Tuesday | March 4, 2025

Kristin here:

Students and faculty in the film-studies division of the Department of Communication Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison are known for aesthetic analysis of films and historical study of the film industry. One aspect of the latter has been the study of franchises. Long ago Henry Jenkins coined the term acafan, defined as someone who is a fan of what he or she studies but also produces academically solid publications on it. His Textual Poachers (1992, second edition 2012) became a classic in the study of fandoms. His Convergence Culture (2008) examined the relationship between fandoms and film, television, and other media franchises.

Henry studied under David here at the university. I think it’s safe to say that David was also an acafan when he wrote about Asian action cinema in Planet Hong Kong (2000, second edition 2011, available as a PDF here). I, too, admitted to being an acafan when I wrote my study of Peter Jackson’s (or should I say New Line’s) Lord of the Rings films in The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (2007).

In 2016 I took a look at the continuation of the LOTR franchise, which was still going strong then and is still going strong now. No doubt next year, when we reach the twenty-fifth anniversary of the release of The Fellowship in the Ring, there will be considerable exploitation of re-releases and yet more licensed products.

More recently Colin Burnett, another of David’s students, known for his study of Robert Bresson, has turned his enthusiasm for the James Bond franchise into a research project. I am happy to see him discovering shifts in control of the film and merchandising rights that somewhat parallel those in the LOTR franchise, most notably with Amazon’s ambitious prequel series, The Rings of Power. Thanks to Colin for contributing an entry dissecting and clarifying the recent Variety article announcing Amazon MGM’s acquisition of the Bond film franchise.

Amazon Doesn’t Own James Bond–Yet

In a development that has shocked the entertainment industry, Amazon MGM announced on February 20, 2025 that it had taken over “creative control” of the James Bond film franchise. What exactly does this mean, and why is it so shocking?

Reporting on the news has tended to overlook some crucial details about the structure of the Bond franchise, a factor which in turn has colored the speculations of commentators and fans. Variety’s February 20 headline, for instance, alleges that “Amazon MGM gains creative control of 007 franchise.” This simply isn’t the case.

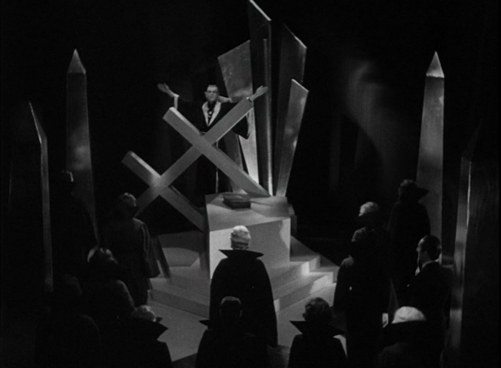

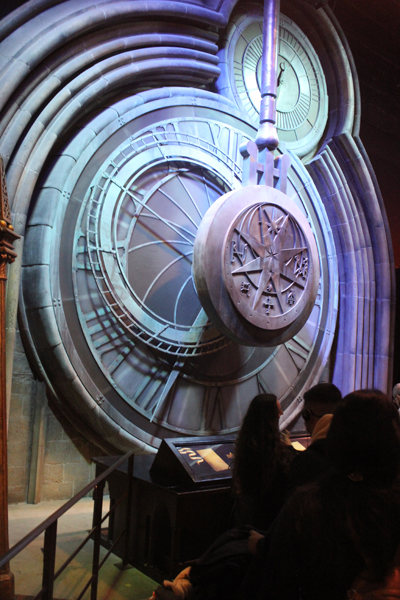

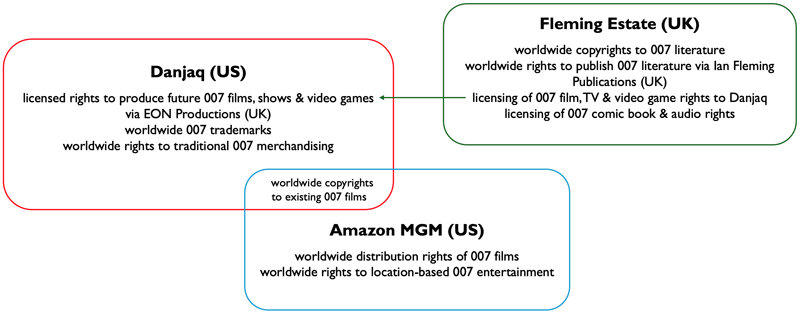

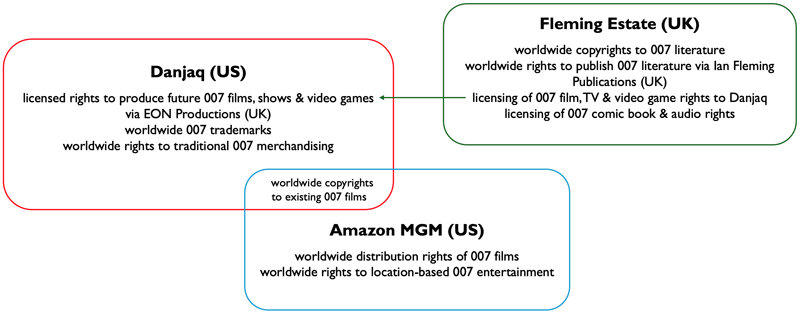

The Bond franchise is configured as a shared rights and licensing network (above). For decades, even prior to Amazon’s acquisition of the studio in 2022, MGM has owned the worldwide distribution rights of the Bond films, as well as shared copyrights for the existing Bond film titles. The new pact, which some price at $1 billion (unconfirmed), gives Amazon MGM the power to manage the artistic direction of the film series for the first time, and thus presumably a controlling stake in a company called Danjaq.

How did we get here?

Danjaq/EON Productions’s shifting media franchising strategy

Until now, production of the film series has been in the able hands of the Broccoli family. In 1961, producers Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli and Harry Saltzman optioned Ian Fleming’s novels and formed Danjaq, a rights holding firm initially based in Switzerland (now in the US). To produce their Bond film series, Broccoli and Saltzman acquired the small British production company EON Productions, allowing them to benefit from British tax breaks and subsidies. They also formed a partnership with Hollywood studio United Artists (UA) to finance and distribute their projects. Over the years, there have been changes here and there—MGM acquired UA in 1981, and Broccoli’s stepson Michael G. Wilson and daughter Barbara Broccoli took the reins of EON/Danjaq in 1995—but the EON/MGM arrangement has remained relatively stable.

The decades-long partnership between EON and MGM has always favored the Broccolis. Through EON, they shaped the creative direction for the series, and through Danjaq, the Broccolis managed the copyrights for the cinematic Bond and the global Bond trademarks. But when the multinational technology company Amazon purchased MGM in March 2022, it acquired considerable leverage in the Bond franchise. Almost immediately, tensions began to surface between EON and MGM. The longtime partners couldn’t agree on the next steps for the series.

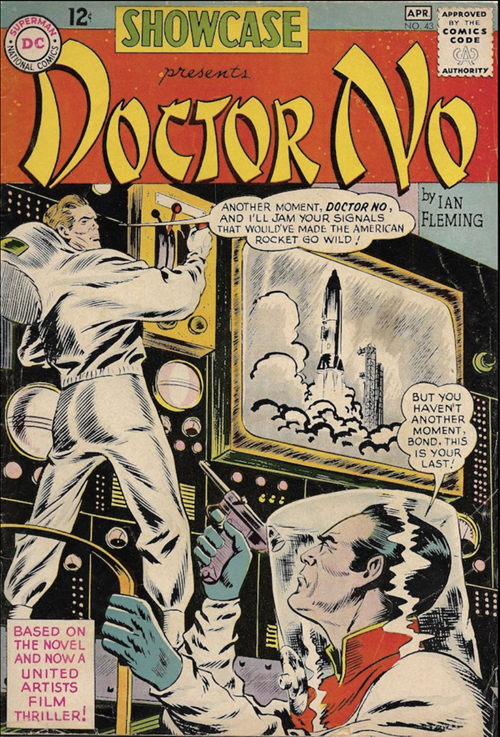

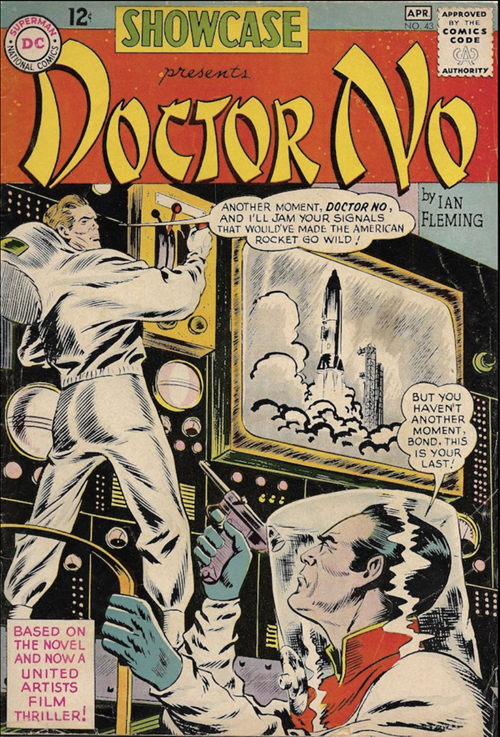

Reports indicate that Amazon MGM was intrigued by the possibility of a James Bond Universe akin to Disney’s Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars Universe. The concept is not a foreign one to Bond producers. Between 1961 and 2002, EON worked with partners in numerous popular media to spread the Bond story throughout the market. They licensed publishers DC, Dell, Marvel, and Topps comics to adapt their films into comic books, such as the 1962 DC Showcase 32-page comic book adaptation of the film Dr. No.

