stories are woven around Watanabe, the section leader. Somewhat older than the others and nowhere near as spontaneous or joyous, she’s the emblem of unremitting self-sacrifice. If Sanshiro matures in the course of his films, learning the humbling responsibilities of becoming a supreme fighter, she comes to her more mundane task already grown up. Noël Burch has pointed out that Kurosawa’s protagonists are notably stubborn, and Watanabe offers a prime instance.

At the climax she has to search through thousands of lenses for a flawed one that she accidentally let through. Kurosawa forces us to watch her, exhausted from hours of work, hunched over her microscope and keeping awake by singing a patriotic song. One shot holds on her groggy efforts for over ninety seconds, so we register both the enormity of her task and her obstinate refusal to quit. This shot will be paralleled by the film’s final one, which lasts almost exactly as long, when she returns to her workbench. Now her concentration is broken, again and again, by quiet weeping. Kurosawa claims that when he made the film he knew Japan would lose the war.

The ending of The Most Beautiful calls to mind a moment in another Kinoshita film, again one released in the same year as Kurosawa’s. Army (1944) ends on a similarly ambivalent note, with a frantic mother pushing through a crowd cheering recruits marching off to war. Through cries of “Banzai!” she stumbles along to get a last glimpse of him, but soon her trembling figure is lost in the excitement. It isn’t exactly an exalted note on which to close a patriotic film.

A mother is central to Watanabe’s sacrifice in The Most Beautiful as well, and her plight reminds me of historian John Dower’s telling me that Japanese soldiers may have charged into battle shouting the name of the emperor, but many died murmuring, “Mother.”

Like other filmmakers, Kurosawa had to execute an about-face when the Americans came to occupy Japan. Along with Mizoguchi, Kinoshita, and most others, he began to make films that condemned the “feudal” forces that had led Japan to war and affirmed the need for liberalizing the society, not least with respect to women’s roles. Kurosawa’s contribution was No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), a survey of the 1930s and 1940s through the experience of a daughter of the middle class. At first she’s oblivious to the authoritarian threat and then, awakened to her social mission, she plunges into what we would now call the politics of everyday life. With the same verve that Kurosawa dramatized sacrifice for the motherland, he quickens a liberal fable of emerging political consciousness. Again, he finds ways of making propaganda deeply moving, while leaving his unique stamp on the project.

I hope to write about No Regrets and other Kurosawa titles in the future. But one implication should already be clear. Kurosawa remains on our agenda through his commitment to a mode of storytelling that pursues vigor without lapsing into the diffuse busyness of today’s spectacles. He stretches our senses through staccato action, yet he drills into other moments so implacably that we are forced to see deeper. He lifts certain Japanese and imported traditions to a new pitch, in the process often creating something indelible and enduring.

The point of departure for all things Kurosawa is Donald Richie’s Films of Akira Kurosawa, first published in 1965 and updated since. It was a trailblazing auteur study, written from deep knowledge of the films and many encounters with the director. Another indispensible source is Kurosawa’s Something Like an Autobiography (Knopf, 1982). Although it stops after the success of Rashomon, the book offers fascinating information about Kurosawa’s early life and first films. (“The Most Beautiful is not a major picture, but it is the one dearest to me.”) Information on the later films is collected in Bert Cardullo, Akira Kurosawa: Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2008). A biographical overview, with details on each film’s production, is provided in Stuart Galbraith IV, The Emperor and the Wolf (Faber, 2001).

For background on Japan’s wartime cinema, the central work is Peter B. High’s The Imperial Screen (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003). See also John Dower’s magnificent surveys of the war and the postwar period, War without Mercy (Pantheon, 1987) and Embracing Defeat (Norton, 2000).

Noël Burch argues that Kurosawa is best understood as working within a tradition of indigenous Japanese art; his pioneering To the Distant Observer (University of California Press, 1979) is available online here. Linking formal preoccupations to changing subjects and themes, Stephen Prince’s The Warrior’s Camera (Princeton University Press, 1999) argues that Kurosawa was forging heroic figures appropriate to developments in Japanese society. In Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema (Duke University Press, 2000), Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto puts the films in political contexts, while also considering how Kurosawa has been understood within the Western academy.

Critics have long recognized that Kurosawa’s formal inventiveness came with an impulse toward large statement. Brad Darrach reconciled the two tendencies in an overheated specimen of Timespeak:

Not since Sergei Eisenstein has a moviemaker set loose such a bedlam of elemental energies. He works with three cameras at once, makes telling use of telescopic lenses that drill deep into a scene, suck up all the action in sight and then spew it violently into the viewer’s face. But Kurosawa is far more than a master of movement. He is an ironist who knows how to pity. He is a moralist with a sense of humor. He is a realist who curses the darkness—and then lights a blowtorch.

This comes from “A Religion of Film,” a remarkable primer on the art cinema in its American spring. It was published in Time of 20 September 1963 and is available here. The same antinomy of stylist vs. moralist persists, with less complimentary results, in Tony Rayns’ obituary in Sight and Sound (October 1998), p. 3 and in Dave Kehr’s recent review of the Criterion boxed set.

I wrote about Kurosawa’s work in our textbook Film History: An Introduction (third edition, McGraw-Hill, 2009), pp. 234-235 and 388-390. My larger arguments about classic Japanese film can be found in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (online here) and in two articles in Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), “A Cinema of Flourishes: Decorative Style in 1920s and 1930s Japanese Film” and “Visual Style in Japanese Cinema, 1925-1945,” which analyzes some of the films I’ve considered here. I talk a little more about editing in Seven Samurai in this entry. In another I discuss how Kurosawa’s “humanism” fits into one 1950s ideological framework.

Yamanaka’s Humanity and Paper Balloons is available on DVD in the Eureka! series. For a cinematic homage to early Kurosawa, see Johnnie To’s Throw Down.

Thanks to Komatsu Hiroshi for supplying the date of Faithful Servant Naosuke. And as a PS, thanks to Luo Jin for pointing out a “slip of the finger”: the original post had Kurosawa older than Ozu!

PPS: 9 December: The Criterion site has just posted a reminiscence of Kurosawa by Donald Richie.

PPPS: 15 May 2010: Criterion has just announced that the four films discussed in this entry will be released as a separate collection on the Eclipse label.