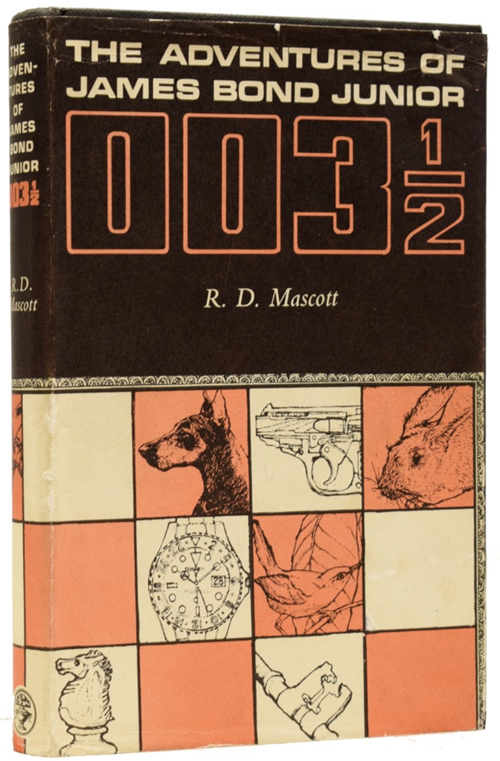

In the 1960s, they showed interest in a children’s TV series based on the 1967 novel The Adventures of James Bond Junior 003 ½ , published by Ian Fleming publisher Jonathan Cape. The concept came to fruition with the syndicated show James Bond Jr. (1991-1992).

In the early 2000s, they started development on a spinoff film titled “Jinx,” based on the Halle Barry character from the 2002 film Die Another Day. And for decades, EON has worked with video game designers to create interactive adventures, the most famous being GoldenEye 007 (1997) for the Nintendo 64 system. In fact, there’s a new EON-licensed game in the works.

In recent years, EON has devoted most of its resources to the films, whose productions became more ambitious. Perhaps sensing Bond’s uniqueness in the market, where franchises saturate consumers with content—Marvel and Alien movies and streaming series, Star Trek shows, Star Wars games, Avatar comics, etc.—EON opted for a more restrained approach that focused on films, creating the impression that they were “specials” and avoiding product overexposure. There have been exceptions. When the Daniel Craig era came to an end with 2021’s No Time to Die, EON signed with Amazon Prime—prior to the Amazon’s acquisition of MGM—to partner on the reality show 007’s Road to a Million. The series required little creative investment on Wilson’s and Broccoli’s part, and Bond doesn’t appear in the show, protecting EON’s most valuable commodity.

Amazon MGM’s notion of a cross-media Bond Universe simply didn’t appeal to EON, and the development of a series to follow the Craig films stalled. Exacerbating the situation, reports are that EON was flummoxed about how to relaunch the films after the creative and financial triumphs of the Craig era.

Why did EON step away?

Commentators have alleged that these creative impasses placed pressure on Wilson and Broccoli to sell their creative stake in the film series. But other developments suggest that the picture is more complicated.

Media franchises like Bond, the Lord of the Rings, Oz, and Marvel are all about rights. In recent weeks, peculiar news has surfaced in The Guardian (UK) about an Austrian-born developer named Josef Kleindienst, owner of a luxury property empire in Dubai, filing a number of “cancellation actions based on non-use” in UK and European courts. His ambition is to claim ownership of a broad swathe of Bond trademarks. These trademarks—for such items as computer programs, electronic comic books, electronic publishing and design—have not been used for a period of five years. Kleindienst is alleging that Danjaq’s trademarks for “James Bond Special Agent 007,” “James Bond 007,” “James Bond,” “James Bond: World of Espionage,” and the expression “Bond, James Bond” are subject to challenge.

These legal challenges, assuming they have standing, would have placed EON/Danjaq in the difficult position of having to battle a well-resourced foe in court or to quickly roll out product to renew their trademarks. A loss of even some of these trademarks could be devastating for the franchise. Acquiring the trademarks would not be easy, but were Kleindienst to succeed, he could at least in theory challenge or seek compensation from the production and release of any product seeking to use the James Bond name. Perhaps Wilson and Broccoli elected to sell their controlling stakes in Bond to avoid a protracted legal battle. Perhaps, too, the multi-billion-dollar firm Amazon MGM stepped in, and agreed as part of the deal to fight these impending trademark challenges to keep all Bond rights under the EON-MGM tent.

If such speculation has merit, then Wilson and Broccoli ceded creative control because it was their only major bargaining chip with Amazon MGM. The deal would ensure their continued roles as stewards of their portion of the Bond rights. After all, even EON/Danjaq doesn’t own all of the Bond intellectual property. The literary, audio, and comics rights are retained by the Ian Fleming Estate and managed by the firm of Ian Fleming Publications (IFP). In a statement issued on its website, IFP addressed the Amazon MGM deal, acknowledging Wilson and Broccoli “for their remarkable stewardship and vision. Their imagining of James Bond on screen has created one of the world’s great film franchises and has led the incredible success of the British film industry.”

What lies ahead for 007?

Here too there’s much speculation. Most fans of the film series seem skeptical about the new Amazon MGM era, concerned that Bond will become just another media franchise. An Ellis Rosen New Yorker cartoon captures the general mood, showing Jeff Bezos—in the guise of Bond villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld—standing over a bound James Bond who lays prone under the Amazon Swoosh symbol in a position reminiscent of the famous laser-torture sequence from 1964’s Goldfinger. In the original, Sean Connery’s Bond says to rival Auric Goldfinger, “You expect me talk?” Goldfinger’s answer is iconic—“No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!” In the New Yorker version, Bezos responds, “No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to star in a series of increasingly bland spinoffs and TV shows that have significant viewership decline after the first episode.”

One thing’s for certain: Bond has entered the “content” era. The film franchise will no longer focus on films alone. Given its extraordinary resources, Amazon MGM may even make a bid for all Bond rights, including a buyout of IFP, bringing the Bond property under one rights-holding company for the first time since the 1950s.

In the meantime, will Amazon MGM respect the Bond film property? Will it treat the replacement of Craig with the same care EON addressed the “new Bond” question in the past? Will it pursue EON’s commitment since the onset of the Craig era to “quality” blockbuster production, with an emphasis on location shooting, practical effects, and adherence to the spirit, if not the letter, of the Fleming version of the character? I have reasons to doubt some of this.

Among other concerns, the copyrights to Ian Fleming’s original Bond stories expire in the UK in 2034, a date that marks 70th anniversary of the author’s death (Fleming’s works are already in the public domain in Canada.)

Amazon MGM has just under a decade to exploit the Bond film rights before competitors are legally able to launch their own adaptations of Fleming’s 007. We can expect more studio-bound, computer-generated (CG) productions, which is more efficient than the location-based approach of EON and today drives most major franchise filmmaking. We can also expect streaming series: a Felix Leiter series, a Moneypenny series, or perhaps a Lashana Lynch 007 series or a Jinx series. Perhaps we can expect Amazon MGM to option a number of the “Bond Continuation” novels released by IFP since Ian Fleming’s death in 1964. Most assuredly, we can expect a “mothership” theatrical series with a new Bond, and even a revival of the James Bond Jr. animated series, for which some fans are nostalgic. Amazon MGM will do many of the things EON/Danjaq did or had hoped to do in the past but didn’t have the resources or bandwidth to do in recent decades.

We can expect, in short, what we’ve come to expect, over and over again. A new Bond era.

For more on EON Productions and its reliance on British film subsidies, see pages 41-42 and 55-56 of James Chapman’s Dr. No: The First James Bond Film (New York: Wallflower Press, 2022). See also Charles Drazin, A Bond for Bond: Film Finances and Dr. No (London: Film Finances, Ltd., 2011).

For a detailed account of the original deal between EON and UA/MGM, see chapter eight of Tino Balio’s United Artists, The Company that Changed the Film Industry, Volume 2, 1951-1978 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987).

Colin Burnett is Program Director and Associate Professor in the Film & Media Studies Program at Washington University in St. Louis. He is the author of two books, including one on the major French director Robert Bresson. He has written an article on storytelling in the James Bond film series for the Journal of Narrative Theory and is completing a new book entitled Serial Bonds: The Shape of 007 Stories.

Posted in Film Franchises, Hollywood: The business |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Amazon Doesn’t Own James Bond—Yet: Making Sense of the 007 Franchise. A guest post by Colin Burnett open printable version

| Comments Off on Amazon Doesn’t Own James Bond—Yet: Making Sense of the 007 Franchise. A guest post by Colin Burnett

Thursday | January 23, 2025

I dimly remember hearing in late 2020 that the sequel to Moana (2016) was going to be Moana: The Series, streaming on Disney+ rather than a theatrical feature. David and I liked Moana very much, but in those of Covid and non-theater-going, it seemed a minor thing. A series wasn’t appealing, and we could just ignore it. Then about a year ago it was re-announced as a theatrical feature. I just assumed that the powers-that-be had simply decided that what was by that time being called Moana 2 would make more money by being released “Only in theaters,” as the posters inevitably pointed out.

That was true, but there’s much more lurking behind such a decision. Straight to streaming or released to theaters first? has become a puzzling question for studios as they discover that the huge profits they assumed their new streaming services would bring in were not all that huge or maybe not profits at all.

I am delighted to have two experts, Nicholas Benson and Zachary Zahos, who follow the distribution strategies of the film industry, contribute a guest post on how Moana 2’s change from modest Disney+ series to a box-office hit creeping up on the total domestic gross of Wicked reflects major shifts in the industry’s decisions about releasing options.

Nicholas Benson received his Ph.D. in Media and Cultural Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is now an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and Media at SUNY Oneonta. His current work considers the intersection of discourses of storytelling and management within franchise production cultures. Zachary Zahos also received his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is currently serving as Public History Fellow at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Back in September Zach and Matt St. John contributed a entry to this blog, examining a claim that movie lovers had stopped going to theaters.

Thank you, Nick and Zach, for your contribution to our understanding of the current tangled distribution systems of the current industry! Over to you.

The curse has been lifted—at Walt Disney Pictures.

After a run of box-office bombs, Disney’s flagship film studios bounced back in 2024: Pixar with Inside Out 2, 2024’s top-grossing film, and Walt Disney Animation Studios with Moana 2, which just cleared $1 billion globally. Even Mufasa: The Lion King, a CGI prequel produced by Disney’s live-action division, looks destined to overcome a weak start to become a profitable “sleeper hit.”

The cynical read on all this is that Disney, to quote The Town’s Matt Belloni, “engineered” a surefire 2024 by pushing riskier bets, such as Pixar’s Elio and the Snow White remake, to this calendar year. But, at the end of the day, adaptive engineering, risk mitigation, studio chicanery, whatever you call it—this is how Hollywood lives to tell another tale, and you need not look further than Moana 2 for a revealing case of Disney executives reading the horizon and changing course.

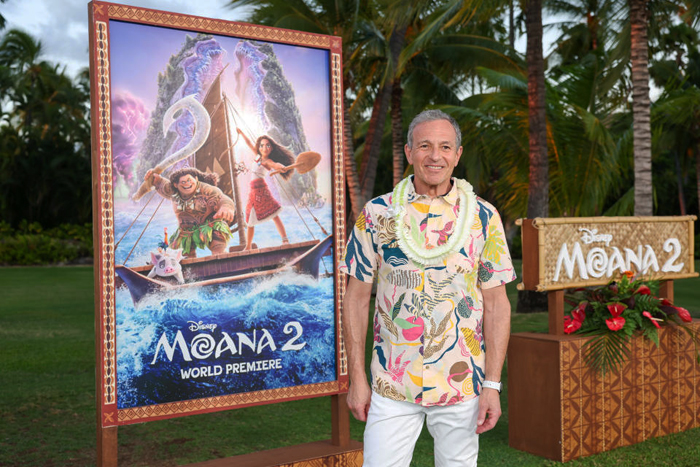

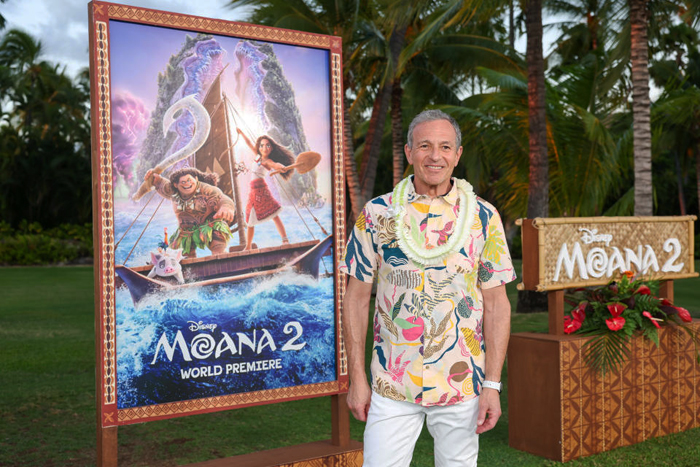

Moana 2’s present status, as a resounding theatrical success, interests us in particular due to the roundabout journey—and P.R. spin—it took to get here. For those unaware, the film now playing in multiplexes called Moana 2 was greenlit in 2020 as a television series (titled Moana: The Series) for the company’s streaming platform Disney+. It was only last February when CEO Bob Iger announced that this project was instead heading to theaters under the new title Moana 2. While the trades were quick to discuss the financial calculus behind such a shift (per Deadline: “after misfires … more Moana is a safe bet for the House of Mouse”), Disney has been careful to publicly attribute this decision to creative, rather than business-minded, imperatives. For instance, Jennifer Lee, former CCO at Disney Animation, told Entertainment Weekly in September:

We constantly screen [our projects], even in drawing [phase] with sketches. It was getting bigger and bigger and more epic, and we really wanted to see it on the big screen. It creatively evolved, and it felt like an organic thing.

As genuine as this sentiment might be, we sincerely doubt that Moana 2’s last-minute about-face, from streaming series to theatrical film, emerged from creative disagreements alone. The film industry has changed rapidly over the last five years—streaming has undergone its own boom and bust cycle during this time, with vintage concepts like advertising, bundling, and return-on-investment, bringing Hollywood executives down to earth. In short, the Walt Disney Company that announced Moana: The Series in 2020 is different from the one that released Moana 2 in theaters last month.

Longtime readers will recall this blog’s fondness for the first film, as shared by David, Kristin, and Jeff Smith. We count ourselves Moana fans, as well, while also agreeing with critical consensus that Moana 2 lacks the inspiration (or songs) of the original.

But what follows is not a review. While we will make reference to certain storytelling choices present in the film, our main goal here is to argue that Moana 2—or, more specifically, the production and circulation context surrounding it—is symptomatic of a global industry in flux. As the world’s largest legacy entertainment company, Disney is not one to buck trends but rather to reinforce them. An engaged analysis of Disney’s recent executive-level decisions offers us a chance to gauge which way the winds of commerce are blowing.

Yet the company’s sheer scope, both internally and across its multi-generational audiences, invariably creates sites of tension and contest. We see that in Jennifer Lee’s public assurances concerning Disney’s creative community, and not its C-suite, steered Moana 2 into theaters. But we also see such tension and contest in how Moana 2’s production history throws long-standing hierarchies at the Walt Disney Company into relief. As a result of Disney+ and recent executive initiatives which we will delve into here, the line separating the company’s film and television output has become increasingly blurred, as have the rules for successfully exploiting marquee franchises, particularly those geared toward younger audiences.

What is clear to us is that, even in success, Disney+ has failed to solve all of its parent company’s problems and in the process has created several new ones. This is not simply because of profit margins, but also because such investments, from both studio and audience, run downstream from discursive categories like “film,” “television,” and “streaming.”

In the case of Moana 2, the shift of Disney’s prized sequel from the “streaming television” to the “theatrical film” column, months out from release, occurred in large part due to the promise of greater financial returns. That much seems obvious, no matter what Jennifer Lee and other creative executives say, given how most studios across the industry have learned to love movie theaters again.

But we do not wish to suggest these leaders are lying through their teeth, either. As strategic as Lee’s statement to Entertainment Weekly may have been, she does seem to genuinely represent the values and norms of the world’s most famous animated film studio. Where else but movie theaters do you go when you design your expensive franchise sequel to be “bigger and more epic”? So, while Moana 2 sailed back to multiplexes amidst an industry-wide correction away from pyrrhic victories in streaming, its journey looks especially inevitable if you account for the particular industrial apparatus from which the film came.

We’ll expand on these ideas by teasing out a few historical threads relevant to Moana 2’s production. These concern Disney+, Disney Animation Studios, and the Walt Disney Company, as well as the latter’s general playbook toward franchising animated entertainment.

Disney+ and the business of animation today

Disney’s recent theatrical rebound is notable given the obstacles—some of them industry-wide, others self-inflicted—its film division has faced since its peak in 2019. That year, Walt Disney Studios reported $11.1 billion in worldwide theatrical revenue, with a record seven films (among them the animated sequels Toy Story 4 and Frozen II) each surpassing $1 billion at the global box office. In November of 2019, the company launched its Disney+ streaming platform. While it always seemed destined to succeed, Disney+ exploded in growth months later as the COVID pandemic closed theaters and Disney’s theme parks.

Since that high-water mark, Disney’s films have struggled, partially due to counterproductive distribution decisions and a streaming-focused production pipeline. On the distribution side, during the pandemic then-CEO Bob Chapek (above) launched Disney+’s day-and-date “Premier Access” program and arranged for Pixar’s latest films, beginning with Soul (2020), to skip theaters and instead premiere on the streaming platform. While this strategy fueled subscriber growth, almost every animated film Disney released to theaters in its wake, most notably Lightyear (2022) and Strange World (2022), underperformed at the box office. Analysts have attributed this cold streak to a range of causes, including the notion that Disney’s streaming release strategy had “conditioned audiences” to wait for theatrical releases to hit streaming.

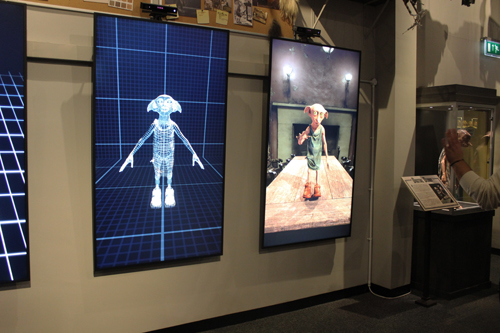

Much ink has already been spilled on another contributing pop psychology phenomenon, that of “franchise fatigue.” The idea that audiences are burned out by the proliferation and interconnectedness of so much franchise material may not be neatly supported by the data. The top 10 movies of 2024 were all franchise properties, after all. It is a more credible notion if one examines Disney’s many spin-offs on streaming. Since 2019, the company’s marquee film production companies, among them LucasFilm and Marvel Studios, have shifted resources to producing long-form television series for Disney+. LucasFilm and Marvel respectively launched their Disney+ slates with The Mandalorian and WandaVision, both of which were well received and highly rated. But ever since, Disney’s streaming series have attracted increasingly mixed critical responses (even after controlling for toxic fan reactions) and diminishing viewership numbers (here and here).

That does not mean all Disney+ originals are destined for failure. What seems increasingly clear is that certain forms of programming, such as animation, perform more consistently, albeit under a typically lower ceiling of viewership. In October, The Hollywood Reporter published a 3000+ word article headlined, “Is Disney Bad at Star Wars? An Analysis.” To be clear, the piece answers its core question with, “On balance, no.” Nevertheless, this article is relevant to this discussion in that it contrasts the strong ratings of the Star Wars animated series on Disney+ with the franchise’s live-action series for the same platform. New animated series like The Bad Batch have more than earned their keep, with their large volume of episodes (usually 16 per season vs. 8 for live-action series) driving viewer engagement at a fraction of the cost of their recent live-action counterparts.

So, Disney+ is a sensible launching pad for new animated Star Wars series. Does that make it also wise to premiere the latest Disney Princess tale on the same platform? (Despite Moana 2’s “Still not a princess!” joke, in the eyes of Disney, she officially is one, as the Princesses scene in Ralph Breaks the Internet, below, demonstrates.) Well, that depends.

Traditionally, Disney has had three main paths for exploiting animated franchise content: theatrical distribution, commercial television, and direct-to-video (DTV). Each of these had clear advantages and disadvantages, and for many years these three paths looked fairly straightforward. Theatrical distribution, both then and now, is prestigious and visible to a large, diverse audience, and it comes with the potential for massive global box office revenues and merchandising opportunities which can immediately counteract the large budget.

The other two categories—commercial television and DTV—were lucrative paths for many years at the Walt Disney Company, but under the Disney+ paradigm have begun to appear less distinct from the theatrical option. Commercial television traditionally came with less expectation that it feel cinematic, and therefore could be made on a smaller budget. Television series promise a smaller, more concentrated audience of children or existing fans and a long tail financial model that relies on revenue generated through ad support and future syndication possibilities. DTV content, for its part, follows a similar model to commercial television but at an even lower scale of cost, with accordingly lower (but faster) profit potential.

The visibility of commercial television content within the Disney animated fold is moderate (and outright low for DTV). Millions of children apparently watched the Tangled (2010) spin-off Rapunzel’s Tangled Adventures, which was produced by Disney Television Animation and aired from 2017 to 2020 on the Disney Channel. We don’t expect you, reader, to have heard of this show, though at the same time we would be surprised if you never before heard of Tangled. Thus, even resounding successes of this type will remain off the radar of the general, adult-aged public, and so commercial television spin-offs, even if not the highest quality, will not inherently hurt the brand as a large film can.

It’s on this last point, regarding visibility, where the project formerly known as Moana: The Series was always destined to be different. With the company’s flagship studio, Disney Animation Studios, producing it, the budget leaped beyond any animated project Disney produced before for television or DTV. Launching Moana: The Series exclusively on Disney+ had potential upside, but as we will see, these benefits began to look questionable.

Moana’s voyage toward streaming…

Moana: The Series was first announced, by Jennifer Lee, at the virtual Disney Investor Day event in December 2020. The broader theme of the investor’s day was Disney’s new structure, which separated content creation from distribution in a bid to turn to what newly appointed CEO Bob Chapek referred to as a “DTC [direct-to-consumer] first business model.” The Moana series thus joined a slate of other Disney+ releases, including day-and-date release movies like Raya and the Last Dragon (2021), Marvel series such as Loki (2021-2023), and limited series such as WandaVision (2021). Though executives continued to gesture towards the importance of “legacy distribution platforms,” such as theatrical and linear television, the focus was on the corporation’s investment in Disney+. As Chapek put it in his opening statement:

We knew this one-of-a-kind service featuring content only Disney can create would resonate with consumers and stand out in the marketplace and needless to say Disney+ has exceeded our wildest expectations.

The idea to expand the Moana franchise into a series, therefore, was a direct result of corporate confidence in DTC platforms as the future of distribution. Chapek’s new corporate structure promised a streamlined production pipeline that seemed to completely separate the creation and production process from the distribution process — in other words, creatives would generate content and then the distribution team would figure out the best way to get that content to the consumer. Chapek explained the structure in a statement:

Managing content creation distinct from distribution will allow us to be more effective and nimble in making the content consumers want most, delivered in the way they prefer to consume it. Our creative teams will concentrate on what they do best—making world-class, franchise-based content—while our newly centralized global distribution team will focus on delivering and monetizing that content in the most optimal way across all platforms, including Disney+, Hulu, ESPN+ and the coming Star international streaming service.

This new agnostic approach to distribution seemed to lead to a general confusion about how to staff DTC productions. The Moana follow-up presented a mixed bag in terms of who was brought back from the original production. Voice talent Dayne Johnson and Auliʻi Cravalho respectively reprised their roles as Maui and Moana. However, original Moana directors Ron Clements and John Musker were absent. Instead, Jason Hand, Dana Ledoux Miller and David G. Derrick Jr. (above) were hired to co-direct and run the series. Hand, who had the most experience working with Disney animation of the three, started his career at Disney in 2005, as a layout artist on the DTV sequels Tarzan 2: The Legend Begins and Lilo & Stitch 2: Stitch Has a Glitch. Disney has a well-known apprenticeship program and tends to hire and promote from within, so it’s not out of the ordinary that a series like this would be given to greener talent looking to gain experience.

That said, Moana: The Series’s production team was indicative of a broader ambivalence the company seemed to have about how much to invest in, and therefore how to staff, DTC content. While the series Baymax! (2022) brought in Big Hero 6 (2014) director Don Hall as showrunner, other series like Zootopia+ (2022) and the upcoming Tiana (2025) did not bring back the same directing or writing teams from the original films. Instead, Zootopia+ was directed by Trent Correy and Josie Trinidad, who previously worked in the Animation and Story departments on Zootopia, respectively. Tiana is reportedly being run by Joyce Sherri, who served as staff writer for the Netflix miniseries Midnight Mass (2021).

…and back to the multiplex

News on the Moana series remained sparse from 2020 until February 2024, when Bob Iger announced during a CNBC interview that the series would now be a theatrical feature slated for a fall 2024 release. The news came shortly before a Q1 earning call where he assured shareholders that “the stage is now set for significant growth and success, including ample opportunity to increase shareholder returns as our earnings and free cash flow continue to grow.”

Iger’s assurance came on the heels of a tumultuous few years for Disney, after a series of box-office failures and an internal struggle for power that resulted in the ousting of CEO Bob Chapek and a return to the post for Iger. While the issues faced by Disney were multifaceted, the all-in approach to DTC content was central to the company’s financial struggles. Subscriber fees could only generate so much revenue, and that revenue didn’t seem enough to sustain the enormous content library required to maintain a streaming platform. In September of 2022, Bob Chapek indicated to Hollywood Reporter that Disney+ had a content problem. As Chapek put it:

It’s important to go back to when Disney+ was launched and what the hypothesis was about how much food you had to give that system for it to truly maximize its potential, and I would say we dramatically underestimated the hungry beast and how much content it needed to be fed.

The extent of this issue became apparent during a 2023 lawsuit against Disney by investors alleging Disney hid the actual costs of running the service to offer the appearance of profit potential. Though the service is reportedly now profitable, since its inception Disney+ has racked up over 11 billion dollars in losses, showing that the DTC, subscription-based model has not been the massive success it was predicted to be in 2020.

In late 2024, as the premiere for the re-titled Moana 2 approached, those who worked on it related to press outlets various versions of how the series abruptly shifted to a theatrical film. We can return to that September Entertainment Weekly profile to see a few explanations side-by-side. For instance, co-director David G. Derrick Jr. described the decision to pivot from a series to a feature film as a moment of “mutual realization” between the studio’s various teams:

It became apparent very early on that this wanted to be on the big screen. It felt like a groundswell within the whole studio.

Co-director Dana Ledoux Miller framed it as a push from the creatives, out of a desire to showcase their work. She suggested the project had “the best artists in the world” and added:

Why are we not letting them shine on the biggest screen in the biggest way?

This rhetoric stood in sharp contrast to Chapek’s 2020 Investor Day video, in which he seemed to downplay the importance of theatrical distribution in favor of the convenience of DTC exhibition. At that point, there was no sense that artists would feel minimized by having their work showcased on DTC platforms. Instead, these new comments by the creative team touted theatrical exhibition as a prestigious honor and the only way to showcase quality artistic achievement.

In other words, after years of the studio relegating several projects to Disney+ or day-and-date releases, Moana 2’s pivot feels like a pointed reinvestment in the theatrical experience. Jennifer Lee reinforced this perspective when she said to Entertainment Weekly:

Supporting the theaters is something that we talked about. … We love Disney+, but it will go there eventually. You could really put it anywhere, but these artists create stories that they want to see on the big screen and that we want the world to see on the big screen.

When the show was reworked as a movie, the absence of certain high-profile talent associated with the first Moana—especially popular songwriter Lin-Manual Miranda—became apparent. The official reason for Miranda’s absence was that he was already committed to another Disney theatrical project, Mufasa: The Lion King (2024). While Moana composers Mark Mancina and Opetaia Foa’i did return to score the movie, the new songs for the sequel were primarily composed by Abigail Barlow and Emily Bear. The two were, as Billboard put it, “the youngest (and only all-women) songwriting duo to create a full soundtrack for a Disney animated film.” Until that point their only real credit was writing an unsanctioned viral musical based on the Netflix show Bridgerton (2020 – ). Though having young women write the music for a musical about young women was a positive move for Disney, the pair’s relative inexperience became more conspicuous when the Disney+ show was transformed into a tentpole feature film. In its review of the film, The Hollywood Reporter noted that “Miranda’s absence is unfortunately felt” throughout the musical numbers. Variety, more pointedly, called the new batch of songs, “imitation-Lin-Manual knockoffs.”

The lack of personnel continuity between Moana and Moana 2 highlights the general disorganization within Disney’s new corporate structure. Despite the claim that content can be created and then distributed wherever by reading the will of the data gods, the reality is projects still seem to work best when the venue of the exhibition is known during the early stages of production. When Disney has done theatrical sequels they tend to staff them with creative talent from the original. Jennifer Lee oversaw the creation of Frozen 2 (2019), Andrew Stanton returned for Finding Dory (2016), and Pete Doctor directed Inside Out 2 (2024). Though Miranda claims he was otherwise preoccupied, one wonders if he would have still worked on Mufasa: The Lion King had he known the Moana follow-up was destined for a theatrical release.

While this is primarily an industry analysis, even a cursory look at Moana 2’s narrative reveals the editorial marks left by this unusual production. As with the first film, the sequel tasks Moana with breaking an ancient curse, except this one was set by a storm god named Nalo, who drove the different peoples of Polynesia apart. With this clear objective, Moana remains a classical, goal-oriented protagonist, but the seams begin to show once you look at the other characters. Curiously, Nalo remains an off-screen antagonist, who is not properly introduced until a mid-credits scene that mimics Thanos’s first appearance in The Avengers (2011). The journey is also now populated by a group of secondary characters easily identified by a defining trait (e.g., Moni is a huge Maui fanboy). The first act, set on Moana’s well-populated island of Motunui, feels especially abridged from the project’s looser, episodic origins, and the onslaught of new characters leaves little room for the emotional depth and character development that many critics respect about the first film (here and here).

The seams where Moana: The Series was stitched together into Moana 2 are not only evident in the story, but in the production and promotion as well. Being forced into the throes of a giant A-list press junket was probably not what these first time directors signed up for; it’s certainly something the team behind the direct-to-video Cinderella II: Dreams Come True (2002) never had to deal with, and for good reason.

Yet Moana 2’s directors were left answering questions about decisions made in the first movie they had little or no control over. For example, the cute pig Pua, whom fans felt was underused in the original movie, took on a more prominent role in the sequel. When asked by CinemaBlend if they responded to any feedback about the first film, director/writer Dana Ledoux Miller responded:

Look, people really wanted Pua in that first movie on the canoe. I wasn’t around, but we put Pua on the canoe now.

While not overly awkward, the exchange highlights the behind-the-scenes break in continuity. Similarly, young songwriters who should be establishing their own identity were instead having their work compared to the beloved music of Lin-Manuel Miranda. Ultimately, while this has financially paid off for Disney, Moana 2 was clearly a ship built for the smaller more secluded waters of Disney+. Though it has survived, the tepid reviews suggest it may have been only by the skin of its teeth.

Riding the popcorn-bucket wave

Moana 2 is not only indicative of the pitfalls of the DTC model but highlights the inherent potential of theatrical distribution, especially for franchised content. Despite lukewarm reviews, the movie has already earned record numbers at the box office. More importantly, it has reignited interest in the brand more broadly. Moana became the latest entry in a list of high-profile collectors’ popcorn buckets distributed by theaters (above).

While they might seem like a gimmick, these popcorn buckets have become an integral aspect of the theatrical distribution model and the “post-pandemic ‘identification’ of moviegoing.” They  work in favor of both the theaters and the studios by raising awareness about the films and the brand. As one journalist pointed out, “I didn’t realize Despicable Me 4 was happening until I saw the popcorn bucket.” With the release of toy lines (Funko dolls aplenty, including Pua, above and left), popcorn buckets (and nacho boats!), and theme park tie-ins, the hype machine that spins around a massive theatrical release has become somewhat intuitive over the past century in a way that DTC models have difficulty emulating, even with the benefit of synergy within vertically integrated corporate structures. work in favor of both the theaters and the studios by raising awareness about the films and the brand. As one journalist pointed out, “I didn’t realize Despicable Me 4 was happening until I saw the popcorn bucket.” With the release of toy lines (Funko dolls aplenty, including Pua, above and left), popcorn buckets (and nacho boats!), and theme park tie-ins, the hype machine that spins around a massive theatrical release has become somewhat intuitive over the past century in a way that DTC models have difficulty emulating, even with the benefit of synergy within vertically integrated corporate structures.

Though box-office numbers are important, this hype is equally valuable. In this way, Moana 2 was a success even before it debuted. The trailer for Moana 2 broke the record for the most-watched trailer for a Disney movie ever, reaching over 178 million views in 24 hours. Likely not coincidentally, that trailer ended with an image of Maui holding Pua, announcing that this cute character was, as Miller had put it, “on the canoe” and (more importantly) ripe for new licensing deals. When Moana 2 was announced to be a movie, it kicked off one of the largest and most lucrative global merchandising campaigns in recent memory. Apart from Moana merchandise, there were brand partnerships with airlines to local Hawaiian food chains. Imagery flooded public spaces. Hasbro introduced cutting-edge 3D printing technology to inject toys and dolls as quickly as possible into the marketplace. This success, both in theaters and retail, suggests that even if somewhat clunky, the 11th-hour decision to turn a television show into a movie seems to have been financially prudent – at least in this instance.

New rules, some of them old

During Disney’s 2024 Q4 earnings call, Bob Iger admitted, seemingly unintentionally, the motivation for recent subscription price increases for Disney+. According to Iger, these streaming price hikes were designed less to generate revenue through subscriber fees and more to shift consumers to the ad-supported model:

It’s not just about raising pricing, it’s about moving consumers to the advertiser-supported side of the streaming platform. … The pricing that we recently put into place, which is increased pricing, was actually designed to move more people in the AVOD [advertising video-on-demand] direction because we know that the ARPU [average revenue per user] — and interest in it from advertisers in streaming — has grown.

Iger’s comments point to how these companies are starting to recognize (or grapple with) where the actual value of the streaming service lies within the broader corporate structure: specifically, how the streaming service functions, or serves, the vast media franchises these companies have restructured around. Until recently, executives imagined them as vertically integrated platforms that allowed corporations to get content directly to consumers without the need for middlemen (though, with the exception of Comcast, third-party telecom companies still control the actual distribution pipeline, complicating the notion that these are truly vertically integrated systems). As this system evolves to support ads, content will need to be capable of sustaining viewers over time and selling ad space to sponsors. In other words, despite all the obfuscation of what will likely amount to a transition period, streaming services seem destined to be mostly a different distribution platform for what had been commonly known for the past century simply as commercial television.

Despite some disruptions over the past several years, theatrical distribution continues to hold a privileged position in the cultural zeitgeist, especially for high-profile properties. Movies can air on TV, but the experience of watching them is still culturally different from that of watching something in a movie in the theater. The act of going to the movies is an event apart from one’s day-to-day life (one must schedule a movie, what David called “appointment viewing”), while television, regardless of its distribution mechanism, remains intertwined with the cadence of one’s daily routine.

Take, for example, a recent review of Mufasa: The Lion King (2024) in Polygon. Writer Petrana Raduloviv opines that the movie would have fared better as a video-on-demand release:

Mufasa: The Lion King, the 2024 movie about Simba’s majestic father, seems like it could exist right alongside Simba’s Pride, The Lion King 1 ½, and the animated TV show The Lion Guard. Except instead of being cheaply thrown together for young audiences, it was directed by Academy Award winner Barry Jenkins (Moonlight, The Underground Railroad), with a script from Catch Me If You Can screenwriter Jeff Nathanson, and music from Lin-Manuel Miranda.

In other words, the string of Lion King sequels might lead people to think that this latest one could be treated like the previous ones, being presented DTV. The celebrity talent involved, however, kindled enough interest to lure audiences into theaters and make Mufasa a hit.

Despite claims to the contrary, lines between various exhibition sites remain strong. DTV content and theatrical releases are seemingly different cultural categories that, in turn, invite different reading strategies. As the above quote suggests, success is, in part, based on expectations, and expectations tend to be tied directly to the site of the exhibition. As media conglomerates consolidate and organize transmedia franchises, they must negotiate the utility and corporate value of each exhibition site at their disposal. The task for media producers over the next few years is to calculate the financial value of these cultural categories and use that to calibrate the production costs of their various franchise proliferations. In short, this difference in cultural capital between these two exhibition sites constitutes a difference in industrial strategy as corporations seek to exploit and profit from their various properties in myriad ways. How this shakes out will have lasting effects on the future of film and television creation for decades.

Studios are grappling with these questions of medium-specificity, appropriate exhibition, and franchise management in real-time. New rules are being forged that will shape the future of distribution. As we see it, streaming is unlikely to collapse theatrical and television into a single system but instead offer a hybrid exhibition site that seems to fill the role of both commercial television and the direct-to-video market.

What complicates streaming currently is that it has traditionally been subscriber-supported and therefore followed a premium cable, rather than a commercial television, model of production (see Amanda D. Lotz for more on this distinction). Unlike the commercial television or direct-to-video route, where the value for those exhibition options was tied to their lower production costs, streaming tends to demand a similar quality production to film since it’s not really competing with broadcast television. Instead its rival is seemingly premium cable programming like Game of Thrones. Therefore, it’s very expensive, sometimes more expensive than film production.

Streaming tends to look for a larger audience and is not aimed at exploiting as much as expanding a story world as a franchise. This strategy may be something that fans of that particular story world want, but a general audience would rather watch individual stories than dive into an elaborate franchise saga. Streaming shows also tend not to consistently generate the same cultural impact as a theatrical release (is anyone talking about The Skeleton Crew?). In other words, as it exists, streaming offers the worst of all worlds for media conglomerates looking to exploit their intellectual properties in ways that generate revenue and help the brand. Shows are expensive to produce, they can generate bad press and harm the brand, but they have very little potential to generate large revenues.

We would argue that this is likely why Moana: The Series was reworked into Moana 2 and prepared for a theatrical run. Though the budget has not been officially revealed, based on industry sources, the budget was likely close to the $150 million budget of the first movie. In other words, it’s not because the story got “too big,” but because the budget was too big to justify it being tossed into the increasingly large pile of disposable Disney+ content.

Moana 2 is part of a clear trend. In 2023 The Mandalorian’s final season was transitioned from a Disney+ series to the upcoming theatrical release, The Mandalorian and Grogu (2026). Inside Out 2 (2024) enjoyed a successful box office run as a traditional Pixar theatrical release. A few months later, after the movie hit streaming services, the short, animated spin-off series Dream Productions (2024) debuted on Disney+. The four-episode limited series was produced on a severely reduced budget concurrently with the feature film production. However, mid-production Disney cut the episode order from seven to four.

When Moana: The Series was announced in 2020, Disney also announced a Tiana musical series based on the Princess and The Frog (2009). Though it was set to be released in 2023, it’s still in development – perhaps preparing to shift into a feature film. Disney has also systematically canceled or prepared to phase out many of its more expensive shows, even popular ones. Shows such as Ahsoka, Andor, and The Acolyte are all being canceled after one or two seasons. This suggests that Moana 2 did not evolve on a whim, but rather as part of a broader systematic move away from expensive Disney+ series and towards high-profile theatrical content. As Disney builds its advertising infrastructure, we’ll likely see Disney+ pursue things like Young Jedi Adventures (2023): franchise spin-offs aimed at families and children that are relatively cheap to produce and have syndication potential.

Yet Moana 2 also highlights a unique value of streaming over other forms of exhibition: data. Moana (2016) was the most streamed movie of 2023. Because of this, Disney knew that Moana (2016) was popular among their fanbase. This likely gave Iger and others some confidence that even without the A-list creative talent behind the scenes, the property alone could carry a sequel to a box office win, which in turn results in positive press and better stock performance. Similarly, the popularity of The Mandalorian (2019 -) as the second most streamed series on Disney+, behind only The Simpsons, likely factored into the choice to greenlight The Mandalorian and Grogu (2026) for theatrical release. We would likewise guess that the greenlighting of Frozen 3 and Zootopia 2 was likely less about some burning creative need to expand those stories and more about promising Disney+ data.

The decision to release the Moana sequel in theaters also reflects the obvious point that theatrical movies generate a higher profile than DTV series. Once they end their theatrical runs and are offered on streaming services, the desire to see them may lead to new subscribers.

Ultimately, what we see is not the erasure of one form of exhibition in favor of streaming, or competition between theaters, television, and streaming services, but the formation of a nascent symbiosis between these sites, as media conglomerates consider their place within each corporate enterprise.

Our gratitude to Matt St. John for inspiring and improving this piece.

We would also like to thank Kristin for her edits and insights on contemporary animation.

Relevant to this discussion is a newly filed lawsuit suing Disney for copyright infringement over the Moana franchise. Entertainment Weekly broke this news on January 12, and it goes without saying that we will follow this case as it proceeds.

Posted in Animation, Film industry, Hollywood: The business, Streaming |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Moana’s roundabout voyage back to the multiplex: A guest post by Nicholas Benson and Zachary Zahos open printable version

| Comments Off on Moana’s roundabout voyage back to the multiplex: A guest post by Nicholas Benson and Zachary Zahos

Saturday | January 11, 2025

Story of Floating Weeds (Yasujiro Ozu)

Kristin here:

This surprisingly popular series started with what we assumed to be a one-off entry. In 2007 David and I saluted the birth of the Classical Hollywood Cinema in 1917 as a full-fledged new set of norms that would last until the present day and influence filmmakers around the world. Introducing the list of ten films from ninety years earlier (for the list, click on the 1917 link below), David wrote:

This is the season when everybody makes a list of best pictures. We have stopped playing that game. For one thing, we haven’t seen all the films that deserve to be included. For another, the excellence of a film often dawns gradually, after you’ve had years to reflect on it. And critical tastes are as shifting as the sirocco. Never forget that in 1965 the Cannes palme d’or was won by The Knack . . . and How to Get It.

Still, enough time has elapsed to make us feel confident of this, our list of the best (surviving) films of 1917, both US and “foreign-language.”

That notion of time elapsing became the somewhat risible rationale for our series: surely ninety years is enough that one can be confident in one’s choices of old films worth watching and rewatching.

David ended that first entry, “Next year, maybe we’ll draw up our list for 1918.” This is our eighteenth such list. I took the initiative to follow up and have written all the entries–consulting with David each time, of course. This is my first time without his advice, though I know there are films on this new list with which he would have heartily agreed, others that he would agree are important enough to include, and one or two that he would be dubious about.

Previous lists can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1932, and 1933.

As in the past, I begin the process of choosing the ten films to included thinking that this year will be the one where there are ten obvious choices. During the transition to sound, the pickings have sometimes been slim, and in recent years I have filled in with one or two films that don’t quite stand up to the others in the final list. I had high hopes for 1934, but again I have had trouble deciding on a film to fill the final slot. As the 1930s progress, I am confident that it will be considerably easier to think of titles to make the list. Renoir will enter the height of his career, Mizoguchi’s films start surviving, Ozu maintains his high level until the war intervenes, and so on.

L’Atalante (Jean Vigo)

L’Atalante is surely one of the first films one would think of when asked to name great classics from 1934. Vigo made a couple of shorts, but his high reputation is based on only two films, Zéro de conduite and this one. Zéro was on my 1933 list. It’s a strange combination of surrealism, slapstick, magical realism, and bitter satire.

L’Atalante is none of these, really, but instead a poetic romance played out on a canal barge, the name of which gives the film its title. It begins just after the wedding of a young village woman, Juliette, and Jean, the captain of the barge. As they walk proudly toward the canal, the villagers follow them, muttering their disapproval at Juliette’s decision to marry an outsider with a strange profession. The pair are clearly much in love, but things begin to go wrong as Juliette gets bored with the monotonous routine aboard the barge. Once they arrive in Paris, there are quarrels, especially when Juliette responds naively to a handsome peddler who flirts outrageously with her. Juliette leaves to see the city, but in a fit of unjustified jealousy, Jean casts off, leaving her behind. The pair grow increasingly sad at their parting.

This slim plot is delightfully padded by Michel Simon as the eccentric Père Jules, Jean’s only adult crew member on L’Atalante. He drifts among moods, being funny, poignant and slightly menacing by turns. The antiques and gewgaws that he has collected in his long career of sailing around the world provide the few somewhat surrealistic touches that are more prominent in Zéro de conduite. These range from a sinister mechanical puppet of a music conductor to the rostrum of a large sawfish fastened to the side of a bed.

As often has been the case with the films on these lists, in my graduate-student days I saw L’Atalante in a low-contrast 16mm print. The restored version available on The Criterion Channel and in the Criterion Collection’s Blu-ray of Vigo’s complete oeuvre is a huge improvement.

Les Misérables (Raymond Bernard)

By contrast to Vigo, Raymond Bernard is not a name that comes readily to most people’s minds when one thinks of French cinema in the 1930s. He had gained a reputation for making epic historical films in the silent era, most notably The Miracle of the Wolves (1924), an impressive but already old-fashioned, rather stodgy tale of Fifteenth Century France. (Available online in a restored version subtitled in English.) In the early sound era, however, the success of those earlier films allowed him to make two masterpieces.

Wooden Crosses featured on my 1932 list. It was highly successful in France, giving Bernard the chance to immediately launch into an adaptation of Victor Hugo’s popular novel. He proposed making it in three feature films in order to retain as much of the story as possible: “Une tempête sous le crane,” “Les Thénardier,” and “Liberté, liberté chérie.” The tale intertwines two plotlines. Hardened criminal Jean Valjean escapes and reforms through the love for Cossette, an abused orphan he rescues from harsh innkeepers (the Thénardiers). He becomes respectable and rich under a false identity, though he is in constant danger from Inspector Javert, who implacably seeks for years to track him down. The second plotline deals with young people involved in the French Revolution, one of whom falls in love with the grown-up Cossette.

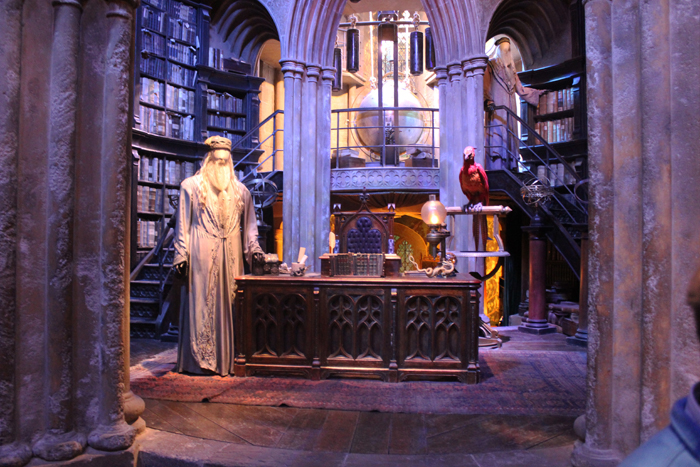

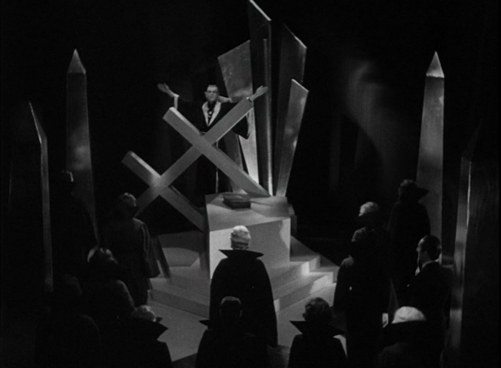

Harry Baur and Charles Vanel, playing Valjean and Javert respectively, are ideally cast. As in Wooden Crosses, the cinematography by Jules Kruger (who also shot Wooden Crosses and was one of several cinematographers on Napoléon vu par Abel Gance) is superb. Apart from the remarkably precise lighting (see above), it contains many shots using a canted framing, a technique that later drew considerable attention in The Third Man. Here Madame Thénardier scolds Cosette and a group of revolutionaries hold a meeting.

The three features made Les Misérables into a serial, much like Alberto Capellani’s 1912 version. Again, it was a considerable success. The film industry in France was in trouble as the Depression dragged on, however, and expensive epics like those of Bernard were no longer feasible. He was assigned to lower budget films, including romantic comedies, while other directors introduced the Poetic Realism that characterized the rest of the decade.

Les Misérables‘ popularity led to its being re-released repeatedly with various re-edited, shorter versions playing for decade, starting in 1935. In May Pathé released a two-and-a-half-hour version, eliminating about half the original film’s length. This and other versions are summarized in Criterion’s notes to the Eclipse set. Late in his life Bernard was able to help assemble footage from several prints, leading to a restoration that still lacks a few scenes.

Les Misérables is available on The Criterion Channel and from The Criterion Collection in the same Eclipse box set that contains Wooden Crosses. Arthur Honegger’s very effective score for the film has been released on CD and is still in print.

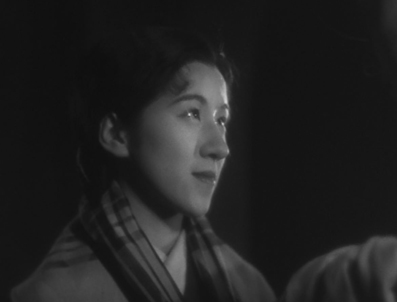

Story of Floating Weeds (Yasujiro Ozu)

The last four years’ best lists have included films by Ozu: That Night’s Wife (1930), Tokyo Chorus (1931), I Was Born, But … (1932), and a double-header, Passing Fancy and Dragnet Girl (1933). For 1934, he’s back with Story of Floating Weeds. (His other film of that year, A Mother Should Be Loved, unfortunately is missing the first and last of its nine reels.)

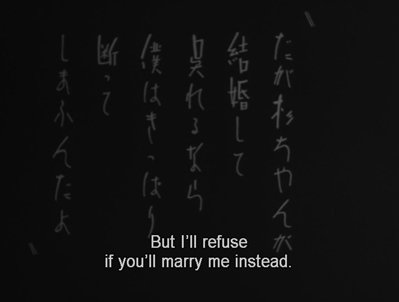

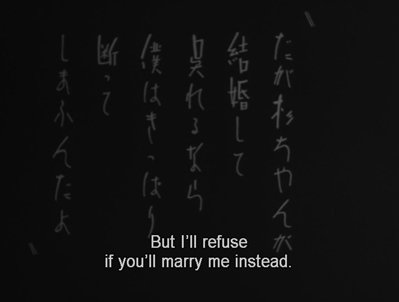

The story revolves around a down-at-heels traveling theatrical troupe which stops to performs in a rural village. They remain there for longer than the dwindling audiences would warrant, and we learn that the group’s leader, Kihachi, is secretly visiting an old flame of his and their son, Shinkichi. She has raised the boy to believe that his father died long ago. He thinks that Kihachi is his genial uncle. The female lead in the company, Otaka, who is also Kihachi’s mistress, learns of this. Out of jealousy she enlists a younger actress, Otoki, to seduce the boy, thus threatening his promising future.

As David points out in his Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, this film departs from Ozu’s earlier work:

The film is played in a remote rural village, a realistic locale for the traveling troupe but an unusual setting for Ozu at this point in his career. The cinéaste of urban Tokyo, of nansensu [nonsense] and moga [modern girl], must now impose his narrational system on a different Japanese iconography: the village street, the landscape, the forlorn café, the decaying theatre. He must film a traditional, if ineptly staged, performance. He must no longer cut away to Lincolns or spinning ventilators or Nipper the RCA dog. Ozu now experiments with treating centuries-old material in his own, recently matured manner. (p. 257)

One example of village iconography that he cites is the “death tree,” a folk tradition where small memorial banners are left for the dead. Otoki sits by the tree as she waits to seduce Shinkichi, and “her casual intrusion into a sacred space underlines the extent to which the actress is an outside to the village” (p. 258). By contrast, the scene in which Kihachi goes fishing with his son uses the countryside to indicate a mood of natural serenity.

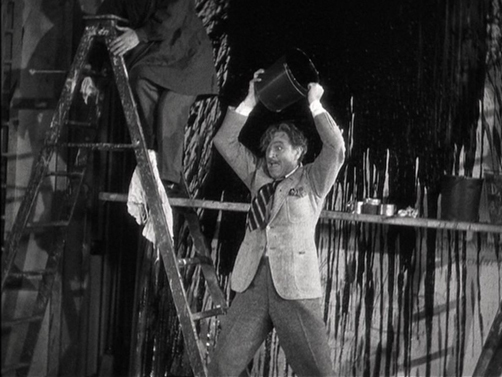

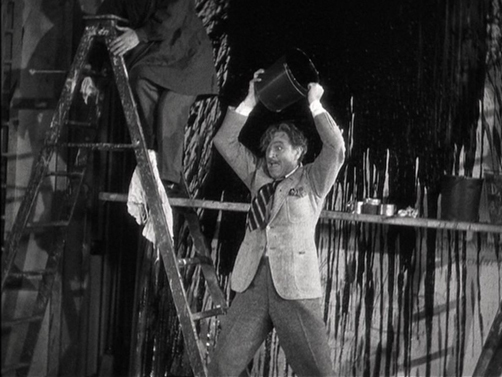

Story of Floating Weeds is not bereft of the humor present in so many early Ozu films, but he largely confines it to the early scenes, before we learn of Kihachi’s secret life. The inept theatrical performance includes people in obvious animal costumes, as when the young boy of the troupe plays a dog, standing up, taking off its head, and scratching his crotch (top) while Kihachi tries to remain in character. Later, when it starts to rain, water comes through the numerous holes in the roof, and the actors pass through the audience, who are seated on the floor, passing out bowls to catch the drips. Once this early portion of the film is over, the tone turns toward melodrama, and there are only rare moments of humor.

Story of Floating Weeds, along with many of Ozu’s films, is streaming on The Criterion Channel and is available as a DVD or Blu-ray in Criterion’s box set pairing it with Ozu’s 1959 remake, Floating Weeds.

Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks)

Hawks was one of those rare Hollywood directors who could work in virtually any major genre and make outstanding films. He made gangster films, musicals, westerns, murder mysteries, romances, comedies, and military films. He also dabbled in less fruitful genres: science-fiction (assuming he really directed The Thing from Another World) and historical epics (Land of the Pharaohs).

The first film that comes to mind when contemplating Hawks’s comedies is no doubt His Girl Friday. One of David’s and my favorite Hollywood films, it featured in at least two recent film series compiled as tributes to him (the UW Cinematheque last summer and The Music Box in Chicago in September). Next would probably be Bringing Up Baby. Maybe I’m wrong, but I suspect Twentieth Century would come in a somewhat distant third. Yet it is, to put it mildly, hilarious, with a great script and two outstanding central performances backed up by some of the great character actors of the period.

Although John Barrymore started out on the stage with light comedies, he soon was starring in Shakespeare, including his Hamlet, which led to him being dubbed “The greatest living American tragedian.” Once he moved into films in the 1920s, he usually was cast as the lead in prestigious literary adaptations and romances: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Sherlock Holmes, Beau Brummel, Beloved Rogue, Don Juan, and perhaps Lubitsch’s least interesting silent film, Eternal Love. The pattern continued into the early sound period, most notably in Grand Hotel.

Hawks gave him the chance to cut loose his comedic talents, and the resulting performance was flamboyant. To say Barrymore overacted is a mistake, I think, since theatrical impresario Oscar Jaffe is a ludicrously flamboyant character.

The film starts with Jaffe transforming a lingerie model into a theatrical star, Lily Garland (Carol Lombard, who became a major star with this film). They begin a tempestuous affair. Years later, realizing that Jaffe is jealously watching her every move, she flees to Hollywood and becomes a movie star. Without her, Jaffe’s plays fail, and he heads for Los Angeles to beg her to return. Coincidentally they end up on the same train without initially being aware of it, and their battles resume.

The departure of Lily for Hollywood removes Lombard from the action for a lengthy period, giving Barrymore a chance to demonstrate that he can do comedy with the best of them. Upon learning that Lily has left him, Jaffe staggers through the theater, ranting as his mercurial moods swing from despair (“Let life run over me!”) to rage (“Anathema! Child of Satan!”):

Once the pair meet on the Twentieth Century, Lily refuses to return to Jaffe, and an shouting match begins. This ends with the two collapsing in utter exhaustion (top of this section). Lombard holds her own through this, but she is the more sensible of the two and generally acts with more restraint in other scenes.

There is a very funny running gag about an innocent-looking elderly man who surreptitiously posts stickers reading “Repent for the time is at hand,” and Walter Connolly and Roscoe Karns, playing Jaffe’s assistant, provide wisecracks as Jaffe repeatedly hires and fires them.

Twentieth Century can be streamed on Amazon Prime and Apple + for $3.99. A fairly decent DVD is available.

The Man Who Knew too Much (Alfred Hitchcock)

Like Twentieth Century in Hawks’s career in the 1930s, The Man Who Knew too Much is one of the underrated films of Hitchcock’s career in this period. David and I both liked it very much. Indeed, when he was starting out teaching Introduction to Film at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he showed it to the class. A brief essay about it featured in the first edition of Film Art: An Introduction in the “sample analyses” section. (This was and still is intended to demonstrate how to analyze form and style across an entire film rather than just learn about individual film techniques.) We replaced it after the second edition with a different analysis, but like all the other sample analyses that have been replaced during revisions, it is available on David’s main blog page. Click here and scroll to the bottom of the list to download a PDF of it.

The brief description there says:

Like His Girl Friday, The Man Who Knew Too Much presents us with a model of narrative construction. Its plot composition and its motivations for action contribute to making the film what a scriptwriter would call “tight.” Moreover, the film also offers an object lesson in the use of cinematic style for narrative purposes. Finally, the film illustrates how narration can manipulate the audience’s knowledge, sometimes making drastic shifts from moment to moment.

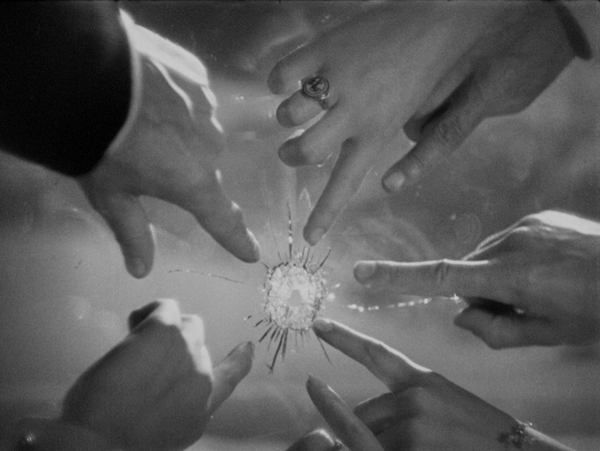

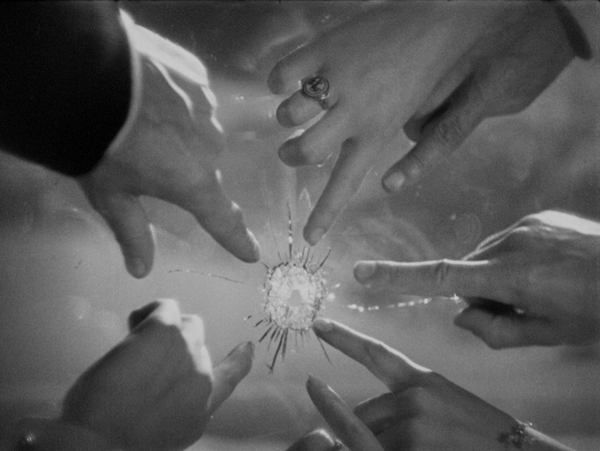

We both considered it superior to Hitchcock’s 1956 remake. After all, it is indeed “tight,” telling the entire story in a mere 75 minutes as opposed to two hours. And Hitchcock is increasingly adept at telling his story visually. Take the striking image above. The second scene at a fancy hotel restaurant involves the assassination of Louis Bernard, a friend of the Lawrence family, who are unaware that he is a French spy cooperating with British intelligence. The shot comes from offscreen, and we watch Bernard die in the midst of a crowd. Hitchcock doesn’t have anyone tell us that the bullet came from outside. He cuts to a shot of the star-shaped hole in a window with five people pointing at it, their fingers extending the star-shaped pattern of the cracks. (Never mind that a vertical window could not be pointed at from all sides.)

The casting is also better, in my opinion. (I like Doris Day well enough, but when I watch her, I want it to be as Babe in The Pajama Game.) Lesley Banks makes a good protagonist. His attempts to ingratiate the main villain, Abbott, by acting nonchalant and amused by his banter, even though he knows this man has kidnapped his daughter and is holding her in a room nearby. Abbott is played by Peter Lorre, who is a major asset in the film. (David always claimed that Lorre improved any film he was in, which is quite possible.) On the right below, Abbott calmly has a meal, contrasting with all the other characters, who tensely listen to the radio, waiting for the climactic moment in the orchestral piece when the second assassination is planned to happen.

Back when David was teaching the film, prints were gray and fuzzy. Luckily the Criterion Blu-ray features the restored version, and it is playing permanently on the Criterion Channel as well.

The Merry Widow (Ernst Lubitsch)

I am not particularly fond of Lubitsch’s musicals from the 1929-1932 period. Hence I had never made much effort to see the slightly later The Merry Widow, in part because it’s not that easy to see, as I’ll explain below.

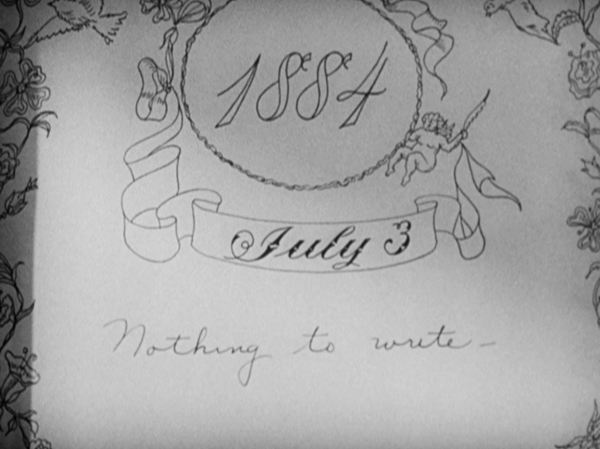

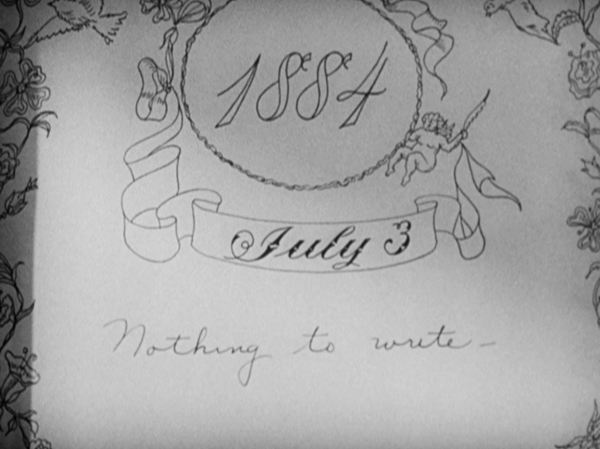

The story begins in Marshovia, a tiny imaginary kingdom in eastern Europe. The opening number introduces Captain Danilo (Maurice Chevalier), who has apparently bedded most of the female population of the country. He is intrigued by the mysterious black-garbed widow, Madame Sonia, who is so wealthy that the economy of the country depends largely on her. He invades her home in an attempted seduction, but in a bantering exchange Sonia rejects him. That her mourning is oppressing her is conveyed by pages of her diary turning, with shorter entries culminating with “Nothing to write-” (above) followed by blank pages.

Determining to live an exciting life, she departs to Paris. Danilo is dispatched to woo and marry her so that she will return to Marshovia. Though initially he tries to seduce her, but naturally he falls in love with her. She, aware of his reputation, dismisses his wooing as lies and continues her madcap life.

With such a risqué story to tell, Lubitsch manages to convey it with visuals and innuendos. Sonia’s sudden transition from mourning widow to reckless, fun-seeking widow is handled by a series of dissolves which show her black shoes, dresses, hats, and even corsets turn white (at least in a black-and-white film).

When she asks her three maids where Danilo lives, all three cheerily reel off the same address address. Realizing what they have revealed about their relationships with the serial seducer, their smiles disappear as they lower their eyes–the Lubitsch Touch at work.

The use of Franz Lehar’s music (though with some altered lyrics) leads to a better quality of musical numbers than most films of the day had. Lubitsch was also given a considerable budget, and the set design won Oscars for Cedric Gibbons and Frederic Hope.

The two leads are inevitably charming, and once again supporting players–Edward Everett Horton, Una Merkel, Donald Meek, and Herman Bing–supply humor throughout.

The Merry Widow is streaming on Amazon Prime and Apple +, with a $3.99 rental charge. It unfortunately is not in the Criterion Collection’s box set of Lubitsch musicals, but is available on a Warner Bros. Archive DVD.

It Happened One Night (Frank Capra)

I doubt I need to say much about this one. Anyone who hasn’t seen it probably is not interested in seeing ninety-year-old films and certainly wouldn’t be reading about them here.

The plot is known to all. Ellie Andrews, the spoiled child of a doting, wealthy father flees to rejoin her new husband, whom she thinks she loves. He wants the marriage annulled, assuming the man is after her money. On a bus from Florida to New York, she meets Peter Warne, a newspaper reporter in trouble with his boss. They take an instant dislike to each other, but Peter offers to take care of Ellie if she will give him an exclusive story about her flight. They encounter numerous problems, from stolen luggage to a steadily dwindling supply of cash.

The casting of Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert is perfect, the script is great, etc.

Again, this is a film I saw back in my graduate-school days. I enjoyed it, but it was the typical soft, low-contrast 16mm print so common in those days. The 4K restoration on the Criterion Blu-ray reveals something that was not evident then: this film was superbly lensed by the great cinematographer Joseph Walker, who shot many of the screwball comedies of the decade but also the brooding Only Angels Have Wings. The scene of the two forced to sleep rough on some improvised hay beds is as good as a three-point lighting in a night-time, studio-shot set can get. There’s also the simpler scene which holds on Ellie in silhouette, having a conversation with Peter across the blanket serving as “the Walls of Jericho.”

It Happened One Night is probably not the first screwball comedy, which is considered a sub-genre of the romantic comedy. It may be the first in what I think might be a sub-sub-genre, which revolves around a rich woman who can afford to follow her whims and defy conventions. Ellie starts out rich, though her money is stolen during early on. Carol Lombard’s character in My Man Godfrey is another classic case, with a carefree young woman from a wealthy family finds a homeless man as required for a scavenger hunt, paying $5 for him to appear at a party. His indignation leads her to hire him as a butler. Bringing Up Baby also depends on the Katherine Hepburn character’s wealth that allows her to follow her whims and boss Cary Grant’s paleontologist around. In all cases the man resists being manipulated, but love results eventually.

It Happened One Night is available in an excellent restoration on Blu-ray and DVD from Criterion. It streams on Apple + and some smaller services for $3.99.

Street without End (Mikio Naruse)

Naruse is known to many from his prolific career after World War II. In the 1930s, however, he also made many films, though a considerable number of those are lost. He was one of the four major directors working for Shochiku, the others being Yasujiro Ozu, Hiroshi Shimizu, and Heinosuke Gosho. The head of the studio, however, did not consider him to be on the same level as those three, and Naruse felt that he was being given less creative freedom than the others. Indeed, the other three had passed on the script for Street without End, since it was based on a tabloid serial about a café hostess. Naruse had no choice but to accept the assignment.

Naruse frequently centering his plots around women. In this case, the protagonist is Sugiko, a working-class woman content with her job in a café. She is approached by an film-studio agent who offers her an acting job, but despite her waitress friend Kesako’s excitement at the idea, she turns it down. Kesako takes the job instead and is a success but grows tired of the job. Sugiko is slightly injured struck by a car belonging to a rich man, Hiroshi, a man from the upper-class Yamanouchi family. He falls in love with her and proposes. All her friends urge her to jump at this chance, but her brother warns her that the wealthy family will not accept her. Despite this, Sugiko loves Hiroshi and marries him. As predicted, Hiroshi’s mother and sister snub Sugiko and make her married life miserable.

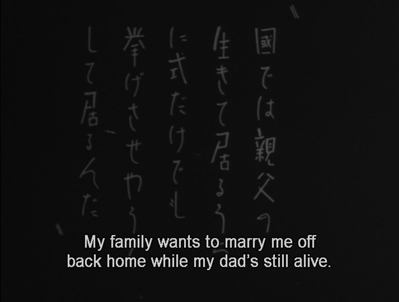

Naruse’s style in the film somewhat echoes that of Ozu, yet he seems to be trying variants on it. In this early scene, Sugiko’s boyfriend Machio breaks the news that his family has found a bride for him, but he says he’ll marry Sugiko if she agrees. In the course of the scene, Naruse cuts away from the couple to shots of two street lamps, seen from a different angle each time. Ozu typically uses shot of spaces without the characters as a transition device between scenes, but here such shots interrupt the action repeatedly.

1 2 2 3 3

4 5 5 6 6

7 8 8 9 9

10 11 11 12 12

Once Machio has said he will marry Sugiko, there is another shot of the two lamps, closer than before (11). This is followed by a shot/reverse shot pattern between the two. At first Machio is seen looking rightward (12), with the cut to Sugiko showing her also facing rightward (13), a common tactic used by Ozu. Here, however, the cut back to Machio shows him facing leftward (14), as would be conventional following a shot of her looking rightward. Ozu would keep the characters facing the same direction throughout a shot/reverse-shot pattern (shots 9, 10, and 11). In shot 11 Machio turns to exit and shot, and in 15 he is seen from behind walking away from her–perhaps because she does not answer him immediately.

13 14 14 15 15

The only reason I can see for this change on the framing of Machio in the second shot of him is an echo of an earlier moment in the scene. In the shot in which Sugiko reacts to his news of his parents plan for him to marry, she turns away and starts out left (frames 6 & 7 above). The next shot shows her from the back, moving away from him. Within this shot, he goes after her and faces her again (frames 7 and 8). A cut-in leads to the inconsistent shot/reverse shots. This time he is the one to move away from her (compare frame 15 with frame 8). He returns to say they will have little money (16). After another cutaway to the two lamps (18), the scene continues with Sugiko saying will marry him anyway. Perhaps this echo hints at their eventual failure to marry.

16 17 17 18 18